- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Thinking and Intelligence

Problem Solving

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe problem solving strategies

- Define algorithm and heuristic

- Explain some common roadblocks to effective problem solving

People face problems every day—usually, multiple problems throughout the day. Sometimes these problems are straightforward: To double a recipe for pizza dough, for example, all that is required is that each ingredient in the recipe be doubled. Sometimes, however, the problems we encounter are more complex. For example, say you have a work deadline, and you must mail a printed copy of a report to your supervisor by the end of the business day. The report is time-sensitive and must be sent overnight. You finished the report last night, but your printer will not work today. What should you do? First, you need to identify the problem and then apply a strategy for solving the problem.

PROBLEM-SOLVING STRATEGIES

When you are presented with a problem—whether it is a complex mathematical problem or a broken printer, how do you solve it? Before finding a solution to the problem, the problem must first be clearly identified. After that, one of many problem solving strategies can be applied, hopefully resulting in a solution.

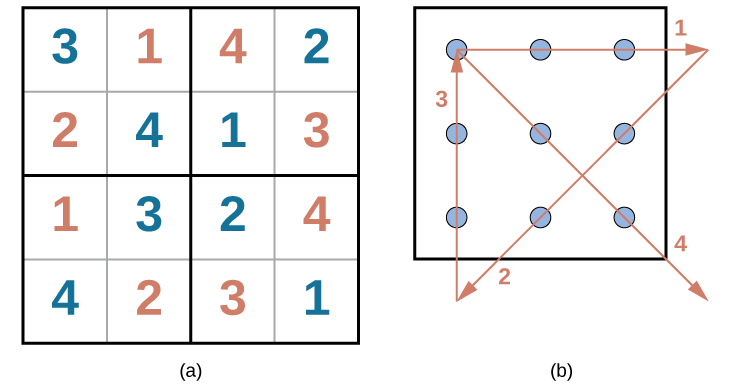

A problem-solving strategy is a plan of action used to find a solution. Different strategies have different action plans associated with them ( [link] ). For example, a well-known strategy is trial and error . The old adage, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again” describes trial and error. In terms of your broken printer, you could try checking the ink levels, and if that doesn’t work, you could check to make sure the paper tray isn’t jammed. Or maybe the printer isn’t actually connected to your laptop. When using trial and error, you would continue to try different solutions until you solved your problem. Although trial and error is not typically one of the most time-efficient strategies, it is a commonly used one.

Another type of strategy is an algorithm. An algorithm is a problem-solving formula that provides you with step-by-step instructions used to achieve a desired outcome (Kahneman, 2011). You can think of an algorithm as a recipe with highly detailed instructions that produce the same result every time they are performed. Algorithms are used frequently in our everyday lives, especially in computer science. When you run a search on the Internet, search engines like Google use algorithms to decide which entries will appear first in your list of results. Facebook also uses algorithms to decide which posts to display on your newsfeed. Can you identify other situations in which algorithms are used?

A heuristic is another type of problem solving strategy. While an algorithm must be followed exactly to produce a correct result, a heuristic is a general problem-solving framework (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). You can think of these as mental shortcuts that are used to solve problems. A “rule of thumb” is an example of a heuristic. Such a rule saves the person time and energy when making a decision, but despite its time-saving characteristics, it is not always the best method for making a rational decision. Different types of heuristics are used in different types of situations, but the impulse to use a heuristic occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind in the same moment

Working backwards is a useful heuristic in which you begin solving the problem by focusing on the end result. Consider this example: You live in Washington, D.C. and have been invited to a wedding at 4 PM on Saturday in Philadelphia. Knowing that Interstate 95 tends to back up any day of the week, you need to plan your route and time your departure accordingly. If you want to be at the wedding service by 3:30 PM, and it takes 2.5 hours to get to Philadelphia without traffic, what time should you leave your house? You use the working backwards heuristic to plan the events of your day on a regular basis, probably without even thinking about it.

Another useful heuristic is the practice of accomplishing a large goal or task by breaking it into a series of smaller steps. Students often use this common method to complete a large research project or long essay for school. For example, students typically brainstorm, develop a thesis or main topic, research the chosen topic, organize their information into an outline, write a rough draft, revise and edit the rough draft, develop a final draft, organize the references list, and proofread their work before turning in the project. The large task becomes less overwhelming when it is broken down into a series of small steps.

