TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Posted on Feb 07, 2022

Types of Poems: 15 Poetry Forms You Need to Know

Poetry is an art form that, for much of its history, has been defined by how it adheres to (or defies) its own tradition. And part of that rich tradition is the poetic forms that have been championed by each generation's leading writers. To understand where poetry is going next, readers and writers should ideally know where poetry has come from .

In this Reedsy guide, we will examine what it takes to write and publish poetry. But lest we run before we walk, we should first become intimate with the many faces of the great spoken art...

In other words, here are 15 types of poems everybody should know:

The invention of the sonnet is first accredited to the thirteenth-century Sicilian poet Giacomo da Lentini, who crafted the form as an ideal way of expressing ‘courtly love’. This poetry form was typically meant to express a ‘forbidden love’ in the court (think ‘noble lady falls in love with the squire’) and it was a genre in itself at the time.

Modern variations are closer to Seamus Heaney’s Glanmore Sonnets, in which he takes the drama expected of a sonnet and plays on that by writing about the mundane.

The two most common sonnets are named for their best-known practitioners: William Shakespeare and the 14th-century poet, Petrarch. While both of these are fourteen lines long, they come with different rule sets:

What makes a Shakespearean sonnet?

Structure: Fourteen lines of iambic pentameter.

- Three quatrains (4 lines), followed by a couplet (two lines).

- The final couplet presents a volta (AKA a thematic twist) or conclusion.

Rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

Similar forms in other cultures: Onegin stanza / oneginskaya strofa (Russian), Quatorzain (French, archaic).

What is iambic pentameter? Iambic pentameter consists of five iambic ‘feet’ — stressed syllables followed by unstressed syllables — sounding something like: Now IS the WIN-ter OF our DIS-con-TENT It was Shakespeare's favored meter, and, spoiler alert, iambic pentameter crops up in a lot of other poetic forms!

What makes a Petrarchan sonnet?

Structure: Fourteen lines, split into two stanzas, in iambic pentameter (traditionally).

- First stanza: eight lines (an octave) asking a question or posing an argument

- Second stanza: six lines (a sestet) answering that question.

- The volta arrives between the eighth and ninth lines

Meter: Iambic pentameter (traditionally).

Rhyme scheme: ABBA ABBA CDECDE

Shakespearean example: " Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date;

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm'd;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm'd;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st:

So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

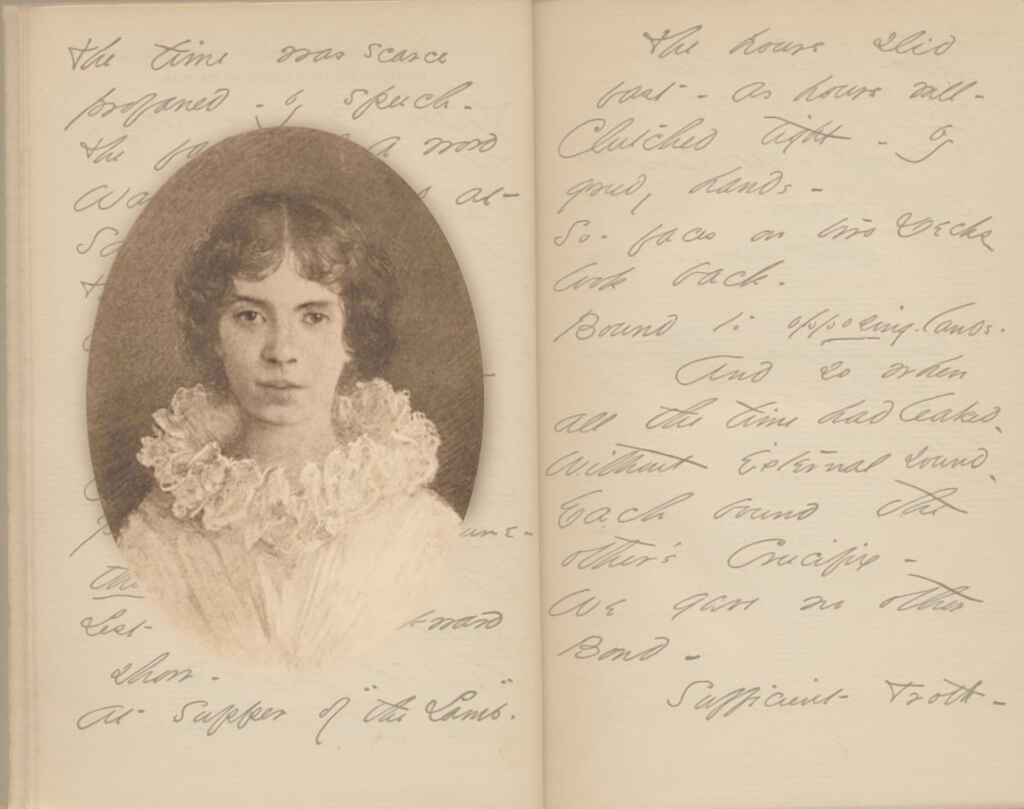

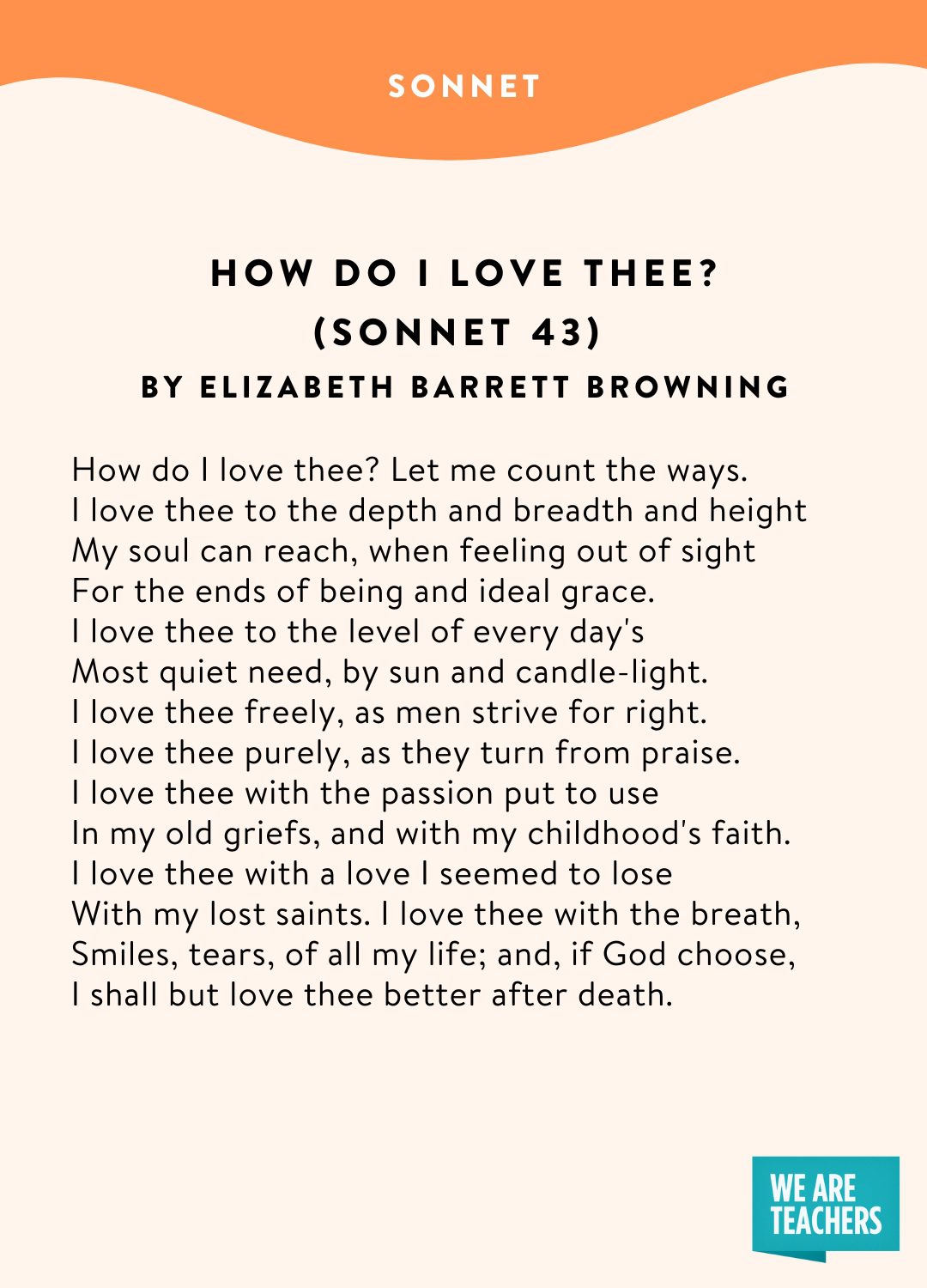

Petrarchan example: "How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)" by Elizabeth Barrett Browning

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Ever get so excited about that new book you’ve been waiting to get your hands on, or that new game with amazing graphics, that you just want to tell everyone about it? Well, poets have been right there with you for centuries, they even made a poetic form specifically to praise things they think are really amazing. (Though historically speaking, they probably didn’t write about games.)

What a mighty fine thing!

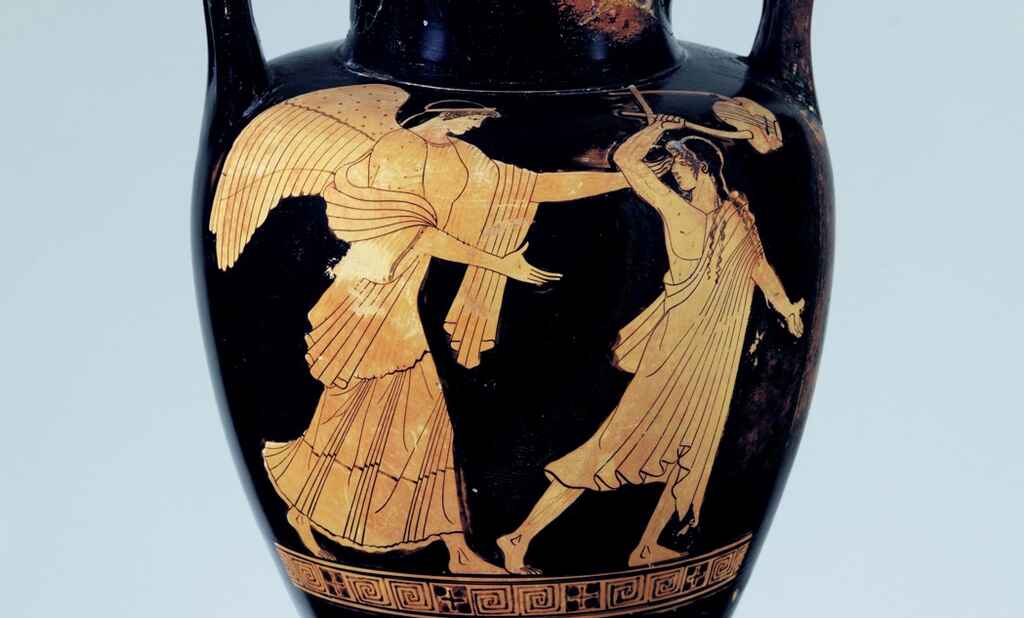

Unlike the previous poetry forms, the ode is a lyrical stanza addressing a specific person, place, thing, or event. In fact, it doesn’t just casually address the thing of choice; it’s written in elaborate praise of said thing. The term ‘ode’ originates from the Ancient Greek ōdḗ (or ‘ aoidē ’), meaning ‘song’ — likely reflecting the form’s origins as a predominantly musical form.

There are two classic subcategories of ode: Pindaric and Horatian — both of which follow an ABABCDECDE rhyme scheme. However, contemporary odes tend to be more irregular.

What makes a pindaric ode?

Structure: Traditionally separated into three-stanza sections; the strophe (two plus lines repeated as a unit), a metrically harmonious antistrophe (similar to the strophe, but with a thematic reverse), and the epode (concludes the poem thematically, and has a different meter and length to the previous stanzas).

Meter: Characterized by irregular line length.

Rhyme: ABABCDECDE

What makes a Horatian ode?

Structure: Written in a series of couplets or quatrains, thematically surrounding intimate scenes in day-to-day life. Irregular odes may follow any structure.

Meter: Poet's choice, but the rhyme scheme and meter should be consistent throughout.

Rhyme scheme: ABABCDECDE. Irregular odes have no set pattern.

What makes an i rregular ode?

Structure: No strict form, verse structure and patterns should be irregular.

Meter: As the title suggests, the meter can be irregular.

Rhyme scheme: Typically rhymed, but the placement of the rhyme is the poet's choice.

Pindaric ode extract: "Ode To Aphrodite" by Sappho

Deathless Aphrodite, throned in flowers, Daughter of Zeus, O terrible enchantress, With this sorrow, with this anguish, break my spirit Lady, not longer! Hear anew the voice! O hear and listen! Come, as in that island dawn thou camest, Billowing in thy yoked car to Sappho Forth from thy father's Golden house in pity! ... I remember: Fleet and fair thy sparrows drew thee, beating Fast their wings above the dusky harvests, Down the pale heavens, Lightning anon! And thou, O blest and brightest, Smiling with immortal eyelids, asked me: 'Maiden, what betideth thee? Or wherefore Callest upon me?

Horatian ode extract: "Ode to a Nightingale" by John Keats

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool'd a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Irregular ode extract: "Ode to the West Wind" by Percy Bysshe Shelle

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn's being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: O thou,

Who chariotest to their dark wintry bed

The winged seeds, where they lie cold and low,

Each like a corpse within its grave, until

Thine azure sister of the Spring shall blow

Her clarion o'er the dreaming earth, and fill

(Driving sweet buds like flocks to feed in air)

With living hues and odours plain and hill:

Wild Spirit, which art moving everywhere;

Destroyer and preserver; hear, oh hear!

While most modern readers may be more familiar with 80s power ballads than the works of middle-English poets — poetry, culture, and music as we know it today will owe a lot to this form.

Ballads were invented to narrate a story in a memorable way. (Ever heard of the lovable vigilante Robin Hood? You might not have if his legend wasn’t passed down in 14th-century ballads!)

"They'll sing songs about you one day..."

