What this handout is about

This handout will define what an argument is and explain why you need one in most of your academic essays.

Arguments are everywhere

You may be surprised to hear that the word “argument” does not have to be written anywhere in your assignment for it to be an important part of your task. In fact, making an argument—expressing a point of view on a subject and supporting it with evidence—is often the aim of academic writing. Your instructors may assume that you know this and thus may not explain the importance of arguments in class.

Most material you learn in college is or has been debated by someone, somewhere, at some time. Even when the material you read or hear is presented as a simple fact, it may actually be one person’s interpretation of a set of information. Instructors may call on you to examine that interpretation and defend it, refute it, or offer some new view of your own. In writing assignments, you will almost always need to do more than just summarize information that you have gathered or regurgitate facts that have been discussed in class. You will need to develop a point of view on or interpretation of that material and provide evidence for your position.

Consider an example. For nearly 2000 years, educated people in many Western cultures believed that bloodletting—deliberately causing a sick person to lose blood—was the most effective treatment for a variety of illnesses. The claim that bloodletting is beneficial to human health was not widely questioned until the 1800s, and some physicians continued to recommend bloodletting as late as the 1920s. Medical practices have now changed because some people began to doubt the effectiveness of bloodletting; these people argued against it and provided convincing evidence. Human knowledge grows out of such differences of opinion, and scholars like your instructors spend their lives engaged in debate over what claims may be counted as accurate in their fields. In their courses, they want you to engage in similar kinds of critical thinking and debate.

Argumentation is not just what your instructors do. We all use argumentation on a daily basis, and you probably already have some skill at crafting an argument. The more you improve your skills in this area, the better you will be at thinking critically, reasoning, making choices, and weighing evidence.

Making a claim

What is an argument? In academic writing, an argument is usually a main idea, often called a “claim” or “thesis statement,” backed up with evidence that supports the idea. In the majority of college papers, you will need to make some sort of claim and use evidence to support it, and your ability to do this well will separate your papers from those of students who see assignments as mere accumulations of fact and detail. In other words, gone are the happy days of being given a “topic” about which you can write anything. It is time to stake out a position and prove why it is a good position for a thinking person to hold. See our handout on thesis statements .

Claims can be as simple as “Protons are positively charged and electrons are negatively charged,” with evidence such as, “In this experiment, protons and electrons acted in such and such a way.” Claims can also be as complex as “Genre is the most important element to the contract of expectations between filmmaker and audience,” using reasoning and evidence such as, “defying genre expectations can create a complete apocalypse of story form and content, leaving us stranded in a sort of genre-less abyss.” In either case, the rest of your paper will detail the reasoning and evidence that have led you to believe that your position is best.

When beginning to write a paper, ask yourself, “What is my point?” For example, the point of this handout is to help you become a better writer, and we are arguing that an important step in the process of writing effective arguments is understanding the concept of argumentation. If your papers do not have a main point, they cannot be arguing for anything. Asking yourself what your point is can help you avoid a mere “information dump.” Consider this: your instructors probably know a lot more than you do about your subject matter. Why, then, would you want to provide them with material they already know? Instructors are usually looking for two things:

- Proof that you understand the material

- A demonstration of your ability to use or apply the material in ways that go beyond what you have read or heard.

This second part can be done in many ways: you can critique the material, apply it to something else, or even just explain it in a different way. In order to succeed at this second step, though, you must have a particular point to argue.

Arguments in academic writing are usually complex and take time to develop. Your argument will need to be more than a simple or obvious statement such as “Frank Lloyd Wright was a great architect.” Such a statement might capture your initial impressions of Wright as you have studied him in class; however, you need to look deeper and express specifically what caused that “greatness.” Your instructor will probably expect something more complicated, such as “Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture combines elements of European modernism, Asian aesthetic form, and locally found materials to create a unique new style,” or “There are many strong similarities between Wright’s building designs and those of his mother, which suggests that he may have borrowed some of her ideas.” To develop your argument, you would then define your terms and prove your claim with evidence from Wright’s drawings and buildings and those of the other architects you mentioned.

Do not stop with having a point. You have to back up your point with evidence. The strength of your evidence, and your use of it, can make or break your argument. See our handout on evidence . You already have the natural inclination for this type of thinking, if not in an academic setting. Think about how you talked your parents into letting you borrow the family car. Did you present them with lots of instances of your past trustworthiness? Did you make them feel guilty because your friends’ parents all let them drive? Did you whine until they just wanted you to shut up? Did you look up statistics on teen driving and use them to show how you didn’t fit the dangerous-driver profile? These are all types of argumentation, and they exist in academia in similar forms.

Every field has slightly different requirements for acceptable evidence, so familiarize yourself with some arguments from within that field instead of just applying whatever evidence you like best. Pay attention to your textbooks and your instructor’s lectures. What types of argument and evidence are they using? The type of evidence that sways an English instructor may not work to convince a sociology instructor. Find out what counts as proof that something is true in that field. Is it statistics, a logical development of points, something from the object being discussed (art work, text, culture, or atom), the way something works, or some combination of more than one of these things?

Be consistent with your evidence. Unlike negotiating for the use of your parents’ car, a college paper is not the place for an all-out blitz of every type of argument. You can often use more than one type of evidence within a paper, but make sure that within each section you are providing the reader with evidence appropriate to each claim. So, if you start a paragraph or section with a statement like “Putting the student seating area closer to the basketball court will raise player performance,” do not follow with your evidence on how much more money the university could raise by letting more students go to games for free. Information about how fan support raises player morale, which then results in better play, would be a better follow-up. Your next section could offer clear reasons why undergraduates have as much or more right to attend an undergraduate event as wealthy alumni—but this information would not go in the same section as the fan support stuff. You cannot convince a confused person, so keep things tidy and ordered.

Counterargument

One way to strengthen your argument and show that you have a deep understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counterarguments or objections. By considering what someone who disagrees with your position might have to say about your argument, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Recall our discussion of student seating in the Dean Dome. To make the most effective argument possible, you should consider not only what students would say about seating but also what alumni who have paid a lot to get good seats might say.

You can generate counterarguments by asking yourself how someone who disagrees with you might respond to each of the points you’ve made or your position as a whole. If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are arguing, but someone probably has. For example, some people argue that a hotdog is a sandwich. If you are making an argument concerning, for example, the characteristics of an exceptional sandwich, you might want to see what some of these people have to say.

- Talk with a friend or with your teacher. Another person may be able to imagine counterarguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider your conclusion or claim and the premises of your argument and imagine someone who denies each of them. For example, if you argued, “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying, “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and needy.”

Once you have thought up some counterarguments, consider how you will respond to them—will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

When you are summarizing opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to show that you have considered the many sides of the issue. If you simply attack or caricature your opponent (also referred to as presenting a “straw man”), you suggest that your argument is only capable of defeating an extremely weak adversary, which may undermine your argument rather than enhance it.

