Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

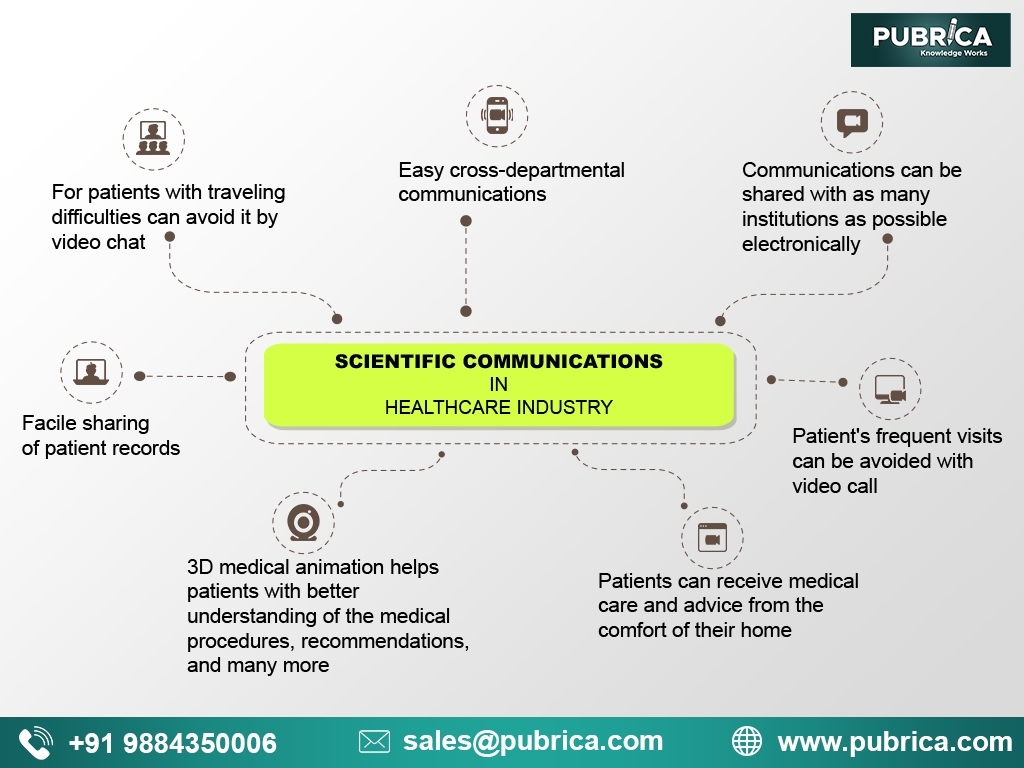

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

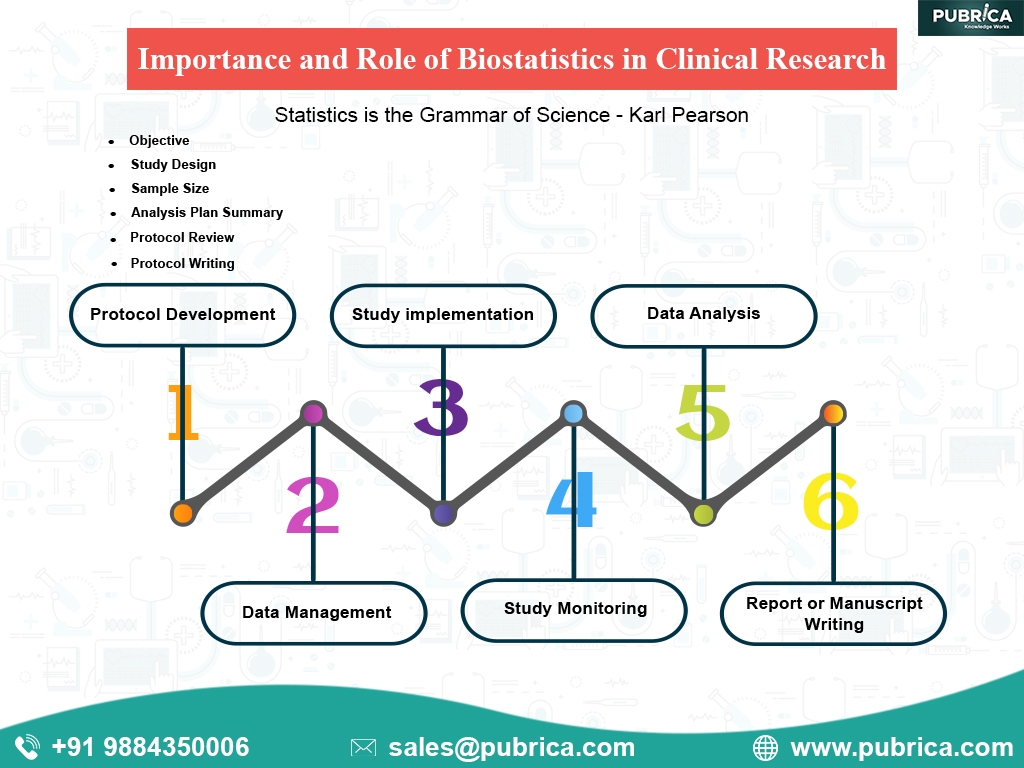

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

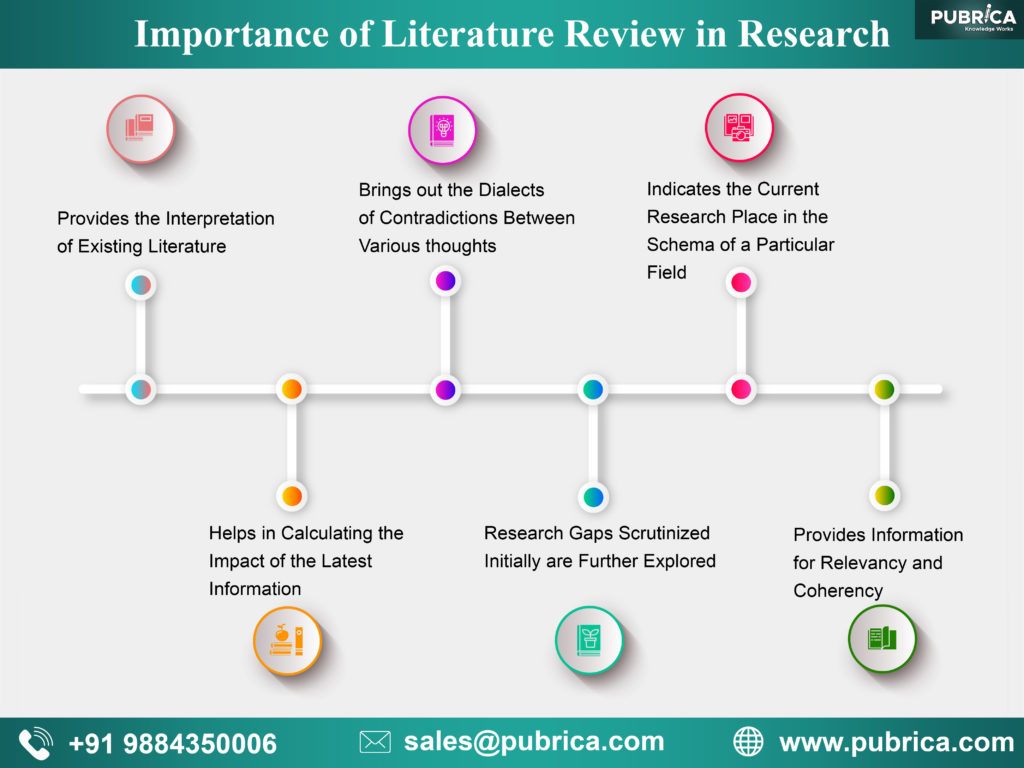

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Literature Review: Purpose of a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Purpose of a Literature Review

- Work in Progress

- Compiling & Writing

- Books, Articles, & Web Pages

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Departmental Differences

- Citation Styles & Plagiarism

- Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Provide a foundation of knowledge on a topic

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication and give credit to other researchers

- Identify inconstancies: gaps in research, conflicts in previous studies, open questions left from other research

- Identify the need for additional research (justifying your research)

- Identify the relationship of works in the context of their contribution to the topic and other works

- Place your own research within the context of existing literature, making a case for why further study is needed.

