- Foreign Affairs

- CFR Education

- Newsletters

Climate Change

Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland December 5, 2023 Renewing America

- Defense & Security

- Diplomacy & International Institutions

- Energy & Environment

- Human Rights

- Politics & Government

- Social Issues

Myanmar’s Troubled History: Coups, Military Rule, and Ethnic Conflict

Backgrounder by Lindsay Maizland January 31, 2022

- Europe & Eurasia

- Global Commons

- Middle East & North Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa

How Tobacco Laws Could Help Close the Racial Gap on Cancer

Interactive by Olivia Angelino, Thomas J. Bollyky , Elle Ruggiero and Isabella Turilli February 1, 2023 Global Health Program

- Backgrounders

- Special Projects

China’s Stockpiling and Mobilization Measures for Competition and Conflict Link

Featuring Zongyuan Zoe Liu via U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission June 13, 2024

- Centers & Programs

- Books & Reports

- Independent Task Force Program

- Fellowships

- Oil and Petroleum Products

Academic Webinar: The Geopolitics of Oil

Webinar with Carolyn Kissane and Irina A. Faskianos April 12, 2023

- State & Local Officials

- Religion Leaders

- Local Journalists

The Rise in LGBTQ+ Hate and Democratic Backsliding

Event with Graeme Reid, Ari Shaw, Maria Sjödin and Nancy Yao June 4, 2024

- Lectureship Series

- Webinars & Conference Calls

- Member Login

Venezuela: The Rise and Fall of a Petrostate

- Venezuela is an example of a petrostate, where the government is highly dependent on fossil fuel income, power is concentrated, and corruption is widespread.

- Petrostates are vulnerable to what economists call Dutch disease, in which a government develops an unhealthy dependence on natural resource exports to the detriment of other sectors.

- Venezuela continues to grapple with economic and political hardship under President Nicolás Maduro, but U.S. sanctions relief in exchange for democratic reforms have sparked hope for a revival of the oil industry.

Introduction

Venezuela, home to the world’s largest oil reserves, is a case study in the perils of becoming a petrostate. Since it was discovered in the country in the 1920s, oil has taken Venezuela on an exhilarating but dangerous boom-and-bust ride that offers lessons for other resource-rich states. Decades of poor governance have driven what was once one of Latin America’s most prosperous countries to economic and political ruin.

In recent years, Venezuela has suffered economic collapse, with output shrinking significantly and rampant hyperinflation contributing to a scarcity of basic goods, such as food and medicine. Meanwhile, government mismanagement and U.S. sanctions have led to a drastic decline in oil production and severe underinvestment in the sector. But Caracas hopes that Washington’s decision to ease an array of sanctions on Venezuela’s oil and gas sector, including allowing U.S. oil giant Chevron to resume operations in the country, could signal a potential détente.

What is a petrostate?

- Latin America

- Geopolitics of Energy

- OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries)

Petrostate is an informal term used to describe a country with several interrelated attributes:

Daily News Brief

A summary of global news developments with cfr analysis delivered to your inbox each morning. weekdays., the world this week, a weekly digest of the latest from cfr on the biggest foreign policy stories of the week, featuring briefs, opinions, and explainers. every friday., think global health.

A curation of original analyses, data visualizations, and commentaries, examining the debates and efforts to improve health worldwide. Weekly.

- government income is deeply reliant on the export of oil and natural gas,

- economic and political power are highly concentrated in an elite minority, and

- political institutions are weak and unaccountable, and corruption is widespread.

Countries often described as petrostates include Algeria, Cameroon, Chad, Ecuador, Indonesia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Libya, Mexico, Nigeria, Oman, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.

What’s behind the petrostate paradigm?

Petrostates are thought to be vulnerable to what economists call Dutch disease , a term coined during the 1970s after the Netherlands discovered natural gas in the North Sea.

In an afflicted country, a resource boom attracts large inflows of foreign capital, which leads to an appreciation of the local currency and a boost for imports that are now comparatively cheaper. This sucks labor and capital away from other sectors of the economy, such as agriculture and manufacturing, which economists say are more important for growth and competitiveness. As these labor-intensive export industries lag, unemployment could rise, and the country could develop an unhealthy dependence on the export of natural resources. In extreme cases, a petrostate forgoes local oil production and instead derives most of its oil wealth through high taxes on foreign drillers. Petrostate economies are then left highly vulnerable to unpredictable swings in global energy prices and capital flight.

The so-called resource curse also takes a toll on governance. Since petrostates depend more on export income and less on taxes, there are often weak ties between the government and its citizens. Timing of the resource boom can exacerbate the problem. “Most petrostates became dependent on petroleum while, or immediately after, they were establishing a democracy, state institutions, an independent civil service and private sector, and rule of law,” says Terry Lynn Karl, a professor of political science at Stanford University and author of The Paradox of Plenty , a seminal book on the dynamics of petrostates. Leaders can use the country’s resource wealth to repress or co-opt political opposition.

How does Venezuela fit the category?

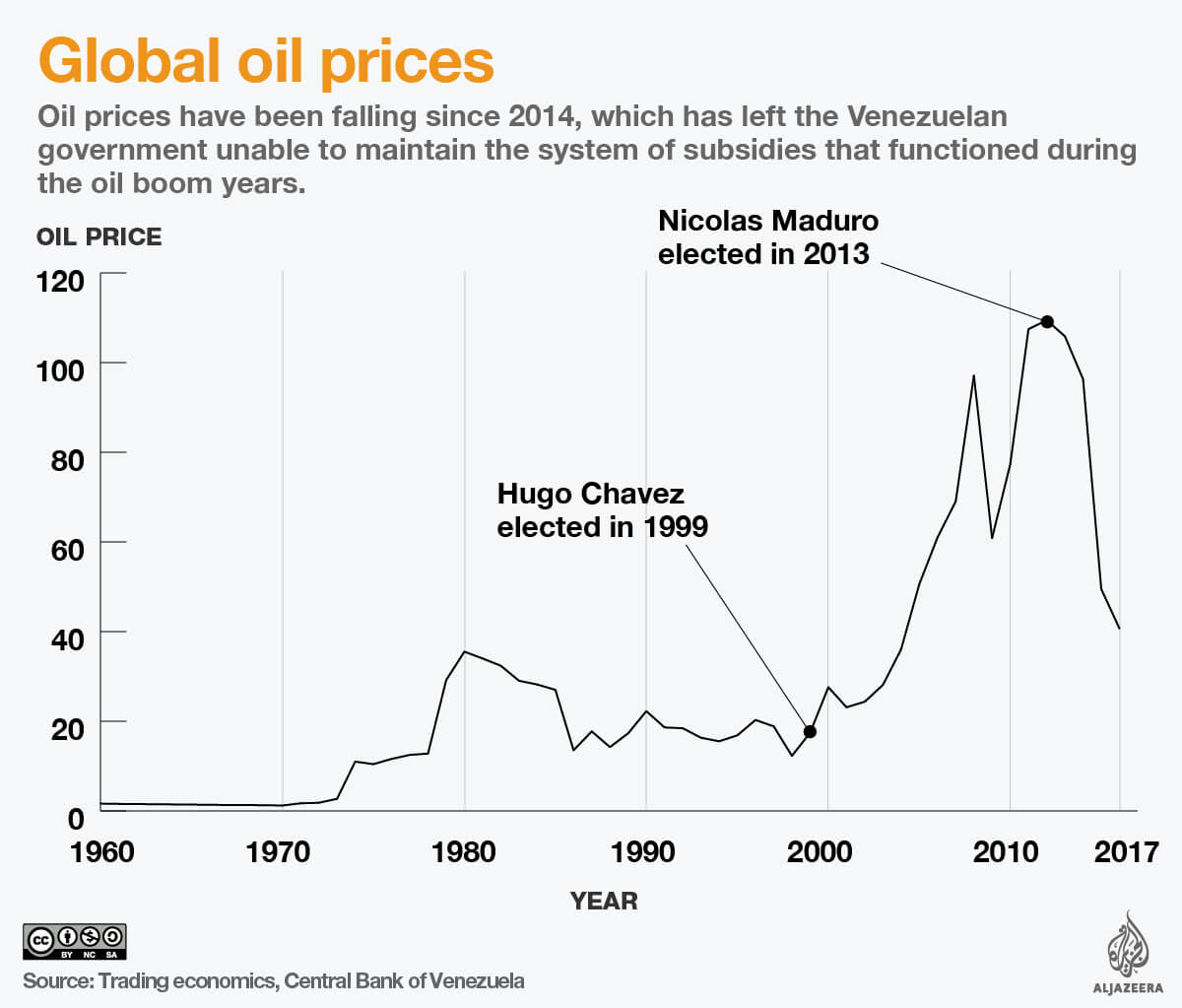

Venezuela is the archetype of a failed petrostate, experts say. Oil continues to play the dominant role in the country’s fortunes more than a century after it was discovered there. The oil price plunge from more than $100 per barrel in 2014 to under $30 per barrel in early 2016 sent Venezuela into an economic and political spiral, and despite rising prices since then, conditions remain bleak.

