- Medina M, Castillo-Pino E. An introduction to the epidemiology and burden of urinary tract infections. Ther Adv Urol . 2019;11:1756287219832172.

- Schaeffer AJ, Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infections in older men. N Engl J Med . 2016;374:562-571.

- Öztürk R, Murt A. Epidemiology of urological infections: a global burden. World J Urol . 2020;38:2669-2679.

- Sabih A, Leslie SW. Complicated urinary tract infections. In: Abai A, Abu-Ghosh A, Archarya AB, et al. StatPearls . StatsPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated February 2021. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436013/

- Colgan R, Williams M. Diagnosis and treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis. Am Fam Physician . 2011;84:771-776.

- Tamma PD, Aitken L, Bonomo RA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of antimicrobial resistant gram-negative infections. Published September 8, 2020. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.idsociety.org/globalassets/idsa/practice-guidelines/amr-guidance/idsa-amr-guidance.pdf

- Kudinha T. The pathogenesis of Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. In: Samie A, ed. Escherichia coli - Recent Advances on Physiology, Pathogenesis and Biotechnological Applications. IntechOpen Limited; 2017. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.intechopen.com/books/-i-escherichia-coli-i-recent-advances-on-physiology-pathogenesis-and-biotechnological-applications/the-pathogenesis-of-i-escherichia-coli-i-urinary-tract-infection

- Moore EE, Hawes SE, Scholes D, et al. Sexual intercourse and risk of symptomatic urinary tract infection in post-menopausal women. J Gen Intern Med . 2008;23:595-599.

- Belyayeva M, Jeong JM. Acute pyelonephritis. In: Abai A, Abu-Ghosh A, Acharya AB, et al. StatPearls . StatsPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated July 2020. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519537/

- Mertz D, Duława J, Drabczyk R. Uncomplicated acute pyelonephritis. In: McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine . Medycyna Praktyczna; 2019. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://empendium.com/mcmtextbook/chapter/B31.II.14.8.3

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) Seer Training Modules. Normal Blood Values. Accessed July 16, 2021. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/abstracting/procedures/clinical/hematologic/blood.html

- Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis . 2011;52:e103-e120.

- Arena F, Giani T, Pollini S, et al. Molecular antibiogram in diagnostic clinical microbiology: advantages and challenges. Future Microbiol . 2017;12:361-364.

- Wagenlehner FM, Cek M, Naber KG, et al. Epidemiology, treatment and prevention of healthcare-associated urinary tract infections. World J Urol . 2012;30:59-67.

- Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman H, et al. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all cause mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ . 2019;364:1525.

- Lentz GM. Urinary tract infections in obstetrics and gynecology. Global Library of Women's Medicine. Updated May 2009. Accessed July 1, 2021. https://www.glowm.com/section-view/heading/Urinary%20Tract%20Infections%20in%20Obstetrics%20and%20Gynecology/item/118#.YN8TjehKhBA

- Ehlers S, Merrill SA. Staphylococcus saprophyticus . In: Abai A, Abu-Ghosh A, Acharya AB, et al. StatPearls . StatsPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated June 2020. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482367/

- Katouli M. Population structure of gut Escherichia coli and its role in development of extra-intestinal infections. Iran J Microbiol . 2010;2:59-72.

- Mobley HL, Donnenberg MS, Hagan EC. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli . EcoSal Plus . 2009;3:10.1128/ecosalplus.8.6.1.3.

- Tamma PD, Aitken SL, Bonomo RA, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidance on the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing enterobacterales (ESBL-E), carbapenem-resistant enterobacterales (CRE), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa with difficult-to-treat resistance (DTR- aeruginosa ). Clin Infect Dis . 2021;72:e169-e183.

- Doi Y, Park YS, Rivera JI, et al. Community-associated extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis . 2013;56:641-648.

- Jernigan JA, Hatfield KM, Wolford H, et al. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in US hospitalized patients, 2012-2017. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:1309-1319.

- van Duin D, Paterson DL. Multidrug-resistant bacteria in the community: trends and lessons learned. Infect Dis Clin North Am . 2016;30:377-390.

- Rawat D, Nair D. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in gram negative bacteria. J Glob Infect Dis . 2010;2:263-274.

- Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, et al. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis . 2016;63:310-318.

- Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez B, Rodríguez-Baño J. Current options for the treatment of infections due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in different groups of patients. Clin Microbiol Infect . 2019;25:932-942.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States - 2019. Updated December 2019. Accessed July 2, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf

- Karaiskos I, Giamarellou H. Carbapenem-sparing strategies for ESBL producers: when and how. Antibiotics (Basel) . 2020;9:61.

- Larramendy S, Deglaire V, Dusollier P, et al. Risk factors of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases-producing Escherichia coli community acquired urinary tract infections: a systematic review. Infect Drug Resist . 2020;13:3945-3955.

- Goyal D, Dean N, Neill S, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections-a retrospective study of symptomatic urinary tract infections. Open Forum Infect Dis . 2019;6:ofy357.

- Koksal E, Tulek N, Sonmezer MC, et al. Investigation of risk factors for community-acquired urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase Escherichia coli and Klebsiella Investig Clin Urol . 2019;60:46-53.

- Augustine MR, Testerman TL, Justo JA, et al. Clinical risk score for prediction of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in bloodstream isolates. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2017;38:266-272.

- Goodman KE, Lessler J, Cosgrove SE, et al. A clinical decision tree to predict whether a bacteremic patient is infected with an extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing organism. Clin Infect Dis . 2016;63:896-903.

- Tumbarello M, Trecarichi EM, Bassetti M, et al. Identifying patients harboring extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae on hospital admission: derivation and validation of a scoring system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother . 2011;55:3485-3490.

- Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis . 2019;68:e83-e110.

- Givler DN, Givler A. Asymptomatic bacteriuria. In: Abai A, Abu-Ghosh A, Acharya AB, et al. StatPearls . StatsPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated January 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441848/

- Hooton TM, Gupta K. Acute Complicated Urinary Tract Infection (Including Pyelonephritis) in Adults. UpToDate. Updated March 19, 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-complicated-urinary-tract-infection-including-pyelonephritis-in-adults

- Cai T, Mazzoli S, Mondaini N, et al. The role of asymptomatic bacteriuria in young women with recurrent urinary tract infections: to treat or not to treat? Clin Infect Dis . 2012;55:771-777.

- Habak PJ, Griggs, Jr RP. Urinary tract infection in pregnancy. In: Abai A, Abu-Ghosh A, Acharya AB, et al. StatPearls . StatsPearls Publishing; 2020. Updated November 2020. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537047/

- Kazemier BM, Koningstein FN, Schneeberger C, et al. Maternal and neonatal consequences of treated and untreated asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy: a prospective cohort study with an embedded randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis . 2015;15:1324-1333.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Published 2019. Accessed July 4, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/pseudomonas-aeruginosa-508.pdf

- Döring G, Ulrich M, Müller W, et al. Generation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa aerosols during handwashing from contaminated sink drains, transmission to hands of hospital personnel, and its prevention by use of a new heating device. Zentralbl Hyg Umweltmed . 1991;191:494-505.

- Aloush V, Navon-Venezia S, Seigman-Igra Y, et al. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa : risk factors and clinical impact. Antimicrob Agents Chemother . 2006;50:43-48.

- Pang Z, Raudonis R, Glick BR, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa : mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv . 2019;37:177-192.

- Cole SJ, Records AR, Orr MW, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infection by Pseudomonas aeruginosa is mediated by exopolysaccharide-independent biofilms. Infect Immun . 2014;82:2048-2058.

- Raman G, Avendano EE, Chan J, et al. Risk factors for hospitalized patients with resistant or multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control . 2018;7:79.

- Gomila A, Carratalà J, Eliakim-Raz N, et al. Risk factors and prognosis of complicated urinary tract infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitalized patients: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Infect Drug Resist . 2018;11:2571-2581.

- Lamas Ferreiro JL, Álvarez Otero J, González González L, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients: mortality and prognostic factors. PLoS One . 2017;12:e0178178.

