- Skip to content

State Resources

National Resources

Nursing Organizations

- MNWC Initiatives

Maryland Nursing Workforce Center

- NextGen NCLEX

Faculty Case Studies

The purpose of this project was to develop a repository of NextGen NCLEX case studies that can be accessed by all faculty members in Maryland.

Detailed information about how faculty members can use these case students is in this PowerPoint document .

The case studies are in a Word document and can be modified by faculty members as they determine.

NOTE: The answers to the questions found in the NextGen NCLEX Test Bank are only available in these faculty case studies. When students take the Test Bank questions, they will not get feedback on correct answers. Students and faculty should review test results and correct answers together.

The case studies are contained in 4 categories: Family (13 case studies), Fundamentals and Mental Health (14 case studies) and Medical Surgical (20 case studies). In addition the folder labeled minireviews contains PowerPoint sessions with combinations of case studies and standalone items.

Family ▾

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder - Pediatric

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Febrile Seizures

- Gestational Diabetes

- Intimate Partner Violence

- Neonatal Jaundice

- Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- Pediatric Hypoglycemia

- Pediatric Anaphylaxis

- Pediatric Diarrhea and Dehydration

- Pediatric Intussusception

- Pediatric Sickle Cell

- Postpartum Hemmorhage

- Poststreptococcal Glomerulonephritis Pediatric

- Preeclampsia

Fundamentals and Mental Health ▾

- Abdominal Surgery Postoperative Care

- Anorexia with Dehydration

- Catheter Related Urinary Tract Infection

- Deep Vein Thrombosis

- Dehydration Alzheimers

- Electroconvulsive Therapy

- Home Safety I

- Home Safety II

- Neuroleptic Maligant Syndrome

- Opioid Overdose

- Post Operative Atelectasis

- Post-traumatic Stress

- Pressure Injury

- Substance Use Withdrawal and Pain Control

- Suicide Prevention

- Tardive Dyskinesia

- Transfusion Reaction

- Urinary Tract infection

Medical Surgical ▾

- Acute Asthma

- Acute Respiratory Distress

- Breast Cancer

- Chest Pain (MI)

- Compartment Syndrome

- Deep Vein Thrombosis II

- End Stage Renal Disease and Dialysis

- Gastroesphageal Reflux

- Heart Failure

- HIV with Opportunistic Infection

- Ketoacidosis

- Liver Failure

- Prostate Cancer

- Spine Surgery

- Tension Pneumothorax

- Thyroid Storm

- Tuberculosis

Community Based ▾

Mini Review ▾

- Comprehensive Review

- Fundamentals

- Maternal Newborn Review

- Medical Surgical Nursing

- Mental Health Review

- Mini Review Faculty Summaries

- Mini Review Training for Website

- Mini Reviews Student Worksheets

- Pediatric Review

- OJIN Homepage

- Table of Contents

- Volume 23 - 2018

- Number 2: May 2018

- Evidence Psychiatric Mental Health Interventions

Evidence for Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Interventions: An Update (2011 through 2015)

Dr. Bekhet is an Associate Professor at Marquette University College of Nursing in Milwaukee, WI. She received aBSN and MSN from Alexandria University in Alexandria, Egypt. She received a PhD from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, OH. Her clinical experience in psychiatric nursing is with persons having schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and depressive disorders. She has taught psychiatric mental health nursing to undergraduate and direct entry students. She has also advised PhD students. Dr. Bekhet’s program of research focuses on the effects of positive cognitions and resourcefulness in overcoming adversity in vulnerable populations. Her research has been funded by Sigma Theta Tau International; American Psychiatric Nursing Foundation; International Society of Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses; and Marquette University. She is a past recipient of a Midwest Nursing Research Society Mentorship Grant Award, and has received the Award for Excellence from the CWRU Nursing Alumni Association in 2011 and the Way-Klinger Young Scholar Award from Marquette University in 2012. More recently, she was awarded the 2014 research award from the International Society of Psychiatric Mental Health Nurses. Dr. Bekhet has published numerous articles and presented numerous papers and posters at regional, national, and international conferences.

Dr. Zauszniewski is the Kate Hanna Harvey Professor in Community Health Nursing, and Director of the PhD in Nursing Program at the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), Cleveland, OH. She received a PhD and MSN from CWRU, Cleveland, OH; a MA in Counseling and Human Services from John Carroll University, Cleveland, OH; a BA in psychology from Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH; and a diploma in nursing from St. Alexis Hospital School of Nursing, Cleveland, OH. She has practiced nursing for 42 years, including 33 years in the field of psychiatric-mental health nursing; she has experience as a staff nurse, clinical preceptor, head nurse, supervisor, patient care coordinator, nurse educator, and nurse researcher, and is board certified by the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). Her program of research focuses on the identification of factors and strategies to prevent depression and to preserve healthy functioning across the lifespan. She is best known for her research examining the development and testing of nursing interventions to teach resourcefulness skills to family caregivers. She has received research funding from the National Institutes of Nursing Research and Aging; the National Institutes of Health; Sigma Theta Tau International; the American Nurses Foundation; Midwest Nursing Research Society; and the State of Ohio Board of Regents.

Denise Matel-Anderson is a doctoral student at Marquette University College of Nursing in Milwaukee, WI. She holds an Advanced Practice Nurse Prescriber license, and is currently working on a PhD in nursing with a focus on mental health. She has three publications in mental health nursing journals. Ms. Matel-Anderson currently lectures at Carroll University, Waukesha, WI, in the undergraduate mental health nursing theory course, and serves as a nurse practitioner on the medical team at an acute mental health facility.

Jane Suresky is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing of Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, OH. She has received DNP and MSN degrees from CWRU, and a BSN degree from Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH. Her clinical experience in psychiatric nursing covers the areas of psychobiological research, adolescent dual diagnosis, and mood disorders. She has taught psychiatric mental health nursing to undergraduate and graduate students. In addition, she has been involved in nursing research that focuses on the stress of the female family members of the severely mentally ill.

Mallory Stonehouse recently graduated with a Master of Science in Nursing degree from Marquette University in Milwaukee, WI, where she completed the adult-older adult, primary care, nurse practitioner program. She is a registered nurse at Froedtert Community Memorial Hospital in Wisconsin, where she works on the Behavioral Health Unit. Ms. Stonehouse holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology.

- Figures/Tables

This state-of-the-evidence review summarizes characteristics of intervention studies published from January 2011 through December 2015, in five psychiatric nursing journals. Of the 115 intervention studies, 23 tested interventions for mental health staff, while 92 focused on interventions to promote the well-being of clients. Analysis of published intervention studies revealed 92 intervention studies from 2011 through 2015, compared with 71 from 2006 through 2010, and 77 from 2000 through 2005. This systematic review identified a somewhat lower number of studies from outside the United States; a slightly greater focus on studies of mental health professionals compared with clients; and a continued trend for testing interventions capturing more than one dimension. Though substantial progress has been made through these years, room to grow remains. In this article, the authors discuss the background and significance of tracking the progress of intervention research disseminated within the specialty journals, present the study methods used , share their findings , describe the intervention domains and nature of the studies , discuss their findings , consider the implications of these studies , and conclude that continued track of psychiatric and mental health nursing intervention research is essential.

Key Words: best practices, evidence-based practice, psychiatric nursing journals, psychiatric nursing research, published research, research dissemination, research utilization, systematic review, tradition, intervention research

Implementation science is concerned with the translation of research into practice... The past five years have seen a rapidly growing interest in the field of implementation science ( Sorensen & Kosten, 2011 ). Implementation science is concerned with the translation of research into practice; it involves the examination of the challenges and the opportunities for successful, evidence-based changes in practice ( Nilsen, 2015 ). Translating research into practice depends heavily on the dissemination of findings from intervention research to those most likely to use those findings in clinical or community settings. In contrast to implementation, dissemination involves the spread of information about an intervention, for example, through publication of the intervention in professional journals. Dissemination strategies that are actively targeted toward spreading evidence-based findings concerning an intervention may prompt future implementation in clinical practice ( Proctor et al., 2009 ).

Translating research into practice depends heavily on the dissemination of findings from intervention research... Important for psychiatric and mental health nurses, it is critical that implementation of evidence-based findings occurs across multiple settings (i.e., beyond specialty mental healthcare units) to medical settings, such as primary care areas in which mental health services are provided, and to non-specialized settings, such as criminal justice and school systems and community social service agencies, where mental healthcare is delivered (Proctor et al., 2009). However, before implementation can happen, dissemination of findings from well-designed intervention studies that can inform psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is needed.

One of the best mediums for disseminating evidence-based findings in psychiatric and mental health nursing is the professional nursing journals that are most available to practicing psychiatric and mental health nurses. Nursing journals that are specifically designed a specialty are more likely to be read by persons in the given specialty area than are other nursing research journals. Nurses in practice settings, including those at an advanced practice level, may not have access to scientific research journals or may choose not to read them if the research does not appear meaningful for their practice. The goal of this review was to describe the findings from intervention studies disseminated through publication in one of the five psychiatric and mental health nursing specialty journals published from 2011 through 2015.

Background and Significance

Through the years, more psychiatric and mental health nurse researchers have been targeting specialty journals for disseminating findings from intervention research. For example, in previous reviews of intervention studies published in the five major psychiatric and mental health specialty journals, there was a higher percentage of quantitative intervention studies conducted from 2006 through 2010 (84%) than in a similar review conducted from 2000-2005 (64%) ( Zauszniewski, Suresky, Bekhet, & Kidd, 2007 ; Zauszniewski, Bekhet, & Haberlein, 2012 ), indicating increased use of more rigorous, statistical analytic methods in published intervention research over time ( Zauszniewski et al., 2007 ; Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ).

Tracking the progress of intervention research disseminated within the specialty journals in psychiatric and mental health nursing is important for two reasons. First, it provides data to show improvements in dissemination efforts of psychiatric and mental health nurse researchers. Second, it calls attention to the importance for continued dissemination of intervention research to practicing psychiatric and mental health nurses who are in the best positions to implement the findings in practice. Therefore, the purpose of this review of the same, five, peer-reviewed psychiatric and mental health nursing journals, covering 2011 through 2015, was to determine the number and types of intervention studies within the specified review period. For consistency, the same criteria for selecting the intervention studies that were described in the previous review ( Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ) were applied: A study was determined to be an intervention study if nursing strategies, procedures, or practices were examined for effectiveness in enhancing or promoting health or preventing disability or dysfunction ( Kane, 2015 ).

Five peer-reviewed nursing journals, regarded as the most frequently read in the mental health nursing profession, were analyzed for the years 2011 through 2015. The journals included in the analysis were Archives of Psychiatric Nursing ; Issues in Mental Health Nursing ; Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Associatio n; Journal of Psychosocial and Mental Health Services; and Perspectives in Psychiatric Care .

Journals were reviewed for the type of intervention study (qualitative or quantitative); the study domain (biological, psychological, or social); and the number of intervention studies found within the journals. After review, the agreed upon intervention studies were extracted and individually analyzed by the co-authors.

There were 832 databased articles published from January 2011 through December 2015. However, only 115 (14%) evaluated or tested psychiatric nursing interventions. Of these 115 intervention studies, 14 tested interventions with nursing students, nine involved nurses and mental health professionals, while 92 focused on interventions to promote mental health in clients of care.

This section describes the findings from the 115 intervention studies included in the review. The 23 studies that included nursing students, nurses, and mental health professional, and the 92 that involved recipients of mental health services or care are presented in this section. First, the research settings in which the 115 studies were conducted, and descriptions of the targeted populations are described. Next, the 23 studies’ designs, purposes, and findings are discussed in detail. Third, the 92 studies that involved recipients of mental health services or care are presented using the categories of the bio-psycho-social framework. Finally, the type of data (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed) are discussed and presented in the table.

Research Settings Sixty-six of the 115 intervention studies were completed in the United States. Five studies each were done in Australia and United Kingdom. Four each were completed in Korea, China, and Turkey; three each in Norway, Canada, and Iran; and two each in Taiwan, Mexico, Sweden, France, and Netherlands. One study each was conducted in Jordan, Europe, Iceland, Pacific Islands, Thailand, Spain, Greece, and Singapore

Targeted Populations Fourteen of the 115 intervention studies involved interventions with nursing students, while nine studies focused on nurses and mental health professionals. Ninety-two of the studies examined the effect of the intervention on the client. Examples of the studies describing each of these groups are described below.

Fourteen of the 23 nursing intervention studies involved undergraduate nursing students. Nursing students . Fourteen of the 23 nursing intervention studies involved undergraduate nursing students. One study was conducted in Australia regarding consumer participation ( Happell, Moxham, & Plantain-Phung, 2011 ). In this study, researchers investigated whether education programs introducing nursing students to mental health nursing lead to more favorable attitudes towards consumer participation in the mental health setting after completing the mental health component of the nursing program. Study participants were in the first semester of the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program. The study used a within-subject design using two points (pre-and post-educational program implementation). Results indicated that students demonstrated positive attitudes toward consumer participation even before completing the mental health component. Only marginal and non-significant changes were noted at the post-test stage. The authors concluded that the findings were not surprising given the positive scores recorded at baseline (ceiling effect) ( Happell et al., 2011 ). Another study investigated the effect of pedagogy of curriculum infusion on nursing students’ well-being and the improvement of quality of patients’ care ( Riley & Yearwood, 2012 ).

Pedagogy of curriculum infusion involves instilling the university values and mission with a focus on educating the whole person, and encouraging faculty to translate the core mission of the university into practice in the classroom. this can be accomplished through a variety of courses that provide students with opportunities for contemplation, reflective engagement, and also action through volunteerism, service, and study abroad. The ultimate goal of the study was to encourage critical thinking through reflective exercises and group discussion. Results indicated that students who have experienced the curriculum infusion showed an ability to be self-advocates when discussing their work challenges. Also, they were able to identify specific nursing actions for patient safety; to recognize the patient as a partner in care; and to demonstrate respect for patients' uniqueness, values, and desires as evidenced by case analysis and personal reflections ( Riley & Yearwood, 2012 ).

Three intervention studies explored simulation to see its impact on improving the learning experiences of the nursing students. Three intervention studies explored simulation to see its impact on improving the learning experiences of the nursing students ( Kameg, Englert, Howard, & Perozzi, 2013 ; Kidd, Knisley & Morgan, 2012 ; Masters, Kane, & Pike, 2014 ). Different simulations were used in the three studies; all of them were deemed effective. For example, the results of the study conducted by Kidd and colleagues indicated that undergraduate, mental health nursing students perceived that Second Life® virtual simulation was moderately effective as an educational strategy and slightly difficult as a technical program ( Kidd et al., 2012 ). Also, second degree and traditional BSN students found that a tabletop simulation, which was developed as a patient safety activity and involved checking-in a patient admitted to a psychiatric care unit, was a good learning experience and helpful to prepare students for situations they may experience in the workplace ( Masters et al., 2014 ). The third study used a high-fidelity, patient simulation (HFPS) to assess senior level nursing student knowledge and retention of knowledge utilizing three parallel, 30-item Elsevier Health Education Systems, Inc. (HESITM) Custom Exams. Although students’ knowledge did not improve following the HFPS experiences, the findings provided evidence that HFPS may improve knowledge in students who are at risk (defined as those earning less than 850 on HESI exam). Students reported that they viewed this simulation as a positive learning experience ( Kameg et al., 2013 ).

An additional intervention study used a quasi-experimental design to explore perceptions of student nurses toward nurses who are chemically dependent, using a two-group, pretest–posttest design (prior to formal education and after receiving substance abuse education). Results indicated that the student nurses in this study had positive perceptions about nurses who are chemically dependent before the intervention; and the education program appeared to reinforce their existing attitudes. ( Boulton & Nosek, 2014 ).