It is usually better to consider one or two serious counterarguments in some depth, rather than to give a long but superficial list of many different counterarguments and replies.

Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. If considering a counterargument changes your position, you will need to go back and revise your original argument accordingly.

Audience is a very important consideration in argument. Take a look at our handout on audience . A lifetime of dealing with your family members has helped you figure out which arguments work best to persuade each of them. Maybe whining works with one parent, but the other will only accept cold, hard statistics. Your kid brother may listen only to the sound of money in his palm. It’s usually wise to think of your audience in an academic setting as someone who is perfectly smart but who doesn’t necessarily agree with you. You are not just expressing your opinion in an argument (“It’s true because I said so”), and in most cases your audience will know something about the subject at hand—so you will need sturdy proof. At the same time, do not think of your audience as capable of reading your mind. You have to come out and state both your claim and your evidence clearly. Do not assume that because the instructor knows the material, he or she understands what part of it you are using, what you think about it, and why you have taken the position you’ve chosen.

Critical reading

Critical reading is a big part of understanding argument. Although some of the material you read will be very persuasive, do not fall under the spell of the printed word as authority. Very few of your instructors think of the texts they assign as the last word on the subject. Remember that the author of every text has an agenda, something that he or she wants you to believe. This is OK—everything is written from someone’s perspective—but it’s a good thing to be aware of. For more information on objectivity and bias and on reading sources carefully, read our handouts on evaluating print sources and reading to write .

Take notes either in the margins of your source (if you are using a photocopy or your own book) or on a separate sheet as you read. Put away that highlighter! Simply highlighting a text is good for memorizing the main ideas in that text—it does not encourage critical reading. Part of your goal as a reader should be to put the author’s ideas in your own words. Then you can stop thinking of these ideas as facts and start thinking of them as arguments.

When you read, ask yourself questions like “What is the author trying to prove?” and “What is the author assuming I will agree with?” Do you agree with the author? Does the author adequately defend her argument? What kind of proof does she use? Is there something she leaves out that you would put in? Does putting it in hurt her argument? As you get used to reading critically, you will start to see the sometimes hidden agendas of other writers, and you can use this skill to improve your own ability to craft effective arguments.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. FitzGerald. 2016. The Craft of Research , 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ede, Lisa. 2004. Work in Progress: A Guide to Academic Writing and Revising , 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Gage, John T. 2005. The Shape of Reason: Argumentative Writing in College , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Effectively Present and Defend Your Arguments

Written by Argumentful

In our contemporary world, characterized by rapid change and diverse viewpoints, the ability to proficiently articulate and justify our opinions has become increasingly crucial.

Whether it’s in a business meeting, a classroom discussion, or a political debate, the ability to articulate your thoughts and persuade others is a valuable skill.

However, many people struggle with this task and may find themselves feeling frustrated or defeated in these situations.

Consider the following scenario: You’re at a family dinner and the conversation turns to politics. Your uncle begins passionately arguing his point of view, and you find yourself disagreeing. You want to express your own beliefs, but you’re unsure how to do so without coming across as confrontational or aggressive. Sound familiar?

This article aims to provide guidance on how to effectively present and defend your arguments, whether it’s in a casual conversation or a formal debate. Through practical tips and strategies, we’ll explore how to confidently articulate your thoughts, stay focused on the issue at hand, and effectively counter opposing views.

By the end of this article, you will have a toolbox of techniques for presenting and defending your arguments in a clear, concise, and persuasive manner.

So whether you’re debating politics with family or presenting a proposal to your boss, you’ll be better equipped to confidently and effectively make your case.

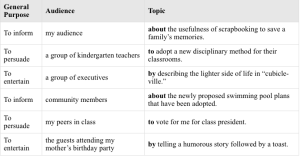

• Understanding the audience and context

• Preparing and structuring your argument

• Presenting your argument

• Defending your argument

• Dealing with emotional reactions

• Conclusion

Understanding the audience and context

One of the most crucial aspects of presenting and defending arguments effectively is understanding the audience and context in which you will be making your case. By taking the time to research and analyse the values, beliefs, and backgrounds of your audience, you can tailor your argument to better resonate with their perspective and increase your chances of success.

To start, consider who your audience is and what their interests and priorities might be.

• Are they experts in your field, or are they laypeople who may not have a deep understanding of the topic?

• Are they part of a specific cultural or social group with their own unique values and beliefs?

By answering these questions, you can begin to build a more accurate picture of who you will be speaking to and how best to communicate with them.

Another important consideration is the context in which you will be presenting your argument.

• Is this a formal debate with strict rules of engagement, or a more casual conversation among friends?

• What is the cultural and social background of the context, and how might that impact the way you frame your argument?

By analysing these factors, you can adjust your language , tone , and approach to better suit the situation and increase your chances of success.

Tips and techniques for researching the audience

When researching your audience and context, consider the following tips and techniques:

- Analyse the values and beliefs of your audience : Take time to understand what your audience cares about and what they believe to be important. By framing your argument in a way that aligns with these values, you can increase your chances of persuading them to see your point of view.

Here are some examples:

- If you are presenting to a group of environmental activists , you might emphasize the environmental impact of your argument and the importance of protecting the planet for future generations.

- If your audience is composed of business executives , you might focus on the financial benefits of your argument, such as cost savings or increased profits.

- If you are presenting to a religious community , you might appeal to their shared values of compassion, kindness, and social justice, and demonstrate how your argument aligns with these beliefs.

- If your audience is composed of scientists or academics , you might use evidence-based arguments and appeal to the importance of empirical data and logical reasoning.

By understanding the values and beliefs of your audience, you can tailor your argument in a way that resonates with them and speaks to their concerns. This not only increases the likelihood that they will be persuaded by your argument, but also helps to build trust and rapport with your audience, which can be invaluable in future interactions.

- Consider the social and cultural background of the context : Different contexts may have unique social and cultural factors that impact the way people think and communicate. Take the time to understand these factors, and adjust your approach accordingly.

- If you are presenting in a multicultural setting , be mindful of cultural differences in communication styles and nonverbal cues. For example, some cultures may place a higher value on direct communication, while others may prefer indirect or more nuanced communication.

- If you are presenting in a political context , be aware of the current political climate and the potential impact that may have on your argument. Consider how your argument may be perceived through different political lenses, and be prepared to address any concerns or objections related to political ideologies.

- If you are presenting to a group with diverse backgrounds and experiences , be sensitive to the ways in which different individuals may interpret your argument based on their personal histories and identities. Avoid assumptions and stereotypes, and strive to create a safe and inclusive space where everyone feels heard and valued.

By considering the social and cultural background of the context, you can avoid potential misunderstandings and conflicts, and increase the effectiveness of your argument. This shows that you are respectful of the unique perspectives and experiences of your audience, and are committed to engaging in productive and meaningful dialogue.

- Use data and evidence that speaks to your audience : When presenting your argument, make sure to use data and evidence that is relevant and compelling to your audience. If you’re speaking to a group of scientists, for example, you may want to focus on studies and experiments that support your case.