Though popularized by British and Irish bards, the name actually derives from the medieval French chanson balladée (meaning ‘dance songs’) — and it’s not hard to see the semblance between this form’s rhythm and structure and modern-day music:

Lithe and listen, gentleman,

That be of freeborn blood;

I shall you tell of a good yeoman,

His name was Robin Hood.

— A Gest of Robyn Hode, ed. Francis James Child.

While hardly the bread and butter of twenty-first-century writers, 1985's US poet laureate Gwendolyn Brooks has been praised for her mastery of this poetic form. Ballads nowadays can be easily identified by their quatrains (four-line stanzas) and simple, melodic rhyme scheme – designed to fit with musical accompaniment.

What makes a ballad?

Structure: Any length, usually written in quatrains.

Meter: Traditionally, they're written in alternating lines of iambic tetrameter (eight syllables) and iambic trimeter (six syllables).

Rhyme scheme: ABAB or ABCB, occasionally ABABBCBC.

Similar forms in other cultures: Vaar (Punjabi), Corrido (Mexican).

Ballad example: "A Ballad of Hell" by John Davidson

'A letter from my love to-day!

Oh, unexpected, dear appeal!'

She struck a happy tear away,

And broke the crimson seal.

'My love, there is no help on earth,

No help in heaven; the dead-man's bell

Must toll our wedding; our first hearth

Must be the well-paved floor of hell.'

The colour died from out her face,

Her eyes like ghostly candles shone;

She cast dread looks about the place,

Then clenched her teeth and read right on.

'I may not pass the prison door;

Here must I rot from day to day,

Unless I wed whom I abhor,

My cousin, Blanche of Valencay.

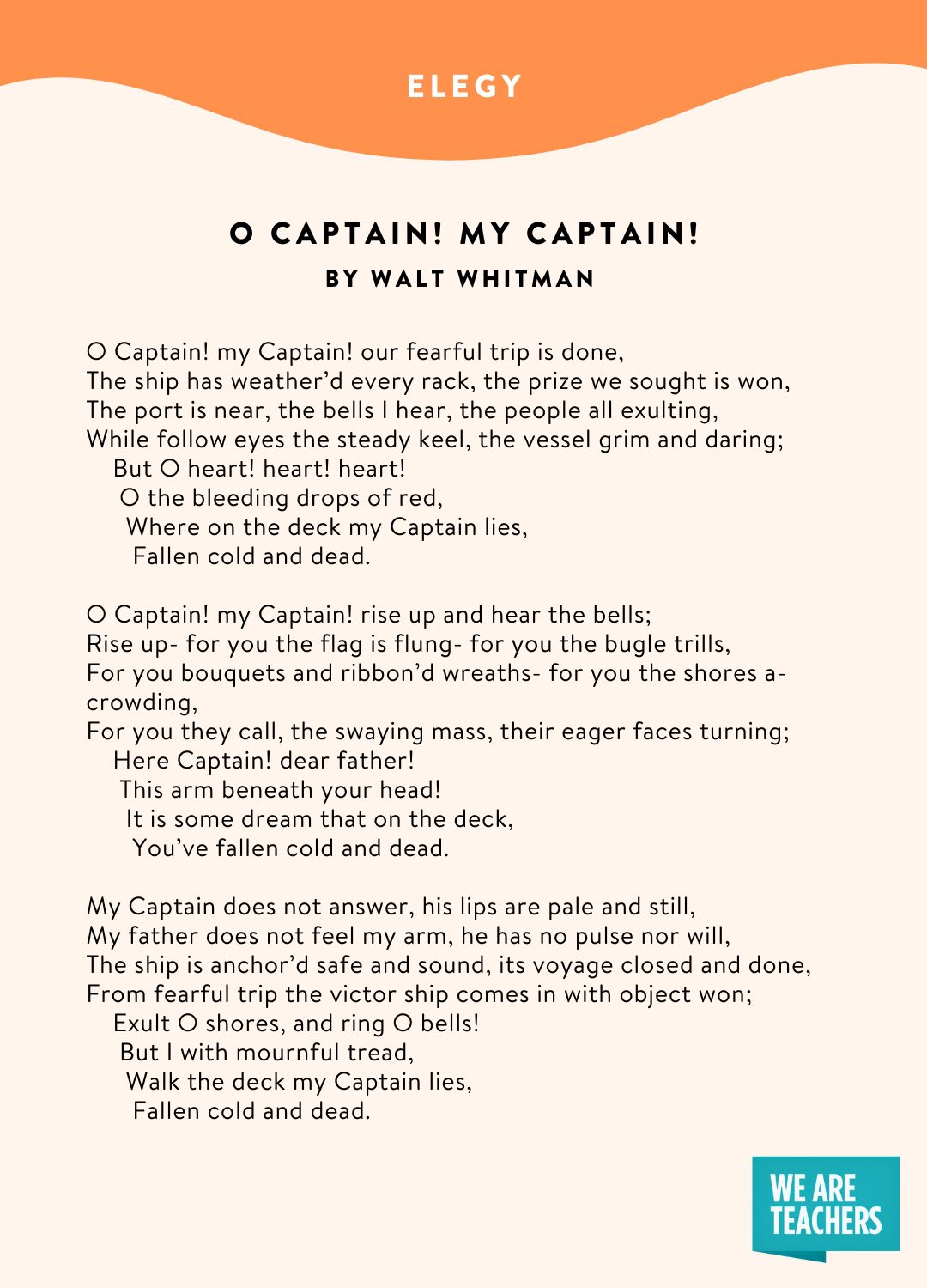

An elegy is a mournful poetic form, the origins of which can be traced back to a combination of Ancient Greek poetics and Old English scriptures from the 11th Century, written to lament a death.

Given the form’s long and rich history, you could point to a plethora of the most well-known poets — such as John Milton, or Walt Whitman — and probably find an elegy somewhere in their work.

You can mourn more than just a person

Of course, this expression of sorrow isn’t exclusive to the death of a person, but also the topic of loss more generally: how we deal with it, the abstract loss of things, or the absence of what once was. Think Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard , in which the speaker wanders through a churchyard (no surprises there) and begins to contemplate his own death, ultimately ending the poem with a passerby reading out an elegy for the narrator himself.

Typically, this form was written in elegiac couplets, but nowadays you’ll usually find them in rhyming quatrains. Of course, if you’re interested in identifying an elegy, or writing one yourself, the most important thing to know is that the rules aren’t strict as long as the content is on-message.

What makes an elegy?

Structure: Can be as long as the poet wants, and is mostly commonly written in couplets or quatrains, but it’s the poet’s choice as long as it’s about death/mourning/etc.

Meter: Iambic pentameter (usually).

Rhyme scheme: Typically ABBA or ABAB, but not strictly.

Similar forms in other cultures: Keening or Caointeoireacht (Gaelic Celtic), Rithā’ (Arabic), Soaz, Noha, and Marsiya (Arabic, Persian, Urdu).

Elegy example: "In Memoriam A.H.H." by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Our little systems have their day;

They have their day and cease to be:

They are but broken lights of thee,

And thou, O Lord, art more than they.

We have but faith: we cannot know;

For knowledge is of things we see

And yet we trust it comes from thee,

A beam in darkness: let it grow.

The epic poetry form is, as the name might suggest, one of the longest (and oldest) forms of poetry — often book-length. For context, the oldest recorded piece of literature is The Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates back to the Bronze Age between 2500 and 1300 BCE. Though commonly associated with Ancient Greek poets such as Virgil and Homer, almost every classic civilization had its own form of epic. For example, Mahabharata in ancient India and the ancient Persian Shahnameh .

While modern poets seldom write epics, the few that are published (such as Kate Tempest’s 2013 epic Brand New Ancients ) are equal parts eye-catching and ripe for critical acclaim when done well.

Epics are long by their very nature

Written in narrative verse, epic poems usually follow the story of a hero or a group of heroes — a famous example of this is, of course, The Odyssey by Homer. Though it’s difficult to define precise rules for writing epic poetry, The Odyssey’s structure is typical with its long stanzas and no rhyme scheme to speak of.

What makes an epic?

In the absence of strict rules, here are a couple of things to look out for:

Standard structure: Often epic (!) in stanza and overall length.

Common features:

- Repetition of words or symbols;

- Enjambement Sentences allow lines to carry over to the next without punctuation, which makes the stanza flow more similar to a real speech;

- Caesura: Mid-line pauses (usually signified by a full-stop or comma) are the poetry equivalent of writing ‘pause for effect’ in a script — helping to add weight to a line, control the pace of the poem, and mimic speech.

Similar forms in other cultures: Kāvya (Indian), Alpamysh (Turkish), Duma (Ukrainian).

Epic poetry extract: "The Odyssey" by Homer (trans. Emily Wilson).

“Hear me, leaders

And chieftains of Phaecia. I will tell you

The promptings of my heart. This foreigner —

I do not know his name — came wandering

from west or east and showed up at my house.

He begs and prays for help to travel on.

Let us assist him, as we have before

with other guests: no visitor has ever

been forced to linger in my house. We always

give them safe passage home. Now let us launch

a ship for her maiden voyage on the water,

and choose a crew of fifty-two, the men

selected as the best, and lash the oars

beside the benches. Then return to shore,

and come to my house. Let the young men hurry

to cook a feast. I will provide supplies,

plenty for everyone. And I invite

you also, lords, to welcome him with me.

Do not refuse! We also must invite

Demodocus, the poet. Gods inspire him,

so any song he chooses to perform

is wonderful to hear.”

6. Alexandrine

The modern English alexandrine is derived from the traditional French alexandrine: one line of twelve syllables, which may be repeated to form a whole poem. What's more, it's not technically a poetic form but a metrical structure — referring to the rhythm and length of a single line.

Though the French alexandrine and the English alexandrine are, by all accounts, pretty similar, there are two key differences when it comes to the caesura and emphasis on syllables, which we'll outline below.

We’ve made sure to include examples of the traditional French alexandrine alongside an English alexandrine. Because French language alexandrines are often translated to iambic pentameter for English speech patterns, we’ve also included French verse by poet and playwright Molière, as well as a faithful English translation of Du Bartas’s French poetry to show you how this form can look in French and English translation.

What makes a French alexandrine?

Structure: A single line adding up to twelve metric syllables.

Meter: Two half-sections (hemistichs) of six syllables , separated by a caesura (pause).

Rhyme scheme: Usually AABB or ABAB when used in a longer poem

Similar forms in other cultures: Trzynastozgłoskowiec (Polish), český alexandrín (Czech), mester de clerecía (Spanish).

What makes an English alexandrine?

Structure: A series of quatrains (four-line stanzas), any length.

Meter: Each line has twelve stresses, with no fixed caesura.

Similar forms in other cultures: Trzynastozgłoskowiec (Polish), český alexandrín (Czech), mester de clerecía (Spanish).

Alexandrine extract: "Le Misanthrope" by Molière

Que de son cuisinier il s'est fait un mérite,

et que c'est à sa table à qui l'on rend visite.

Note how there is a natural momentary pause after the fifth syllable of each line. This pause is what's known as a caesura .

Alexandrine extract: "La Sepmaine" by Guillaume de Saluste Du Bartas

Thou that guid’st the course of the flame-bearinge spheares;

The waters fomye bitt, Seas sou’reigne, thou that beares;

That mak’st the Earth to tremble; whose worde onely byndes,

And slackes th’vnruly raynes, to thy swifte postes the wyndes;

Alexandrine extract: "To A Skylark" by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert,

That from Heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.

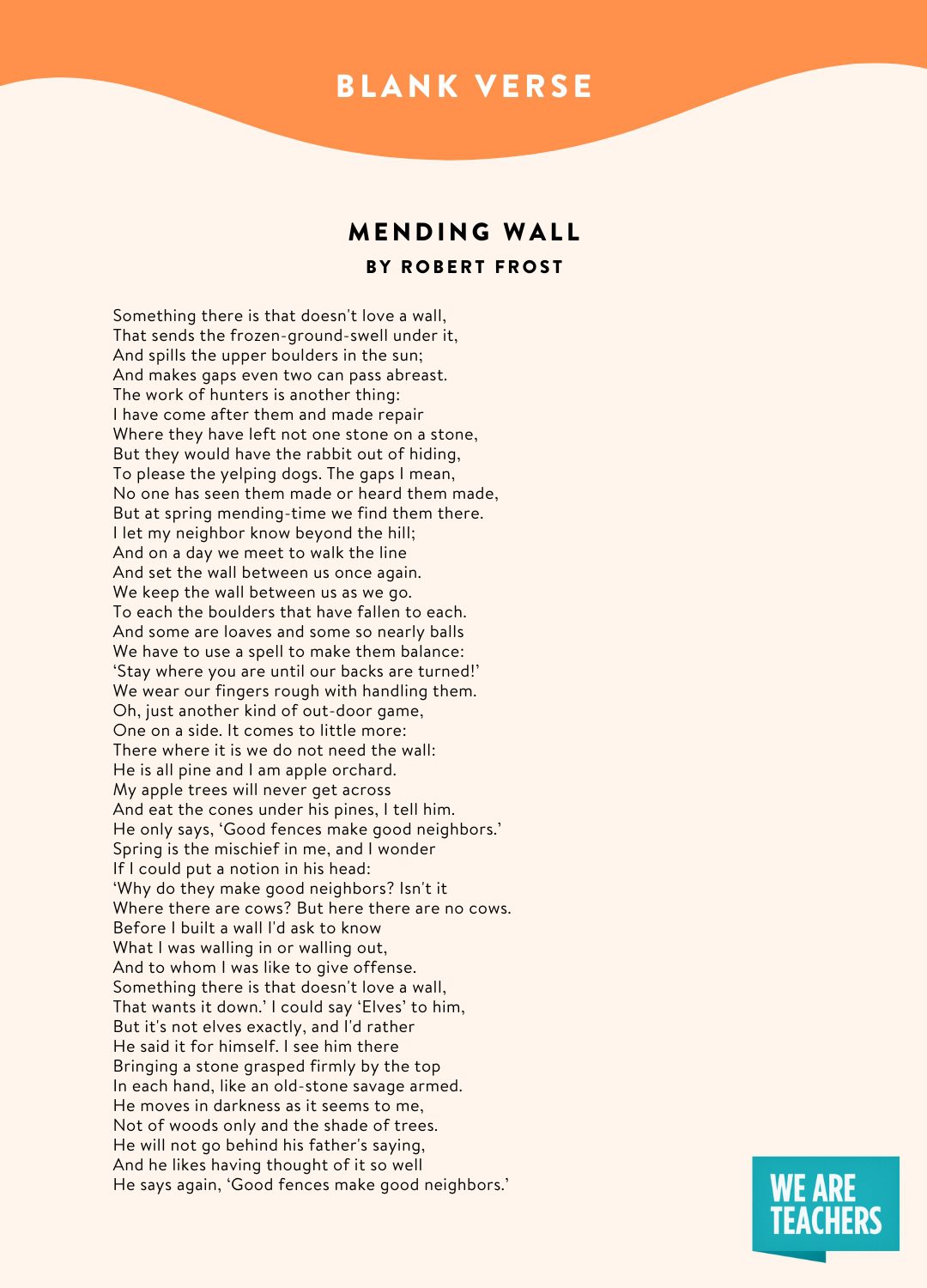

7. Blank verse

Popular with both old and contemporary writers, blank verse is unrhymed poetry — written most commonly in iambic pentameter. You’ll likely have encountered this form previously; it is commonly found in Shakespeare's plays and poems, chosen perhaps for its similarity to natural English speech. (And, not to mention, it would sound pretty strange if characters spoke in rhymes throughout every play!)

