Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 28 February 2018

- Correction 16 March 2018

How to write a first-class paper

- Virginia Gewin 0

Virginia Gewin is a freelance writer in Portland, Oregon.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Manuscripts may have a rigidly defined structure, but there’s still room to tell a compelling story — one that clearly communicates the science and is a pleasure to read. Scientist-authors and editors debate the importance and meaning of creativity and offer tips on how to write a top paper.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 555 , 129-130 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-02404-4

Interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 16 March 2018 : This article should have made clear that Altmetric is part of Digital Science, a company owned by Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, which is also the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature. Nature Research Editing Services is also owned by Springer Nature.

Related Articles

How to network with the brightest minds in science

Career Feature 26 JUN 24

What it means to be a successful male academic

Career Column 26 JUN 24

Is science’s dominant funding model broken?

Editorial 26 JUN 24

‘It can feel like there’s no way out’ — political scientists face pushback on their work

News Feature 19 JUN 24

How climate change is hitting Europe: three graphics reveal health impacts

News 18 JUN 24

Twelve scientist-endorsed tips to get over writer’s block

Career Feature 13 JUN 24

PostDoc Researcher, Magnetic Recording Materials Group, National Institute for Materials Science

Starting date would be after January 2025, but it is negotiable.

Tsukuba, Japan (JP)

National Institute for Materials Science

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions

Tenure-Track/Tenured Faculty Positions in the fields of energy and resources.

Suzhou, Jiangsu, China

School of Sustainable Energy and Resources at Nanjing University

Postdoctoral Associate- Statistical Genetics

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Senior Research Associate (Single Cell/Transcriptomics Senior Bioinformatician)

Metabolic Research Laboratories at the Clinical School, University of Cambridge are recruiting 3 senior bioinformatician specialists to create a dynam

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire (GB)

University of Cambridge

Cancer Biology Postdoctoral Fellow

Tampa, Florida

Moffitt Cancer Center

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Welcome to the PLOS Writing Center

Your source for scientific writing & publishing essentials.

A collection of free, practical guides and hands-on resources for authors looking to improve their scientific publishing skillset.

ARTICLE-WRITING ESSENTIALS

Your title is the first thing anyone who reads your article is going to see, and for many it will be where they stop reading. Learn how to write a title that helps readers find your article, draws your audience in and sets the stage for your research!

The abstract is your chance to let your readers know what they can expect from your article. Learn how to write a clear, and concise abstract that will keep your audience reading.

A clear methods section impacts editorial evaluation and readers’ understanding, and is also the backbone of transparency and replicability. Learn what to include in your methods section, and how much detail is appropriate.

In many fields, a statistical analysis forms the heart of both the methods and results sections of a manuscript. Learn how to report statistical analyses, and what other context is important for publication success and future reproducibility.

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

Ensuring your manuscript is well-written makes it easier for editors, reviewers and readers to understand your work. Avoiding language errors can help accelerate review and minimize delays in the publication of your research.

The PLOS Writing Toolbox

Delivered to your inbox every two weeks, the Writing Toolbox features practical advice and tools you can use to prepare a research manuscript for submission success and build your scientific writing skillset.

Discover how to navigate the peer review and publishing process, beyond writing your article.

The path to publication can be unsettling when you’re unsure what’s happening with your paper. Learn about staple journal workflows to see the detailed steps required for ensuring a rigorous and ethical publication.

Reputable journals screen for ethics at submission—and inability to pass ethics checks is one of the most common reasons for rejection. Unfortunately, once a study has begun, it’s often too late to secure the requisite ethical reviews and clearances. Learn how to prepare for publication success by ensuring your study meets all ethical requirements before work begins.

From preregistration, to preprints, to publication—learn how and when to share your study.

How you store your data matters. Even after you publish your article, your data needs to be accessible and useable for the long term so that other researchers can continue building on your work. Good data management practices make your data discoverable and easy to use, promote a strong foundation for reproducibility and increase your likelihood of citations.

You’ve just spent months completing your study, writing up the results and submitting to your top-choice journal. Now the feedback is in and it’s time to revise. Set out a clear plan for your response to keep yourself on-track and ensure edits don’t fall through the cracks.

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher.

Are you actively preparing a submission for a PLOS journal? Select the relevant journal below for more detailed guidelines.

How to Write an Article

Share the lessons of the Writing Center in a live, interactive training.

Access tried-and-tested training modules, complete with slides and talking points, workshop activities, and more.

How to Write a Scientific Article

- First Online: 02 February 2019

Cite this chapter

- Lukas B. Moser 8 , 9 &

- Michael T. Hirschmann 8 , 9

2462 Accesses

This chapter aims to give guidance for young trainees aiming to publish their first scientific article. It is our purpose to guide you through the process of writing a scientific article in a case-based approach. After reading the chapter, the reader should have a readily available guide to use for writing such articles and enjoy the process of scientific writing. Case examples should further illustrate the common pitfalls of scientific writing. In addition, these should help the reader to develop an appreciation for discerning both good and bad scientific writing.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or Ebook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing Scientific Manuscripts

Why, When, Who, What, How, and Where for Trainees Writing Literature Review Articles

Writing a strong scientific paper in medicine and the biomedical sciences: a checklist and recommendations for early career researchers

Cals JW, Kotz D. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part II: title and abstract. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:585.

Article Google Scholar

Cals JW, Kotz D. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part III: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:702.

Cals JW, Kotz D. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VI: discussion. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1064.

Cals JW, Kotz D. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VIII: references. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1198.

Guller U, Oertli D. Sample size matters: a guide for surgeons. World J Surg. 2005;29:601–5.

Harris JD, Brand JC, Cote MP, Faucett SC, Dhawan A. Research pearls: the significance of statistics and perils of pooling. Part 1: clinical versus statistical significance. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1102–12.

Hassink G, Testa EA, Leumann A, Hugle T, Rasch H, Hirschmann MT. Intra- and inter-observer reliability of a new standardized diagnostic method using SPECT/CT in patients with osteochondral lesions of the ankle joint. BMC Med Imaging. 2016;16:67.

Kotz D, Cals JW. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers—part I: how to get started. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:397.

Kotz D, Cals JW. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part IV: methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:817.

Kotz D, Cals JW. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part V: results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:945.

Kotz D, Cals JW. Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part VII: tables and figures. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:1197.

Lacroix JR. A key to scientific research literature. Can Med Assoc J. 1971;104:1080.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Letchford A, Moat HS, Preis T. The advantage of short paper titles. R Soc Open Sci. 2015;2:150266.

Mathis DT, Hirschmann A, Falkowski AL, Kiekara T, Amsler F, Rasch H, et al. Increased bone tracer uptake in symptomatic patients with ACL graft insufficiency: a correlation of MRI and SPECT/CT findings. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(2):563–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-017-4588-5 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mathis DT, Kaelin R, Rasch H, Arnold MP, Hirschmann MT. Good clinical results but moderate osseointegration and defect filling of a cell-free multi-layered nano-composite scaffold for treatment of osteochondral lesions of the knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2018;26(4):1273–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-017-4638-z .

Peh WC, Ng KH. Basic structure and types of scientific papers. Singap Med J. 2008;49:522–5.

CAS Google Scholar

Rickham PP. Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br Med J. 1964;2:177.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Rohrig B, du Prel JB, Wachtlin D, Blettner M. Types of study in medical research: part 3 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:262–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Open Med. 2010;4:e60–8.

Vitse CL, Poland GA. Writing a scientific paper—a brief guide for new investigators. Vaccine. 2017;35:722–8.

Watson PF, Petrie A. Method agreement analysis: a review of correct methodology. Theriogenology. 2010;73:1167–79.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Liestal, Laufen), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Lukas B. Moser & Michael T. Hirschmann

University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michael T. Hirschmann .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UPMC Rooney Sports Complex, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Volker Musahl

Department of Orthopaedics, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden

Jón Karlsson

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, Kantonsspital Baselland (Bruderholz, Laufen und Liestal), Bruderholz, Switzerland

Michael T. Hirschmann

McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Olufemi R. Ayeni

Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, USA

Robert G. Marx

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, IL, USA

Jason L. Koh

Institute for Medical Science in Sports, Osaka Health Science University, Osaka, Japan

Norimasa Nakamura

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 ISAKOS

About this chapter

Moser, L.B., Hirschmann, M.T. (2019). How to Write a Scientific Article. In: Musahl, V., et al. Basic Methods Handbook for Clinical Orthopaedic Research. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_54

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-58254-1_54

Published : 02 February 2019

Publisher Name : Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-662-58253-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-662-58254-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Unfortunately we don't fully support your browser. If you have the option to, please upgrade to a newer version or use Mozilla Firefox , Microsoft Edge , Google Chrome , or Safari 14 or newer. If you are unable to, and need support, please send us your feedback .

We'd appreciate your feedback. Tell us what you think! opens in new tab/window

11 steps to structuring a science paper editors will take seriously

April 5, 2021 | 18 min read

By Angel Borja, PhD

Editor’s note: This 2014 post conveys the advice of a researcher sharing his experience and does not represent Elsevier’s policy. However, in response to your feedback, we worked with him to update this post so it reflects our practices. For example, since it was published, we have worked extensively with researchers to raise visibility of non-English language research – July 10, 2019

Update: In response to your feedback, we have reinstated the original text so you can see how it was revised. – July 11, 2019

How to prepare a manuscript for international journals — Part 2

In this monthly series, Dr. Angel Borja draws on his extensive background as an author, reviewer and editor to give advice on preparing the manuscript (author's view), the evaluation process (reviewer's view) and what there is to hate or love in a paper (editor's view).

This article is the second in the series. The first article was: "Six things to do before writing your manuscript."

When you organize your manuscript, the first thing to consider is that the order of sections will be very different than the order of items on you checklist.

An article begins with the Title, Abstract and Keywords.

The article text follows the IMRAD format opens in new tab/window , which responds to the questions below:

I ntroduction: What did you/others do? Why did you do it?

M ethods: How did you do it?

R esults: What did you find?

D iscussion: What does it all mean?

The main text is followed by the Conclusion, Acknowledgements, References and Supporting Materials.

While this is the published structure, however, we often use a different order when writing.

General strcuture of a research article. Watch a related tutorial on Researcher Academy opens in new tab/window .

Steps to organizing your manuscript

Prepare the figures and tables .

Write the Methods .

Write up the Results .

Write the Discussion . Finalize the Results and Discussion before writing the introduction. This is because, if the discussion is insufficient, how can you objectively demonstrate the scientific significance of your work in the introduction?

Write a clear Conclusion .

Write a compelling Introduction .

Write the Abstract .

Compose a concise and descriptive Title .

Select Keywords for indexing.

Write the Acknowledgements .

Write up the References .

Next, I'll review each step in more detail. But before you set out to write a paper, there are two important things you should do that will set the groundwork for the entire process.

The topic to be studied should be the first issue to be solved. Define your hypothesis and objectives (These will go in the Introduction.)

Review the literature related to the topic and select some papers (about 30) that can be cited in your paper (These will be listed in the References.)

Finally, keep in mind that each publisher has its own style guidelines and preferences, so always consult the publisher's Guide for Authors.

Step 1: Prepare the figures and tables

Remember that "a figure is worth a thousand words." Hence, illustrations, including figures and tables, are the most efficient way to present your results. Your data are the driving force of the paper, so your illustrations are critical!

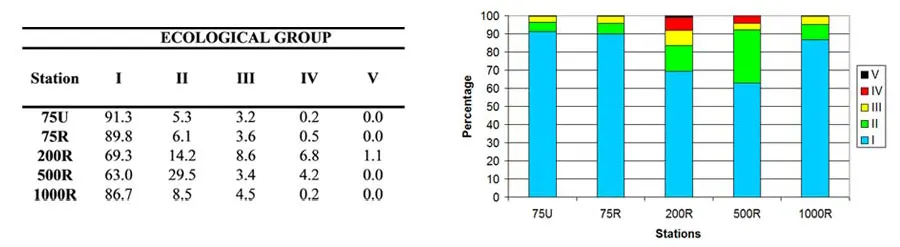

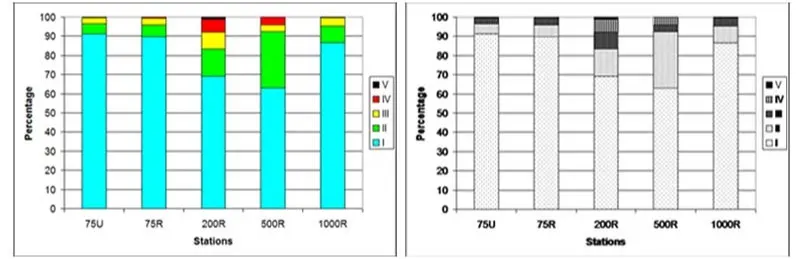

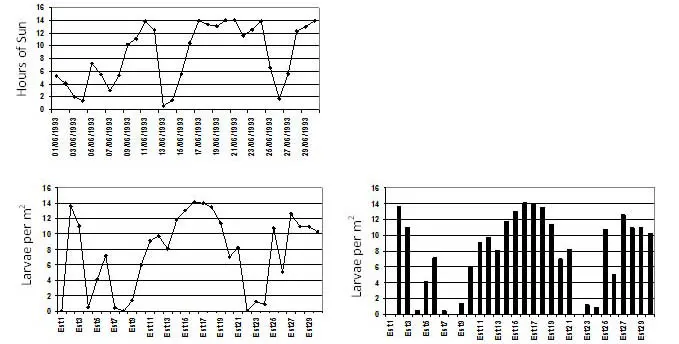

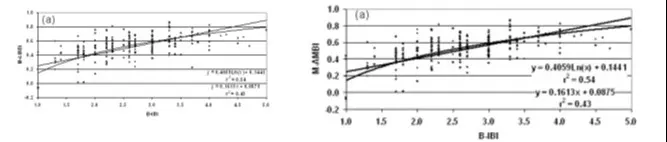

How do you decide between presenting your data as tables or figures? Generally, tables give the actual experimental results, while figures are often used for comparisons of experimental results with those of previous works, or with calculated/theoretical values (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An example of the same data presented as table or as figure. Depending on your objectives, you can show your data either as table (if you wish to stress numbers) or as figure (if you wish to compare gradients).

Whatever your choice is, no illustrations should duplicate the information described elsewhere in the manuscript.

