An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Psychiatry

- v.62(Suppl 2); 2020 Jan

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression

Manaswi gautam.

Consultant Psychiatrist Gautam Hospital and Research Center, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

Adarsh Tripathi

1 Department of Psychiatry, King George's Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Deepanjali Deshmukh

2 MGM Medical College, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India

Manisha Gaur

3 Consultant Psychologist, Gaur Mental Health Clinic, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India

INTRODUCTION

Depressive disorders are one of the most common psychiatric disorders that occur in people of all ages across all world regions. Although it may present at any age however adolescence to early adults is the most common age of onset, and females are affected two times more in comparison to the males. Depressive disorders can occur as heterogeneous conditions in clinical scenario ranging from transient minor symptoms to severe and debilitating clinical conditions, causing severe social and occupational impairments. Usually, it presents with constellations of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, physiological, interpersonal, social, and occupational symptoms. The illness can be of various severities, and a significant proportion of the patients can have recurrent illness. Depression is also highly comorbid with several psychiatric and medical illnesses such as anxiety disorders, substance use, obsessive–compulsive disorder, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular illnesses.

Major depressive disorders accounted for around 8.2% global years lived with disability (YLD) in 2010, and it was the second leading cause of the YLDs. In addition, they also contribute to the burden of several other disorders indirectly such as suicide and ischemic heart disease.[ 1 ]

EVIDENCE BASE FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY IN DEPRESSION

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most evidence-based psychological interventions for the treatment of several psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, somatoform disorder, and substance use disorder. The uses are recently extended to psychotic disorders, behavioral medicine, marital discord, stressful life situations, and many other clinical conditions.

A sufficient number of researches have been conducted and shown the efficacy of CBT in depressive disorders. A meta-analysis of 115 studies has shown that CBT is an effective treatment strategy for depression and combined treatment with pharmacotherapy is significantly more effective than pharmacotherapy alone.[ 2 ] Evidence also suggests that relapse rate of patient treated with CBT is lower in comparison to the patients treated with pharmacotherapy alone.[ 3 ]

Treatment guidelines for the depression suggest that psychological interventions are effective and acceptable strategy for treatment. The psychological interventions are most commonly used for mild-to-moderate depressive episodes. As per the prevailing situations of India with regards to significant lesser availability of trained therapist in most of the places and patients preferences, the pharmacological interventions are offered as the first-line treatment modalities for treatment of depression.

Indication for Cognitive behavior therapy as enlisted in table 1 .

Indications for cognitive behavioral therapy (situations that can call for preferred use of the psychological interventions) are

CONTRAINDICATIONS FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

There is no absolute contraindication to CBT; however, it is often reported that clients with comorbid severe personality disorders such as antisocial personality disorders and subnormal intelligence are difficult to manage through CBT. Special training and expertise may be needed for the treatment of these clients.

Patient with severe depression with psychosis and/or suicidality might be difficult to manage with CBT alone and need medications and other treatment before considering CBT. Organicity should be ruled out using clinical evaluation and relevant investigations, as and when required.

There are many advantages of CBT in depression as given in table 2

Advantages of cognitive behavioral therapy in depression

CHOICE OF TREATMENT SETTINGS

CBT can be done on an Out Patient Department (OPD) basis with regular planned sessions. Each session lasts for about 45 min–1 h depending on the suitability for both patients and therapists. In specific situations, the CBT can be delivered in inpatient settings along with treatment as usual such as adjuvant treatment in severe depression, high risk for self-harm or suicidal patients, patients with multiple medical or psychiatric comorbidities and in patients hospitalized due to social reasons.

ASSESSMENT AND EVALUATION FOR THE THERAPY

A detail diagnostic assessment is needed for the assessment of psychopathology, premorbid personality, diagnosis, severity, presence of suicidal ideations, and comorbidities. Baseline assessment of severity using a brief scale will be helpful in mutual understanding of severity before starting therapy and also to track the progress. Clients during depressive illness often fail to recognize early improvement and undermine any positive change. Objective rating scale hence helps in pointing out the progress and can also help in determining agenda during therapy process. Beck Depression Inventory (A. T. Beck, Steer, and Brown, 1996), the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1995), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression are useful rating scales for this purpose. The assessment for CBT in depression is, however, different from diagnostic assessment.

THE USE OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY ACCORDING TO SEVERITY OF DEPRESSION

Various trials have shown the benefit of combined treatment for severe depression.

Combined therapy though costlier than monotherapy it provides cost-effectiveness in the form of relapse prevention.

Number of sessions depends on patient responsiveness.

Booster sessions might be required at the intervals of the 1–12 th month as per the clinical need.

A model for reference is given in table 3

The use of cognitive behavioral therapy according to the severity of depression

The general outline of CBT for depression has been discussed in table 4

Overview of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression

CBT – Cognitive behavioral therapy

COGNITIVE MODEL FOR DEPRESSION

Cognitive theory conceptualizes that people are not influenced by the events rather the view they take of the events. It essentially means that individual differences in the maladaptive thinking process and negative appraisal of the life events lead to the development of dysfunctional cognitive reactions. This cognitive dysfunction is in turn is responsible for the rest of the symptoms in affective and behavioral domains.

Aaron beck proposed a cognitive model of depression, and it is detailed in Figure 1 . Cognitive dysfunctions are of the following categories.

Cognitive behavioral therapy model of depression

- Schema - stable internal structure of information usually formed during early life, also include core belief about self

- information processing and intermediate belief are usually interpreted as rules of living and usually expressed in terms of “if and then” sentences

- Automatic thoughts - proximally related to everyday events and in depression, often reflects cognitive triad, i.e., negative view of oneself, world, and future.

Negative cognitive triad of depression as given beck is as following:

- I am helpless (helplessness)

- The future is bleak (hopelessness)

- I am worthless (worthlessness).

CHOICE OF THE PATIENT

Patient-related factors that facilitated response are.

- Psychological mindedness of patients: Patients who are able to understand and label their feelings and emotions generally respond better to CBT. Although some patients in the course of treatment learn those skills during treatment

- Intellectual level of the patient might also affect the overall effectiveness of the treatment

- Willingness and motivation on the part of patients: Although it is not prerequisite, patients who are motivated to analyze their feelings and ready to undergo various homework show a better response to treatment

- Patient preference is single most important factor: After initial assessment of the patient those who prefer psychological treatment can be offered CBT alone or in combination depending on type of depression

- Those with mild to moderate depression CBT can be recommended as a first line of treatment

- Patients with severe depression might need combination of both CBT and medications (and or other treatments)

- Special situations such as children and adolescents, pregnancy, lactation, female in fertile age group planning for pregnancy, medical comorbidities

- Inability to tolerate psychopharmacological treatment

- The presence of significant psychosocial factors, intrapsychic conflicts, and interpersonal difficulties.

Therapist related factors

- Availability of cognitive behavioral therapist/psychiatrist

- The ability of therapist to form therapeutic alliance with the patient.

CLINICAL INTERVIEW FOR COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Symptoms and associated cognitions.

Negative automatic thoughts both trigger and enhance depression. It might be helpful to identify unhealthy automatic thoughts associated with symptoms of depression.

Some common symptoms and associated automatic thoughts are given in table 5 .

Symptoms of depression and associated cognitions

Impact on functioning

it is important to know the extent and effect of depression on the overall functioning and interpersonal relationships.

Coping strategies

Sometimes patients with depression might have adapted a coping strategies which make them feel good for short duration (e.g., alcohol consumption) but might be unhealthy in long term.

Onset of current symptoms

Patient's perception about the situation at the onset of symptoms might provide useful information about underlying cognitive distortions.

Background information

Detailed history of patient is necessary, including patients premorbid personality.

The therapist should be able to do the cognitive case conceptualization for the patient as given in Figure 2 .

Case conceptualization for the cognitive model of depression

MANAGING TREATMENT

An outline of the breakup of typical session of CBT is given in table 6 .

