Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop (2011)

Chapter: 3 assessing interpersonal skills.

Assessing Interpersonal Skills

The second cluster of skills—broadly termed interpersonal skills—are those required for relating to other people. These sorts of skills have long been recognized as important for success in school and the workplace, said Stephen Fiore, professor at the University of Central Florida, who presented findings from a paper about these skills and how they might be assessed (Salas, Bedwell, and Fiore, 2011). 1 Advice offered by Dale Carnegie in the 1930s to those who wanted to “win friends and influence people,” for example, included the following: be a good listener; don’t criticize, condemn, or complain; and try to see things from the other person’s point of view. These are the same sorts of skills found on lists of 21st century skills today. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills includes numerous interpersonal capacities, such as working creatively with others, communicating clearly, and collaborating with others, among the skills students should learn as they progress from preschool through postsecondary study (see Box 3-1 for the definitions of the relevant skills in the organization’s P-21 Framework).

It seems clear that these are important skills, yet definitive labels and definitions for the interpersonal skills important for success in schooling and work remain elusive: They have been called social or people skills, social competencies, soft skills, social self-efficacy, and social intelligence, Fiore said (see, e.g., Ferris, Witt, and Hochwarter, 2001; Hochwarter et al.,

________________

1 See http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Salas_Fiore_Paper.pdf [August 2011].

BOX 3-1 Interpersonal Capacities in the Partnership for 21st Century Skills Framework

Work Creatively with Others

- Develop, implement, and communicate new ideas to others effectively

- Be open and responsive to new and diverse perspectives; incorporate group input and feedback into the work

- Demonstrate originality and inventiveness in work and understand the real-world limits to adopting new ideas

- View failure as an opportunity to learn; understand that creativity and innovation is a long-term, cyclical process of small successes and frequent mistakes

Communicate Clearly

- Articulate thoughts and ideas effectively using oral, written, and nonverbal communication skills in a variety of forms and contexts

- Listen effectively to decipher meaning, including knowledge, values, attitudes, and intentions

- Use communication for a range of purposes (e.g., to inform, instruct, motivate, and persuade)

- Utilize multiple media and technologies, and know how to judge their effectiveness a priori as well as to assess their impact

- Communicate effectively in diverse environments (including multilingual)

Collaborate with Others

- Demonstrate ability to work effectively and respectfully with diverse teams

- Exercise flexibility and willingness to be helpful in making necessary compromises to accomplish a common goal

- Assume shared responsibility for collaborative work, and value the individual contributions made by each team member

2006; Klein et al., 2006; Riggio, 1986; Schneider, Ackerman, and Kanfer, 1996; Sherer et al., 1982; Sternberg, 1985; Thorndike, 1920). The previous National Research Council (NRC) workshop report that offered a preliminary definition of 21st century skills described one broad category of interpersonal skills (National Research Council, 2010, p. 3):

Complex communication/social skills: Skills in processing and interpreting both verbal and nonverbal information from others in order to respond appropriately. A skilled communicator is able to select key pieces of a complex idea to express in words, sounds, and images, in order to build shared understanding (Levy and Murnane, 2004). Skilled communicators negotiate positive outcomes with customers, subordinates, and superiors through social perceptiveness, persuasion, negotiation, instructing, and service orientation (Peterson et al., 1999).

Adapt to Change

- Adapt to varied roles, jobs responsibilities, schedules, and contexts

- Work effectively in a climate of ambiguity and changing priorities

Be Flexible

- Incorporate feedback effectively

- Deal positively with praise, setbacks, and criticism

- Understand, negotiate, and balance diverse views and beliefs to reach

- workable solutions, particularly in multicultural environments

Interact Effectively with Others

- Know when it is appropriate to listen and when to speak

- Conduct themselves in a respectable, professional manner

Work Effectively in Diverse Teams

- Respect cultural differences and work effectively with people from a range of social and cultural backgrounds

- Respond open-mindedly to different ideas and values

- Leverage social and cultural differences to create new ideas and increase both innovation and quality of work

Guide and Lead Others

- Use interpersonal and problem-solving skills to influence and guide others toward a goal

- Leverage strengths of others to accomplish a common goal

- Inspire others to reach their very best via example and selflessness

- Demonstrate integrity and ethical behavior in using influence and power

Be Responsible to Others

- Act responsibly with the interests of the larger community in mind

SOURCE: Excerpted from P21 Framework Definitions, Partnership for 21st Century Skills December 2009 [copyrighted—available at http://www.p21.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=254&Itemid=120 [August 2011].

These and other available definitions are not necessarily at odds, but in Fiore’s view, the lack of a single, clear definition reflects a lack of theoretical clarity about what they are, which in turn has hampered progress toward developing assessments of them. Nevertheless, appreciation for the importance of these skills—not just in business settings, but in scientific and technical collaboration, and in both K-12 and postsecondary education settings—has been growing. Researchers have documented benefits these skills confer, Fiore noted. For example, Goleman (1998) found they were twice as important to job performance as general cognitive ability. Sonnentag and Lange (2002) found understanding of cooperation strategies related to higher performance among engineering and software development teams, and Nash and colleagues (2003) showed that collaboration skills were key to successful interdisciplinary research among scientists.

WHAT ARE INTERPERSONAL SKILLS?

The multiplicity of names for interpersonal skills and ways of conceiving of them reflects the fact that these skills have attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive components, Fiore explained. It is useful to consider 21st century skills in basic categories (e.g., cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal), but it is still true that interpersonal skills draw on many capacities, such as knowledge of social customs and the capacity to solve problems associated with social expectations and interactions. Successful interpersonal behavior involves a continuous correction of social performance based on the reactions of others, and, as Richard Murnane had noted earlier, these are cognitively complex tasks. They also require self-regulation and other capacities that fall into the intrapersonal category (discussed in Chapter 4 ). Interpersonal skills could also be described as a form of “social intelligence,” specifically social perception and social cognition that involve processes such as attention and decoding. Accurate assessment, Fiore explained, may need to address these various facets separately.

The research on interpersonal skills has covered these facets, as researchers who attempted to synthesize it have shown. Fiore described the findings of a study (Klein, DeRouin, and Salas, 2006) that presented a taxonomy of interpersonal skills based on a comprehensive review of the literature. The authors found a variety of ways of measuring and categorizing such skills, as well as ways to link them both to outcomes and to personality traits and other factors that affect them. They concluded that interpersonal effectiveness requires various sorts of competence that derive from experience, instinct, and learning about specific social contexts. They put forward their own definition of interpersonal skills as “goal-directed behaviors, including communication and relationship-building competencies, employed in interpersonal interaction episodes characterized by complex perceptual and cognitive processes, dynamic verbal and non verbal interaction exchanges, diverse roles, motivations, and expectancies” (p. 81).