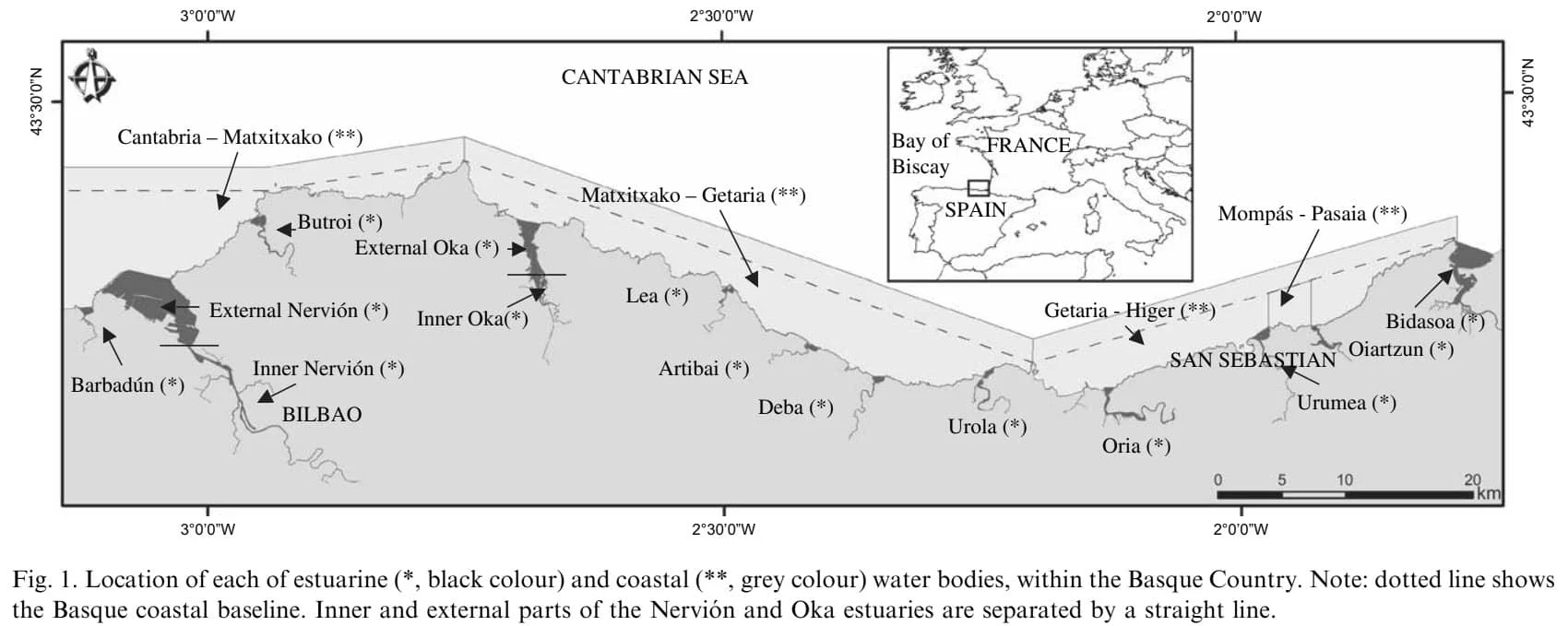

Another important factor: figure and table legends must be self-explanatory (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Figures must be self-explanatory.

When presenting your tables and figures, appearances count! To this end:

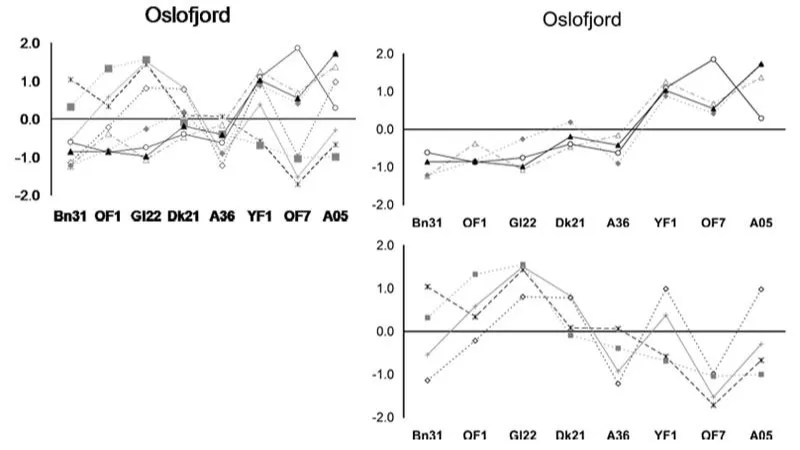

Avoid crowded plots (Figure 3), using only three or four data sets per figure; use well-selected scales.

Think about appropriate axis label size

Include clear symbols and data sets that are easy to distinguish.

Never include long boring tables (e.g., chemical compositions of emulsion systems or lists of species and abundances). You can include them as supplementary material.

Figure 3. Don't clutter your charts with too much data.

If you are using photographs, each must have a scale marker, or scale bar, of professional quality in one corner.

In photographs and figures, use color only when necessary when submitting to a print publication. If different line styles can clarify the meaning, never use colors or other thrilling effects or you will be charged with expensive fees. Of course, this does not apply to online journals. For many journals, you can submit duplicate figures: one in color for the online version of the journal and pdfs, and another in black and white for the hardcopy journal (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Using black and white can save money.

Another common problem is the misuse of lines and histograms. Lines joining data only can be used when presenting time series or consecutive samples data (e.g., in a transect from coast to offshore in Figure 5). However, when there is no connection between samples or there is not a gradient, you must use histograms (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Use the right kind of chart for your data.

Sometimes, fonts are too small for the journal. You must take this into account, or they may be illegible to readers (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Figures are not eye charts - make them large enough too read

Finally, you must pay attention to the use of decimals, lines, etc.

Step 2: Write the Methods

This section responds to the question of how the problem was studied. If your paper is proposing a new method, you need to include detailed information so a knowledgeable reader can reproduce the experiment.

However, do not repeat the details of established methods; use References and Supporting Materials to indicate the previously published procedures. Broad summaries or key references are sufficient.

Reviewers will criticize incomplete or incorrect methods descriptions and may recommend rejection, because this section is critical in the process of reproducing your investigation. In this way, all chemicals must be identified. Do not use proprietary, unidentifiable compounds.

To this end, it's important to use standard systems for numbers and nomenclature. For example:

For chemicals, use the conventions of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry opens in new tab/window and the official recommendations of the IUPAC–IUB Combined Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature opens in new tab/window .

For species, use accepted taxonomical nomenclature ( WoRMS: World Register of Marine Species opens in new tab/window , ERMS: European Register of Marine Species opens in new tab/window ), and write them always in italics.

For units of measurement, follow the International System of Units (SI).

Present proper control experiments and statistics used, again to make the experiment of investigation repeatable.

List the methods in the same order they will appear in the Results section, in the logical order in which you did the research:

Description of the site

Description of the surveys or experiments done, giving information on dates, etc.

Description of the laboratory methods, including separation or treatment of samples, analytical methods, following the order of waters, sediments and biomonitors. If you have worked with different biodiversity components start from the simplest (i.e. microbes) to the more complex (i.e. mammals)

Description of the statistical methods used (including confidence levels, etc.)

In this section, avoid adding comments, results, and discussion, which is a common error.

Length of the manuscript

Again, look at the journal's Guide for Authors, but an ideal length for a manuscript is 25 to 40 pages, double spaced, including essential data only. Here are some general guidelines:

Title: Short and informative

Abstract: 1 paragraph (<250 words)

Introduction: 1.5-2 pages

Methods: 2-3 pages

Results: 6-8 pages

Discussion: 4-6 pages

Conclusion: 1 paragraph

Figures: 6-8 (one per page)

Tables: 1-3 (one per page)

References: 20-50 papers (2-4 pages)

Step 3: Write up the Results

This section responds to the question "What have you found?" Hence, only representative results from your research should be presented. The results should be essential for discussion.

However, remember that most journals offer the possibility of adding Supporting Materials, so use them freely for data of secondary importance. In this way, do not attempt to "hide" data in the hope of saving it for a later paper. You may lose evidence to reinforce your conclusion. If data are too abundant, you can use those supplementary materials.

Use sub-headings to keep results of the same type together, which is easier to review and read. Number these sub-sections for the convenience of internal cross-referencing, but always taking into account the publisher's Guide for Authors.

For the data, decide on a logical order that tells a clear story and makes it and easy to understand. Generally, this will be in the same order as presented in the methods section.

An important issue is that you must not include references in this section; you are presenting your results, so you cannot refer to others here. If you refer to others, is because you are discussing your results, and this must be included in the Discussion section.

Statistical rules

Indicate the statistical tests used with all relevant parameters: e.g., mean and standard deviation (SD): 44% (±3); median and interpercentile range: 7 years (4.5 to 9.5 years).

Use mean and standard deviation to report normally distributed data.

Use median and interpercentile range to report skewed data.

For numbers, use two significant digits unless more precision is necessary (2.08, not 2.07856444).

Never use percentages for very small samples e.g., "one out of two" should not be replaced by 50%.

Step 4: Write the Discussion

Here you must respond to what the results mean. Probably it is the easiest section to write, but the hardest section to get right. This is because it is the most important section of your article. Here you get the chance to sell your data. Take into account that a huge numbers of manuscripts are rejected because the Discussion is weak.

You need to make the Discussion corresponding to the Results, but do not reiterate the results. Here you need to compare the published results by your colleagues with yours (using some of the references included in the Introduction). Never ignore work in disagreement with yours, in turn, you must confront it and convince the reader that you are correct or better.

