Problem Solving Treatment (PST)

Problem-Solving Treatment (PST) is a brief form of evidence-based treatment that was originally developed in Great Britain for use by medical professionals in primary care. It is also known as Problem-Solving Treatment – Primary Care (PST-PC). PST has been studied extensively in a wide range of settings and with a variety of providers and patient populations.

PST teaches and empowers patients to solve the here-and-now problems contributing to their depression and helps increase self-efficacy. It typically involves six to ten sessions, depending on the patient’s needs. The first appointment is approximately one hour long because, in addition to the first PST session, it includes an introduction to PST techniques. Subsequent appointments are 30 minutes long.

PST is not indicated as a primary treatment for: substance abuse/dependence, acute primary post-traumatic stress disorder, panic disorder, new onset bipolar disorder, new onset psychosis.

Learn more about how to get trained in PST on this page .

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Problem-Solving Therapy?

Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArlinCuncic_1000-21af8749d2144aa0b0491c29319591c4.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Verywell / Madelyn Goodnight

Problem-Solving Therapy Techniques

How effective is problem-solving therapy, things to consider, how to get started.

Problem-solving therapy is a brief intervention that provides people with the tools they need to identify and solve problems that arise from big and small life stressors. It aims to improve your overall quality of life and reduce the negative impact of psychological and physical illness.

Problem-solving therapy can be used to treat depression , among other conditions. It can be administered by a doctor or mental health professional and may be combined with other treatment approaches.

At a Glance

Problem-solving therapy is a short-term treatment used to help people who are experiencing depression, stress, PTSD, self-harm, suicidal ideation, and other mental health problems develop the tools they need to deal with challenges. This approach teaches people to identify problems, generate solutions, and implement those solutions. Let's take a closer look at how problem-solving therapy can help people be more resilient and adaptive in the face of stress.

Problem-solving therapy is based on a model that takes into account the importance of real-life problem-solving. In other words, the key to managing the impact of stressful life events is to know how to address issues as they arise. Problem-solving therapy is very practical in its approach and is only concerned with the present, rather than delving into your past.

This form of therapy can take place one-on-one or in a group format and may be offered in person or online via telehealth . Sessions can be anywhere from 30 minutes to two hours long.

Key Components

There are two major components that make up the problem-solving therapy framework:

- Applying a positive problem-solving orientation to your life

- Using problem-solving skills

A positive problem-solving orientation means viewing things in an optimistic light, embracing self-efficacy , and accepting the idea that problems are a normal part of life. Problem-solving skills are behaviors that you can rely on to help you navigate conflict, even during times of stress. This includes skills like:

- Knowing how to identify a problem

- Defining the problem in a helpful way

- Trying to understand the problem more deeply

- Setting goals related to the problem

- Generating alternative, creative solutions to the problem

- Choosing the best course of action

- Implementing the choice you have made

- Evaluating the outcome to determine next steps

Problem-solving therapy is all about training you to become adaptive in your life so that you will start to see problems as challenges to be solved instead of insurmountable obstacles. It also means that you will recognize the action that is required to engage in effective problem-solving techniques.

Planful Problem-Solving

One problem-solving technique, called planful problem-solving, involves following a series of steps to fix issues in a healthy, constructive way:

- Problem definition and formulation : This step involves identifying the real-life problem that needs to be solved and formulating it in a way that allows you to generate potential solutions.

- Generation of alternative solutions : This stage involves coming up with various potential solutions to the problem at hand. The goal in this step is to brainstorm options to creatively address the life stressor in ways that you may not have previously considered.

- Decision-making strategies : This stage involves discussing different strategies for making decisions as well as identifying obstacles that may get in the way of solving the problem at hand.

- Solution implementation and verification : This stage involves implementing a chosen solution and then verifying whether it was effective in addressing the problem.

Other Techniques

Other techniques your therapist may go over include:

- Problem-solving multitasking , which helps you learn to think clearly and solve problems effectively even during times of stress

- Stop, slow down, think, and act (SSTA) , which is meant to encourage you to become more emotionally mindful when faced with conflict

- Healthy thinking and imagery , which teaches you how to embrace more positive self-talk while problem-solving

What Problem-Solving Therapy Can Help With

Problem-solving therapy addresses life stress issues and focuses on helping you find solutions to concrete issues. This approach can be applied to problems associated with various psychological and physiological symptoms.

Mental Health Issues

Problem-solving therapy may help address mental health issues, like:

- Chronic stress due to accumulating minor issues

- Complications associated with traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Emotional distress

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Problems associated with a chronic disease like cancer, heart disease, or diabetes

- Self-harm and feelings of hopelessness

- Substance use

- Suicidal ideation

Specific Life Challenges

This form of therapy is also helpful for dealing with specific life problems, such as:

- Death of a loved one

- Dissatisfaction at work

- Everyday life stressors

- Family problems

- Financial difficulties

- Relationship conflicts

Your doctor or mental healthcare professional will be able to advise whether problem-solving therapy could be helpful for your particular issue. In general, if you are struggling with specific, concrete problems that you are having trouble finding solutions for, problem-solving therapy could be helpful for you.

Benefits of Problem-Solving Therapy

The skills learned in problem-solving therapy can be helpful for managing all areas of your life. These can include:

- Being able to identify which stressors trigger your negative emotions (e.g., sadness, anger)

- Confidence that you can handle problems that you face

- Having a systematic approach on how to deal with life's problems

- Having a toolbox of strategies to solve the issues you face

- Increased confidence to find creative solutions

- Knowing how to identify which barriers will impede your progress

- Knowing how to manage emotions when they arise

- Reduced avoidance and increased action-taking

- The ability to accept life problems that can't be solved

- The ability to make effective decisions

- The development of patience (realizing that not all problems have a "quick fix")

Problem-solving therapy can help people feel more empowered to deal with the problems they face in their lives. Rather than feeling overwhelmed when stressors begin to take a toll, this therapy introduces new coping skills that can boost self-efficacy and resilience .

Other Types of Therapy

Other similar types of therapy include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) . While these therapies work to change thinking and behaviors, they work a bit differently. Both CBT and SFBT are less structured than problem-solving therapy and may focus on broader issues. CBT focuses on identifying and changing maladaptive thoughts, and SFBT works to help people look for solutions and build self-efficacy based on strengths.

This form of therapy was initially developed to help people combat stress through effective problem-solving, and it was later adapted to address clinical depression specifically. Today, much of the research on problem-solving therapy deals with its effectiveness in treating depression.

Problem-solving therapy has been shown to help depression in:

- Older adults

- People coping with serious illnesses like cancer

Problem-solving therapy also appears to be effective as a brief treatment for depression, offering benefits in as little as six to eight sessions with a therapist or another healthcare professional. This may make it a good option for someone unable to commit to a lengthier treatment for depression.

Problem-solving therapy is not a good fit for everyone. It may not be effective at addressing issues that don't have clear solutions, like seeking meaning or purpose in life. Problem-solving therapy is also intended to treat specific problems, not general habits or thought patterns .

In general, it's also important to remember that problem-solving therapy is not a primary treatment for mental disorders. If you are living with the symptoms of a serious mental illness such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia , you may need additional treatment with evidence-based approaches for your particular concern.

Problem-solving therapy is best aimed at someone who has a mental or physical issue that is being treated separately, but who also has life issues that go along with that problem that has yet to be addressed.

For example, it could help if you can't clean your house or pay your bills because of your depression, or if a cancer diagnosis is interfering with your quality of life.

Your doctor may be able to recommend therapists in your area who utilize this approach, or they may offer it themselves as part of their practice. You can also search for a problem-solving therapist with help from the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Society of Clinical Psychology .

If receiving problem-solving therapy from a doctor or mental healthcare professional is not an option for you, you could also consider implementing it as a self-help strategy using a workbook designed to help you learn problem-solving skills on your own.

During your first session, your therapist may spend some time explaining their process and approach. They may ask you to identify the problem you’re currently facing, and they’ll likely discuss your goals for therapy .

Keep In Mind

Problem-solving therapy may be a short-term intervention that's focused on solving a specific issue in your life. If you need further help with something more pervasive, it can also become a longer-term treatment option.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Shang P, Cao X, You S, Feng X, Li N, Jia Y. Problem-solving therapy for major depressive disorders in older adults: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials . Aging Clin Exp Res . 2021;33(6):1465-1475. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01672-3

Cuijpers P, Wit L de, Kleiboer A, Karyotaki E, Ebert DD. Problem-solving therapy for adult depression: An updated meta-analysis . Eur Psychiatry . 2018;48(1):27-37. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.11.006

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, D'Zurilla TJ. Problem-Solving Therapy: A Treatment Manual . New York; 2013. doi:10.1891/9780826109415.0001

Owens D, Wright-Hughes A, Graham L, et al. Problem-solving therapy rather than treatment as usual for adults after self-harm: a pragmatic, feasibility, randomised controlled trial (the MIDSHIPS trial) . Pilot Feasibility Stud . 2020;6:119. doi:10.1186/s40814-020-00668-0

Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Corrigall J, et al. The efficacy of a blended motivational interviewing and problem solving therapy intervention to reduce substance use among patients presenting for emergency services in South Africa: A randomized controlled trial . Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy . 2015;10(1):46. doi:doi.org/10.1186/s13011-015-0042-1

Margolis SA, Osborne P, Gonzalez JS. Problem solving . In: Gellman MD, ed. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine . Springer International Publishing; 2020:1745-1747. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39903-0_208

Kirkham JG, Choi N, Seitz DP. Meta-analysis of problem solving therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder in older adults . Int J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2016;31(5):526-535. doi:10.1002/gps.4358

Garand L, Rinaldo DE, Alberth MM, et al. Effects of problem solving therapy on mental health outcomes in family caregivers of persons with a new diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia: A randomized controlled trial . Am J Geriatr Psychiatry . 2014;22(8):771-781. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.07.007

Noyes K, Zapf AL, Depner RM, et al. Problem-solving skills training in adult cancer survivors: Bright IDEAS-AC pilot study . Cancer Treat Res Commun . 2022;31:100552. doi:10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100552

Albert SM, King J, Anderson S, et al. Depression agency-based collaborative: effect of problem-solving therapy on risk of common mental disorders in older adults with home care needs . The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry . 2019;27(6):619-624. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.002

By Arlin Cuncic, MA Arlin Cuncic, MA, is the author of The Anxiety Workbook and founder of the website About Social Anxiety. She has a Master's degree in clinical psychology.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Libyan J Med

Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of primary care patients presenting with psychological disorders

Mental disorders affect a great number of people worldwide. Four out of the 10 leading causes of disability in the world are mental disorders. Because of the scarcity of specialists around the world and especially in developing countries, it is important for primary care physicians to provide services to patients with mental disorders. The most widely researched and used psychological approach in primary care is cognitive behavioral therapy. Due to its brief nature and the practical skills it teaches, it is convenient for use in primary care settings. The following paper reviews the literature on psychotherapy in primary care and provides some practical tips for primary care physicians to use when they are faced with patients having mental disorders.

Mental disorders affect a great number of people worldwide. It is estimated that one quarter of the adult population of the United States suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), among the top 10 leading causes of disability in developing countries, four are mental illnesses. Also, it is projected that by the year 2020, depression will be the leading cause of disability among children and women ( 1 ). Only 23% of people with mental illness seek treatment because of lack of available appropriate services and poor insurance coverage ( 2 ). These numbers stress the importance of making mental health services more accessible to the population. One key way of doing that is by training primary health care providers in diagnosing mental disorders and providing proper treatment to patients affected by them. Psychotherapy is one of the treatment options that a person suffering from a psychological disorder has. It usually involves one-on-one session between a trained psychotherapist and a patient during which the patient's problems or stressors are discussed. The aim of psychotherapy is to resolve these problems in a way that will ensure the patient a better quality of life. There are different kinds of psychotherapies currently used, each based on a different theory ( 3 ). In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO), it was estimated that around 10% of the population suffers from mental health conditions and 25% of families in this region has a member suffering from such a condition. Mental illness accounts for 11% of the burden of disease in EMRO countries ( 4 ). In a study conducted in Lebanon, it was shown that the lifetime prevalence of mental health disorders reaches up to 25.8% of the population. The most commonly diagnosed disorders were anxiety (16.7%) and mood disorders (12.6%) ( 5 ). On the contrary, it was documented that in 2007 the ratio of psychiatrists per 100,000 people in the Arab world ranged from 0 to 3.4 with Qatar having the highest percentage of psychiatrists in the Arab world. The ratio of psychologists in Arab world per 100,000 people ranged from 0 to 5 with Libya having the highest percentage of psychologists ( 6 ). Considering these very low numbers of mental health care providers compared to the high number of mental health problems, it is of high importance to bridge the gap between people suffering from mental health problems and mental health care providers in this part of the world. The WHO estimated this treatment gap to exceed 75% in low- to middle-income countries ( 7 ). A way to bridge this large gap, as suggested by the mental health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) launched by the WHO, is to train primary care workers to provide mental health services themselves to their patients presenting with psychiatric conditions. By doing so, more people will gain access to treat their mental health conditions in a quick, cost-effective way ( 7 ). Therefore, the main focus of this review is to discuss how different psychotherapeutic approaches have been used in primary care settings and how to best integrate and apply these approaches and techniques.

Cognitive behavioral therapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a structured psychotherapeutic approach built on a collaborative relationship between the patient and the psychotherapist. It is a short-term treatment that requires an average of 12 sessions. One of the main elements of CBT is psychoeducation, a process by which a therapist provides the client with information about the process of therapy and about their condition. It is also important to teach patients some stress management techniques to cope with stressful situations more effectively. Patients need to be educated about stress and taught strategies to reduce it. They are educated about specific relaxation techniques such as deep breathing exercises and progressive muscle relaxation that they can use on their own when feeling distressed. Another important element of CBT is that it focuses on the present problem without needing to go back to past life events. At the beginning of therapy, the therapist helps the patient set goals for treatment and along the sessions, progress is monitored. The cognitive aspect of this approach focuses on identifying the patient's maladaptive beliefs about themselves after which the therapist challenges these beliefs in the aim of replacing them with more adaptive ones. The first step in identifying these beliefs is by exploring the patient's automatic thoughts. An automatic thought is the first thought a person has after a certain event. In the session, the patient is asked to recount recent negative events. Once they do so, they are asked to describe the first thought that they had after the events. Patterns usually emerge, as patients tend to think in similar ways when faced with different situations. For example, if they fail a test, they might have the automatic thought ‘I am a failure’. This same automatic thought may also arise in other situations such as when they have an argument with someone or if they try to fix their malfunctioning computer but fail to do so, for example. Through exploring the pattern in these automatic thoughts, maladaptive beliefs start to surface ( 8 ). Once the maladaptive beliefs are identified they need to be challenged and replaced with more adaptive ones. Challenging maladaptive beliefs can be done through reality testing, an exercise during which the patient is asked to present evidence for and against their beliefs to see whether they are correct or not. This can easily be done by having the patient draw a pros and cons table and write down evidence for and against this belief. Once they realize that this belief is not supported by evidence, they can then be taught how to replace that belief with a more adaptive one ( 8 ). The use of behavioral experiments in the form of homework can also help in that change. The patient can be asked to complete a mood log at home in which he/she notes situations that happen during the day and the resulting emotions and thoughts that accompany the event. This exercise helps the patient and the physician understand the patterns in the patient's life. Behavior activation can also be advised by helping the patient identify certain hobbies or even previously pleasurable activities for them to engage in ( 3 ).

Behavior activation

Behavior activation is one of type of CBT and it relies on scheduling activities for patients to engage in that can give them a sense of achievement or pleasure to elevate their mood. Most patients coming to seek help for their mental problems have stopped engaging in activities they used to enjoy and spend most of their time withdrawn and doing activities that affect their mood negatively such as watching TV for long hours or staying in bed. The goal of behavior activation is to get them active again, which will elevate their mood and give them a sense of control because they will notice that they can actually help themselves feel better by engaging in simple activities. The first step of behavior activation is to get a sense of what a day in the patient's life looks like. By doing so, it will become more evident what activities they are engaging in, if any. It is also helpful to ask about activities that used to bring them pleasure in the past. The primary care physician then discusses with the patient the importance of including pleasurable activities in their life and they agree on one or two activities to begin with for the patient to engage in until their next visit. Examples of activities can vary from making plans with friends, going to the gym, taking a walk, doing activities around the house. Once the patient engages in these agreed upon activities, they can write down how they felt after engaging in the activity. During their next visit, they discuss these activities with the physician and they share the feelings that emerged from them. After seeing the positive effects of these small activities on their mood, the patients become more aware of their control over their mood and will feel less helpless. This in turn will help them engage in more activities and consequently will lift their mood further ( 8 ).

CBT in primary care

Several studies have examined whether this approach is suitable for use in primary health care settings when treating patients with different psychological disorders. Major Depressive Disorder is one of the most common psychological disorders encountered by primary care physicians ( 9 ). In their study, Conradi et al. ( 9 ) compared the effectiveness of usual care alone to usual care combined with psychoeducation, psychiatric follow-up or brief CBT in treating patients with major depression in primary care settings. The results of the study showed that including psychiatric follow-up or brief CBT to usual primary care increases the response rate of patients with depression. Including psychoeducation alone did not lead to any different results than having usual care alone. Therefore, brief CBT in primary care is effective in treating depression. It is important to note that the effects of CBT in this study were maintained at 3 years follow-up ( 9 ). A study conducted by Serfaty et al. ( 10 ) showed similar results. In this study, the sample comprised of geriatric primary care patients experiencing symptoms of depression. Compared to those who underwent usual primary care, patients who received CBT had better outcomes and fewer depression symptoms by the end of treatment and at 10 months follow-up. The same outcome was shown in another study that included patients aged 18–75 years. In this study, the results showed that usual primary care for patients with depression, which includes pharmacotherapy, is most effective when combined with brief CBT. The effects of the intervention were maintained at 12 months follow-up ( 11 ). In a study including a patient's choice arm, it was shown that Sertraline, an SSRI, was superior to placebo in treating mild depression. The patients receiving CBT in this study did not show more improvement than the placebo pill group but patients randomized to the CBT group showed marked improvement compared to a self-help group. Even when the patients were given the choice of treatment, CBT or medication, the results were the same as when the patients were randomized into the different groups. This study shows that Sertraline is effective in treating mild depression, an approach that is both time and cost effective. The authors, however, suggest that there might have been a methodological problem, which may have limited the effects of CBT in this study. They recommend, however, the inclusion of specific CBT techniques such as problem solving skills into usual care, so as to provide patients with effective medication as well as the skills they need to overcome their depressive symptoms ( 12 ).

The effectiveness of CBT in primary care settings was also studied with patients suffering from anxiety disorders, namely generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and panic disorder. Panic disorder is characterized by recurring panic attacks with or without agoraphobia or fear of places from which escape is difficult. Because of the bodily sensations that accompany panic attacks, it is common to see patients with panic disorders in primary care settings ( 13 ). In this study, patients were randomly assigned to either receive treatment as usual which consists of pharmacotherapy or six sessions of CBT delivered over 12 weeks combined with pharmacotherapy. The results showed that pharmacotherapy combined with CBT led to better treatment outcomes than usual care alone. The results were maintained up to 12 months follow-up ( 13 ). Sharp et al. ( 14 ) compared the administration in primary care settings of individual CBT versus group CBT to individuals suffering from panic disorders with or without agoraphobia to a wait list control group. The results showed that patients who received any form of CBT, group or individual, showed significant improvement compared to the wait list control. There were, however, no differences between both treatment groups. At 3 months follow-up, on the contrary, the patients receiving individual CBT showed significantly better maintenance of the positive effects of treatment that those who took part in a group-based CBT intervention ( 14 ). It was also shown that CBT can help alleviate some symptoms of GAD in older adults ( 15 ). GAD is characterized by excessive worrying over almost all aspects of one's life. In this study, the authors were interested in testing the effectiveness of CBT delivered in primary care settings in treating GAD in older adults. To that end, patients presenting with GAD were randomized to one of two groups; the first group received usual care for GAD, which consists of pharmacotherapy while the second group received pharmacotherapy along with CBT. Their CBT intervention included psychoeducation, relaxation techniques, training in problem solving, cognitive restructuring, and behavior modification. The results of the study showed that the patients receiving CBT had an overall decrease in worry, symptoms of depression and overall psychopathology. However, there were no differences on measures of GAD severity between the two groups indicating that both approaches were effective in managing symptoms of GAD ( 15 ).

The focus of the literature on CBT in primary care settings has been on treating depression and anxiety, the most common mental health disorders in primary care settings, as outlined above. However, other studies have been focused on studying the effects of this therapeutic approach in treating other less common disorders. In fact, CBT as opposed to usual care has been shown to effectively treat insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, low self-esteem, chronic fatigue, and somatization disorder ( 16 – 20 ).

Other forms of psychotherapy in primary care

While CBT is the most widely used approach to treat patients presenting to primary care settings with mental health conditions, the efficacy of other approaches have also been examined in the literature ( 21 ). Cognitive therapy is based on the premise that patients have maladaptive thoughts that need to be challenged. For the treatment of panic disorder, the main focus is on the patients’ beliefs about their bodily sensations during a panic attack, which they often misinterpret as a life-threatening heart attack. The difference between cognitive therapy and CBT is that this approach does not rely on behavior modification as part of treatment. The results of the study showed that compared to treatment as usual which decreases panic severity and general anxiety and depression symptoms, the patients who received CBT showed greater response to treatment with less recurrent panic attacks and more than half of the patients reported being panic-free after treatment ( 22 ). On the contrary, another study explored the effectiveness of CBT on depressed patients in primary care settings. This treatment replies on the principles of behavior activation to treat depressive symptoms. The results showed improvement in depression symptoms as well as quality of life in the patients who received CBT ( 23 ). In one study, elderly patients suffering from major depression or dysthymia were randomly assigned to Problem Solving Therapy or community psychology, which they referred to as treatment as usual in this study. Problem Solving Therapy is a brief form of therapy especially tailored for use in primary care settings; it consists of psychoeducation and teaching the patients a set of problem solving skills. The results showed that even though patients in both groups showed significant improvement and there were no significant group differences, at 2 years follow-up, the patients who received problem solving therapy showed more durable beneficial outcomes from treatment than those who received usual care ( 24 ). In another study targeting the same population, the authors compared interpersonal psychotherapy to usual care. Interpersonal psychotherapy is a brief structured therapy, which starts with psychoeducation and focuses on a patient's interpersonal relationships and recent interpersonal events that may be affecting the patient after which possible solutions are thought of and skills to implement them are taught. This study showed that elderly patients with moderate to severe depression responded better to Interpersonal Psychotherapy than treatment as usual. There were, however, no differences reported for patients suffering from mild depression ( 25 ). The same findings were confirmed in a study conducted by Schulberg et al. ( 26 ). In a meta-analysis conducted by Bower et al. ( 27 ) comparing counseling in primary care to treatment as usual, it was noted that counseling leads to significantly better results in treating patients with depression and anxiety than usual care alone. It was, however, also shown that the beneficial effects are short lived as the patients who received counseling and those who received usual care showed no differences at later follow-ups.

To sum up, because of the-high prevalence rate of psychological disorders in the Arab world ( 4 , 5 ) and the lack of sufficient specialized mental health professionals ( 6 ), it is imperative that some form of psychotherapy is included in primary care practice to treat patients with mental health conditions. The most widely supported evidence-based approach in the literature is CBT but other approaches have also proven to be superior to pharmacotherapy or usual care in treating psychological disorders, namely anxiety and depression. The general agreement in the literature, as summarized above, is that a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy yield the best results. It can be argued, however, that the severity of the mental illness the patient is suffering from plays a role in which approach works best. In fact, the majority of the literature on this issue discusses the effects of providing psychotherapy along with pharmacotherapy in primary care settings to patients with mild depression or anxiety. No study has been found discussing severe forms of these disorders and how they can be managed in primary care settings. In severe cases, it may be advisable to refer patients to more specialized professionals.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Issues by year

Advertising

Volume 41, Issue 9, September 2012

Problem solving therapy Use and effectiveness in general practice

Problem solving therapy has been described as pragmatic, effective and easy to learn. It is an approach that makes sense to patients and professionals, does not require years of training and is effective in primary care settings. 1 It has been described as well suited to general practice and may be undertaken during 15–30 minute consultations. 2

Problem solving therapy takes its theoretical base from social problem solving theory which identifies three distinct sequential phases for addressing problems: 3

- discovery (finding a solution)

- performance (implementing the solution)

- verification (assessing the outcome).

Initially, the techniques of social problem solving emerged in response to empirical observations including that people experiencing depression exhibit a reduced capacity to resolve personal and social problems. 4,5 Problem solving therapy specifically for use in primary care was then developed. 6

Problem solving therapy has been shown to be effective for many common mental health conditions seen by GPs, including depression 7–9 and anxiety. 10,11 Most research has focused on depression. In randomised controlled trials, when delivered by appropriately trained GPs to patients experiencing major depression, PST has been shown to be more effective than placebo and equally as effective as antidepressant medication (both tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs]). 7,8 A recent meta-analysis of 22 studies reported that for depression, PST was as effective as medication and other psychosocial therapies, and more effective than no treatment. 9 For patients experiencing anxiety, benefit from PST is less well established. It has been suggested it is most effective with selected patients experiencing more severe symptoms who have not benefited from usual GP care. 10 Problem solving therapy may also assist a group of patients often seen by GPs: those who feel overwhelmed by multiple problems but who have not yet developed a specific diagnosis.

Although PST has been shown to be beneficial for many patients experiencing depression, debate continues about the mechanism(s) through which the observed positive impact of PST on patient affect is achieved. Two mechanisms have been proposed: the patient improves because they achieve problem resolution, or they improve because of a sense of empowerment gained from PST skill development. 12 Perhaps both factors play a part in achieving the benefits of PST as a therapeutic intervention. The observed benefit of PST for patients experiencing anxiety may be due to problem resolution and consequent reduction in distress from anticipatory concern about the identified but unsolved problem.

It is important to note that, while in the clinical setting we may find ourselves attempting to solve problems for patients and to advise them on what we think they should do, 13 this is not PST. Essential to PST, as an evidence based therapeutic approach, is that the clinician helps the patient to become empowered to learn to solve problems for themselves. The GP's role is to work through the stages of PST in a structured, sequential way to determine and to implement the solution selected by the patient. These stages have been described previously. 14 Key features of PST are summarised in Table 1 .

Using PST in general practice

Using PST, like any other treatment approach, depends on identifying patients for whom it may be useful. Patients experiencing a symptom relating to life difficulties, including relationship, financial or employment problems, which are seen by the patient in a realistic way, may be suitable for PST. Frequently, such patients feel overwhelmed and at times confused by these difficulties. Encouraging the patient to clearly define the problem(s) and deal with one problem at a time can be helpful. To this end, a number of worksheets have been developed. A simple, single page worksheet is shown in Figure 1 . A typical case study in which PST may be useful is presented in Table 2 . By contrast, patients whose thinking is typically characterised by unhelpful negative thought patterns about themself or their world may more readily benefit from cognitive strategies that challenge unhelpful negative thought patterns (such as cognitive behaviour therapy [CBT]). 15 Some problems not associated with an identifiable implementable solution, including existential questions related to life meaning and purpose, may not be suitable for PST. Identification of supportive and coping strategies along with, if appropriate, work around reframing the question may be more suitable for such patients.

Problem solving therapy may be used with patients experiencing depression who are also on antidepressant medication. It may be initiated with medication or added to existing pharmacotherapy. Intuitively, we might expect enhanced outcomes from combined PST and pharmacotherapy. However, research suggests this does not occur, with PST alone, medication alone and a combination of PST and medication each resulting in a similar patient outcomes.8 In addition to GPs, PST may be provided by a range of health professionals, most commonly psychologists. General practitioners may find they have a role in reinforcing PST skills with patients who developed their skills with a psychologist, especially if all Better Access Initiative sessions with the psychologist have been utilised.

The intuitive nature of PST means its use in practice is often straightforward. However, this is not always the case. Common difficulties using PST with patients and potential solutions to these difficulties have previously been discussed by the author 14 and are summarised in Table 3 . Problem solving therapy may also have a role in supporting marginalised patients such as those experiencing major social disadvantage due to the postulated mechanism of action of empowerment of patients to address symptoms relating to life problems. 12 of action includes empowerment of patients to address symptom causing life problems. Social and cultural context should be considered when using PST with patients, including conceptualisation of a problem, its significance to the patient and potential solutions.

General practitioners may be concerned that consultations that include PST will take too much time. 13 However, Australian research suggests this fear may not be justified with many GPs being able to provide PST to a simulated patient with a typical presentation of depression in 20 minutes. 15 Therefore, the concern over consultation duration may be more linked to established patterns of practice than the use of PST. Problem solving therapy may add an increased degree of structure to complex consultations that may limit, rather than extend, consultation duration.

Figure 1. Problem solving therapy patient worksheet

PST skill development for GPs

Many experienced GPs have intuitively developed valuable problem solving skills. Learning about PST for such GPs often involves refining and focusing those skills rather than learning a new skill from scratch. 13 A number of practical journal articles 16 and textbooks 10 that focus on developing PST skills in primary care are available. In addition, PST has been included in some interactive mental health continuing medical education for GPs. 17 This form of learning has the advantage of developing skills alongside other GPs.

Problem solving therapy is one of the Medicare supported FPS available to GPs. It is an approach that has developed from a firm theoretical basis and includes principles that will be familiar to many GPs. It can be used within the constraints of routine general practice and has been shown, when provided by appropriately skilled GPs, to be as effective as antidepressant medication for major depression. It offers an additional therapeutic option to patients experiencing a number of the common mental health conditions seen in general practice, including depression 7–9 and anxiety. 10,11

Conflict of interest: none declared.

- Gask L. Problem-solving treatment for anxiety and depression: a practical guide. Br J Psychiatry 2006;189:287–8. Search PubMed

- Hickie I. An approach to managing depression in general practice. Med J Aust 2000;173:106–10. Search PubMed

- D'Zurilla T, Goldfried M. Problem solving and behaviour modification. J Abnorm Psychol 1971;78:107–26. Search PubMed

- Gotlib I, Asarnow R. Interpersonal and impersonal problem solving skills in mildly and clinically depressed university students. J Consult Clin Psychol 1979;47:86–95. Search PubMed

- D'Zurilla T, Nezu A. Social problem solving in adults. In: Kendall P, editor. Advances in cognitive-behavioural research and therapy. New York: Academic Press, 1982. p. 201–74. Search PubMed

- Hegel M, Barrett J, Oxman T. Training therapists in problem-solving treatment of depressive disorders in primary care: lessons learned from the: "Treatment Effectiveness Project". Fam Syst Health 2000;18:423–35. Search PubMed

- Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Lloyd-Thomas AR, Tomlinson D. Randomised control trial comparing problem solving treatment with Amitryptyline and placebo for major depression in primary care. BMJ 1995;310:441–5. Search PubMed

- Mynors-Wallis LM, Gath DH, Day A, Baker F. Randomised controlled trial of problem solving treatment, antidepressant medication, and combined treatment for major depression in primary care. BMJ 2000;320:26–30. Search PubMed

- Bell A, D'Zurilla. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2009;29:348–53. Search PubMed

- Mynors-Wallis L Problem solving treatment for anxiety and depression. Oxford: OUP, 2005. Search PubMed

- Seekles W, van Straten A, Beekman A, van Marwijk H, Cuijpers P. Effectiveness of guided self-help for depression and anxiety disorders in primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res 2011;187:113–20. Search PubMed

- Mynors- Wallis L. Does problem-solving treatment work through resolving problems? Psychol Med 2002;32:1315–9. Search PubMed

- Pierce D, Gunn J. GPs' use of problem solving therapy for depression: a qualitative study of barriers to and enablers of evidence based care. BMC Fam Pract 2007;8:24. Search PubMed

- Pierce D, Gunn J. Using problem solving therapy in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2007;36:230–3. Search PubMed

- Pierce D, Gunn J. Depression in general practice, consultation duration and problem solving therapy. Aust Fam Physician 2011;40:334–6. Search PubMed

- Blashki G, Morgan H, Hickie I, Sumich H, Davenport T. Structured problem solving in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 2003;32:836–42. Search PubMed

- SPHERE a national mental health project. Available at www.spheregp.com.au [Accessed 17 April 2012]. Search PubMed

Also in this issue: Psychological strategies

Professional

Printed from Australian Family Physician - https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2012/september/problem-solving-therapy © The Australian College of General Practitioners www.racgp.org.au

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The use of problem-solving therapy for primary care to enhance complex decision-making in healthy community-dwelling older adults.

- 1 Division of Cognitive Neuroscience, Department of Neurology, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, United States

- 2 Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, OK, United States

- 3 Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Some older adults who are cognitively healthy have been found to make poor decisions. The vulnerability of such older adults has been postulated to be the result of disproportionate aging of the frontal lobes that contributes to a decline in executive functioning abilities among some older adults. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether decision-making performance in older adults can be enhanced by a psychoeducational intervention. Twenty cognitively and emotionally intact persons aged 65 years and older were recruited and randomized into two conditions: psychoeducational condition [Problem-Solving Therapy for Primary Care (PST-PC)] and no-treatment Control group. Participants in the psychoeducational condition each received four 45-min sessions of PST-PC across a 2-week period. The Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) was administered as the outcome measure to the treatment group, while participants in the Control group completed the IGT without intervention. A significant interaction effect was observed between group status and the trajectory of score differences across trials on the IGT. Particularly, as the task progressed to the last 20% of trials, participants in the PST-PC group significantly outperformed participants in the Control group in terms of making more advantageous decisions. These findings demonstrated that a four-session problem-solving therapy can reinforce aspects of executive functioning (that may have declined as a part of healthy aging), thereby enhancing complex decision-making in healthy older adults.

Introduction

The ability of older adults to make sound decisions regarding retirement, allocation of resources, living arrangements, health insurance, and medical procedures has a profound effect on the well-being of the individual as well as society, cumulatively. Even older adults who are cognitively healthy, without a neurodegenerative disease or mild cognitive impairment, have been found to make poor decisions ( Denburg et al., 2007 ). Specifically, some older adults fail to make advantageous decisions and become susceptible to scams, make poor financial decisions, or experience abuse of trust and get taken advantage of by others. These forms of financial exploitation have been reported to increase dramatically among older adults ( Lichtenberg et al., 2015 ).

The weaknesses in decision-making capacity among older adults have been postulated to be triggered by a distinct neurological change: disproportionate age-related decline of the frontal lobes of the brain ( West, 1996 ). In particular, the frontal lobe hypothesis of cognitive aging posits that cognitive abilities dependent on the frontal regions of the brain would experience a disproportionate age-related decline, whereas other functioning independent of the frontal lobes will remain relatively intact ( West, 1996 ). This theory has gained support from multiple neuroscience disciplines, including neuropsychology, neuroanatomy, and functional neuroimaging (see review by, Reuter-Lorenz et al., 2016 ). The reasons why some older adults are vulnerable and susceptible to making poor decisions have been examined thoroughly through neurobiological and behavioral mechanisms, and research on applied contexts has been important to understanding day-to-day decisions ( Hess et al., 2015 ). Much of the current research on aging and decision making in applied domains has focused on the implication of decisions in various contexts such as medical decision-making ( Leventhal et al., 2015 ), health-related decisions ( Liu et al., 2015 ), and consumer decision-making ( Carpenter and Yoon, 2015 ). Yet, research efforts examining interventions to enhance older adults decision-making abilities are lacking.

Deficits in decision-making may be a function of weaknesses in executive functioning. Specifically, executive functions involve abilities such as planning, organization, goal setting, initiation, and utilization of feedback and attention shifting – all essential skills necessary in the process of decision-making. A review of the treatment modalities revealed that Problem-Solving Therapy for Primary Care (PST-PC; Hegel and Arean, 2003 ) is one treatment modality to have demonstrated efficacy in managing such executive dysfunction ( Alexopoulous et al., 2003 ).

Problem-Solving Therapy for Primary Care was developed as an efficient modality to treat patients in busy primary care settings over the course of 4–8 sessions. It has been found that as few as three sessions of PST-PC could be beneficial ( Mynors-Wallis et al., 2000 ; Hegel et al., 2004 ; Arean et al., 2008 ). Trained specialists can deliver PST-PC after undergoing a brief training module ( Hegel et al., 2004 ; Arean et al., 2008 ). Furthermore, PST-PC has been demonstrated to be as effective when implemented by nurses and primary care physicians as compared to implementation by mental health professionals ( Mynors-Wallis et al., 2000 ; Unutzer et al., 2002 ). When comparing PST-PC with antidepressants among depressed patients, PST-PC has been shown to be just as efficacious in improving psychological symptoms and social functioning ( Mynors-Wallis et al., 1995 ). Furthermore, the effectiveness of PST-PC has been evaluated in several randomized-controlled trials to treat various psychological problems including depression, anxiety, and insomnia ( Dowrick et al., 2000 ; Mynors-Wallis et al., 2000 ).

Problem-Solving Therapy for Primary Care has been demonstrated as an efficacious intervention to improve mood and cognitive functioning in elderly depressed patients ( Alexopoulous et al., 2003 ; Arean et al., 2008 , 2010 ). When compared with other treatment modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic approaches, depressed older adults who were treated with PST-PC reported fewer depressive symptoms and improved functioning at 12 months and up to 24 months follow-up ( Arean et al., 2008 ). Elderly depressed patients receiving PST-PC treatments have exhibited reduction of symptoms, endorsed higher response rate to treatment, and greater remission rate when compared with those receiving a person-centered psychotherapy treatment approach ( Arean et al., 2010 ). Among depressed elderly patients with impairments in aspects of executive functioning, those receiving PST-PC treatments (versus supportive counseling) demonstrated greater improvement in generating alternative solutions and decision-making skills, in addition to reduced depressive symptoms and improved functioning ( Alexopoulous et al., 2003 ).