Session structure of cognitive behavioral therapy

Starting treatment

First treatment interview has mainly four objectives:

- To establish a warm collaborative therapeutic alliance

- To list specific problem set and associated goals

- To psycho-educate patient regarding the cognitive model and vicious cycle that maintains the depression

- Give the patient idea about further treatment procedures.

CBT can be explained in the following headings

- Behavioral interventions

Working with negative automatic thoughts

- Ending session.

The first treatment interview has four main objectives:

- To establish a warm, collaborative therapeutic alliance

- To list specific problems and associated goals, and select a first problem to tackle

- To educate the patient about the cognitive model, especially the vicious circle that maintains depression

- To give the patient first-hand experience of the focused, workman-like, empirical style of CBT.

These convey two important messages: (1) It is possible to make sense of depression; (2) there is something the patient can do about it. These messages directly address hopelessness and helplessness.

- Identifying problems and goals:-The various problems faced by patients should be included in a list which can include symptoms of depression or social problems (e.g., family conflict). Developing this list at the end of the first session helps in planning treatment goals

- Introducing cognitive model of depression:- In the first session at least a basic idea about how our cognitions affect our emotions and behavior is taught to the patient. The data provided by patient can be used to give insight into behaviors

- Where to start:-Common treatment goal is agreed upon by patient and therapist, therapeutic alliance is of key importance in CBT. Appropriate homework assignment should be given to patient according to predecided goal.

Behavioural interventions

Reducing ruminations.

It has been seen that depressed patients spend a significant amount of time and attention focusing on their shortcomings. Making patient aware of those negative ruminations and consciously diverting attention toward certain positive aspects can be taught to patients.

Monitoring activities

Loss of interest in day to day activities is central to the depression. It has been seen that early behavioral intervention has been increased sense of autonomy in the patients.

Patients are taught to record each and every activity hour by hour on the activity schedule. Each activity is rated 0–10 for Pleasure (P) and Mastery (M). P ratings indicate how enjoyable the activity was, and M ratings how much of an achievement it was. Mostly depressed patients feel low on achievement all the time. Hence, M should be explained as “achievement how you felt at the time of doing.” Patients are instructed to rate activities immediately and not retrospectively.

Example of activity schedule is

Activity Chart Write in each box, activity performed and depression rating from 0-100% (0-minimal, 100-maximum)

Planning activities

Once the patient learns to self-monitor activities each day is planned in advance.

This helps patients by:

- This provides a structure and helps with setting priorities

- This avoids the need to keep making decisions about what to do next

- This changes perception from chaos to manageable tasks

- This increases the chances that activities will be carried out

- This enhances patients’ sense of control.

A plan for activities is made in such a way that both pleasure and mastery are balanced (e.g., ironing cloths followed by listening to music). The tasks which are generally avoided by patient can be divided into graded tasks.

The patient is taught to evaluate each and every day in detail also encouraged to keep the record of unhelpful negative thoughts regarding tasks.

Other important behavioral activities are:-

- Mindfulness meditation: Helps people stay grounded in the present by keeping away from ruminations

- Successive approximation: Breaking larger tasks into smaller tasks which are easy to accomplish

- Visualizing the best part of the day

- Pleasant activity scheduling.

Scheduling an activity in near future which one can look on with mastery and with sense of achievement.

The main tool for this negative automatic thought record.

Thought Record -1

Thought Record – 2

Identifying negative automatic thoughts

Patients learn to record upsetting incidents as soon as possible after they occur (delay makes it difficult to recall thoughts and feelings accurately). They learn:

- To identify unpleasant emotions (e.g., despair, anger, guilt), signs that negative thinking is present. Emotions are rated for intensity on a 0–100 scale. These ratings (though the patient may initially find them difficult) help to make small changes in emotional state obvious when the search for alternatives to negative thoughts begins. This is important since change is rarely all-or-nothing, and small improvements may otherwise be missed

- To identify the problem situation. What was the patient doing or thinking about when the painful emotion occurred (e.g., “waiting at the supermarket checkout,” “worrying about my husband being late home”)?

- To identify negative automatic thoughts associated with the unpleasant emotions. Sessions direct the therapist towards asking: “And what went through your mind at that moment?” Patients become aware of thoughts, images, or implicit meanings that are present when emotional shifts occur, and record. Belief in each thought is also rated on a 0%–100%.

Questioning negative automatic thoughts

Therapist can help patient to discover dysfunctional automatic thoughts through “guided discovery.”

- What is evidence?

- What are alternative views?

- What are advantages and disadvantages of this way of thinking?

- What are my thinking biases?

Common cognitive distortions are

- Black– and– white (also called all– or– nothing, polarized, or dichotomous thinking): Situations viewed in only two categories instead of on a continuum. Example: “If I don’t top the exams. I’m a failure”

- Fortune-telling (also called catastrophizing): Future is predicted negatively without considering other possible, more likely outcomes. Example: “I ll be so upset, i won’t be able to function at all”

- Disqualifying or discounting the positive: The person unreasonably tell oneself that positive experiences, deeds, or qualities do not count. Example: “I cracked the examl, but that doesn’t mean I’m competent; It was a fluke”

- Emotional reasoning: One thinks something must be true because he/she “feels” (actually believe) it so strongly, ignoring or discounting evidence to the contrary. Example: “I know I successfully complete most of my tasks, but I still feel like I’ m incompetent”

- Labeling: One puts a fixed, global label on oneself or others without considering that the evidence might more reasonably lead to a less disastrous conclusion. Example: “I’m a failure. He's not good enough”

- Magnification/minimization: When one evaluates oneself, another person, or a situation, one unreasonably magnifies the negative and/or minimizes the positive. Example: “Getting a C Grade in exams proves how mediocre I am. Getting high marks doesn’t mean I’m smart”

- Selective abstraction (also called mental filter): One pays undue attention to one's negative detail instead of seeing the whole picture. Example: “Because I got just passing marks in one subject in my examinations (which also contained distinctions in other subjects) it means I’m not a good student”

- Mind reading: One believes that he/she knows what others are thinking, failing to consider other, more likely possibilities. Example: “He assumes that his boss thinks that he is a novice for this assignment”

- Overgeneralization: One makes a negative conclusion that goes far beyond the current situation. Example: “(Because I felt uncomfortable at the meeting) I don’t have what it takes to be a group leader”

- Personalization: O ne believes others are behaving negatively because of him/her, without exploring alternative explanations for their behavior. Example: “The watchman didn’t smile at me because I did something wrong”

- Imperatives (also called “Should” and “must” statements): One has a precise, fixed idea of how one or others should behave, and they overestimate how bad it is that these expectations are not met with. Example: “It's terrible that I sneeze as I am a Gym Trainer”

- Tunnel vision: One only views the negative aspects of a situation. Example: “My subordinate can’t do anything right. He's callous, casual and insensitive towards his job.”

Testing negative automatic thoughts: What can I do now?

It is important that cognitive changes that are brought out by questioning are consolidated by behavior experiments.

Ending the treatment

CBT is time-limited goal-directed form of therapy. Hence, the patient is made aware about end of treatment in advance. This can be done through the following stages.

Dysfunctional assumptions identification

Consolidating learning blueprint.

- Preparation for the setback.

Once the patient is able to identify negative automatic thoughts. Before ending treatment patient patients should be made aware about dysfunctional assumptions.

- Where did this rule come from? Identifying the source of a dysfunctional assumption (e.g., parental criticism) often helps to encourage distance by suggesting that its development is understandable, though it may no longer be relevant or useful

- In what ways is the rule unrealistic? Dysfunctional assumptions do not fit the way the world works. They operate by extremes, which are reflected in their language (always/never rather than some of the time; must/should/ought rather than want/prefer/would like)

- In what ways is the rule helpful? Dysfunctional assumptions are not usually wholly negative in their effects. For example, perfectionism may lead to genuine, high-quality performance. If such advantages are not recognized and taken into account when new assumptions are formulated, the patient may be reluctant to move forward

- In what ways is the rule unhelpful? The advantages of dysfunctional assumptions are normally outweighed by their costs. Perfectionism leads to rewards, but it also undermines satisfaction with achievements and stops people learning from constructive criticism

- What alternative rule might be more realistic and helpful? Once the old assumption has been undermined, it is helpful to formulate an explicit alternative (e.g., "It is good to do things well, but I am only human-sometimes I make mistakes"). This provides a new guideline for living, rather than simply undermining the old system

- What needs to be done to consolidate the new rule? As with negative automatic thoughts, re-evaluation is best made real through experience: Behavioral experiments.

The patient should be able to summarize whatever he has learned throughout the sessions.

The following questions might help to set the framework:

- How did my problems develop? (unhelpful beliefs and assumptions, the experiences that led to their formation, events precipitating onset)

- What kept them going? (maintenance factors)

- What did I learn from therapy that helped? Techniques (e.g., activity scheduling) and Ideas (e.g., "I can do something to influence my mood")

- What were my most unhelpful negative thoughts and assumptions? What alternatives did I find to them? (summarized in two columns)

- How can I build on what I have learned? (a solid, practical, clearly specified action plan).

Preparation for the setback

Since depression is recurring illness patient should be made aware about the possibility of relapse.

- What might lead to a setback for me? For example, future losses (e.g., children leaving home) and stresses (e.g., financial difficulties), i.e., events which impinge on patients’ vulnerabilities and are thus liable to be interpreted negatively

- What early warning signs do I need to be alert for?

- Feelings, behaviors, and symptoms that might indicate the beginning of another depression are identified and listed

- If I notice that I am becoming depressed again, what should I do? Clear simple instructions, which will make sense despite low mood, are needed here. Specific ideas and techniques summarized earlier in the blueprint should be referred to.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Get started

Autism and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Explore how autism and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) intertwine to empower growth and positive change.

Understanding Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

In the realm of autism treatment, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has emerged as a promising and effective therapeutic approach. Understanding its basics and its potential benefits for individuals with autism is an essential step towards empowering growth and development.

Basics of CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a form of psychological intervention rooted in cognitive and behavioral theories. It is highly effective in treating a broad range of emotional and mental health issues . CBT helps patients identify and challenge negative and unhelpful thoughts, focusing on the patient's current thoughts and beliefs rather than exploring the past [1].

In the context of autism, CBT focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The therapy is structured into specific phases but is also tailored to individual strengths and weaknesses. During the course of treatment, individuals with autism learn to identify and change thoughts that lead to problematic feelings or behaviors in particular situations.

How CBT Helps Individuals with Autism

Emerging evidence indicates the effectiveness of individual and group CBT for autistic individuals. Particularly, it has proven beneficial in addressing anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. Moreover, research has shown that CBT can help individuals with certain types of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) manage anxiety, cope with social situations, and improve emotional recognition.

For CBT to be effective for autistic individuals, it often requires adaptation to better tailor it to their needs and preferences. This includes accommodating core autism traits, alexithymia, difficulties with perspective-taking, and emotion regulation [3].

In conclusion, the use of CBT in the context of autism presents a promising approach to addressing the mental and emotional challenges that come with the condition. By understanding and leveraging the benefits of CBT, individuals with autism can make significant strides in managing their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, thus improving their overall quality of life.

Effectiveness of CBT for Autism

In the field of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for autism, there is significant research and ongoing study to understand the impact and effectiveness of the therapy. CBT focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and is structured into specific phases but is also tailored to individual strengths and weaknesses. Autistic individuals can learn to identify and change thoughts that lead to problem feelings or behaviors in particular situations through this therapy.

Research Findings on CBT and Autism

Emerging evidence suggests that individual and group cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can be effective for autistic individuals, particularly to address anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression. This conclusion is derived from studies that have incorporated relatively stringent standards regarding participant inclusion/exclusion criteria, delivery of manualized approaches, and assurance of therapist training and oversight.

Moreover, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trial (RCT) data, predominantly describing samples of young autistic individuals with anxiety, indicate moderate effect sizes for improvement following CBT.

It's important to note that poor mental health can impact education, employment, social connections, and independence. Rates of anxiety and affective disorders, eating disorders, psychosis, traumatic stress, deliberate and unintentional self-harm, and suicidality are higher in autistic individuals than non-autistic individuals [3].

Tailoring CBT for Autistic Individuals

Adapting CBT to better suit the needs and preferences of autistic individuals is crucial. Accommodating core autism traits, alexithymia, difficulties with perspective-taking, and emotion regulation are some of the ways CBT can be customized.

Such adaptations may involve the use of visual aids to communicate complex concepts, providing explicit instructions for homework assignments, and modifying the pace of therapy to suit the individual's learning style.

In conclusion, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) shows promising potential in helping autistic individuals manage their mental health challenges. However, it is essential to tailor the therapy to the individual's unique needs to maximize its effectiveness. Research continues in this field to further refine these therapeutic strategies and maximize the benefits for individuals with autism.

Addressing Mental Health Challenges

Individuals with autism often face a range of mental health challenges that can significantly impact their daily lives. These may include anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), both of which can be addressed through tailored Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) approaches.

Anxiety and Autism

Anxiety disorders are common among individuals with autism. In fact, rates of anxiety and other affective disorders are higher in autistic individuals than non-autistic individuals, which can impact education, employment, social connections, and independence.

Psychological interventions informed by cognitive behavioral theory have proven efficacy in treating mild-moderate anxiety and depression. They have been successfully adapted for autistic children and adults who experience disproportionately high rates of co-occurring emotional problems. Adapted Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been found to be clinically effective for common mental health problems in autistic adults and anxiety conditions in autistic children.

OCD and Autism

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is another mental health condition frequently observed in individuals with autism. OCD involves repeating patterns of thought and behavior that can cause significant distress and interfere with personal, social, and academic functioning.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been shown to help individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) reduce their Obsessive-Compulsive Behaviors (OCBs) similar to the general population. The therapy often requires adaptation to better tailor it to the needs and preferences of autistic individuals, such as accommodating core autism traits, alexithymia, difficulties with perspective-taking, and emotion regulation.

Addressing these mental health challenges through autism and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can significantly improve quality of life, social connections, and independence for those with autism. By understanding these conditions and leveraging effective therapies, we can better support individuals with autism in managing their mental health challenges.

Adapting CBT for Autism

Applying Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for autistic individuals often requires a personalized approach. Therapists must adapt strategies and techniques to accommodate the unique needs and preferences of these individuals. This section will focus on the strategies for effective therapy and overcoming communication barriers when dealing with autism and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Strategies for Effective Therapy

CBT can be adapted to suit autistic clients by incorporating clear solution-focused techniques that focus on specific experiences causing day-to-day difficulties [6]. This approach can lead to achievable goals and strategies tailored to the individual, helping to reduce anxiety and improve self-awareness. CBT techniques offer measurable differences, feedback, and summaries, providing structure and reducing anxiety for autistic clients.

Adaptations to CBT for autistic individuals include providing more sessions than standard, slowing down the pace of sessions, scaffolding emotion recognition and regulation skills, focusing on wider skills development, using visual means to share information, and involving parents or caregivers as co-therapists [3].

Overcoming Communication Barriers

Therapists working with autistic clients have reported challenges such as rigidity in thinking and pacing therapy sessions appropriately. They were relatively confident in core engagement and assessment skills but reported less confidence in using their knowledge to help this group.

In order to overcome communication barriers, therapists should be trained specifically in autism communication strategies. This can include understanding and responding to non-verbal cues, adapting language and communication style to match the individual's needs, and creating a safe and comfortable environment where the individual feels understood and respected. Visual aids, concrete examples, and technology can also be useful tools for facilitating communication.

The process of adapting CBT for autism is a key aspect of providing effective therapy. Through thoughtful adaptations and strategies, therapists can effectively help individuals with autism navigate their day-to-day challenges and improve their overall quality of life.

Enhancing Therapy for Autistic Clients

To make Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) more effective for individuals with autism, it's essential to tailor the therapy to their unique needs. This involves setting achievable goals and providing structure and support throughout the therapy.