Take into account the following tips:

Avoid statements that go beyond what the results can support.

Avoid unspecific expressions such as "higher temperature", "at a lower rate", "highly significant". Quantitative descriptions are always preferred (35ºC, 0.5%, p<0.001, respectively).

Avoid sudden introduction of new terms or ideas; you must present everything in the introduction, to be confronted with your results here.

Speculations on possible interpretations are allowed, but these should be rooted in fact, rather than imagination. To achieve good interpretations think about:

How do these results relate to the original question or objectives outlined in the Introduction section?

Do the data support your hypothesis?

Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported?

Discuss weaknesses and discrepancies. If your results were unexpected, try to explain why

Is there another way to interpret your results?

What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results?

Explain what is new without exaggerating

Revision of Results and Discussion is not just paper work. You may do further experiments, derivations, or simulations. Sometimes you cannot clarify your idea in words because some critical items have not been studied substantially.

Step 5: Write a clear Conclusion

This section shows how the work advances the field from the present state of knowledge. In some journals, it's a separate section; in others, it's the last paragraph of the Discussion section. Whatever the case, without a clear conclusion section, reviewers and readers will find it difficult to judge your work and whether it merits publication in the journal.

A common error in this section is repeating the abstract, or just listing experimental results. Trivial statements of your results are unacceptable in this section.

You should provide a clear scientific justification for your work in this section, and indicate uses and extensions if appropriate. Moreover, you can suggest future experiments and point out those that are underway.

You can propose present global and specific conclusions, in relation to the objectives included in the introduction

Step 6: Write a compelling Introduction

This is your opportunity to convince readers that you clearly know why your work is useful.

A good introduction should answer the following questions:

What is the problem to be solved?

Are there any existing solutions?

Which is the best?

What is its main limitation?

What do you hope to achieve?

Editors like to see that you have provided a perspective consistent with the nature of the journal. You need to introduce the main scientific publications on which your work is based, citing a couple of original and important works, including recent review articles.

However, editors hate improper citations of too many references irrelevant to the work, or inappropriate judgments on your own achievements. They will think you have no sense of purpose.

Here are some additional tips for the introduction:

Never use more words than necessary (be concise and to-the-point). Don't make this section into a history lesson. Long introductions put readers off.

We all know that you are keen to present your new data. But do not forget that you need to give the whole picture at first.

The introduction must be organized from the global to the particular point of view, guiding the readers to your objectives when writing this paper.

State the purpose of the paper and research strategy adopted to answer the question, but do not mix introduction with results, discussion and conclusion. Always keep them separate to ensure that the manuscript flows logically from one section to the next.

Hypothesis and objectives must be clearly remarked at the end of the introduction.

Expressions such as "novel," "first time," "first ever," and "paradigm-changing" are not preferred. Use them sparingly.

Step 7: Write the Abstract

The abstract tells prospective readers what you did and what the important findings in your research were. Together with the title, it's the advertisement of your article. Make it interesting and easily understood without reading the whole article. Avoid using jargon, uncommon abbreviations and references.

You must be accurate, using the words that convey the precise meaning of your research. The abstract provides a short description of the perspective and purpose of your paper. It gives key results but minimizes experimental details. It is very important to remind that the abstract offers a short description of the interpretation/conclusion in the last sentence.

A clear abstract will strongly influence whether or not your work is further considered.

However, the abstracts must be keep as brief as possible. Just check the 'Guide for authors' of the journal, but normally they have less than 250 words. Here's a good example on a short abstract opens in new tab/window .

In an abstract, the two whats are essential. Here's an example from an article I co-authored in Ecological Indicators opens in new tab/window :

What has been done? "In recent years, several benthic biotic indices have been proposed to be used as ecological indicators in estuarine and coastal waters. One such indicator, the AMBI (AZTI Marine Biotic Index), was designed to establish the ecological quality of European coasts. The AMBI has been used also for the determination of the ecological quality status within the context of the European Water Framework Directive. In this contribution, 38 different applications including six new case studies (hypoxia processes, sand extraction, oil platform impacts, engineering works, dredging and fish aquaculture) are presented."

What are the main findings? "The results show the response of the benthic communities to different disturbance sources in a simple way. Those communities act as ecological indicators of the 'health' of the system, indicating clearly the gradient associated with the disturbance."

Step 8: Compose a concise and descriptive title

The title must explain what the paper is broadly about. It is your first (and probably only) opportunity to attract the reader's attention. In this way, remember that the first readers are the Editor and the referees. Also, readers are the potential authors who will cite your article, so the first impression is powerful!

We are all flooded by publications, and readers don't have time to read all scientific production. They must be selective, and this selection often comes from the title.

Reviewers will check whether the title is specific and whether it reflects the content of the manuscript. Editors hate titles that make no sense or fail to represent the subject matter adequately. Hence, keep the title informative and concise (clear, descriptive, and not too long). You must avoid technical jargon and abbreviations, if possible. This is because you need to attract a readership as large as possible. Dedicate some time to think about the title and discuss it with your co-authors.

Here you can see some examples of original titles, and how they were changed after reviews and comments to them:

Original title: Preliminary observations on the effect of salinity on benthic community distribution within a estuarine system, in the North Sea

Revised title: Effect of salinity on benthic distribution within the Scheldt estuary (North Sea)

Comments: Long title distracts readers. Remove all redundancies such as "studies on," "the nature of," etc. Never use expressions such as "preliminary." Be precise.

Original title: Action of antibiotics on bacteria

Revised title: Inhibition of growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by streptomycin

Comments: Titles should be specific. Think about "how will I search for this piece of information" when you design the title.

Original title: Fabrication of carbon/CdS coaxial nanofibers displaying optical and electrical properties via electrospinning carbon

Revised title: Electrospinning of carbon/CdS coaxial nanofibers with optical and electrical properties

Comments: "English needs help. The title is nonsense. All materials have properties of all varieties. You could examine my hair for its electrical and optical properties! You MUST be specific. I haven't read the paper but I suspect there is something special about these properties, otherwise why would you be reporting them?" – the Editor-in-Chief.

Try to avoid this kind of response!

Step 9: Select keywords for indexing

Keywords are used for indexing your paper. They are the label of your manuscript. It is true that now they are less used by journals because you can search the whole text. However, when looking for keywords, avoid words with a broad meaning and words already included in the title.

Some journals require that the keywords are not those from the journal name, because it is implicit that the topic is that. For example, the journal Soil Biology & Biochemistry requires that the word "soil" not be selected as a keyword.

Only abbreviations firmly established in the field are eligible (e.g., TOC, CTD), avoiding those which are not broadly used (e.g., EBA, MMI).

Again, check the Guide for Authors and look at the number of keywords admitted, label, definitions, thesaurus, range, and other special requests.

Step 10: Write the Acknowledgements

Here, you can thank people who have contributed to the manuscript but not to the extent where that would justify authorship. For example, here you can include technical help and assistance with writing and proofreading. Probably, the most important thing is to thank your funding agency or the agency giving you a grant or fellowship.

In the case of European projects, do not forget to include the grant number or reference. Also, some institutes include the number of publications of the organization, e.g., "This is publication number 657 from AZTI-Tecnalia."

Step 11: Write up the References

Typically, there are more mistakes in the references than in any other part of the manuscript. It is one of the most annoying problems, and causes great headaches among editors. Now, it is easier since to avoid these problem, because there are many available tools.

In the text, you must cite all the scientific publications on which your work is based. But do not over-inflate the manuscript with too many references – it doesn't make a better manuscript! Avoid excessive self-citations and excessive citations of publications from the same region.

As I have mentioned, you will find the most authoritative information for each journal’s policy on citations when you consult the journal's Guide for Authors. In general, you should minimize personal communications, and be mindful as to how you include unpublished observations. These will be necessary for some disciplines, but consider whether they strengthen or weaken your paper. You might also consider articles published on research networks opens in new tab/window prior to publication, but consider balancing these citations with citations of peer-reviewed research. When citing research in languages other than English, be aware of the possibility that not everyone in the review process will speak the language of the cited paper and that it may be helpful to find a translation where possible.

