- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

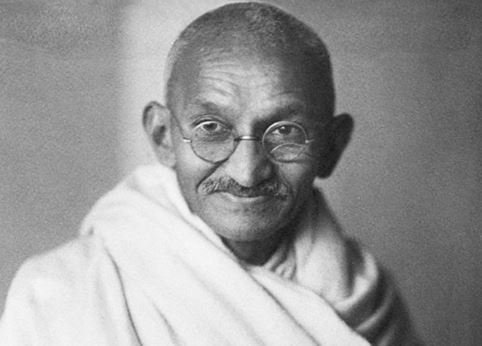

Mahatma Gandhi

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: July 30, 2010

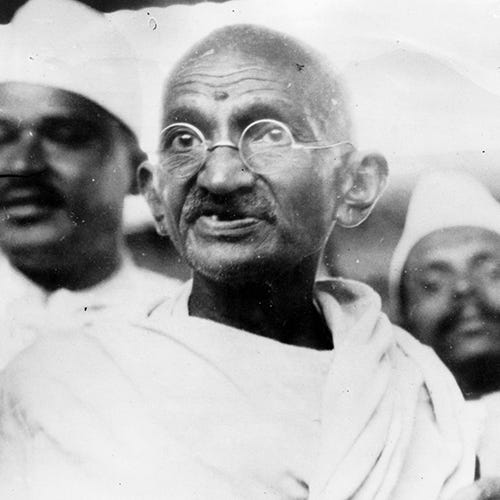

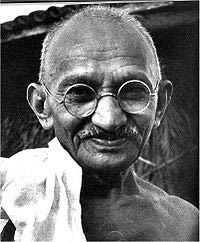

Revered the world over for his nonviolent philosophy of passive resistance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was known to his many followers as Mahatma, or “the great-souled one.” He began his activism as an Indian immigrant in South Africa in the early 1900s, and in the years following World War I became the leading figure in India’s struggle to gain independence from Great Britain. Known for his ascetic lifestyle–he often dressed only in a loincloth and shawl–and devout Hindu faith, Gandhi was imprisoned several times during his pursuit of non-cooperation, and undertook a number of hunger strikes to protest the oppression of India’s poorest classes, among other injustices. After Partition in 1947, he continued to work toward peace between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi was shot to death in Delhi in January 1948 by a Hindu fundamentalist.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, at Porbandar, in the present-day Indian state of Gujarat. His father was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar; his deeply religious mother was a devoted practitioner of Vaishnavism (worship of the Hindu god Vishnu), influenced by Jainism, an ascetic religion governed by tenets of self-discipline and nonviolence. At the age of 19, Mohandas left home to study law in London at the Inner Temple, one of the city’s four law colleges. Upon returning to India in mid-1891, he set up a law practice in Bombay, but met with little success. He soon accepted a position with an Indian firm that sent him to its office in South Africa. Along with his wife, Kasturbai, and their children, Gandhi remained in South Africa for nearly 20 years.

Did you know? In the famous Salt March of April-May 1930, thousands of Indians followed Gandhi from Ahmadabad to the Arabian Sea. The march resulted in the arrest of nearly 60,000 people, including Gandhi himself.

Gandhi was appalled by the discrimination he experienced as an Indian immigrant in South Africa. When a European magistrate in Durban asked him to take off his turban, he refused and left the courtroom. On a train voyage to Pretoria, he was thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and beaten up by a white stagecoach driver after refusing to give up his seat for a European passenger. That train journey served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he soon began developing and teaching the concept of satyagraha (“truth and firmness”), or passive resistance, as a way of non-cooperation with authorities.

The Birth of Passive Resistance

In 1906, after the Transvaal government passed an ordinance regarding the registration of its Indian population, Gandhi led a campaign of civil disobedience that would last for the next eight years. During its final phase in 1913, hundreds of Indians living in South Africa, including women, went to jail, and thousands of striking Indian miners were imprisoned, flogged and even shot. Finally, under pressure from the British and Indian governments, the government of South Africa accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts, which included important concessions such as the recognition of Indian marriages and the abolition of the existing poll tax for Indians.

In July 1914, Gandhi left South Africa to return to India. He supported the British war effort in World War I but remained critical of colonial authorities for measures he felt were unjust. In 1919, Gandhi launched an organized campaign of passive resistance in response to Parliament’s passage of the Rowlatt Acts, which gave colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress subversive activities. He backed off after violence broke out–including the massacre by British-led soldiers of some 400 Indians attending a meeting at Amritsar–but only temporarily, and by 1920 he was the most visible figure in the movement for Indian independence.

Leader of a Movement

As part of his nonviolent non-cooperation campaign for home rule, Gandhi stressed the importance of economic independence for India. He particularly advocated the manufacture of khaddar, or homespun cloth, in order to replace imported textiles from Britain. Gandhi’s eloquence and embrace of an ascetic lifestyle based on prayer, fasting and meditation earned him the reverence of his followers, who called him Mahatma (Sanskrit for “the great-souled one”). Invested with all the authority of the Indian National Congress (INC or Congress Party), Gandhi turned the independence movement into a massive organization, leading boycotts of British manufacturers and institutions representing British influence in India, including legislatures and schools.

After sporadic violence broke out, Gandhi announced the end of the resistance movement, to the dismay of his followers. British authorities arrested Gandhi in March 1922 and tried him for sedition; he was sentenced to six years in prison but was released in 1924 after undergoing an operation for appendicitis. He refrained from active participation in politics for the next several years, but in 1930 launched a new civil disobedience campaign against the colonial government’s tax on salt, which greatly affected Indian’s poorest citizens.

A Divided Movement

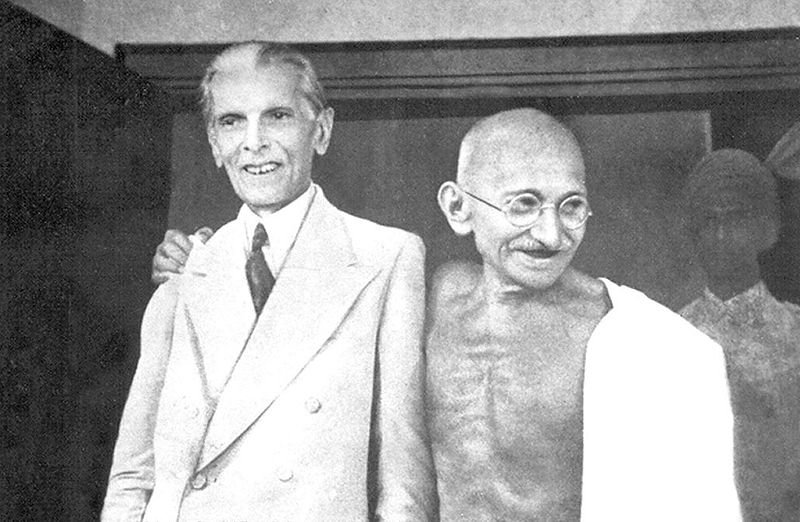

In 1931, after British authorities made some concessions, Gandhi again called off the resistance movement and agreed to represent the Congress Party at the Round Table Conference in London. Meanwhile, some of his party colleagues–particularly Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a leading voice for India’s Muslim minority–grew frustrated with Gandhi’s methods, and what they saw as a lack of concrete gains. Arrested upon his return by a newly aggressive colonial government, Gandhi began a series of hunger strikes in protest of the treatment of India’s so-called “untouchables” (the poorer classes), whom he renamed Harijans, or “children of God.” The fasting caused an uproar among his followers and resulted in swift reforms by the Hindu community and the government.

In 1934, Gandhi announced his retirement from politics in, as well as his resignation from the Congress Party, in order to concentrate his efforts on working within rural communities. Drawn back into the political fray by the outbreak of World War II , Gandhi again took control of the INC, demanding a British withdrawal from India in return for Indian cooperation with the war effort. Instead, British forces imprisoned the entire Congress leadership, bringing Anglo-Indian relations to a new low point.

Partition and Death of Gandhi

After the Labor Party took power in Britain in 1947, negotiations over Indian home rule began between the British, the Congress Party and the Muslim League (now led by Jinnah). Later that year, Britain granted India its independence but split the country into two dominions: India and Pakistan. Gandhi strongly opposed Partition, but he agreed to it in hopes that after independence Hindus and Muslims could achieve peace internally. Amid the massive riots that followed Partition, Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together, and undertook a hunger strike until riots in Calcutta ceased.

