Home » Education » Difference Between Introduction and Literature Review

Difference Between Introduction and Literature Review

Main difference – introduction vs literature review.

Although introduction and literature review are found towards the beginning of a text, there is a difference between them in terms of their function and purpose. The main difference between introduction and literature review is their purpose; the purpose of an introduction is to briefly introduce the text to the readers whereas the purpose of a literature review is to review and critically evaluate the existing research on a selected research area.

In this article, we will be discussing,

1. What is an Introduction? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

2. What is a Literature Review? – Definition, Features, Characteristics

What is an Introduction

An introduction is the first part of an article, paper, book or a study that briefly introduces what will be found in the following sections. An introduction basically introduces the text to the readers. It may contain various types of information, but given below some common elements that can be found in the introduction section.

- Background/context to the paper

- Outline of key issues

- Thesis statement

- Aims and purpose of the paper

- Definition of terms and concepts

Note that some introductions may not have all these elements. For example, an introduction to a short essay will only have several lines. Introductions can be found in nonfiction books, essays, research articles, thesis, etc. There can be slight variations in these various genres, but all these introductions will provide a basic outline of the whole text.

Introduction of a thesis or dissertation will describe the background of the research, your rationale for the thesis topic, what exactly are you trying to answer, and the importance of your research.

What is a Literature Review

A literature review, which is written at the start of a research study, is essential to a research project. A literature review is an evaluation of the existing research material on a selected research area. This involves reading the major published work (both printed and online work) in a chosen research area and reviewing and critically evaluating them. A literature review should show the researcher’s awareness and insight of contrasting arguments, theories, and approaches. According to Caulley (1992) a good literature review should do the following:

- Compare and contrast different researchers’ views

- Identify areas in which researchers are in disagreement

- Group researchers who have similar conclusions

- Criticize the research methodology

- Highlight exemplary studies

- Highlight gaps in research

- Indicate the connection between your study and previous studies

- Indicate how your study will contribute to the literature in general

- Conclude by summarizing what the literature says

Literature reviews help researchers to evaluate the existing literature, to identify a gap in the research area, to place their study in the existing research and identify future research.

Introduction is at the beginning of a text.

Literature Review is located after the introduction or background.

Introduction introduces the main text to the readers.

Literature Review critically evaluates the existing research on the selected research area and identifies the research gap.

Introduction will have information such as background/context to the paper, outline of key issues, thesis statement, aims, and purpose of the paper and definition of terms and concepts.

Literature Review will have summaries, reviews, critical evaluations, and comparisons of selected research studies.

Image Courtesy: Pixabay

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

When you need an introduction for a literature review, what to include in a literature review introduction, examples of literature review introductions, steps to write your own literature review introduction.

A literature review is a comprehensive examination of the international academic literature concerning a particular topic. It involves summarizing published works, theories, and concepts while also highlighting gaps and offering critical reflections.

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

Instead, you should always offer some form of introduction to orient the reader and clarify what they can expect.

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

- Academic literature review papers: When your literature review constitutes the entirety of an academic review paper, a more substantial introduction is necessary. This introduction should resemble the standard introduction found in regular academic papers.

- Literature review section in an academic paper or essay: While this section tends to be brief, it’s important to precede the detailed literature review with a few introductory sentences. This helps orient the reader before delving into the literature itself.

- Literature review chapter or section in your thesis/dissertation: Every thesis and dissertation includes a literature review component, which also requires a concise introduction to set the stage for the subsequent review.

You may also like: How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

In practical terms, this implies, for instance, that the introduction in an academic literature review paper, especially one derived from a systematic literature review , is quite comprehensive. Particularly compared to the rather brief one or two introductory sentences that are often found at the beginning of a literature review section in a standard academic paper. The introduction to the literature review chapter in a thesis or dissertation again adheres to different standards.

Here’s a structured breakdown based on length and the necessary information:

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

- The research problem: Clearly articulate the problem or question that your literature review aims to address.

- The research gap: Highlight the existing gaps, limitations, or unresolved aspects within the current body of literature related to the research problem.

- The research relevance: Explain why the chosen research problem and its subsequent investigation through a literature review are significant and relevant in your academic field.

- The literature review method: If applicable, describe the methodology employed in your literature review, especially if it is a systematic review or follows a specific research framework.

- The main findings or insights of the literature review: Summarize the key discoveries, insights, or trends that have emerged from your comprehensive review of the literature.

- The main argument of the literature review: Conclude the introduction by outlining the primary argument or statement that your literature review will substantiate, linking it to the research problem and relevance you’ve established.

- Preview of the literature review’s structure: Offer a glimpse into the organization of the literature review paper, acting as a guide for the reader. This overview outlines the subsequent sections of the paper and provides an understanding of what to anticipate.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will provide a clear and structured overview of what readers can expect in your literature review paper.

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

Most academic articles or essays incorporate regular literature review sections, often placed after the introduction. These sections serve to establish a scholarly basis for the research or discussion within the paper.

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

- An introduction to the topic: When delving into the academic literature on a specific topic, it’s important to provide a smooth transition that aids the reader in comprehending why certain aspects will be discussed within your literature review.

- The core argument: While literature review sections primarily synthesize the work of other scholars, they should consistently connect to your central argument. This central argument serves as the crux of your message or the key takeaway you want your readers to retain. By positioning it at the outset of the literature review section and systematically substantiating it with evidence, you not only enhance reader comprehension but also elevate overall readability. This primary argument can typically be distilled into 1-2 succinct sentences.

In some cases, you might include:

- Methodology: Details about the methodology used, but only if your literature review employed a specialized method. If your approach involved a broader overview without a systematic methodology, you can omit this section, thereby conserving word count.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will effectively integrate your literature review into the broader context of your academic paper or essay. This will, in turn, assist your reader in seamlessly following your overarching line of argumentation.

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

The literature review typically constitutes a distinct chapter within a thesis or dissertation. Often, it is Chapter 2 of a thesis or dissertation.

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

- Purpose of the literature review and its relevance to the thesis/dissertation research: Explain the broader objectives of the literature review within the context of your research and how it contributes to your thesis or dissertation. Essentially, you’re telling the reader why this literature review is important and how it fits into the larger scope of your academic work.

- Primary argument: Succinctly communicate what you aim to prove, explain, or explore through the review of existing literature. This statement helps guide the reader’s understanding of the review’s purpose and what to expect from it.

- Preview of the literature review’s content: Provide a brief overview of the topics or themes that your literature review will cover. It’s like a roadmap for the reader, outlining the main areas of focus within the review. This preview can help the reader anticipate the structure and organization of your literature review.

- Methodology: If your literature review involved a specific research method, such as a systematic review or meta-analysis, you should briefly describe that methodology. However, this is not always necessary, especially if your literature review is more of a narrative synthesis without a distinct research method.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will empower your literature review to play a pivotal role in your thesis or dissertation research. It will accomplish this by integrating your research into the broader academic literature and providing a solid theoretical foundation for your work.

Comprehending the art of crafting your own literature review introduction becomes significantly more accessible when you have concrete examples to examine. Here, you will find several examples that meet, or in most cases, adhere to the criteria described earlier.

Example 1: An effective introduction for an academic literature review paper

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

The entire introduction spans 611 words and is divided into five paragraphs. In this introduction, the authors accomplish the following:

- In the first paragraph, the authors introduce the broader topic of the literature review, which focuses on innovation and its significance in the context of economic competition. They underscore the importance of this topic, highlighting its relevance for both researchers and policymakers.

- In the second paragraph, the authors narrow down their focus to emphasize the specific role of culture in relation to innovation.

- In the third paragraph, the authors identify research gaps, noting that existing studies are often fragmented and disconnected. They then emphasize the value of conducting a systematic literature review to enhance our understanding of the topic.

- In the fourth paragraph, the authors introduce their specific objectives and explain how their insights can benefit other researchers and business practitioners.

- In the fifth and final paragraph, the authors provide an overview of the paper’s organization and structure.

In summary, this introduction stands as a solid example. While the authors deviate from previewing their key findings (which is a common practice at least in the social sciences), they do effectively cover all the other previously mentioned points.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

The paper begins with a general introduction and then proceeds to the literature review, designated by the authors as their conceptual framework. Of particular interest is the first paragraph of this conceptual framework, comprising 142 words across five sentences:

“ A peripheral and marginalised nationality within a multinational though-Persian dominated Iranian society, the Kurdish people of Iranian Kurdistan (a region referred by the Kurds as Rojhelat/Eastern Kurdi-stan) have since the early twentieth century been subject to multifaceted and systematic discriminatory and exclusionary state policy in Iran. This condition has left a population of 12–15 million Kurds in Iran suffering from structural inequalities, disenfranchisement and deprivation. Mismanagement of Kurdistan’s natural resources and the degradation of its natural environmental are among examples of this disenfranchisement. As asserted by Julian Agyeman (2005), structural inequalities that sustain the domination of political and economic elites often simultaneously result in environmental degradation, injustice and discrimination against subaltern communities. This study argues that the environmental struggle in Eastern Kurdistan can be asserted as a (sub)element of the Kurdish liberation movement in Iran. Conceptually this research is inspired by and has been conducted through the lens of ‘subalternity’ ” ( Hassaniyan, 2021, p. 931 ).

In this first paragraph, the author is doing the following:

- The author contextualises the research

- The author links the research focus to the international literature on structural inequalities

- The author clearly presents the argument of the research

- The author clarifies how the research is inspired by and uses the concept of ‘subalternity’.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

While introductions to a literature review section aren’t always required to offer the same level of study context detail as demonstrated here, this introduction serves as a commendable model for orienting the reader within the literature review. It effectively underscores the literature review’s significance within the context of the study being conducted.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

The introduction to a literature review chapter can vary in length, depending largely on the overall length of the literature review chapter itself. For example, a master’s thesis typically features a more concise literature review, thus necessitating a shorter introduction. In contrast, a Ph.D. thesis, with its more extensive literature review, often includes a more detailed introduction.

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

The first example is “Benchmarking Asymmetrical Heating Models of Spider Pulsar Companions” by P. Sun, a master’s thesis completed at the University of Manchester on January 9, 2024. The author, P. Sun, introduces the literature review chapter very briefly but effectively:

PhD thesis literature review chapter introduction

The second example is Deep Learning on Semi-Structured Data and its Applications to Video-Game AI, Woof, W. (Author). 31 Dec 2020, a PhD thesis completed at the University of Manchester . In Chapter 2, the author offers a comprehensive introduction to the topic in four paragraphs, with the final paragraph serving as an overview of the chapter’s structure:

PhD thesis literature review introduction

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Having absorbed all of this information, let’s recap the essential steps and offer a succinct guide on how to proceed with creating your literature review introduction:

- Contextualize your review : Begin by clearly identifying the academic context in which your literature review resides and determining the necessary information to include.

- Outline your structure : Develop a structured outline for your literature review, highlighting the essential information you plan to incorporate in your introduction.

- Literature review process : Conduct a rigorous literature review, reviewing and analyzing relevant sources.

- Summarize and abstract : After completing the review, synthesize the findings and abstract key insights, trends, and knowledge gaps from the literature.