- Zerbraxa® (ceftolozane and tazobactam) [prescribing information]. Merck & Co, Inc; Approved 2014. Revised September 2020.

- Haidar G, Philips NJ, Shields RK, et al. Ceftolozane-tazobactam for the treatment of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: clinical effectiveness and evolution of resistance. Clin Infect Dis . 2017;65:110-120.

- Lob SH, Hoban DJ, Young K, et al. Activity of ceftolozane-tazobactam and comparators against Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients in different risk strata - SMART United States 2016-2017. J Glob Antimicrob Resist . 2020;20:209-213.

- Shirley M. Ceftazidime-avibactam: a review in the treatment of serious gram-negative bacterial infections. Drugs . 2018;78:675-692.

- Avycaz® (ceftazidime and avibactam) [prescribing information]. Allergan USA, Inc; Approved 2015. Revised December 2020.

- Stone GG, Newell P, Gasink LB, et al. Clinical activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against MDR Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: pooled data from the ceftazidime/avibactam phase III clinical trial programme. J Antimicrob Chemother . 2018;73:2519-2523.

- Recarbrio™ (imipenem, cilastatin, and relebactam) [prescribing information] Merck & Co, Inc; Approved 2019. Revised June 2020.

- Heo YA. Imipenem/cilastatin/relebactam: a review in gram-negative bacterial infections. Drugs . 2021;81:377-388.

- US Food & Drug Administration (FDA). FDA approves new antibacterial drug to treat complicated urinary tract infections as part of ongoing efforts to address antimicrobial resistance. News release. November 14, 2019. Accessed July 5, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-antibacterial-drug-treat-complicated-urinary-tract-infections-part-ongoing-efforts

- Fetroja® (cefiderocol) [prescribing information]. Shionogi Inc; Approved 2019. Revised September 2020.

- El-Lababidi RM, Rizk JG. Cefiderocol: a siderophore cephalosporin. Ann Pharmacother . 2020;54:1215-1231.

- Stevens RW, Clancy M. Compassionate use of cefiderocol in the treatment of an intraabdominal infection due to multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa : a case report. Pharmacotherapy . 2019;39:1113-1118.

- Krause KM, Serio AW, Kane TR, et al. Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med . 2016;6:a027029.

- Gonzalez LS 3rd, Spencer JP. Aminoglycosides: a practical review. Am Fam Physician . 1998;58:1811-1820.

- Teixeira B, Rodulfo H, Carreño N, et al. Aminoglycoside resistance genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Cumana, Venezuela. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo . 2016;58:13.

- Amikacin sulfate injection, USP [prescribing information]. SAGENT Pharmaceuticals. Revised February 2018. https://www.sagentpharma.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Amikacin-Sulfate-Inj-USP_PI_Feb-2018.pdf

- Gentamicin injection, USP [prescribing information]. APP Fresenius Kabi, USA, LLC. Revised October 2013.

- Zemdri® (plazomicin) [prescribing information]. Cipla USA, Inc; Approved 2018. Revised January 2020.

- Tobramycin injection, USP [prescribing information]. APP Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC. Revised October 2013.

- Eljaaly K, Alharbi A, Alshehri S, et al. Plazomicin: a novel aminoglycoside for the treatment of resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Drugs . 2019;79:243-269.

- Wagenlehner FME, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al. Once-daily plazomicin for complicated urinary tract infections. N Engl J Med . 2019;380:729-740.

- McKinnell JA, Dwyer JP, Talbot GH, et al. Plazomicin for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. N Engl J Med . 2019;380:791-793.

Faculty and Disclosures

As an organization accredited by the ACCME, Medscape, LLC requires everyone who is in a position to control the content of an education activity to disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest. The ACCME defines "relevant financial relationships" as financial relationships in any amount, occurring within the past 12 months, including financial relationships of a spouse or life partner, that could create a conflict of interest.

Medscape, LLC encourages Authors to identify investigational products or off-label uses of products regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, at first mention and where appropriate in the content.

Neil Clancy, MD

Associate Chief of VA Pittsburgh Health System (VAPHS) and Opportunistic Pathogens Associate Professor of Medicine Director, Mycology Program Chief, Infectious Diseases Section VA Pittsburgh Health Care System Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Disclosure: Neil Clancy, MD, has the following relevant financial relationships: Advisor or consultant for: Astellas; Cidara; Merck; Needham & Company; Qpex; Scynexis; Shionogi; The Medicines Company Speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Merck; T2 Biosystems Grants for clinical research from: Astellas; Cidara; Melinta; Merck

Christina T. Loguidice

Medical Writer and Medical Education Director, Medscape, LLC

Disclosure: Christina T. Loguidice has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME Reviewer

Amanda Jett, PharmD, BCACP

Disclosure: Amanda Jett, PharmD, BCACP, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

None of the nonfaculty planners for this educational activity have relevant financial relationship(s) to disclose with ineligible companies whose primary business is producing, marketing, selling, reselling, or distributing healthcare products used by or on patients.

Peer Reviewer

This activity has been peer reviewed and the reviewer has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

CME / ABIM MOC / CE

Clinical challenge: case studies in recurrent complicated utis.

- Authors: Neil Clancy, MD

CME / ABIM MOC / CE Released: 8/20/2021

- THIS ACTIVITY HAS EXPIRED FOR CREDIT

Valid for credit through: 8/20/2022 , 11:59 PM EST

Target Audience and Goal Statement

This activity is intended for infectious disease specialists, urologists, primary care physicians, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers involved in the management of recurrent complicated urinary tract infections (UTIs).

The goal of this activity is to improve clinicians' ability to evaluate the role of newer antibiotic agents for the treatment of recurrent, complicated UTIs caused by multidrug-resistant organisms.

Upon completion of this activity, participants will:

- Risk factors for multidrug-resistant infection in UTIs

- The use of an antibiogram to guide antibiotic selection

- The selection of appropriate therapies for the treatment of recurrent complicated UTIs

Disclosures

Accreditation statements.

For Physicians

Medscape, LLC designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™ . Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. Successful completion of this CME activity, which includes participation in the evaluation component, enables the participant to earn up to 1.0 MOC points in the American Board of Internal Medicine's (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) program. Participants will earn MOC points equivalent to the amount of CME credits claimed for the activity. It is the CME activity provider's responsibility to submit participant completion information to ACCME for the purpose of granting ABIM MOC credit. Aggregate participant data will be shared with commercial supporters of this activity.

Contact This Provider

For Pharmacists

Medscape, LLC designates this continuing education activity for 1.0 contact hour(s) (0.100 CEUs) (Universal Activity Number JA0007105-0000-21-450-H01-P).

For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider for this CME/CE activity noted above. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]

Instructions for Participation and Credit

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational activity. For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board. This activity is designed to be completed within the time designated on the title page; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity online during the valid credit period that is noted on the title page. To receive AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ , you must receive a minimum score of 70% on the post-test. Follow these steps to earn CME/CE credit*:

- Read about the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

- Study the educational content online or print it out.

- Online, choose the best answer to each test question. To receive a certificate, you must receive a passing score as designated at the top of the test. We encourage you to complete the Activity Evaluation to provide feedback for future programming.

You may now view or print the certificate from your CME/CE Tracker. You may print the certificate, but you cannot alter it. Credits will be tallied in your CME/CE Tracker and archived for 6 years; at any point within this time period, you can print out the tally as well as the certificates from the CME/CE Tracker. *The credit that you receive is based on your user profile.

CASE 1: PATIENT HISTORY AND PRESENTATION

Tara is a 26-year-old Korean American woman who presents to the emergency department (ED) with fevers, chills, and right-sided flank pain, which developed acutely during the previous night. After she telephoned her healthcare provider in the morning about these symptoms, she was told to go directly to the ED. She is sexually active in a jointly monogamous relationship with her boyfriend of 2 years. Her only standing medication is an oral contraceptive, which she takes regularly. Her medical history is significant for an asymptomatic horseshoe kidney that was found incidentally and approximately 1 episode of cystitis per year, characterized by dysuria. After developing symptoms of cystitis, she telephones her healthcare provider and receives a prescription for ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. She does not recall providing a urine sample for urinalysis or culture in the past. Her last episode of dysuria was 2 weeks ago, for which she took ciprofloxacin "for a couple of days." Her symptoms resolved without apparent incident. Since the onset of her presenting symptoms, she took 2 doses of ciprofloxacin that were left over from her previous prescription.