Videos & Tutorials

VIDEO: What is the role of a literature review in research? What's it mean to "review" the literature? Get the big picture of what to expect as part of the process. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license. License, credits, and contact information can be found here: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/litreview/

Elements in a Literature Review

- Elements in a Literature Review txt of infographic

- << Previous: Literature Review

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Oct 19, 2023 12:07 PM

- URL: https://uscupstate.libguides.com/Literature_Review

- Become Involved |

- Give to the Library |

- Staff Directory |

- UNF Library

- Thomas G. Carpenter Library

Conducting a Literature Review

Benefits of conducting a literature review.

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Summary of the Process

- Additional Resources

- Literature Review Tutorial by American University Library

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It by University of Toronto

- Write a Literature Review by UC Santa Cruz University Library

While there might be many reasons for conducting a literature review, following are four key outcomes of doing the review.

Assessment of the current state of research on a topic . This is probably the most obvious value of the literature review. Once a researcher has determined an area to work with for a research project, a search of relevant information sources will help determine what is already known about the topic and how extensively the topic has already been researched.

Identification of the experts on a particular topic . One of the additional benefits derived from doing the literature review is that it will quickly reveal which researchers have written the most on a particular topic and are, therefore, probably the experts on the topic. Someone who has written twenty articles on a topic or on related topics is more than likely more knowledgeable than someone who has written a single article. This same writer will likely turn up as a reference in most of the other articles written on the same topic. From the number of articles written by the author and the number of times the writer has been cited by other authors, a researcher will be able to assume that the particular author is an expert in the area and, thus, a key resource for consultation in the current research to be undertaken.

Identification of key questions about a topic that need further research . In many cases a researcher may discover new angles that need further exploration by reviewing what has already been written on a topic. For example, research may suggest that listening to music while studying might lead to better retention of ideas, but the research might not have assessed whether a particular style of music is more beneficial than another. A researcher who is interested in pursuing this topic would then do well to follow up existing studies with a new study, based on previous research, that tries to identify which styles of music are most beneficial to retention.

Determination of methodologies used in past studies of the same or similar topics. It is often useful to review the types of studies that previous researchers have launched as a means of determining what approaches might be of most benefit in further developing a topic. By the same token, a review of previously conducted studies might lend itself to researchers determining a new angle for approaching research.

Upon completion of the literature review, a researcher should have a solid foundation of knowledge in the area and a good feel for the direction any new research should take. Should any additional questions arise during the course of the research, the researcher will know which experts to consult in order to quickly clear up those questions.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2022 8:54 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unf.edu/litreview

- Research Process

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 423.7K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

- Manuscript Preparation

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

5 Reasons the Literature Review Is Crucial to Your Paper

3-minute read

- 8th November 2016

People often treat writing the literature review in an academic paper as a formality. Usually, this means simply listing various studies vaguely related to their work and leaving it at that.

But this overlooks how important the literature review is to a well-written experimental report or research paper. As such, we thought we’d take a moment to go over what a literature review should do and why you should give it the attention it deserves.

What Is a Literature Review?

Common in the social and physical sciences, but also sometimes required in the humanities, a literature review is a summary of past research in your subject area.

Sometimes this is a standalone investigation of how an idea or field of inquiry has developed over time. However, more usually it’s the part of an academic paper, thesis or dissertation that sets out the background against which a study takes place.