- Craft the introduction : Write your literature review introduction with meticulous attention to the seamless integration of your review into the larger context of your work. Ensure that your introduction effectively elucidates your rationale for the chosen review topics and the underlying reasons guiding your selection.

Master Academia

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The best answers to "What are your plans for the future?"

10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles.

Introduce yourself in a PhD interview (4 simple steps + examples)

37 creative ways to get motivation to study

Types of editorial decisions after peer review (+ how to react)

Minor revisions: Sample peer review comments and examples

Introductions and Literature Reviews

- Author By Troy Mikanovich

- Publication date December 16, 2022

- Categories: Academic Publication , Research Writing

- Categories: academic journal , CARS , introduction , literature review , research , research question

Writing literature reviews is one of the trickiest things you’ll have to do in graduate school. It is even more tricky because a lot of professors will want you to do things that are pedagogically valuable but so tailored to the specific class they are teaching that it can be hard to generalize the lessons you are meant to take away.

This page is meant to be a general overview to the goals and purposes of introductions and literature reviews (or an introduction that contains a literature review–we’ll talk about that), so even if it doesn’t exactly match what you have been asked to do in an assignment, I hope it’ll be helpful.

What is the difference between an introduction and a literature review?

As of writing this, the year is 2022 and words mean nothing. Rather than getting caught up on what these things are in some kind of objective sense, let’s look at what they are supposed to do.

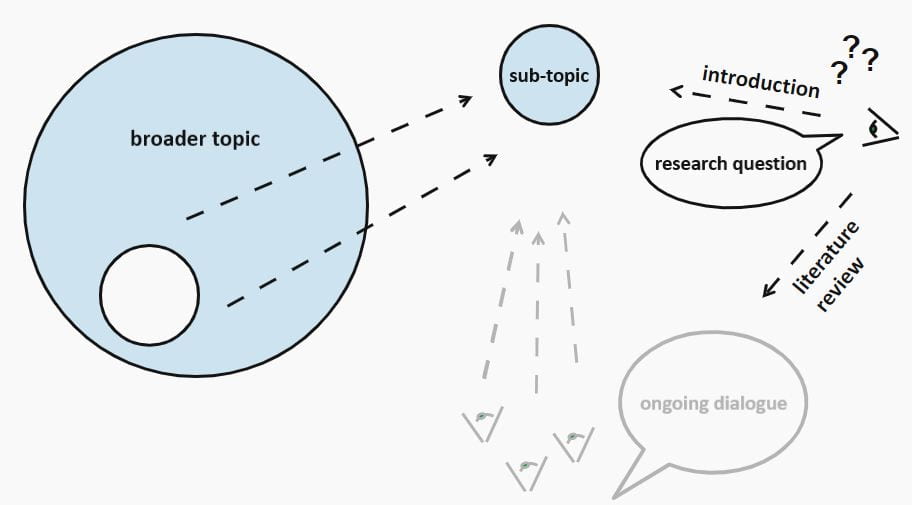

The introduction and the literature review of your paper have the same job. Both are supposed to justify the question(s) you are asking about your topic and to demonstrate to your audience that the thing you are writing about is interesting and of some importance. However, while they have the same job, they do it in two different ways.

An introduction should demonstrate that there is some broader real-world significance to the thing that you are writing about. You can do this by establishing a problem or a puzzle or by giving some background information on your topic to show why it is important. Here’s an example from Brian E. Bride’s “Prevalence of Secondary Traumatic Stress among Social Workers” (2007, link below), where he begins by establishing a problem:

“ In the United States, the lifetime prevalence of exposure to traumatic events ranges from 40 percent to 81 percent, with 60.7 percent of men and 51.2 percent of women having been exposed to one or more traumas and 19.7 percent of men and 11.4 percent of women reporting exposure to three or more such events (Breslau, Davis, Peter-son, & Schultz, 1997; Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, & Nelson, 1995; Stein, walker, Hazen, & Forde, 1997). Although exposure to traumatic events is high in the general population, it is even higher in subpopulations to whom social workers are likely to provide services…

Although not exhaustive of the populations with whom social workers practice, these examples illustrate that social workers face a high rate of professional contact with traumatized people. Social workers are increasingly being called on to assist survivors of childhood abuse, domestic violence, violent crime, disasters, and war and terrorism. It has become increasingly apparent that the psychological effects of traumatic events extend beyond those directly affected.”

So, Bride (2007) starts with a broad problem (lots of people with exposure to traumatic events) and narrows it to a more specific problem (social workers who work with those people are exposed to secondary trauma as they assist them) .

A literature review should demonstrate that there is some academic significance to the thing you are writing about. You can do this by establishing a scholarly problem (i.e. a “research gap”) and by demonstrating that the state of the existing scholarship on your topic needs to develop in a particular way.

As Bride (2007) transitions to talking about the scholarship on the topic of social workers and secondary trauma, he establishes what scholarship has done and identifies what it has not done .

“Figley (1999) defined secondary traumatic stress as “the natural, consequent behaviors and emotions resulting from knowledge about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other. It is the stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person” (p. 10). Chrestman (1999) noted that secondary traumatization includes symptoms parallel to those observed in people di-rectly exposed to trauma such as intrusive imagery related to clients’ traumatic disclosures (Courtois, 1988; Danieli, 1988; Herman, 1992; McCann & Pearlman, 1990); avoidant responses (Courtois; Haley, 1974); and physiological arousal (Figley, 1995; McCann & Pearlman, 1990). Thus, STS is a syndrome of symptoms identical to those of PTSD, the characteristic symptoms of which are intrusion, avoidance, and arousal (Figley, 1999)…

Collectively, these studies have provided empirical evidence that individuals who provide services to traumatized populations are at risk of experiencing symptoms of traumatic stress (Bride). However, the extant literature fails to document the prevalence of individual STS symptoms and the extent to which diagnostic criteria for PTSD are met as a result of work with traumatized populations.”

