The Great Gatsby

F. scott fitzgerald, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

| Summary & Analysis |

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

The Great Gatsby

By f. scott fitzgerald, the great gatsby summary and analysis of chapter 8, chapter eight.

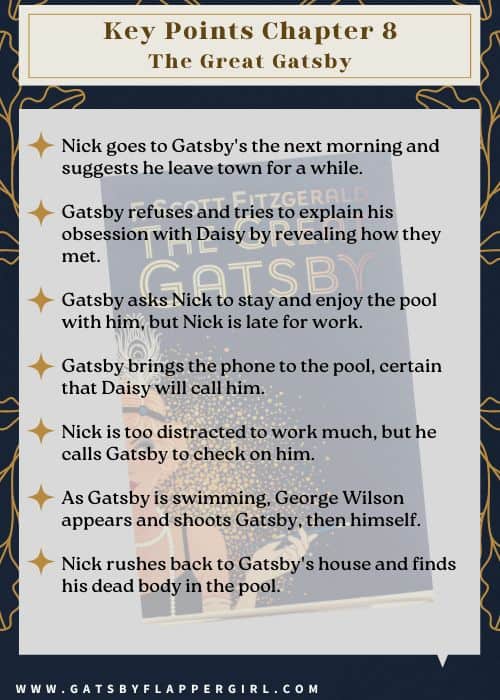

That night, Nick finds himself unable to sleep, since the terrible events of the day have greatly unsettled him. Wracked by anxiety, he hurries to Gatsby's mansion shortly before dawn. He advises Gatsby to leave Long Island until the scandal of Myrtle's death has quieted down. Gatsby refuses, as he cannot bring himself to leave Daisy: he tells Nick that he spent the entire night in front of the Buchanans' mansion, just to ensure that Daisy was safe. He tells Nick that Tom did not try to harm her, and that Daisy did not come out to meet him, though he was standing on her lawn in full moonlight.

Gatsby, in his misery, tells Nick the story of his first meeting with Daisy. He does so even though it patently gives the lie to his earlier account of his past. Gatsby and Daisy first met in Louisville in 1917; Gatsby was instantly smitten with her wealth, her beauty, and her youthful innocence. Realizing that Daisy would spurn him if she knew of his poverty, Gatsby determined to lie to her about his past and his circumstances. Before he left for the war, Daisy promised to wait for him; the two then slept together, as though to seal their pact. Of course, Daisy did not wait; she married Tom, who was her social equal and the choice of her parents.

Realizing that it has grown late, Nick says goodbye to Gatsby. As he is walking away, he turns back and shouts that Gatsby is "worth the whole damn bunch [of the Buchanans and their East Egg friends] put together."

The scene shifts from West Egg to the valley of ashes, where George Wilson has sought refuge with Michaelis . It is from the latter that Nick later learns what happened in the aftermath of Myrtle's death. George Wilson tells Michaelis that he confronted Myrtle with the evidence of her affair and told her that, although she could conceal her sin from her husband, she could not hide it from the eyes of God. As the sun rises over the valley of ashes, Wilson is suddenly transfixed by the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg; he mistakes them for the eyes of God. Wilson assumes that the driver of the fatal car was Myrtle's lover, and decides to punish this man for his sins.

He seeks out Tom Buchanan , in the hope that Tom will know the driver's identity. Tom tells him that Gatsby was the driver. Wilson drives to Gatsby's mansion; there, he finds Gatsby floating in his pool, staring contemplatively at the sky. Wilson shoots Gatsby, and then turns the gun on himself.

It is Nick who finds Gatsby's body. He reflects that Gatsby died utterly disillusioned, having lost, in rapid succession, his lover and his dreams.

Nick gives the novel's final appraisal of Gatsby when he asserts that Gatsby is "worth the whole damn bunch of them." Despite the ambivalence he feels toward Gatsby's criminal past and nouveau riche affectations, Nick cannot help but admire him for his essential nobility. Though he disapproved of Gatsby "from beginning to end," Nick is still able to recognize him as a visionary, a man capable of grand passion and great dreams. He represents an ideal that had grown exceedingly rare in the 1920s, which Nick (along with Fitzgerald) regards as an age of cynicism, decadence, and cruelty.

Nick, in his reflections on Gatsby's life, suggests that Gatsby's great mistake was loving Daisy. He chose an inferior object upon which to focus his almost mystical capacity for dreaming. Just as the American Dream itself has degenerated into the crass pursuit of material wealth, Gatsby, too, strived only for wealth once he had fallen in love with Daisy, whose trivial, limited imagination could conceive of nothing greater. It is significant that Gatsby is not murdered for his criminal connections, but rather for his unswerving devotion to Daisy. As Nick writes, Gatsby thus "[pays] a high price for living too long with a single dream."

Up to the moment of his death, Gatsby cannot accept that his dream is over: he continues to insist that Daisy may still come to him, though it is clear to everyone, including the reader, that she is bound indissolubly to Tom. Gatsby's death thus seems almost inevitable, given that a dreamer cannot exist without his dreams; through Daisy's betrayal, he effectively loses his reason for living.

Wilson seems to be Gatsby's grim double in Chapter VIII, and represents the more menacing aspects of a capacity for visionary dreaming. Like Gatsby, he fundamentally alters the course of his life by attaching symbolic significance to something that is, in and of itself, meaningless. For Gatsby, it is Daisy and her green light, for Wilson, it is the eyes of Dr. T.J. Eckleburg. Both men are destroyed by their love of women who love the brutal Tom Buchanan; both are consumed with longing for something greater than themselves. While Gatsby is a "successful" American dreamer (at least insofar as he has realized his dreams of wealth), Wilson exemplifies the fate of the failed dreamer, whose poverty has deprived him of even his ability to hope.

Gatsby's death takes place on the first day of autumn, when a chill has begun to creep into the air. His decision to use his pool is in defiance of the change of seasons, and represents yet another instance of Gatsby's unwillingness to accept the passage of time. The summer is, for him, equivalent to his reunion with Daisy; the end of the summer heralds the end of their romance.

The Great Gatsby Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Great Gatsby is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

describe daisy and gatsby's new relationship

There are two points at which Daisy and Gatsby's relationship could be considered "new". First, it seems that their "new" relationship occurs as Tom has become enlightened about their affair. It seems as if they are happy...

Describe Daisy and Gatsby new relationship?

http://www.gradesaver.com/the-great-gatsby/q-and-a/describe-daisy-and-gatsbys-new-relationship-70077/

What are some quotes in chapter 1 of the great gatsby that show the theme of violence?

I don't recall any violence in in chapter 1.

Study Guide for The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby is typically considered F. Scott Fitzgerald's greatest novel. The Great Gatsby study guide contains a biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Great Gatsby

- The Great Gatsby Summary

- The Great Gatsby Video

- Character List

Essays for The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

- Foreshadowing Destiny

- The Eulogy of a Dream

- Materialism Portrayed By Cars in The Great Gatsby

- Role of Narration in The Great Gatsby

- A Great American Dream

Lesson Plan for The Great Gatsby

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to The Great Gatsby

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- The Great Gatsby Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for The Great Gatsby

- Introduction

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

Best Summary and Analysis: The Great Gatsby, Chapter 8

Book Guides

In Great Gatsby Chapter 8, things go from very bad to much, much worse. There’s an elegiac tone to half of the story in Chapter 8, as Nick tells us about Gatsby giving up on his dreams of Daisy and reminiscing about his time with her five years before. The other half of the chapter is all police thriller, as we hear Michaelis describe Wilson coming unglued and deciding to take bloody revenge for Myrtle’s death.

Get ready for bittersweetness and gory shock, in this The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 summary.

Quick Note on Our Citations

Our citation format in this guide is (chapter.paragraph). We're using this system since there are many editions of Gatsby, so using page numbers would only work for students with our copy of the book. To find a quotation we cite via chapter and paragraph in your book, you can either eyeball it (Paragraph 1-50: beginning of chapter; 50-100: middle of chapter; 100-on: end of chapter), or use the search function if you're using an online or eReader version of the text.

The Great Gatsby: Chapter 8 Summary

That night Nick has trouble sleeping. He feels like he needs to warn Gatsby about something.

When he meets up with Gatsby at dawn, Gatsby tells Nick nothing happened outside Daisy’s house all night. Gatsby’s house feels strangely enormous. It’s also poorly kept - dusty, unaired, and unusually dark.

Nick advises Gatsby to lay low somewhere else so that his car isn’t found and linked to the accident. But Gatsby is unwilling to leave his lingering hopes for Daisy. Instead, Gatsby tells Nick about his background - the information Nick told us in Chapter 6 .

Gatsby's narrative begins with the description of Daisy as the first wealthy, upper-class girl Gatsby had ever met. He loved her huge beautiful house and the fact that many men had loved her before him. All of this made him see her as a prize.

He knew that since he was poor, he shouldn’t really have been wooing her, but he slept with her anyway, under the false pretenses that he and she were in the same social class.

Gatsby realized that he was in love with Daisy and was surprised to see that Daisy fell in love with him too. They were together for a month before Gatsby had to leave for the war in Europe. He was successful in the army, becoming a major. After the war he ended up at Oxford, unable to return to Daisy.

Meanwhile, Daisy re-entered the normal rhythm of life: lavish living, snobbery, lots of dates, and all-night parties. Gatsby sensed from her letters that she was annoyed at having to wait for him, and instead wanted to finalize what her life would be like. The person who finalized her life in a practical way that made sense was Tom.

Gatsby interrupts his narrative to again say that there’s no way that Daisy ever loved Tom - well, maybe for a second right after the wedding, tops, but that’s it.

Then he goes back to his story, which concludes after Daisy's wedding to Tom. When Gatsby came back from Oxford, Daisy and Tom were still on their honeymoon. Gatsby felt like the best thing in his life had disappeared forever.

After breakfast, Gatsby’s gardener suggests draining the pool, but Gatsby wants to keep it filled since he hasn’t yet used it.

Gatsby still hopes that Daisy will call him.

Nick thanks Gatsby for the hospitality, pays him the backhanded compliment of saying that he is better than the “rotten crowd” of upper-class people (backhanded because it's setting the bar pretty low to be better than "rotten" people), and leaves to go to work.

At work, Nick gets a phone call from Jordan, who is upset that Nick didn’t pay sufficient attention to her the night before. Nick is floored by this selfishness - after all, someone died, so how could Jordan be so self-involved! They hang up on each other, clearly broken up.

Nick tries to call Gatsby, but is told by the operator that the line is being kept free for a phone call from Detroit (which might actually be Gatsby's way of clearing the line in case Daisy calls? It's unclear). On the way back from the city, Nick purposefully sits on the side of the train car that won’t face Wilson’s garage.

Nick now tells us what happened at the garage after he, Tom, and Jordan drove away the day before. Since he wasn't there, he's most likely recapping Michaelis's inquest statement.

They found Myrtle’s sister too drunk to understand what had happened to Myrtle. Then she fainted and had to be taken away.

Michaelis sat with Wilson until dawn, listening to Wilson talk about the yellow car that had run Myrtle over, and how to find it. Michaelis suggested that Wilson talk to a priest, but Wilson showed Michaelis an expensive dog leash that he found. To him, this was incontrovertible proof of her affair and the fact that her lover killed Myrtle on purpose.

Wilson said that Myrtle was trying to run out to talk to the man in the car, while Michaelis believed that she had been trying to flee the house where Wilson had locked her up. Wilson had told Myrtle that God could see everything she was doing. The God he’s talking about? The eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg on the billboard near the garage.

Wilson seemed calm, so Michaelis went home to sleep. By the time he came back to the garage, Wilson was gone. Wilson walked all the way to West Egg, asking about the yellow car.

That afternoon, Gatsby gets in his pool for the first time that summer. He is still waiting for a call from Daisy. Nick tries to imagine what it must have been like to be Gatsby and know that your dream was lost.

Gatsby’s chauffeur hears gunshots just as Nick pulls up to the house. In the pool, they see Gatsby’s dead body, and a little way off in the grass, they see Wilson’s body. Wilson has shot Gatsby and then himself.

Key Chapter 8 Quotes

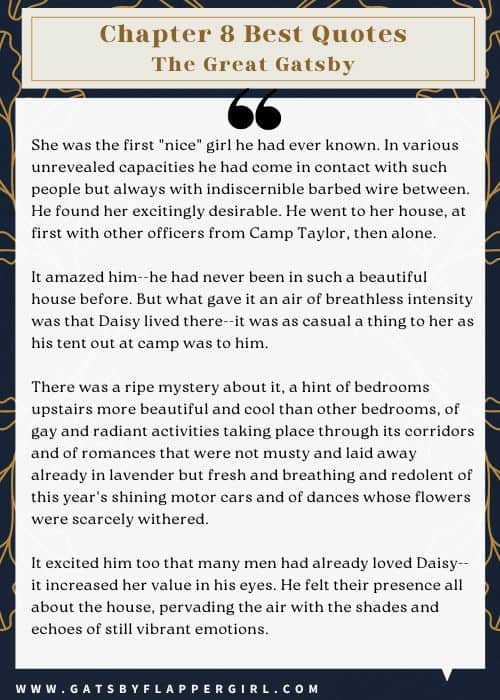

She was the first "nice" girl he had ever known. In various unrevealed capacities he had come in contact with such people but always with indiscernible barbed wire between. He found her excitingly desirable. He went to her house, at first with other officers from Camp Taylor, then alone. It amazed him--he had never been in such a beautiful house before. But what gave it an air of breathless intensity was that Daisy lived there--it was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him. There was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year's shining motor cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered. It excited him too that many men had already loved Daisy--it increased her value in his eyes. He felt their presence all about the house, pervading the air with the shades and echoes of still vibrant emotions. (8.10)

The reason the word “nice” is in quotation marks is that Gatsby does not mean that Daisy is the first pleasant or amiable girl that he has met. Instead, the word “nice” here means refined, having elegant and elevated taste, picky and fastidious. In other words, from the very beginning what Gatsby most values about Daisy is that she belongs to that set of society that he is desperately trying to get into: the wealthy, upper echelon. Just like when he noted the Daisy’s voice has money in it, here Gatsby almost cannot separate Daisy herself from the beautiful house that he falls in love with.

Notice also how much he values quantity of any kind – it’s wonderful that the house has many bedrooms and corridors, and it’s also wonderful that many men want Daisy. Either way, it’s the quantity itself that “increases value.” It’s almost like Gatsby’s love is operating in a market economy – the more demand there is for a particular good, the higher the worth of that good. Of course, thinking in this way makes it easy to understand why Gatsby is able to discard Daisy’s humanity and inner life when he idealizes her.

For Daisy was young and her artificial world was redolent of orchids and pleasant, cheerful snobbery and orchestras which set the rhythm of the year, summing up the sadness and suggestiveness of life in new tunes. All night the saxophones wailed the hopeless comment of the "Beale Street Blues" while a hundred pairs of golden and silver slippers shuffled the shining dust. At the grey tea hour there were always rooms that throbbed incessantly with this low sweet fever, while fresh faces drifted here and there like rose petals blown by the sad horns around the floor.

Through this twilight universe Daisy began to move again with the season; suddenly she was again keeping half a dozen dates a day with half a dozen men and drowsing asleep at dawn with the beads and chiffon of an evening dress tangled among dying orchids on the floor beside her bed. And all the time something within her was crying for a decision. She wanted her life shaped now, immediately - and the decision must be made by some force - of love, of money, of unquestionable practicality - that was close at hand. (8.18-19)

This description of Daisy’s life apart from Gatsby clarifies why she picks Tom in the end and goes back to her hopeless ennui and passive boredom: this is what she has grown up doing and is used to. Daisy’s life seems fancy. After all, there are orchids and orchestras and golden shoes.

But already, even for the young people of high society, death and decay loom large . In this passage for example, not only is the orchestra’s rhythm full of sadness, but the orchids are dying, and the people themselves look like flowers past their prime. In the midst of this stagnation, Daisy longs for stability, financial security, and routine. Tom offered that then, and he continues to offer it now.

"Of course she might have loved him, just for a minute, when they were first married--and loved me more even then, do you see?"