Because of its focus on rhythm above all, blank verse is a great form to look at if you want to delve into meter (what sounds right) and meaning ( why, without a rhyme scheme, is one word chosen over another).

What makes a blank verse poem?

Structure: Overall length and stanza length are the poet’s choice.

Meter: Must be in metric verse, usually iambic pentameter.

Rhyme scheme: Unrhymed.

Blank verse example: "Tintern Abbey" by William Wordsworth.

Five years have past; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur.—Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lose themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

8. Villanelle

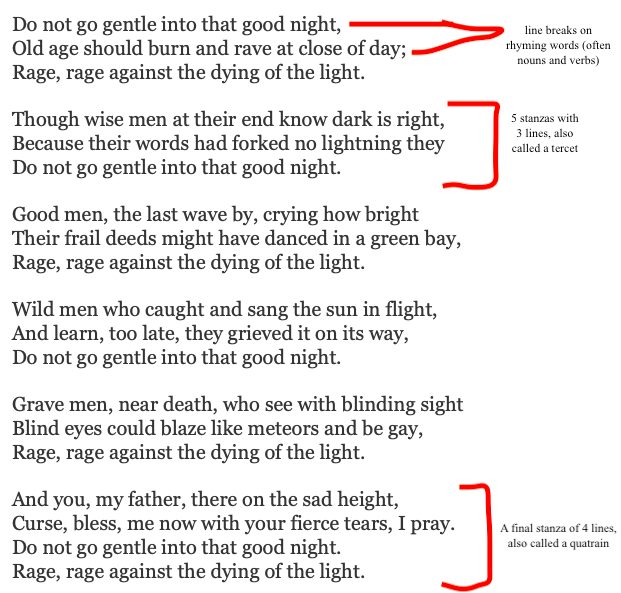

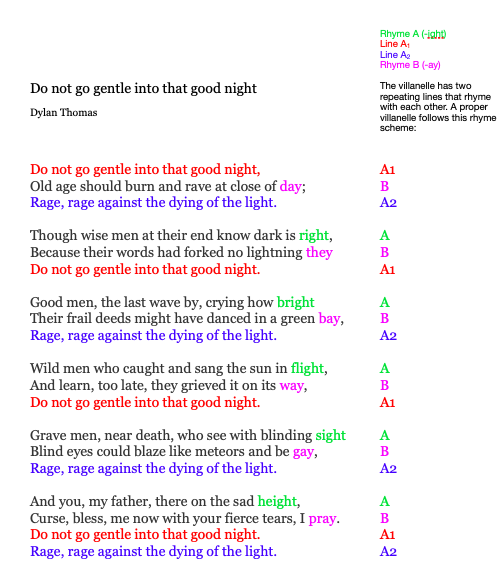

The villanelle is a nineteen-line poetic form strictly consisting of five three-line stanzas, ending in a quatrain.

Sadly, this form has nothing to do with a certain loveable villain from BBC’s Killing Eve. In fact, its name can be traced all the way back to the medieval Latin ‘villanus’, meaning ‘farmhand’, reflecting the villanelle’s origin as pastoral folk music — in which a single (usually female) singer would improvise lyrics while a ring of dancers danced around her.

It bears repeating...

The modern villanelle’s heavy use of refrain, in which specific lines of the poem are repeated, definitely reflects its musical roots. This common repetition has made it the favored form for poets who wish to convey obsession — such as with Sylvia Plath’s Mad Girl’s Love Song, in which the narrator obsesses over the loss of a loved one who may or may not have been real.

What makes a villanelle?

Structure: Nineteen lines, structured with five tercets (three-line stanzas) followed by a quatrain.

Meter: No strict meter, though most villanelle's after the twentieth century have been written in pentameter.

Repetitions:

- Line one must repeat in lines six, twelve, and eighteen.

- Line three must repeat in lines nine, fifteen, and nineteen.

Rhyme scheme: ABA, ABA, ABA, ABA, ABA, ABAA.

Villanelle example: "Theocritus" by Oscar Wilde

O Singer of Persephone!

In the dim meadows desolate

Dost thou remember Sicily?

Still through the ivy flits the bee

Where Amaryllis lies in state;

O singer of Persephone!

Simaetha calls on Hecate

And hears the wild dogs at the gate;

Still by the light and laughing sea

Poor Polypheme bemoans his fate:

And still in boyish rivalry

Young Daphnis challenges his mate:

Slim Lacon keeps a goat for thee,

For thee the jocund shepherds wait,

Villanelle extract: "Mad Girl’s Love Song" by Sylvia Plath

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red,

And arbitrary blackness gallops in:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

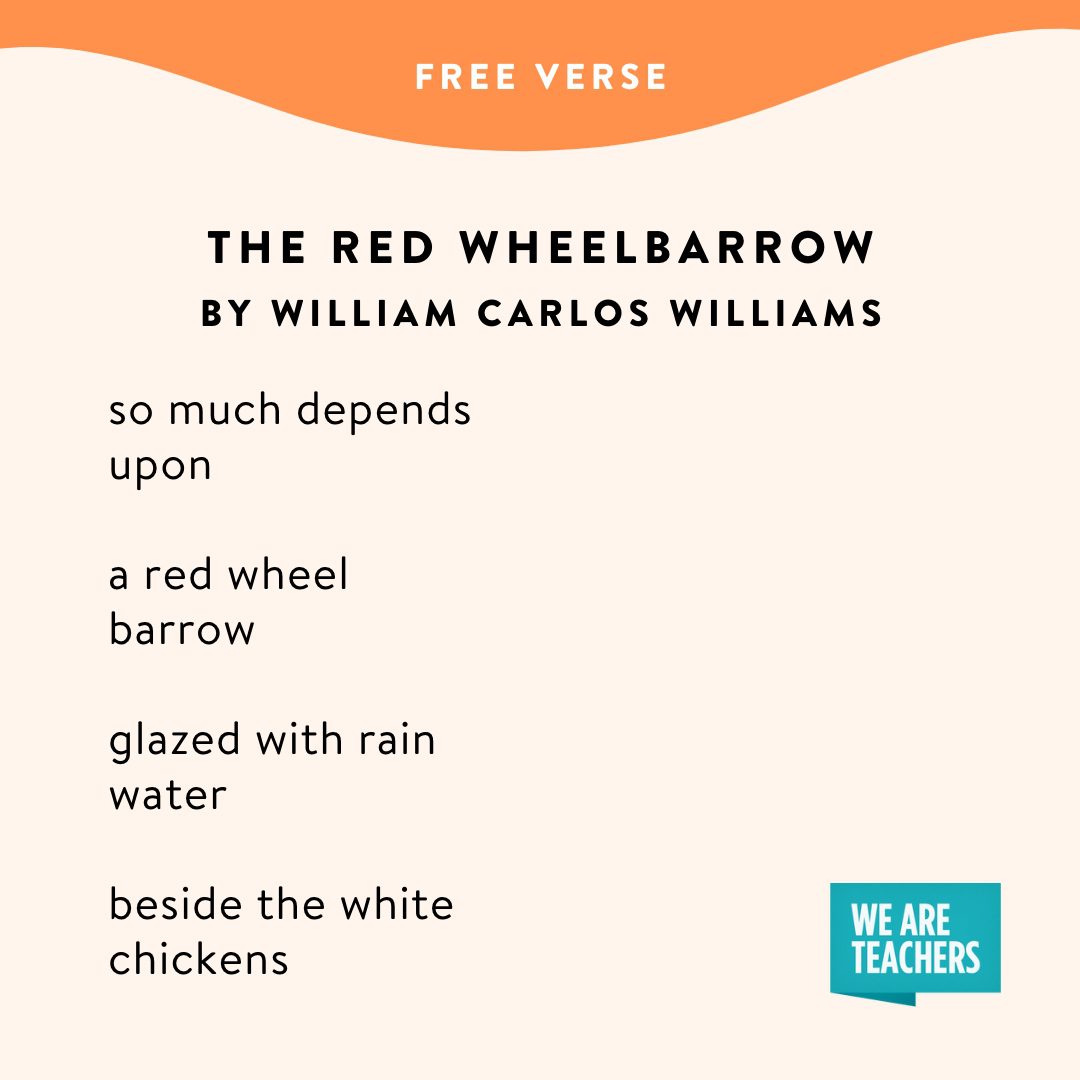

9. Free verse

Free verse is the favored poetry form for many contemporary poets, in large part because (as the name implies) they can make their own rules — and break them if they wish. Poets naturally choose to make their own rules most often because, in this form, understanding the effect of punctuation and stanza breaks on how a poem is read is essential.

When writing in free verse, poets (that is if they want to make their poetry public) must be considerate of the reader: how will one rhyme scheme read vs. another? Does this pause emphasize the previous line properly? Are there enough breaks for the reader to catch their breath? These are just some of the questions a poet writing in free verse might ask themselves!

What makes a free verse poem?

Structure: Poet’s choice.

Meter: Anything, really.

Rhyme scheme: Any which way is fine.

Equivalent in other cultures: Japanese haibun.

Free verse example: "Come Slowly, Eden" by Emily Dickinson.

Come slowly – Eden!

Lips unused to Thee –

Bashful – sip thy Jessamines –

As the fainting Bee –

Reaching late his flower,

Round her chamber hums –

Counts his nectars –

Enters – and is lost in Balms.

Note: Free verse always results in interesting book interiors! Check out our post on poetry book layouts for insights from designers and inspiration.

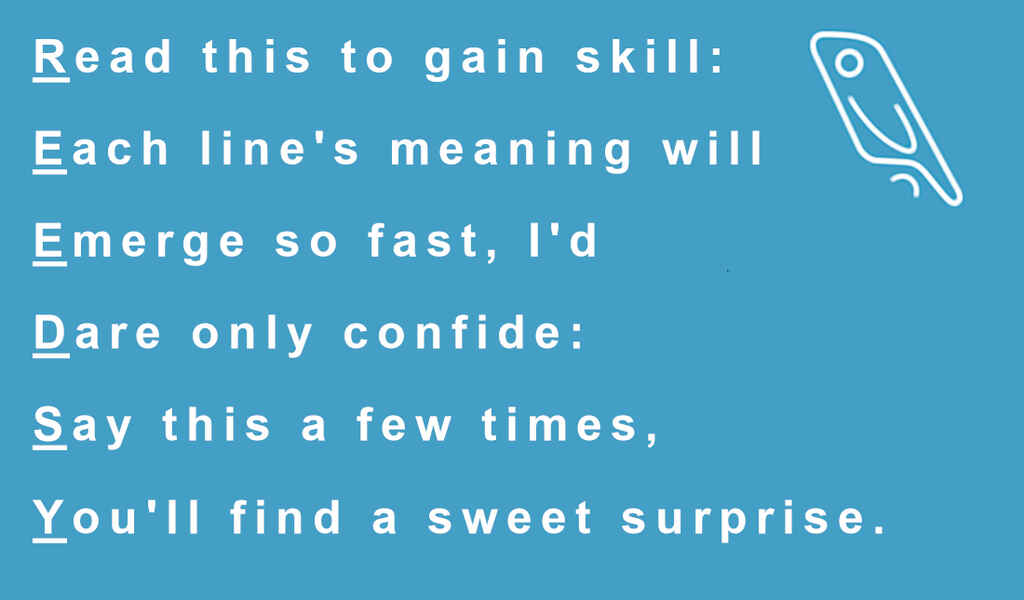

10. Acrostic

Acrostic poetry spells out a secret meaning, often using the first letter of each new line, stanza, or any other recurring feature. The hidden message could be a word, phrase, or, more commonly, a name — sounds exciting, right? This form was popularised from the high middle ages onwards, with many poets at the time beginning their longer works with a short acrostic spelling their name.

Hidden in plain sight

The beauty of this form is the diversity in how it might be used. Indeed, there have been several instances in recent years of people — such as CEOs, resigning employees, politicians — utilizing prose acrostics in emails and letters (often to convey a political message). You can even find multiple acrostics in the same poem — you might point to Behold, O God! by William Browne, in which you can find three different hidden New Testament verses, as a great example of this.

There aren’t strict rules when it comes to writing this form; you only need to remember that, if there’s a hidden meaning (which is often identified through seemingly random capitalization of letters) then chances are that you’re reading an acrostic.

What makes an acrostic?

Structure: Poet’s choice — just get a hidden meaning in!

Meter: Poet’s choice, but this will probably be determined by the hidden meaning.

Rhyme scheme: Poet’s choice!

Acrostic example: "Elizabeth" by Edgar Allan Poe.

Elizabeth, it surely is most fit

[Logic and common usage so commanding]

In thy own book that first thy name be writ,

Zeno and other sages notwithstanding;

And I have other reasons for so doing

Besides my innate love of contradiction;

Each poet - if a poet - in pursuing

The muses thro' their bowers of Truth or Fiction,

Has studied very little of his part,

Read nothing, written less - in short's a fool

Endued with neither soul, nor sense, nor art,

Being ignorant of one important rule,

Employed in even the theses of the school-

Called - I forget the heathenish Greek name

[Called anything, its meaning is the same]

"Always write first things uppermost in the heart."

