Operational Risk Management: A Complete Guide to a Successful Operational Risk Framework by Philippa X. Girling

Get full access to Operational Risk Management: A Complete Guide to a Successful Operational Risk Framework and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

Case Studies

In this chapter, we dig deeper into four case studies: JPMorgan Whale, UBS Unauthorized Trading, Knight Capital Technology Glitch, and Standard Chartered Anti–Money Laundering Scandal.

JPMORGAN WHALE: RISKY OR FRISKY?

Are large losses at banks always a sign of poor governance, or are they sometimes merely the realization of losses that were expected, and even planned for, in the well-governed risk management of the firm? In May 2012, JPMorgan announced that it had lost $2 billion (possibly much more), on a hedging strategy that was being driven by Bruno Michel Iksil, aka “The London Whale” in its chief investment office. Was this poor governance, or were these losses predictable under JPMorgan's risk management practices? Was this acceptable risky behavior, or was it frisky misbehavior?

You can't win the game all of the time, and for every winner, there is a loser somewhere in the financial system. For each loss event that happens, we should ask the same question: Were these losses within the boundaries of the bank's known risk, or were they out of control?

We have all heard the worn out caveats “investments may go down as well as up,” and we all know that the banking industry sometimes makes money on its risk-taking activities and sometimes loses it on those same activities. So why all the noise in the press about these JPMorgan losses?

- “London Whale Harpooned” 1

- “JPMorgan's ‘Whale' Causes a Splash” 2

- “Beached London Whale” 3

Anything over a billion dollars ...

Get Operational Risk Management: A Complete Guide to a Successful Operational Risk Framework now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

The future of operational-risk management in financial services

New forces are creating new demands for operational-risk management in financial services. Breakthrough technology, increased data availability, and new business models and value chains are transforming the ways banks serve customers, interact with third parties, and operate internally. Operational risk must keep up with this dynamic environment, including the evolving risk landscape.

Legacy processes and controls have to be updated to begin with, but banks can also look upon the imperative to change as an improvement opportunity. The adoption of new technologies and the use of new data can improve operational-risk management itself. Within reach is more targeted risk management, undertaken with greater efficiency, and truly integrated with business decision making.

The advantages for financial-services firms that manage to do this are significant. Already, efforts to address the new challenges are bringing measurable bottom-line impact. For example, one global bank tackled unacceptable false-positive rates in anti–money laundering (AML) detection—which were as high as 96 percent. Using machine learning to identify crucial data flaws, the bank made necessary data-quality improvements and thereby quickly eliminated an estimated 35,000 investigative hours. A North American bank assessed conduct-risk exposures in its retail sales force. Using advanced-analytics models to monitor behavioral patterns among 20,000 employees, the bank identified unwanted anomalies before they became serious problems. The cases for change are in fact diverse and compelling, but transformations can present formidable challenges for functions and their institutions.

The current state

Operational risk is a relatively young field: it became an independent discipline only in the past 20 years. While banks have been aware of risks associated with operations or employee activities for a long while, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), in a series of papers published between 1999 and 2001, elevated operational risk to a distinct and controllable risk category requiring its own tools and organization. 1 The standard Basel Committee on Banking Supervision definition of operational (or nonfinancial) risk is “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, and systems or from external events. See Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: Working paper on the regulatory treatment of operational risk , Bank for International Settlements, September 2001, bis.org. In the first decade of building operational-risk-management capabilities, banks focused on governance, putting in place foundational elements such as loss-event reporting and risk-control self-assessments (RCSAs) and developing operational-risk capital models. The financial crisis precipitated a wave of regulatory fines and enforcement actions on misselling, questionable mortgage-foreclosure practices, financial crimes, London Inter-bank Offered Rate (LIBOR) fixing, and foreign-exchange misconduct. As these events worked their way through the banking system, they highlighted weaknesses of earlier risk practices. Institutions responded by making significant investments in operational-risk capabilities. They developed risk taxonomies beyond the BCBS categories, put in place new risk-identification and risk-assessment processes, and created extensive controls and control-testing processes. While the industry succeeded in reducing industry-wide regulatory fines, losses from operational risk have remained elevated (Exhibit 1).

Intrinsic difficulties

While banks have made good progress, managing operational risk remains intrinsically difficult, for a number of reasons. Compared with financial risk such as credit or market risk, operational risk is more complex, involving dozens of diverse risk types. Second, operational-risk management requires oversight and transparency of almost all organizational processes and business activities. Third, the distinguishing definitions of the roles of the operational-risk function and other oversight groups—especially compliance, financial crime, cyberrisk, and IT risk—have been fluid. Finally, until recently, operational risk was less easily measured and managed through data and recognized limits than financial risk.

This last constraint has been lifted in recent years: granular data and measurement on operational processes, employee activity, customer feedback, and other sources of insight are now widely available. Measurement remains difficult, and risk teams still face challenges in bringing together diverse sources of data. Nonetheless, data availability and the potential applications of analytics have created an opportunity to transform operational-risk detection, moving from qualitative, manual controls to data-driven, real-time monitoring.

As for the other challenges, they have, if anything, steepened. Operational complexity has increased. The number and diversity of operational-risk types have enlarged, as important specialized-risk categories become more defined, including unauthorized trading, third-party risk, fraud, questionable sales practices, misconduct, new-product risk, cyberrisk, and operational resilience.

At the same time, digitization and automation have been changing the nature of work, reducing traditional human errors but creating new change-management risks; fintech partnerships create cyberrisks and produce new single points of failure; the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) raises issues of decision bias and ethical use of customer data. Finally, the lines between the operational-risk-management function and other second-line groups, such as compliance, continue to shift. Banks have invested in harmonizing risk taxonomies and assessments, but most recognize that significant overlap remains. This creates frustration among business units and frontline partners.

Taken together, these factors explain why operational-risk management remains intrinsically difficult and why the effectiveness of the discipline —as measured by consumer complaints, for example—has been disappointing (Exhibit 2).

Looking ahead

Against these challenges, risk practitioners are seeking to develop better tools, frameworks, and talent. Leading companies are discarding the “rearview mirror” approach, defined by thousands of qualitative controls. For effective operational-risk management, suitable to the new environment, these organizations are refocusing the front line on business resiliency and critical vulnerabilities. They are adopting data-driven risk measurement and shifting detection tools from subjective control assessments to real-time monitoring.

The objective is for operational-risk management to become a valuable partner to the business. Banks need to take specific actions to move the function from reporting and aggregation of first-line controls to providing expertise and thought partnership. The areas where the function will help execute business strategy include operational strengths and vulnerabilities, new-product design, and infrastructure enhancements, as well as other areas that allow the enterprise to operate effectively and prevent undue large-scale risk issues.

Defining next-generation operational-risk management

The operational-risk discipline needs to evolve in four areas: 1) the mandate needs to expand to include second-line oversight, to support operational excellence and business-process resiliency; 2) analytics-driven issue detection and real-time risk reporting have to replace manual risk assessments; 3) talent needs to be realigned as digitization progresses and data and analytics are rolled out: banks will need specialists to manage specific risk types such as cyberrisk, fraud, and conduct risk; and 4) human-factor risks will have to be monitored and assessed—including those that relate to misconduct (such as sexual harassment) and to diversity and inclusion.