Setting Achievable Goals

CBT for autism focuses on the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. The therapy involves setting specific goals for the course of treatment, where individuals with autism learn to identify and change thoughts that lead to problem feelings or behaviors in particular situations. It's essential to adapt these goals to accommodate the individual's core autism traits, alexithymia, difficulties with perspective-taking, and emotion regulation.

CBT can be adapted to suit autistic clients by incorporating clear solution-focused techniques that focus on specific experiences causing day-to-day difficulties. This approach can lead to achievable goals and strategies tailored to the individual, helping to reduce anxiety and improve self-awareness.

Providing Structure and Support

CBT is structured into specific phases but is also tailored to individual strengths and weaknesses. Adaptations to CBT for autistic individuals include providing more sessions than standard, slowing down the pace of sessions, scaffolding emotion recognition and regulation skills, and focusing on wider skills development. Using visual means to share information, and involving parents or caregivers as co-therapists can also be beneficial.

CBT techniques can be used to offer measurable differences, feedback, and summaries, providing structure and reducing anxiety for autistic clients.

In conclusion, enhancing CBT for autistic individuals involves a collaborative approach. By setting achievable goals and providing structured support, therapists can help clients manage anxiety, cope with social situations, and improve emotional recognition, thereby empowering them to lead more fulfilling lives.

CBT for Autism: Success Stories

The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for autism has been demonstrated through various studies and trials. The positive outcomes and improvements seen in autistic individuals undergoing CBT serve as success stories, offering hope and encouragement to others.

Case Studies and Outcomes

Several case studies have shown promising results in terms of the effectiveness of CBT for autism.

In one randomized clinical trial involving 167 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and anxiety, CBT designed specifically for children with ASD led to significantly lower anxiety scores compared to standard CBT and treatment as usual. Both types of CBT also yielded higher rates of positive treatment response than treatment as usual.

Another study focused on the modification of CBT using visualized language throughout the entire session for clients with ASD and anxiety and avoidance behavior. The modification of CBT concentrated on protocols for anxiety disorders and depression, while visualizing and systematizing "the invisible" in the conversation to help clients understand the social, cognitive, and emotional context of self and others. The preliminary conclusion indicated a significant improvement during treatment, with clients' psychological, social, and occupational ability to function improving on the Global Function Rating scale.

Impact of CBT on Daily Life

The impact of CBT on the daily lives of individuals with autism cannot be understated. Many individuals experience a significant improvement in their ability to function in their daily lives after undergoing CBT.

In fact, the Global Function Rating scale (GAF scale) value significantly improved from pre- to post-treatment for clients with ASD, anxiety, and avoidance behavior. The mean GAF scale value increased from 55.72 at pre-treatment to 73.17 at post-treatment.

These improvements can translate into noticeable changes in daily life, including increased social interaction, improved communication skills, and reduced anxiety. This can lead to better performance at school or work, healthier relationships, and overall improved quality of life.

The success stories of CBT for autism highlight the potential of this therapeutic approach in helping individuals with autism lead more fulfilling and productive lives. These stories serve as a testament to the transformative power of CBT, reinforcing its role as a valuable tool in the treatment of autism.

[1]: https://www.news-medical.net/health/Cognitive-Behavioral-Therapy-for-Autism.aspx

[2]: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/treatments/cognitive-behavior

[3]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8991669/

[4]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6150418/

[5]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5858576/

[6]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6902190/

[7]: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4670704/

Steven Zauderer

CEO of CrossRiverTherapy - a national ABA therapy company based in the USA.

Table of Contents

More autism articles.

Peptide Use in Enhancing Creativity

- Home Peptides Peptide Use in Enhancing Creativity

- No comment yet

- June 3, 2024

Are you looking to boost your creativity and enhance your cognitive abilities?

Peptides may be the solution you’ve been searching for.

In this article, we will delve into the world of peptides and their role in enhancing creativity.

From understanding the basics of peptides to exploring the benefits of peptide therapy for creativity, we will cover it all.

We will also compare the effects of peptides and psychedelics on creativity, provide tips for safe peptide use, share real-life case studies, and discuss future trends in peptide research.

Get ready to unlock your creative potential with peptides!

Understanding the Role of Peptides in Cognitive Enhancement

.jpg_00.jpeg)

Peptides play a crucial role in cognitive enhancement by regulating neurotransmitters and promoting overall brain function and cognition. These small molecules are instrumental in facilitating communication between neurons, thereby modulating the release and uptake of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and acetylcholine.

Through their impact on these fundamental neurotransmitters, peptides have the capacity to improve focus, memory , and general cognitive performance. Additionally, peptides have been observed to stimulate neuroplasticity , which is the brain’s capability to establish new neural connections and adapt to varying environments.

This ability to bolster synaptic plasticity is essential for processes such as learning, memory consolidation , and the preservation of cognitive function throughout the aging process.

What are Peptides?

Peptides are concise sequences of amino acids that function as foundational components for proteins and hold pivotal significance in a multitude of biological processes, encompassing brain health and cognitive operations .

Exploring the Basics of Peptides

Peptides are fundamental molecules composed of amino acids that play a pivotal role in protein formation, which is essential for the preservation of cognitive function and brain health.

Peptides are vital components in the body’s biological functions, serving as the foundational units for a diverse array of proteins. The process of peptide synthesis involves the linkage of amino acids through peptide bonds, yielding chains that can vary in length from a few to hundreds of amino acids. These peptide chains adopt specific three-dimensional configurations, thereby dictating their functions within the biological system.

Regarding cognitive function and brain health, peptides are implicated in neurotransmission, cell signaling, and the regulation of brain activities necessary for memory retention and overall mental well-being.

Peptide Therapy for Creativity Enhancement

.jpg_01.jpeg)

Peptide therapy has emerged as a promising methodology for cognitive enhancement , specifically targeting the augmentation of creative thinking and learning capabilities through the modulation of brain functions.

How Peptide Therapy Can Boost Creativity

Peptide therapy has the potential to enhance creativity through the optimization of brain function and the facilitation of efficient neural communication, thereby fostering creative thinking and learning processes.

This therapeutic approach targets specific peptides that have critical roles in the regulation of neurotransmitters and other signaling molecules within the brain. Through the modulation of these pivotal components, peptide therapy contributes to the improvement of the overall balance and efficacy of neural communication pathways. The enhanced communication networks within the brain subsequently lead to improved cognitive functions such as memory retention, focus, and problem-solving skills, all of which are fundamental for the cultivation of creativity. Consequently, individuals undergoing peptide therapy may witness heightened levels of inspiration, innovative thinking, and an increased capacity for learning and assimilating new information.

Benefits of Peptide Therapy for Creativity

The advantages of peptide therapy encompass a range of cognitive functions, including augmented creativity , enhanced memory , and heightened cognitive flexibility . Consequently, peptides for brain health emerge as a valuable instrument in the endeavor for creative superiority.

Improving Creative Thinking with Peptides

.jpg_10.jpeg)

Peptides such as Dihexa have demonstrated promise in enhancing creative thinking through the improvement of cognitive function and the support of overall brain health.

These peptides function by facilitating neurogenesis , which entails the generation of new nerve cells within the brain. Through the stimulation of neuronal growth and the augmentation of synaptic plasticity, they contribute to heightened learning capacities and memory retention. For instance, Dihexa has exhibited a particular affinity for targeting nerve growth factors, resulting in enhanced neuronal connections and communication. This augmentation not only benefits creative thinking but also fortifies general cognitive performance.

These peptides have the potential to shield brain cells against oxidative stress and inflammation , thereby ensuring the preservation of brain health over an extended period.

Psychedelics vs. Peptides for Enhancing Creativity

Both psychedelics and peptides present distinct avenues for augmenting creativity and cognitive function, yet they vary considerably in their mechanisms of action, safety profiles, and long-term impacts on brain function.