- If you are presenting to a group of policymakers , use data and statistics that highlight the potential impact of your argument on society as a whole. Show how your proposed policy or solution can address a pressing social or economic issue, and provide concrete examples of successful implementation in similar contexts.

- If you are presenting to a group of business leaders , use financial data and market research to demonstrate the potential ROI of your argument. Show how your proposal can increase profits, improve efficiency, or enhance the reputation of the company, and provide case studies of successful implementation in other organizations.

- If you are presenting to a group of activists or advocates , use personal stories and testimonials to illustrate the human impact of your argument. Show how your proposal can make a tangible difference in the lives of individuals or communities, and provide examples of successful implementation in similar contexts.

By using data and evidence that speaks to your audience, you can demonstrate your credibility and expertise on the topic, and show that you have a deep understanding of their needs and concerns. This can help to build trust and increase the likelihood that your argument will be accepted and acted upon.

Preparing and structuring the argument

Once you have a clear understanding of your audience and context, the next step in presenting and defending your arguments is to prepare and structure your argument effectively.

A strong argument is one that is clear , concise , and well-supported with evidence .

To achieve this, there are several steps you can take to prepare and structure your argument effectively.

- Identify your main claim : The first step in preparing a strong argument is to identify your main claim or thesis. This should be a clear statement that summarizes the central point of your argument.

- Organize supporting evidence : Once you have identified your main claim, the next step is to organize supporting evidence that will help you make your case. This could include data, research studies, expert opinions, or personal experiences.

- Anticipate counter-arguments : When preparing your argument, it is important to anticipate potential counter-arguments that may be raised by your audience. This will help you address these objections in a clear and effective way.

There are several different formats that can be used to structure an argument effectively.

Argument map

An argument map is a tool that helps to identify the main claim and supporting reasons, and how they are connected to each other. By using an argument map, you can better understand the strength of your argument and identify potential weaknesses.

Outline your thesis and your main points and then use the map to create a narrative, either in a problem-solution format or persuasive speech format.

Here is what an argument map to support the building of a park could look like:

Note that the map contains supporting reasons (with backing evidence) and it also includes counter-arguments and their rebuttals.

You can then use this argument map for creating your talking points in one of the formats below.

Problem-solution format

- PROBLEM-SOLUTION format :

In this format, you should first outline a problem, and then present a solution to that problem. This can be a highly effective way of framing an argument, as it helps the audience to see the value of your proposed solution.

The problem-solution format is a common way of structuring an argument, particularly when the goal is to persuade the audience to take action on a particular issue . Here is a typical structure for a problem-solution format:

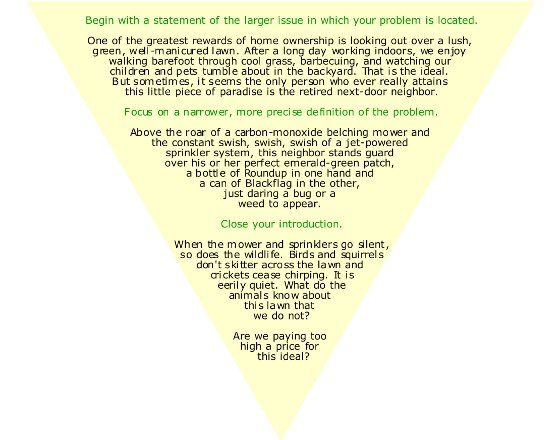

- Introduction : In the introduction, you should introduce the problem you will be addressing, and provide some background information to help the audience understand the issue. This might include statistics, personal anecdotes, or news stories that highlight the severity of the problem.

- Problem : In this section, you should describe the problem in more detail, highlighting its causes and effects. You might also discuss why the problem is particularly important, and what the consequences might be if it is not addressed.

- Solution : In this section, you should present your proposed solution to the problem. This might include a specific policy proposal, a call to action for individuals, or a description of a program or initiative that you believe could help to address the problem. Use the argument map points already drafted at the previous step.

- Benefits : In this section, you should describe the benefits of your proposed solution. This might include the positive impact it could have on individuals or communities, the economic benefits of addressing the problem, or the social benefits of promoting a particular solution.

- Objections : In this section, you should anticipate potential objections to your proposed solution, and provide counter-arguments to address these objections. This can help to strengthen your argument and make it more persuasive.

- Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should summarize your argument and urge the audience to take action. This might include a call to contact their elected officials, donate to a particular organization, or take some other concrete step to address the problem.

By following this structure, you can present a clear and compelling argument that highlights the urgency of the issue at hand.

Persuasive speech format

- PERSUASIVE SPEECH format :

In a persuasive speech, the speaker presents an argument in a structured way, using clear transitions between different parts of the argument. This format typically includes an introduction, a body where the main points are presented and supported, and a conclusion that summarizes the argument and urges the audience to take action.

The persuasive speech format is a common way of structuring an argument, particularly when the goal is to persuade the audience to take action or change their beliefs about a particular issue. Here is a typical structure for a persuasive speech format:

- Introduction : In the introduction, you should grab the audience’s attention with a strong opening statement, and provide some background information on the topic you will be addressing. You should also introduce your main argument or thesis statement .

- Body : In the body of your speech, you should present your main points in a structured way, using clear transitions to move between different parts of the argument. Each point should be supported with evidence, such as data, research studies, or expert opinions. If you’ve already built your argument map, you should use the points you already drafted there.

Here is the breakdown of the body section:

a. Point 1: In this section, you should present your first main point, and support it with evidence.

b. Point 2: In this section, you should present your second main point, and support it with evidence.

c. Point 3: In this section, you should present your third main point, and support it with evidence.

d. Transition: After presenting your main points, you should transition to the conclusion of your speech.

- Counter-arguments : In this section, you should address potential counter-arguments that your audience may raise. This can help to strengthen your argument and make it more persuasive.

- Conclusion : In the conclusion, you should summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement. You should also provide a call to action, urging the audience to take a specific action or change their beliefs about the issue.

By following this structure, you can present a clear and compelling argument that is well-supported with evidence, and that effectively persuades your audience to take action or change their beliefs.

No matter which format you choose, the key to presenting and defending your argument effectively is to be clear , concise , and well-prepared . By taking the time to structure your argument effectively, and anticipating potential counter-arguments, you can increase your chances of success and ensure that your message is heard and understood by your audience.

Presenting the argument

Once you have prepared and structured your argument, the next step is to present it in a way that engages the audience and effectively communicates your message.

Here are some techniques for presenting an argument effectively:

- Use persuasive language : Using strong, clear language can help to make your argument more persuasive. Use active voice, avoid jargon or technical language, and be concise.

For example:

• Instead of saying “The project will be completed in six months,” say “We will finish the project in six months.”

• Instead of using technical jargon, use simple language that can be easily understood by your audience. For example, instead of saying “We need to optimize the performance of our data processing pipeline,” say “We need to make our data processing faster and more efficient.”

02. Use strong, descriptive language that paints a clear picture in the minds of your audience.

For example, instead of saying “Our product is good,” say “Our product is the best on the market and will revolutionize the way you work.”

- Utilize visual aids : Visual aids such as charts, graphs, and images can help to reinforce your argument and make it more memorable. Use them sparingly, and make sure they are easy to read and understand.

For example, if you are making a presentation on the benefits of a new product, you can use a chart to illustrate the increase in sales revenue since the product was introduced.

You could also use the argument map already prepared previously to organize and visually display the logical structure of your argument.

- Tell a story : Using storytelling techniques can be an effective way to engage the audience and make your argument more relatable. Use personal anecdotes, metaphors, or case studies to illustrate your points and make them more memorable.

For example, when presenting a proposal to implement a new initiative at work, you could begin by sharing a personal story of a time when a similar initiative was successfully implemented in a different organization, and the positive impact it had on the employees and the company’s overall success. This story could help to create an emotional connection with the audience and build support for your proposal.

You could also use case studies of other organizations that have implemented similar initiatives, and show the tangible benefits they have seen as a result. This approach can help to make your argument more concrete and relatable, and make it easier for the audience to understand the potential benefits of your proposal.

- Use humour : Humour can be a powerful tool for engaging the audience and making your argument more memorable. Use it sparingly, and make sure it is appropriate for the context.

Suppose you’re presenting an argument in favour of a healthier diet. You could start by saying something like, “I used to think that kale was just a decoration on my plate at restaurants. But then I tried it and realized it’s actually a vegetable.” This can get a chuckle from the audience and help to make your point in a more relatable way. From there, you could go on to discuss the benefits of incorporating more fruits and vegetables into one’s diet.

- Engage the audience : Engaging the audience can help to build rapport and create a sense of connection. Ask questions, use rhetorical devices such as repetition or parallelism, and make eye contact to create a sense of intimacy.

Here are some examples you can use to engage your audience:

- Ask a question that requires a show of hands, such as “How many of you have ever experienced this situation?” This creates a sense of participation and involvement.

- Use rhetorical questions to make the audience think and engage with the topic. For example, “What would happen if we continue to ignore this issue?”

- Use repetition to emphasize key points and make them more memorable. For example, “We need to act now, we need to act fast, and we need to act together.”

- Make eye contact with the audience to create a sense of intimacy and connection. This can help to build trust and credibility.

By using these techniques, you can present your argument in a way that is engaging, memorable, and persuasive. Remember to practice your presentation beforehand, and to anticipate potential questions or objections that the audience may raise. By being well-prepared and confident in your argument, you can effectively defend your position and persuade others to see things your way.

Defending the argument

Defending your argument is just as important as presenting it. Here are some strategies for effectively defending your argument:

- Use evidence and logical reasoning : Evidence and logical reasoning are key to making a strong argument. Use relevant facts, statistics, and examples to support your position, and use logical reasoning to connect your evidence to your main claim.

For example, in a business setting, you may be presenting a proposal for a new product or strategy. To effectively persuade your audience, you can use data to support the potential success of your idea. You can present market research, customer feedback, or industry trends to demonstrate that your proposal is not only feasible but also profitable.

Additionally, you can use logical reasoning to explain how your proposal aligns with the company’s goals and values, and how it can address any potential challenges or concerns.

By using evidence and logical reasoning, you can build a convincing argument that is grounded in facts and reason.

- Anticipate objections : Anticipating objections can help you to prepare effective counter-arguments. Put yourself in the shoes of your opponent and try to think of potential objections or counter-arguments they may raise. Be prepared to address these objections with evidence and logical reasoning.

Here is how you can anticipate objections in the context of building a new park in a community.

For example someone may object to the new park on the basis that it will increase traffic and noise in the area. In response to this objection, you could anticipate this concern and address it by presenting evidence that the park’s design includes traffic-calming measures such as speed bumps and traffic lights, and that noise from the park will be managed through measures like the installation of sound barriers. By anticipating and addressing this objection in advance, it can help to alleviate concerns and increase the likelihood of gaining support for the park’s construction.

- Avoid fallacies : Fallacies are errors in reasoning that can weaken your argument. Common fallacies include ad hominem attacks, straw man arguments, and false dichotomies. Be aware of these fallacies and avoid them in your argument.

- Ad hominem : Attacking the character or personal traits of your opponent instead of addressing their argument. For example, saying “You can’t trust John’s opinion on the park proposal because he’s not even a resident of this city.”

- Straw man : Misrepresenting your opponent’s argument in order to make it easier to attack. For example, saying “Opponents of the park just want to pave over all the green space in the city and turn it into a concrete jungle.”

- False dichotomy : Presenting only two options when there are actually more. For example, saying “We can either build the park or let the land sit unused forever.” When in reality, there may be other alternatives.

In any context (including that of building a new park), it’s important to avoid these fallacies in order to make a strong, persuasive argument. By staying focused on the facts and avoiding personal attacks or misrepresentations, you can demonstrate the value of your proposal in a clear and compelling way.

- Acknowledge the opponent’s views : Acknowledging your opponent’s views can help to build credibility and create a sense of respect. Even if you disagree with their position, try to understand their perspective and acknowledge the points that they make.

Let’s use the example of proposing a new product to a potential market: if your opponents argue that the product may not appeal to the new market, you can acknowledge their concern and provide evidence that shows the product’s success in similar markets. This approach demonstrates that you have considered their viewpoint and have a well-researched argument.

Additionally, you can acknowledge that there may be challenges in introducing a new product to a new market, and propose a plan to address these challenges, such as market research, targeted advertising, or partnerships with local businesses.

By acknowledging your opponent’s views and addressing their concerns, you can build credibility and increase the likelihood of a successful proposal.

- Provide alternative evidence or counter-examples : Providing alternative evidence or counter-examples can help to strengthen your argument and refute counter-arguments. Use relevant facts, statistics, or examples to support your position and show why your argument is more persuasive.

Here are some examples that might inspire you:

- If someone argues that all processed foods are unhealthy, you can provide examples of processed foods that are actually healthy, such as fortified breakfast cereals or packaged fruits and vegetables.

- If someone argues that organic foods are too expensive, you can provide evidence that shows that the long-term health benefits of consuming organic foods outweigh the initial cost, such as reduced medical expenses and improved quality of life.

- If someone argues that renewable energy sources like solar and wind are unreliable, you can provide examples of successful implementation of renewable energy in other countries, as well as statistics showing that the cost of renewable energy is decreasing while the reliability is increasing.

By using these strategies, you can effectively defend your argument and persuade others to see things your way. Remember to stay calm and composed, and to avoid getting defensive or emotional. By remaining confident and logical, you can effectively defend your argument and convince others to accept your position.

Dealing with emotional reactions

Presenting and defending an argument can be an emotional process, for both the speaker and the audience.

