An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Implementation of the Mental Capacity Act: a national observational study comparing resultant trends in place of death for older heart failure decedents with or without comorbid dementia

James m. beattie.

1 Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation, King’s College London, London, UK

2 School of Cardiovascular Medicine and Sciences, King’s College London, London, UK

Irene J. Higginson

Theresa a. mcdonagh, associated data.

Additional file 1 :Supplementary files S-1, S-2, S-3, and S-4 are available online.

Heart failure (HF) is increasingly prevalent in the growing elderly population and commonly associated with cognitive impairment. We compared trends in place of death (PoD) of HF patients with/without comorbid dementia around the implementation period of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA) in October 2007, this legislation supporting patient-centred decision making for those with reduced agency.

Analyses of death certification data for England between January 2001 and December 2018, describing the PoD and sociodemographic characteristics of all people ≥ 65 years registered with HF as the underlying cause of death, with/without a mention of comorbid dementia. We used modified Poisson regression with robust error variance to determine the prevalence ratio (PR) of the outcome in dying at home, in care homes or hospices compared to dying in hospital. Covariates included year of death, age, gender, marital status, comorbidity burden, index of multiple deprivation and urban/rural settings.

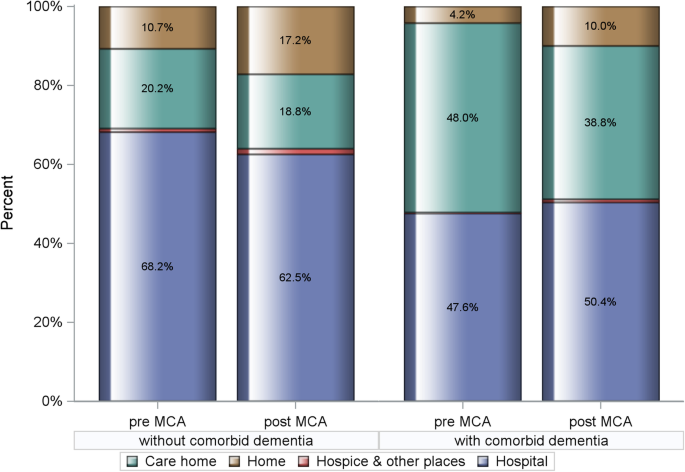

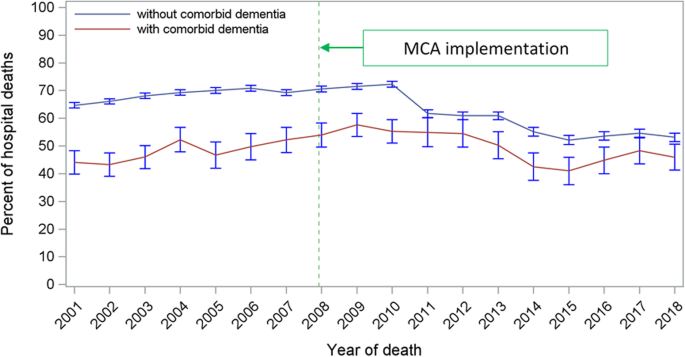

One hundred twenty thousand sixty-eight HF-related death records were included of which 8199 mentioned dementia as a contributory cause. The overall prevalence proportion of dementia was 6.8%, the trend significantly increasing from 5.6 to 8.0% pre- and post-MCA (Cochran-Armitage trend test p < 0.0001). Dementia was coded as unspecified (78.2%), Alzheimer’s disease (13.5%) and vascular (8.3%). Demented decedents were commonly older, female, and with more comorbidities. Pre-MCA, PoD for non-demented HF patients was hospital 68.2%, care homes 20.2% and 10.7% dying at home. Corresponding figures for those with comorbid dementia were 47.6%, 48.0% and 4.2%, respectively. Following MCA enforcement, PoD for those without dementia shifted from hospital to home, 62.5% and 17.2%, respectively; PR: 1.026 [95%CI: 1.024–1.029]. While home deaths also rose to 10.0% for those with dementia, with hospital deaths increasing to 50.4%, this trend was insignificant, PR: 1.001 [0.988–1.015]. Care home deaths reduced for all, with/without dementia, PR: 0.959 [0.949–0.969] and PR: 0.996 [0.993–0.998], respectively. Hospice as PoD was rare for both groups with no appreciable change over the study period.

Conclusions

Our analyses suggest the MCA did not materially affect the PoD of HF decedents with comorbid dementia, likely reflecting difficulties implementing this legislation in real-life clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-021-02210-2.

The incidence and prevalence of heart failure varies across the world reflecting regional differences in cardiovascular disease burden, ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. While the age-adjusted incidence and prevalence of heart failure may be declining in Westernised countries, absolute rates of these indices are increasing in parallel with societal ageing [ 1 ]. In the United Kingdom (UK), about 900,000 people are living with heart failure. The prevalence is 1–2% in the general population, rising to at least 10% in those ≥70 years of age [ 2 , 3 ]. The lifetime risk of developing heart failure is about 20% at 40 years, but for each age decile between 65 and 85 years, the incidence doubles for men and trebles for women [ 4 ].

Crafted by international consensus [ 5 ], a universal definition of heart failure has recently emerged as

…a clinical syndrome with symptoms and / or signs caused by a structural and / or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and / or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion.

Increasingly accurate diagnostic protocols have been established, and based on the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), the percentage volume of the diastolic blood pool ejected during systole, an updated classification system linked to the above definition has characterised four clinical phenotypes: heart failure with a reduced EF [< 40%] (HFrEF); heart failure with a mildly reduced EF [40–49%] (HFmrEF); heart failure with a preserved EF [≥50%] (HFpEF); and heart failure with an improved EF [baseline EF ≤40%, a ≥10% point increase from baseline EF, the improved EF > 40%] (HFimpEF) [ 5 ]. Advances in heart failure therapy, particularly those for HFrEF, have enabled some patients to live longer, more comfortable lives, but for many, heart failure remains a life-limiting condition, the 5- and 10-year case-fatality rates being about 50% and 75%, respectively, similar to outcomes for common cancers [ 3 , 6 ]. As well as being encumbered with an unpredictable disease trajectory, this burgeoning and increasingly elderly clinical cohort usually exhibit several comorbidities which add to the complexity and challenge the coordination required of their care [ 2 ].

Cognitive impairment, ranging from mild forms to severe as manifest in dementia, is relatively common, affecting between 25 and 70% of those with heart failure across a series of studies, and estimated at 40% overall in a meta-analysis [ 7 – 9 ]. Disordered cognition is heterogeneous and demonstrable across a range of higher cortical domains including attention, memory, speech and language processing, learning and executive function [ 10 ], such deficits beyond those arising from normative ageing of the brain. Cognitive impairment may be transitory, sometimes occurring as delirium in patients presenting with acute heart failure [ 11 ], but often presents as a long-term progressive condition, more frequently encountered in older people with chronic heart failure compared to their age-matched healthy counterparts [ 12 ]. The impact of these persistent features tends to fluctuate over time, but even when mild, may impact heart failure patients’ self-care behaviours and treatment adherence resulting in greater rates of hospital admission and mortality [ 13 , 14 ]. There appears to be no direct correlation between the severity of these two conditions [ 15 ], but dilemmas may arise when treating cognitively impaired heart failure patients, sometimes relating to the continued efficacy of established treatment modalities, ceilings of care, and resuscitation issues [ 16 ]. These confront not only professional healthcare providers but also their informal carers, usually family members, who take responsibility for much day-to-day practical support. In assisting those affected by dementia-related loss of intellectual capacity, such carers may be called upon to act as decisional proxies and offer insight into patients previously voiced values and preferences for treatment.