The evolution includes the shift to real-time detection and action. This will involve the adoption of more agile ways of working, with greater use of cross-disciplinary teams that can respond quickly to arising issues, near misses, and emerging risks or threats to resilience.

1. Develop second-line oversight to ensure operational excellence and business-process resiliency

The original role of operational-risk management was focused on detecting and reporting nonfinancial risks, such as regulatory, third-party, and process risk. We believe that this mandate should expand so that the second line is an effective partner to the first line, playing a challenge role to support the fundamental resiliency of the operating model and processes. A breakdown in processes is at the core of many nonfinancial risks today, including negative regulatory outcomes, such as missing disclosures, customer and client disruption, and revenue and reputational costs. The operational-risk-management function should help chief risk officers and other senior managers answer several key questions, such as: Have we designed business processes in each area to provide consistent, positive customer outcomes? Do these processes operate well in both normal and stress conditions? Is our change-management process robust enough to prevent disruptions? Is the operating model designed to limit risk from bad actors?

Untransformed operational-risk-management functions have limited insight into the strength of operational processes or they rely on an extensive inventory of controls to ensure quality. Controls, however, are not effective in monitoring process resilience. A transaction-processing system, for example, may have reconciliation controls (such as a line of checkers) that perform well under normal conditions but cannot operate under stress. This is because the controls are fundamentally reliant on manual activities. Similarly, controls on IT infrastructure may not prevent a poorly executed platform transition from leading to large customer disruptions and reputational losses.

New frameworks and tools are therefore needed to properly evaluate the resiliency of business processes, challenge business management as appropriate, and prioritize interventions. These frameworks should support the following types of actions:

- Map processes, risks, and controls. Map the processes, along with associated risks and controls, including overall complexity, number of handoffs involved, and automation versus reliance on manual activities (particularly when the danger is high for negative customer outcomes or regulatory mistakes). This work will ideally be done in conjunction with systemic controls embedded in the process; end-to-end process ownership minimizes handoffs and maximizes collaboration.

- Identify supporting technology. Identify and understand the points where processes rely on technology.

- Monitor risks and controls. Create mechanisms and metrics (such as higher-than-normal volumes) to enable the monitoring of risk levels and control effectiveness, in real time wherever possible.

- Link resource planning to processes. Link resource planning to the emergent understanding of processes and associated needs. Be ready to scale capacity up or down according to the results of process monitoring.

- Reinforce needed behavior. Ensure reinforcement mechanisms for personal conduct, using communications, training, performance management, and incentives.

- Enable feedback. Establish feedback mechanisms for flagging potential issues, undertaking root-cause analysis, and updating or revising processes as needed to address the causes.

- Establish change management. Establish systematic, ongoing change management to ensure the right talent is in place, test processes and capacity, and provide guidance, particularly for technology.

2. Transform risk detection with data and real-time analytics

In response to regulatory concerns over sales practices, most banks comprehensively assessed their sales-operating models, including sales processes, product features, incentives, frontline-management routines, and customer-complaint processes. Many of these assessments went beyond the traditional responsibilities of operational-risk management, yet they highlight the type of discipline that will become standard practice. While making advances in some areas, banks still rely on many highly subjective operational-risk detection tools, centered on self-assessment and control reviews. Such tools have been ineffective in detecting cyberrisk, fraud, aspects of conduct risk, and other critical operational-risk categories. Additionally, they miss low-frequency, high-severity events, such as misconduct among a small group of frontline employees. Finally, some traditional detection techniques, such as rules-based cyberrisk and trading alerts, have false-positive rates of more than 90 percent. Many self-assessments in the first and second line consequently require enormous amounts of manual work but still miss major issues.

Targeted analytics tools

Advanced analytics has applications in all, or nearly all, areas of operational risk. It is creating significant improvements in detecting operational risks, revealing risks more quickly, and reducing false positives. Whether in information security, data, compliance, technology and systems, process failure, or even personal security and other human-factor risks, the advanced-analytics advantage is becoming increasingly evident. Some applications are described below:

- Anti–money laundering. Replacing rules-driven alerts with machine-learning models can reduce false positives and focus resources on cases that actually require investigation.

- Conduct. Analytics engines can identify suspicious sales patterns, connecting the dots across sales, product usage, incentives, and customer complaints (for example, increases in nonactivated deposits, accounts sold by a retail banker, or trades triggered by a wealth-management adviser as they approach compensation breakpoints). Trade-monitoring analytics can mine trading and communication patterns for potential markers of conduct risk.

- Cyberrisk. Machine learning can analyze sources of signals, identify emerging threats, replace existing rules-based triggers, and reduce false-positive alerts.

- Fraud. Machine learning, including unsupervised techniques, can identify fraudulent transactions and reduce false positives; synthetic-ID-fraud analytics use external, third-party data, in accordance with all local regulation, to analyze the depth and consistency in the identity profiles of new customers.

- Process quality and regulatory risks. Automated call surveillance using natural-language processing can monitor adherence to disclosure requirements. Systemic quality-control touchpoints can check the accuracy of decisions, disclosures, and filings against customer-provided information and regulatory rules (for example, the accuracy of a bankruptcy filing against the system of record information).

- Third-party risk. Models can be developed that quantify the reliance on key third parties (including hidden fourth-party exposures) to drive better business-continuity planning and bring a risk-based perspective to vendor assessment and selection.

Operational-risk managers must therefore rethink their approaches to issue detection. Advances in data and analytics can help. Banks can now tap into large repositories of structured and unstructured data to identify risk issues across operational-risk categories, moving beyond reliance on self-assessments and subjective controls. These emerging detection tools might best be described in two broad categories:

- Real-time risk indicators include real-time testing of operational processes and controls and risk metrics that identify areas operating under stress, spikes in transaction volumes, and other determinants of risk levels.

- Targeted analytics tools can connect the data dots to detect potential risk issues (see sidebar “Targeted analytics tools”). By mining sales and customer data, banks can detect potentially unauthorized sales. Machine-learning models can detect cyberrisk levels, fraud, and potential money laundering . As long as all privacy measures are respected, institutions can use natural-language processing to analyze calls, emails, surveys, and social-media posts to identify spikes in risk topics raised by customers in real time.

Exhibit 3 shows how a risk manager using natural-language processing can identify a spike in customer complaints related to the promotion of new accounts. Looking into the underlying complaints and call records, the manager would be able to identify issues in how offers are made to customers.

A number of banks are investing in objective, real-time risk indicators to supplement or replace subjective assessments. These indicators help risk managers track general operational health, such as staffing sufficiency, processing times, and inventories. They also provide early warnings of process risks, such as inaccurate decisions or disclosures, and the results of automated exception reporting and control testing.