In January 1948, Gandhi carried out yet another fast, this time to bring about peace in the city of Delhi. On January 30, 12 days after that fast ended, Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting in Delhi when he was shot to death by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic enraged by Mahatma’s efforts to negotiate with Jinnah and other Muslims. The next day, roughly 1 million people followed the procession as Gandhi’s body was carried in state through the streets of the city and cremated on the banks of the holy Jumna River.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

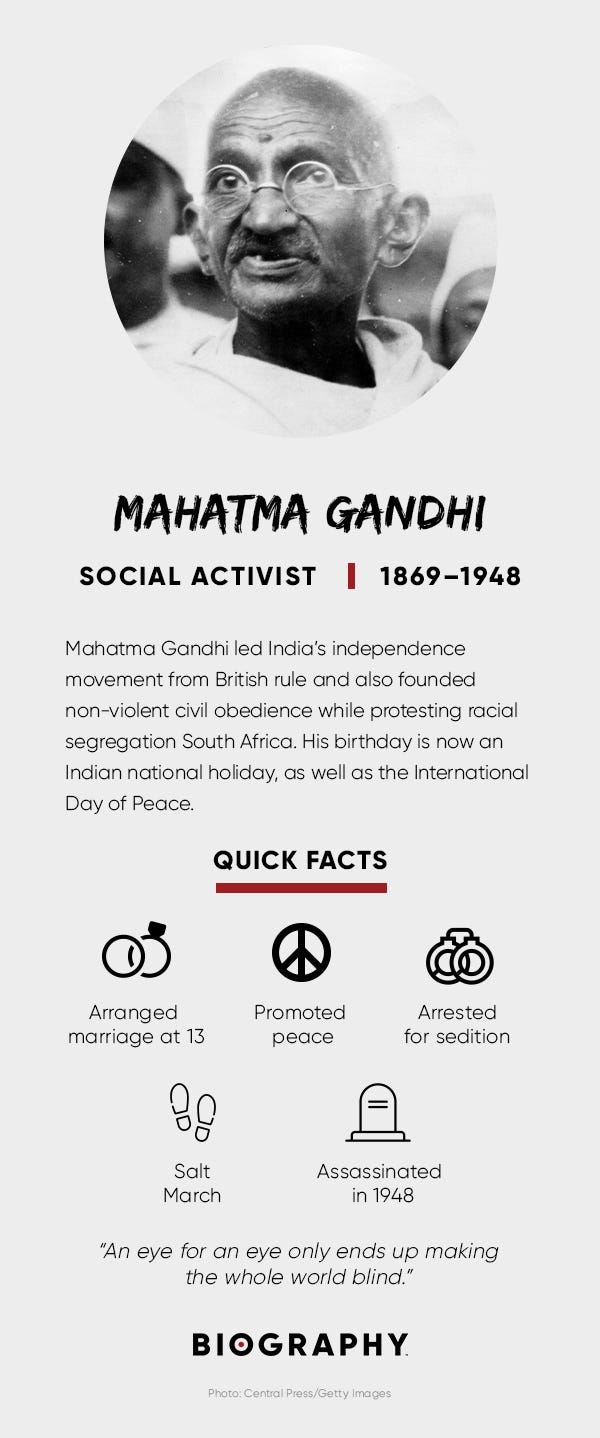

Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. He was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse.

(1869-1948)

Who Was Mahatma Gandhi?

Mahatma Gandhi was the leader of India’s non-violent independence movement against British rule and in South Africa who advocated for the civil rights of Indians. Born in Porbandar, India, Gandhi studied law and organized boycotts against British institutions in peaceful forms of civil disobedience. He was killed by a fanatic in 1948.

Early Life and Education

Indian nationalist leader Gandhi (born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi) was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Kathiawar, India, which was then part of the British Empire.

Gandhi’s father, Karamchand Gandhi, served as a chief minister in Porbandar and other states in western India. His mother, Putlibai, was a deeply religious woman who fasted regularly.

Young Gandhi was a shy, unremarkable student who was so timid that he slept with the lights on even as a teenager. In the ensuing years, the teenager rebelled by smoking, eating meat and stealing change from household servants.

Although Gandhi was interested in becoming a doctor, his father hoped he would also become a government minister and steered him to enter the legal profession. In 1888, 18-year-old Gandhi sailed for London, England, to study law. The young Indian struggled with the transition to Western culture.

Upon returning to India in 1891, Gandhi learned that his mother had died just weeks earlier. He struggled to gain his footing as a lawyer. In his first courtroom case, a nervous Gandhi blanked when the time came to cross-examine a witness. He immediately fled the courtroom after reimbursing his client for his legal fees.

Gandhi’s Religion and Beliefs

Gandhi grew up worshiping the Hindu god Vishnu and following Jainism, a morally rigorous ancient Indian religion that espoused non-violence, fasting, meditation and vegetarianism.

During Gandhi’s first stay in London, from 1888 to 1891, he became more committed to a meatless diet, joining the executive committee of the London Vegetarian Society, and started to read a variety of sacred texts to learn more about world religions.

Living in South Africa, Gandhi continued to study world religions. “The religious spirit within me became a living force,” he wrote of his time there. He immersed himself in sacred Hindu spiritual texts and adopted a life of simplicity, austerity, fasting and celibacy that was free of material goods.

Gandhi in South Africa

After struggling to find work as a lawyer in India, Gandhi obtained a one-year contract to perform legal services in South Africa. In April 1893, he sailed for Durban in the South African state of Natal.

When Gandhi arrived in South Africa, he was quickly appalled by the discrimination and racial segregation faced by Indian immigrants at the hands of white British and Boer authorities. Upon his first appearance in a Durban courtroom, Gandhi was asked to remove his turban. He refused and left the court instead. The Natal Advertiser mocked him in print as “an unwelcome visitor.”

Nonviolent Civil Disobedience

A seminal moment occurred on June 7, 1893, during a train trip to Pretoria, South Africa, when a white man objected to Gandhi’s presence in the first-class railway compartment, although he had a ticket. Refusing to move to the back of the train, Gandhi was forcibly removed and thrown off the train at a station in Pietermaritzburg.

Gandhi’s act of civil disobedience awoke in him a determination to devote himself to fighting the “deep disease of color prejudice.” He vowed that night to “try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.”

From that night forward, the small, unassuming man would grow into a giant force for civil rights. Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

Gandhi prepared to return to India at the end of his year-long contract until he learned, at his farewell party, of a bill before the Natal Legislative Assembly that would deprive Indians of the right to vote. Fellow immigrants convinced Gandhi to stay and lead the fight against the legislation. Although Gandhi could not prevent the law’s passage, he drew international attention to the injustice.

After a brief trip to India in late 1896 and early 1897, Gandhi returned to South Africa with his wife and children. Gandhi ran a thriving legal practice, and at the outbreak of the Boer War, he raised an all-Indian ambulance corps of 1,100 volunteers to support the British cause, arguing that if Indians expected to have full rights of citizenship in the British Empire, they also needed to shoulder their responsibilities.

In 1906, Gandhi organized his first mass civil-disobedience campaign, which he called “Satyagraha” (“truth and firmness”), in reaction to the South African Transvaal government’s new restrictions on the rights of Indians, including the refusal to recognize Hindu marriages.

After years of protests, the government imprisoned hundreds of Indians in 1913, including Gandhi. Under pressure, the South African government accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts that included recognition of Hindu marriages and the abolition of a poll tax for Indians.

Return to India

In 1915 Gandhi founded an ashram in Ahmedabad, India, that was open to all castes. Wearing a simple loincloth and shawl, Gandhi lived an austere life devoted to prayer, fasting and meditation. He became known as “Mahatma,” which means “great soul.”

Opposition to British Rule in India

In 1919, with India still under the firm control of the British, Gandhi had a political reawakening when the newly enacted Rowlatt Act authorized British authorities to imprison people suspected of sedition without trial. In response, Gandhi called for a Satyagraha campaign of peaceful protests and strikes.

Violence broke out instead, which culminated on April 13, 1919, in the Massacre of Amritsar. Troops led by British Brigadier General Reginald Dyer fired machine guns into a crowd of unarmed demonstrators and killed nearly 400 people.

No longer able to pledge allegiance to the British government, Gandhi returned the medals he earned for his military service in South Africa and opposed Britain’s mandatory military draft of Indians to serve in World War I.

Gandhi became a leading figure in the Indian home-rule movement. Calling for mass boycotts, he urged government officials to stop working for the Crown, students to stop attending government schools, soldiers to leave their posts and citizens to stop paying taxes and purchasing British goods.

