Software Testing Help

How To Annotate An Article: Learn Annotation Strategies

Understand how to Annotate an Article through this tutorial. Learn efficient strategies for effective annotation using online tools, etc:

Whether you are a student or a professional, knowing how to annotate will surely be a valuable tool in your repertoire. Annotation is an active learning strategy that will help you get the most out of any text in terms of both comprehension and retention.

Learning how to annotate will give you a way to better engage with various types of complex reading material, such as articles, essays, literary texts, research papers. But what does ‘annotate’ mean, and how do you do it?

Read this tutorial to find out what annotation is, why it is useful, and how to annotate an article or a bibliography. We’ve also added some useful strategies for effective annotation.

Table of Contents:

What Does ‘Annotate’ Mean

Why is annotation useful, how do you annotate, what is an annotated bibliography, #1) using a key/legend, #2) using stationery, #3) using online tools, frequently asked questions, was this helpful, recommended reading, how to annotate an article.

To ‘annotate’ is, simply, to ‘add notes’. These could be comments, explanations, criticisms, or questions pertaining to whatever text you’re reading.

To annotate a text, you generally highlight or underline important pieces of information and make notes in the margin. You can annotate different texts.

As a student, you can annotate articles , essays , or even textbooks . Research students who compile and reference a long list of sources for their thesis will find it useful to know how to annotate a bibliography .

As a professional, knowing how to annotate will help you easily comprehend and retain any important information from reports or other official documents that you might have to read in the course of your work.

Suggested reading =>> Top 10 Essay Checker And Corrector

A well-annotated text can give you a better understanding of complex information. There are several reasons you should annotate a text.

Few of them are enlisted below:

- Annotating an article lets you become familiar with the location and organization of its content. Thus, it becomes easier and faster to find important information when reviewing .

- When you annotate a text, you clearly identify and distinguish the key points from the supporting details or evidence, which makes it easier to follow the development of ideas and arguments .

- You can also use annotations to build an organized knowledge base, by structuring or categorizing information in an easy-to-access way. Annotating is particularly handy when you need to extract important information , such as relevant quotes or statistics.

- Annotating is an excellent way of actively engaging with a text , by adding your own comments, observations, opinions, questions, associations, or any other reactions you have as you read the text.

- Annotations are especially useful when you need to work on a shared document . You can use annotations to draw your team’s attention towards certain important or interesting information, or even to initiate group discussions on a particular concept, problem, or question.

Annotating a text involves a ‘close reading’ of it. In this section, you will find some examples of annotated texts.

Example of an annotated article: Does ‘‘Science’’ Make You Moral?

Example of an annotated literary text: Annotations on a poem – The Road Not Taken

Follow these key steps when annotating any text:

Step 1: Scan

This is really a pre-reading technique.

- At first glance, make a note of the title of the text, and subheadings, if any, to identify the topic of the text.

- Analyze the source, i.e. the author or the publisher, to evaluate its reliability and usefulness.

- Look for an abstract if there is one, as well as any bold or italicized words and phrases, which might offer further clues about the text’s purpose and intended audience.

Step 2: Skim

Use this first read-through to quickly find the focus of the text, i.e. its main idea or argument. Do this by reading just the first few lines of each paragraph.

- Identify and highlight/underline the main idea.

- Write a summary (only a sentence or two) of the topic in your own words, in the margins, or up top near the title.

Step 3: Read

The second read-through of the text is a slower, more thorough reading. Now that you know what the text is about, as well as what information you can expect to encounter, you can read it more deliberately, and pay attention to details that are important and/or interesting.

- Identify and highlight/underline the supporting points or arguments in the body paragraphs, including relevant evidence or examples.

- Paraphrase and summarize key information in the margins.

- Make a note of any unfamiliar or technical vocabulary.

- Note down questions that come to your mind as you read, any confusion, or your agreement or disagreement with ideas in the text.

- Make personal notes – write your opinion, your thoughts, and reactions to the information in the text.

- Draw connections between different ideas, either within the text itself, or to ideas in other texts, or discussions.

Step 4: Outline

To really solidify your understanding of the content and organization of the text, write an outline tracking the points at which new ideas are introduced, as well as the points where these ideas are developed.

An effective outline will include:

- A summary of the text’s main idea.

- Supporting arguments/evidence.

- Opposing viewpoints (if relevant)

A Bibliography is a list of the books (or other texts) referred to, or cited, in academic texts such as essays, thesis, and research papers, and is usually included at the end of the text. It is also known as a Reference List , or a List of Works Cited , depending on the style of formatting.

The APA (American Psychological Association) and MLA (Modern Language Association) styles of formatting are most commonly used. The format may vary depending on the institution or publication, however, the same basic information is required for each individual reference or citation in a bibliography.

This includes:

- Author’s name

- Title of the text

- Date of publication

- Source of publication i.e. the journal, magazine, or website where the text is published

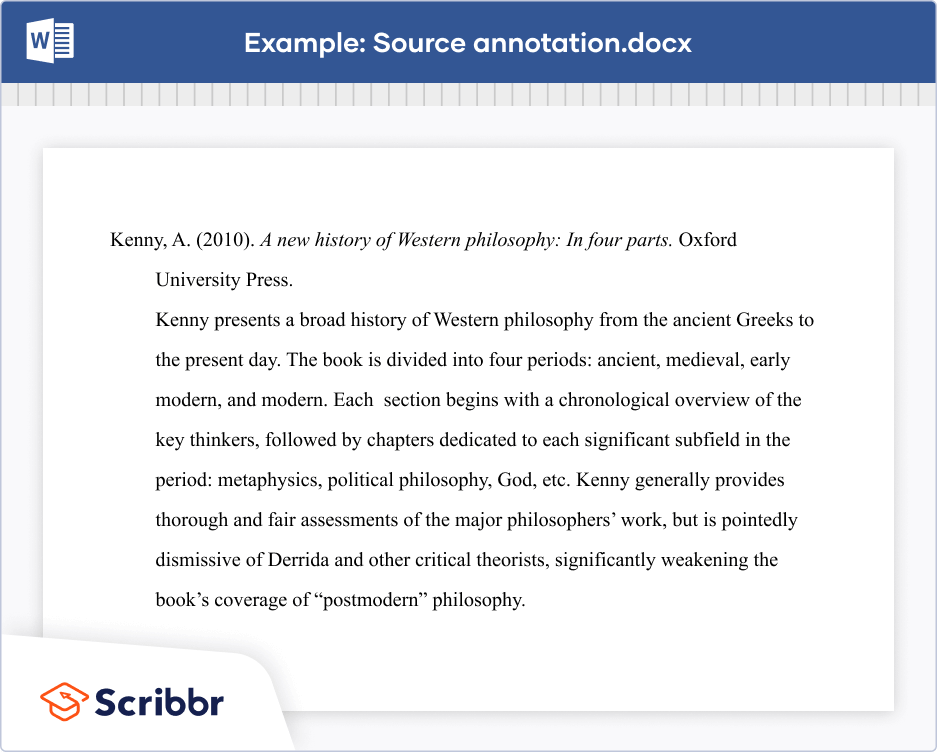

An Annotated Bibliography contains, in addition to the basic information above, a descriptive summary, as well as and an evaluation of each individual entry. The purpose of this is to inform the reader about the relevance, accuracy, and reliability of each reference or citation.

An annotated bibliography is titled ‘ Annotated Reference List ’ or ‘ Annotated List of Works Cited ’, which can be listed alphabetically by author, title, date of publication, or even by subject.

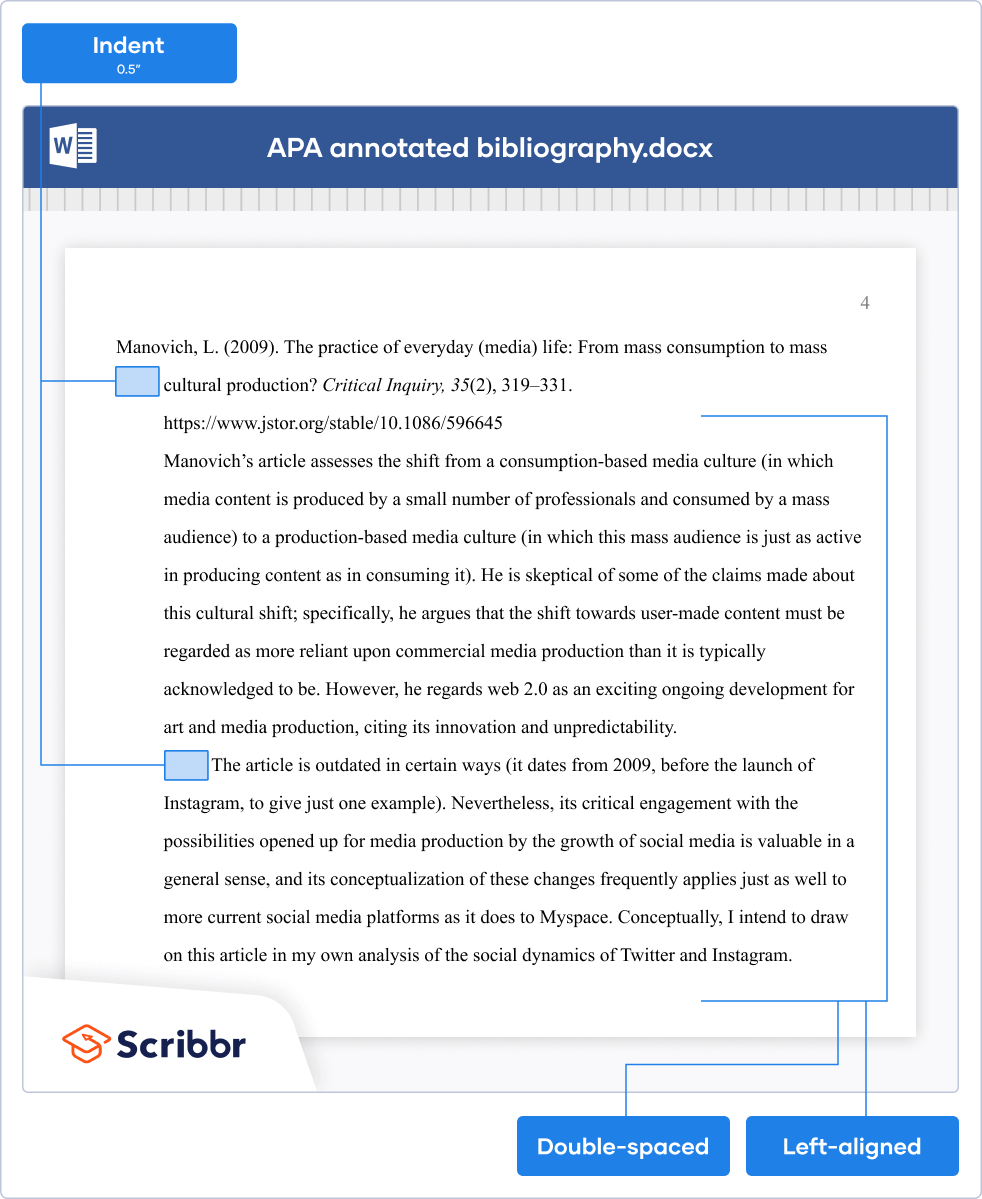

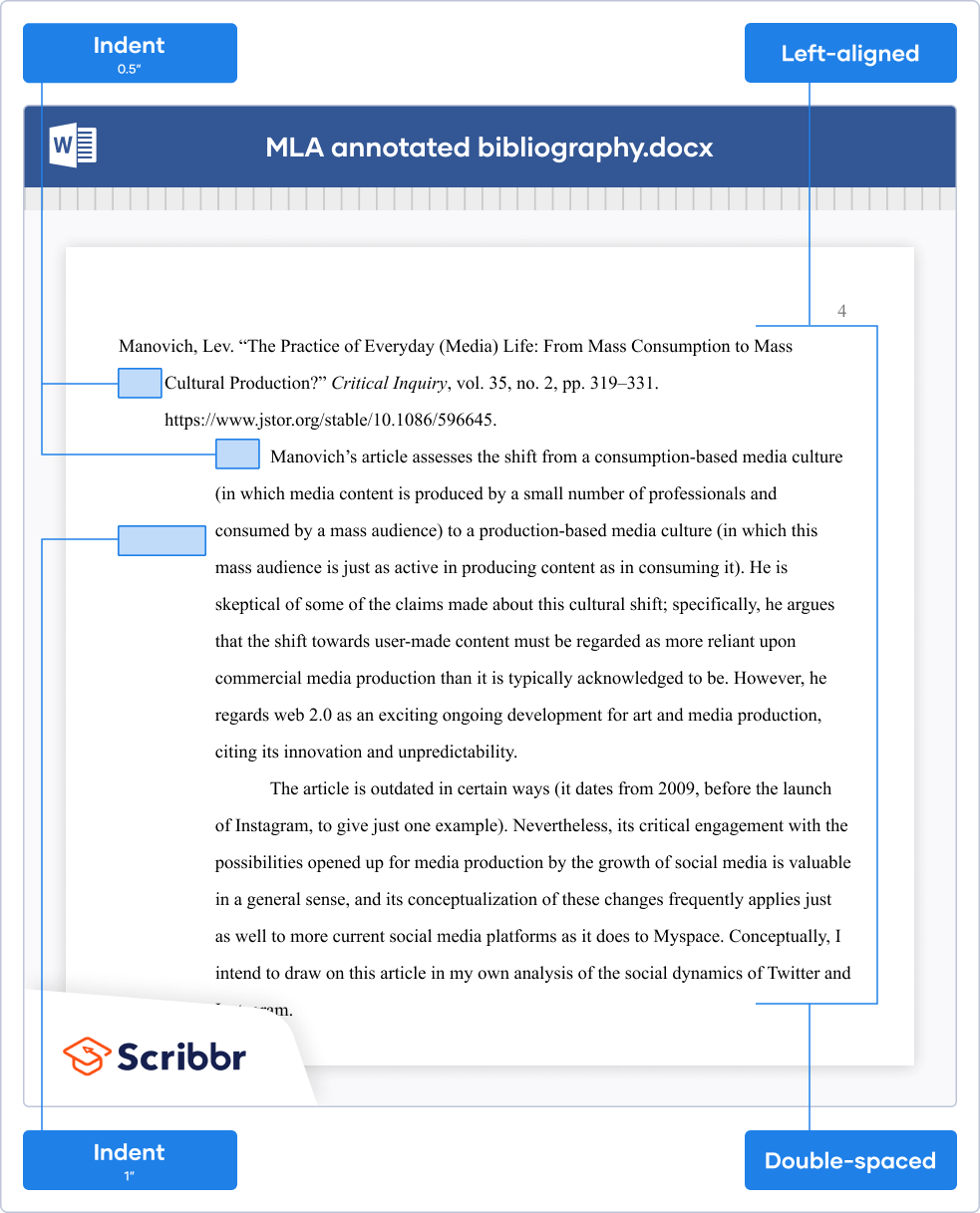

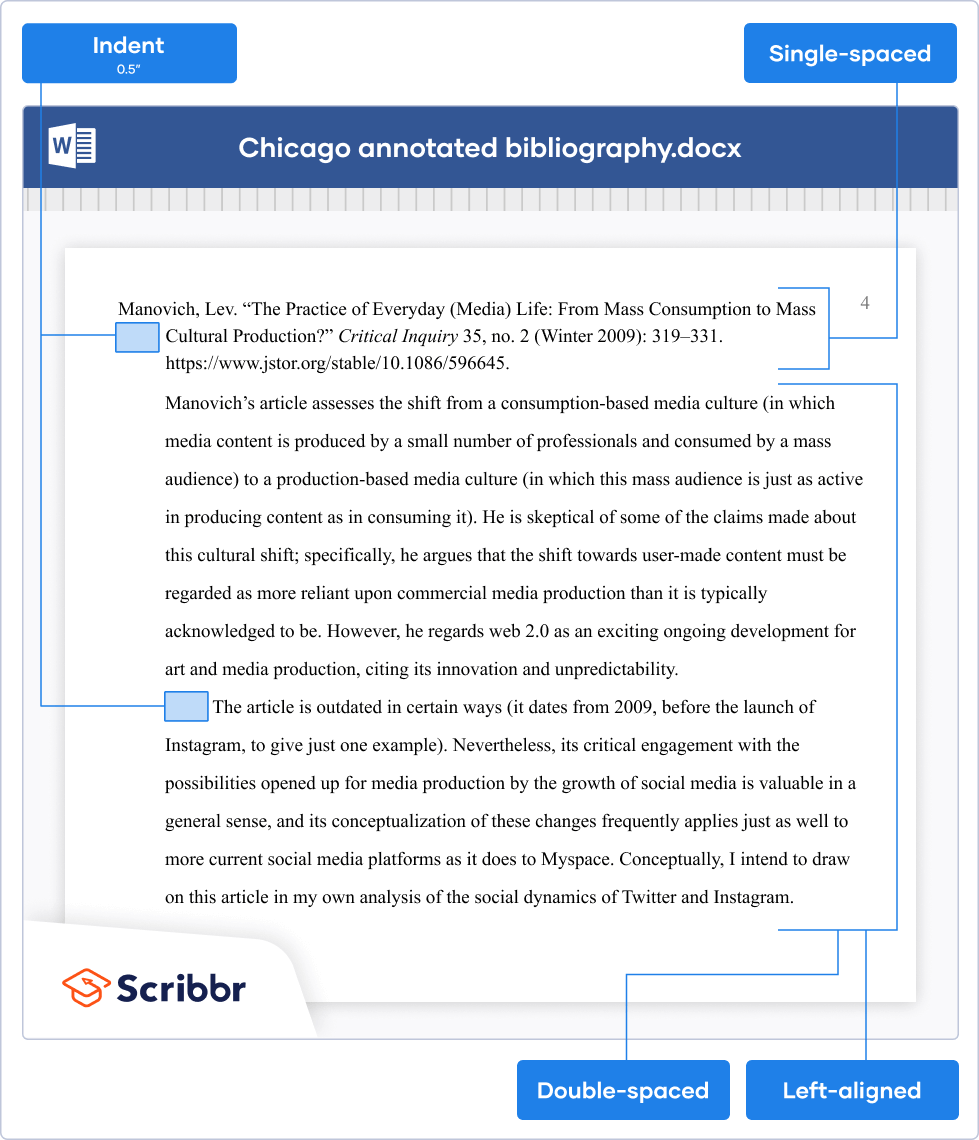

Let us see an example of an entry in an annotated bibliography, formatted in both the APA and MLA styles.

