- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

What Is Creative Problem-Solving & Why Is It Important?

- 01 Feb 2022

One of the biggest hindrances to innovation is complacency—it can be more comfortable to do what you know than venture into the unknown. Business leaders can overcome this barrier by mobilizing creative team members and providing space to innovate.

There are several tools you can use to encourage creativity in the workplace. Creative problem-solving is one of them, which facilitates the development of innovative solutions to difficult problems.

Here’s an overview of creative problem-solving and why it’s important in business.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is Creative Problem-Solving?

Research is necessary when solving a problem. But there are situations where a problem’s specific cause is difficult to pinpoint. This can occur when there’s not enough time to narrow down the problem’s source or there are differing opinions about its root cause.

In such cases, you can use creative problem-solving , which allows you to explore potential solutions regardless of whether a problem has been defined.

Creative problem-solving is less structured than other innovation processes and encourages exploring open-ended solutions. It also focuses on developing new perspectives and fostering creativity in the workplace . Its benefits include:

- Finding creative solutions to complex problems : User research can insufficiently illustrate a situation’s complexity. While other innovation processes rely on this information, creative problem-solving can yield solutions without it.

- Adapting to change : Business is constantly changing, and business leaders need to adapt. Creative problem-solving helps overcome unforeseen challenges and find solutions to unconventional problems.

- Fueling innovation and growth : In addition to solutions, creative problem-solving can spark innovative ideas that drive company growth. These ideas can lead to new product lines, services, or a modified operations structure that improves efficiency.

Creative problem-solving is traditionally based on the following key principles :

1. Balance Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Creative problem-solving uses two primary tools to find solutions: divergence and convergence. Divergence generates ideas in response to a problem, while convergence narrows them down to a shortlist. It balances these two practices and turns ideas into concrete solutions.

2. Reframe Problems as Questions

By framing problems as questions, you shift from focusing on obstacles to solutions. This provides the freedom to brainstorm potential ideas.

3. Defer Judgment of Ideas

When brainstorming, it can be natural to reject or accept ideas right away. Yet, immediate judgments interfere with the idea generation process. Even ideas that seem implausible can turn into outstanding innovations upon further exploration and development.

4. Focus on "Yes, And" Instead of "No, But"

Using negative words like "no" discourages creative thinking. Instead, use positive language to build and maintain an environment that fosters the development of creative and innovative ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving and Design Thinking

Whereas creative problem-solving facilitates developing innovative ideas through a less structured workflow, design thinking takes a far more organized approach.

Design thinking is a human-centered, solutions-based process that fosters the ideation and development of solutions. In the online course Design Thinking and Innovation , Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar leverages a four-phase framework to explain design thinking.

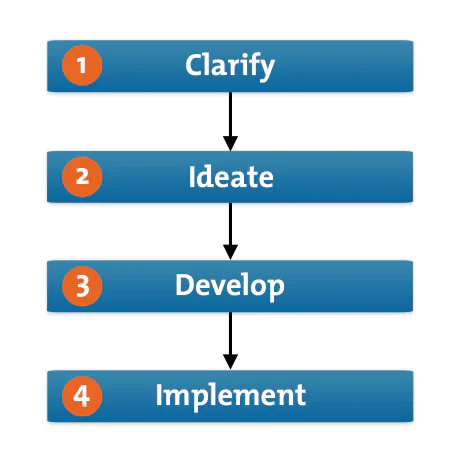

The four stages are:

- Clarify: The clarification stage allows you to empathize with the user and identify problems. Observations and insights are informed by thorough research. Findings are then reframed as problem statements or questions.

- Ideate: Ideation is the process of coming up with innovative ideas. The divergence of ideas involved with creative problem-solving is a major focus.

- Develop: In the development stage, ideas evolve into experiments and tests. Ideas converge and are explored through prototyping and open critique.

- Implement: Implementation involves continuing to test and experiment to refine the solution and encourage its adoption.

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Creative Problem-Solving Tools

While there are many useful tools in the creative problem-solving process, here are three you should know:

Creating a Problem Story

One way to innovate is by creating a story about a problem to understand how it affects users and what solutions best fit their needs. Here are the steps you need to take to use this tool properly.

1. Identify a UDP

Create a problem story to identify the undesired phenomena (UDP). For example, consider a company that produces printers that overheat. In this case, the UDP is "our printers overheat."

2. Move Forward in Time

To move forward in time, ask: “Why is this a problem?” For example, minor damage could be one result of the machines overheating. In more extreme cases, printers may catch fire. Don't be afraid to create multiple problem stories if you think of more than one UDP.

3. Move Backward in Time

To move backward in time, ask: “What caused this UDP?” If you can't identify the root problem, think about what typically causes the UDP to occur. For the overheating printers, overuse could be a cause.

Following the three-step framework above helps illustrate a clear problem story:

- The printer is overused.

- The printer overheats.

- The printer breaks down.

You can extend the problem story in either direction if you think of additional cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Break the Chains

By this point, you’ll have multiple UDP storylines. Take two that are similar and focus on breaking the chains connecting them. This can be accomplished through inversion or neutralization.

- Inversion: Inversion changes the relationship between two UDPs so the cause is the same but the effect is the opposite. For example, if the UDP is "the more X happens, the more likely Y is to happen," inversion changes the equation to "the more X happens, the less likely Y is to happen." Using the printer example, inversion would consider: "What if the more a printer is used, the less likely it’s going to overheat?" Innovation requires an open mind. Just because a solution initially seems unlikely doesn't mean it can't be pursued further or spark additional ideas.

- Neutralization: Neutralization completely eliminates the cause-and-effect relationship between X and Y. This changes the above equation to "the more or less X happens has no effect on Y." In the case of the printers, neutralization would rephrase the relationship to "the more or less a printer is used has no effect on whether it overheats."

Even if creating a problem story doesn't provide a solution, it can offer useful context to users’ problems and additional ideas to be explored. Given that divergence is one of the fundamental practices of creative problem-solving, it’s a good idea to incorporate it into each tool you use.