Taken together, Bride (2007) justifies its existence–the research that the author has undertaken in order to read the article that you are now reading–like this:

Broad real world background: Lots of people are suffering from traumatic stress.

Narrowed real world background: People who have suffered traumatic experiences often work with social workers.

Real world problem: Many social workers may through their work suffer from secondary exposure to traumatic experiences.

Broad academic background: There has been a lot of research on secondary traumatic stress

Narrowed academic background: Particularly, this research has shown that social workers are at risk of experiencing symptoms of secondary traumatic stress.

Academic problem/gap : We don’t know how prevalent individual symptoms of secondary traumatic stress are.

Introductions, then, give you space to explain why you are writing about the thing you are writing about, and literature reviews are where you explain what prior scholarship has said about the topic and what the consequences of that prior scholarship are. In an introduction you are writing about the topic; in a literature review you are writing about people writing about the topic.

So does a literature review need to be a separate section from an introduction? Or is a literature review part of an introduction?

It depends on your field, tbh. And on the expectations of the assignment/journal/outlet that you are writing for.

For instance, in the above example (Bride, 2007) the literature review is a part of the introduction. Here’s that paper and some other examples of other places where this is the case. Notice that they do not differentiate between an introductory section and a distinct “Literature Review” as they outline their topic/questions before describing their methodology:

Bride, B. E. (2007) Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52 (1), 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.63

Wei, X., Teng, X., Bai, J., & Ren, F. (2022). Intergenerational transmission of depression during adolescence: The mediating roles of hostile attribution bias, empathetic concern, and social self-concept. The Journal of Psychology, 157 (1), 13-31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2134276

Stephens, R., Dowber, H., Barrie, A., Sannida, A., & Atkins, K. 2022) Effect of swearing on strength: Disinhibition as a potential mediator. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/17470218221082657

However, plenty of other articles have distinct “Literature Review” sections separate from their introductions. The first two examples name it as such, while the third organizes its literature review with thematic sub-sections:

Schraedley, M.K., & Dougherty, D.S. (2021). Creating and disrupting othering during policymaking in a polarized context. Journal of Communication, 72 (1), 111-140. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab042

Gil de Zúñiga, H., Cheng, Z., & González-González, P. (2022). Effects of the news finds me perception on algorithmic news attitudes and social media political homophily. Journal of Communication, 72 (5), 578-591. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqac025

Brandão, T., Brites, R., Hipólito, J., & Nunes O. (2022) Attachment orientations and family functioning: The mediating role of emotion regulation. The Journal of Psychology , 157 (1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2022.2128284

Whether you separate your literature review into its own distinct section is mostly a function of what you’ve been asked to do (if you are writing for a class) or what the conventions and constraints are of your field.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Research Skills

Introduction and literature review.

This section is the beginning of the article, but don’t expect it to contain any sort of position or argument. In academic articles, this section has one, overarching purpose: to demonstrate that the authors are familiar with all previous relevant research on the issue they are writing about. Therefore, this section is usually the most “citation-heavy” section of the paper. It is not uncommon to have one or more citations at the end of each sentence. You will likely also encounter a number of compound citations: parentheticals in which not one source, but two or more are cited at one time. Each sentence that precedes a citation in this section is typically a very brief paraphrase of the relevant methods or applicable findings of the other articles that have come before. This review of prior studies is a very important exercise for scholars because it demonstrates the depth of their understanding. None of the articles you read occur in a vacuum; they are usually part of an evolving web of scholarship. Each new article picks up the thread (or, usually, several threads) left by articles published recently. Another important thing to realize is that, in a very real sense, the authors have not really begun; they do not make an argument or say much that is new in this section. It is designed to provide an academic history and theoretical context for the topic of discussion.

At the very end of every literature review section, however, the authors do something important. After having demonstrated their familiarity with previous research, authors indicate that, even though much research has been done, there are still gaps in the research that need filling. You should try to find language such as, “While many studies have examined this subject, no one has looked at this particular issue in this way.” The authors then announce their intention to address that gap in knowledge with the research that follows. This rhetorical move always appears at the end of this section, and often gives the reader the clearest and most detailed description of what exactly the authors are looking at—and why. This is not a thesis, however. Academic articles are not like the essays you may be used to writing, in which the thesis appears at the end of the introduction. The research gap is more akin to a hypothesis than a thesis. It does not make an argument, which comes much later—usually in the discussion or conclusion.

There are also articles that are stand-alone literature reviews; these are sometimes called “Review Articles” or “Meta-analyses.” Rather than engaging in original research, these articles, if they are recent and on point, can provide you with the bibliographic information of all the important, recent sources on your topic. There are many ways to find sources that don’t involve a search engine of any kind. Look at your articles’ references lists to see if they contain any relevant-sounding articles that you haven’t found by other means. You can save a great deal of time this way.

- Parts of An Article. Authored by : Kerry Bowers. Provided by : The University of Mississippi. Project : WRIT 250 Committee OER Project. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Privacy Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Introduction vs. Literature Review — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Introduction and Literature Review

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, role in paper, relation to other research, compare with definitions, introduction, literature review, common curiosities, how does a literature review differ from an introduction in terms of content, what should i include in the introduction of my paper, how long should an introduction be, is it essential for a research paper to have both an introduction and a literature review, how detailed should a literature review be, should an introduction be captivating, what's the main purpose of an introduction in academic writing, can a literature review identify gaps in existing research, do all research papers have a literature review section, is the introduction the first section of a research paper, what's the primary goal of a literature review, can an introduction mention previous studies, is the literature review limited to academic articles, is a literature review subjective, can a literature review include recent research, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

Believe in yourself, Prove yourself, Be yourself

Introduction vs Literature Review

Introduction is at the beginning of a text while literature review is located after the introduction or background.