There are several reasons why we do this.

Reason #1: To Demonstrate Understanding

In a college paper, you can use a literature review to demonstrate your understanding of the subject matter. This means identifying, summarizing and critically assessing past research that is relevant to your own work.

Reason #2: To Justify Your Research

The literature review also plays a big role in justifying your study and setting your research question . This is because examining past research allows you to identify gaps in the literature, which you can then attempt to fill or address with your own work.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Reason #3: Setting a Theoretical Framework

It can help to think of the literature review as the foundations for your study, since the rest of your work will build upon the ideas and existing research you discuss therein.

A crucial part of this is formulating a theoretical framework , which comprises the concepts and theories that your work is based upon and against which its success will be judged.

Reason #4: Developing a Methodology

Conducting a literature review before beginning research also lets you see how similar studies have been conducted in the past. By examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research, you can thus make sure you adopt the most appropriate methods, data sources and analytical techniques for your own work.

Reason #5: To Support Your Own Findings

The significance of any results you achieve will depend to some extent on how they compare to those reported in the existing literature. When you come to write up your findings, your literature review will therefore provide a crucial point of reference.

If your results replicate past research, for instance, you can say that your work supports existing theories. If your results are different, though, you’ll need to discuss why and whether the difference is important.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

9-minute read

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2024

“We know what we should be eating, but we don’t always do that.” How and why people eat the way they do: a qualitative study with rural australians

- Nina Van Dyke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8872-3451 1 ,

- Michael Murphy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0434-4567 2 &

- Eric J. Drinkwater ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9594-9360 3

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1240 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

313 Accesses

Metrics details

There is evidence that most people are aware of the importance of healthy eating and have a broad understanding regarding types of food that enhance or detract from health. However, greater health literacy does not always result in healthier eating. Andreasen’s Social Marketing Model and Community-Based Social Marketing both posit that, in order to change health behaviours, it is crucial to understand reasons for current behaviours and perceived barriers and benefits to improved behaviours. Limited research has been conducted, however, that explores these issues with general populations. This study aimed to help address this gap in the evidence using a qualitative methodology.

Three group discussions were conducted with a total of 23 participants: (1) young women aged 18–24 with no children; (2) women aged 35–45 with primary school aged children; and (3) men aged 35–50 living with a partner and with pre- or primary school aged children. The discussions took place in a regional centre of Victoria, Australia. Transcriptions were thematically analysed using an inductive descriptive approach and with reference to a recent integrated framework of food choice that identified five key interrelated determinants: food– internal factors; food– external factors; personal-state factors; cognitive factors; and sociocultural factors.

We found that food choice was complex, with all five determinants evident from the discussions. However, the “Social environment” sub-category of “Food-external factors”, which included family, work, and social structures, and expectations (or perceived expectations) of family members, colleagues, friends, and others, was particularly prominent. Knowledge that one should practice healthy eating, which falls under the “Cognitive factor” category, while seen as an aspiration by most participants, was often viewed as unrealistic, trumped by the need and/or desire for convenience, a combination of Food-external factor: Social environment and Personal-state factor: Psychological components.

Conclusions

We found that decisions regarding what, when, and how much to eat are seen as heavily influenced by factors outside the control of the individual. It appears, therefore, that a key to improving people’s eating behaviours is to make it easy to eat more healthfully, or at least not much harder than eating poorly.

Peer Review reports

A plethora of recommendations exist regarding how people should eat to maintain better health [e.g., 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Moreover, there is evidence that most people have a reasonable awareness of connections between healthier foods and better health, and a broad understanding regarding types of food that enhance or detract from health [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. However, greater health literacy does not always result in healthier eating [ 7 – 8 ].

Evidence suggests that public health and health-promotion interventions with a theoretical basis are more effective than those lacking such a foundation [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. Andreasen’s Social Marketing Model [ 12 ] posits that a primary focus for behaviour change is on learning what people want and need rather than trying to persuade them to adopt particular behaviours or goals. Community-based social marketing sets out six steps necessary for enacting societal behavioural change; step two is to understand perceived barriers and benefits to develop interventions [ 13 ].

