- Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. Abstract

- Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). National Institutes of Health. http://www.nihpromis.org/ Accessed August 12, 2011.

- 3Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence-based systematic review on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:S1-S34.

- Bijkerk CJ, de Wit NJ, Muris JWM, Whorwell PJ, Knottnerus JA, Hoes AW. Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:B3154-B3160. Abstract

- Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459-1464. Abstract

- Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, et al. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765-771. Abstract

- Shah ED, Basseri RJ, Chong K, et al. Abnormal breath testing in IBS: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2441-2449. Abstract

- Frissora CL, Cash BD. Review article: the role of antibiotics vs. conventional pharmacotherapy in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1271-1281. Abstract

- Pimental M, Lembo A, Chey W, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32. Abstract

- Camilleri M, Chey WY, Mayer EA, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea, predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1733-1740. Abstract

- Nyhlin H, Bang C, Elsborg L, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tegaserod in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:119-126. Abstract

- Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome-results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341. Abstract

- Pimentel M, Park S, Mirocha J, et al. The effect of a nonabsorbed oral antibiotic (rifaximin) on the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:557-563. Abstract

- DuPont HL, Jiang ZD. Influence of rifaximin treatment on the susceptibility of intestinal gram-negative flora and enterococci. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:1009-1011. Abstract

- Yang J, Lee HR, Low K, et al. Rifaximin versus other antibiotics in the primary treatment and retreatment of bacterial overgrowth in IBS. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:169-174. Abstract

- Pimentel M, Morales W, Chua K, et al. Effects of rifaximin treatment and retreatment in nonconstipated IBS subjects. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2067-2072. Abstract

Faculty and Disclosures

As an organization accredited by the ACCME, Medscape, LLC, requires everyone who is in a position to control the content of an education activity to disclose all relevant financial relationships with any commercial interest. The ACCME defines "relevant financial relationships" as financial relationships in any amount, occurring within the past 12 months, including financial relationships of a spouse or life partner, that could create a conflict of interest.

Medscape, LLC, encourages Authors to identify investigational products or off-label uses of products regulated by the US Food and Drug Administration, at first mention and where appropriate in the content.

Brooks D. Cash, MD

Professor, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; Chief of Medicine, National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland

Disclosure: Brooks D. Cash, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships: Served as an advisor or consultant for: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc.; Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Prometheus Laboratories Inc. Served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc.; Prometheus Laboratories Inc. Received grants for clinical research from: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Dr. Cash does intend to discuss investigational drugs, mechanical devices, biologics, or diagnostics not approved by the FDA for use in the United States. Dr. Cash does intend to discuss off-label uses of drugs, mechanical devices, biologics, or diagnostics approved by the FDA for use in the United States.

Shari Weisenfeld, MD

Scientific Director, Medscape, LLC

Disclosure: Shari Weisenfeld, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A 32-Year-Old Woman With IBS: Clinical Outcomes and the Use of Antibiotics

Case presentation.

SN is a 32-year-old white woman who presents with symptoms of recurrent abdominal pain and loose stools. She states that she has experienced these symptoms since adolescence, with periods of improvement and worsening over the years. She notes that her symptoms were most pronounced when she was in college, and they improved during her pregnancy with her first child 4 years ago. Over the past year, her symptoms have been occurring more frequently and with greater severity. She also has been increasingly bothered by bloating and distention over the past 6 months. The bloating seems to worsen with food intake, while the distention progresses throughout the day. When questioned about abdominal pain, she describes it as 7 (on a scale of 10) at its worst and seemingly related to defecation, with acute worsening immediately prior to defecation and significant improvement after defecation. She has loose stools approximately one third of the time and often will have 2-3 bowel movements per day.

Other than her gastrointestinal symptoms, she considers herself healthy. She has no chronic illnesses or prior surgeries. She had an uncomplicated pregnancy and a vaginal delivery 4 years ago (gravida 1, para 1). She has no family history of organic gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy, or celiac disease.

SN is employed part time at an accounting firm. She jogs 2-3 miles 3-4 times a week, tries to eat 4-6 servings of fruits and vegetables daily, and takes a daily multivitamin, which she has taken for many years.

Her weight and other vital signs are within normal limits: height 5'6", weight 120 lb, blood pressure 108/64 mm Hg, pulse 60 beats per minute, and respiratory rate 12 breaths per minute.

On physical examination, she is a well-developed, well-nourished woman in no acute distress. Her physical examination is notable for mild tenderness to palpation in the left lower quadrant, but there is no rebound tenderness, guarding, or other peritoneal signs. The remainder of the physical examination is unremarkable.

IBS Presentations

The hallmark symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are abdominal pain or discomfort associated with at least two of the following characteristics: (1) pain or discomfort associated with a change in the form of the stool; (2) pain or discomfort associated with a change in the stool frequency; and/or (3) the pain or discomfort is relieved with defecation. The above characteristics are a liberal translation of the Rome III criteria for IBS. [1] The reality of clinical practice is that IBS can have a wide variety of clinical presentations. In addition to the "classic" symptom complex mentioned above, patients will often complain of other abdominal or defecatory symptoms such as bloating, gas, a prominent gastrocolic reflex, flatulence, distention, mucous in bowel movements, a sense of incomplete evacuation, and straining required for defecation.

IBS typically can be classified into 1 of 3 major categories, defined by the predominant stool pattern: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and mixed IBS (IBS-M). Each subgroup accounts for about one third of IBS patient presentations, although the percentage of each subtype may vary depending upon geography and patient population. [1]

Treatments and Clinical Trials

Treatment for IBS is typically directed at improving individual symptoms. For IBS-C this usually involves laxative therapies, and for IBS-D this usually involves antidiarrheal medications. Antispasmodic medications have long been used to target the pain and discomfort that patients often experience with IBS; however, there is no compelling evidence from clinical trials performed in the United States to support their use. Other common pharmacologic therapies prescribed for IBS include antidepressants, probiotics, and antibiotics.

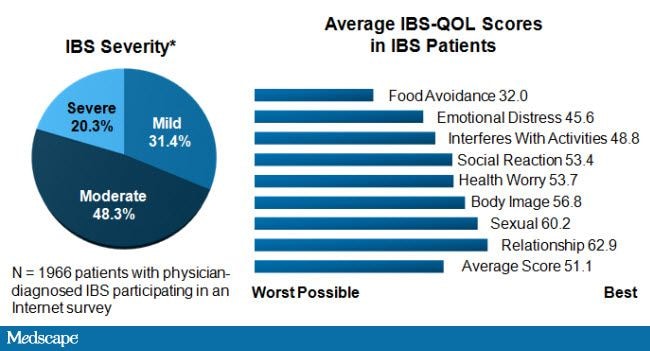

Just as therapy is often directed at specific symptoms, patient response in clinical practice is typically dependent on changes in those symptoms and can be highly variable. This is in contrast to the many clinical trials of therapies for IBS, where changes in composite or global symptom measures are used to assess therapeutic efficacy. It is important for clinicians to understand the differences between measures of efficacy in clinical trials and the individual responses seen in practice, while also recognizing the wide-ranging global effects of IBS on the lives of their patients so that they can move beyond simply asking about individual symptoms (Figure 1).

Figure 1. IBS profoundly affects QOL. Adapted from International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders; IBS patients: their illness experience and unmet need. Milwaukee, WI: International Foundation for Gastrointestinal Disorders; 2009.

IBS is a very subjective condition, without reliable biomarkers to help make the diagnosis or follow response to therapy, which has made developing clinical trial endpoints a difficult endeavor. Some trials evaluate the effects of therapy on individual IBS symptoms, while others use composite IBS scores or global IBS symptoms as their measure of efficacy. Still others use physiologic, rather than clinical, endpoints. Over the last decade, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has favored a global endpoint for phase 3 clinical trials. It remains unclear if this is the optimal approach, especially because so much of the routine clinical practice surrounding IBS is directed at alleviating the individual symptoms patients experience.

In recent years, the National Institutes of Health has embarked on developing improved measures for patient-reported outcomes. The Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) aims to provide clinicians and researchers access to efficient, precise, valid, and responsive adult- and child-reported measures of health and well-being. [2] The stated strategic goals of this program are to (1) create and promulgate a set of qualitative and quantitative methodological standards for development and validation of instruments; (2) launch a sustainable entity that is able to promote the research, development, and dissemination activities for the network; (3) identify and prioritize a set of research and development opportunities that include clinical applications; and (4) disseminate information in order to forge strategic alliances to enhance the adoption of these standards in research, clinical practice, and policy. Currently, investigators from the University of California, Los Angeles, are working on a project under this program to develop and test a "gastrointestinal distress scale" that may have significant applicability for future IBS clinical trials.

Perhaps because IBS is such a heterogeneous disorder, there is no single therapeutic approach that has proven to be the de facto "first-line" treatment strategy. Generally, the aim of treatments for conditions that do not result in long-term health sequelae or impaired life expectancy, such as IBS, is to minimize the costs and possible adverse effects of therapies.

Multiple studies have considered the effects of nonpharmacologic therapies for IBS as well, including fiber supplementation or bulking agents, food-restriction diets, and psychological/cognitive behavior-based treatments. Among these 3 categories, psychological therapies have the best evidence supporting their use.

Bulking agents have traditionally been felt to be ineffective therapies for IBS. [3] However, Bijkerk and colleagues recently compared psyllium, bran, and a rice-flour placebo among patients with IBS and found that the percentage of patients responding, defined as adequate symptom relief, was significantly greater than placebo in the first (primary endpoint) and second months of therapy. Additionally, treatment with bran 10 g/day was also significantly better than placebo during the third month of treatment. [4]

Dietary restriction has been used by many patients with IBS in order to minimize gastrointestinal symptoms. Typically this includes limiting foods containing dairy sugars such as lactose, foods containing gluten, and most recently limiting fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). Examples of FODMAPs include fructose and lactose, sorbitol, fructans, and raffinose, which humans do not express suitable hydrolases for and thus are always poorly absorbed. There are a number of studies that support FODMAP-restricted diets. In one study, 150 outpatients with IBS were randomly assigned to 3 months of a diet excluding all foods for which they had elevated immunoglobulin G antibodies (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test) or a sham diet excluding the same number of foods but not those to which they had antibodies. [5] After 12 weeks, the true diet resulted in a 10% greater reduction in symptom score than the sham diet (mean difference of 39.95% [95% confidence interval (CI), 5-72]; P = .024) and a 26% greater reduction in fully compliant patients (difference 98.95% [95% CI, 52-144]; P < .001). Global rating also significantly improved in the true-diet group as a whole ( P = .048, number needed to treat [NNT] = 9) and even more in compliant patients ( P = .006, NNT = 2.5). All other outcomes showed trends favoring the true diet, and relaxing the diet led to a 24% greater deterioration in symptoms in those on the true diet (difference 52 [95% CI, 18-88]; P = .003).

In another double-blinded, randomized, controlled trial, 25 patients who had responded to dietary change consisting of a FODMAP-restricted diet were rechallenged with reintroduction of fructose, fructans, alone or in combination, or glucose for a maximum test period of 2 weeks. [6] Approximately 70% of patients receiving fructose, 77% receiving fructans, and 79% receiving a mixture were not adequately controlled compared with 14% receiving glucose ( P ≤ .02). FODMAP-restricted diets can be difficult to adhere to; however, in patients with IBS and fructose malabsorption, dietary restriction of fructose and/or fructans may improve symptoms and is a reasonable treatment option.

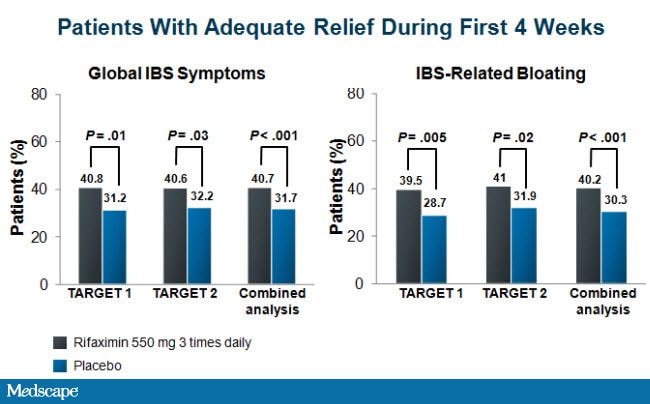

Another therapeutic strategy for IBS has emerged from investigations on the origins of IBS symptoms from the interaction of enteric bacteria with ingested carbohydrates. This theory has been popularized by multiple reports demonstrating that patients with IBS are more likely than non-IBS controls to have abnormal breath tests after ingestion of fermentable carbohydrates. [7] Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that normalization of breath tests with antibiotic therapy may be accompanied by an improvement in IBS symptoms. These observations have led to multiple trials using antibiotic therapy for IBS. [8] This area of research recently culminated with the publication of the TARGET 1 and 2 trials in the New England Journal of Medicine . [9] This report of the effects of antibiotic therapy for IBS by Pimentel and colleagues represents a major addition to the IBS therapy literature and details the results of 2 identical trials for nonconstipated IBS. Both of these large studies (n = 623 for TARGET 1; n = 637 for TARGET 2) were conducted in multiple sites throughout the United States and Canada and enrolled patients with mild to moderate symptoms of nonconstipation IBS according to the Rome II IBS diagnostic criteria. After a 1- to 2-week screening phase to confirm eligibility requirements, patients were randomly assigned via concealed allocation to receive either rifaximin or placebo, in a 1:1 ratio. After completing the 14-day treatment period, patients were evaluated for 10 additional weeks, in order to monitor the short-term durability of treatment effects and symptoms. Efficacy assessments were obtained daily by means of an interactive voice-response system over the course of the entire study and a clearly defined endpoint, adequate relief of global IBS symptoms for at least 2 of the 4 weeks during the primary evaluation period based on a binary response to a yes/no question. A key secondary endpoint, satisfactory relief of bloating, was assessed in a similar fashion as the primary endpoint over the same period of time.

In both studies, patients consistently fulfilled the criteria for relief of global IBS symptoms and bloating (Figure 2). A statistically significant proportion of patients randomly assigned to the rifaximin group, compared with those who received placebo, had adequate relief of global IBS symptoms (41% vs 32% pooled data, P < .001) and bloating (40% vs 30% pooled data, P < .001) for at least 2 of the first 4 weeks of the treatment assessment period. Moreover, these results were durable, with statistically significant differences favoring rifaximin for the relief of global symptoms and bloating through the10-week post-treatment observation period. Other important individual symptoms of IBS were assessed, including abdominal pain and stool consistency, and these endpoints were also more likely to improve with rifaximin compared with placebo. No clinically significant differences were observed in terms of treatment-emergent adverse events between patients in either treatment arm.

Figure 2. Efficacy of rifaximin in improving global IBS symptoms and IBS-related bloating. Adapted from Pimental M, et al. N Engl J Med . 2011;564:22-32. [9]

Clinical experience has demonstrated that rifaximin can significantly improve the gastrointestinal symptoms of some IBS patients. These results from the 2 large and well-designed clinical trials described offer convincing evidence that results that have been observed anecdotally for the last several years are in fact consistent and reproducible. The differences observed for the primary and secondary endpoints between rifaximin and placebo, while only 9%-10%, were similar to treatment differences observed in other phase 3 clinical trials of medications that have received FDA approval as therapies for IBS such as alosetron, tegaserod, and lubiprostone. [10-12]

The promising results of TARGET 1 and TARGET 2, however, do not completely resolve the issues surrounding the use of antibiotics for IBS. One of the most important questions remaining is the optimal means to identify probable responders. Some have suggested that breath test evidence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) should be used as a treatment criterion, but previous studies of antibiotic therapy for IBS have not convincingly demonstrated a strong correlation between normalization of breath tests and clinical response. [13] As a practical matter, many clinicians have used positive breath tests to obtain third-party reimbursement for rifaximin, which is an expensive medication in the 1200- to 1650-mg doses used for IBS. Another question surrounding the use of antibiotics and probiotics for IBS is exactly how they are exerting an effect on the gastrointestinal tract of patients with IBS who respond to these therapies. Popular theories hold that these medications may decrease the density of fermenting bacteria in the small bowel, but there are other theories, such as anti-inflammatory effects that lead to alterations in enteric motility, secretion, and sensitivity, which have been put forth as possible explanations. Another concern surrounds the possibility of resistance, but there are abundant data in the literature demonstrating the safety of nonabsorbed antibiotics with respect to this issue. [14] Another issue, one that was raised by the FDA in their review of the clinical trial data during the approval deliberations for rifaximin, is the durability of response. While treatment differences between rifaximin and placebo persisted throughout the conclusion of the 12-week study period, a gradual diminution of the relief of global IBS symptoms and bloating was observed in both groups as the trial progressed. This observation mirrors community-based clinical experience. While there can be a dramatic response in some patients, symptom recurrence at a variable point after rifaximin appears to be common. Data on recurrence and retreatment effects with rifaximin, or any other antibiotic used for IBS, are crucial to obtain as there is very little guidance in the literature. What data that exist suggest that responders who experience recurrent IBS symptoms will respond to retreatment. [15,16]

Case Conclusion

Based on her long history of typical symptoms and lack of alarm features, SN is diagnosed with IBS. Her description allows for further categorization as IBS-D with prominent bloating. A complete blood count, thyroid studies, celiac sprue, and pregnancy testing are ordered. Based upon her age, lack of risk factors and alarm features, and intermittent loose stools, there was a discussion with the patient, and a decision was made not to perform colonoscopy at this time. SN is given educational material regarding IBS, including important Websites with IBS information like the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Website.

SN is anxious to avoid medications, and thus lifestyle modification with a FODMAP-restricted diet is prescribed. She returns 4 weeks later without symptom improvement, admitting that the diet was difficult to adhere to, particularly with other family members to consider. Her laboratory results are within normal limits. Rifaximin (550 mg 3 times a day for 14 days) is prescribed along with loperamide. SN is advised to begin with 2 mg of loperamide every morning and to increase by an additional 2 mg every week if her stool remains frequently soft and runny and to decrease to every other day should constipation occur.

SN returns after 4 weeks on this therapy and reports that her bloating and distention have almost completely resolved, her bowel habits are more predictable, and she has more solid stool. She reports occasional cramping and abdominal discomfort that signals the need to defecate, but this has been minimal and short lived. She does not want to pursue additional medical therapy at this time. She also has made some small changes to her diet like decreasing the amount and frequency of cruciferous vegetable and legumes she consumes, and she feels that this has helped her symptoms. She is advised about possible symptom recurrence over the next 6 months, especially bloating, and she has agreed to contact you for retreatment with rifaximin if she experiences a recurrence of symptoms.

Supported by an independent educational grant from Salix Pharmaceuticals.

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of Medscape, LLC, or companies that support educational programming on www.medscape.org. These materials may discuss therapeutic products that have not been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and off-label uses of approved products. A qualified healthcare professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. Readers should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this educational activity.

Medscape Education © 2011 Medscape, LLC

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2021

Pain and psyche in a patient with irritable bowel syndrome: chicken or egg? A time series case report

- Felicitas Engel 1 ,

- Tatjana Stadnitski 2 ,

- Esther Stroe-Kunold 1 ,

- Sabrina Berens 1 ,

- Rainer Schaefert 1 , 3 &

- Beate Wild ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2279-8135 1

BMC Gastroenterology volume 21 , Article number: 309 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

2571 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) appears to have a bidirectional interaction with both depressive and anxiety-related complaints. However, it remains unclear how exactly the psychological complaints, at the individual level, are related to somatic symptoms on a daily basis. This single case study investigates how somatic and psychological variables are temporally related in a patient with irritable bowel syndrome.

The patient was a woman in her mid-twenties with an IBS diagnosis. She reported frequent soft bowel movements (5–6 times per day), as well as flatulence and abdominal pain. She resembled a typical IBS patient; however, a marked feature of the patient was her high motivation for psychosomatic treatment as well as her willingness to try new strategies regarding the management of her symptoms. As an innovative approach this single case study used a longitudinal, observational, time series design. The patient answered questions regarding somatic and psychological variables daily over a period of twelve weeks with an online diary. The diary data was analysed using an autoregressive (VAR) modeling approach. Time series analyses showed that in most variables, strong same-day correlations between somatic (abdominal pain, daily impairment) and psychological time series (including coping strategies) were present. The day-lagged relationships indicated that higher values in abdominal pain on one day were predictive of higher values in the psychological variables on the following day (e.g. nervousness, tension, catastrophizing, hopelessness). The use of positive thinking as a coping strategy was helpful in reducing the pain on the following days.

In the presented case we found a high correlation between variables, with somatic symptoms temporally preceding psychological variables. In addition, for this patient, the use of positive thoughts as a coping strategy was helpful in reducing pain.

Peer Review reports

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is characterized by recurrent abdominal pain that is associated with a change in frequency or form (appearance) of stool and can be related to defecation [ 1 ]. Currently, the symptom pattern is not sufficiently explained by peripheral organ pathology. IBS affects about 8% of the European population [ 2 ] and is most recently understood as a disorder of (microbiota-) gut-brain interaction [ 3 , 4 ] with a multifactorial origin that includes biological, psychological, and social factors [ 5 ]. Many patients who suffer from IBS also suffer from comorbid depressive or anxiety-related disorders [ 5 ]. Mood and anxiety disorders can precede or follow an IBS diagnosis due to the high discomfort caused by IBS [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. By looking at specific psychological variables it was found that catastrophizing is directly associated with IBS symptom severity, while anxiety is indirectly related to IBS symptom severity [ 9 ].

While population-based studies suggest that IBS has a bidirectional interaction with both depressive and anxiety-related complaints, it remains unclear how exactly the psychological complaints, at the individual level, are related to somatic symptoms on a daily basis. Are increased psychological complaints (such as depression, tension, and nervousness) on one day preceded by IBS complaints on the previous day, or is it the other way around? A previous study showed that week-to-week stress and IBS symptoms were strongly cross-correlated in the same week, but were not temporally related across several weeks [ 10 ]. However, a day-by-day measure is needed to identify more fine-grained and direct relations. Furthermore, the focus of the study was on the mean values from a large patient sample, therefore potentially differing relationships in individual patients may not have been reflected in the aggregated data analysis.

Another interesting topic in patients suffering from IBS is the mutual relationship between coping strategies and IBS symptoms. A recent study reported that levels of coping resources were associated with gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptom severity [ 11 ]. Also, catastrophizing and a lower self-perceived ability to reduce symptoms appeared to have a negative effect on health outcome in gastrointestinal disorders [ 12 ]. Interestingly, IBS patients have been reported to use passive coping strategies more frequently (such as escape-avoidance strategies instead of intended problem solving) compared to healthy controls [ 13 ]. Here too, the question arises to what extent coping strategies are related to IBS complaints and whether or not they are able to influence IBS complaints.

Overall, IBS symptoms and psychological distress are bi-directionally related, and coping strategies purportedly play an important role in the up- or down-regulation of IBS symptoms. However, individual mechanisms are not yet understood, and previous studies lack the longitudinal data on a day-by-day basis. Longitudinal data is necessary in order to obtain information about direct interactions, to better understand how temporal interactions between IBS symptoms and psychological complaints are related. As aggregated data can eliminate individual effects within the heterogeneous IBS patient sample, a single case study can provide important insights into specific mechanism to generate hypotheses for personalized clinical studies [ 14 ]. Conversely, inferences from singe case studies do not automatically apply to the patient population. However, results from single case studies can be used to generate hypotheses that can be examined in a sample of patients with similar characteristics.

This case study has, for the first time, applied a longitudinal time series design to a patient with IBS. Study objectives of this single-case analysis were: (1) to explore temporal relationships and interactions between the somatic and psychological complaints of the patient and (2) to investigate the impact of personal coping strategies on somatic symptoms.

Case presentation

Study design.

The study used a longitudinal, observational, single-case design. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Hospital Heidelberg. The patient was recruited in the frame of a pilot intervention study, conducted between July, 2014 and June, 2015 [ 15 ]. During her waiting period—and before the beginning of the therapy group—the patient answered questions daily regarding somatic and psychological complaints as well as coping strategies with the use of an online diary.

The diary data of the patient was collected following presentation in our outpatient specialty clinic for functional gastrointestinal disorders [ 16 ], and before group therapy. The data thereby showed the classic course of IBS without specific group intervention. The patient filled out the diaries from 10/2014 to 01/2015; over twelve weeks a total of 72 diary days were collected.

Measurements in the online diary

At the beginning of the study the patient received individual training in how to use the online diary; she was instructed to fill out the diary on a daily basis (between 4 pm and 12 am) via internet access. Validated questionnaires for IBS, as well as for psychological complaints and coping strategies, were used and adapted for the daily diary design. The most discriminating items of the questionnaires were derived in order to shorten the completion time of the diary (approximately 5–10 min). All items were rated by a visual analogue scale (VAS) with bipolar labels. The marked points were then converted by the computer program to a numeric scale ranging from 1 to 101. In addition, it was possible to enter a short free text in the diary.

For the measurement of somatic symptoms, we used the items “How severe is your abdominal (tummy) pain?” and “Please indicate how much your irritable bowel syndrome is affecting or interfering with your life today?”. Higher scores on these items reflected higher pain or higher somatic impairment. Psychological variables and coping strategies measured in the online diary are shown in Table 1 .

In January 2014, a German student (female in her mid-twenties), was referred to the outpatient specialty clinic of the University Hospital of Heidelberg for functional gastrointestinal disorders. She reported frequent soft bowel movements (5–6 times per day), as well as flatulence and abdominal pain. According to ROM-III [ 22 ] and the clinical assessment, an IBS (subtype IBS-diarrhea, IBS-D) was diagnosed. In addition, the patient was suffering from comorbid gluten, lactose, and sorbitol intolerance. No mental illness was present. Despite professional nutritional advice that included a gluten-, lactose- and sorbitol-reduced diet, gastrointestinal complaints persisted. In the course of the three-month follow-up appointments that included multimodal treatment [ 16 ] (04/2014, 07/2014, 11/2014), the patient correlated intestinal complaints and stress. She reported, for example, that the intestinal symptoms increased at the beginning of the semester and in the examination period. In the course of the diary study the patient did not describe any long-lasting stressor (such as an examination phase), but rather shorter week- or day-specific stressful events (such as Christmas holidays or looking for a part-time job) associated with an onset of IBS-symptoms on the same day. As an additional stressor, she described shame and the fear of a recurrence of the IBS complaints (particularly of soft bowel movements and flatulence), especially in social settings and situations where she could not easily reach a toilet. Relaxation techniques (yoga and gut-directed hypnosis using a CD) slightly improved her symptoms and the associated fear. Regarding the short stressful events, she described a good improvement of symptoms when using a strategy of calming down, with no further subsequent exacerbation. After the online diary study presented here, the patient received a group intervention [ 15 ] from which she has benefited.

In conclusion, according to IBS symptoms, symptom specific fears and avoidance behavior, the presented case of a young female patient resembled a typical IBS patient; however, a marked feature of the patient was her high motivation for psychosomatic treatment as well as her willingness to try new strategies regarding the management of her symptoms.

Statistical analysis

Initially, the following analyses were conducted for each time series: graphic examinations; calculations of descriptive statistics (range, median, mean, standard deviation), autocorrelation functions (ACF), and tests for stationarity with the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) procedure. Autocorrelation is the bivariate correlation of a time series with a lagged copy of itself. Therefore, instantaneous (lag = 0) autocorrelation is always equals one, significant autocorrelations on other lags imply predictability of the future time series values from the past values. Stability or instability as well as memory characteristics of time series can be inferred from their autocorrelation functions: non-zero autocorrelations at only a few lags are typical for stable short-memory processes, whereas significant autocorrelations on many lags indicate long memory or instability. Stationarity means that the statistical characteristics of a process under study do not change over time (e.g., exhibit no trends or distinct fluctuations of mean or variance). The Augmented Dickey-Fuller algorithms tests the null hypothesis “time series is stationary”.

In addition, cross-correlation functions (CCF), instantaneous correlations, and simultaneous regressions with psychological measures—both as dependent and somatic variables as predictors—were estimated. Cross-correlation measures similarity of two different time series as a function of the displacement of one relative to the other. Generally, instantaneous (lag = 0) correlations or simultaneous (lag = 0) regressions do not imply causation. For lagged correlations and regressions, however, it is different, since they explore the ability to predict the future values of a time series from prior values of another times series. The idea behind this is as follows: Since time does not run backwards, the cause cannot come after its effect. Therefore, events in the past can cause events to happen today, but future events cannot influence the present. The concept of Granger causality incorporates this idea: if lagged values of a time series X improve prediction of future values of a series Y, the former series Granger-causes the latter. For example, if lagged values of a somatic times series improve prediction of future values of a psychological one, the former series Granger-causes the latter. The vector autoregressive (VAR) methodology investigated the temporal dynamics between two or more time series by separating the time-lagged from the simultaneous relations. Therefore, temporal interdependencies between time series were analyzed using this approach. The VAR technique thereby allowed inferences about the temporal order of the effects by employing the temporal causality concept introduced by Granger. Furthermore, the VAR approach can handle time series that mutually influence each other and thus reveal feedback effects. In VAR modelling, interpretation of the regression coefficients is problematic because the lagged values of the dependent variables are used as predictors (i.e. dependent and independent variables are both endogenous, that is, determined and interrelated inside the organism or system), consequently, external influences can enter the autoregressive system exclusively through the residual term, which is also called “exogenous shock”. The behaviour of a VAR system can be modelled using impulse response analyses (IRA) and forecast error variance decompositions (FEVD). Impulse response functions (IRF) examine interdependencies within a VAR system by tracing the effect of an exogenous shock in one of the series on other variables. The FEVD estimates the amount of variance in each variable that can be explained by the other variables of the system during a specific period (h). For instance, in case of daily measurements, FEVD = 0.24 (h = 10) means that 24% of the forecast error variance in a dependent variable can be explained by exogenous shocks (random changes) of the predictors for a time horizon of 10 days.

The analyses were conducted using the R software. (Please consult Stadnitski & Wild (2019) and Stadnitski (2014, 2020) for descriptions, detailed explanations, and implementation of all analyses with the R software [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]).

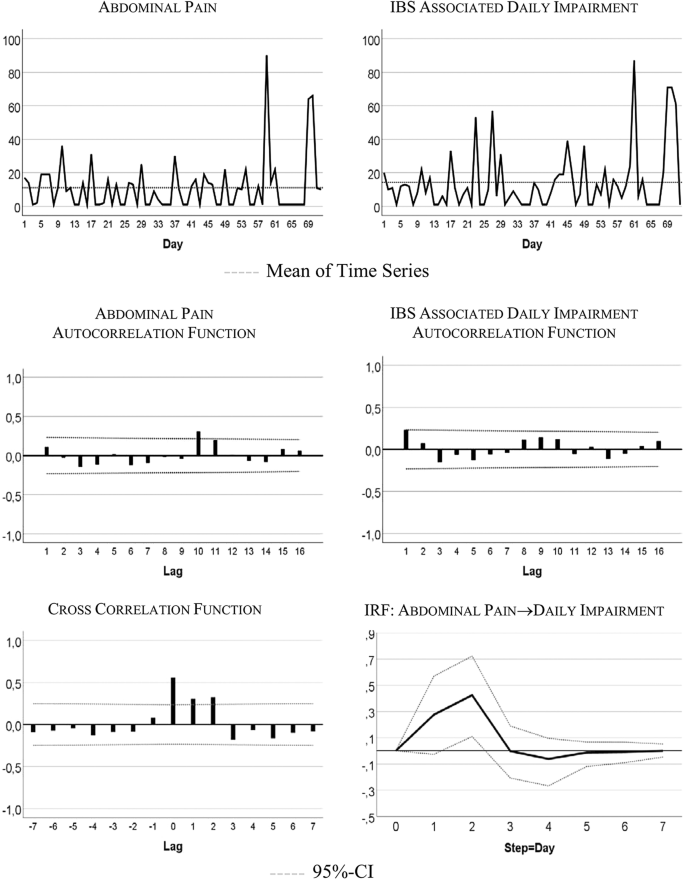

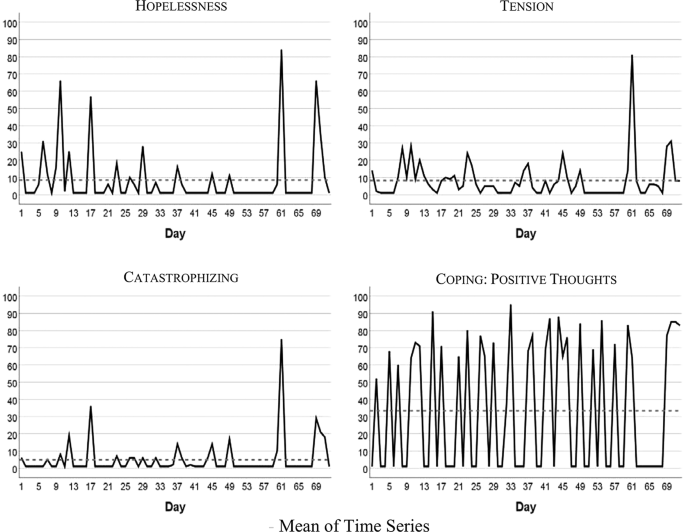

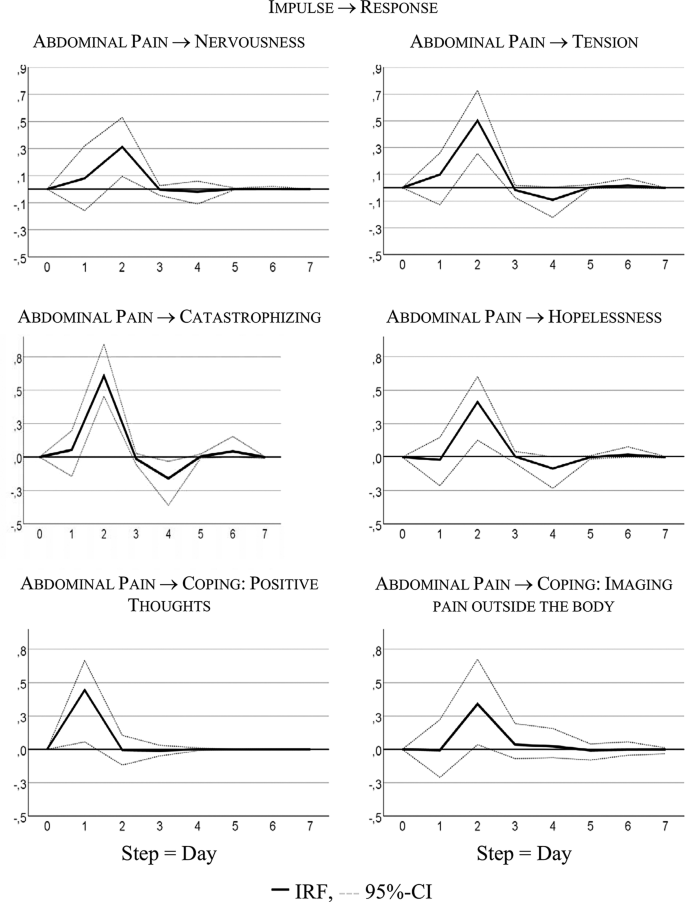

Figure 1 visualizes the patient’s development of somatic symptoms, abdominal pain (AP), and daily impairment (DI) over 72 successive days together with their autocorrelation and cross-correlation function. In both series there appeared strong discomfort with values distinctly higher than 20 on 7 days. Almost 90% of the measurements varied between 1 and 20 on the 100-point scale. The average (Mean AP = 11.10, DI = 14.35) and variability (Standard Deviation: AP = 15.90, DI = 18.55) were higher for DI than AP (see also Table 2 ). Both time series exhibited no trends. Figure 2 shows the time series of additional psychological variables and coping strategies.

Somatic time series: abdominal pain (AP) and IBS-associated daily impairment (DI)

Time series of hopelessness, tension, catastrophizing, coping

The time series quantitatively reflect the free text descriptions of the patient. The highest scores in AP and DI were recorded between days 57 and 68 of the study period. In the free text passages of the diary the patient noted that she experienced the Christmas holidays (days 52–67) as a period of high stress and increased IBS pain. In addition, on days 59–61 she described the occurrence of menstrual cramps together with IBS-associated pain and impairment.

Table 2 summarizes characteristics of somatic and psychological and coping time series. In the majority of cases all of the series except “Coping with positive thoughts” (CPT) ranged between 1 and 20 on the 100-point scale, with high values observed about 10% of the time. CPT values alternated between very low and high with values equal on 1 out of 40 days, and values higher than 50 on 31 days. All series were stationary, i.e., exhibited no trends. Three series (tension, catastrophizing, and hopelessness) demonstrated no autocorrelations.

Table 3 shows instantaneous correlations between the somatic and psychological (including coping) time series. In most cases, strong and positive correlations were observed. Interestingly, the relationship between psychological and coping variables with DI was stronger than with AP. The amount of predicted variance (R 2 ) from linear regressions with psychological and coping measures as dependent variables and somatic variables as predictors varied between 12 and 94%. The non-significant correlation between depressiveness and abdominal pain could be due to the very limited range of the variable depressiveness over the course of the 72 days.

Table 4 summarizes the significant results of the VAR analyses for interdependencies between abdominal pain and psychological distress or coping strategies; only statistically significant findings from calculations for all possible combinations of variables are provided. Identified lagged or temporal relations showed mostly the same direction, indicating that previous values in the somatic variable (AP) were predictive of values in the psychological variables or coping strategies. The variance decomposition estimates show that somatic symptoms in the psychological (and coping) time series explain 12% to 41% of variability.

Figure 3 visualizes responses of psychological states and coping strategies to increases in AP; it shows that psychological and coping aspects reacted with higher symptoms to an increase in AP. For instance, increasing AP caused a strong delayed increase in catastrophizing: + 0.60 standard deviations, i.e., about 7 points on the 100-point scale.

Time lagged psychological variables

Table 4 shows that the bivariate system, including AP and CPT, is characterized by a bidirectional or feedback predictive causality. AP Granger-caused CPT with 24% of explained variance, CPT Granger-caused AP with 6% of explained variance. Both series also correlated instantaneously: r = 0.43, R² = 18%.

Figure 4 visualizes the feedback relationship. An increase in AP caused more CPT next day. Intensified CPT resulted in less pain on the subsequent day: i.e., a decrease of 0.25 standard deviations, 4-point on the 100-point scale.

Cross-correlation and time lagged relationships: abdominal pain (AP) and coping with positive thoughts (CPT)

Discussion and conclusion

This is the first study to investigate the temporal relationships between somatic and psychological variables on a daily basis. We analyzed a female patient with IBS in her mid-twenties with symptoms of diarrhea, flatulence, and abdominal pain. She reported stress-related IBS symptoms as well as symptom related fears. In most variables, strong same-day correlations between somatic (especially daily impairment) and psychological (including coping) time series were observed. The day-lagged relationships indicated that higher values in abdominal pain on one day were predictive of higher values in psychological complaints (nervousness and tension) or of negative coping strategies (catastrophizing, hopelessness) on the following day. The use of positive thinking as a positive coping strategy was helpful in reducing the pain on the following days.

All variables remained stationary—that is, time series exhibited no trends over the measured time period (72 days). In the study period, the patient did not receive additional psychotherapeutic treatment, nor did she report long-lasting stressors. Therefore, we did not expect her symptoms to change over a longer period of time. The stability of IBS symptoms is supported by literature that usually describes IBS as a chronic disease. The diagnostic criteria for IBS also imply some symptom stability, because the symptoms must occur for a period of at least 3 months (with an onset at least 6 months prior the diagnosis) [ 22 ]. In addition, for IBS, population-based studies report a remission rate of about 55% only over a period of more than 10 years [ 26 ]. In addition to the general stationary trend of the variables, individual outliers with more severe symptoms were visible (e.g. the Christmas Holidays on days 52–67).

The patient stated that stressful or stress-free episodes would influence her symptoms; this was also reflected in the same-day analysis. In the free text of the diary the patient also described that in specific stressful situations she was ashamed of her symptoms and related consequences. The high same-day correlations between the somatic (AP, DI) and psychological time series (nervousness, tension, depressiveness, catastrophizing, hopelessness) reflect this interdependency—which the patient is aware of—between IBS symptoms and psychological state. Interestingly, this correlation was even higher for DI, meaning that functionality is especially important. The interaction between somatic and psychological distress is also described in previous studies. Midenfjord et al. (2019), for instance, showed in a cross-sectional study that IBS patients with psychological distress demonstrated more severe somatic symptoms and a lower quality of life [ 27 ]. Varni et al. (2017) found in a sample of pediatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders that somatic symptoms were differentially related to decreased health-related quality of life [ 28 ]. Another study reported a correlation between pain intensity and intensity of psychopathological symptoms (such as low spirits or anxiety) in IBS patients [ 29 ] while Dong et al. (2020) showed that IBS symptom severity predicted health-related quality of life influenced by stressful life events [ 30 ]. Interestingly, there is evidence that this association between current abdominal symptoms and psychological distress is not limited to functional gastrointestinal diseases but can also be seen in inflammatory bowel diseases [ 31 ]. The underlying physiological mechanism for the interaction between somatic and psychological distress could be explained by the concept of the (microbiome-) gut-brain axis. The (microbiome-)gut-brain axis refers to the complex network of connections between the microbiota, the enteric nervous system, and the central nervous system. [ 3 , 4 , 32 , 33 ]. Previous research has shown that the link between gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological distress could be based on a complex and bidirectional interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors [ 5 ]. For example, visceral hypersensitivity and an enhanced perceptual response to gastrointestinal sensations can trigger gastrointestinal specific anxiety [ 5 , 32 ]. On the other hand, psychosocial distress can lead, for instance, to an activation of the enteric and autonomic nervous system, which may trigger a change in smooth muscle activity or glandular secretion thus leading to IBS-symptoms. [ 32 ].

In addition to the daily correlation, it is also useful to look at day-to-day relationships in order to make time-delayed effects more visible and to answer the question whether or not psychological complaints precede IBS complaints, or vice versa. In literature, both perspectives are described for mental illnesses and IBS [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. However, for this particular patient we found a strong time-delayed relationship between IBS symptoms, the following psychological complaints (nervousness, tension), and negative coping strategies (catastrophizing, hopelessness). This shows that having abdominal pain on one day was associated with more psychological stress the next day, not vice versa. This is in line with another study showing the temporal relationship that abdominal symptoms lead to increased stress and negative affect, while increased daily life stressors even lowered the IBS-symptoms [ 34 ]. This is interesting, as in literature frequently the opposite temporal direction or a feedback-loop is assumed [ 35 ]. Patel et al. (2016), for instance, investigated the relationship between sleep, mood and somatic symptoms in a sample of IBS patients and healthy controls over the course of 7 days [ 36 ]. In IBS patients, sleep disturbances were predictive for abdominal pain on the following day. Additional analyses showed that the sleep effects on abdominal pain in IBS patients could be mediated by depression and anxiety [ 36 ].

The question arises why our data show that the patient first develops gastrointestinal complaints and only afterwards psychological complaints. The patient herself had the impression that increased stress would lead to an increase in symptoms. For instance, during the short stressful event of applying for a new job the patient reported an onset of IBS complaints. She also reported that in this case the immediate application of a coping strategy (such as calming down) had helped her to reduce the symptoms. However, this sequence occurred over the course of only several hours—and would thus be reflected in the high same-day correlations of the time series (and not in the day-lagged correlations). On the other hand, shorter time intervals had been tested in Chan's study with an outcome similar to ours [ 34 ]. It is also possible that shorter daily stressors could also lead to a distraction from the IBS-symptoms, while longer stressors (like Christmas Holidays in the case of our study) may lead to an increase in symptoms.

Another interesting approach to feelings and symptoms of IBS is the concept of alexithymia. This concept states, among others, that feelings in IBS-patients may be misinterpreted as negative bodily sensations [ 37 ]. For our patient, this could mean that in stressful situations (such as job search or exam phases) she may initially perceive her feelings only physically and interpret them as a preliminary stage of a new outbreak of her IBS. The hyper-focus on the symptoms could initially intensify them. Shortly afterwards, the patient may get negative feelings from the IBS symptoms themselves.

The time-lagged correlation between IBS complaints and the following psychological complaints and negative coping strategies could be related to the patient’s social anxiety and the pressure to perform. In the free text of the diary the patient described that with the occurrence of abdominal complaints she would fear that soft bowel movements would follow, and that she would not be able to reach a toilet in a timely manner; she also felt ashamed when she had to leave certain events because of her IBS symptoms. Physiologically, this relationship between IBS complaints and following psychological distress could again be explained by the (microbiome-)gut-brain axis [ 5 , 32 ]. The occurrence of abdominal complaints (maybe as an expression of visceral hypersensitivity) can trigger gastrointestinal specific anxiety and the autonomic nervous systems as well as the hypothalamic pituitary axis are sending stress signals to the gut, resulting, among others, in a higher bowel motility and secretion leading to diarrhea and pain [ 32 ].

Interestingly, abdominal pain was not associated with a depressive feeling in general, but with negative processing (such as hopelessness and catastrophizing) as well as tense or anxious arousal (nervousness, tension). These negative feelings and coping strategies had no effect on the patient’s increased abdominal pain the next day; in contrast, the use of positive coping strategies was helpful.

The patient reported using positive coping strategies to reduce her symptoms; this was also seen in the data analysis. The intensified use of a specific coping strategy on one day (thinking of things the patient enjoyed doing) was followed by a decrease in pain on the subsequent day. Conversely, an increase in pain was followed by an increased use of this coping strategy. This corresponds to the clinical impression and the self-report of the patient: She considered relaxation techniques and new coping strategies such as distraction as beneficial for her condition. This result is supported by literature that considers psychotherapeutic treatment, including positive coping strategies, as a possible treatment of IBS [ 38 ].

In summary, the results of the time series analysis partly reflect the self-report of the patient as well as the clinical impression of the outpatient caretaker. However, our results expand upon these insights by showing temporal relationships between IBS symptoms and psychological variables over consecutive days—with psychological changes following changes in abdominal pain and related impairment. In addition, a mutual day-lagged relationship between IBS symptoms and coping could be detected.

This study has several implications: Overall, it shows that at the very least this patient is aware of her individual process of personal change, her fears, and her coping strategies––all of which to a large extent, could be confirmed by the time series analysis––an analysis that also provided additional information. This supports the hypothesis that individual characterizations are promising in terms of providing a better understanding of specific mechanisms, as well as an understanding of how temporal interactions between IBS symptoms and psychological symptoms are related. In clinical practice, practitioners should consider individual explanatory models of aggravating factors and coping strategies and stay open to psychosomatic as well as somatopsychic mechanisms. Previous psychological treatment recommendations for IBS patients concluded that a change in illness-specific cognitions as well as gastrointestinal anxiety as key mechanisms may have an effect on the outcomes of IBS symptom severity and quality of life [ 39 ]. In this case study, only positive thinking had a time-lagged effect on a decrease in abdominal pain, while catastrophizing and hopelessness were a result of having abdominal pain previously. Although it is not possible to generalize the results of an individual case, this supports the fact that treatments which more directly target abdominal symptoms (e.g., hypnotherapy) may have promising effects on IBS symptoms as well as associated psychological complaints. Therefore, a disorder-oriented integrative group intervention for IBS with gut-directed hypnotherapy seems promising [ 15 ].

From a methodological point of view, we have to point out that the here applied concept of Granger-causality does not equal causality. Causality according to Hill [ 40 ] can be assessed by using the following 9 criteria: strength, consistency, specificity, temporality, biological gradient, plausibility, coherence, experiment, analogy. The definition of Granger-causality, however, implies only that previous values of a time series X (e.g. somatic symptoms) improve prediction of future values of another series Y (e.g. nervousness of the patient). It does not imply the causality of X for Y.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, we examined only one patient suffering from IBS; the generalizability of the results is therefore limited. We cannot simply transfer the results to other IBS patients but must carefully investigate further patient samples in regard to temporal relationships and interactions between somatic and psychological variables. Secondly, we were able to detect day-to-day changes only; shorter periods of time could not be captured. Nevertheless, previous studies mainly focused on longer time periods which is why this approach is still more advantageous in terms of capturing the direct relationships. Nevertheless, we were able to show a clear picture of a single IBS-patient. This is helpful as IBS is a complex illness with, in all likelihood, heterogeneous genesis and factors. A comprehensive case study could help identify subclasses of IBS to arrive at a better treatment and avoid dilution effects.

In conclusion we found in the presented case that somatic symptoms temporally precede psychological complaints. In addition, for this patient, the use of positive thoughts as a coping strategy was helpful in reducing pain. Further analyses should be conducted to verify if these relationships can be found in other patients who suffer from IBS symptoms.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Irritable bowel syndrome

Abdominal pain

IBS-associated daily impairment

Nervousness

Depressiveness

Pain-associated discomfort

Catastrophizing

Hopelessness

Coping with positive thoughts

Coping with imagining pain outside the body

Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in Rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151–63.

Article Google Scholar

Sperber AD, Dumitrascu D, Fukudo S, Gerson C, Ghoshal UC, Gwee KA, Hungin APS, Kang J-Y, Minhu C, Schmulson M. The global prevalence of IBS in adults remains elusive due to the heterogeneity of studies: a Rome Foundation working team literature review. Gut. 2017;66:1075-82.

Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV-functional GI disorders: disorders of gut-brain interaction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1257–61.

De Palma G, Collins SM, Bercik P, Verdu EF. The microbiota-gut-brain axis in gastrointestinal disorders: stressed bugs, stressed brain or both? J Physiol. 2014;592(Pt 14):2989–97.

Van Oudenhove L, Levy RL, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, Halpert AD, Keefer L, Lackner JM, Murphy TB, Naliboff BD. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders: how central and environmental processes contribute to the development and expression of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(6):1355–67.

Jones MP, Tack J, Van Oudenhove L, Walker MM, Holtmann G, Koloski NA, Talley NJ. Mood and anxiety disorders precede development of functional gastrointestinal disorders in patients but not in the population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017; 15(7):1014–1020 e1014.

Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Axon AT, Moayyedi P. Irritable bowel syndrome: a 10-yr natural history of symptoms and factors that influence consultation behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(5):1229–39.

Koloski NA, Jones M, Talley NJ. Evidence that independent gut-to-brain and brain-to-gut pathways operate in the irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: a 1-year population-based prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(6):592–600.

Article CAS Google Scholar

van Tilburg MA, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Which psychological factors exacerbate irritable bowel syndrome? Development of a comprehensive model. J Psychosom Res. 2013;74(6):486–92.

Blanchard EB, Lackner JM, Jaccard J, Rowell D, Carosella AM, Powell C, Sanders K, Krasner S, Kuhn E. The role of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(2):119–28.

Wilpart K, Tornblom H, Svedlund J, Tack JF, Simren M, Van Oudenhove L. Coping skills are associated with gastrointestinal symptom severity and somatization in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(10):1565–71.

Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z, Keefe F, Hu YJ, Toomey TC. Effects of coping on health outcome among women with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(3):309–17.

Jones MP, Wessinger S, Crowell MD. Coping strategies and interpersonal support in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(4):474–81.

Gagnier JJ, Kienle G, Altman DG, Moher D, Sox H, Riley D, Group C. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):46–51.

Berens S, Stroe-Kunold E, Kraus F, Tesarz J, Gauss A, Niesler B, Herzog W, Schaefert R. Pilot-RCT of an integrative group therapy for patients with refractory irritable bowel syndrome (ISRCTN02977330). J Psychosom Res. 2018;105:72–9.

Berens S, Kraus F, Gauss A, Tesarz J, Herzog W, Niesler B, Stroe-Kunold E, Schaefert R. A specialty clinic for functional gastrointestinal disorders in tertiary care: concept and patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(7):1127–9.

Francis CY, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. The irritable bowel severity scoring system: a simple method of monitoring irritable bowel syndrome and its progress. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(2):395–402.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(2):258–66.

Robinson ME, Riley JL, Myers CD, Sadler IJ, Kvaal SA, Geisser ME, Keefe FJ. The Coping Strategies Questionnaire: a large sample, item level factor analysis. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(1):43–9.

Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1480–91.

Stadnitski T. Multivariate time series analyses for psychological research: VAR, SVAR, VEC, SVEC models and cointegration as useful tools for understanding psychological processes. Hamburg: Dr. Kovač; 2014.

Stadnitski T, Wild B. How to deal with temporal relationships between biopsychosocial variables: a practical guide to time series analysis. Psychosom Med. 2019;81(3):289–304.

Stadnitski T. Time series analyses with psychometric data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231785.

Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, Bjornsson E, Thjodleifsson B. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: comparison of two longitudinal population-based studies. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44(3):211–7.

Midenfjord I, Polster A, Sjovall H, Tornblom H, Simren M. Anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome: Exploring the interaction with other symptoms and pathophysiology using multivariate analyses. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(8):e13619.

Varni JW, Shulman RJ, Self MM, Nurko S, Saps M, Saeed SA, Patel AS, Dark CV, Bendo CB, Pohl JF, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms predictors of health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(4):1015–25.

Gorczyca R, Filip R, Walczak E. Psychological aspects of pain. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2013; Spec no. 1:23–27.

Dong Y, Baumeister D, Berens S, Eich W, Tesarz J. Stressful Life Events moderate the relationship between changes in symptom severity and health-related quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(5):445–51.

Berens S, Schaefert R, Baumeister D, Gauss A, Eich W, Tesarz J. Does symptom activity explain psychological differences in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease? Results from a multi-center cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2019;126:109836.

Tait C, Sayuk GS. The Brain-Gut-Microbiotal Axis: a framework for understanding functional GI illness and their therapeutic interventions. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;84:1–9.

Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G. Irritable bowel syndrome: a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(39):14105–25.

Chan Y, So SH, Mak ADP, Siah KTH, Chan W, Wu JCY. The temporal relationship of daily life stress, emotions, and bowel symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome-Diarrhea subtype: a smartphone-based experience sampling study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;31(3):e13514.

Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016; 150(6):1262–1279. e1262.

Patel A, Hasak S, Cassell B, Ciorba MA, Vivio EE, Kumar M, Gyawali CP, Sayuk GS. Effects of disturbed sleep on gastrointestinal and somatic pain symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(3):246–58.

Kano M, Endo Y, Fukudo S. Association between alexithymia and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Front Psychol. 2018;9:599.

Torkzadeh F, Danesh M, Mirbagher L, Daghaghzadeh H, Emami MH. Relations between coping skills, symptom severity, psychological symptoms, and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:72.

Windgassen S, Moss-Morris R, Chilcot J, Sibelli A, Goldsmith K, Chalder T. The journey between brain and gut: a systematic review of psychological mechanisms of treatment effect in irritable bowel syndrome. Br J Health Psychol. 2017;22(4):701–36.

Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295–300.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participating patient and the contributing research assistants.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of General Internal Medicine and Psychosomatics, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 410, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Felicitas Engel, Esther Stroe-Kunold, Sabrina Berens, Rainer Schaefert & Beate Wild

Department of Quantitative Methods in Psychology, University of Ulm, Albert-Einstein-Allee 47, 89081, Ulm, Germany

Tatjana Stadnitski

Department of Psychosomatic Medicine, Division of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Basel, Hebelstrasse 2, 4031, Basel, Switzerland

Rainer Schaefert

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BW, FE, ES and RS conceived and designed the study. FE, SB, ES and RS collected the data. TS statistically analyzed and all authors interpreted the data. FE, BW and TS drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and provided important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Beate Wild .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of the University Hospital Heidelberg.

Consent for publication

The patient gave written informed consent for analysis and publication of the data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Engel, F., Stadnitski, T., Stroe-Kunold, E. et al. Pain and psyche in a patient with irritable bowel syndrome: chicken or egg? A time series case report. BMC Gastroenterol 21 , 309 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01879-2

Download citation

Received : 06 October 2020

Accepted : 08 July 2021

Published : 03 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01879-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Functional gastrointestinal disorders

- Time series analysis

- Single case study

BMC Gastroenterology

ISSN: 1471-230X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Remember Me

- Nutrition counsellor

- Food Allergy

- gastroenterology

- Heptologist In Delhi

- Liver transplant

Case Study On IBS

- Case Study On Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

What does Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) mean?

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), also known as mucus colitis, nervous colon, and spastic colitis. IBS is a common functional disorder of the gastrointestinal tract. It is characterized by current episodes of abdominal pain, bloating, gas, and discomfort along with changes in the consistency of stool. This condition is heterogeneous, exhibiting variability in the symptoms reported within and between males and females.

What are the symptoms of IBS?

I ndividuals suffering from IBS will experience symptoms like belly discomfort, pain, diarrhea, constipation. However, these symptoms tend to change over some time. It can either be cured by treatment or may get severe over time, depending on the individual’s condition. Some common irritable bowel syndrome symptoms are listed below-

- Abdominal pains and cramps usually in the lower abdomen after taking meals

- Bloating of abdomen

- Increased gas

- Passing whitish mucus through the stool

- Constipation

- Harder or looser stool than usual

- Sudden urge to go to the washroom

- Food intolerance

- Weight loss and loss of appetite

Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms in females

Most of the symptoms of IBS in females are similar to males. Sometimes the symptoms tend to worsen during the time of menstruation. Women often experience worsening diarrhea just before menstrual periods. Bloating is a common symptom of IBS. Females with IBS are more likely to experience more bloating during their menstrual cycle than those women without IBS. However, menopausal women experience fewer symptoms than those women who are menstruating. Some females reported that their symptoms increased during pregnancy.

Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms in males

Researchers suggest due to hormonal differences, the male gut is less sensitive to signs of IBS than females. Males do experience problems with sexual intimacy just like females. They face difficulty in fulfilling their work and most likely suffer from depression. However, many think males simply avoid symptoms of IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms in infants

If anyone or both the parents are suffering from this disorder, children are at higher risk. Both boys and girls are equally affected. They face symptoms like, belly pain that can persist for more than 3 months, mucus seen in the stool, loss of appetite, bloating, and gas.

Are you looking for a gastroenterologist? No worries we got you covered! Book an appointment with Dr. Nivedita Pandey, one of the best gastro doctors in Delhi. Can simply go for a gastroenterologist live chat session with her. She is there to solve all your tummy problems with compassionate care.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) causes

Researchers are not aware of the exact cause of IBS. There are several factors like alteration in the gastrointestinal tract, food intolerance, hypersensitivity to pain. These factors are believed to be the causes of IBS. Let’s discuss some common causes of IBS-

- Brain-gut dysfunction- When there is a miscommunication between the nerves of the brain and gut, there are chances to develop IBS.

- Dysmotility- When individuals suffer from the abnormal movement of food in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Bacterial infection in the gastrointestinal tract.

- Overgrowth of small intestinal bacteria- An increase in number or change in the type of bacteria can cause IBS.

- Genetic influences- Researchers say that genes can make some people develop irritable bowel syndrome.

Mental disorders- Depression, stress, anxiety can be causes of IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms treatment

When it comes to nonsurgical treatment, changing lifestyle and diet is the primary treatment for IBS. Some of the lifestyle changes are-

- Exercise regularly

- Avoid drinking alcohol and smoking

- Sleep properly

- Get involved in stress management and relaxation techniques

- Practice mindful training

- Avoid taking caffeine

- Walk regularly and practice yoga

- Go for psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy

- Drink enough water and fluids

- Avoid taking foods that trigger your symptoms, look for foods with low-fat content, intake cooked vegetables other than cabbage, cauliflower, and broccoli which might cause bloating of the abdomen.

- For those who are lactose intolerant try to avoid dairy products that can trigger your symptoms.

- Enjoy eating chicken and fish

In case lifestyle and dietary changes do not provide relief to your symptoms, the individual should immediately seek urgent medical attention by consulting an online doctor chat or simply get in touch with the best gastroenterologist in Jammu. Most cases of IBP can be treated by nonsurgical measures. But if the symptoms get more severe, the patient might have to undergo surgery.

Irritable bowel syndrome risk factors

IBS can affect both females and males of all ages. However, it is more likely to affect individuals during their teens to adulthood. Researchers have studied that genes play a vital role in the development of IBS. Records show that more females are affected than males. The reason can be, males do not reach out for help to a specialist, and females experience hormonal changes during their menstrual cycle.

On the other hand, irritable bowel syndrome health risks can be mental illness, stress, depression, and traumatic events in their lives like sexual abuse. These conditions during irritable bowel syndrome can be cured by providing stress management and behavioral therapy to the patients to decrease the symptoms.

Only a small number of people have severe cases of irritable bowel syndrome. Severe symptoms can be treated with medication and therapies. Most patients can control their symptoms by changing their lifestyle and diet. These individuals come under the category of mild cases of irritable bowel syndrome. On the other hand, some individuals might have extremely serious symptoms like bloody diarrhea, shortness of breath, palpitation, swelling of the tummy. These individuals are considered the worst cases of irritable bowel syndrome. Later in their lives, they might be diagnosed with colon cancer.

Irritable bowel syndrome case study

A 43-year-old woman with a history of recurrent abdominal pain for 25 years, loose stool, fecal urgency. In the last 1-2 years, her symptoms have worsened and she experienced severe abdomen pain, fecal urgency, and inconsistency along with 6 to 8 times loose bowel movements per day. She is not exposed to alcohol. Her symptoms started deteriorating in recent years with the increase in stress in her personal and professional life. Due to her improper bowel movements, she had to quit her job which requires a lot of traveling and her body is not permitting to do that. There is no family history of irritable bowel syndrome or colon cancer. Physical examinations and laboratory test reports showed no signs of weight loss, no blood in stool, CPC and laboratory negative for celiac serologies, colonoscopy with biopsy was negative, and fecal protection was negative. Previous treatment of this patient included a low-FODMAP diet with mild improvement in symptoms. The patient wants to resolve physical urgency and inconsistency and at the same time hopes for a solution to her other symptoms.

Irritable bowel syndrome case definition

This particular case of a 43-year-old woman suffers from symptoms like abdominal pain, fecal urgency, inconsistency, and loose bowel movements. From the patient’s history, one of the renowned gastroenterologists in Delhi was able to conclude that it is a functional gastrointestinal disorder, called irritable bowel syndrome.

Irritable bowel syndrome case report

Diagnosis- The 43-year-old woman is suffering from irritable bowel syndrome. It is a digestive system disorder and is concerned with abnormal bowel movements, and abdomen pain.

Signs and symptoms- The signs and symptoms shown by this patient are recurrent abdominal pain, fecal inconsistency, loose stools for 6-8 times a day, fecal urgency and her symptoms have worsened in the last few years, with an increase in stress in her professional and personal life.

Treatment- Firstly, based on the patient’s history, the best gastroenterologist in Delhi and her team suggested going for therapeutic sessions like CBT (Cognitive-behavioral therapy). The next important thing they paid attention to is diet. The patient was asked to continue taking a low-FODMAP diet, but at the same time consulting a dietician is recommended, to make sure she is getting her daily nutrition requirements.

When it comes to pharmacological management, such patients with severe symptoms should consider taking therapies of rifaximin or eluxadoline. Lastly, the doctor made sure the patient is aware that her symptoms might be minimized with a better lifestyle and medication, but it’s not realistic to completely resolve the symptoms.