Introduction is the part that introduces the main text to the readers while literature review critically evaluates the existing research on the selected research area and identifies the research gap.

Introduction have elements such as background, outline of key issues, thesis statement, aims and purpose of the paper and definition of terms and concepts while literature review have summaries, reviews, critical evaluations, and comparisons of selected research studies.

Recent Posts

- Experience as reviewer (Year 2024) April 14, 2024

Academic Staff Personal Site

Although I am just someone who does some teaching, some research, and some writing but my dream still alive which is to live in the simplest way, in the way you like with fully appreciation and love.

“Believe in yourself, Prove yourself, Be yourself”

Latest News

- Experience as reviewer (Year 2024)

- Experience as reviewer (Year 2023)

- Post Viva Thesis’ Correction

- Research Method and Research Design

- Research Gap

- WoS or Scopus?

- Professional Certification Received

- Experiences as Coach of Certification and Workshop

- Experiences as Panel of Competition/Booth

- ICICyTA 2022

- As Coach/Trainer

- As Conference Committee

- As Moderator/speaker

- As Reviewer

- As Viva Chair/Co-chair/Examiner (main/co)

- Certification

- News and Knowledge

- RG VicubeLab

- Teaching Courses (Current Semester)

- Teaching Courses (Previous Semesters)

- Course Materials

- Research Grants

- Current Research

- Completed research

Publication

- Journal Papers

- Conference Proceedings

- Books and Book Chapters

- Technical Reports and Other Publications

Supervision

- Undergraduate Supervision

- Main Supervisor (Master/PhD)

- Co-supervisor (Master/PhD)

Useful Links

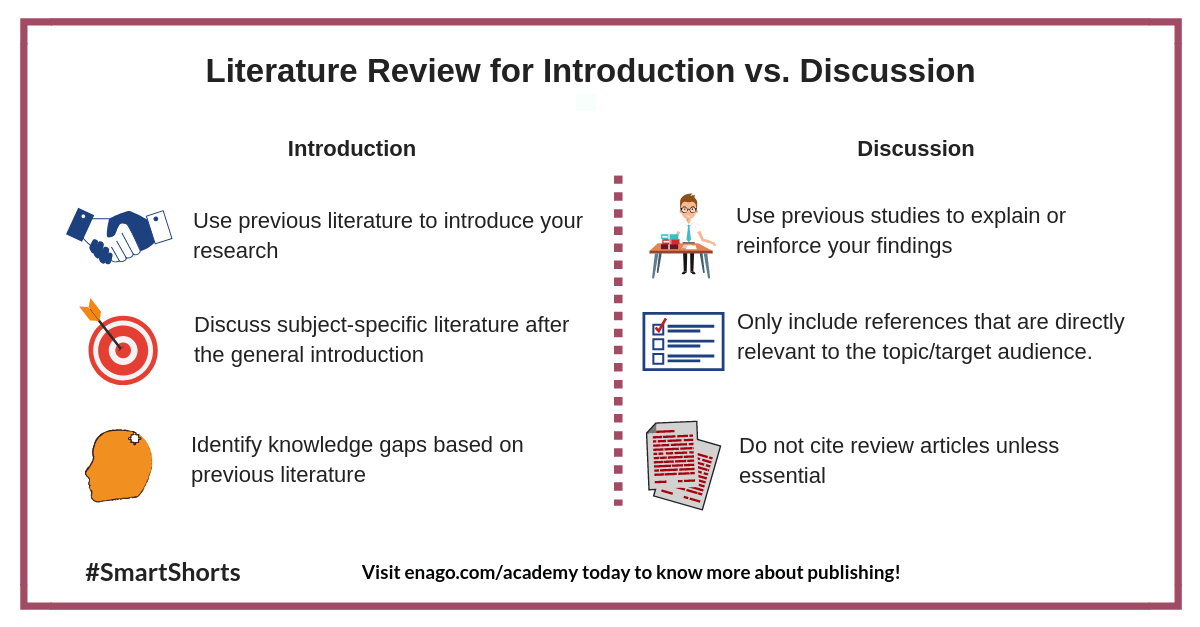

Literature Review for Introduction Vs. Discussion

A literature review presents a summary of studies related to a particular area of research. It identifies and summarizes all the relevant research conducted on a particular topic. Literature reviews are used in the introduction and discussion sections of your manuscripts . However, there are differences in how you can present literature reviews in each section. This smartshort describes how to effectively use literature reviews in these sections. You can also read a detailed article on this topic here.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Top 4 Tools for Keyword Selection

Keywords play an important role in making research discoverable. It helps researchers discover articles relevant…

Top 4 Tools to Create Scientific Images and Figures

A good image or figure can go a long way in effectively communicating your results…

Tips to Effectively Present Your Work

Presenting your work is an important part of scientific communication and is very important for…

Tips to Tackle Procrastination

You can end up wasting a lot of time procrastinating. Procrastination leads you to a…

Rules of Capitalization

Using too much capitalization or using it incorrectly can undermine, clutter, and confuse your writing…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

- Open access

- Published: 02 June 2024

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome: a comparative bibliometric analysis

- Waleed M. Sweileh 1

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases volume 19 , Article number: 221 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

149 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

This study aimed to analyze and map scientific literature on Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome (NMS) and Serotonin Syndrome (SS) from prestigious, internationally indexed journals. The objective was to identify key topics, impactful articles, prominent journals, research output, growth patterns, hotspots, and leading countries in the field, providing valuable insights for scholars, medical students, and international funding agencies.

