Writing for Social Media in 2024: Tips and Tools

Writing for social media takes talent, creativity, focus, and a deep understanding of your audience. Here are a few tips to help you get started.

Writing for social media: 7 tips for 2024

Writing for social media is not an easy job.

You work with strict character limits and tight turnarounds. You speak the language of memes and microtrends that your boss and coworkers might not understand. You have to quickly — and wittily — react to trending topics. And, if you ever publish a post with a typo, people will notice and call you out. (Looking at you, Twitter meanies.)

But it’s also fun and rewarding. Great content can help you start inspiring conversations, build engaged communities, create buzz around your brand, and even directly influence sales.

Keep reading for expert tips and tools that will help you become a more confident and effective social media writer in no time .

OwlyWriter AI instantly generates captions and content ideas for every social media network. It’s seriously easy.

What is social media content writing?

Social media content writing is the process of writing content for social media audiences, usually across multiple major social media platforms . It can include writing short captions for TikTok or Instagram Reels, long-form LinkedIn articles, and everything in between.

Writing for social media is different from writing for blogs and websites — it requires expert knowledge of social platforms and their audiences, trends, and inside jokes.

Social media writing is a crucial element of any brand’s social presence. It can make or break a campaign or your entire social media marketing strategy. When done right, social writing directly influences engagement and conversions, and contributes to strategic business goals.

7 social media writing tips for 2024

The tips below will help you create content that will inspire your target audience to interact with you, take action, or simply spend a few seconds contemplating what they just read.

Try some (or all) of these in your next 10 social media posts to build good habits and strengthen your writing muscle. You’ll be amazed at how clear you’ll write, and how you’ll zero in on your voice.

Bonus: Download The Wheel of Copy , a free visual guide to crafting persuasive headlines, emails, ads and calls to action . Save time and write copy that sells!

1. Just start writing (you’ll edit later)

Writer’s block is real, but there’s an easy way to blast past it: Just start writing without overthinking it.

Start typing whatever comes to mind and forget about sentence structure, spelling, and punctuation (for a moment). Just keep your fingers moving and power through any blockages. Editing will come later.

This is how John Swartzwelder, legendary Simpsons writer, wrote scripts for the show :

“Since writing is very hard and rewriting is comparatively easy and rather fun, I always write my scripts all the way through as fast as I can, the first day, if possible, putting in crap jokes and pattern dialogue […]. Then the next day, when I get up, the script’s been written. It’s lousy, but it’s a script. The hard part is done. It’s like a crappy little elf has snuck into my office and badly done all my work for me, and then left with a tip of his crappy hat. All I have to do from that point on is fix it.”

2. Speak the language of social media

This, of course, means different things on different platforms.

Eileen Kwok, Social Marketing Coordinator at Hootsuite thinks it’s absolutely crucial to “have a good understanding of what language speaks to your target audience. Every channel serves a different purpose, so the copy needs to vary.”

Wondering what that looks like, exactly, on Hootsuite’s own social media channels? “LinkedIn, for example, is a space for working professionals, so we prioritize educational and thought leadership content on the platform. Our audience on TikTok is more casual, so we give them videos that speak to the fun and authentic side of our brand.”

But this advice goes beyond picking the right content categories and post types for each network. It really comes down to the language you use.

Eileen says: “On most channels, you’ll want to spell-check everything and make sure you’re grammatically correct — but those rules don’t apply for TikTok. Having words in all caps for dramatic effect, using emojis instead of words, and even the misspelling of words all serves the playful nature of the app.”

You can go ahead and show this to your boss the next time they don’t want to approve a TikTok caption mentioning Dula Peep or using absolutely no punctuation.

3. Make your posts accessible

As a social media writer, you should make sure that everyone in your audience can enjoy your posts.

Nick Martin, Social Listening and Engagement Strategist at Hootsuite told me: “When writing for social media, accessibility is something you should be keeping in mind. Some of your followers may use screen-readers, and a post that is full of emojis would be nearly unreadable for them.”

Unintelligible posts won’t help you reach your social media goals. In fact, they might turn people away from your brand altogether.

“The same goes for when you share an image that has text on it,” Nick adds. “You’ll want to make sure you write alt-text for that image so all of your audience can enjoy it.”

Here’s a great example of how you can have fun writing creative and entertaining alt-text for your social post’s accompanying images:

Self-care routines and bear encounters both start with setting boundaries pic.twitter.com/reul7uausI — Washington State Dept. of Natural Resources (@waDNR) September 20, 2022

4. Keep it simple

Imagine you’re writing to an 8th grader. Like, actually .

This is a simple but super effective exercise that will force you to write clearly and ditch any unnecessary jargon that would likely only confuse your readers.

“Drive innovation.”

“Become a disruptor.”

LinkedIn, in particular, is home to some of the most over-used, under-effective statements of all time. And sure, it’s a “businessy” social media channel. But business people are, well, people too. And people respond well to succinct, clear copy — not overused buzzwords with little to no real meaning behind them.

To connect with your audience, you have to speak a language they understand. Say something real. Use plain language and short sentences. Practice on your niece, mom, or friend, and see if they get your message.

5. Write to the reader

Your social media audience isn’t dying to find out what your company is up to or what’s important to you (unless it’s super relevant). They want to know what’s in it for them. That’s why you should always write from the readers’ perspective. Make them the hero.

So, instead of posting a boring list of features that have just been added to your product, tell your audience how their life will improve if they use it.

Sometimes, “standing out” is nothing more than writing from the reader’s point of view — because most of your competitors don’t.

6. Have a clear purpose

… and write that purpose down at the top of your draft to keep your mind on the target while you write.

What action do you want the reader to take? Do you want them to leave a comment or click through to your website? Whatever it is, make it clear in a CTA (call to action).

Note that a CTA doesn’t have to be a button or any other super explicit, easily identifiable element within your post. It can be as simple as an engaging question within your caption, or a sentence telling your audience why they should click on the link in your bio.

7. Use (the right) pictures to enhance your words

This one speaks for itself. (One image is worth a thousand words, anyone?)

We’ve already talked about the importance of adding alt-text to images for accessibility, but the images you pick are very important.

Some networks rely on words more than they do on images and videos. But whenever possible (and relevant), you should try to include visuals in your posts — they’re much more effective at grabbing the attention of scrollers than words. And without that attention, your words won’t get a chance to shine.

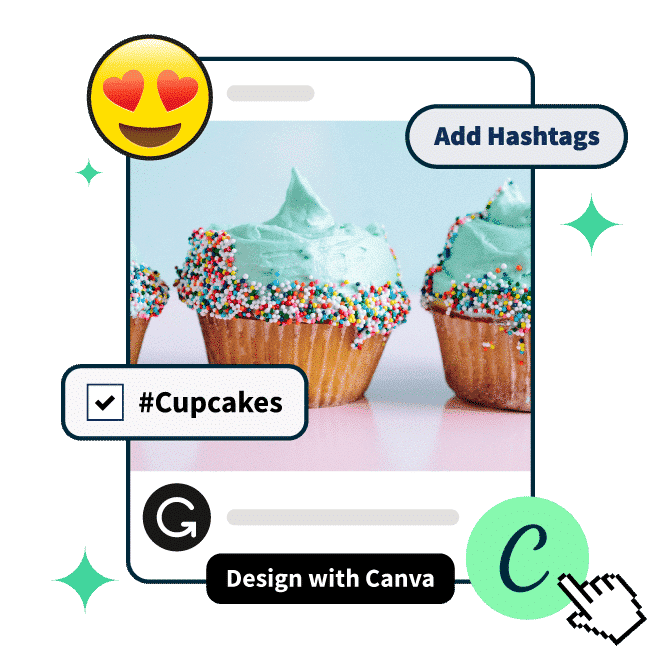

Everything you need to make engaging content. AI support for captions, an AI hashtag generator, and access to Canva in Hootsuite.