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) of 2005, applicable to residents in England and Wales aged ≥16 years, sets out a statutory framework to foster person-centred decision making and advance care planning for those who may lack capacity due to a lifelong learning disability, or as a consequence of the transient or permanent effects of acute or long-term illnesses [ 17 ]. For people with cognitive impairment and a progressive, ultimately fatal condition such as heart failure, the MCA may be particularly important in fulfilling goals of care close to the end of life. Achieving care in appropriate settings and the preferred place of death (PoD) are generally accepted as benchmarks of good quality end-of-life care, death at home or customary place of residence usually regarded as the desired option [ 18 ]. Given the relatively frequent association of cognitive impairment with heart failure, it might be expected that the decision-making processes legally constituted within the MCA would drive changes in the final place of care and death during the terminal phase of this condition. The code of practice setting out the standards required to comply with the MCA came fully into force on October 1, 2007 [ 19 ]. Thus, we undertook a comparative trend analysis covering the period of implementation of this legislation to discern any resultant variation in the PoD of heart failure decedents rendered vulnerable by comorbid dementia.

Application of the Mental Capacity Act

As outlined above, the MCA and associated code of practice offer legislative protection to promote patient empowerment and safeguard their autonomy. Prepared when mental capacity is intact, patients may formulate an advance decision such as one to refuse life-sustaining treatment or, if ≥18 years, appoint a close person as a personal welfare lasting power of attorney (LPA) to undertake decisions on their behalf if agency is later lost. Thereafter, any clinical treatment protocol, where possible, should be in accordance with their previously documented choices and values, or these as expressed through their nominated personal welfare LPA. For the purposes of the Act, a two-stage capacity test is applicable. To qualify through Stage 1, the individual must exhibit a demonstrable functional impairment of the mind or brain. For Stage 2, capacity is deemed to be lost if they lack the ability to fulfil any of the following: (a) understand the information pertinent to the decision, (b) retain the information, (c) deliberate on that information as part of the decision-making process and (d) communicate their decision by any means possible. In the context of the study, we must emphasise that many people diagnosed with dementia can still make decisions about many aspects of their care, and loss of capacity should not be regarded as an all-or-none phenomenon based on that diagnostic label. Indeed, under the terms of the MCA, retention of capacity is assumed, and capacity is both decision and time specific.

Study design

This was a national population-based observational study examining anonymised individual-level death registration data collated by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) from 2001 to 2018, provided to us under license, and relating to heart failure decedents resident in England.

Data source and study cohort

In the UK, the death certificate is completed by the responsible clinician, civil registration of the cause of death by a relative or another qualified informant being legally required within 5 days of medical certification. Sometimes a coroner assumes this role after a post-mortem examination or inquest. Following transcription of the information on the death certificate by the recording registrar, this is digitised and uploaded to the ONS for subsequent diagnostic coding in accordance with the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). This study dataset comprised all deaths registered in England from January 2001 through December 2018 of people aged ≥ 65 years for whom heart failure was recorded as the underlying cause of death. We elected to study those aged ≥ 65 years at death a priori, perceiving this subset to include the vast majority of heart failure decedents with or without dementia as a marker of cognitive impairment. Heart failure as the primary cause of death was determined by the allocation of any ICD-10: I50 code by the ONS. Designation of diminished intellectual capacity for this cohort was determined when dementia of any aetiology was mentioned as a contributory cause of death. The presence of comorbid dementia was indicated by the application of ICD-10 codes G30 [Alzheimer’s disease]; F00 [dementia in Alzheimer’s disease with late onset, atypical or mixed type, and unspecified]; F01 [vascular dementia]; F02 [dementia in other diseases classified elsewhere]; or F03 [unspecified dementia]. ONS death data acquisition and coding processes are subject to regular quality assurance. Pertinent to this study period, it should be noted that in 2011 there was a change in ONS mortality data coding practice, the previous coding of unspecified cerebrovascular disease when registered as a contributory cause of death being reclassified as vascular dementia [ 20 ].

The outcome variable was PoD as recorded on death certificates and codified by the ONS. Characterisation of PoD for this study was based on the classification system defined by the National End of Life Care Intelligence Network, part of Public Health England [ 21 ]. This specifies 5 groupings of PoD: (a) Hospital, which incorporates all acute, specialist, and community hospitals whether they be National Health Service (NHS) or private, but not psychiatric hospitals; (b) Care home, including residential and nursing homes; (c) Own residence, the decedent’s usual place of abode, but excludes communal living arrangements such as convents, monasteries, hostels or prisons; (d) Hospice, commonly standalone NHS or independent establishments; (e) Other places, covering psychiatric hospitals, other people’s homes, communal living institutions as described above, workplaces, public spaces or roads. This grouping also applies to those declared dead on arrival at hospital, potentially relevant to some heart failure patients who succumb to sudden death. Where the PoD was unknown or unspecified, these data were incorporated in descriptive statistics but not considered further in multiple adjusted analyses.

Period of death as the independent variable of interest incorporated a binary indicator for the year of death pre- and post-enforcement of the MCA [0: 2001–2007; 1: 2008–2018]. Covariates included age at death, number of mentioned contributory causes, gender, marital status, socioeconomic position as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation, and categorisation of the location of decedents’ usual residence as urban or rural based on the relevant postcode as archived on the ONS classification system [ 22 , 23 ].

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were described using count (percentages) and means (standard deviation [SD]) as appropriate. The proportion of hospital deaths among heart failure decedents with or without comorbid dementia and the number of patients who died from heart failure with comorbid dementia were plotted to visually determine temporal trends, the latter also assessed statistically using a two-tailed Cochran-Armitage trend test.

We used modified Poisson regression with robust error variance [ 24 ] to evaluate the independent association between enforcement of the MCA and PoD. Three models were constructed separately for heart failure patients who died with or without comorbid dementia: home (1) versus hospital (0); care home (1) versus hospital (0); hospice (1) versus hospital (0). All covariates were forced to stay in the models to control their effects. The prevalence ratio (PR) was derived from the respective model to quantify the magnitude of association.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To control for Type 1 error, we applied Bonferroni correction to the alpha level. A two-sided p value of 0.008 (0.05/6) was considered statistically significant.

Study sample

Between 2001 and 2018, 120,068 people aged ≥65 years whose deaths were registered as directly due to heart failure were identified, their data subsequently included in this analysis. Table Table1 1 describes the characteristics of these heart failure decedents. Overall, 8199 (6.8% [confidence intervals (CI) 6.7 to 7.0]) of these registrations were documented with dementia as a contributory cause, this being classified as unspecified dementia in 78.2%, Alzheimer’s disease in 13.5%, and as vascular dementia in 8.3%. No other dementia subtypes were denoted. For the periods 2001–2007 and 2008–2018, pre- and post-enforcement of the MCA, the numbers of heart failure decedents with dementia were 3427 (5.6%) and 4772 (8.0%) respectively. The prevalence proportion of dementia gradually increased on an annual basis, this trend being statistically significant ( Z =18.87, p < 0.0001) as shown on Fig. Fig.1. 1 . There was no discernible artefactual change in the general rate of dementia mentioned as a contributory cause of death associated with the 2011 change in ONS coding practice. However, as shown in Table Table2, 2 , there was a contemporaneous and statistically significant reduction ( p < 0.0001) in the coding of ‘ unspecified dementia ’ with an equivalent increase in coding for ‘ vascular dementia ’.