A systematic search strategy was implemented in the PubMed MeSH database using specific keywords for NMS and SS. The search was conducted in the Scopus database, renowned for its extensive coverage of scholarly publications. Inclusion criteria comprised articles published from 1950 to December 31st, 2022, restricted to journal research and review articles written in English. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel for descriptive analysis, and VOSviewer was employed for bibliometric mapping.

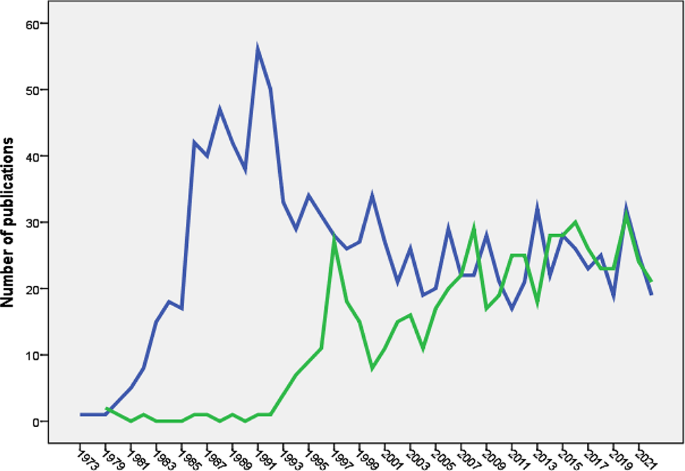

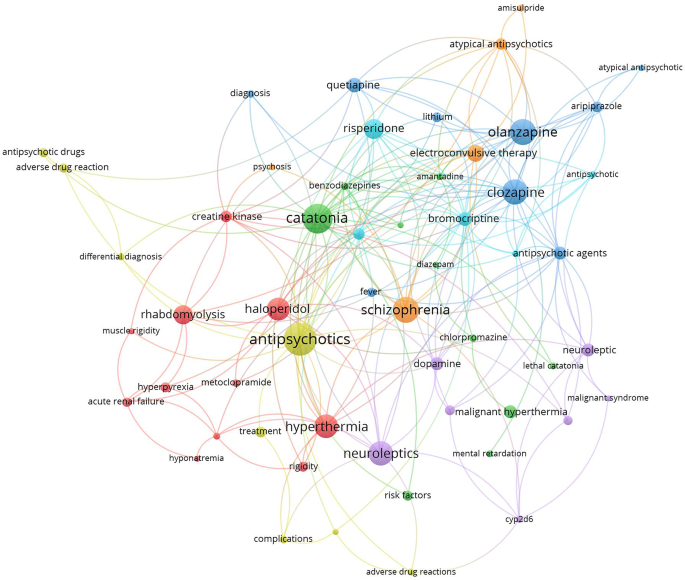

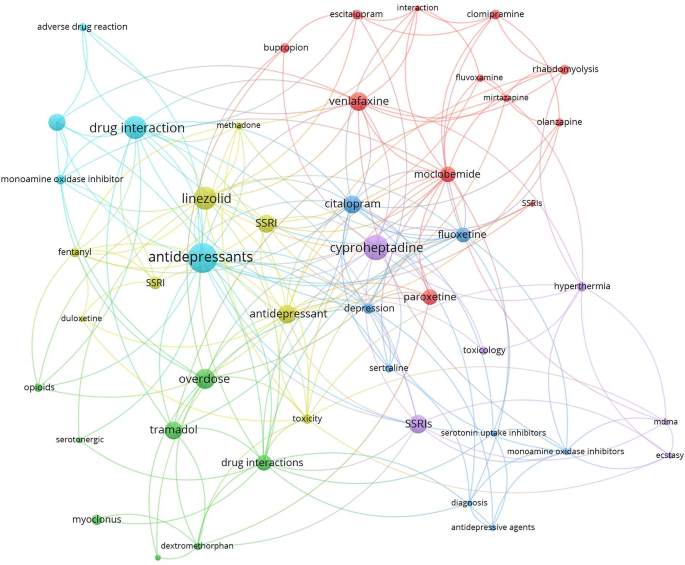

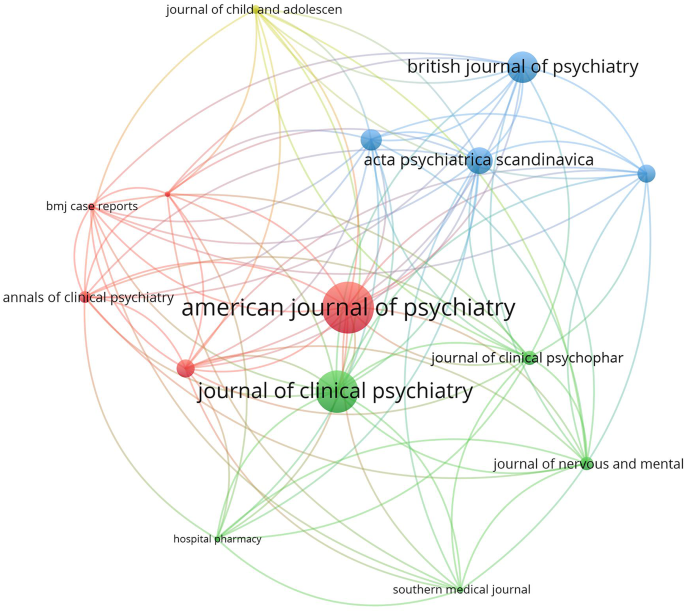

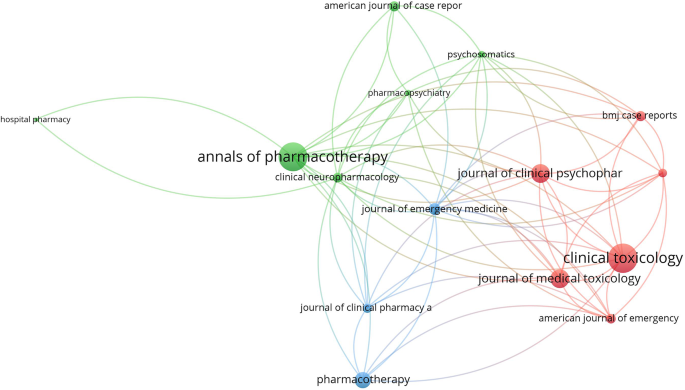

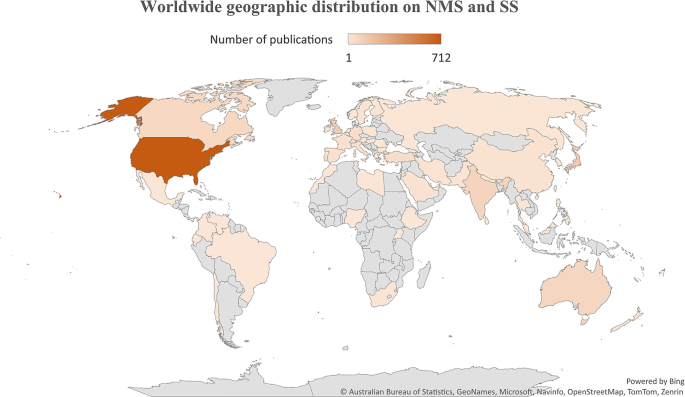

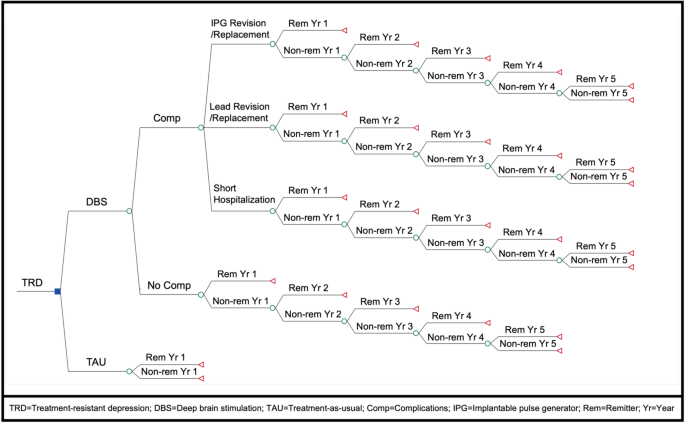

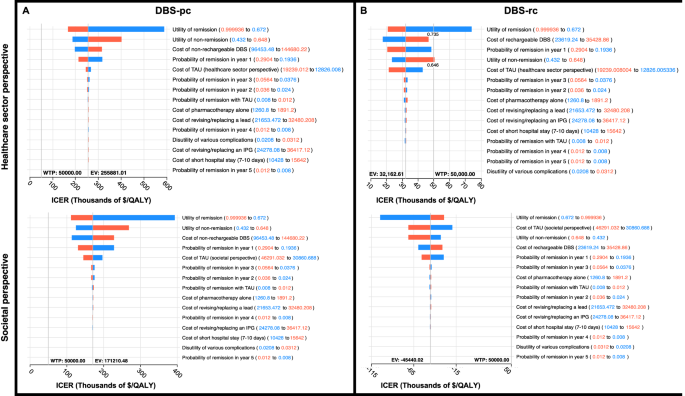

The search yielded 1150 articles on NMS and 587 on SS, with the majority being case reports. Growth patterns revealed a surge in NMS research between 1981 and 1991, while SS research increased notably between 1993 and 1997. Active countries and journals differed between NMS and SS, with psychiatry journals predominating for NMS and pharmacology/toxicology journals for SS. Authorship analysis indicated higher multi-authored articles for NMS. Top impactful articles focused on review articles and pathogenic mechanisms. Research hotspots included antipsychotics and catatonia for NMS, while SS highlighted drug interactions and specific medications like linezolid and tramadol.

Conclusions

NMS and SS represent rare but life-threatening conditions, requiring detailed clinical and scientific understanding. Differential diagnosis and management necessitate caution in prescribing medications affecting central serotonin or dopamine systems, with awareness of potential drug interactions. International diagnostic tools and genetic screening tests may aid in safe diagnosis and prevention. Reporting rare cases and utilizing bibliometric analysis enhance knowledge dissemination and research exploration in the field of rare drug-induced medical conditions.