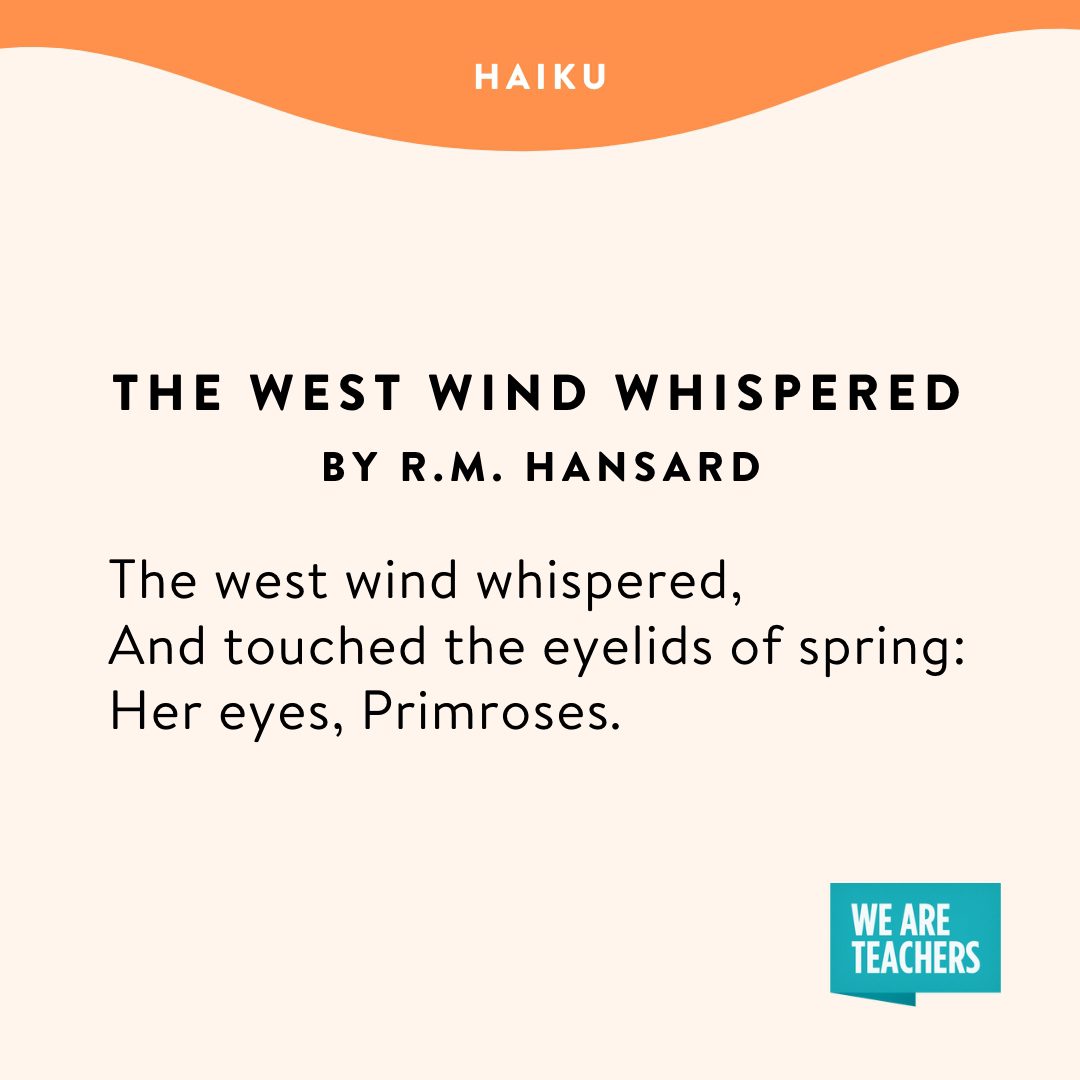

The haiku may often be the first type of poem you encounter; whether you’ve had to write one for school, or you’ve encountered them as Instagram poetry, you’ve probably had some experience with haiku . Though they were traditionally poems about the poet’s geographical and seasonal placement, paying homage to the landscape, nowadays people use the short form for comedic effect.

Short and sweet

The haiku is a three-line poem, with a 5-7-5 syllable structure, originating in seventeenth-century Edo-period Japan. Originally named ‘hokka,’ the haiku is derived from the opening of a longer, collaborative, form of Japanese poetry called renga (or, linked poetry). Notably, most English translations separate haiku into three separate lines, while (romanized) originals are usually one single line separated by caesura.

What makes a haiku?

Structure: Three lines long, with a 5-7-5 syllable structure:

- Line one: five syllables.

- Line two: seven syllables.

- Line three: five syllables.

Meter: Each line must follow the 5-7-5 syllable structure.

Rhyme scheme: N/A.

Haiku example: "The Oak Tree" by Matsuo Bashō

In the original Japanese, romanized:

Kashi no ki no / hana ni kamawanu / sugata kana.

In English, translated by Robert Hass.

The oak tree:

not interested

in cherry blossoms.

12. Epigram

An epigram is a short poetic form that can range from two to four lines long. That said, many poets choose to create longer poems using this form by essentially lacing a number of smaller poems together — the end effect being that each section works well with the next while also standing on its own.

Little poems found in the wild

Though the form was popularized by poets such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Voltaire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, you might also point to Ezra Pound or Ogden Nash as more recent writers who favored this style. You might also be interested to know that, unlike other forms, epigrams are not exclusive to poetry. They can be used as a literary device, or in a speech to illustrate complex ideas concisely. (You might point to “an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind,” a quotation often attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, as a good example of this.)

What makes an epigram?

If you’re looking to spot a poetic epigram, take a look at these simple rules:

Structure: Two to four lines, structured in couplets or four-line quatrains.

Meter: Often in iambic pentameter, but not strictly so.

Rhyme scheme: ABAB (most commonly).

Epigram example: "Auguries of Innocence" by William Blake.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Epigram example: "Underwoods: Epigram" by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Of all my verse, like not a single line;

But like my title, for it is not mine.

That title from a better man I stole:

Ah, how much better, had I stol'n the whole.

13. Epitaph

Think of epitaphs as like ‘Elegy Lite’. They’re often found carved onto gravestones so they need to be short unless the intended grave is actually a mausoleum. They also don’t have specific rules to speak of. They date back to the Ancient Egyptians and Greeks — but the English language form used nowadays is derived more closely from the Ancient Roman version, which was less emotive and focused on portraying facts about the deceased.

So long, farewell

That said, modern epitaphs often include riddles, puns on names or professions, and even acrostics (though, it takes some care to know when humor is appropriate). One of the most famous influences for the modern-day epitaph is Robert Burns, who wrote thirty-five epitaphs (for close family, friends, and even himself), many of which were satirical.

What makes an epitaph?

Structure: Poet’s choice!

Meter: Poet’s choice!

Similar forms in other cultures: Jisei (Japanese).

Epitaph example: "Epitaph on my own Friend" by Robert Burns

An honest man here lies at rest

As e'er God with his image blest.

The friend of man, the friend of truth;

The friend of Age, and guide of Youth:

Few hearts like his with virtue warm'd,

Few heads with knowledge so inform'd:

If there's another world, he lives in bliss;

If there is none, he made the best of this.

Epitaph example: "Epitaph" by Edna St. Vincent Millay

Heap not on this mound

Roses that she loved so well;

Why bewilder her with roses,

That she cannot see or smell?

She is happy where she lies

With the dust upon her eyes.

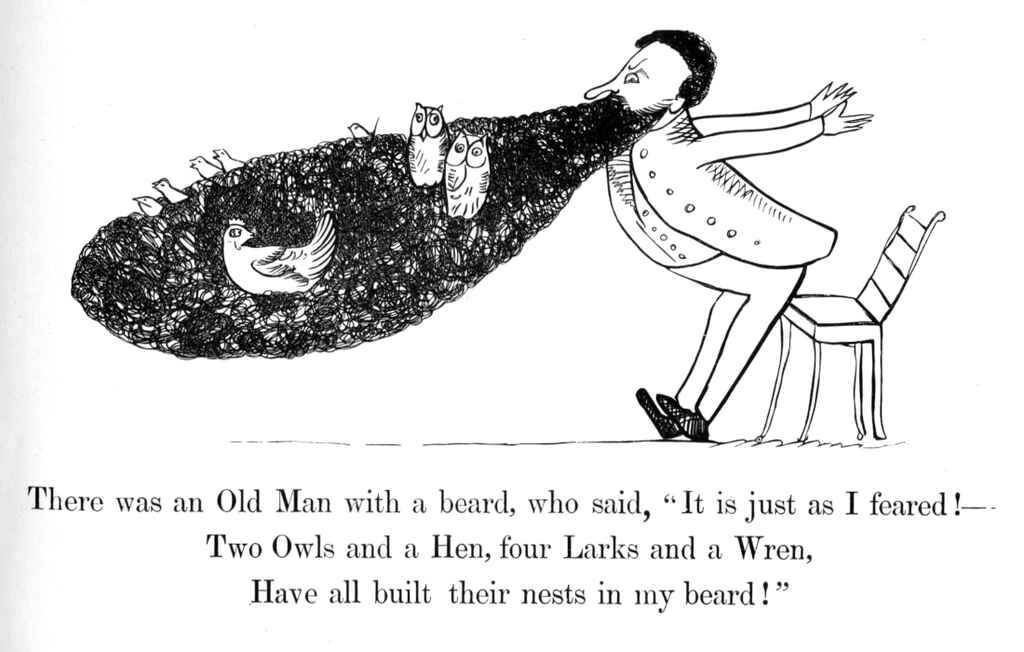

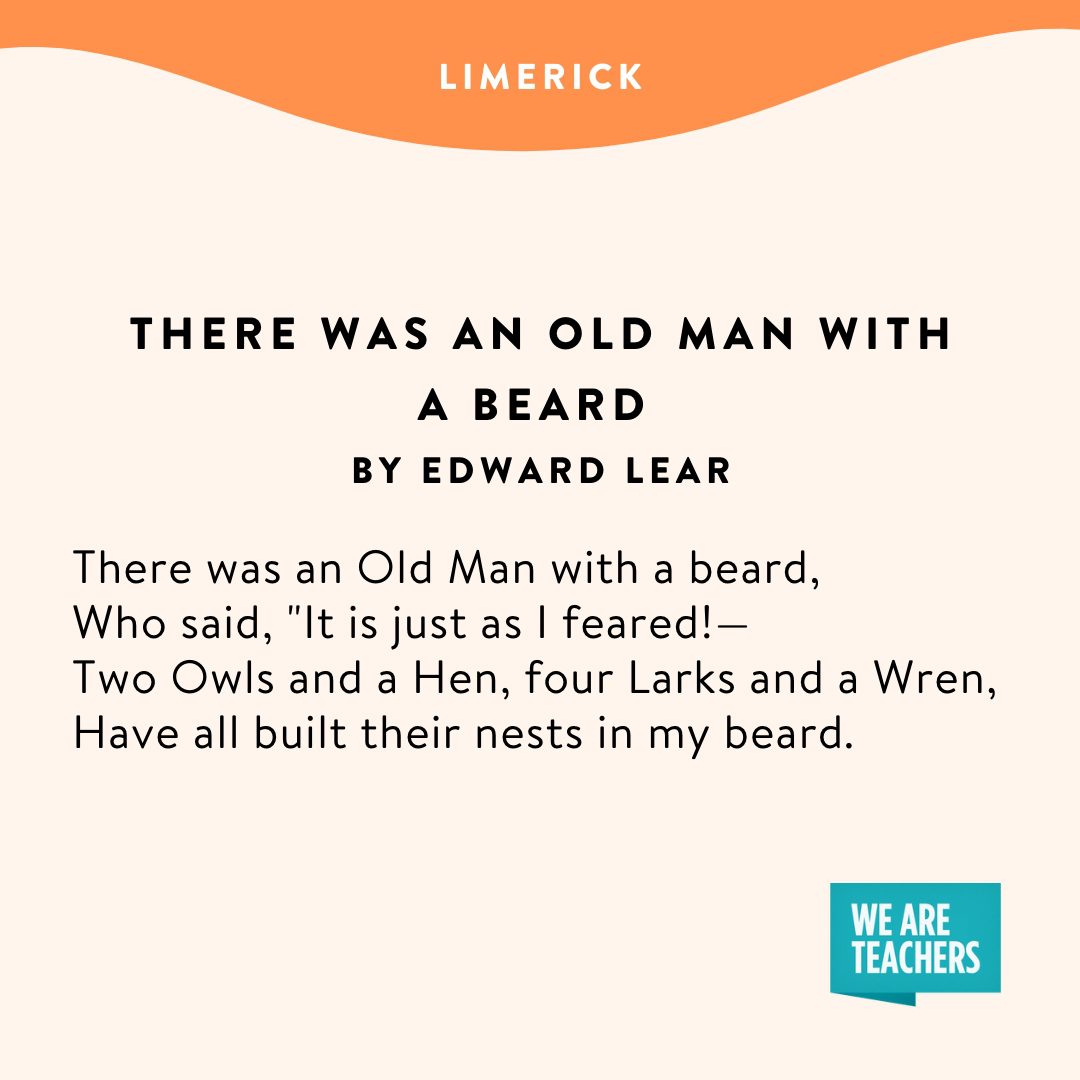

14. Limerick

If you’ve ever heard a poem about an old man from Nantucket, then you’ve almost certainly encountered a limerick. These humorous poems, known best for their often rude or shocking punchlines, were popularized by Edward Lear in the nineteenth century.

Part of what enhances the reader’s enjoyment of this form is the distinct AABBA rhyme scheme and rhythm which makes it fun to recite (and a great party trick!). After all, a great joke should feel inevitable and unexpected — the first rhyme of a limerick does this by setting a limit on what the punchline could possibly be, while the last line aims to catch you off-guard despite expectations.

What makes a limerick?

The most important guideline to follow when writing this type of poetry is, of course, to make it funny and memorable. That aside, limericks do have a few rules that make them easy to identify:

Structure: One stanza, five lines.

Meter: The predominant meter is anapestic (two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed syllable). Two long(er) lines of 7-10 syllables each, and two short lines of 5-6 syllables each. The final line should be a punchline.

Rhyme scheme: AABBA.