Characteristics of heart failure decedents with or without comorbid dementia, n (column %), England 2001–2018

| Variable | Value | With dementia | Without dementia |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | All | 8199 (6.8) | 111,869 (93.2) |

| Age at death (years) | 65–74 | 207 (2.5) | 9293 (8.3) |

| 75–84 | 2082 (25.5) | 33,920 (29.9) | |

| 85+ | 5910 (72.0) | 68,656 (61.8) | |

| Gender | Female | 5498 (67.2) | 67,474 (60.0) |

| Male | 2701 (32.8) | 44,395 (40.0) | |

| Marital status | Divorced | 1945 (23.7) | 30,118 (27.1) |

| Single | 365 (4.4) | 5343 (4.9) | |

| Widowed | 553 (6.8) | 8481 (7.5) | |

| Married | 5309 (64.8) | 67,497 (60.1) | |

| Unknown | 27 (0.3) | 430 (0.4) | |

| Year of death | 2001–2007 | 3427 (87.2) | 57,240 (88.5) |

| 2008–2018 | 4772 (56.4) | 54,629 (55.7) | |

| No. comorbidities | 0 | -- | 15,139 (13.4) |

| 1 | 1595 (19.4) | 44,661 (39.3) | |

| 2 | 3474 (42.5) | 31,048 (27.9) | |

| 3 | 1922 (23.4) | 13,750 (12.6) | |

| 4+ | 1208 (14.6) | 7271 (6.8) | |

| Deprivation* | Most deprived | 1445 (17.7) | 20,352 (18.1) |

| 2 | 1685 (20.5) | 22,250 (19.8) | |

| 3 | 1836 (22.4) | 24,227 (21.7) | |

| 4 | 1748 (21.3) | 23,918 (21.4) | |

| 5 | 1485 (18.1) | 21,122 (19.0) | |

| Rural/urban indicator* | Urban | 6653 (81.1) | 89,986 (80.4) |

| Rural | 1546 (18.9) | 21,883 (19.6) | |

| Place of death | Hospital | 4033 (49.2) | 73,177 (64.9) |

| Care home | 3497 (42.8) | 21,850 (19.5) | |

| Home | 623 (7.5) | 15,541 (14.4) | |

| Hospice | 22 (0.3) | 606 (0.6) | |

| Other places | 24 (0.3) | 695 (0.6) |

* p values for the difference between the two groups = 0.12. For all other inter-group comparisons, p < 0.0001

Percentages of heart failure decedents ( n =120,068) with comorbid dementia ( n =8199) by year of death, England, 2001–2018

Distribution of dementia subtypes [ n (%)] following the ONS change in dementia coding practice of 2011

| Coding | Pre- coding change | Post-coding change | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 642 (12.8) | 465 (14.6) | 1107 (13.5) | |

| 4287 (85.5) | 2128 (66.8) | 6415 (78.2) | |

| 84 (1.7) | 593 (18.6) | 677 (8.3) | |

| 5013 (61.1) | 3186 (38.9) | 8199 (100) |

AD Alzheimer’s disease, UD unspecified dementia, VD vascular dementia

The p values for comparison of the proportions of UD and VD pre- and post-coding change were statistically significant ( p < 0.0001)

Most heart failure decedents were ≥85 years old at the time of death (62.1%). The mean age at death increased between the two study periods (2001–2007: 85.7 years [SD 7.4]; 2008–2018: 86.6 years [SD 7.5], the age at death being greater for those with dementia for both intervals at 87.1 [SD 6.2] and 88.1 years [SD 6.0], respectively. A relatively higher level of multimorbidity was noted for heart failure decedents with dementia. Most of those dying from heart failure were female, this proportionately greater at 67.2% for the dementia group compared to 60.0% for those without dementia. Across the totality of heart failure decedents, there was no significant difference in marital status between those with or without dementia, Most heart failure patients lived and died in urban environments and deprivation quintiles were similar for both study populations.

Trends in place of death

Over the period of implementation of the MCA, comparative outcomes in PoD for these heart failure decedents are shown in Fig. Fig.2. 2 . For the period 2001–2007, hospital was the most common PoD for the non-demented heart failure group at 68.2%, 20.2% dying in a care home, and 10.7% dying at home. This changed a little for the latter period 2008–2018, reducing to 62.5% and 18.8% for hospital and care homes respectively, the proportion of home deaths increasing to 17.2%. In contrast, for heart failure decedents with dementia, there was a small increase in the proportion of hospital deaths, this rising from 47.6 to 50.4%. For this group, there was a reduction in care home deaths from 48.0 to 38.8%, with a modest rise in home deaths, 4.2% to 10.0%. Hospice as the PoD was rare for both clinical cohorts and declined over the study period. The time trend in hospital deaths is shown in Fig. Fig.3. 3 . There was a statistically significant reduction in hospital deaths for heart failure decedents without dementia ( p < 0.001). On the other hand, the marginal increase in hospital deaths for those with dementia was not significant ( p =0.97). Adjusted PRs following implementation of the MCA confirm increased PoD at home compared to hospital for non-dementia patients, PR: 1.026 [CI: 1.024–1.029] ( p < 0.0001), this trend not significant for those with dementia, PR: 1.001 [CI 0.988–1.015] ( p =0.83). Care home deaths reduced for both groups, PR: 0.959 [CI 0.949–0.969] ( p < 0.0001), and PR: 0.995 [CI 0.993–0.998] ( p < 0.0001) for those with and without dementia, respectively. Starting from an already small base, adjusted PRs for hospice rather than hospital as PoD declined significantly for both non-demented and demented heart failure decedents being 0.979 [CI 0.977–0.980 ( p < 0.0001) and 0.946 [CI 0.934–0.959] ( p < 0.0001), respectively. A summary of the adjusted PRs for dying in a premise other than hospital following MCA enforcement is shown in Table Table3. 3 . Fully detailed results for all three model sets are available in Additional file 1 : Supplementary Tables S-2 to S-4.

Comparative outcomes (%) in place of death for heart failure decedents with and without comorbid dementia pre- (2001–2007) and post- (2008–2018) implementation of the Mental Capacity Act (MCA). Chi-square test p value < 0.0001

The time trend of hospital deaths among patients who died from heart failure with or without comorbid dementia, England 2001–2018

The adjusted prevalence ratios* (95% confidence intervals) of dying in a specific type of premise (compared to a hospital death) after implementation of MCA in heart failure decedents with or without comorbid dementia, England 2001–2018

| With dementia | Without dementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | 1.001 (0.988 to 1.015) | =0.83 | 1.026 (1.024 to 1.029) | < 0.0001 |

| Care home | 0.959 (0.949 to 0.969) | < 0.0001 | 0.995 (0.993 to 0.998) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospice | 0.946 (0.934 to 0.959) | < 0.0001 | 0.979 (0.977 to 0.980) | < 0.0001 |

Hospital (Reference) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

*> 1 indicates a higher chance of death in the corresponding type of premise

In this first national study examining variation in the PoD for heart failure patients over the period of enactment and implementation of the MCA in England, our results suggest that the decision-making and advance care planning processes enshrined in this legislation had little material effect on the ultimate site of care provision determining PoD for those with cognitive impairment manifest as dementia. In the later years of this study period when the code of practice for this legislation was operational, trend data for heart failure decedents certified with comorbid dementia show a modest rise in hospital deaths with fewer care home deaths. Conversely, for this study phase, there was a small reduction in hospital deaths for those without dementia who were younger and with fewer comorbidities.