- Abbreviations

The educational activity presented above may involve simulated, case-based scenarios. The patients depicted in these scenarios are fictitious and no association with any actual patient, whether living or deceased, is intended or should be inferred. The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of Medscape, LLC, or any individuals or commercial entities that support companies that support educational programming on medscape.org. These materials may include discussion of therapeutic products that have not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, off-label uses of approved products, or data that were presented in abstract form. These data should be considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal. Readers should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this or any educational activity. A qualified healthcare professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed herein.

Medscape Education © 2021 Medscape, LLC

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Ahmed H, Farewell D, Francis NA, Paranjothy S, Butler CC. Risk of adverse outcomes following urinary tract infection in older people with renal impairment: Retrospective cohort study using linked health record data. PLoS Med. 2018; 15:(9) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002652

Bardsley A. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of urinary tract infections in older people. Nurs Older People. 2017; 29:(2)32-38 https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2017.e884

Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/The Rotherham NHS FT. Adult antimicrobial guide. 2022. https://viewer.microguide.global/BHRNFT/ADULT (accessed 13 March 2023)

Bradley S, Sheeran S. Optimal use of Antibiotics for urinary tract infections in long-term care facilities: Successful strategies prevent resident harm. Patient Safety Authority. 2017; 14:(3) http://patientsafety.pa.gov/ADVISORIES/pages/201709_UTI.aspx

Chardavoyne PC, Kasmire KE. Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescriptions for Urinary Tract Infections. West J Emerg Med. 2020; 21:(3)633-639 https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.1.45944

Deresinski S. Fosfomycin or nitrofurantoin for cystitis?. Infectious Disease Alert: Atlanta. 2018; 37:(9) http://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/fosfomycin-nitrofurantoin-cystitis/docview/2045191847

Doogue MP, Polasek TM. The ABCD of clinical pharmacokinetics. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013; 4:(1)5-7 https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098612469335

Doyle JF, Schortgen F. Should we treat pyrexia? And how do we do it?. Crit Care. 2016; 20:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1467-2

Fransen F, Melchers MJ, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW. Pharmacodynamics and differential activity of nitrofurantoin against ESBL-positive pathogens involved in urinary tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016; 71:(10)2883-2889 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkw212

Geerts AF, Eppenga WL, Heerdink R Ineffectiveness and adverse events of nitrofurantoin in women with urinary tract infection and renal impairment in primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69:(9)1701-1707 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1520-x

Greener M. Modified release nitrofurantoin in uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Nurse Prescribing. 2011; 9:(1)19-24 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2011.9.1.19

Confusion in the older patient: a diagnostic approach. 2019. https://www.gmjournal.co.uk/confusion-in-the-older-patient-a-diagnostic-approach (accessed 13 March 2023)

Haasum Y, Fastbom J, Johnell K. Different patterns in use of antibiotics for lower urinary tract infection in institutionalized and home-dwelling elderly: a register-based study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013; 69:(3)665-671 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1374-7

Health Education England. The Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice/Primary Care in England. 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf (accessed 13 March 2023)

Hoang P, Salbu RL. Updated nitrofurantoin recommendation in the elderly: A closer look at the evidence. Consult Pharm. 2016; 31:(7)381-384 https://doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2016.381

Langner JL, Chiang KF, Stafford RS. Current prescribing practices and guideline concordance for the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021; 225:(3)272.e1-272.e11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.218

Lajiness R, Lajiness MJ. 50 years on urinary tract infections and treatment-Has much changed?. Urol Nurs. 2019; 39:(5)235-239 https://doi.org/10.7257/1053-816X.2019.39.5.235

Komp Lindgren P, Klockars O, Malmberg C, Cars O. Pharmacodynamic studies of nitrofurantoin against common uropathogens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015; 70:(4)1076-1082 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dku494

Lovatt P. Legal and ethical implications of non-medical prescribing. Nurse Prescribing. 2010; 8:(7)340-343 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2010.8.7.48941

Malcolm W, Fletcher E, Kavanagh K, Deshpande A, Wiuff C, Marwick C, Bennie M. Risk factors for resistance and MDR in community urine isolates: population-level analysis using the NHS Scotland Infection Intelligence Platform. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018; 73:(1)223-230 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkx363

McKinnell JA, Stollenwerk NS, Jung CW, Miller LG. Nitrofurantoin compares favorably to recommended agents as empirical treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in a decision and cost analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011; 86:(6)480-488 https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0800

Medicines.org. Nitrofurantoin. 2022. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/search?q=Nitrofurantoin (accessed 13 March 2023)

NHS England, NHS Improvement. Online library of Quality Service Improvement and Redesign tools. SBAR communication tool – situation, background, assessment, recommendation. 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/qsir-sbar-communication-tool.pdf (accessed 13 March 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NG5: Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 (accessed 13 March 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infection (lower) – women. 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women/ (accessed 13 March 2023)

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates. 2021. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/ (accessed 13 March 2023)

O'Grady MC, Barry L, Corcoran GD, Hooton C, Sleator RD, Lucey B. Empirical treatment of urinary tract infections: how rational are our guidelines?. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019; 74:(1)214-217 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky405

O'Neill D, Branham S, Reimer A, Fitzpatrick J. Prescriptive practice differences between nurse practitioners and physicians in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in the emergency department setting. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021; 33:(3)194-199 https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000472

Royal Pharmaceutical Society. A competency framework for designated prescribing practitioners. 2019. https://www.rpharms.com/resources/frameworks (accessed 13 March 2023)

Singh N, Gandhi S, McArthur E Kidney function and the use of nitrofurantoin to treat urinary tract infections in older women. CMAJ. 2015; 187:(9)648-656 https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.150067

Stamatakos M, Sargedi C, Stasinou T, Kontzoglou K. Vesicovaginal fistula: diagnosis and management. Indian J Surg. 2014; 76:(2)131-136 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-012-0787-y

Swift A. Understanding the effects of pain and how human body responds. Nurs Times. 2018; 114:(3)22-26 https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/pain-management/understanding-the-effect-of-pain-and-how-the-human-body-responds-26-02-2018/

Taylor K. Non-medical prescribing in urinary tract infections in the community setting. Nurse Prescribing. 2016; 14:(11)566-569 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2016.14.11.566

Wijma RA, Huttner A, Koch BCP, Mouton JW, Muller AE. Review of the pharmacokinetic properties of nitrofurantoin and nitroxoline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018; 73:(11)2916-2926 https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dky255

Wijma RA, Curtis SJ, Cairns KA, Peleg AY, Stewardson AJ. An audit of nitrofurantoin use in three Australian hospitals. Infect Dis Health. 2020; 25:(2)124-129 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idh.2020.01.001

Urinary tract infection in an older patient: a case study and review

Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care

View articles

Gerri Mortimore

Senior lecturer in advanced practice, department of health and social care, University of Derby

View articles · Email Gerri

This article will discuss and reflect on a case study involving the prescribing of nitrofurantoin, by a non-medical prescriber, for a suspected symptomatic uncomplicated urinary tract infection in a patient living in a care home. The focus will be around the consultation and decision-making process of prescribing and the difficulties faced when dealing with frail, uncommunicative patients. This article will explore and critique the evidence-base, local and national guidelines, and primary research around the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nitrofurantoin, a commonly prescribed medication. Consideration of the legal, ethical and professional issues when prescribing in a non-medical capacity will also be sought, concluding with a review of the continuing professional development required to influence future prescribing decisions relating to the case study.

