- ASH Foundation

- Log in or create an account

- Publications

- Diversity Equity and Inclusion

- Global Initiatives

- Resources for Hematology Fellows

- American Society of Hematology

- Hematopoiesis Case Studies

Case Study: 29-Year-Old Female with Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Agenda for Nematology Research

- Precision Medicine

- Genome Editing and Gene Therapy

- Immunologic Treatment

- Research Support and Funding

A 29-year-old female (G1P1) is readmitted two weeks post–vaginal delivery due to increased vaginal bleeding. She reports that the bleeding began on the tenth day after delivery and has increased in severity each subsequent day. The delivery was uncomplicated with minimal blood loss and the patient did not receive any epidural anesthesia. She has taken 200 mg of ibuprofen daily since delivery. The patient reports a medical history of iron deficient anemia due to menorrhagia. She is adopted and does not know her family history.

Since admission, the patient has received three units of blood. The obstetrics team has ruled out retained placental tissue and uterine atony as the cause of bleeding. Her laboratory values are as follows:

What hematologic disease is most likely contributing to her bleeding?

- NSAID-induced platelet dysfunction

- Acquired factor VIII inhibitor

- von Willebrand disease

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Microangiopathy hemolytic anemia

Explanation

This patient is presenting with secondary postpartum hemorrhage with a clinical and laboratory history suggestive of von Willebrand disease (vWD). Overall, there is a 20 percent risk of peripartum bleeding with vWD, and 75 percent of women with moderate to severe vWD can experience severe bleeding. Bleeding can be seen from any type of vWD. For women with mild forms of vWD, the peripartum period can be the first manifestation of the disease. 1 Furthermore, since peripartum bleeding unrelated to a bleeding disorder is common, the diagnosis of an underlying bleeding diathesis may not be considered.

During pregnancy both factor VIII and von Willebrand factor (vWF) levels increase, with peaks at 29 to 32 weeks gestation and at 35 weeks gestation, respectively. 2 Following delivery, vWF levels may fall precipitously within the first few weeks resulting in delayed uterine bleeding. 3 Management of women with known vWD includes monitoring vWF levels during pregnancy and for three to four weeks post-partum to ensure return to baseline. Prophylaxis and treatment of vWD during pregnancy is based upon the severity of disease and specific type of vWD.

Acquired factor VIII inhibitors are a rare but serious cause of secondary postpartum hemorrhage. 4 The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is typically significantly prolonged if there is a factor VIII inhibitor. Disseminated intravascular coagulation is an important cause of post-partum hemorrhage. Significant prolongations of the aPTT and PT as well as low fibrinogen levels are necessary to make the diagnosis. Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia may occur in the peripartum period and is associated with low hemoglobin and platelets. However, this diagnosis results in manifestations of microvascular thrombosis rather than hemorrhage.

Case study submitted by James N. Cooper, MD, of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

- Ragni MV, Bontemp FA, Hassett AC. von Willebrand disease and bleeding in women . Haemophilia. 1999; 5:313-317

- Sié P, Caron C, Azam J, et el. Reassessment of von Willebrand factor (VWF), VWF propeptide, factor VIII:C and plasminogen activator inhibitors 1 and 2 during normal pregnancy . Br J Haematol. 2003; 121:897-903.

- Kujovich JL. von Willebrand disease and pregnancy . J Thromb Haemost. 2005; 3:246-253.

- Paidas MJ, Hossain N. Unexpected postpartum hemorrhage due to an acquired factor VIII inhibitor . Am J Perinatol. 2014 31:645-654

American Society of Hematology. (1). Case Study: 29-Year-Old Female with Postpartum Hemorrhage. Retrieved from https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-postpartum-hemorrhage .

American Society of Hematology. "Case Study: 29-Year-Old Female with Postpartum Hemorrhage." Hematology.org. https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-postpartum-hemorrhage (label-accessed May 25, 2024).

"American Society of Hematology." Case Study: 29-Year-Old Female with Postpartum Hemorrhage, 25 May. 2024 , https://www.hematology.org/education/trainees/fellows/case-studies/female-postpartum-hemorrhage .

Citation Manager Formats

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH): Prevention & Management

Nov 17, 2014

870 likes | 1.62k Views

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH): Prevention & Management. Evidence and Action. Objectives. Describe the global mortality burden of PPH Present current evidence and action to prevent PPH Share key evidence and action to manage PPH

Share Presentation

- maternal deaths

- pph prevention

- severe pph 7

- emerging pph prevention innovations

Presentation Transcript

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH): Prevention & Management Evidence and Action

Objectives • Describe the global mortality burden of PPH • Present current evidence and action to prevent PPH • Share key evidence and action to manage PPH • Discuss key elements in a comprehensive program to reduce deaths from PPH

PPH: Leading Cause of Maternal Mortality • Hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal deaths • 35% of global maternal deaths • estimated 132,000 maternal deaths • 14 million women in developing countries experience PPH—26 women every minute Sources: Khan et al., 2006; POPPHI, 2009; Taking Stock of Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival, 2000–2010 Decade Report

Other direct causes include embolism, ectopic pregnancy, anesthesia-related. Indirect causes include: malaria, heart disease. Source: Adapted from " WHO Analysis of causes of maternal deaths: A systematic review.” The Lancet, vol 367, April 1, 2006.

Maternal & Newborn Health: Scope of Problem • 180–200 million pregnancies per year • 75 million unwanted pregnancies • 50 million induced abortions • 20 million unsafe abortions (same as above) • 342,900 maternal deaths (2008) • 1 maternal death = 30 maternal morbidities • 3 million neonatal deaths (first week of life) • 3 million stillbirths Source: Hogan et al., 2010

Where is Motherhood Less Safe? Deaths of Women from Pregnancy and Childbirth: 99% in developing world World Map in Proportion to Maternal Mortality Source: worldmapper.org

What is PPH? • Blood loss >500mL in the first 24 hours after delivery • Severe PPH is loss of 1000mL or more. • Accurately quantifying blood loss is difficult in most clinical or home settings. • Many severely anemic women cannot tolerate even 500 mL blood loss Graphic credit: ??? Source: Making Pregnancy Safer, through promoting Evidence-based Care, Global Health Council Technical Report, 2002

Incidence of PPH Source: Goudar, Eldavitch, Bellad, 2003

Why Do Women Die From Postpartum Hemorrhage? • We cannot predict who will get PPH. • Almost 50% of women deliver without a skilled birth attendant (SBA). • 50% of maternal deaths occur in the first 24 hours following birth, mostly due to PPH • PPH can kill in as little as 2 hours • Anemia increases the risk of dying from PPH • Timely referral and transport to facilities are often not available or affordable. • Emergency obstetric care is available to less than 20% of women. Source: Taking Stock of Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival, 2000–2010 Decade Report

Prevention Management What Can Be Done? Photo credit: Lauren Goldsmith Photo credit: ??? POPPHI Source: World Health Organization, IMPAC: MCPC 2003

PPH Prevention • In the facility: Active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL) • During deliveries with a skilled provider • Prevents immediate PPH • Associated with almost 60% reduction in PPH occurrence • In the home/community: Misoprostol • During home births without a skilled provider • Community-based counseling and distribution of misoprostol Source: Begley et al., 2010, WHO Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage, 2007

PPH Prevention & Management

Risk of PPH Source: Prendiville et al., BMJ 1988. Villar et al., 2002

Active vs. Expectant Management of Third Stage 4 studies 4,829 women Source: Begley et al., Cochrane Review 2010

Active Management of the Third Stage of Labor (AMTSL) • Administration of a uterotonic agent within one minute after the baby is born (oxytocin is the uterotonic of choice); • Controlled cord traction while supporting and stabilizing the uterus by applying counter traction; • Uterine massage after delivery of the placenta. Source: AMTSL: A Demonstration, Jhpiego, 2005

AMTSL • More effective than physiologic management • 60% decrease in PPH and severe PPH • Decreased need for blood transfusion • Decreased anemia (<9 g/dl) • Uterotonic agent = most effective component • Choice depends on cost, stability, safety, side effects, type of birth attendant, cold chain availability Source: WHO guidelines for the management of postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta, 2009

Choice of Uterotonic Drug • Oxytocin preferred • Fast-acting, inexpensive, no contraindications for use in the third stage of labor, relatively few side effects • Requires refrigeration to maintain potency, requires injection (safety) • Misoprostol • Does not require refrigeration or injection, no contraindications for use in the third stage of labor • Common side effects include shivering and elevated temperature, is less effective than oxytocin Source: WHO guidelines for the management of postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta, 2009

Choice of Uterotonics Source: IMPAC, MCPC 2006, Hofmeyr et al., 2009

More Evidence • Double-blind placebo controlled WHO multi-center RCT: Oxytocin vs. Misoprostol in hospital1 • 8 countries • Oxytocin (n = 9266); Misoprostol (n = 9264) • Severe PPH (1000cc): 3% vs. 4% • Misoprostol—higher incidence of shivering • Conclusion: Oxytocin preferred over Misoprostol • Double blind placebo controlled RCT in rural Guinea Bissau: Misoprostol vs. Placebo • Misoprostol alone reduces severe PPH (1000mls+) 11% vs. 17% RR 0.66 (0.44–0.98) Source: Gulmezoglu, et al., Lancet 2001, Høj BMJ 2005

Misoprostol: Evidence • Clinical demonstration study1 • Oral Misoprostol reduced PPH incidence to 6% • Double-blind placebo controlled study2 • Oral Misoprostol reduced need for treatment of PPH from 8.4% 2.8% • Rectal Misoprostol vs. Syntometrin for 3rd stage3 • Similar reduction in length of 3rd stage, postpartum blood loss and postpartum hemoglobin; Higher BP with Syntometrin • Oral Misoprostol vs. Placebo4 • PPH: 7% vs. 15% • Need for therapeutic Oxytocin: 16% vs. 38% Source: 1: O’Brien, 1997; 2: Hofmeyr, 1998; 3: Bamigboye, 1998; 4: Surbek, 1999

A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial of Oral Misoprostol 600 mcg for Prevention of PPH at Four Primary Health Center Areas of Belgaum District, Karnataka India Source: Derman et al., Lancet 2006

Misoprostol at Home Births: 2006 • Oral misoprostol can be delivered with efficacy and feasibility in a rural home delivery setting. • Reduced acute PPH by almost 50% (compared to placebo) • Associated with an 80% reduction in acute severe PPH Source: Derman et al., 2006

Blood Loss Distribution 95th Percentile M: 500 ml P: 800 ml Source: Derman et al, 2006

Completed programs Indonesia, Gambia, Guinea Bissau New programs underway Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Kenya, Uganda, Afghanistan Feasibility for Misoprostol use at Homebirth • INDONESIA PROGRAM • Safety: No women took medication at wrong time • Acceptability: users said they would recommend it and purchase drug for future births • Feasibility: 94% coverage with PPH prevention method achieved • Effectiveness: • 25% reduction in perceived excessive bleeding OR 0.76 (0.55– 1.05) • 45% reduction in need for referral for PPH 0.53 (0.24–1.12) Source: Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage Study, 2004 Jhpiego

WHO Recommendations for the Prevention of PPH (WHO 2007) 7. In the absence of AMTSL, should uterotonics be used alone for prevention of PPH? Recommendation: • In the absence of AMTSL, a uterotonic drug (oxytocin or misoprostol) should be offeredby a health worker trained in its use for prevention of PPH (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence) Source: WHO Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage, 2007

Uterotonic in 3rd Stage Reduces PPH Source: WHO Recommendations for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage, 2007

Emerging PPH Prevention Innovations • Oxytocin Uniject™ for simpler dosing and improved infection prevention during AMTSL • Angola study compared Uniject with expectant management • Intervention group experienced significantly decreased PPH (40.4% vs. 8.2%), severe PPH (7.5% vs. 1%) andblood loss (447 vs. 239mL). • Shortened the interval between birth of the baby and delivery of the placenta to less than 10 minutes for 89.4% vs. 5.4% of women in the expectant managment group • No significant difference in manual removal of the placenta between the two groups • Some evidence from Mali • Midwives preferred Uniject over standard injection practices at home births • Uniject simplifies AMTSL practice significantly to expand uterotonic coverage and allow task-shifting to auxiliary nurse midwives Photo credit: PATH • Sources: Strand RT, et al., ActaObstetGynecol Scand. 2005; Tsu VD et al., 2003

PPH Management: A Comprehensive Approach Source: WHO handbook: Monitoring emergency obstetric care 2009

Survey Results: Universal Uterotonic Use • 10 countries surveyed • Use of uterotonic high • Correct use of AMTSL was low: only 0.5 to 32 percent of observed deliveries • Findings suggest that AMTSL was not used at 1.4 million deliveries per year Source: POPPHI, 2009

All SBAs authorized to practice AMTSL and use oxytocin for AMTSL AMTSL integrated into preservice: doctors, nurses, midwives Oxytocin and ergomterine on National Essential Drugs List for PPH prevention and treatment; not misoprostol Ergometrine first line drug 58% of selected facilities have oxytocin in stock Results: Improved Policy Environment to Support Evidence-based Practice—Uganda

Cumulative % coverage of eligible pregnant women Results: Increased Uterotonic Coverage in Afghanistan Source: Sanghvi H et al., 2010

Results: Increased Uterotonic Coverage in Indonesia Uterotonic coverage: Oxytocin or misoprostol tablets Source: Sanghvi, et al., Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage Study, Jhpiego 2004

Results: Increased Uterotonic Coverage in Nepal Estimated total pregnancies—16,000 100% 73% Received miso—11,700 22% 53% Took miso—8,616 SBA Received oxytocic 75% Source: Nepal Family Health Program Technical Brief #11: Community-based Postpartum Hemorrhage Prevention

Results: Increased Attendance with SBA in Indonesia Source: Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage Study, Jhpiego 2004

Results: Reduced PPH Rate in Niger • Promotion of AMTSL, 33 government facilities • Increased AMTSL coverage from 5% to 98% of births • Dropped the PPH rate from 2.5% to 0.2% Source: URC, 2009

Results: Reduced Cases & Costs in Afghanistan • Training TBAs to administer misoprostol to treat PPH, 2 hypothetical cohorts of 10,000 women: • TBA referral after blood loss ≥500 ml • Administer 1,000 μg of misoprostol at blood loss ≥500 ml • Misoprostol strategy could: • Prevent 1647 cases of severe PPH (range: 810–2920) • Save $115,335 in costs of referral, IV therapy and transfusions (range: $13,991–$1,563,593) per 10,000 births. Source: S.E.K. Bradley et al., IJOG, 2006

Results: Anecdotal Mortality Impact • Indonesia: 1 district • Before program (2004): 19 PPH cases; 7 maternal deaths • During program (2005): 8 PPH cases; 2 maternal deaths • Nepal: 1 district • Expected # maternal deaths for the period: 45 • Observed # maternal deaths for the period: 29 • Afghanistan: • Expected # maternal deaths in intervention area: 27 • Actual # maternal deaths: 1 (postpartum eclampsia)

Results: PPH Reduction Modeling • Sub-Saharan Africa • Comprehensive intervention package (health facility strengthening and community-based services) reduces deaths due to PPH or sepsis after delivery by 32%—compared to just health facility strengthening alone (12% reduction) Source: Pagel et al., Lancet 2009

PPH Management: WHO Guidelines • WHO (2009) provides countries with evidence-based guidelines on the safety, quality and usefulness of interventions related to PPH management • These guidelines are focused on facility-based care and PPH management in faciliites with CEmONC capacity. Source: World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage and Retained Placenta. 2009.

Management of PPH • Early detection—rapid management • Severe bleeding after birth is NOT normal • Monitor bleeding regularly during the PP period • Most emergency measures can be managed by a nurse or midwife (who has been trained) • Uterine massage • Administer uterotonics • Bimanual compression • Manual removal of placenta • Suture tears • Uterine/ovarian artery ligation or hysterectomy (by MD) Source: World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage and Retained Placenta. 2009.

Atonic Uterus!First Action Is Massage Uterus

Source: IMPAC MCPC, 2003, Begley et al., 2010 Atonic Uterus (continued)

Manual Removal of Placenta • Wearing HLD gloves, insert hand into vagina along the cord. • Locate edge of placenta and slowly using edge of hand with fingers tightly together detach placenta from placental bed. • Hold on to placenta while providing counter-traction with other hand, and remove it. Source: IMPAC MCPC, 2003

Source: IMPAC MCPC, 2003 Bimanual Compression of the Uterus • Wearing HLD gloves, insert hand into vagina; form fist. • Place fist into anterior fornix and apply pressure against anterior wall of uterus. • With other hand, press deeply into abdomen behind uterus, applying pressure against posterior wall of uterus. • Maintain compression until bleeding is controlled and uterus contracts.

Source: IMPAC MCPC, 2003 Compression of Abdominal Aorta • Apply downward pressure with closed fist over abdominal aorta through abdominal wall (just above umbilicus slightly to patient’s left) • With other hand, palpate femoral pulse to check adequacy of compression • Pulse palpable = inadequate • Pulse not palpable = adequate • Maintain compression until bleeding is controlled

Emerging PPH Management Innovations • Use of misoprostol for treatment of PPH that occurs at home • A non-pneumatic anti-shock garment (NASG) to stabilize and prevent/treat shock during transport and management of PPH • Condom tamponade to treat PPH at facilities Source: Georgiou et al., 2009, IMPAC MCPC 2003, Ojengbede et al., 2011

Misoprostol for PPH Treatment in Home A 2005 study in Kigoma, Tanzania demonstrated that: • Traditional birth attendants (TBAs) can correctly diagnose and treat PPH with misoprostol after home births. • Only 2% of women in the intervention area (compared to 19% in the control group) were referred for further PPH treatment. • Of those referred, only 1% from the intervention area but 95% from the non-intervention area needed additional PPH treatment. Source: Prata N, et al., Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005

Treatment with Misoprostol vs. Oxytocin A study of PPH treatment options compared misoprostol (800 μg sublingual) with intravenous oxytocin (40 IU) to treat PPH in women who were not exposed to oxytocin prophalactically in three countries: • In both groups over 90% of women had active bleeding was controlled within 20 minutes (90% misoprostol, 96% oxytocin) • Oxytocin more effective at reducing median additional blood loss • Women receiving misoprostol more frequently needed additional uterotonic drugs or blood transfusion and experienced shivering and fever • Conclusion: Intravenous oxytocin should be used when available, with misoprostol as treatment alternative when oxytocin is not available. Source: Winikoff B, et al., Lancet. 2010 Jan 16;375(9710): 210–6.

Doing it Right: Technologies that can expedite care for PPH where it occurs Technologies appropriate for peripheral level services, even for homebirth Sources: Tsu, V; Coffey, P. BJOG 2009, Carroli, G et al., 2001

PPH Intervention: Anti-shock Garment • The Non-pneumatic Anti-Shock Garment (NASG) applies circumferential counter pressure to the lower body, legs, pelvis and stomach with pressure limits • Study among 1442 women in Egypt and Nigeria • Use of the NASG reduced median blood loss (from 400 mL in the pre-intervention phase to 200 mL) • Halved emergency hysterectomies (8.9% to 4.0%) • Decreased mortality (from 6.3% to 3.5%). Source: Miller S, et al,. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2010, 10:64.

- More by User

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) and abnormalities of the Third Stage

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH) and abnormalities of the Third Stage. Sept 12 – Dr. Z. Malewski. Definition. Excessive bleeding from the genital tract after the birth of the child Conventionally defined as a loss of more than 500ml of blood

1.41k views • 11 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Dr. Yasir Katib MB BS, FRCSC. Postpartum Haemorrhage. Introduction Risk Factors Prevention Treatment Pelvic Haematoma Umbrella Pack Uterine Inversion. PPH - Introduction. Acute blood loss – most common cause of hypotension in obstetrics

1.26k views • 31 slides

Postpartum Hypopituitarism Overt Diabetes Insipidus after Massive Postpartum Hemorrhage

. A 39-year-old lady delivered a normal term male infant weighting 3500g, about 3 hours ago without any instrument and uterine pressure. However, massive vaginal bleeding occurred one hour after this delivery. Oxytocin and methylergonovin were prescribed, but in vain. . . Massive

481 views • 36 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. HEE HEE That’s the only fake blood I could manage!!! Too messy. Jessi Goldstein MD MCH Fellow September 7, 2011. Objectives. We will discuss: Prevention of PPH. Causes of PPH. Initial and secondary interventions in PPH in both vaginal and Cesarean delivery.

1.04k views • 33 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage(PPH)

Postpartum Hemorrhage(PPH). 产后出血 林建华. Major causes of death for pregnancy women ( maternal mortality). Postpartum hemorrhage ( 28%) heart diseases pregnancy-induced hypertension (or Amniotic fluid embolism ) infection. Definition of PPH.

1.32k views • 33 slides

Third Trimester Bleeding, Postpartum Hemorrhage, Shock Management

1.16k views • 46 slides

Routine postpartum care for the woman Name of presenter: Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage Initiative (POPPHI) Proj

Routine postpartum care for the woman Name of presenter: Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage Initiative (POPPHI) Project BASICS. By the end of this session, participants will be able to: Describe essential care to provide to the postpartum woman.

1.04k views • 37 slides

POSTPARTUM MANAGEMENT

POSTPARTUM MANAGEMENT. Out Line:. Introduction of post partum care Physical and psychosocial post partum care Examples of physical &psychosocial midwifery diagnosis in the post partum care Expected out comes for post partum care Physiological needs during post partum

1.57k views • 88 slides

Misoprostol for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage

Misoprostol for the Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Lisa J. Thomas, MD, FACOG Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Misoprostol . Background PGE1, heat stable, inexpensive Indications, Dosage, and Routes Abortion, Incomplete Abortion, Induction of Labor

491 views • 8 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Postpartum Hemorrhage. รองศาสตราจารย์วราภรณ์ เชื้ออินทร์ ภาควิชาวิสัญญีวิทยา คณะแพทยศาสตร์ มหาวิทยาลัยขอนแก่น. การประชุมวิชาการวิสัญญีวิทยามอ.-มข.-มช. ครั้งที่ 3 17 กรกฎาคม 2551 ณ. รร.ป่าตอง รีสอร์ท จ.ภูเก็ต.

1.03k views • 22 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage . Obsterics & Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University Weirong Gu. Postpartum Hemorrhage(PPH). Blood loss in excess of 500 ml following birth within the first 24 hours of delivery Serious intrapartum complication

3.79k views • 58 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Learning Objectives. Define and differentiate between early and late PPH. Identify causes and risk factors of PPH. Identify symptoms and signs of PPH and list the laboratory investigations.

1.87k views • 47 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Dr.Suresh Babu Chaduvula Professor Dept. of Obstetrics & Gynecology College of Medicine, Abha , KKU, Saudi Arabia. POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE [ PPH ]. Definition:

1.54k views • 34 slides

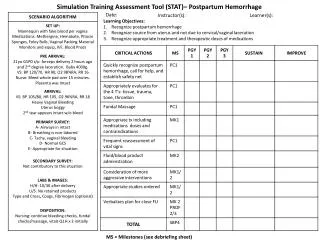

Simulation Training Assessment Tool (STAT )– Postpartum Hemorrhage

Simulation Training Assessment Tool (STAT )– Postpartum Hemorrhage. Learning Objectives: Recognize postpartum hemorrhage Recognize source from uterus and not due to cervical/vaginal laceration Recognize appropriate treatment and therapeutic doses of medications. Date: . Instructor(s): .

456 views • 1 slides

POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE

POSTPARTUM HEMORRHAGE. OBJECTIVES. To understand the importance of prompt and appropriate management in saving lives from PPH Define PPH List the causes and risk factors for PPH Discuss the steps taken in managing PPH. Recognizing Postpartum Hemorrhage. Bleeding >500 ml after childbirth

2.02k views • 18 slides

Scaling Up Misoprostol for Community-Based Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage in Bangladesh

Scaling Up Misoprostol for Community-Based Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage in Bangladesh Dr. Tapash Ranjan Das PM (MCH) & Deputy Director (MCH), DGFP & Dr. Abu Jamil Faisel Project Director, Mayer Hashi project (an Associate Award of the RESPOND project) &

269 views • 11 slides

Third Trimester Bleeding, Postpartum Hemorrhage, & Shock Management

Third Trimester Bleeding, Postpartum Hemorrhage, & Shock Management. UNC School of Medicine Obstetrics and Gynecology Clerkship Case Based Seminar Series. Objectives for Third Trimester Bleeding. List the causes of third trimester bleeding

887 views • 46 slides

Antepartum and Postpartum Hemorrhage

Antepartum and Postpartum Hemorrhage. Dr. Megha Jain. University College of Medical Sciences & GTB Hospital, Delhi. email: [email protected]. www.anaesthesia.co.in. Antepartum hemorrhage. Bleeding from or into genital tract after 28 th week of gestation.

1.89k views • 36 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Dr.B Khani MD. Postpartum Hemorrhage. EBL > 500 cc 10% of deliveries If within 24 hrs. pp = 1 pp hemorrhage If 24 hrs. - 6 wks. pp = 2 pp hemorrhage Causes uterine atony – genital trauma retained placenta – placenta accreta uterine inversion. Uterine Atony.

926 views • 12 slides

Prevention and Management of TURP-Related Hemorrhage

Dr. Abdullah Ahmad Ghazi (R5) KSMC 8 May 2012. Prevention and Management of TURP-Related Hemorrhage. TURP gold standard in BPH Using of A-Cog & A-Plt is increasing. 4% on A-Cog 37% on A-plt. Introduction. The most common perioperative complication in TURP is hemorrhage.

668 views • 32 slides

Postpartum Hemorrhage. Christopher R. Graber, MD Salina Women’s Clinic 21 Feb 2012. Overview. Background Etiology of postpartum hemorrhage Primary Secondary Risk factors Evaluation and management Medical Surgical. Background. Severe bleeding is #1 worldwide cause of maternal death

702 views • 19 slides

Reducing Maternal Mortality Due to Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH)

Reducing Maternal Mortality Due to Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH). Objectives. Present PPH as a public health priority Define interventions available for PPH prevention and management Share country experiences and expected results. What Is Safe Motherhood?.

640 views • 34 slides

NurseStudy.Net

Nursing Education Site

Postpartum Hemorrhage Nursing Diagnosis and Nursing Care Plan

Last updated on April 29th, 2023 at 11:45 pm

Postpartum Hemorrhage Nursing Care Plans Diagnosis and Interventions

Postpartum Hemorrhage NCLEX Review and Nursing Care Plans

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a medical emergency that involves the abnormal or excessive vaginal bleeding of the mother after the birth of her baby.

It is important to note that vaginal bleeding called lochia is normally heavy from just after delivery until the next few hours and may not stop until the next few days.

The color of blood will usually change from bright red to brown over a couple of weeks. The full stoppage of lochia normally occurs no more than 12 weeks after delivery.

However, in postpartum hemorrhage there is either a heavy vaginal bleeding of at least 500 mL in the first 24 hours of delivery or between 23 hours and 12 weeks of delivery.

Types of Lochia

Postpartum hemorrhage may involve excessive bleeding and abnormality of lochia or postpartum vaginal discharge. It is especially important to take note of the duration of lochia rubra to help in the diagnosis of PPH. The following are the normal characteristics of the types or stages of lochia:

- Lochia rubra – refers to the first vaginal discharge; rubra means red in color; usually happens from Day 1 to Day 5 after birth

- Lochia serosa – the vaginal discharge appears either brownish or pinkish; typically occurs until Day 10 after birth

- Lochia alba – the vaginal discharge appears whitish or yellowish; typically happens from the 2 nd week to the 6 th week after birth, but may also extend to 12 weeks postpartum

Types of Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Primary PPH – occurs when the mother loses at least 500 mL or more of blood within the first 24 hours of delivering the baby.

- Major Primary PPH – losing 500 mL to 1000 mL of blood

- Minor Primary PPH – losing more than 1000 mL of blood

- Secondary PPH – occurs when the mother has heavy or abnormal vaginal bleeding between 24 hours and 12 weeks of delivering the baby.

Signs and Symptoms of Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Uncontrolled bleeding

- Hypotension – decreased blood pressure

- Tachycardia – increased heart rate

- Anemia – decrease in the red blood cell count or hemoglobin level

- Edema or hematoma – swelling and pain in or around the vaginal area

- Fatigue – extreme tiredness

The patient should also be educated on the following warning signs that would indicate the need to inform their healthcare provider either during hospital stay or after discharge:

- Excessive or increased vaginal bleeding – if the patient needs a new sanitary pad after an hour, or if she passes large blood clots

- Blurry vision or other visual disturbances

- Light-headedness or dizziness

- New or worsening stomach pain

- Tachycardia

Causes and Risk Factors of Postpartum Hemorrhage

The 4 T’s is a mnemonic that can be used to remember the 4 common causes of postpartum hemorrhage:

- Tone – uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH; overstretched uterus may cause a soft and boggy tone

- Trauma – rupture, inversion, hematoma, and/or laceration

- Tissue – retained or invasive placenta

- Thrombin – coagulopathy; bleeding disorders or blood clotting problems

The following are risk factors of postpartum hemorrhage:

A. Before Delivery

- Placenta previa – a condition wherein the placenta is situated low near the neck of the uterus

- Abruptio placentae – a condition wherein the placenta separates from the uterus earlier than expected

- Multiple pregnancies – carrying twins or more

- History of postpartum hemorrhage

- Pre-eclampsia – high blood pressure

- Obesity or having a BMI of greater than 35

- Thrombocytopenia or other blood clotting problems

- On anticoagulant therapy

B. After Delivery

- Delivery by Cesarean section

- Forceps delivery

- Induction of labor

- Delayed delivery of placenta or retained placenta – not passing the placenta within the hour after birth of the baby

- Tear in the perineum (lacerations) or episiotomy

- Fetal macrosomia – having a baby that weighs more than 9 lbs or 4 kg

- Hyperthermia during labor

- Having had a long labor – more than 12 hours

- Age of the mother – having the first baby at age 40 years or above

- Use of general anesthetic during delivery

Complications of Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Hypovolemic shock

- Failure of major organs, such as the lungs and kidneys

- Postpartum fatigue

Diagnosis of Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Measurement of blood loss – PPH is defined as blood loss of more than 500 mL in the first 24 hours post delivery

- Blood tests – include full blood count (particularly hemoglobin and hematocrit), clotting factors, and factor essays

- Pelvic exam – pregnant women who are at risk for PPH will undergo pelvic exam which checks the vagina, uterus, and cervix

- Imaging – ultrasound is the first imaging choice to visualize the baby and the pelvic organs

Prevention of Postpartum Hemorrhage

The following measures can be undertaken to prevent the likelihood of postpartum hemorrhage:

- Early recognition of the risk for PPH. Stopping or reducing anticoagulants, oral iron supplementation, coagulation tests, and regular antenatal check-ups are helpful in preventing PPH.

Treatment for Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Medications. Several medications may be prescribed to treat PPH:

- Uterotonic agents – utilized to prevent or control PPH. Oxytocin is the first-line prevention and treatment for PPH. It is used to decrease the blood flow through the uterus after the delivery of the baby.

- Adjuvant therapies – anti-bleeding drugs can be administered within the first 3 hours of the start of PPH

- Antibiotics – may be required if a bacterial infection has caused or contributed to PPH based on the culture results of the lochia

- Intravenous fluid replacement

- Uterine massage

- Transfusion – low hemoglobin /hematocrit level and excessive blood loss may require transfusion of blood and plasma products.

- Application of pressure on labial or perineal lacerations

- Episiotomy Repair – timely repair of lacerations and episiotomy is important in controlling PPH

- Reduction of uterine inversion – the Johnson method is a manual procedure wherein the protruding uterus is returned in the normal position by pushing it inside toward the direction of the umbilicus

- Manual removal of retained placental tissues

- Surgery- hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) or laparatomy may be needed if the other treatments are not effective in stopping PPH

Nursing Diagnosis for Postpartum Hemorrhage

Nursing care plan for postpartum hemorrhage 1.

Nursing Diagnosis: Fluid Volume Deficit related to blood volume loss secondary to postpartum hemorrhage as evidenced by lochia rubia of 500 mL in the first 24 hours post-delivery, decrease in red blood cell count/ hemoglobin/ hematocrit levels, skin pallor, heart rate of 120 bpm, blood pressure level of 85/50, and lightheadedness

Desired Outcome: The patient will have a lochia flow of less than one saturated pad per hour, a hemoglobin (HB) level of over 100, blood pressure and heart rate levels within normal range, full level of consciousness, and normal skin color

Nursing Care Plan for Postpartum Hemorrhage 2

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Bleeding related to C-section delivery of the baby

Desired Outcome: To prevent any bleeding episode after C-section delivery of the baby.

Nursing Care Plan for Postpartum Hemorrhage 3

Ineffective Tissue Perfusion

Diagnosis: Ineffective Tissue Perfusion related to hypovolemia secondary to postpartum hemorrhage as demonstrated by reduced arterial pulsations, cold and pale color skin at the extremities, increased perspiration, lesser capillary refill, reduced milk production, changes in vital signs, and altered neurologic status.

Desired Outcomes:

- The patient will exhibit vital signs within the normal range.

- The patient laboratory result of arterial blood gases, hematocrit, and hemoglobin levels are acceptable findings.

- The patient will show signs of desired hormonal changes such as a sufficient supply of breastmilk for lactation, and resumption of normal menstruation cycle.

Nursing Care Plan for Postpartum Hemorrhage 4

Risk for Infection

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Infection related to the stasis of body fluids and traumatized tissues secondary to postpartum hemorrhage.

- The patient will express an understanding of the causative, and risk factors.

- The patient’s vital signs will be maintained within normal ranges.

- The patient’s will exhibit lochia free from foul smelling odor.

- The patient’s laborataory values will improve and within normal levels.

Nursing Care Plan for Postpartum Hemorrhage 5

Risk for Impaired Attachment

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Impaired Attachment related to anxiety associated with the parent role secondary to postpartum hemorrhage.

- The patient will verbalize a feeling of happiness with the role as a parent.

- The patient will take the duty for the physical and emotional well-being of the infant.

- The patient will show proper behavior related to positive attachment to the infant.

- The patient will participate in mutually satisfying contact with the child.

More Postpartum Hemorrhage Nursing Diagnosis

- Risk for Shock (Hypovolemic)

- Risk for Injury

- Ineffective Coping

Nursing References

Ackley, B. J., Ladwig, G. B., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M. R., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnoses handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Gulanick, M., & Myers, J. L. (2022). Nursing care plans: Diagnoses, interventions, & outcomes . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Ignatavicius, D. D., Workman, M. L., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2020). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for interprofessional collaborative care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Silvestri, L. A. (2020). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Disclaimer:

Please follow your facilities guidelines, policies, and procedures.

The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes.

This information is intended to be nursing education and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

Anna Curran. RN, BSN, PHN

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

ANN EVENSEN, MD, JANICE M. ANDERSON, MD, AND PATRICIA FONTAINE, MD, MS

This is an updated version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(7):442-449

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Postpartum hemorrhage is common and can occur in patients without risk factors for hemorrhage. Active management of the third stage of labor should be used routinely to reduce its incidence. Use of oxytocin after delivery of the anterior shoulder is the most important and effective component of this practice. Oxytocin is more effective than misoprostol for prevention and treatment of uterine atony and has fewer adverse effects. Routine episiotomy should be avoided to decrease blood loss and the risk of anal laceration. Appropriate management of postpartum hemorrhage requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. The Four T's mnemonic can be used to identify and address the four most common causes of postpartum hemorrhage (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]). Rapid team-based care minimizes morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage, regardless of cause. Massive transfusion protocols allow for rapid and appropriate response to hemorrhages exceeding 1,500 mL of blood loss. The National Partnership for Maternal Safety has developed an obstetric hemorrhage consensus bundle of 13 patient- and systems-level recommendations to reduce morbidity and mortality from postpartum hemorrhage.

Approximately 3% to 5% of obstetric patients will experience postpartum hemorrhage. 1 Annually, these preventable events are the cause of one-fourth of maternal deaths worldwide and 12% of maternal deaths in the United States. 2 , 3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines early postpartum hemorrhage as at least 1,000 mL total blood loss or loss of blood coinciding with signs and symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after delivery of the fetus or intrapartum loss. 4 , 5 Primary postpartum hemorrhage may occur before delivery of the placenta and up to 24 hours after delivery of the fetus. Complications of postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 1 3 , 6 , 7 ; these range from worsening of common postpartum symptoms such as fatigue and depressed mood, to death from cardiovascular collapse.

This review presents evidence-based recommendations for the prevention of and appropriate response to postpartum hemorrhage and is intended for physicians who provide antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care.

Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 2 . 8 However, 20% of postpartum hemorrhage occurs in women with no risk factors, so physicians must be prepared to manage this condition at every delivery. 9 Strategies for decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with postpartum hemorrhage are listed in Table 3 , 6 , 10 – 14 including the choice to deliver infants in women at high risk of hemorrhage at facilities with immediately available surgical, intensive care, and blood bank services.

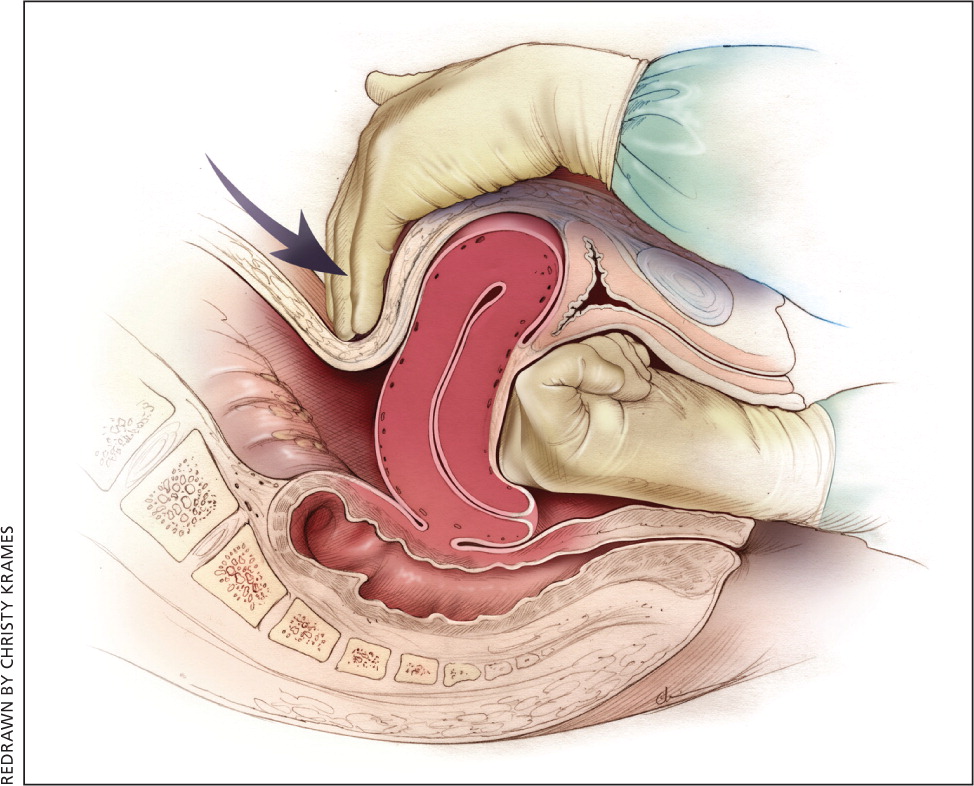

The most effective strategy to prevent postpartum hemorrhage is active management of the third stage of labor (AMTSL). AMTSL also reduces the risk of a postpartum maternal hemoglobin level lower than 9 g per dL (90 g per L) and the need for manual removal of the placenta. 11 Components of this practice include: (1) administering oxytocin (Pitocin) with or soon after the delivery of the anterior shoulder; (2) controlled cord traction (Brandt-Andrews maneuver) to deliver the placenta; and (3) uterine massage after delivery of the placenta. 11 Placental delivery can be achieved using the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which firm traction on the umbilical cord is applied with one hand while the other applies suprapubic counterpressure 15 ( eFigure A ).

The individual components of AMTSL have been evaluated and compared. Based on existing evidence, the most important component is administration of a uterotonic drug, preferably oxytocin. 12 , 16 The number needed to treat to prevent one case of hemorrhage 500 mL or greater is 7 for oxytocin administered after delivery of the fetal anterior shoulder or after delivery of the neonate compared with placebo. 16 The risk of postpartum hemorrhage is also reduced if oxytocin is administered after placental delivery instead of at the time of delivery of the anterior shoulder. 17 Dosing instructions are provided in Table 4 . 6

An alternative to oxytocin is misoprostol (Cytotec), an inexpensive medication that does not require injection and is more effective than placebo in preventing postpartum hemorrhage. 12 However, most studies have shown that oxytocin is superior to misoprostol. 12 , 18 Misoprostol also causes more adverse effects than oxytocin—commonly nausea, diarrhea, and fever within three hours of birth. 12 , 18

The benefits of controlled cord traction and uterine massage in preventing postpartum hemorrhage are less clear, but these strategies may be helpful. 15 , 19 , 20 Controlled cord traction does not prevent severe postpartum hemorrhage, but reduces the incidence of less severe blood loss (500 to 1,000 mL) and reduces the need for manual extraction of the placenta. 21

Diagnosis and Management

Diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage begins with recognition of excessive bleeding and targeted examination to determine its cause ( Figure 1 6 ). Cumulative blood loss should be monitored throughout labor and delivery and postpartum with quantitative measurement, if possible. 22 Although some important sources of blood loss may occur intrapartum (e.g., episiotomy, uterine rupture), most of the fluid expelled during delivery of the infant is urine or amniotic fluid. Quantitative measurement of postpartum bleeding begins immediately after the birth of the infant and entails measuring cumulative blood loss with a calibrated underbuttocks drape, or by weighing blood-soaked pads, sponges, and clots; combined use of these methods is also appropriate for obtaining an accurate measurement. 22 Healthy pregnant women can typically tolerate 500 to 1,000 mL of blood loss without having signs or symptoms. 9 Tachycardia may be the earliest sign of postpartum hemorrhage. Orthostasis, hypotension, nausea, dyspnea, oliguria, and chest pain may indicate hypovolemia from significant hemorrhage. If excess bleeding is diagnosed, the Four T's mnemonic (uterine atony [Tone]; laceration, hematoma, inversion, rupture [Trauma]; retained tissue or invasive placenta [Tissue]; and coagulopathy [Thrombin]) can be used to identify specific causes ( Table 5 6 ). Regardless of the cause of bleeding, physicians should immediately summon additional personnel and begin appropriate emergency hemorrhage protocols.

TONE (UTERINE ATONY)

Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage. 9 Brisk blood flow after delivery of the placenta unresponsive to transabdominal massage should prompt immediate action including bimanual compression of the uterus and use of uterotonic medications ( Table 4 6 ). Massage is performed by placing one hand in the vagina and pushing against the body of the uterus while the other hand compresses the fundus from above through the abdominal wall ( eFigure B ).

Uterotonic agents include oxytocin, ergot alkaloids, and prostaglandins. Oxytocin is the most effective treatment for postpartum hemorrhage, even if already used for labor induction or augmentation or as part of AMTSL. 8 , 23 , 24 The choice of a second-line uterotonic should be based on patient-specific factors such as hypertension, asthma, or use of protease inhibitors. Although it is not a uterotonic, tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) may reduce mortality due to bleeding from postpartum hemorrhage (but not overall mortality) when given within the first three hours and may be considered as an adjuvant therapy. 25 [updated] Table 4 outlines dosages, cautions, contraindications, and common adverse effects of uterotonic medications and tranexamic acid. 6

Lacerations and hematomas due to birth trauma can cause significant blood loss that can be lessened by hemostasis and timely repair. Episiotomy increases the risk of blood loss and anal sphincter tears; this procedure should be avoided unless urgent delivery is necessary and the perineum is thought to be a limiting factor. 26

Vaginal and vulvar hematomas can present as pain or as a change in vital signs disproportionate to the amount of blood loss. Small hematomas can be managed with ice packs, analgesia, and observation. Patients with persistent signs of volume loss despite fluid replacement, as well as those with large (greater than 3 to 4 cm) or enlarging hematomas, require incision and evacuation of the clot. 27 The involved area should be irrigated and hemostasis achieved by ligating bleeding vessels, placing figure-of-eight sutures, and creating a layered closure, or by using any of these methods alone.

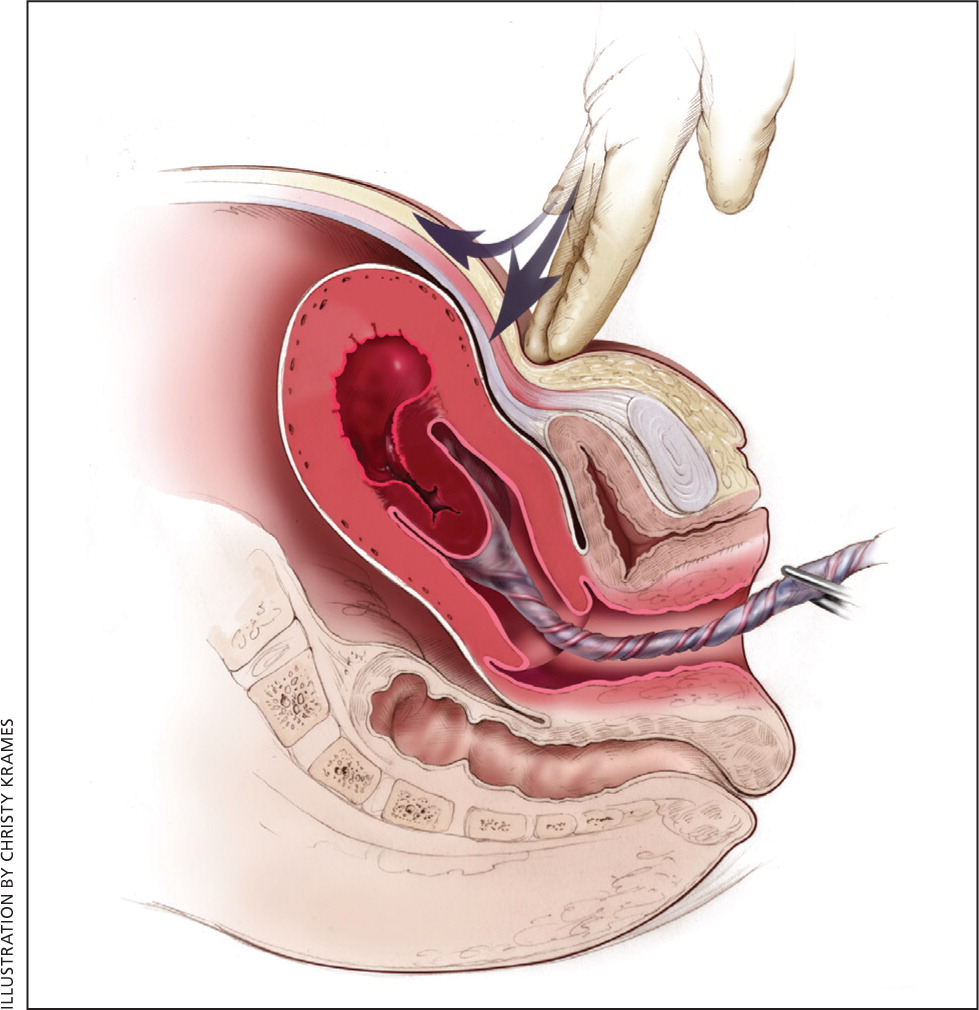

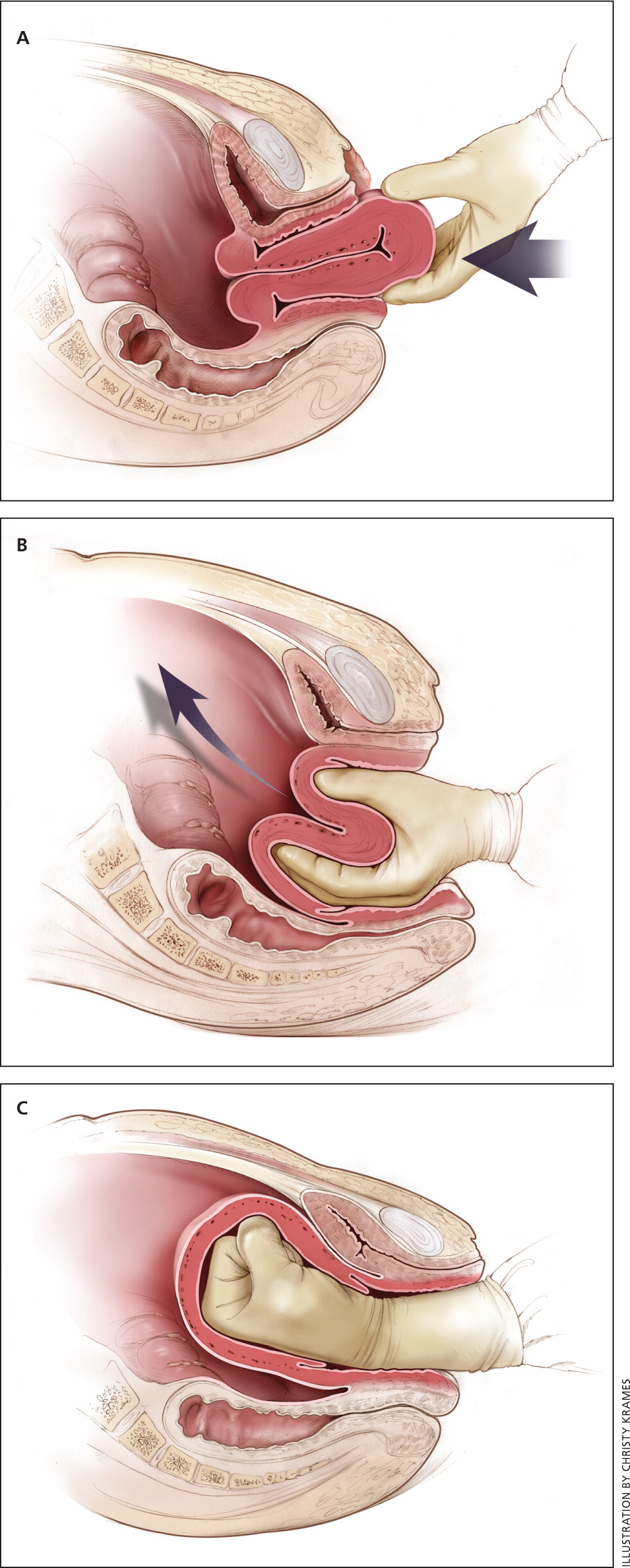

Uterine inversion is rare, occurring in only 0.04% of deliveries, and is a potential cause of postpartum hemorrhage. 27 AMTSL does not appear to increase the incidence of uterine inversion, but invasive placenta does. 27 , 28 The contributions of other conditions such as fundal implantation of the placenta, fundal pressure, and undue cord traction are unclear. 27 The inverted uterus usually appears as a bluish-gray mass protruding from the vagina. Patients with uterine inversion may have signs of shock without excess blood loss. If the placenta is attached, it should be left in place until after reduction to limit hemorrhage. 27 Every attempt should be made to quickly replace the uterus. The Johnson method of reduction begins with grasping the protruding fundus with the palm of the hand, directing the fingers toward the posterior fornix. 27 The uterus is returned to position by lifting it up through the pelvis and into the abdomen ( eFigure C ). Once the uterus is reverted, uterotonic agents can promote uterine tone and prevent recurrence. If initial attempts to replace the uterus fail or contraction of the lower uterine segment (contraction ring) develops, the use of magnesium sulfate, terbutaline, nitroglycerin, or general anesthesia may allow sufficient uterine relaxation for manipulation. 28

Uterine rupture can cause intrapartum and postpartum hemorrhage. 29 Although rare in an unscarred uterus, clinically significant uterine rupture occurs in 0.8% of vaginal births after cesarean delivery via low transverse uterine incision. 30 Induction and augmentation increase the risk of uterine rupture, especially for patients with prior cesarean delivery. 31 Before delivery, the primary sign of uterine rupture is fetal bradycardia. 31 , 32 Other signs and symptoms of uterine rupture are listed in eTable A .

Retained tissue (i.e., placenta, placental fragments, or blood clots) prevents the uterus from contracting enough to achieve optimal tone. Classic signs of placental separation include a small gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and a slight rise of the uterus. The mean time from delivery to placental expulsion is eight to nine minutes. 33 Longer intervals are associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with rates doubling after 10 minutes. 33 Retained placenta (i.e., failure of the placenta to deliver within 30 minutes) occurs in less than 3% of vaginal deliveries. 34 , 35 If the placenta is retained, consider manual removal using appropriate analgesia. 35 Injecting the umbilical vein with saline and oxytocin does not clearly reduce the need for manual removal. 35 – 37 If blunt dissection with the edge of the gloved hand does not reveal the tissue plane between the uterine wall and placenta, invasive placenta should be considered.

Invasive placenta (placenta accreta, increta, or percreta) can cause life-threatening postpartum hemorrhage. 13 , 34 , 35 The incidence has increased with time, mirroring the increase in cesarean deliveries. 13 , 34 In addition to prior cesarean delivery, other risk factors for invasive placenta include placenta previa, advanced maternal age, high parity, and previous invasive placenta. 13 , 34 Treatment of invasive placenta can require hysterectomy or, in select cases, conservative management (i.e., leaving the placenta in place or giving weekly oral methotrexate). 13

THROMBIN (COAGULATION DEFECTS)

Coagulation defects can cause a hemorrhage or be the result of one. These defects should be suspected in patients who have not responded to the usual measures to treat postpartum hemorrhage or who are oozing from puncture sites. A coagulation defect should also be suspected if blood does not clot in bedside receptacles or red-top (no additives) laboratory collection tubes within five to 10 minutes. Coagulation defects may be congenital or acquired ( eTable B ). Evaluation should include a platelet count and measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, fibrin split products, and quantitative d-dimer assay. