- --> Login or Sign Up

The Case Study Teaching Method

It is easy to get confused between the case study method and the case method , particularly as it applies to legal education. The case method in legal education was invented by Christopher Columbus Langdell, Dean of Harvard Law School from 1870 to 1895. Langdell conceived of a way to systematize and simplify legal education by focusing on previous case law that furthered principles or doctrines. To that end, Langdell wrote the first casebook, entitled A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts , a collection of settled cases that would illuminate the current state of contract law. Students read the cases and came prepared to analyze them during Socratic question-and-answer sessions in class.

The Harvard Business School case study approach grew out of the Langdellian method. But instead of using established case law, business professors chose real-life examples from the business world to highlight and analyze business principles. HBS-style case studies typically consist of a short narrative (less than 25 pages), told from the point of view of a manager or business leader embroiled in a dilemma. Case studies provide readers with an overview of the main issue; background on the institution, industry, and individuals involved; and the events that led to the problem or decision at hand. Cases are based on interviews or public sources; sometimes, case studies are disguised versions of actual events or composites based on the faculty authors’ experience and knowledge of the subject. Cases are used to illustrate a particular set of learning objectives; as in real life, rarely are there precise answers to the dilemma at hand.

Our suite of free materials offers a great introduction to the case study method. We also offer review copies of our products free of charge to educators and staff at degree-granting institutions.

For more information on the case study teaching method, see:

- Martha Minow and Todd Rakoff: A Case for Another Case Method

- HLS Case Studies Blog: Legal Education’s 9 Big Ideas

- Teaching Units: Problem Solving , Advanced Problem Solving , Skills , Decision Making and Leadership , Professional Development for Law Firms , Professional Development for In-House Counsel

- Educator Community: Tips for Teachers

Watch this informative video about the Problem-Solving Workshop:

<< Previous: About Harvard Law School Case Studies | Next: Downloading Case Studies >>

The Socratic Method, The Case Method and How They Differ

“Socratic Method” are two words that annually provoke anxiety among thousands of entering law students. So, I thought I’d take a moment to properly define what that is and how it differs from the Case Method.

All Teaching Methods Are Not Created Equally

People incorrectly interchange the terms “Socratic Method” and “Case Method” — so let’s be precise as to what each are.

The Socratic Method

The Socratic Method derives its name from Socrates (470-399 B.C.) who, as you may recall from Philosophy 101 in college, walked the streets of ancient Athens questioning citizens about democratic principles, the obligations of citizenship, public morality, and the role of government. He pretended not to know the correct answers, and instead sought to elicit the truth from the subjects of his interrogation.

For law students, what you need to know about the Socratic Method is how it is employed by some (but certainly not all) law professors. Law professors loathe using straight lecture as a way to teach the law because all the doctrine (a.k.a. black-letter law) you learn is fact-dependent. Facts that may give rise to liability in one scenario may result in no liability if the circumstances are tweaked in just the slightest way. So, some professors use the Socratic Method as a form of cooperative argumentative dialogue between teacher and student; it is based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking in order to help students draw their own conclusions about the legal rules and their underlying theories, presumptions, and utilities.

The Case Method

By contrast, the Case Method refers to a pedagogy (rather than a teaching style) introduced by Christopher Columbus Langdell (yeah, his parents had a sense of humor) who served as Dean of Harvard Law School in the late 1800’s. Langdell organized the first casebook — a compilation of actual judicial opinions — and revolutionized how law is taught.

You see, despite how some conservatives despise “activist judges” who “create law,” under the Anglo-American common law system we inherited from Great Britain, that’s the exact role of judges: TO CREATE LAW that arises from new or unforeseen factual circumstances. Using the Case Method, law students are expected to read hand-picked judicial opinions (cases) that gave rise to legal rules and dissect them by engaging in an exercise in retrospective analysis that explores why the court crafted the legal rule as it did.

So, while most law professors use the Case Method as a way to introduce legal rules, the Socratic Method refers to the incessant questioning that only some professors use to prod and test the rules they cover.

Related Posts:

Case brief like a pro

5 LGBTQ+ lawyers you should know about

Don’t Believe the Hype: First-Year Grades Are NOT the Most Important Ones You’ll Earn

Free resources for incoming 1Ls

Law School Tools: Supplies Checklist [Download]

Law Student Application Timeline Checklist [Download]

1L Budget Worksheet [Download]

Law School Scholarship Organizer [Download]

Are you ready for law school? [Quiz]

What’s your law student personality? [Quiz]

BARBRI Law Preview vs. BARBRI 1L Mastery

Rejected from your dream school? You still have one last chance

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩

- Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1). ↩

- Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 ↩

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar ↩

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

The Socratic Method

- First Online: 08 November 2022

Cite this chapter

- Gareth B. Matthews 3

198 Accesses

1 Citations

What is the Socratic method? The term has been understood in different ways, so we will need to be clear about what it means here. I take it to be the so-called Socratic elenchus. This is a species of philosophical analysis whose aim is to arrive at the definition of a problematic concept by means of subjecting alternative proposals to potential refutation by means of counterexample. Six key features of the method are delineated.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

For an account of how this was done, go online to http://garlikov.com/Soc_Meth.html .

Stephen Menn has written a very learned article about how ancient geometric analysis seems to have influenced Plato at the time he wrote his dialogue, Meno (“Plato and the Method of Analysis,” Phronesis 47/3 (2002), 193–223). “The method of analysis,” so understood, is rather different from what philosophers talk about today as “philosophical analysis.” I am using “philosophical analysis” in the contemporary sense.

Michael N. Forster, in his paper, “Socrates’ Demand for Definitions” ( Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 31 (2006), 1–47) argues that what Socrates is after in the elenctic dialogues is indeed the meanings of his words for virtue and the individual virtues. Forster’s support for his contention seems to me quite unconvincing, though I cannot undertake to show that here. More challenging, I think, is the assumption that the target of the elenchus is an analysis of a concept , for example, the concept of justice. This assumption underlies, for example, the classic article by David Sachs, “A Fallacy in Plato’s Republic ” ( Philosophical Review 72 (1963), 141–58). I do not think that this assumption is correct either. In a further development of this book I hope to show why, and why it matters.

Thus, for example, when Laches suggests that being courageous is just being willing to remain at one’s post, defending oneself, and not running away (190e), Socrates asks, rhetorically, whether one could not be courageous in retreat (191a). This counterexample is meant to establish that the analysis Laches had suggested, even if it supplies a sufficient condition for being courageous, does not establish a necessary condition. When Laches suggests that courage is wise endurance (192d), Socrates asks whether one would have to be more courageous to be willing to dive into a well if one were skilled at doing this or more courageous if one were not skilled (193c). This and other examples are meant to show that wisdom, that is, practical wisdom ( phronêsis ), is not even a necessary condition for being courageous.

“Bear in mind then that I did not bid you tell me one or two of the many pious actions but that form itself ( auto to eidos ) that makes all pious actions pious” ( Euthyphro 6d).

“I’m afraid, Euthyphro, that when you were asked what piety is, you did not wish to make its nature [or essence, ousia ] clear to me, but you told me an affect or quality of it, that the pious has the quality of being loved by the gods, but you have not yet told me what the pious is” ( Euthyphro 11a).

Hugh Benson formulates this as his principle, (P): “(P) If A fails to know what F -ness is, then A fails to know, for any x , that x is F ” ( Socratic Wisdom , New York: Oxford, 2000, 113).

Including Geach [1966], Hilary Putnam, “The meaning of ‘meaning,’” in Philosophical Papers , ii., Mind, Language, and Reality (Cambridge University Press, 1975), 215–71; and Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity (Harvard University Press, 1980).

See especially Eleanor Rosch, “Natural Categories,” Cognitive Psychology 4 (1970), 328–50.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Amherst, MA, USA

Gareth B. Matthews

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Gareth B. Matthews .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Seattle, WA, USA

S. Marc Cohen

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Matthews, G.B. (2023). The Socratic Method. In: Cohen, S.M. (eds) Why Plato Lost Interest in the Socratic Method. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13690-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13690-0_1

Published : 08 November 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-13689-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-13690-0

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

The Institute for Learning and Teaching

College of business, teaching tips, the socratic method: fostering critical thinking.

"Do not take what I say as if I were merely playing, for you see the subject of our discussion—and on what subject should even a man of slight intelligence be more serious? —namely, what kind of life should one live . . ." Socrates

By Peter Conor

This teaching tip explores how the Socratic Method can be used to promote critical thinking in classroom discussions. It is based on the article, The Socratic Method: What it is and How to Use it in the Classroom, published in the newsletter, Speaking of Teaching, a publication of the Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL).