Suddenly he came out with a curious remark:

"In any case," he said, "it was just personal."

What could you make of that, except to suspect some intensity in his conception of the affair that couldn't be measured? (8.24-27)

Even though he can now no longer be an absolutist about Daisy’s love, Gatsby is still trying to think about her feelings on his own terms . After admitting that the fact that many men loved Daisy before him is a positive, Gatsby is willing to admit that maybe Daisy had feelings for Tom after all, just as long as her love for Gatsby was supreme.

Gatsby is ambiguous admission that “it was just personal” carries several potential meanings:

- Nick assumes that the word “it” refers to Gatsby’s love, which Gatsby is describing as “personal” as a way of emphasizing how deep and inexplicable his feelings for Daisy are.

- But of course, the word “it” could just as easily be referring to Daisy’s decision to marry Tom. In this case, what is “personal” are Daisy’s reasons (the desire for status and money), which are hers alone, and have no bearing on the love that she and Gatsby feel for each other.

He stretched out his hand desperately as if to snatch only a wisp of air, to save a fragment of the spot that she had made lovely for him. But it was all going by too fast now for his blurred eyes and he knew that he had lost that part of it, the freshest and the best, forever. (8.30)

Once again Gatsby is trying to reach something that is just out of grasp , a gestural motif that recurs frequently in this novel. Here already, even as a young man, he is trying to grab hold of an ephemeral memory.

"They're a rotten crowd," I shouted across the lawn. "You're worth the whole damn bunch put together."

I've always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we'd been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of color against the white steps and I thought of the night when I first came to his ancestral home three months before. The lawn and drive had been crowded with the faces of those who guessed at his corruption--and he had stood on those steps, concealing his incorruptible dream, as he waved them goodbye. (8.45-46)

It’s interesting that here Nick suddenly tells us that he disapproves of Gatsby. One way to interpret this is that during that fateful summer, Nick did indeed disapprove of what he saw, but has since come to admire and respect Gatsby , and it is that respect and admiration that come through in the way he tells the story most of the time.

It’s also telling that Nick sees the comment he makes to Gatsby as a compliment. At best, it is a backhanded one – he is saying that Gatsby is better than a rotten crowd, but that is a bar set very low (if you think about it, it’s like saying “you’re so much smarter than that chipmunk!” and calling that high praise). Nick’s description of Gatsby’s outfit as both “gorgeous” and a “rag” underscores this sense of condescension. The reason Nick thinks that he is praising Gatsby by saying this is that suddenly, in this moment, Nick is able to look past his deeply and sincerely held snobbery, and to admit that Jordan, Tom, and Daisy are all horrible people despite being upper crust.

Still, backhanded as it is, this compliment also meant to genuinely make Gatsby feel a bit better. Since Gatsby cares so, so much about entering the old money world, it makes Nick glad to be able to tell Gatsby that he is so much better than the crowd he's desperate to join.

Usually her voice came over the wire as something fresh and cool as if a divot from a green golf links had come sailing in at the office window but this morning it seemed harsh and dry.

"I've left Daisy's house," she said. "I'm at Hempstead and I'm going down to Southampton this afternoon."

Probably it had been tactful to leave Daisy's house, but the act annoyed me and her next remark made me rigid.

"You weren't so nice to me last night."

"How could it have mattered then?" (8.49-53)

Jordan’s pragmatic opportunism , which has so far been a positive foil to Daisy’s listless inactivity , is suddenly revealed to be an amoral and self-involved way of going through life . Instead of being affected one way or another by Myrtle’s horrible death, Jordan’s takeaway from the previous day is that Nick simply wasn’t as attentive to her as she would like.

Nick is staggered by the revelation that the cool aloofness that he liked so much throughout the summer - possibly because it was a nice contrast to the girl back home that Nick thought was overly attached to their non-engagement - is not actually an act. Jordan really doesn’t care about other people, and she really can just shrug off seeing Myrtle’s mutilated corpse and focus on whether Nick was treating her right. Nick, who has been trying to assimilate this kind of thinking all summer long, finds himself shocked back into his Middle West morality here.

"I spoke to her," he muttered, after a long silence. "I told her she might fool me but she couldn't fool God. I took her to the window--" With an effort he got up and walked to the rear window and leaned with his face pressed against it, "--and I said 'God knows what you've been doing, everything you've been doing. You may fool me but you can't fool God!' "

Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night.

"God sees everything," repeated Wilson.

"That's an advertisement," Michaelis assured him. Something made him turn away from the window and look back into the room. But Wilson stood there a long time, his face close to the window pane, nodding into the twilight. (8.102-105)

Clearly Wilson has been psychologically shaken first by Myrtle’s affair and then by her death - he is seeing the giant eyes of the optometrist billboard as a stand-in for God. But this delusion underlines the absence of any higher power in the novel. In the lawless, materialistic East, there is no moral center which could rein in people’s darker, immoral impulses. The motif of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg’s eyes runs through the novel, as Nick notes them watching whatever goes on in the ashheaps . Here, that motif comes to a crescendo. Arguably, when Michaelis dispels Wilson’s delusion about the eyes, he takes away the final barrier to Wilson’s unhinged revenge plot. If there is no moral authority watching, anything goes.

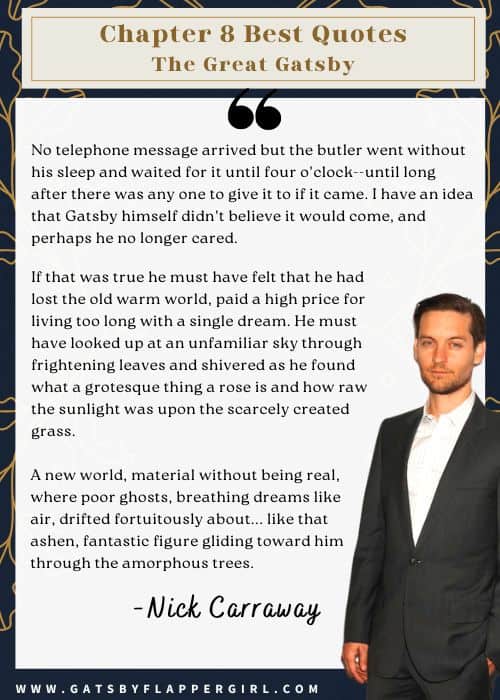

No telephone message arrived but the butler went without his sleep and waited for it until four o'clock--until long after there was any one to give it to if it came. I have an idea that Gatsby himself didn't believe it would come and perhaps he no longer cared. If that was true he must have felt that he had lost the old warm world, paid a high price for living too long with a single dream. He must have looked up at an unfamiliar sky through frightening leaves and shivered as he found what a grotesque thing a rose is and how raw the sunlight was upon the scarcely created grass. A new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about . . . like that ashen, fantastic figure gliding toward him through the amorphous trees. (8.110)

Nick tries to imagine what it might be like to be Gatsby, but a Gatsby without the activating dream that has spurred him throughout his life . For Nick, this would be the loss of the aesthetic sense - an inability to perceive beauty in roses or sunlight. The idea of fall as a new, but horrifying, world of ghosts and unreal material contrasts nicely with Jordan’s earlier idea that fall brings with it rebirth .

For Jordan, fall is a time of reinvention and possibility - but for Gatsby, it is literally the season of death.

The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Analysis

Now let's comb through this chapter to tease apart the themes that connect it to the rest of the novel.

Themes and Symbols

Unreliable Narrator. However much Nick has been backgrounding himself as a narrative force in the novel, in this chapter, we suddenly start to feel the heavy hand of his narration . Rather than the completely objective, nonjudgmental reporter that he has set out to be, Nick begins to edit and editorialize. First, he introduces a sense of foreboding, foreshadowing Gatsby’s death with bad dreams and ominous dread. Then, he talks about his decision to reveal Gatsby’s background not in the chronological order when he learned it, but before we heard about the argument in the hotel room.

The novel is a long eulogy for a man Nick found himself admiring despite many reasons not to, so this choice to contextualize and mitigate Tom’s revelations by giving Gatsby the chance to provide context makes perfect sense. However, it calls into question Nick’s version of events, and his interpretation of the motivations of the people around him. He is a fundamentally unreliable narrator.