Rather than buy British-manufactured clothes, he began to use a portable spinning wheel to produce his own cloth. The spinning wheel soon became a symbol of Indian independence and self-reliance.

Gandhi assumed the leadership of the Indian National Congress and advocated a policy of non-violence and non-cooperation to achieve home rule.

After British authorities arrested Gandhi in 1922, he pleaded guilty to three counts of sedition. Although sentenced to a six-year imprisonment, Gandhi was released in February 1924 after appendicitis surgery.

He discovered upon his release that relations between India’s Hindus and Muslims devolved during his time in jail. When violence between the two religious groups flared again, Gandhi began a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924 to urge unity. He remained away from active politics during much of the latter 1920s.

Gandhi and the Salt March

Gandhi returned to active politics in 1930 to protest Britain’s Salt Acts, which not only prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt—a dietary staple—but imposed a heavy tax that hit the country’s poorest particularly hard. Gandhi planned a new Satyagraha campaign, The Salt March , that entailed a 390-kilometer/240-mile march to the Arabian Sea, where he would collect salt in symbolic defiance of the government monopoly.

“My ambition is no less than to convert the British people through non-violence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India,” he wrote days before the march to the British viceroy, Lord Irwin.

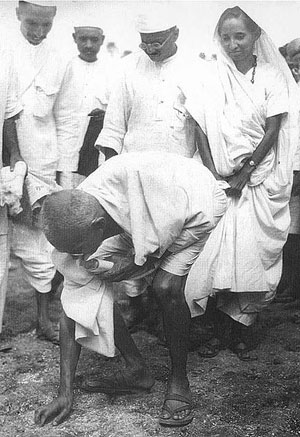

Wearing a homespun white shawl and sandals and carrying a walking stick, Gandhi set out from his religious retreat in Sabarmati on March 12, 1930, with a few dozen followers. By the time he arrived 24 days later in the coastal town of Dandi, the ranks of the marchers swelled, and Gandhi broke the law by making salt from evaporated seawater.

The Salt March sparked similar protests, and mass civil disobedience swept across India. Approximately 60,000 Indians were jailed for breaking the Salt Acts, including Gandhi, who was imprisoned in May 1930.

Still, the protests against the Salt Acts elevated Gandhi into a transcendent figure around the world. He was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” for 1930.

Gandhi was released from prison in January 1931, and two months later he made an agreement with Lord Irwin to end the Salt Satyagraha in exchange for concessions that included the release of thousands of political prisoners. The agreement, however, largely kept the Salt Acts intact. But it did give those who lived on the coasts the right to harvest salt from the sea.

Hoping that the agreement would be a stepping-stone to home rule, Gandhi attended the London Round Table Conference on Indian constitutional reform in August 1931 as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference, however, proved fruitless.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MAHATMA GANDHI FACT CARD

Protesting "Untouchables" Segregation

Gandhi returned to India to find himself imprisoned once again in January 1932 during a crackdown by India’s new viceroy, Lord Willingdon. He embarked on a six-day fast to protest the British decision to segregate the “untouchables,” those on the lowest rung of India’s caste system, by allotting them separate electorates. The public outcry forced the British to amend the proposal.

After his eventual release, Gandhi left the Indian National Congress in 1934, and leadership passed to his protégé Jawaharlal Nehru . He again stepped away from politics to focus on education, poverty and the problems afflicting India’s rural areas.

India’s Independence from Great Britain

As Great Britain found itself engulfed in World War II in 1942, Gandhi launched the “Quit India” movement that called for the immediate British withdrawal from the country. In August 1942, the British arrested Gandhi, his wife and other leaders of the Indian National Congress and detained them in the Aga Khan Palace in present-day Pune.

“I have not become the King’s First Minister in order to preside at the liquidation of the British Empire,” Prime Minister Winston Churchill told Parliament in support of the crackdown.

With his health failing, Gandhi was released after a 19-month detainment in 1944.

After the Labour Party defeated Churchill’s Conservatives in the British general election of 1945, it began negotiations for Indian independence with the Indian National Congress and Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s Muslim League. Gandhi played an active role in the negotiations, but he could not prevail in his hope for a unified India. Instead, the final plan called for the partition of the subcontinent along religious lines into two independent states—predominantly Hindu India and predominantly Muslim Pakistan.

Violence between Hindus and Muslims flared even before independence took effect on August 15, 1947. Afterwards, the killings multiplied. Gandhi toured riot-torn areas in an appeal for peace and fasted in an attempt to end the bloodshed. Some Hindus, however, increasingly viewed Gandhi as a traitor for expressing sympathy toward Muslims.

Gandhi’s Wife and Kids

At the age of 13, Gandhi wed Kasturba Makanji, a merchant’s daughter, in an arranged marriage. She died in Gandhi’s arms in February 1944 at the age of 74.

In 1885, Gandhi endured the passing of his father and shortly after that the death of his young baby.

In 1888, Gandhi’s wife gave birth to the first of four surviving sons. A second son was born in India 1893. Kasturba gave birth to two more sons while living in South Africa, one in 1897 and one in 1900.

Assassination of Mahatma Gandhi

On January 30, 1948, 78-year-old Gandhi was shot and killed by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

Weakened from repeated hunger strikes, Gandhi clung to his two grandnieces as they led him from his living quarters in New Delhi’s Birla House to a late-afternoon prayer meeting. Godse knelt before the Mahatma before pulling out a semiautomatic pistol and shooting him three times at point-blank range. The violent act took the life of a pacifist who spent his life preaching nonviolence.

Godse and a co-conspirator were executed by hanging in November 1949. Additional conspirators were sentenced to life in prison.

Even after Gandhi’s assassination, his commitment to nonviolence and his belief in simple living — making his own clothes, eating a vegetarian diet and using fasts for self-purification as well as a means of protest — have been a beacon of hope for oppressed and marginalized people throughout the world.

Satyagraha remains one of the most potent philosophies in freedom struggles throughout the world today. Gandhi’s actions inspired future human rights movements around the globe, including those of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States and Nelson Mandela in South Africa.

Martin Luther King

"],["

Winston Churchill

Nelson Mandela

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Mahatma Gandhi

- Birth Year: 1869

- Birth date: October 2, 1869

- Birth City: Porbandar, Kathiawar

- Birth Country: India

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Mahatma Gandhi was the primary leader of India’s independence movement and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would influence the world. Until Gandhi was assassinated in 1948, his life and teachings inspired activists including Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Civil Rights

- Astrological Sign: Libra

- University College London

- Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- As a young man, Mahatma Gandhi was a poor student and was terrified of public speaking.

- Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Congress in 1894 to fight discrimination.

- Gandhi was assassinated by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, who was upset at Gandhi’s tolerance of Muslims.

- Gandhi's non-violent civil disobedience inspired future world leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela.

- Death Year: 1948

- Death date: January 30, 1948

- Death City: New Delhi

- Death Country: India

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Mahatma Gandhi Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/mahatma-gandhi

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 4, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.

- Victory attained by violence is tantamount to a defeat, for it is momentary.

- Religions are different roads converging to the same point. What does it matter that we take different roads, so long as we reach the same goal? In reality, there are as many religions as there are individuals.

- The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.

- To call woman the weaker sex is a libel; it is man's injustice to woman.

- Truth alone will endure, all the rest will be swept away before the tide of time.

- A man is but the product of his thoughts. What he thinks, he becomes.

- There are many things to do. Let each one of us choose our task and stick to it through thick and thin. Let us not think of the vastness. But let us pick up that portion which we can handle best.

- An error does not become truth by reason of multiplied propagation, nor does truth become error because nobody sees it.

- For one man cannot do right in one department of life whilst he is occupied in doing wrong in any other department. Life is one indivisible whole.

- If we are to reach real peace in this world and if we are to carry on a real war against war, we shall have to begin with children.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Assassinations

The Manhunt for John Wilkes Booth

Indira Gandhi

Alexei Navalny

Martin Luther King Jr.

James Earl Ray

Malala Yousafzai

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

Lee Harvey Oswald

John F. Kennedy

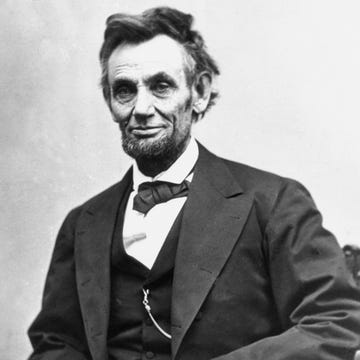

Abraham Lincoln

Biography Online

Mahatma Gandhi Biography

Mahatma Gandhi was a prominent Indian political leader who was a leading figure in the campaign for Indian independence. He employed non-violent principles and peaceful disobedience as a means to achieve his goal. He was assassinated in 1948, shortly after achieving his life goal of Indian independence. In India, he is known as ‘Father of the Nation’.