Urinary tract infections are common in older people. Haley Read and Gerri Mortimore describe the decision making process in the case of an older patient with a UTI

One of the growing community healthcare delivery agendas is that of the advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) role to improve access to timely, appropriate assessment and treatment of patients, in an attempt to avoid unnecessary health deterioration and/or hospitalisation ( O'Neill et al, 2021 ). The Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice/Primary Care in England recognises the application of essential skills, including sound consultation and clinical decision making for prescribing appropriate treatment ( Health Education England [HEE], 2020 ). This article will discuss and reflect on a case study involving the prescribing of nitrofurantoin by a ANP for a suspected symptomatic uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI), in a patient living in a care home. Focus will be around the consultation and decision-making process of non-medical prescribing and will explore and critique the evidence-base, examining the local and national guidelines and primary research around the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nitrofurantoin. Consideration of the legal, ethical and professional issues when prescribing in a non-medical capacity will also be sought, concluding with review of the continuing professional development required to influence future prescribing decisions relating to the case study.

Mrs M, an 87-year-old lady living in a nursing home, was referred to the community ANP by the senior carer. The presenting complaint was reported as dark, cloudy, foul-smelling urine, with new confusion and night-time hallucinations. The carer reported a history of disturbed night sleep, with hallucinations of spiders crawling in bed, followed by agitation, lethargy and poor oral intake the next morning. The SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) tool was adopted, ensuring structured and relevant communication was obtained ( NHS England and NHS Improvement, 2021 ). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence ( NICE, 2021 ) recognises that cloudy, foul-smelling urine may indicate UTI. Other symptoms include increased frequency or pressure to pass urine, dysuria, haematuria or dark coloured urine, mild fever, night-time urination, and increased sweats or chills, with lower abdominal/loin pain suggesting severe infection. NICE (2021) highlight that patients with confusion may not report UTI symptoms. This is supported by Gupta and Gupta (2019) , who recognise new confusion as hyper-delirium, which can be attributed to several causative factors including infection, dehydration, constipation and medication, among others.

UTIs are one of the most common infections worldwide ( O'Grady et al, 2019 ). Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) define UTI as a presence of colonising bacteria that cause a multitude of symptoms affecting either the upper or lower urinary tract. NICE (2021) further classifies UTIs as either uncomplicated or complicated, with complicated involving other systemic conditions or pre-existing diseases. Geerts et al (2013) postulate around 30% of females will develop a UTI at least once in their life. The incidence increases with age, with those over 65 years of age being five times more likely to develop a UTI at any point. Further increased prevalence is found in patients who live in a care home, with up to 60% of all infections caused by UTI ( Bardsley, 2017 ).

Greener (2011) reported that symptoms of UTIs are often underestimated by clinicians. A study cited by Greener (2011) found over half of GPs did not record the UTI symptoms that the patient had reported. It is, therefore, essential during the consultation to use open-ended questions, listening to the terminology of the patient or carers to clarify the symptoms and creating an objective history ( Taylor, 2016 ).

In this case, the carer highlighted that Mrs M had been treated for suspected UTI twice in the last 12 months. Greener (2011) , in their literature review of 8 Cochrane review papers and 1 systematic review, which looked at recurrent UTI incidences in general practice, found 48% of women went on to have a further episode within 12 months.

Mrs M's past medical history reviewed via the GP electronic notes included:

- Hypertension

- Diverticular disease

- Basal cell carcinoma of scalp

- Retinal vein occlusion

- Severe frailty

- Fracture of proximal end of femur

- Total left hip replacement

- Previous indwelling urinary catheter

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 2

- Urinary and faecal incontinence

- And, most recently, vesicovaginal fistula.

Bardsley (2017) identified further UTI risk factors including postmenopausal females, frailty, co-morbidity, incontinence and use of urethral catheterisation. Vesicovaginal fistulas also predispose to recurrent UTIs, due to the increase in urinary incontinence ( Stamatokos et al, 2014 ). Moreover, UTIs are common in older females living in a care home ( Bradley and Sheeran, 2017 ). They can cause severe risks to the patient if left untreated, leading to complications such as pyelonephritis or sepsis ( Ahmed et al, 2018 ).

Mrs M's medication included:

- Paracetamol 1 g as required

- Lactulose 10 ml twice daily

- Docusate 200 mg twice daily

- Epimax cream

- Colecalciferol 400 units daily

- Alendronic acid 70 mg weekly.

She did not take any herbal or over the counter preparations. Her records reported no known drug allergies; however, she was allergic to Elastoplast. A vital part of clinical history involves reviewing current prescribed and non-prescribed medications, herbal remedies and drug allergies, to prevent contraindications or reactions with potential prescribed medication ( Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2019 ). Several authors, including Malcolm et al (2018) , indicate polypharmacy as a common cause of adverse drug reactions (ADRs), worsening health and affecting a person's quality of life. NICE (2015) only recommends review of patients who are on four or more medications on each new clinical intervention, not taking into account individual drug interactions.

Due to Mrs M's lack of capacity, her social history was obtained via the electronic record and the carer. She moved to the care home 3 years ago, following respite care after her fall and hip replacement. She had never smoked or drank alcohol. Documented family history revealed stroke, ischaemic heart disease and breast cancer. Taylor (2016) reports a good thorough clinical history can equate to 90% of the working diagnosis before examination, potentially reducing unnecessary tests and investigations. This can prove challenging when the patient has confusion. It takes a more investigative approach, gaining access to medical/nursing care notes, and using family or carers to provide further collateral history ( Gupta and Gupta, 2019 ).

As per NICE (2021) guidelines, a physical examination of Mrs M was carried out. On examination it was noted that Mrs M had mild pallor with normal capillary refill time, no signs of peripheral or central cyanosis, and no clinical stigmata to note. Her heart rate was elevated at 112 beats per minute and regular, she had a normal respiration rate of 17 breaths per minute, oxygen saturations (SpO 2 ) were 98% on room air and blood pressure was 116/70 mm/Hg. Her temperature was 37.3oC. According to Doyle and Schortgen (2016) , there is no agreed level of fever; however, it becomes significant when above 38.3oC. Bardsley (2017) adds that older patients do not always present with pyrexia in UTI because of an impaired immune response.

Heart and chest sounds were normal, with no peripheral oedema. The abdomen was non-distended, soft and non-tender on palpation, with no reports of nausea, vomiting, supra-pubic tenderness or loin pain. Loin pain or suprapubic tenderness can indicate pyelonephritis ( Bardsley, 2017 ). Tachycardia, fever, confusion, drowsiness, nausea/vomiting or tachypnoea are strong predictive signs of sepsis ( NICE, 2021 ).

During the consultation, confusion and restlessness were evident. Therefore, it was difficult to ask direct questions to Mrs M regarding pain, nausea and dizziness. Non-verbal cues were considered, as changes in behaviour and restlessness can potentially highlight discomfort or pain ( Swift, 2018 ).

Mrs M's most recent blood tests indicated CKD stage 2, based on an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 82 ml/minute/1.73m 2 . The degree of renal function is vital to establish prior to any prescribing decision, because of the potential increased risk of drug toxicity ( Doogue and Polasek, 2013 ). The agreed level of mild renal impairment is when eGFR is <60 ml/minute/1.73 m 2 , with chronic renal impairment established when eGFR levels are sustained over a 3-month period ( Ahmed et al, 2018 ).

Previous urine samples of Mrs M grew Escherichia coli bacteria, sensitive to nitrofurantoin but resistant to trimethoprim. A consensus of papers, including Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) , highlight the most common pathogen for UTI as E. coli. Fransen et al (2016) indicates that increased use of empirical antibiotics has led to a prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase positive (ESBL+) bacteria that are resistant to many current antibiotics. This is not taken into account by the NICE guidelines (2021) ; however, it is discussed in local guidelines ( Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/Rotherham NHS FT, 2022 ).

Mrs M was unable to provide an uncontaminated urine sample due to incontinence. NICE (2021) advocate urine culture as a definitive diagnostic tool for UTIs; however, do not highlight how to objectively obtain this. Bardsley (2017) recognises the benefit of an uncontaminated urinalysis in symptomatic patients, stating that alongside other clinical signs, nitrates and leucocytes strongly predict the possibility of UTI. O'Grady et al (2019) points out that although NICE emphasise urine culture collection, it omits the use of urinalysis as part of the assessment.