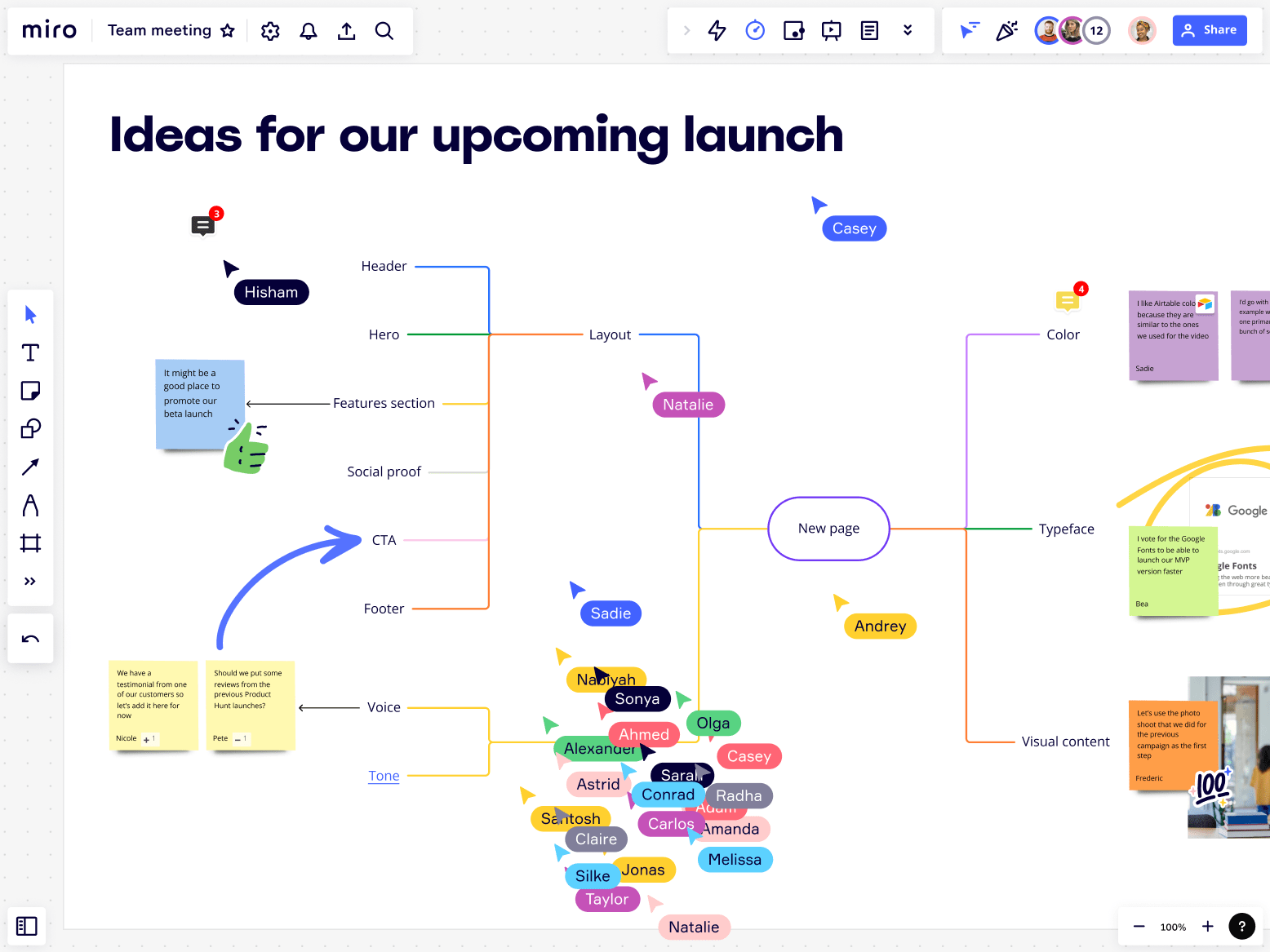

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a tool that can be highly effective when guided by the iterative qualities of the design thinking process. It involves openly discussing and debating ideas and topics in a group setting. This facilitates idea generation and exploration as different team members consider the same concept from multiple perspectives.

Hosting brainstorming sessions can result in problems, such as groupthink or social loafing. To combat this, leverage a three-step brainstorming method involving divergence and convergence :

- Have each group member come up with as many ideas as possible and write them down to ensure the brainstorming session is productive.

- Continue the divergence of ideas by collectively sharing and exploring each idea as a group. The goal is to create a setting where new ideas are inspired by open discussion.

- Begin the convergence of ideas by narrowing them down to a few explorable options. There’s no "right number of ideas." Don't be afraid to consider exploring all of them, as long as you have the resources to do so.

Alternate Worlds

The alternate worlds tool is an empathetic approach to creative problem-solving. It encourages you to consider how someone in another world would approach your situation.

For example, if you’re concerned that the printers you produce overheat and catch fire, consider how a different industry would approach the problem. How would an automotive expert solve it? How would a firefighter?

Be creative as you consider and research alternate worlds. The purpose is not to nail down a solution right away but to continue the ideation process through diverging and exploring ideas.

Continue Developing Your Skills

Whether you’re an entrepreneur, marketer, or business leader, learning the ropes of design thinking can be an effective way to build your skills and foster creativity and innovation in any setting.

If you're ready to develop your design thinking and creative problem-solving skills, explore Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Creative Problem Solving

Finding Innovative Solutions to Challenges

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine that you're vacuuming your house in a hurry because you've got friends coming over. Frustratingly, you're working hard but you're not getting very far. You kneel down, open up the vacuum cleaner, and pull out the bag. In a cloud of dust, you realize that it's full... again. Coughing, you empty it and wonder why vacuum cleaners with bags still exist!

James Dyson, inventor and founder of Dyson® vacuum cleaners, had exactly the same problem, and he used creative problem solving to find the answer. While many companies focused on developing a better vacuum cleaner filter, he realized that he had to think differently and find a more creative solution. So, he devised a revolutionary way to separate the dirt from the air, and invented the world's first bagless vacuum cleaner. [1]

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of solving problems or identifying opportunities when conventional thinking has failed. It encourages you to find fresh perspectives and come up with innovative solutions, so that you can formulate a plan to overcome obstacles and reach your goals.

In this article, we'll explore what CPS is, and we'll look at its key principles. We'll also provide a model that you can use to generate creative solutions.

About Creative Problem Solving

Alex Osborn, founder of the Creative Education Foundation, first developed creative problem solving in the 1940s, along with the term "brainstorming." And, together with Sid Parnes, he developed the Osborn-Parnes Creative Problem Solving Process. Despite its age, this model remains a valuable approach to problem solving. [2]

The early Osborn-Parnes model inspired a number of other tools. One of these is the 2011 CPS Learner's Model, also from the Creative Education Foundation, developed by Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Marie Mance, and co-workers. In this article, we'll use this modern four-step model to explore how you can use CPS to generate innovative, effective solutions.

Why Use Creative Problem Solving?

Dealing with obstacles and challenges is a regular part of working life, and overcoming them isn't always easy. To improve your products, services, communications, and interpersonal skills, and for you and your organization to excel, you need to encourage creative thinking and find innovative solutions that work.

CPS asks you to separate your "divergent" and "convergent" thinking as a way to do this. Divergent thinking is the process of generating lots of potential solutions and possibilities, otherwise known as brainstorming. And convergent thinking involves evaluating those options and choosing the most promising one. Often, we use a combination of the two to develop new ideas or solutions. However, using them simultaneously can result in unbalanced or biased decisions, and can stifle idea generation.

For more on divergent and convergent thinking, and for a useful diagram, see the book "Facilitator's Guide to Participatory Decision-Making." [3]

Core Principles of Creative Problem Solving

CPS has four core principles. Let's explore each one in more detail:

- Divergent and convergent thinking must be balanced. The key to creativity is learning how to identify and balance divergent and convergent thinking (done separately), and knowing when to practice each one.

- Ask problems as questions. When you rephrase problems and challenges as open-ended questions with multiple possibilities, it's easier to come up with solutions. Asking these types of questions generates lots of rich information, while asking closed questions tends to elicit short answers, such as confirmations or disagreements. Problem statements tend to generate limited responses, or none at all.

- Defer or suspend judgment. As Alex Osborn learned from his work on brainstorming, judging solutions early on tends to shut down idea generation. Instead, there's an appropriate and necessary time to judge ideas during the convergence stage.

- Focus on "Yes, and," rather than "No, but." Language matters when you're generating information and ideas. "Yes, and" encourages people to expand their thoughts, which is necessary during certain stages of CPS. Using the word "but" – preceded by "yes" or "no" – ends conversation, and often negates what's come before it.

How to Use the Tool

Let's explore how you can use each of the four steps of the CPS Learner's Model (shown in figure 1, below) to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

Figure 1 – CPS Learner's Model

Explore the Vision

Identify your goal, desire or challenge. This is a crucial first step because it's easy to assume, incorrectly, that you know what the problem is. However, you may have missed something or have failed to understand the issue fully, and defining your objective can provide clarity. Read our article, 5 Whys , for more on getting to the root of a problem quickly.