Example of an APA-style annotated bibliography:

Example of an MLA-style annotated bibliography:

Strategies For Annotation

Depending on whether you are reading printed or online text, you can either annotate by hand, using stationery and/or symbols or by using document programs.

The following strategies will help you annotate as you read:

Create a key or legend for annotating your text with different types of markings and specify what kind of information each marking indicates. This will help to easily identify and access relevant pieces of content.

For example, you can underline key points, highlight quotes or statistics, and circle unfamiliar words/phrases. You can also use punctuation – question marks for things that spark your curiosity as you read; exclamation points for something that catches your attention, or maybe surprises you; arrows that link the content to other points or ideas within the text, or outside of it.

Pens and markers are most commonly used to highlight or underline key points in the text. These are, however, the least active ways of engaging with any text, and you might end up highlighting or underlining more of the text than is necessary.

It also isn’t always possible to use pens and markers on printed text. You might have to return the book or magazine to the library. For example, you can always use post-its in such cases.

If you are using markers and/or post-its, use different colors for different types of annotations in the text. For example, use green for definitions and explanations, yellow for questions, and pink for personal notes.

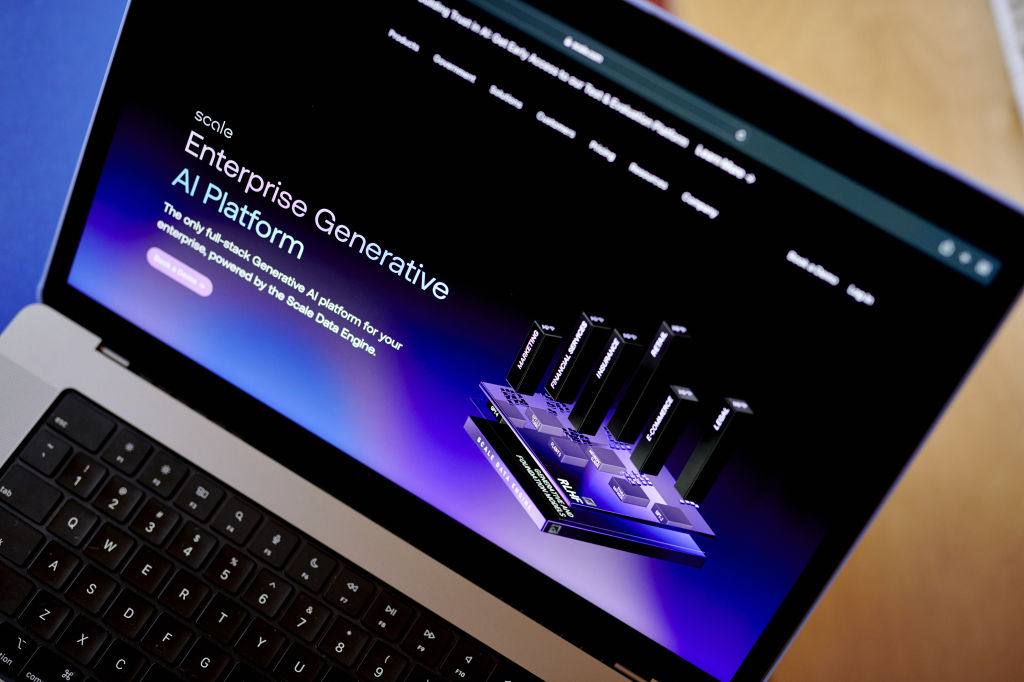

Once you know how to annotate a text, you can do this online too! There are different mobile apps and online softwares that can help you annotate digital documents such as PDFs, online articles, and web pages.

Digital annotation tools allow you to mark up online text by adding notes and comments, highlighting key information, and capturing screenshots. They also let you perform various other tasks, including draw on, bookmark, and share webpages. They are particularly useful when you need to work on shared documents with a team.

Here is a list of the most commonly used digital annotation tools:

- hypothes.is

Some of these digital annotation tools are free, such as Diigo and A.nnotate , while others like Filestage and Cronycle are paid tools. You can also download extensions that will allow you to annotate webpages, such as hypothes.is , which is a free browser extension, or Grackle , an add-on tool for Google Docs.

Recommended Reading =>> Best Punctuation Checker Online Applications

Q #1) How do you annotate step by step?

Answer: Here is how to annotate an article in three simple steps:

- First, before reading the article in full, look for some basic important information such as the title and author, subheadings if relevant. This will give you an idea as to the topic and intended audience of the article.

- Second, skim through the article to identify the main idea, along with supporting arguments or evidence.

- Third, read the article thoroughly while noting down more details such as comments, questions, and your personal responses to the article.

Q #2) What are the benefits of annotation?

- If you know how to annotate a text, you can actively engage with, and make sense of, the information presented in any text.

- Annotation familiarizes you with the organization of information, so you can follow the development of ideas in the text.

- Knowing how to annotate an article of text is helpful when you review, as you can access relevant pieces of information more easily and quickly.

- Annotating also makes it easier and more efficient to work with others on shared documents.

Q #3) What are 5 different ways to annotate?

Answer: There are many ways to annotate a text or article. Such as:

- Highlight and/or underline important information.

- Paraphrase and/or summarize key points.

- Make notes in the margin.

- Write an outline of the text.

- Use online tools to annotate web pages, online articles, and PDFs.

Q #4) What are some annotation strategies?

Answer: You can get the most out of annotating a text by adding a key or legend, which uses different markings for different types of information. You can also use pens, markers, and post-its effectively by assigning different colors to different purposes.

If you are working with online documents, you can use digital annotation softwares such as Diigo and A.nnotate , or free extensions/add-ons like hypothes.is or Grackle .

Q #5) What should you look for while annotating?

Answer: When annotating any text, look for and make note of the following:

- Key points i.e. the main or important ideas.

- Questions that occur to you as you read.

- Recurring themes or symbols.

- Quotes or statistics.

- Unfamiliar and technical concepts or terminology.

- Links to ideas in texts or related to experiences.

There are several benefits to learning how to annotate an article as you read. The more you practice, the more effective you will become at annotation, which will improve how easily and quickly you can make sense of texts that you read.

- Read the text once to gain an insight into the topic of the article, marking only essential information, such as the focus of the text and the main idea, based on the title and subheadings.

- Read the text again, highlighting or underlining as you read, to identify and summarize relevant information, such as supporting arguments or evidence.

- Make notes, add comments and questions, including personal responses to the text.

- Top 10 Essay Checker And Corrector For Online Proofreading

- Top 10 FREE Online Proofreading Tools [2024 SELECTIVE]

- Grammarly Review 2024: Comprehensive Guide & Comparison

- Top 10 Grammar Checker Platforms For A Speedy Revision

- Top 9 BEST Grammarly Alternatives For Error Free Writing

- 10 BEST Free Keyword Rank Checker Tools for SEO [Online]

- 10 Best Free Online Plagiarism Checker Tools Compared In 2024

- Top 10 Punctuation Checker Applications (2024 Best Reviewed)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Study Skills

How to Annotate an Article

Last Updated: September 26, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a Private Tutor and Life Coach in Santa Cruz, California. In 2018, she founded Mindful & Well, a natural healing and wellness coaching service. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. Emily also received her Wellness Coach Certificate from Cornell University and completed the Mindfulness Training by Mindful Schools. There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 401,389 times.

Annotating a text means that you take notes in the margins and make other markings for reading comprehension. Many people use annotation as part of academic research or to further their understanding of a certain work. To annotate an article, you'll need to ask questions as you go through the text, focus on themes, circle terms you don't understand, and write your opinions on the text's claims. You can annotate an article by hand or with an online note-taking program.

Following General Annotation Procedures

- Background on the author

- Themes throughout the text

- The author’s purpose for writing the text

- The author’s thesis

- Points of confusion

- How the text compares to other texts you are analyzing on the same topic

- Questions to ask your teacher or questions to bring up in class discussions

- Later on, you can gather all of these citations together to form a bibliography or works cited page, if required.

- If you are working with a source that frequently changes, such as a newspaper or website, make sure to mark down the accession date or number (the year the piece was acquired and/or where it came from).