Here are some tips for managing emotional reactions:

- Stay calm and respectful : If you encounter emotional reactions during your presentation or defense, it’s important to stay calm and respectful. Avoid getting defensive or angry, and try to remain objective and rational in your responses.

An interesting example is if you are presenting an argument in a public setting, and a member of the audience interrupts you with a personal attack or insult. In this situation, it can be tempting to respond with a similar attack or to become defensive, but this will only escalate the situation and detract from the argument being presented. Instead, you should calmly address the interruption and steer the conversation back to the topic at hand. For example, you could say something like, “I understand that this is a sensitive topic, but let’s focus on the facts and evidence at hand to have a productive discussion.” By staying calm and respectful, you can maintain credibility and effectively defend your position.

- Use empathetic language : Using empathetic language can help to defuse emotional reactions and create a sense of understanding. Show that you understand the emotions of the audience or your opponent, and use language that demonstrates your empathy and compassion.

A good example is when you are discussing a controversial topic such as abortion. Instead of using language that might be perceived as attacking or dismissive, use empathetic language that acknowledges the emotional weight of the issue for both sides. For instance, saying “I understand that this is a deeply personal and emotional issue for many people” can help to create a more respectful and productive conversation, rather than immediately diving into arguments and counter-arguments.

- Recognize and address underlying issues : Sometimes, emotional reactions can be a sign of underlying issues that are not directly related to your argument. If you sense that there are deeper emotions or issues at play, try to address these concerns in a respectful and empathetic way.

An interesting example is when during a debate on a controversial policy, a member of the audience becomes visibly upset and begins to shout. Instead of ignoring or dismissing their reaction, the speaker takes a moment to acknowledge their emotion and asks if they would like to share their concerns. The audience member then explains that they have personal experience with the issue at hand and feel that their perspective has been ignored. The speaker listens attentively and responds with empathy, acknowledging the validity of their experience and promising to consider it in their argument. By addressing the underlying issue and showing empathy, the speaker is able to defuse the emotional reaction and create a more constructive discussion.

- Take a break if necessary : If emotions become too heated, it may be necessary to take a break and regroup. Allow time for both yourself and the audience to calm down, and resume the discussion when emotions have subsided.

For example, during a meeting with a potential business partner, you may encounter a disagreement about a certain aspect of the partnership. If the conversation becomes heated and emotions start to rise, it may be helpful to take a break. You can suggest taking a short break to allow both parties to gather their thoughts and emotions, and come back to the discussion with a clear head. This can help to prevent the conversation from derailing and allow for a more productive discussion.

Overall, by managing emotional reactions in a calm and respectful manner, you can create a more productive and effective discussion. Remember that emotions are a natural part of the human experience, and that acknowledging and addressing them can lead to better communication and understanding.

The ability to present and defend arguments effectively is crucial, be it in professional settings, political arenas, or personal interactions. These skills of articulating and supporting points persuasively are vital for fostering constructive dialogues and making sound decisions.

Throughout this article, we’ve discussed the key elements of effective argumentation, from understanding the audience and context to presenting and defending the argument itself. We’ve explored different techniques for structuring an argument, engaging the audience, and responding to objections, as well as strategies for managing emotional reactions and maintaining a respectful and productive dialogue.

At its core, effective argumentation is about more than just winning a debate or proving a point. It’s about building trust , fostering understanding , and working towards common goals .

By approaching argumentation with an open mind and a willingness to listen and learn, we can create more meaningful and productive discussions, and ultimately make better decisions.

So the next time you find yourself in a situation where you need to present or defend an argument, remember the tips and techniques discussed in this article.

And always remember that the key to effective argumentation is not just about winning, but about finding common ground and moving forward together.

You May Also Like…

The Importance of Critical Thinking when Using ChatGPT (and Other Large Language Models)

Artificial intelligence has made tremendous strides in recent years, allowing for the creation of conversational AI...

How to Critically Evaluate News and Media Sources

I think we all agree that access to information has never been easier. With the click of a button, we can access an...

Critical Thinking in the Workplace

Imagine that you're in a job interview and the interviewer asks you to describe a time when you had to solve a complex...

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Last places remaining for June 30th start. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 9 Ways to Construct a Compelling Argument

You might also enjoy…

- How to Write with Evidence in a Time of Fake News

- 4 Ridiculous Things Actually Suggested in Parliament

But especially in the circumstances that we’re deeply convinced of the rightness of our points, putting them across in a compelling way that will change other people’s mind is a challenge. If you feel that your opinion is obviously right, it’s hard work even to understand why other people might disagree. Some people reach this point and don’t bother to try, instead concluding that those who disagree with them must be stupid, misled or just plain immoral. And it’s almost impossible to construct an argument that will persuade someone if you’re starting from the perspective that they’re either dim or evil. In the opposite set of circumstances – when you only weakly believe your perspective to be right – it can also be tricky to construct a good argument. In the absence of conviction, arguments tend to lack coherence or force. In this article, we take a look at how you can put together an argument, whether for an essay, debate speech or social media post, that is forceful, cogent and – if you’re lucky – might just change someone’s mind.

1. Keep it simple

Almost all good essays focus on a single powerful idea, drawing in every point made back to that same idea so that even someone skim-reading will soon pick up the author’s thesis. But when you care passionately about something, it’s easy to let this go. If you can see twenty different reasons why you’re right, it’s tempting to put all of them into your argument, because it feels as if the sheer weight of twenty reasons will be much more persuasive than just focusing on one or two; after all, someone may be able rebut a couple of reasons, but can they rebut all twenty? Yet from the outside, an argument with endless different reasons is much less persuasive than one with focus and precision on a small number of reasons. The debate in the UK about whether or not to stay in the EU was a great example of this. The Remain campaign had dozens of different reasons. Car manufacturing! Overfishing! Cleaner beaches! Key workers for the NHS! Medical research links! Economic opportunities! The difficulty of overcoming trade barriers! The Northern Irish border! Meanwhile, the Leave campaign boiled their argument down to just one: membership of the EU means relinquishing control. Leaving it means taking back control. And despite most expectations and the advice of most experts, the simple, straightforward message won. Voters struggled to remember the many different messages put out by the Remain campaign, as compelling as each of those reasons might have been; but they remembered the message about taking back control.