They also developed a model of interpersonal performance, shown in Figure 3-1 , that illustrates the interactions among the influences, such as personality traits, previous life experiences, and the characteristics of the situation; the basic communication and relationship-building skills the individual uses in the situation; and outcomes for the individual, the group, and the organization. To flesh out this model, the researchers distilled sets of skills for each area, as shown in Table 3-1 .

Fiore explained that because these frameworks focus on behaviors intended to attain particular social goals and draw on both attitudes and cognitive processes, they provide an avenue for exploring what goes into the development of effective interpersonal skills in an individual. They

TABLE 3-1 Taxonomy of Interpersonal Skills

SOURCE: Klein, DeRouin, and Salas (2006). Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

FIGURE 3-1 Model of interpersonal performance.

NOTE: Big Five personality traits = openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism; EI = emotional intelligence; IPS = interpersonal skills.

SOURCE: Stephen Fiore’s presentation. Klein, DeRouin, and Salas (2006). Copyright 2006, Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Reprinted with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

also allow for measurement of specific actions in a way that could be used in selection decisions, performance appraisals, or training. More specifically, Figure 3-1 sets up a way of thinking about these skills in the contexts in which they are used. The implication for assessment is that one would need to conduct the measurement in a suitable, realistic context in order to be able to examine the attitudes, cognitive processes, and behaviors that constitute social skills.

ASSESSMENT APPROACHES AND ISSUES

One way to assess these skills, Fiore explained, is to look separately at the different components (attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive). For example, as the model in Figure 3-1 indicates, previous life experiences, such as the opportunities an individual has had to engage in successful and unsuccessful social interactions, can be assessed through reports (e.g., personal statements from applicants or letters of recommendation from prior employers). If such narratives are written in response to specific

questions about types of interactions, they may provide indications of the degree to which an applicant has particular skills. However, it is likely to be difficult to distinguish clearly between specific social skills and personality traits, knowledge, and cognitive processes. Moreover, Fiore added, such narratives report on past experience and may not accurately portray how one would behave or respond in future experiences.

The research on teamwork (or collaboration)—a much narrower concept than interpersonal skills—has used questionnaires that ask people to rate themselves and also ask for peer ratings of others on dimensions such as communication, leadership, and self-management. For example, Kantrowitz (2005) collected self-report data on two scales: performance standards for various behaviors, and comparison to others in the subjects’ working groups. Loughry, Ohland, and Moore (2007) asked members of work teams in science and technical contexts to rate one another on five general categories: contribution to the team’s work; interaction with teammates; contribution to keeping the team on track; expectations for quality; and possession of relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Another approach, Fiore noted, is to use situational judgment tests (SJTs), which are multiple-choice assessments of possible reactions to hypothetical teamwork situations to assess capacities for conflict resolution, communication, and coordination, as Stevens and Campion (1999) have done. The researchers were able to demonstrate relationships between these results and both peers’ and supervisors’ ratings and to ratings of job performance. They were also highly correlated to employee aptitude test results.

Yet another approach is direct observation of team interactions. By observing directly, researchers can avoid the potential lack of reliability inherent in self- and peer reports, and can also observe the circumstances in which behaviors occur. For example, Taggar and Brown (2001) developed a set of scales related to conflict resolution, collaborative problem solving, and communication on which people could be rated.

Though each of these approaches involve ways of distinguishing specific aspects of behavior, it is still true, Fiore observed, that there is overlap among the constructs—skills or characteristics—to be measured. In his view, it is worth asking whether it is useful to be “reductionist” in parsing these skills. Perhaps more useful, he suggested, might be to look holistically at the interactions among the facets that contribute to these skills, though means of assessing in that way have yet to be determined. He enumerated some of the key challenges in assessing interpersonal skills.

The first concerns the precision, or degree of granularity, with which interpersonal expertise can be measured. Cognitive scientists have provided models of the progression from novice to expert in more concrete skill areas, he noted. In K-12 education contexts, assessment developers

have looked for ways to delineate expectations for particular stages that students typically go through as their knowledge and understanding grow more sophisticated. Hoffman (1998) has suggested the value of a similar continuum for interpersonal skills. Inspired by the craft guilds common in Europe during the Middle Ages, Hoffman proposed that assessment developers use the guidelines for novices, journeymen, and master craftsmen, for example, as the basis for operational definitions of developing social expertise. If such a continuum were developed, Fiore noted, it should make it possible to empirically examine questions about whether adults can develop and improve in response to training or other interventions.

Another issue is the importance of the context in which assessments of interpersonal skills are administered. By definition, these skills entail some sort of interaction with other people, but much current testing is done in an individualized way that makes it difficult to standardize. Sophisticated technology, such as computer simulations, or even simpler technology can allow for assessment of people’s interactions in a standardized scenario. For example, Smith-Jentsch and colleagues (1996) developed a simulation of an emergency room waiting room, in which test takers interacted with a video of actors following a script, while others have developed computer avatars that can interact in the context of scripted events. When well executed, Fiore explained, such simulations may be able to elicit emotional responses, allowing for assessment of people’s self-regulatory capacities and other so-called soft skills.

Workshop participants noted the complexity of trying to take the context into account in assessment. For example, one noted both that behaviors may make sense only in light of previous experiences in a particular environment, and that individuals may display very different social skills in one setting (perhaps one in which they are very comfortable) than another (in which they are not comfortable). Another noted that the clinical psychology literature would likely offer productive insights on such issues.

The potential for technologically sophisticated assessments also highlights the evolving nature of social interaction and custom. Generations who have grown up interacting via cell phone, social networking, and tweeting may have different views of social norms than their parents had. For example, Fiore noted, a telephone call demands a response, and many younger people therefore view a call as more intrusive and potentially rude than a text message, which one can respond to at his or her convenience. The challenge for researchers is both to collect data on new kinds of interactions and to consider new ways to link the content of interactions to the mode of communication, in order to follow changes in what constitutes skill at interpersonal interaction. The existing definitions

and taxonomies of interpersonal skills, he explained, were developed in the context of interactions that primarily occur face to face, but new technologies foster interactions that do not occur face to face or in a single time window.

In closing, Fiore returned to the conceptual slippage in the terms used to describe interpersonal skills. Noting that the etymological origins of both “cooperation” and “collaboration” point to a shared sense of working together, he explained that the word “coordination” has a different meaning, even though these three terms are often used as if they were synonymous. The word “coordination” captures instead the concepts of ordering and arranging—a key aspect of teamwork. These distinctions, he observed, are a useful reminder that examining the interactions among different facets of interpersonal skills requires clarity about each facet.

ASSESSMENT EXAMPLES

The workshop included examples of four different types of assessments of interpersonal skills intended for different educational and selection purposes—an online portfolio assessment designed for high school students; an online assessment for community college students; a situational judgment test used to select students for medical school in Belgium; and a collection of assessment center approaches used for employee selection, promotion, and training purposes.