“When I despair, I remember that all through history the ways of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants, and murderers, and for a time they can seem invincible, but in the end they always fall. Think of it–always.”

Short Biography of Mahatma Gandhi

Around this time, he also studied the Bible and was struck by the teachings of Jesus Christ – especially the emphasis on humility and forgiveness. He remained committed to the Bible and Bhagavad Gita throughout his life, though he was critical of aspects of both religions.

Gandhi in South Africa

On completing his degree in Law, Gandhi returned to India, where he was soon sent to South Africa to practise law. In South Africa, Gandhi was struck by the level of racial discrimination and injustice often experienced by Indians. In 1893, he was thrown off a train at the railway station in Pietermaritzburg after a white man complained about Gandhi travelling in first class. This experience was a pivotal moment for Gandhi and he began to represent other Indias who experienced discrimination. As a lawyer he was in high demand and soon he became the unofficial leader for Indians in South Africa. It was in South Africa that Gandhi first experimented with campaigns of civil disobedience and protest; he called his non-violent protests satyagraha . Despite being imprisoned for short periods of time, he also supported the British under certain conditions. During the Boer war, he served as a medic and stretcher-bearer. He felt that by doing his patriotic duty it would make the government more amenable to demands for fair treatment. Gandhi was at the Battle of Spion serving as a medic. An interesting historical anecdote, is that at this battle was also Winston Churchill and Louis Botha (future head of South Africa) He was decorated by the British for his efforts during the Boer War and Zulu rebellion.

Gandhi and Indian Independence

After 21 years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India in 1915. He became the leader of the Indian nationalist movement campaigning for home rule or Swaraj .

Gandhi also encouraged his followers to practise inner discipline to get ready for independence. Gandhi said the Indians had to prove they were deserving of independence. This is in contrast to independence leaders such as Aurobindo Ghose , who argued that Indian independence was not about whether India would offer better or worse government, but that it was the right for India to have self-government.

Gandhi also clashed with others in the Indian independence movement such as Subhas Chandra Bose who advocated direct action to overthrow the British.

Gandhi frequently called off strikes and non-violent protest if he heard people were rioting or violence was involved.

In 1930, Gandhi led a famous march to the sea in protest at the new Salt Acts. In the sea, they made their own salt, in violation of British regulations. Many hundreds were arrested and Indian jails were full of Indian independence followers.

“With this I’m shaking the foundations of the British Empire.”

– Gandhi – after holding up a cup of salt at the end of the salt march.

However, whilst the campaign was at its peak some Indian protesters killed some British civilians, and as a result, Gandhi called off the independence movement saying that India was not ready. This broke the heart of many Indians committed to independence. It led to radicals like Bhagat Singh carrying on the campaign for independence, which was particularly strong in Bengal.

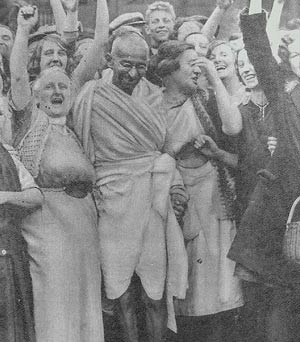

In 1931, Gandhi was invited to London to begin talks with the British government on greater self-government for India, but remaining a British colony. During his three month stay, he declined the government’s offer of a free hotel room, preferring to stay with the poor in the East End of London. During the talks, Gandhi opposed the British suggestions of dividing India along communal lines as he felt this would divide a nation which was ethnically mixed. However, at the summit, the British also invited other leaders of India, such as BR Ambedkar and representatives of the Sikhs and Muslims. Although the dominant personality of Indian independence, he could not always speak for the entire nation.

Gandhi’s humour and wit

During this trip, he visited King George in Buckingham Palace, one apocryphal story which illustrates Gandhi’s wit was the question by the king – what do you think of Western civilisation? To which Gandhi replied

“It would be a good idea.”

Gandhi wore a traditional Indian dress, even whilst visiting the king. It led Winston Churchill to make the disparaging remark about the half naked fakir. When Gandhi was asked if was sufficiently dressed to meet the king, Gandhi replied

“The king was wearing clothes enough for both of us.”

Gandhi once said he if did not have a sense of humour he would have committed suicide along time ago.

Gandhi and the Partition of India

After the war, Britain indicated that they would give India independence. However, with the support of the Muslims led by Jinnah, the British planned to partition India into two: India and Pakistan. Ideologically Gandhi was opposed to partition. He worked vigorously to show that Muslims and Hindus could live together peacefully. At his prayer meetings, Muslim prayers were read out alongside Hindu and Christian prayers. However, Gandhi agreed to the partition and spent the day of Independence in prayer mourning the partition. Even Gandhi’s fasts and appeals were insufficient to prevent the wave of sectarian violence and killing that followed the partition.

Away from the politics of Indian independence, Gandhi was harshly critical of the Hindu Caste system. In particular, he inveighed against the ‘untouchable’ caste, who were treated abysmally by society. He launched many campaigns to change the status of untouchables. Although his campaigns were met with much resistance, they did go a long way to changing century-old prejudices.

At the age of 78, Gandhi undertook another fast to try and prevent the sectarian killing. After 5 days, the leaders agreed to stop killing. But ten days later Gandhi was shot dead by a Hindu Brahmin opposed to Gandhi’s support for Muslims and the untouchables.

Gandhi and Religion

Gandhi was a seeker of the truth.

“In the attitude of silence the soul finds the path in a clearer light, and what is elusive and deceptive resolves itself into crystal clearness. Our life is a long and arduous quest after Truth.”

Gandhi said his great aim in life was to have a vision of God. He sought to worship God and promote religious understanding. He sought inspiration from many different religions: Jainism, Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and incorporated them into his own philosophy.

On several occasions, he used religious practices and fasting as part of his political approach. Gandhi felt that personal example could influence public opinion.

“When every hope is gone, ‘when helpers fail and comforts flee,’ I find that help arrives somehow, from I know not where. Supplication, worship, prayer are no superstition; they are acts more real than the acts of eating, drinking, sitting or walking. It is no exaggeration to say that they alone are real, all else is unreal.”

– Gandhi Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments with Truth

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Mahatma Gandhi” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net 12th Jan 2011. Last updated 1 Feb 2020.

The Essential Gandhi

The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas at Amazon

Gandhi: An Autobiography – The Story of My Experiments With Truth at Amazon

Related pages

Indian men and women involved in the Independence Movement.

- Nehru Biography

He stood out in his time in history. Non violence as he practised it was part of his spiritual learning usedvas a political tool. How can one say he wasn’t a good lawyer or he wasn’t a good leader when he had such a following and he was part of the negotiations thar brought about Indian Independance? I just dipped into this ti find out about the salt march.:)

- February 09, 2019 9:31 AM

- By Lakmali Gunawardena

mahatma gandhi was a good person but he wasn’t all good because when he freed the indian empire the partition grew between the muslims and they fought .this didn’t happen much when the british empire was in control because muslims and hindus had a common enemy to unite against.

I am not saying the british empire was a good thing.

- January 01, 2019 3:24 PM

- By marcus carpenter

Dear very nice information Gandhi ji always inspired us thanks a lot.

- October 01, 2018 1:40 PM

FATHER OF NATION

- June 03, 2018 8:34 AM

Gandhi was a lawyer who did not make a good impression as a lawyer. His success and influence was mediocre in law religion and politics. He rose to prominence by chance. He was neither a good lawyer or a leader circumstances conspired at a time in history for him to stand out as an astute leader both in South Africa and in India. The British were unable to control the tidal wave of independence in all the countries they ruled at that time. Gandhi was astute enough to seize the opportunity and used non violence as a tool which had no teeth but caused sufficient concern for the British to negotiate and hand over territories which they had milked dry.

- February 09, 2018 2:30 PM

- By A S Cassim

By being “astute enough to seize the opportunity” and not being pushed down/ defeated by an Empire, would you agree this is actually the reason why Gandhi made a good impression as a leader? Also, despite his mediocre success and influence as you mentioned, would you agree the outcome of his accomplishments are clearly a demonstration he actually was relevant to law, religion and politics?

- November 23, 2018 12:45 AM

Biography of Mohandas Gandhi, Indian Independence Leader

Apic /Getty Images

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

South Africa

Return to india, back to india, confronting british.