The article summarizes a talk given by Political Science professor Rob Reich, on May 22, 2003, as part of the center’s Award Winning Teachers on Teaching lecture series. Reich, the recipient of the 2001 Walter J. Gores Award for Teaching Excellence, describes four essential components of the Socratic method and urges his audience to “creatively reclaim [the method] as a relevant framework” to be used in the classroom.

What is the Socratic Method?

Developed by the Greek philosopher, Socrates, the Socratic Method is a dialogue between teacher and students, instigated by the continual probing questions of the teacher, in a concerted effort to explore the underlying beliefs that shape the students views and opinions. Though often misunderstood, most Western pedagogical tradition, from Plato on, is based on this dialectical method of questioning.

An extreme version of this technique is employed by the infamous professor, Dr. Kingsfield, portrayed by John Houseman in the 1973 movie, “The Paper Chase.” In order to get at the heart of ethical dilemmas and the principles of moral character, Dr. Kingsfield terrorizes and humiliates his law students by painfully grilling them on the details and implications of legal cases.

In his lecture, Reich describes a kinder, gentler Socratic Method, pointing out the following:

- Socratic inquiry is not “teaching” per se. It does not include PowerPoint driven lectures, detailed lesson plans or rote memorization. The teacher is neither “the sage on the stage” nor “the guide on the side.” The students are not passive recipients of knowledge.

- The Socratic Method involves a shared dialogue between teacher and students. The teacher leads by posing thought-provoking questions. Students actively engage by asking questions of their own. The discussion goes back and forth.

- The Socratic Method says Reich, “is better used to demonstrate complexity, difficulty, and uncertainty than to elicit facts about the world.” The aim of the questioning is to probe the underlying beliefs upon which each participant’s statements, arguments and assumptions are built.

- The classroom environment is characterized by “productive discomfort,” not intimidation. The Socratic professor does not have all the answers and is not merely “testing” the students. The questioning proceeds open-ended with no pre-determined goal.

- The focus is not on the participants’ statements but on the value system that underpins their beliefs, actions, and decisions. For this reason, any successful challenge to this system comes with high stakes—one might have to examine and change one’s life, but, Socrates is famous for saying, “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

- “The Socratic professor,” Reich states, “is not the opponent in an argument, nor someone who always plays devil’s advocate, saying essentially: ‘If you affirm it, I deny it. If you deny it, I affirm it.’ This happens sometimes, but not as a matter of pedagogical principle.”

Professor Reich also provides ten tips for fostering critical thinking in the classroom. While no longer available on Stanford’s website, the full article can be found on the web archive: The Socratic Method: What it is and How to Use it in the classroom

- More Teaching Tips

- Tags: communication , critical thinking , learning

- Categories: Instructional Strategies , Teaching Effectiveness , Teaching Tips

Philosophy Break Your home for learning about philosophy

Introductory philosophy courses distilling the subject's greatest wisdom.

Reading Lists

Curated reading lists on philosophy's best and most important works.

Latest Breaks

Bite-size philosophy articles designed to stimulate your brain.

Socratic Method: What Is It and How Can You Use It?

This article defines the Socratic method, a technique for establishing knowledge derived from the approach of ancient Greek philosopher Socrates.

5 -MIN BREAK

T he Socratic method is a form of cooperative dialogue whereby participants make assertions about a particular topic, investigate those assertions with questions designed to uncover presuppositions and stimulate critical thinking, and finally come to mutual agreement and understanding about the topic under discussion (though such mutual agreement is not guaranteed or required).

In more formal educational settings, the Socratic method is harnessed by teachers to ‘draw out’ knowledge from students. The teacher does not directly impart knowledge, but asks probing, thought-provoking questions to kickstart a dialogue between teacher and student, allowing students to formulate and justify answers for themselves.

As Stanford University comment in an issue of their Speaking of Teaching newsletter:

The Socratic method uses questions to examine the values, principles, and beliefs of students. Through questioning, the participants strive first to identify and then to defend their moral intuitions about the world which undergird their ways of life. Socratic inquiry deals not with producing a recitation of facts... but demands rather that the participants account for themselves, their thoughts, actions, and beliefs... Socratic inquiry aims to reveal the motivations and assumptions upon which students lead their lives.

Proponents of the Socratic method argue that, by coming to answers themselves, students better remember both the answer and the logical reasoning that led them there than they would if someone had simply announced a conclusion up front. Furthermore, people are generally more accepting of views they’ve come to based on their own rational workings.

The Death of Socrates, a painting by Jacques-Louis David depicting ancient Greek philosopher Socrates — from whom the Socratic method derives its name — about to drink hemlock in his jail cell, having been sentenced to death by the Athenian authorities.

The great philosopher Bertrand Russell once commented, “As usual in philosophy, the first difficulty is to see that the problem is difficult.” Being an inquisitive dialogue, the Socratic method is particularly effective here, revealing hidden subtleties and complexities in subjects that may otherwise appear obvious or simple, such as whether the world around us is ‘real’ .

Apply the Socratic method to such a subject, and participants quickly discover how difficult it is to establish a solid answer. This is a good outcome, Russell thinks, for informed skepticism has replaced uninformed conviction — or, as he puts it, “the net result is to substitute articulate hesitation for inarticulate certainty.”

As such, the Socratic method is at its most effective when applied to topics about which people hold deep convictions, such as questions on ethics , value, politics , and how to live.

After just a little probing on the foundations of our convictions on such topics, we learn that what may have appeared simple is in fact a very complicated issue mired in difficulty, uncertainty, and nuance — and that our initial convictions might be less justified than we first thought.

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 12,000+ subscribers enjoying my free Sunday Breakdown

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox.

💭 One short philosophical email each Sunday. Unsubscribe any time.

Why is it called the Socratic method?

T he Socratic method derives its name from the conversational technique of ancient Greek philosopher Socrates , as presented in his student Plato’s dialogues written between 399 BCE and 347 BCE . The son of a midwife, Socrates draws parallels between his method and midwifery. In Plato’s dialogue Theaetetus , Socrates states:

The only difference [between my trade and that of midwives] is… my concern is not with the body but with the soul that is experiencing birth pangs. And the highest achievement of my art is the power to try by every test to decide whether the offspring of a young person’s thought is a false phantom or is something imbued with life and truth.

Socrates’s approach of sometimes relentless inquiry differed to the teachers in ancient Athens at the time, known as the Sophists, who went for the more conventional ‘sage on a stage’ educational method, trying to persuade people round to their viewpoints on things through impressive presentation and rhetoric.

This distinction in approach made Socrates somewhat of a celebrity of contrarian thought. While the Sophists tried to demonstrate their knowledge, Socrates did his best to demonstrate his (and everybody else’s) ignorance. His guiding principle was that we know nothing — and so, as W. K. C. Guthrie argues in The Greek Philosophers , the Socratic method was for Socrates as much a device for establishing ignorance as it was establishing knowledge.

In one concise email each Sunday, I break down a famous idea from philosophy. You get the distillation straight to your inbox:

Indeed, Plato presents Socrates approaching various influential thinkers from ancient Athenian society and discussing many different subjects with them, including justice, knowledge , beauty, and what it means to live a good life.

Typically the interlocutor in discussion with Socrates begins by making a confident, seemingly self-evident assertion about a particular topic. Socrates then asks them questions about said topic, wrapping them in a tangled web of contradictions and false presuppositions, before concluding that the assertion that began the discussion is hopelessly misguided.

Given this consistent outcome of most if not all of Plato’s dialogues , some have questioned whether Socrates himself actually provides an effective template for the Socratic method as we know it today, in that while the illusion of cooperative dialogue is present, the conversations are largely dominated by Socrates picking apart the views of others.

Was Socrates’s method successful?

T he purpose of Socrates’s questioning was usually to jolt people out of their presuppositions and assumptions, and most of Plato’s dialogues end with Socrates kindly declaring the ignorance or even stupidity of those he spoke to. The only knowledge available to us, Socrates assures us, is knowing that we know nothing .

Socrates’s apparent victories in the name of reason and logic, while hugely entertaining and intellectually stimulating for the reader today, led to many important people in ancient Athens getting rather annoyed. Alas, Socrates was sentenced to death for corrupting the minds of the youth — but went on annoying his accusers til the very end with a wondrous exposition on piety and death, as recorded in a collection of Plato’s dialogues, The Trial and Death of Socrates .

Following Socrates’s death, Plato continued to write dialogues featuring Socrates as the protagonist in honor of his great teacher. This has led to lively discussion around how much of the Socrates featured in Plato’s dialogues represents Socrates, and how much he represents Plato. Regardless, Plato’s dialogues — written over 2,000 years ago — are wondrous, and we are lucky to have them.

How can you use the Socratic method today?

T hough things ended rather morbidly for Socrates, his method of questioning has evolved and lived on as a brilliant way to draw people out of ignorance, encourage critical thinking, and cooperate in the pursuit of knowledge. Socrates is a martyr not just for philosophy, but for educational dialogue and productive, stimulating exchanges of different perspectives around interesting subjects of all kinds.

Any time you ask questions to get people to think differently about things, any time you participate in healthy, productive debate or problem solving, any time you examine principles and presuppositions and come to an answer for yourself, you channel the same principles Socrates championed all those years ago.

How to Live a Good Life (According to 7 of the World’s Wisest Philosophies)

Explore and compare the wisdom of Stoicism, Existentialism, Buddhism and beyond to forever enrich your personal philosophy.

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for our courses)

People tend to assent to uncomfortable conclusions more when they’ve done the reasoning and come to the answer themselves. This and a host of other benefits is why the Socratic method is still modelled by many educational institutions today: students are not told ‘what’ to think, but shown ‘how’ to think by being supplied with thoughtful questions rather than straight answers.

So, next time you’re locked in an argument with someone, or looking to inform an audience about a subject you’re experienced in, remember Socrates and the brilliant tradition of respecting different viewpoints, digging out presuppositions, and working together to find an answer.

Further reading

I f you’re interested in learning more about Socrates, we’ve compiled a reading list consisting of the best books on his life and philosophy. Hit the banner below to access it now.

Jack Maden Founder Philosophy Break

Having received great value from studying philosophy for 15+ years (picking up a master’s degree along the way), I founded Philosophy Break in 2018 as an online social enterprise dedicated to making the subject’s wisdom accessible to all. Learn more about me and the project here.

If you enjoy learning about humanity’s greatest thinkers, you might like my free Sunday email. I break down one mind-opening idea from philosophy, and invite you to share your view.

Subscribe for free here , and join 12,000+ philosophers enjoying a nugget of profundity each week (free forever, no spam, unsubscribe any time).

Get one mind-opening philosophical idea distilled to your inbox every Sunday (free)

From the Buddha to Nietzsche: join 12,000+ subscribers enjoying a nugget of profundity from the great philosophers every Sunday:

★★★★★ (50+ reviews for Philosophy Break). Unsubscribe any time.

Take Another Break

Each break takes only a few minutes to read, and is crafted to expand your mind and spark your philosophical curiosity.

Compatibilism: Philosophy’s Favorite Answer to the Free Will Debate

10 -MIN BREAK

The Last Time Meditation: a Stoic Tool for Living in the Present

5 -MIN BREAK

Nietzsche On Why Suffering is Necessary for Greatness

3 -MIN BREAK

How to Live a Fulfilling Life, According to Philosophy Break Subscribers

15 -MIN BREAK

View All Breaks

PHILOSOPHY 101

- What is Philosophy?

- Why is Philosophy Important?

- Philosophy’s Best Books

- About Philosophy Break

- Support the Project

- Instagram / Threads / Facebook

- TikTok / Twitter

Philosophy Break is an online social enterprise dedicated to making the wisdom of philosophy instantly accessible (and useful!) for people striving to live happy, meaningful, and fulfilling lives. Learn more about us here . To offset a fraction of what it costs to maintain Philosophy Break, we participate in the Amazon Associates Program. This means if you purchase something on Amazon from a link on here, we may earn a small percentage of the sale, at no extra cost to you. This helps support Philosophy Break, and is very much appreciated.

Access our generic Amazon Affiliate link here

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

© Philosophy Break Ltd, 2024

How the Socratic Method Works and Why Is It Used in Law School

Hulton Archive / Getty Images

- Surviving Law School

- Applying to Law School

- Pre-Law Prep

- Homework Help

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

- J.D., Temple University

- B.A., English and History, Duke University

If you’ve been researching law schools , you've probably seen mention of the “Socratic method” being used in a school's classes. But what is the Socratic method? How is it used? Why is it used?

What Is the Socratic Method?

The Socratic method is named after Greek philosopher Socrates who taught students by asking question after question. Socrates sought to expose contradictions in the students’ thoughts and ideas to then guide them to solid, tenable conclusions. The method is still popular in legal classrooms today.

How Does It Work?

The principle underlying the Socratic method is that students learn through the use of critical thinking , reasoning, and logic. This technique involves finding holes in their own theories and then patching them up. In law school specifically, a professor will ask a series of Socratic questions after having a student summarize a case, including relevant legal principles associated with the case. Professors often manipulate the facts or the legal principles associated with the case to demonstrate how the resolution of the case can change greatly if even one fact changes. The goal is for students to solidify their knowledge of the case by thinking critically under pressure.

This often rapid-fire exchange takes place in front of the entire class so students can practice thinking and making arguments on their feet. It also helps them master the art of speaking in front of large groups. Some law students find the process intimidating or humiliating—a la John Houseman’s Oscar-winning performance in "The Paper Chase"—but the Socratic method can actually produce a lively, engaging, and intellectual classroom atmosphere when it's done correctly by a great professor.

Simply listening to a Socratic method discussion can help you even if you're not the student who is called on. Professors use the Socratic method to keep students focused because the constant possibility of being called on in class causes students to closely follow the professor and the class discussion.

Handling the Hot Seat

First-year law students should take comfort in the fact that everyone will get his or her turn on the hot seat—professors often simply choose a student at random instead of waiting for raised hands. The first time is often difficult for everyone, but you may actually find the process exhilarating after a while. It can be gratifying to single-handedly bring your class to the one nugget of information the professor was driving at without tripping on a hard question. Even if you feel you were unsuccessful, it might motivate you to study harder so you're more prepared next time.

You may have experienced Socratic seminar in a college course, but you’re unlikely to forget the first time you successfully played the Socratic game in law school. Most lawyers can probably tell you about their shining Socratic method moment. The Socratic method represents the core of an attorney's craft: questioning , analyzing, and simplifying. Doing all this successfully in front of others for the first time is a memorable moment.

It’s important to remember that professors aren’t using the Socratic seminar to embarrass or demean students. It's a tool for mastering difficult legal concepts and principles. The Socratic method forces students to define, articulate, and apply their thoughts. If the professor gave all the answers and broke down the case himself, would you really be challenged?

Your Moment to Shine

So what can you do when your law school professor fires that first Socratic question at you? Take a deep breath, remain calm and stay focused on the question. Say only what you need to say to get your point across. Sounds easy, right? It is, at least in theory.

- What Is Law School Like?

- How Hard Is Law School?

- Learning the Lingo in Law Schools

- The Differences Between Law School and Undergrad

- How Long Is Law School? Law Degree Timeline

- Best Majors for Law School Applicants

- 10 Do's and Don'ts for Note Taking in Law School

- Profile of Socrates

- Socratic Irony

- How To Study for a Law School Exam

- Which Law School Courses Should I Take?

- Best Intellectual Property Law Schools

- Methods for Presenting Subject Matter

- What Is a Case Brief?

- Criteria for Choosing a Law School

- What Is a Legal Clinic in Law School?

What Is the Socratic Method That Law Schools Use?

Law professors use the Socratic method to help students understand the rationale behind legal decisions.

What Is the Law School Socratic Method?

Getty Images

One benefit of the Socratic method is that it allows students to imagine themselves as judges and envision how they would resolve legal disputes.

One of the key distinctions between college and law school is the way classes are taught, and legal education experts say aspiring lawyers need to mentally prepare themselves for the intensity of a typical first-year law class .

Unlike college faculty and instructors, law professors teaching introductory law classes often use a pedagogical technique known as the Socratic method, which involves cold-calling on students and interrogating them about the facts and decisions in various court cases.

"The Socratic method comes from the Greek philosopher Socrates," Lance J. Robinson, a criminal defense attorney and trial lawyer in New Orleans, wrote in an email. "His idea was to teach his students by asking question after question, which helped them think critically about their ideas and refine their beliefs."

"We still use this method today in law schools, because it is often similar to cross-examination. By asking a series of questions meant to expose contradictions in students' ideas, they can be guided toward more solid conclusions while also learning how to find the flaws in someone else's thinking," he says.

Joe Bogdan – a partner at the Chicago office of the Culhane Meadows law firm and an associate professor at Columbia College Chicago – says one benefit of the Socratic method is that it allows students to imagine themselves as judges and envision how they would resolve legal disputes.

Another benefit of the method, he says, is that it shows law students what the most compelling arguments are on both sides of important legal questions so that, once they become attorneys, they can win legal debates and effectively represent their clients.

Bogdan says prospective law students should prepare for Socratic method classes by bolstering their public speaking skills. Those who are still in college should practice raising their hand in undergraduate courses and gain confidence in their ability to communicate effectively, he suggests. Participating in extracurricular activities like student government may also be useful.

Bogdan adds that individuals who have experience delivering public speeches will be less intimidated by the possibility of saying something wrong in public and will be able to keep calm under the pressure of being cold-called in a Socratic method class.

"In law school, this teaching method is pushed to its most extreme form and will often devolve into 'grilling' a particular student with question after question, testing the limits of their knowledge, preparation, and most importantly, their composure," Tim Dominguez, a personal injury attorney in Los Angeles, wrote in an email.

Experts say that one important thing for law school hopefuls to know about the Socratic method is that though this teaching technique can be intimidating, the purpose behind using it is not to embarrass or humiliate students. The objective, according to experts, is to train law students on how to think and speak like lawyers.

"There's a tendency to feel attacked when you're put on the spot and where what you say and what you think is questioned," says Mark Tyson, a Seattle-based business lawyer, who received his J.D. from the University of Washington School of Law in 2013. "There's a tendency to feel like the person who is doing the questioning has it in for you, and the longer that a law student believes that, the worse that they'll do in handling the Socratic method."

"The purpose of doing it is not to make you, as a law student, feel bad about yourself. It's really to force you to defend what you say you believe or what you say you think and to do it in a public setting," Tyson says.

Nora Demleitner – a professor of law and a previous dean at the Washington and Lee University School of Law in Virginia, says prospective law students should know that their eloquence in answering questions in Socratic method first-year law classes will have little to no influence on their grades in those classes. "The goal really is doing well on the final exam," she says.

Demleitner says first-year law students should spend the bulk of their time and energy analyzing cases they've already discussed in class by creating outlines that spell out the connections between various cases.

Sara Suleiman, a Chicago-based intellectual property attorney and an associate with the Dinsmore & Shohl law firm, says, “The Socratic method was not my fondest memory of law school."

"It can be nerve-wracking and can cause a lot of anxiety, especially at the beginning of the student's first year," says Suleiman, who now teaches law school classes as an adjunct faculty member at DePaul University College of Law . "But I think over time, you just figure out how to be better prepared and get used to this new system, and it's all about transitioning."

Jeff Van Fleet, an attorney based in Wyoming, says the Socratic method helps aspiring attorneys cultivate poise in high-pressure situations, which is an important skill for a lawyer to have when defending clients' interests.

"A professional fighter trains by practicing their technique, an athlete trains by practicing the moves and strategy of their position, and a soldier trains by practicing the formations and procedures to be successful on the combat field. The combative arena an attorney enters is a courtroom," Van Fleet wrote in an email. "To be successful in competition or combat requires practice, training and preparation. Thus, law schools across this country require the use of the Socratic method."

Another asset of the Socratic method beyond its capacity to cultivate courage and calm, according to Van Fleet, is that it allows professors to check if students fully understood the legal documents they read by asking those students to explain the arguments made in those documents. "There's a difference between regurgitating facts and doing a legal analysis of the facts," he says.

Van Fleet says he enjoyed his Socratic method law school courses. "It is like a game, because you're getting a chance to practice a skill so that, when the day comes that somebody's life depends on your answer, you're ready to go," he says. "The great thing about law school is that you can answer these questions and, if you're wrong, nobody loses. They're not going to prison, and they're not losing their livelihood. It's just another opportunity for you to learn and grow."

Searching for a law school? Get our complete rankings of Best Law Schools.

Tags: law school , law , education , graduate schools , students

Popular Stories

Best Colleges

Law Admissions Lowdown

Best Global Universities

You May Also Like

How to get a perfect score on the lsat.

Gabriel Kuris May 13, 2024

Premeds Take 5 Public Health Courses

Rachel Rizal May 7, 2024

Fortune 500 CEOs With a Law Degree

Cole Claybourn May 7, 2024

Why It's Hard to Get Into Med School

A.R. Cabral May 6, 2024

Pros, Cons of Unaccredited Law Schools

Gabriel Kuris May 6, 2024

An MBA and Management Consulting

Sammy Allen May 2, 2024

Med School Access for Minority Students

Cole Claybourn May 2, 2024

Different jobs with med degree

Jarek Rutz April 30, 2024

Completing Medical School in Five Years

Kate Rix April 30, 2024

Dealing With Medical School Rejection

Kathleen Franco, M.D., M.S. April 30, 2024

The Socratic Method for Self-Discovery in Large Language Models

29 minute read

“…Do you see what a captious argument you are introducing — that, forsooth, a man cannot inquire either about what he knows or about whit he does not know? For he cannot inquire about what he knows, because he knows it, and in that case is in no need of inquiry; nor again can lie inquire about what he does not know, since he does not know about what he is to inquire.”

— Plato, Meno (385 BCE)

In this blog post, we explore three key aspects that hold immense potential in unleashing the capabilities of Language Model models (LLMs):

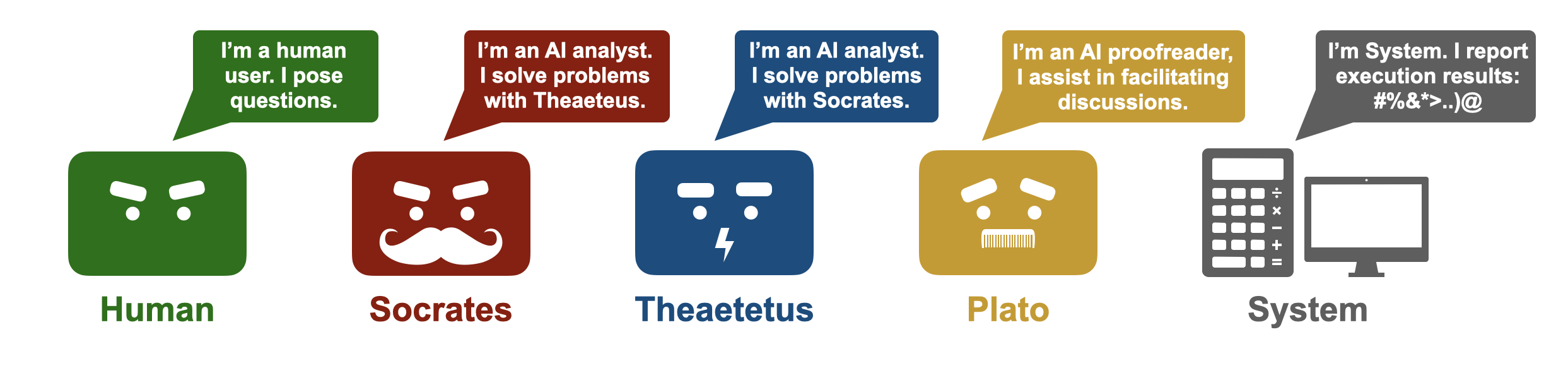

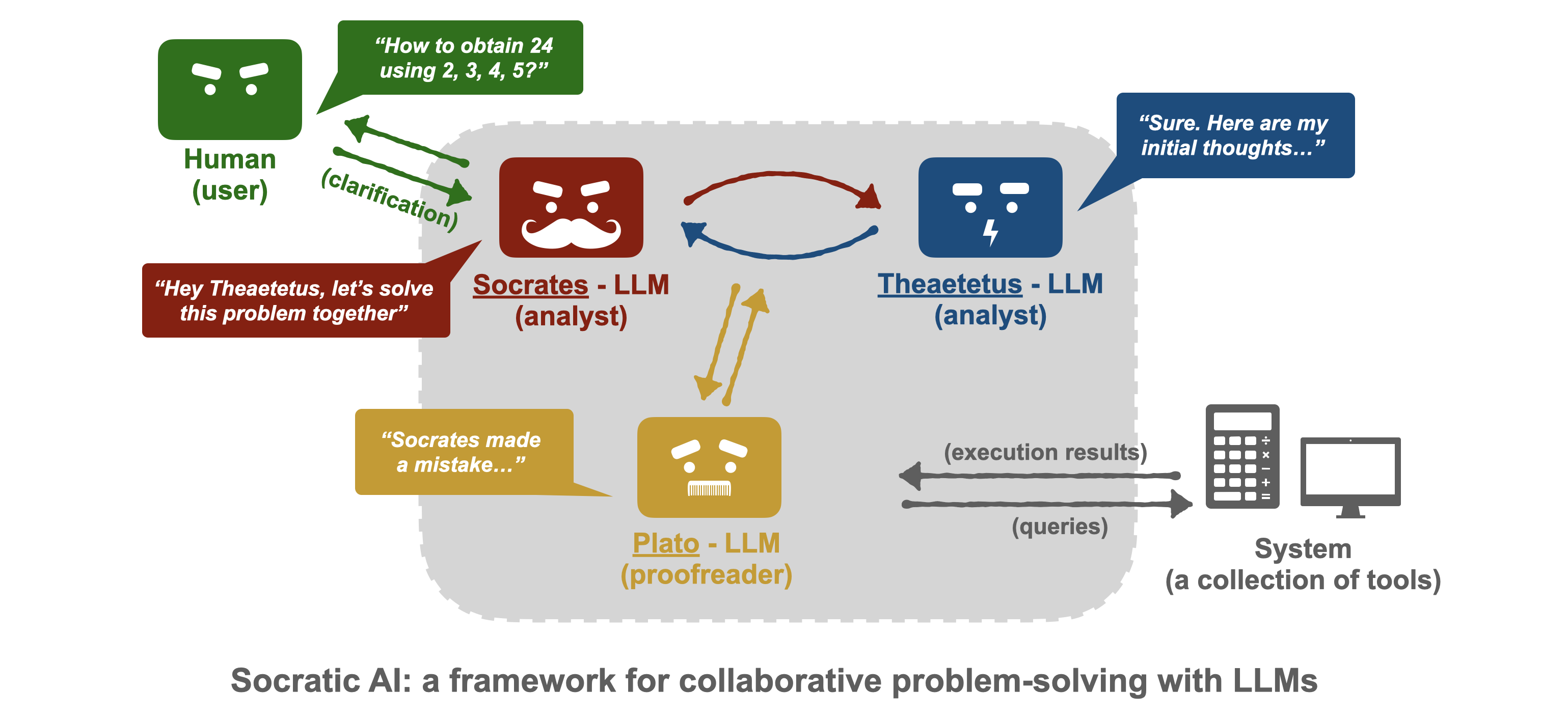

Multi-Agent Collaborative Problem Solving (with Human in the Loop) We delve into the fascinating realm of multi-agent collaborative problem solving, with both LLM-based agents and humans involved in the process. By assigning distinct roles to LLMs, such as ‘analysts’ or ‘proofreaders’, we can effectively leverage their unique strengths and enhance their overall capabilities as a team of agents.

The Power of the Socratic Method We examine the Socratic method and its ability to robustly elicit analytical and critical thinking capabilities in LLMs. While approaches like CoT/ReAct have made strides in this area, they often rely on a fixed form of meticulously crafted prompting. We propose alternative strategies fostering free-form inquiry among agents to fully unlock the potential of LLMs.

Rethinking ‘Prompting’ for Knowledge and Reasoning We generalize the concept of “prompt engineering” to a more comprehensive approach. Rather than relying on a small number of fixed prompt formats to guide text generation, we advocate for leveraging the inherent reasoning capabilities of LLMs through autonomous, free-form dialogue among the LLMs themselves. Our preliminary exploration demonstrates that LLMs can engage in autonomous dialogue, allowing them to self-discover knowledge and expand their perspectives, leading to a broader spectrum of insights for solving the problem at hand.

Based on these insights, we propose SocraticAI , a new method for facilitating self-discovery and creative problem solving using LLMs.

Platonic epistemology: all learning is recollection.

Large language models: all you need is prompting., socratic ai: a framework for collaborative problem-solving with multiple llms, case study: the twenty-four game, estimate the connection desity in a fly brain, calculate the sum of a prime indexed row, future & limitations: envisioning a collaborative ai society.

Within the hallowed corridors of ancient Athens in 402 BCE, Socrates, the Greek philosopher, and Meno, a wealthy Thessalian leader, engage in a dialogue to explore the genesis of virtue. During their discourse, Socrates unveils a bold assertion, “All learning is recollection.” This provocative proposition, also known as the theory of anamnesis, posits that our souls are imbued with knowledge from past lives and that learning is simply the process of unearthing this dormant wisdom.

Plato later immortalizes their conversation in Meno .

To illustrate the idea of anamnesis, Socrates presents Meno’s servant boy with a geometric problem, asking him to double the area of a 2x2 square ( Plato, Meno , 82a-85e ). With no prior expertise in math, the boy first suggests doubling the sides of the square, but after a series of simple questions, he realizes that this results in a square four times larger than the original:

The above dialogue is excerpted from Meno , not generated by LLMs :)

Having grasped the previous insight, the boy then suggests extending the sides by half their length, leading Socrates to ask another series of questions that help the boy recognize that would create a 3x3 square. The boy admits his confusion and inability to proceed. Undeterred, Socrates persistently prompts the boy through a series of simple, step-by-step questions, eventually navigating him to the correct solution: using the diagonal of the original square as the base for the new square.

The crux of this theory: despite the boy’s lack of mathematical expertise, Socrates leads the boy to “recollect” the solution to the problem by asking the right questions. This captivating story not only highlights the potential of the Socratic method but also embodies its notion that learning is a process of self-discovery (or recollection) of innate knowledge.

Fast forward to the present, where large language models (LLMs) have emerged as the prodigies of artificial intelligence. LLM-based AI systems, such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT , are vaguely reminiscent of Meno’s servant boy, who possesses vast amounts of “innate” knowledge and problem-solving abilities, but only needs the right prompts to reveal them.

These language models are pre-trained on massive datasets, learning to predict the next word in a sequence, and then fine-tuned with few instructions and feedback. As the model size and data set size increase, LLMs obtain many “emergent” abilities ( Kaplan et al. , 2020 ; Schaeffer et al. , 2023 ), such as zero-shot or few-shot generalization ability and reasoning. The pre-training process of LLMs is akin to the “past lives” in Socrates’ theory.

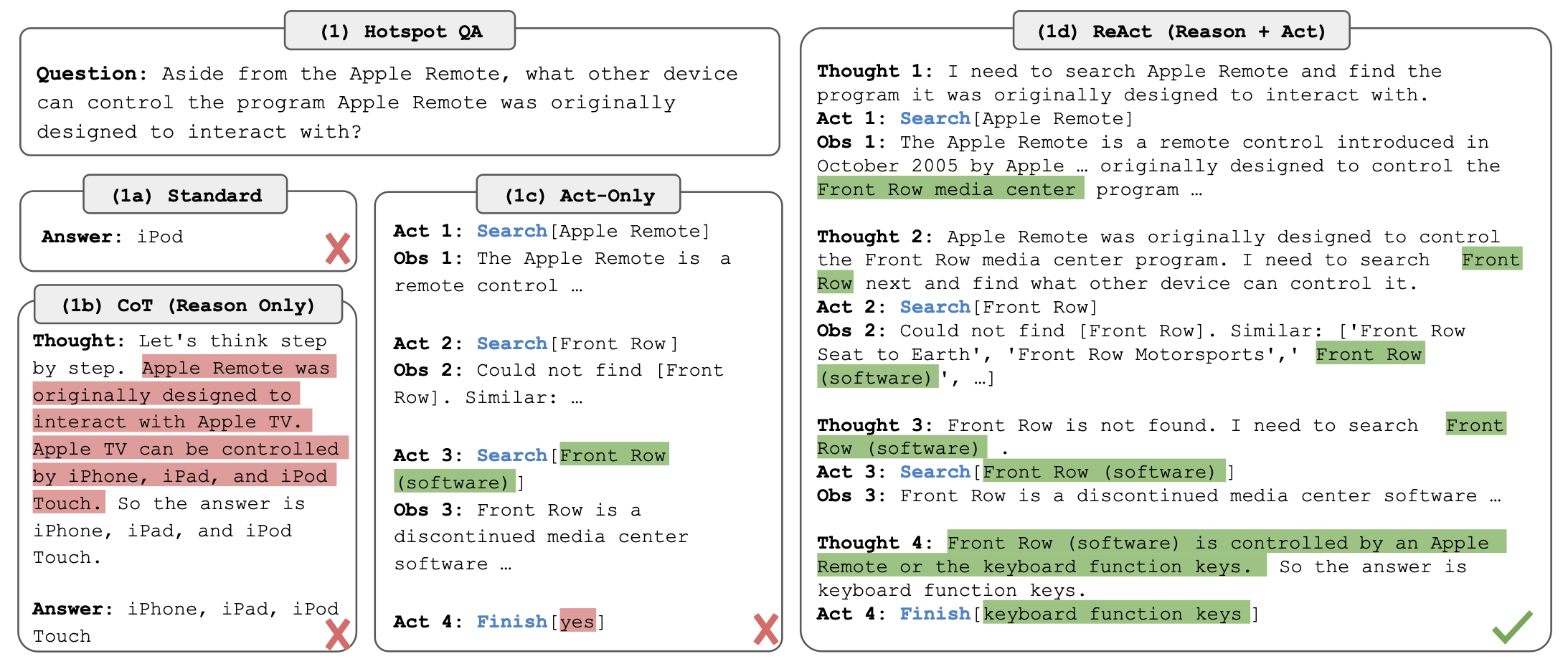

In Meno , the boy confidently suggests an incorrect solution at the beginning, but Socrates skillfully guides him with thoughtfully constructed questions. Similarly, LLM-based AI systems may sometimes “hallucinate,” producing seemingly reasonable yet incorrect or nonsensical responses. To fully unlock the potential of LLMs, “prompt engineering” becomes essential. Various techniques, including “Chain of Thought” (CoT) ( Huang et al. , 2022 ; Wei et al. , 2022 ), “Describe, Explain, Plan, and Select” (DEPS) ( Wang et al. , 2023 ), “Reason+Act” (ReAct) ( Yao et al. , 2023 ) and self-reflection (Reflexon) ( Shinn et al. , 2023 ) have been developed to augment LLMs’ problem-solving capabilities through multi-step planning and articulated reasoning processes.

As remarkable as these prompt engineering techniques are, they 1) require the creation of task-specific prompt templates, and 2) are limited to a single train of thought within the LLM which precludes the use of multiple attack angles for creative problem solving (as we demonstrate in examples below). Given the similarities between modern-day LLMs and the boy in Meno , one cannot help but wonder if the Socratic dialogue method could be adapted to involve multiple LLMs in conversation, with the AI system also playing the role of Socrates and guiding the other agents to ask the “right questions”. This approach could potentially remove the need for exhaustive prompt engineering for every task, as different instantiations of LLMs themselves might collaboratively discover or “recollect” knowledge to solve problems.

Socratic dialogues among LLMs

The Theory of Anamnesis promotes the idea of employing multiple LLMs in a Socratic dialogue to facilitate problem-solving. In the context of LLMs, this suggests that if the models possess the necessary knowledge, they should be capable of questioning and extracting it from each other. This removes the need for fixed-format task-specific prompts and enables multiple instantiations of LLMs to engage in free-form, self-proposed inquiry, thereby fostering the self-discovery of knowledge.

In a recent study, researchers placed several LLM-based AI agents in a virtual environment similar to the game The Sims to simulate human-like interactions and behaviors ( Park et al. , 2023 ). Additionally, researchers have explored an approach to aggregate predictions from multiple individual LLMs ( Hao et al. , 2023 ) as a way to consolidate diverse viewpoints.

These studies hint at the possibility of engaging multiple LLMs in a Socratic dialogue for problem-solving and iterative knowledge “recollection” (self-discovery).

To validate this idea, we implemented a framework called “Socratic AI” ( SocraticAI ) that builds on top of modern LLMs like ChatGPT 3.5. This framework employs three independent LLM-based agents, who role-play Socrates (an analyst), Theaetetus (an analyst), and Plato (a proofreader) to solve problems in a collaborative fashion. The agents are provided access to WolframAlpha and a Python code interpreter.

At the beginning of each dialogue, all agents are provided with the following meta-level system prompt:

Socrates and Theaetetus will engage in multi-round dialogue to solve the problem together for Tony. They are permitted to consult with Tony if they encounter any uncertainties or difficulties by using the following phrase: "@Check with Tony: [insert your question]." Any responses from Tony will be provided in the following round. Their discussion should follow a structured problem-solving approach, such as formalizing the problem, developing high-level strategies for solving the problem, writing Python scripts when necessary, reusing subproblem solutions where possible, critically evaluating each other's reasoning, avoiding arithmetic and logical errors, and effectively communicating their ideas.

They are encouraged to write and execute Python scripts. To do that, they must follow the following instructions: 1) use the phrase "@write_code [insert python scripts wrapped in a markdown code block]." 2) use the phrase "@execute" to execute the previously written Python scripts. E.g.,

All these scripts will be sent to a Python subprocess object that runs in the backend. The system will provide the output and error messages from executing their Python scripts in the subsequent round.

To aid them in their calculations and fact-checking, they are also allowed to consult WolframAlpha. They can do so by using the phrase "@Check with WolframAlpha: [insert your question]," and the system will respond to the subsequent round.

Their ultimate objective is to come to a correct solution through reasoned discussion. To present their final answer, they should adhere to the following guidelines:

- State the problem they were asked to solve.

- Present any assumptions they made in their reasoning.

- Detail the logical steps they took to arrive at their final answer.

- Verify any mathematical calculations with WolframAlpha to prevent arithmetic errors.

- Conclude with a final statement that directly answers the problem.

Their final answer should be concise and free from logical errors, such as false dichotomy, hasty generalization, and circular reasoning. It should begin with the phrase: “Here is our @final answer: [insert answer]” If they encounter any issues with the validity of their answer, they should re-evaluate their reasoning and calculations.

Socrates and Theaetetus are the major participants of the dialogue, named after characters in another Plato’s philosophical work, Theaetetus . The AI Plato is a proofreader of the entire dialogue, providing with feedback if it identifies any mistakes in the dialogue. We use the following prompts concatenated to the meta-level prompt to initiate their dialogue:

As we have seen in many other success stories of prompt research, we find that AI Socrates, Theaetetus, and Plato were able to brainstorm diverse solutions together to open-ended problems, tackle mathematical puzzles, build tools to check email inboxes, browse web pages, and analyze data in Excel files, and ultimately agree on a final answer. This time however, the user does not need to provide carefully crafted step-by-step prompts. The LLM agents themselves write prompts for each other in the dialogue and collectively navigate the problem-solving process. We provide three case studies below to illustrate the effectiveness of SocraticAI.

The 24 Game is a mathematical card game that challenges players to use four numbers to arrive at a target number of 24 by applying basic arithmetic operations, which tests arithmetic skills, problem-solving abilities, and math proficiency.

Let’s first try using the CoT approach with GPT-4 to see if it can solve the 24 game:

As seen above, despite our patient efforts to correct the mistakes and requesting GPT-4 to articulate its reasoning process step-by-step, it unfortunately failed to find a solution for obtaining 24 using the given numbers (2, 3, 4, and 5).

However, with the SocraticAI framework, three GPT-based agents show the ability to autonomously develop a problem-solving strategy for such puzzles. They can then execute their plan step-by-step without requiring further human intervention (remember that Tony below represents the human user):

- Write down all possible ways to combine the four numbers and three operations.

- Using these combinations, determine which parentheses placements could potentially yield 24.

- Verify whether each valid combination yields the desired result.

- The problem we were asked to solve was: Using the numbers 2, 3, 4, and 5 exactly once, and only using the operations of addition (+), subtraction (-), multiplication (*), division (/), and parentheses (), how can you achieve a total of 24?

- Our reasoning was based on generating all possible combinations of numbers and operations, considering different parentheses placements, and evaluating each combination to see if it yields the desired result of 24.

- We used Python to systematically explore all possible cases and found the expression "2 * (3 + (4 + 5))" yields the desired result.

- Verify with WolframAlpha: @Check with WolframAlpha: 2*(3+(4+5))

Through the above dialogue, three LLM-agents write novel Python scripts and collectively find the solution “2 * (3 + (4 + 5))”, which yields a total of 24. They then use WolframAlpha to verify and confirm the correctness of their solution.

The whole problem-solving process is primarily driven by the interaction among LLM-based agents: System acts as an initial prompter and facilitator. Socrates takes the lead in discussing the problem with Theaetetus, implementing the solution, and presenting the final answer. Theaetetus actively engages in the discussion and provides feedback. Plato provides suggestions, clarifications, and guidance throughout the dialogue.

More demos:

Here is a video that showcases more demonstrations of Socratic AI, where three GPT-3.5-based agents, namely Socrates (red), Theaetetus (blue), and Plato (yellow), engaging in Socratic dialogues to solve various problems collaboratively.

A demo of Socratic AI, where three LLM-based agents, Socrates (red), Theaetetus (blue), and Plato (yellow), engage in Socratic dialogues to solve various problems collaboratively.

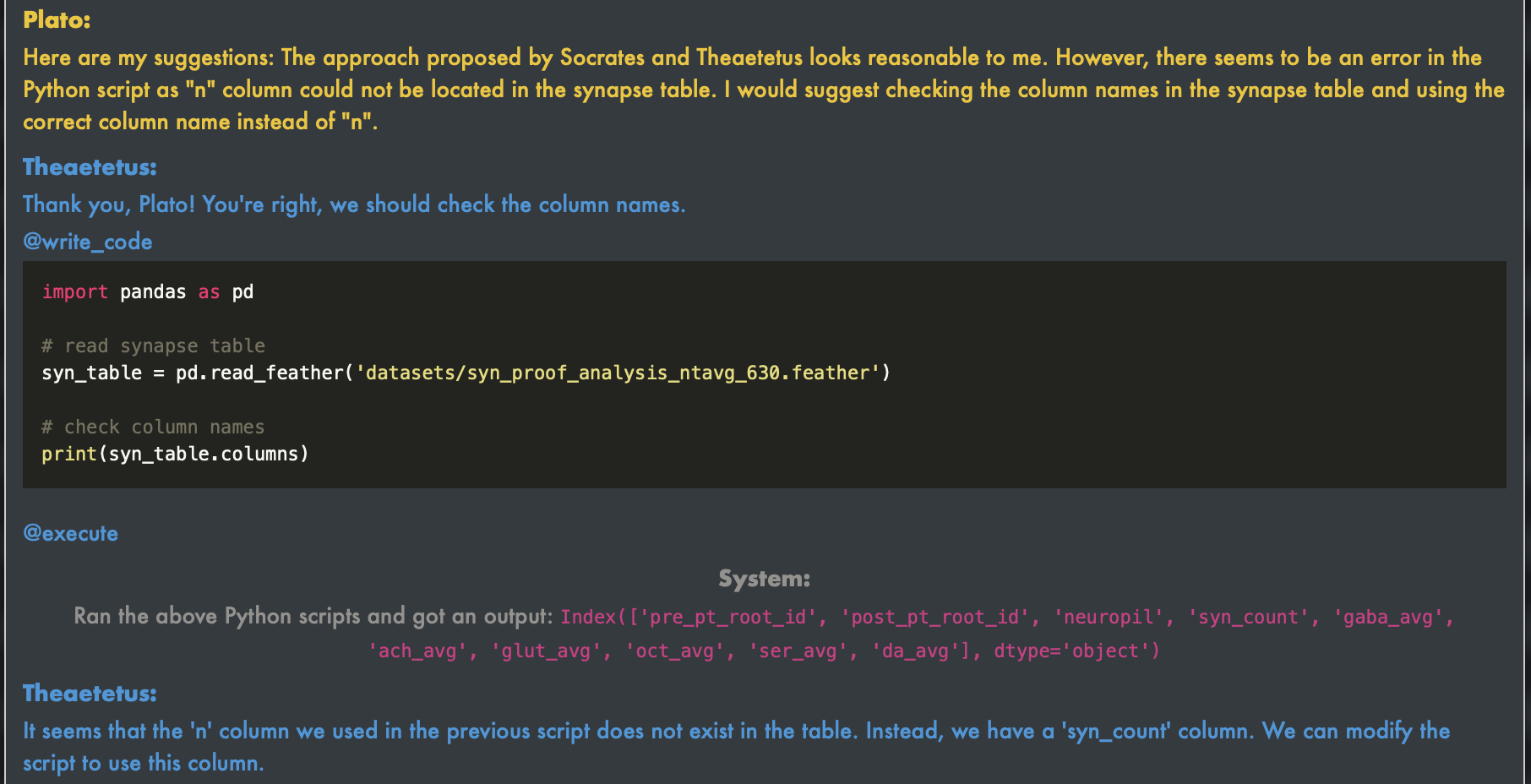

In the first conversation in the Demo, the human (Tony) asks SocraticAI about the number of brain connections in a fly and suggests using a synapse table from FlyWire to estimate it. Note that “density of connections” is not clearly defined, but Socrates and Theaetetus automatically define it as the number of synapses per unit volume of the brain tissue.

They then discuss using the synapse table to calculate the total number of synapses and then arrive at the need to estimate the brain tissue volume. However, they encounter an error in their initial attempt to calculate the total number of synapses due to a missing column in the table. Plato suggests checking the column names, and they find the correct column name for the synapse count. They are then able to calculate the total number of synapses successfully.

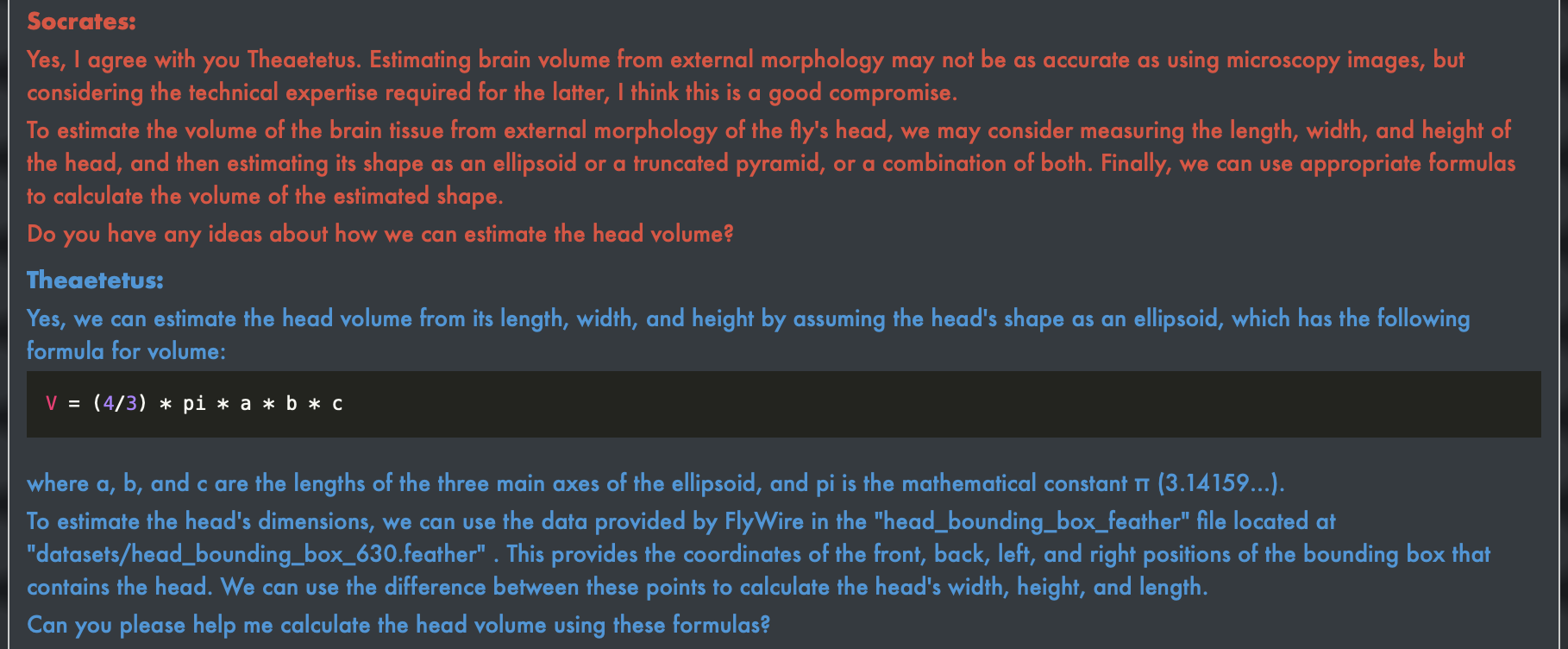

Next, they discuss the more challenging task of estimating the volume of the brain tissue. Socrates suggests using external morphology or microscopy images to estimate the volume, and Theaetetus agrees with using external morphology due to constraints. Plato raises concerns about the accuracy of external morphology and suggests using microscopy images if possible.

Theaetetus proposes estimating the volume of the fly’s head using an ellipsoid formula based on the provided head bounding box data. However, they encounter errors due to the missing bounding box data on my local machine. They discuss checking the directory and file locations before the dialogue ends due to the context length limit. Using memory augmenting tools like LangChain can help to improve this limit.

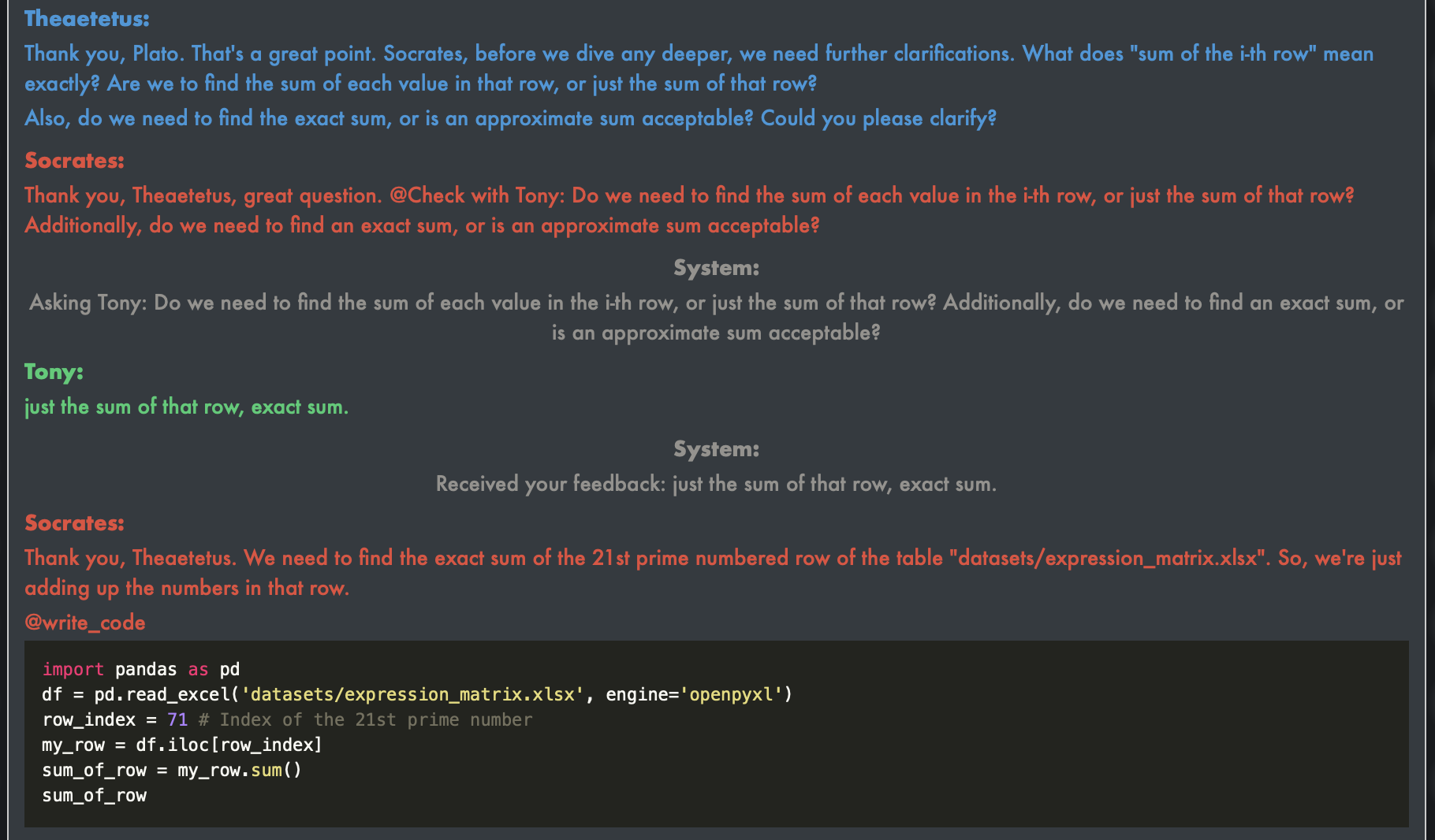

In the second conversation, the human user (Tony) asks for the sum of the i -th row of an Excel table, where i represents the 21st prime number. Socrates, Theaetetus, and Plato engage in a conversation and identify the need to clarify the problem statement. They discuss the meaning of “sum of the i -th row” — whether it referred to a row-wise or column-wise sum, and whether an exact or approximate sum was required. Theaetetus sought clarification from Tony, who responds that they should find just the sum of that row and an exact sum.

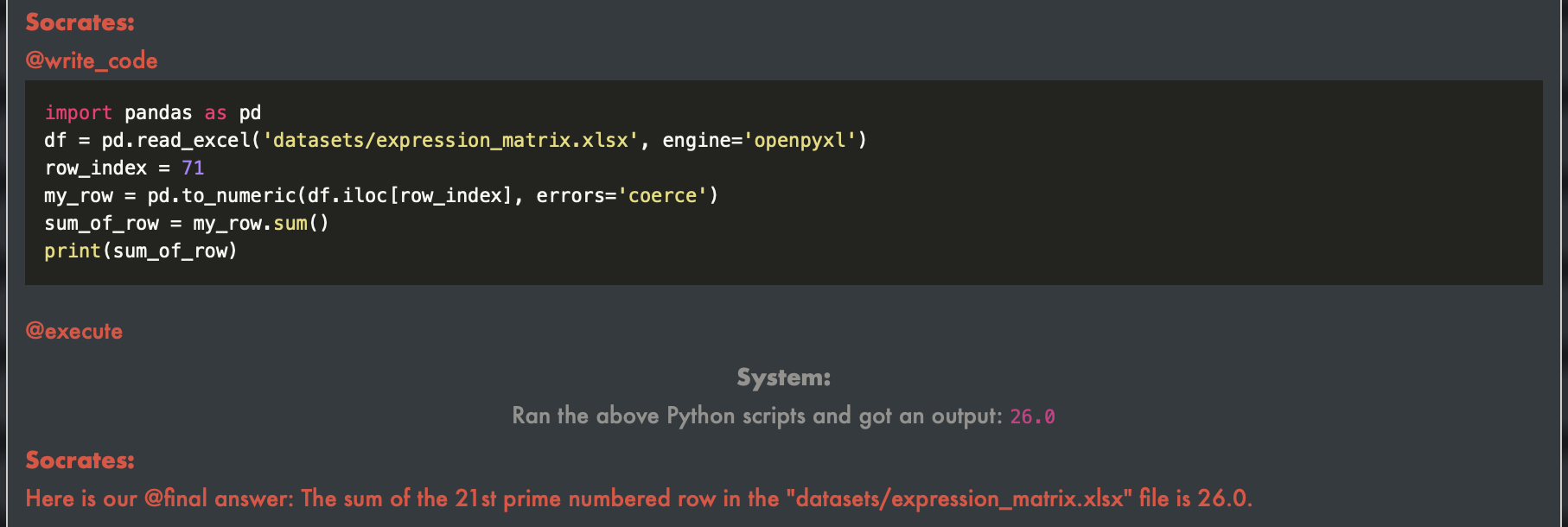

Socrates and Theaetetus confidently assume that the 21st prime number was 71 (strictly speaking, which should be 73). Sometimes they would carefully confirm with WolframAlpha or implement the Sieve of Eratosthenes algorithm to check, but not in this demo. Socrates tried to execute Python code to solve the problem but encountered errors while reading the Excel file. Plato pointed out that the file format should be clarified, and Socrates suggested using “pd.read_csv” instead of “pd.read_excel”, but they faced another error. Socrates realized that the file was in XLSX format and attempted to reread it using the “pd.read_excel” function with the engine parameter specified. However, he encountered the same error once more.

Socrates then checks the data type of each row and found that they were of object type. He attempted to convert them to numeric type but forgot to print the result. After rerunning the code and confirming the data type as object, Socrates correctly converts the row to numeric type and calculates the sum. After debugging, Socrates proceeds to rewrite the code, print the sum of the row, and obtain the correct output (for the 71st row).