The reasons behind the apparent lack of impact of this legislation may be complex, but it has been proposed that the MCA is relatively poorly applied in clinical practice. While a variety of training models have been developed to disseminate information to health professionals on the five principles underpinning these regulations, recent reviews suggest poor understanding of when and how the provisions of the Act should be employed, with the need for clarity on the process of designating the role of surrogate decision-makers to properly ensure patients’ best interests are maintained [ 25 – 27 ]. A lack of confidence of those working in acute care settings has been particularly highlighted, specifically citing decision-making with respect to hospital discharge [ 28 ]. This issue may be especially relevant to our study observations given that we have demonstrated that the majority of those dying with heart failure in England do so in hospital, similar data emerging from the United States (US) [ 29 ].

At variance with the trends evident in this study, previous work has suggested a decline in the frequency of hospital deaths for those with dementia in recent years, with more people dying in care homes [ 30 ]. These findings were also based on ONS death certification data but included all individuals for whom dementia was mentioned as either the underlying or as a contributory cause of death. In contrast, the current study specifies heart failure as the primary cause of death, differentiating the comparator groups by the presence or absence of dementia mentioned only as a contributory cause. It is well established that the principal diagnosis is the main determinant of the site of clinical care [ 31 ], and community-based primary care practitioners appear to be relatively incognizant of patients’ preferences for place of care or PoD, particularly when dealing with non-cancer diagnoses [ 32 ]. Unless policies for comfort care are clearly outlined, should people with chronic heart failure living at home or in a nursing home suddenly deteriorate, the reactive response of professional staff may be to arrange emergency hospital admission by default. However, we have no information on any care transitions prior to the terminal phase for this study cohort, or whether this possible course of action had a bearing on the results of this study.

The completeness of death certification in the UK is regarded as relatively robust with proportionately fewer ‘ garbage codes ’ than data from many other countries [ 33 ]. However, dementia as recorded on death certification likely underestimates the true prevalence, and it has been suggested that studies using death certification alone may fail to account for 16-18% of dementia cases [ 34 ]. A variety of factors may influence such documentation. Rates of inclusion of dementia are generally increased in those who die in institutions such as care homes compared to those dying at home, particularly if dementia is at the severe end of the clinical spectrum and includes agitation [ 35 ]. While heart failure guidelines draw attention to cognitive impairment as a comorbidity, describing all grades of this by hospital-based clinicians is reportedly poor [ 14 ], and there are diverging views on whether dying in hospital positively or negatively affects the rate of recording of dementia at the time of death certification [ 35 , 36 ]. Recent initiatives to heighten clinicians’ awareness of dementia may improve matters. In 2012, NHS England introduced a quality improvement scheme through the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payment framework [ 37 ]. Acute healthcare providers were incentivised with the assurance of increased remuneration if 90% of all patients aged ≥75 years and whose emergency hospital admission lasted > 72 h were screened for dementia. Further financial gain was available if those patients whose initial assessment indicated dementia or was inconclusive were referred on for specialist review. While this dementia assessment and referral exercise was retired as a CQUIN indicator in April 2016, these conditions have been retained within the standard contract for English hospitals providing acute clinical services. It is possible that these administrative processes may have contributed in some measure to the increased mentions of dementia as certified for hospital decedents evident in the latter course of this study.

The relatively frequent concurrence of cognitive impairment and heart failure likely stems from various pathophysiologic features related to the latter condition combined with shared cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia or dysglycaemia [ 7 , 38 , 39 ]. The haemodynamic and risk factor profiles for HFrEF and HFpEF clearly differ, but very few investigations have compared the spectrum of cognitive impairment across the range of ejection fraction phenotypes. There is a suggestion that affected domains of cognitive function may vary, but data is limited with inconsistent results [ 40 , 41 ].

To date, there is no evidence that evidence-based guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for heart failure drives neurocognitive dysfunction [ 42 ], and indeed it has been posited that centrally acting angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) such as perindopril or captopril, which cross the blood-brain barrier, may slow the progression of cognitive impairment in those with dementia [ 43 ]. Following the positive results of the PARADIGM-HF study demonstrating the benefits of sacubitril/valsartan, the first of a new class of drugs termed ARNIs (angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors) [ 44 ], this therapeutic option for HFrEF has been widely adopted. Neprilysin is a soluble metalloprotease which catalyses the degradation of natriuretic peptides (NPs), downregulation of this enzymatic activity likely increasing endogenous NP mediated natriuresis and vasodilation. However, such neprilysin inhibition might also interfere with the clearance of amyloid-β protein, vascular deposition of which results in cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a distinctive feature of Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia-related adverse events were not overrepresented through 4.3 years follow-up of the relevant PARADIGM-HF study arm compared to similar populations [ 45 ]. Nonetheless, as required by the Food and Drug Administration in the US, this potential hazard is currently being evaluated in the PERSPECTIVE study ( ClinicalTrials.gov ID {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02884206","term_id":"NCT02884206"}} NCT02884206 ). Due to report in 2022, this trial includes a battery of neurocognitive testing and sequential 18 F-labelled florbetaben positron emission tomography to assess any longitudinal changes in cerebral amyloid plaque burden. Importantly, recent evidence shows that the hearts of some patients with Alzheimer’s disease exhibit diastolic dysfunction and thickening of the interventricular septum. These features are characteristic of cardiac amyloidosis suggesting that in some individuals, amyloid-β protein may also accumulate in tissues other than the brain [ 46 ].

As inferred above, in recent years GDMT for those affected by heart failure has become increasingly effective [ 47 ], but heart failure is an ambulatory care sensitive condition and remains the commonest cause of acute hospitalisation in those > 65 years [ 48 ]. Following an index heart failure admission in England, the 1-year mortality for patients discharged alive is 39.6% with a 30-day all-cause readmission rate of 19.8% [ 49 ]. Readmissions for heart failure tend to follow a tri-phasic pattern. This was apparent in a study of 8543 heart failure patients in Toronto monitored for 10 years following their first hospital admission, by which time 98.8% had died, the median survival after heart failure diagnosis being 1.75 years [ 50 ]. About 30% of all readmissions occurred within 2-months of initial hospital discharge, 50% during the 2-month period leading up to death, with 15-20% taking place in the intervening ‘ plateau phase ’ of the heart failure disease trajectories. A sentinel clustering of admissions in the terminal phase of heart failure has been well described [ 51 ]. It is uncertain if the presence of dementia as a comorbidity influences the readmission rate. Rao and colleagues followed 10,317 patients for 5 years subsequent to their diagnosis with heart failure between April 2008 and March 2009 using the primary care-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink combined with Hospital Episode Statistics and ONS death registration data [ 52 ]. Their analysis indicated that comorbid dementia was a factor significantly affecting emergency hospital readmissions in only 3 of 8 regions across England.

Comparable to the epidemiological trends for heart failure, the age-adjusted prevalence and incidence of dementia may also be declining in high-income countries. The Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Studies (CFAS 1 and II) of populations living in rural Cambridgeshire and the urban environments of Newcastle and Nottingham demonstrated a 24% reduction in the prevalence of dementia in those ≥65 years between 1989 and 2011 [ 53 ]. Consistent with our observations, the CFAS studies also suggested that women were more commonly affected, and while the prevalence of dementia in care home residents had increased from 56 to 70%, most people with dementia were still living at home. Similarly, dementia events have been continuously surveyed in the US-based Framingham Heart Study since 1975. Monitoring of this community cohort living in Massachusetts, predominantly of white European ancestry, has implied a 20% stepwise decline in the incidence of dementia each decade over the last 30 years [ 54 ]. The background to these cumulative decrements remains to be determined, but both the CFAS and Framingham study groups cited potential mechanisms in higher early educational attainment and attenuated vascular morbidity.