3 writing tools for social media

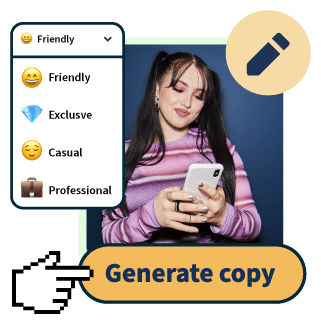

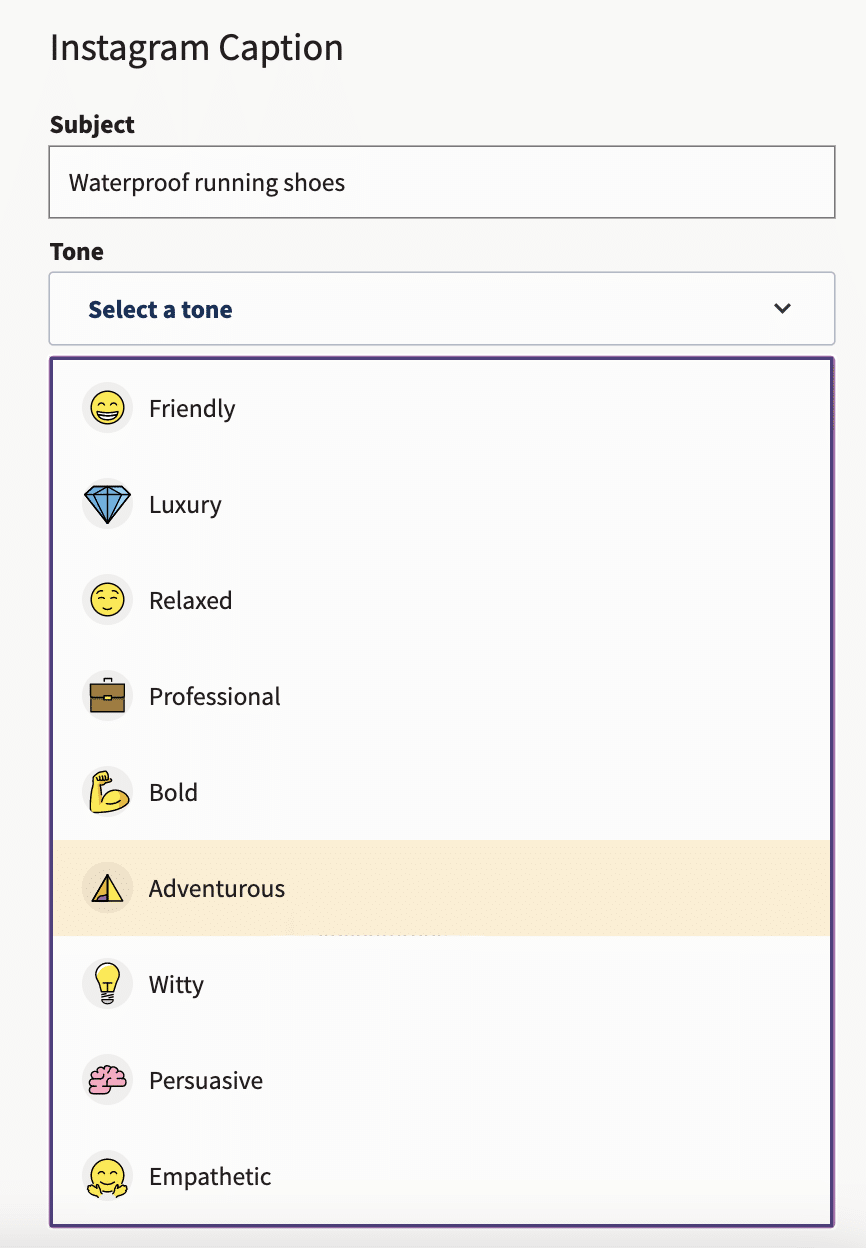

1. hootsuite’s owlywriter ai.

Good for: Generating social media posts and ideas, repurposing web content, and filling up your social media calendar faster.

Cost: Included in Hootsuite Pro plans and higher

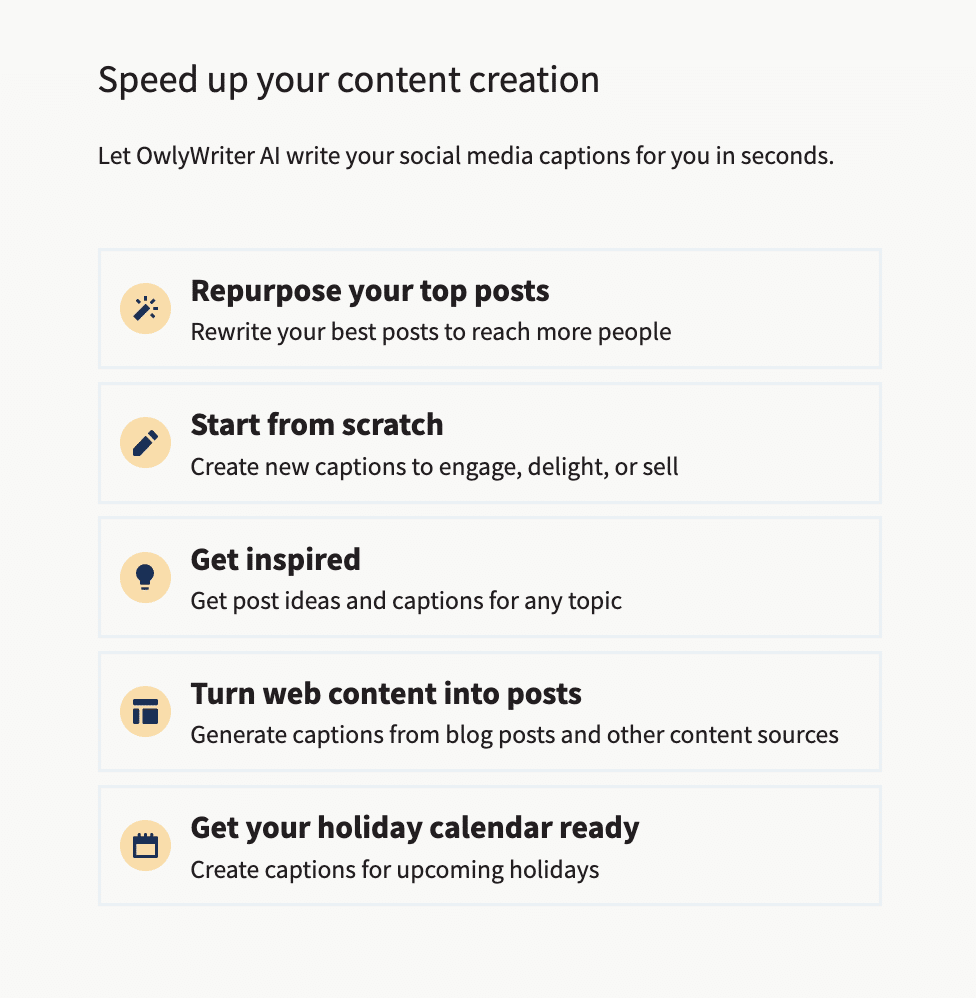

Did you know that Hootsuite comes with OwlyWriter AI, a built-in creative AI tool that saves social media pros hours of work?

You can use OwlyWriter to:

- Write a new social media caption in a specific tone, based on a prompt

- Write a post based on a link (e.g. a blog post or a product page)

- Generate post ideas based on a keyword or topic (and then write posts expanding on the idea you like best)

- Identify and repurpose your top-performing posts

- Create relevant captions for upcoming holidays

To get started with OwlyWriter, sign in to your Hootsuite account and head to the Inspiration section of the dashboard. Then, pick the type of AI magic you want to see in action.

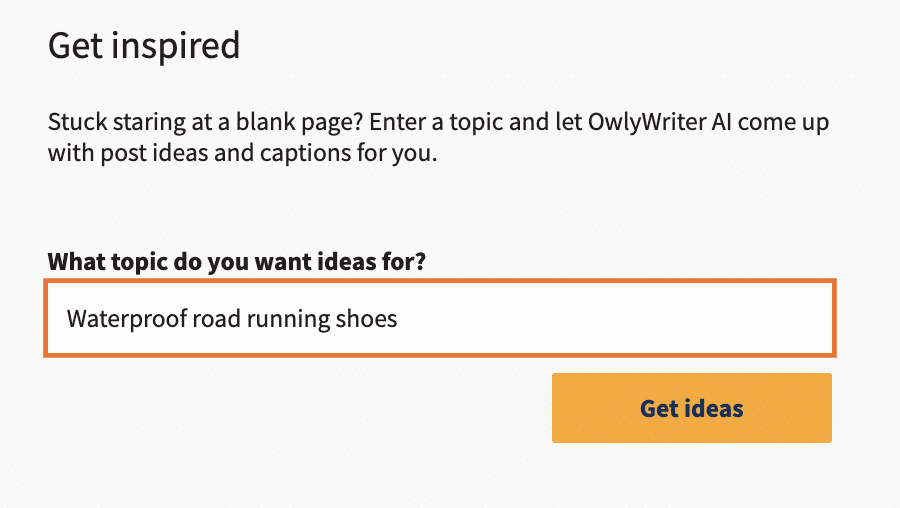

For example, if you’re not sure what to post, click on Get inspired . Then, type in the general, high-level topic you want to address and click Get ideas .

Start your free 30-day trial

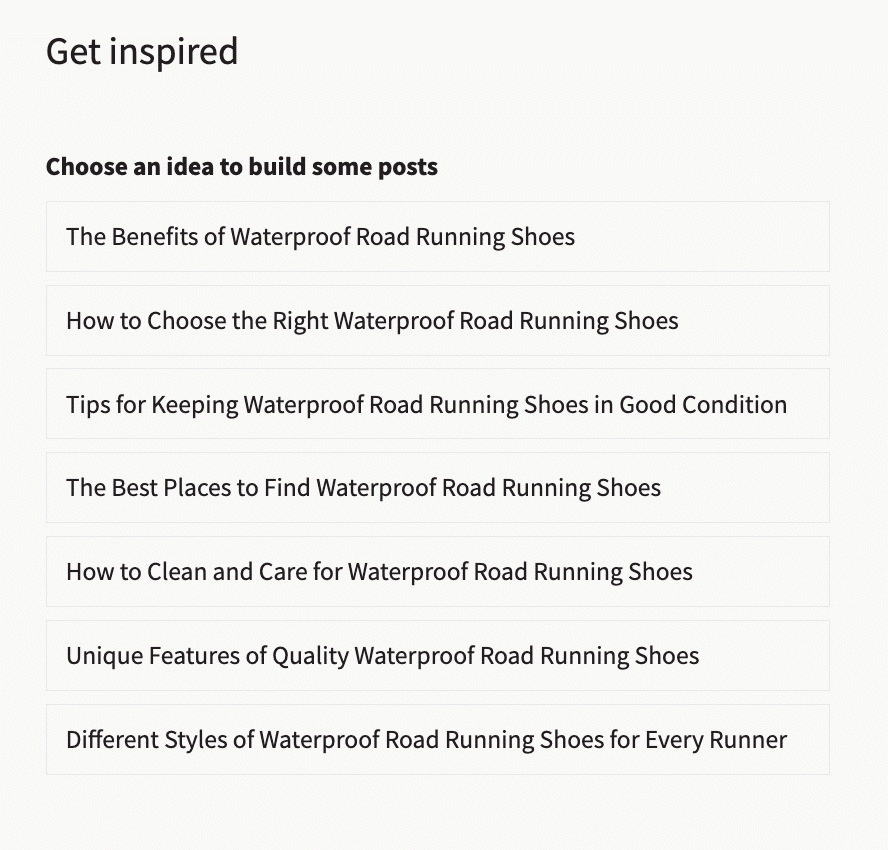

OwlyWriter will generate a list of post ideas related to the topic:

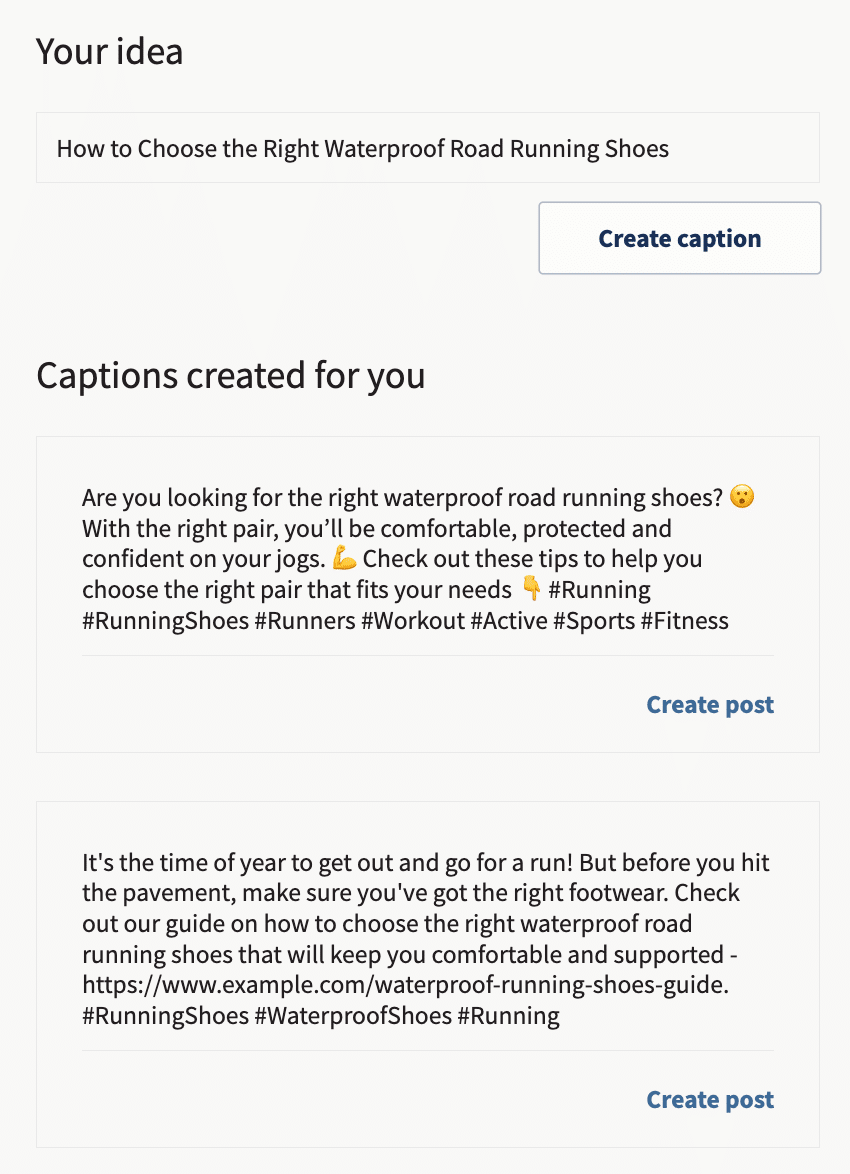

Click on the one you like best to move to the next step — captions and hashtags.

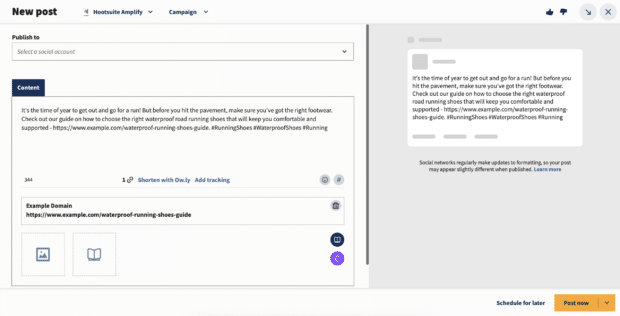

Pick the caption you like and click Create post . The caption will open in Hootsuite Composer, where you can make edits, add media files and links, check the copy against your compliance guidelines — and schedule your post to go live later.

And that’s it! OwlyWriter never runs out of ideas, so you can repeat this process until your social media calendar is full — and sit back to watch your engagement grow.

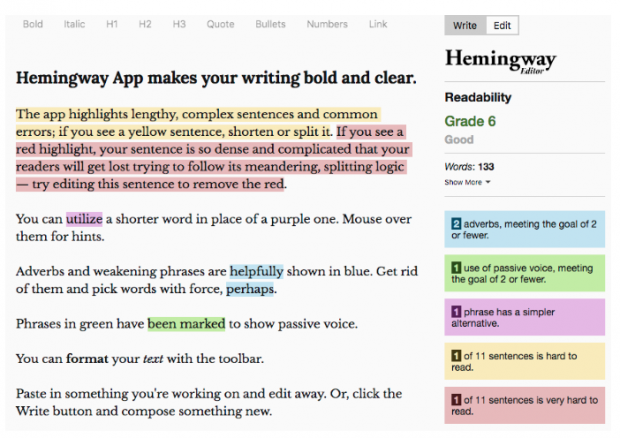

2. Hemingway app

Good for: Writing anything succinctly and clearly.

Cost: Free in your browser, one-time $19.99 payment for the desktop app.

The Hemingway app will make you a better, more engaging writer. It flags over-complicated words and phrases, long sentences, unnecessary adverbs, passive voice, and so much more. It also gives you a readability score.

Pro tip: On the Hootsuite editorial team, we always aim for grade 6 readability. Some topics are simply a bit complicated, so stay flexible and don’t beat yourself up if you’re not always able to reach this benchmark — but it’s a good score to shoot for.

Here’s how it works:

- Write your copy.

- Paste it into Hemingway’s online editor .

- Visually see what works and what doesn’t.

- Make your changes.

- Watch your score improve!

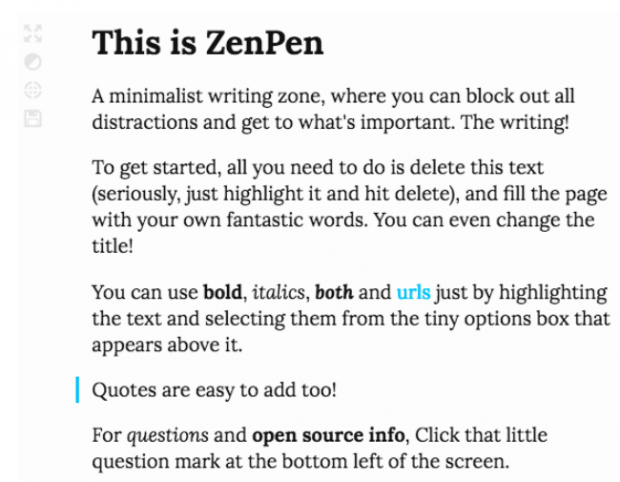

Good for: Distraction-free writing.

Cost: Free.

There’s plenty of clutter in life. ZenPen is one small corner of the distraction-free-universe to help you write without outside interference.

- Go to zenpen.io .

- Start writing posts for social.

- Enjoy the noise-free editor until you’re done.

Compose, schedule, and publish your expertly written posts to all the major social media channels from one dashboard using Hootsuite. Try it free today.

Get Started

Save time and grow faster with OwlyWriter AI, the tool that instantly generates social media captions and content ideas .

Become a better social marketer.

Get expert social media advice delivered straight to your inbox.

Karolina Mikolajczyk is a Senior Inbound Marketing Strategist and associate editor of the Hootsuite blog. After completing her Master’s degree in English, Karolina launched her marketing career in 2014. Before joining Hootsuite in 2021, she worked with digital marketing agencies, SaaS startups, and international corporations, helping businesses and social media content creators grow their online presence and improve conversions through SEO and content marketing strategies.

Nick has over ten years of social media marketing experience, working with brands large and small alike. If you've had a conversation with Hootsuite on social media over the past six years, there's a good chance you've been talking to Nick. His social listening and data analysis projects have been used in major publications such as Forbes, Adweek, the Washington Post, and the New York Times. His work even accurately predicted the outcome of the 2020 US presidential election. When Nick isn't engaging online on behalf of the brand or running his social listening projects, he helps coach teams across the organization in the art of social selling and personal branding. Follow Nick on Twitter at @AtNickMartin.

Eileen is a skilled social media strategist and multi-faceted content creator, with over 4+ years of experience in the marketing space. She helps brands find their unique voice online and turn their stories into powerful content.

She currently works as a social marketer at Hootsuite where she builds social media campaign strategies, does influencer outreach, identifies upcoming trends, and creates viral-worthy content.

Related Articles

10 AI Content Creation Tools That Won’t Take Your Job (But Will Make it Easier)

AI-content creation tools can’t replace great writers — but they help writers and marketers save time and use their skills for more strategic aspects of content creation.

Your 2024 Guide to Social Media Content Creation

Find out how to build an effective social media content creation process and learn about the tools that will make creating content easier.

How to Create a Social Media Marketing Strategy in 9 Easy Steps [Free Template]

Creating your social media marketing strategy doesn’t need to be painful. Create an effective plan for your business in 9 simple steps.

9 Best AI Copywriting Tools (Beyond ChatGPT)

Ready or not, they’re here. AI copywriting tools can be your new best friend — if you know how to use them.

151 Instagram Quotes for Literally Any Occasion

Trying to find the perfect Instagram quote for your post, Reel or bio? We’ve got 150+ options to suit any occasion.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, social network sites: a definition, a history of social network sites, previous scholarship, overview of this special theme section, future research, acknowledgment, about the authors.

- < Previous

Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

danah m. boyd, Nicole B. Ellison, Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , Volume 13, Issue 1, 1 October 2007, Pages 210–230, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Social network sites (SNSs) are increasingly attracting the attention of academic and industry researchers intrigued by their affordances and reach. This special theme section of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication brings together scholarship on these emergent phenomena. In this introductory article, we describe features of SNSs and propose a comprehensive definition. We then present one perspective on the history of such sites, discussing key changes and developments. After briefly summarizing existing scholarship concerning SNSs, we discuss the articles in this special section and conclude with considerations for future research.

Since their introduction, social network sites (SNSs) such as MySpace, Facebook, Cyworld, and Bebo have attracted millions of users, many of whom have integrated these sites into their daily practices. As of this writing, there are hundreds of SNSs, with various technological affordances, supporting a wide range of interests and practices. While their key technological features are fairly consistent, the cultures that emerge around SNSs are varied. Most sites support the maintenance of pre-existing social networks, but others help strangers connect based on shared interests, political views, or activities. Some sites cater to diverse audiences, while others attract people based on common language or shared racial, sexual, religious, or nationality-based identities. Sites also vary in the extent to which they incorporate new information and communication tools, such as mobile connectivity, blogging, and photo/video-sharing.