Gather Data

Once you've identified and understood the problem, you can collect information about it and develop a clear understanding of it. Make a note of details such as who and what is involved, all the relevant facts, and everyone's feelings and opinions.

Formulate Questions

When you've increased your awareness of the challenge or problem you've identified, ask questions that will generate solutions. Think about the obstacles you might face and the opportunities they could present.

Explore Ideas

Generate ideas that answer the challenge questions you identified in step 1. It can be tempting to consider solutions that you've tried before, as our minds tend to return to habitual thinking patterns that stop us from producing new ideas. However, this is a chance to use your creativity .

Brainstorming and Mind Maps are great ways to explore ideas during this divergent stage of CPS. And our articles, Encouraging Team Creativity , Problem Solving , Rolestorming , Hurson's Productive Thinking Model , and The Four-Step Innovation Process , can also help boost your creativity.

See our Brainstorming resources within our Creativity section for more on this.

Formulate Solutions

This is the convergent stage of CPS, where you begin to focus on evaluating all of your possible options and come up with solutions. Analyze whether potential solutions meet your needs and criteria, and decide whether you can implement them successfully. Next, consider how you can strengthen them and determine which ones are the best "fit." Our articles, Critical Thinking and ORAPAPA , are useful here.

4. Implement

Formulate a plan.

Once you've chosen the best solution, it's time to develop a plan of action. Start by identifying resources and actions that will allow you to implement your chosen solution. Next, communicate your plan and make sure that everyone involved understands and accepts it.

There have been many adaptations of CPS since its inception, because nobody owns the idea.

For example, Scott Isaksen and Donald Treffinger formed The Creative Problem Solving Group Inc . and the Center for Creative Learning , and their model has evolved over many versions. Blair Miller, Jonathan Vehar and Roger L. Firestien also created their own version, and Dr Gerard J. Puccio, Mary C. Murdock, and Marie Mance developed CPS: The Thinking Skills Model. [4] Tim Hurson created The Productive Thinking Model , and Paul Reali developed CPS: Competencies Model. [5]

Sid Parnes continued to adapt the CPS model by adding concepts such as imagery and visualization , and he founded the Creative Studies Project to teach CPS. For more information on the evolution and development of the CPS process, see Creative Problem Solving Version 6.1 by Donald J. Treffinger, Scott G. Isaksen, and K. Brian Dorval. [6]

Creative Problem Solving (CPS) Infographic

See our infographic on Creative Problem Solving .

Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

There have been many adaptations of the original Osborn-Parnes model, but they all involve a clear structure of identifying the problem, generating new ideas, evaluating the options, and then formulating a plan for successful implementation.

[1] Entrepreneur (2012). James Dyson on Using Failure to Drive Success [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 27, 2022.]

[2] Creative Education Foundation (2015). The CPS Process [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022.]

[3] Kaner, S. et al. (2014). 'Facilitator′s Guide to Participatory Decision–Making,' San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

[4] Puccio, G., Mance, M., and Murdock, M. (2011). 'Creative Leadership: Skils That Drive Change' (2nd Ed.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[5] OmniSkills (2013). Creative Problem Solving [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 26, 2022].

[6] Treffinger, G., Isaksen, S., and Dorval, B. (2010). Creative Problem Solving (CPS Version 6.1). Center for Creative Learning, Inc. & Creative Problem Solving Group, Inc. Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Simplex thinking.

8 Steps for Solving Complex Problems

Book Insights

Theory U: Leading From the Future as It Emerges

C. Otto Scharmer

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

The Objective Leader

6 Ways to Energize Your Workplace

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Generate ideas with scamper.

Brainstorming Improvements to Your Goods and Services

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Ge-mckinsey matrix.

Determining Investment Priorities

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Cognitive Trick for Solving Problems Creatively

- Theodore Scaltsas

Mental biases can actually help.

Many experts argue that creative thinking requires people to challenge their preconceptions and assumptions about the way the world works. One common claim, for example, is that the mental shortcuts we all rely on to solve problems get in the way of creative thinking. How can you innovate if your thinking is anchored in past experience?

- TS Theodore Scaltsas is a Chaired Professor in Classical Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland.

Partner Center

What is creative problem-solving?

Table of Contents

An introduction to creative problem-solving.

Creative problem-solving is an essential skill that goes beyond basic brainstorming . It entails a holistic approach to challenges, melding logical processes with imaginative techniques to conceive innovative solutions. As our world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, the ability to think creatively and solve problems with fresh perspectives becomes invaluable for individuals, businesses, and communities alike.

Importance of divergent and convergent thinking

At the heart of creative problem-solving lies the balance between divergent and convergent thinking. Divergent thinking encourages free-flowing, unrestricted ideation, leading to a plethora of potential solutions. Convergent thinking, on the other hand, is about narrowing down those options to find the most viable solution. This dual approach ensures both breadth and depth in the problem-solving process.

Emphasis on collaboration and diverse perspectives

No single perspective has a monopoly on insight. Collaborating with individuals from different backgrounds, experiences, and areas of expertise offers a richer tapestry of ideas. Embracing diverse perspectives not only broadens the pool of solutions but also ensures more holistic and well-rounded outcomes.

Nurturing a risk-taking and experimental mindset

The fear of failure can be the most significant barrier to any undertaking. It's essential to foster an environment where risk-taking and experimentation are celebrated. This involves viewing failures not as setbacks but as invaluable learning experiences that pave the way for eventual success.

The role of intuition and lateral thinking

Sometimes, the path to a solution is not linear. Lateral thinking and intuition allow for making connections between seemingly unrelated elements. These 'eureka' moments often lead to breakthrough solutions that conventional methods might overlook.

Stages of the creative problem-solving process

The creative problem-solving process is typically broken down into several stages. Each stage plays a crucial role in understanding, addressing, and resolving challenges in innovative ways.

Clarifying: Understanding the real problem or challenge

Before diving into solutions, one must first understand the problem at its core. This involves asking probing questions, gathering data, and viewing the challenge from various angles. A clear comprehension of the problem ensures that effort and resources are channeled correctly.

Ideating: Generating diverse and multiple solutions

Once the problem is clarified, the focus shifts to generating as many solutions as possible. This stage champions quantity over quality, as the aim is to explore the breadth of possibilities without immediately passing judgment.

Developing: Refining and honing promising solutions

With a list of potential solutions in hand, it's time to refine and develop the most promising ones. This involves evaluating each idea's feasibility, potential impact, and any associated risks, then enhancing or combining solutions to maximize effectiveness.

Implementing: Acting on the best solutions

Once a solution has been honed, it's time to put it into action. This involves planning, allocating resources, and monitoring the results to ensure the solution is effectively addressing the problem.

Techniques for creative problem-solving

Solving complex problems in a fresh way can be a daunting task to start on. Here are a few techniques that can help kickstart the process:

Brainstorming

Brainstorming is a widely-used technique that involves generating as many ideas as possible within a set timeframe. Variants like brainwriting (where ideas are written down rather than spoken) and reverse brainstorming (thinking of ways to cause the problem) can offer fresh perspectives and ensure broader participation.

Mind mapping

Mind mapping is a visual tool that helps structure information, making connections between disparate pieces of data. It is particularly useful in organizing thoughts, visualizing relationships, and ensuring a comprehensive approach to a problem.

SCAMPER technique

SCAMPER stands for Substitute, Combine, Adapt, Modify, Put to another use, Eliminate, and Reverse. This technique prompts individuals to look at existing products, services, or processes in new ways, leading to innovative solutions.