Comparing the Effects of Psychedelics and Peptides on Creativity

Although psychedelics can induce temporary states of heightened creativity through altered brain function, peptides offer a more sustainable and safer approach to cognitive enhancement. Unlike psychedelics, which can lead to moments of intense creativity that dissipate as the effects wear off, peptides work in a more steady and long-lasting way to support cognitive function.

Creative bursts experienced with psychedelics are often fleeting waves of inspiration, influenced by the substance’s impact on neurotransmitter activity. In contrast, peptides, such as nootropics , provide a consistent cognitive boost by nourishing the brain with essential nutrients and promoting neural health over time.

How to Use Peptides Safely for Creativity Enhancement

.jpg_11.jpeg)

The prudent utilization of peptides for enhancing creativity necessitates a comprehensive comprehension of proper administration , optimal dosage , and potential interactions with other substances to optimize advantages while mitigating risks.

Tips for Safe and Effective Peptide Use

For the safe and effective utilization of peptides, adherence to recommended guidelines for administration and dosage is paramount. Consulting healthcare professionals to oversee improvements in cognitive function is also imperative.

During the course of peptide therapy, individuals should remain vigilant for any potential side effects and promptly report them. Regular and open communication with healthcare providers is crucial for addressing any concerns that may arise and making necessary adjustments to the treatment plan.

Along with peptide therapy, maintaining a healthy lifestyle through proper nutrition and regular exercise can complement the advantages of peptides. It is important to bear in mind that the objective of peptide therapy is to optimize overall wellness and cognitive function. Therefore, monitoring progress and making appropriate modifications throughout the treatment process are vital for achieving the intended outcomes.

Case Studies: Successful Creativity Enhancement with Peptides

The efficacy of peptides in augmenting creativity and cognitive function has been substantiated through empirical case studies, elucidating tangible instances wherein individuals have derived benefits from peptide therapy for enhanced brain function.

Real-Life Examples of Peptide Use in Boosting Creativity

Various real-life examples demonstrate how individuals have utilized peptides to improve creativity and cognitive function, resulting in notable enhancements in brain health and overall mental performance.

For instance, a graphic designer incorporated a peptide regimen to overcome creative barriers and enhance concentration during challenging projects. Following several weeks of consistent peptide usage, the designer noted a significant increase in idea generation and clarity of thought, leading to the development of more innovative design concepts.

Similarly, a writer facing writer’s block turned to peptides to enhance cognitive function. The writer observed improved mental clarity and enhanced vocabulary recall, resulting in a more efficient writing process. These instances illustrate the beneficial effects of peptides on creativity and cognitive performance.

Future Trends in Peptide Research for Cognitive Enhancement

The outlook for peptide research in the realm of cognitive enhancement appears promising, as current studies continue to investigate novel peptides and their potential advantages in enhancing brain function , creativity , and overall cognitive performance .

Exploring the Potential of Peptides in Future Creativity Enhancement

The ongoing exploration of peptides presents significant promise for the enhancement of creativity in the future. Scientists are actively investigating the potential of these molecules to optimize brain function and cognitive performance.

Peptides have attracted considerable attention for their capacity to potentially improve memory, focus, and problem-solving skills . Current research endeavors are focused on elucidating the mechanisms by which peptides interact with brain receptors to activate neural pathways associated with creativity and innovation.

Furthermore, researchers are looking into the prospective applications of peptide-based therapies for combating cognitive decline and neurodegenerative conditions. By unlocking the therapeutic attributes of peptides, there is a growing sense of optimism surrounding the transformative impact these compounds could have in the realm of cognitive enhancement. This development could potentially herald a new era of interventions aimed at enhancing brain function.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

Systematic review of fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients: insights from randomized controlled trials

- Jae-Woong Park 1 ,

- Byung-Jin Park 1 ,

- Jin-Seok Lee 4 , 5 ,

- Eun-Jung Lee 2 ,

- Yo-Chan Ahn 3 &

- Chang-Gue Son ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2034-7429 4 , 5

Journal of Translational Medicine volume 22 , Article number: 529 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

34 Accesses

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a debilitating illness medically unexplained, affecting approximately 1% of the global population. Due to the subjective complaint, assessing the exact severity of fatigue is a clinical challenge, thus, this study aimed to produce comprehensive features of fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients.

We systematically extracted the data for fatigue levels of participants in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) targeting ME/CFS from PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and CINAHL throughout January 31, 2024. We normalized each different measurement to a maximum 100-point scale and performed a meta-analysis to assess fatigue severity by subgroups of age, fatigue domain, intervention, case definition, and assessment tool, respectively.

Among the total of 497 relevant studies, 60 RCTs finally met our eligibility criteria, which included a total of 7088 ME/CFS patients (males 1815, females 4532, and no information 741). The fatigue severity of the whole 7,088 patients was 77.9 (95% CI 74.7–81.0), showing 77.7 (95% CI 74.3–81.0) from 54 RCTs in 6,706 adults and 79.6 (95% CI 69.8–89.3) from 6 RCTs in 382 adolescents. Regarding the domain of fatigue, ‘cognitive’ (74.2, 95% CI 65.4–83.0) and ‘physical’ fatigue (74.3, 95% CI 68.3–80.3) were a little higher than ‘mental’ fatigue (70.1, 95% CI 64.4–75.8). The ME/CFS participants for non-pharmacological intervention (79.1, 95% CI 75.2–83.0) showed a higher fatigue level than those for pharmacological intervention (75.5, 95% CI 70.0–81.0). The fatigue levels of ME/CFS patients varied according to diagnostic criteria and assessment tools adapted in RCTs, likely from 54.2 by ICC (International Consensus Criteria) to 83.6 by Canadian criteria and 54.2 by MFS (Mental Fatigue Scale) to 88.6 by CIS (Checklist Individual Strength), respectively.

Conclusions

This systematic review firstly produced comprehensive features of fatigue severity in patients with ME/CFS. Our data will provide insights for clinicians in diagnosis, therapeutic assessment, and patient management, as well as for researchers in fatigue-related investigations.

Introduction

Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a debilitating illness characterized by core symptoms of chronic fatigue lasting for more than 6 months, unrefreshing sleep, post-exertional malaise (PEM), and cognitive dysfunction [ 1 ]. This disorder affects approximately 1% of the global population across all ages, races, and ethnic backgrounds [ 2 ]. Also, about 25 to 29% of CFS patients are in a house- or bed-bound state [ 3 ], and they have a sixfold higher risk of suicide compared to healthy subjects [ 4 ].

Indeed, besides CFS, fatigue is one of the most common morbidities even in the general population, affecting approximately 20% [ 5 ]. Additionally, for certain diseases, fatigue is a critical feature of the representative symptoms with high prevalence, for example, 50% in cancer [ 6 ], 80% in fibromyalgia [ 7 ], and 90% in major depressive disorder (MDD) [ 8 ], respectively. Then, CFS has been identified as the most severe form of medically unexplained fatigue and much more severe than other fatigue-associated diseases. Also, CFS patients appeared to have the lowest quality of life (QoL) comparing to subjects suffering from other diseases [ 9 ].

On the other hand, fatigue-related medical issues depend on the duration of the fatigue and its severity [ 10 ]. Since fatigue is a subjective symptom, the assessment of fatigue severity is a key factor for both patients and physicians [ 11 ]. To date, in order to objectify the severity of fatigue among CFS patients, an abundance of questionnaires and assessment tools have been developed, such as the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (CFQ), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI), and Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Nevertheless, for many healthcare professionals including general practitioners who care for patients with ME/CFS, the difficult process of assessing exact fatigue-related status including, in particular, the severity of fatigue is a clinical challenge due to the lack of standardized global information [ 15 ]. Although there have been numerous studies to define the characteristics of CFS, there is no data showing comprehensive features and quantified information on fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients.

Therefore, we aimed to systematically produce the features of fatigue severity and its characteristics using data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) targeting ME/CFS patients.