The Framingham Heart Study showed a non-significant reduction in Alzheimer’s disease with a more overt decrease in vascular dementia. In Westernised societies, Alzheimer’s is the most commonly encountered manifestation of dementia, but as an isolated pathophysiological process, this affects < 20% of those with heart failure. Rather, vascular dementia has been proposed as the likeliest associated variant, followed by mixed forms, then Alzheimer’s and other specific dementias [ 39 ]. This is at odds with the distribution of dementia subtypes noted in this study where unspecified dementia was most frequently mentioned on death certificates and coded as the dominant category. A similar finding was described in a Danish study of 324,418 patients admitted with incident heart failure and tracked for 35 years against an age- and sex-matched population without heart failure selected from the Danish Civil Registration System [ 55 ]. Adelborg and colleagues found a clear association between all-cause dementia and heart failure. This was relatively weak for Alzheimer’s disease, and while the vascular variant was represented, this was predominantly determined by the reported development of unspecified dementia. These authors proposed that some patients ostensibly exhibiting unspecified dementia may have been misclassified. However, in combining death certification data from sequential CFAS studies in England, all mentions of dementia as the underlying or a contributory cause of death showed a percentage distribution of subtypes of unspecified dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia as 69.3%, 21.6% and 8.6%, respectively [ 37 ]. These results are very similar to those noted in the current study and suggest that this proportional distribution of dementia variants is not specific to the heart failure population.

Advance care planning offers patients the potential to receive medical treatment consistent with their expressed preferences, values, and goals of care against the possibility of subsequent loss of decision-making capacity. This may help prevent needless hospital admissions and better achieve consensus on appropriate ceilings of care, avoiding exposure of patients and families to the distressing harms which sometimes accompany futile treatment escalation and burdensome invasive interventions close to the end of life. It is notable that a recent audit of end-of-life care in hospitals in England demonstrated that10% of heart failure patients were receiving mechanical ventilatory support within 24 h of death [ 56 ].

Given the unpredictability intrinsic to the heart failure disease trajectory which challenges individual prognostication even in the late stages of this disease, and the associated multimorbidity including cognitive impairment, it might be expected that advance care planning would be central to the care of people with this condition. However, advance care planning is not routinely incorporated within heart failure care and tends to be limited to the possible withdrawal of any implanted electronic or mechanical devices, or sometimes offered as one component of the still uncommon provision of palliative care [ 57 , 58 ]. A review and meta-analysis of 14 randomised controlled trials of advance care planning in heart failure, mostly US-based and involving 2924 individuals across a range of care structures, showed this to moderately improve the primary outcome measure in patients’ quality of life, together with similarly weighted favourable effects on secondary outcomes including communication about, and satisfaction with, end-of-life care [ 59 ].

Advance care planning for dementia was featured as a specific domain in the European Association of Palliative Care white paper on this condition [ 60 ], and the challenges taking this forward have been comprehensively reviewed [ 61 , 62 ]. Emerging themes suggest that while there is some disparity in the readiness of older people to engage in advance care planning, and the means to take this forward may also vary across the spectrum of healthcare delivery, the use of these instruments may be effective in promoting shared decision-making between patients, informal carers and professionals [ 63 ]. However, it should be noted that, in the UK, an advance care plan is not legally binding but merely an advisory statement of preferences and wishes in relation to general care and medical therapy [ 64 ].

Dialogue between the patient, family and clinician is basic to shared decision-making. However, triangulation of information between this triad does not necessarily mean equitably weighted opinions, and at times patients’ voices are marginalised, a dyadic interchange conducted between clinicians and family members. Such a discourse may be justified if the patient cannot physically contribute to meaningful shared decision-making, if capacity is deemed to be lost, legally binding instruments are not in place, and their preferences are unknown. Then, the opinion of the closest relative should be sought, their views respected and used to inform a care plan constructed in the best interests of the patient. However, it should also be remembered that the involvement of relatives as decisional proxies may be emotionally demanding, particularly if they are already distressed and experiencing anticipatory grief. Further, the assumption that there is always congruence between the opinions of family surrogate decision-makers and those perceived of patients is flawed. Rather, these are often misaligned, with at best moderate concordance between dementia/carer dyads when assessed within a hospital setting [ 65 ]. Qualitative studies examining difficulties in decision making during clinical encounters for those with dementia have cited tension between family members and conflicts between families and health professionals, some of the latter reluctant to undertake decisions on patients unfamiliar to them, particularly when there is poor information exchange following transfer from another care setting [ 66 ]. Even if decisional consensus is achieved, the discharge of hospital inpatients home may be subject to practical limitations depending on the social context. The caregiver burdens associated with heart failure and dementia have been well characterised. Informal caregivers may be unwilling or unable to reframe or enhance their roles, and it should be noted that the cohabitees of people living and dying with dementia tend to be of a similar advanced age [ 67 ]. Further, it has been proposed that there may be a gendering issue relating to care at home in that older women are more likely to have outlived their male partners and be devoid of spousal support [ 68 ]. However, in this study, the marital status of heart failure decedents with or without dementia appeared to be similar. Following the implementation of the MCA, our analysis suggests that proportionately more women with dementia died at home compared to those without dementia. The reason for this disparity is unclear, and a variety of other intersectional stressors which might constrain the social capital of older women close to the end of life may have been in play [ 69 , 70 ].

Strengths and weaknesses

To our knowledge, this is the first empirical study to systematically examine national data for England describing the PoD of people dying of heart failure with dementia documented as a contributory cause of death. A major strength is that our work is based on comprehensive data collated from the gamut of clinical practice over an 18-year period, but we acknowledge that we are dependent on the clinicians responsible for these heart failure decedents having made the correct diagnoses and accurately completing later death certification, over which there is no means of independent adjudication. Irrespective of the PoD, we have no access to information on the underlying aetiologies of heart failure, or the proportional distribution of resultant ejection fraction variants. Similarly, it is not possible to ascertain the duration of heart failure or nature of any care provision prior to the terminal phase, and whether this fatal outcome related to incident acute heart failure, worsening of chronic heart failure, or heart failure-related sudden cardiac death. It has been suggested that decisions to include dementia on death certificates rely on medical staff regarding this as clinically significant [ 71 ]. This is considered more likely if dementia is relatively severe, reaffirming our judgement in using the certified mention of dementia as a contributory cause of death to represent a valid marker of significant cognitive dysfunction, and therefore relevant to the aegis of the MCA. Regarding generalisability, the results of this study are germane to similar clinical populations, models of care delivery, and legal constructs. While the legal status of the MCA 2005 applies to England and Wales, beyond this jurisdiction but within the UK, this legislation is closely aligned to the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, and the Mental Capacity Act (Northern Ireland) 2016. There is also some global resonance through Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) of 2006. While the pertinence of specific aspects of the CRPD have been subject to legal argument [ 72 ], both this and the MCA have informed the development of mental capacity policies and legislation in Canada, Australia, and New Zealand [ 73 , 74 ].

In this hypothesis-generating study, we have investigated the impact of the MCA on the PoD of heart failure decedents aged ≥65 years resident in England whom we have shown to be increasingly affected by comorbid dementia, dying at home or usual place of residence customarily accepted as the preferred option. Our analyses of trends over the period of enactment and implementation of the code of practice relating to this legislation show little to suggest any significant influence on PoD for this relatively vulnerable clinical cohort. The background to this somewhat neutral outcome is multifaceted, administration of the Act clearly challenging for a prognostically ambiguous population subject to flux in the often-nuanced scenarios typical of real-life clinical practice, a milieu dominated by the treatment imperative. Further, even if the precepts of the MCA are correctly applied, this course of action may be ineffectual in isolation. Recent evidence suggests that achieving a good death at home requires patients and their informal carers to feel secure in that setting, effected by the provision of a 24/7 responsive palliative care service, staffed by those competent in symptom relief and with good communication skills [ 75 ]. Fulfilling the preferred PoD of those with heart failure and dementia might be better achieved by embedding application of the MCA within a system of anticipatory sympathetic clinical navigation across all care sectors, contingent upon effective upskilling of the relevant professionals, with good inter-agency and multidisciplinary collaboration to support and maintain appropriately configured community-based palliative care.