2. Be fair on your opponent

One of the most commonly used rhetorical fallacies is the Strawman Fallacy. This involves constructing a version of your opponent’s argument that is much weaker than the arguments they might use themselves, in order than you can defeat it more easily. For instance, in the area of crime and punishment, you might be arguing in favour of harsher prison sentences, while your opponent argues in favour of early release where possible. A Strawman would be to say that your opponent is weak on crime, wanting violent criminals to be let out on to the streets without adequate punishment or deterrence, to commit the same crimes again. In reality, your opponent’s idea might exclude violent criminals, and focus on community-based restorative justice that could lead to lower rates of recidivism. To anyone who knows the topic well, if your argument includes a Strawman, then you will immediately have lost credibility by demonstrating that either you don’t really understand the opposing point of view, or that you simply don’t care about rebutting it properly. Neither is persuasive. Instead, you should be fair to your opponent and represent their argument honestly, and your readers will take you seriously as a result

3. Avoid other common fallacies

It’s worth taking the time to read about logical fallacies and making sure that you’re not making them, as argument that rest of fallacious foundations can be more easily demolished. (This may not apply on social media, but it does in formal debating and in writing essays). Some fallacies are straightforward to understand, such as the appeal to popularity (roughly “everyone agrees with me, so I must be right!”), but others are a little trickier. Take “begging the question”, which is often misunderstood. It gets used to mean “raises the question” (e.g. “this politician has defended terrorists, which raises the question – can we trust her?”), but the fallacy it refers to is a bit more complicated. It’s when an argument rests on the assumption that its conclusions are true. For example, someone might argue that fizzy drinks shouldn’t be banned in schools, on the grounds that they’re not bad for students’ health. How can we know that they’re not bad for students’ health? Why, if they were, they would be banned in schools! When put in a condensed form like this example, the flaw in this approach is obvious, but you can imagine how you might fall for it over the course of a whole essay – for instance, paragraphs arguing that teachers would have objected to hyperactive students, parents would have complained, and we can see that none of this has happened because they haven’t yet been banned. With more verbosity, a bad argument can be hidden, so check that you’re not falling prey to it in your own writing.

4. Make your assumptions clear

Every argument rests on assumptions. Some of these assumptions are so obvious that you’re not going to be aware that you’re making them – for instance, you might make an argument about different economic systems that rests on the assumption that reducing global poverty is a good thing. While very few people would disagree with you on that, in general, if your assumption can be proven false, then the entire basis of your argument is undermined. A more controversial example might be an argument that rests on the assumption that everyone can trust the police force – for instance, if you’re arguing for tougher enforcement of minor offences in order to prevent them from mounting into major ones. But in countries where the police are frequently bribed, or where policing has obvious biases, such enforcement could be counterproductive. If you’re aware of such assumptions underpinning your argument, tackle them head on by making them clear and explaining why they are valid; so you could argue that your law enforcement proposal is valid in the particular circumstances that you’re suggesting because the police force there can be relied on, even if it wouldn’t work everywhere.

5. Rest your argument on solid foundations

If you think that you’re right in your argument, you should also be able to assemble a good amount of evidence that you’re right. That means putting the effort in and finding something that genuinely backs up what you’re saying; don’t fall back on dubious statistics or fake news . Doing the research to ensure that your evidence is solid can be time-consuming, but it’s worthwhile, as then you’ve removed another basis on which your argument could be challenged. What happens if you can’t find any evidence for your argument? The first thing to consider is whether you might be wrong! If you find lots of evidence against your position, and minimal evidence for it, it would be logical to change your mind. But if you’re struggling to find evidence either way, it may simply be that the area is under-researched. Prove what you can, including your assumptions, and work from there.

6. Use evidence your readers will believe

So far we’ve focused on how to construct an argument that is solid and hard to challenge; from this point onward, we focus on what it takes to make an argument persuasive. One thing you can do is to choose your evidence with your audience in mind. For instance, if you’re writing about current affairs, a left-wing audience will find an article from the Guardian to be more persuasive (as they’re more likely to trust its reporting), while a right-wing audience might be more swayed by the Telegraph. This principle doesn’t just hold in terms of politics. It can also be useful in terms of sides in an academic debate, for instance. You can similarly bear in mind the demographics of your likely audience – it may be that an older audience is more skeptical of footnotes that consist solely of web addresses. And it isn’t just about statistics and references. The focus of your evidence as a whole can take your probable audience into account; for example, if you were arguing that a particular drug should be banned on health grounds and your main audience was teenagers, you might want to focus more on the immediate health risks, rather than ones that might only appear years or decades later.

7. Avoid platitudes and generalisations, and be specific

A platitude is a phrase used to the point of meaninglessness – and it may not have had that much meaning to begin with. If you find yourself writing something like “because family life is all-important” to support one of your claims, you’ve slipped into using platitudes. Platitudes are likely to annoy your readers without helping to persuade them. Because they’re meaningless and uncontroversial statements, using them doesn’t tell your reader anything new. If you say that working hours need to be restricted because family ought to come first, you haven’t really given your reader any new information. Instead, bring the importance of family to life for your reader, and then explain just how long hours are interrupting it. Similarly, being specific can demonstrate the grasp you have on your subject, and can bring it to life for your reader. Imagine that you were arguing in favour of nationalising the railways, and one of your points was that the service now was of low quality. Saying “many commuter trains are frequently delayed” is much less impactful than if you have the full facts to hand, e.g. “in Letchworth Garden City, one key commuter hub, half of all peak-time trains to London were delayed by ten minutes or more.”

8. Understand the opposing point of view

As we noted in the introduction, you can’t construct a compelling argument unless you understand why someone might think you were wrong, and you can come up with reasons other than them being mistaken or stupid. After all, we almost all target them same end goals, whether that’s wanting to increase our understanding of the world in academia, or increase people’s opportunities to flourish and seek happiness in politics. Yet we come to divergent conclusions. In his book The Righteous Mind , Jonathan Haidt explores the different perspectives of people who are politically right or left-wing. He summarises the different ideals people might value, namely justice, equality, authority, sanctity and loyalty, and concludes that while most people see that these things have some value, different political persuasions value them to different degrees. For instance, someone who opposes equal marriage might argue that they don’t oppose equality – but they do feel that on balance, sanctity is more important. An argument that focuses solely on equality won’t sway them, but an argument that addresses sanctity might.

9. Make it easy for your opponent to change their mind

It’s tricky to think of the last time you changed your mind about something really important. Perhaps to preserve our pride, we frequently forget that we ever believed something different. This survey of British voters’ attitudes to the Iraq war demonstrates the point beautifully. 54% of people supporting invading Iraq in 2003; but twelve years on, with the war a demonstrable failure, only 37% were still willing to admit that they had supported it at the time. The effect in the USA was even more dramatic. It would be tempting for anyone who genuinely did oppose the war at the time to be quite smug towards anyone who changed their mind, especially those who won’t admit it. But if changing your mind comes with additional consequences (e.g. the implication that you were daft ever to have believed something, even if you’ve since come to a different conclusion), then the incentive to do so is reduced. Your argument needs to avoid vilifying people who have only recently come around to your point of view; instead, to be truly persuasive, you should welcome them.

Images: pink post it hand ; megaphone girl ; pencil shavings ; meeting ; hand writing ; boxers ; pink trainers; tools ; magnifying glass ; bridge ; thinking girl ; puzzle hands

IOE - Faculty of Education and Society

Argument, voice, structure

Learn how to structure and present an argument in academic writing.

- Organise, structure and edit

- Present an argument

- Develop your academic voice

- Add more explanation

- State the relevance

- Add your own comment

- Add your own example

- Clarify your writing

- Definitions

- Cautious language and hedging

- Introductions

- Conclusions

- Linking and transitions

- Paragraphs

Tutor feedback on organisation

Organise, structure and edit.