- If you were given an assignment sheet with listed objectives, you might look over your completed annotation and check off each objective when finished. This will ensure that you’ve met all of the requirements.

- You can also write down questions that you plan to bring up during a class discussion. For example, you might write, “What does everyone think about this sentence?” Or, if your reading connects to a future writing assignment, you can ask questions that connect to that work.

- You could write, “Connects to the theme of hope and redemption discussed in class.”

- Use whatever symbol marking system works for you. Just make sure that you are consistent in your use of certain symbols.

- As you review your notes, you can create a list of all of the particular words that are circled. This may make it easier to look them up.

- For example, if the tone of the work changes mid-paragraph, you might write a question mark next to that section.

- To increase your reading comprehension even more, you might want to write down the thesis statement in the margins in your own words.

- The thesis sentence might start with a statement, such as, “I argue…”

- For example, reading online reviews can help you to determine whether or not the work is controversial or has been received without much fanfare.

- If there are multiple authors for the work, start by researching the first name listed.

- You might write, “This may contradict any earlier section.” Or, “I don’t agree with this.”

Annotating an Article by Hand

- You can also file away this paper copy for future reference as you continue your research.

- If you are visual learner, you might consider developing a notation system involving various colors of highlighters and flags.

- Depending on how you’ve taken your notes, you could also remove these Post-its to create an outline prior to writing.

- This rough annotation can then be used to create a larger annotated bibliography. This will help you to see any gaps in your research as well. [11] X Research source

Annotating an Article on a Webpage

- You could also use a program, such as Evernote, MarkUp.io, Bounce, Shared Copy, WebKlipper, or Springnote. Be aware that some of these programs may require a payment for access.

- Depending on your program, you may be able to respond to other people’s comments. You can also designate your notes as private or public.

Community Q&A

- Annotating takes extra time, so make sure to set aside enough time for you to complete your work. [15] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If traditional annotation doesn’t appeal to you, then create a dialectical journal where you write down any quotes that speak to you. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you end up integrating your notes into a written project, make sure to keep your citation information connected. Otherwise, you run the risk of committing plagiarism. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://research.ewu.edu/writers_c_read_study_strategies

- ↑ http://penandthepad.com/annotate-newspaper-article-7730073.html

- ↑ https://www.hunter.cuny.edu/rwc/handouts/the-writing-process-1/invention/Annotating-a-Text/

- ↑ https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/annotating-texts/

- ↑ https://www.biologycorner.com/worksheets/annotate.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/annotated_bibliographies/annotated_bibliography_samples.html

- ↑ https://elearningindustry.com/the-5-best-free-annotation-tools-for-teachers

- ↑ http://www.macworld.com/article/1162946/software-productivity/how-to-annotate-pdfs.html

- ↑ http://www.une.edu/sites/default/files/Reading-and-Annotating.pdf

About This Article

To annotate an article, start by underlining the thesis, or the main argument that the author is making. Next, underline the topic sentences for each paragraph to help you focus on the themes throughout the text. Then, in the margins, write down any questions that you have or those that you’d like your teacher to help you answer. Additionally, jot down your opinions, such as “I don’t agree with this section” to create personal connections to your reading and make it easier to remember the information. For more advice from our Education reviewer, including how to annotate an article on a web page, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Oct 12, 2016

Did this article help you?

Johnie McNorton

Nov 29, 2017

A. Carbahal

Oct 16, 2017

Aide Molina

Jul 10, 2016

Oct 19, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

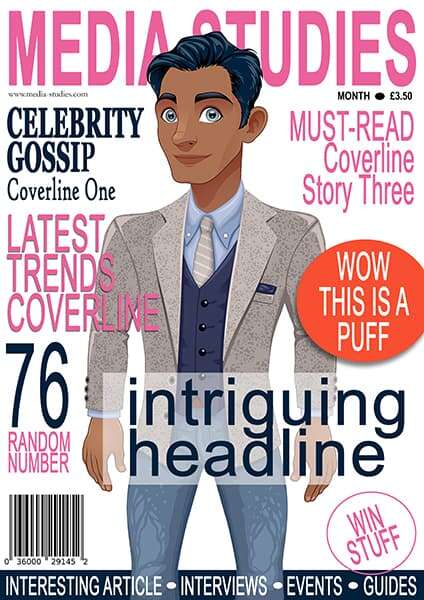

Magazine Cover Analysis

Introduction.

Magazines remain a key part of the media landscape. Some specialist publications target a niche audience while others are more mainstream and appeal to a range of ages and interests. With such a competitive market, a combination of a strong image or concept with snippets of stories is required to grab the audience’s attention. This guide will walk you through the codes and conventions of magazine covers.

If you would like to annotate your own copy of the front cover, you can download the worksheet . You can also view a larger version of the page by right-clicking on the image and opening it in a new window.

In publishing, the masthead refers to the title of the magazine. Printed in large type, it is usually positioned at the top of the page and fills the width of the cover. These factors ensure the brand is instantly recognisable.

The choice of colour and font weight will connect to the genre and ideology of the magazine. Consider the difference between the rough display type of “Kerrang” compared to the elegance of “Brides” magazine:

Although the colour of the title will change according to the particular needs of the issue, the black and grungy title here connotes a rebellious quality, and the use of bold weighting and capital letters conveys confidence. These meanings will resonate with the psychographic profile of the target audience. The lack of space between the letters, known as kerning, makes title visually appealing because we are not distracted by empty spaces. The word kerrang is defined as a power chord struck on the guitar. In some ways, the presentation of the title echoes this meaning.

“Kerrang’s” nameplate is set in a modern typeface called Druk Condensed Super Italic . This sans-serif font is much brasher than the graceful serif of the Eldorado Relay typeface used by “Brides”. Again, the colour of the masthead will change to match the palette of each issue, but this magazine tends to use gold, pink and white quite regularly because of their associations with femininity and luxury. The capital letters look self-assured and ensure the title is the centre of attention.

If you look closely, you can see manual kerning has been employed so the space between each letter is tight but appropriate. Zoom in and spot the difference between “B” and “R” compared to “I” and “D”. This variation ensures the title is as big as possible on the cover but remains legible to the reader.

More generally, if the publication is well-known, the masthead might be obscured by the main image. This layering effect a nice design feature and is aesthetically pleasing.

In conclusion, the masthead should establish the brand and its values. This can be achieved through the choice of font and position on the cover. These two examples certainly encode a clear message to the audience.

Cover Image

Celebrity sells. Many publications note a sharp increase in revenue when the most famous faces dominate the cover. Music magazines will splash an image of a popular band or artist on the front page, while the main actor from the latest blockbuster will no doubt help sell a film magazine.

Invariably, the direct gaze of the person will pierce the viewer and a medium shot or close-up will connect us to the emotional energy of the glamorous model or star. Other non-verbal codes will help support the magazine’s values and message, such as how a smiling bride or the powerful stance of a sports star encode the right meaning for the target audience.

To achieve the most appropriate representation, the mise-en-scène needs to be controlled so expect the main image to be taken from a studio photoshoot. High key lighting is used in fashion magazines to the keep the image fresh and youthful.

Of course, the main image will be directly related to the lead article.

Featured Article

Magazines are full of news reviews, interviews, opinion pieces, exposes, and behind the scenes stories. However, a feature is a longer piece of writing which covers an issue in greater depth than a normal report. The lead article will also be some sort of exclusive with the broadest appeal to the readership.

To give the story prominence, the designers will use large lettering and position the words in a contrasting colour to the background image. In our mock-up, the headline is a similar blue to the character’s clothes, so an opaque box was added to help make it stand out to the reader.

Other important stories are floated along the sides of the cover. Bold and italics will emphasise the text. No matter if they are human interest stories, celebrity gossip, or a profile of a famous politician, short and catchy buzzwords are used to tease the reader into buying the magazine. Enigma codes are also very engaging because they encourage to reader to find out more. Of course, the mode of address will vary depending on the publication, especially if the readers expect the language to be formal or informal.

There might also be a colour connection between the clothing worn by the cover actor and the font choice. In the mock-up, coverline one matches the blue outfit of the character. For the other stories, blue and pink are appealing contrasting colours.

If you are designing your own magazine cover for your coursework, remember it is really difficult to make the headlines stand out if they are placed on a pattern or mixed-coloured background.

Puffs, Plugs and Boxouts

If you do have a multicoloured background with very few areas of high contrast between light and shade, boxouts provide a great way to get your ideas across to the audience. They are simply coloured squares or rectangles positioned beneath the text to help the words stand out.

Another common convention of magazine covers is puffs. These eye-catching graphics are used to draw attention to the text. Instead of a square, the puff in our example is a circle and is conveniently identified by the words “Wow” and “This is a puff”. Importantly, a drop shadow has been used to create a sticker effect which is very popular with designers.

A strong outline, such as the one used for the “Win Stuff”, or a star shape are often used to plug a competition or some other incentive to purchase the magazine.

Strips and Banners

Look at the bottom of our mock-up and you will see a blue strip running across the cover and containing a list of items. These strips usually include information about more minor articles and regular features inside the magazine.