- Indian Independence

Assassination

- Conflic Between Hindus and Muslims

- B.A., History, University of California at Davis

Mohandas Gandhi (October 2, 1869–January 30, 1948) was the father of the Indian independence movement. While fighting discrimination in South Africa, Gandhi developed satyagrah a, a nonviolent way of protesting injustice. Returning to his birthplace of India, Gandhi spent his remaining years working to end British rule of his country and to better the lives of India's poorest classes.

Fast Facts: Mohandas Gandhi

- Known For : Leader of India's independence movement

- Also Known As : Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, Mahatma ("Great Soul"), Father of the Nation, Bapu ("Father"), Gandhiji

- Born : October 2, 1869 in Porbandar, India

- Parents : Karamchand and Putlibai Gandhi

- Died : January 30, 1948 in New Delhi, India

- Education : Law degree, Inner Temple, London, England

- Published Works : Mohandas K. Gandhi, Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth , Freedom's Battle

- Spouse : Kasturba Kapadia

- Children : Harilal Gandhi, Manilal Gandhi, Ramdas Gandhi, Devdas Gandhi

- Notable Quote : "The true measure of any society can be found in how it treats its most vulnerable members."

Mohandas Gandhi was born October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, India, the last child of his father Karamchand Gandhi and his fourth wife Putlibai. Young Gandhi was a shy, mediocre student. At age 13, he married Kasturba Kapadia as part of an arranged marriage. She bore four sons and supported Gandhi's endeavors until her 1944 death.

In September 1888 at age 18, Gandhi left India alone to study law in London. He attempted to become an English gentleman, buying suits, fine-tuning his English accent, learning French, and taking music lessons. Deciding that was a waste of time and money, he spent the rest of his three-year stay as a serious student living a simple lifestyle.

Gandhi also adopted vegetarianism and joined the London Vegetarian Society, whose intellectual crowd introduced Gandhi to authors Henry David Thoreau and Leo Tolstoy . He also studied the "Bhagavad Gita," an epic poem sacred to Hindus. These books' concepts set the foundation for his later beliefs.

Gandhi passed the bar on June 10, 1891, and returned to India. For two years, he attempted to practice law but lacked the knowledge of Indian law and the self-confidence necessary to be a trial lawyer. Instead, he took on a year-long case in South Africa.

At 23, Gandhi again left his family and set off for the British-governed Natal province in South Africa in May 1893. After a week, Gandhi was asked to go to the Dutch-governed Transvaal province. When Gandhi boarded the train, railroad officials ordered him to move to the third-class car. Gandhi, holding first-class tickets, refused. A policeman threw him off the train.

As Gandhi talked to Indians in South Africa, he learned that such experiences were common. Sitting in the cold depot that first night of his trip, Gandhi debated returning to India or fighting the discrimination. He decided that he couldn't ignore these injustices.

Gandhi spent 20 years bettering Indians' rights in South Africa, becoming a resilient, potent leader against discrimination. He learned about Indian grievances, studied the law, wrote letters to officials, and organized petitions. On May 22, 1894, Gandhi established the Natal Indian Congress (NIC). Although it began as an organization for wealthy Indians, Gandhi expanded it to all classes and castes. He became a leader of South Africa's Indian community, his activism covered by newspapers in England and India.

In 1896 after three years in South Africa, Gandhi sailed to India to bring his wife and two sons back with him, returning in November. Gandhi's ship was quarantined at the harbor for 23 days, but the real reason for the delay was an angry mob of whites at the dock who believed Gandhi was returning with Indians who would overrun South Africa.

Gandhi sent his family to safety, but he was assaulted with bricks, rotten eggs, and fists. Police escorted him away. Gandhi refuted the claims against him but refused to prosecute those involved. The violence stopped, strengthening Gandhi's prestige.

Influenced by the "Gita," Gandhi wanted to purify his life by following the concepts of aparigraha (nonpossession) and samabhava (equitability). A friend gave him "Unto This Last" by John Ruskin , which inspired Gandhi to establish Phoenix Settlement, a community outside Durban, in June 1904. The settlement focused on eliminating needless possessions and living in full equality. Gandhi moved his family and his newspaper, the Indian Opinion , to the settlement.

In 1906, believing that family life was detracting from his potential as a public advocate, Gandhi took the vow of brahmacharya (abstinence from sex). He simplified his vegetarianism to unspiced, usually uncooked foods—mostly fruits and nuts, which he believed would help quiet his urges.

Gandhi believed that his vow of brahmacharya allowed him the focus to devise the concept of satyagraha in late 1906. In the simplest sense, satyagraha is passive resistance, but Gandhi described it as "truth force," or natural right. He believed exploitation was possible only if the exploited and the exploiter accepted it, so seeing beyond the current situation provided power to change it.

In practice, satyagraha is nonviolent resistance to injustice. A person using satyagraha could resist injustice by refusing to follow an unjust law or putting up with physical assaults and/or confiscation of his property without anger. There would be no winners or losers; all would understand the "truth" and agree to rescind the unjust law.

Gandhi first organized satyagraha against the Asiatic Registration Law, or Black Act, which passed in March 1907. It required all Indians to be fingerprinted and carry registration documents at all times. Indians refused fingerprinting and picketed documentation offices. Protests were organized, miners went on strike, and Indians illegally traveled from Natal to the Transvaal in opposition to the act. Many protesters, including Gandhi, were beaten and arrested. After seven years of protest, the Black Act was repealed. The nonviolent protest had succeeded.

After 20 years in South Africa, Gandhi returned to India. By the time he arrived, press reports of his South African triumphs had made him a national hero. He traveled the country for a year before beginning reforms. Gandhi found that his fame conflicted with observing conditions of the poor, so he wore a loincloth ( dhoti ) and sandals, the garb of the masses, during this journey. In cold weather, he added a shawl. This became his lifetime wardrobe.

Gandhi founded another communal settlement in Ahmadabad called Sabarmati Ashram. For the next 16 years, Gandhi lived there with his family.

He was also given the honorary title of Mahatma, or "Great Soul." Many credit Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature, for awarding Gandhi this name. Peasants viewed Gandhi as a holy man, but he disliked the title because it implied he was special. He viewed himself as ordinary.

After the year ended, Gandhi still felt stifled because of World War I. As part of satyagraha , Gandhi had vowed never to take advantage of an opponent's troubles. With the British in a major conflict, Gandhi couldn't fight them for Indian freedom. Instead, he used satyagraha to erase inequities among Indians. Gandhi persuaded landlords to stop forcing tenant farmers to pay increased rent by appealing to their morals and fasted to convince mill owners to settle a strike. Because of Gandhi's prestige, people didn't want to be responsible for his death from fasting.

When the war ended, Gandhi focused on the fight for Indian self-rule ( swaraj ). In 1919, the British handed Gandhi a cause: the Rowlatt Act, which gave the British nearly free rein to detain "revolutionary" elements without trial. Gandhi organized a hartal (strike), which began on March 30, 1919. Unfortunately, the protest turned violent.

Gandhi ended the hartal once he heard about the violence, but more than 300 Indians had died and more than 1,100 were injured from British reprisals in the city of Amritsar. Satyagraha hadn't been achieved, but the Amritsar Massacre fueled Indian opinions against the British. The violence showed Gandhi that the Indian people didn't fully believe in satyagraha . He spent much of the 1920s advocating for it and struggling to keep protests peaceful.

Gandhi also began advocating self-reliance as a path to freedom. Since the British established India as a colony, Indians had supplied Britain with raw fiber and then imported the resulting cloth from England. Gandhi advocated that Indians spin their own cloth, popularizing the idea by traveling with a spinning wheel, often spinning yarn while giving a speech. The image of the spinning wheel ( charkha ) became a symbol for independence.

In March 1922, Gandhi was arrested and sentenced to six years in prison for sedition. After two years, he was released following surgery to find his country embroiled in violence between Muslims and Hindus. When Gandhi began a 21-day fast still ill from surgery, many thought he would die, but he rallied. The fast created a temporary peace.

In December 1928, Gandhi and the Indian National Congress (INC) announced a challenge to the British government. If India wasn't granted Commonwealth status by December 31, 1929, they would organize a nationwide protest against British taxes. The deadline passed without change.

Gandhi chose to protest the British salt tax because salt was used in everyday cooking, even by the poorest. The Salt March began a nationwide boycott starting March 12, 1930, when Gandhi and 78 followers walked 200 miles from the Sabarmati Ashram to the sea. The group grew along the way, reaching 2,000 to 3,000. When they reached the coastal town of Dandi on April 5, they prayed all night. In the morning, Gandhi made a presentation of picking up a piece of sea salt from the beach. Technically, he had broken the law.