Acknowledgements

The GUIDE_Care Services project (NIHR HS&DR: 14/19/22 ) and The GUIDE_Care project (NIHR HS&DR: 09/2000/58).

Pre-publication history

Presented in part at the 7th International Advance Care Planning Conference, Rotterdam, 2019.

Abbreviations

| ACEI | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ARNI | Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor |

| CFAS | Cognitive Function and Ageing Study |

| CQUIN | Commissioning for Quality and Innovation |

| EF | Ejection fraction |

| GDMT | Guideline directed medical therapy |

| HF | Heart failure |

| HFimpEF | Heart Failure with improved Ejection Fraction |

| HFmrEF | Heart Failure with mildly reduced Ejection Fraction |

| HFpEF | Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HFrEF | Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Diseases 10 Revision |

| ID | Identifier |

| LPA | Lasting Power of Attorney |

| MCA | Mental Capacity Act |

| NHS | National Health Service |

| NP | Natriuretic peptide |

| ONS | Office for National Statistics |

| PoD | Place of death |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| US | United States |

Authors’ contributions

JMB: conception and design; organisation of the conduct of the study; interpretation of results; primary drafting and revision of the manuscript.

IJH and TAMcD: interpretation of the results; critical review and revision of the manuscript.

WG: conception and design; organisation of the conduct of the study; data acquisition and management; statistical analysis of the data; interpretation of results; drafting and revision of the manuscript. WG is guarantor of the data.

All authors approved the final version of the paper prior to submission.

Wei Gao and Irene J Higginson at King’s College London are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration South London (NIHR ARC South London) at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. These funding bodies had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

In accordance with General Data Protection Regulations arising from the UK Data Protection Act (2018), as all patient level data was fully anonymised, no ethical approval was required. Wei Gao is accredited to analyse this data through the ONS Approved Researcher Scheme.

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Challenges and expectations of the Mental Capacity Act 2005: an interview-based study of community-based specialist nurses working in dementia care

Affiliation.

- 1 Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King's College London, London, UK.

- PMID: 22098493

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03912.x

Aims: This study aimed to explore experiences of specialist community nurses providing information about the Mental Capacity Act and supporting people with dementia and carers.

Background: The role of specialist community nurses and case managers, such as Admiral Nurses, suggests that providing information about the recent Mental Capacity Act (2005) in England and Wales would be appreciated by people with dementia and carers and would assist in assessment and support.

Design: In-depth qualitative methodology was adopted to explore experiences and opinions of Admiral Nurses using the Mental Capacity Act.

Method: A volunteer sample of 15 Admiral Nurses were interviewed in 2008 about their experiences of explaining the legal framework to carers and people with dementia and expectations of the Act. Thematic analysis identified textual consistencies in the interviews.

Results: Most participants reported positively about the Mental Capacity Act and considered it beneficial when working with people with dementia and carers. Specific themes included knowledge acquisition and training, alongside limited confidence with implementation; practice experiences in the community and the empowering nature of the Mental Capacity Act; practice expectations and challenges with implementation.

Conclusion: The Mental Capacity Act has potential for supporting the safeguarding and empowerment role of community nurses. However, not all participants felt confident using it and speculated this would improve with greater familiarity and use, which should be facilitated by refresher training and supervision.

Relevance to clinical practice: The article concludes that nurses providing support to carers and of people with dementia may need greater familiarity about legal provisions. This may assist them in providing general information, making timely referrals to sources of specialist legal advice, and in using the Act to reduce anxiety, conflict and disputes.

© 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- How do Admiral Nurses and care home staff help people living with dementia and their family carers prepare for end-of-life? Moore KJ, Crawley S, Cooper C, Sampson EL, Harrison-Dening K. Moore KJ, et al. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020 Apr;35(4):405-413. doi: 10.1002/gps.5256. Epub 2020 Jan 19. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020. PMID: 31894598

- Specialist nursing support for unpaid carers of people with dementia: a mixed-methods feasibility study. Gridley K, Aspinal F, Parker G, Weatherly H, Faria R, Longo F, van den Berg B. Gridley K, et al. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Mar. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019 Mar. PMID: 30916917 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Transcultural nursing strategies for carers of people with dementia. Bunting M, Jenkins C. Bunting M, et al. Nurs Older People. 2016 Apr;28(3):21-5. doi: 10.7748/nop.28.3.21.s23. Nurs Older People. 2016. PMID: 27029989 Review.

- Specialist nursing and community support for the carers of people with dementia living at home: an evidence synthesis. Bunn F, Goodman C, Pinkney E, Drennan VM. Bunn F, et al. Health Soc Care Community. 2016 Jan;24(1):48-67. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12189. Epub 2015 Feb 16. Health Soc Care Community. 2016. PMID: 25684210

- Dementia nurses' experience of the Mental Capacity Act 2005: a follow-up study. Manthorpe J, Samsi K, Rapaport J. Manthorpe J, et al. Dementia (London). 2014 Jan;13(1):131-43. doi: 10.1177/1471301212454354. Epub 2012 Jul 11. Dementia (London). 2014. PMID: 24381044

- Advance decisions to refuse treatment and suicidal behaviour in emergency care: 'it's very much a step into the unknown'. Quinlivan L, Nowland R, Steeg S, Cooper J, Meehan D, Godfrey J, Robertson D, Longson D, Potokar J, Davies R, Allen N, Huxtable R, Mackway-Jones K, Hawton K, Gunnell D, Kapur N. Quinlivan L, et al. BJPsych Open. 2019 Jun 13;5(4):e50. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2019.42. BJPsych Open. 2019. PMID: 31530303 Free PMC article.

- The Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Bill 2013: content, commentary, controversy. Kelly BD. Kelly BD. Ir J Med Sci. 2015 Mar;184(1):31-46. doi: 10.1007/s11845-014-1096-1. Epub 2014 Mar 12. Ir J Med Sci. 2015. PMID: 24619367 Review.

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

Grants and funding

- RP-PG-0606-1005/DH_/Department of Health/United Kingdom

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Assessing the mental capacity of a person with dementia

The Mental Capacity Act gives guidance on assessing mental capacity – when it should be done and who should do it. This can be used when assessing the mental capacity of a person with dementia.

- Dementia and the Mental Capacity Act 2005

- You are here: Assessing the mental capacity of a person with dementia

- Making decisions for a person with dementia who lacks mental capacity

- Planning ahead using the Mental Capacity Act

- Mental Capacity Act – other resources

Mental Capacity Act

When should mental capacity be assessed in a person with dementia.

You must always assume that a person is able to make a decision for themselves, until it is proved that they can’t.

A person’s capacity may be questioned if there is doubt about whether they can make a particular decision. This could happen if:

- the person’s behaviour or circumstances are making those around them doubt whether the person has capacity to make a particular decision

- a professional says they have doubts about the person’s ability to make the decision – this could be a social worker or the person’s GP

- the person has previously been unable to make a decision for themselves.

To work out whether a person has capacity to make a decision, the law says you must do a test (often called an assessment) to find out whether they have the ability to make the particular decision at the particular time.

Before the person is tested, they should be given as much help as possible to make the decision for themselves. Those who are supporting the person to make the decision should find the most helpful way to communicate with the person. This may mean:

- trying to explain the information to them in a different way

- helping them to understand the ideas that are involved in making the decision

- breaking down information into small chunks.