You can use any software, such as EndNote opens in new tab/window or Mendeley opens in new tab/window , to format and include your references in the paper. Most journals have now the possibility to download small files with the format of the references, allowing you to change it automatically. Also, Elsevier's Your Paper Your Way program waves strict formatting requirements for the initial submission of a manuscript as long as it contains all the essential elements being presented here.

Make the reference list and the in-text citation conform strictly to the style given in the Guide for Authors. Remember that presentation of the references in the correct format is the responsibility of the author, not the editor. Checking the format is normally a large job for the editors. Make their work easier and they will appreciate the effort.

Finally, check the following:

Spelling of author names

Year of publications

Usages of "et al."

Punctuation

Whether all references are included

In my next article, I will give tips for writing the manuscript, authorship, and how to write a compelling cover letter. Stay tuned!

References and Acknowledgements

I have based this paper on the materials distributed to the attendees of many courses. It is inspired by many Guides for Authors of Elsevier journals. Some of this information is also featured in Elsevier's Publishing Connect tutorials opens in new tab/window . In addition, I have consulted several web pages: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/ opens in new tab/window , www.physics.ohio-state.edu/~wilkins/writing/index.html.

I want to acknowledge Dr. Christiane Barranguet opens in new tab/window , Executive Publisher of Aquatic Sciences at Elsevier, for her continuous support. And I would like to thank Dr. Alison Bert, Editor-in-Chief of Elsevier Connect; without her assistance, this series would have been impossible to complete.

Contributor

Angel Borja, PhD

WRITING A SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLE | Format for the paper | Edit your paper! | Useful books | FORMAT FOR THE PAPER Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. A standard format is used for these articles, in which the author presents the research in an orderly, logical manner. This doesn't necessarily reflect the order in which you did or thought about the work. This format is: | Title | Authors | Introduction | Materials and Methods | Results (with Tables and Figures ) | Discussion | Acknowledgments | Literature Cited | TITLE Make your title specific enough to describe the contents of the paper, but not so technical that only specialists will understand. The title should be appropriate for the intended audience. The title usually describes the subject matter of the article: Effect of Smoking on Academic Performance" Sometimes a title that summarizes the results is more effective: Students Who Smoke Get Lower Grades" AUTHORS 1. The person who did the work and wrote the paper is generally listed as the first author of a research paper. 2. For published articles, other people who made substantial contributions to the work are also listed as authors. Ask your mentor's permission before including his/her name as co-author. ABSTRACT 1. An abstract, or summary, is published together with a research article, giving the reader a "preview" of what's to come. Such abstracts may also be published separately in bibliographical sources, such as Biologic al Abstracts. They allow other scientists to quickly scan the large scientific literature, and decide which articles they want to read in depth. The abstract should be a little less technical than the article itself; you don't want to dissuade your potent ial audience from reading your paper. 2. Your abstract should be one paragraph, of 100-250 words, which summarizes the purpose, methods, results and conclusions of the paper. 3. It is not easy to include all this information in just a few words. Start by writing a summary that includes whatever you think is important, and then gradually prune it down to size by removing unnecessary words, while still retaini ng the necessary concepts. 3. Don't use abbreviations or citations in the abstract. It should be able to stand alone without any footnotes. INTRODUCTION What question did you ask in your experiment? Why is it interesting? The introduction summarizes the relevant literature so that the reader will understand why you were interested in the question you asked. One to fo ur paragraphs should be enough. End with a sentence explaining the specific question you asked in this experiment. MATERIALS AND METHODS 1. How did you answer this question? There should be enough information here to allow another scientist to repeat your experiment. Look at other papers that have been published in your field to get some idea of what is included in this section. 2. If you had a complicated protocol, it may helpful to include a diagram, table or flowchart to explain the methods you used. 3. Do not put results in this section. You may, however, include preliminary results that were used to design the main experiment that you are reporting on. ("In a preliminary study, I observed the owls for one week, and found that 73 % of their locomotor activity occurred during the night, and so I conducted all subsequent experiments between 11 pm and 6 am.") 4. Mention relevant ethical considerations. If you used human subjects, did they consent to participate. If you used animals, what measures did you take to minimize pain? RESULTS 1. This is where you present the results you've gotten. Use graphs and tables if appropriate, but also summarize your main findings in the text. Do NOT discuss the results or speculate as to why something happened; t hat goes in th e Discussion. 2. You don't necessarily have to include all the data you've gotten during the semester. This isn't a diary. 3. Use appropriate methods of showing data. Don't try to manipulate the data to make it look like you did more than you actually did. "The drug cured 1/3 of the infected mice, another 1/3 were not affected, and the third mouse got away." TABLES AND GRAPHS 1. If you present your data in a table or graph, include a title describing what's in the table ("Enzyme activity at various temperatures", not "My results".) For graphs, you should also label the x and y axes. 2. Don't use a table or graph just to be "fancy". If you can summarize the information in one sentence, then a table or graph is not necessary. DISCUSSION 1. Highlight the most significant results, but don't just repeat what you've written in the Results section. How do these results relate to the original question? Do the data support your hypothesis? Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported? If your results were unexpected, try to explain why. Is there another way to interpret your results? What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results? How do y our results fit into the big picture? 2. End with a one-sentence summary of your conclusion, emphasizing why it is relevant. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This section is optional. You can thank those who either helped with the experiments, or made other important contributions, such as discussing the protocol, commenting on the manuscript, or buying you pizza. REFERENCES (LITERATURE CITED) There are several possible ways to organize this section. Here is one commonly used way: 1. In the text, cite the literature in the appropriate places: Scarlet (1990) thought that the gene was present only in yeast, but it has since been identified in the platypus (Indigo and Mauve, 1994) and wombat (Magenta, et al., 1995). 2. In the References section list citations in alphabetical order. Indigo, A. C., and Mauve, B. E. 1994. Queer place for qwerty: gene isolation from the platypus. Science 275, 1213-1214. Magenta, S. T., Sepia, X., and Turquoise, U. 1995. Wombat genetics. In: Widiculous Wombats, Violet, Q., ed. New York: Columbia University Press. p 123-145. Scarlet, S.L. 1990. Isolation of qwerty gene from S. cerevisae. Journal of Unusual Results 36, 26-31. EDIT YOUR PAPER!!! "In my writing, I average about ten pages a day. Unfortunately, they're all the same page." Michael Alley, The Craft of Scientific Writing A major part of any writing assignment consists of re-writing. Write accurately Scientific writing must be accurate. Although writing instructors may tell you not to use the same word twice in a sentence, it's okay for scientific writing, which must be accurate. (A student who tried not to repeat the word "hamster" produced this confusing sentence: "When I put the hamster in a cage with the other animals, the little mammals began to play.") Make sure you say what you mean. Instead of: The rats were injected with the drug. (sounds like a syringe was filled with drug and ground-up rats and both were injected together) Write: I injected the drug into the rat.

- Be careful with commonly confused words:

Temperature has an effect on the reaction. Temperature affects the reaction.

I used solutions in various concentrations. (The solutions were 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 15 mg/ml) I used solutions in varying concentrations. (The concentrations I used changed; sometimes they were 5 mg/ml, other times they were 15 mg/ml.)

Less food (can't count numbers of food) Fewer animals (can count numbers of animals)

A large amount of food (can't count them) A large number of animals (can count them)

The erythrocytes, which are in the blood, contain hemoglobin. The erythrocytes that are in the blood contain hemoglobin. (Wrong. This sentence implies that there are erythrocytes elsewhere that don't contain hemoglobin.)

Write clearly

1. Write at a level that's appropriate for your audience.

"Like a pigeon, something to admire as long as it isn't over your head." Anonymous

2. Use the active voice. It's clearer and more concise than the passive voice.

Instead of: An increased appetite was manifested by the rats and an increase in body weight was measured. Write: The rats ate more and gained weight.