Note: Though the most common limerick form, following its rise in popularity, would rhyme the same word in the first and last lines, it’s more common now to avoid this, unless for a specific effect.

Limerick example: "Limerick" by Anonymous

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.

Limerick example: "There was an Old Man with a Beard" by Edward Lear

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, "It is just as I feared!—

Two Owls and a Hen, four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard.

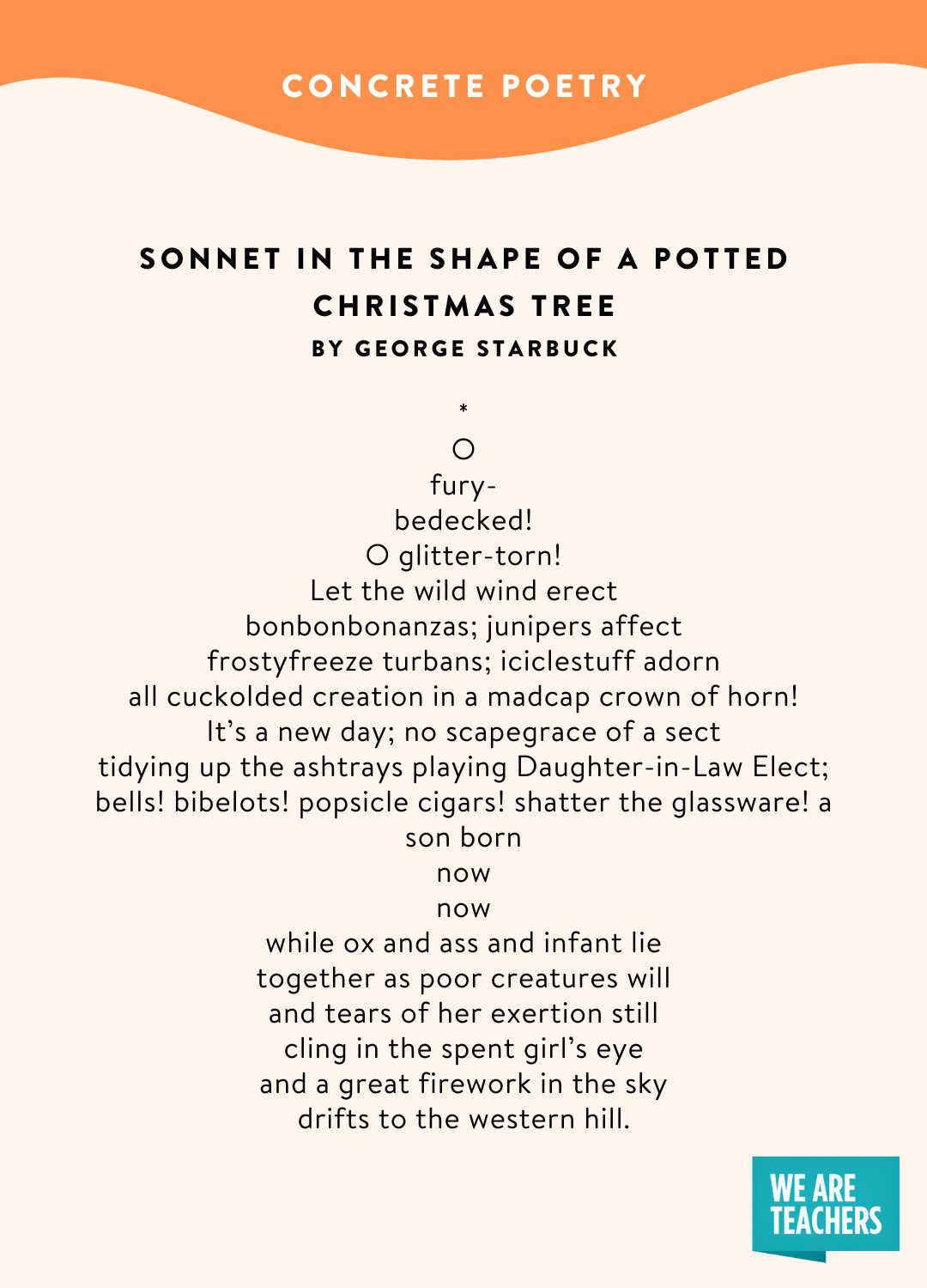

15. Concrete

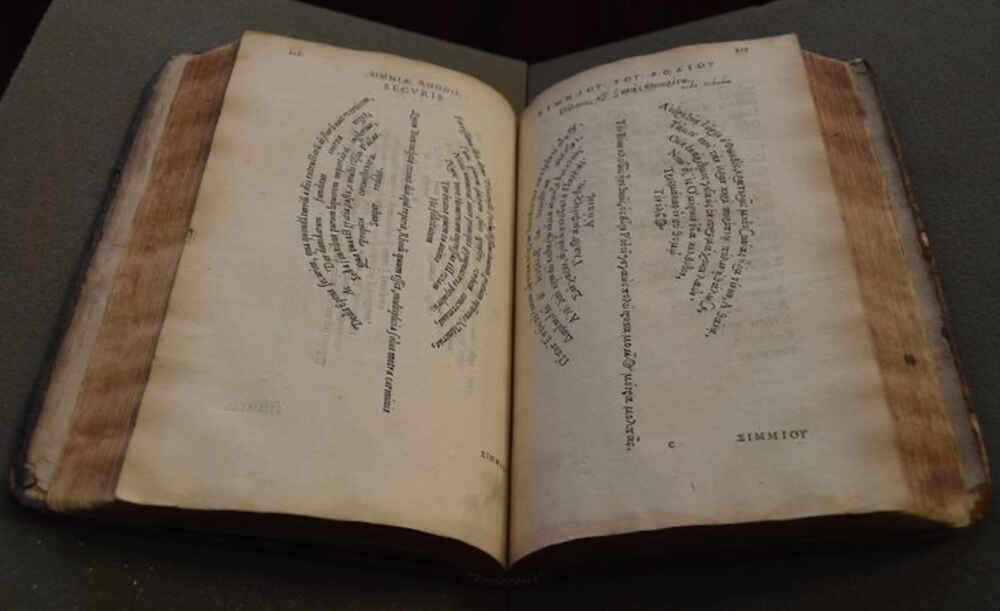

Concrete is given its name because, like concrete in a mold, it changes shape to fit the artist’s purpose. Indeed, it’s written to assume a specific shape on the page in order to reflect the poem’s subject matter. (And, let’s be honest, it’s probably quite an enjoyable form to play around with!)

This form was popular as far back as Greek Alexandria in the 3rd and 4th centuries BCE, and ancient examples of concrete poems (shapes like eggs or hatchets) still remain today. For more recent examples, you might point to George Herman, who was particularly well-known for his concrete poetry — such as in the example below, where the poem’s form mimics the ‘wings’ mentioned in the verse.

What makes a concrete poem?

Structure: How long is a piece of string? That aside, the poem’s physical shape should reflect a theme or symbol.

Meter: Beholden to the poem's shape.

Rhyme scheme: As the poet wishes...

Concrete poetry example: "Easter Wings" by George Herbert.

Lord, who createdst man in wealth and store,

Though foolishly he lost the same,

Decaying more and more,

Till he became

Most poore:

O let me rise

As larks, harmoniously,

And sing this day thy victories:

Then shall the fall further the flight in me.

My tender age in sorrow did beginner

And still with sicknesses and shame.

Thou didst so punish sinne,

That I became

Most thinne.

Let me combine,

And feel thy victorie:

For, if I imp my wing on thine,

Affliction shall advance the flight in me.

Now that you have an idea of the various traditional poetry forms mastered by poets of yesteryear, how would you like to write your own? Continue to the next part of this series and learn just that!

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Polish up your verse

Sign up to meet professional poetry editors on Reedsy.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Attempts to define poetry

- Major differences

- Poetic diction and experience

- Form in poetry

- Poetry as a mode of thought: the Protean encounter

- What is Miguel de Cervantes best known for?

- What was Miguel de Cervantes’s early life like?

- Why is Dante significant?

- What was Dante’s early life like?

- What is William Blake’s poetry about?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Palm Beach State College - What is Poetry?

- University of Texas - Liberal Arts Instructional Technology Services - What is Poetry?

- Humanities LibreTexts - About Poetry

- Academia - History of Poetry

- Poetry Foundation - U.S. Latinx Voices in Poetry

- The Open University - What is poetry?

- poetry - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- poetry - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

poetry , literature that evokes a concentrated imaginative awareness of experience or a specific emotional response through language chosen and arranged for its meaning , sound, and rhythm .

(Read Britannica’s biography of this author, Howard Nemerov.)

Poetry is a vast subject, as old as history and older, present wherever religion is present, possibly—under some definitions—the primal and primary form of languages themselves. The present article means only to describe in as general a way as possible certain properties of poetry and of poetic thought regarded as in some sense independent modes of the mind. Naturally, not every tradition nor every local or individual variation can be—or need be—included, but the article illustrates by examples of poetry ranging between nursery rhyme and epic . This article considers the difficulty or impossibility of defining poetry; man’s nevertheless familiar acquaintance with it; the differences between poetry and prose; the idea of form in poetry; poetry as a mode of thought; and what little may be said in prose of the spirit of poetry.

Poetry is the other way of using language . Perhaps in some hypothetical beginning of things it was the only way of using language or simply was language tout court , prose being the derivative and younger rival. Both poetry and language are fashionably thought to have belonged to ritual in early agricultural societies; and poetry in particular, it has been claimed, arose at first in the form of magical spells recited to ensure a good harvest. Whatever the truth of this hypothesis , it blurs a useful distinction: by the time there begins to be a separate class of objects called poems, recognizable as such, these objects are no longer much regarded for their possible yam-growing properties, and such magic as they may be thought capable of has retired to do its business upon the human spirit and not directly upon the natural world outside.

Formally, poetry is recognizable by its greater dependence on at least one more parameter , the line , than appears in prose composition . This changes its appearance on the page; and it seems clear that people take their cue from this changed appearance, reading poetry aloud in a very different voice from their habitual voice, possibly because, as Ben Jonson said, poetry “speaketh somewhat above a mortal mouth.” If, as a test of this description, people are shown poems printed as prose, it most often turns out that they will read the result as prose simply because it looks that way; which is to say that they are no longer guided in their reading by the balance and shift of the line in relation to the breath as well as the syntax .

That is a minimal definition but perhaps not altogether uninformative. It may be all that ought to be attempted in the way of a definition: Poetry is the way it is because it looks that way, and it looks that way because it sounds that way and vice versa.

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

Types of Poetry: The Complete Guide with 28 Examples

by Fija Callaghan

Poetry has been around for almost four thousand years, predating even written language, and it’s still evolving all the time. Let’s explore some of the different types of poems you might come across, including rhymed poetry and free verse poetry, and how experimenting with a poem’s structure can make you a better poet.

Why do the different forms of poetry matter?

Poetic forms are important when we write poems for three main reasons:

1. Forms make poetry easier to remember

At its inception, poetry was used as a way to pass down stories and ideas to new generations. Poetry has been around longer than the written word, but even after people started writing things down, some cultures continued telling stories orally. They did this by telling stories as poems. Using set rhyme schemes, meters, and rhythms made it easier to learn those poems by heart.

2. Form shapes the rhythm and sound of a poem

Using poetic structure helps shape the way a poem will sound when it’s spoken out loud. Even though most of our poetry today is written down, it’s still heard at live performances, and we’ll often “hear” a poem in our head as we’re reading it. Different types of poetry will have different auditory moods and rhythms, which contributes to the overall emotional effect.

3. Form challenges our use of language

As writers, we always want to be challenging ourselves to use words in new and exciting ways. Using the constraints of formal poetry is a great way to stretch our imagination and come up with new ideas. The story theorist Robert McKee calls this “creative limitation.” By imposing limits on what we can do, we’ll instinctively look for ever more creative and imaginative ways to use the limited space that we’re given.

Free verse poetry vs. rhymed poetry

These days, rhymed poetry has fallen out of vogue with contemporary poets, though it still has its champions. In the early 20th century free verse, or free form, poetry was embraced for its fluid, conversational qualities, and dominates the poetic landscape today. It became popular in part because it feels less like a performance and more like you’re talking directly to the reader.

Rhymed poetry, on the other hand, is great for getting a message across to the reader or listener. Most pop songs today are, at least in part, rhymed poetry—that’s why we remember them and find ourselves mulling over the lyrics days later.

We’ll look more at different types of free verse poetry and rhymed poetry, and you can see which ones work best for you.

27 Types of Poetry

You might recognize some of these types of poems from reading poetry like them in school (Edgar Allan Poe, William Shakespeare, and Walt Whitman are all names you’ve probably come across in English class!) Others might be new to you. Once you know a little bit more about these common forms (and some less common ones), you can even enjoy writing some of your own!

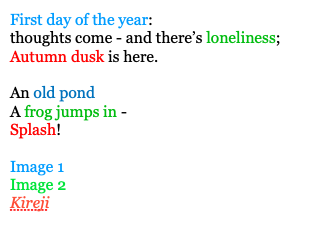

A haiku is a traditional cornerstone of Japanese poetry with no set rhyme scheme, but a specific shape: three lines composed of five syllables in the first line, seven in the second line, and five in the third line.

Occasionally, some traditional Japanese haiku won’t fit this format because the syllables change when they’re translated into English; but when you’re writing your own haiku poem in your native language, you should try to adhere to this structure.

Haiku poems are often explorations of the natural world, but they can be about anything you like. They’re deceptively simple ideas with a lot of poignancy under the surface.

Here’s an example of a haiku poem, “Over the Wintry” by Natsume Sōseki:

Over the wintry Forest, winds howl in rage With no leaves to blow.

Learn more about writing your own haiku poetry in our dedicated Academy article.

2. Limerick

A limerick is a short, famous poetic form consisting of five lines that follow the rhyme form AABBA. Usually these are quite funny and tell a story. The first two lines should have eight or nine syllables each, the third and fourth lines should have five or six syllables each, and the final line eight or nine syllables again.

Limericks are great learning devices for children because their rhythm makes them so easy to remember. Here’s a fun example of a limerick, “There Was A Small Boy Of Quebec” by Rudyard Kipling:

There was a small boy of Quebec, Who was buried in snow to his neck; When they said, “Are you friz?” He replied, “Yes, I is— But we don’t call this cold in Quebec.”

3. Clerihew

Clerihews are a little bit like limericks in that they’re short, funny, and often satirical. A clerihew is made up of four lines (or several four-line stanzas) with the rhyme scheme AABB, and the first line of the stanza must be a person’s name.

This poetry type is great for helping people remember things (or enacting some good-natured revenge). Here’s a famous example, “Sir Humphrey Davy” by Edmund Clerihew Bentley, the inventor of the eponymous clarihew:

Sir Humphrey Davy Abominated gravy. He lived in the odium Of having discovered sodium.

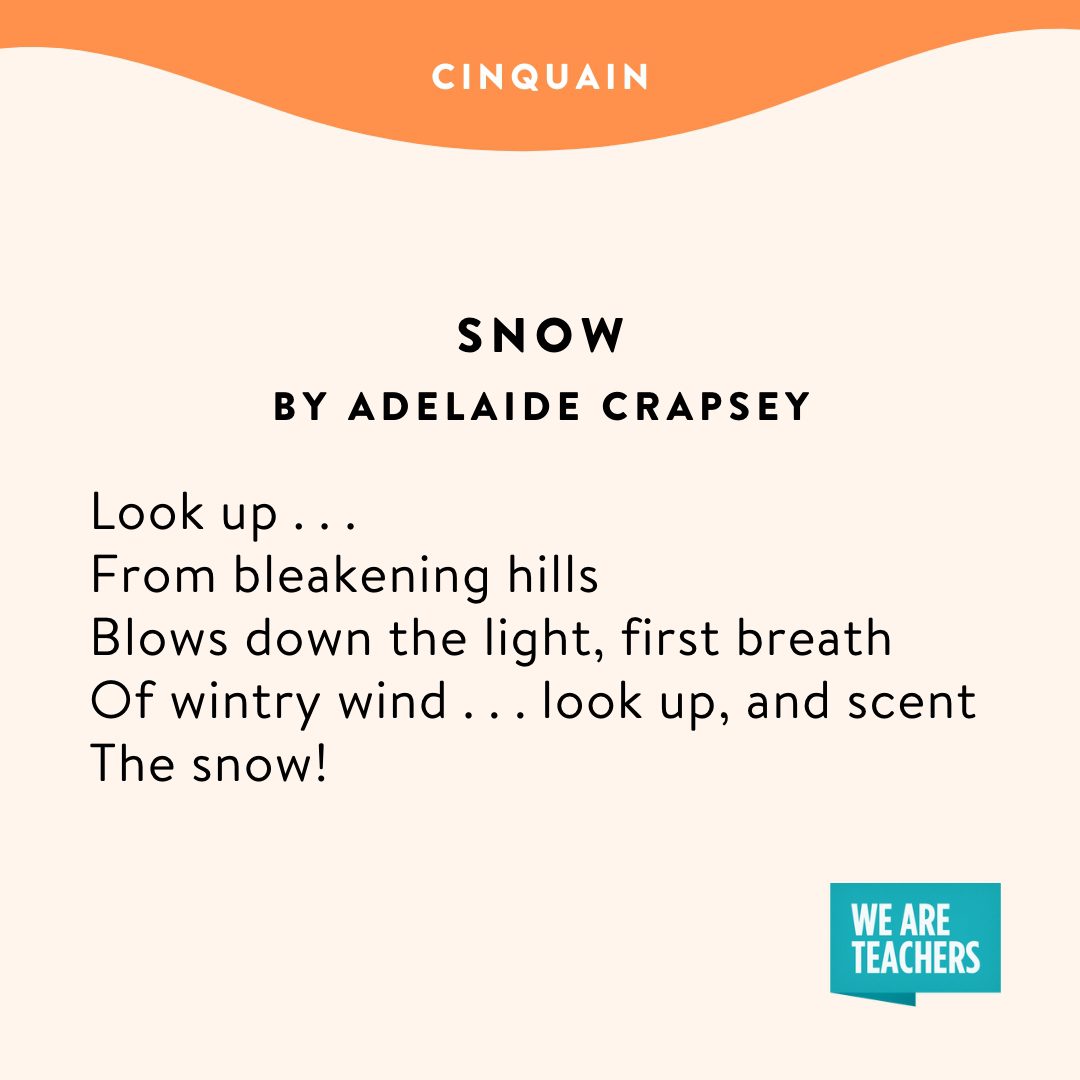

4. Cinquain

A cinquain is a five-line poem consisting of twenty-two syllables: two in the first line, then four, then six, then eight, and then two syllables again in the last line. These are deceptively simple poems with a lovely musicality that make the writer think hard about the perfect word choices.

Here’s an example of a cinquain poem, “November Night” by Adelaide Crapsey:

Listen… With faint dry sound, Like steps of passing ghosts, The leaves, frost-crisp’d, break from the trees And fall.

A triolet is a traditional French single-stanza poem of eight lines with a rhyme scheme of ABAAABAB; however, it only consists of five unique lines. The first line is repeated as the fourth and seventh line, and the second line is repeated as the very last line. Although simple, a well-written triolet will bring new depth and meaning to the repeated lines each time. Here’s an example of a classic triolet poem, “How Great My Grief” by Thomas Hardy:

How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee! Have the slow years not brought to view How great my grief, my joys how few, Nor memory shaped old times anew, Nor loving-kindness helped to show thee How great my grief, my joys how few, Since first it was my fate to know thee?

A dizain is another traditional form made up of just one ten-line stanza, and with each line having ten syllables (that’s an even hundred in total). The rhyme scheme for a dizain is ABABBCCDCD. This poetry type was a favorite of French poets in the 15th and 16th century, and many English poets adapted it into larger works. Here’s an great example of a dizain poem, “Names” by Brad Osborne:

If true that a rose by another name Holds in its fine form fragrance just as sweet If vivid beauty remains just the same And if other qualities are replete With the things that make a rose so complete Why bother giving anything a name Then on whom may I place deserved blame When new people’s names I cannot recall There seems to be an underlying shame So why do we bother with names at all

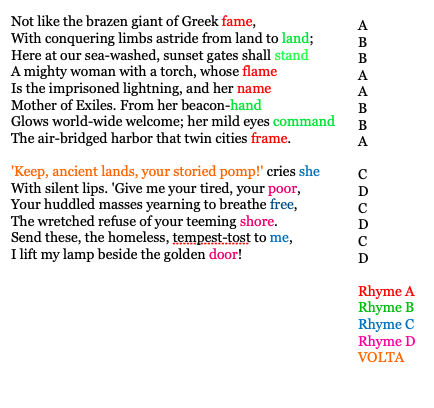

A sonnet is a lyric poem that always has fourteen lines. The oldest type of sonnet is the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet, which is broken into two stanzas of eight lines and six lines. The first stanza has a consistent rhyme scheme of ABBA ABBA and the second stanza has a rhyme scheme of either CDECDE or CDCDCD.

Later on, an ambitious bloke by the name of William Shakespeare developed the English sonnet (which later came to be known as the Shakespearean sonnet). It still has fourteen lines, but the rhyme scheme is different and it uses a rhythm called iambic pentameter. It has four distinctive parts, which might be separate stanzas or they might be all linked together. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

William Shakespeare is famous for using iambic pentameter in his sonnets, but you can experiment with different rhythms and see what works best for you. Here’s one of his most famous sonnets, Sonnet 18:

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st; So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

8. Blank verse

Blank verse is a type of poetry that’s written in a precise meter, usually iambic pentameter, but without rhyme. This is reminiscent of Shakespearean sonnets and many of his plays, but it reflects a movement that puts rhythm above rhyme.

Though each line of blank verse must be ten syllables, there’s no restriction on the amount of lines or individual stanzas. Here’s an excerpt from a poem in blank verse, the first stanza of “Frost at Midnight” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

The Frost performs its secret ministry, Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry Came loud—and hark, again! loud as before. The inmates of my cottage, all at rest, Have left me to that solitude, which suits Abstruser musings: save that at my side My cradled infant slumbers peacefully. ’Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs And vexes meditation with its strange And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood, This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood, With all the numberless goings-on of life, Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not; Only that film, which fluttered on the grate

9. Villanelle

A villanelle is a type of French poem made up of nineteen lines grouped into six separate stanzas. The first five stanzas have three lines each, and the last stanza has four lines. Each three-line stanza rhymes ABA, and the last one ABAA.

Villanelles tend to feature a lot of repetition, which lends them a musical quality; usually the very first and third lines become the alternating last lines of each following stanza. This can be a bit like putting a puzzle together. Here’s an example to show you how it looks: “My Darling Turns to Poetry at Night,” a famous villanelle by Anthony Lawrence:

My darling turns to poetry at night. What began as flirtation, an aside Between abstract expression and first light Now finds form as a silent, startled flight Of commas on her face—a breath, a word… My darling turns to poetry at night. When rain inspires the night birds to create Rhyme and formal verse, stanzas can be made Between abstract expression and first light. Her heartbeat is a metaphor, a late Bloom of red flowers that refuse to fade. My darling turns to poetry at night. I watch her turn. I do not sleep. I wait For symbols, for a sign that fear has died Between abstract expression and first light. Her dreams have night vision, and in her sight Our bodies leave ghostprints on the bed. My darling turns to poetry at night Between abstract expression and first light.

10. Paradelle

The paradelle is a complex and demanding variation of the villanelle, developed in France in the 11th century… except it wasn’t. It was, in fact, a hoax developed in the 20th century that got drastically out of hand. The American poet Billy Collins invented the paradelle as a satire of the popular villanelle and, like many happy accidents, the paradelle was embraced as a welcome challenge and is now part of contemporary poetry’s repertoire.

A paradelle is composed of four six-line stanzas. In each of the first three stanzas, the first two lines must be the same, the second two lines must be the same, and the final two lines must contain every word from the first and third lines, and only those words, rearranged in a new order. The fourth and final stanza must contain every word from the fifth and sixth lines of the first three stanzas, and only those words, again rearranged in a new order.

11th-century relic or not, this poetry form is a great exercise for playing with words. Here’s an excerpt from the original paradelle that started it all, the first stanzas of “Paradelle for Susan” by Billy Collins:

I remember the quick, nervous bird of your love. I remember the quick, nervous bird of your love. Always perched on the thinnest highest branch. Always perched on the thinnest highest branch. Thinnest love, remember the quick branch. Always nervous, I perched on you highest bird the. It is time for me to cross the mountain. It is time for me to cross the mountain. And find another shore to darken with my pain. And find another shore to darken with my pain. Another pain for me to darken the mountain. And find the time, cross my shore, to with it is to. The weather warm, the handwriting familiar. The weather warm, the handwriting familiar. Your letter flies from my hand into the waters below. Your letter flies from my hand into the waters below. The familiar water below my warm hand. Into handwriting your weather flies you letter the from the. I always cross the highest letter, the thinnest bird. Below the waters of my warm familiar pain, Another hand to remember your handwriting. The weather perched for me on the shore. Quick, your nervous branch flew from love. Darken the mountain, time and find was my into it was with to to.

11. Sestina

A sestina is a complex French poetry form (a real one, this time) composed of thirty-nine lines in seven stanzas—six stanzas of six lines each, and one stanza of three lines. Each word at the end of each line in the first stanza then gets repeated at the end of each line in each following stanza, but in a different order.

Some poets use favorite metres or rhyme schemes in their sestina poems, but you don’t have to. The classic form of a sestina is:

First stanza: ABCDEF; each letter represents the word at the end of each line.

Second stanza: FAEBDC

Third stanza: CFDABE

Fourth stanza: ECBFAD

Fifth stanza: DEACFB

Sixth stanza: BDFECA

Seventh stanza: ACE or ECA

Here’s an excerpt from a modern example of a sestina, the first stanzas of “A Miracle For Breakfast” by Elizabeth Bishop. Looking at the first two stanzas, you can see that the repeated end words match the mixed-up letter guide above.

At six o’clock we were waiting for coffee, waiting for coffee and the charitable crumb that was going to be served from a certain balcony like kings of old, or like a miracle. It was still dark. One foot of the sun steadied itself on a long ripple in the river. The first ferry of the day had just crossed the river. It was so cold we hoped that the coffee would be very hot, seeing that the sun was not going to warm us; and that the crumb would be a loaf each, buttered, by a miracle. At seven a man stepped out on the balcony.

A rondel is a French type of poetry made of three stanzas: the first two are four lines long, and the third is five or six lines long. The first two lines of the poems are refrains which are repeated as the last two lines of the following two stanzas—although sometimes the poet will choose only one line to repeat at the very last line.

Rondels usually use a ABBA ABAB ABBAA rhyme scheme, but they can be written in any meter. Here’s an example of a traditional rondel poem, “The Wanderer” by Henry Austin Dobson:

Love comes back to his vacant dwelling— The old, old Love that we knew of yore! We see him stand by the open door, With his great eyes sad, and his bosom swelling. He makes as though in our arms repelling, He fain would lie as he lay before;— Love comes back to his vacant dwelling, The old, old Love that we knew of yore! Ah, who shall help us from over-spelling That sweet, forgotten, forbidden lore! E’en as we doubt in our heart once more, With a rush of tears to our eyelids welling, Love comes back to his vacant dwelling.