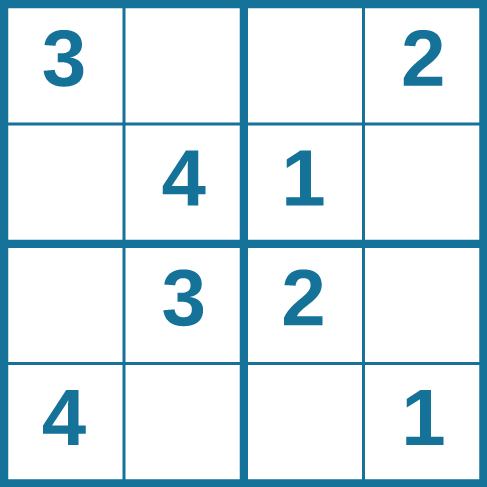

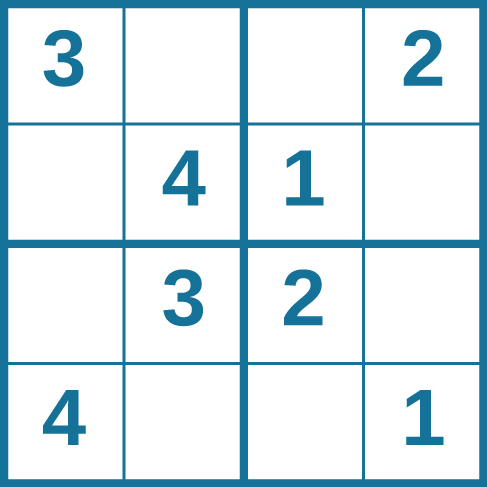

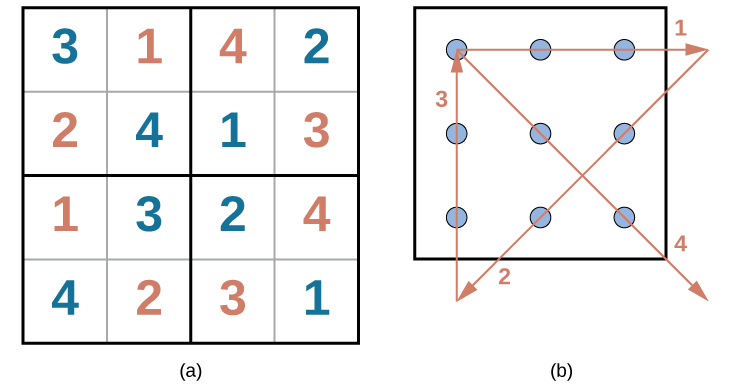

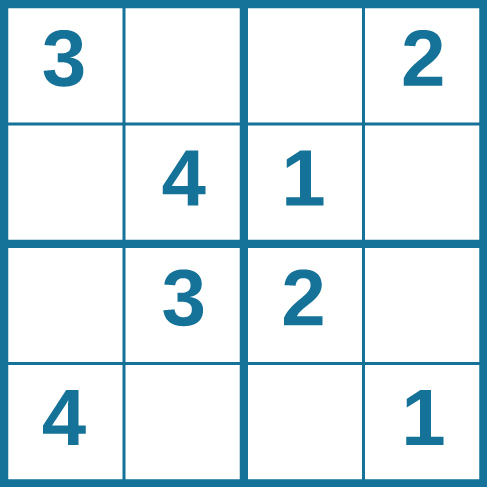

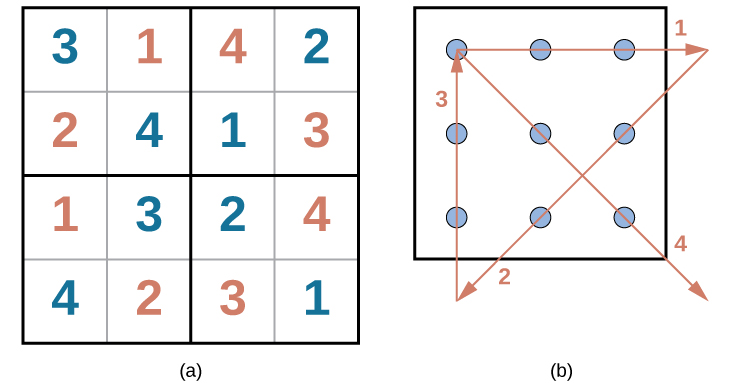

Problem-solving abilities can improve with practice. Many people challenge themselves every day with puzzles and other mental exercises to sharpen their problem-solving skills. Sudoku puzzles appear daily in most newspapers. Typically, a sudoku puzzle is a 9×9 grid. The simple sudoku below ( [link] ) is a 4×4 grid. To solve the puzzle, fill in the empty boxes with a single digit: 1, 2, 3, or 4. Here are the rules: The numbers must total 10 in each bolded box, each row, and each column; however, each digit can only appear once in a bolded box, row, and column. Time yourself as you solve this puzzle and compare your time with a classmate.

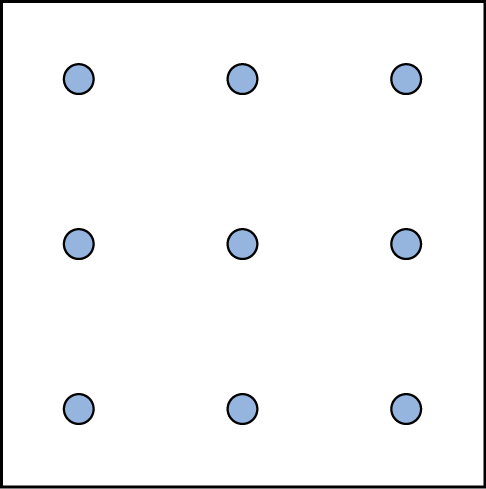

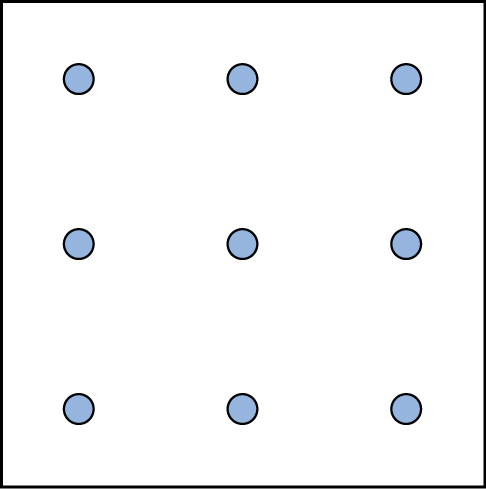

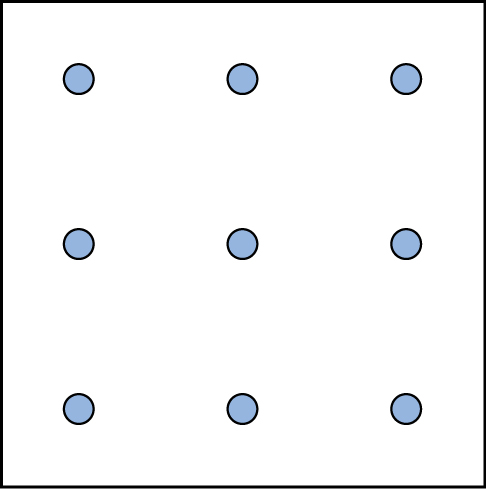

Here is another popular type of puzzle ( [link] ) that challenges your spatial reasoning skills. Connect all nine dots with four connecting straight lines without lifting your pencil from the paper:

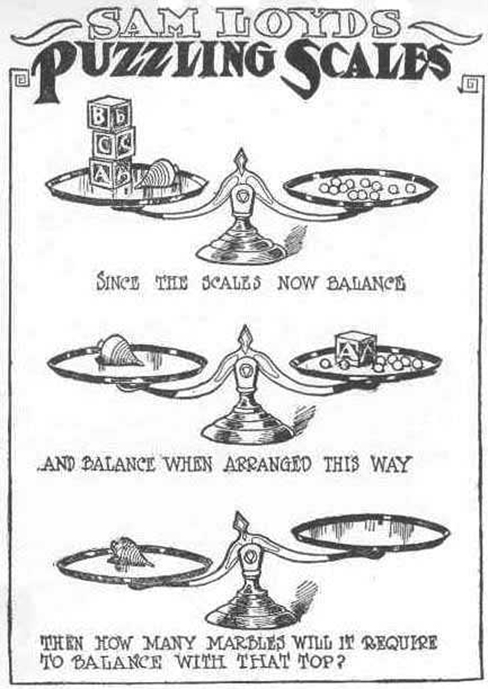

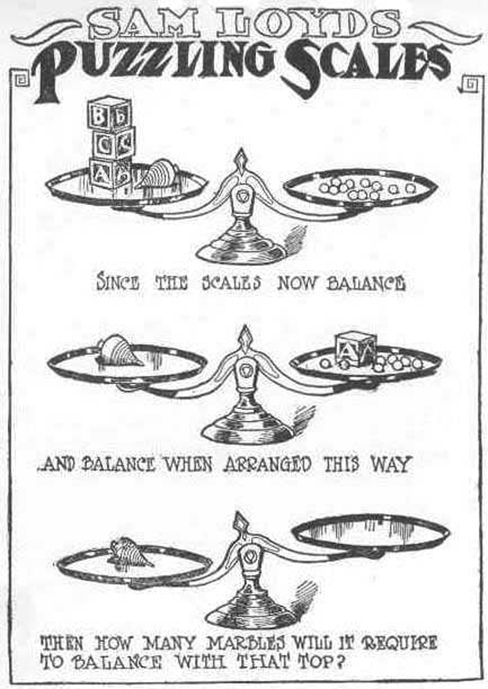

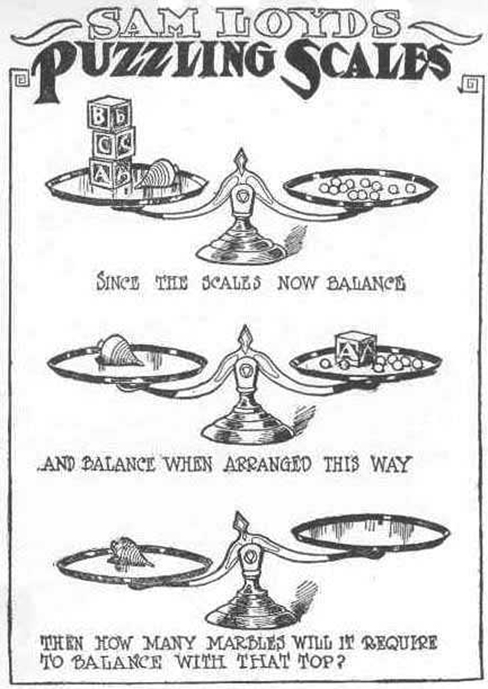

Take a look at the “Puzzling Scales” logic puzzle below ( [link] ). Sam Loyd, a well-known puzzle master, created and refined countless puzzles throughout his lifetime (Cyclopedia of Puzzles, n.d.).

PITFALLS TO PROBLEM SOLVING

Not all problems are successfully solved, however. What challenges stop us from successfully solving a problem? Albert Einstein once said, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Imagine a person in a room that has four doorways. One doorway that has always been open in the past is now locked. The person, accustomed to exiting the room by that particular doorway, keeps trying to get out through the same doorway even though the other three doorways are open. The person is stuck—but she just needs to go to another doorway, instead of trying to get out through the locked doorway. A mental set is where you persist in approaching a problem in a way that has worked in the past but is clearly not working now.

Functional fixedness is a type of mental set where you cannot perceive an object being used for something other than what it was designed for. During the Apollo 13 mission to the moon, NASA engineers at Mission Control had to overcome functional fixedness to save the lives of the astronauts aboard the spacecraft. An explosion in a module of the spacecraft damaged multiple systems. The astronauts were in danger of being poisoned by rising levels of carbon dioxide because of problems with the carbon dioxide filters. The engineers found a way for the astronauts to use spare plastic bags, tape, and air hoses to create a makeshift air filter, which saved the lives of the astronauts.