3. Use the first person.

Instead of: It is thought Write: I think

Instead of: The samples were analyzed Write: I analyzed the samples

4. Avoid dangling participles.

"After incubating at 30 degrees C, we examined the petri plates." (You must've been pretty warm in there.)

Write succinctly

1. Use verbs instead of abstract nouns

Instead of: take into consideration Write: consider

2. Use strong verbs instead of "to be"

Instead of: The enzyme was found to be the active agent in catalyzing... Write: The enzyme catalyzed...

3. Use short words.

|

Instead of: Write: possess have sufficient enough utilize use demonstrate show assistance help terminate end

4. Use concise terms.

Instead of: Write: prior to before due to the fact that because in a considerable number of cases often the vast majority of most during the time that when in close proximity to near it has long been known that I'm too lazy to look up the reference

5. Use short sentences. A sentence made of more than 40 words should probably be rewritten as two sentences.

"The conjunction 'and' commonly serves to indicate that the writer's mind still functions even when no signs of the phenomenon are noticeable." Rudolf Virchow, 1928

Check your grammar, spelling and punctuation

1. Use a spellchecker, but be aware that they don't catch all mistakes.

"When we consider the animal as a hole,..." Student's paper

2. Your spellchecker may not recognize scientific terms. For the correct spelling, try Biotech's Life Science Dictionary or one of the technical dictionaries on the reference shelf in the Biology or Health Sciences libraries.

3. Don't, use, unnecessary, commas.

4. Proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

USEFUL BOOKS

Victoria E. McMillan, Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences , Bedford Books, Boston, 1997 The best. On sale for about $18 at Labyrinth Books, 112th Street. On reserve in Biology Library

Jan A. Pechenik, A Short Guide to Writing About Biology , Boston: Little, Brown, 1987

Harrison W. Ambrose, III & Katharine Peckham Ambrose, A Handbook of Biological Investigation , 4th edition, Hunter Textbooks Inc, Winston-Salem, 1987 Particularly useful if you need to use statistics to analyze your data. Copy on Reference shelf in Biology Library.

Robert S. Day, How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , 4th edition, Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1994. Earlier editions also good. A bit more advanced, intended for those writing papers for publication. Fun to read. Several copies available in Columbia libraries.

William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White, The Elements of Style , 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, 1987. Several copies available in Columbia libraries. Strunk's first edition is available on-line.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Writing a scientific article: A step-by-step guide for beginners ScienceDirect

1. Background Every researcher has been face to face with a blank page at some stage of their career, wondering where to start and what to write first. Describing one's research work in a format that is comprehensible to others, and acceptable for publication is no easy task. When you invest a lot of time, energy and often money in your research, you become intimately and emotionally involved. Naturally, you are convinced of the value of your research, and of its importance for the scientific community. However, the subjectivity that goes hand in hand with deep involvement can make it difficult to take a step back, and think clearly about how best to present the research in a clear and understandable fashion, so that others-likely, non experts in your field-can also appreciate the interest of your findings. Even today, the old adage ''publish or perish'' remains valid. Many young researchers find themselves under pressure to produce scientific publications, in order to enhance their career prospects, or to substantiate requests for funding, or to justify previous funding allocations, or as a requirement for university qualifications such as a Masters degree or doctoral thesis. Yet, often, young doctors do not have much training, if any, in the art of writing a scientific article. For clinicians, in particular, the clinical workload can be such that research and scientific writing are seen to be secondary activities that are not an immediate priority, and to which only small amounts of time can be devoted on an irregular basis. However, the competition is already quite fierce amongst all the good quality papers that are submitted to journals, and it is therefore of paramount importance to get the basics right, in order for your paper to have a chance of succeeding. Don't you think that your work deserves to be judged on its scientific merit, rather than be rejected for poor quality writing and messy and confusing presentation of the data? With this in mind, we present here a step-by-step guide to writing a scientific article, which is not specific to the discipline of geriatrics/gerontology, but rather, may be applied to the vast majority of medical disciplines. We will start by outlining the main sections of the article, and will then describe in greater detail the main elements that should feature in each section. Finally, we will also give a few pointers for the abstract and the title of the article. This guide aims to help young researchers with little experience of writing to create a good quality first draft of their work, which can then be circulated to their co-authors and senior mentors for further refinement, with the ultimate aim of achieving publication in a scientific journal. It is undoubtedly not exhaustive, and many excellent resources can be found in the existing literature [1-7] and online [8]. Many young researchers find it extremely difficult to write scientific articles, and few receive specific training in the art of presenting their research work in written format. Yet, publication is often vital for career advancement, to obtain funding, to obtain academic qualifications, or for all these reasons. We describe here the basic steps to follow in writing a scientific article. We outline the main sections that an average article should contain; the elements that should appear in these sections, and some pointers for making the overall result attractive and acceptable for publication. ß

Related Papers

Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India

Mary Kurien

Biologia Futura

Payam BEHZADI

Scientific writing is an important skill in both academia and clinical practice. The skills for writing a strong scientific paper are necessary for researchers (comprising academic staff and health-care professionals). The process of a scientific research will be completed by reporting the obtained results in the form of a strong scholarly publication. Therefore, an insufficiency in scientific writing skills may lead to consequential rejections. This feature results in undesirable impact for their academic careers, promotions and credits. Although there are different types of papers, the original article is normally the outcome of experimental/epidemiological research. On the one hand, scientific writing is part of the curricula for many medical programs. On the other hand, not every physician may have adequate knowledge on formulating research results for publication adequately. Hence, the present review aimed to introduce the details of creating a strong original article for publi...

Journal of Anesthesia & Critical Care: Open Access

jay shubrook

Kosin Medical Journal

Gwansuk Kang

Excellent research in the fields of medicine and medical science can advance the field and contribute to human health improvement. In this aspect, research is important. However, if researchers do not publish their research, their efforts cannot benefit anyone. To make a difference, researchers must disseminate their results and communicate their opinions. One way to do this is by publishing their research. Therefore, academic writing is an essential skill for researchers. However, preparing a manuscript is not an easy task, and it is difficult to write well. Following a structure may be helpful for researchers. For example, the standard structure of medical and medical science articles includes the following sections: introduction, methods, results, and discussion (IMRAD). The purpose of this review is to present an introduction for researchers, especially novices, on how to write an original article in the field of medicine and medical science. Therefore, we discuss how to prepare...

Mohsen Rezaeian

European Journal of Translational and Clinical Medicine

Journal of Society of Anesthesiologists of Nepal

Bikal Ghimire

Writing is an art and like any art form, it needs perseverance, dedication and practice. However, to write a good quality paper, the habit of reading scientific articles and analyzing them is very important. With the advent of internet and online publishing, we have access to colossal research articles on myriads of subjects making extraordinary conclusions. Evidence based practice requires us to rely on literature for our clinical practice, and we have abundant publications on all aspects claiming to justify all sides of the argument. In this context it becomes more important for all in clinical practice to be able to dissect an article and analyze it in details.

Margaret Cargill

This book shows scientists how to apply their analysis and synthesis skills to overcoming the challenge of how to write, as well as what to write, to maximise their chances of publishing in international scientific journals. The book uses analysis of the scientific article genre to provide clear processes for writing each section of a manuscript, starting with clear ‘story’ construction and packaging of results. Each learning step uses practical exercises to develop writing and data presentation skills based on reader analysis of well-written example papers. Strategies are presented for responding to referee comments, and for developing discipline-specific English language skills for manuscript writing and polishing. The book is designed for scientists who use English as a first or an additional language, and for individual scientists or mentors or a class setting. In response to reader requests, the new edition includes review articles and the full range of research article formats...