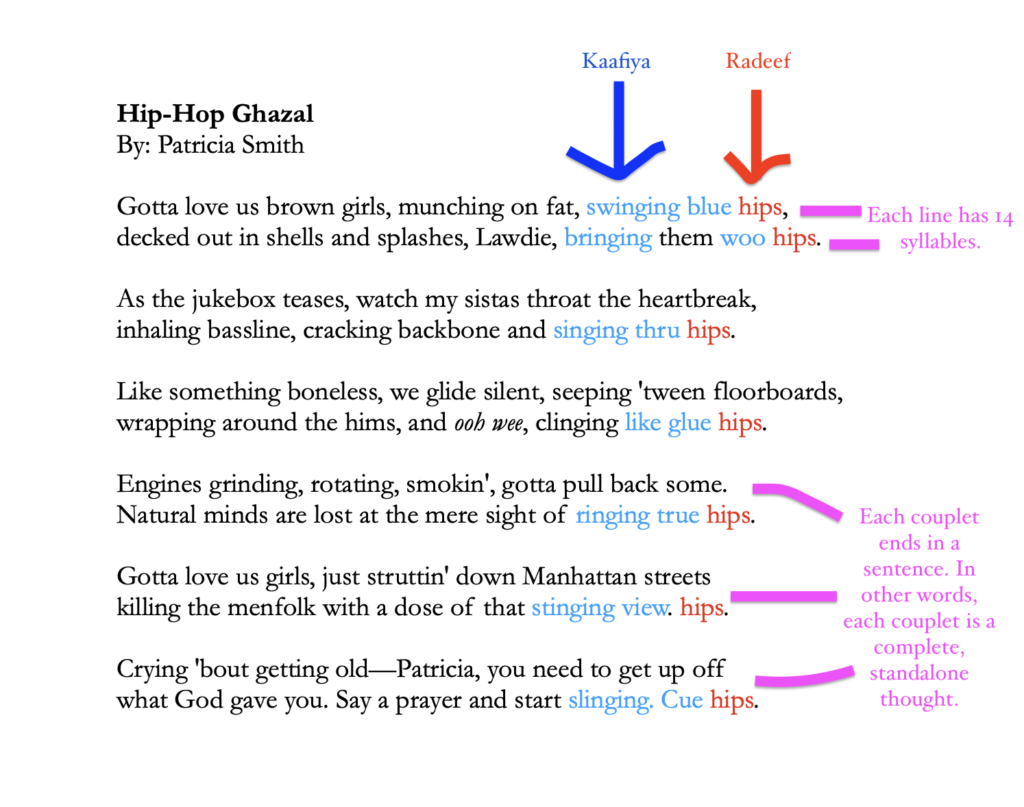

A ghazal is an old Arabic poetry form consisting of at least ten lines, but no more than thirty, all written in two-line stanzas called couplets. The first two lines of a ghazal end with the same word, but the words just preceding the last lines will rhyme. From this point on, the second line of each couplet will have the same last word, and the word just before it will rhyme with the others.

Ghazals are traditionally a poem of love and longing, but they can be written about any feeling or idea. Here’s an excerpt from a ghazal poem, the first stanzas of “Ghazal of the Better-Unbegun” by Heather McHugh:

Too volatile, am I? too voluble? too much a word-person? I blame the soup: I’m a primordially stirred person. Two pronouns and a vehicle was Icarus with wings. The apparatus of his selves made an absurd person. The sound I make is sympathy’s: sad dogs are tied afar. But howling I become an ever more unheard person.

14. Golden shovel

A golden shovel poem is a more recent poetry form that was developed by poet Terrance Hayes and inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks. Though it’s much newer than many of the types of poetry on this list, it has been enthusiastically embraced in contemporary poetry.

It’s a bit like an acrostic-style poem in that it hides a secret message: the last word of every line of a golden shovel poem is a word from another poem’s title or line, or a saying or headline you want to work with.

For example, if you want to write a golden shovel poem about the line, “dead men tell no tales,” the first line of your poem would end in “dead,” the second line in “men,” and so on until you can read your entire message along the right-hand side of the poem.

Here’s an excerpt from Terrance Hayes’s poem that started the golden shovel trend:

When I am so small Da’s sock covers my arm, we cruise at twilight until we find the place the real men lean, bloodshot and translucent with cool. His smile is a gold-plated incantation as we drift by women on bar stools, with nothing left in them but approachlessness. This is a school I do not know yet. But the cue sticks mean we are rubbed by light, smooth as wood, the lurk of smoke thinned to song. We won’t be out late.

15. Palindrome

Palindrome poems, also called “mirror poems,” are poems that begin repeating backwards halfway through, so that the first line and the last line are the same, the second line and the second-to-last line are the same, and so on.

They’re a challenging yet fun way to show two sides of the same story. Here’s an example of a palindrome poem, “On Reflection” by Kristin Bock:

Far from the din of the articulated world, I wanted to be content in an empty room— a barn on the hillside like a bone, a limbo of afternoons strung together like cardboard boxes, to be free of your image— crown of bees, pail of black water staggering through the pitiful corn. I can’t always see through it. The mind is a pond layered in lilies. The mind is a pond layered in lilies. I can’t always see through it staggering through the pitiful corn. Crown of Bees, Pail of Black Water, to be of your image— a limbo of afternoons strung together like cardboard boxes, a barn on the hillside like a bone. I wanted to be content in an empty room far from the din of the articulated world.

An ode is a poetic form of celebration used to honor a person, thing, or idea. They’re often overflowing with intense emotion and powerful imagery.

Odes can be used in conjunction with formal meters and rhyme schemes, but they don’t have to be; often poets will favor internal rhymes instead, to give their ode a sense of rhythm.

This is a more open-ended poetry type you can use to show your appreciation for something or someone. Here’s an excerpt from one of the most famous and beautiful odes, written in celebration of autumn: “To Autumn” by John Keats:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; Conspiring with him how to load and bless With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eaves run; To bend with apples the mossed cottage-trees, And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core; To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells With a sweet kernel; to set budding more, And still more, later flowers for the bees, Until they think warm days will never cease, For Summer has o’er-brimmed their clammy cells.

An elegy is similar to an ode in that it celebrates a person or idea, but in this instance is the poem centers around something that has died or been lost.

There’s a tradition among poets to write elegies for one another once another poet has died. Sometimes these are obvious memoriams of a deceased person, and other times the true meaning will be hidden behind layers of symbolism and metaphor.

Like the ode, there’s no formal meter or rhyme scheme in an elegy, though you can certainly experiment with using them.

Here’s an excerpt of an elegy written by one poet for another, “In Memory of W. B. Yeats” by W. H. Auden:

He disappeared in the dead of winter: The brooks were frozen, the airports almost deserted, And snow disfigured the public statues; The mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day. What instruments we have agree The day of his death was a dark cold day. Far from his illness The wolves ran on through the evergreen forests, The peasant river was untempted by the fashionable quays; By mourning tongues The death of the poet was kept from his poems.

18. Ekphrasis

Ekphrastic poetry is a little bit like an ode, as it is also written in celebration of something. Ekphrasis, however, is very specific as it’s used to draw attention to a work of art—usually visual art, but it could be something like a song or a work of fiction too. Sometimes ekphrastic poems and odes can overlap, like in John Keats’ “Ode to a Grecian Urn”—an ekphrastic ode.

Ekphrastic poems are most often written about paintings, but it can also be about sculptures, dance, or even theatrical performances.

Ekphrasis has no set meter or rhyme scheme, but some poets like to use them. Here’s an excerpt from an ekphrastic poem, “The Starry Night” by Anne Sexton, in celebration of Van Gogh’s painting:

The town does not exist except where one black-haired tree slips up like a drowned woman into the hot sky. The town is silent. The night boils with eleven stars. Oh starry starry night! This is how I want to die. It moves. They are all alive. Even the moon bulges in its orange irons to push children, like a god, from its eye. The old unseen serpent swallows up the stars. Oh starry starry night! This is how I want to die.

19. Pastoral

Pastoral poetry can take any meter or rhyme scheme, but it focuses on the beauty of nature. These poems draw attention to idyllic settings and romanticize the idea of shepherds and agriculture laborers living in harmony with the natural world.

Often these traditional pastoral poems carry a religious overtone, suggesting that by bringing oneself closer to nature they were also becoming closer to their spirituality. They can be written in free verse, or in poetic structure. Here’s an excerpt from a famous pastoral poem, “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” by Christopher Marlowe:

Come live with me and be my love, And we will all the pleasures prove That valleys, groves, hills, and fields, Woods, or steepy mountain yields. And we will sit upon the rocks, Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks, By shallow rivers to whose falls Melodious birds sing madrigals.

An epic poem is a grand, overarching story written in verse—they’re the novels of the poetry world. This is sometimes called ballad poetry, or narrative poetry. Before stories were written as novels and short stories and then, later, screenplays, all of our classic tales would be written as a narrative poem.

Experimenting with epic poems, such as writing a short story all in verse, is a great way to give your writer’s muscles a workout. These don’t have a specific rhyme scheme or metre, although many classic epic poems do use them to give a sense of rhythm and unity to the piece.

Here’s an excerpt from one of our oldest surviving epic poems, “Beowulf,” translated from old English by Frances B. Gummere:

Lo, praise of the prowess of people-kings of spear-armed Danes, in days long sped, we have heard, and what honor the athelings won! Oft Scyld the Scefing from squadroned foes, from many a tribe, the mead-bench tore, awing the earls. Since erst he lay friendless, a foundling, fate repaid him: for he waxed under welkin, in wealth he throve, till before him the folk, both far and near, who house by the whale-path, heard his mandate, gave him gifts: a good king he!

(Irish poet Seamus Heaney has also completed an even more modern translation for the layperson.)

A ballad is similar to an epic in that it tells a story, but it’s much shorter and a bit more structured. This poetry form is made up of four-line stanzas (as many as are needed to tell the story) with a rhyme scheme of ABCB.

Ballads were originally meant to be set to music, which is where we get the idea of our slow, sultry love song ballads today. A lot of traditional ballads are all in dialogue, where two characters are speaking back and forth.

Here’s an excerpt from a traditional ballad poem, “La Belle Dame sans Merci” by John Keats:

O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, Alone and palely loitering? The sedge has withered from the lake, And no birds sing. O what can ail thee, knight-at-arms, So haggard and so woe-begone? The squirrel’s granary is full, And the harvest’s done.

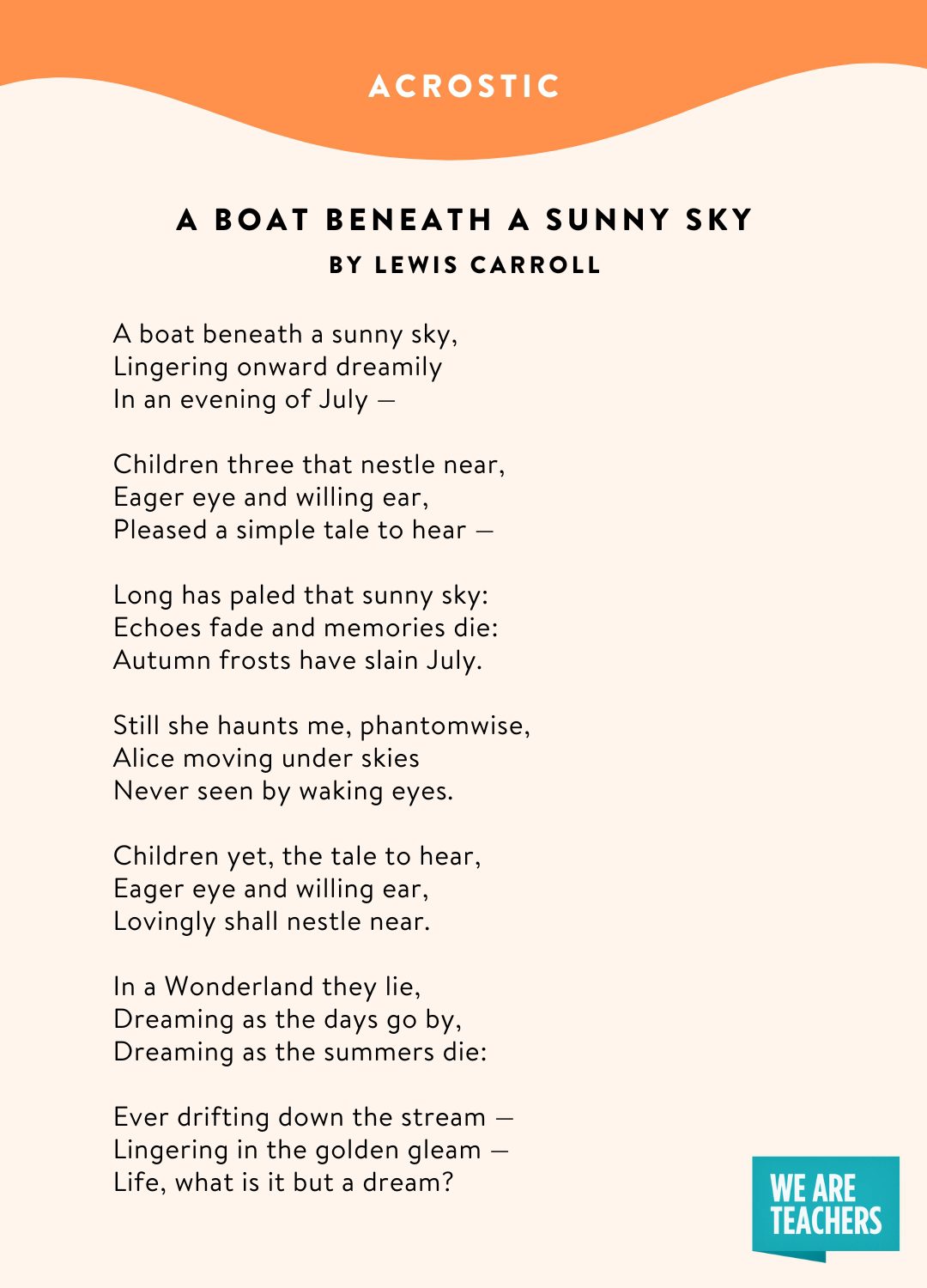

22. Acrostic

In acrostic poems, certain letters of each line spell out a word or message. Usually the letters that spell the message will be the first letter of each line, so that you can read the secret word right down the margin; however, you can also use the letters at the end or down the middle of the lines to hide a secret message. Acrostic poems are especially popular with children and are sometimes called “name poems.”

Here’s an example of an acrostic poem, “A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky” by Lewis Carroll. The first letter of each line spells out “Alice Pleasance Liddell,” who was a young friend of Carroll’s and the inspiration behind Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland .

A boat beneath a sunny sky, L ingering onward dreamily I n an evening of July— C hildren three that nestle near, E ager eye and willing ear, P leased a simple tale to hear— L ong has paled that sunny sky: E choes fade and memories die: A utumn frosts have slain July. S till she haunts me, phantomwise, A lice moving under skies N ever seen by waking eyes. C hildren yet, the tale to hear, E ager eye and willing ear, L ovingly shall nestle near. I n a Wonderland they lie, D reaming as the days go by, D reaming as the summers die: E ver drifting down the stream— L ingering in the golden gleam— L ife, what is it but a dream?

23. Concrete

A concrete poem, sometimes called a shape poem, is a visual poem structure where the shape of the poem resembles its content or message. These are another favorite with children, although they can be used to communicate powerful adult ideas, too.