Data sources and search terms

In accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [ 16 ], a systematic literature survey was performed using four electronic literature databases, PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and CINAHL, throughout January 2024. The search keywords was ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ [MeSH term]. The search terms were “randomised controlled trial” [All Fields] OR “RCT” [All Fields]) AND “chronic fatigue syndrome” [Title] OR “CFS” [Title] in PubMed, while “chronic fatigue syndrome [Record title] AND randomized controlled trial [Title abstract keyword]” in the Cochrane Library. In Web of Science, the search terms were “Randomized Controlled Trial OR RCT [All Fields] and chronic fatigue syndrome OR CFS [All Fields]”, while in CINAHL, it was (“Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” OR “CFS”) AND (“Randomized Controlled Trial” OR “RCT”). The trial type was limited to RCTs, and only the English language was included.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were screened according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) RCTs or randomized controlled trials, (2) patients with ME/CFS, (3) studies that evaluate the efficacy of ME/CFS intervention, (4) studies that used fatigue-specialized measurements (CFQ; Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire, CIS; Checklist Individual Strength, MFI; Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20, FSS; Fatigue Severity Scale, FIS; Fatigue Impact Scale, MFS; Mental Fatigue Scale). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles with no full text, (2) articles where the number of participants was less than 20, (3) studies without detailed characteristics of patients, (4) studies that did not use fatigue-specialized measurements (CFQ, CIS, FSS, FIS, MFI, MFS).

Review process and data extraction

The authors conducted a search of databases to identify potentially eligible studies. Subsequently, the full texts of potentially eligible studies were independently screened and crosschecked by the authors. In line with our study's objective to analyze fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients, we included data from all participants in both the intervention and control groups at the initial enrollment time point of each RCT. We extracted the following data from each study: number of ME/CFS patients, sex information, age, ME/CFS diagnostic case definitions, fatigue assessment tools, mean and standard deviations of baseline fatigue scores derived from each assessment tool and 3 different types of fatigue domain (physical fatigue, mental fatigue, and cognitive fatigue). Also we noted details regarding treatment type and duration, publication year, and country where each study was conducted.

Assessment of study quality, heterogeneity and publication bias

To evaluate the study quality, we used the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2 (RoB2), which examines five key areas: the randomization process, deviations from planned interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and the selection of reported results [ 17 ]. The results are reported in Additional file 2 : Fig. S2. In cases of high risk of bias, a sensitivity analysis was applied (Additional file 6 : Table S3). This analysis removed high-risk bias studies to affirm the stability of our meta-analysis findings, in line with the guidelines provided by the Cochrane RoB2.

For assessing heterogeneity between studies, we employed the I 2 statistic to evaluate variability among each item. Subsequently, we chose the DerSimonian and Laird method to implement a random-effects model when heterogeneity within each item exceeded 50%, and a fixed-effects model for data showing less than 50% heterogeneity [ 18 ]. This model was chosen for its capability to account for both within-study and between-study variability in the overall analysis. Publication and reporting bias potential was evaluated through the utilization of funnel plots and Egger’s test. The results are shown in Additional file 1 : Fig. S1 and Additional file 5 : Table S2 [ 19 ]. Also, we used the PRISMA checklist to assist reviewers in understanding how the review was conducted (Additional file 8 ).

Meta-analysis for assessment of fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients

For easy and intuitive presentation of fatigue severity, baseline fatigue scores of ME/CFS patients were converted into a scale of 0 to 100 points based on the characteristics of each assessment tool (Additional file 4 : Table S1). To obtain converted scores, we first computed the mean and standard deviations of the raw scores for each treatment and control group. We then normalized these means to a scale of minimum 0 to maximum 100 points, aligning them with the scoring of each assessment tool. We used only baseline fatigue scores of the treatment and control groups because our study focused on investigating the fatigue features of ME/CFS patients rather than assessing the effectiveness of treatment. After this process, we conducted a meta-analysis, calculating and analyzing the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) of baseline fatigue scores of ME/CFS patients by age, fatigue domain, intervention type, case definitions, weighting them based on sample size (Table 2 ). We constructed a linear mixed effect model for understanding the correlation between fatigue severity and others factors such as age, continent, assessment tool, case definition and intervention (Fig. 2 C, D and Additional file 7 : Table S4). To assess the robustness of synthesized results, we also conducted an additional meta-analysis according to the results of quality assessment and publication bias. The results are in Additional file 5 : Table S2 and Additional file 6 : Table S3. All statistical analyses were performed using the “meta” package (by Guido Schwarzer) in R version 4.2.1. All analyses applied p < 0.05 for statistical significance.

General characteristics of the selected RCTs

A total of 629 articles were firstly identified from 4 database (PubMed, Cochrane databases, Web of Science, and CINAHL) and 60 articles met the inclusion criteria of this review (Fig. 1 ). In 60 RCTs, 7088 patients with ME/CFS (male 1815, female 4532 and no information: 741, mean age: 37.0 ± 10.1) participated, which were consisted of 54 RCTs for adult patients (n = 6706) and 6 RCTs for minor subjects (n = 382). Twenty-one RCTs evaluated the efficacy of pharmacological interventions, while 39 RCTs were conducted to evaluate non-pharmacological interventions (Table 1 ). The mean treatment period was 37.0 ± 10.1 weeks (data not shown). All studies were published between 2001 and January 2024 and were conducted across 15 countries. Upon a quality assessment, 45 studies (75%) were classified as having a low risk or some concerns (Additional file 2 : Fig. S2).

Flow chart of study selection diagram. n: Number of study

Overall fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS

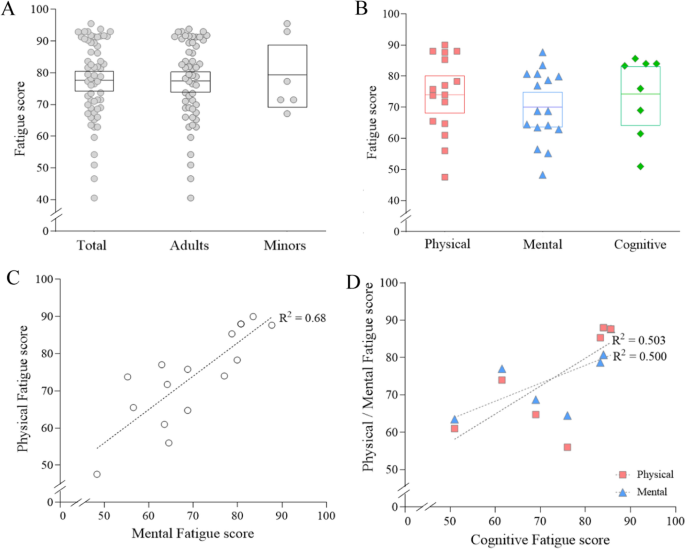

Among the 60 RCTs, the overall fatigue severity in the total 7,088 participants with ME/CFS was 77.9 (95% CI 74.7–81.0). The fatigue severity in adult patients (6706 participants from 54 RCTs) was 77.7 (95% CI 74.3–81.0), compared to 79.6 (95% CI 69.8–89.3) in 382 adolescent patients from 6 RCTS, respectively (Fig. 2 A; Table 2 ). The result of forest plot by age was shown in Additional file 3 : Fig. S3A. Unfortunately, no RCT presented fatigue severity-related data separately for each male and female.

Fatigue severity by age and domain of fatigue. Fatigue severity (out of 100) was calculated and analyzed by subgroups of age ( A ) and fatigue domains ( B ). The correlation among domains of fatigue was shown in ( C ) and ( D ). Each dot represents the value of each study included in this article. The mean score was represented by a horizontal line inside the square, while the 95% CI was depicted by the range of square. *Meta-analysis was done together for each subgroup

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by domain of fatigue

When we recalculated fatigue severity as maximum of 100 points (indicating an unendurable level) according to three domains of fatigue (physical, mental, cognitive fatigue), the ‘mental’ fatigue was the lowest (70.1, 95% CI 64.4–75.8), compared to ‘physical’ fatigue (74.3, 95% CI 68.3–80.3) and ‘cognitive’ fatigue (74.2, 95% CI 65.4–83.0), respectively (Fig. 2 B; Table 2 ). These three domain-related fatigue levels were well correlated, such as R 2 = 0.68 (p < 0.0001) between physical and mental fatigue (Fig. 2 C and D ). The result of forest plot by fatigue domain was represented in Additional file 3 : Fig. S3B.