Microsurgery

Pao-Yuan Lin

Problems of Education in the 21st Century, ISSN 1822-7864

Vincentas Lamanauskas

Writing and publishing scientific articles (research, review, position etc. articles) are referred to as responsible academic activities. Any scientist/researcher is somehow involved in scientific writing. Thus, this is a technique assisting the researcher with demonstrating individual performance. Most of the main scientific/research journals are published in English, and therefore scientific information is made internationally available by a wide audience and actually becomes accessible to every scientist and/or researcher. On the other hand, a valid point is that scientific/research journals are published in different national languages. Nevertheless, it should be noted that science policy has recently become one-dimensional and resulting in a blind orientation towards support for scientific/research journals published in English. As noted by Poviliunas and Ramanauskas (2008), national languages face a legitimate risk of becoming domesticated and to one degree or another being excluded from scientific, cultural, education and public areas of life. However, this is material for another discussion. Still, every researcher finds relevant to properly prepare a scientific article, i.e. describe the conducted research and publish the obtained results. The previous editorial attempts were made to discuss the fundamental structural elements of the scientific/research article, including the title, summary and keywords (Lamanauskas, 2019). This time, efforts are exerted to share certain insights and gained experience in writing the introduction to the article.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Ajmal Kakar

Acta Med Indones

Kuntjoro Harimurti , Siti Setiati

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH

Alaine Reschke-Hernandez

International journal of endocrinology and metabolism

Parvin Mirmiran

Problems of Education in the 21st Century

Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara

Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara (Open Access) , Oscar R. Gómez

Indian Journal of Ophthalmology

Sabyasachi Sengupta , Pradeep Ramulu

pramod chaitanya

Kathleen Fahy

Christian C Ezeala

IAA Journal of Applied Sciences

EZE V A L H Y G I N U S UDOKA

ANZ Journal of Surgery

Gregory M Malham

طلال العمري

Janne Harkonen

International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology

International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology IJSRST

Fernando Guimaraes

ANAESTHESIA, PAIN & INTENSIVE CARE

Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care , Logan Danielson

Journal of Urban Ecology

Mark J McDonnell

Dhaulagiri Journal of Sociology and Anthropology

Man Bahadur Khattri

Muktikesh Dash

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

[Guide to write a scientific article]

Affiliation.

- 1 Unidad de Trastornos del Movimiento y Sueño, Hospital General Dr. Manuel Gea González, Ciudad de México, México. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 37931496

- DOI: 10.1016/j.regg.2023.101424

Publishing a scientific article is challenging for early-career researchers and clinicians. Success is not solely determined by robust research methods, but also by clear and logical presentation of results. Without clear communication, disruptive findings can be overlooked. A well-structured manuscript leads the reader logically from the introduction to the conclusion. Maintaining a consistent narrative ensures lasting impact. In this paper, we provide practical guidelines for drafting an effective scientific manuscript. Carefully crafted articles increase the chance of acceptance and improve comprehension among diverse specialists. We emphasize the importance of presenting a clear, relevant, and engaging story within a structured framework, highly valued by editors, reviewers, and readers.

Keywords: Ciencia; Científicos jóvenes; Escritura; Investigación; Publicación; Publishing; Research; Scientific; Writing; Young Scientists.

Copyright © 2023 SEGG. Publicado por Elsevier España, S.L.U. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Creating Logical Flow When Writing Scientific Articles. Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ. Barroga E, et al. J Korean Med Sci. 2021 Oct 18;36(40):e275. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e275. J Korean Med Sci. 2021. PMID: 34664802 Free PMC article. Review.

- A brief guide to the science and art of writing manuscripts in biomedicine. Forero DA, Lopez-Leon S, Perry G. Forero DA, et al. J Transl Med. 2020 Nov 10;18(1):425. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02596-2. J Transl Med. 2020. PMID: 33167977 Free PMC article. Review.

- Rules to be adopted for publishing a scientific paper. Picardi N. Picardi N. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:1-3. Ann Ital Chir. 2016. PMID: 28474609

- Research: Why and how to write a paper? Light RW. Light RW. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2015 Oct;215(7):401-4. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2015.04.007. Epub 2015 Jun 6. Rev Clin Esp (Barc). 2015. PMID: 26059689 English, Spanish.

- How to Write Articles that Get Published. Jha KN. Jha KN. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014 Sep;8(9):XG01-XG03. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/8107.4855. Epub 2014 Sep 20. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014. PMID: 25386508 Free PMC article.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Ediciones Doyma, S.L.

- Elsevier Science

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

How does hail grow to the size of golf balls and even grapefruit? The science behind this destructive weather phenomenon

Associate Professor of Atmospheric Science, University at Albany, State University of New York

Disclosure statement

Brian Tang has received funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Risk Prediction Initiative.

University at Albany, State University of New York provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Hail the size of grapefruit shattered car windows in Johnson City, Texas. In June, 2024, a storm chaser found a hailstone almost as big as a pineapple . Even larger hailstones have been documented in South Dakota , Kansas and Nebraska. Hail has damaged airplanes and even crashed through the roofs of houses.

How do hailstones get so large, and are hailstorms getting worse?

As an atmospheric scientist , I study and teach about extreme weather and its risks. Here’s how hail forms, how hailstorms may be changing, and some tips for staying safe.

How does hail get so big?

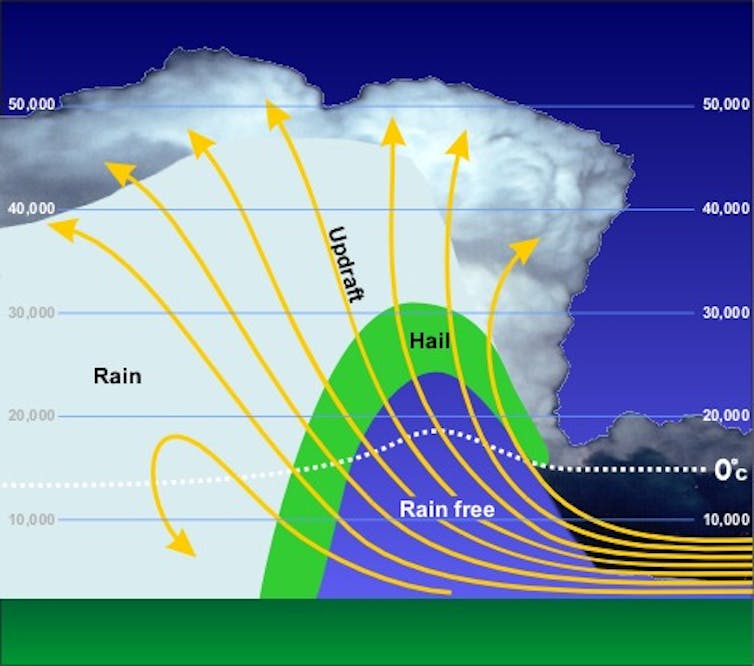

Hail begins as tiny crystals of ice that are swept into a thunderstorm’s updraft. As these ice embryos collide with supercooled water – liquid water that has a temperature below freezing – the water freezes around each embryo, causing the embryo to grow .

Supercooled water freezes at different rates, depending on the temperature of the hailstone surface, leaving layers of clear or cloudy ice as the hailstone moves around inside a thunderstorm. If you cut open a large hailstone, you can see those layers, similar to tree rings.

The path a hailstone takes through a thunderstorm cloud, and the time it spends collecting supercooled water, dictates how large it can grow.

Rotating, long-lived, severe thunderstorms called supercells tend to produce the largest hail . In supercells, hailstones can be suspended for 10-15 minutes or more in strong thunderstorm updrafts, where there is ample supercooled water, before falling out of the storm due to their weight or moving out of the updraft.

Hail is most common during spring and summer when a few key ingredients are present: warm, humid air near the surface; an unstable air mass in the middle troposphere; winds strongly changing with height; and thunderstorms triggered by a weather system.

Larger hail, more damage

Hailstorms can be destructive, particularly for farms, where barrages of even small hail can beat down crops and damage fruit .

As hailstones get larger, their energy and force when they strike objects increases dramatically. Baseball-sized hail falling from the sky has as much kinetic energy as a typical major league fastball. As a result, property damage – such as to roofs, siding, windows and cars – increases as hail gets larger than the size of a quarter.

Insured losses from severe weather, which are dominated by hail damage , have increased substantially over the past few decades. These increases have been driven mostly by growing populations in hail-prone areas, resulting in more property that can be damaged and the increasing costs to repair or replace property damaged by hail.