A banner is a larger version of this approach.

Price, Issue and Sell Lines

Magazines should include the date, issue, price and barcode on the cover. If you are creating your own cover, remember to add these details.

Further Reading

The Characteristics of Postmodernism

Website Codes and Conventions

Documentaries

Print Media Advertising

- Camera Shots

Movie Poster Analysis

Thanks for reading!

Recently Added

Rule of Thirds

The Classification of Advertisements

Narrative Functions

Key concepts.

Key Concepts in Post-colonial Theory

Prosumers and the Media

Psychographics

Media studies.

- The Study of Signs

- Ferdinand de Saussure and Signs

- Roland Barthes

- Charles Peirce’s Sign Categories

- Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation

- Binary Opposition

- Vladimir Propp

- Tzvetan Todorov

- Quest Plots

- Barthes’ 5 Narrative Codes

- Key Concepts in Genre

- David Gauntlett and Identity

- Paul Gilroy

- Liesbet van Zoonen

- The Male Gaze

- The Bechdel Test

- bell hooks and Intersectionality

- The Cultural Industries

- Hypodermic Needle Theory

- Two-Step Flow Theory

- Cultivation Theory

- Stuart Hall’s Reception Theory

- Abraham Maslow

- Uses and Gratifications

- Moral Panic

- Indicative Content

- Statement of Intent

- AQA A-Level

- Exam Practice

- How to Cite

- Language & Lit

- Rhyme & Rhythm

- The Rewrite

- Search Glass

How to Annotate a Newspaper Article

An annotation of a newspaper article serves as a brief analysis of the original piece. Written in concise language, an annotation is intended to explain the article succinctly and illuminate the meaning behind the article. An annotation differs from a standard summary or an abstract in that the writer of an annotation is expected to use some of his own knowledge and judgment while annotating the article. An annotation should help the reader decide if reading the original article would be worthwhile.

Begin your annotation with the source citation, according the style guide you are using, such as MLA or APA. Your instructor might have specific requirements.

Using MLA for a print newspaper article, your citation should look like this:

Author(s). "Title of Article." Title of Periodical Day Month Year: pages. Print.

Using MLA for an electronic newspaper article, your citation should look like this:

Editor, author, or compiler name (if available). Title of article. Name of Site. Version number. Name of institution/organization affiliated with the site (sponsor or publisher), date of resource creation (if available). Medium of publication. Date of access.

Note that your citation should be formatted in a hanging indent; Microsoft Word has a hanging-indent function.

Using APA for a print newspaper article, your citation should look like this:

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year). Title of article. Title of Periodical, volume number(issue number), pages. http://dx.doi.org/xx.xxx/yyyyy

Using APA for an electronic newspaper article, your citation should look like this:

Author, A. A., & Author, B. B. (Date of publication). Title of article. Title of Newspaper. pages.

Note that your citation should be formatted in a hanging indent; Word has a hanging-indent function.

Read the newspaper article carefully and with an analytical mind. Consider who wrote the article, when the newspaper printed it and the type of publication in which it appeared.

For example, the author of an article published in a specialized trade publication might have a markedly different outlook from a writer for a general-interest daily newspaper.

Research the qualifications of the article's author and discern why he wrote the piece. Identify the main ideas and the overall message the article's author is trying to communicate. Begin to formulate a critical evaluation of the article's content.

Notice the article's level of reading difficulty and whether it contains any jargon, scientific terminology or arcane language aimed at readers in a specific business or industry. Compare the article to other works you have read on similar topics. Ask yourself what the article adds to the existing body of knowledge on the subject.

Write a concise one-paragraph annotation of the article, using the ideas you developed while reading and analyzing the piece.

Begin your annotation by citing the author's name, the article's title, the name of the publication in which it appeared and the date it was published.

Explain the primary idea of the article and whether the author succeeded in conveying his message. Note any areas in which the article's author fell short of his goal and how those parts of the article could have been improved.

Keep your annotation short and remain on topic. Write at least three or four sentences in your annotation of a newspaper article, but do not exceed a length of approximately 150 words. Write your annotation in the third person, refraining from the use of "you" or "I."

- Ursinus College: Library Research Guide 12: Preparing Abstracts and Annotations

- Weber State University: Creating Annotations

- OWL Purdue: MLA Works Cited: Periodicals

- OWL Purdue: APA Reference List: Articles in Periodicals

- OWL Purdue: MLA Works Cited: Electronic Sources (Web Publications)

- OWL Purdue: Reference List: Electronic Sources (Web Publications)

Steven Wilkens has been a professional editor and writer since 1994. His work has appeared in national newspapers and magazines, including "The Honolulu Advertiser" and "USA Today." Wilkens received a Bachelor of Arts in English from Saint Joseph's University.

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Sample Annotations

This example uses MLA format for an online magazine. It both summarizes and assesses the article in the annotation. First it provides a brief summary of the article, covering the main points of the work. Then it notes its limitation.

Dickenson’s article gives a history of the oil spill created by the explosion on the Deepwater Horizon rig and efforts to downplay the disaster by BP and the Obama administration. The author concedes the role of the Bush administration in allowing oil companies to control the Mineral Management Service (MMS), but he blames the Obama administration for not correcting this problem and not taking responsibility for the cleanup immediately after the spill. BP drilled the well using cost-cutting methods instead of safer construction plans and without a strategy for sealing a leak. BP has a history of safety violations and should not have been trusted with the cleanup. Officials from NOAA warned of the extent of the spill immediately, but both BP and the President downplayed the damage. Dickenson concludes that the President’s decision not to act immediately after the spill will affect the Gulf region for many years. This article provides readers with details about obvious problems with the Deepwater Horizon well before the explosion and explains how a quicker response by the President could have prevented some of the damage to the fragile Gulf ecosystem. Although the article was written only a month after the disaster, it shows early reactions to the spill and cleanup attempts.

Dolgin begins his essay by describing research into RNA vaccines. In 2012, researcher Andy Geall used RNA nucleotides to vaccinate rats against a respiratory virus, and in 2013 he developed a vaccination against an avian flu, but his vaccine was not used. The advent of COVID-19 speeded up research into the development of RNA vaccines, and now major pharmaceutical companies are researching using them to prevent diseases like rabies, malaria, and HIV. Once the genome sequence of a virus in known, developing a vaccine is quicker when using RNA technology. One issue with RNA vaccines is that they must be stored at cold temperatures, although two companies claim to have solved this problem. Although RNA vaccines require two injections at this time, researchers are looking for easier ways to deliver them; one example is using patches placed on the skin to deliver the vaccine slowly, which may reduce side effects. Research is continuing in hopes of creating vaccines for diseases like muscular dystrophy and cystic fibrosis, although many believe that this research will slow when COVID-19 is no longer in the news. Dolgin’s essay is documented with footnotes citing major medical publications like Lancet and Vaccine and published in Nature, a respected journal that includes peer-reviewed research. Dolgin is a science journalist with a PhD in evolutionary genetics who contributes articles to journals like Scientific American and The Scientist. Although this essay does include scientific terms, it is easy to understand because it is written for a general audience.

This material was developed by the COMPSS team and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License . All materials created by the COMPSS team are free to use and can be adopted, adapted, and/or shared at will as long as the materials are attributed. Please keep this information on COMPSS materials you adapt, adopt, and/or share.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

APA Style 7th Edition

- Advertisements

- Books & eBooks

- Book Reviews

- Class Notes, Class Lectures and Presentations

- Encyclopedias & Dictionaries

- Government Documents

- Images, Charts, Graphs, Maps & Tables

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Newspaper Articles

- Personal Communication (Interviews & Emails)

- Social Media

- Videos & DVDs

- What is a DOI?

- When Creating Digital Assignments

- When Information is Missing

- Works Cited in Another Source

- In-Text Citation Components

- Paraphrasing

- Paper Formatting

- Citation Basics

- Reference List and Sample Papers

- Annotated Bibliography

- Academic Writer

- Plagiarism & Citations

Note : All citations should be double spaced and have a hanging indent in a Reference List.

A "hanging indent" means that each subsequent line after the first line of your citation should be indented by 0.5 inches.

If a magazine article has no author, start the citation with the article title.

If a magazine article is written by "Anonymous", put the word "Anonymous" where you'd normally have the author's name.

Italicize titles of magazines. Do not italicize the titles of articles.

Capitalize only the first letter of the first word of the article title. If there is a colon in the article title, also capitalize the first letter of the first word after the colon.

If an article has no date, use the short form n.d. where you would normally put the date.

Volume and Issue Numbers

Italicize volume numbers but not issue numbers.

Retrieval Dates

Most articles will not need these in the citation since you only need to provide a retrieval date when citing from places where content may change often and without notice.

Page Numbers

If an article doesn't appear on continuous pages, list all the page numbers the article is on, separated by commas. For example (4, 6, 12-14)

How Do I Know If It's a Magazine?

Photo courtesy of Flickr by Manoj Jacob. Available under a Creative Commons license.