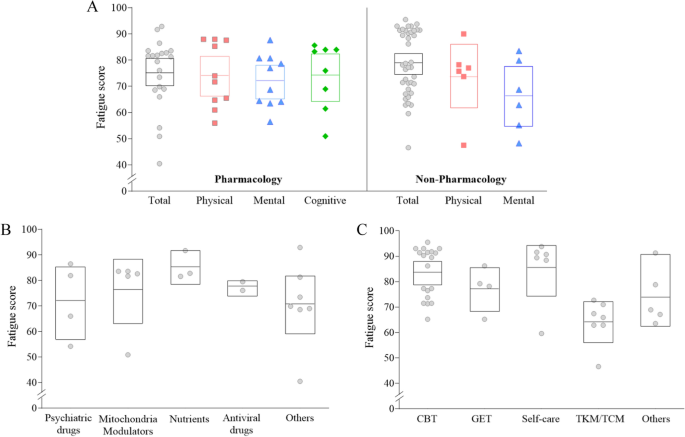

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by intervention type

When we analyzed fatigue severity of ME/CFS patients by intervention type, the total fatigue severity in participants for the non-pharmacological intervention (39 RCTs) was slightly higher (79.1, 95% CI 75.2–83.0) than those for the pharmacological intervention (75.5, 95% CI 70.0–81.0 from 21 RCTs). As we expected, the overall feature of the fatigue domain-related scores were similar with data from total the 60 RCTs, showing lower score in ‘mental fatigue’ than ‘physical’ or ‘cognitive fatigue’ in both pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention RCTs, respectively (Fig. 3 A).

Fatigue severity by intervention type. Fatigue severity (out of 100) was calculated and analyzed by intervention type (A). The results by subgroups of pharmacological and non-pharmacological research are presented in (B) and (C), respectively. Each dot indicates the value of each study included in this article. The mean score was represented by a horizontal line inside the square, while the 95% CI was depicted by the range of square. *Meta-analysis was done together for each subgroup

Regarding fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients according to kinds of pharmacological interventions, patients enrolled in nutrients-derived RCTs had the highest fatigue severity (85.5, 95% CI 79.1–92.0) followed by mitochondria modulators (76.6 95% CI 64.3–89.0), antiviral drugs (77.3, 95% CI 74.1–80.6), and psychiatric drugs (72.1, 95% CI 57.6–86.6) (Fig. 3 B; Table 2 ). Meanwhile, patients enrolled in RCTs of ‘self-care’ (85.7, 95% CI 75.6–95.8) had the highest fatigue severity, followed by cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (83.8, 95% CI 79.4–88.3), and graded exercise therapy (GET) (77.2, 95% CI 68.5–85.8), among RCTs with non-pharmacological interventions (Fig. 3 C; Table 2 ). The result of forest plot by intervention type was shown in Additional file 3 : Fig. S3C and Fig. S3D. In linear-mixed effect model,

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by case definition

From the analyses for fatigue severity of ME/CFS patients by case definition, no notable difference was observed between two most adapted tools (Table 1 ), 1994 CDC criteria (77.8, 95% CI 74.5–81.1, 55 RCTs) and Oxford criteria (77.1, 95% CI 71.0–83.1, 8 RCTs). In particular, patients enrolled by Canadian criteria exhibited the highest fatigue severity (83.6, 95% CI 69.7–97.6, 2 RCTs), and conversely, the lowest score was observed in patients by International Consensus Criteria (ICC) (54.2, 1 RCT) (Fig. 4 A; Table 2 ).

Fatigue severity by case definition of ME/CFS, continent, fatigue assessment tool and publication year. Fatigue severity (out of 100) was calculated and analyzed by case definition of ME/CFS ( A ), continent where the patients lived ( B ), fatigue assessment tool ( C ), and publication year ( D ). Each dot represents the value of each study included in this article. The mean score was represented by a horizontal line inside the square, while the 95% CI was depicted by the range of square. *Meta-analysis was done together for each subgroup

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by continents

Regarding the countries where studies were conducted, the highest fatigue severity was observed in RCTs conducted in Africa (95.5, but only one RCT) and in Europe (80.3, 95% CI 76.9–83.7, 45 RCTs), compared to the relatively lower scores in Asia (66.6, 95% CI 61.1–72.1) and North America (83.2, 95% CI 76.4–90.1) (Fig. 4 B; Table 2 ).

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by assessment tool

Fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients varied according to 6 fatigue assessment tools. Both CIS and CFQ were most frequently adapted in equally 20 RCTs (Table 1 ), and then fatigue scores were highest in patients assessed by CIS (88.6, 95% CI 85.4–91.8), but 73.2 (95% CI 70.0–76.4) in CFQ. The lowest fatigue sore was observed in patients assessed by MFS (54.2, only one RCT) and MFI (68.8, 95% CI 56.4–81.1), respectively (Fig. 4 C; Table 2 ).

Fatigue severity in participants with ME/CFS by publication year

When we compared the fatigue severity by publication year, patients participating in 11 RCTS before 2010 presented a more severe fatigue score (84.8, 95% CI 79.1–90.5), compared to 49 RCTs thereafter (76.3, 95% CI 72.7–79.8) (Fig. 4 D; Table 2 ).

In general, fatigue is the most common comorbidity of various diseases and disorders, which impairs the quality of life in diseased individuals. Fatigue sometimes plays a risky factor in the progression of diseases, such as cancer [ 20 ], fibromyalgia [ 7 ], and major depressive disorder (MDD) [ 8 ]. However, for the patients suffering from ME/CFS, fatigue itself is the inherent condition, as the most debilitating illness [ 21 ]. Due to this reason, the accurate assessment of fatigue severity is a critical issue in the diagnosis and management of ME/CFS patients in clinical fields and the process of clinical trials [ 11 ]. Nevertheless, there is no comprehensive knowledge about the global features of fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients yet.

In order to systematically investigate the features of fatigue severity, we analyzed fatigue severity-related data from RCTs in which ME/CFS patients participated globally. Due to the subjective nature of fatigue symptoms, severity assessment usually relies on patients-reported questionnaires [ 12 ]. Among the 60 RCTs finally selected, 6 types of assessment tools were adopted, such as CFQ, CIS, and MFI (Table 1 ). Each tool has the unique characteristics in terms of questionaries and scoring scales, likely CFQ consisting of 11 questionnaires giving a maximum score of 33 points [ 13 ] and MFI consisting of 20 questionnaires giving a maximum score of 100 points [ 22 ]. In this study, for easy and intuitive presentation of fatigue severity, we converted the baseline fatigue scores derived from different tools in each RCT to a maximum score of 100 points and conducted meta-analysis. From the data of 60 studies involving 7,088 ME/CFS patients, the overall fatigue level of total patients was 77.9 (95% C I 74.7–81.0) (Fig. 2 A).

Regarding the clinical relevance of the 77.9 point fatigue score, one study presented the impact on daily life performance compared to an MFI-derived average fatigue score of 73.8 ± 13.6 for 150 ME/CFS patients [ 23 ]. These patients exhibited reduced activity by 50% in 92% of them and were unable to maintain full-time work or attend school in 82%. Moreover, almost half of them (48%) were bedridden or unable to participate in any productive tasks during the period of peaked fatigue, respectively. These findings are very comparable to the known features of the impaired life activity in ME/CFS patients, with approximately 27% of individuals with severe ME/CFS being bedridden, and 57% experiencing either housebound or bedridden status for more than six years [ 3 , 24 ]. Also, 21.9% of patients with ME/CFS are working part-time jobs [ 25 ] and 53.4% of them are unemployed [ 26 ]. The medical impact of fatigue severity would vary depending on the types of diseases. For example, a study reported that fatigue scores over 60 points, assessed using the MFI in patients with Parkinson’s disease were considered to have clinically severe fatigue [ 27 ]. Also, in another study, the fatigue severity of Critical Illness Polyneuropathy (CIP) patients who were transferred from acute care Intensive Care Unit (ICU) to post-acute ICU was 55.9, assessed by MFI [ 28 ]. When comparing fatigue severity among patients with other diseases in RCT data, fatigue score was 73.4 in those with fibromyalgia [ 29 ], 50.5 in MDD [ 30 ], by MFI-assessed score. It is well acknowledged that fibromyalgia leads to severe fatigue and even has overlapping characteristics with ME/CFS [ 31 ], while depression, fatigue and/or pain are commonly accompanied within individuals suffering from MDD [ 32 , 33 ].