Symbols: The Eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg . The absence of a church or religious figure in Wilson’s life, and his delusion that the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg are a higher power, underscores how little moral clarity or prescription there is in the novel’s world . Characters are driven by emotional or material greed, by selfishness, and by a complete lack of concern about others. The people who thrive - from Wolfshiem to Jordan - do so because they are moral relativists. The people who fail - like Nick, or Gatsby, or Wilson - fail because they can’t put aside an absolutist ideal that drives their actions.

The American Dream . Remember discussing variously described ambition in Chapter 6 , when we saw a bunch of people on the make in different ways? In this chapter, that sense of forward momentum recurs, but in a twisted and darkly satiric way through the Terminator-like drive of Wilson to find the yellow car and its driver. He walks from Queens to West Egg for something like six or seven hours, finding evidence that can’t be reproduced, and using a route that can’t be retraced afterward. Unlike Gatsby, forever trying to grasp the thing out he knows well but can’t reach, Wilson homes in on a person he doesn’t know but unerringly reaches.

Society and Class. By the end of this chapter, the rich and the poor are definitely separated - forever, by death . Every main character who isn’t from the upper class - Myrtle, Gatsby, and Wilson - is violently killed. On the other hand, those from the social elite - Jordan, Daisy, and Tom - can continue their lives totally unchanged. Jordan brushes these deaths off completely. Tom gets to hang on to his functionally dysfunctional marriage. And Daisy literally gets away with murder (or at least manslaughter). Only Nick seems to be genuinely affected by what he has witnessed. He survives, but his retreat to his Midwest home marks a kind of death - the death of his romantic idea of achievement and success.

Death and Failure. Rot, decay, and death are everywhere in this chapter:

- Gatsby’s house is in a state of almost supernatural disarray, with “inexplicable amount of dust everywhere” (8.4) after he fires his servants.

- Amidst the parties and gaiety of Daisy’s youth, her “dress tangled among dying orchids on the floor” (8.19).

- Nick’s phrase for the corruption and selfishness of the upper-class people he’s gotten to know is “rotten crowd” (8.45), people who are decomposing into garbage.

- Gatsby floats in a pool, trying to hang on to summer, but actually on the eve of fall, as nature around him turns “frightening,” “unfamiliar,” “grotesque,” and “raw” (8.110).

- This imagery culminates in figurative and literal cremation, as Wilson is described as “ashen” (8.110) and his murder-suicide as a “holocaust” (8.113).

Crucial Character Beats

Nick has a premonition that he wants to warn Gatsby about. Gatsby still holds out hope for Daisy and refuses to get out of town as Nick advises.

Nick and Jordan break up - he is grossed out by her self-involvement and total lack of concern about the fact that Myrtle died the day before.

Wilson goes somewhat crazy after Myrtle’s death, and slowly becomes convinced that the driver of the yellow car that killed her was also her lover, and that he killed her on purpose. He sets out to hunt the owner of the yellow car down.

Wilson shoots Gatsby while Gatsby is waiting for Daisy’s phone call in his pool. Then Wilson shoots himself.

What’s Next?

Think about the novel’s connection to the motif of the seasons by comparing the ways summer, fall, and winter are described and experienced by different characters.

Get a handle on Gatsby’s revelations about his past by seeing all the events put into chronological order .

Move on to the summary of Chapter 9 , or revisit the summary of Chapter 7 .

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Anna scored in the 99th percentile on her SATs in high school, and went on to major in English at Princeton and to get her doctorate in English Literature at Columbia. She is passionate about improving student access to higher education.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis

Nick sees Jay alive for the last time. Tom tells Myrtle’s husband, George, that Gatsby killed his wife and tells him where to find Jay. George makes his way to Gatsby’s mansion, shoots him, and then commits suicide. Nick is the one to find the bodies.

Welcome The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis page prepared by our editorial team! This article contains the chapter’s short synopsis and the key points of The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 described. Here you’ll learn how Gatsby dies and what happens at the end of the novel. The summary is illustrated be the most important quotes from the text. There is also The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 analysis part where we talk about the symbols, literary devices, and foreshadowing used in this chapter.

Here you’ll find a short summary of The Great Gatsby chapter 1 with the key quotes added, a list of active characters, and analysis. We’ll leave no questions unanswered!

🎭 Active Characters

🔥 active themes.

- 🗺️ Navigation

🎓 References

📖 the great gatsby chapter 8 summary.

After the nervous day, Nick can’t fall asleep. In the early morning, he goes to see Gatsby, who stayed outside the Buchanans’ mansion until 4 am. Daisy was not hurt, but she didn’t go out of the house either. Nick recommends Gatsby to forget about her and move out. However, Jay can’t even think about leaving Daisy.

The emotional moment makes Gatsby reveal new details about their love story in Louisville. He admits that it wasn’t only Daisy’s youth and beauty that attracted him. Her wealth and status made Jay fall in love with her . She was the girl Gatsby felt so close to that he lied about his background to keep her. The night they slept together, he felt like they were already married. Daisy promised to wait when Gatsby had to leave for the war.

“I can’t describe to you how surprised I was to find out I loved her, old sport. I even hoped for a while that she’d throw me over, but she didn’t, because she was in love with me too.” ( The Great Gatsby , chapter 8)

When it was over, and he was ready to go home, he could only get to Oxford. It confused Daisy, and as time passed, her feelings began to vanish. Eventually, it led to her marrying Tom.

Nick and Gatsby finish their breakfast, and the gardener says it is time to drain the pool. Gatsby asks him to wait as he never used a chance to swim, and he would like to do so now. Nick realizes he’s late for work and says goodbye to Gatsby. When he’s on his way out, he suddenly feels the urge to turn around and say, “They’re a rotten crowd… You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.” Nick is glad he said it. He has disapproved of Gatsby’s attitude from the very beginning. It was the only time he said something kind to him .

When Nick’s at work, he receives a call from Jordan, but their talk is rather short. Both Nick and Jordan seem irritated. Nick asks her why she was so rough with him last night, and she replies that their relationship didn’t matter in the time of crisis. After a little more of talking, one of them hangs up, and Nick is not even sure who.

Then Nick tells the readers what happened after the accident based on Michaelis’ words. George Wilson and Michaelis are talking about Myrtle the whole night. George says he is sure that it was her lover in the car because she broke out of the room to run out and meet him. Then George recalls that before the accident, he warned her that God knows about her sins . The next morning, Wilson sees Doctor T. J. Eckleburg’s eyes as God’s and decides to seek revenge .

“Standing behind him Michaelis saw with a shock that he was looking at the eyes of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg which had just emerged pale and enormous from the dissolving night. ‘God sees everything,’ repeated Wilson.” ( The Great Gatsby , chapter 8)

He starts looking for the owner of the yellow car and goes to Tom since he was driving it earlier that day. However, George knows that Tom didn’t kill Myrtle because he arrived later in a different car. Eventually, he finds out that Gatsby is the owner of the yellow car and comes to his mansion to shoot him.

When Nick returns to Gatsby’s house, he finds Gatsby shot on the mattress in the pool and Wilson’s body lying dead in the grass nearby.

Nick Carraway, Jay Gatsby, Jordan Baker, George Wilson, Michaelis

|

|

|

| Gender | Social Class | Love & Marriage |

🔬 The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Analysis

When it comes to Gatsby’s love for Daisy, Nick doesn’t leave any unanswered questions in Chapter 8 of The Great Gatsby . Now that he knows the details of the story from Gatsby’s point of view, he is sure that Daisy’s social status and wealth attracted Jay the most . By now, it was hard to tell whether it was real love or just longing for money and power. What Gatsby tells Nick the night of the accident almost makes him a hero who sacrifices himself in the name of love. However, this chapter reveals that there is no difference between yearning for Daisy and wealth.

Nick also adds a few words about the fantastic talent Gatsby has – visionary . He could have achieved genuinely amazing things, which is the reason why he is “great.” Instead, he chooses to chase the girl who has got nothing except for money. Therefore, Daisy ends up being an unworthy object of dreaming, as wealth is now the focus of Gatsby’s life.

In this chapter, more details can be added to the analysis of The Great Gatsby regarding the theme of the American Dream . It begins as a simple dream of a better quality of life . However, it inevitably comes down to money – magical papers that bring happiness and freedom. The same is with Gatsby. His dream development started with his desire to bring back the love from the old days and ended with the crazy greed for wealth. Moreover, it led him to criminal activities since they appeared to be the source of big money. Sadly, this path also leads to Gatsby’s death, making this scene a perfect illustration of the dead American Dream.

The Great Gatsby ‘s Chapter 8 summary isn’t lacking symbols that should be interpreted. One of the most important ones is the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg . Desperate from the loss of his wife, George Wilson needs something to believe in. Enormous eyes staring from the billboard become a divine messager for him. One of the quotes illustrates it best: looking out of the window, he says, “God sees everything.” At that moment, he believes that God wants him to take revenge for Myrtle’s death. Michaelis, trying to reassure George that it is only an advertisement, turns away from the eyes. What is it, if not a fear of God? After Wilson killed Gatsby, he shot himself, which may point to his belief as well. He may have seen it as a holy mission, and as it was completed, there was no point for him to stay in the land of the living.

At the same time, Nick never gives any particular role to the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg. He only highlights a few times that they are watching over the degradation of this empty and ugly world, where people have no moral values and cover their sins with lies. Therefore, the eyes could carry any meaning.

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald – Free Ebook

- The Great Gatsby I Summary

- The Great Gatsby and the American dream

- Best Analysis: Eyes of TJ Eckleburg in The Great Gatsby

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

Study Guide Menu

- Short Summary

- Summary (Chapter 1)

- Summary (Chapter 2)

- Summary (Chapter 3)

- Summary (Chapter 4)

- Summary (Chapter 5)

- Summary (Chapter 6)

- Summary (Chapter 7)

- Summary (Chapter 8)

- Summary (Chapter 9)

- Symbolism & Style

- Quotes Explained

- Essay Topics & Examples

- Questions & Answers

- F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Biography

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, May 21). The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/lit/the-great-gatsby-study-guide/summary-chapter-8/

"The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis." IvyPanda , 21 May 2024, ivypanda.com/lit/the-great-gatsby-study-guide/summary-chapter-8/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis'. 21 May.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis." May 21, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/lit/the-great-gatsby-study-guide/summary-chapter-8/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis." May 21, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/lit/the-great-gatsby-study-guide/summary-chapter-8/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary & Analysis." May 21, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/lit/the-great-gatsby-study-guide/summary-chapter-8/.

The Great Gatsby Chapter 8 Summary

- Gatsby waits all night but nothing happens. (Good call, Nick .)

- The next morning, Nick warns Gatsby that he should go away for a while. Gatsby can't imagine leaving Daisy at this moment, so he stays.

- Nick tells us that this was the first moment he learned of Gatsby's history — the history he revealed to us back in Chapter Six .

- But we get a few more details, courtesy of the Nick grapevine:

- Daisy was the first "nice" girl Gatsby had ever known or met. His initial plan was to get some backseat action, but then he accidentally fell in love . (It happens.)

- There's a great discussion of class and wealth here. Gatsby felt uncomfortable in Daisy's house—she was simply from a finer world than he. When he finally "took" her (in the sexual sense of the word), it was because he wasn't dignified enough to have any other relationship.

- Nick reveals that Gatsby misled her , too, making her believe he was in a position to offer her the safety and financial security of a good marriage, when in fact all he had to give was some lousy undying love.

- In the war, Gatsby did well for himself (medals and such). He tried to get home as soon as the war was over, but through some administrative error or possibly the hand of God, he was sent to Oxford.

- Meanwhile, Daisy got tired of waiting for him and married Tom (right after the drunken sobfest we heard about earlier).

- Gatsby, desperate, tries to figure out what will happen "now." He tries to reassure himself that Daisy does still love him and that the two of them can live happily ever after.

- In an ominous moment, one of Gatsby's servants details that he's going to have the pool drained. Gatsby comments that he hasn't used the pool all summer.

- We suspect that's going to become important in about half a chapter.

- As he leaves, Nick reveals his feelings for Gatsby when he says, "They're a rotten crowd […]. You're worth the whole damn bunch put together." And YET, Nick reminds us that he "disapproved" of Gatsby "from beginning to end."

- Once he's at work, Jordan calls him on the phone. They are both sort of cold to each other. Their status just changed from "in a relationship" to "it's complicated."

- No, wait, they are both now officially "single." Nick is just sick of the entire crowd and doesn't want to have anything more to do with them.

- Back to the Myrtle death story. We find all of this out from Nick who found out from Michaelis (or possibly some other intermediary):

- George Wilson, in the midst of his grieving, revealed that he had recently started to suspect his wife of having an affair. He had found an expensive dog collar in her room (from Tom) and huge bruises on her face one day (also from Tom).

- George came to the sudden conclusion that whoever was driving the car was the same man having an affair with his wife.

- Before she died, George had taken his wife over to the window and told her that she couldn't fool God—that God was always watching. Conveniently, the large eyes of T.J. Eckleburg emerged visible from the fog.

- And that's the end of that menacing little story.

- Back in present time, George goes on a crazy vengeance mission to find out who owns that yellow car. He, of course, ends up at Gatsby's house.

- Gatsby, meanwhile, has decided that it's time to use that pool of his.

- Shots are fired.

- Nick ends up at Gatsby's house, and together with the staff discovers that George Wilson has shot Gatsby and then himself. Both are dead.

Tired of ads?

Cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

- The Great Gatsby

F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Literature Notes

- The Great Gatsby at a Glance

- Book Summary

- About The Great Gatsby

- Character List

- Summary and Analysis

- Character Analysis

- Nick Carraway

- Daisy Buchanan

- Character Map

- F. Scott Fitzgerald Biography

- Critical Essays

- Social Stratification: The Great Gatsby as Social Commentary

- In Praise of Comfort: Displaced Spirituality in The Great Gatsby

- Famous Quotes from The Great Gatsby

- Film Versions of The Great Gatsby

- Full Glossary for The Great Gatsby

- Essay Questions

- Practice Projects

- Cite this Literature Note

Summary and Analysis Chapter 8

Nick wakes as Chapter 8 opens, hearing Gatsby return home from his all-night vigil at the Buchanans. He goes to Gatsby's, feeling he should tell him something (even he doesn't know what, exactly). Gatsby reveals that nothing happened while he kept his watch. Nick suggests Gatsby leave town for a while, certain Gatsby's car would be identified as the "death car." Nick's comments make Gatsby reveal the story of his past, "because 'Jay Gatsby' had broken up like glass against Tom's hard malice." Daisy, Gatsby reveals, was his social superior, yet they fell deeply in love. The reader also learns that, when courting, Daisy and Gatsby had been intimate with each other and it was this act of intimacy that bonded him to her inexorably, feeling "married to her." Gatsby left Daisy, heading off to war. He excelled in battle and when the war was over, he tried to get home, but ended up at Oxford instead. Daisy didn't understand why he didn't return directly and, over time, her interest began to wane until she eventually broke off their relationship.

Moving back to the present, Gatsby and Nick continue their discussion of Daisy and how Gatsby had gone to Louisville to find her upon his return to the United States. She was on her honeymoon and Gatsby was left with a "melancholy beauty," as well as the idea that if he had only searched harder he would have found her. The men are finishing breakfast as Gatsby's gardener arrives. He says he plans on draining the pool because the season is over, but Gatsby asks him to wait because he hasn't used the pool at all. Nick, purposely moving slowly, heads to his train. He doesn't want to leave Gatsby, impulsively declaring "They're a rotten crowd . . . You're worth the whole damn bunch put together."

For Nick, the day drags on; he feels uneasy, preoccupied with the past day's adventures. Jordan phones, but Nick cuts her off. He phones Gatsby and, unable to reach him, decides to head home early. The narrative again shifts time and focus, as Fitzgerald goes back in time, to the evening prior, in the valley of ashes. George Wilson, despondent at Myrtle's death, appears irrational when Michaelis attempts to engage him in conversation. By morning, Michaelis is exhausted and returns home to sleep. When he returns four hours later, Wilson is gone and has traveled to Port Roosevelt, Gads Hill, West Egg, and ultimately, Gatsby's house. There he finds Gatsby floating on an air mattress in the pool. Wilson, sure that Gatsby is responsible for his wife's death, shoots and kills Gatsby. Nick finds Gatsby's body floating in the pool and, while starting to the house with the body, the gardener discovers Wilson's lifeless body off in the grass.