Check out this Apollo 13 scene where the group of NASA engineers are given the task of overcoming functional fixedness.

Researchers have investigated whether functional fixedness is affected by culture. In one experiment, individuals from the Shuar group in Ecuador were asked to use an object for a purpose other than that for which the object was originally intended. For example, the participants were told a story about a bear and a rabbit that were separated by a river and asked to select among various objects, including a spoon, a cup, erasers, and so on, to help the animals. The spoon was the only object long enough to span the imaginary river, but if the spoon was presented in a way that reflected its normal usage, it took participants longer to choose the spoon to solve the problem. (German & Barrett, 2005). The researchers wanted to know if exposure to highly specialized tools, as occurs with individuals in industrialized nations, affects their ability to transcend functional fixedness. It was determined that functional fixedness is experienced in both industrialized and nonindustrialized cultures (German & Barrett, 2005).

In order to make good decisions, we use our knowledge and our reasoning. Often, this knowledge and reasoning is sound and solid. Sometimes, however, we are swayed by biases or by others manipulating a situation. For example, let’s say you and three friends wanted to rent a house and had a combined target budget of $1,600. The realtor shows you only very run-down houses for $1,600 and then shows you a very nice house for $2,000. Might you ask each person to pay more in rent to get the $2,000 home? Why would the realtor show you the run-down houses and the nice house? The realtor may be challenging your anchoring bias. An anchoring bias occurs when you focus on one piece of information when making a decision or solving a problem. In this case, you’re so focused on the amount of money you are willing to spend that you may not recognize what kinds of houses are available at that price point.

The confirmation bias is the tendency to focus on information that confirms your existing beliefs. For example, if you think that your professor is not very nice, you notice all of the instances of rude behavior exhibited by the professor while ignoring the countless pleasant interactions he is involved in on a daily basis. Hindsight bias leads you to believe that the event you just experienced was predictable, even though it really wasn’t. In other words, you knew all along that things would turn out the way they did. Representative bias describes a faulty way of thinking, in which you unintentionally stereotype someone or something; for example, you may assume that your professors spend their free time reading books and engaging in intellectual conversation, because the idea of them spending their time playing volleyball or visiting an amusement park does not fit in with your stereotypes of professors.

Finally, the availability heuristic is a heuristic in which you make a decision based on an example, information, or recent experience that is that readily available to you, even though it may not be the best example to inform your decision . Biases tend to “preserve that which is already established—to maintain our preexisting knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and hypotheses” (Aronson, 1995; Kahneman, 2011). These biases are summarized in [link] .

Please visit this site to see a clever music video that a high school teacher made to explain these and other cognitive biases to his AP psychology students.

Were you able to determine how many marbles are needed to balance the scales in [link] ? You need nine. Were you able to solve the problems in [link] and [link] ? Here are the answers ( [link] ).

Many different strategies exist for solving problems. Typical strategies include trial and error, applying algorithms, and using heuristics. To solve a large, complicated problem, it often helps to break the problem into smaller steps that can be accomplished individually, leading to an overall solution. Roadblocks to problem solving include a mental set, functional fixedness, and various biases that can cloud decision making skills.

Review Questions

A specific formula for solving a problem is called ________.

- an algorithm

- a heuristic

- a mental set

- trial and error

A mental shortcut in the form of a general problem-solving framework is called ________.

Which type of bias involves becoming fixated on a single trait of a problem?

- anchoring bias

- confirmation bias

- representative bias

- availability bias

Which type of bias involves relying on a false stereotype to make a decision?

Critical Thinking Questions

What is functional fixedness and how can overcoming it help you solve problems?

Functional fixedness occurs when you cannot see a use for an object other than the use for which it was intended. For example, if you need something to hold up a tarp in the rain, but only have a pitchfork, you must overcome your expectation that a pitchfork can only be used for garden chores before you realize that you could stick it in the ground and drape the tarp on top of it to hold it up.

How does an algorithm save you time and energy when solving a problem?

An algorithm is a proven formula for achieving a desired outcome. It saves time because if you follow it exactly, you will solve the problem without having to figure out how to solve the problem. It is a bit like not reinventing the wheel.

Personal Application Question

Which type of bias do you recognize in your own decision making processes? How has this bias affected how you’ve made decisions in the past and how can you use your awareness of it to improve your decisions making skills in the future?

Problem Solving Copyright © 2014 by OpenStaxCollege is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Problems: Definition, Types, and Evidence

- Reference work entry

- pp 2690–2693

- Cite this reference work entry

- Norbert M. Seel 2

2175 Accesses

1 Citations

Problem solving

A distinction can be made between “task” and “problem.” Generally, a task is a well-defined piece of work that is usually imposed by another person and may be burdensome. A problem is generally considered to be a task, a situation, or person which is difficult to deal with or control due to complexity and intransparency. In everyday language, a problem is a question proposed for solution, a matter stated for examination or proof. In each case, a problem is considered to be a matter which is difficult to solve or settle, a doubtful case, or a complex task involving doubt and uncertainty.

Theoretical Background

The nature of human problem solving has been studied by psychologists over the past hundred years. Beginning with the early experimental work of the Gestalt psychologists in Germany, and continuing through the 1960s and early 1970s, research on problem solving typically operated with relatively simple laboratory problems, such as Duncker’s...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Berry, D. C., & Broadbent, D. E. (1995). Implicit learning in the control of complex systems: A reconsideration of some of the earlier claims. In P. A. Frensch & J. Funke (Eds.), Complex problem solving: The European perspective (pp. 131–150). Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Google Scholar

Broadbent, D. E. (1977). Levels, hierarchies, and the locus of control. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 29 , 181–201.