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether decision-making performance among healthy community-dwelling older adults can be improved by a brief four-session (approximately 2 weeks) problem-solving therapy modality. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to introduce a psychosocial intervention to enhance complex decision-making among healthy community-dwelling older adults in an outpatient context. PST-PC was specifically chosen due to its: 1) efficacy among older adults; 2) efficient protocol that can be delivered in four sessions (or in our case, about 2 weeks); and 3) effectiveness when implemented by trained individuals not in the field of mental health ( Arean, 2009 ). Morever, the cognitive changes associated with aging have demonstrated age-related effects in prefrontal brain structures contributing to weaknesses in aspects of executive functioning (e.g., planning, initiation, decision-making, and problem-solving), and thus the utilization of PST-PC as a possible compensatory strategy to address these deficits can be a valuable form of intervention. It was hypothesized that decision-making performance among healthy community-dwelling older adults would improve for those in the PST-PC condition when compared to participants in the no-treatment Control condition.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

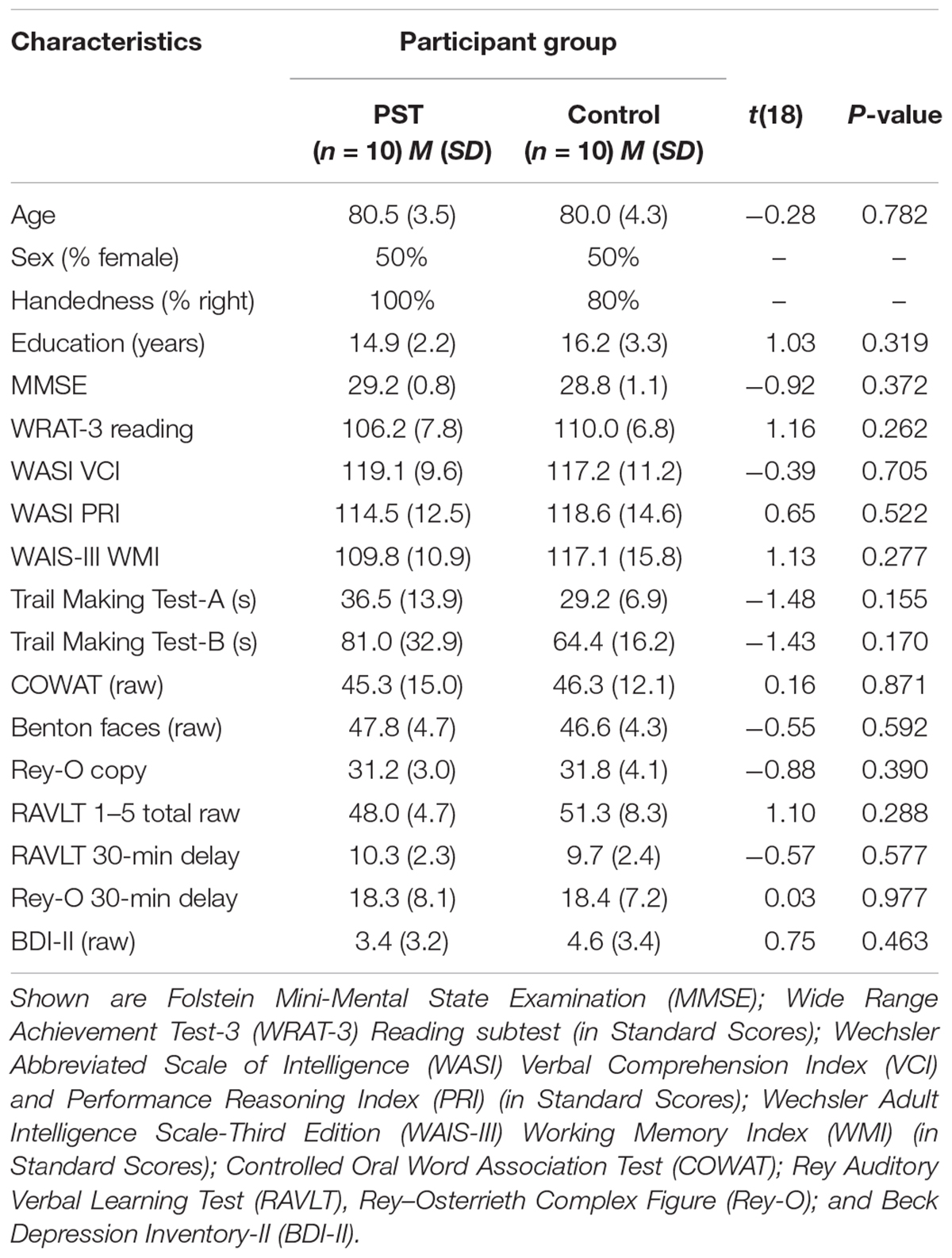

Participants were included in the study if they were heathy, community-dwelling, aged 65 years and older, and cognitively and emotionally intact, and were excluded from the study if they had any major underlying medical conditions (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular disease, and movement disorder). Participants were recruited from a pool of participants involved in an ongoing project investigating the neural correlates of decision-making. These participants were evaluated extensively, with both clinical interview and comprehensive neuropsychological assessment, and thus were deemed cognitively and emotionally intact (after Tranel et al., 1997 ). Participants completed an informed consent process approved by an Institutional Review Board, and were financially compensated for their involvement. Twenty participants were randomly assigned to two groups: psychoeducational condition (PST-PC) and no-treatment Control group. The PST-PC group ( n = 10) had a mean age of 80.5 years [standard deviation (SD) = 3.5] and 50% males. The Control group ( n = 10) had a mean age of 80.0 years ( SD = 4.3) and 50% males.

All participants completed a 2-h comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests to assess a broad range of cognitive abilities. A research assistant with training in neuropsychological assessment administered the test battery under the supervision of a neuropsychologist (NLD). Ten domains were assessed with the following administered instruments: general mental status (Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination; Folstein et al., 1975 ); estimated premorbid IQ (Wide Range Achievement Test-3; Wilkinson, 1993 ); verbal and non-verbal intellectual functioning (Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence; Wechsler, 1999 ); attention and working memory (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III Working Memory Index; Wechsler, 1997 ); processing speed (Trail Making Test Part A; Spreen and Strauss, 1998 ); language (Controlled Oral Word Association Test; Benton and Hamsher, 1989 ); learning and memory [Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test ( Rey, 1941 ) and Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test ( Rey, 1964 )]; visuoperception (Benton Facial Discrimination Test; Benton et al., 1994 ); mental flexibility and set-shifting (Trail Making Test Part B; Spreen and Strauss, 1998 ); and mood (Beck Depression Inventory-II; Beck et al., 1996 ).

Participants randomized into the psychoeducational condition each completed four 45-min sessions of the PST-PC protocol during a 2-week period. A doctoral candidate in psychology (CMN) with training in cognitive-behavioral therapy delivered the PST-PC sessions following a manualized protocol to all participants under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist (NLD). Through a seven-step model of PST-PC ( Hegel and Arean, 2003 ), participants identified problems to be solved; discussed and evaluated different resolutions to reach desired goals; created action plans to accomplish determined goals; and evaluated their effectiveness in resolving designated problems. In the first session, the structure of the treatment process was outlined, and the seven stages of the problem-solving process were thoroughly discussed. In the second session, the participant selected one problem from the list generated in the first session to be resolved. The seven stages of PST-PC were integrated during the process of identifying the problem to be resolved and formation of the action plan. During the third session, participants evaluated the outcomes of their action plans. This session consisted of a discussion on how well they have integrated the seven stages of PST-PC toward the resolution of a designated problem to be resolved. If a participant successfully resolved the problem, a new problem was selected, and the process was discussed in the last session. If a participant was not successful in resolving a designated problem, the next session was used to further discuss progress or setbacks. The final session was used to review the participants’ progress and reinforce continued efforts in resolution of future problems ( Hegel and Arean, 2003 ).