Chapter 8 displays the tragic side of the American dream as Gatsby is gunned down by George Wilson. The death is brutal, if not unexpected, and brings to an end the life of the paragon of idealism. The myth of Gatsby will continue, thanks to Nick who relays the story, but Gatsby's death loudly marks the end of an era. In many senses, Gatsby is the dreamer inside all of everyone. Although the reader cheers him as he pursues his dreams, one also knows that pure idealism cannot survive in the harsh modern world. This chapter, as well as the one following, also provides astute commentary on the world that, in effect, allowed the death of Gatsby.

As the chapter opens, Nick is struggling with the situation at hand. He grapples with what's right and what's wrong, which humanizes him and lifts him above the rigid callousness of the story's other characters. Unable to sleep (a premonition of bad things to come) he heads to Gatsby's who is returning from his all-night vigil outside Daisy's house. Nick, always a bit more levelheaded and sensitive to the world around him than the other characters, senses something large is about to happen. Although he can't put his finger on it, his moral sense pulls him to Gatsby's. Upon his arrival, Gatsby seems genuinely surprised his services were not necessary outside Daisy's house, showing again just how little he really knows her.

As the men search Gatsby's house for cigarettes, the reader learns more about both Nick and Gatsby. Nick moves further and further from the background to emerge as a forceful presence in the novel, showing genuine care and concern for Gatsby, urging him to leave the city for his own protection. Throughout the chapter, Nick is continually pulled toward his friend, anxious for reasons he can't exactly articulate. Whereas Nick shows his true mettle in a flattering light in this chapter, Gatsby doesn't fare as well. He becomes weaker and more helpless, despondent in the loss of his dream. It is as if he refuses to admit that the story hasn't turned out as he intended. He refuses to acknowledge that the illusion that buoyed him for so many years has vanished, leaving him hollow and essentially empty.

As the men search Gatsby's house for the elusive cigarettes, Gatsby fills Nick in on the real story. For the first time in the novel, Gatsby sets aside his romantic view of life and confronts the past he has been trying to run from, as well as the present he has been trying to avoid. Daisy, it turns out, captured Gatsby's love largely because "she was the first 'nice' girl he had ever known." She moved in a world Gatsby aspired to and unlike other people of that particular social set, she acknowledged Gatsby's presence in that world. Although he doesn't admit it, his love affair with Daisy started early, when he erroneously defined her not merely by who she was, but by what she had and what she represented. All through the early days of their courtship, however, Gatsby tormented himself with his unworthiness, knowing "he was in Daisy's house by a colossal accident," although he led Daisy to believe he was a man of means. Although his original intention was to use Daisy, he found out that he was incapable of doing so. When their relation became intimate, he still felt unworthy, and with the intimacy, Gatsby found himself wedded, not to Daisy directly, but to the quest to prove himself worthy of her. (How sad that Gatsby's judgment is so clouded with societal expectation that he can't see that a young, idealistic man who has passion, drive, and persistence is worth more than ten Daisys put together.)

In loving Daisy, it turns out, Gatsby was trapped. On one hand, he loved her and she loved him, or more precisely, he loved what he envisioned her to be and she loved the persona he presented to her — and therein lies the rub. Both Daisy and Gatsby were in love with projected images and while Daisy didn't realize this at first, Gatsby did, and it forced him more directly into his dream world. After the war (in which Gatsby really did excel), Gatsby could have returned home to Daisy. The only difficulty with that, however, would have been that in being with Daisy, he would run the risk of being exposed as an imposter. So, rather than risk having his dream disintegrate in front of him, he perpetuated his illusion by studying at Oxford before heading back to the States. Daisy's letters begged him to return, not understanding why he wasn't rushing back to be with her. She was missing the post-war euphoria sweeping the nation and she wanted her dashing officer by her side. Eventually Daisy moved again into society, feeling the need to have some stability and purpose in her life. However, Daisy's lack of principle shows when she is willing to use love, money, or practicality (whichever was handier) to determine the direction of her life. She wanted to be married. When Tom arrived, he seemed the obvious choice, and so Daisy sent Gatsby a letter at Oxford.

The letter, it turns out, brought Gatsby back stateside. It is as if now that Daisy was married he could return and not have to fear being found out. He could carry his love for Daisy around with him, knowing full well that she was unobtainable. Although Gatsby isn't likely to admit it, in a way, Daisy marrying Tom was the perfect solution to his situation because now that she was married to another, she need never know how poor he really was. After returning to the U.S., Gatsby travels to Louisville with his last bit of money, and there the quest begins in earnest. From this moment, he spends his days trying to recapture the beauty that he basked in while with young Daisy Fay.

Upon hearing Gatsby's true story, Nick cannot help but be moved and spends the rest of the day worrying about his friend. While in the city, Nick tries desperately to keep focused on his work, but can't seem to do so. What he has realized (through Gatsby's story and the events of the previous night), and part of what is troubling him, is that he has come to know the shallowness of "polite society." Gatsby, a dreamer from nowhere, has passion and genuinely cares about something, even if it is a dream, and that is more than can be said for people like the Buchanans and Jordan Baker. In fact, when Jordan phones Nick at work he is unwilling to speak to her, finding himself more and more irritated by her shallow and self-serving ways. In rejecting her (the first man ever to do so) Nick has grown, not only seeing what dark stuff that socialites are really made of, but possessing the courage to stand against it.

Midway through the chapter, Fitzgerald shifts focus to the valley of ashes and has Nick recount what had gone on there in the hours prior. George Wilson has become overwhelmed with grief at the loss of his wife. Directly contrasting Tom Buchanan (who is unable to experience a heartfelt emotion), George is devastated and overwhelmed by emotion. His neighbor, Michaelis, tries to console him, but nothing seems to help. George lives in an effectual wasteland, void of spirituality, void of life, and when in his grief he tells Michaelis of his last day with Myrtle, he turns to the giant billboard above him. In what is perhaps his most lucid statement in the whole book, Wilson explains the purpose of Doctor T. J. Eckleburg's enormous eyes. They are the eyes of God, and "God sees everything."

Wilson's grief knows no bounds and while Michaelis sleeps, he heads in to town, eventually tracking Gatsby down and killing him while he floats on an air mattress in his swimming pool. Fitzgerald has made clear earlier in the chapter that autumn is at hand, and it naturally brings with it the ending of life — natural and human, both. Wilson, still overcome by grief and the bad judgment it invokes, finds his way to Gatsby's house (tipped off by Tom, as Nick discovers in Chapter 9) and kills Gatsby, mistakenly thinking that he is responsible for Myrtle's death.

Gatsby's death, alone in his pool, brings forth a couple of distinct images. On the one hand, his death is a rebirth of sorts. Gatsby has done nothing more than follow a dream, and despite his money and his questionable business dealings, he is nothing at all like the East Egg socialites he runs with. One admires him, if for no other reason than his ability to sustain a dream in a world that is historically inhospitable to dreamers. His death has, in a sense, removed him from his mortal existence and allowed him rebirth into a different, hopefully better, life. As Nick says, Gatsby "must have felt that he had lost the old warm world" when his dream died, and found no reason to go on. In that sense, Wilson's murdering him is a welcome end. On another level, Gatsby's death at the hands of George Wilson makes his quest complete. His dream is completely dead, but he can make one more chivalric gesture: He can be killed in Daisy's stead. By lying in the pool, Gatsby is doing nothing to protect himself, as if he is saying that he won't refuse whatever is ahead of him. In some sense, Gatsby helps Wilson by refusing to be proactive in his own defense. Until the very end, Gatsby remains the dreamer, that most rare of jewels in the modern world.

pneumatic filled with compressed air.

Previous Chapter 7

Next Chapter 9

has been added to your

Reading List!