Follow the basic steps below.

- First, make an outline plan for each paragraph, and then select the information, examples and comments for each point.

- Try to make sure you only have one main point per paragraph.

- Sometimes you will find that you need to delete some of the information. Just save it onto a different Word document, and perhaps you can use it in a different essay.

- Make sure this essay is focused on the title, with the main points discussed well and in detail, rather than many different minor points. Everything should be clearly relevant, and less is more!

- To see the structure, the reader also needs to know how each paragraph connects to the previous one. It can help to add transition phrases, to show how each idea flows from the previous one.

Back to top

Present an argument

An argument, in simple terms, is a claim plus support for that claim. Make sure you use language that indicates that you are forming an argument. Compare the following simplified examples.

These three examples are claims, or series of claims, but they are not arguments.

- There is no single accepted definition of ethics.

- A new definition of ethics is needed. Here are some existing definitions of the concept of ethics. In addition, here is a suggested new definition.

- The existing definitions of the concept of ethics are too divergent to be useful. In addition, an updated definition of ethics is needed.

These three examples are arguments. Notice the linguistic indicator.

- The existing definitions of the concept of ethics are too divergent to be useful. Therefore, an updated definition of ethics is needed.

- The existing definitions of the concept of ethics are too divergent to be useful. This indicates that an updated definition of ethics is needed.

- A new definition of the concept of ethics is needed, because the existing definitions are inadequate for the current situation. Here are the existing definitions, and here is why they are inadequate. In conclusion, a new definition is required.

Sometimes, as in the simple examples above, the same information can be used either to construct an argument, or simply to write a description. Make sure you are using language that indicates that you are presenting an argument. Try using very direct language, at least in your first draft. This will help you to make sure that you really are constructing an argument.

- In this paper, the main claim I make is that a new definition of ethics is required. I support this claim with the following points. Firstly...

- In this paper, I argue that a new definition of ethics is required. I support this claim with the following points. Firstly...

NB: Argumentation can become complex. This section merely presents the difference between presenting an argument and a complete absence of argument.

Develop your academic voice

In an academic context, the concept of “voice” can mean different things to different people. Despite the variations in meaning, if you become more proficient at using language, you will find it easier to express more precise concepts and write with confidence. It is also worth asking your tutor for examples of writing where they feel the voice is clearly visible.

Add more explanation

Adding more explanation means writing down the reasons why something might be the way it is. These examples come from a discussion on ethics within a student proposal.

In Example A below, some claims are made without enough explanation. The writing appears vague, and the reader is left asking further questions about the claims. In Example B below, the student has added more explanation. This includes reasons why something might be the case.

The respondents may be worried about their responses, and there are various ethical considerations. Interviewing staff members also brings various ethical issues. Confidentiality will be central, and I will need to use pseudonyms for the participants.

As the respondents will be discussing changes within a small organization, any individuals they mention may be identifiable to other organization members. As a result, respondents may worry that they will be seen to be passing judgment on friends and peers. In terms of ethical issues, uncomfortable feelings may be provoked, both for respondents and possibly for non-participant staff or students. In addition, staff members may worry that if they speak freely about the small organization, some of their thoughts may be considered irresponsible, unprofessional, "discreditable or incriminating" (Lee & Renzetti, 1993:ix), for example if they were to talk about difficulties at work, or problems within the organization. This means that confidentiality will be central, to protect the respondents and to mitigate their concerns about speaking freely. I will ensure that the organisation is disguised in the way it is written up, and use pseudonyms chosen by the participants. I will also reassure the respondents about these measures before they participate.

State the relevance

State directly how each point, or each paragraph, is connected to the title or the overall argument. If you feel that a point is relevant, but you have received feedback that your tutor does not, you could consider adding more explanation as to how or why it is connected. Useful phrases include:

- This is important because...

- This is relevant to X because...

- In terms of [the main topic], this means...

- The significance of this is...

Add your own comment

In the example below, the student has added a comment as well as an example. A comment could be:

- To support the ideas.

- To suggest the ideas are not valid.

- To show how the ideas connect to something else.

- To comment on the context.

- To add another critical comment.

Make sure it is clear, through the language you use, which is your comment, and which are the ideas from your reference.

The responsibility for learning how to reference correctly and avoid plagiarism tends to be passed from the university to the students, as Sutherland-Smith (2010:9) found, through her study of eighteen policies on plagiarism from different universities. She points out that many universities provide self-access resources for students to try to learn more about this area. An example of this can be found on the website “Writing Centre Online” (UCL Institute of Education, 2019), which includes a “Beginners Guide” page with step-by-step instructions on avoiding plagiarism, as well as various links to referencing and plagiarism resources. Despite this type of provision, Sutherland-Smith observes, the support provided is, on the whole, inadequate. It is interesting to note that this inadequacy can be seen at both an institutional level and from a student perspective, which will have implications as discussed in the following section . Sutherland-Smith expands further to explain that this inadequacy is partly because the advice provided is not specific enough for each student, and partly because distance students will often receive even less support, possibly, we could note, as they are wholly reliant on online materials . She concludes that these issues carry implications for the decisions around plagiarism management, as some students may receive more assistance than others, leading to questions of inequity. It could be considered that inequities are a particularly important issue in discussions of plagiarism management, given that controls on plagiarism could be seen, in principle, as intended to make the system fairer .

- Sutherland-Smith, W. (2010). “Retribution, deterrence and reform: the dilemmas of plagiarism management in universities”, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management , 32:1 5-16. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13600800903440519 (Last accessed on 31 January 2020).

- UCL Institute of Education (2020). Writing Centre Online. Available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe-writing-centre (Last accessed on 31 January 2020).

Useful links

- Academic reading: Reading critically

- Academic writing: Writing critically

Add your own example

In the example below, the student has added an example from their own knowledge or experience. This can be a good way to start to add your own voice. You could add an example from:

- your own practice or professional experience

- from observations you have made

- from other literature or published materials.

Include an example with a phrase such as “To illustrate...” or “An example of this can be seen in...”. Include the reference if your example is from published materials.

The responsibility for learning how to reference correctly and avoid plagiarism tends to be passed from the university to the students, as Sutherland-Smith (2010:9) found, through her study of eighteen policies on plagiarism from different universities. She points out that many universities provide self-access resources for students to try to learn more about this area. An example of this can be found on the website “Writing Centre Online” (UCL Institute of Education, 2019), which includes a “Beginners Guide” page with step-by-step instructions on avoiding plagiarism, as well as various links to referencing and plagiarism resources. Despite this type of provision, Sutherland-Smith observes, the support provided is, on the whole, inadequate. Sutherland-Smith expands further to explain that this inadequacy is partly because the advice provided is not specific enough for each student, and partly because distance students will often receive even less support. She concludes that these issues carry implications for the decisions around plagiarism management, as some students may receive more assistance than others, leading to questions of inequity.