The first example was the portfolio assessment used by the Envision High School in Oakland, California, to assess critical thinking, collaboration, communication, and creativity. At Envision Schools, a project-based learning approach is used that emphasizes the development of deeper learning skills, integration of arts and technology into core subjects, and real-world experience in workplaces. 2 The focus of the curriculum is to prepare students for college, especially those who would be the first in their family to attend college. All students are required to assemble a portfolio in order to graduate. Bob Lenz, cofounder of Envision High School, discussed this online portfolio assessment.

The second example was an online, scenario-based assessment used for community college students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs. The focus of the program is on developing students’ social/communication skills as well as their technical skills. Louise Yarnall, senior research scientist with SRI, made this presentation.

Filip Lievens, professor of psychology at Ghent University in Belgium, described the third example, a situational judgment test designed

2 See http://www.envisionschools.org/site/ [August 2011] for additional information about Envision Schools.

to assess candidates’ skill in responding to health-related situations that require interpersonal skills. The test is used for high-stakes purposes.

The final presentation was made by Lynn Gracin Collins, chief scientist for SH&A/Fenestra, who discussed a variety of strategies for assessing interpersonal skills in employment settings. She focused on performance-based assessments, most of which involve role-playing activities.

Online Portfolio Assessment of High School Students 3

Bob Lenz described the experience of incorporating in the curriculum and assessing several key interpersonal skills in an urban high school environment. Envision Schools is a program created with corporate and foundation funding to serve disadvantaged high school students. The program consists of four high schools in the San Francisco Bay area that together serve 1,350 primarily low-income students. Sixty-five percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and 70 percent are expected to be the first in their families to graduate from college. Most of the students, Lenz explained, enter the Envision schools at approximately a sixth-grade level in most areas. When they begin the Envision program, most have exceedingly negative feelings about school; as Lenz put it they “hate school and distrust adults.” The program’s mission is not only to address this sentiment about schools, but also to accelerate the students’ academic skills so that they can get into college and to develop the other skills they will need to succeed in life.

Lenz explained that tracking students’ progress after they graduate is an important tool for shaping the school’s approach to instruction. The first classes graduated from the Envision schools 2 years ago. Lenz reported that all of their students meet the requirements to attend a 4-year college in California (as opposed to 37 percent of public high school students statewide), and 94 percent of their graduates enrolled in 2- or 4-year colleges after graduation. At the time of the presentation, most of these students (95 percent) had re-enrolled for the second year of college. Lenz believes the program’s focus on assessment, particularly of 21st century skills, has been key to this success.

The program emphasizes what they call the “three Rs”: rigor, relevance, and relationships. Project-based assignments, group activities, and workplace projects are all activities that incorporate learning of interpersonal skills such as leadership, Lenz explained. Students are also asked to assess themselves regularly. Researchers from the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning, and Equity (SCALE) assisted the Envision staff in

3 Lenz’s presentation is available at http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Lenz.pdf [August 2011].

developing a College Success Assessment System that is embedded in the curriculum. Students develop portfolios with which they can demonstrate their learning in academic content as well as 21st century skill areas. The students are engaged in three goals: mastery knowledge, application of knowledge, and metacognition.

The components of the portfolio, which is presented at the end of 12th grade, include

- A student-written introduction to the contents

- Examples of “mastery-level” student work (assessed and certified by teachers prior to the presentation)

- Reflective summaries of work completed in five core content areas

- An artifact of and a written reflection on the workplace learning project

- A 21st century skills assessment

Students are also expected to defend their portfolios, and faculty are given professional development to guide the students in this process. Eventually, Lenz explained, the entire portfolio will be archived online.

Lenz showed examples of several student portfolios to demonstrate the ways in which 21st century skills, including interpersonal ones, are woven into both the curriculum and the assessments. In his view, teaching skills such as leadership and collaboration, together with the academic content, and holding the students to high expectations that incorporate these sorts of skills, is the best way to prepare the students to succeed in college, where there may be fewer faculty supports.

STEM Workforce Training Assessments 4

Louise Yarnall turned the conversation to assessment in a community college setting, where the technicians critical to many STEM fields are trained. She noted the most common approach to training for these workers is to engage them in hands-on practice with the technologies they are likely to encounter. This approach builds knowledge of basic technical procedures, but she finds that it does little to develop higher-order cognitive skills or the social skills graduates need to thrive in the workplace.

Yarnall and a colleague have outlined three categories of primary skills that technology employers seek in new hires (Yarnall and Ostrander, in press):

4 Yarnall’s presentation is available at http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Yarnall.pdf [August 2011].

Social-Technical

- Translating client needs into technical specifications

- Researching technical information to meet client needs

- Justifying or defending technical approach to client

- Reaching consensus on work team

- Polling work team to determine ideas

- Using tools, languages, and principles of domain

- Generating a product that meets specific technical criteria

- Interpreting problems using principles of domain

In her view, new strategies are needed to incorporate these skills into the community college curriculum. To build students’ technical skills and knowledge, she argued, faculty need to focus more on higher-order thinking and application of knowledge, to press students to demonstrate their competence, and to practice. Cooperative learning opportunities are key to developing social skills and knowledge. For the skills that are both social and technical, students need practice with reflection and feedback opportunities, modeling and scaffolding of desirable approaches, opportunities to see both correct and incorrect examples, and inquiry-based instructional practices.

She described a project she and colleagues, in collaboration with community college faculty, developed that was designed to incorporate this thinking, called the Scenario-Based Learning Project (see Box 3-2 ). This team developed eight workplace scenarios—workplace challenges that were complex enough to require a team response. The students are given a considerable amount of material with which to work. In order to succeed, they would need to figure out how to approach the problem, what they needed, and how to divide up the effort. Students are also asked to reflect on the results of the effort and make presentations about the solutions they have devised. The project begins with a letter from the workplace manager (the instructor plays this role and also provides feedback throughout the process) describing the problem and deliverables that need to be produced. For example, one task asked a team to produce a website for a bicycle club that would need multiple pages and links.

Yarnall noted they encountered a lot of resistance to this approach. Community college students are free to drop a class if they do not like the instructor’s approach, and because many instructors are adjunct faculty,

BOX 3-2 Sample Constructs, Evidence of Learning, and Assessment Task Features for Scenario-Based Learning Projects

Technical Skills

Sample knowledge/skills/abilities (KSAs):

Ability to document system requirements using a simplified use case format; ability to address user needs in specifying system requirements.

Sample evidence:

Presented with a list of user’s needs/uses, the student will correctly specify web functionalities that address each need.

Sample task features:

The task must engage students in the use of tools, procedures, and knowledge representations employed in Ajax programming; the assessment task requires students to summarize the intended solution.

Social Skills

Sample social skill KSAs:

Ability to listen to team members with different viewpoints and to propose a consensus.

Presented with a group of individuals charged with solving a problem, the student will demonstrate correctly indicators of active listening and collaboration skills, including listening attentively, waiting an adequate amount of time for problem solutions, summarizing ideas, and questioning to reach a decision.

Sample social skill characteristic task features:

The assessment task will be scenario-based and involve a group of individuals charged with solving a work-related problem. The assessment will involve a conflict among team members and require the social processes of listening, negotiation, and decision making.