Mitchell et al. ( 2013 ) investigated the impact of an addiction training program for nurses consisting of Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), and embedded within an undergraduate nursing curriculum, on students’ abilities to apply an evidence-based screening and brief intervention approach for risky alcohol and drug use in their nursing practice. Results indicated that the SBIRT program was effective in changing the undergraduate nursing students’ self-perceptions of their knowledge, skills, and effectiveness in screening and intervening for hazardous alcohol and drug use. Furthermore, this positive perception was maintained at 30-day follow-up ( Mitchell et al., 2013 ).

Luebbert and Popkess ( 2015 ) investigated the impact of an innovative, active-learning strategy using simulated, standardized patients on suicide assessment skills in a sample of 34 junior and senior baccalaureate nursing students. Additionally, Schwindt, McNelis, and Sharp ( 2014 ) evaluated a theory-based educational program to motivate nursing students to intervene with persons having serious mental illness. Other intervention studies among nursing students focused on improving students' interpersonal relationships; communication competence; empathetic skills; and confidence in performing mental health nursing skills among nursing students ( Choi, Song, & Oh, 2015 ; Choi & Won, 2013 ; Fiedler, Breitenstein, & Delaney 2012 ; Ozcan, Bilgin, & Eracar, 2011 ; Stiberg, Holand, Ostad, & Lorem, 2012 ).

Nursing staff and mental health professionals . Interventions among the nursing staff and mental health professionals accounted for nine of the nursing intervention studies. The majority of these studies were nursing interventions to educate the nursing staff. Educational interventions included: training videos ( Irvine et al., 2012 ); a continuing education course on suicide awareness ( Tsai, Lin, Chang, Yu,& Chou, 2011 ); an education program using simulation ( Usher et al., 2014 ; Wynn, 2011 ); an educational workshop ( White, Hemingway, & Stephenson, 2014 ); training on family-centered care ( Wong, 2014 ); and the impact of the completion of a 26-week trial on nursing staff’s experience for working as a cardio-metabolic health nurse ( Happell et al., 2014 ).

Terry and Cutter ( 2013 ) used a mixed methods pilot study to evaluate the effect of education on confidence in assessing and addressing physical health needs following attendance at a module titled “Physical Health Issues in Adult Mental Health Practice.” The majority of the participants had studied at the university during the previous five years, at either the diploma or the degree level. Results showed improvement in confidence scores for all study participants following the module; participants were able to identify new knowledge and perspectives for practice change.

Results indicated that care zoning increased the nursing team’s capacity to share information and to communicate patients’ clinical needs... Finally, the study conducted by Taylor and colleagues ( 2011 ) used a pragmatic approach to increase understanding of the clinical-risks needs in acute in-patient unit settings. Each patient was classified according to three zoning levels using a traffic light system: red (high level of risk), amber (medium/moderate level of risk), and green (low level of risk). The level of risk was based on multiple factors including clinical judgment and team discussion ( Taylor et al., 2011 ). Results indicated that care zoning increased the nursing team’s capacity to share information and to communicate patients’ clinical needs, as well as to enhance their abilities to address complex clinical presentation and to seek support when needed.

Intervention Domains

Ninety-two of the studies examined the effect of an intervention for the client. In the following section, we will describe the intervention domains of these 92 articles and provided examples. Additional detail is included in the Table .

Interventions in the Biological Domain Eight interventions were in the biological domain. Study interventions included yoga, dancing, diet, medication, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), exercise, walking, and educational intervention on metabolic syndrome. Four interventions used various kinds of exercises, including walking ( Beebe, Smith, Davis, Roman, & Burke, 2012 ); dancing ( Emory, Silva, Christopher, Edwards, & Wahl, 2011 ); yoga ( Kinser, Bourguigion, Whaley, Hauenstein, & Taylor, 2013 ); and group exercise program ( Stanton, Donohue, Garnon, & Happell, 2015 ). Diet was also used as an intervention. For example, Lindseth, Helland, and Caspers ( 2015 ) used dietary intake of a high or low tryptophan diet as an intervention. Results indicated improvement in patients’ mood, depression, and anxiety for those consuming a high tryptophan diet as compared to those who consumed a low tryptophan diet ( Lindseth et al. 2015 ). A third category within the biological domain was the use of medications as an intervention. One study tested the use of different psychotropic medications for patients diagnosed with schizophrenia ( Zhou et al., 2014 ). A second used ECT as a treatment modality and measured scores on the Montgomery Asberg (MA) Depression Rating Scale before and after the course of treatment ( Pulia, Vaidya, Jayaram, Hayat, & Reti, 2013 ). A final category was an educational program on metabolic syndrome provided to mental health counselors who performed intake assessments on patients newly admitted to two outpatient mental health facilities. ( Arms, Bostic, & Cunningham, 2014 ). Prior to the intervention, neither facility screened for metabolic syndrome at intake or referred patients with a body mass index (BMI) >25 for medical evaluation. Following the intervention, 53 of 132 patients had a documented BMI >25, and 47 of 53 patients were referred to a primary care provider for evaluation. These findings suggested that screening for metabolic syndrome and associated illnesses will increase the rate of detection of chronic conditions ( Arms et al., 2014 ).

Interventions in the Psychological Domain ...the psychological domain had the largest number of intervention studies. Compared to the other domains, the psychological domain had the largest number of intervention studies. Twenty-four of the 92 total intervention studies extracted were in the psychological domain. The intervention studies in the psychological domain included emotion, behavior, and cognition (e.g., counseling) in addition to studies that focused on behavior therapy and psychoeducational programs. Examples of psychological domains studies included: counseling regarding tobacco cessation treatment ( Battaglia, Benson, Cook, & Prochazka, 2013 ); counseling regarding sexual assault ( Lawson, Munoz-Rojas, Gutman, & Siman, 2012 ); resourcefulness training intervention for relocated older adults ( Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Matel-Anderson, 2012 ); and resilience training and cognitive therapy in women with symptoms of depression aged 18-22 years of age ( Zamirinejad, Hojjat, Golzari, Borjali, & Akaberi, 2014 ) Please see the Table for further details.

One study utilizing an intervention from the psychological domain examined a brief, six- session, cognitive-behavioral intervention among patients with alcohol dependence and depression. The researchers used a quasi-experimental design with a control group and pretest, posttest, and follow-up assessments. Results indicated that the mean depression scores decreased significantly in both the experimental (n = 33) and control groups (n = 27) at the one-month follow-up (Week 7). However, only the experimental group showed significant differences in their mean depression scores between pre- and posttest. At Week 7, the experimental group showed significantly lower mean depression scores than the control group ( Thapinta, Skulphan, & Kittrattanapaiboon, 2014 ).

Interventions in the Social Domain The social domain considers the patients’ environment and its impact on patients’ adjustment and responses to stress. Nine studies involved use of the social domain in their interventions. The social domain considers the patients’ environment and its impact on patients’ adjustment and responses to stress. Interventions in this domain included family, friends, and social support, as well as community interactions ( Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ). One example of an intervention in the social domain involved studying the long-term impact of safe shelter and justice services on abused women’s ability to function after receiving services ( Koci, 2014 ). Another example of an intervention study in the social domain was a pilot, randomized, controlled trial study by Simpson, Quigley, Henry, and Hall ( 2014 ). In this study, the researchers evaluated the selection, training, and support of a group of peer workers recruited to provide support to service users discharged from acute psychiatric unites in London, comparing peer support with usual care ( Simpson et al., 2014 ) (see Table ). A third example in the social domain was designed to help participants successfully transfer from hospitals to the community by enhancing staff participation, creating/maintaining supportive ward milieus, and supporting managers throughout the implementation process ( Forchuk et al., 2012 ).

The study conducted by Horgan, McCarthy, and Sweeny ( 2013 ) was another example of research in the social domain. This study included designing a website for people ages 18-24 who were experiencing depressive symptoms. The website provided a forum to allow participants to offer peer support to each other; it also provided information on depression and links to other supports ( Horgan et al., 2013 ).