Fatigue is acknowledged as subjective, variable, and influenced by multiple factors, focusing on the unpleasant, distressing, and persistent feeling of tiredness, weakness, or exhaustion experienced [ 34 ]. Because of the complexity of fatigue, it is necessary to classify fatigue into various dimensions such as physical, mental, and cognitive to understand it comprehensively. When we performed the sub-analyses, the three different domains of fatigue showed the very similar score with total fatigue, likely 74.3 in physical, 70.1 in mental, and 74.2 in cognitive fatigue score, respectively (Fig. 2 B). Also, these three domain-related fatigue levels showed a highly positive correlation (Fig. 2 C, D ). According to previous research, the primary symptom of fatigue of ME/CFS impacts both physical and cognitive activities, often leading to an extended exacerbation following activities [ 35 ]. In fact, PEM, a core symptom of ME/CFS, is raised by any of physical, mental or cognitive activity [ 36 ]. Also, the majority of ME/CFS patients experience not only limitations for doing daily activities but also emotional exhaustion and prolonged cognitive activities simultaneously [ 37 ]. These results indicate that each fatigue domain cannot be interpreted as separate options but as a systemic phenomenon [ 38 ]. There is also research emphasizing that overall impairment of well-being in ME/CFS patients was related to diverse types of fatigue [ 39 ].

Fatigue prevalence and severity could be affected by gender, age, ethnicity, and cultural backgrounds [ 40 , 41 ]. In general, adults tend to exhibit higher levels of fatigue than adolescent patients due to the elderly’s underlying pathogenic conditions and psychological aspects of aging [ 42 , 43 ]. However, our data shows a 1.9-point higher fatigue score in adolescents compared to adults (Fig. 2 A; Table 2 ). This discrepancy might be attributed to the relatively fewer studies for adolescents (6 RCTs) and the enrollment of individuals with particularly significant levels of fatigue, as noted by the authors [ 44 ]. Regarding gender difference, it is well acknowledged that females are predominant and more sensitive to fatigue, with approximately 1.5-fold higher prevalence not only in the general population [ 5 ] but also in patients with ME/CFS [ 45 ], along with higher fatigue levels in females. Only 4 RCTs exclusively targeted female patients (4 RCTs, n = 326), which presented higher scores of fatigue severity 84.4 (95% CI 76.2–96.2) compared to 77.4 (95% CI 74.1–80.6) from the rest 56 RCTs (data not shown). When comparing fatigue severity by ethnicity, patients from European countries showed higher fatigue severity (80.3) than those from Asian countries (66.6), respectively (Fig. 4 B; Table 2 ). Unfortunately, our present study could not provide additional characteristics related to ethnicity or socioeconomic status due to absence of data from RCTs.

Because our study is based on the RCTs, we attempted to compare the fatigue severity of ME/CFS patients according to intervention. Fatigue severity was slightly higher in participants in non-pharmacological studies (39 RCTs, 79.1) than in those of pharmacological studies (21 RCTs, 75.5) (Fig. 3 A; Table 2 ). Due to the absence of proven therapeutics for ME/CFS, various trials have been performed since the first RCT using GET [ 46 ]. Our previous systematic review demonstrated the predominance of pharmacological RCTs in the 1990s and 2000s comparing to non-pharmacological interventions thereafter [ 47 ]. In present results, we could find that fatigue severity in participants undergoing ‘self-care’ (85.7 from 6 RCTs) and ‘CBT’ (83.8 from 19 RCTs) were relatively higher (Fig. 3 C; Table 2 ). Given the ongoing debate about which treatment methods should be used for managing ME/CFS [ 48 ], this finding might stem from that non-pharmacological interventions can be utilized for managing ME/CFS patients, particularly those experiencing severe levels of fatigue, as recommended by NICE [ 49 ]. Unlike age (R 2 = 0.003, p = 0.681), the type of intervention (R 2 = 0.327, p = 0.011) demonstrated significant influence on fatigue severity scores in ME/CFS patients according to the linear mixed-effects model (see Additional file 7 : Table S4).

Although ME/CFS has been defined as a complex neurological disease, concerns about its heterogeneity have led to the use of various case definitions. Out of the 25 currently used case definitions, we observed the application of four different case definitions in our study, including the 1994 CDC criteria (55 RCTs). Among these four case definitions, the Oxford criteria are the most lenient, primarily focusing on fatigue-related symptoms such as sleep disturbance, while the Canadian criteria encompass a broader range of pathological symptoms including anorexia, cardiovascular symptoms, and gastrointestinal symptoms [ 50 ]. The 1994 CDC criteria are generally considered moderately stricter, diagnosed by the presence of 4 or more symptoms encompassing the essential fatigue-related symptoms as well as four regional pains [ 50 ] Interestingly, participants in 2 RCTs using the Canadian criteria showed the highest average fatigue score of 83.6 (Fig. 4 A; Table 2 ). Fatigue severities also notably differed according to each assessment tool; with relatively severe levels of fatigue observed in patients of RCTs using CIS (88.6 from 20 RCTs), while the lowest levels of fatigue were seen in patients of RCTs using MFI (68.8 from 9 RCTs) and one RCT that used MFS (54.2) (Fig. 4 C; Table 2 ). CIS has been shown to effectively distinguish individuals with ME/CFS from those who do not suffer from ME/CFS based on the scores of each questionnaire’s criteria [ 51 , 52 , 53 ]. From our analyses using a linear mixed effect model, we found the notable influence between assessment tool (R 2 = 0.437, p < 0.0001) and fatigue severity, but not by case definition (R 2 = 0.084, p = 0.296) (Additional file 7 : Table S4).

Based on the publication bias and quality assessment, we investigated the robustness of synthesized results. Then an additional meta-analysis after compensation of publication bias showed overall fatigue severity 71.5 (Additional file 5 : Table S2), while fatigue severity was 77.2 after removing studies with high risk of bias (Additional file 6 : Table S3). We herein produced a comprehensive feature of fatigue levels in patients with ME/CFS, but there are some limitations in our study. In order to obtain an objectively assessed fatigue data, we extracted only from RCTs. This means that we may have excluded the patients with extremely high or low levels of fatigue severity, as they may not have been able to easily participate in RCTs or may not have been suitable for assessing interventions. Thus, the data obtained from RCTs may not fully represent the real-world features of fatigue severity in ME/CFS patients. Another limitation is that different questionnaire-based assessment tools could reflect varying levels of fatigue severity due to the varying levels of sensitivity and specificity, even for the same fatigue score when converted into a maximum of 100. This strategy may affect the relatively high level of heterogeneity in our meta-analyzed data. Additionally, there may be a potential language bias as we excluded non-English studies due to concerns about our disability and quality issues. In future studies, it may be necessary to include longitudinal cohort studies to investigate changes in fatigue severity over time.

Despite the limitations above, our results firstly produced the overall features of fatigue severity in patients with ME/CFS. Our data will provide comparative insights not only for clinicians in the processes of diagnosis, therapeutic assessment and decision-making management of patients, but also for researchers involved in fatigue-related investigations.

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this study are available in the public domain.

Jason LA, et al. Examining case definition criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Fatigue Biomed Health Behav. 2014;2(1):40–56.

Article Google Scholar