Removing #book# from your Reading List will also remove any bookmarked pages associated with this title.

Are you sure you want to remove #bookConfirmation# and any corresponding bookmarks?

The Great Gatsby

53 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Chapter 8 Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapter 8 summary.

After the night of the car accident, Nick cannot sleep. Upon hearing a taxi arrive in Gatsby’s driveway, Nick walks over to meet his neighbor. He advises Gatsby to leave town because the police will eventually identify his car.

Gatsby tells the story of his youthful love affair with Daisy and the power it held over him in the years that followed. When the story ends, one of Gatsby’s servants asks him if it’s okay to drain the pool. Gatsby tells him to wait and repeats to Nick something he has said twice already: that he has not used the pool all summer.

As Gatsby and Nick say goodbye, Nick tells him that he’s “worth more” than Tom, Daisy, or anyone else he’s associated with on West Egg. Despite his thorough disgust for Gatsby, Nick is happy to have said this.

Related Titles

By F. Scott Fitzgerald

Babylon Revisited

Bernice Bobs Her Hair

Crazy Sunday

Tender Is the Night

The Beautiful and Damned

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button

The Diamond as Big as the Ritz

The Last Tycoon

This Side of Paradise

Winter Dreams

Featured Collections

American Literature

View Collection

Audio Study Guides

Banned Books Week

Books Made into Movies

BookTok Books

The Lost Generation

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald – Chapter 8 with Summary

Full chapter of f. scott fitzgerald's iconic novel set in 1920s america..

Lucy Davidson

02 jan 2022, @lucejuiceluce.

Chapter 8 Summary

Nick awakens and hears Gatsby return from the Buchanans. Nick visits Gatsby who tells him that nothing happened overnight; nonetheless, Nick advises that Gatsby leave town before his car is identified. Gatsby reveals the truth about his past with Daisy. He tells Nick that Daisy was his social superior; nonetheless, they fell deeply in love and slept together, which made Gatsby feel married to her. He went away to war, and when he went to Oxford instead of returning home immediately, Daisy’s interest waned and she broke off the relationship.

Gatsby tells Nick that he went to Louisville to find Daisy when he returned to the US. However, she was on her honeymoon; this devastated Gatsby, and left him forever under the impression that he would have found her if he looked harder. The gardener arrives, who tells Gatsby that he will drain the pool as the season is over. Gatsby tells him to wait because he hasn’t used the pool. Nick leaves to catch a train but doesn’t want to leave Gatsby. He tells Gatsby that he is worth more than the whole ‘rotten crowd’ put together.

Nick’s day drags on. He feels uneasy. Jordan phones, but Nick cuts her off, then Nick tries and fails to reach Gatsby over the phone. The narrative shifts to the evening before with the grieving and angry George Wilson travelling to Gatsby’s home. He finds Gatsby floating on an air mattress in the pool, and shoots him dead. Nick discovers Gatsby’s body. The gardener discovers Wilson has shot himself nearby on the grass.

The Great Gatsby, Chapter 8 Full Text

I couldn’t sleep all night; a fog-horn was groaning incessantly on the Sound, and I tossed half-sick between grotesque reality and savage frightening dreams. Toward dawn I heard a taxi go up Gatsby’s drive and immediately I jumped out of bed and began to dress—I felt that I had something to tell him, something to warn him about and morning would be too late.

Crossing his lawn I saw that his front door was still open and he was leaning against a table in the hall, heavy with dejection or sleep.

“Nothing happened,” he said wanly. “I waited, and about four o’clock she came to the window and stood there for a minute and then turned out the light.”

His house had never seemed so enormous to me as it did that night when we hunted through the great rooms for cigarettes. We pushed aside curtains that were like pavilions and felt over innumerable feet of dark wall for electric light switches—once I tumbled with a sort of splash upon the keys of a ghostly piano. There was an inexplicable amount of dust everywhere and the rooms were musty as though they hadn’t been aired for many days. I found the humidor on an unfamiliar table with two stale dry cigarettes inside. Throwing open the French windows of the drawing-room we sat smoking out into the darkness.

“You ought to go away,” I said. “It’s pretty certain they’ll trace your car.”

“Go away now, old sport?”

“Go to Atlantic City for a week, or up to Montreal.”

He wouldn’t consider it. He couldn’t possibly leave Daisy until he knew what she was going to do. He was clutching at some last hope and I couldn’t bear to shake him free.

It was this night that he told me the strange story of his youth with Dan Cody—told it to me because “Jay Gatsby” had broken up like glass against Tom’s hard malice and the long secret extravaganza was played out. I think that he would have acknowledged anything, now, without reserve, but he wanted to talk about Daisy.

She was the first “nice” girl he had ever known. In various unrevealed capacities he had come in contact with such people but always with indiscernible barbed wire between. He found her excitingly desirable. He went to her house, at first with other officers from Camp Taylor, then alone. It amazed him—he had never been in such a beautiful house before. But what gave it an air of breathless intensity was that Daisy lived there—it was as casual a thing to her as his tent out at camp was to him. There was a ripe mystery about it, a hint of bedrooms upstairs more beautiful and cool than other bedrooms, of gay and radiant activities taking place through its corridors and of romances that were not musty and laid away already in lavender but fresh and breathing and redolent of this year’s shining motor cars and of dances whose flowers were scarcely withered. It excited him too that many men had already loved Daisy—it increased her value in his eyes. He felt their presence all about the house, pervading the air with the shades and echoes of still vibrant emotions.

But he knew that he was in Daisy’s house by a colossal accident. However glorious might be his future as Jay Gatsby, he was at present a penniless young man without a past, and at any moment the invisible cloak of his uniform might slip from his shoulders. So he made the most of his time. He took what he could get, ravenously and unscrupulously—eventually he took Daisy one still October night, took her because he had no real right to touch her hand.

He might have despised himself, for he had certainly taken her under false pretenses. I don’t mean that he had traded on his phantom millions, but he had deliberately given Daisy a sense of security; he let her believe that he was a person from much the same stratum as herself—that he was fully able to take care of her. As a matter of fact he had no such facilities—he had no comfortable family standing behind him and he was liable at the whim of an impersonal government to be blown anywhere about the world.

But he didn’t despise himself and it didn’t turn out as he had imagined. He had intended, probably, to take what he could and go—but now he found that he had committed himself to the following of a grail. He knew that Daisy was extraordinary but he didn’t realize just how extraordinary a “nice” girl could be. She vanished into her rich house, into her rich, full life, leaving Gatsby—nothing. He felt married to her, that was all.

When they met again two days later it was Gatsby who was breathless, who was somehow betrayed. Her porch was bright with the bought luxury of star-shine; the wicker of the settee squeaked fashionably as she turned toward him and he kissed her curious and lovely mouth. She had caught a cold and it made her voice huskier and more charming than ever and Gatsby was overwhelmingly aware of the youth and mystery that wealth imprisons and preserves, of the freshness of many clothes and of Daisy, gleaming like silver, safe and proud above the hot struggles of the poor.

“I can’t describe to you how surprised I was to find out I loved her, old sport. I even hoped for a while that she’d throw me over, but she didn’t, because she was in love with me too. She thought I knew a lot because I knew different things from her…Well, there I was, way off my ambitions, getting deeper in love every minute, and all of a sudden I didn’t care. What was the use of doing great things if I could have a better time telling her what I was going to do?”

On the last afternoon before he went abroad he sat with Daisy in his arms for a long, silent time. It was a cold fall day with fire in the room and her cheeks flushed. Now and then she moved and he changed his arm a little and once he kissed her dark shining hair. The afternoon had made them tranquil for a while as if to give them a deep memory for the long parting the next day promised. They had never been closer in their month of love nor communicated more profoundly one with another than when she brushed silent lips against his coat’s shoulder or when he touched the end of her fingers, gently, as though she were asleep.

He did extraordinarily well in the war. He was a captain before he went to the front and following the Argonne battles he got his majority and the command of the divisional machine guns. After the Armistice he tried frantically to get home but some complication or misunderstanding sent him to Oxford instead. He was worried now—there was a quality of nervous despair in Daisy’s letters. She didn’t see why he couldn’t come. She was feeling the pressure of the world outside and she wanted to see him and feel his presence beside her and be reassured that she was doing the right thing after all.