Not all decisions need to be made immediately. It is sometimes possible to delay a decision until a person has capacity to make it. However, this won’t be possible for every decision.

Tips on communicating with a person with dementia

The person with dementia should be offered different ways of communicating their wishes and decisions. Better communication can make it easier to meet the needs of the person with dementia.

Who can assess mental capacity in a person with dementia?

In general, whoever is with the person when a decision is being made will assess their capacity. However, this will differ depending on the decision that needs to be made – for example:

- Everyday decisions (such as what someone will eat or wear) – whoever is with them at the time can assess the person’s capacity to make the decision. This is likely to be the person’s family member, carer or care worker.

- More complicated decisions (such as where someone will live or decisions about treatment) – a professional will assess the person’s capacity to make the decision.

In general, family members and carers know the person with dementia best. They can often tell when the person is or is not able to make a decision. When a person has dementia, it’s likely that they will have to do this more often as the person's condition progresses.

If the decision is complicated, the person's carer or family members can consult a professional, such as a solicitor or a health or social care professional. Note that certain professionals may charge for advice.

Whether it is someone close to the person or a professional, they must firmly believe that the person with dementia can’t make their own decision before taking action to make the decision for them. The steps below can help with this assessment.

How is mental capacity assessed in a person with dementia?

If you need to decide whether a person has the mental capacity to make a specific decision, follow the steps below.

Always try to use your knowledge of the person to help you decide. You can also ask other people for advice – such as the person’s GP, community nurse or social worker.

Are you concerned that a person with dementia is unable to make a certain decision?

Yes : Move to Step 2.

No : The person has mental capacity. Let them make their own decision.

Can the person make the decision with help and support – for example, if they are given the right information, given more time, and communicated with appropriately?

Yes : The person has mental capacity. Let them make their own decision.

No : Move to Step 3.

Does the person meet all of the following requirements?

- They understand all the information they need to make the decision.

- They can keep the information in their mind for long enough to make the decision.

- They can weigh up the information that is available in order to make a decision.

- They can communicate the decision in some way – for example, squeezing someone’s hand or blinking their eyes.

No : For this decision, at this time, the person lacks capacity. This means they cannot make the decision for themselves and someone will need to make it for them. For decisions about everyday things such as food and clothes, this may be a carer or relative. For a more complex decision, for example about treatment, a health or social care professional may be involved.

Challenges to mental capacity assessments

The outcome of a capacity assessment is sometimes challenged. This can happen for the following reasons:

- If someone else feels that a person had the mental capacity to make a decision, but they were not allowed to do so.

- If someone feels the person did not have the capacity to make a decision, but they were allowed to make one.

The person can challenge a capacity assessment themselves, or it could be challenged by their family member, friend or even a professional.

If you want to challenge a mental capacity assessment

- Start by speaking to the person who did the assessment. Ask why they made the decision they did and explain why you disagree with their assessment of the person’s capacity.

- If this doesn’t help, you can ask for the decision to be reviewed, either by the person who first made the assessment or by the organisation involved. This may be social services or a hospital.

- If you are still not satisfied, you can make a formal complaint. For example, if you disagree with a GP or a care home manager, the surgery or care home will have its own complaints procedure that you can follow. Ask them for information about how to make a complaint.

If you challenge a capacity assessment it could harm your relationship with the person who did the assessment. Therefore, before you challenge it, think about speaking to a local advice agency, a carers’ service or a solicitor.

If you contact a solicitor make sure you ask them at the start of your conversation how much they will charge. You can also speak to Alzheimer’s Society by calling our support line.

Dementia Support Line

If someone challenges a mental capacity assessment that you have made.

If this happens, try to stay calm. Take your time to explain why you believe the person could or couldn’t make the decision for themselves.

Carers and family members are not expected to write down each time they have to make a judgement about a person’s capacity and what their reasons were, especially when they are making decisions every day.

However, if you are asked, you should be able to give examples to show why you made the decision. This doesn’t happen often. Most family members and carers will never be challenged about the capacity assessments they make.

But it is something you should think about when you are judging whether the person has capacity to make a decision. The law says you must have a ‘reasonable belief’ that the person lacks capacity, so you would need to show that you had this belief.

- Email this page to a friend.

Previous Section

Next section, further reading.

What kind of information would you like to read? Use the button below to choose between help, advice and real stories.

Choose one or more options

- Information

- Real stories

- Dementia directory

Can people with dementia vote?

How to claim Pension Credit and qualify for a free TV licence

Retirement benefits for people affected by dementia

Help for people affected by dementia on a low income, benefits for people affected by dementia of working age, carer's allowance, disability and mobility benefits for people living with dementia, sign up for dementia support by email.

Our regular support email includes the latest dementia advice, resources, real stories and more.

You can change what you receive at any time and we will never sell your details to third parties. Here’s our Privacy Policy .

You are here:

- Information and support

- Financial and legal support

Mental capacity and decision-making for people with dementia

- Publication date: May 2024

- Review date: May 2026

- Download the Mental capacity and decision making leaflet / 1mb

- (opens in a new window)

Mental capacity is a legal term that refers to whether someone is capable of making informed decisions. A person with dementia is likely to lose capacity over time, so it is important to know what to do in this situation.

Loss of mental capacity in a person with dementia

Because dementia is a progressive condition, most people with the diagnosis reach a point where they cannot make their own decisions, for example about their health, care, finances and living arrangements. This is called loss of capacity.

To have capacity, a person must be able to:

- understand the information relevant to the decision they are making

- retain that information for long enough to make the decision

- weigh up the information as part of their decision-making process

- communicate their decision to others – this does not have to be verbal; for example, nodding, blinking or hand gestures may all count

When a person loses capacity, family members, friends or professionals such as a doctor, social worker or solicitor may need to make decisions for them.

Capacity can fluctuate – for example, a person might lose capacity due to an illness like delirium (sudden, intense confusion) but regain it when they recover. They may also have capacity to make some decisions (eg what to buy from the shops) but not others (eg whether to sell their home).

How to tell if a person with dementia has capacity

As a family member, you can assess whether the person with dementia has capacity, but you must follow the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice , which says:

- The person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they do not have capacity

- The person must not be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them do so have been taken without success

- The person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision simply because they make an unwise decision

- Any decision made for a person who lacks capacity must be in their best interests

- The decision must be made in the way that is least restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom

You might have an opinion about whether the person is able to make informed and safe decisions, but this is not a legal assessment of capacity; and making a decision that you disagree with does not necessarily mean they lack capacity. You must have ‘reasonable belief’ that they lack capacity according to the Mental Capacity Act , and be able to objectively explain your reasons to anyone who queries it.

Formal assessments of mental capacity for a person with dementia

If you are in any doubt about a person’s capacity, you can ask a professional to carry out a formal assessment of mental capacity. This is particularly important for major decisions like whether the person should move into a care home or sell their own home.

A formal assessment of mental capacity can be carried out by a professional such as a GP, social worker for decisions about health or care; or a solicitor for legal or financial decisions. They must consider two questions:

- Does the person have an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain?

- Does that impairment or disturbance mean they are unable to make the specific decision in question?

A formal assessment of mental capacity only covers the specific decision being made at that time – eg whether the person should receive an immediate medical treatment. If there are further decisions to be made, each will need a separate assessment.

The professional carrying out the assessment should keep a written record of the assessment and outcome.

Planning for a time when the person with dementia lacks capacity

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, they should be encouraged to start planning for the future as soon as possible. If the person has only recently been diagnosed or has young onset dementia (where symptoms develop before the age of 65) this may not seem urgent, but it is impossible to predict how quickly their condition will progress. Considering future plans early will make managing their care and finances less complicated and ensure their wishes are considered if they later lose capacity.