- Sutherland-Smith, W. (2010). “Retribution, deterrence and reform: the dilemmas of plagiarism management in universities”, Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 32:1 5-16. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/13600800903440519 (Last accessed on 31 January 2020).

- UCL Institute of Education (2020). IOE Writing Centre Online. Available at: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe-writing-centre (Last accessed on 31 January 2020).

Clarify your writing

Clarify means “make more clear”. In essence, look at your language choices, and also look at what you have not stated. If you are told to clarify a point, you could try to rewrite it in shorter sentences, as a starting point. Next, add more detail, even if it seems obvious to you. Compare these two sentences:

- The common myths are revisited in this paper.

- This paper includes a discussion of several contested areas, including X and Y.

The second sentence is (arguably) clearer, as it has replaced the word “myth” with “contested areas”, and instead of “revisited”, it uses “includes a discussion of”. Examples also help to clarify, as they provide the reader with a more concrete illustration of the meaning.

Definitions

Providing a definition helps to make sure the reader understands the way that you are using the terminology in your writing. This is important as different terms might have more than one interpretation or usage. Remember that dictionaries are not considered suitable sources for definitions, as they will provide the general meaning, not the academic meaning or the way the term is used in your field.

If you can't find a precise “definition” as such in the literature, you can say that “the term is used to refer to XYZ”, and summarise or describe it in your own words. You can also use the phrase “For the purposes of this discussion, the term XYZ will be taken to refer to ...”.

The paragraphs below have an example of a definition with various interpretations. This level of discussion is not always necessary; it depends on how much agreement or disagreement there is on the meaning of the term.

This extract is from the “definitions” section of a Master’s assignment.

Purpose and definitions of coaching It is worth outlining the boundaries and purpose of the term “coaching” before proceeding with the discussion. In general, “coaching” tends to be used within human resource management and organisational theory to refer to a particular type of helping relationship or conversation (Boyatzis, Smith and Blaize, 2006). The object of help in this context is subject to some divergences in interpretation. Indeed, one feature shared by articles about coaching seems to be that authors frequently point out how little agreement there is on the use of the term, and how inconsistently it is used (see, for example, Boyatzis, Smith and Blaize, 2006:12, or Gray and Goregaokar, 2010:526). Some go further, linking the widespread adoption of coaching to the range of interpretations, lamenting that "the very popularity of the approach has resulted in greater confusion" (Clutterbuck, 2008:9), or pointing out with apparent surprise that "despite its popularity, there is little consensus on the nature of executive coaching" (Gray et al, 2011:863). It has even been described as "a kind of “catch-all” concept, covering whatever you want to put under it" (Arnaud, 2003:1133). Variations appear in areas including the stated aims, the specific approach, the location of the meetings, or the techniques and methods used (ibid). Somewhat paradoxically, there appears to be a general consensus only on the lack of consensus.

In response to the lack of an accepted definition, some authors have attempted to clarify what the term “coaching” should refer to, and do so in particular by differentiating it from “mentoring”, a concept with which it is often associated. David Clutterbuck, who has been working in the field for at least 30 years, and who has published extensively on the topics of both coaching and mentoring, ( http://www.davidclutterbuckpartnership.com ), has frequently attempted to delineate the two activities. In a relatively recent article (Clutterbuck, 2008:8), he suggested that the term “coaching” should primarily be used when performance is addressed, rather than, say, holistic development, a recommendation which highlights that coaching takes place within the context of enhancing productivity at work. The focus on performance is echoed in more practical guidelines such as those written by Atkins and Lawrence (2012:44) in the industry publication IT Now, when they state "coaching is about performance, mentoring is personal".

Although it is often cited, this division between “performance” and “personal” could be considered slightly artificial, and even unnecessary. Indeed, as performance is “performed” by the person, it is interesting to notice what appears to be a denial of the potentially transformational aspect of conversations within a helping relationship. A full discussion of this denial is outside the scope of this short report, but it could be caused by various influencing factors. Those factors might include the wish to justify the allocation of resources towards an activity which should therefore be seen as closely related to profit and accountability, coupled with a suspicion of anything which might be construed as not immediately rational and goal-focused. In other words, to be justifiable within a business context, a belief may exist that coaching should be positioned as closely oriented to business goals. This belief could underlie the prevalence of assertions that coaching is connected more to performance management than to holistic development. However, this report takes the view that there may be a useful overlap, as described below.

Looking to research, the overlapping of personal development with performance management was recently addressed by Gray et al (2011), in a study which aimed to establish whether coaching was seen as primarily beneficial to the individual's development or to the organisation's productivity. In brief, Gray et al's (2011) paper indicates that although involvement in coaching might be experienced as therapeutic by many coachees, it is generally positioned in the literature and by companies which engage in it as something beneficial to the organisation, as mentioned above. The authors also concluded that coaching may enhance various management competencies. Overall, the study indicates that coaching may be of interest to organisations as something which may enhance staff performance and productivity. In addition, although it does not always appear as the primary focus, and is even denied as an intention by some authors as discussed above, it may be that participation in coaching could also bring developmental benefits to the individual.

In essence, this report takes the view that the term coaching refers to an arranged conversation or series of conversations within a work context, conversations which aim at allowing the coachee to discuss and gain clarity on various work-related challenges or goals. Although we will adhere to the general conception provided above of coaching as carrying the intention of enhancing performance or competencies, the potential for personal or holistic development will be acknowledged. Additionally, coaching is often linked in literature to leadership (Boyatzis, Smith and Blaize, 2006; Stern, 2004), yet this report does not adopt that pattern in a restrictive sense. In other words, we would either consider that participating as a coachee can be useful for any employee, not only leaders, or, alternatively, we would broaden the definition of “leadership” to include any colleague who may have an influence within the organisation: a description which could arguably include any staff member. Overall, therefore, the report and its recommendations will prioritise the potentially beneficial outcomes of conversations which fall within the realm of coaching, rather than restricting the discussion to whether or not any particular activity can legitimately be given this term. This may be a broader usage of the concept than that followed by some writers, but is grounded in the intention to provide a practicable analysis of the needs for coaching within an organisation. Within this context, this report is predominantly informed by psychoanalytic theory and practice, justified below.

Source: Anonymous UCL Institute of Education Student (2013)

Cautious language and hedging

Hedging is a type of language use which “protects” your claims. Using language with a suitable amount of caution can protect your claims from being easily dismissed. It also helps to indicate the level of certainty we have in relation to the evidence or support.

Text comparison

Compare the following two short texts, (A) and (B). You will notice that although the two texts are, in essence, saying the same thing, (B) has a significant amount of extra language around the claim. A large amount of this language is performing the function of “hedging”. How many differences do you see in the second text? What is the function/effect/purpose of each difference? You will probably notice that (B) is more “academic”, but it is important to understand why.

- A: Extensive reading helps students to improve their vocabulary.