For Daisy was young and her artificial world was redolent of orchids and pleasant, cheerful snobbery and orchestras which set the rhythm of the year, summing up the sadness and suggestiveness of life in new tunes. All night the saxophones wailed the hopeless comment of the “Beale Street Blues” while a hundred pairs of golden and silver slippers shuffled the shining dust. At the grey tea hour there were always rooms that throbbed incessantly with this low sweet fever, while fresh faces drifted here and there like rose petals blown by the sad horns around the floor.

Through this twilight universe Daisy began to move again with the season; suddenly she was again keeping half a dozen dates a day with half a dozen men and drowsing asleep at dawn with the beads and chiffon of an evening dress tangled among dying orchids on the floor beside her bed. And all the time something within her was crying for a decision. She wanted her life shaped now, immediately—and the decision must be made by some force—of love, of money, of unquestionable practicality—that was close at hand.

That force took shape in the middle of spring with the arrival of Tom Buchanan. There was a wholesome bulkiness about his person and his position and Daisy was flattered. Doubtless there was a certain struggle and a certain relief. The letter reached Gatsby while he was still at Oxford.

It was dawn now on Long Island and we went about opening the rest of the windows downstairs, filling the house with grey turning, gold turning light. The shadow of a tree fell abruptly across the dew and ghostly birds began to sing among the blue leaves. There was a slow pleasant movement in the air, scarcely a wind, promising a cool lovely day.

“I don’t think she ever loved him.” Gatsby turned around from a window and looked at me challengingly. “You must remember, old sport, she was very excited this afternoon. He told her those things in a way that frightened her—that made it look as if I was some kind of cheap sharper. And the result was she hardly knew what she was saying.”

He sat down gloomily.

“Of course she might have loved him, just for a minute, when they were first married—and loved me more even then, do you see?”

Suddenly he came out with a curious remark:

“In any case,” he said, “it was just personal.”

What could you make of that, except to suspect some intensity in his conception of the affair that couldn’t be measured?

He came back from France when Tom and Daisy were still on their wedding trip, and made a miserable but irresistible journey to Louisville on the last of his army pay. He stayed there a week, walking the streets where their footsteps had clicked together through the November night and revisiting the out-of-the-way places to which they had driven in her white car. Just as Daisy’s house had always seemed to him more mysterious and gay than other houses so his idea of the city itself, even though she was gone from it, was pervaded with a melancholy beauty.

He left feeling that if he had searched harder he might have found her—that he was leaving her behind. The day-coach—he was penniless now—was hot. He went out to the open vestibule and sat down on a folding-chair, and the station slid away and the backs of unfamiliar buildings moved by. Then out into the spring fields, where a yellow trolley raced them for a minute with people in it who might once have seen the pale magic of her face along the casual street.

The track curved and now it was going away from the sun which, as it sank lower, seemed to spread itself in benediction over the vanishing city where she had drawn her breath. He stretched out his hand desperately as if to snatch only a wisp of air, to save a fragment of the spot that she had made lovely for him. But it was all going by too fast now for his blurred eyes and he knew that he had lost that part of it, the freshest and the best, forever.

It was nine o’clock when we finished breakfast and went out on the porch. The night had made a sharp difference in the weather and there was an autumn flavor in the air. The gardener, the last one of Gatsby’s former servants, came to the foot of the steps.

“I’m going to drain the pool today, Mr. Gatsby. Leaves’ll start falling pretty soon and then there’s always trouble with the pipes.”

“Don’t do it today,” Gatsby answered. He turned to me apologetically. “You know, old sport, I’ve never used that pool all summer?”

I looked at my watch and stood up.

“Twelve minutes to my train.”

I didn’t want to go to the city. I wasn’t worth a decent stroke of work but it was more than that—I didn’t want to leave Gatsby. I missed that train, and then another, before I could get myself away.

“I’ll call you up,” I said finally.

“Do, old sport.”

“I’ll call you about noon.”

We walked slowly down the steps.

“I suppose Daisy’ll call too.” He looked at me anxiously as if he hoped I’d corroborate this.

“I suppose so.”

“Well—goodbye.”

We shook hands and I started away. Just before I reached the hedge I remembered something and turned around.

“They’re a rotten crowd,” I shouted across the lawn. “You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

I’ve always been glad I said that. It was the only compliment I ever gave him, because I disapproved of him from beginning to end. First he nodded politely, and then his face broke into that radiant and understanding smile, as if we’d been in ecstatic cahoots on that fact all the time. His gorgeous pink rag of a suit made a bright spot of color against the white steps and I thought of the night when I first came to his ancestral home three months before. The lawn and drive had been crowded with the faces of those who guessed at his corruption—and he had stood on those steps, concealing his incorruptible dream, as he waved them goodbye.

I thanked him for his hospitality. We were always thanking him for that—I and the others.

“Goodbye,” I called. “I enjoyed breakfast, Gatsby.”

Up in the city I tried for a while to list the quotations on an interminable amount of stock, then I fell asleep in my swivel-chair. Just before noon the phone woke me and I started up with sweat breaking out on my forehead. It was Jordan Baker; she often called me up at this hour because the uncertainty of her own movements between hotels and clubs and private houses made her hard to find in any other way. Usually her voice came over the wire as something fresh and cool as if a divot from a green golf links had come sailing in at the office window but this morning it seemed harsh and dry.

“I’ve left Daisy’s house,” she said. “I’m at Hempstead and I’m going down to Southampton this afternoon.”

Probably it had been tactful to leave Daisy’s house, but the act annoyed me and her next remark made me rigid.

“You weren’t so nice to me last night.”

“How could it have mattered then?”

Silence for a moment. Then—

“However—I want to see you.”

“I want to see you too.”

“Suppose I don’t go to Southampton, and come into town this afternoon?”

“No—I don’t think this afternoon.”

“Very well.”

“It’s impossible this afternoon. Various—”

We talked like that for a while and then abruptly we weren’t talking any longer. I don’t know which of us hung up with a sharp click but I know I didn’t care. I couldn’t have talked to her across a tea-table that day if I never talked to her again in this world.

I called Gatsby’s house a few minutes later, but the line was busy. I tried four times; finally an exasperated central told me the wire was being kept open for long distance from Detroit. Taking out my time-table I drew a small circle around the three-fifty train. Then I leaned back in my chair and tried to think. It was just noon.

When I passed the ashheaps on the train that morning I had crossed deliberately to the other side of the car. I suppose there’d be a curious crowd around there all day with little boys searching for dark spots in the dust and some garrulous man telling over and over what had happened until it became less and less real even to him and he could tell it no longer and Myrtle Wilson’s tragic achievement was forgotten. Now I want to go back a little and tell what happened at the garage after we left there the night before.

They had difficulty in locating the sister, Catherine. She must have broken her rule against drinking that night for when she arrived she was stupid with liquor and unable to understand that the ambulance had already gone to Flushing. When they convinced her of this she immediately fainted as if that was the intolerable part of the affair. Someone kind or curious took her in his car and drove her in the wake of her sister’s body.

Until long after midnight a changing crowd lapped up against the front of the garage while George Wilson rocked himself back and forth on the couch inside. For a while the door of the office was open and everyone who came into the garage glanced irresistibly through it. Finally someone said it was a shame and closed the door. Michaelis and several other men were with him—first four or five men, later two or three men. Still later Michaelis had to ask the last stranger to wait there fifteen minutes longer while he went back to his own place and made a pot of coffee. After that he stayed there alone with Wilson until dawn.

About three o’clock the quality of Wilson’s incoherent muttering changed—he grew quieter and began to talk about the yellow car. He announced that he had a way of finding out whom the yellow car belonged to, and then he blurted out that a couple of months ago his wife had come from the city with her face bruised and her nose swollen.

But when he heard himself say this, he flinched and began to cry “Oh, my God!” again in his groaning voice. Michaelis made a clumsy attempt to distract him.

“How long have you been married, George? Come on there, try and sit still a minute and answer my question. How long have you been married?”

“Twelve years.”

“Ever had any children? Come on, George, sit still—I asked you a question. Did you ever have any children?”