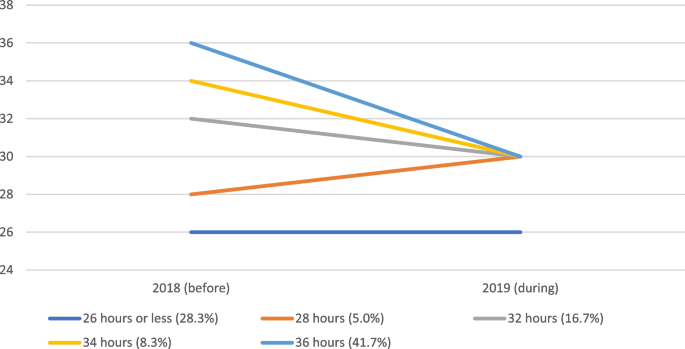

Combinations of the Domains Many studies used more than one domain as interventions. Many studies used more than one domain as interventions (see Figure ). Almost half (49%) of the 92 reviewed studies (n = 45) tested an intervention that included two domains. Thirty studies were psychosocial, twelve were biopsychological, and three were biosocial. In addition, six studies (7%) tested intervention with all three domains (biopsychosocial). In the following section, one study from each combination will be described. Again, additional information is provided in the Table .

Figure. Psychiatric Nursing Interventions: Examples of Domains and Their Total Numbers

Iskhandar Shah and colleagues ( 2015 ) studied and tested an intervention from the biopsychological domain using a single-group, pretest–posttest, quasi-experimental research design. Their intervention program included three daily, one-hour sessions incorporating psychoeducation and virtual-reality-based relaxation practice in a convenience sample of twenty-two people with mental disorders. Results indicated that those who completed the program had significantly lowered subjective stress, depression, and anxiety, along with increased skin temperature, perceived relaxation, and knowledge ( Iskhandar Shah et al., 2015 ).

Pedersen, Nordaunet, Martinsen, Berget, and Braastad ( 2011 ) studied an intervention from the biosocial domain. Their intervention program tested the impact of a 12-week, farm-animal-assisted intervention consisting of work and contact with dairy cattle, on levels of anxiety and depression in a sample of fourteen adults diagnosed with clinical depression. The twice-a-week program involved video recording each participant twice during the intervention. Participants were given the choice of either choosing their work tasks with animals (e.g., milking, feeding, hand feeding, moving animals) or the choice of spending their time in contact with farm animals (e.g., patting, stroking, and other non-work-related physical contact). Results indicated that levels of anxiety and depression decreased, and self-efficacy increased during the intervention. Interaction with farm animals (social) via work tasks showed a greater potential for improved mental health than merely animal contact, but only when progress in working skills (biological aspect) was achieved, indicating the role of coping experiences for a successful intervention. ( Pedersen et al., 2011 ).

The NP often accompanied the participant to medical and mental health appointments... Chandler, Roberts, and Chiodo ( 2015 ) conducted a study in the psychosocial domain that examined the feasibility and potential efficacy of implementing a four-week, empower-resilience intervention (ERI) to build resilience capacity with young adults who have identified adverse childhood experiences. The intervention included using mindfulness-based stress reduction (psychological domain) and social support with guided peer and facilitator interaction (social domain). The study randomly assigned a purposive sample of female undergraduate students between the ages of 18 and 24 years of age into two groups: intervention (n = 17) and control (n = 11), and used a pretest–posttest design to compare symptoms, health behaviors, and resilience before and after the intervention program. Results indicated that subjects in the intervention group reported greater building of strengths, reframing resilience, and creating support connections as compared with the control group ( Chandler et al., 2015 ).

Interventions in the biopsychosocial domain include all three components (biological, psychological, and social). There were six studies that included all three domains in their interventions. Hanrahan, Solomon, and Hurford ( 2014 ) used a randomized controlled design to deliver a transitional care model (TCM) intervention to patients with serious mental illness who were transferring from hospital care to home. The intervention group (n = 20) received the TCM intervention delivered by a psychiatric nurse practitioner (NP) for 90 days post hospitalization and the control group (n = 20) received the usual care. The intervention by the nurse practitioner included helping the patients adapt to the home by focusing on managing problem behaviors and physical problems, managing risk factors to prevent further cognitive or emotional decline, promoting adherence to therapies, and integrating physical and mental care approaches. The NP often accompanied the participant to medical and mental health appointments to facilitate communication, translate information to specialty providers, and advocate for the participant ( Hanrahan et al., 2014 ).

Table. Research Classifications by Domains, Design, and Type of Data Used

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Beebe et al. ( ) | Walking program | Self-efficacy for exercise was significantly higher in experimental participants than in controls after intervention. | Random assignment, researchers blinded, pre-/ posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Emory et al. ( ) | Line dancing program | The fall rate post intervention was 2.8% compared with 3.2% before intervention. | Pretest-posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Kinser, Bourguignon, Taylor, & Steeves ( ) | 8-week yoga intervention | Yoga served as a self-care technique for the stress and ruminative aspects of depression. Yoga facilitated connectedness and helped in sharing experiences in a safe environment. | Qualitative data through daily logs in which participants documented their feelings before and after daily home yoga practice. | Qualitative | Biological |

| Stanton et al. ( ) | Evaluate satisfaction with inpatient group activities designed to assist with recovery, including cognitive behavioral therapy, creative expression, relaxation, reflection/ discussion, and exercise. | More inpatients (50%) rated exercise as “excellent” compared with all other activities. Nonattendance rates were lowest for cognitive behavioral therapy (6.3%), highest for the relaxation group (18.8%), and for the group exercise program (12.5%). | Site evaluation upon discharge; evaluation survey was completed anonymously. | Quantitative | Biological |

| Lindseth et al. ( ) | Dietary intake of high or low tryptophan diet. | Improvement in patients’ mood, depression, and anxiety for those consuming a high tryptophan diet as compared to those who consumed a low Tryptophan. | Within-subjects crossover-designed study, random assignment to control /experimental | Quantitative | Biological |

| Zhou et al. ( ) | Examine the predictive value of time-based prospective memory (TBPM) and other cognitive components for remission of positive symptoms in first episode of schizophrenia. | Higher scores, reflecting better TBPM, at baseline were more likely to achieve remission after 8 weeks of optimized antipsychotic treatment. | Random assignment, pretest-posttest | Quantitative | Biological |

| Pulia et al. ( ) | ECT technique. Two changes were introduced: (a) switching the anesthetic agent from propofol to methohexital, and (b) using a more aggressive ECT charge dosing regimen for right unilateral (RUL) electrode placement. | Compared with patients receiving ECT with RUL placement prior to the changes, patients who received RUL ECT after the changes had a significantly shorter inpatient Length of stay (27.4 versus 18 days, p = 0.028). | A retrospective analysis was performed on two inpatient groups treated on Mood Disorders Unit. | Quantitative | Biological |

| Arms et al. ( ) | Education session about metabolic syndrome for clinicians. | No difference in educational pre-posttest scores. Clinicians increased referral to Primary Care Provider for BMI >25. | Pretest/posttest, chart audit | Quantitative | Biological |

| Battaglia et al. ( ) | Counseling regarding tobacco cessation treatment designed to increase patient engagement while hospitalized. | The intervention had minimal impacts on internalized stigma and personal recovery. Peer support demonstrated positive effects on internalized stigma and personal recovery. | Pilot study, single group, unblinded intervention trial | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Lawson et al. ( ) | “Men's Program”- rape prevention intervention. | Promising change in attitudes about rape beliefs and bystander behaviors in Hispanic males exposed to the educational intervention. | Exploratory study, mixed methods design, pre- and post-test, focus group transcription thematic coding | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Matel-Anderson ( ) | Resourcefulness training (RT) for relocated older adults assessing necessity, acceptability, feasibility, safety and effectiveness of RT. | 76.3% of the older adults scoring below 120, indicating a strong need for RT. Participants indicated acceptability, feasibility, safety, and effectiveness with recommendations for intervention improvement. | Pilot study, random assignment, convenience sample | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychological |

| Zamirinejad, Hojjat, Golzari, Borjali, & Akaberi ( ) | Resilience training and cognitive therapy for young women with depression | The resilience training group and cognitive therapy group showed a signiï¬cant decrease in the average depression score from pretest to posttest and from pretest to follow-up. There was no signiï¬cant difference between effectiveness of resilience training and cognitive therapy on depression but there was a signiï¬cant difference between these two treatment groups and the control group. | Three-group design with control, pretest- posttest | Quantitative | Psychological |

| Thapinta, Skulphan, & Kittrattanapaiboon ( ) | Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy intervention to reduce depression among alcohol-dependent individuals | The mean depression scores decreased signiï¬cantly in both the experimental and control groups at the one-month follow-up. However, only the experimental group showed signiï¬cant differences in their mean depression scores between pre-and posttest. At Week 7, the experimental group showed signiï¬cantly lower mean depression scores than the control group. | Quasi-experimental, control group, pretest/ posttest design | Quantitative | Psychological |

| Koci et al. ( ) | shelter and justice services for abused women | At 4 months following a shelter stay or justice services, improvement in all mental health measures; however, improvement was the lowest for PTSD. minimum further improvement at 12 months. | Prospective study | Quantitative | Social |

| Simpson et al. ( ) | peer support workers for inpatient aftercare | Participants indicated that the training was valuable, challenging, yet positive experience that provided them with a good preparation for the role. | Pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT), focus groups | Quantitative and Qualitative | Social |

| Forchuk et al. ( ) | Transitional Relational Model (TRM) was used to help mental health clients transitioning from a psychiatric hospital setting to the community. Strategies included enhancing staff participation, creating/ maintaining supportive ward milieus. | Group C implemented the TRM model significantly quicker than the other groups. | Randomized controlled trial; compared three groups of hospital wards; Group A wards had already adopted the TRM, Group B wards implemented the TRM in Year 1, and Group C wards implemented the TRM in Year 2. | Quantitative | Social |

| Horgan, McCarthy, & Sweeney ( ) | online peer support for young adults experiencing depressive symptoms | No statistical significance difference pre- and post-test. The forum posts revealed that the participants' main difficulties were loneliness and perceived lack of socialization skills. The website provided a place for emotional support. | Mixed method, involving quantitative descriptive, pre- and post-test and qualitative descriptive designs | Quantitative and Qualitative | Social |

| Iskhandar Shah et al. ( ) | Virtual reality (VR)-based stress management (VR DE-STRESS) program for people with mood disorders | Those who completed the program had significantly lowered stress, depression, anxiety. | Single-group, pretest–posttest, quasi-experimental research design and convenience sample | Quantitative and Qualitative | Bio-psychological |

| Pedersen et al. ( ) | Farm animal-assisted intervention consisting of work and contact with dairy cattle | Levels of anxiety and depression decreased, and self-efficacy increased during the intervention. | Pretest-posttest, video recording thematic coding | Quantitative and Qualitative | Bio-Social |

| Chandler et al ( ) | Empower resilience intervention (ERI) to build resilience | Subjects in the intervention group reported building strengths, reframing resilience, and creating support connections. | Purposive sampling, random assignment, intervention and control, pretest-posttest design | Quantitative and Qualitative | Psychosocial |

| Hanrahan et al. ( ) | Transitional care model (TCM) intervention to patients with serious mental illness transferring from hospital care to home | Emergency room use was lower for intervention group but not statistically significant. Continuity of care with primary care appointments were significantly higher for the intervention group. The intervention group's general health improved but was not statistically significant compared with controls. | Randomized controlled trial | Quantitative | Bio-psychosocial |

Discussion

Although substantial progress is being made to develop and test interventions for persons with psychiatric and mental health challenges and their families, there remains much work to be done. Nurse scientists and practitioners share a professional obligation to persons entrusted to their care, which includes providing the highest quality care grounded in solid empirical evidence ( Willis, Beeber, Mahoney, & Sharp, 2010 ). This review yields evidence for the continued dissemination of findings from intervention studies from 2011 through 2015. To perform the analysis reported here, we employed methods that were similar to those used for amassing information from the intervention studies in two previous reviews ( Zauszniewski et al., 2007 ; Zauszniewski et al., 2012 ) in order to facilitate comparisons over time.

... the continued publication of evidence from countries outside the United States remains important... During the review period (2011-2015), 57% of the published intervention studies took place in the United States (U.S.) while 43% were conducted outside the U.S. (i.e., internationally). These percentages compare with 72% and 54% of published U.S. intervention studies and 28% and 46% published international intervention studies in the 2000-2005 and 2006-2010 reviews, respectively. The somewhat lower percentages (28% and 46%) of international intervention studies within the current time frame (2011-2015) may indicate a need for more descriptive research to identify distinguishing characteristics of international populations and important phenomena that may be amenable to intervention prior to the systematic testing of interventions. However, the continued publication of evidence from countries outside the United States remains important for developing globally relevant interventions for psychiatric nursing practice.

...there have been dramatic increases through the years in the overall number of studies that have tested interventions that tap more than one domain. Of the 115 intervention studies from 2011 through 2015 found in the five journals, nurses, student nurses, nursing staff, or other mental health professionals were the intervention recipients in 23, representing 20% of the intervention studies. This percent is higher than the 14% reported in the previous review conducted from 2006 through 2010, indicating a slightly greater focus on testing interventions in mental health care professionals in recent years. Although the interventions tested in these populations are not focused directly on outcomes for clients with mental health issues, promoting or preserving the mental health of professional caregivers most certainly affects those for whom they provide care.

Analysis of published intervention studies in the 5-year interval from 2011 through 2015 revealed an increase in the number of studies of psychiatric patients or clients in the five selected journals. For this time frame, we found 92 intervention studies in comparison with 71 from 2006 through 2010 and 77 from 2000 through 2005, which reflect 5 and 6-year intervals respectively.

We also noted fewer intervention studies where all three domains were integrated within the intervention... Moreover, there have been dramatic increases through the years in the overall number of studies that have tested interventions that tap more than one domain. For example, 33% of intervention studies from 2011 through 2015 tested psychosocial interventions, compared to 17% in the previous review (2006-2010) and 12% in the one prior to that (2000-2005). In addition, 13% of the studies from 2011 through 2015 tested biopsychological interventions compared with 4% and 5% in the previous two reviews. However, there was a slightly lower percent of biosocial intervention studies, specifically 3% in comparison with 4% from 2000-2005 and 6% from 2006-2010. We also noted fewer intervention studies where all three domains were integrated within the intervention, specifically only 6% in comparison with 17% in the previous time frame (2006-2010). Yet, our review revealed a larger percent of biopsychosocial intervention studies than from the review conducted from 2000-2005 (1%). Despite the lower number of studies that integrated all three intervention domains, there was an overall trend toward testing interventions that were not restricted only to one domain, indicating increased attention toward more holistic interventions.

... the overall trend shows a lesser focus on testing interventions within a single domain over time... There were 41 intervention studies between 2011 and 2015 that focused solely on one domain. With the exception of the biological domain (9%), interventions within the psychological (26%) and social (10%) domains were fewer than in previous reviews. For example, there has been a clear downward trend in the percent of psychological intervention studies over time with 57% from 2000-2005 to 38% from 2006-2010 and 26% in this current review. Intervention studies within the social domain decreased from 17% in 2006-2010 to 10% in this review. Studies of interventions in the biological domain have fluctuated over time from 11% in 2000-2005 down to 1% from 2005-2010 and up to 9% in the review reported here. However, the overall trend shows a lesser focus on testing interventions within a single domain over time, pointing perhaps to a growing interest in determining effective interventions that are multifaceted and target multiple factors that affect a person’s health.