Limited research has been conducted, however, that explores how people in the general population eat and their perceptions regarding why they eat the way they do [ 14 – 15 ]. Although several recent papers have examined barriers to and enablers of healthier eating [e.g., 16 ], relatively few are from the perspective of the consumers themselves [e.g., 17 – 18 ] or are narrowly focused on particular types of healthy consumption [e.g., 19 ].

Healthy eating: knowing vs. doing

Food-based dietary guidelines are available for more than 90 countries globally. Although there is some variation across guidelines regarding particular foods, there is broad agreement to consume a variety of foods; consume some foods in higher proportion than others; consume fruits, vegetables, and legumes; and to limit sugar, fat, and salt [ 20 , 21 , 22 ].

There is mixed evidence regarding whether most people broadly understand what constitutes a healthy diet and believe they should try to eat healthily. A systematic review of the psychological literature on healthy diet, for example, found that the public has a “remarkably accurate” understanding of healthy nutrition and that this understanding reflects key dietary guidelines [ 23 ]. Focus groups with participants segmented by age and gender found that most participants were aware of the type of foods that contributed to a healthy diet and the importance of achieving a healthy balance within a diet [ 24 ]. Other studies, however, have found evidence of confusion and misperceptions amongst the general public. A cross-sectional survey of 1,097 adults aged 18–64 in Victoria, Australia and 135 professional dietitians, for example, found large discrepancies in which of various food items were considered healthy. Amongst women and those living in higher socio-economic areas, however, views were similar [ 25 ]. An earlier survey of Swiss consumers found that between 3% and 38% incorrectly answered procedural nutrition knowledge items. Again, this overall finding differed by sub-groups [ 26 ].

However, this knowledge does not necessarily result in healthy eating [ 27 ]. A systematic review of the relationship between nutrition knowledge and dietary intake found that the majority of studies reported significant, positive associations, but the relationship was weak ( r < 0.5 ) and mostly involved slightly higher intake of fruits and vegetables. The authors also noted that study quality ranged widely and that most participants were female and with a tertiary education, with limited representation of individuals from lower socio-economic status background [ 28 ]. A qualitative study with adults in New Zealand reported “the impossible rightness of healthy eating”, meaning that the people in their study knew they should be eating healthfully, but simultaneously felt that this was very difficult or impossible to do [ 29 ]. A Canadian study argued that the concept of "food literacy" needed to extend beyond nutritional recommendations and cooking lessons to fostering connections between food, people, health, and the environment to bridge this gap between knowing and doing [ 30 ].

Theoretical frameworks

Andreasen’s Social Marketing Model [ 12 ] presents behaviour change as the dependent variable, influenced by four classes of independent variables: (1) the attractiveness of behavioural alternatives, (2) community pressures, (3) the cooperation of critical supporting agencies, and (4) marketing efforts. Of specific relevance to this study, Andreasen [ 12 ] posits that a primary focus for behaviour change is on learning what people want and need rather than trying to persuade them to adopt particular behaviours or goals.

Also relevant is Community-Based Social Marketing. Community-Based Social Marketing is based on six steps. Step one is to identify the target behaviour– in this case, unhealthy eating. Step two is to understand perceived barriers and benefits to develop interventions [ 13 ]. It is this second step that we focus on in this study.