Is climate change worsening hailstorms?

A lot of people ask whether the rise in hail damage is tied to climate change.

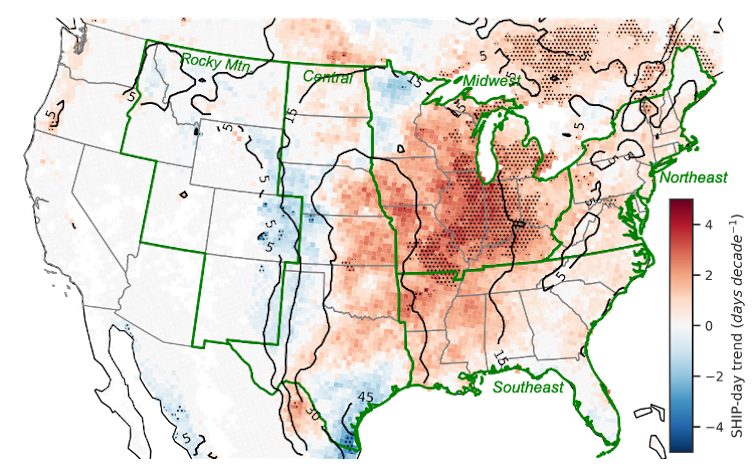

My colleagues and I analyzed four decades of hail environments and found that the atmospheric ingredients to produce very large hail – larger than golf balls – have become more common in parts of the central and eastern U.S. since 1979. Other studies that considered formation factors of hail-producing storms or looked at radar estimates of hail have found limited increases in large hail, predominately over the northern Plains.

There are a couple of primary hypotheses as to why climate change may be making some key ingredients for large hail more common.

First, there has been an increase in warm, humid air as the Earth warms. This supplies more energy to thunderstorms and makes supercooled water more plentiful in thunderstorms for hail to grow.

Second, there have been more unstable air masses , originating over the higher terrain of western North America, that then move eastward. As snowpack disappears earlier in the year, these unstable air masses are more apt to form as the Sun heats up the land faster, similar to turning up a kitchen stove, which then heats up the atmosphere above.

Climate change may also lead to less small hail and more large hail . As the atmosphere warms, the freezing level moves up higher in the atmosphere. Small hail would be able to melt completely before reaching the ground. Larger hail, on the other hand, falls faster and requires more time to melt, so it would be less affected by higher freezing levels.

Additionally, the combination of more favorable ingredients for large hail and changes in the character of hailstorms themselves might lead to an increase in very large hail in the future .

How to stay safe in a hailstorm

Being caught in a severe thunderstorm with large hail falling all around you can be frightening. Here are some safety tips if you ever wind up in such a situation:

If you’re driving, pull over safely. Stay in the vehicle. If you spot a garage or gas station awning that you can seek shelter under, drive to it.

If you’re outside, seek a sturdy shelter such as a building. If you’re caught out in the open, protect your head.

If you’re inside, stay away from windows and remain inside until the hail stops.

Dealing with the aftermath of hail damage can also be stressful, so taking some steps now can avoid headaches later. Know what your homeowners and car insurance policies cover. Be aware of roof replacement scams from people after a hailstorm. Also, think preventively by choosing building materials that can better withstand hail damage in the first place.

- Extreme weather

- Atmospheric science

- Thunderstorms

- Disaster insurance

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Senior Research Fellow - Neuromuscular Disorders and Gait Analysis

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Nigel Farage’s claim that NATO provoked Russia is naive and dangerous

It is also a wilful misreading of history.

O n June 21st Nigel Farage acknowledged that the war in Ukraine was the fault of Vladimir Putin, but told the BBC that Russia’s president had been “provoked” by NATO and the European Union. The leader of Reform UK , the populist party snapping at the heels of the governing Conservatives in pre-election polling and threatening to push them into third place, was echoing Mr Putin’s own arguments. The Russian leader is focused mostly on NATO , which provides the hard security that makes the EU safe. He complains that the alliance’s expansion into central and eastern Europe after the cold war made Russia’s position intolerable. Some Western scholars concur .

Mr Farage and Mr Putin have the argument upside down. Countries join NATO not to antagonise Russia, but because they are threatened by it . To understand how the arguments have shifted, you need to look back to the unstable politics of Europe in the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Back then Boris Yeltsin, Mr Putin’s predecessor, complained when members of the old Warsaw Pact applied to join. Over the years this hardened into the line of reasoning cited by Mr Putin as justification for massing troops on Ukraine’s border. It is an argument that has gained currency in much of the world. It is flimsy at best.

Critics of NATO enlargement say that it breaks an undertaking that James Baker, then America’s secretary of state, gave to Russia in February 1990 that NATO would not expand eastward. They add that it was also unwise. As NATO grew, Russia felt increasingly threatened, and was bound to protect itself by resisting. That is also the nub of Mr Farage’s argument. Some go on to point out that the West had other ways than NATO to enhance its security, such as the Partnership for Peace, which sets out to strengthen security relations between the alliance and non-members.

Mr Baker’s supposed undertaking is a red herring. He was speaking about NATO in eastern Germany and his words were overtaken by the collapse of the Warsaw Pact nearly 18 months later. NATO and Russia signed a co-operation agreement in 1997, which did not contain any restriction on new members even though enlargement had been discussed. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined almost two years later.

The undertaking that matters is the one that Russia gave in 1994, when Ukraine surrendered the nuclear weapons based on its territory. Among other things, Russia pledged not to use economic or military coercion against its neighbour. Its violations of this promise in 2014, when it seized Crimea and part of the Donbas region, and again on February 24th 2022 have been flagrant. Russia now claims, disingenuously, that the agreement from 1994 only covered nuclear war.

In fact NATO has every right to expand, if that is what applicants desire. Under the Helsinki Final Act, signed in 1975, including by the Soviet Union, countries are free to choose their own alliances. Is it any surprise that former members of the Warsaw Pact, which had suffered so grievously under Soviet rule, should have sought a haven?

The decision of Finland and Sweden to apply for membership of NATO in May 2022 illustrates why they might. For many years public opinion in Finland and Sweden had been against joining NATO . It shifted as a direct result of the invasion of Ukraine, which Mr Putin ordered ostensibly to forestall NATO ’s expansion. Two countries proud of their long history of military non-alignment came to judge that the risk of antagonising their neighbour was outweighed by the extra security they would gain from joining an alliance dedicated to resisting Russian aggression. The right for sovereign countries to determine their own destinies is one of the many things at stake in the war.

Critics of enlargement retort that NATO should have said no to central and eastern Europe all the same. Expansion was bound to make Russia paranoid and insecure. Even though NATO is a defensive alliance, the government in Moscow perceives it as a threat. When Mr Putin attempts to restore his security, say by modernising his armed forces, NATO , in turn, perceives heightened Russian aggression. Especially provocative was NATO ’s Bucharest summit in 2008, which promised membership to Ukraine and Georgia, countries that Russia considers essential for its security.

Such security dilemmas are common in the study of international relations, and one clearly exists between Russia and the West. But to blame the West for triggering it is scarcely credible. One reason is domestic. Mr Putin has increasingly used nationalism, Orthodox religion and violence to shore up his rule. He needs enemies abroad to persuade his people that they and their civilisation are under threat. Seizing territory in Georgia in 2008 and in Ukraine in 2014 and today has been part of that strategy.

The other reason is international. Russia has a long history as an imperial power and, like most declining empires, it finds the prospect of becoming just another country hard to swallow. Instead, Russia wants to undermine alliances like NATO that keep the West secure. Regardless of NATO expansion, Russia was likely to resist forcibly as its periphery drifted off. Backing off today by abandoning Ukraine, or attempting to impose a peace on it, would only invite the next aggression from Mr Putin.

Were there alternatives to NATO membership? Here, the choice of Finland and Sweden speaks loudly. Both are long-term members of the Partnership for Peace. Clearly, neither felt that this offered them sufficient protection. If one of them were attacked, NATO would have no commitment to intervene. Nor would America and British nuclear weapons have covered the two countries, as they do the rest of the alliance.