Thus began an endeavor for Indians to make salt. Some picked up loose salt on the beaches, while others evaporated saltwater. Indian-made salt soon was sold nationwide. Peaceful picketing and marches were conducted. The British responded with mass arrests.

Protesters Beaten

When Gandhi announced a march on the government-owned Dharasana Saltworks, the British imprisoned him without trial. Although they hoped Gandhi's arrest would stop the march, they underestimated his followers. The poet Sarojini Naidu led 2,500 marchers. As they reached the waiting police, the marchers were beaten with clubs. News of the brutal beating of peaceful protesters shocked the world.

British viceroy Lord Irwin met with Gandhi and they agreed on the Gandhi-Irwin Pact, which granted limited salt production and freedom for the protesters if Gandhi called off the protests. While many Indians believed that Gandhi hadn't gotten enough from the negotiations, he viewed it as a step toward independence.

Independence

After the success of the Salt March, Gandhi conducted another fast that enhanced his image as a holy man or prophet. Dismayed at the adulation, Gandhi retired from politics in 1934 at age 64. He came out of retirement five years later when the British viceroy announced, without consulting Indian leaders, that India would side with England during World War II . This revitalized the Indian independence movement.

Many British parliamentarians realized they were facing mass protests and began discussing an independent India. Although Prime Minister Winston Churchill opposed losing India as a colony, the British announced in March 1941 that it would free India after World War II. Gandhi wanted independence sooner and organized a "Quit India" campaign in 1942. The British again jailed Gandhi.

Hindu-Muslim Conflict

When Gandhi was released in 1944, independence seemed near. Huge disagreements, however, arose between Hindus and Muslims. Because the majority of Indians were Hindu, Muslims feared losing political power if India became independent. The Muslims wanted six provinces in northwest India, where Muslims predominated, to become an independent country. Gandhi opposed partitioning India and tried to bring the sides together, but that proved too difficult even for the Mahatma.

Violence erupted; entire towns were burned. Gandhi toured India, hoping his presence could curb the violence. Although violence stopped where Gandhi visited, he couldn't be everywhere.

The British, seeing India headed for civil war, decided to leave in August 1947. Before leaving, they got the Hindus, against Gandhi's wishes, to agree to a partition plan . On August 15, 1947, Britain granted independence to India and to the newly formed Muslim country of Pakistan.

Millions of Muslims marched from India to Pakistan, and millions of Hindus in Pakistan walked to India. Many refugees died from illness, exposure, and dehydration. As 15 million Indians became uprooted from their homes, Hindus and Muslims attacked each other.

Gandhi once again went on a fast. He would only eat again, he stated, once he saw clear plans to stop the violence. The fast began on January 13, 1948. Realizing that the frail, aged Gandhi couldn't withstand a long fast, the sides collaborated. On January 18, more than 100 representatives approached Gandhi with a promise for peace, ending his fast.

Not everyone approved of the plan. Some radical Hindu groups believed that India shouldn't have been partitioned, blaming Gandhi. On January 30, 1948, the 78-year-old Gandhi spent his day discussing issues. Just past 5 p.m., Gandhi began the walk, supported by two grandnieces, to the Birla House, where he was staying in New Delhi, for a prayer meeting. A crowd surrounded him. A young Hindu named Nathuram Godse stopped before him and bowed. Gandhi bowed back. Godse shot Gandhi three times. Although Gandhi had survived five other assassination attempts, he fell to the ground, dead.

Gandhi's concept of nonviolent protest attracted the organizers of numerous demonstrations and movements. Civil rights leaders, especially Martin Luther King Jr. , adopted Gandhi's model for their own struggles.

Research in the second half of the 20th century established Gandhi as a great mediator and reconciler, resolving conflicts between older moderate politicians and young radicals, political terrorists and parliamentarians, urban intelligentsia and rural masses, Hindus and Muslims, as well as Indians and British. He was the catalyst, if not the initiator, of three major revolutions of the 20th century: movements against colonialism, racism, and violence.

His deepest strivings were spiritual, but unlike many fellow Indians with such aspirations, he didn't retire to a Himalayan cave to meditate. Rather, he took his cave with him everywhere he went. And, he left his thoughts to posterity: His collected writings had reached 100 volumes by the early 21st century.

- " Mahatma Gandhi: Indian Leader ." Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- " Mahatma Gandhi ." History.com.

- Gandhi's Historic March to the Sea in 1930

- 20 Facts About the Life of Mahatma Gandhi

- The British Raj in India

- Sarojini Naidu

- What Was the Partition of India?

- Jawaharlal Nehru, India's First Prime Minister

- Indira Gandhi Biography

- The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857

- The Indian Revolt of 1857

- History of India's Caste System

- Timeline of Indian History

- The Bengal Famine of 1943

- East India Company

- Pakistan | Facts and History

- Bangladesh: Facts and History

- 5 Men Who Inspired Martin Luther King, Jr. to Be a Leader

Mahatma Gandhi

Indian independence activist (1869–1948) / from wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, dear wikiwand ai, let's keep it short by simply answering these key questions:.

Can you list the top facts and stats about Mahatma Gandhi?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi ( ISO : Mōhanadāsa Karamacaṁda Gāṁdhī ; [pron 1] 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule . He inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. The honorific Mahātmā ( from Sanskrit 'great-souled, venerable' ), first applied to him in South Africa in 1914, is now used throughout the world.

Born and raised in a Hindu family in coastal Gujarat , Gandhi trained in the law at the Inner Temple in London and was called to the bar in June 1891, at the age of 22. After two uncertain years in India, where he was unable to start a successful law practice, Gandhi moved to South Africa in 1893 to represent an Indian merchant in a lawsuit. He went on to live in South Africa for 21 years. There, Gandhi raised a family and first employed nonviolent resistance in a campaign for civil rights. In 1915, aged 45, he returned to India and soon set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against discrimination and excessive land-tax.

Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women's rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability , and, above all, achieving swaraj or self-rule. Gandhi adopted the short dhoti woven with hand-spun yarn as a mark of identification with India's rural poor. He began to live in a self-sufficient residential community , to eat simple food, and undertake long fasts as a means of both introspection and political protest. Bringing anti-colonial nationalism to the common Indians, Gandhi led them in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930 and in calling for the British to quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned many times and for many years in both South Africa and India.

Gandhi's vision of an independent India based on religious pluralism was challenged in the early 1940s by a Muslim nationalism which demanded a separate homeland for Muslims within British India . In August 1947, Britain granted independence, but the British Indian Empire was partitioned into two dominions , a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan . As many displaced Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs made their way to their new lands, religious violence broke out, especially in the Punjab and Bengal . Abstaining from the official celebration of independence , Gandhi visited the affected areas, attempting to alleviate distress. In the months following, he undertook several hunger strikes to stop the religious violence. The last of these was begun in Delhi on 12 January 1948, when Gandhi was 78. The belief that Gandhi had been too resolute in his defence of both Pakistan and Indian Muslims spread among some Hindus in India. Among these was Nathuram Godse , a militant Hindu nationalist from Pune , western India, who assassinated Gandhi by firing three bullets into his chest at an interfaith prayer meeting in Delhi on 30 January 1948.

Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, is commemorated in India as Gandhi Jayanti , a national holiday , and worldwide as the International Day of Nonviolence . Gandhi is considered to be the Father of the Nation in post-colonial India. During India's nationalist movement and in several decades immediately after, he was also commonly called Bapu ( Gujarati endearment for "father", roughly "papa", [2] "daddy" [3] ).

May 26, 2024

Life Story of Famous People

Short Bio » Civil Rights Leader » Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the preeminent leader of the Indian independence movement in British-ruled India. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 to a Hindu Modh Baniya family in Porbandar (also known as Sudamapuri ), a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula and then part of the small princely state of Porbandar in the Kathiawar Agency of the Indian Empire. Employing nonviolent civil disobedience, Gandhi led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world.

Gandhi famously led Indians in challenging the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (250 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930, and later in calling for the British to Quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned for many years, upon many occasions, in both South Africa and India. One of Gandhi’s major strategies, first in South Africa and then in India, was uniting Muslims and Hindus to work together in opposition to British imperialism. In 1919–22 he won strong Muslim support for his leadership in the Khilafat Movement to support the historic Ottoman Caliphate. By 1924, that Muslim support had largely evaporated.