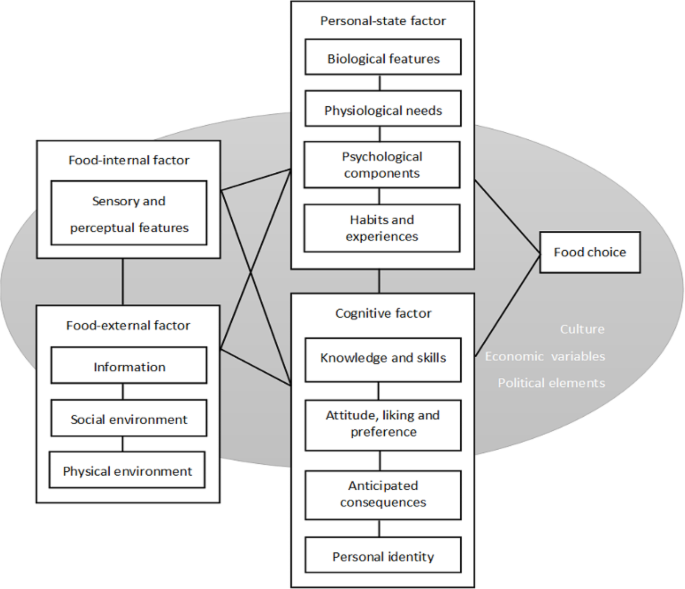

- Food choice

Decisions regarding what food to eat, when, and in what quantity are “frequent, multifaceted, situational, dynamic, and complex” [ 31 ]. A recent review and analysis of existing models of food choice integrates key elements into a single framework (Fig. 1 ) [ 32 ]. In this framework, key determinants of general food choice were identified and categorised, including Food– internal factor (sensory and perceptual features), Food– external factor (information, social environment, physical environment), Personal– state factor (biological features and physiological needs, psychological components, habits and experiences), Cognitive factor (knowledge and skills, attitude, liking and preference, anticipated consequences, and personal identity), and Sociocultural factors (culture, economic variables, political elements). According to this framework, any attempt to shift choice must consider these interrelated factors.

Conceptual model of food choice. The lines in the figure indicate the interactions between different factors [ 32 ]

Literature on perceived barriers and enablers of healthy eating

Most of the recent evidence on perceived barriers to and enablers of healthy eating focuses on particular sub-populations, such as young people with obesity, shift workers, or people with Type 2 diabetes [ 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ], and/or a particular type of diet, such as the Mediterranean Diet [ 38 – 39 ].

Studies examining more general populations tend to focus on younger people. A scoping review of barriers to and enablers of healthy eating for young adults in Western countries, for example, identified the following barriers: male apathy towards diet; unhealthy diet of friends and family; expected consumption of unhealthy foods in certain situations; relative low cost of unhealthy foods; lack of time to plan, shop, prepare, and cook healthy foods; lack of facilities to prepare, cook and store healthy foods; widespread presence of unhealthy foods; lack of knowledge and skills to plan, shop, prepare, and cook healthy foods; and lack of motivation to eat healthily (including risk-taking behaviour). Key enablers included: female interest in a healthy diet; healthy diet of friends and family; support/encouragement of friends and family to eat healthily; desire for improved health; desire for weight management; desire for improved self-esteem; desire for attractiveness to potential partners and others; possessing autonomous motivation to eat healthily and existence and use of self-regulatory skills [ 40 ]. A qualitative study of college students aged 18–24 at one university in Hawaii, U.S., of perceived barriers to and enablers of healthy eating found the largest barriers to be nutrition knowledge deficit, peer pressure, unsupportive institutional environment, and cost. The largest enablers were nutrition knowledge, parental influence, an institutional environment with consistent healthy offerings, and social media. It was noted that several of these factors served as barriers for some participants and enablers for others, such as nutrition knowledge, parental influence, and institutional environment [ 41 ]. Another qualitative study with college students at a U.S. college found that common barriers to healthy eating were time constraints, unhealthy snacking, convenience high-calorie food, stress, high prices of healthy food, and easy access to junk food. Conversely, enablers to healthy behaviour were improved food knowledge and education, meal planning, involvement in food preparation, and being physically active. Parental food behaviour and friends’ social pressure were considered to have both positive and negative influences on individual eating habits [ 42 ]. Much of this food choice literature identified the importance of social factors and social norms [ 43 – 44 ].