When writing concrete poetry, you can experiment with different fonts, sizes, and even colors to create your visual poem. Here’s an example of a concrete poem, “Sonnet in the Shape of a Potted Christmas Tree” by George Starbuck:

* O fury- bedecked! O glitter-torn! Let the wild wind erect bonbonbonanzas; junipers affect frostyfreeze turbans; iciclestuff adorn all cuckolded creation in a madcap crown of horn! It’s a new day; no scapegrace of a sect tidying up the ashtrays playing Daughter-in-Law Elect; bells! bibelots! popsicle cigars! shatter the glassware! a son born now now while ox and ass and infant lie together as poor creatures will and tears of her exertion still cling in the spent girl’s eye and a great firework in the sky drifts to the western hill.

24. Prose poem

A prose poem combines elements of both prose writing and poetry into something new. Prose poems don’t have shape and line breaks in the way that traditional poems do, but they make use of poetic devices like meter, internal rhyme, alliteration, metaphor, imagery, and symbolism to create a snapshot of prose that reads and feels like a poem.

Here’s an example of a prose poem, “Be Drunk” by Charles Baudelaire:

You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it—it’s the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk. But on what? Wine, poetry or virtue, as you wish. But be drunk. And if sometimes, on the steps of a palace or the green grass of a ditch, in the mournful solitude of your room, you wake again, drunkenness already diminishing or gone, ask the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock, everything that is flying, everything that is groaning, everything that is rolling, everything that is singing, everything that is speaking… ask what time it is and wind, wave, star, bird, clock will answer you: “It is time to be drunk! So as not to be the martyred slaves of time, be drunk, be continually drunk! On wine, on poetry or on virtue as you wish.”

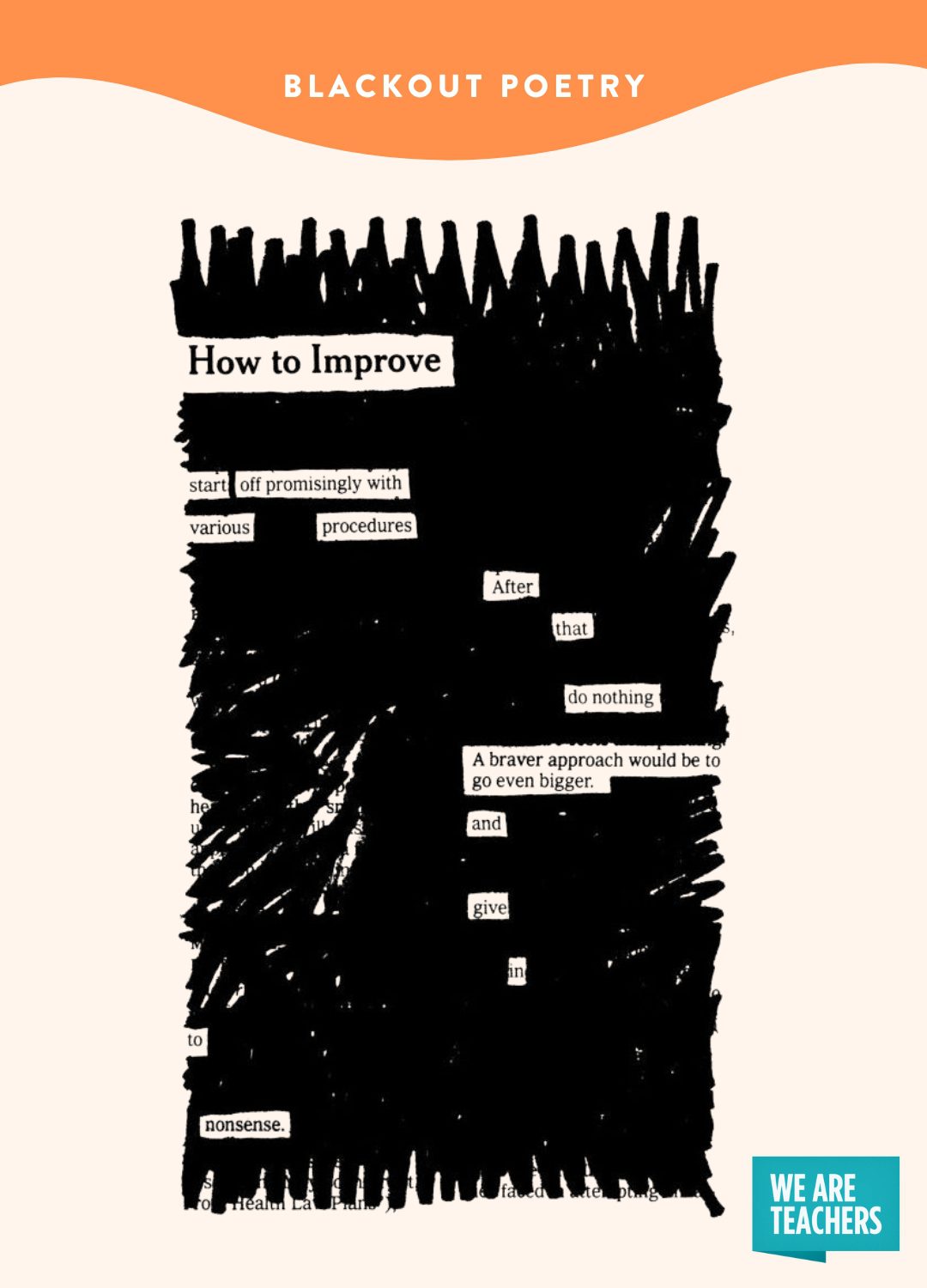

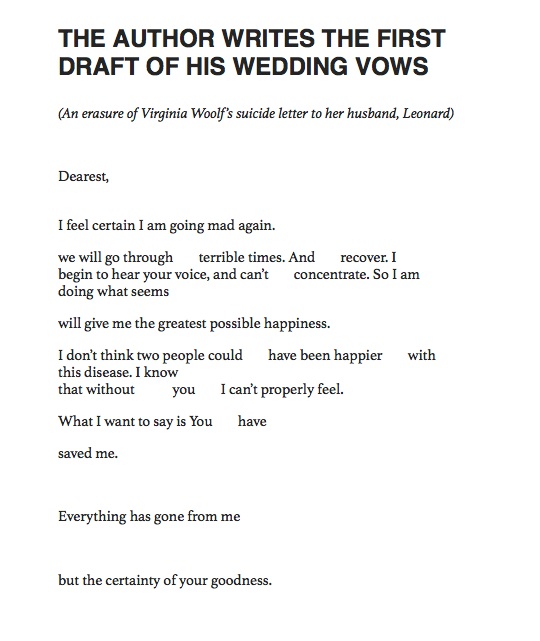

25. Found poetry

Found poetry is a poem made up of a composite of external quotations. This may be from poems, beloved works of literature, newspaper articles, instruction manuals, or political manifestos. You can copy out pieces of text, or you can cut out different words to make a visual collage effect.

Another form of found poetry is blackout poetry, where words are crossed out and removed from an external source to create a new meaning.

These can be a great way to find new or contrasting meaning in everyday life, but always be sure to reference what sources your poem came from originally to avoid plagiarism. Here’s an example of a found poem, “Testimony” by Charles Reznikoff, cut up from law reports between 1885 and 1915:

Amelia was just fourteen and out of the orphan asylum; at her first job—in the bindery, and yes sir, yes ma’am, oh, so anxious to please. She stood at the table, her blond hair hanging about her shoulders, “knocking up” for Mary and Sadie, the stichers (“knocking up” is counting books and stacking them in piles to be taken away).

A nonce poem is a DIY poem structure intended for one-time use to challenge yourself as a writer, or just to try something new. It’s a formal, rigid, standardized poetry form that’s brand new to the world.

For example, you might say, “I’m going to write a poem starting with a three-line stanza, then two four-line stanzas, then another three-line stanza, and each line is going to be eight syllables except the first and last line of the poem which are each going to have eleven syllables, and the last word of every stanza will be true rhymes and the first word of every stanza will be slant rhymes.” And then you do it, just to see if you can.

Nonce poems are a great way to stretch your creativity and language skills to their limit. Then, like Terrance Hayes’s “Golden Shovel,” or Billy Collins’ “Paradelle,” your nonce poem might even catch on! Here’s an excerpt from a nonce poem, “And If I Did, What Then?” by George Gascoigne:

Are you aggriev’d therefore? The sea hath fish for every man, And what would you have more?” Thus did my mistress once, Amaze my mind with doubt; And popp’d a question for the nonce To beat my brains about.

27. Free verse

Free verse is the type of poetry most favored by contemporary poets; it has no set meter, rhyme scheme, or structure, but allows the poet to feel out the content of the poem as they go.

Poets will often still use rhythmic literary devices such as assonance and internal rhymes, but it won’t be bound up with the same creative restraints as more structured poetry. However, even poets that work solely in free verse will usually argue that it’s beneficial to first work up your mastery of language through exercises in more structured poetry forms.

Here’s an example of a poem in free verse, an excerpt from “On Turning Ten,” by Billy Collins:

The whole idea of it makes me feel like I’m coming down with something, something worse than any stomach ache or the headaches I get from reading in bad light— a kind of measles of the spirit, a mumps of the psyche, a disfiguring chicken pox of the soul.

3 ways poem structure will make you a better writer

Maybe you’ve fallen in love with formal rhymed poetry, or maybe you think that for you, free verse is the way to go. Either way, it’s good training for a writer to experiment with poetry structure for a few different reasons.

1. Using poetic form will teach you about poetic devices

Using poetic form will open up your world to a huge range of useful poetic devices like assonance, chiasmus, and epistrophe, as well as broader overarching ideas like metaphor, imagery, and symbolism. We talk about these poetic devices a lot in poetry forms, but just about all of them can be used effectively in prose writing, too!

Paying attention to poetic form takes your mastery of language to a whole new level. Then you can take this skill set and apply it to your writing in a whole range of mediums.

2. Writing poems with structure teaches you how to use rhythm

Rhythm is one of the core concepts of all poetry. Rhymes and formal meter are two ways to capture rhythm in your poems, but even in free verse poetry that lacks a formal poetic structure, the key to good poetry is a smooth and addictive rhythm that makes you feel the words in your bones.

Once you start experimenting with poetry forms, you’ll find that you’ll develop an inner ear for the rhythm of language. This rhythmic sense translates into beautiful sentence structure and cadence in other types of writing, from short stories and novels, to marketing copy, to comic books. Rhythm is what makes your words a joy to read.

3. Formal poetry helps you increase your vocabulary and refine your word choice

No matter what you’re writing, specificity is a game changer when it comes to getting a point across to your reader. With the English language being well-populated with nice, easy syllables, many new writers fall into the bad habit of choosing words that are just kind of okay, instead of the exact right word for that moment.

Writing formal poetry forces you to not only expand your vocabulary to find the right word to fit the rhyme scheme or rhythm, but to weigh each word and examine it from all angles before awarding it a place in your poem. This way, when you move into other forms of writing, you’ll carry good habits and a deep respect for language into your work.

Start writing different types of poetry

Learning about different types of poems for the first time can be a bit like opening a floodgate into a whole new way of living. Whether you prefer free verse poetry, lyric poetry, romantic Shakespearean sonnets, short philosophical haiku, or even coming up with your own nonce poetry structure, you’ll find that writing poetry challenges your writer’s muscles in ways you never would have expected. Next time you’re in a creative rut, trying experimenting with poetry forms to get the words flowing in a whole new way.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Short Story Submissions: How to Publish a Short Story or Poem

Poetic Devices List: 27 Main Poetic Devices with Examples

How to Write a Haiku (With Haiku Examples)

Types of Poems

All types of poems, forms or formats, with definitions and examples. See the top 10 types of poems and learn about popular forms of poetry like acrostic , haiku , lyric , narrative , and rhyme and more. Learn rhyme schemes, structure, form, stanzas, style, rhythm, and meter , etc. for all forms of poetry.

See also: Top 20 Most Popular Types of Poetry Ranked | Poetry Terminology | Types of Narrative Poetry | How to Write a Poem - 10 Steps

Top 10 Types of Poems, Forms or Formats

(10) | concrete - poems | definition, (9) | diamante - poems | definition, (8) | lyric - poems | definition, (7) | cinquain - poems | definition, (6) | free verse - poems | definition, (5) | limerick - poems | definition, (4) | elegy - poems | definition, (3) | ode - poems | definition, (2) | acrostic - poems | definition, (1) | haiku - poems | definition, a form of literature.

Poetry is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities of language to evoke emotion and convey meaning. It has been a part of human culture for centuries and has evolved into various types, forms, and formats. Let's explore the different styles and genres of poetry and how they are analyzed.

Types of Poetry

There are various types of poetry, each with its own unique characteristics and structures. Some common types include sonnets, haikus, ballads, free verse, and epic poetry. Sonnets often follow a specific rhyme scheme and have 14 lines, while haikus are much shorter and consist of three lines with a specific syllable pattern. Ballads are narrative poems that tell a story, free verse has no specific rhyme or meter, and epic poetry is typically long and reflects heroic themes. These are just a few examples of the diverse range of poetry types, each offering different ways to convey emotions and ideas.

Lyric Poetry

Lyric poetry is a type of poetry that expresses personal emotions or feelings. It is often short and musical in nature, with a focus on the speaker's thoughts and emotions. Examples of lyric poetry include sonnets, odes, and elegies.

Narrative Poetry

Narrative poetry tells a story through verse. It often follows a specific structure and includes elements such as plot, characters, and setting. Examples of narrative poetry include epics, ballads, and epistles.

Dramatic Poetry

Dramatic poetry is meant to be performed or spoken aloud. It often includes dialogue and is written in a dramatic or theatrical style. Examples of dramatic poetry include monologues, soliloquies, and verse dramas.

Forms of Poetry

Poetic form can be defined in many ways, but it is essentially a type of poem that is defined by physical structure, rhythm, and other elements. It has a specific style or set of rules that must be used when writing. Even the literal shape that a poem takes on paper can matter when it comes to the type of poem. The line length, number of syllables , and subject matter are all important parts of poetic form.

A sonnet is a 14-line poem that follows a specific rhyme scheme and structure. It originated in Italy and has been used by poets such as William Shakespeare and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. There are two main types of sonnets: the Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnet and the English (or Shakespearean) sonnet.