Benefits of creative problem-solving

Creative problem-solving offers numerous benefits, both at the individual and organizational levels. Some of the most prominent advantages include:

Finding novel solutions to old problems

Traditional problems that have resisted conventional solutions often succumb to creative approaches. By looking at challenges from fresh angles and blending different techniques, we can unlock novel solutions previously deemed impossible.

Enhanced adaptability in changing environments

In our rapidly evolving world, the ability to adapt is critical. Creative problem-solving equips individuals and organizations with the agility to pivot and adapt to changing circumstances, ensuring resilience and longevity.

Building collaborative and innovative teams

Teams that embrace creative problem-solving tend to be more collaborative and innovative. They value diversity of thought, are open to experimentation, and are more likely to challenge the status quo, leading to groundbreaking results.

Fostering a culture of continuous learning and improvement

Creative problem-solving is not just about finding solutions; it's also about continuous learning and improvement. By encouraging an environment of curiosity and exploration, organizations can ensure that they are always at the cutting edge, ready to tackle future challenges head-on.

Get on board in seconds

Join thousands of teams using Miro to do their best work yet.

Module 5: Thinking and Analysis

Solving problems creatively, learning outcomes.

- Describe the role of creative thinking skills in problem-solving

Problem-Solving with Creative Thinking

Creative problem-solving is a type of problem-solving. It involves searching for new and novel solutions to problems. Unlike critical thinking, which scrutinizes assumptions and uses reasoning, creative thinking is about generating alternative ideas—practices and solutions that are unique and effective. It’s about facing sometimes muddy and unclear problems and seeing how things can be done differently—how new solutions can be imagined. [1]

You have to remain open-minded, focus on your organizational skills, and learn to communicate your ideas well when you are using creative thinking to solve problems. If an employee at a café you own suggests serving breakfast in addition to the already-served lunch and dinner, keeping an open mind means thinking through the benefits of this new plan (e.g., potential new customers and increased profits) instead of merely focusing on the possible drawbacks (e.g., possible scheduling problems, added start-up costs, loss of lunch business). Implementing this plan would mean a new structure for buying, workers’ schedules and pay, and advertising, so you would have to organize all these component areas. And finally, you would need to communicate your ideas on how to make this new plan work not only to the staff who will work the new shift, but also to the public who frequent your café and the others you want to encourage to try your new hours.

We need creative solutions throughout the workplace—whether board room, emergency room, or classroom. It was no fluke that the 2001 revised Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy, originally developed in 1948, placed a new word at the apex— creating . That creating is the highest level of thinking skills.

Bloom’s Taxonomy is an important learning theory used by psychologists, cognitive scientists, and educators to demonstrate levels of thinking. Many assessments and lessons you’ve seen during your schooling have likely been arranged with Bloom’s in mind. Researchers recently revised it to place creativity—invention—as the highest level

“Because we’ve always done it that way” is not a valid reason to not try a new approach. It may very well be that the old process is a very good way to do things, but it also may just be that the old, comfortable routine is not as effective and efficient as a new process could be.

The good news is that we can always improve upon our problem-solving and creative-thinking skills—even if we don’t consider ourselves to be artists or creative. The following information may surprise and encourage you!

- Creative thinking (a companion to critical thinking) is an invaluable skill for college students. It’s important because it helps you look at problems and situations from a fresh perspective. Creative thinking is a way to develop novel or unorthodox solutions that do not depend wholly on past or current solutions. It’s a way of employing strategies to clear your mind so that your thoughts and ideas can transcend what appear to be the limitations of a problem. Creative thinking is a way of moving beyond barriers. [2]

- As a creative thinker, you are curious, optimistic, and imaginative. You see problems as interesting opportunities, and you challenge assumptions and suspend judgment. You don’t give up easily. You work hard. [3]

Is this you? Even if you don’t yet see yourself as a competent creative thinker or problem-solver, you can learn solid skills and techniques to help you become one.

Creative Problem-Solving: Fiction and Facts

As you continue to develop your creative thinking skills, be alert to perceptions about creative thinking that could slow down progress. Remember that creative thinking and problem-solving are ways to transcend the limitations of a problem and see past barriers. It’s a way to think outside the box.

creative problem-solving: a practice that seeks new and novel solutions to problems, often by using imagination rather than linear reason

- "Critical and Creative Thinking, MA." University of Massachusetts Boston . 2016. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Mumaw, Stefan. "Born This Way: Is Creativity Innate or Learned?" Peachpit. Pearson, 27 Dec 2012. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Harris, Robert. "Introduction to Creative Thinking." Virtual Salt. 2 Apr 2012. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- College Success. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- College Success. Authored by : Amy Baldwin. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/7-2-creative-thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Text adaptation. Authored by : Claire. Provided by : Ivy Tech. Located at : http://ivytech.edu/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Camp Invention (K-6th)

- Camp Invention Connect (K-6th)

- Refer a Friend Rewards Program

- Club Invention (1st-6th)

- Leaders-in-Training (7th-9th)

- Leadership Intern Program (High School & College Students)

- About the Educators

- FAQs for Parents

- Parent Resource Center

- Our Programs

- Find a Program

- Professional Development

- Resources for Educators

- FAQs for Educators

- Program Team Resource Center

- Plan Your Visit

- Inductee Search

- Nominate an Inventor

- Newest Inductees

- Induction Ceremony

- Our Inductees

- Apply for the Collegiate Inventors Competition

- CIC Judging

- Meet the Finalists

- Past CIC Winners

- FAQs for Collegiate Inventors

- Collegiate Inventors Competition

- Register for 2024 Camp

- Learning Resources

- Sponsor and Donate

Why Creative Problem Solving Requires Both Convergent and Divergent Thinking

When it comes to developing creative ideas, often we are given platitudes, like “turn the problem upside down” and “think outside the box,” that sound nice but aren’t exactly helpful. Fortunately, by using the proven method of Creative Problem Solving (CPS), anyone can innovate.

What is Creative Problem Solving?

According to influential CPS educator Ruth Noller, CPS is best understood as a combination of its three parts :

Creative — specifies elements of newness, innovation and novelty

Problem — refers to any situation that presents a challenge, offers an opportunity or represents a troubling concern

Solving — means devising ways to answer, to meet or to satisfy a situation by changing self or situation While there exist many different methods of implementing CPS, a majority promote two distinct methods of thought: convergent and divergent thinking. While you might have come across these terms before, read below for a refresher!

Convergent and Divergent Thinking

Convergent thinking embraces logic to identify and analyze the best solution from an existing list of answers. It’s important to note that this method leaves no room for uncertainty — answers are either right or wrong. Because of this, the more knowledge someone has of a subject, the more accurately they are able to answer clearly defined questions. In contrast, divergent thinking involves solving a problem using methods that deviate from commonly used or existing strategies. In this case, an individual creates many different answers using the information available to them. Often, solutions produced by this type of thinking are unique and surprising.

The Best of Both Worlds

When it comes to solving the types of problems that regularly arise in the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) fields, it is sometimes assumed that convergent thinking should be avoided. On the surface, this makes sense, as complex problems often require novel solutions. Is there anything wrong with solely embracing divergent thinking strategies? Simply put, the answer is yes. Using divergent thinking on its own might produce unique solutions, but in extreme cases, these might not be grounded in reality. For example, let’s say you want to create a vehicle that runs using clean energy. Without using convergent thinking to first understand the problem, a great deal of time could be wasted trying solutions that have no chance of working. Powering a vehicle using cotton candy or mustard will do nothing, beyond making a mess. Instead, using convergent thinking to first identify a promising area to explore (biodiesel, hydrogen, electricity, etc.), will prevent a lot of frustration and loss of time. While this is of course an extreme example, it shows the importance of combining both divergent and convergent methods of thinking to solve complicated problems. See if you can encourage the children in your own life to embrace both modes of thinking, to help them invent the future!