Scholars from disparate fields have examined SNSs in order to understand the practices, implications, culture, and meaning of the sites, as well as users’ engagement with them. This special theme section of the Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication brings together a unique collection of articles that analyze a wide spectrum of social network sites using various methodological techniques, theoretical traditions, and analytic approaches. By collecting these articles in this issue, our goal is to showcase some of the interdisciplinary scholarship around these sites.

The purpose of this introduction is to provide a conceptual, historical, and scholarly context for the articles in this collection. We begin by defining what constitutes a social network site and then present one perspective on the historical development of SNSs, drawing from personal interviews and public accounts of sites and their changes over time. Following this, we review recent scholarship on SNSs and attempt to contextualize and highlight key works. We conclude with a description of the articles included in this special section and suggestions for future research.

We define social network sites as web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. The nature and nomenclature of these connections may vary from site to site.

While we use the term “social network site” to describe this phenomenon, the term “social networking sites” also appears in public discourse, and the two terms are often used interchangeably. We chose not to employ the term “networking” for two reasons: emphasis and scope. “Networking” emphasizes relationship initiation, often between strangers. While networking is possible on these sites, it is not the primary practice on many of them, nor is it what differentiates them from other forms of computer-mediated communication (CMC).

What makes social network sites unique is not that they allow individuals to meet strangers, but rather that they enable users to articulate and make visible their social networks. This can result in connections between individuals that would not otherwise be made, but that is often not the goal, and these meetings are frequently between “latent ties” ( Haythornthwaite, 2005 ) who share some offline connection. On many of the large SNSs, participants are not necessarily “networking” or looking to meet new people; instead, they are primarily communicating with people who are already a part of their extended social network. To emphasize this articulated social network as a critical organizing feature of these sites, we label them “social network sites.”

While SNSs have implemented a wide variety of technical features, their backbone consists of visible profiles that display an articulated list of Friends 1 who are also users of the system. Profiles are unique pages where one can “type oneself into being” ( Sundén, 2003 , p. 3). After joining an SNS, an individual is asked to fill out forms containing a series of questions. The profile is generated using the answers to these questions, which typically include descriptors such as age, location, interests, and an “about me” section. Most sites also encourage users to upload a profile photo. Some sites allow users to enhance their profiles by adding multimedia content or modifying their profile’s look and feel. Others, such as Facebook, allow users to add modules (“Applications”) that enhance their profile.

The visibility of a profile varies by site and according to user discretion. By default, profiles on Friendster and Tribe.net are crawled by search engines, making them visible to anyone, regardless of whether or not the viewer has an account. Alternatively, LinkedIn controls what a viewer may see based on whether she or he has a paid account. Sites like MySpace allow users to choose whether they want their profile to be public or “Friends only.” Facebook takes a different approach—by default, users who are part of the same “network” can view each other’s profiles, unless a profile owner has decided to deny permission to those in their network. Structural variations around visibility and access are one of the primary ways that SNSs differentiate themselves from each other.

Timeline of the launch dates of many major SNSs and dates when community sites re-launched with SNS features

After joining a social network site, users are prompted to identify others in the system with whom they have a relationship. The label for these relationships differs depending on the site—popular terms include “Friends,” “Contacts,” and “Fans.” Most SNSs require bi-directional confirmation for Friendship, but some do not. These one-directional ties are sometimes labeled as “Fans” or “Followers,” but many sites call these Friends as well. The term “Friends” can be misleading, because the connection does not necessarily mean friendship in the everyday vernacular sense, and the reasons people connect are varied ( boyd, 2006a ).

The public display of connections is a crucial component of SNSs. The Friends list contains links to each Friend’s profile, enabling viewers to traverse the network graph by clicking through the Friends lists. On most sites, the list of Friends is visible to anyone who is permitted to view the profile, although there are exceptions. For instance, some MySpace users have hacked their profiles to hide the Friends display, and LinkedIn allows users to opt out of displaying their network.

Most SNSs also provide a mechanism for users to leave messages on their Friends’ profiles. This feature typically involves leaving “comments,” although sites employ various labels for this feature. In addition, SNSs often have a private messaging feature similar to webmail. While both private messages and comments are popular on most of the major SNSs, they are not universally available.

Not all social network sites began as such. QQ started as a Chinese instant messaging service, LunarStorm as a community site, Cyworld as a Korean discussion forum tool, and Skyrock (formerly Skyblog) was a French blogging service before adding SNS features. Classmates.com , a directory of school affiliates launched in 1995, began supporting articulated lists of Friends after SNSs became popular. AsianAvenue, MiGente, and BlackPlanet were early popular ethnic community sites with limited Friends functionality before re-launching in 2005–2006 with SNS features and structure.

Beyond profiles, Friends, comments, and private messaging, SNSs vary greatly in their features and user base. Some have photo-sharing or video-sharing capabilities; others have built-in blogging and instant messaging technology. There are mobile-specific SNSs (e.g., Dodgeball), but some web-based SNSs also support limited mobile interactions (e.g., Facebook, MySpace, and Cyworld). Many SNSs target people from specific geographical regions or linguistic groups, although this does not always determine the site’s constituency. Orkut, for example, was launched in the United States with an English-only interface, but Portuguese-speaking Brazilians quickly became the dominant user group ( Kopytoff, 2004 ). Some sites are designed with specific ethnic, religious, sexual orientation, political, or other identity-driven categories in mind. There are even SNSs for dogs (Dogster) and cats (Catster), although their owners must manage their profiles.

While SNSs are often designed to be widely accessible, many attract homogeneous populations initially, so it is not uncommon to find groups using sites to segregate themselves by nationality, age, educational level, or other factors that typically segment society (Hargittai, this issue), even if that was not the intention of the designers.

The Early Years

According to the definition above, the first recognizable social network site launched in 1997. SixDegrees.com allowed users to create profiles, list their Friends and, beginning in 1998, surf the Friends lists. Each of these features existed in some form before SixDegrees, of course. Profiles existed on most major dating sites and many community sites. AIM and ICQ buddy lists supported lists of Friends, although those Friends were not visible to others. Classmates.com allowed people to affiliate with their high school or college and surf the network for others who were also affiliated, but users could not create profiles or list Friends until years later. SixDegrees was the first to combine these features.

SixDegrees promoted itself as a tool to help people connect with and send messages to others. While SixDegrees attracted millions of users, it failed to become a sustainable business and, in 2000, the service closed. Looking back, its founder believes that SixDegrees was simply ahead of its time (A. Weinreich, personal communication, July 11, 2007). While people were already flocking to the Internet, most did not have extended networks of friends who were online. Early adopters complained that there was little to do after accepting Friend requests, and most users were not interested in meeting strangers.

From 1997 to 2001, a number of community tools began supporting various combinations of profiles and publicly articulated Friends. AsianAvenue, BlackPlanet, and MiGente allowed users to create personal, professional, and dating profiles—users could identify Friends on their personal profiles without seeking approval for those connections (O. Wasow, personal communication, August 16, 2007). Likewise, shortly after its launch in 1999, LiveJournal listed one-directional connections on user pages. LiveJournal’s creator suspects that he fashioned these Friends after instant messaging buddy lists (B. Fitzpatrick, personal communication, June 15, 2007)—on LiveJournal, people mark others as Friends to follow their journals and manage privacy settings. The Korean virtual worlds site Cyworld was started in 1999 and added SNS features in 2001, independent of these other sites (see Kim & Yun, this issue). Likewise, when the Swedish web community LunarStorm refashioned itself as an SNS in 2000, it contained Friends lists, guestbooks, and diary pages (D. Skog, personal communication, September 24, 2007).

The next wave of SNSs began when Ryze.com was launched in 2001 to help people leverage their business networks. Ryze’s founder reports that he first introduced the site to his friends—primarily members of the San Francisco business and technology community, including the entrepreneurs and investors behind many future SNSs (A. Scott, personal communication, June 14, 2007). In particular, the people behind Ryze, Tribe.net , LinkedIn, and Friendster were tightly entwined personally and professionally. They believed that they could support each other without competing ( Festa, 2003 ). In the end, Ryze never acquired mass popularity, Tribe.net grew to attract a passionate niche user base, LinkedIn became a powerful business service, and Friendster became the most significant, if only as “one of the biggest disappointments in Internet history” ( Chafkin, 2007 , p. 1).

Like any brief history of a major phenomenon, ours is necessarily incomplete. In the following section we discuss Friendster, MySpace, and Facebook, three key SNSs that shaped the business, cultural, and research landscape.

The Rise (and Fall) of Friendster

Friendster launched in 2002 as a social complement to Ryze. It was designed to compete with Match.com , a profitable online dating site ( Cohen, 2003 ). While most dating sites focused on introducing people to strangers with similar interests, Friendster was designed to help friends-of-friends meet, based on the assumption that friends-of-friends would make better romantic partners than would strangers (J. Abrams, personal communication, March 27, 2003). Friendster gained traction among three groups of early adopters who shaped the site—bloggers, attendees of the Burning Man arts festival, and gay men ( boyd, 2004 )—and grew to 300,000 users through word of mouth before traditional press coverage began in May 2003 ( O’Shea, 2003 ).

As Friendster’s popularity surged, the site encountered technical and social difficulties ( boyd, 2006b ). Friendster’s servers and databases were ill-equipped to handle its rapid growth, and the site faltered regularly, frustrating users who replaced email with Friendster. Because organic growth had been critical to creating a coherent community, the onslaught of new users who learned about the site from media coverage upset the cultural balance. Furthermore, exponential growth meant a collapse in social contexts: Users had to face their bosses and former classmates alongside their close friends. To complicate matters, Friendster began restricting the activities of its most passionate users.