These plans should include:

An advance care plan (ACP) : this sets out the person’s wishes for their medical and personal care, including long-term care like moving into a nursing home. It is not legally binding but will help the people involved in the person’s care to make decisions in their best interests.

An advance decision : a legally binding document where a person decides to refuse certain medical treatments in the future if they cannot communicate their wishes at that time. It is also known as an advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or a living Will and includes life-sustaining treatment like CPR, ventilation and antibiotics.

Lasting power of attorney (LPA) : a legal process where the person appoints someone trusted to make decisions on their behalf. There are separate LPAs for health and welfare, and property and financial affairs. Without an LPA, you may not legally be allowed to make decisions on the person’s behalf – even if you are their next of kin. You may have to apply to the Court of Protection to become the person’s ‘ deputy ’, which can be a complicated process.

A Will : this ensures the person’s money and other assets like property are left to the people and causes of their choosing after their death. It can be very difficult to make or change a Will on behalf of someone who has lost capacity, so it is important for them to make their Will as soon as possible. Dementia UK has free Will-writing offers for anyone wishing to make or amend a Will.

Who can make decisions for a person with dementia who lacks capacity?

If a person with dementia has lost capacity, other people may have to make decisions on their behalf in their best interests. A ‘best interest meeting’ should be arranged which includes the person themselves if possible, their family/friends, health and social care professionals and anyone else who is actively involved with supporting them. Family and friends can only legally make decisions if they have been nominated in the person’s LPA.

Every attempt should be made to find out the wishes of the person with dementia. If they have an ACP, this should be taken into account.

Best interests decisions should always be the least restrictive option possible. For example, if the person wishes to go out for walks but they are vulnerable and would be at risk, the least restrictive option would be for someone to accompany them, rather than deciding they cannot go out at all.

Some decisions, such as selling the person’s home or moving into residential care, can be very difficult and may cause disagreements with the person with dementia and/or family members. The best outcome is where everyone involved comes to a consensus about the best interests of the person with dementia.

Where there is a dispute, the person can access an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) to support them to communicate their wishes.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) for a person with dementia

Deprivation of liberty refers to a person having their freedom restricted for their own safety and being under continual supervision and control – for example in hospital or a care home. Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) ensure that the restrictions are appropriate and proportionate.

It is only legal to deprive an individual of their liberty by placement in a care home or hospital if:

- it is in their best interests and necessary to protect them from harm

- there are no alternative less restrictive care options

Before someone is deprived of liberty, a mental health assessor must check if they lack capacity. They and a best interests assessor (usually a social worker, nurse, psychologist or occupational therapist) will then discuss whether deprivation of liberty is in the person’s best interests. The outcome can be challenged by anyone who feels the decision is wrong.

Sources of support

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about capacity and decision-making or any other aspect of dementia, please call our Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December) or email [email protected] .

Alternatively, you can book a phone or video appointment in our virtual clinic.

- Advance care planning

- Delirium (confusion)

- Dementia UK free Will offers

- Lasting power of attorney

- Advance decisions

- Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS)

- Deputies: make decisions for someone who lacks capacity

- Independent mental capacity advocates

- Making decisions: who decides when you can’t?

- Making a statutory Will on behalf of someone else

- Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice

- NHS: the Mental Capacity Act

Call the Dementia UK Helpline

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

It took me 40 years to hold my husband’s hand without fear – Mike’s story

Mike Parish, Founder of the LGBTQ+ Dementia Advisory Group, shares his journey caring for husband Tom and overcoming the fear of stigma.

“I can’t see how any family navigates dementia without an Admiral Nurse” – Elliott’s story

When Elliott’s father was diagnosed with young onset Alzheimer’s disease in his fifties, family life was changed forever.

Mohinder’s story – Reducing stigma in the Sikh community

Kaur talks about caring for her dad, Mohinder, since his mixed dementia diagnosis, and how community awareness needs to be improved.

What are the Five Key Principles of the Mental Capacity Act?

Last updated on 20th December 2023

In this article

The Mental Capacity Act contains five key principles, which must be applied at any time when the Act is being used for individuals who lack capacity.

It is useful for practitioners if they consider the principles in chronological order; principles 1 to 3 support the process before or at the point in identifying if someone lacks capacity. Once this has been ascertained, principles 4 and 5 support the subsequent decision-making process.

Anyone who is involved in applying the Act must be aware of each principle, what it means and, vitally, how it applies in each individual’s own circumstances. Although the principles must be applied lawfully, every person who is being assessed for capacity must be treated as a unique individual; two people who live with the same illness, for example dementia , will experience it in completely different ways and so coming to a decision about application of the principles will not be the same and assumptions about individuals’ capacity should never be made.

The five key principles are:

- Principle 1 – A presumption of capacity.

- Principle 2 – The right to be supported when making decisions.

- Principle 3 – An unwise decision cannot be seen as a wrong decision.

- Principle 4 – Best interests must be at the heart of all decision making.

- Principle 5 – Any intervention must be with the least restriction possible.

Principle 1 – A presumption of capacity

Every adult has a right to make their own decisions and they must be assumed to have the capacity to do so unless it is proven otherwise. Practitioners cannot assume that someone cannot make a decision for themselves just because they have a particular illness or disability, either physical or mental.

For example, if an individual has experienced a stroke, which has caused impairment to their ability to communicate, it is not acceptable to assume that this means that they lack capacity to make a decision, even if they might have some difficulties in communicating it.

Furthermore, in relation to this Principle, an assessment must only be sought if there is evidence to suggest that capacity might be an issue in terms of the decision that is being made.

When Principle 1 might be applied

- When the individual’s behavior or circumstances cause doubt about their capacity to make a decision.

- When someone is concerned about an individual’s capacity.

- When the individual has a previous diagnosis of an impairment that might impact their capacity to make some decisions.

Principle 2 – The right to be supported when making decisions

All individuals must be given every opportunity in terms of support and information before it is decided that they cannot decide for themselves. This means that every effort to encourage and support people to make decisions for themselves must be given, for example giving information in an alternative format to make it easier to understand – this is often referred to as ‘maximizing capacity’.

Other examples of ways in which capacity might be maximized include:

- Use of a signed language.

- Use of an interpreter (for verbal information).

- Use of a translator (for written information).

- Use of communication aids such as picture cards.

- Using an alternative communication format such as writing instead of speaking.

- Meeting with an individual on several different occasions to assess or review capacity.

- Changing a meeting’s location to one that is more suited to the individual’s needs.

- Changing a meeting’s time to one that is more suited to the individual’s needs.

When Principle 2 might be applied

If a lack of capacity is established then the individual must still be involved, as far as possible, in any decision that are made on their behalf.

This will apply when:

- Alternative forms of communication to ensure understanding have not been successful.

- Consistent attempts to change locations or times of a meeting have not been successful.

- Several meetings have all concluded that the individual’s level of capacity remains the same and that they are unable to make decisions on their own behalf.

Principle 2 Case study

Niko used to be a security guard working nightshifts at nightclubs and bars; after suffering a severe stroke however, he now requires full time care and supervision in a care home. Niko requires invasive surgery to fix a shunt in his brain to help alleviate pressure and reduce the likelihood of future strokes.

Initially the decision maker (DM) spoke to Niko about this decision around midday after a meeting at the care home; the DM suspected Niko lacked the capacity to make this decision as he presented as lethargic, withdrawn and disengaged.

However, the care home staff informed the DM that he is much more alert in the evenings as this was his routine for most of his working career. Upon returning out of hours, the DM was able to communicate more easily with Niko who was then able to make an informed decision.