Article Google Scholar

Dörner, D. (1976). Problemlösen als Informationsverarbeitung . Stuttgart: Kohlhammer (Problem solving as information processing).

Dörner, D., Kreuzig, H. W., Reither, F., & Stäudel, T. (1983). Lohhausen. Vom Umgang mit Unbestimmtheit und Komplexität [Lohhausen. The concern with uncertainty and complexity] . Bern: Huber.

Dörner, D. (1989). Die Logik des Misslingens . Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Funke, J. (1992). Wissen über dynamische Systeme: Erwerb, Repräsentation und Anwendung . Berlin: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Funke, J., & Frensch, P. (1995). Complex problem solving research in North America and Europe: An integrative review. Foreign Psychology, 5 , 42–47.

Jonassen, D. H. (1997). Instructional design models for well-structured and ill-structured problem-solving learning outcomes. Educational Technology Research and Development, 45 (1), 65–94.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Newell, A., Shaw, J. C., & Simon, H. A. (1959). A general problem-solving program for a computer. Computers and Automation, 8 (7), 10–16.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education, University of Freiburg, Rempartstr. 11, 3. OG, Freiburg, 79098, Germany

Prof. Norbert M. Seel ( Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Norbert M. Seel .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Behavioral Sciences, Department of Education, University of Freiburg, 79085, Freiburg, Germany

Norbert M. Seel

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Seel, N.M. (2012). Problems: Definition, Types, and Evidence. In: Seel, N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_914

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_914

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1427-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1428-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

48 Problem Solving

Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of California, Santa Barbara

- Published: 03 June 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Problem solving refers to cognitive processing directed at achieving a goal when the problem solver does not initially know a solution method. A problem exists when someone has a goal but does not know how to achieve it. Problems can be classified as routine or nonroutine, and as well defined or ill defined. The major cognitive processes in problem solving are representing, planning, executing, and monitoring. The major kinds of knowledge required for problem solving are facts, concepts, procedures, strategies, and beliefs. Classic theoretical approaches to the study of problem solving are associationism, Gestalt, and information processing. Current issues and suggested future issues include decision making, intelligence and creativity, teaching of thinking skills, expert problem solving, analogical reasoning, mathematical and scientific thinking, everyday thinking, and the cognitive neuroscience of problem solving. Common themes concern the domain specificity of problem solving and a focus on problem solving in authentic contexts.

The study of problem solving begins with defining problem solving, problem, and problem types. This introduction to problem solving is rounded out with an examination of cognitive processes in problem solving, the role of knowledge in problem solving, and historical approaches to the study of problem solving.

Definition of Problem Solving

Problem solving refers to cognitive processing directed at achieving a goal for which the problem solver does not initially know a solution method. This definition consists of four major elements (Mayer, 1992 ; Mayer & Wittrock, 2006 ):

Cognitive —Problem solving occurs within the problem solver’s cognitive system and can only be inferred indirectly from the problem solver’s behavior (including biological changes, introspections, and actions during problem solving). Process —Problem solving involves mental computations in which some operation is applied to a mental representation, sometimes resulting in the creation of a new mental representation. Directed —Problem solving is aimed at achieving a goal. Personal —Problem solving depends on the existing knowledge of the problem solver so that what is a problem for one problem solver may not be a problem for someone who already knows a solution method.

The definition is broad enough to include a wide array of cognitive activities such as deciding which apartment to rent, figuring out how to use a cell phone interface, playing a game of chess, making a medical diagnosis, finding the answer to an arithmetic word problem, or writing a chapter for a handbook. Problem solving is pervasive in human life and is crucial for human survival. Although this chapter focuses on problem solving in humans, problem solving also occurs in nonhuman animals and in intelligent machines.

How is problem solving related to other forms of high-level cognition processing, such as thinking and reasoning? Thinking refers to cognitive processing in individuals but includes both directed thinking (which corresponds to the definition of problem solving) and undirected thinking such as daydreaming (which does not correspond to the definition of problem solving). Thus, problem solving is a type of thinking (i.e., directed thinking).

Reasoning refers to problem solving within specific classes of problems, such as deductive reasoning or inductive reasoning. In deductive reasoning, the reasoner is given premises and must derive a conclusion by applying the rules of logic. For example, given that “A is greater than B” and “B is greater than C,” a reasoner can conclude that “A is greater than C.” In inductive reasoning, the reasoner is given (or has experienced) a collection of examples or instances and must infer a rule. For example, given that X, C, and V are in the “yes” group and x, c, and v are in the “no” group, the reasoning may conclude that B is in “yes” group because it is in uppercase format. Thus, reasoning is a type of problem solving.

Definition of Problem

A problem occurs when someone has a goal but does not know to achieve it. This definition is consistent with how the Gestalt psychologist Karl Duncker ( 1945 , p. 1) defined a problem in his classic monograph, On Problem Solving : “A problem arises when a living creature has a goal but does not know how this goal is to be reached.” However, today researchers recognize that the definition should be extended to include problem solving by intelligent machines. This definition can be clarified using an information processing approach by noting that a problem occurs when a situation is in the given state, the problem solver wants the situation to be in the goal state, and there is no obvious way to move from the given state to the goal state (Newell & Simon, 1972 ). Accordingly, the three main elements in describing a problem are the given state (i.e., the current state of the situation), the goal state (i.e., the desired state of the situation), and the set of allowable operators (i.e., the actions the problem solver is allowed to take). The definition of “problem” is broad enough to include the situation confronting a physician who wishes to make a diagnosis on the basis of preliminary tests and a patient examination, as well as a beginning physics student trying to solve a complex physics problem.