Time magazine named Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930. Gandhi was also the runner-up to Albert Einstein as “Person of the Century” at the end of 1999. The Government of India awarded the annual Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa’s struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, was a prominent non-Indian recipient. In 2011, Time magazine named Gandhi as one of the top 25 political icons of all time. Gandhi did not receive the Nobel Peace Prize, although he was nominated five times between 1937 and 1948, including the first-ever nomination by the American Friends Service Committee, though he made the short list only twice, in 1937 and 1947.

Indians widely describe Gandhi as the father of the nation. In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly declared Gandhi’s birthday 2 October as “the International Day of Nonviolence.

More Info: Wiki

Fans Also Viewed

Published in Historical Figure

More Celebrities

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

Biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of Nation)

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi , more popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi . His birth place was in the small city of Porbandar in Gujarat (October 2, 1869 - January 30, 1948). Mahatma Gandhi's father's name was Karamchand Gandhi, and his mother's name was Putlibai Gandhi. He was a politician, social activist, Indian lawyer, and writer who became the prominent Leader of the nationwide surge movement against the British rule of India. He came to be known as the Father of The Nation. October 2, 2023, marks Gandhi Ji’s 154th birth anniversary , celebrated worldwide as International Day of Non-Violence, and Gandhi Jayanti in India.

Gandhi Ji was a living embodiment of non-violent protests (Satyagraha) to achieve independence from the British Empire's clutches and thereby achieve political and social progress. Gandhi Ji is considered ‘The Great Soul’ or ‘ The Mahatma ’ in the eyes of millions of his followers worldwide. His fame spread throughout the world during his lifetime and only increased after his demise. Mahatma Gandhi , thus, is the most renowned person on earth.

Education of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's education was a major factor in his development into one of the finest persons in history. Although he attended a primary school in Porbandar and received awards and scholarships there, his approach to his education was ordinary. Gandhi joined Samaldas College in Bhavnagar after passing his matriculation exams at the University of Bombay in 1887.

Gandhiji's father insisted he become a lawyer even though he intended to be a docto. During those days, England was the centre of knowledge, and he had to leave Smaladas College to pursue his father's desire. He was adamant about travelling to England despite his mother's objections and his limited financial resources.

Finally, he left for England in September 1888, where he joined Inner Temple, one of the four London Law Schools. In 1890, he also took the matriculation exam at the University of London.

When he was in London, he took his studies seriously and joined a public speaking practice group. This helped him get over his nervousness so he could practise law. Gandhi had always been passionate about assisting impoverished and marginalised people.

Mahatma Gandhi During His Youth

Gandhi was the youngest child of his father's fourth wife. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the dewan Chief Minister of Porbandar, the then capital of a small municipality in western India (now Gujarat state) under the British constituency.

Gandhi's mother, Putlibai, was a pious religious woman.Mohandas grew up in Vaishnavism, a practice followed by the worship of the Hindu god Vishnu, along with a strong presence of Jainism, which has a strong sense of non-violence.Therefore, he took up the practice of Ahimsa (non-violence towards all living beings), fasting for self-purification, vegetarianism, and mutual tolerance between the sanctions of various castes and colours.

His adolescence was probably no stormier than most children of his age and class. Not until the age of 18 had Gandhi read a single newspaper. Neither as a budding barrister in India nor as a student in England nor had he shown much interest in politics. Indeed, he was overwhelmed by terrifying stage fright each time he stood up to read a speech at a social gathering or to defend a client in court.

In London, Gandhiji's vegetarianism missionary was a noteworthy occurrence. He became a member of the executive committee in joined the London Vegetarian Society. He also participated in several conferences and published papers in its journal. Gandhi met prominent Socialists, Fabians, and Theosophists like Edward Carpenter, George Bernard Shaw, and Annie Besant while dining at vegetarian restaurants in England.

Political Career of Mahatma Gandhi

When we talk about Mahatma Gandhi’s political career, in July 1894, when he was barely 25, he blossomed overnight into a proficient campaigner . He drafted several petitions to the British government and the Natal Legislature signed by hundreds of his compatriots. He could not prevent the passage of the bill but succeeded in drawing the attention of the public and the press in Natal, India, and England to the Natal Indian's problems.

He still was persuaded to settle down in Durban to practice law and thus organised the Indian community. The Natal Indian Congress was founded in 1894, and he became the unwearying secretary. He infused a solidarity spirit in the heterogeneous Indian community through that standard political organisation. He gave ample statements to the Government, Legislature, and media regarding Indian Grievances.

Finally, he got exposed to the discrimination based on his colour and race, which was pre-dominant against the Indian subjects of Queen Victoria in one of her colonies, South Africa.

Mahatma Gandhi spent almost 21 years in South Africa. But during that time, there was a lot of discrimination because of skin colour. Even on the train, he could not sit with white European people. But he refused to do so, got beaten up, and had to sit on the floor. So he decided to fight against these injustices, and finally succeeded after a lot of struggle.

It was proof of his success as a publicist that such vital newspapers as The Statesman, Englishman of Calcutta (now Kolkata) and The Times of London editorially commented on the Natal Indians' grievances.

In 1896, Gandhi returned to India to fetch his wife, Kasturba (or Kasturbai), their two oldest children, and amass support for the Indians overseas. He met the prominent leaders and persuaded them to address the public meetings in the centre of the country's principal cities.

Unfortunately for him, some of his activities reached Natal and provoked its European population. Joseph Chamberlain, the colonial secretary in the British Cabinet, urged Natal's government to bring the guilty men to proper jurisdiction, but Gandhi refused to prosecute his assailants. He said he believed the court of law would not be used to satisfy someone's vendetta.

Political Teacher of Mahatma Gandhi

Gopal Krishna Gokhale was one of the prominent political teachers and mentors of Mahatma Gandhi. Gokhale, a renowned Indian nationalist leader, played a significant role in shaping Gandhi's political ideology and approach to leadership. He emphasized the importance of nonviolence, constitutional methods, and constructive work in achieving social and political change. Gandhi referred to Gokhale as his political guru and credited him with influencing many of his principles and strategies in the Indian freedom struggle. Gokhale's teachings and guidance had a profound impact on Gandhi's development as a leader and advocate for India's independence.

Death of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi's death was a tragic event and brought clouds of sorrow to millions of people. On the 29th of January, a man named Nathuram Godse came to Delhi with an automatic pistol. About 5 pm in the afternoon of the next day, he went to the Gardens of Birla house, and suddenly, a man from the crowd came out and bowed before him.

Then Godse fired three bullets at his chest and stomach, who was Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi was in such a posture that he to the ground. During his death, he uttered: “Ram! Ram!” Although someone could have called the doctor in this critical situation during that time, no one thought of that, and Gandhiji died within half an hour.

How Shaheed Day is Celebrated at Gandhiji’s Samadhi (Raj Ghat)?

As Gandhiji died on January 30, the government of India declared this day as ‘Shaheed Diwas’.

On this day, the President, the Vice-President, the Prime Minister, and the Defence Minister every year gather at the Samadhi of Mahatma Gandhi at the Raj Ghat memorial in Delhi to pay tribute to Indian martyrs and Mahatma Gandhi, followed by a two-minute silence.

On this day, many schools host events where students perform plays and sing patriotic songs. Martyrs' Day is also observed on March 23 to honour the lives and sacrifices of Sukhdev Thapar, Shivaram Rajguru, and Bhagat Singh.

Gandhi believed it was his duty to defend India's rights. Mahatma Gandhi had a significant role in attaining India's independence from the British. He had an impact on many individuals and locations outside India. Gandhi also influenced Martin Luther King, and as a result, African-Americans now have equal rights. Peacefully winning India's independence, he altered the course of history worldwide.

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi Biography and Political Career

1. What was people's reaction after Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi?

When Nathuram Godse killed Mahatma Gandhi, people shouted to kill Nathuram. After killing Mahatma Gandhi, Nathuram Godse tried to kill himself but could not do so since the police seized his weapons and took him to jail. After that, Gandhiji's body was laid in the garden with a white cloth covered on his face. All the lights were turned off in honour of him. Then on the radio, honourable Prime minister Pandit Nehru Ji declared sadly that the Nation's Father was no more.

2. How vegetarianism impacted Mahatma Gandhi’s time in London?

During the three years he spent in England, he was in a great dilemma with personal and moral issues rather than academic ambitions.

The sudden transition from Porbandar's half-rural atmosphere to London's cosmopolitan life was not an easy task for him. And he struggled powerfully and painfully to adapt himself to Western food, dress, and etiquette, and he felt awkward.