The initial design of Friendster restricted users from viewing profiles of people who were more than four degrees away (friends-of-friends-of-friends-of-friends). In order to view additional profiles, users began adding acquaintances and interesting-looking strangers to expand their reach. Some began massively collecting Friends, an activity that was implicitly encouraged through a “most popular” feature. The ultimate collectors were fake profiles representing iconic fictional characters: celebrities, concepts, and other such entities. These “Fakesters” outraged the company, who banished fake profiles and eliminated the “most popular” feature ( boyd, in press-b ). While few people actually created Fakesters, many more enjoyed surfing Fakesters for entertainment or using functional Fakesters (e.g., “Brown University”) to find people they knew.

The active deletion of Fakesters (and genuine users who chose non-realistic photos) signaled to some that the company did not share users’ interests. Many early adopters left because of the combination of technical difficulties, social collisions, and a rupture of trust between users and the site ( boyd, 2006b ). However, at the same time that it was fading in the U.S., its popularity skyrocketed in the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia ( Goldberg, 2007 ).

SNSs Hit the Mainstream

From 2003 onward, many new SNSs were launched, prompting social software analyst Clay Shirky (2003) to coin the term YASNS: “Yet Another Social Networking Service.” Most took the form of profile-centric sites, trying to replicate the early success of Friendster or target specific demographics. While socially-organized SNSs solicit broad audiences, professional sites such as LinkedIn, Visible Path, and Xing (formerly openBC) focus on business people. “Passion-centric” SNSs like Dogster (T. Rheingold, personal communication, August 2, 2007) help strangers connect based on shared interests. Care2 helps activists meet, Couchsurfing connects travelers to people with couches, and MyChurch joins Christian churches and their members. Furthermore, as the social media and user-generated content phenomena grew, websites focused on media sharing began implementing SNS features and becoming SNSs themselves. Examples include Flickr (photo sharing), Last.FM (music listening habits), and YouTube (video sharing).

With the plethora of venture-backed startups launching in Silicon Valley, few people paid attention to SNSs that gained popularity elsewhere, even those built by major corporations. For example, Google’s Orkut failed to build a sustainable U.S. user base, but a “Brazilian invasion” ( Fragoso, 2006 ) made Orkut the national SNS of Brazil. Microsoft’s Windows Live Spaces (a.k.a. MSN Spaces) also launched to lukewarm U.S. reception but became extremely popular elsewhere.

Few analysts or journalists noticed when MySpace launched in Santa Monica, California, hundreds of miles from Silicon Valley. MySpace was begun in 2003 to compete with sites like Friendster, Xanga, and AsianAvenue, according to co-founder Tom Anderson (personal communication, August 2, 2007); the founders wanted to attract estranged Friendster users (T. Anderson, personal communication, February 2, 2006). After rumors emerged that Friendster would adopt a fee-based system, users posted Friendster messages encouraging people to join alternate SNSs, including Tribe.net and MySpace (T. Anderson, personal communication, August 2, 2007). Because of this, MySpace was able to grow rapidly by capitalizing on Friendster’s alienation of its early adopters. One particularly notable group that encouraged others to switch were indie-rock bands who were expelled from Friendster for failing to comply with profile regulations.

While MySpace was not launched with bands in mind, they were welcomed. Indie-rock bands from the Los Angeles region began creating profiles, and local promoters used MySpace to advertise VIP passes for popular clubs. Intrigued, MySpace contacted local musicians to see how they could support them (T. Anderson, personal communication, September 28, 2006). Bands were not the sole source of MySpace growth, but the symbiotic relationship between bands and fans helped MySpace expand beyond former Friendster users. The bands-and-fans dynamic was mutually beneficial: Bands wanted to be able to contact fans, while fans desired attention from their favorite bands and used Friend connections to signal identity and affiliation.

Futhermore, MySpace differentiated itself by regularly adding features based on user demand ( boyd, 2006b ) and by allowing users to personalize their pages. This “feature” emerged because MySpace did not restrict users from adding HTML into the forms that framed their profiles; a copy/paste code culture emerged on the web to support users in generating unique MySpace backgrounds and layouts ( Perkel, in press ).

Teenagers began joining MySpace en masse in 2004. Unlike older users, most teens were never on Friendster—some joined because they wanted to connect with their favorite bands; others were introduced to the site through older family members. As teens began signing up, they encouraged their friends to join. Rather than rejecting underage users, MySpace changed its user policy to allow minors. As the site grew, three distinct populations began to form: musicians/artists, teenagers, and the post-college urban social crowd. By and large, the latter two groups did not interact with one another except through bands. Because of the lack of mainstream press coverage during 2004, few others noticed the site’s growing popularity.

Then, in July 2005, News Corporation purchased MySpace for $580 million ( BBC, 2005 ), attracting massive media attention. Afterwards, safety issues plagued MySpace. The site was implicated in a series of sexual interactions between adults and minors, prompting legal action ( Consumer Affairs, 2006 ). A moral panic concerning sexual predators quickly spread ( Bahney, 2006 ), although research suggests that the concerns were exaggerated. 2

A Global Phenomenon

While MySpace attracted the majority of media attention in the U.S. and abroad, SNSs were proliferating and growing in popularity worldwide. Friendster gained traction in the Pacific Islands, Orkut became the premier SNS in Brazil before growing rapidly in India ( Madhavan, 2007 ), Mixi attained widespread adoption in Japan, LunarStorm took off in Sweden, Dutch users embraced Hyves, Grono captured Poland, Hi5 was adopted in smaller countries in Latin America, South America, and Europe, and Bebo became very popular in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. Additionally, previously popular communication and community services began implementing SNS features. The Chinese QQ instant messaging service instantly became the largest SNS worldwide when it added profiles and made friends visible ( McLeod, 2006 ), while the forum tool Cyworld cornered the Korean market by introducing homepages and buddies ( Ewers, 2006 ).

Blogging services with complete SNS features also became popular. In the U.S., blogging tools with SNS features, such as Xanga, LiveJournal, and Vox, attracted broad audiences. Skyrock reigns in France, and Windows Live Spaces dominates numerous markets worldwide, including in Mexico, Italy, and Spain. Although SNSs like QQ, Orkut, and Live Spaces are just as large as, if not larger than, MySpace, they receive little coverage in U.S. and English-speaking media, making it difficult to track their trajectories.

Expanding Niche Communities

Alongside these open services, other SNSs launched to support niche demographics before expanding to a broader audience. Unlike previous SNSs, Facebook was designed to support distinct college networks only. Facebook began in early 2004 as a Harvard-only SNS ( Cassidy, 2006 ). To join, a user had to have a harvard.edu email address. As Facebook began supporting other schools, those users were also required to have university email addresses associated with those institutions, a requirement that kept the site relatively closed and contributed to users’ perceptions of the site as an intimate, private community.

Beginning in September 2005, Facebook expanded to include high school students, professionals inside corporate networks, and, eventually, everyone. The change to open signup did not mean that new users could easily access users in closed networks—gaining access to corporate networks still required the appropriate .com address, while gaining access to high school networks required administrator approval. (As of this writing, only membership in regional networks requires no permission.) Unlike other SNSs, Facebook users are unable to make their full profiles public to all users. Another feature that differentiates Facebook is the ability for outside developers to build “Applications” which allow users to personalize their profiles and perform other tasks, such as compare movie preferences and chart travel histories.

While most SNSs focus on growing broadly and exponentially, others explicitly seek narrower audiences. Some, like aSmallWorld and BeautifulPeople, intentionally restrict access to appear selective and elite. Others—activity-centered sites like Couchsurfing, identity-driven sites like BlackPlanet, and affiliation-focused sites like MyChurch—are limited by their target demographic and thus tend to be smaller. Finally, anyone who wishes to create a niche social network site can do so on Ning, a platform and hosting service that encourages users to create their own SNSs.

Currently, there are no reliable data regarding how many people use SNSs, although marketing research indicates that SNSs are growing in popularity worldwide ( comScore, 2007 ). This growth has prompted many corporations to invest time and money in creating, purchasing, promoting, and advertising SNSs. At the same time, other companies are blocking their employees from accessing the sites. Additionally, the U.S. military banned soldiers from accessing MySpace ( Frosch, 2007 ) and the Canadian government prohibited employees from Facebook ( Benzie, 2007 ), while the U.S. Congress has proposed legislation to ban youth from accessing SNSs in schools and libraries ( H.R. 5319, 2006 ; S. 49, 2007 ).

The rise of SNSs indicates a shift in the organization of online communities. While websites dedicated to communities of interest still exist and prosper, SNSs are primarily organized around people, not interests. Early public online communities such as Usenet and public discussion forums were structured by topics or according to topical hierarchies, but social network sites are structured as personal (or “egocentric”) networks, with the individual at the center of their own community. This more accurately mirrors unmediated social structures, where “the world is composed of networks, not groups” ( Wellman, 1988 , p. 37). The introduction of SNS features has introduced a new organizational framework for online communities, and with it, a vibrant new research context.

Scholarship concerning SNSs is emerging from diverse disciplinary and methodological traditions, addresses a range of topics, and builds on a large body of CMC research. The goal of this section is to survey research that is directly concerned with social network sites, and in so doing, to set the stage for the articles in this special issue. To date, the bulk of SNS research has focused on impression management and friendship performance, networks and network structure, online/offline connections, and privacy issues.

Impression Management and Friendship Performance

Like other online contexts in which individuals are consciously able to construct an online representation of self—such as online dating profiles and MUDS—SNSs constitute an important research context for scholars investigating processes of impression management, self-presentation, and friendship performance. In one of the earliest academic articles on SNSs, boyd (2004) examined Friendster as a locus of publicly articulated social networks that allowed users to negotiate presentations of self and connect with others. Donath and boyd (2004) extended this to suggest that “public displays of connection” serve as important identity signals that help people navigate the networked social world, in that an extended network may serve to validate identity information presented in profiles.

While most sites encourage users to construct accurate representations of themselves, participants do this to varying degrees. Marwick (2005) found that users on three different SNSs had complex strategies for negotiating the rigidity of a prescribed “authentic” profile, while boyd (in press-b) examined the phenomenon of “Fakesters” and argued that profiles could never be “real.” The extent to which portraits are authentic or playful varies across sites; both social and technological forces shape user practices. Skog (2005) found that the status feature on LunarStorm strongly influenced how people behaved and what they choose to reveal—profiles there indicate one’s status as measured by activity (e.g., sending messages) and indicators of authenticity (e.g., using a “real” photo instead of a drawing).