Together, analytics and real-time reporting can transform operational-risk detection, enabling banks to move away from qualitative self-assessments to automated real-time risk detection and transparency. The journey is difficult—it requires that institutions overcome challenges in data aggregation and building risk analytics at scale—yet it will result in more effective and efficient risk detection.

3. Develop talent and the tools to manage specialized risk types

Examples of specialized expertise.

Risk category: Cyberrisk

Expertise needed for challenge and oversight

- Pathways to vulnerability (such as the impact of a threat like NotPetya)

- The bank’s most valuable assets (the “crown jewels”)

- Sources of exposure for a given organization

Talent profiles

- Cybersecurity background

- Senior status to engage the business and technology organizations

Risk category: Fraud

- Fraud patterns (for instance, through the dark web)

- Technology and cybersecurity

- Interdependencies across fraud, cybersecurity, IT, and business-product decisions

- Former senior technology managers

- Cybersecurity professionals, ideally with an analytics background

Risk category: Conduct

- Ways employees can game the system in each business unit (for instance, retail, wealth, and capital markets)

- Specific behavioral patterns, such as how traders could harm client interests for their own gain

- Former branch managers and frontline supervisors

- Former traders and back-office managers

- First-line risk managers with experience in investigating conduct issues

A range of emerging risks, all of which fall under the operational-risk umbrella, present new challenges for banks. To manage these risks—in areas such as technology, data, and financial crime—banks need specialized knowledge and tools. For example, managing fraud risk requires a deep understanding of fraud typologies, new and emerging vulnerabilities, and the effectiveness of first-line processes and controls. Similarly, oversight of conduct risks requires up-to-date knowledge about how systems can be “gamed” in each business line. In capital markets, for instance, some products are more susceptible than others to nontransparent communication, misselling, misconduct in products, and manipulation by unscrupulous employees. Operational-risk officers will need to rethink their risk organization and recruit talent to support process-centric risk management and advanced analytics. These changes in talent composition are significant and different from what most banks currently have in place (see sidebar “Examples of specialized expertise”).

Bank employees drive corporate performance but are also a potential source of operational risk.

With specialized talent in place, banks will then need to integrate the people and work of the operational-risk function as never before. To meet the challenge, organizations have to prepare leaders, business staff, and specialist teams to think and work in new ways. They must help them adapt to process-driven risk management and understand the potential applications of advanced analytics. The overall objective is to create an operational-risk function that embraces agile development, data exploration, and interdisciplinary teamwork.

4. Manage human-factor risks

Bank employees drive corporate performance but are also a potential source of operational risk. In recent years, conduct issues in sales and instances of LIBOR and foreign-exchange manipulation have elevated the human factor in the nonfinancial-risk universe. In the past, HR was mainly responsible for addressing conduct risk, as part of its oversight role in hiring and investigating conduct issues. As the potential for human-factor risks to inflict serious damage has become more apparent, however, banks are recognizing that this oversight must be included in the operational-risk-management function.

Developing effective risk-oversight frameworks for human-factor risks is not an easy task, as these risks are diverse and differ from many other operational-risk types. Some involve behavioral transgressions among employees; others involve the abuse of insider organizational knowledge and finding ways around static controls. These risks have more to do with culture, personal motives, and incentives, that is, than with operational processes and infrastructure. And they are hard to quantify and prioritize in organizations with many thousands of employees in dozens or even hundreds of functions.

To prioritize areas of oversight and intervention, leading operational-risk executives are taking the following steps. They first determine which groups within the organization present disproportionate human-factor risks, including misconduct, mistakes with heavy regulatory or business consequences, and internal fraud. Analyzing functions within each business unit, operational-risk leaders can then identify those that present the greatest inherent risk exposure. The next step is to prioritize the “failure modes” behind the risks, including malicious intent (traditional conduct risk), inadequate respect for rules, lack of competence or capacity, and the attrition of critical employees. The prioritized framework can be visualized in a heat map (Exhibit 4).

The heat map provides risk managers with the basis for partnering with the first line to develop a set of intervention programs tailored to each high-risk group. The effort includes monitoring, oversight, role modeling, and tone setting from the top. Additionally, training, consequence management, a modified incentive structure, and contingency planning for critical employees are indispensable tools for targeting the sources of exposure and appropriate first-line interventions.

A brighter future

Through the four-part transformation we have described, operational-risk functions can proceed to deepen their partnership with the business, joining with executives to derisk underlying processes and infrastructure. Historically, operational-risk management has focused on reporting risk issues, often in specialized forums removed from day-to-day assessment. Many organizations have thus viewed operational-risk activities as a regulatory necessity and of little business value. The function is accustomed to react to business priorities rather than involve itself in business decision making.

To be effective, operational-risk management needs to change these assumptions. When equipped with objective data and measurement, the function well understands the true level of risk. It is therefore in a unique position to see nonfinancial risks and vulnerabilities across the organization, and it can best prioritize areas for intervention. Together with the business lines, operational-risk management can identify and shape needed investments and initiatives. This would include efforts to digitize operations to remove manual errors, changes in the technology infrastructure, and decisions on product design and business practices. By helping the business meet its objectives while reducing risks of large-scale exposure, operational-risk management will become a creator of tangible value.

The relationship between operational-risk management and the business can also integrate operational-risk reporting and executive and board reporting—including straight-through processing rates, incidents detected, key risk indicators, and insights from complaints and customer calls.

Progress will require time, investment, and management attention, but the transformation of operational-risk management offers institutions compelling opportunities to reduce operational risk while enhancing business value, security, and resilience.

Joseba Eceiza is a partner in McKinsey’s Madrid office; Ida Kristensen and Dmitry Krivin are both partners in the New York office, where Hamid Samandari is a senior partner; and Olivia White is a partner in the San Francisco office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Transforming risk efficiency and effectiveness

Financial crime and fraud in the age of cybersecurity

Insider threat: The human element of cyberrisk

Boeing 737 MAX: An Operational Risk Case Study

- Rex Chatterjee

- October 12, 2019

- Type: Case Study

- Tags: aviation , internal comms , manufacturing , operational risk , regulation

In August 2011, Boeing Commercial Airplanes, a subsidiary of Boeing, announced the launched of its new 737 MAX aircraft as the fourth generation of the 737 line. Initial deliveries of the aircraft took place in May of 2017, and the plane entered commercial service shortly thereafter. Among the first passenger carriers to run the 737 MAX commercially were Lion Air, of Indonesia, and Norwegian Air, of Norway. Within a year of its launch, 130 737 MAX aircraft were delivered to 28 Boeing customers, and in total 387 aircraft were eventually delivered.

On 29 October, 2018, a Boeing 737 MAX aircraft operated by Lion Air crashed thirteen minutes after takeoff, killing all 189 aboard. The incident was widely reported by various media outlets at the time. Initial reports targeted a malfunctioning flight-control system which had to be disabled in order for the aircraft to function properly. Responding to the incident, Boeing issued guidance on its operational manual to advise airline pilots regarding procedures for handling so-called erroneous cockpit readings.