Types of Problems

It is customary in the problem-solving literature to make a distinction between routine and nonroutine problems. Routine problems are problems that are so familiar to the problem solver that the problem solver knows a solution method. For example, for most adults, “What is 365 divided by 12?” is a routine problem because they already know the procedure for long division. Nonroutine problems are so unfamiliar to the problem solver that the problem solver does not know a solution method. For example, figuring out the best way to set up a funding campaign for a nonprofit charity is a nonroutine problem for most volunteers. Technically, routine problems do not meet the definition of problem because the problem solver has a goal but knows how to achieve it. Much research on problem solving has focused on routine problems, although most interesting problems in life are nonroutine.

Another customary distinction is between well-defined and ill-defined problems. Well-defined problems have a clearly specified given state, goal state, and legal operators. Examples include arithmetic computation problems or games such as checkers or tic-tac-toe. Ill-defined problems have a poorly specified given state, goal state, or legal operators, or a combination of poorly defined features. Examples include solving the problem of global warming or finding a life partner. Although, ill-defined problems are more challenging, much research in problem solving has focused on well-defined problems.

Cognitive Processes in Problem Solving

The process of problem solving can be broken down into two main phases: problem representation , in which the problem solver builds a mental representation of the problem situation, and problem solution , in which the problem solver works to produce a solution. The major subprocess in problem representation is representing , which involves building a situation model —that is, a mental representation of the situation described in the problem. The major subprocesses in problem solution are planning , which involves devising a plan for how to solve the problem; executing , which involves carrying out the plan; and monitoring , which involves evaluating and adjusting one’s problem solving.

For example, given an arithmetic word problem such as “Alice has three marbles. Sarah has two more marbles than Alice. How many marbles does Sarah have?” the process of representing involves building a situation model in which Alice has a set of marbles, there is set of marbles for the difference between the two girls, and Sarah has a set of marbles that consists of Alice’s marbles and the difference set. In the planning process, the problem solver sets a goal of adding 3 and 2. In the executing process, the problem solver carries out the computation, yielding an answer of 5. In the monitoring process, the problem solver looks over what was done and concludes that 5 is a reasonable answer. In most complex problem-solving episodes, the four cognitive processes may not occur in linear order, but rather may interact with one another. Although some research focuses mainly on the execution process, problem solvers may tend to have more difficulty with the processes of representing, planning, and monitoring.

Knowledge for Problem Solving

An important theme in problem-solving research is that problem-solving proficiency on any task depends on the learner’s knowledge (Anderson et al., 2001 ; Mayer, 1992 ). Five kinds of knowledge are as follows:

Facts —factual knowledge about the characteristics of elements in the world, such as “Sacramento is the capital of California” Concepts —conceptual knowledge, including categories, schemas, or models, such as knowing the difference between plants and animals or knowing how a battery works Procedures —procedural knowledge of step-by-step processes, such as how to carry out long-division computations Strategies —strategic knowledge of general methods such as breaking a problem into parts or thinking of a related problem Beliefs —attitudinal knowledge about how one’s cognitive processing works such as thinking, “I’m good at this”

Although some research focuses mainly on the role of facts and procedures in problem solving, complex problem solving also depends on the problem solver’s concepts, strategies, and beliefs (Mayer, 1992 ).

Historical Approaches to Problem Solving

Psychological research on problem solving began in the early 1900s, as an outgrowth of mental philosophy (Humphrey, 1963 ; Mandler & Mandler, 1964 ). Throughout the 20th century four theoretical approaches developed: early conceptions, associationism, Gestalt psychology, and information processing.

Early Conceptions

The start of psychology as a science can be set at 1879—the year Wilhelm Wundt opened the first world’s psychology laboratory in Leipzig, Germany, and sought to train the world’s first cohort of experimental psychologists. Instead of relying solely on philosophical speculations about how the human mind works, Wundt sought to apply the methods of experimental science to issues addressed in mental philosophy. His theoretical approach became structuralism —the analysis of consciousness into its basic elements.

Wundt’s main contribution to the study of problem solving, however, was to call for its banishment. According to Wundt, complex cognitive processing was too complicated to be studied by experimental methods, so “nothing can be discovered in such experiments” (Wundt, 1911/1973 ). Despite his admonishments, however, a group of his former students began studying thinking mainly in Wurzburg, Germany. Using the method of introspection, subjects were asked to describe their thought process as they solved word association problems, such as finding the superordinate of “newspaper” (e.g., an answer is “publication”). Although the Wurzburg group—as they came to be called—did not produce a new theoretical approach, they found empirical evidence that challenged some of the key assumptions of mental philosophy. For example, Aristotle had proclaimed that all thinking involves mental imagery, but the Wurzburg group was able to find empirical evidence for imageless thought .

Associationism

The first major theoretical approach to take hold in the scientific study of problem solving was associationism —the idea that the cognitive representations in the mind consist of ideas and links between them and that cognitive processing in the mind involves following a chain of associations from one idea to the next (Mandler & Mandler, 1964 ; Mayer, 1992 ). For example, in a classic study, E. L. Thorndike ( 1911 ) placed a hungry cat in what he called a puzzle box—a wooden crate in which pulling a loop of string that hung from overhead would open a trap door to allow the cat to escape to a bowl of food outside the crate. Thorndike placed the cat in the puzzle box once a day for several weeks. On the first day, the cat engaged in many extraneous behaviors such as pouncing against the wall, pushing its paws through the slats, and meowing, but on successive days the number of extraneous behaviors tended to decrease. Overall, the time required to get out of the puzzle box decreased over the course of the experiment, indicating the cat was learning how to escape.