Another aspect of self-presentation is the articulation of friendship links, which serve as identity markers for the profile owner. Impression management is one of the reasons given by Friendster users for choosing particular friends ( Donath & boyd, 2004 ). Recognizing this, Zinman and Donath (2007) noted that MySpace spammers leverage people’s willingness to connect to interesting people to find targets for their spam.

In their examination of LiveJournal “friendship,” Fono and Raynes-Goldie (2006) described users’ understandings regarding public displays of connections and how the Friending function can operate as a catalyst for social drama. In listing user motivations for Friending, boyd (2006a) points out that “Friends” on SNSs are not the same as “friends” in the everyday sense; instead, Friends provide context by offering users an imagined audience to guide behavioral norms. Other work in this area has examined the use of Friendster Testimonials as self-presentational devices ( boyd & Heer, 2006 ) and the extent to which the attractiveness of one’s Friends (as indicated by Facebook’s “Wall” feature) impacts impression formation ( Walther, Van Der Heide, Kim, & Westerman, in press ).

Networks and Network Structure

Social network sites also provide rich sources of naturalistic behavioral data. Profile and linkage data from SNSs can be gathered either through the use of automated collection techniques or through datasets provided directly from the company, enabling network analysis researchers to explore large-scale patterns of friending, usage, and other visible indicators ( Hogan, in press ), and continuing an analysis trend that started with examinations of blogs and other websites. For instance, Golder, Wilkinson, and Huberman (2007) examined an anonymized dataset consisting of 362 million messages exchanged by over four million Facebook users for insight into Friending and messaging activities. Lampe, Ellison, and Steinfield (2007) explored the relationship between profile elements and number of Facebook friends, finding that profile fields that reduce transaction costs and are harder to falsify are most likely to be associated with larger number of friendship links. These kinds of data also lend themselves well to analysis through network visualization ( Adamic, Buyukkokten, & Adar, 2003 ; Heer & boyd, 2005 ; Paolillo & Wright, 2005 ).

SNS researchers have also studied the network structure of Friendship. Analyzing the roles people played in the growth of Flickr and Yahoo! 360’s networks, Kumar, Novak, and Tomkins (2006) argued that there are passive members, inviters, and linkers “who fully participate in the social evolution of the network” (p. 1). Scholarship concerning LiveJournal’s network has included a Friendship classification scheme ( Hsu, Lancaster, Paradesi, & Weniger, 2007 ), an analysis of the role of language in the topology of Friendship ( Herring et al., 2007 ), research into the importance of geography in Friending ( Liben-Nowell, Novak, Kumar, Raghavan, and Tomkins, 2005 ), and studies on what motivates people to join particular communities ( Backstrom, Huttenlocher, Kleinberg, & Lan, 2006 ). Based on Orkut data, Spertus, Sahami, and Buyukkokten (2005) identified a topology of users through their membership in certain communities; they suggest that sites can use this to recommend additional communities of interest to users. Finally, Liu, Maes, and Davenport (2006) argued that Friend connections are not the only network structure worth investigating. They examined the ways in which the performance of tastes (favorite music, books, film, etc.) constitutes an alternate network structure, which they call a “taste fabric.”

Bridging Online and Offline Social Networks

Although exceptions exist, the available research suggests that most SNSs primarily support pre-existing social relations. Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe (2007) suggest that Facebook is used to maintain existing offline relationships or solidify offline connections, as opposed to meeting new people. These relationships may be weak ties, but typically there is some common offline element among individuals who friend one another, such as a shared class at school. This is one of the chief dimensions that differentiate SNSs from earlier forms of public CMC such as newsgroups ( Ellison et al., 2007 ). Research in this vein has investigated how online interactions interface with offline ones. For instance, Lampe, Ellison, and Steinfield (2006) found that Facebook users engage in “searching” for people with whom they have an offline connection more than they “browse” for complete strangers to meet. Likewise, Pew research found that 91% of U.S. teens who use SNSs do so to connect with friends ( Lenhart & Madden, 2007 ).

Given that SNSs enable individuals to connect with one another, it is not surprising that they have become deeply embedded in user’s lives. In Korea, Cyworld has become an integral part of everyday life— Choi (2006) found that 85% of that study’s respondents “listed the maintenance and reinforcement of pre-existing social networks as their main motive for Cyworld use” (p. 181). Likewise, boyd (2008) argues that MySpace and Facebook enable U.S. youth to socialize with their friends even when they are unable to gather in unmediated situations; she argues that SNSs are “networked publics” that support sociability, just as unmediated public spaces do.

Popular press coverage of SNSs has emphasized potential privacy concerns, primarily concerning the safety of younger users ( George, 2006 ; Kornblum & Marklein, 2006 ). Researchers have investigated the potential threats to privacy associated with SNSs. In one of the first academic studies of privacy and SNSs, Gross and Acquisti (2005) analyzed 4,000 Carnegie Mellon University Facebook profiles and outlined the potential threats to privacy contained in the personal information included on the site by students, such as the potential ability to reconstruct users’ social security numbers using information often found in profiles, such as hometown and date of birth.

Acquisti and Gross (2006) argue that there is often a disconnect between students’ desire to protect privacy and their behaviors, a theme that is also explored in Stutzman’s (2006) survey of Facebook users and Barnes’s (2006) description of the “privacy paradox” that occurs when teens are not aware of the public nature of the Internet. In analyzing trust on social network sites, Dwyer, Hiltz, and Passerini (2007) argued that trust and usage goals may affect what people are willing to share—Facebook users expressed greater trust in Facebook than MySpace users did in MySpace and thus were more willing to share information on the site.

In another study examining security issues and SNSs, Jagatic, Johnson, Jakobsson, and Menczer (2007) used freely accessible profile data from SNSs to craft a “phishing” scheme that appeared to originate from a friend on the network; their targets were much more likely to give away information to this “friend” than to a perceived stranger. Survey data offer a more optimistic perspective on the issue, suggesting that teens are aware of potential privacy threats online and that many are proactive about taking steps to minimize certain potential risks. Pew found that 55% of online teens have profiles, 66% of whom report that their profile is not visible to all Internet users ( Lenhart & Madden, 2007 ). Of the teens with completely open profiles, 46% reported including at least some false information.

Privacy is also implicated in users’ ability to control impressions and manage social contexts. Boyd (in press-a) asserted that Facebook’s introduction of the “News Feed” feature disrupted students’ sense of control, even though data exposed through the feed were previously accessible. Preibusch, Hoser, Gürses, and Berendt (2007) argued that the privacy options offered by SNSs do not provide users with the flexibility they need to handle conflicts with Friends who have different conceptions of privacy; they suggest a framework for privacy in SNSs that they believe would help resolve these conflicts.

SNSs are also challenging legal conceptions of privacy. Hodge (2006) argued that the fourth amendment to the U.S. Constitution and legal decisions concerning privacy are not equipped to address social network sites. For example, do police officers have the right to access content posted to Facebook without a warrant? The legality of this hinges on users’ expectation of privacy and whether or not Facebook profiles are considered public or private.

Other Research

In addition to the themes identified above, a growing body of scholarship addresses other aspects of SNSs, their users, and the practices they enable. For example, scholarship on the ways in which race and ethnicity ( Byrne, in press ; Gajjala, 2007 ), religion ( Nyland & Near, 2007 ), gender ( Geidner, Flook, & Bell, 2007 ; Hjorth & Kim, 2005 ), and sexuality connect to, are affected by, and are enacted in social network sites raise interesting questions about how identity is shaped within these sites. Fragoso (2006) examined the role of national identity in SNS use through an investigation into the “Brazilian invasion” of Orkut and the resulting culture clash between Brazilians and Americans on the site. Other scholars are beginning to do cross-cultural comparisons of SNS use— Hjorth and Yuji (in press) compare Japanese usage of Mixi and Korean usage of Cyworld, while Herring et al. (2007) examine the practices of users who bridge different languages on LiveJournal—but more work in this area is needed.

Scholars are documenting the implications of SNS use with respect to schools, universities, and libraries. For example, scholarship has examined how students feel about having professors on Facebook ( Hewitt & Forte, 2006 ) and how faculty participation affects student-professor relations ( Mazer, Murphy, & Simonds, 2007 ). Charnigo and Barnett-Ellis (2007) found that librarians are overwhelmingly aware of Facebook and are against proposed U.S. legislation that would ban minors from accessing SNSs at libraries, but that most see SNSs as outside the purview of librarianship. Finally, challenging the view that there is nothing educational about SNSs, Perkel (in press) analyzed copy/paste practices on MySpace as a form of literacy involving social and technical skills.

This overview is not comprehensive due to space limitations and because much work on SNSs is still in the process of being published. Additionally, we have not included literature in languages other than English (e.g., Recuero, 2005 on social capital and Orkut), due to our own linguistic limitations.

The articles in this section address a variety of social network sites—BlackPlanet, Cyworld, Dodgeball, Facebook, MySpace, and YouTube—from multiple theoretical and methodological angles, building on previous studies of SNSs and broader theoretical traditions within CMC research, including relationship maintenance and issues of identity, performance, privacy, self-presentation, and civic engagement.

These pieces collectively provide insight into some of the ways in which online and offline experiences are deeply entwined. Using a relational dialectics approach, Kyung-Hee Kim and Haejin Yun analyze how Cyworld supports both interpersonal relations and self-relation for Korean users. They trace the subtle ways in which deeply engrained cultural beliefs and activities are integrated into online communication and behaviors on Cyworld—the online context reinforces certain aspects of users’ cultural expectations about relationship maintenance (e.g., the concept of reciprocity), while the unique affordances of Cyworld enable participants to overcome offline constraints. Dara Byrne uses content analysis to examine civic engagement in forums on BlackPlanet and finds that online discussions are still plagued with the problems offline activists have long encountered. Drawing on interview and observation data, Lee Humphreys investigates early adopters’ practices involving Dodgeball, a mobile social network service. She looks at the ways in which networked communication is reshaping offline social geography.