Implications: Research Needed

The mind and body do not function independently of each other; therefore, when considering the focus of nursing research, we need to target both systems. Nursing has as its foundation a holistic approach to patient care. At this point in our history as we build a knowledge base, a multifaceted approach is needed when planning nursing research. This study of nursing interventions in our research has explored the biological, psychological, and social domains. Studies in the biopsychosocial domain would benefit our knowledge base and improve the criteria for more accurate, evidence-based nursing interventions.

Medicine has increasingly focused on the mental health component of medical illnesses. Nursing research would be strengthened by focusing on the possibility of medical illness and its relationship to mental illness. This nursing research approach'‹ would support our holistic philosophy of care and increase our knowledge of the whole person. It would provide the best evidence-based approach to planning treatment. In addition, it would serve to increase the sphere of psychiatric nursing beyond the psychiatric unit in health care settings.

...an increase in multicultural studies is needed to further strengthen our evidenced based practice. Finally, an increase in multicultural studies is needed to further strengthen our evidenced based practice. The individual person is complex. Identified culture provides important information as to how patients view health and illness. This information is an important component when planning our evidenced based care and should not be isolated from the patient presentation.

Tracking the progress in intervention research relevant for psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is essential to identify evidence gaps. This current, systematic review of intervention studies published in the most accessible psychiatric and mental health nursing journals for practicing nurses, educators, and researchers in the United States has revealed a somewhat lower number of studies from outside the United States; a slightly greater focus on studies of nurses, nursing students, or other mental health professionals as compared with clients who receive their care or services; and a continued trend for testing interventions that captured more than one dimension. Tracking the progress in intervention research relevant for psychiatric and mental health nursing practice is essential to identify evidence gaps. Though substantial progress has been made through the years, there is still room to grow.

Abir K. Bekhet, PhD, RN, HSMI Email: [email protected]

Jaclene A. Zauszniewski, PhD, RN-BC, FAAN Email: [email protected]

Denise M. Matel-Anderson, APNP, RN Email: [email protected]

Jane Suresky, DNP, MSN Email: [email protected]

Mallory Stonehouse, MSN, RN Email: [email protected]

Arms, T., Bostic, T., & Cunningham, P. (2014). Educational intervention to increase detection of metabolic syndrome in patients at community mental health centers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 52 (9), 32-36. doi:10.3928/02793695-20140703-01

Battaglia, C., Benson, S.L., Cook, P.F., & Prochazka, A. (2013). Building a tobacco cessation telehealth care management for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association , 19 (2), 78-91. doi:10.1177/1078390313483314

Beebe, L.H., Smith, K., Davis, J., Roman, M., & Burke, R. (2012). Meet me at the crossroads: Clinical research engages practitioners, educators, students, and patients. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48 (2), 76-82. doi: 10.1111%2Fj.1744-6163.2011.00306.x

Bekhet, A.K., Zauszniewski, J.A., & Matel-Anderson, D.M. (2012). Resourcefulness training intervention: Assessing critical parameters from relocated older adults’ perspectives. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (7), 430-435. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.664802

Boulton, M.A., & Nosek, L. (2014). How do nursing students perceive substance abusing nurses? Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (1), 29-34. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.10.005

Chandler, G.E., Roberts, S.J., & Chiodo, L. (2015). Resilience intervention for young adults with adverse childhood experiences. The Journal of Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21 (6), 406-416. doi:10.1177/1078390315620609

Choi, Y., Song, E., & Oh, E. (2015). Effects of teaching communication skills using a video clip on a smart phone on communication competence and emotional intelligence in nursing students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (2), 90-95. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.003

Choi, Y-J., & Won, M-R. (2013). A pilot study on effects of a group program using recreational therapy to improve interpersonal relationships for undergraduate nursing students. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (1), 54-55. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.08.002

Emory, S.L., Silva, S.G., Edwards, P.B., & Wahl, L.E. (2011). Stepping to stability and fall prevention in adult psychiatric patients. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 49 (12), 30-36 doi:10.3928/02793695-20111102-01

Fiedler, R.A., Breitenstein, S., & Delaney, K. (2012). An assessment of students’ confidence in performing psychiatric mental health nursing skills: The impact of the clinical practicum experience. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18 (4), 244-250. doi:10.1177/1078390312455218

Forchuk, C., Martin, M-L., Jensen, E., Ouseley, S., Sealy, P., Beal, G., … Sharkey, S. (2012). Integrating the transitional relationship model into clinical practice. Archives in Psychiatric Nursing, 26 (5), 374-381. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01956.x

Hanrahan, N.P., Solomon, P., & Hurford, M.O. (2014). A pilot randomized control trial: Testing a transitional care model for acute psychiatric conditions. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association , 20 (5), 315-327. doi:10.1177/1078390314552190

Happell, B., Hodgetts, D., Stanton, R., Millar, F., Phung, C.P., & Scott, D. (2014). Lessons learned from the trial of a cardiometabolic health nurse. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50 (4), 1-9. doi:10.1111/ppc.12091

Happell, B., Moxham, L., &Platania-Phung, C. (2011). The impact of mental health nursing education on undergraduate nursing students’ attitudes to consumer participation. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (2), 108-113. doi:10.3109/01612840.2010.531519

Horgan, A., McCarthy, G., & Sweeny, J. (2013). An evaluation of an online peer support forum for university students with depressive symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (2), 54-55. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.12.00

Irvine, A.B., Billow, M.B., Eberhage, M.G., Seeley, J.R., McMahon, E., & Bourgeois, M. (2012). Mental illness training for licensed staff in long-term care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (3), 181-194. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.639482

Iskhandar Shah, L.B., Torres, S., Kannusamy, P., Lee Chng, C.M., He, H-G., Klainin-Yobas, P. (2015). Efficacy of the virtual reality-based stress management program on stree-related variables in people with mood disorders: The feasibility of the study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (1), 6-13. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.09.003

Kameg, K.M., Englert, N.C., Howard, V.M., & Perozzi, K.J. (2013). Fusion of psychiatric and medical high-fidelity patient simulation scenarios: Effect on nursing student knowledge, retention of knowledge, and perception. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34 (12), 892-900. doi:10.3109/01612840.2013.854543

Kane, C. (2015). The 2014 Scope and Standards of Practice for psychiatric mental health nursing: Key Updates. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 20 (1), Manuscript 1. doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol20No01Man01

Kidd, L.I., Knisley, S.J. & Morgan, K.I. (2012). Effectiveness of a Second Life® simulation as a teaching strategy for undergraduate mental health nursing students. Journal of Psychosocial & Mental Health Services, 50 (7), 3-5. doi:10.3928/02793695-20120605-04

Kinser, P.A., Bourgugnon, C. Taylor, A.G., Steeves, R. (2013). "A feeling of connectedness": Perspectives on a gentle yoga interenvention for women with major depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 34 (6), 402-211. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.762959

Kinser, P.A., Bourguigion, C., Whaley, D., Hauenstein, E., & Taylor, A.G. (2013). Feasibility, acceptability, and effects of gentle Hatha yoga for women with major depression: Findings from a randomized controlled mixed-methods study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27 (3), 137-147. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.01.003

Koci, A.F., Cesario, S., Nava, A., Liu, F., Montalvo-Liendo, N., & Zahed, H. (2014). Women’s functioning following an intervention for partner violence: New knowledge for clinical practice from a 7-year study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35 (10), 745-755. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.901450

Lawson, S.L., Munoz-Rojas, D., & Siman, M.N. (2012). Changing attitudes and perceptions of Hispanic men ages 18-25 about rape and rape prevention. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 22 (12), 864-70. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.728279

Lindseth, G., Helland, B., & Caspers, J. (2015). The effects of dietary tryptophan on affective disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29 (3), 102-107. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.11.008

Luebbert, R., & Popkess, A. (2015). The influence of teaching method on performance of suicide assessment in baccalaureate nursing students. The Journal of American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 21 (2), 126-133. doi:10.1177/1078390315580096

Masters, J.C., Kane, M.G., & Pike, M.E. (2014). The suitcase simulation: An effective and inexpensive psychiatric nursing teaching activity. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 52 (8), 39-44. doi:10.3928/02793695-20140619-01

Mitchell, A.M., Puskar, K., Hagle, H., Gotham, H.J., Talcott, K.S., Terhorst, L., … Burns, H.K. (2013). Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment: Overview of and student satisfaction with an undergraduate addiction training program for nurses. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 51 (10), 29-37. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130628-01

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science : IS , 10 , 53. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

Ozcan, N.D., Bilgin, H., & Eracar, N. (2011). The use of expressive methods for developing empathetic skills. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (2), 131-136. doi:10.3109/01612840.2010.534575

Pedersen, I., Nordaunet, T., Martinsen, E.W., Berget, B., & Braastad, B.O. (2011). Farm animal-assisted intervention: Relationship between work and contact with farm animals and change in depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy among persons with clinical depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (8), 493-500. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.566982

Proctor, E.K., Landsverk, J., Aarons, G., Chambers, D., Glisson, C., & Mittman, B. (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 36 (1), 24-34 doi:10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4

Pulia, K., Vaidya, P., Jayaram, G., Hayat, M., & Reti, I.M. (2013). ECT treatment outcomes following performance improvement changes. Journal of Psychosocial and Mental Health Services, 51 (11), 20-25. doi:10.3928/02793695-20130628-02

Riley, J.B., & Yearwood, E.L. (2012). The effect of a pedagogy of curriculum infusion on nursing student well-being and intent to improve the quality of nursing care. Achieves in Psychiatric Nursing, 26 (5), 364-63. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2012.06.004

Schwindt, R.G., McNelis, A.M., & Sharp, D. (2014). Evaluation of a theory-based educational program to motivate nursing students to intervene with their seriously mentally ill clients who use tobacco. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (4), 277-283. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.04.003

Simpson, A., Quigley, J., Henry, S.J., & Hall, C. (2014). Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52 (1), 31-40. doi:10.3928/02793695-20131126-03

Sorensen, J. L., & Kosten, T. (2011). Developing the tools of implementation science in substance use disorders treatment: applications of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25 (2), 262-268. doi:10.1037/a0022765

Stanton, R., Donohue, T., Garnon, M., & Happell, B. (2015). Participation in and satisfaction with an exercise program for inpatient mental health consumers. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 52 (1), 62-67. doi:10.1111/ppc.12108

Stiberg, E., Holand, U., Olstad, R., & Lorem, G. (2012). Teaching care and cooperation with relatives: Video as a learning tool in mental health work . Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33 (8). doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.687804

Taylor. K., Guy, S., Stewart, L., Ayling, M., Miller, G., Anthony, A., … Thomas, M. (2011). Care zoning a pragmatic approach to enhance the understanding of clinical needs as it relates to clinical risks in acute in-patient unit settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32 (5), 318-326. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.559570

Terry, J. & Cutter, J. (2013). Does education improve mental health practitioners’ confidence in meeting the physical health needs of mental health service users? A mixed method pilot study. Issues in Mental Health , 34(4), 249-255. doi:10.3109/01612840.2012.740768

Thapinta, D., Skulphan, S., & Kittrattanapaiboon, P. (2014). Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for depression among patients with alcohol dependence in Thailand. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35( 9), 689-693. doi:10.3109/01612840.2014.917751

Tsai, W-P., Lin, L-Y., Chang, H-C., Yu, L-S., & Chou, M-C. (2011). The effects of the gatekeeper suicide-awareness program for nursing personnel. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 47 (3), 117-125. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2010.00278

Usher, K., Park, T., Trueman, S., Redman-MacLaren, M., Casella, E., & Woods, C. (2014). An educational program for mental health nurses and community health workers from Pacific Island countries: Results from a pilot study . Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35 (5), 337-343. doi:10.3109%2F01612840.2013.868963

White, J., Hemingway, S., & Stephenson, J. (2014). Training mental health nurses to assess the physical health needs of mental health service users: A pre- and post-test analysis. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50( 4), 243-250. doi:10.1111/ppc.12048

Willis, D.G., Beeber, L., Mahoney, J., & Sharp, D. (2010). Strategies for advancing psychiatric-mental health nursing science relevant to practice. Perspectives from the American Psychiatric Nurses Association research council co-chairs. Contemporary Nurse, 34 (2), 135-139

Wong, O.L. (2014). Contextual barriers to the successful implementation of family-centered practice in mental health care: A Hong Kong study. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28 (3), 197-199. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2014.02.001

Wynn, S.D. (2011). Improving the quality of care of veterans with diabetes. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 49 (2), 38-43. doi:10.3928/02793695-20110111-01

Zamirinejad, S., Hojjat, SK., Golzari, M., Borjali, A., &Akaberi, A. (2014). Effectiveness of resilience training versus cognitive therapy on reduction of depression in female Iranian college students. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36 (6), 480-488. doi:10.3109/01612840.2013.879628

Zauszniewski, J.A, Bekhet, A., &Haberlein, S. (2012). A decade of published evidence for psychiatric and mental health nursing interventions. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17 (3), doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol17No03HirshPsy01

Zauszniewski, J., Suresky M.J., Bekhet, A., & Kidd, L. (May 14, 2007). Moving from Tradition to Evidence: A Review of Psychiatric Nursing Intervention Studies . Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 12 (2) doi:10.3912/OJIN.Vol12No02HirshPsy01

Zhou, F-C., Xiang, Y-T., Wang, C-Y., Dickerson, F., Kryenbuhl, J., Ungari, G.S., … Chiu, H.F.K. (2014). Predictive value of prospective memory for remission in first-episode schizophrenia. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50 (2), 102-110. doi:10.1111/ppc.12027

May 31, 2018

DOI : 10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man04

https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol23No02Man04

Citation: Bekhet, A.K., Zauszniewski, J.A., Matel-Anderson, D.M., Suresky, M.J., Stonehouse, M., (May 31, 2018) "Evidence for Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing Interventions: An Update (2011 through 2015)" OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing Vol. 23, No. 2, Manuscript 4.

- Article May 31, 2018 Advancing Scholarship through Translational Research: The Role of PhD and DNP Prepared Nurses Deborah E. Trautman, PhD, RN, FAAN; Shannon Idzik, DNP, CRNP, FAANP, FAAN; Margaret Hammersla, PhD, CRNP-A; Robert Rosseter, MBA, MS

- Article May 31, 2018 Connecting Translational Nurse Scientists Across the Nation—The Nurse Scientist-Translational Research Interest Group Elizabeth Gross Cohn, RN, NP, PhD, FAAN; Donna Jo McCloskey, RN, PhD, FAAN; Christine Tassone Kovner, PhD, RN, FAAN; Rachel Schiffman, RN, PhD, FAAN; Pamela H. Mitchell, RN, PhD, FAAN

- Article May 31, 2018 Translation Research in Practice: An Introduction Marita G. Titler, PhD, RN, FAAN

- Subscribe to journal Subscribe

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Mental health in nursing

A student's perspective.

Halsted, Candis DNP-PMHNP, RN; Hart, Virginia T. DNP, RN, PMHNP-BC

At Radford University School of Nursing in Radford, Va., Candis Halsted recently earned her DNP and Virginia T. Hart is an assistant professor and interim psychiatric mental health NP program coordinator.

The authors have disclosed no financial relationships related to this article.

A stigma around mental health issues within healthcare and nursing itself has created a culture of perfectionism in the workplace, and nurses struggle to live up to the expectations while pushing aside their feelings, thoughts, and needs. Inspired by one author's personal experiences, this article explores mental health issues many nurses confront today.

Inspired by one author's personal experiences, this article explores mental health issues many nurses confront today.

I DECIDED TO RETURN to school in 2015 after practicing as a nurse in various settings for 7 years. I subscribe to the adage that knowledge is power. My drive for additional education and experience was based on my desire to achieve a higher status, assume more control over my practice, and to garner more respect from other healthcare professionals. As I immersed myself in my graduate studies, however, I found my desires, self-image, and professional viewpoint had changed.

I have always endeavored to be the best student, greatest employee, and most dependable teammate. Those efforts took on a feverish intensity during periods of transition—student to nurse, nurse to working mother, mother and nurse to professional student. Good was not good enough, and my drive to be the best and greatest was an integral part of my self-worth. Unfortunately, it led to anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and isolation that negatively impacted my education, practice, and personal life.

It was not until my clinical rotations as a psychiatric-mental health NP student that I came to realize the magnitude of the situation. There I was, taking courses on trauma-informed care and giving my patients tools for building self-efficacy, self-compassion, and coping skills while simultaneously ignoring my own needs.

Having left the workplace to focus on my online studies, I was isolated, lacking confidence, feeling overwhelmed, and overcompensating for some perceived shortcoming that I could not even define. I felt hopeless and defeated. I experienced bouts of anxiety and depression so intense I lost my sense of purpose. I considered dropping out of school many times, but I gave in to the expectations of others. I forced myself to continue pushing aside my own needs, persisting despite my growing depression and anxiety.

Looking back, I had so many chances to speak up and reach out for help. I could have spoken with nurse managers, coworkers, fellow students, and faculty a hundred different ways on so many occasions. Instead, I allowed the culture of silence and my own perfectionism to rule.

At my lowest point, I made the life-altering decision to reach out for help—first to my husband, then a therapist, a fellow student, and finally my school faculty. With their assistance, some serious self-reflection, and a lot of self-help reading, I am working to address my mental illness and establish a sense of well-being.

That is not to say that I have it all figured out. I still struggle many days to keep faith in my strengths and abilities. The things I have learned and witnessed, the obstacles I have encountered and overcome, whether academic, professional, or personal, have humbled me and restored my desire to return to the love, service, and justice at the core of my professional drive and practice. I am once again prioritizing my values and making sure my actions reflect them. Among those values is the desire to work toward the unification of our profession and to advocate for policy changes that support the mental health of all nurses. Inspired by my personal experiences, this article explores mental health issues many nurses confront today.

A pervasive problem

Although mental health and suicide among nurses have emerged as areas of professional concern in recent years, little research or literature exists regarding profession-specific risk factors, prevalence of mental illness, and suicide rates. With little to no concrete statistics to draw from, the true incidence of mental illness within the nursing profession is unknown. Furthermore, little has been done to bring these problems to the attention of the general public or to acquire the recognition and support of the professional community. 1-3

What can be found are decades of research stating that nursing is psychologically demanding and can contribute to poor mental health in a variety of ways, such as depression, anxiety, secondary trauma, compassion fatigue, and burnout. 1-7 The occupational hazards of nursing can also compromise work-life balance. Add to this various individual risk factors such as genetic predisposition or history of personal trauma, as well as the fact that academic standards for the profession favor those who are exacting and high-performing. It stands to reason that nurses are in jeopardy of significantly elevated levels of stress and maladaptive coping. 5,8 When ongoing, this can lead to impaired functioning. In the professional setting, impairment has been correlated with increased risk for errors, patient harm, and clinical ineffectiveness. 9

Mental illness can be defined as clinically significant impairment in social, conceptual, and practical functioning. 9,10 Although very common, mental illness is often untreated. 11 One in five adults will have some experience with mental illness each year, but less than half will receive treatment. 11

Nursing has a hidden culture of stigma and silence regarding mental illness, which serves to minimize and overshadow those experiencing clinically significant distress. 6,12 Competition, intimidation, and bullying among nurses are pervasive across practice and in academic settings. 13,14 These behaviors can breed psychologically hazardous and hostile environments. Fear of becoming a target may result in blame, shame, self-stigmatization, isolation, and suffering in any individual with potentially undesirable characteristics in such settings, regardless of his or her mental health status. Such abuses and fear can promote conformity and negatively impact disclosure and help-seeking behaviors in stressed, distressed, and impaired individuals. 1,2,5,13

The issue is exacerbated by a lack of respect and recognition for nursing that is still present within the healthcare culture at large. The traditional hierarchy holds physicians as experts, not nurses. Even advanced practice nurses are diminished, often referred to as “mid-level providers” and “physician extenders.” 15 These attitudes undermine the autonomy and dignity of nurses, especially when they collaborate with other healthcare disciplines. 14

In addition, while healthcare entities and societies champion the rights of the patient, the need to protect the basic human dignity and professional image of nurses is often overlooked. 14 Fundamental protections and rights for nurses are being compromised every day when we are expected to tolerate long hours, interrupted (or nonexistent) breaks, heavy patient caseloads, incivility, and even violence in the workplace. Nurse unions across the country are threatening walkouts and going on strike because of the failure of hospitals to address these issues. 16,17 The situation is not helped by the fact that guiding and governing bodies for nursing practice are numerous yet, in my opinion, self-segregated.

Systemic change

Although some organizations have created emotional wellness programs, a cohesive or public effort to address systemic problems is lacking. 1-3 Until employers, boards of nursing, and nursing organizations place the same importance on the well-being of nurses and risk mitigation, nurses may continue to suffer in silence. Within the currently disjointed system, we cannot hope to make substantive changes without offering our passion and expertise as well as identifying and supporting means for promoting self-care and wellness among the thousands of practicing nurses and preprofessionals experiencing distress or symptoms of mental illness.

Pressures and barriers to mental health and help-seeking extend to the academic setting. 4-5 For professional nurses returning to school, the pressure associated with practice and professional expectations may be exacerbated by their increased need to balance a variety of personal and/or family responsibilities, deadlines, financial obligations, leisure time, and peer competitiveness. Despite these contributory risk factors, I have seen few—if any—educational programs for health and helping disciplines, such as nursing, medicine, and social work, place value on assessing students' stress and distress. In commiserative discussions with others doing graduate work in nursing, social work, occupational therapy, and physical therapy, I have yet to meet anyone who felt the faculty took action to address the genuine difficulties many of them faced in balancing their lives. In short, students (myself included) feel devalued by the lack of respect, holistic consideration, and mentorship they encounter. Academic learning environments have a great need to support improvement of the emotional well-being and psychological resiliency of students and for improving the accessibility of support, counseling, and mental health resources. 4,5

I encourage you to take a long, hard look at yourself and those around you. If you are struggling, please reach out to someone you trust and let them know you are not okay. If you are not sure that what you are experiencing is normal or cause for concern, there are many websites that provide education and information on how to identify mental health problems, as well as hotline crisis intervention services and referrals to local counseling. These websites often have articles and tips on how to improve your mental health through physical, spiritual, and psychological self-care. (See Mental health resources .)

No mental health concern is too big or too small. If you are not well, talk to a friend, family member, professional, or help hotline. If you suspect a coworker, colleague, or student needs help, please reach out. Something as simple as asking if they are okay and giving them the space and time to express their feelings can make all the difference. As Edward Everett Hale once said, “I am only one, but still I am one. I cannot do everything, but still I can do something. And because I cannot do everything, I will not refuse to do the something that I can do.” 18 We owe it to ourselves, our profession, our patients, and their families to seek help and to offer help to our fellow nurses in need.

For anyone requiring immediate crisis intervention or assistance finding a local mental health provider, the following resources are available:

- Mental Health America: 1-866-400-6428 for referrals, 1-800-273-8255 for crisis

- National Alliance on Mental Illness HelpLine 1-800-950-6264

- National Suicide Prevention Helpline 1-800-273-8255

Crisis Text Line available 24 hours a day, text “HOME” to 741741

Mental health resources

- American Psychological Association

- www.apa.org

- American Psychiatric Nurses Association (APNA)

- www.apna.org

- MentalHealth.gov

- www.mentalhealth.gov

- National Alliance on Mental Illness

- www.nami.org

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org

- Crisis Text Line

- www.crisistextline.org

anxiety; compassion fatigue; depression; emotional wellness; mental health; nursing; suicide prevention

- + Favorites