A number of grim indicators tell the story:

Oil dependence. In recent years, oil exports have financed almost two-thirds of the government’s budget. Estimates for 2024 place this figure slightly lower, at 58 percent .

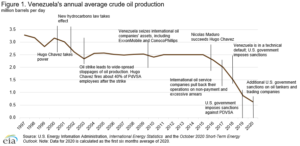

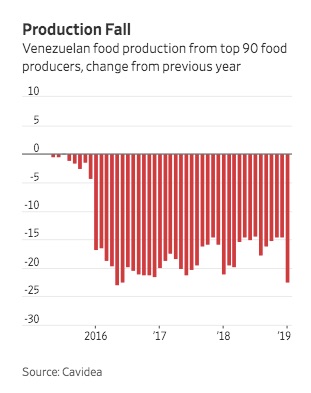

Falling production. Starved of adequate investment and maintenance, oil output has continued to generally decline, dropping by 2.5 percent in 2022 after increasing slightly the previous year. In 2020, it had reached its lowest level in decades .

Turbulent economy. Venezuela’s gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by roughly three-quarters [PDF] between 2014 and 2021. However, the economy grew by 8 percent in 2022 and 4 percent in 2023, and experts forecast additional growth of 4.5 percent in 2024.

Soaring debt. Venezuela has an estimated debt burden of $150 billion or higher .

Hyperinflation. Annual inflation skyrocketed to just over 130,000 percent in 2018, and though it has since slowed, it remained at 360 percent in 2023.

Growing autocracy. Over the last decade, President Nicolás Maduro and his allies have violated basic tenets of democracy to maintain power. This includes restricting internet access and arbitrarily prosecuting and detaining political opponents and critics.

These issues—coupled with international sanctions and the ongoing repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic—have fueled a devastating humanitarian crisis, with severe shortages of basic goods such as food, drinking water, gasoline, and medical supplies. According to a November 2022 survey, 50 percent of Venezuela’s 28 million residents live in poverty, though that is down from 65 percent the year before.

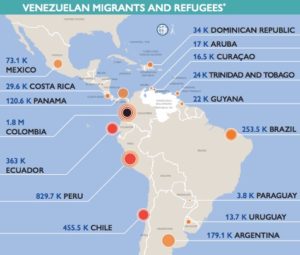

Since 2014, nearly eight million Venezuelan refugees have fled to neighboring countries and beyond, where some governments have granted them temporary residency. Venezuela’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs says that more than three hundred thousand Venezuelan migrants have returned home since September 2020.

How did Venezuela get here?

A number of economic and political milestones mark Venezuela’s path as a petrostate.

Discovering oil. In 1922, Royal Dutch Shell geologists at La Rosa, a field in the Maracaibo Basin, struck oil, which blew out at what was then an extraordinary rate of one hundred thousand barrels per day. In a matter of years, more than one hundred foreign companies were producing oil, backed by dictator General Juan Vicente Gómez (1908–1935). Annual production exploded during the 1920s [PDF], from just over a million barrels to 137 million, making Venezuela second only to the United States in total output by 1929. By the time Gómez died in 1935, Dutch disease had settled in: the Venezuelan bolívar had ballooned, and oil shoved aside other sectors to account for over 90 percent of total exports.

Reclaiming oil rents. By the 1930s, just three foreign companies—Gulf, Royal Dutch Shell, and Standard Oil—controlled 98 percent of the Venezuelan oil market. Gómez’s successors sought to reform the oil sector to funnel funds into government coffers. The Hydrocarbons Law of 1943 was the first step in that direction, requiring foreign companies to give half of their oil profits to the state. Within five years, the government’s income had increased sixfold.

Punto Fijo pact. In 1958, after a succession of military dictatorships, Venezuela elected its first stable democratic government. That year, Venezuela’s three major political parties signed the Punto Fijo pact , which guaranteed that state jobs and, notably, oil rents would be parceled out to the three parties in proportion to voting results. While the pact sought to guard against dictatorship and usher in democratic stability, it ensured that oil profits would be concentrated in the state.

OPEC. Venezuela joined Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia as a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960. Through the group, which would later include Qatar, Indonesia, Libya, the United Arab Emirates, Algeria, Nigeria, Ecuador, Gabon, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, and the Republic of Congo, the world’s largest producers coordinated prices and gave states more control over their national industries. That same year, Venezuela established its first state oil company, the Venezuelan Petroleum Corporation, and increased oil companies’ income tax to 65 percent of profits.

The 1970s boom . In 1973, a five-month OPEC embargo on countries backing Israel in the Yom Kippur War quadrupled oil prices and made Venezuela the country with the highest per-capita income in Latin America. Over two years, the windfall added $10 billion to state coffers, giving way to rampant graft and mismanagement. Analysts estimate that as much as $100 billion was embezzled between 1972 and 1997 alone.

PDVSA. In 1976, amid the oil boom, President Carlos Andrés Pérez nationalized the oil industry, creating state-owned Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) to oversee all exploring, producing, refining, and exporting of oil. Pérez allowed PDVSA to partner with foreign oil companies as long as it held 60 percent equity in joint ventures and, critically, structured the company to run as a business with minimal government regulation.

The 1980s oil glut. As global oil prices plummeted in the 1980s, Venezuela’s economy contracted and inflation soared; at the same time, it accrued massive foreign debt by purchasing foreign refineries, such as Citgo in the United States. In 1989, Pérez—reelected months earlier—launched a fiscal austerity package as part of a financial bailout by the International Monetary Fund . The measures provoked deadly riots. In 1992, Hugo Chávez, a military officer, launched a failed coup and rose to national fame.

Venezuela’s Chavez Era

Chávez’s Bolivarian revolution. Chávez was elected president in 1998 on a socialist platform, pledging to use Venezuela’s vast oil wealth to reduce poverty and inequality. While his costly “Bolivarian missions” expanded social services and cut poverty by 20 percent, he also took several steps that precipitated a long and steady decline in the country’s oil production, which peaked in the late 1990s and early 2000s. His decision to fire thousands of experienced PDVSA workers who had taken part in an industry strike in 2002–2003 gutted the company of important technical expertise. Beginning in 2005, Chávez provided subsidized oil to several countries in the region, including Cuba, through an alliance known as Petrocaribe. Over the course of Chávez’s presidency, which lasted until 2013, strategic petroleum reserves dwindled and government debt more than doubled [PDF].

Chávez also harnessed his popularity among the working class to expand the powers of the presidency and edged the country toward authoritarianism: he ended term limits , effectively took control of the Supreme Court, harassed the press and closed independent outlets, and nationalized hundreds of private businesses and foreign-owned assets, such as oil projects run by ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips. The reforms paved the way for Maduro to establish a dictatorship years after Chávez’s death.

Descent into dictatorship. In mid-2014, global oil prices tumbled and Venezuela’s economy went into free fall. As unrest brewed, Maduro consolidated power through political repression, censorship, and electoral manipulation. In 2018, he secured reelection in a race widely condemned as unfair and undemocratic . Nearly sixty countries, including the United States, subsequently recognized opposition figure Juan Guaidó, head of the National Assembly, as Venezuela’s interim leader.

What has been the impact of U.S. sanctions?

For almost two decades, Washington has imposed sweeping sanctions against Caracas, the most significant of which have blocked oil imports from PDVSA and prevented the government from accessing the U.S. financial system. Still, Venezuela has retained oil-trading partners, and analysts say that support from China, Cuba, Iran, Russia, and Turkey has helped keep the Maduro regime afloat.

In January 2021, Maduro and his allies took leadership of what was the last opposition-controlled power center in the government, the National Assembly, after claiming victory in legislative elections. The opposition, including Guaidó, boycotted the vote, alleging that it was fraudulent, a charge reaffirmed by the Joe Biden administration and other foreign governments and international bodies, including Canada, the European Union, and the Organization of American States . However, regional elections that November further cemented Maduro’s power and saw the fractured opposition win only three of twenty-three available governorships. After years of waning support, the opposition voted to remove Guaidó and dissolve his government in December 2022.

Meanwhile, U.S.-Venezuela relations have begun seeing signs of a thaw. In November 2022, in part to help offset rising global energy prices due to the war in Ukraine, the United States permitted U.S. oil giant Chevron to resume limited operations in the country. In exchange, the Maduro government and the opposition agreed to continue dialogue following a yearlong stalemate. The following October, Caracas agreed to a roadmap for a free and fair presidential election in 2024. Washington rewarded the move by further easing sanctions on Venezuela’s oil and gas sector, allowing it to export oil and gas products for six months But the government’s failure to meet conditions for a fair vote and the revival of a centuries-old territorial dispute with Guyana over control of the oil-rich Essequibo region have put the thaw at risk .

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Will U.S.-Venezuela Relations Thaw?

Is there a path away from the oil curse.

A country that discovers a resource after it has formed robust democratic institutions is usually better able to avoid the resource curse, analysts say. For example, strong institutions in Norway have helped the country enjoy steady economic growth since the 1960s, when vast oil reserves were discovered in the North Sea, Karl writes in her book. In 2024, officials project that the petroleum sector will account for just 24 percent of Norway’s GDP. Strong democracies with an independent press and judiciary help curtail classic petrostate problems by holding government and energy companies to account.

If a country strikes oil or another resource before it develops its state infrastructure, the curse is much harder to avoid. However, there are remedial measures that low-income and developing countries can try, provided they are willing. For instance, a government’s overarching objective should be to use the oil earnings in a responsible manner “to finance outlays on public goods that serve as the platform for private investment and long-term growth,” says Columbia University’s Jeffrey Sachs, an expert on economic development. This can be done financially, with broad-based investing in international assets, or physically, by building infrastructure and educating workers. Transparency is essential in all of this, Sachs says.

Many countries with vast resource wealth, such as Norway and Saudi Arabia, have established sovereign wealth funds (SWF) to manage their investments. SWFs manage more than $9 trillion worth of assets, and some analysts predict that figure will grow to nearly $13 trillion by 2025.

Analysts anticipate that a global shift from fossil fuel energy to renewables such as solar and wind will force petrostates to diversify their economies. Nearly two hundred countries, including Venezuela, have joined the Paris Agreement , a binding treaty that requires states to make specific commitments to mitigate climate change.

Economic diversification will be an especially difficult climb for Venezuela given the scale of its economic and political collapse over the last decade. The country would likely need to revitalize its oil sector before it could cultivate and develop other important industries. But this would take enormous investment, which analysts say would be hard to come by given Venezuela’s unstable political environment, trends in oil demand, and rising concerns about climate change.

Recommended Resources

Bloomberg’s Andreina Itriago Acosta and Nicolle Yapur lay out why recent U.S.-Venezuela talks can be seen as a step toward restoring Venezuela’s democracy .

For Americas Quarterly , Guillermo Zubillaga discusses the prospects of Venezuela’s opposition taking power in the 2024 elections.

This In Brief evaluates the effects of U.S. sanctions on Venezuela.

This 2023 report [PDF] by the Wilson Center discusses why negotiations between the government and opposition are important for resolving Venezuela’s prolonged political crisis.

For the Wall Street Journal , Kejal Vyas and Patricia Garip look at how Venezuela’s oil sector is polluting the environment .

Through interviews with Western oil companies, the Inter-American Dialogue explores what conditions would draw investors back to Venezuela’s collapsing oil sector.

- Economic Crises

- Authoritarianism

William Rampe and Rocio Cara Labrador contributed to this report. Will Merrow helped create the graphics.

More From Our Experts

How Will the EU Elections Results Change Europe?

In Brief by Liana Fix June 10, 2024

Iran Attack Means an Even Tougher Balancing Act for the U.S. in the Middle East

In Brief by Steven A. Cook April 14, 2024 Middle East Program

Iran Attacks on Israel Spur Escalation Concerns

In Brief by Ray Takeyh April 14, 2024 Middle East Program

Top Stories on CFR

China Strategy Initiative Link

via Council on Foreign Relations June 24, 2024

What Is the Extent of Sudan’s Humanitarian Crisis?

In Brief by Mariel Ferragamo and Diana Roy June 26, 2024

Does Iran’s Presidential Election Matter?

Expert Brief by Ray Takeyh June 25, 2024

What caused hyperinflation in Venezuela: a rare blend of public ineptitude and private enterprise

Academic Specialist, Latin America, The University of Melbourne

Disclosure statement

Michelle Carmody does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Melbourne provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Imagine going to the store and finding that nothing has a price tag on it. Instead you take it to the cashier and they calculate the price. What you pay could be twice as much, or more, than an hour earlier. That’s if there is even anything left in stock.

This is the economic reality that underpins Venezuela’s current “political crisis” – though in truth that crisis has been going on for years.

The government headed by Nicolás Maduro, who has presided over Venezuela since 2013, declared a state of emergency in 2016. That year the inflation rate hit 800%. Things have since gone from bad to worse.

By 2018 inflation was an estimated 80,000%. It’s difficult to say what the rate is now, but Bloomberg’s Venezuelan Cafe Con Leche Index , based on the price of a cup of coffee, suggests it is now about 380,000%.

About 3 million Venezuelans – a tenth of the population – have fled the country. This is the largest human displacement in Latin American history, driven by shortages of everything including food as well as the Maduro regime’s oppressive treatment of dissent .

Read more: Venezuela is fast becoming a 'mafia state': here's what you need to know

No wonder, then, that Maduro, who has just begun his second term as president, is now under considerable domestic and international pressure to call new elections.

So how did things get so bad? How did inflation become hyperinflation in Venezuela? And how do Venezuelans deal with it?

The cost of goods and the value of currency

What we pay for goods and services reflects not only their cost of production but also of the value of the currency we buy them in. If that currency loses value against the currency the goods are sold in, the price of those goods goes up.

By 2014 the value of Venezuela’s currency, the bolívar, and the prosperity of the Venezuelan economy, was highly dependent on oil exports. More than 90% of the country’s export earnings came from oil.

These export earnings had enabled the government headed by Hugo Chavez from 1999 to 2013 to pay for social programs intended to combat poverty and inequality. From subsidies for those on low incomes to health services, the government’s spending obligations were high.

Then the global price of oil dropped. Foreign demand for the bolívar to buy Venezuelan oil crashed. As the currency’s value fell, the cost of imported goods rose. The Venezuelan economy went into crisis.

The solution of Venezuela’s new president Nicolas Maduro, who succeeded Chavez in March 2013, was to print more money.

That might seem silly, but it can keep the economy moving while it gets over a hump caused by a short-term price shock.

The Venezuelan crisis, however, just got worse as the oil price continued to fall, compounded by other factors that reduced Venezuelan oil output. International investors began looking elsewhere, driving the value of the bolívar even lower.

Read more: Curious Kids: why don’t poorer countries just print more money?

In these conditions, printing more money simply made the problem worse. It added to the supply of currency, pushing the value down even further. As prices rose, the government printed more money to pay its bills. This cycle is what causes hyperinflation.

Playing the currency market

Circumstances like these quickly make saving money in the local currency nonsensical. To protect themselves, Venezuelans started to convert their savings into a more stable currency, like the US dollar. This lowered the value of the bolívar even further.

The government responded by issuing currency controls. It set a fixed exchange rate, to stop the official value of the bolívar dropping against the US dollar, and made it difficult to actually get permission to exchange bolívares into US dollars. The idea was to stabilise the currency by effectively shutting down all currency transactions.

US dollars were still available on the black market, however. This meant going to any number of operators on the streets of downtown Caracas or asking a friend to hook you up. As the crisis deepened, more and more Venezuelans looked to switch their bolívares into US dollars.

This increasing demand meant the black market price for greenbacks rose, creating a difference between the official exchange rate (set by the government) and the unofficial going rate.

With this came new opportunities. In 2014 reports emerged that groups of middle-aged women were crossing the border to use ATMs in Colombia. They could withdraw funds from their Venezuelan accounts as US dollars at the official rate. They could then cross back into Venezuela and exchange the dollars for bolívares at the unofficial rate, making a tidy profit. Government officials able to exchange bolívares for US dollars within Venezuela had their own version of this practice.

This pushed the price of US dollars up, and that of bolívars down, even more. As the crisis deepened increasing numbers of ordinary Venezuelans began to engage in the unofficial currency market.

Sometimes this took the form of taking subsidised Venezuelan goods like food across the border to sell. This earned the sellers foreign currency, but it also exacerbated shortages of goods within the country, driving prices up even further.

This does not mean Venezuela’s currency crisis is the fault of ordinary Venezuelans. Illegal economic activity is largely a coping mechanism, a bellwether of the actual economy’s ability to provide for people. When a government fails its responsibilities, it should be no surprise that people protect themselves through unofficial currency trading. This is exactly what big international investors do all the time, albeit through more official channels.

Cannot be trusted

By August 2018 the Venezuelan currency was worth so little that it was more prudent to use cash for toilet paper rather than buy toilet paper.

The government tried to get on top of this situation by issuing a currency devaluation. Maduro devalued the bolívar by 95%, the largest currency devaluation in contemporary world history. He also tied the new currency to the price of oil, an economic experiment designed to show the Venezuelan economy had solid foundations.

By bringing the bolívar’s value into line with the reality of what people actually thought it was worth, and showing it was backed by something valuable, oil, Maduro’s government hoped Venezuelans would believe in their own currency and not exchange it for dollars. This would help stabilise the economy overall.

But within weeks of the devaluation it was clear ordinary Venezuelans had not been convinced.

They had no reason to be, given the government was not addressing other issues, such as policies contributing to low productivity across the economy. The government’s increasing authoritarianism, including interfering with the constitution and elections, also signalled it was not to be trusted.

Read more: Is authoritarianism bad for the economy? Ask Venezuela – or Hungary or Turkey

Hyperinflation is a very difficult hole out of which to climb. Very few economies ever experience it, and it’s hard to stop it without massively cutting government spending.

It is easy, then, to see why millions of Venezuelans responded by dealing in the black market or taking their savings, and themselves, out the country altogether.

As the political crisis in the country deepens, Venezuelans will have to continue to seek ways to allow them to survive the storm any way they can.

- Nicolás Maduro

- Currency crisis

- Hyperinflation

- Currency trading

- Venezuela crisis

PhD Scholarship

Senior Lecturer, HRM or People Analytics

Senior Research Fellow - Neuromuscular Disorders and Gait Analysis

Centre Director, Transformative Media Technologies

Postdoctoral Research Fellowship

Ferraris and Hungry Children: Venezuela’s Socialist Vision in Shambles

After years of extreme scarcity, some Venezuelans lead lives of luxury as others scrape by. The nation of grinding hardship has increasingly become one of haves and have-nots.

Chefs preparing a meal at Altum, a restaurant suspended on a crane over Caracas, the Venezuelan capital. Credit...

Supported by

- Share full article

By Isayen Herrera and Frances Robles

Photographs by Adriana Loureiro Fernandez

Isayen Herrera reported and Adriana Loureiro Fernandez photographed from Caracas, Venezuela. Frances Robles reported from Key West, Fla.

- March 21, 2023

CARACAS, Venezuela — In the capital, a store sells Prada purses and a 110-inch television for $115,000. Not far away, a Ferrari dealership has opened, while a new restaurant allows well-off diners to enjoy a meal seated atop a giant crane overlooking the city.

“When was the last time you did something for the first time?” the restaurant’s host boomed over a microphone to excited customers as they sang along to a Coldplay song.

This is not Dubai or Tokyo, but Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, where a socialist revolution once promised equality and an end to the bourgeoisie.

Venezuela’s economy imploded nearly a decade ago , prompting a huge outflow of migrants in one of worst crises in modern Latin American history. Now there are signs the country is settling into a new, disorienting normality, with everyday products easily available, poverty starting to lessen — and surprising pockets of wealth arising.

That has left the socialist government of the authoritarian President Nicolás Maduro presiding over an improving economy as the opposition is struggling to unite and as the United States has scaled back oil sanctions that helped decimate the country’s finances.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Advertisement

Venezuela’s worst economic crisis: What went wrong?

Country sitting on world’s biggest oil reserves is now region’s poorest performer in terms of GDP growth per capita.

Venezuela is experiencing the worst economic crisis in its history, with an inflation rate of over 400 percent and a volatile exchange rate.

Heavily in debt and with inflation soaring, its people continue to take to the streets in protest.

Keep reading

Nike stock plunges on surprise forecast of drop in sales, us supreme court weakens federal regulators in boost for business, tension and stand-offs as south africa struggles to launch coalition gov’t, mongolians vote amid anger over corruption, sluggish economy.

President Nicolas Maduro announced the highest increase in the minimum wage ordered by him – 65 percent of the monthly income, and recently announced the creation of a new popular assembly with the ability to re-write the constitution.

International concern raised, with Chile and Argentina among the countries expressing worry. The Venezuelan opposition says the move further weakens the chances of holding a vote to remove Maduro.

But backing has come from regional leftist allies including Cuba. Bolivia’s President Evo Morales said Venezuela had the right to “decide its future… without external intervention.”

The country sits on the world’s largest oil reserves, but, over the past decade, it has been the region’s poorest performer in terms of growth of GDP per capita.

Since 2014 the government has not made any economic data available making it difficult to track.

But what went wrong?

1) What is the state of Venezuela’s economy today?

Venezuela depends heavily on its oil. It has the largest oil reserves in the world which, in 2014, had 298 billion barrels of proved oil reserves.

Oil revenue has sustained Venezuela’s economy for years. During the presidency of Hugo Chavez, the price of oil reached a historic high of $100 a barrel.

The billions of dollars in revenue were used to finance social programmes and food subsidies.

But when the price of oil fell, those programmes and subsidies became unsustainable.

READ MORE- Venezuela: What is happening?

The government is also running out of cash. According to the Central Bank of Venezuela, the country has $10.4bn in foreign reserves left, and it is estimated to have a debt of $7.2bn.

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures, in 2016, the country had a negative growth rate of minus 8 percent, an inflation rate of 481 percent and an unemployment rate of 17 percent that is expected to climb to 20 percent this year.

Currency controls have limited imports, putting a strain on supply.

The government controls the price of basic goods, this has led to a black market that has a strong influence on prices too.

The most recent report by CENDAS (Centre for Documentation and Social Analysis) indicates that in March 2017 a family of five needed to collect 1.06 million bolivars to pay for the basic basket of goods for one month, that includes food and hygiene items, as well as spending on housing, education, health and basic services.

The cost of that basket rosed by 15.8 percent that is an increase of 424 percent compared to 2016.

2) Shortages of food and medicines

During the rule of Hugo Chavez, the price of key items, food and medicines were reduced. Products became more affordable but they were below the cost of production.

Private companies were expropriated, and to stop people from changing the national currency into dollars, Chavez restricted the access to dollars and fixed the rate.

When it became unprofitable for Venezuelan companies to continue producing their own products, the government decided to import them from abroad, using oil money.

But oil prices have been falling since 2014, which has left the economic system unable to maintain the system of subsidies and price controls that functioned during the oil boom years.

We are facing a food crisis by Jose Guerra, analyst

The inability to pay for imports with bolivares coupled with the decline in oil revenues has led to a shortage of goods.

The state has tried to ration food and set their prices, but the consequence is that products have disappeared from shops and ended up in the black market, overpriced.

As many as 85 of every 100 medicines are missing in the country. Shortages are so extreme that patients sometimes take medicines ill-suited for their conditions, doctors warn.

Given the long litany of woes, some analysts think there are two options before Maduro’s government: to default on its debt or to stop importing food.

“For those of us who work with a normal wage, we can barely eat, it’s like a war situation [we eat what we can get and what we can find] because the price of food is astronomical,” Leonardo Bruzal, a Venezuelan citizen, told Al Jazeera.

Many Venezuelans search for food, occasionally opting to eat wild fruit or rubbish. “We are facing a food crisis,” analyst Jose Guerra explained to Al Jazeera.

3) Hyperinflation

Venezuela has established different exchange rate systems for its national currency, the bolivar.

One rate was established for what the government determines to be “essential goods”, other for “non-essential goods” and another one for people.

The two primary rates overvalue the bolivar, but the black market values the bolivar at near worthless.

This has generated a situation in which Venezuelans are opting for dollars instead of bolivares.

- The government maintains a trade around 710 bolivares per US dollar.

- At 10 under Venezuela’s other official rate

- But the black-market rate has risen to 4,283 bolivars for one dollar.

The government has also increased the number of bolivares available in the streets, as the money in circulation has not been enough to pay for basic goods that today cost a lot more. This has stoked fears of hyperinflation.

On April 30, Maduro announced a 34.42 percent increase in the total salary.

Faced with this new wage increase – the 15 during Maduro’s mandate – economists reacted saying that this measure is insufficient to deal with inflation, which they warn is going to worsen with this setting.

|

|

4) Venezuela before Chavez

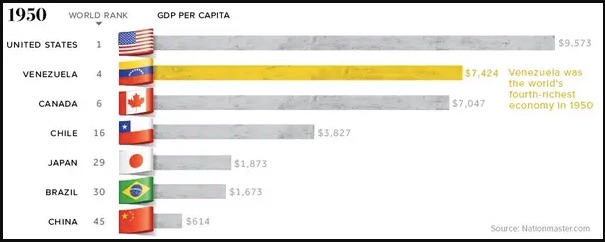

Between 1900 and 1920, Venezuela’s per capita GDP had grown at a rate of barely 1.8 percent. Between 1940 and 1948 it grew at 6.8 percent per annum.

By the 1960s and the 1970s, the governments in Venezuela were able to maintain social harmony by spending fairly large amounts on public programmes.

In 1970, Venezuela had become the richest country in Latin America, and one of the 20 richest countries in the world, with a per capita higher that Spain, Greece and Israel, Ricardo Hausmann explains in his book Venezuela Before Chavez: Anatomy of an Economy Collapse.

Venezuelan workers were known for enjoying the highest wages in Latin America, a situation that dramatically changed when oil prices collapsed during the 1980s.

The economy contracted and inflation levels rose, remaining between 6 and 12 percent from 1982 to 1986.

The inflation rate surged in 1989 to 81 percent, the same year the capital city of Caracas experienced rioting during the Caracazo following the cuts in government spending and the opening of markets by the then president, Carlos Andres Perez.

Venezuela’s GDP went from -8.3 percent in 1989 to 4.4 percent in 1990, and 9.2 percent in 1991. However, wages remained low and unemployment high among Venezuelans.

By the mid-1990s under Caldera, Venezuela saw annual inflation rates of 50-60 percent, and an inflation rate of 100 percent in 1996, three years before Chavez took office.

The number of people living in poverty rose from 36 percent to 66 percent in 1995 with the country suffering a severe bank crisis.

When Chavez first took office as president in 1999, the country was not an economic model: almost half the population was below the country’s poverty line.

However, the country was an affluent country and the government finances were in tolerably good shape.

|

|

- How It Started

- The Policy Circle Team

- Civic Leadership Engagement Roadmap

- In The News

- 2022 Annual Report & Stories of Impact

- Join Our Community

- Join The Policy Circle: Invest in Your Future

- The Conversation Blog

Socialism: A Case Study on Venezuela

In the 1950s, Venezuela was the fourth wealthiest country in the world. Today, Venezuela is poorer than it was prior to the 1920s, its infrastructure is deteriorating, and its economy has been shrinking since the turn of the century. Hyperinflation (out of control price increases) has left the currency worthless and made it almost impossible for Venezuelans to afford basic necessities. Millions have fled the country’s inhospitable conditions. How did the country go from having a GDP on par with that of the United States, New Zealand, and Switzerland to having almost 90% of the population living in poverty?

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Listen to The Civic Leader Podcast for an audio version of this brief.

To begin, listen to our podcast of Co-founder, Sylvie Légère, hosting a Conversation Call with special guests to discuss this newsworthy topic.

- Venezuela Conversation Call - April 9. 2019

In addition, listen to Angela Braly, Co-founder of The Policy Circle, interviewing Emilio Pacheco, who was born and raised in Venezuela where he lived until 1987, about his experiences.

Introduction

This brief takes a closer look at Venezuela’s past and present social, political, and economic circumstances, the role socialist policies played, and how this relates to conversations within our own government. Understanding the history of such an evolution is an important way to keep similar tendencies from reaching other shores, including our own.

Case Studies: On the Ground in Venezuela

In what was once Latin America’s richest nation, over 75% of Venezuelans are living in extreme poverty . According to a September 2021 report from the National Survey of Living Conditions, created in 2014 to make up for the absence of official data, the percentage of Venezuelans living in extreme poverty rose from 67.7% to 76.6%. This is a reversal of the improvement in previous years after the government started cash transfers and relaxed price controls. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the crisis in Venezuela that had already been ongoing for years; before the pandemic, the UN World Food Programme estimated one-third of Venezuelans struggled to get enough food to meet the minimum nutritional requirements.

The U.S. State Department announced in September 2021 that it was sending $247 million in humanitarian assistance and $89 million in economic and development assistance to aid “Venezuelans in their home country and Venezuelan refugees, migrants, and their host communities in the region.” This includes $120 million from the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration; and $216 million through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), bringing total U.S. humanitarian, economic, development, and health assistance for the Venezuela crisis to more than $1.9 billion since 2017. This includes :

- Food assistance;

- Emergency shelter;

- Access to health care, water, sanitation, and hygiene supplies;

- COVID-19 support;

- Protection for vulnerable groups including women, children, and indigenous people;

- Assistance to democratic actors within Venezuela;

- Integration support for communities that host Venezuelan refugees and migrants, “including development programs to expand access to education, vocational opportunities, and public services.”

As of early 2022, more than 7 million Venezuelans in Venezuela are in critical need, and almost 6 million have fled to 17 countries across the region.

Why it Matters

What separates Venezuela from similar nations is its history of centralizing power, its government overreach, and its inability to “stabilise external and fiscal accounts.” By imposing price controls, expropriating private property, and conducting large-scale industry nationalization, the Venezuelan government wrecked the economy and eliminated the economic freedom of its citizens. The “dismantling of democratic checks and balances, and sheer incompetence” led to Venezuela’s collapse .

The media have assigned blame for Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis on causes such as falling oil prices. However, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Kuwait are also petrostates that saw their incomes fall when oil prices dropped, but emerged from recession with their economies intact. Additionally, although President Maduro has blamed the U.S. and its imposed sanctions , none of these sanctions were broad enough to inflict the type of damage Venezuela is currently suffering .

The regimes of Presidents Hugo Chavez and Nicolás Maduro decimated the country through “relentless class warfare and government intervention in the economy.” Maintaining basic freedoms and remaining committed “to the rule of law, limited government, and checks and balances” is what separates true democratic nations from Venezuela, and what the rest of the world must remember to adhere to .

Putting it in Context

Oil boom (1940s-1970s).

Geologists from Royal Dutch Shell struck oil in the northeast region of Venezuela in 1922. Annual production during the 1920s increased from about 1 million barrels to 137 million, putting Venezuela second only to the U.S. in total oil output . By the mid-1930s, oil totaled 90% of exports and was pushing out all other economic sectors. However, foreign companies, including Royal Dutch Shell, controlled 98% of Venezuelan oil. In response, the Venezuelan government enacted a law in 1943 that required “foreign companies to give half of their oil profits to the state. Within five years, the government’s income had increased sixfold.”

Venezuela’s prominence in the oil market and government oversight of the industry was a constant throughout the 1940s and 1950s. In 1960, Venezuela became a founding member of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) , through which the world’s largest oil producers coordinate prices to give states more control. Joining OPEC substantially benefited Venezuela during the 1970s, when an OPEC embargo during the Yom Kippur War caused oil prices to soar. Venezuela’s per capita income quickly became the highest of any country in Latin America as oil revenues quadrupled. In 1976, President Perez created the state-run oil company Petroleos de Venezuela, S.A (PDVSA) to supervise the oil industry .

Oil Bust (1980s-2000s)

In the 1980s, global oil prices plummeted due to crude oil surpluses after the 1970s energy crisis. As Venezuela was almost entirely reliant on oil, the price crash brought Venezuela’s economy down with it . In 1989, President Perez implemented an austerity package as part of an International Monetary Fund bailout. Riots and strikes ensued, followed by an attempted coup by Hugo Chavez in the early 1990s. Although unsuccessful in his initial overthrow attempt, Chavez rose to fame and was elected president in 1998.

Once in power , Chavez raised oil income taxes on foreign companies in Venezuela. He promised to use the revenues to expand government-run welfare programs, hire more government workers, raise the minimum wage, and redistribute land. Meanwhile, the state-run oil industry faltered due to the control structure of the government. After a strike in 2002-2003, Chavez fired thousands of PDVSA workers and replaced them with loyal supporters with little technical and managerial expertise. Foreign investors and oil firms disliked the government interference, lost faith in PDVSA, and stopped operations .

Collapse (2000s-Present)

In an attempt to gain more control over the economy, President Chavez went on a nationalization spree in the 2000s that pushed out all private enterprise, starved industries of technical expertise and investment, and sent government-controlled institutions into a downward spiral. Exchange rate controls and price controls “broke the basic link between supply and demand, creating surreal economic distortions.” For more on supply and demand, markets, and price controls, see The Policy Circle’s Free Enterprise & Economic Freedom brief.

This suffocated private enterprise . Price controls prevented private businesses from setting their own prices, making it nearly impossible to make a profit. Both foreign- and domestically-owned companies stopped investing in Venezuela, and new businesses did not replace them due to red tape, corruption, and fear their private property was not secure. In 2011, Latin America received over $150 billion in foreign investment ; Venezuela only accounted for $5 billion of this amount, while neighboring Brazil received $67 billion. Investment has only declined further since then; in 2019, Brazil received $72 billion, Colombia $14 billion, and Chile $11 billion, while Venezuela received less than $1 billion.

Chavez garnered strong relationships with countries such as China, Russia, and Cuba to endure the inevitable disasters of his policies. He frequently announced new government programs to deliver free or heavily discounted goods that resulted from these relationships, such as refrigerators and cars, to the poorest in the nation. These efforts kept the worst case scenario of Venezuela’s impending crisis at bay, and also continuously won Chavez popular sentiment around election times. This stopped when Chavez died, reportedly of cancer, in 2013.

Chavez’s vice president, Nicolas Maduro, assumed the presidency in 2014, but this did not change the economy’s trajectory. Oil prices tumbled, inflation reached over 50 percent, prompting Maduro to cut public spending. By mid-2016, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans were protesting . Maduro’s response was to crack down on dissent.

For more on Venezuela’s history, Hugo Chavez, and Nicolás Maduro, watch The Collapse of Venezuela, Explained:

The Role of Government

Venezuela’s situation was the product of years of government policies and economic mismanagement. The clear signs of trouble came from a charismatic leader who promised the nation that government was a solution to their woes, and made the country dependent on one resource while shutting down competition, diversity of opinion, and debate. It might seem strange that such a chain of events could happen without notice, but the slow dissolution of democracy often happens while many blindly laud the intermediary steps.

Bolivarian Revolution

Chavez identified with the Venezuelans who suffered under the IMF-backed austerity measures during the late 1980s and mid 1990s , and his campaign promise was to use his power to distribute public and private oil revenues to the poor . Chavez spent these funds on social services and welfare programs . The social programs, called “ misiones ,” delivered basic services for education, health, employment, and food. There was practically no limit to these welfare programs; one year, the government handouts included approximately 200,000 homes.

Nationalization

Chavez’s economic model intended to have community enterprises working alongside the private sector, but government overreach meant national agencies, co-ops, and state industries comprised the bulk of the economy . Starting in 2007, the government used oil revenue to buy the largest electricity and telecommunications companies. It also seized the largest agricultural supplies company, the largest steel producer, glass producer, and the three largest cement industries.

These produced little return, and co-ops in particular often “ wound up in the hands of incompetent and corrupt political cronies .” Additionally, private enterprises suffered a number of state-imposed regulations and high taxes. International airlines stopped servicing flights to Venezuela, and businesses including General Motors, Clorox, and Kellogg’s, at risk of having their assets taken by the state, fled the inhospitable economic conditions . The World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 report listed Venezuela as one of the worst countries in which to do business, ranking it 188th out of 190 countries.

Freedom of Speech

Government oversight of the media and efforts to stop coverage of the opposition have escalated in recent years. The government has threatened news outlets that cover the opposition, shut down radio stations, raided television channel offices, and blocked websites. A number of international journalists have been arrested and deported ; even veteran Univision News anchor Jorge Ramos was detained during any interview with President Maduro. In May 2021, government forces seized the headquarters of the newspaper El Nacional after the Supreme Court ordered it to pay defamation damages (the Supreme Court has been accused of lacking judicial independence ). Additionally, since the COVID-19 state of emergency was enacted, many people sharing or publishing information on social media that questions officials or policies are charged.

Freedom House , an international organization that analyzes challenges to freedom, ranks Venezuela as “not free” in terms of political rights and civil liberties. Article 57 of Venezuela’s 1999 constitution guarantees freedom of expression and article 51 guarantees the right to access public information. However, the 2004 Law on Social Responsibility in Radio, Television, and Electronic Media bans any content that could “’incite or promote hatred,’” or “’disrespect authorities.’” As in other authoritarian countries, in Venezuela there is no protection for either citizens or the media to speak out against the government.

Suppression of Opposition

Many protests have been in response to government attempts to consolidate power . In 2015, the opposition party gained a two-thirds majority in Venezuela’s congress, the National Assembly. President Maduro then stripped the congress of its constitutional powers and replaced it with a Constituent Assembly packed with legislators loyal to Maduro’s regime. Maduro also declared the assembly’s Supreme Court appointments illegal, and replaced the Supreme Court with a parallel Supreme Tribunal of Justice, also packed with new magistrates that Maduro trusted.

“Free and Fair Elections”

Suspicious activity surrounded the 2018 Venezuelan presidential election . In the months leading up to the election, Maduro blocked opposition parties from participating or campaigning and arrested opposition candidates.

After voting, many people visited “ Red Spots ,” pro-government booths where they could receive government subsidized food boxes, and give “their names to workers who were keeping lists of those who had voted.” Although workers claimed there was no effort to “link a pro-Maduro vote to future food deliveries,” one woman said she felt “compelled to vote for Mr. Maduro” and feared she would lose her government job if she did not give her name at the Red Spot.

The results revealed Maduro had received 5.8 million votes (for comparison, he received 7.5 million votes in the 2013 election after Chavez’s death). His main rival Henri Falcón, who ran even though fellow opposition members called for an election boycott, received 1.8 million votes. Maduro claimed victory, but the organization Observación Ciudadana (Citizen Observation) and several international organizations denounced the results, listing cases of coercion, intimidation, and the fact that only 46% of Venezuelans voted on election day . For the 3 previous presidential elections in 2006, 2012, and 2013 , between 70 and 80 percent of the population voted .

To understand more about how Venezuela’s 2018 elections violated Venezuelan Law and internationally recognized standards, take a look at this infographic .

Current Challenges

The oil curse.

How did the nation that is home to the world’s largest oil reserves find itself in its current situation, so different from that of Saudi Arabia with the second largest oil reserves? According to political scientist Michael Ross , part of Venezuela’s crisis stems from becoming dependent on its most abundant resource: oil.

Using oil revenues for social change continuously deepened the dependence on the resource. There was little concern when oil prices were high in the mid-2000s, but prices fell in 2014 and Venezuela no longer has the funds to import what it does not produce at home. For this reason, welfare programs have been cut back, including government food handouts called CLAP boxes . In 2018, one researcher at the University of Venezuela claimed the boxes supplied about half of Venezuelans’ food requirements, and noted that the boxes dropped from 16 kilograms in January to 11 kilograms in May.

Chavez “did little to improve how Venezuela actually makes money . He paid no attention to diversifying the economy in domestic production outside of the oil sector .” Instead of relying on an entrepreneurial economy to produce a variety of goods and services to generate wealth, Chavez’s policies made citizens dependent on one commodity.

Oil revenues allowed Venezuela to import goods from abroad, but when oil revenues declined, Venezuela could no longer import the goods it did not produce itself. The scarcity of goods drove prices up, resulting in massive inflation. The price controls under President Chavez made necessities more affordable, but it was no longer profitable for businesses to make them. As a result, people were forced to turn to the government for handouts or to the black market .

President Maduro repeatedly increased the minimum wage in an attempt to combat inflation. In August of 2018, a 3000% increase equated to about $20 a month. This had almost no effect ; almost 90% of Venezuela’s population lived in poverty and prices were doubling on average every 19 days by the end of 2018 .

As the economy crumbled, education became a luxury. Students went to school primarily to receive the state-sponsored meals , but the buildings lack water and electricity . Each start of the school year, thousands of teachers do not show up to classes, having opted for different jobs that earn slightly more money or trying their luck abroad . This video from the Washington Post illustrates the enrollment and staffing troubles in the country that were prevalent before COVID-19. UNICEF reported 6.9 million students in Venezuela missed almost all classroom instruction between March 2020 and February 2021.

Post-secondary education is also suffering. Simon Bolivar University , dubbed Venezuela’s “University of the Future,” was government-funded since it opened in 1970, but alumni living abroad have been financing the university with private donations and teaching classes via Skype. Professors can only expect to earn the equivalent of $25 per month, prompting many to flee the country. Over 430 faculty and staff members left the university between 2015 and 2017 .

Education is not the only sector experiencing brain drain; over 20,000 doctors have fled Venezuela’s inhospitable conditions since 2014. Medical professionals have been attacked by patients’ relatives, frustrated by the supply shortage and machine and infrastructure failures ranging from power outages to water shortages. Across the country, hospitals face shortages of basic medicines such as those to control hypertension or diabetes, and high-cost medicines for cancer, Parkinson’s and multiple sclerosis are no longer imported. Treatments such as organ donations and transplants stopped in 2017.

The 1996 Constitution guaranteed the right to health as “ an obligation of the State ,” but the State has instead reduced funding, silenced practitioners, and censored health system publications. The government spends about 1.5% of GDP on healthcare, which is 75% lower than the world standard .

In 2015, Venezuela’s Health Ministry “stopped publishing weekly updates on relevant health indicators.” When health minister Antonieta Caporale briefly resumed updates in 2017, she was immediately fired. The statistics revealed that between 2016 and 2017, maternal mortality rose 65% and infant mortality rose 30%. Tuberculosis, diphtheria, measles, and malaria are also creating emergency situations, and disease is accompanied by widespread malnutrition. According to WHO standards, malnutrition among children under the age of 5 in Venezuela has reached “crisis level.” A university study found that, on average, almost two-thirds of Venezuelans surveyed lost about 25 pounds in 2017. ( Human Rights Watch , CEPAZ ). Venezuelans called this the “Maduro Diet,” as noted in this poignant letter .

The situation has not improved through the COVID-19 pandemic; Monitor Salud , an NGO, reported 83% of hospitals have insufficient or no access to personal protective equipment, and 95% lack sufficient cleaning supplies. Estimates indicate only about a quarter of the population is fully vaccinated.

Refugee Crisis

Colombia, Venezuela’s neighbor to the west, is absorbing most of those fleeing; although Colombia closed the border with Venezuela to try to stem the spread of the coronavirus, in February 2021, Colombia’s President Iván Duque announced the government would “provide temporary legal status to the more than 1.7 million Venezuelan migrants who have fled to Colombia in recent years.” Hundreds of thousands more pass through Colombia on their way to other countries including Peru, Chile, and Ecuador. Venezuelans now need a passport or visa to travel to other Latin American countries, when they previously only needed national identity cards. This adds insult to injury as passports are difficult to obtain given “ paper shortages and a dysfunctional bureaucracy .”

See more about how Colombia is handling this refugee crisis here:

Infrastructure

Intermittent power outages are a regular occurrence, but a massive outage that affected 22 of Venezuela’s 23 states in early March 2019 revealed the severity of the state of Venezuela’s energy infrastructure. Pro-government officials blamed Venezuela’s opposition party, claiming they had sabotaged Venezuela’s hydroelectric Guri Dam as part of an “ electricity war ” directed by the U.S . Energy experts, power sector contractors, and employees from the government energy company attributed the problems to “years of underinvestment, corruption and brain drain.” Skilled operators “had long left the company because of meager wages and an atmosphere of paranoia.”

The fallout has only exacerbated the suffering of the Venezuelan people . Looters started ransacking businesses for food and supplies. Gas stations could not pump fuel, causing many to turn to the black market for gasoline in “a country that subsidizes fuel to the point that it is nearly free.” According to Julio Castro of the organization Doctors for Health, at least 20 people died in public hospitals due to the outages; damaged or drained back-up generators could not keep machines required for dialysis, incubators, and artificial ventilation running.

These photos from The Guardian illustrate the effect of the blackout in Caracas.

During the first week of February 2019, international aid reached the Colombian and Brazilian borders. President Maduro ordered troops to barricade bridges at the borders to prevent aid from entering . Over 300 low-ranking soldiers fled their posts that weekend, but they are a small fraction of the 200,000 troops that remained loyal to Maduro and refused to let the trucks filled with food and medicine cross the border . Listen to this NY Times podcast on the humanitarian aid debacle in February 2019.

Maduro repeatedly denied the extent of the crisis in Venezuela, and said any aid efforts from the U.S. or other countries were “ part of a hostile foreign military intervention .” At the end of March 2019, however, Maduro reached an agreement with the international Red Cross to deliver aid. The first shipment reached Venezuela in mid-April. By September 2019, the aid was only making small improvements and shortages in medicines still persist. Over the summer of 2020, Venezuela’s opposition party reached an aid agreement with the Pan American Health Organization, specifically to help Venezuela respond to the pandemic, but Human Rights Watch reported in December 2020 that Venezuelan authorities were “freezing bank accounts, issuing arrest warrants, and raiding offices” or humanitarian groups operating in the country.

International Entanglement

Despite the controversy surrounding the 2018 election controversy, but Mexico, Turkey, Iran, Bolivia, Nicaragua, China, and Russia continue to recognize the Maduro regime . China in particular has offered technical assistance to help restore the country’s electrical grid. Additionally, China and Russia vetoed a United Nations Security Council vote in February to condemn the May 2018 elections and call for international humanitarian aid for Venezuela .

Russia and Venezuela have a long history in the oil industry. Since 2015, Rosneft, the Russian state-controlled oil firm, has increased its loans to Venezuela and its shareholder stakes in a joint venture with PDVSA. A Reuters investigation uncovered documents revealing that equipment is scarce, oil output is far lower than projected, and there is a “$700 million hole in the balance sheet of the joint venture.” Still, Venezuela buys Russian weapons , which gives Russia an incentive to stand by its ally and even provide military support . However, “Russian banks, grain exporters, and even weapons manufacturers have all curtailed business with Venezuela .”

Cuba is also heavily involved with Venezuela’s oil industry . In the early 2000s, Cuban leader Fidel Castro signed a deal with Hugo Chavez to provide Cuba with crude oil in exchange for Cuban professional staff and intelligence and security agents to go to Venezuela. Venezuela’s oil production has collapsed and Cuba gets far less oil than the agreement states, but Cuba’s reliance on Venezuelan oil and the countries’ long-standing allegiances to one another are incentives to support the Maduro regime. The opposition has criticized this longstanding agreement .

Tension has surrounded Citgo , a wholly-owned subsidiary of Venezuela’s PDVSA operating in the U.S. Citgo manages three refineries in the U.S. and amounts to about 4 percent of U.S. fuel. The Citgo business relationship has been strained, especially after Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin imposed sanctions on Venezuela’s PDVSA “so that any new profits would be deposited in an account under Guaidó’s authority ,” although the administration has yet to figure out how to disburse these funds to Guaidó. In recent months, this has become a serious problem for Guaidó, whose National Assembly would need to make a $913 million payment to PDVSA bondholders to maintain control of Citgo.

The Future for Venezuela

Opposition uprising.

Pressure from Abroad

On January 23, 2019, the U.S. recognized Guaidó as the leader of Venezuela, which prompted a series of U.S. sanctions against the Maduro regime. In August 2019, these sanctions turned into a total economic embargo . Most of Europe called for re-elections by the end of January, and Spain, Britain, France, and Germany endorsed Guaidó after Maduro refused to hold elections again. At the end of January 2019, European Union lawmakers voted 439 in favor to 104 against (with 88 abstentions) to recognize Guaidó until “new free, transparent and credible presidential elections” take place. The EU parliament has no foreign policy powers, but does have symbolic importance, especially in the realm of human rights. Also in the realm of human rights, the International Criminal Court prosecutor announced in November 2021 the decision to open an investigation into possible crimes against humanity committed in Venezuela.

Maduro severed diplomatic relations with the U.S. For more on the tense relationship between the U.S. and Venezuela and how it’s affecting conditions right now, check out this BBC video .

Violence and political stalemate continue . Peace talks over the summer of 2019 between the two sides did little in the way of reaching a compromise. In January 2021, the opposition party boycotted national elections, which means technically Gauidó’s term as congressional speaker expired. Many Latin American and European nations have “ distanced themselves ” from the opposition as they cannot justify “recognizing a leader who has no control over the country,” although the U.S. still offers its support. The Maduro government and the opposition held meetings in Mexico in August 2021 to negotiate, but the government withdrew in October 2021 and negotiations have not restarted .

Meanwhile, Venezuela’s crisis situation shows no signs of improving. As governments and factions compete for power, the people of Venezuela continue to suffer.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

- Check out this Policy Circle Brief on Free Enterprise & Economic Freedom or It’s a Wonderful Loaf from Russ Roberts at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution for more on markets and how they are affected by government interference

- Listen to The Policy Circle’s Conversation Call about Venezuela

- Keep track of bills in Congress related to Venezuela.

- Know who decides policy in Venezuela: Stay up to date with information from the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

- Organize a community gathering about aid, policy, and what your tax dollars are going to support in foreign countries.

- Pose any questions in a written piece for your local publication to make others in your community aware and seek answers. Check out the Policy Circle’s guide to writing an Op-Ed.

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, postponed: a complete impasse—gaza: the human toll, is it me or the economic system changing chinese attitudes toward inequality: a big data china event, the u.s. vision for ai safety: a conversation with elizabeth kelly, director of the u.s. ai safety institute, new frontiers in uflpa enforcement: a fireside chat with dhs secretary alejandro mayorkas.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- Warfare, Irregular Threats, and Terrorism Program

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

Potential Scenarios for Venezuela’s Future

Photo: Federico Parra/AFP/Getty Images

Table of Contents

Report by Moises Rendon and Mark L. Schneider

Published June 20, 2017

Available Downloads

- Download PDF file of "Potential Scenarios for Venezuela's Future" 192kb

- Download PDF file of "Potenciales Escenarios para el Futuro de Venezuela" 221kb

Spanish version available here.

Given the ongoing political, economic, social, and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela, in early June CSIS convened a small group of experts to identify the major drivers of possible future scenarios for the crisis. The small group undertook a half-day exercise to identify the most important determinants of Venezuela’s future and to imagine four possible scenarios, or “alternate futures” based on those key drivers. [1]

The exercise concluded that the two major drivers that will influence the outcome of the crisis are the degree of internal stability that the regime can maintain and the degree and type of external pressure or assistance the regime receives from key international actors. The following are four potential scenarios for Venezuela’s future, listed in no particular order of likelihood. Each of these transitions would have major impacts on the “Day After” challenges facing the country.

Scenario Number 1: A Soft Landing—Opposition Ideology and Chavismo Live Together

The “Soft Landing” scenario is the product of successful, increased international and regional pressure, coupled with the consolidation of opposition forces into a cohesive unit. In this scenario, the regional and international community gets its act together and unifies around specific actions designed to pressure the regime and force a transition. These include individual U.S. sanctions, replicated regionally, and efforts to support the political opposition and key institutions like the National Assembly.

In this scenario, the constituent assembly is rejected when President Nicolás Maduro’s “inner circle” splits, along with noncorrupted elements of the security forces and private-sector elites, forcing a peaceful transition. The defection of this group of Chavistas, which represents the last of his popular support (currently hovering at about 11 percent ), creates the conditions for a needed path toward the coexistence of the opposition and a significant portion of former Chavistas. While Chavismo will remain part of Venezuela’s cultural, economic, and political identity, many of the Chavistas in the country, having lost faith in Maduro’s government, will accept a managed transition that also offers them some protection.

The split within Maduro’s inner circle and the establishment of a stable and united political opposition leads to credible elections under a new National Electoral Council (CNE), monitored by the Organization of American States (OAS) and other observers and backed by a Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) with new members selected in accord with the current Constitution. The international community will be able to recognize a new (democratically elected) leadership and provide humanitarian, economic, financial, and judicial assistance to rebuild the country and its many crippled institutions. Freedom of the press, debt restructuring, humanitarian and health relief, anticorruption mechanisms, and institutional reforms are only a few examples of the potential benefits. In addition, some of the Venezuelan diaspora and their investments will return.

Though possible, this “best-case” scenario appears difficult to achieve in the short term. Fragmentation within the opposition, other than an existing consensus surrounding the need for Maduro’s departure, and Maduro’s sustained support within various government agencies, the National Guard, and armed militia, as well as from Cuba, Bolivarian Alliance for Peoples of Our America (ALBA), and cross-border narco-trafficking groups, are preventing any successful negotiation that could yield humanitarian relief and a stable political transition. International and regional actors remain unable to agree on elements of increased pressure.

Scenario 2: The Slow Unraveling of the Bolivarian Experiment

In this scenario, the internal situation continues to unravel slowly as international pressure on the regime fizzles. The central government continues to weaken, but the lack of coordinated, organized international pressure allows the regime to maintain control and prevents any peaceful negotiated transition of power in Venezuela. President Maduro can quell the April Rebellion—protests that started after the Supreme Tribunal took powers away from the National Assembly—using the Venezuelan National Guard and armed paramilitary groups ( colectivos ) to weaken the political stamina of opposition forces.

Additionally, Maduro moves forward with his plan to convoke an unelected “constituent” assembly, with the stated intent to write a new Constitution that threatens to establish a “communal state,” mimicking the political systems of North Korea and Cuba. This system rejects any referendum that would consider a constituent assembly unconstitutional and voids calls for democratic elections.

Continued disorganization and disunity of the opposition leads to further fragmentation, increased social unrest, violence, and crime, while the government’s failed economic policies continue, including hyperinflation, corruption, and expropriation of private property.

Externally, the provision of loans from China and Russia, coupled with increased international bond purchases (such as the most recent purchase by Goldman Sachs ), prevent Venezuela from defaulting on its debt and allow Maduro to hold on. Maduro continues to meet bare-bones public-sector obligations, including paying security force wages, but he fails to provide much else.

International organizations and coalitions, such as the OAS, are unable to unify behind actions that could force a shift in Maduro’s resistance to a negotiated transition. The Caribbean Community (CARICOM), dependent on Petrocaribe, remains aligned with Maduro’s interests in international fora, blocking effective action by those organizations. Other countries in Latin America either remain passive toward Venezuela’s crisis, or continue to prop up the administration, with continued apparent intelligence and political support from Cuba and the corrupt income stemming from drug-trafficking networks from Colombia.