Not sure whether your article is from a magazine? Look for these characteristics:

Popular magazines:

- Main purpose is to entertain, sell products or promote a viewpoint.

- Appeal to the general public.

- Often have many photos and illustrations, as well as many advertisements.

- Author may or may not have subject expertise.

- Name and credentials of authors often NOT provided.

- Articles tend to be short –less than 5 pages.

- Unlikely to have a bibliography or references list.

Trade magazines:

- Main purpose is to update and inform readers on current trends in a specific industry or trade.

- Audience is members of a specific industry or trade or professors and students in that trade or industry.

- May have photos and numerous advertisements, but still assume that readers understand specific jargon of the profession.

- Usually published by an association.

- Authors are professionals working in the specific industry or trade.

Magazine Article from a Library Database or in Print - One Author

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication, Month Day if Given). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Magazine, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number.

| Abramsky, S. (2012, May 14). The other America 2012. (20), 11-18. | |

| (Author's Last Name, Year) Example: (Abramsky, 2012) | |

| (Author's Last Name, Year, p. Page Number) Example: (Abramsky, 2012, p. 14) |

Magazine Article from a Library Database or in Print - Two to Twenty Authors

Author's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given., & Last Name of Second Author, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication, Month Day if Given). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Magazine, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number if given.

Note : Must spell out up to twenty author names. Separate the authors' names by putting a comma between them. For the final author listed add an ampersand (&) after the comma and before the final author's last name.

| Gross, A., & Murphy, E. (2010, January/February). Seal of disapproval. (1), 34-37. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Magazine Article from a Library Database or in Print - Unknown AuthorArticle title: Subtitle if any. (Year of Publication, Month Day if Given). Name of Magazine, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number if given.

Magazine Article from a Library Database or in Print - Signed AnonymousAnonymous. (Year of Publication, Month Day if Given). Article title: Subtitle if any. Name of Magazine, Volume Number (Issue Number), first page number-last page number if given. Note : If and only if the work is signed "Anonymous", use Anonymous where you'd normally put the author's name. If the work has no named author but is not signed "Anonymous", follow the example for Unknown Author.

Magazine Article from a WebsiteAuthor's Last Name, First Initial. Second Initial if Given. (Year of Publication). Title of article: Subtitle if any. Name of Magazine, Volume Number (Issue Number if given), first page number-last page number if given. URL

In-Text Citation for Two or More Authors/Editors

Magazines Analysing a MagazineIn the UK alone, there are approximately 8000 different magazine titles for general sale. Part of Media Studies Industries Analysing a MagazineA magazine's cover is the most important element, in terms of how it appeals to potential buyers At a glance, you can generally tell if a magazine is going to satisfy your interests, outlook and aspirations close aspiration A hope or ambition in life. . Different magazines have distinct house styles that convey their brand identity close brand identity The image a company constructs for itself through the use of logos, slogans and other marketing tools in order to appeal to an audience. . The brand identity and point-of-view (or ideology close ideology A set of ideas or thoughts that someone, or a group of people, believe in. The plural of this is 'ideologies'. ) conveyed by a magazine is vital when we consider that magazines are selling us content that is often aspirational. Modes of addressDifferent magazines have different modes of address close mode of address The ways in which a media text uses language to speak to its target audience - for example, formal or informal. . This may be formal and informative, or more casual and catchy. Magazines use design and language to stand out from their competitors in the same subgenre close subgenre A subcategory within a particular genre. . For example, Kerrang! and NME both use an informal tone and style but Kerrang! uses language that will appeal specifically to heavy metal fans. NME , which is also informal, uses language that will appeal to indie music fans. A magazine contents page lists all of its content including regular pages and special features. The audience (or readers) will normally expect to find regular pages in the same place for each editon. For example, readers of Empire will know where to find cinema reviews, as opposed to feature articles. Readers of a lifestyle magazine will expect to find items like horoscopes near the back. Features are particular to each magazine issue. They will contain new content on current topics and may be an exclusive for the magazine. More guides on this topic

Related links

APA Annotated Bibliography

Magazine Article

Author(s) of Article. (date of publication). Complete title of article. Name of Magazine. Direct URL for article Dickey, C. (2016, November 14). The broken technology of ghost hunting. The Atlantic . https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/11/the-broken-technology-of-ghost-hunting/506627 Where do I find . . . ?Click the info icons on the magazine website page below to see where you would find the items needed for a citation. Check your understanding by answering these review questions. If you get one wrong, read back through the material and try again!

Sample Annotations - UNDER CONSTRUCTION

If you want an A...

Always check with your faculty on whether to format your annotation with these brackets, or as a paragraph.  Scholarly / Academic SourceZemel, Carol. “Sorrowing Women, Rescuing Men: Van Gogh’s Images of Women and Family.” Art History , vol. 10, no. 3, Sept. 1987, pp. 351-368. Art & Architecture Source , https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1987.tb00261.x. [Author Credentials] Carol Zemel is an art historian with a PhD from Columbia University. She has authored many books and articles in art journals. She was a Professor in the Department of Visual Art & Art History at New York University. [Audience / Type of Information] Art History is a peer-reviewed journal. The audience for it is art historians and probably undergraduate majors in art history. The article is an in-depth discussion (24 pages) on the topic. It contains only black and white illustrations. Otherwise, the text is mostly text-based with lots of footnotes and a bibliography. [Purpose / Bias / Point of View] The author has a feminist focus, and she uses historical information to demonstrate that VG's paintings of women reflected society views on female sexuality and prostitution. She argues that he viewed prostitutes as fallen women who could be saved through a proper domestic life. The author questions the 19th century male assumption of what all women inherently wanted. [Currency of the Source] This article was published in 1987, which was after the feminist theory had been well developed so that perspective is included. There were a couple of other articles about Van Gogh and women that I can also use as a comparison. [Coverage / Scope / Content] The author thoroughly covers this content, although the subject is quite narrow in scope. [Relevance to Paper] This article discusses the images of women and family in the paintings Vincent van Gogh. I was interested in Van Gogh’s views about women and there was a substantial number of examples and theories of Van Gogh’s view about women that I can use in my paper. Trade / Professional SourceStasukevich, lain. "Reclaiming Art." American Cinematographer , vol. 96, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 30-36. Art & Architecture Source . [Author Credentials] Stasukevich is a staff writer for American Cinematographer . I could find no other information on him anywhere except in IMDB, it says he is a camera person and he has one TV credit. [Audience / Type of Information] American Cinematographer is a trade magazine published in Hollywood. I can tell because it is filled with ads for cameras and movies. The information in the articles is fairly technical providing information on camera settings, lighting, and lenses. [Purpose / Bias / Point of View] The article interviews Bruno Delbonnel, cinematographer for Burton, asking him questions about his vision for the movie Big Eyes . The purpose is to share Delbonnel’s approach to visual effects and photography with other filmmakers. [Currency of the Source] This article was published at about the same time Big Eyes was released. [Coverage / Scope / Content] There are lots of pictures and lots of questions. When asked about the aesthetics of the film, Delbonnel comments on his goal of achieving a hyperrealistic or surreal effect and goes on to discuss his preferred diffusion levels. Other topics covered include lighting techniques, his collaboration with Burton, and digital cinematography. [Relevance to Paper] Because I am a digital major, I found this information very relevant to me. It gave me information about why and how Burton and his cinematographer collaborate to make an interesting movie. Collaboration is one of the points I plan to discuss in my paper. Substantial NewsCashdan, Marina. “Tim Burton: Hailing Filmdom’s Oddest Artist.” Modern Painters , vol. 21, no. 8, Nov. 2009, pp. 48–57. Art & Architecture Source , search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=asu&AN=505267791&site=ehost-live&scope=site. [Author Credentials] Marina Cashdan attended Columbia University. She is writer and editor whose work regularly appears in the New York Times , Huffington Post , Style Magazine , Frieze , Art in America , among other arts magazines. She was formerly the executive editor at Modern Painters . She is currently the editorial director of Artsy . [Audience / Type of Information] Modern Painters is very glossy arts magazine, filled with photos and advertising. The audience for this is definitely artists, but also the general educated public with an interest in the arts. Tim Burton has mass appeal, so this could also be classified at General Interest/Substantial News. [Purpose / Bias / Point of View] I think the point of view is promotional. Essentially, the publication promotes activities of the art world, especially New York. This article promoted Tim Burton who was having an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. She is basically arguing that Burton is an artist as well as a filmmaker. [Currency of the Source] This article was published in 2009, but that is not too old to be relevant. [Coverage / Scope / Content] It's a fairly lengthy article that covers Burton's painting practice thoroughly. [Relevance to Paper ] This article is perfect for my paper because she interviewed Burton and includes quotes to show how he perceives himself. There are also many images of his work, most of which are not seen in the books I’ve found. TechInsider. “Mickey Mouse And Copyright Law.” YouTube , 3 Oct. 2015, https://youtu.be/_6u7JkQAFMw. [Author credentials] TechInsider is part of Business Insider , a business news site. The video has no credits, not even for the narrator. [Audience/Type of Information] Short news video that appeals to the general public. [Bias / Point of View] It is decidedly anti-Disney and negative towards other big media companies. It favors shorter copyright terms and the public domain. It is a passive aggressive call to arms. [Content / Coverage / Scope] It focuses on one character owned by one company, and how that has affected the length of copyright terms in the United States. [Currency of the Source] This video was created in 2015 to alert viewers about possible major changes in copyright law. It was wrong; Disney and other big media did not pursue another copyright term extension. [Relevance to Paper] I wanted a video that had a negative point of view. It succinctly covered major changes in US copyright law over the last 100 years. Popular SourceWallace, Amy and Tim Burton. "Tim Burton I." Los Angeles Magazine , vol. 56, no. 5, May 2011, pp. 38-40. OmniFile Full Text Select (H.W. Wilson). [Author Credentials] Amy Wallace is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared many well-known popular magazines including GQ , The New Yorker , Vanity Fair , Esquire , and Elle. She spent four years as a Senior Writer at Los Angeles Magazine and is now Editor-at-Large. [Audience / Type of Information] Los Angeles Magazine is a large-circulation popular magazine. Tim Burton has mass appeal, so this could be classified at General Interest/Substantial News. [Purpose / Bias / Point of View] I think the point of view is promotional. Essentially, the publication promotes people or activities associated with Los Angeles. In this case, Burton was having an exhibition at LACMA. [Currency of the Source] This article came out when the exhibition was running. [Coverage / Scope / Content] This is a short but Burton does discusses various aspects of his relationship to Los Angeles including his childhood in Burbank, his time in CalArts' Disney animation program, and the exhibition of his work at LACMA. [Relevance to Paper] This article is very short, but Burton does discuss his involvement with Los Angeles, his education at CalArts and his exhibition at LACMA. It gave me some basic facts, but not much more. U.S. Copyright Office. “What Is Copyright?” YouTube , 30 Oct. 2019, https://youtu.be/ukFl-siTFtg. [Author credentials] The US Copyright Office is the federal department in charge of copyright. [Audience/Type of Information] The audience is the American general public, especially people who create content that is copyrightable. Since it is a promotional video, it skews more towards Popular than News. [Bias / Point of View] Although it takes a neutral tone, the US Copyright Office is promoting itself and its services. It strongly encourages people to register their copyrights even though it is no longer required. [Content / Coverage / Scope] Brief introduction to copyright law in the United States. [Currency of the Source] This video is very current, as it was published in 2019, and no new major copyright legislation has been passed. [Relevance to Paper] I liked how it differentiated between copyright, trademarks, and patents. I wanted to see how a government entity tried to appeal to the masses. Wikimedia Foundation. “What Is Creative Commons?” YouTube , 7 Feb. 2017, https://youtu.be/dPZTh2NKTm4. [Author credentials] The Wikimedia Foundation is a non-profit that runs Wikipedia and other sites. Victor Grigas is a photographer and video producer who works for the Foundation. [Audience/Type of Information] It is an advertisement meant to appeal to tech-savvy creators in the general public. [Bias / Point of View] It is heavily biased against copyright laws. It promotes using Creative Commons licenses as a way to empower creators. In fact, it is used as a promotional resource on CreativeCommons.org. [Content / Coverage / Scope] Introduction to Creative Commons licenses by illustrating its principles. It does not go into any detail about the actual licenses. [Currency of the Source] The information is still current, though its video style and music may be a little out-of-date now. [Relevance to Paper] CC licenses can be intimidating. I liked how it presented the concepts in a non-threatening manner, including attributions in the end credits (where I found Victor Grigas).