Visit Our Blog

In all our education programs , we embrace the importance of CPS and view it as a key component of the Innovation Mindset — a growth mindset infused with lessons from world-changing inventors. To stay up to date with the latest trends in STEM education, we invite you to check out our blog !

Related Articles

Introducing kids to environmental science jobs, 3 non-technical skills children need to excel – now and in the future, bring 3 nostalgic memories to life this summer.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part Two: You are the President and CEO of You

Thinking Critically and Creatively

Dr. andrew robert baker.

Critical and creative thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. They are some of the most important skills I have ever developed. I use them everyday and continue to work to improve them both.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze a myriad of issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information? It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners, and researchers. Developing my critical thinking skills over a twenty year period as a student in higher education enabled me to complete a quantitative dissertation, including analyzing research and completing statistical analysis, and earning my Ph.D. in 2014.

While critical thinking analyzes information and roots out the true nature and facets of problems, it is creative thinking that drives progress forward when it comes to solving these problems. Exceptional creative thinkers are people that invent new solutions to existing problems that do not rely on past or current solutions. They are the ones who invent solution C when everyone else is still arguing between A and B. Creative thinking skills involve using strategies to clear the mind so that our thoughts and ideas can transcend the current limitations of a problem and allow us to see beyond barriers that prevent new solutions from being found.

Brainstorming is the simplest example of intentional creative thinking that most people have tried at least once. With the quick generation of many ideas at once we can block-out our brain’s natural tendency to limit our solution-generating abilities so we can access and combine many possible solutions/thoughts and invent new ones. It is sort of like sprinting through a race’s finish line only to find there is new track on the other side and we can keep going, if we choose. As with critical thinking, higher education both demands creative thinking from us and is the perfect place to practice and develop the skill. Everything from word problems in a math class, to opinion or persuasive speeches and papers, call upon our creative thinking skills to generate new solutions and perspectives in response to our professor’s demands. Creative thinking skills ask questions such as—What if? Why not? What else is out there? Can I combine perspectives/solutions? What is something no one else has brought-up? What is being forgotten/ignored? What about ______? It is the opening of doors and options that follows problem-identification.

Consider an assignment that required you to compare two different authors on the topic of education and select and defend one as better. Now add to this scenario that your professor clearly prefers one author over the other. While critical thinking can get you as far as identifying the similarities and differences between these authors and evaluating their merits, it is creative thinking that you must use if you wish to challenge your professor’s opinion and invent new perspectives on the authors that have not previously been considered.

So, what can we do to develop our critical and creative thinking skills? Although many students may dislike it, group work is an excellent way to develop our thinking skills. Many times I have heard from students their disdain for working in groups based on scheduling, varied levels of commitment to the group or project, and personality conflicts too, of course. True—it’s not always easy, but that is why it is so effective. When we work collaboratively on a project or problem we bring many brains to bear on a subject. These different brains will naturally develop varied ways of solving or explaining problems and examining information. To the observant individual we see that this places us in a constant state of back and forth critical/creative thinking modes.

For example, in group work we are simultaneously analyzing information and generating solutions on our own, while challenging other’s analyses/ideas and responding to challenges to our own analyses/ideas. This is part of why students tend to avoid group work—it challenges us as thinkers and forces us to analyze others while defending ourselves, which is not something we are used to or comfortable with as most of our educational experiences involve solo work. Your professors know this—that’s why we assign it—to help you grow as students, learners, and thinkers!

Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom Copyright © 2015 by Thomas Priester is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Cultural Construction of Creative Problem-Solving: A Critical Reflection on Creative Design Thinking, Teaching, and Learning

- First Online: 08 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Xiao Ge 5 ,

- Chunchen Xu 6 ,

- Nanami Furue 7 ,

- Daigo Misaki 8 ,

- Cinoo Lee 6 &

- Hazel Rose Markus 6

Part of the book series: Understanding Innovation ((UNDINNO))

1153 Accesses

1 Citations

While people around the world constantly come up with ingenious ideas to solve problems, the expressions of their ingenuity and their underlying motivations and experiences may vary greatly across cultures. Currently, the role of culture is often overlooked in research and practice aimed at understanding and promoting creativity. The lack of understanding of cultural variations in creative processes hinders cross-cultural collaboration in problem-solving and innovation. We challenge the unexamined American perspectives of creativity through a systematic analysis of how ideas, policies, norms, practices, and individual tendencies around creative problem-solving are shaped in American and East Asian cultural contexts, using the culture cycle framework. We share initial findings from several pilot studies that challenge the popular view that only agentic change-makers are seen as creative problem solvers. In the context of design, designers are culturally shaped shapers who are motivated to solve problems in creative ways that resonate with their cultural values. Our research seeks to empower designers from non-Western societies. We urge design educators and practitioners to explicitly incorporate culturally varied ideas about creative problem-solving into their design processes. Our ultimate goal is to ground the theories and practices of design thinking in cultural contexts around the world.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Adams, J. L. (2019). Conceptual blockbusting: A guide to better ideas . Hachette UK.

Google Scholar

Adams, G., & Markus, H. R. (2004). Toward a conception of culture suitable for a social psychology of culture. In M. Schaller & C. S. Crandall (Eds.), The psychological foundations of culture (pp. 335–360). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Albert, R. S., & Runco, M. A. (1999). A history of research on creativity. In Handbook of creativity (pp. 16–31). Cambridge University Press.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (5), 1154–1184.

Article Google Scholar

Averill, J. R., Chon, K. K., & Hahn, D. W. (2001). Emotions and creativity, east and west. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 4 (3), 165–183.

Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation or regulatory focus? Psychological Bulletin, 134 (6), 779.

Barron, F., & Harrington, D. M. (1981). Creativity, intelligence, and personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 32 (1), 439–476.

Biao, Z. (2001). Lines and circles, west and east. English Today, 17 (3), 3–8.

Bilton, C. (2010). Manageable creativity. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 16 (3), 255–269.

Brannon, T. N., Markus, H. R., & Taylor, V. J. (2015). “Two souls, two thoughts,” two self-schemas: Double consciousness can have positive academic consequences for African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108 (4), 586–609.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation . Harper Business. (Contributor: Barry Katz)

Carleton, T., & Leifer, L. (2009). Stanford’s ME310 course as an evolution of engineering design. In Proceedings of the 19th CIRP design conference–competitive design . Cranfield University Press.

Chang, C. (1970). Creativity and Taoism: A study of Chinese philosophy, art, poetry (1st harper paperback ed.). Harper Row.

Cheryan, S., & Markus, H. R. (2020). Masculine defaults: Identifying and mitigating hidden cultural biases. Psychological Review, 127 , 1022–1052. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000209

Chesbrough, H., Kim, S., & Panisse, A. A. C. (2014). Chez Panisse: Building an open innovation ecosystem. California Management Review, 56 (4), 144–171.

Choi, J. (2010). Educating citizens in a multicultural society: The case of South Korea. The Social Studies, 101 (4), 174–178.

Chu, Y.-K. (1970). Oriental views on creativity. In A. Angoff & B. Shapiro (Eds.), Psi factors in creativity (pp. 35–50). Parapsychology Foundation.

Clancey, W. J. (2016). Creative engineering: Promoting innovation by thinking differently (introduction & W. J. Clancey, Eds.).

Csikzentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life . HarperCollins.

Dance, A. (2017). Engineering the animal out of animal products. Nature Biotechnology, 35 (8), 704–708.

Daniels, M., Cajander, A., Pears, A., & Clear, T. (2010). Engineering education research in practice: Evolving use of open ended group projects as a pedagogical strategy for developing skills in global collaboration. International Journal of Engineering Education, 26 (4), 795–806.

De Dreu, C. K., Baas, M., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). Hedonic tone and activation level in the mood-creativity link: Toward a dual pathway to creativity model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94 (5), 739–756.

Drain, A., Shekar, A., & Grigg, N. (2017). Involve me and i’ll understand’: Creative capacity building for participatory design with rural Cambodian farmers . CoDesign.

Duncker, K. (1945). On problem-solving (l. s. lees, trans.). Psychological Monographs, 58 (5), i–113.

Dym, C. L., Agogino, A. M., Eris, O., Frey, D. D., & Leifer, L. J. (2005). Engineering design thinking, teaching, and learning. Journal of Engineering Education, 94 , 103–120.

Faste, R. (1995). A visual essay on invention and innovation. Design Management Journal (Former Series), 6 (2), 9–20.

Felder, R. M., & Brent, R. (2005). Understanding student differences. Journal of Engineering Education, 94 (1), 57–72.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life . Basic Books.

Florida, R. (2007). The flight of the creative class: The new global competition for talent . HarperCollins.

Forrester, R. (2000). Empowerment: Rejuvenating a potent idea. Academy of Management Perspectives, 14 (3), 67–80.

Fruchter, R., & Townsend, A. (2003). Multi-cultural dimensions and multi-modal communication in distributed, cross-disciplinary teamwork. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19 (1), 53–61.

Ge, X., & Maisch, B. (2016). Industrial design thinking at siemens corporate technology, China. In F. B. Walter & Uebernickel (Eds.), Design thinking for innovation: Research and practice (pp. 165–181). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ge, X., Misaki, D., Furue, N., & Xu, C. (2021). Culturally responsive engineering education: Creativity through “empowered to change” in the U.S. and “admonished to preserve” in Japan. In Paper presented at 2021 ASEE virtual annual conference content access, virtual conference .

Glăveanu, V. P. (2010). Principles for a cultural psychology of creativity. Culture Psychology, 16 (2), 147–163.

Glăveanu, V. P. (2014). Revisiting the “art bias” in lay conceptions of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26 (1), 11–20.

Goldstein, D. (2017). Obama education rules are swept aside by congress. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/09/us/every-student-succeeds- act-essa-congress.html

Goncalo, J. A., & Staw, B. M. (2006). Individualism–collectivism and group creativity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100 (1), 96–109.

Grant, A. (2017). Originals: How non-conformists move the world . Penguin.

Guilford, J. (1967). The nature of human intelligence . McGraw-Hill.

Hennessey, B. A., & Amabile, T. M. (2010). Creativity. Annual Review of Psychology, 61 , 569–598.

Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33 , 83–135.

Hinds, P., & Lyon, J. (2011). Innovation and culture: Exploring the work of designers across the globe. In C. Meinel, L. Leifer, & H. Plattner (Eds.), Design thinking research (pp. 101–110). Springer.

Hippo water roller. (2022). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia . Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hippo_water_roller&oldid=1089011604

Hui, A. N., & Lau, S. (2010). Formulation of policy and strategy in developing creativity education in four Asian Chinese societies: A policy analysis. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 44 (4), 215–235.

Hui, A., & Rudowicz, E. (1997). Creative personality versus Chinese personality: How distinctive are these two personality factors? Psychologia, 40 (4), 277–285.

Hunt, M. M. (1955, May 6). The course where students lose earthly shackles. Life Magazine, 1955 , 186–202.

Hwang, K. K. (2000). Chinese relationalism: Theoretical construction and methodological considerations. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30 (2), 155–178.

Ichheiser, G. (1970). Appearances and realities (pp. 425–431). Jossey-Bass.

IDEO. (2021). Tokyo. Retrieved October 19, 2021, from https://www.ideo.com/location/tokyo

Irani, L. (2019). Chasing innovation: Making entrepreneurial citizens in modern India (Vol. 22). Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Jackson, J. C., Gelfand, M., De, S., & Fox, A. (2019). The loosening of American culture over 200 years is associated with a creativity–order trade-off. Nature Human Behaviour, 3 (3), 244–250.

Kelley, D. (2003). David Kelley’s talk documentation. Retrieved from http://www.fastefoundation.org/about/celebrationtext.php?speaker=kelley

Kelley, D. (2012). How to build your creative confidence . TED. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/davidkelleyhowtobuildyourcreativeconfidence?language=en

Kengo Kuma and Associates. (2012). Jp tower. Retrieved October 19, from https://kkaa.co.jp/works/architecture/jp-tower/

Kim, H. S., & Markus, H. R. (2002). Freedom of speech and freedom of silence: An analysis of talking as a cultural practice. In Engaging cultural differences: The multicultural challenge in liberal democracies (pp. 432–452). Springer.

Kim, H. H., Mishra, S., Hinds, P., & Liu, L. (2012). Creativity and culture: State of the art. In C. Meinel, L. Leifer, & H. Plattner (Eds.), Design thinking research (pp. 75–85). Springer.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Matsumoto, H., & Norasakkunkit, V. (1997). Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72 (6), 1245–1267.

Kuo, Y. Y. (1996). Taoistic psychology of creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 30 , 197–212.

Kusserow, A. (2012). When hard and soft clash: Class-based individualisms in Manhattan and queens. In Facing social class: How societal rank influences interaction (pp. 195–215). Springer

Lafargue, V. (2016). How to brainstorm like a Googler. Retrieved October 19, 2021, from https://www.fastcompany.com/3061059/how-to-brainstorm-like-a-googler

Langer, E. J. (2009). Counterclockwise: Mindful health and the power of possibility . Ballantine Books.

Lawson, B., & Dorst, K. (2013). Design expertise . Routledge.

Levitt, T. (2002). Creativity is not enough. Harvard Business Review, 80 , 137–144.

Lewin, K. Z. (1999). Intention, will and need. In M. Gold (Ed.), A kurt lewin reader. the complete social scientist (1st ed. 1926, pp. 83–115). American Psychological Association.

Li, P. P. (2012). Toward research-practice balancing in management: The Yin-Yang method for open-ended and open-minded research. In In west meets east: Building theoretical bridges (pp. 91–141). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Li, P. P. (2014). The unique value of yin-yang balancing: A critical response. Management and Organization Review, 10 (2), 321–332.

Lin-Siegler, X., Ahn, J. N., Chen, J., Fang, F. F. A., & Luna-Lucero, M. (2016). Even Einstein struggled: Effects of learning about great scientists’ struggles on high school students’ motivation to learn science. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108 (3), 314–328.

Liu, L. H. (1995). Translingual practice: Literature, national culture and translated modernity—China, 1900-1937 . Stanford University Press.

Liu, L., & Hinds, P. (2012). The designer identity, identity evolution, and implications on design practice. In C. Meinel, L. Leifer, & H. Plattner (Eds.), Design thinking research (pp. 185–196). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Louridas, P. (1999). Design as bricolage: Anthropology meets design thinking. Design Studies, 20 (6), 517–535.

Lubart, T. I. (1990). Creativity and cross-cultural variation. International Journal of Psychology, 25 (1), 39–59.

Lubart, T. I. (1999). Creativity across cultures. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 339–350). Cambridge University Press.