Introduction

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) and serotonin syndrome (SS) are drug-induced, potentially life-threatening conditions that are infrequently encountered in medical practice, necessitating prompt intervention [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome is characterized by a decrease in dopamine activity in the brain, often associated with the use of dopamine antagonists, primarily neuroleptic or antipsychotic medications [ 5 , 6 ]. While the exact pathophysiology of NMS remains incompletely understood, it is believed to involve dopamine dysregulation in the basal ganglia and hypothalamus. This dysregulation, particularly the blockade of dopamine receptors, especially D2 receptors, leads to a state of dopamine deficiency, manifesting in symptoms such as muscle rigidity, hyperthermia, and autonomic instability. Furthermore, withdrawal from dopamine agonists, such as L-Dopa, can also precipitate NMS in susceptible individuals. Serotonin Syndrome is characterized by an excess of serotonin (5-HT) in the central nervous system, typically stemming from the use of serotonergic medications or substances that elevate serotonin levels [ 7 , 8 ]. These drugs encompass antidepressants, notably selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), opioids, specific psychedelics, serotonin agonists, and herbal supplements. The pathophysiology of SS revolves around the excessive stimulation of serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A receptors. This heightened stimulation precipitates a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from agitation, confusion, hyperthermia, muscle rigidity, to autonomic dysfunction. The severity of SS can vary widely, from mild manifestations to life-threatening conditions, contingent upon the extent of serotonin excess and individual susceptibility factors.

Both NMS and SS exhibit shared clinical manifestations, including hyperthermia, hypertension, hypersalivation, diaphoresis, and altered mental status [ 4 ], with instances of coexistence reported in some patients [ 9 ]. However, they diverge in their etiologies and clinical presentations. For instance, individuals with NMS typically display hyporeflexia, normal pupil size, and normal bowel sounds, contrasting with SS patients who often present with hyperreflexia, dilated pupils, and hyperactive bowel activity [ 10 ]. NMS is typified by lead-pipe muscle rigidity, whereas SS manifests with increased muscle tone, particularly in the lower extremities [ 11 , 12 ]. Given these distinctions, treatment strategies for NMS and SS diverge based on their underlying causes [ 2 ]. The mechanisms driving these syndromes differ significantly; while NMS involves diminished dopamine activity in the brain, SS is characterized by elevated serotonin levels [ 13 ]. Dopamine antagonists, such as neuroleptics or antipsychotics, are commonly implicated in NMS [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], although other triggers like withdrawal from dopamine agonists, like L-Dopa, can also induce NMS [ 17 , 18 ]. Conversely, SS can result from various drug classes, including antidepressants, opioids, psychedelics, serotonin agonists, and certain herbs [ 7 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Consequently, distinct medications are employed for their management; benzodiazepines and serotonin antagonists are standard therapy for SS, whereas dopaminergic agents and dantrolene are preferred for NMS [ 10 ]. While the incidence of NMS remains low, particularly among patients receiving newer generation antipsychotics [ 24 , 25 ], recent studies on SS incidence are lacking. However, a 1999 study reported an incidence of 0.4 cases per 1000 patient-months with nefazodone [ 26 ], while SS incidence reaches 14–16% in cases of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) overdose [ 27 ].

Research context and objectives

The landscape of psychiatric pharmacotherapy has evolved over time, witnessing a surge in the number of approved drugs and the introduction of novel classes into clinical practice [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. This trend is particularly notable in the treatment of depression and schizophrenia, where the absence of universally safe and effective drugs persists [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Additionally, off-label utilization of antidepressants and antipsychotics has been observed among patients with dementia and other neuro-cognitive disorders [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ], contributing to an upward trajectory in psychiatric drug consumption [ 42 , 43 ]. The risk of SS is linked to any medication or herb augmenting the central serotonergic pathway, necessitating vigilant monitoring by healthcare professionals due to the potential for adverse effects, whether as a primary mechanism or side effect [ 20 ]. A concerning trend of unsupported polypharmacy in psychiatric medications has also emerged [ 44 ], along with significant prescribing of antidepressants and antipsychotics to dementia patients without documented indications of depression or psychosis [ 45 , 46 ], mirroring similar trends among individuals with intellectual disabilities [ 47 ]. The escalating demand for psychiatric therapy raises apprehensions regarding the likelihood of adverse medication effects [ 48 ], exacerbated by increased prescribing rates, polypharmacy, and off-label usage, which heighten the incidence of drug-induced toxicities, including NMS and SS. Analyzing published literature on drug-induced NMS and SS provides valuable insights into these rare yet severe toxicities, aligning with the pressing global public health burden of depression, schizophrenia, and related conditions, accentuated by the fatal toxicities associated with specific psychiatric medications. This scientific literature on NMS and SS is ripe for analysis and mapping to delineate current research hotspots [ 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ], addressing the gap in the literature. Accordingly, the present study aims to analyze and map scientific research on NMS and SS published in prestigious, internationally indexed journals. Through this analysis, the study seeks to identify key topics, impactful articles, prominent journals, research output, growth patterns, hotspots, and leading countries in the field, providing valuable insights for scholars, medical students, and international funding agencies to discern research trajectories, bibliographic trends, and knowledge structures pertaining to NMS and SS. Ultimately, this endeavor aims to invigorate scholarly discourse and inform clinical practice in the field.

Database and keywords

In this study, we employed a systematic search strategy to extract relevant scientific literature on NMS and SS from the PubMed MeSH database. Specifically, we utilized the following keywords:

Malignant neuroleptic syndrome: “malignant neuroleptic syndrome”.

Serotonin syndrome: “serotonin syndrome” or “serotonin toxicity”.

To ensure comprehensive coverage, we conducted our search in Scopus, a prestigious scientific database owned by Elsevier, which has previously been utilized for analyzing research in psychiatry [ 56 , 57 ]. Scopus is renowned for its extensive coverage, encompassing a vast array of scholarly publications in the field. Notably, Scopus encompasses over 95% of the content included in other databases such as PubMed and Web of Science, rendering it an ideal platform for our study [ 58 ].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We restricted our search to articles published from 1950 to December 31st, 2022, and focused exclusively on journal research and review articles written in English. Excluded from our analysis were editorials, notes, letters, and conference abstracts. Additionally, articles pertaining to non-human subjects were excluded, ensuring the relevance of our findings. We meticulously reviewed the titles and abstracts of over 100 articles to eliminate irrelevant publications, such as those mentioning NMS or SS only marginally, thereby refining the scope of our analysis.

Our search strategy yielded results indicative of its validity, as evidenced by the prominent presence of leading scientists and journals in the fields of psychiatry and pharmacology. This reaffirmed the robustness of our search criteria and the relevance of the retrieved literature to our study objectives.

Data management, analysis, and mapping