On 10 March 2019, a Boeing 737 MAX aircraft operated by Ethiopian Airlines crashed six minutes after takeoff, killing all 157 aboard. Like the Lion Air incident from the year prior, the Ethiopian Airlines crash was widely reported . Coverage reported that the incident was similar to the Lion Air incident .

Though initial investigations into the incidents could draw no official conclusions regarding Boeing’s aircraft or systems, findings pointed to Boeing’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (“MCAS”) as the likely culprit. The system, which Boeing did not disclose its 737 MAX pilot manual or in its supplementary directive after the Lion Air crash, was allegedly commanding the plane’s flight systems to repeatedly dive, based on erroneous systems data.

Between 11 and 16 March 2019, aviation regulators in countries across the world–including the US, Canada, China, Brazil, India, and others–issued grounding orders for all Boeing 737 MAX aircraft.

Since the grounding of the 737 MAX, investigations into the two crashes and issues with the aircraft have increasingly focused on Boeing’s deployment of MCAS as the primary culprit. Assessments and testing from a variety of sources within multiple investigations have raised issues with the way in which Boeing designed, developed and deployed MCAS, as well as its lack of training and education of pilots and crews on the system’s existence within aircraft, when it would engage, and what to do in case of its malfunction.

On 4 April 2019, Boeing publicly acknowledged that MCAS played a role in both the Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines crashes of the 737 MAX.

On 18 October 2019, multiple news outlets reported that in 2016, prior to the safety certification and release of the 737 MAX, Boeing’s chief technical pilot for the 737 program had warned a colleague about MCAS, specifically pointing to issues unearthed in post-crash investigations. While, in the wake of the crashes, Boeing officials had maintained that MCAS was not designed to activate within the “normal flight envelope” of the 737 MAX and therefore its exclusion from the standard operating manual for the aircraft was warranted, the 2016 internal messages specifically highlighted that MCAS was erroneously engaging itself. The messages go on to indicate that, in 2016 or prior, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) may have been supplied with inaccurate information regarding MCAS. Nevertheless, in 2017, the very same Boeing pilot, again communicating the FAA, requested that all mentions of MCAS be removed from the plane’s operating manual because its operation was outside of the plane’s normal envelope. Going further, the Boeing pilot proceeded to engage in inappropriate discourse with the FAA regulator on the subject of obtaining regulatory clearances from other regulators for the 737 MAX.

Boeing turned over documents related to these communications to regulators and to Congress on 17 and 18 October 2019, allegedly months after first discovering them.

Upon receipt and review of the documents, members of Congress made public statements about what they deemed to be a pattern of troubling conduct by Boeing.

Gaps In Risk Management

Independent Escalation Channels – Boeing’s development team for the 737 MAX had knowledge of the issues with the MCAS. However, it is unclear whether any reporting mechanism existed for members of the team (e.g., engineers, test pilots, etc.) to report such issues to oversight resources outside of the 737 MAX’s direct value chain (i.e., officials and / or at Boeing whose success was not tied directly and exclusively to the marketing and sale of 737 MAX aircraft). While knowledge of the ultimately disastrous MCAS failures was present within Boeing long before the first 737 MAX was delivered to a customer, it was contained in isolated pockets, hidden from the view of senior management at the corporate level whose success is tied to the overall health of Boeing as a company. While some concerned members of the 737 MAX development staff may have wanted to communicate their concerns upwards, and while senior management may have wished to hear their concerns, the communication channels simply did not exist. Instead of reporting concerns to a unit or personnel with proper oversight authority, engineers at Boeing were instructed to take their concerns to business unit managers, as reported by the New York Times . However, with their success tied directly to sales of the 737 MAX, business unit managers had strong incentive suppress the identification of safety risks and prevent escalation of same to members of senior management. In the wake of the 737 MAX situation, Boeing has indicated that it has adopted clearer escalation channels from engineers to neutral oversight personnel, including the company’s senior management.

Independent Safety Oversight – Boeing lacked an independent internal organization charged with ensuring product safety. At a firm of the size of Boeing, producing products (i.e., aircraft) which have the potential to be deadly in the event of failure, an independent unit should exist as a check on commercial business units such as development, manufacturing, marketing and sales. The success of such a unit should not depend at all on sales of products, but rather on the safety of those products at time of sale and beyond. In the wake of the 737 MAX situation, Boeing has announced the creation of such a group within the company.

Employee Communications Monitoring – It is unclear whether Boeing had a function in place to monitor employee communications. As with all public companies, however, it should. Monitoring of employee communications over company-provided systems (such as e-mail, instant messenger, SMS on company-provided phones, etc.), coupled with a general policy and enforcement program that all company business be conducted solely over those company-provided, and not personal, communication systems, is a crucial arm of risk management in an era in which employee communications are a major driver of risk. Near real-time monitoring of employee communications by a unit of Boeing’s compliance group would have alerted senior management to ground-level issues with MCAS in parallel to–and as a backstop to–internal reporting and escalation of the issue from engineering or other staff.

Regulatory Affairs Oversight – While a debate rages on as to whether the FAA has fallen victim to so-called “regulatory capture” by firms such as Boeing, it is nonetheless crucial for the successful, comprehensive management of risk that all communications by a company’s personnel with regulators be not only monitored, but centralized and streamlined through a single source, such as an internal unit overseeing regulatory affairs. In instances such as this, where the specter of impropriety looms large over conduct by Boeing employees and, possibly, the FAA, it is essential that companies are able to manage their official positions on issues facing regulators and are furthermore able to deliver consistent messaging from all personnel involved. While Boeing, in this case, may be able to blame one or more rogue actors for the impropriety with respect to certain FAA-related issues, the company would do itself no favors in the eyes of its regulators, world governments, its customers, its investors and the general public by claiming to have little power to govern the conduct of its employees. Additionally, the FAA’s approval of the 737 MAX has not served as a significant line of defense against Boeing’s liability for its aircraft’s failures, owing partly to the relationship its staff (such as the chief technical pilot) enjoyed with members of regulatory staff. The surfacing of inappropriate communications between members of Boeing and regulator staff has only stoked the fire of governmental concern over Boeing and the regulatory framework meant to govern its conduct.

Costs & Impacts

Financial – Boeing has experienced catastrophic financial losses in the wake of the evolving 737 MAX situation, having posted a company record loss of $2.9 billion USD for Q2 2019. Its market capitalization, as of August 2019, has fallen by $62 billion USD, on the back of a 25% erosion in share price. Overall, the halt of sales and impending cancellation of orders may cost Boeing roughly $600 billion USD .

Business Position – Boeing has seen fit to postpone development of at least one critical project (the Boeing New Midsize Airplane) and is reportedly considering staff reductions as of Q3 2019. Following the grounding of the 737 MAX, Boeing has suspended all deliveries of the aircraft to customers and slowed its production schedule (financial impacts of which are noted above).

Brand Equity – While multiple crashes and a global grounding of the 737 MAX fleet may have been sufficient to critically damage the public’s trust in Boeing, later evidence pointing out that the company knew of the issues giving rise to the crashes and buried them only further stokes the fire. Numerous polls have indicated that the public has lost its trust in the 737 MAX, and with recent evidence coming to light about Boeing’s practices, the same may well be said of public trust in Boeing itself as well. Serving the needs of the general public, airline customers of Boeing will face increased scrutiny and pressure on their dealings with the company, impacting Boeing’s ability to sell its products across the board.