Otis College of Art and Design | 9045 Lincoln Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90045 | MyOtis Millard Sheets Library | MyOtis | 310-665-6930 | Ask a Librarian Writing an Annotated Bibliography: Citing a journal or magazine article in APA

Basic Journal/Magazine Article CitationAuthor's Last Name, Author's First Initial. Author's Middle Initial. (Year, Month/Date/Season). Title of article. Title of Journal/Magazine, Volume (Issue), Page(s). https://doi:xx.xxxxxxx (Note: Not every article will have a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) number in the reference citation. The DOI is an alphanumeric string that is assigned to some electronic articles, and if it appears in the citation information for an article you are citing from an electronic source, it should be included. Reference citations without a DOI will look the same as the example citation above, but without "doi:xx.xxxxxxxx". If no DOI is assigned to an article, but you retrieved the article online, be sure to include the URL for the page where you found the article, using the following format: Retrieved from http://www.websiteaddress.com) Example Journal article, one authorSutherland, M. B. (2000, May). Problems of diversity in policy and practice: Celtic languages in the United Kingdom . Comparative Education , 36 (2),199-209. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060050045363 Example Journal article, 3 to 6 authorsList all authors up to 20, with the ampersand (&) used between the last two authors. If 21 authors are listed, list up to 19, ellipsis and no ampersand before the last author. Kennedy, L. F., & Yavuz, M. S. (2019). Metal and musicology. Metal Music Studies, 5 (3), 293-296. https://doi.org/10.1386/mms.5.3.293_2 Example Magazine articleElmer-DeWitt, P., & Farley, C. J. (1994, March 21). People who eat Hostess Twinkies. Time , 143 (12), 22. Basic Newspaper CitationNewspaper article with an author. Schultz, S. (2005, December). Calls made to strengthen state energy policies. The Country Today , 1A, 2A. Title of the article. (Year, Month, Day). Title of the article. Title of The Newspaper or News Website, ( Page(s) if print). URL of the article if online In-Text CitationsFor an overview of the various ways to cite information in text in APA style, see the Purdue OWL, which provides an overview of the basic in text citation formats.