Lucena, J., Downey, G., Jesiek, B., & Elber, S. (2008). Competencies beyond countries: the re-organization of engineering education in the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Journal of Engineering Education, 97 (4), 433–447.

Mahbubani, K. (2002). Can Asians think? Understanding the divide between east and west . Steerforth Press.

Mallapaty, S. (2021). China’s five-year plan focuses on scientific self-reliance. Nature, 591 (7850), 353–354.

Markus, H. R. (2016). What moves people to action? Culture and motivation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8 , 161–166.

Markus, H. R., & Hamedani, M. G. (2019). People are culturally shaped shapers: The psychological science of culture and culture change. In Handbook of cultural psychology (2nd ed., pp. 11–52). The Guilford Press.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98 (2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

McCrae, R. R. (1987). Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (6), 1258–1265.

Misaki, D., & Ge, X. (2019). Design thinking for engineering education. Journal of the Japan Society for Precision Engineering, 85 (7), 636–639. https://doi.org/10.2493/jjspe.85.636

Misaki, D., Ge, X., & Odaka, T. (2020). Toward interdisciplinary teamwork in Japan: Developing team-based learning experience and its assessment. In Paper presented at 2020 ASEE virtual annual conference content access, virtual online.

Mistry, J., & Rogoff, B. (1985). A cultural perspective on the development of talent. In F. D. Horowitz & M. O’Brien (Eds.), The gifted and talented: Developmental perspectives (pp. 125–144). American Psychological Association.

Morris, M. W., & Leung, K. (2010). Creativity east and west: Perspectives and parallels. Management and Organization Review, 6 (3), 313–327.

Nagai, Y., & Taura, T. (2017). Critical issues of advanced design thinking: Scheme of synthesis, realm of out-frame, motive of inner sense, and resonance to future society. In D. F. Z. Moody & T. Lubart (Eds.), Creativity, design thinking and interdisciplinarity. Creativity in the twenty first century . Springer.

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108 , 291.

Nishida, K. (1960). A study of good (zen no kenkyu) . Printing Bureau, Japanese Government.

Niu, W., & Sternberg, R. (2002). Contemporary studies on the concept of creativity: The east and the west. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 36 (4), 269–288.

Niu, W., & Sternberg, R. J. (2006). The philosophical roots of western and eastern conceptions of creativity. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 26 (1–2), 18–38.

Niu, W., Zhang, J. X., & Yang, Y. (2007). Deductive reasoning and creativity: A cross-cultural study. Psychological Reports, 100 (2), 509–519.

Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization science, 5 (1), 14–37.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation . Oxford University Press.

Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and con- textual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39 (3), 607–634.

Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied imagination . Scribner.

Paletz, S. B., Peng, K., & Li, S. (2011). In the world or in the head: External and internal implicit theories of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 23 (2), 83–98.

Paletz, S. B., Bogue, K., Miron-Spektor, E., & Spencer-Rodgers, J. (2018). In J. Spencer-Rodgers & K. Peng (Eds.), Dialectical thinking and creativity from many perspectives: Contradiction and tension (pp. 267–308). Oxford University Press.

Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (1999). Culture, dialectics, and reasoning about contradiction. American Psychologist, 54 (9), 741.

Peng, K., Spencer-Rodgers, J., & Nian, Z. (2006). Naïve dialecticism and the Tao of Chinese thought. In Indigenous and cultural psychology (pp. 247–262). Springer.

Peng, A., Menold, J., & Miller, S. (2021). Crossing cultural borders: A case study of conceptual design outcomes of U.S. and Moroccan student samples. Journal of Mechanical Design, 2021 , 1–42.

Plaut, V. C., Markus, H. R., Treadway, J. R., & Fu, A. S. (2012). The cultural construction of self and well-being: A tale of two cities. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38 (12), 1644–1658.

Riquelme, H. (2002). Creative imagery in the east and west. Creativity Research Journal, 14 (2), 281–282.

Robinson, K. (2006). Do schools kill creativity? TED. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/sir_ken_robinson_do_schools_kill_creativity

Rolf A. Faste Foundation for Design Creativity. (n.d.). Zengineering. Retrieved October 19, 2021, from http://www.fastefoundation.org/about/zengineering.php

Rudowicz, E., & Hui, A. (1997). The creative personality: Hong Kong perspective. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12 (1), 139–157.

Rudowicz, E., & Yue, X. D. (2000). Concepts of creativity: Similarities and differences among mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwanese Chinese. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 34 (3), 175–192.

Rudowicz, E., & Yue, X. D. (2002). Compatibility of Chinese and creative personalities. Creativity Research Journal, 14 (3–4), 387–394.

Runco, M. A., & Bahleda, M. D. (1986). Implicit theories of artistic, scientific, and everyday creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 20 (2), 93–98.

Runco, M. A., & Johnson, D. J. (2002). Parents’ and teachers’ implicit theories of children’s creativity: A cross-cultural perspective. Creativity Research Journal, 14 (3–4), 427–438.

Saad, G., Cleveland, M., & Ho, L. (2015). Individualism–collectivism and the quantity versus quality dimensions of individual and group creative performance. Journal of Business Research, 68 (3), 578–586.

Saval, N. (2018). Kengo Kuma’s architecture of the future. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/15/t-magazine/kengo-kuma-architect.html

Seikaly, A. (2015). Weaving a home. Archello . Retrieved June 20, 2022, from https://archello.com/project/weaving-a-home

Shao, Y., Zhang, C., Zhou, J., Gu, T., & Yuan, Y. (2019). How does culture shape creativity? A mini-review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 1219.

Simonton, D. K. (2000). Creativity: Cognitive, personal, developmental, and social aspects. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 151–158.

Steinbock, D. (2013). Perfect is dead: Design lessons from the uncarved block. Retrieved from https://medium.com/i-m-h-o/perfect-is-dead-9d814a7a604e

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1995). Defying the crowd: Cultivating creativity in a culture of conformity . Free Press.

Suddaby, R., Hardy, C., & Huy, Q. N. (2011). Introduction to special topic forum: Where are the new theories of organization? Academy of Management Review, 36 (2), 236–246.

Sundararajan, L., & Raina, M. K. (2015). Revolutionary creativity, east and west: A critique from indigenous psychology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 35 (1), 3–19.

Sutton, R. I., & Hargadon, A. (1996). Brainstorming groups in context: Effectiveness in a product design firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1996 , 685–718.

Szczepański, J., & Petrowicz, L. (1978). Individuality and creativity. Dialectics and Humanism, 5 (3), 15–23.

Takeuchi, H., & Nonaka, I. (1986). The new new product development game. Harvard Business Review, 64 (1), 137–146.

Taura, T., & Nagai, Y. (2013). Perspectives on concept generation and design creativity. In Concept generation for design creativity (pp. 9–20). Springer.

Torrance, E. P. (1966). The Torrance tests of creative thinking: Norms-technical manual research edition-verbal tests, forms a and b-figural tests, forms a and b . Personnel Press.

Tzu, S. (1971). The art of war (translated by Griffith) . Oxford University Press.

Venturelli, S. (2005). Culture and the creative economy in the information age. In J. Hartley (Ed.), Creative industries (pp. 391–398). Blackwell.

Wang, Y. (2015). Heike, Jike, Chuangke: creativity in Chinese technology community (master of science dissertation) . Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Wang, Y. L., Liang, J. C., & Tsai, C. C. (2018). Cross-cultural comparisons of university students’ science learning self-efficacy: Structural relationships among factors within science learning self-efficacy. International Journal of Science Education, 40 (6), 579–594.