Based on Ms M's clinical history and physical examination, a working diagnosis of suspected symptomatic uncomplicated UTI was hypothesised. A decision was made, based on the local antibiotic prescribing guidelines, as well as the NICE (2021) guidelines, to treat empirically with nitrofurantoin modified release (MR), 100 mg twice daily for 3 days, to avoid further health or systemic complications. The use of electronic prescribing was adopted as per local organisational policy and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2019) . Electronic prescribing is essential for legibility and sharing of prescribing information. It also acts as an audit on prescribing practices, providing a contemporaneous history for any potential litigation ( Lovatt, 2010 ).

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) reflect on the origins of nitrofurantoin back to the 1950s, following high penicillin usage leading to resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. Nitrofurantoin has been the first-line empirical treatment for UTIs internationally since 2010, despite other antibacterial agents being discovered ( Wijma et al, 2020 ). Mckinell et al (2011) highlight that a surge in bacterial resistance brought about interest in nitrofurantoin as a first-line option. Their systematic review of the literature indicated through a cost and efficacy decision analysis that nitrofurantoin was a low resistance and low cost risk; therefore, an effective alternative to trimethoprim or fluoroquinolones. The weakness of this paper is the lack of data on nitrofurantoin cure rates and resistance studies, demonstrating an inability to predict complete superiority of nitrofurantoin over other antibiotics. This could be down to the reduced use of nitrofurantoin treatment at the time.

Fransen et al (2016) reported that minimal pharmacodynamic knowledge of nitrofurantoin exists, despite its strong evidence-based results against most common urinary pathogens, and being around for the last 70 years. Wijma et al (2018) hypothesised this was because of the lack of drug approval requirements in the era when nitrofurantoin was first produced, and the growing incidence of antibiotic resistance. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are clinically important to guide effective drug therapy and avoid potential ADRs. Focus on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) of nitrofurantoin is needed to evaluate the correct choice for an individual patient, based on a holistic assessment ( Doogue and Polasek, 2013 ).

Nitrofurantoin is structurally made up of 4 carbon and 1 oxygen atoms forming a furan ring, connected to a nitrogroup (–NO 2 ). Its mode of action is predominantly bacteriostatic, with some bactericidal tendencies in high concentration levels ( Wijma et al, 2018 ). It works by inhibiting bacterial cell growth, breaking down its strands of DNA ( Komp Lindgren et al, 2015 ). Hoang and Salbu (2016) add that nitrofurantoin causes bacterial flavoproteins to create reactive medians that halt bacterial ribosomal proteins, rendering DNA/RNA cell wall synthesis inactive.

Nitrofurantoin is administered orally via capsules or liquid. Greener (2011) highlights the different formulations, which originally included microcrystalline tablets and now include macro-crystalline capsules. The increased size of crystals was found to slow absorption rates down ( Hoang and Salbu, 2016 ). Nitrofurantoin is predominantly absorbed via the gastro-intestinal tract, enhanced by an acidic environment. It is advised to take nitrofurantoin with food, to slow down gastric emptying ( Wijma et al, 2018 ). The maximum blood concentration of nitrofurantoin is said to be <0.6 mg/l. Lower plasma concentration equates to lower toxicity risk; therefore, nitrofurantoin is favourable over fluoroquinolones ( Komp Lindgren et al, 2015 ). Wijma et al (2020) found a reduced effect on gut flora compared to fluoroquinolones.

Distribution of nitrofurantoin is mainly via the renal medulla, with a renal bioavailability of 38.8–44%; therefore, it is specific for urinary action ( Hoang and Salbu, 2016 ). Haasum et al (2013) highlight the inability for nitrofurantoin to penetrate the prostate where bacteria concentration levels can be present. Therefore, they do not advocate the use of nitrofurantoin to treat males with UTIs, because of the risk of treatment failure and further complications of systemic infection. This did not appear to be addressed by local guidelines.

The metabolism of nitrofurantoin is not completely understood; however, Wijma et al (2018) indicate several potential metabolic antibacterial actions. Around 0.8–1.8% is metabolised into aminofurantoin, with 80.9% other unknown metabolites ( medicines.org, 2022 ). Wijma et al (2020) calls for further study into the metabolism of nitrofurantoin to aid understanding of the pharmacodynamics.

Excretion of nitrofurantoin is predominantly via urine, with a peak time of 4–5 hours, and 27–50% excreted unchanged in urine ( medicines.org, 2022 ). Komp Lindgren et al (2015) equates the fast rates of renal availability and excretion to lower toxicity risks and targeted treatment for UTI pathogens. Wijma et al (2018) found high plasma concentration levels of nitrofurantoin in renal impairment. Singh et al (2015) indicate that nitrofurantoin is mainly eliminated via glomerular filtration; therefore, its impairment presents the potential risks of treatment failure and increased ADRs. Early guidelines stipulated the need to avoid nitrofurantoin in patients with mild renal impairment, indicating the need for an eGFR of >60 ml/min due to this toxicity risk. This was based on several small studies, cited by Hoang and Salbu (2016) , looking at concentration levels rather than focused on patient treatment outcomes.

Primary research by Geerts et al (2013) involving treatment outcomes in a large cohort study, led to guidelines changing the limit to mild to moderate impairment or eGFR >45 ml/min. However, the risk of ADRs, including pulmonary fibrosis and hepatic changes, were increased in renal insufficiency with prolonged use. The study participants had a mean age of 47.8 years; therefore, the study did not indicate the effects on older patients. Singh et al (2015) presented a Canadian study, looking at treatment success with nitrofurantoin in older females, with a mean age of 79 years. It indicated effective treatment despite mild/moderate renal impairment. It did not address the levels of ADRs or hospitalisation. Ahmed et al (2018) conducted a large, UK-based, retrospective cohort study favouring use of empirical nitrofurantoin in the older population with increased risk of UTI-related hospitalisation and mild/moderate renal impairment. It concluded not treating could increase mortality and morbidity. This led to guidelines to support empirical treatment of symptomatic older patients with nitrofurantoin.

Dosing is highly variable between the local and national guidelines. Greener (2011) highlights that product information for the macro-crystalline capsules recommends 50–100 mg 4 times a day for 7 days when treating acute uncomplicated UTI. Local guidelines from Barnsley Hospital NHS FT/Rotherham NHS FT Adult antimicrobial guide (2022) stipulate 50–100 mg 4 times daily for 3 days for women, whereas NICE (2021) recommends a MR version of 100 mg twice daily for 3 days.

In a systematic literature review on the pharmacokinetics of nitrofurantoin, Wijma et al (2018) found that use of a 5–7 day course had similar strong efficacy rates, whereas 3 days did not, potentially causing treatment failure, equating to poor patient outcomes and resistant behaviour. Deresinski (2018) conducted a small, randomised controlled trial involving 377 patients either on nitrofurantoin MR 100 mg three times a day for 5 days or fosfomycin single dose treatment after urinalysis and culture. It looked at response to treatment after 28 days. Nitrofurantoin was found to have a 78% cure rate compared to 50% with fosfomycin. Therefore, these studies directly contradict current NICE and local guidelines on treatment dosing of UTI in women. More robust studies on dosing regimens are therefore required.

Fransen et al (2016) conducted a non-human pharmacodynamics study looking at time of action to treat on 11 strains of common UTI bacteria including two ESBL+. It demonstrated the kill rate for E. coli was 16–24 hours, slower than Enterobacter cloacae (6–8 hours) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (8 hours). The findings also indicated that nitrofurantoin appeared effective against ESBL+. Dosing and urine concentrations were measured, and found that 100 mg every 6 hours kept the urine concentration levels significant enough to reach peak levels. This study directly contradicted the findings of Lindgren et al (2015) , who conducted similar non-human kinetic style kill rate studies, and found nitrofurantoin's dynamic action to be within 6 hours for E. coli. Both studies have limitations in that they did not take into account human immune response effects.

Wijma et al (2020) highlighted inconsistent dosing regimens in their retrospective audit involving 150 patients treated for UTIs across three Australian secondary care facilities. The predominant dosing of nitrofurantoin was 100 mg twice daily for 5 days for women and 7 days for males. Although a small audit-based paper, it creates debate regarding the lack of clarity around the correct dosing, leaving it open to error. It therefore requires primary research into the follow up of cure rates on guideline prescribing regimens. Dose and timing remains an important issue to reduce treatment failure. It indicates the need for bacteria-dependant dosing, which currently NICE (2021) does not discuss.

Haasum et al (2013) found poor adherence to guidelines for choice and dosing in elderly patients in their Swedish register-based large population study. It highlighted high use of trimethoprim in frail older care home residents, despite guidelines recommending nitrofurantoin as first-line. A recent retrospective, observational, quantitative study by Langner et al (2021) involving 44.9 million women treated for a UTI in the USA across primary and secondary care, found an overuse of fluoroquinolones and underuse of nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim, especially by primary care physicians for older Asian and socio-economically deprived patients. Both these studies did not seek a true qualitative rationale for choices of antibiotics; therefore, limiting the findings.

Legal and ethical considerations

NMP regulation of best practice is set by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society framework (2019) , incorporating several acts of law including the medicines act 1968, and medicinal products prescribed by the Nurses Act (1992). As per Nursing Midwifery Council (2021) Code of Conduct and Health Education England (2020), ANPs have a duty of care to patients, ensuring that they work within their area of competence and recognise any limitations, demonstrating accountability for decisions made ( Lovatt, 2010 ).

Empirical treatment of UTIs is debated in the literature. O'Grady et al (2019) summarises that empirical treatment can reduce further UTI complications that can lead to acute health needs and hospitalisation, without increased risk of antibiotic resistance. Greener (2011) states that uncomplicated UTIs can be self-limiting; therefore, not always warranting antibiotic treatment if sound self-care advice is adopted. Chardavoyne and Kasmire (2020) discuss delayed prescribing, involving putting the onus on the patient and carers, which was not advisable in the case of Mrs M. Bradley and Sheeran (2017) found that three quarters of antibiotics in care home residents were prescribed inaccurately, hence recommended a watch and wait approach to treatment in the older care home resident, following implementation of a risk reduction strategy.

Taylor (2016) recommended an individual, holistic approach, incorporating ethical considerations such as choice, level of concordance, understanding and agreement of treatment choice. This can prove difficult in a case such as Mrs M. If a patient is deemed to lack capacity, a decision to act in the patient's best interest should be applied ( Gupta and Gupta, 2019 ). Therefore, understanding a patient's beliefs and values via family or carers should be explored, balancing the needs and possible outcomes. The principle of non-maleficence should be adopted, looking at risks versus benefits on prescribing the antibiotic to the individual patient ( Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2019 ).

Non-pharmacological advice was provided to the carers to ensure that Mrs M maintained good fluid intake of 2 litres in 24 hours. NICE (2021) advocates the use of written self-care advice leaflets that have been produced to educate patients and/or carers on non-pharmacological actions, supporting recovery and improving outcomes. The use of paracetamol for symptoms of fever and/or pain was also recommended for Mrs M. Prevention strategies proposed by Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) included looking at the benefits of oestrogen cream in post-menopausal women in reducing the incidence of UTIs. Cranberry juice, probiotics and vitamin C ingestion are not supported by any strong evidence base.

There is a duty of care to ensure that follow up of the patient during and after treatment is delivered by the NMP ( Chardavoyne and Kasmire, 2020 ). Clinical safety netting advice was discussed with the carers to monitor Mrs M for any deterioration, and to seek further clinical review urgently. Particular attention to signs of ADRs and sepsis, and the need for 999 response if these occurred, was advocated. A treatment plan was also sent to the GP to ensure sound communication and continuation of safe care ( Taylor, 2016 ).

Professional development issues

The extended role of prescribing brings additional responsibility, with onus on both the NMP and the employer vicariously, to ensure key skills are updated. This is where continued professional development involving research, training and knowledge is sought and applied, using evidence-based, up-to-date practice ( HEE, 2020 ). Adoption of antibiotic stewardship is highlighted by several papers including Lajiness and Lajiness (2019) . They advise nine points to consider, to increase knowledge around the actions and consequences of the drug by the prescriber. Despite no acknowledgment in NICE (2021) guidance, previous results of infections and sensitivities are also proposed as vital in antibiotic stewardship.

The use of decision support tools, proposed by Malcolm et al (2018) , involves an audit approach looking at antibiograms, that highlight local microbiology resistance patterns to aid antibiotic choices, alongside a risk reduction team strategy. Bradley and Sheeran (2017) looked at improving antibiotic use for UTI treatment in a care home in Pennsylvania. They employed a programme of monitoring and educating clinical staff, patients, carers and relatives in evidence-based self-care and clinical assessment skills over a 30-month period. It demonstrated a reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, and an improvement in monitoring symptoms and self-care practices, creating better patient outcomes. It was evaluated highly by nursing staff, who reported a sense of autonomy and confidence involving team work. Langner et al (2021) calls for further education and feedback to prescribers, involving pharmacists and microbiology data to identify and understand patterns of prescribing.

UTIs can be misdiagnosed and under- or over-treated, despite the presence of local and national guidelines. Continued monitoring of nitrofurantoin use requires priority, due to its first-line treatment status internationally, as this may increase reliance and overuse of the drug, with potential for resistant strains of bacteria becoming prevalent.

Diligent clinical assessment skills and prescribing of appropriate treatment is paramount to ensure risk of serious complications, hospitalisation and mortality are reduced, while quality of life is maintained. The use of competent clinical practice, up-to-date evidence-based knowledge, good communication and understanding of individual patient needs, and concordance are essential to make sound prescribing choices to avoid harm. As well as the prescribing of medications, the education, monitoring and follow-up of the patient and prescribing practices are equally a vital part of the autonomous role of the NMP.

KEY POINTS:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs) can be misdiagnosed and under- or over-treated, despite the presence of local and national guidelines

- The incidence of UTI increases with age, with those over 65 years of age being five times more likely to develop a UTI at any point

- Nitrofurantoin has been the first-line empirical treatment for UTIs internationally since 2010. Its mode of action is predominantly bacteriostatic, with some bactericidal tendencies in high concentration levels

- Diligent clinical assessment skills and prescribing of appropriate treatment is paramount to ensure risk of serious complications, hospitalisation and mortality are reduced, while quality of life is maintained

CPD REFLECTIVE PRACTICE:

- How can a good clinical history be gained if the patient lacks capacity?

- What factors need to be considered when safety netting in cases like this?

- What non-pharmacological advice would you give to a patient with a urinary tract infection (or their carers)?

- How will this article change your clinical practice?

A Practical Guideline on Sampling and Analysis of Urine and Blood Specimens in Urinary Tract Infections

- First Online: 08 June 2024

Cite this chapter

- Tommaso Cai 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Truls E. Bjerklund Johansen 4 , 5 , 6

18 Accesses

A urine specimen for culture should be collected prior to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy in all cases of UTI, except for uncomplicated cystitis where an empirical treatment can be administered without a urine culture. The universally accepted diagnostic criterion for a urinary tract infection based on a voided specimen is ≥10 5 CFU/mL of a single Gram-negative organism. A urine culture sample should be taken after catheter replacement in case of CAUTI. In uncomplicated infections of the upper urinary tract, urine analysis and urine culture are strongly recommended. In all patients with fever or suspected sepsis, a blood culture is strongly recommended. The aim of this chapter is to provide practical guidelines on sampling of urine and blood specimens in urinary tract infections and to give an introduction to the diagnostic verification of urinary tract infection by culture tests and urinalysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

European Association of Urology Guidelines on urological infections. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Urological-Infections-2022.pdf .

ICUD book on urogenital infections. http://www.icud.info/urogenitalinfections.html .

Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infection. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(3):699–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.014 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

McCarter YS, Sharp SE. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infections. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2009. p. 25.

Google Scholar

Platt R. Quantitative definition of bacteriuria. Am J Med. 1983;75(1B):44–52.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kunin CM. Bacteriuria, pyuria, proteinuria, hematuria, and pneumaturia. In: Kunin CM, editor. Urinary tract infections: detection, prevention, and management. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997. p. 9.

Hooton TM, Stapleton AE, Roberts PL, and Stamm WE, Comparison of microbiologic findings in paired midstream and catheter urine specimens from women with acute uncomplicated cystitis. Abstract L-609 48th annual ICAAC, Washington DC, 2008

Kass EH. Chemotherapeutic and antibiotic drugs in the management of infections of the urinary tract. Am J Med. 1955;18(5):764–81.

Stamm WE, Counts GW, Running KR, Fihn S, Turck M, Holmes KK. Diagnosis of coliform infection in acutely dysuric women. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(8):463–8.

Rubin RH, Shapiro ED, Andriole VT, Davis RJ, Stamm WE. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of urinary tract infection. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Food and Drug Administration. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15(Suppl 1):S216–27.

Opota O, Croxatto A, Prod'hom G, Greub G. Blood culture-based diagnosis of bacteraemia: state of the art. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(4):313–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.01.003 .

Lala V, Minter DA. Acute cystitis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, Santa Chiara Regional Hospital, Trento, Italy

Tommaso Cai

Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Tommaso Cai & Truls E. Bjerklund Johansen

Department of Urology, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway

Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark

Truls E. Bjerklund Johansen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tommaso Cai .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Urology, Santa Chiara Regional Hospital, Trento, Trento, Italy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cai, T., Bjerklund Johansen, T.E. (2024). A Practical Guideline on Sampling and Analysis of Urine and Blood Specimens in Urinary Tract Infections. In: Bjerklund Johansen, T.E., Cai, T. (eds) Guide to Antibiotics in Urology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92366-6_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92366-6_3

Published : 08 June 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-92365-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-92366-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

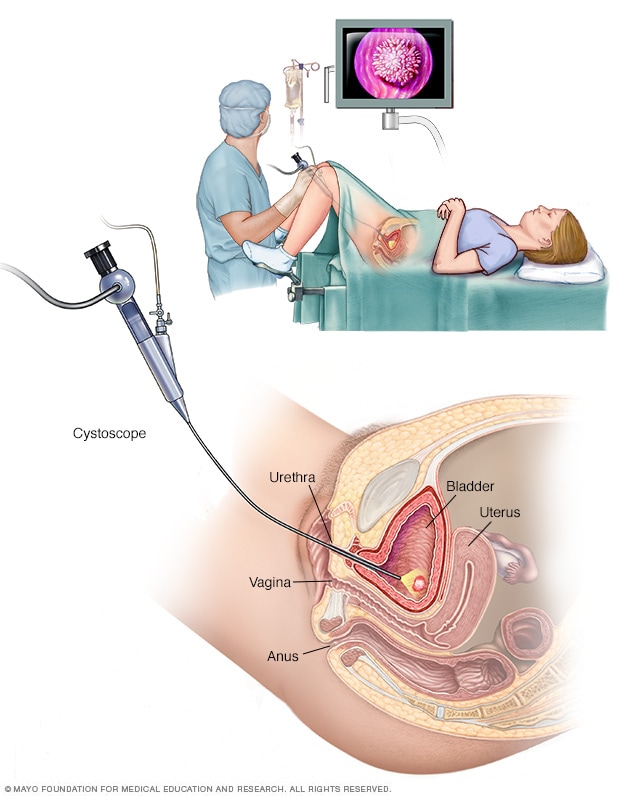

Female cystoscopy

Cystoscopy allows a health care provider to view the lower urinary tract to look for problems, such as a bladder stone. Surgical tools can be passed through the cystoscope to treat certain urinary tract conditions.

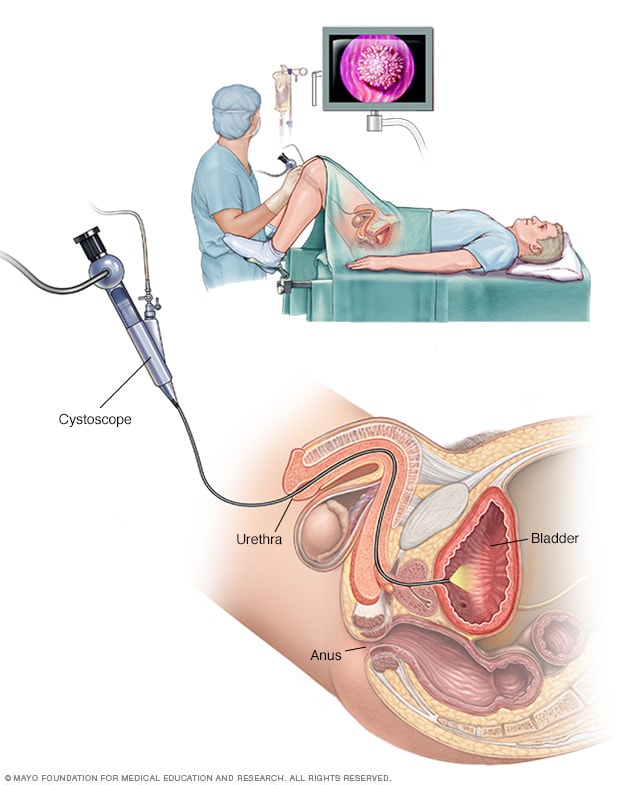

Male cystoscopy

Cystoscopy allows a health care provider to view the lower urinary tract to look for problems in the urethra and bladder. Surgical tools can be passed through the cystoscope to treat certain urinary tract conditions.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose urinary tract infections include:

- Analyzing a urine sample. Your health care provider may ask for a urine sample. The urine will be looked at in a lab to check for white blood cells, red blood cells or bacteria. You may be told to first wipe your genital area with an antiseptic pad and to collect the urine midstream. The process helps prevent the sample from being contaminated.

- Growing urinary tract bacteria in a lab. Lab analysis of the urine is sometimes followed by a urine culture. This test tells your provider what bacteria are causing the infection. It can let your provider know which medications will be most effective.

- Creating images of the urinary tract. Recurrent UTI s may be caused by a structural problem in the urinary tract. Your health care provider may order an ultrasound, a CT scan or MRI to look for this issue. A contrast dye may be used to highlight structures in your urinary tract.

- Using a scope to see inside the bladder. If you have recurrent UTI s, your health care provider may perform a cystoscopy. The test involves using a long, thin tube with a lens, called a cystoscope, to see inside the urethra and bladder. The cystoscope is inserted in the urethra and passed through to the bladder.

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Our caring team of Mayo Clinic experts can help you with your Urinary tract infection (UTI)-related health concerns Start Here

Antibiotics usually are the first treatment for urinary tract infections. Your health and the type of bacteria found in your urine determine which medicine is used and how long you need to take it.

Simple infection

Medicines commonly used for simple UTI s include:

- Trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Bactrim DS)

- Fosfomycin (Monurol)

- Nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Macrobid, Furadantin)

- Ceftriaxone

The group of antibiotics known as fluoroquinolones isn't commonly recommended for simple UTI s. These drugs include ciprofloxacin (Cipro), levofloxacin and others. The risks of these drugs generally outweigh the benefits for treating uncomplicated UTI s.

In cases of a complicated UTI or kidney infection, your health care provider might prescribe a fluoroquinolone medicine if there are no other treatment options.

Often, UTI symptoms clear up within a few days of starting treatment. But you may need to continue antibiotics for a week or more. Take all of the medicine as prescribed.

For an uncomplicated UTI that occurs when you're otherwise healthy, your health care provider may recommend a shorter course of treatment. That may mean taking an antibiotic for 1 to 3 days. Whether a short course of treatment is enough to treat your infection depends on your symptoms and medical history.

Your health care provider also may give you a pain reliever to take that can ease burning while urinating. But pain usually goes away soon after starting an antibiotic.

Frequent infections

If you have frequent UTI s, your health care provider may recommend:

- Low-dose antibiotics. You might take them for six months or longer.

- Diagnosing and treating yourself when symptoms occur. You'll also be asked to stay in touch with your provider.

- Taking a single dose of antibiotic after sex if UTI s are related to sexual activity.

- Vaginal estrogen therapy if you've reached menopause.

Severe infection

For a severe UTI , you may need IV antibiotics in a hospital.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Urinary tract infections can be painful, but you can take steps to ease discomfort until antibiotics treat the infection. Follow these tips:

- Drink plenty of water. Water helps to dilute your urine and flush out bacteria.

- Avoid drinks that may irritate your bladder. Avoid coffee, alcohol, and soft drinks containing citrus juices or caffeine until the infection has cleared. They can irritate your bladder and tend to increase the need to urinate.

- Use a heating pad. Apply a warm, but not hot, heating pad to your belly to help with bladder pressure or discomfort.

Alternative medicine

Many people drink cranberry juice to prevent UTI s. There's some indication that cranberry products, in either juice or tablet form, may have properties that fight an infection. Researchers continue to study the ability of cranberry juice to prevent UTI s, but results aren't final.

There's little harm in drinking cranberry juice if you feel it helps you prevent UTI s, but watch the calories. For most people, drinking cranberry juice is safe. However, some people report an upset stomach or diarrhea.

But don't drink cranberry juice if you're taking blood-thinning medication, such as warfarin (Jantovin).

Preparing for your appointment

Your primary care provider, nurse practitioner or other health care provider can treat most UTI s. If you have frequent UTI s or a chronic kidney infection, you may be referred to a health care provider who specializes in urinary disorders. This type of doctor is called a urologist. Or you may see a health care provider who specializes in kidney disorders. This type of doctor is called a nephrologist.

What you can do

To get ready for your appointment:

- Ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as collect a urine sample.

- Take note of your symptoms, even if you're not sure they're related to a UTI .

- Make a list of all the medicines, vitamins or other supplements that you take.

- Write down questions to ask your health care provider.

For a UTI , basic questions to ask your provider include:

- What's the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- Do I need any tests to confirm the diagnosis?

- What factors do you think may have contributed to my UTI ?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- If the first treatment doesn't work, what will you recommend next?

- Am I at risk of complications from this condition?

- What is the risk that this problem will come back?

- What steps can I take to lower the risk of the infection coming back?

- Should I see a specialist?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions as they occur to you during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider will likely ask you several questions, including:

- When did you first notice your symptoms?

- Have you ever been treated for a bladder or kidney infection?

- How severe is your discomfort?

- How often do you urinate?

- Are your symptoms relieved by urinating?

- Do you have low back pain?

- Have you had a fever?

- Have you noticed vaginal discharge or blood in your urine?

- Are you sexually active?

- Do you use contraception? What kind?

- Could you be pregnant?

- Are you being treated for any other medical conditions?

- Have you ever used a catheter?

Urinary tract infection (UTI) care at Mayo Clinic

- Partin AW, et al., eds. Infections of the urinary tract. In: Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Ferri FF. Urinary tract infection. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2022. Elsevier; 2022. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Bladder infection (urinary tract infection) in adults. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/bladder-infection-uti-in-adults. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs). The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/urinary-tract-infections. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Cai T. Recurrent uncomplicated urinary tract infections: Definitions and risk factors. GMS Infectious Diseases. 2021; doi:10.3205/id000072.

- Hooton TM, et al. Acute simple cystitis in women. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Pasternack MS. Approach to the adult with recurrent infections. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed June 14, 2022.

- Cranberry. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/cranberry. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Goebel MC, et al. The five Ds of outpatient antibiotic stewardship for urinary tract infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2021; doi:10.1128/CMR.00003-20.

- Overactive bladder (OAB): Lifestyle changes. Urology Care Foundation. https://urologyhealth.org/urologic-conditions/overactive-bladder-(oab)/treatment/lifestyle-changes. Accessed June 13, 2022.

- Nguyen H. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. May 5, 2022.

- AskMayoExpert. Urinary tract infection (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

News from Mayo Clinic

- UTI: This common infection can be serious Jan. 12, 2024, 04:24 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: 6 UTI myths and facts Feb. 02, 2023, 01:42 p.m. CDT

- 5 tips to prevent a urinary tract infection July 12, 2022, 04:41 p.m. CDT

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Home Remedies

- A Book: Taking Care of You

- Assortment of Health Products from Mayo Clinic Store

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

We’re transforming healthcare

Make a gift now and help create new and better solutions for more than 1.3 million patients who turn to Mayo Clinic each year.

Is It a Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)? What Women Should Know

BY Lisa Fields June 7, 2024

People usually feel relief when they empty their bladders—unless they have a urinary tract infection (UTI) . Instead of comfort, they may experience a burning sensation or other symptoms when they urinate, prompting them to visit the doctor.

A UTI is a bacterial infection that affects the urinary tract. Most are caused by Escherichia coli ( E. coli ), although other bacteria are sometimes responsible.

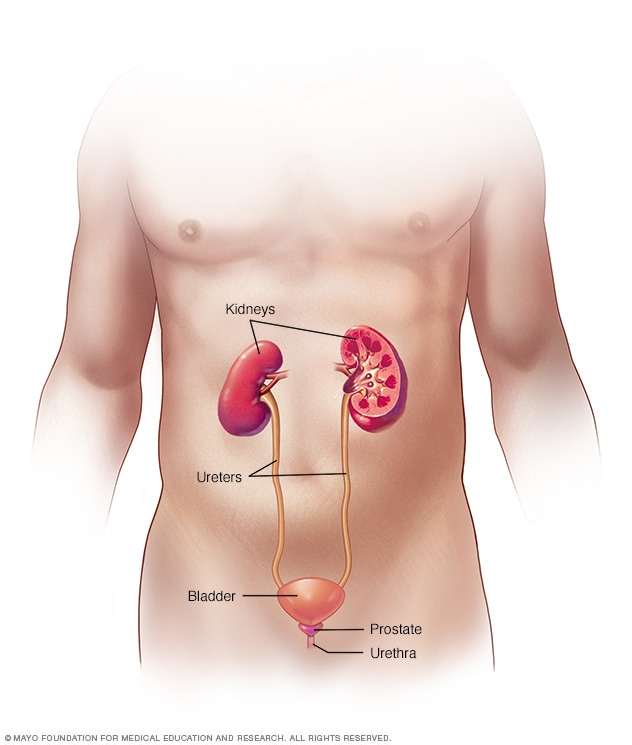

UTIs occur when bacteria enter the urinary tract through the urethra, the thin tube that runs from your bladder to the opening where urine exits your body. UTIs may affect the urethra, bladder, kidneys, or ureters, which are thin tubes that connect the kidneys to the bladder.

Urinary tract infections are much more common among women than men. “UTIs tend to increase in frequency when women enter the postmenopausal stage, but it certainly can happen across the lifespan,” says Yale Medicine urogynecologist Leslie Rickey, MD, MPH . “UTIs are impactful on people’s quality of life. They are more than just an annoyance; they can really affect people’s ability to participate in social, work, and travel activities.”

Below, Dr. Rickey shares information on how to know if you have a UTI.

1. What are the symptoms of UTIs?

People with UTIs often experience one or more of the following symptoms:

- Pain or burning during urination

- More frequent urination than usual

- Increased feelings of urinary urgency

- Releasing only a small amount of urine, despite a strong urgency

- Discomfort in the lower abdomen

- Sensation of an inability to completely empty the bladder

- Blood in the urine (if you have visible blood in your urine, you should let your doctor know as soon as possible)

It’s important to note that just having bacteria in your urine doesn’t mean you have a UTI. With a few exceptions (noted below), the presence of bacteria doesn’t automatically mean that you need antibiotics.

“If someone has bacteria in their urine and no urinary symptoms, that’s called asymptomatic bacteriuria, and it does not need to be treated in most people,” Dr. Rickey says. “In special circumstances, women may be screened for bacteriuria, such as during pregnancy and prior to undergoing certain urologic procedures.”