How to Annotate TextsUse the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide: Annotation FundamentalsHow to start annotating , how to annotate digital texts, how to annotate a textbook, how to annotate a scholarly article or book, how to annotate literature, how to annotate images, videos, and performances, additional resources for teachers. Writing in your books can make you smarter. Or, at least (according to education experts), annotation–an umbrella term for underlining, highlighting, circling, and, most importantly, leaving comments in the margins–helps students to remember and comprehend what they read. Annotation is like a conversation between reader and text. Proper annotation allows students to record their own opinions and reactions, which can serve as the inspiration for research questions and theses. So, whether you're reading a novel, poem, news article, or science textbook, taking notes along the way can give you an advantage in preparing for tests or writing essays. This guide contains resources that explain the benefits of annotating texts, provide annotation tools, and suggest approaches for diverse kinds of texts; the last section includes lesson plans and exercises for teachers. Why annotate? As the resources below explain, annotation allows students to emphasize connections to material covered elsewhere in the text (or in other texts), material covered previously in the course, or material covered in lectures and discussion. In other words, proper annotation is an organizing tool and a time saver. The links in this section will introduce you to the theory, practice, and purpose of annotation. How to Mark a Book, by Mortimer Adler This famous, charming essay lays out the case for marking up books, and provides practical suggestions at the end including underlining, highlighting, circling key words, using vertical lines to mark shifts in tone/subject, numbering points in an argument, and keeping track of questions that occur to you as you read. How Annotation Reshapes Student Thinking (TeacherHUB) In this article, a high school teacher discusses the importance of annotation and how annotation encourages more effective critical thinking. The Future of Annotation (Journal of Business and Technical Communication) This scholarly article summarizes research on the benefits of annotation in the classroom and in business. It also discusses how technology and digital texts might affect the future of annotation. Annotating to Deepen Understanding (Texas Education Agency) This website provides another introduction to annotation (designed for 11th graders). It includes a helpful section that teaches students how to annotate reading comprehension passages on tests. Once you understand what annotation is, you're ready to begin. But what tools do you need? How do you prepare? The resources linked in this section list strategies and techniques you can use to start annotating. What is Annotating? (Charleston County School District) This resource gives an overview of annotation styles, including useful shorthands and symbols. This is a good place for a student who has never annotated before to begin. How to Annotate Text While Reading (YouTube) This video tutorial (appropriate for grades 6–10) explains the basic ins and outs of annotation and gives examples of the type of information students should be looking for. Annotation Practices: Reading a Play-text vs. Watching Film (U Calgary) This blog post, written by a student, talks about how the goals and approaches of annotation might change depending on the type of text or performance being observed. Annotating Texts with Sticky Notes (Lyndhurst Schools) Sometimes students are asked to annotate books they don't own or can't write in for other reasons. This resource provides some strategies for using sticky notes instead. Teaching Students to Close Read...When You Can't Mark the Text (Performing in Education) Here, a sixth grade teacher demonstrates the strategies she uses for getting her students to annotate with sticky notes. This resource includes a link to the teacher's free Annotation Bookmark (via Teachers Pay Teachers). Digital texts can present a special challenge when it comes to annotation; emerging research suggests that many students struggle to critically read and retain information from digital texts. However, proper annotation can solve the problem. This section contains links to the most highly-utilized platforms for electronic annotation. Evernote is one of the two big players in the "digital annotation apps" game. In addition to allowing users to annotate digital documents, the service (for a fee) allows users to group multiple formats (PDF, webpages, scanned hand-written notes) into separate notebooks, create voice recordings, and sync across all sorts of devices. OneNote is Evernote's main competitor. Reviews suggest that OneNote allows for more freedom for digital note-taking than Evernote, but that it is slightly more awkward to import and annotate a PDF, especially on certain platforms. However, OneNote's free version is slightly more feature-filled, and OneNote allows you to link your notes to time stamps on an audio recording. Diigo is a basic browser extension that allows a user to annotate webpages. Diigo also offers a Screenshot app that allows for direct saving to Google Drive. While the creators of Hypothesis like to focus on their app's social dimension, students are more likely to be interested in the private highlighting and annotating functions of this program. Foxit PDF Reader Foxit is one of the leading PDF readers. Though the full suite must be purchased, Foxit offers a number of annotation and highlighting tools for free. Nitro PDF Reader This is another well-reviewed, free PDF reader that includes annotation and highlighting. Annotation, text editing, and other tools are included in the free version. Goodreader is a very popular Mac-only app that includes annotation and editing tools for PDFs, Word documents, Powerpoint, and other formats. Although textbooks have vocabulary lists, summaries, and other features to emphasize important material, annotation can allow students to process information and discover their own connections. This section links to guides and video tutorials that introduce you to textbook annotation. Annotating Textbooks (Niagara University) This PDF provides a basic introduction as well as strategies including focusing on main ideas, working by section or chapter, annotating in your own words, and turning section headings into questions. A Simple Guide to Text Annotation (Catawba College) The simple, practical strategies laid out in this step-by-step guide will help students learn how to break down chapters in their textbooks using main ideas, definitions, lists, summaries, and potential test questions. Annotating (Mercer Community College) This packet, an excerpt from a literature textbook, provides a short exercise and some examples of how to do textbook annotation, including using shorthand and symbols. Reading Your Healthcare Textbook: Annotation (Saddleback College) This powerpoint contains a number of helpful suggestions, especially for students who are new to annotation. It emphasizes limited highlighting, lots of student writing, and using key words to find the most important information in a textbook. Despite the title, it is useful to a student in any discipline. Annotating a Textbook (Excelsior College OWL) This video (with included transcript) discusses how to use textbook features like boxes and sidebars to help guide annotation. It's an extremely helpful, detailed discussion of how textbooks are organized. Because scholarly articles and books have complex arguments and often depend on technical vocabulary, they present particular challenges for an annotating student. The resources in this section help students get to the heart of scholarly texts in order to annotate and, by extension, understand the reading. Annotating a Text (Hunter College) This resource is designed for college students and shows how to annotate a scholarly article using highlighting, paraphrase, a descriptive outline, and a two-margin approach. It ends with a sample passage marked up using the strategies provided. Guide to Annotating the Scholarly Article (ReadWriteThink.org) This is an effective introduction to annotating scholarly articles across all disciplines. This resource encourages students to break down how the article uses primary and secondary sources and to annotate the types of arguments and persuasive strategies (synthesis, analysis, compare/contrast). How to Highlight and Annotate Your Research Articles (CHHS Media Center) This video, developed by a high school media specialist, provides an effective beginner-level introduction to annotating research articles. How to Read a Scholarly Book (AndrewJacobs.org) In this essay, a college professor lets readers in on the secrets of scholarly monographs. Though he does not discuss annotation, he explains how to find a scholarly book's thesis, methodology, and often even a brief literature review in the introduction. This is a key place for students to focus when creating annotations. A 5-step Approach to Reading Scholarly Literature and Taking Notes (Heather Young Leslie) This resource, written by a professor of anthropology, is an even more comprehensive and detailed guide to reading scholarly literature. Combining the annotation techniques above with the reading strategy here allows students to process scholarly book efficiently. Annotation is also an important part of close reading works of literature. Annotating helps students recognize symbolism, double meanings, and other literary devices. These resources provide additional guidelines on annotating literature. AP English Language Annotation Guide (YouTube) In this ~10 minute video, an AP Language teacher provides tips and suggestions for using annotations to point out rhetorical strategies and other important information. Annotating Text Lesson (YouTube) In this video tutorial, an English teacher shows how she uses the white board to guide students through annotation and close reading. This resource uses an in-depth example to model annotation step-by-step. Close Reading a Text and Avoiding Pitfalls (Purdue OWL) This resources demonstrates how annotation is a central part of a solid close reading strategy; it also lists common mistakes to avoid in the annotation process. AP Literature Assignment: Annotating Literature (Mount Notre Dame H.S.) This brief assignment sheet contains suggestions for what to annotate in a novel, including building connections between parts of the book, among multiple books you are reading/have read, and between the book and your own experience. It also includes samples of quality annotations. AP Handout: Annotation Guide (Covington Catholic H.S.) This annotation guide shows how to keep track of symbolism, figurative language, and other devices in a novel using a highlighter, a pencil, and every part of a book (including the front and back covers). In addition to written resources, it's possible to annotate visual "texts" like theatrical performances, movies, sculptures, and paintings. Taking notes on visual texts allows students to recall details after viewing a resource which, unlike a book, can't be re-read or re-visited ( for example, a play that has finished its run, or an art exhibition that is far away). These resources draw attention to the special questions and techniques that students should use when dealing with visual texts. How to Take Notes on Videos (U of Southern California) This resource is a good place to start for a student who has never had to take notes on film before. It briefly outlines three general approaches to note-taking on a film. How to Analyze a Movie, Step-by-Step (San Diego Film Festival) This detailed guide provides lots of tips for film criticism and analysis. It contains a list of specific questions to ask with respect to plot, character development, direction, musical score, cinematography, special effects, and more. How to "Read" a Film (UPenn) This resource provides an academic perspective on the art of annotating and analyzing a film. Like other resources, it provides students a checklist of things to watch out for as they watch the film. Art Annotation Guide (Gosford Hill School) This resource focuses on how to annotate a piece of art with respect to its formal elements like line, tone, mood, and composition. It contains a number of helpful questions and relevant examples. Photography Annotation (Arts at Trinity) This resource is designed specifically for photography students. Like some of the other resources on this list, it primarily focuses on formal elements, but also shows students how to integrate the specific technical vocabulary of modern photography. This resource also contains a number of helpful sample annotations. How to Review a Play (U of Wisconsin) This resource from the University of Wisconsin Writing Center is designed to help students write a review of a play. It contains suggested questions for students to keep in mind as they watch a given production. This resource helps students think about staging, props, script alterations, and many other key elements of a performance. This section contains links to lessons plans and exercises suitable for high school and college instructors. Beyond the Yellow Highlighter: Teaching Annotation Skills to Improve Reading Comprehension (English Journal) In this journal article, a high school teacher talks about her approach to teaching annotation. This article makes a clear distinction between annotation and mere highlighting. Lesson Plan for Teaching Annotation, Grades 9–12 (readwritethink.org) This lesson plan, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, contains four complete lessons that help introduce high school students to annotation. Teaching Theme Using Close Reading (Performing in Education) This lesson plan was developed by a middle school teacher, and is aligned to Common Core. The teacher presents her strategies and resources in comprehensive fashion. Analyzing a Speech Using Annotation (UNC-TV/PBS Learning Media) This complete lesson plan, which includes a guide for the teacher and relevant handouts for students, will prepare students to analyze both the written and presentation components of a speech. This lesson plan is best for students in 6th–10th grade. Writing to Learn History: Annotation and Mini-Writes (teachinghistory.org) This teaching guide, developed for high school History classes, provides handouts and suggested exercises that can help students become more comfortable with annotating historical sources. Writing About Art (The College Board) This Prezi presentation is useful to any teacher introducing students to the basics of annotating art. The presentation covers annotating for both formal elements and historical/cultural significance. Film Study Worksheets (TeachWithMovies.org) This resource contains links to a general film study worksheet, as well as specific worksheets for novel adaptations, historical films, documentaries, and more. These resources are appropriate for advanced middle school students and some high school students. Annotation Practice Worksheet (La Guardia Community College) This worksheet has a sample text and instructions for students to annotate it. It is a useful resource for teachers who want to give their students a chance to practice, but don't have the time to select an appropriate piece of text.

Need something? Request a new guide . How can we improve? Share feedback . LitCharts is hiring!   Magazine Article ReferencesThis page contains reference examples for magazine articles. Lyons, D. (2009, June 15). Don’t ‘iTune’ us: It’s geeks versus writers. Guess who’s winning. Newsweek , 153 (24), 27. Schaefer, N. K., & Shapiro, B. (2019, September 6). New middle chapter in the story of human evolution. Science , 365 (6457), 981–982. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay3550 Schulman, M. (2019, September 9). Superfans: A love story. The New Yorker . https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/16/superfans-a-love-story

Magazine articles references are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 10.1 and the Concise Guide Section 10.1