Criminal Investigation – At the time of this writing, Boeing and certain individual employees may face criminal prosecution in connection with the 737 MAX crash incidents.

Civil Litigation – Boeing now finds itself the target of civil litigation from a variety of sources, including pilot groups seeking compensation for lost wages, crash victims’ families seeking compensation for wrongful deaths (potentially including punitive damages), and others. At the time of this writing, the total outcome of the global 737 MAX litigation is yet to be known.

Regulatory Pressure – Boeing will likely face significantly increased regulatory scrutiny across the globe as trust in the company and its practices has been eroded by the 737 MAX crashes and their aftermath.

Key Takeaways

1. Companies must designate certain personnel or units as managers and overseers of risk, with their success directly tied to safety and effective risk mitigation instead of sales and other commercial metrics. Companies cannot rely on commercial units (e.g., sales, marketing, etc.) to manage risk. With the success or failure of these units being tied directly to the sales performance of their managed products, these units are inherently disincentivized from reporting issues which may imperil sales and are not likely to serve as effective mitigants of risk.

2. Companies must ensure clear and independent lines of communication between ground level staff and those personnel and / or units designed to manage risk. Staff members in product development, sales, marketing and a variety of other functional groups must be able to communicate clearly and confidentially with risk managers in order to effectively relay concerns without fear of reprisals or dismissal.

3. Companies must institute policies, procedures and technological capabilities in order to be able to effectively monitor employee communications in real-time or near-real-time. Failure to monitor employee communications robs companies of their opportunities to manage risks borne out of the behavior of rogue actors. Assigning blame for corporate malfeasance to rogue internal actors ex post facto is not an effective strategy. Instead, companies must own the risk that their personnel may act against the best interests of the firm and effectively manage incidents as they are occurring.

4. Companies with regulatory exposure must institute policies, procedures and top-down governance over corporate communications with regulators. While in most cases, a regulatory communications function serves to manage regulatory relations and minimize the risk of incurring penalties or enforcement actions, in some cases, its purpose may be to detect regulatory capture and therefore ineffective regulation. While ineffective regulation may not seem, at first, to be a risk for regulated businesses, for businesses without strong regulatory affairs units, it may present itself as an invitation for corporate misconduct, as evidenced above.

Companies should be proactive about risk management and conduct broad risk assessments on a regular basis. Such assessments should monitor for threats across strategic and tactical vectors. From broad-based standpoints such as ensuring clear and independent reporting lines, to granular measures such as monitoring high-risk employee communications, risk management efforts must be comprehensive. Finally, it is vital that key stakeholders up and down a company’s chain of command “buy in” to the importance of risk management and participate in the process in a transparent and cooperative manner. It is incumbent upon company leadership to ensure that a “culture of risk awareness and management” is present at all levels of the organization.

Titan Grey stands ready to assist on business risk management matters of the nature discussed in this Titan Grey Thought Leadership piece. Please inquire via e-mail to [email protected] .

Titan Grey Thought Leadership is presented subject to certain disclaimers, accessible here .

Share With Your Network

Other Thought Leadership Of Interest

The FTX Files: A Primer On The Chapter 11 Case

The FTX Files: A primer on the chapter 11 case prepared & updated by Titan Grey. Click through for more & follow our socials for the latest.

Recent Thought Leadership

Omicron Variant: Practical Risk Management Approaches

Employee Physical Security And Crime Prevention

COVID-19 Risk Management For Business

Let's Connect.

Global risk & crisis management.

- +1 800 551 9323

- [email protected]

- titangrey.com

Thought Leadership

Copyright Ⓒ 2024 Titan Grey, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

The Latest In Business Risk Management

If you're reading business headlines and asking yourself "how could this possibly happen?," our Thought Leadership is for you. Through short case studies and longer-form deep dives, we break down current issues in business risk and offer responsive strategies for the future.

- Business & Money

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -37% $46.09 $ 46 . 09 FREE delivery Tuesday, May 28 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: RAINBOW TRADE

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Acceptable .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $16.75 $ 16 . 75 $3.99 delivery May 28 - 29 Ships from: sfbay_books Sold by: sfbay_books

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Operational Risk Management: A Case Study Approach to Effective Planning and Response 1st Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 9780470256985

- ISBN-13 978-0470256985

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Wiley

- Publication date April 4, 2008

- Language English

- Dimensions 6.3 x 1.14 x 9.43 inches

- Print length 288 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

From the inside flap.

In the world we live in today, disasters occur on a daily basis. Could they have been prevented from occurring? If emergency response had been more effective, how much less destruction might they have caused? Will similar disasters happen again? Operational Risk Management: A Case Study Approach to Effective Planning and Response examines the safety and security of an organization's people, facilities, and assets, as well as the communities in which they are located, from exposure to natural disasters, man-made accidents, and terrorist acts that have occurred worldwide, revealing the underlying causes of these catastrophic events.

Through the use of carefully selected case studies in a variety of scenarios across many different industries and environments, both in the United States and abroad, author and industry expert Mark Abkowitz uses historical events to demonstrate how operational risk management practices―or the lack of them―influence event likelihood and outcomes across all hazard domains. Each case contains a narrative, followed by a discussion that draws conclusions as to why things went wrong, as well as what, if anything, has been done to prevent such an occurrence from happening again. These include:

Hyatt Regency Walkway Collapse

Nightmare in Bhopal

Meltdown at Chernobyl

Attack on the USS Cole

September 11 – The World Trade Center

London Transit Bombings

Eruption of Mount St. Helens

Hurricane Katrina

In reviewing painful experiences of the past, it is clear that protecting our future cannot be left to chance. Operational Risk Management: A Case Study Approach to Effective Planning and Response not only looks at the risk factors present in previous disasters but also at the valuable lessons learned. These factors and lessons are used to forge a path forward that risk managers can use to ensure that their organizations have strong safety and security plans in place–and are ready to respond when necessary.

From the Back Cover

Operational Risk Management offers peace of mind to business and government leaders who want their organizations to be ready for any contingency, no matter how extreme. This invaluable book is designed to be used as both a preparatory resource for when times are good and an emergency reference when times are bad. Author Mark Abkowitz gets managers up to speed on what they should be prepared to deal with and offers real solutions for putting those business continuity plans in place. From natural and man-made disasters to terrorist attacks, Operational Risk Management is destined to become every risk manager's ultimate weapon to help their organization survive ― no matter what.