Webster, F. A. (1977). Entrepreneurs and ventures: An attempt at classification and clarification. Academy of Management Review, 2 (1), 54–61.

Weiner, R. (2000). Creativity and beyond: Cultures, values, and change . SUNY Press.

Weisberg, R. W., & Markman, A. (2009). On “out-of-the-box” thinking in creativity. In Tools for innovation (pp. 23–47).

Wight, C. (1998). Review essay: Philosophical geographies navigating philosophy in social science. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, 28 (4), 552–566.

Xinhua. (2021). Outline of the People’s Republic of China 14th five-year plan for national economic and social development and long-range objectives for 2035. Retrieved October 19, 2021, from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content5592681.htm

Yan, L. (2015). Intelligence of life—The modern explanation of Chinese traditional views of intelligence . XinXueTang (Chinese).

Yokoi, G. (2021). Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia . Retrieved October 19, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunpei

Yuasa, Y. (1987). The body: Toward an eastern mind-body theory, T. P. Kasulis, (ed.), translated by S. Nagatomi and T. P. Kasulis . State University of New York Press.

Yukawa, H. (1973). Creativity and intuition (trans. J. Bester) . Kodansha International..

Zha, P., Walczyk, J. J., Griffith-Ross, D. A., Tobacyk, J. J., & Walczyk, D. F. (2006). The impact of culture and individualism–collectivism on the creative potential and achievement of American and Chinese adults. Creativity Research Journal, 18 (3), 355–366.

Zhang, D. L., & Chen, Z. Y. (1991). Zhongguo Siwei Pianxiang (the orientation of Chinese thinking) . Social Science Press. (In Chinese).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Design Research, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Stanford SPARQ, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Chunchen Xu, Cinoo Lee & Hazel Rose Markus

School of Management, Tokyo University of Science, Tokyo, Japan

Nanami Furue

Faculty of Engineering, Kogakuin University, Tokyo, Japan

Daigo Misaki

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Xiao Ge .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Hasso Plattner Institute and Digital Engineering Faculty, University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany

Christoph Meinel

Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA

Larry Leifer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ge, X., Xu, C., Furue, N., Misaki, D., Lee, C., Markus, H.R. (2022). The Cultural Construction of Creative Problem-Solving: A Critical Reflection on Creative Design Thinking, Teaching, and Learning. In: Meinel, C., Leifer, L. (eds) Design Thinking Research . Understanding Innovation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09297-8_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-09297-8_15

Published : 08 September 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-09296-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-09297-8

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

COMMENTS

Creative problem-solving primarily operates in the ideate phase of design thinking but can be applied to others. This is because design thinking is an iterative process that moves between the stages as ideas are generated and pursued. This is normal and encouraged, as innovation requires exploring multiple ideas.

Key Points. Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using your creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems. The process is based on separating divergent and convergent thinking styles, so that you can focus your mind on creating at the first stage, and then evaluating at the second stage.

A Cognitive Trick for Solving Problems Creatively. by. Theodore Scaltsas. May 04, 2016. Save. Many experts argue that creative thinking requires people to challenge their preconceptions and ...

Also known as creative problem-solving, creative thinking is a valuable and marketable soft skill in a wide variety of careers. Here's what you need to know about creative thinking at work and how to use it to land a job. Creative Thinking Definition. Creative thinking is all about developing innovative solutions to problems.

Creative problem-solving is an essential skill that goes beyond basic brainstorming. It entails a holistic approach to challenges, melding logical processes with imaginative techniques to conceive innovative solutions. As our world becomes increasingly complex and interconnected, the ability to think creatively and solve problems with fresh ...

Creative problem-solving is a type of problem-solving. It involves searching for new and novel solutions to problems. Unlike critical thinking, which scrutinizes assumptions and uses reasoning, creative thinking is about generating alternative ideas—practices and solutions that are unique and effective. It's about facing sometimes muddy and ...

CPS is a comprehensive system built on our own natural thinking processes that deliberately ignites creative thinking and produces innovative solutions. Through alternating phases of divergent and convergent thinking, CPS provides a process for managing thinking and action, while avoiding premature or inappropriate judgment. It is built upon a ...

Humans are innate creative problem-solvers. Since early humans developed the first stone tools to crack open fruit and nuts more than 2 million years ago, the application of creative thinking to solve problems has been a distinct competitive advantage for our species (Puccio 2017).Originally used to solve problems related to survival, the tendency toward the use of creative problem-solving to ...

Creative problem-solving (CPS) is the mental process of searching for an original and previously unknown solution to a problem. To qualify, the solution must be novel and reached independently. The creative problem-solving process was originally developed by Alex Osborn and Sid Parnes.Creative problem solving (CPS) is a way of using creativity to develop new ideas and solutions to problems.

Solving Problems with Creative and Critical Thinking. Module 1 • 3 hours to complete. This module will help you to develop skills and behaviors required to solve problems and implement solutions more efficiently in an agile manner by using a systematic five-step process that involves both creative and critical thinking.

The creative problem-solving process Footnote 1 is a systematic approach to problem-solving that was first proposed by Alex Osborn in 1953 in his landmark book Applied Imagination.The approach went through several refinements over a period of five years. Osborn began with a seven-step model that reflected the creative process (orientation, preparation, analysis, hypothesis, incubation ...

Summary. This chapter examines the phenomenon of insightin problem-solving, a challenge to the analytic-thinking view concerning creativity. "Insight" refers to the idea that creative ideas come about suddenly, as the result of far-ranging creative leaps, in which thinking breaks away from what we know and moves far into the unknown.

The National Inventors Hall of Fame® explains the proven method of Creative Problem Solving ... divergent thinking involves solving a problem using methods that deviate from commonly used or existing strategies. In this case, an individual creates many different answers using the information available to them. ... Related Articles. Trends in STEM.

This structured thinking method originated in the Arthur D. Little Invention Design Unit in the 1950s. It is a comprehensive creative problem-solving process, which addresses all stages of the creative process and emphasizes differentiation between idea generation and idea evaluation.

Here are 8 creative problem-solving strategies you could try to bring creativity and fresh ideas to bear on any problem you might have. 1. Counterfactual Thinking. Counterfactual thinking involves considering what would have happened if the events in the past had happened slightly differently. In essence, it is asking 'what if' questions ...

The purpose of this chapter is to describe what we mean by "creative approaches to prob - lem solving." As a result of reading this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. Describe the four basic elements of the system for understanding creativity. 2. Explain what the terms creativity, problem solving, and creative problem solving

Critical and creative thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. They are some of the most important skills I have ever developed. I use them everyday and continue to work to improve them both. The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or ...

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT. Cognitive psychologists consider creativity a special kind of problem-solving experience. This experience often involves the rational and conscious convergent thinking, the irrational and unconscious divergent thinking, and the insight, that is, a sudden, visionary moment of realisation, in which the solver envisages the solution, often surprisingly and unexpectedly ...

1 Synergy Effect. Creative thinking can often serve as a catalyst for logical analysis, creating a synergy that enhances problem-solving capabilities. Think of it as a dance between two partners ...

3 The Process. The process of integrating creative thinking into logical analysis can be thought of as a cycle. It begins with an open-minded exploration of the problem space, where you brainstorm ...

The principle of neuropsychological correlates in mathematical creativity highlights the brain's role in creative problem-solving. Understanding the neural mechanisms that underlie creative ...

4 Mental Flexibility. Mental flexibility is a cornerstone of creative problem-solving. By regularly practicing creative exercises, such as puzzles that require lateral thinking or tasks that ...