Thorndike’s explanation for how the cat learned to solve the puzzle box problem is based on an associationist view: The cat begins with a habit family hierarchy —a set of potential responses (e.g., pouncing, thrusting, meowing, etc.) all associated with the same stimulus (i.e., being hungry and confined) and ordered in terms of strength of association. When placed in the puzzle box, the cat executes its strongest response (e.g., perhaps pouncing against the wall), but when it fails, the strength of the association is weakened, and so on for each unsuccessful action. Eventually, the cat gets down to what was initially a weak response—waving its paw in the air—but when that response leads to accidentally pulling the string and getting out, it is strengthened. Over the course of many trials, the ineffective responses become weak and the successful response becomes strong. Thorndike refers to this process as the law of effect : Responses that lead to dissatisfaction become less associated with the situation and responses that lead to satisfaction become more associated with the situation. According to Thorndike’s associationist view, solving a problem is simply a matter of trial and error and accidental success. A major challenge to assocationist theory concerns the nature of transfer—that is, where does a problem solver find a creative solution that has never been performed before? Associationist conceptions of cognition can be seen in current research, including neural networks, connectionist models, and parallel distributed processing models (Rogers & McClelland, 2004 ).

Gestalt Psychology

The Gestalt approach to problem solving developed in the 1930s and 1940s as a counterbalance to the associationist approach. According to the Gestalt approach, cognitive representations consist of coherent structures (rather than individual associations) and the cognitive process of problem solving involves building a coherent structure (rather than strengthening and weakening of associations). For example, in a classic study, Kohler ( 1925 ) placed a hungry ape in a play yard that contained several empty shipping crates and a banana attached overhead but out of reach. Based on observing the ape in this situation, Kohler noted that the ape did not randomly try responses until one worked—as suggested by Thorndike’s associationist view. Instead, the ape stood under the banana, looked up at it, looked at the crates, and then in a flash of insight stacked the crates under the bananas as a ladder, and walked up the steps in order to reach the banana.

According to Kohler, the ape experienced a sudden visual reorganization in which the elements in the situation fit together in a way to solve the problem; that is, the crates could become a ladder that reduces the distance to the banana. Kohler referred to the underlying mechanism as insight —literally seeing into the structure of the situation. A major challenge of Gestalt theory is its lack of precision; for example, naming a process (i.e., insight) is not the same as explaining how it works. Gestalt conceptions can be seen in modern research on mental models and schemas (Gentner & Stevens, 1983 ).

Information Processing

The information processing approach to problem solving developed in the 1960s and 1970s and was based on the influence of the computer metaphor—the idea that humans are processors of information (Mayer, 2009 ). According to the information processing approach, problem solving involves a series of mental computations—each of which consists of applying a process to a mental representation (such as comparing two elements to determine whether they differ).

In their classic book, Human Problem Solving , Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) proposed that problem solving involved a problem space and search heuristics . A problem space is a mental representation of the initial state of the problem, the goal state of the problem, and all possible intervening states (based on applying allowable operators). Search heuristics are strategies for moving through the problem space from the given to the goal state. Newell and Simon focused on means-ends analysis , in which the problem solver continually sets goals and finds moves to accomplish goals.

Newell and Simon used computer simulation as a research method to test their conception of human problem solving. First, they asked human problem solvers to think aloud as they solved various problems such as logic problems, chess, and cryptarithmetic problems. Then, based on an information processing analysis, Newell and Simon created computer programs that solved these problems. In comparing the solution behavior of humans and computers, they found high similarity, suggesting that the computer programs were solving problems using the same thought processes as humans.

An important advantage of the information processing approach is that problem solving can be described with great clarity—as a computer program. An important limitation of the information processing approach is that it is most useful for describing problem solving for well-defined problems rather than ill-defined problems. The information processing conception of cognition lives on as a keystone of today’s cognitive science (Mayer, 2009 ).

Classic Issues in Problem Solving

Three classic issues in research on problem solving concern the nature of transfer (suggested by the associationist approach), the nature of insight (suggested by the Gestalt approach), and the role of problem-solving heuristics (suggested by the information processing approach).

Transfer refers to the effects of prior learning on new learning (or new problem solving). Positive transfer occurs when learning A helps someone learn B. Negative transfer occurs when learning A hinders someone from learning B. Neutral transfer occurs when learning A has no effect on learning B. Positive transfer is a central goal of education, but research shows that people often do not transfer what they learned to solving problems in new contexts (Mayer, 1992 ; Singley & Anderson, 1989 ).

Three conceptions of the mechanisms underlying transfer are specific transfer , general transfer , and specific transfer of general principles . Specific transfer refers to the idea that learning A will help someone learn B only if A and B have specific elements in common. For example, learning Spanish may help someone learn Latin because some of the vocabulary words are similar and the verb conjugation rules are similar. General transfer refers to the idea that learning A can help someone learn B even they have nothing specifically in common but A helps improve the learner’s mind in general. For example, learning Latin may help people learn “proper habits of mind” so they are better able to learn completely unrelated subjects as well. Specific transfer of general principles is the idea that learning A will help someone learn B if the same general principle or solution method is required for both even if the specific elements are different.