All but one participant completed the PST-PC protocol at our clinic. For this one individual, the sessions were completed at their home due to limited mobility secondary to a recent orthopedic surgery. There was a 3- to 4-day interval between each of the four sessions. Participants were scheduled to complete the outcome measure within 3 days of completing the final PST-PC session. The participants from the Control group were recruited and scheduled to complete the outcome measure.

Manipulation Check

A manipulation check was applied to confirm that the seven stages of the PST-PC protocol was successfully implemented. At baseline and post-PST-PC sessions, participants were asked to respond to one open-ended essay-format question, as follows: “Please describe the process of problem-solving in detail, including all steps and the criteria for successfully completing each one.” All essays were scored using criteria designated in the 20-item Problem-Solving Treatment Knowledge Assessment (PST-KA; Cartreine et al., 2012 ), based on how well each essay discussed the stages of Problem-Solving Treatment (e.g., Identifying the Problem, Setting a Goal, Brainstorming Solutions, Selecting Solutions for Implementation, and Action Planning). Each item on the PST-KA was rated on a six-point scale (0–5; very poor to very good). The possible range of scores was 0–100, with higher scores indicating greater baseline knowledge/knowledge obtained (hereafter refered to as closure knowledge). Two research assistants who were blind to the time point of the completed essays completed the ratings. An average score was calculated across scores from the research assistants.

Decision-Making Outcome Measure

The Iowa Gambling Task (IGT; Bechara, 2007 ) is a measure of complex decision-making under ambiguity that features real-world aspects of reward, punishment, and unpredictability. The IGT is a computer-administered test comprised of 100 card selections from four decks of cards. On each trial, choosing a card gives an immediate monetary reward. At random points, the selection of some cards results in losing a sum of money. Two decks of cards are predetermined to offer a lower immediate gain and even lower long-term loss, yielding an overall net gain of money (i.e., referred to as “the good decks”). Alternatively, the other two decks are predetermined to offer a higher immediate gain but even higher long-term loss, yielding an overall net loss of money (i.e., referred to as “the bad decks”). Participants are not informed of the number of trials or the gain/loss patterns.

Performance on the IGT is often quantified by dividing the 100 trials into five distinct blocks of 20 trials each to examine participant’s learning curve ( Bechara, 2007 ). A score for each block is calculated by subtracting the number of selection from the good decks from the number of selections from the bad decks, while a total score for the IGT is calculated by subtracting the total number of selections from the bad decks from the total number of selections from the good deck. A positive total score indicates advantageous decision-making, whereas a negative total score indicates disadvantageous decision-making ( Bechara, 2007 ).

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary analysis examined the data for the presence of outliers. Independent samples t -tests were employed to examine differences between the participant groups on demographic variables, cognitive performance, and mood. Next, a paired-samples t -test was conducted to examine whether a mean difference existed in baseline and/or closure knowledge after four sessions of PST-PC. Finally, to explore the effects of PST-PC on the decision-making outcome measure, a 2x5 repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) using group status (PST-PC versus Control) as the between-subjects factor and trial block (1–5) as the within-subjects factor was employed to evaluate performance on the IGT outcome measure by trial block.

The two participant groups did not significantly differ in terms of education, general mental status, estimated premorbid IQ, verbal and non-verbal intellectual functioning, attention and working memory, processing speed, language, learning and memory, visuoperception, mental flexibility and set-shifting, and mood. Demographic and cognitive characteristics are presented in Table 1 . A paired-samples t -test comparing pre- and post-intervention PST-KA scores of participants from the PST-PC group revealed a significant difference in the baseline knowledge assessment scores ( M = 22.0; SD = 13.3) as compared to the closure knowledge scores ( M = 38.8, SD = 19.6); t (9) = -2.3, p = 0.047. This implied that the seven stages of the PST-PC protocol was successfully implemented. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed a non-significant main effect for group on IGT scores, F (4,15) = 2.04, p = 0.097. Although there were no significant group differences with the overall IGT index, descriptive statistics revealed that four (of 10) participants in the Control group achieved an overall index in IGT scores that were below zero (range: -16 to -44), as compared to none from the PST group. Of note, IGT scores that were significantly below zero have been classified as an “Impaired” performance in past studies ( Denburg et al., 2005 ). A significant interaction effect was indicated between group status and the trajectory of score differences across the five trial blocks on the IGT, F (4,15) = 3.24, p = 0.017, which is indicative that group status had different effects on participant’s learning curve on the IGT trials, as presented in Figure 1 . To explore this interaction, contrasts were performed for individual trial blocks, revealing a statistically significant difference between the two groups in advantages versus disadvantageous selections on the last block of the IGT, t (18) = -3.02, p = 0.007, d = 1.35, 95% CI [-22, -4]. Particularly, as the task progressed to the end, participants in the PST-PC group significantly outperformed participants in the Control group in terms of making more advantageous decisions in the last 20% of trials (or card selections 81–100).

TABLE 1. Demographic and cognitive characteristics.

FIGURE 1. Iowa Gambling Task scores by trail block for PST-PC and Control groups. Decision-making performance on the IGT in PST-PC and Control participants, graphed as a function of trial block [±SEM (standard error of the mean)]. A significant interaction effect was indicated between group status and the trajectory of score differences across the five trial blocks on the IGT, revealing a statistically significant difference between the two groups in advantageous versus disadvantageous selections on the last block of the IGT, or during the last 20% of selections.

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether decision-making performance among healthy community-dwelling older adults could be improved as a result of a well-validated psychoeducational intervention. Twenty participants were recruited and randomized into two conditions: PST-PC and a no-treatment Control group. The theoretical framework of this study is based on a body of literature suggesting that a disproportionate deterioration of the frontal lobes during aging contributes to a decline in executive functioning abilities among some older adults ( West, 1996 ). Previous work from our laboratory have supported this “frontal lobe hypothesis,” revealing that seemingly healthy older adults often make disadvantageous decisions ( Denburg et al., 2005 , 2006 , 2007 ). Specifically, we have found that some older adults may experience a greater decline in non-memory-related cognitive functioning, such as problem-solving and mental flexibility, contributing to weaknesses in their decision-making abilities ( Denburg and Hedgcock, 2015 ). The findings from the current study demonstrated that a four-session (approximately 2 weeks) problem-solving therapy can reinforce aspects of executive functioning (that may have declined as a part of healthy aging), thereby enhancing decision-making abilities.

With regard to decision-making outcomes, the proportion of our participants with “impaired” and “unimpaired” performance on the IGT from the Control group is comparable to findings from previous studies using this classification. Specifically, Denburg et al. (2005 , 2006 ) defined “impaired” performance on the IGT as being significantly worse than performance at chance level, and found that approximately 25–35% of their older adult sample performed in the “impaired” range. Additionally, this finding is consistent with another study suggesting that a subset of older adults make less advantageous decisions when compared to younger adults ( Fein et al., 2007 ).

Interestingly, earlier findings by Bechara et al. (1997) have indicated that by the 80th card selection (out of 100), normal healthy young adults would reach a “conceptual period” during which they exhibited knowledge regarding optimal choices based on prior feedback and typically avoid the disadvantage selections. Notably, as the task progressed to the latter 20% of the task, participants in the PST-PC group significantly outperformed participants in the Control group in terms of making more advantageous decisions. Group differences emerged as the IGT progressed such that those in the PST-PC group learned to adapt to feedback that led to making more advantageous decisions. Alternatively, participants without the benefit of the PST-PC psychoeducation treatment (i.e., the Control group) shifted between decks and were inefficient in developing a strategy over time which may have contributed to the overall less advantageous choices than participants in the PST-PC group.

It has been postulated that individuals exhibiting difficulty in developing an advantageous and stable strategy over time on the IGT is likely to be related to weaknesses in aspects of executive functioning ( Okdie et al., 2016 ). Furthermore, an inflexibility in responding to negative feedback after a disadvantageous decision has been postulated to be related to poor executive functioning, which results in an individual being less likely to adapt to the feedback to choose more advantageous options ( Zamarian et al., 2008 ). The findings from this study suggests that PST-PC may be effective in generating an efficient learning process that contributes to advantageous decision-making outcomes.