Social-Technical Skills

Sample social-technical skill KSAs:

Ability to ask questions to specify user requirements, and ability to engage in software design brainstorming by generating examples of possible user interactions with the website.

Sample social-technical skill evidence:

Presented with a client interested in developing a website, the student will correctly define the user’s primary needs. Presented with a client interested in developing a website, the student will correctly define the range of possible uses for the website.

Sample social-technical skill characteristic task features:

The assessment task will be scenario-based and involve the design of a website with at least two constraints. The assessment task will require the use of “querying” to determine client needs. The assessment task will require a summation of client needs.

SOURCE: Adapted from Louise Yarnall’s presentation. Used with permission.

their positions are at risk if their classes are unpopular. Scenario-based learning can be risky, she explained, because it can be demanding, but at the same time students sometimes feel unsure that they are learning enough. Instructors also sometimes feel unprepared to manage the teams, give appropriate feedback, and track their students’ progress.

Furthermore, Yarnall continued, while many of the instructors did enjoy developing the projects, the need to incorporate assessment tools into the projects was the least popular aspect of the program. Traditional assessments in these settings tended to measure recall of isolated facts and technical procedures, and often failed to track the development or application of more complex cognitive skills and professional behaviors, Yarnall explained. She and her colleagues proposed some new approaches, based on the theoretical framework known as evidence-centered design. 5 Their goal was to guide the faculty in designing tasks that would elicit the full range of knowledge and skills they wanted to measure, and they turned to what are called reflection frameworks that had been used in other contexts to elicit complex sets of skills (Herman, Aschbacher, and Winters, 1992).

They settled on an interview format, which they called Evidence-Centered Assessment Reflection, to begin to identify the specific skills required in each field, to identify the assessment features that could produce evidence of specific kinds of learning, and then to begin developing specific prompts, stimuli, performance descriptions, and scoring rubrics for the learning outcomes they wanted to measure. The next step was to determine how the assessments would be delivered and how they would be validated. Assessment developers call this process a domain analysis—its purpose was to draw from the instructors a conceptual map of what they were teaching and particularly how social and social-technical skills fit into those domains.

Based on these frameworks, the team developed assessments that asked students, for example, to write justifications for the tools and procedures they intended to use for a particular purpose; rate their teammates’ ability to listen, appreciate different points of view, or reach a consensus; or generate a list of questions they would ask a client to better understand his or her needs. They used what Yarnall described as “coarse, three-level rubrics” to make the scoring easy to implement with sometimes-reluctant faculty, and have generally averaged 79 percent or above in inter-rater agreement.

Yarnall closed with some suggestions for how their experience might be useful for a K-12 context. She noted the process encouraged thinking about how students might apply particular knowledge and skills, and

5 See Mislevy and Risconscente (2006) for an explanation of evidence-centered design.

how one might distinguish between high- and low-quality applications. Specifically, the developers were guided to consider what it would look like for a student to use the knowledge or skills successfully—what qualities would stand out and what sorts of products or knowledge would demonstrate a particular level of understanding or awareness.

Assessing Medical Students’ Interpersonal Skills 6

Filip Lievens described a project conducted at Ghent University in Belgium, in which he and colleagues developed a measure of interpersonal skills in a high-stakes context: medical school admissions. The project began with a request from the Belgian government, in 1997, for a measure of these skills that could be used not only to measure the current capacities of physicians, but also to predict the capacities of candidates and thus be useful for selection. Lievens noted the challenge was compounded by the fact the government was motivated by some negative publicity about the selection process for medical school.

One logical approach would have been to use personality testing, often conducted through in-person interviews, but that would have been very difficult to implement with the large numbers of candidates involved, Lievens explained. A paper on another selection procedure, called “low-fidelity simulation” (Motowidlo et al., 1990), suggested an alternative. This approach is also known as a situational judgment test, mentioned above, in which candidates select from a set of possible responses to a situation that is described in writing or presented using video. It is based on the proposition that procedural knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of possible courses of action can be measured, and that the results would be predictive of later behaviors, even if the instrument does not measure the complex facets that go into such choices. A sample item from the Belgian assessment, including a transcription of the scenario and the possible responses, is shown in Box 3-3 . In the early stages of the project, the team used videotaped scenarios, but more recently they have experimented with presenting them through other means, including in written format.

Lievens noted a few differences between medical education in Belgium and the United States that influenced decisions about the assessment. In Belgium, prospective doctors must pass an admissions exam at age 18 to be accepted for medical school, which begins at the level that for Americans is the less structured 4-year undergraduate program. The government-run exam is given twice a year to approximately 4,000 stu-

6 Lievens’ presentation is available at http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Lievens.pdf [August 2011].

BOX 3-3 Sample Item from the Situational Judgment Test Used for Admissions to Medical School in Belgium

Patient: So, this physiotherapy is really going to help me?

Physician: Absolutely, even though the first days it might still be painful.

Patient: Yes, I suppose it will take a while before it starts working.

Physician: That is why I am going to prescribe a painkiller. You should take three painkillers per day.

Patient: Do I really have to take them? I have already tried a few things. First, they didn’t help me. And second, I’m actually opposed to taking any medication. I’d rather not take them. They are not good for my health.

What is the best way for you (as a physician) to react to this patient’s refusal to take the prescribed medication?

a. Ask her if she knows something else to relieve the pain.

b. Give her the scientific evidence as to why painkillers will help.

c. Agree not to take them now but also stress the importance of the physiotherapy.

d. Tell her that, in her own interest, she will have to start changing her attitude.

SOURCE: Louise Yarnall’s presentation. Used with permission.

dents in total, and it has a 30 percent pass rate. Once accepted for medical school, students may choose the university at which they will study—the school must accept all of the students who select it.

The assessment’s other components include 40 items covering knowledge of chemistry, physics, mathematics, and biology and 50 items covering general cognitive ability (verbal, numerical, and figural reasoning). The two interpersonal skills addressed—in 30 items—are building and maintaining relationships and exchanging information.

Lievens described several challenges in the development of the interpersonal component. First, it was not possible to pilot test any items because of a policy that students could not be asked to complete items that did not count toward their scores. In response to both fast-growing numbers of candidates as well as technical glitches with video presentations, the developers decided to present all of the prompts in a paper-and-pencil format. A more serious problem was feedback they received ques-

tioning whether each of the test questions had only one correct answer. To address this, the developers introduced a system for determining correct answers through consensus among a group of experts.

Because of the high stakes for this test, they have also encountered problems with maintaining the security of the test items. For instance, Lievens reported that items have appeared for sale on eBay, and they have had problems with students who took the test multiple times simply to learn the content. Developing alternate test forms was one strategy for addressing this problem.

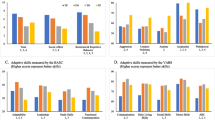

Lievens and his colleagues have conducted a study of the predictive validity of the test in which they collected data on four cohorts of students (a total of 4,538) who took the test and entered medical school (Lievens and Sackett, 2011). They examined GPA and internship performance data for 519 students in the initial group who completed the 7 years required for the full medical curriculum as well as job performance data for 104 students who later became physicians. As might be expected, Lievens observed, the cognitive component of the test was a strong predictor, particularly for the first years of the 7-year course, whereas the interpersonal portion was not useful for predicting GPA (see Figure 3-2 ). However, Figure 3-3 shows this component of the test was much better at predicting the students’ later performance in internships and in their first 9 years as practicing physicians.

FIGURE 3-2 Correlations between cognitive and interpersonal components (situational judgment test, or SJT) of the medical school admission test and medical school GPA.

SOURCE: Filip Lievens’ presentation. Used with permission.

FIGURE 3-3 Correlations between the cognitive and interpersonal components (situational judgment test, or SJT) of the medical school admission test and internship/job performance.

Lievens also reported the results of a study of the comparability of alternate forms of the test. The researchers compared results for three approaches to developing alternate forms. The approaches differed in the extent to which the characteristics of the situation presented in the items were held constant across the forms. The correlations between scores on the alternate forms ranged from .34 to .68, with the higher correlation occurring for the approach that maintained the most similarities in the characteristics of the items across the forms. The exact details of this study are too complex to present here, and the reader is referred to the full report (Lievens and Sackett, 2007) for a more complete description.

Lievens summarized a few points he has observed about the addition of the interpersonal skills component to the admissions test:

- While cognitive assessments are better at predicting GPA, the assessments of interpersonal skills were superior at predicting performance in internships and on the job. 7

- Applicants respond favorably to the interpersonal component of the test—Lievens did not claim this component is the reason but noted a sharp increase in the test-taking population.

7 Lievens mentioned but did not show data indicating (1) that the predictive validity of the interpersonal items for later performance was actually greater than the predictive validity of the cognitive items for GPA, and (2) that women perform slightly better than men on the interpersonal items.

- Success rates for admitted students have also improved. The percentage of students who successfully passed the requirements for the first academic year increased from 30 percent, prior to having the exam in place, to 80 percent after the exam was installed. While not making a causal claim, Lievens noted that the increased pass rate may be due to the fact that universities have also changed their curricula to place more emphasis on interpersonal skills, especially in the first year.

Assessment Centers 8

Lynn Gracin Collins began by explaining what an assessment center is. She noted the International Congress on Assessment Center Methods describes an assessment center as follows 9 :

a standardized evaluation of behavior based on multiple inputs. Several trained observers and techniques are used. Judgments about behavior are made, in major part, from specifically developed assessment simulations. These judgments are pooled in a meeting among the assessors or by a statistical integration process. In an integration discussion, comprehensive accounts of behavior—and often ratings of it—are pooled. The discussion results in evaluations of the assessees’ performance on the dimensions or other variables that the assessment center is designed to measure.

She emphasized that key aspects of an assessment center are that they are standardized, based on multiple types of input, involve trained observers, and use simulations. Assessment centers had their first industrial application in the United States about 50 years ago at AT&T. Collins said they are widely favored within the business community because, while they have guidelines to ensure they are carried out appropriately, they are also flexible enough to accommodate a variety of purposes. Assessment centers have the potential to provide a wealth of information about how someone performs a task. An important difference with other approaches is that the focus is not on “what would you do” or “what did you do”; instead, the approach involves watching someone actually perform the tasks. They are commonly used for the purpose of (1) selection and promotion, (2) identification of training and development needs, and (3) skill enhancement through simulations.

Collins said participants and management see them as a realistic job

8 Collins’ presentation is available at http://www7.national-academies.org/bota/21st_Century_Workshop_Collins.pdf [August 2011].

9 See http://www.assessmentcenters.org/articles/whatisassess1.asp [July 2011].

preview, and when used in a selection context, prospective employees actually experience what the job would entail. In that regard, Collins commented it is not uncommon for candidates—during the assessment—to “fold up their materials and say if this is what the job is, I don’t want it.” Thus, the tasks themselves can be instructive, useful for experiential learning, and an important selection device.

Some examples of the skills assessed include the following:

- Interpersonal : communication, influencing others, learning from interactions, leadership, teamwork, fostering relationships, conflict management

- Cognitive : problem solving, decision making, innovation, creativity, planning and organizing

- Intrapersonal : adaptability, drive, tolerance for stress, motivation, conscientiousness

To provide a sense of the steps involved in developing assessment center tasks, Collins laid out the general plan for a recent assessment they developed called the Technology Enhanced Assessment Center (TEAC). The steps are shown in Box 3-4 .

BOX 3-4 Steps involved in Developing the Technology Enhanced Assessment Center

SOURCE: Adapted from presentation by Lynn Gracin Collins. Used with permission.

Assessment centers make use of a variety of types of tasks to simulate the actual work environment. One that Collins described is called an “inbox exercise,” which consists of a virtual desktop showing received e-mail messages (some of which are marked “high priority”), voice messages, and a calendar that includes some appointments for that day. The candidate is observed and tracked as he or she proceeds to deal with the tasks presented through the inbox. The scheduled appointments on the calendar are used for conducting role-playing tasks in which the candidate has to participate in a simulated work interaction. This may involve a phone call, and the assessor/observer plays the role of the person being called. With the scheduled role-plays, the candidate may receive some information about the nature of the appointment in advance so that he or she can prepare for the appointment. There are typically some unscheduled role-playing tasks as well, in order to observe the candidate’s on-the-spot performance. In some instances, the candidate may also be expected to make a presentation. Assessors observe every activity the candidate performs.

Everything the candidate does at the virtual desktop is visible to the assessor(s) in real time, although in a “behind the scenes” manner that is blind to the candidate. The assessor can follow everything the candidate does, including what they do with every message in the inbox, any responses they make, and any entries they make on the calendar.

Following the inbox exercise, all of the observers/assessors complete evaluation forms. The forms are shared, and the ratings are discussed during a debriefing session at which the assessors come to consensus about the candidate. Time is also reserved to provide feedback to the candidate and to identify areas of strengths and weaknesses.

Collins reported that a good deal of information has been collected about the psychometric qualities of assessment centers. She characterized their reliabilities as adequate, with test-retest reliability coefficients in the .70 range. She said a wide range of inter-rater reliabilities have been reported, generally ranging from .50 to .94. The higher inter-rater reliabilities are associated with assessments in which the assessors/raters are well trained and have access to training materials that clearly explain the exercises, the constructs, and the scoring guidelines. Providing behavioral summary scales, which describe the actual behaviors associated with each score level, also help the assessors more accurately interpret the scoring guide.

She also noted considerable information is available about the validity of assessment centers. The most popular validation strategy is to examine evidence of content validity, which means the exercises actually measure the skills and competencies that they are intended to measure. A few studies have examined evidence of criterion-related validity, looking at the relationship between performance on the assessment center exer-

cises and job performance. She reported validities of .41 to .48 for a recent study conducted by her firm (SH&A/Fenestra, 2007) and .43 for a study by Byham (2010). Her review of the research indicates that assessment center results show incremental validity over personality tests, cognitive tests, and interviews.

One advantage of assessment center methods is they appear not to have adverse impact on minority groups. Collins said research documents that they tend to be unbiased in predictions of job performance. Further, they are viewed by participants as being fairer than other forms of assessment, and they have received positive support from the courts and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

Assessment centers can be expensive and time intensive, which is one of the challenges associated with using them. An assessment center in a traditional paradigm (as opposed to a high-tech paradigm) can cost between $2,500 and $10,000 per person. The features that affect cost are the number of assessors, the number of exercises, the length of the assessment, the type of report, and the type of feedback process. They can be logistically difficult to coordinate, depending on whether they use a traditional paradigm in which people need to be brought to a single location as opposed to a technology paradigm where much can be handled remotely and virtually. The typical assessment at a center lasts a full day, which means they are resource intensive and can be difficult to scale up to accommodate a large number of test takers.

This page intentionally left blank.

The routine jobs of yesterday are being replaced by technology and/or shipped off-shore. In their place, job categories that require knowledge management, abstract reasoning, and personal services seem to be growing. The modern workplace requires workers to have broad cognitive and affective skills. Often referred to as "21st century skills," these skills include being able to solve complex problems, to think critically about tasks, to effectively communicate with people from a variety of different cultures and using a variety of different techniques, to work in collaboration with others, to adapt to rapidly changing environments and conditions for performing tasks, to effectively manage one's work, and to acquire new skills and information on one's own.

The National Research Council (NRC) has convened two prior workshops on the topic of 21st century skills. The first, held in 2007, was designed to examine research on the skills required for the 21st century workplace and the extent to which they are meaningfully different from earlier eras and require corresponding changes in educational experiences. The second workshop, held in 2009, was designed to explore demand for these types of skills, consider intersections between science education reform goals and 21st century skills, examine models of high-quality science instruction that may develop the skills, and consider science teacher readiness for 21st century skills. The third workshop was intended to delve more deeply into the topic of assessment. The goal for this workshop was to capitalize on the prior efforts and explore strategies for assessing the five skills identified earlier. The Committee on the Assessment of 21st Century Skills was asked to organize a workshop that reviewed the assessments and related research for each of the five skills identified at the previous workshops, with special attention to recent developments in technology-enabled assessment of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. In designing the workshop, the committee collapsed the five skills into three broad clusters as shown below:

- Cognitive skills: nonroutine problem solving, critical thinking, systems thinking

- Interpersonal skills: complex communication, social skills, team-work, cultural sensitivity, dealing with diversity

- Intrapersonal skills: self-management, time management, self-development, self-regulation, adaptability, executive functioning

Assessing 21st Century Skills provides an integrated summary of the presentations and discussions from both parts of the third workshop.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

National Research Council (US) Committee on the Assessment of 21st Century Skills. Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011.

Assessing 21st Century Skills: Summary of a Workshop.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

3 Assessing Interpersonal Skills

The second cluster of skills—broadly termed interpersonal skills—are those required for relating to other people. These sorts of skills have long been recognized as important for success in school and the workplace, said Stephen Fiore, professor at the University of Central Florida, who presented findings from a paper about these skills and how they might be assessed (Salas, Bedwell, and Fiore, 2011). 1 Advice offered by Dale Carnegie in the 1930s to those who wanted to “win friends and influence people,” for example, included the following: be a good listener; don’t criticize, condemn, or complain; and try to see things from the other person’s point of view. These are the same sorts of skills found on lists of 21st century skills today. For example, the Partnership for 21st Century Skills includes numerous interpersonal capacities, such as working creatively with others, communicating clearly, and collaborating with others, among the skills students should learn as they progress from preschool through postsecondary study (see Box 3-1 for the definitions of the relevant skills in the organization’s P-21 Framework).

Interpersonal Capacities in the Partnership for 21st Century Skills Framework. Develop, implement, and communicate new ideas to others effectively Be open and responsive to new and diverse perspectives; incorporate group input and feedback into the work (more...)

It seems clear that these are important skills, yet definitive labels and definitions for the interpersonal skills important for success in schooling and work remain elusive: They have been called social or people skills, social competencies, soft skills, social self-efficacy, and social intelligence, Fiore said (see, e.g., Ferris, Witt, and Hochwarter, 2001 ; Hochwarter et al., 2006 ; Klein et al., 2006 ; Riggio, 1986 ; Schneider, Ackerman, and Kanfer, 1996 ; Sherer et al., 1982 ; Sternberg, 1985 ; Thorndike, 1920 ). The previous National Research Council (NRC) workshop report that offered a preliminary definition of 21st century skills described one broad category of interpersonal skills ( National Research Council, 2010 , p. 3):

- Complex communication/social skills: Skills in processing and interpreting both verbal and nonverbal information from others in order to respond appropriately. A skilled communicator is able to select key pieces of a complex idea to express in words, sounds, and images, in order to build shared understanding ( Levy and Murnane, 2004 ). Skilled communicators negotiate positive outcomes with customers, subordinates, and superiors through social perceptiveness, persuasion, negotiation, instructing, and service orientation ( Peterson et al., 1999 ).

These and other available definitions are not necessarily at odds, but in Fiore’s view, the lack of a single, clear definition reflects a lack of theoretical clarity about what they are, which in turn has hampered progress toward developing assessments of them. Nevertheless, appreciation for the importance of these skills—not just in business settings, but in scientific and technical collaboration, and in both K-12 and postsecondary education settings—has been growing. Researchers have documented benefits these skills confer, Fiore noted. For example, Goleman (1998) found they were twice as important to job performance as general cognitive ability. Sonnentag and Lange (2002) found understanding of cooperation strategies related to higher performance among engineering and software development teams, and Nash and colleagues (2003) showed that collaboration skills were key to successful interdisciplinary research among scientists.

- WHAT ARE INTERPERSONAL SKILLS?

The multiplicity of names for interpersonal skills and ways of conceiving of them reflects the fact that these skills have attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive components, Fiore explained. It is useful to consider 21st century skills in basic categories (e.g., cognitive, interpersonal, and intrapersonal), but it is still true that interpersonal skills draw on many capacities, such as knowledge of social customs and the capacity to solve problems associated with social expectations and interactions. Successful interpersonal behavior involves a continuous correction of social performance based on the reactions of others, and, as Richard Murnane had noted earlier, these are cognitively complex tasks. They also require self-regulation and other capacities that fall into the intrapersonal category (discussed in Chapter 4 ). Interpersonal skills could also be described as a form of “social intelligence,” specifically social perception and social cognition that involve processes such as attention and decoding. Accurate assessment, Fiore explained, may need to address these various facets separately.

The research on interpersonal skills has covered these facets, as researchers who attempted to synthesize it have shown. Fiore described the findings of a study ( Klein, DeRouin, and Salas, 2006 ) that presented a taxonomy of interpersonal skills based on a comprehensive review of the literature. The authors found a variety of ways of measuring and categorizing such skills, as well as ways to link them both to outcomes and to personality traits and other factors that affect them. They concluded that interpersonal effectiveness requires various sorts of competence that derive from experience, instinct, and learning about specific social contexts. They put forward their own definition of interpersonal skills as “goal-directed behaviors, including communication and relationship-building competencies, employed in interpersonal interaction episodes characterized by complex perceptual and cognitive processes, dynamic verbal and non verbal interaction exchanges, diverse roles, motivations, and expectancies” (p. 81).

They also developed a model of interpersonal performance, shown in Figure 3-1 , that illustrates the interactions among the influences, such as personality traits, previous life experiences, and the characteristics of the situation; the basic communication and relationship-building skills the individual uses in the situation; and outcomes for the individual, the group, and the organization. To flesh out this model, the researchers distilled sets of skills for each area, as shown in Table 3-1 .

Model of interpersonal performance. NOTE: Big Five personality traits = openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism; EI = emotional intelligence; IPS = interpersonal skills. SOURCE: Stephen Fiore’s presentation. Klein, (more...)

Taxonomy of Interpersonal Skills.

Fiore explained that because these frameworks focus on behaviors intended to attain particular social goals and draw on both attitudes and cognitive processes, they provide an avenue for exploring what goes into the development of effective interpersonal skills in an individual. They also allow for measurement of specific actions in a way that could be used in selection decisions, performance appraisals, or training. More specifically, Figure 3-1 sets up a way of thinking about these skills in the contexts in which they are used. The implication for assessment is that one would need to conduct the measurement in a suitable, realistic context in order to be able to examine the attitudes, cognitive processes, and behaviors that constitute social skills.

- ASSESSMENT APPROACHES AND ISSUES

One way to assess these skills, Fiore explained, is to look separately at the different components (attitudinal, behavioral, and cognitive). For example, as the model in Figure 3-1 indicates, previous life experiences, such as the opportunities an individual has had to engage in successful and unsuccessful social interactions, can be assessed through reports (e.g., personal statements from applicants or letters of recommendation from prior employers). If such narratives are written in response to specific questions about types of interactions, they may provide indications of the degree to which an applicant has particular skills. However, it is likely to be difficult to distinguish clearly between specific social skills and personality traits, knowledge, and cognitive processes. Moreover, Fiore added, such narratives report on past experience and may not accurately portray how one would behave or respond in future experiences.

The research on teamwork (or collaboration)—a much narrower concept than interpersonal skills—has used questionnaires that ask people to rate themselves and also ask for peer ratings of others on dimensions such as communication, leadership, and self-management. For example, Kantrowitz (2005) collected self-report data on two scales: performance standards for various behaviors, and comparison to others in the subjects’ working groups. Loughry, Ohland, and Moore (2007) asked members of work teams in science and technical contexts to rate one another on five general categories: contribution to the team’s work; interaction with teammates; contribution to keeping the team on track; expectations for quality; and possession of relevant knowledge, skills, and abilities.

Another approach, Fiore noted, is to use situational judgment tests (SJTs), which are multiple-choice assessments of possible reactions to hypothetical teamwork situations to assess capacities for conflict resolution, communication, and coordination, as Stevens and Campion (1999) have done. The researchers were able to demonstrate relationships between these results and both peers’ and supervisors’ ratings and to ratings of job performance. They were also highly correlated to employee aptitude test results.

Yet another approach is direct observation of team interactions. By observing directly, researchers can avoid the potential lack of reliability inherent in self- and peer reports, and can also observe the circumstances in which behaviors occur. For example, Taggar and Brown (2001) developed a set of scales related to conflict resolution, collaborative problem solving, and communication on which people could be rated.

Though each of these approaches involve ways of distinguishing specific aspects of behavior, it is still true, Fiore observed, that there is overlap among the constructs—skills or characteristics—to be measured. In his view, it is worth asking whether it is useful to be “reductionist” in parsing these skills. Perhaps more useful, he suggested, might be to look holistically at the interactions among the facets that contribute to these skills, though means of assessing in that way have yet to be determined. He enumerated some of the key challenges in assessing interpersonal skills.

The first concerns the precision, or degree of granularity, with which interpersonal expertise can be measured. Cognitive scientists have provided models of the progression from novice to expert in more concrete skill areas, he noted. In K-12 education contexts, assessment developers have looked for ways to delineate expectations for particular stages that students typically go through as their knowledge and understanding grow more sophisticated. Hoffman (1998) has suggested the value of a similar continuum for interpersonal skills. Inspired by the craft guilds common in Europe during the Middle Ages, Hoffman proposed that assessment developers use the guidelines for novices, journeymen, and master craftsmen, for example, as the basis for operational definitions of developing social expertise. If such a continuum were developed, Fiore noted, it should make it possible to empirically examine questions about whether adults can develop and improve in response to training or other interventions.

Another issue is the importance of the context in which assessments of interpersonal skills are administered. By definition, these skills entail some sort of interaction with other people, but much current testing is done in an individualized way that makes it difficult to standardize. Sophisticated technology, such as computer simulations, or even simpler technology can allow for assessment of people’s interactions in a standardized scenario. For example, Smith-Jentsch and colleagues (1996) developed a simulation of an emergency room waiting room, in which test takers interacted with a video of actors following a script, while others have developed computer avatars that can interact in the context of scripted events. When well executed, Fiore explained, such simulations may be able to elicit emotional responses, allowing for assessment of people’s self-regulatory capacities and other so-called soft skills.

Workshop participants noted the complexity of trying to take the context into account in assessment. For example, one noted both that behaviors may make sense only in light of previous experiences in a particular environment, and that individuals may display very different social skills in one setting (perhaps one in which they are very comfortable) than another (in which they are not comfortable). Another noted that the clinical psychology literature would likely offer productive insights on such issues.

The potential for technologically sophisticated assessments also highlights the evolving nature of social interaction and custom. Generations who have grown up interacting via cell phone, social networking, and tweeting may have different views of social norms than their parents had. For example, Fiore noted, a telephone call demands a response, and many younger people therefore view a call as more intrusive and potentially rude than a text message, which one can respond to at his or her convenience. The challenge for researchers is both to collect data on new kinds of interactions and to consider new ways to link the content of interactions to the mode of communication, in order to follow changes in what constitutes skill at interpersonal interaction. The existing definitions and taxonomies of interpersonal skills, he explained, were developed in the context of interactions that primarily occur face to face, but new technologies foster interactions that do not occur face to face or in a single time window.

In closing, Fiore returned to the conceptual slippage in the terms used to describe interpersonal skills. Noting that the etymological origins of both “cooperation” and “collaboration” point to a shared sense of working together, he explained that the word “coordination” has a different meaning, even though these three terms are often used as if they were synonymous. The word “coordination” captures instead the concepts of ordering and arranging—a key aspect of teamwork. These distinctions, he observed, are a useful reminder that examining the interactions among different facets of interpersonal skills requires clarity about each facet.

- ASSESSMENT EXAMPLES

The workshop included examples of four different types of assessments of interpersonal skills intended for different educational and selection purposes—an online portfolio assessment designed for high school students; an online assessment for community college students; a situational judgment test used to select students for medical school in Belgium; and a collection of assessment center approaches used for employee selection, promotion, and training purposes.

The first example was the portfolio assessment used by the Envision High School in Oakland, California, to assess critical thinking, collaboration, communication, and creativity. At Envision Schools, a project-based learning approach is used that emphasizes the development of deeper learning skills, integration of arts and technology into core subjects, and real-world experience in workplaces. 2 The focus of the curriculum is to prepare students for college, especially those who would be the first in their family to attend college. All students are required to assemble a portfolio in order to graduate. Bob Lenz, cofounder of Envision High School, discussed this online portfolio assessment.

The second example was an online, scenario-based assessment used for community college students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs. The focus of the program is on developing students’ social/communication skills as well as their technical skills. Louise Yarnall, senior research scientist with SRI, made this presentation.

Filip Lievens, professor of psychology at Ghent University in Belgium, described the third example, a situational judgment test designed to assess candidates’ skill in responding to health-related situations that require interpersonal skills. The test is used for high-stakes purposes.

The final presentation was made by Lynn Gracin Collins, chief scientist for SH&A/Fenestra, who discussed a variety of strategies for assessing interpersonal skills in employment settings. She focused on performance-based assessments, most of which involve role-playing activities.

Online Portfolio Assessment of High School Students 3

Bob Lenz described the experience of incorporating in the curriculum and assessing several key interpersonal skills in an urban high school environment. Envision Schools is a program created with corporate and foundation funding to serve disadvantaged high school students. The program consists of four high schools in the San Francisco Bay area that together serve 1,350 primarily low-income students. Sixty-five percent qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, and 70 percent are expected to be the first in their families to graduate from college. Most of the students, Lenz explained, enter the Envision schools at approximately a sixth-grade level in most areas. When they begin the Envision program, most have exceedingly negative feelings about school; as Lenz put it they “hate school and distrust adults.” The program’s mission is not only to address this sentiment about schools, but also to accelerate the students’ academic skills so that they can get into college and to develop the other skills they will need to succeed in life.

Lenz explained that tracking students’ progress after they graduate is an important tool for shaping the school’s approach to instruction. The first classes graduated from the Envision schools 2 years ago. Lenz reported that all of their students meet the requirements to attend a 4-year college in California (as opposed to 37 percent of public high school students statewide), and 94 percent of their graduates enrolled in 2- or 4-year colleges after graduation. At the time of the presentation, most of these students (95 percent) had re-enrolled for the second year of college. Lenz believes the program’s focus on assessment, particularly of 21st century skills, has been key to this success.

The program emphasizes what they call the “three Rs”: rigor, relevance, and relationships. Project-based assignments, group activities, and workplace projects are all activities that incorporate learning of interpersonal skills such as leadership, Lenz explained. Students are also asked to assess themselves regularly. Researchers from the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning, and Equity (SCALE) assisted the Envision staff in developing a College Success Assessment System that is embedded in the curriculum. Students develop portfolios with which they can demonstrate their learning in academic content as well as 21st century skill areas. The students are engaged in three goals: mastery knowledge, application of knowledge, and metacognition.

The components of the portfolio, which is presented at the end of 12th grade, include

- A student-written introduction to the contents

- Examples of “mastery-level” student work (assessed and certified by teachers prior to the presentation)

- Reflective summaries of work completed in five core content areas

- An artifact of and a written reflection on the workplace learning project

- A 21st century skills assessment

Students are also expected to defend their portfolios, and faculty are given professional development to guide the students in this process. Eventually, Lenz explained, the entire portfolio will be archived online.

Lenz showed examples of several student portfolios to demonstrate the ways in which 21st century skills, including interpersonal ones, are woven into both the curriculum and the assessments. In his view, teaching skills such as leadership and collaboration, together with the academic content, and holding the students to high expectations that incorporate these sorts of skills, is the best way to prepare the students to succeed in college, where there may be fewer faculty supports.

STEM Workforce Training Assessments 4

Louise Yarnall turned the conversation to assessment in a community college setting, where the technicians critical to many STEM fields are trained. She noted the most common approach to training for these workers is to engage them in hands-on practice with the technologies they are likely to encounter. This approach builds knowledge of basic technical procedures, but she finds that it does little to develop higher-order cognitive skills or the social skills graduates need to thrive in the workplace.

Yarnall and a colleague have outlined three categories of primary skills that technology employers seek in new hires ( Yarnall and Ostrander, in press ):

Social-Technical

- Translating client needs into technical specifications

- Researching technical information to meet client needs

- Justifying or defending technical approach to client

- Reaching consensus on work team

- Polling work team to determine ideas

- Using tools, languages, and principles of domain

- Generating a product that meets specific technical criteria

- Interpreting problems using principles of domain

In her view, new strategies are needed to incorporate these skills into the community college curriculum. To build students’ technical skills and knowledge, she argued, faculty need to focus more on higher-order thinking and application of knowledge, to press students to demonstrate their competence, and to practice. Cooperative learning opportunities are key to developing social skills and knowledge. For the skills that are both social and technical, students need practice with reflection and feedback opportunities, modeling and scaffolding of desirable approaches, opportunities to see both correct and incorrect examples, and inquiry-based instructional practices.

She described a project she and colleagues, in collaboration with community college faculty, developed that was designed to incorporate this thinking, called the Scenario-Based Learning Project (see Box 3-2 ). This team developed eight workplace scenarios—workplace challenges that were complex enough to require a team response. The students are given a considerable amount of material with which to work. In order to succeed, they would need to figure out how to approach the problem, what they needed, and how to divide up the effort. Students are also asked to reflect on the results of the effort and make presentations about the solutions they have devised. The project begins with a letter from the workplace manager (the instructor plays this role and also provides feedback throughout the process) describing the problem and deliverables that need to be produced. For example, one task asked a team to produce a website for a bicycle club that would need multiple pages and links.

Sample Constructs, Evidence of Learning, and Assessment Task Features for Scenario-Based Learning Projects. Ability to document system requirements using a simplified use case format; ability to address user needs in specifying system requirements. Presented (more...)

Yarnall noted they encountered a lot of resistance to this approach. Community college students are free to drop a class if they do not like the instructor’s approach, and because many instructors are adjunct faculty, their positions are at risk if their classes are unpopular. Scenario-based learning can be risky, she explained, because it can be demanding, but at the same time students sometimes feel unsure that they are learning enough. Instructors also sometimes feel unprepared to manage the teams, give appropriate feedback, and track their students’ progress.