Praise for Operational Risk Management

"Mark Abkowitz has produced an excellent and wide-ranging collection of case studies that illustrate the role that risk factors play in determining the success or failure of anything designed. In Operational Risk Management, he not only analyzes the causes of failure but also indicates how proactive risk management can lead to success. This is a very well-written and instructive book." ―Henry Petroski, Aleksandar S. Vesic Professor of Civil Engineering and Professor of History, Duke University

"As one of the nation's largest domestic marine transport companies, moving hazardous cargo daily on our nation's waterways, we relentlessly pursue risk reduction through the lessons provided by real-world experiences. Mark Abkowitz's insightful analysis of recent disasters and his identification of risk factors common to them will help anyone concerned with incident prevention and consequence mitigation." ―Dr. Craig E. Philip, President and Chief Executive Officer, Ingram Barge Company

"A wise man once said, 'The mistakes we make are a result of the history we haven't read.' History is the treasure of evidence, whether it is about the risks we face as human beings or the mysteries of the universe. This book adds to the treasure of evidence and succinctly articulates, with distinction and clarity, the factors and actions most important to managing the risks we humans face." ―B. John Garrick, PhD, PE

"Dr. Abkowitz's masterful blend of great storytelling with astute professional risk assessment provides a fabulous tool for Joe Q. Public, public policy experts, and industrial risk managers to use together to make real headway on more intelligent risk management for all of us." ―Jim Vines, Environmental, Health & Safety Specialist, King & Spalding

"Through his case studies and analysis, Mark Abkowitz identifies key factors critical to understanding how we move towards more resilient communities. His focus on a more inclusive, all-hazards approach begins to point the way. A very useful collection indeed." ―Michael T. Lesnick, PhD, cofounder and Senior Partner, Meridian Institute

About the Author

Excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., operational risk management, john wiley & sons, chapter one.

Excerpted from Operational Risk Management by Mark D. Abkowitz Copyright © 2008 by Mark D. Abkowitz . Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

Product details

- ASIN : 0470256982

- Publisher : Wiley; 1st edition (April 4, 2008)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 288 pages

- ISBN-10 : 9780470256985

- ISBN-13 : 978-0470256985

- Item Weight : 1.14 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.3 x 1.14 x 9.43 inches

- #244 in Risk Management (Books)

- #477 in Atmospheric Sciences (Books)

- #608 in Disaster Relief (Books)

About the author

Mark david abkowitz.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Important Notices

- GBI Secure Login

- Program and Exams

- Fees and Payments

- Our FRM Certified Professionals

- Study Materials

- Exam Logistics

- Exam Policies

- Risk Career Blog

- Register for FRM Exam

- Path to Certificate

- Climate Resource Center

- Register for SCR Exam

- Foundations of Financial Risk (FFR)

- Financial Risk and Regulation (FRR)

- About Membership

- Exclusive Offers

- Risk Intelligence

- Board of Trustees

- GARP Benchmarking Initiative (GBI)

- GARP Risk Institute (GRI)

- Buy Side Risk Managers Forum

- Academic Partners

- Careers at GARP

- Culture & Governance

- Sustainability & Climate

- Operational

- Comment Letters

- White Papers

- Islamic Finance Book

The Best Tool for Operational Risk Management

Properly-executed case studies can help financial institutions ward off operational risk disasters. what should a good operational risk case study look like, and what lessons can we learn from the samsung securities "fat finger" incident.

Friday, February 22, 2019

By Marco Folpmers

If you want to learn from the operational risk mistakes of others and prevent incidents that could severely impact your firm's reputation and bottom line, then case studies are your best bet. An effective operational risk case study asks the right questions, details the consequences of the incident and offers suggestions for what could have been done to avert it.

When we think of operational risk, fraud and information technology failures are likely among the first things that come to mind. But simple human errors are also part of the equation. Last year's “ Fat Finger” incident at Samsung Securities offers an excellent example of what a case study can teach us about human errors, poor oversight and system deficiencies.

On April 6, 2018, Samsung Securities, one of the largest brokerages in South Korea, accidentally issued $105 billion worth of shares to its employees. Under the company's stock ownership plan, it was supposed to pay dividends worth 2.8 billion won ($2.6 million) to about 2,000 employees. But a Samsung Securities employee mistakenly entered “shares” instead of “won” (South Korea's currency) into the computer system, resulting in the issuance of 2.8 billion shares - more than 30 times the company's number of outstanding shares.

Although Samsung Securities discovered the incident 37 minutes after it occurred and notified the employees affected that the shares had been erroneously granted, some of them sold the stock , despite warnings from the company.

What went wrong at Samsung Securities? Plenty. Let's examine a case study model to break down the incident, its consequences and the lessons learned.

The Bow-Tie Model

Good case studies can either be outsourced or written internally, based on public resources. One of the most popular and effective approaches to operational risk case studies is the bow-tie model, which (1) explains the underlying causes, motives, opportunities and means that are at the basis of the incident; (2) thoroughly describes the incident itself; and (3) breaks down the consequences, including direct and indirect loss amounts.

The bow-tie model can certainly help us understand what happened at Samsung Securities, and can also yield ideas on preventing similar incidents from unfolding in the future. The "fat finger" incident happened in just a fraction of a second - an errant keystroke resulting in the issuance of an extremely costly and grossly erroneous dividend. The underlying causes include poor supervision, ineffective internal controls and inadequate regulatory monitoring.

The model also yields a series of probing questions about the incident: Why was one person allowed to initiate and authorize this transaction? Why did there appear to be no segregation of duties? Why didn't the IT system block the issuance and distribution of an extraordinary number of shares? And why wasn't the naked short-selling immediately prevented?

The consequences of this blunder were manifold. Analysts criticized the firm for having neither a filtering system for preventing human errors nor a warning system that could have stopped the issuance of more shares than actually existed.

The Financial Supervisory Service, South Korea's financial watchdog, found that 21 employees of Samsung Securities had either sold or attempted to sell the mistakenly-issued shares. All 21 lost their jobs, and several are facing criminal charges .

The National Pension Service, South Korea's biggest pension fund, stopped using Samsung Securities to trade stock almost immediately after the incident. Roughly seven weeks later, South Korean prosecutors raided the broker's head office, which precipitated the partial suspension of its brokerage services and the resignation of its CEO .

Unique Challenges

Operational risk is different from - and I think more difficult to manage than - credit risk and market risk. One reason is that it can arise anywhere in the organization - from commercial units, to brick-and-mortar bank shops, to support functions and IT systems.

Its impact, moreover, is difficult to quantify. Keep in mind that the advanced modeling approach to measuring operational risk has been eliminated, while the new benchmark - the standardized measurement approach - has drawbacks of its own.

While banks use databases to collect and store data on operational risk incidents, it is difficult, in practice, to extrapolate from these past occurrences - particularly with respect to quantifying losses.

Indeed, a bank's own incident database provides only a very limited view of its current operational risk exposure. The incident data that is collected is typically the result of a stochastic process, and therefore not necessarily commensurate with a firm's operational risk exposure to specific event types.

The operational risk case study is the go-to methodology for overcoming this randomness bias. It expands the experience from learning from one's own errors to learning from errors made by others. While reading detailed accounts of incidents that happened elsewhere, operational risk managers may very well ask themselves questions that will help them avoid similar mistakes: Could this happen at our firm? If it does, what would I do? And what specific steps can our organization take to prevent this from happening?