In a classic study, Thorndike and Woodworth ( 1901 ) found that students who learned Latin did not subsequently learn bookkeeping any better than students who had not learned Latin. They interpreted this finding as evidence for specific transfer—learning A did not transfer to learning B because A and B did not have specific elements in common. Modern research on problem-solving transfer continues to show that people often do not demonstrate general transfer (Mayer, 1992 ). However, it is possible to teach people a general strategy for solving a problem, so that when they see a new problem in a different context they are able to apply the strategy to the new problem (Judd, 1908 ; Mayer, 2008 )—so there is also research support for the idea of specific transfer of general principles.

Insight refers to a change in a problem solver’s mind from not knowing how to solve a problem to knowing how to solve it (Mayer, 1995 ; Metcalfe & Wiebe, 1987 ). In short, where does the idea for a creative solution come from? A central goal of problem-solving research is to determine the mechanisms underlying insight.

The search for insight has led to five major (but not mutually exclusive) explanatory mechanisms—insight as completing a schema, insight as suddenly reorganizing visual information, insight as reformulation of a problem, insight as removing mental blocks, and insight as finding a problem analog (Mayer, 1995 ). Completing a schema is exemplified in a study by Selz (Fridja & de Groot, 1982 ), in which people were asked to think aloud as they solved word association problems such as “What is the superordinate for newspaper?” To solve the problem, people sometimes thought of a coordinate, such as “magazine,” and then searched for a superordinate category that subsumed both terms, such as “publication.” According to Selz, finding a solution involved building a schema that consisted of a superordinate and two subordinate categories.

Reorganizing visual information is reflected in Kohler’s ( 1925 ) study described in a previous section in which a hungry ape figured out how to stack boxes as a ladder to reach a banana hanging above. According to Kohler, the ape looked around the yard and found the solution in a flash of insight by mentally seeing how the parts could be rearranged to accomplish the goal.

Reformulating a problem is reflected in a classic study by Duncker ( 1945 ) in which people are asked to think aloud as they solve the tumor problem—how can you destroy a tumor in a patient without destroying surrounding healthy tissue by using rays that at sufficient intensity will destroy any tissue in their path? In analyzing the thinking-aloud protocols—that is, transcripts of what the problem solvers said—Duncker concluded that people reformulated the goal in various ways (e.g., avoid contact with healthy tissue, immunize healthy tissue, have ray be weak in healthy tissue) until they hit upon a productive formulation that led to the solution (i.e., concentrating many weak rays on the tumor).

Removing mental blocks is reflected in classic studies by Duncker ( 1945 ) in which solving a problem involved thinking of a novel use for an object, and by Luchins ( 1942 ) in which solving a problem involved not using a procedure that had worked well on previous problems. Finding a problem analog is reflected in classic research by Wertheimer ( 1959 ) in which learning to find the area of a parallelogram is supported by the insight that one could cut off the triangle on one side and place it on the other side to form a rectangle—so a parallelogram is really a rectangle in disguise. The search for insight along each of these five lines continues in current problem-solving research.

Heuristics are problem-solving strategies, that is, general approaches to how to solve problems. Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) suggested three general problem-solving heuristics for moving from a given state to a goal state: random trial and error , hill climbing , and means-ends analysis . Random trial and error involves randomly selecting a legal move and applying it to create a new problem state, and repeating that process until the goal state is reached. Random trial and error may work for simple problems but is not efficient for complex ones. Hill climbing involves selecting the legal move that moves the problem solver closer to the goal state. Hill climbing will not work for problems in which the problem solver must take a move that temporarily moves away from the goal as is required in many problems.

Means-ends analysis involves creating goals and seeking moves that can accomplish the goal. If a goal cannot be directly accomplished, a subgoal is created to remove one or more obstacles. Newell and Simon ( 1972 ) successfully used means-ends analysis as the search heuristic in a computer program aimed at general problem solving, that is, solving a diverse collection of problems. However, people may also use specific heuristics that are designed to work for specific problem-solving situations (Gigerenzer, Todd, & ABC Research Group, 1999 ; Kahneman & Tversky, 1984 ).

Current and Future Issues in Problem Solving

Eight current issues in problem solving involve decision making, intelligence and creativity, teaching of thinking skills, expert problem solving, analogical reasoning, mathematical and scientific problem solving, everyday thinking, and the cognitive neuroscience of problem solving.

Decision Making

Decision making refers to the cognitive processing involved in choosing between two or more alternatives (Baron, 2000 ; Markman & Medin, 2002 ). For example, a decision-making task may involve choosing between getting $240 for sure or having a 25% change of getting $1000. According to economic theories such as expected value theory, people should chose the second option, which is worth $250 (i.e., .25 x $1000) rather than the first option, which is worth $240 (1.00 x $240), but psychological research shows that most people prefer the first option (Kahneman & Tversky, 1984 ).

Research on decision making has generated three classes of theories (Markman & Medin, 2002 ): descriptive theories, such as prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky), which are based on the ideas that people prefer to overweight the cost of a loss and tend to overestimate small probabilities; heuristic theories, which are based on the idea that people use a collection of short-cut strategies such as the availability heuristic (Gigerenzer et al., 1999 ; Kahneman & Tversky, 2000 ); and constructive theories, such as mental accounting (Kahneman & Tversky, 2000 ), in which people build a narrative to justify their choices to themselves. Future research is needed to examine decision making in more realistic settings.

Intelligence and Creativity