The components taught during the various PST-PC sessions provide an opportunity for the individual to broadly strengthen executive skills referenced by Lezak et al. (2012) , such as emotional regulation, behavioral initiation, planning, organization, cognitive flexibility, and problem-solving. A person with weaknesses in executive dysfunction can be overwhelmed with complex tasks and situations, which can be remediated during the initial stages of PST-PC through a structured approach to problem solving (e.g., breaking down complex problems into small and manageable parts). Cognitive flexibility is facilitated during the brainstorming stages of PST-PC, where individuals are encouraged to generate multiple solutions toward a satisfactory resolution of a problem. Aspects of executive functioning such as planning and organization are facilitated during the middle phases of PST-PC, where individuals evaluate and compare solutions generated during the brainstorming step to determine the best selection to be implemented. Behavioral initiation is fostered through the development of an action plan during the later steps of PST-PC. Overall, the process of implementing the stages of PST-PC requires abstract problem-solving with inductive reasoning and flexible adjustment of responses based on feedback, and may have contributed to improved decision-making outcomes.

A psychoeducational approach such as PST-PC can contribute to increased self-efficacy among older adults and improve decision-making abilities. To illustrate, it has been suggested that interventions can be more efficacious when integrating older adults’ strengths, such as their life experiences, to increase self-efficacy (e.g., positivity, confidence, and motivation) ( Strough et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, to improve their sense of self-efficacy, individuals must be engaged in an activation process that facilitates the examination of his/her knowledge, skills, and confidence with respect to the relevant topic requiring a decision to be made, and then formulating a concrete action plan to be implemented ( Hibbard and Mahoney, 2010 ). The latter stages of PST-PC evoked this process, when participants were asked to evaluate and compare solutions generated through brainstorming, and to determine the best selection to be implemented as an action plan. Furthermore, solicited feedback from the participants revealed that the psychoeducational component of PST-PC provided during the initial sessions solidified and enhanced preexisting knowledge and approaches to problem-solving (i.e., promoting self-efficacy from life experiences), in addition to providing a structured approach to facilitate a more efficient process for resolving practical everyday challenges.

This is one of the first studies to adapt PST-PC for use as an intervention to enhance decision-making in healthy community-dwelling older adults. By contrast, much of the extant literature in facilitation of advantageous decision-making outcomes relies extensively on the use of decision aids, or interventions designed to assist in the deliberation between treatment options by provided content-related information (e.g., health-related information when choosing between medical treatment options) ( Stacey et al., 2014 ). While these decision aids have been found to be effective in increasing knowledge and risk perception as well as contributing to a more well-informed decision-making process, few studies have explicitly examined its effectiveness among older adults ( van Weert et al., 2016 ). Incidentally, a majority of participants in this study readily identified a common health-related theme (e.g., weight loss, managing high cholesterol, improving sleep hygiene, and managing chronic pain) when asked to identify a problem to be applied during the PST-PC protocol. Perhaps this is suggestive that PST-PC can be utilize as a modality to facilitate more active participation (as compared to decision aids) among older adults in enhancing aspects of complex decision-making processes in the healthcare arena.

This study is not without its limitations. Participants in our study were highly educated (e.g., 70% with 16 years of education and above) for an older adult sample and performed in the high average range on measures of general intellectual functioning. By contrast, the 2015 Census data reported that only 27% of the population 65 years of age and older had earned a bachelor’s degree or more ( He et al., 2005 ). Finally, the present study had a relatively small sample size and was homogenous in terms of race (i.e., all participants were non-Hispanic, white). These issues may limit the generalizability of our findings. Another limitation of the study is the utilization of a single laboratory measure of decision making. While the IGT has been a well-validated measure to detect decision-making deficits ( Bechara, 2007 ), decision-making is complex and multifaceted, and undoubtedly difficult to measure fully with any laboratory task. Future studies should validate the efficacy of PST-PC in enhancing decision-making outcomes among older adults in other applied tasks such as the Multiple Errands test ( Tranel et al., 2007 ) or the Financial Decision-Making test ( Shivapour et al., 2012 ).

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the approval of University of Iowa Institutional Review Board with written informed consent from all subjects.

Author Contributions

CMN and NLD: study concept, design, analysis, data interpretation, manuscript writing, data verification, and analysis. K-HC: study design.

This study was funded by American Psychological Association Science Directorate’s Dissertation Research Award to CMN.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer GD and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Alexopoulous, G. S., Raue, P., and Arean, P. (2003). Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. Am. J. Geriat. Psychiatry 11, 46–52. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200301000-00007

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arean, P., Hegel, M., Vannoy, S., Fan, M. Y., and Unuzter, J. (2008). Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist 48, 311–323. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.3.311

Arean, P. A. (2009). Problem-solving therapy. Psychiatr. Ann. 39, 854–862. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20090821-01

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arean, P. A., Raue, P., Mackin, R. S., Kanellopoulous, D., McCulloch, C., and Alexopoulous, G. S. (2010). Problem-solving therapy and supportive treatment in older adults with major depression and executive dysfunction. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 1391–1398. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.177

Bechara, A. (2007). Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) Professional Manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., and Damasio, A. R. (1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing the advantageous strategy. Science 275, 1293–1295. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1293

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., and Brown, G. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory II: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation.

Google Scholar

Benton, A. L., and Hamsher, K. (1989). Multilingual Aphasia Examination. Iowa, IA: AJA Associates.

Benton, A. L., Sivan, A. B., Hamsher, K., Varney, N. R., and Spreen, O. (1994). Contributions to Neuropsychological Assessment: A Clinical Manual , 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Carpenter, S. M., and Yoon, C. (2015). “Aging and consumer decision making,” in Aging and Decision Making: Empirical and Applied Perspectives , eds T. M. Hess, J. Strough, and C. E. Lockenhoff (New York, NY: Academic Press), 351–371.

Cartreine, J. A., Chang, T. E., Seville, J. L., Sandoval, L., Moore, J. B., Xu, S., et al. (2012). Using self-guided treatment software (ePST) to teach clinicians how to deliver problem-solving treatment for depression. Depress. Res. Treat. 2012:309094. doi: 10.1155/2012/309094

Denburg, N. L., and Hedgcock, W. M. (2015). “Age-associated executive dysfunction, the prefrontal cortex, and complex decision making,” in Aging and Decision Making: Empirical and Applied Perspectives , eds T. M. Hess, J. Strough, and C. E. Lockenhoff (New York, NY: Academic Press), 81–104.

Denburg, N. L., Cole, C. A., Hernandez, M., Yamada, T. H., Tranel, D., Bechara, A., et al. (2007). The orbitofrontal cortex, real-world decision making, and normal aging. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1121, 480–498. doi: 10.1196/annals.1401.031

Denburg, N. L., Recknor, E. C., Bechara, A., and Tranel, D. (2006). Psychophysiological anticipation of positive outcomes promotes advantageous decision-making in normal older persons. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 61, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.021

Denburg, N. L., Tranel, D., and Bechara, A. (2005). The ability to decide advantageously declines prematurely in some normal older persons. Neuropsychologia 43, 1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.09.012

Dowrick, C., Dunn, G., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Dalgard, O. S., Page, H., Lehtinen, V., et al. (2000). Problem solving treatment and group psychoeducation for depression: multicentre randomized controlled trial. Br. Med. J. 321, 1–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1450

Fein, G., McGillivray, S., and Finn, P. (2007). Older adults make less advantageous decisions than younger adults: cognitive and psychological correlates. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 13, 480–489. doi: 10.1017/S135561770707052X