Parting Thoughts

Case studies are among the biggest assets in the operational risk manager's toolkit. When we analyze the case study of the Samsung Securities “fat finger” incident, important questions are triggered. Why, for example, weren't checks and balances in place to prevent this stock pay-out from happening? Why wasn't the employee alerted that a payout of 1,000 shares per share is extraordinary? And why didn't IT controls prevent the illegal naked short-selling?

A more fundamental question relates to the irresponsible behavior of the 21 employees who attempted, illegally, to benefit from the “fat finger” blunder.

How would your employees behave under a similar scenario? Case studies provide the answers every firm needs to avoid being the next poster child for operational risk disaster.

Marco Folpmers (FRM) is a professor of financial risk management at Tilburg University. He is also a managing director at Accenture Finance and Risk.

Risk Management Specialist vs. Generalist: Which Is Right for You? Jun 9, 2023

5 Ways to Improve Model Risk Management Nov 17, 2023

The Unconventional Skills Chief Risk Officers are Now Seeking Jul 17, 2020

Operational Risk Capital Proposal: Time to Hit the Pause Button Nov 17, 2023

The Road to Better Model Risk Management Oct 27, 2023

Advertisement

- Financial Risk Manager

- Sustainability and Climate Risk

We are a not-for-profit organization and the leading globally recognized membership association for risk managers.

• Bylaws • Code of Conduct • Privacy Notice • Terms of Use © 2024 Global Association of Risk Professionals

ConnectedGRC

Drive a Connected GRC Program for Improved Agility, Performance, and Resilience

BusinessGRC

Power Business Performance and Resilience

- Enterprise Risk

- Operational Risk

- Operational Resilience

- Business Continuity

- Observation

- Regulatory Change

- Regulatory Engagement

- Case and Incident

- Compliance Advisory

- Internal Audit

- SOX Compliance

- Third-Party Risk

Manage IT and Cyber Risk Proactively

- IT & Cyber Risk

- IT & Cyber Compliance

- IT & Cyber Policy

- IT Vendor Risk

Enable Growth with Purpose

AI-based Knowledge Centric GRC

- Integration

- Marketplace

- Developer Portal

Latest Release

Explore the right questions to ask before buying a Cyber Governance, Risk & Compliance solution.

Discover ConnectedGRC Solutions for Enterprise and Operational Resilience

- Enterprise GRC

- Integrated Risk Management

- CyberSecurity

- Corporate Compliance

- Supplier Risk and Performance

- Digital Risk

- IT and Security Compliance, Policy and Risk

- UK SOX Compliance

- Privacy Compliance

- IDW PS 340 n.F.

- Banking and Financial Services

- Life Sciences

Learn about the EU’s Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) and how you can prepare for it.

Explore What Makes MetricStream the Right Choice for Our Customers

Customer Stories

- GRC Journey

- Training & Certification

- Compliance Online

Robert Taylor from LSEG shares his experience on implementing an integrated GRC program with MetricStream

Discover How Our Collaborative Partnerships Drive Innovation and Success

- Our Partners

- Want to become a Partner?

Watch Lucia Roncakova from Deloitte Central Europe, speak on how the partnership with MetricStream provides collaborative GRC solutions

Find Everything You Need to Build Your GRC Journey and Thrive on Risk

Featured Resources

- Analyst Reports

- Case Studies

- Infographics

- Product Overviews

- Solution Briefs

- Whitepapers

Download this report to explore why cyber risk is rising in significance as a business risk.

Learn about our mission, vision, and core values

Gurjeev Sanghera from Shell explains why they chose MetricStream to advance on the GRC journey

Implementing a Federated Approach to Operational Risk Management

The Client: A multi-billion dollar financial services provider with operations across the world with millions of customers.

Being a complex organization with multiple business units and operations spread across geographies, the company found it increasingly complex to measure and monitor risks. Although risk assessments were being performed regularly in every business unit, complexities arose when it came to consolidating the results. Each business unit used different risk terminologies and languages, which made it challenging to get a holistic picture of risk at the enterprise level. After analyzing the situation, the company chose to implement a federated approach to Operational Risk Management (ORM), supported and enabled by a workflow-based ORM solution. The approach was designed such that each business unit would be able to conduct their own independent operational risk assessments, while at the same time, the results would be automatically aggregated and rolled up so that the board and top management would gain a single, comprehensive view of risk across the enterprise

Towards a New ORM Strategy

The company's federated ORM project was kick-started in early 2012. Stakeholders from different groups such as Compliance, Audit, Vendor Governance, and Risk Management came together to discuss what to do, how best to go about it, and what technology solution to implement. Eventually, the company developed a comprehensive ORM strategy, and implemented a solution that focused on strengthening existing ORM processes, standardizing the risk language, and gaining an integrated risk view. Below are the key elements of the company's enhanced ORM program:

Risk-Control Self-Assessments (RCSAs)

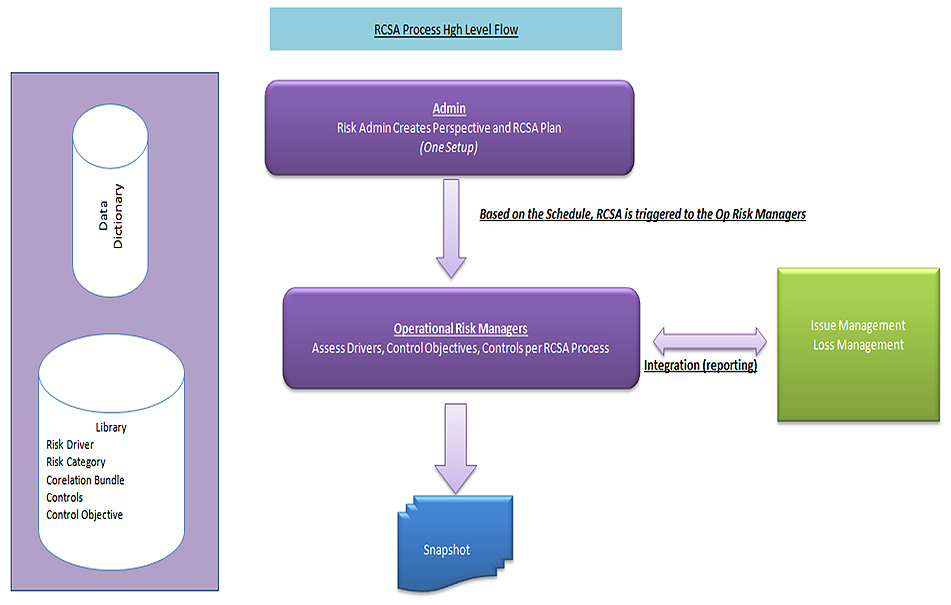

At a broad level, the company's operational risk assessment process begins with the risk administrator preparing an RCSA plan and schedule, based on which the operational risk managers assess their business unit's risks and controls. Each business unit has the flexibility to implement their own approach to RCSAs such that it is relevant to the risks they face. This kind of flexibility is important because a risk such as credit risk which is critical to one business unit may not be relevant to the other. But whatever the approach to RCSAs, all business units use the same risk language and nomenclature to describe operational risk drivers, correlation bundles 1 , controls, control objectives, and reliance maturity 2 . All these risk terms are clearly defined and stored in a centralized risk data dictionary that can be accessed by operational risk managers across the globe while preparing their risk reports.