Other articles in this collection illustrate how innovative research methods can elucidate patterns of behavior that would be indistinguishable otherwise. For instance, Hugo Liu examines participants’ performance of tastes and interests by analyzing and modeling the preferences listed on over 127,000 MySpace profiles, resulting in unique “taste maps.” Likewise, through survey data collected at a college with diverse students in the U.S., Eszter Hargittai illuminates usage patterns that would otherwise be masked. She finds that adoption of particular services correlates with individuals’ race and parental education level.

Existing theory is deployed, challenged, and extended by the approaches adopted in the articles in this section. Judith Donath extends signaling theory to explain different tactics SNS users adopt to reduce social costs while managing trust and identity. She argues that the construction and maintenance of relations on SNSs is akin to “social grooming.” Patricia Lange complicates traditional dichotomies between “public” and “private” by analyzing how YouTube participants blur these lines in their video-sharing practices.

The articles in this collection highlight the significance of social network sites in the lives of users and as a topic of research. Collectively, they show how networked practices mirror, support, and alter known everyday practices, especially with respect to how people present (and hide) aspects of themselves and connect with others. The fact that participation on social network sites leaves online traces offers unprecedented opportunities for researchers. The scholarship in this special theme section takes advantage of this affordance, resulting in work that helps explain practices online and offline, as well as those that blend the two environments.

The work described above and included in this special theme section contributes to an on-going dialogue about the importance of social network sites, both for practitioners and researchers. Vast, uncharted waters still remain to be explored. Methodologically, SNS researchers’ ability to make causal claims is limited by a lack of experimental or longitudinal studies. Although the situation is rapidly changing, scholars still have a limited understanding of who is and who is not using these sites, why, and for what purposes, especially outside the U.S. Such questions will require large-scale quantitative and qualitative research. Richer, ethnographic research on populations more difficult to access (including non-users) would further aid scholars’ ability to understand the long-term implications of these tools. We hope that the work described here and included in this collection will help build a foundation for future investigations of these and other important issues surrounding social network sites.

We are grateful to the external reviewers who volunteered their time and expertise to review papers and contribute valuable feedback and to those practitioners and analysts who provided information to help shape the history section. Thank you also to Susan Herring, whose patience and support appeared infinite.

To differentiate the articulated list of Friends on SNSs from the colloquial term “friends,” we capitalize the former.

Although one out of seven teenagers received unwanted sexual solicitations online, only 9% came from people over the age of 25 ( Wolak, Mitchell, & Finkelhor, 2006 ). Research suggests that popular narratives around sexual predators on SNSs are misleading—cases of unsuspecting teens being lured by sexual predators are rare ( Finkelhor, Ybarra, Lenhart, boyd, & Lordan, 2007 ). Furthermore, only .08% of students surveyed by the National School Boards Association (2007) met someone in person from an online encounter without permission from a parent.

Acquisti , A. , & Gross , R . ( 2006 ). Imagined communities: Awareness, information sharing, and privacy on the Facebook . In P. Golle & G. Danezis (Eds.), Proceedings of 6th Workshop on Privacy Enhancing Technologies (pp. 36 – 58 ). Cambridge, UK : Robinson College .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Adamic , L. A. , Büyükkökten , O. , & Adar , E . ( 2003 ). A social network caught in the Web . First Monday , 8 ( 6 ). Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue8_6/adamic/index.html

Backstrom , L. , Huttenlocher , D. , Kleinberg , J. , & Lan , X . ( 2006 ). Group formation in large social networks: Membership, growth, and evolution . Proceedings of 12 th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining (pp. 44 – 54 ). New York : ACM Press .

Bahney , A . ( 2006 , March 9). Don’t talk to invisible strangers . New York Times . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/09/fashion/thursdaystyles/09parents.html

Barnes , S . ( 2006 ). A privacy paradox: Social networking in the United States . First Monday , 11 ( 9 ). Retrieved September 8, 2007 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue11_9/barnes/index.html

BBC . ( 2005, July 19 ). News Corp in $580m Internet buy . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4695495.stm

Benzie , R . ( 2007, May 3 ). Facebook banned for Ontario staffers . The Star . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.thestar.com/News/article/210014

boyd , d . ( 2004 ). Friendster and publicly articulated social networks . Proceedings of ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1279 – 1282 ). New York : ACM Press .

boyd , d . ( 2006a ). Friends, Friendsters, and MySpace Top 8: Writing community into being on social network sites . First Monday , 11 ( 12 ). Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue11_12/boyd/

boyd , d . ( 2006b, March 21 ). Friendster lost steam. Is MySpace just a fad? Apophenia Blog . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.danah.org/papers/FriendsterMySpaceEssay.html

boyd , d . (in press-a). Facebook’s privacy trainwreck: Exposure, invasion, and social convergence . Convergence , 14 ( 1 ).

boyd , d . (in press-b). None of this is real . In J. Karaganis (Ed.), Structures of Participation . New York : Social Science Research Council .

boyd , d . ( 2008 ). Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life . In D. Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, Identity, and Digital Media (pp. 119 – 142 ). Cambridge, MA : MIT Press .

boyd , d ., & Heer , J . ( 2006 ). Profiles as conversation: Networked identity performance on Friendster . Proceedings of Thirty-Ninth Hawai’i International Conference on System Sciences . Los Alamitos, CA : IEEE Press .

Byrne , D . (in press). The future of (the) ‘race’: Identity, discourse and the rise of computer-mediated public spheres . In A. Everett (Ed.), MacArthur Foundation Book Series on Digital Learning: Race and Ethnicity Volume (pp. 15 – 38 ). Cambridge, MA : MIT Press .

Cassidy , J . ( 2006, May 15 ). Me media: How hanging out on the Internet became big business . The New Yorker , 82 ( 13 ), 50.

Chafkin , M . ( 2007, June ). How to kill a great idea! Inc. Magazine . Retrieved August 27, 2007 from http://www.inc.com/magazine/20070601/features-how-to-kill-a-great-idea.html

Charnigo , L. , & Barnett-Ellis , P . ( 2007 ). Checking out Facebook.com : The impact of a digital trend on academic libraries . Information Technology and Libraries , 26 ( 1 ), 23.

Choi , J. H . ( 2006 ). Living in Cyworld : Contextualising Cy-Ties in South Korea . In A. Bruns & J. Jacobs (Eds.), Use of Blogs (Digital Formations) (pp. 173 – 186 ). New York : Peter Lang .

Cohen , R . ( 2003, July 5 ). Livewire: Web sites try to make internet dating less creepy . Reuters . Retrieved July 5, 2003 from http://asia.reuters.com/newsArticle.jhtml?type=internetNews&storyID=3041934

comScore . ( 2007 ). Social networking goes global . Reston, VA. Retrieved September 9, 2007 from http://www.comscore.com/press/release.asp?press=1555

Consumer Affairs . ( 2006, February 5 ). Connecticut opens MySpace.com probe. Consumer Affairs . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2006/02/myspace.html

Donath , J. , & boyd , d . ( 2004 ). Public displays of connection . BT Technology Journal , 22 ( 4 ), 71 – 82 .

Dwyer , C. , Hiltz , S. R. , & Passerini , K . ( 2007 ). Trust and privacy concern within social networking sites: A comparison of Facebook and MySpace . Proceedings of AMCIS 2007 , Keystone, CO. Retrieved September 21, 2007 from http://csis.pace.edu/~dwyer/research/DwyerAMCIS2007.pdf

Ellison , N. , Steinfield , C. , & Lampe , C . ( 2007 ). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Exploring the relationship between college students’ use of online social networks and social capital . Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication , 12 ( 3 ), article 1. Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol12/issue4/ellison.html

Ewers , J . ( 2006, November 9 ). Cyworld: Bigger than YouTube? U.S. News & World Report . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from LexisNexis .

Festa , P . ( 2003, November 11 ). Investors snub Friendster in patent grab . CNet News . Retrieved August 26, 2007 from http://news.com.com/2100-1032_3-5106136.html

Finkelhor , D. , Ybarra , M. , Lenhart , A. , boyd , d ., & Lordan , T . ( 2007, May 3 ). Just the facts about online youth victimization: Researchers present the facts and debunk myths . Internet Caucus Advisory Committee Event . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.netcaucus.org/events/2007/youth/20070503transcript.pdf

Fono , D. , & Raynes-Goldie , K . ( 2006 ). Hyperfriendship and beyond: Friends and social norms on LiveJournal . In M. Consalvo & C. Haythornthwaite (Eds.), Internet Research Annual Volume 4: Selected Papers from the AOIR Conference (pp. 91 – 103 ). New York : Peter Lang .

Fragoso , S . ( 2006 ). WTF a crazy Brazilian invasion . In F. Sudweeks & H. Hrachovec (Eds.), Proceedings of CATaC 2006 (pp. 255 – 274 ). Murdoch, Australia : Murdoch University .

Frosch , D . ( 2007, May 15 ). Pentagon blocks 13 web sites from military computers . New York Times . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/15/washington/15block.html

Gajjala , R . ( 2007 ). Shifting frames: Race, ethnicity, and intercultural communication in online social networking and virtual work . In M. B. Hinner (Ed.), The Role of Communication in Business Transactions and Relationships (pp. 257 – 276 ). New York : Peter Lang .

Geidner , N. W. , Flook , C. A. , & Bell , M. W . ( 2007, April ). Masculinity and online social networks: Male self-identification on Facebook.com . Paper presented at Eastern Communication Association 98th Annual Meeting, Providence, RI.

George , A . ( 2006, September 18 ). Living online: The end of privacy? New Scientist , 2569. Retrieved August 29, 2007 from http://www.newscientist.com/channel/tech/mg19125691.700-living-online-the-end-of-privacy.html

Goldberg , S . ( 2007, May 13 ). Analysis: Friendster is doing just fine . Digital Media Wire . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://www.dmwmedia.com/news/2007/05/14/analysis-friendster-is-doing-just-fine

Golder , S. A. , Wilkinson , D. , & Huberman , B. A . ( 2007, June ). Rhythms of social interaction: Messaging within a massive online network . In C. Steinfield , B. Pentland , M. Ackerman , & N. Contractor (Eds.), Proceedings of Third International Conference on Communities and Technologies (pp. 41 – 66 ). London : Springer .

Gross , R. , & Acquisti , A . ( 2005 ). Information revelation and privacy in online social networks . Proceedings of WPES’05 (pp. 71 – 80 ). Alexandria, VA : ACM .

Haythornthwaite , C . ( 2005 ). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects . Information, Communication, & Society , 8 ( 2 ), 125 – 147 .

Heer , J. , & boyd , d . ( 2005 ). Vizster: Visualizing online social networks . Proceedings of Symposium on Information Visualization (pp. 33 – 40 ). Minneapolis, MN : IEEE Press .

Herring , S. C. , Paolillo , J. C. , Ramos Vielba , I. , Kouper , I. , Wright , E. , Stoerger , S. , Scheidt , L. A. , & Clark , B . ( 2007 ). Language networks on LiveJournal . Proceedings of the Fortieth Hawai’i International Conference on System Sciences . Los Alamitos, CA : IEEE Press .

Hewitt , A. , & Forte , A . ( 2006, November ). Crossing boundaries: Identity management and student/faculty relationships on the Facebook . Poster presented at CSCW, Banff, Alberta.

Hjorth , L. , & Kim , H . ( 2005 ). Being there and being here: Gendered customising of mobile 3G practices through a case study in Seoul . Convergence , 11 ( 2 ), 49 – 55 .

Hjorth , L. , & Yuji , M . (in press). Logging on locality: A cross-cultural case study of virtual communities Mixi (Japan) and Mini-hompy (Korea) . In B. Smaill (Ed.), Youth and Media in the Asia Pacific . Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press .

Hodge , M. J . ( 2006 ). The Fourth Amendment and privacy issues on the “new” Internet: Facebook.com and MySpace.com . Southern Illinois University Law Journal , 31 , 95 – 122 .

Hogan , B . (in press). Analyzing social networks via the Internet . In N. Fielding , R. Lee , & G. Blank (Eds.), Sage Handbook of Online Research Methods . Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage .

H. R . 5319. ( 2006, May 9 ). Deleting Online Predators Act of 2006 . H.R. 5319, 109 th Congress. Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.govtrack.us/congress/billtext.xpd?bill=h109-5319

Hsu , W. H. , Lancaster , J. , Paradesi , M. S. R. , & Weninger , T . ( 2007 ). Structural link analysis from user profiles and friends networks: A feature construction approach . Proceedings of ICWSM-2007 (pp. 75 – 80 ). Boulder, CO.

Jagatic , T. , Johnson , N. , Jakobsson , M. , & Menczer , F . ( 2007 ). Social phishing . Communications of the ACM , 5 ( 10 ), 94 – 100 .

Kopytoff , V . ( 2004, November 29 ). Google’s orkut puzzles experts. San Francisco Chronicle . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2004/11/29/BUGU9A0BH441.DTL

Kornblum , J. , & Marklein , M. B . ( 2006, March 8 ). What you say online could haunt you . USA Today . Retrieved August 29, 2007 from http://www.usatoday.com/tech/news/internetprivacy/2006-03-08-facebook-myspace_x.htm

Kumar , R. , Novak , J. , & Tomkins , A . ( 2006 ). Structure and evolution of online social networks . Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining (pp. 611 – 617 ). New York : ACM Press .

Lampe , C. , Ellison , N. , & Steinfield , C . ( 2006 ). A Face(book) in the crowd: Social searching vs. social browsing . Proceedings of CSCW-2006 (pp. 167 – 170 ). New York : ACM Press .

Lampe , C. , Ellison , N. , & Steinfeld , C . ( 2007 ). A familiar Face(book): Profile elements as signals in an online social network . Proceedings of Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 435 – 444 ). New York : ACM Press .

Lenhart , A. , & Madden , M . ( 2007, April 18 ). Teens, privacy, & online social networks . Pew Internet and American Life Project Report . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Teens_Privacy_SNS_Report_Final.pdf

Liben-Nowell , D. , Novak , J. , Kumar , R. , Raghavan , P. , & Tomkins , A . ( 2005 ) Geographic routing in social networks . Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences , 102 ( 33 ) 11 ,623– 11 ,628.

Liu , H. , Maes , P. , & Davenport , G . ( 2006 ). Unraveling the taste fabric of social networks . International Journal on Semantic Web and Information Systems , 2 ( 1 ), 42 – 71 .

Madhavan , N . ( 2007, July 6 ). India gets more Net Cool . Hindustan Times . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://www.hindustantimes.com/StoryPage/StoryPage.aspx?id=f2565bb8-663e-48c1-94ee-d99567577bdd

Marwick , A . ( 2005, October ). “I’m a lot more interesting than a Friendster profile:” Identity presentation, authenticity, and power in social networking services . Paper presented at Internet Research 6.0, Chicago, IL.

Mazer , J. P. , Murphy , R. E. , & Simonds , C. J . ( 2007 ). I’ll see you on “Facebook:” The effects of computer-mediated teacher self-disclosure on student motivation, affective learning, and classroom climate . Communication Education , 56 ( 1 ), 1 – 17 .

McLeod , D . ( 2006, October 6 ). QQ Attracting eyeballs . Financial Mail (South Africa) , p. 36 . Retrieved July 30, 2007 from LexisNexis.

National School Boards Association . ( 2007, July ). Creating and connecting: Research and guidelines on online social—and educational—networking . Alexandria, VA. Retrieved September 23, 2007 from http://www.nsba.org/site/docs/41400/41340.pdf

Nyland , R. , & Near , C . ( 2007, February ). Jesus is my friend: Religiosity as a mediating factor in Internet social networking use . Paper presented at AEJMC Midwinter Conference, Reno, NV.

O’Shea , W . ( 2003, July 4-10 ). Six Degrees of sexual frustration: Connecting the dates with Friendster.com . Village Voice . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.villagevoice.com/news/0323,oshea, 44576, 1.html

Paolillo , J. C. , & Wright , E . ( 2005 ). Social network analysis on the semantic web: Techniques and challenges for visualizing FOAF . In V. Geroimenko & C. Chen (Eds.), Visualizing the Semantic Web (pp. 229 – 242 ). Berlin : Springer .

Perkel , D . (in press). Copy and paste literacy? Literacy practices in the production of a MySpace profile . In K. Drotner , H. S. Jensen , & K. Schroeder (Eds.), Informal Learning and Digital Media: Constructions, Contexts, Consequences . Newcastle, UK : Cambridge Scholars Press .

Preibusch , S. , Hoser , B. , Gürses , S. , & Berendt , B . ( 2007, June ). Ubiquitous social networks—opportunities and challenges for privacy-aware user modelling . Proceedings of Workshop on Data Mining for User Modeling . Corfu, Greece. Retrieved October 20, 2007 from http://vasarely.wiwi.hu-berlin.de/DM.UM07/Proceedings/05-Preibusch.pdf

Recuero , R . ( 2005 ). O capital social em redes sociais na Internet . Revista FAMECOS , 28 , 88 – 106 . Retrieved September 13, 2007 from http://www.pucrs.br/famecos/pos/revfamecos/28/raquelrecuero.pdf

S. 49. ( 2007, January 4 ). Protecting Children in the 21 st Century Act . S. 49, 110 th Congress. Retrieved July 30, 2007 from http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/F?c110:1:./temp/~c110dJQpcy:e445 :

Shirky , C . ( 2003, May 13 ). People on page: YASNS… Corante’s Many-to-Many . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://many.corante.com/archives/2003/05/12/people_on_page_yasns.php

Skog , D . ( 2005 ). Social interaction in virtual communities: The significance of technology . International Journal of Web Based Communities , 1 ( 4 ), 464 – 474 .

Spertus , E. , Sahami , M. , & Buyukkokten , O . ( 2005 ). Evaluating similarity measures: A large-scale study in the orkut social network . Proceedings of 11 th International Conference on Knowledge Discovery in Data Mining (pp. 678 – 684 ). New York : ACM Press .

Stutzman , F . ( 2006 ). An evaluation of identity-sharing behavior in social network communities . Journal of the International Digital Media and Arts Association , 3 ( 1 ), 10 – 18 .

Sundén , J . ( 2003 ). Material Virtualities . New York : Peter Lang .

Walther , J. B. , Van Der Heide , B. , Kim , S. Y. , & Westerman , D . (in press). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep? Human Communication Research .

Wellman , B . ( 1988 ). Structural analysis: From method and metaphor to theory and substance . In B. Wellman & S. D. Berkowitz (Eds.), Social Structures: A Network Approach (pp. 19 – 61 ). Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press .

Wolak , J. , Mitchell , K. , & Finkelhor , D . ( 2006 ). Online victimization of youth: Five years later . Report from Crimes Against Children Research Center, University of New Hampshire . Retrieved July 21, 2007 from http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV138.pdf

Zinman , A. , & Donath , J . ( 2007, August ). Is Britney Spears spam? Paper presented at the Fourth Conference on Email and Anti-Spam, Mountain View, CA.

danah m. boyd is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Information at the University of California-Berkeley and a Fellow at the Harvard University Berkman Center for Internet and Society. Her research focuses on how people negotiate mediated contexts like social network sites for sociable purposes.

Address: 102 South Hall, Berkeley, CA 94720–4600, USA

Nicole B. Ellison is an assistant professor in the Department of Telecommunication, Information Studies, and Media at Michigan State University. Her research explores issues of self-presentation, relationship development, and identity in online environments such as weblogs, online dating sites, and social network sites.

Address: 403 Communication Arts and Sciences, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1083-6101

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Social Networking Sites Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on social networking sites.

Social networking sites are a great platform for people to connect with their loved ones. It helps in increasing communication and making connections with people all over the world. Although people believe that social networking sites are harmful, they are also very beneficial.

Furthermore, we can classify social networking sites as per blogging, vlogging, podcasting and more. We use social networking sites for various uses. It helps us greatly; however, it also is very dangerous. We must monitor the use of social networking sites and limit their usage so it does not take over our lives.

Advantage and Disadvantages of Social Networking Sites

Social networking sites are everywhere now. In other words, they have taken over almost every sphere of life. They come with both, advantages as well as disadvantages. If we talk about the educational field, these sites enhance education by having an influence on the learners. They can explore various topics for their projects.