His vegetarianism became a continual source of embarrassment and was like a curse to him; his friends warned him that it would disrupt his studies, health, and well-being. Fortunately, he came across a vegetarian restaurant and a book providing a well-defined defence of vegetarianism.

His missionary zeal for vegetarianism helped draw the pitifully shy youth out of his shell and gave him a new and robust personality. He also became a member of the London Vegetarian Society executive committee, contributing articles to its journal and attending conferences.

3. Who was the first person to write a biography of Mahatma Gandhi (Father of The Nation)?

Christian missionary Joseph Doke had written the first biography of Bapu. The best part is that Gandhiji had still not acquired the status of Mahatma when this biography was written.

4. Who was Gandhiji’s favorite writer?

Gandhiji’s favorite writer was Leo Tolstoy.

5. What is Mahatma Gandhi’s date of birth?

Mahatma Gandhi's date of birth is October 2, 1869. We celebrate every year on October 2nd as Mahatma Gandhi Jayanti.

6. Which are the famous Mahatma Gandhi books?

Mahatma Gandhi authored several influential books and writings that have left a lasting impact on the world. Some of his famous books include:

Autobiography

Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule

Satyagraha in South Africa

Young India

The Essential Gandhi

These books reflect Gandhi's deep commitment to nonviolence, truth, and social justice, making them essential reads for those interested in his life and principles.

- Get Featured

- Our Patreon

- Biographies

Mahatma Gandhi: Biography, Beliefs, Religion

The biography of Mahatma Gandhi presents an intricate journey of a man deeply rooted in his beliefs and principles. His life story showcases a blend of spiritual, philosophical, and political endeavors that had profound impacts within and beyond religion. Across diverse contexts, Gandhi’s name resonates with notions of peace, nonviolence, and resilience. Dive into the comprehensive narrative of this influential figure and understand the ethos that defined his path.

Table of Contents

Biography Summary

Early Life and Education Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known as Mahatma Gandhi, was born on October 2, 1869, and tragically died on January 30, 1948. A beacon of peace and nonviolence, Gandhi was an exemplary figure who battled colonial subjugation and heralded India’s independence from oppressive British rule. His unwavering dedication to nonviolent resistance was instrumental in inspiring movements for civil rights and freedom on a global scale.

South African Sojourn

In the coastal state of Gujarat, within a devout Hindu family, Gandhi’s roots were planted. His legal proficiency was honed at the Inner Temple, London, where he achieved his accolade of being called to the bar in June 1891 at the age of 22. Struggling to cultivate a successful law practice in India, Gandhi sought opportunities in South Africa in 1893, representing an Indian merchant in legal matters. South Africa became his home for 21 years, where he not only nurtured a family but also cultivated the strategy of nonviolent resistance as a weapon against injustice and discrimination.

Return to India and National Leadership

1915 marked his return to India, and at 45, Gandhi embarked on a mission to consolidate peasants, farmers, and laborers, championing causes against discrimination and excessive land tax. Steering the Indian National Congress in 1921, his leadership illuminated paths toward mitigating poverty, broadening women’s rights, fostering religious and ethnic harmony, and terminating untouchability. With the embodiment of swaraj or self-rule as his objective, Gandhi became a paragon of simplicity, adopting a lifestyle resonating with the underprivileged.

Defiance Against British Rule

In a defining moment of defiance against British rule, Gandhi spearheaded the 400 km Dandi Salt March in 1930, challenging the stringent British salt tax. His clarion call for the British to “Quit India” echoed through the nation in 1942. Despite numerous incarcerations in South Africa and India, Gandhi’s spirit remained unyielding.

Partition and the Struggle for Peace

As the winds of freedom began to blow across the Indian subcontinent in the early 1940s, they carried with them the storms of partition, driven by the burgeoning demand for a separate Muslim homeland. The twilight of British rule in August 1947 unfurled the dawn of independence, heralding the birth of India and Pakistan. A crucible of turbulence, upheaval, and religious animosity ensued, marring the euphoria of emancipation with the stains of violence and bloodshed.

Gandhi, who envisioned an India resonating with religious pluralism, became a crucible of solace and peace, endeavoring tirelessly to assuage the tempests of violence and discord. Embarking on several hunger strikes, his life became an epitome of sacrifice aimed at halting the horrific religious carnage. His journey, however, was tragically ended by the bullets of Nathuram Godse, a militant Hindu nationalist, on January 30, 1948.

Remembered and revered as the Father of the Nation in the tapestry of post-colonial India, Gandhi’s legacy is enshrined in his unyielding devotion to peace and nonviolence. The global canvas commemorates his birth on October 2 as Gandhi Jayanti and the International Day of Nonviolence, celebrating the luminary who illuminated pathways towards peace, tolerance, and harmony.

Early Life and Background

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a coastal town on the Kathiawar Peninsula in the then princely state of Porbandar, part of the Kathiawar Agency of the British Raj. He was born into a Gujarati Hindu Modh Bania family with a prominent status in the region. His father, Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi (1822–1885), held the esteemed Porbandar state’s dewan (chief minister) position, contributing actively to the governance and administration despite having a modest educational background.

The familial lineage of the Gandhis originated from Kutiana village in what was then the Junagadh State. Karamchand, Gandhi’s father, was particularly experienced in state administration, and his influential tenure included a remarriage with Putlibai (1844–1891), who became an essential figure in the family and Gandhi’s life. This union produced several children, with Mohandas being the youngest, born in a rather humble setting within the Gandhi family residence.

Childhood Influences and Education

Gandhi’s early years were marked by a blend of traditional Indian stories and diverse religious exposure, pivotal in shaping his moral compass and philosophical standings. His internalization of truth and love as supreme virtues was profoundly influenced by epic Indian classics, leaving an indelible mark on his conscience and thought processes. A salient feature of Gandhi’s upbringing was the eclectic religious atmosphere at home, rooted in Hindu traditions, enriched with teachings from various texts like the Bhagavad Gita, the Bhagavata Purana, and several others, offering him a well-rounded spiritual foundation.

A strategic relocation occurred in 1874 when Karamchand moved to Rajkot, assuming the role of a counselor to its ruler, ensuring a degree of security and prestige despite its lesser stature than Porbandar. Gandhi commenced his formal education in Rajkot, engaging in fundamental studies, including arithmetic, history, and the Gujarati language, at a school close to his residence. Furthering his education, he joined Alfred High School, where his academic journey was characterized as average, marked by a noticeable reservation and lack of interest in physical games and activities.

Personal Life and Marriage

Aligning with the prevailing customs of the region, Gandhi, at the age of 13, entered into an arranged marriage in May 1883 with Kasturbai Gokuldas Kapadia, commonly referred to as Kasturba or Ba. Traditional practices marked this marital union, and the initial phases saw Gandhi battling internal feelings of jealousy and possessiveness alongside navigating the typical aspirations and challenges faced by adolescents.

The demise of Karamchand in late 1885 and the death of Gandhi’s firstborn in the same period marked a phase of profound sorrow and loss for Gandhi. Overcoming these personal challenges, Gandhi and Kasturba went on to have four more sons: Harilal (born in 1888), Manilal (born in 1892), Ramdas (born in 1897), and Devdas (born in 1900).

Gandhi’s pursuit of higher education saw him graduate from high school in Ahmedabad in November 1887 and enroll at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar State in January 1888. However, his stint at Samaldas College was short-lived, resulting in a return to his family in Porbandar, marking a temporary pause in his educational journey.

Education: Law Student in London

The pivotal chapter of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s life unfolded when he embarked on a journey to London to delve into legal studies. Driven by advice from Mavji Dave Joshiji, a close Brahmin priest and confidant of the Gandhi family, the voyage was set into motion amidst familial uncertainties and emotional deliberations. Kasturba, Gandhi’s wife, had recently given birth to their first surviving son, Harilal, in July 1888, and the familial reservations, primarily from his mother Putlibai and uncle Tulsidas, weighed heavily against the backdrop of traditional and ethical considerations.

On August 10, 1888, an 18-year-old Gandhi embarked on his journey from Porbandar to Mumbai (then known as Bombay), facing a storm of warnings and skepticism from his community, which fervently questioned the moral implications of his travel to the West. Despite assurances of his unwavering adherence to his vows and cultural norms, Gandhi faced social repercussions, culminating in his excommunication from his caste. Undeterred, Gandhi sailed from Mumbai to London on September 4, 1888, entering a new phase of his life marked by exploration and academic pursuits.