Risk Control Self Assessment - High Level Flow

Given that risk events can be unpredictable as well as subject to constant change, the company enables continuous and recurring risk assessments. They also conduct process RCSAs which focus on ad hoc but granular evaluations of a specific risfunction

Business Environment Analysis (BEA)

Several internal and external factors such as a change in policy, or a restructuring of the management team have a direct impact on risk management at various levels of the organization. Every time such a change occurs, a BEA event workflow is triggered. This allows risk administrators to route the BEA to concerned risk managers in their team who, in turn, can either accept or reject the BEA depending on how it impacts their organization or their risk management processes.

Risk profile tracking

Each operational risk manager has access to powerful graphical dashboards which provide real-time insights into all risks, issues, losses, KRIs, BEAs, and other critical information in the business unit. Users can view risks by category and organizational tier, and identify if there needs to be a re-assessment of a risk driver, a loss scenario, inherent risk, controls, or any other elements. This top-level risk view helps risk managers focus their attention on the most critical risk areas. Advanced drill-down capabilities help the risk managers view the data at any level of granularity, and proactively identify and analyze risk triggers (e.g. new issues, losses, BEA change events, breach of KRI thresholds). At regular intervals, an informal risk snapshot is taken of all RCSAs in a business unit. The result is a “freeze-frame†picture of risks which enables operational risk managers to identify and analyze risk trends effectively. A more formal risk snapshot is taken every quarter.

Risk landing page

Similar to the ORM dashboard is a landing page in the ORM solution which provides operational risk managers with a complete overview of their business unit's risk profile. Any risk manager who logs into the system can quickly and easily understand the risk profile without having to click on several different links and tabs. At a broad level, the landing page contains top-level risk categories, events, number of controls, number of issues, number of KRIs, number of loss events, and other such critical data that can be quickly navigated through. If there is a change made to the data (e.g. a new issue registered in the system), it is automatically mapped to the relevant risk categories (e.g. credit risk issue, market risk issue). Since risk managers are located in different geographies, and may therefore speak different languages, the landing page provides multi-lingual support, in addition to being intuitive and easy-to-use.

Risk measurement

Most organizations measure their inherent risk in terms of impact and likelihood, expressed as a 2x2 framework. But since the company deals specifically with finance, they opted to express risk impact in terms of other dimensions such as currency i.e. USD, Euro, etc. A specific group in the organization uploads the risk data based on changing currency rates. So when the risk report is shown to the Board, they can view the currency conversion rate. The currency is also defined based on the user profile. For instance, a user in Europe will see the risk impact expressed in terms of Euros while his or her counterpart in the U.S. will see it in USD. Risk can also be measured in terms of probability i.e. the likelihood that a risk scenario paired with the defined inherent risk, will occur within a year. Users even have the ability to determine the inverse actuarial risk probability. Another unique way of measuring risk is in terms of velocity. Risk velocity adds a third dimension to the traditional model of risk impact and likelihood, and refers to the speed of occurrence of a particular risk impacting the organization. In other words, it introduces the “time†factor to risk management. So, by measuring risk velocity, the company can determine how quickly a risk might occur, how fast they will be impacted by it, and how much time they will have to prepare and react.

Control objectives and ratings

In its risk data dictionary, the company maintains a comprehensive list of control objectives i.e. a description of the types of controls for a specific risk. There are also control objective ratings which tell the organization whether or not all the required controls are in place, and how important they are to the overall risk category. A strong control objective rating indicates that the needed controls are in place, while a bad control objective rating indicates that some controls are missing for a particular risk category. Control ratings, on the other hand, indicate the effectiveness of an individual control. By combining these control ratings with overall control objective ratings, the organization gets a complete picture of the adequacy of the control environment for a particular risk category.

Issue management

All RCSA, loss management, and BEA processes eventually link to issue management in a closed-loop approach. In fact, there are many other processes and functions such as Compliance and Audits which also integrate with issue management. If each function uses different terminologies for these issues and the associated risks, then reporting becomes complicated. To avoid this challenge, all functions refer to the same risk data dictionary for enterprise-wide issue reporting. And if any of the issues pose an operational risk, the ORM group gets notified immediately.

The Enabling Role of Technology

The company implemented MetricStream ORM Solution to support and enable their risk management strategy. The solution provides the following core capabilities:

- A single, centralized system for managing and assessing risks across the enterprise

- Integration with multiple enterprise systems to automatically gather and aggregate a variety of risk data, including KRIs, KPIs, issues, BEAs, and internal and external losses

- Powerful dashboards and reports to help risk managers gain better risk visibility and thereby better risk control.

- A centralized data dictionary/ risk library with common definitions of risk categories, risk drivers, correlation bundles, controls, control objectives, and other risk terms

- Multi-lingual support so that operational risk managers have the freedom to select their choice of language for various field values in a form, rating guides, and reporting

- Flexibility to seamlessly adapt to organizational changes such as the introduction of new risk policies or regulations

Lessons Learned

- Look at ORM as an opportunity to strengthen the business, not just as a function that has to be fulfilled

- Track your risk profile consistently to ensure that all risks stay within the defined risk appetite

- When standardizing your risk language, make sure that it is reflected and integrated in all risk systems

- Have an honest dialogue about what your ORM technology can and cannot do – push the limits but be clear about them

- If you are using an ORM platform, upgrade it regularly to enhance its capabilities, and ensure holistic bug fixes

- Single view of enterprise risk Tools such as executive risk dashboards and a centralized risk landing page offer a quick, high-level overview of risk and control data which can then be drilled down to analyze details. This comprehensive picture of risk enables operational risk managers to proactively identify and address opportunities, as well as areas of concern.

- Standardization of risk language The risk data dictionary has helped the company implement a common risk language across business units. Thus when the management team at the company headquarters looks at the consolidated RCSA results, they get a clear and comprehensive understanding of the enterprise risk profile. This, in turn, helps them make better risk-informed strategic decisions.

- Greater understanding of risk The company can measure and analyze their risk not only in terms of impact and likelihood, but also parameters such as currency and velocity. This helps them understand and prioritize their risks better, and determine which ones need to be mitigated immediately, and which ones can be transformed into opportunities.

- More systematic and closed-loop risk processes The company has been able to streamline end-to-end risk processes, right from risk assessment, to risk tracking, risk reporting, control assessments, loss management, KRI monitoring, and issue management. This structured approach helps minimize redundancies and duplicate effort, and improves the cost-efficiency of risk management .

Subscribe for Latest Updates

Ready to get started?

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Operational Risk Management: A Case Study Of An Indian Commercial Bank

Related Papers

N'Guessan Arnaud Tozan Bi

Carlos José Urzola

Journal Of Archaeology and archaeometry

Michael Imhof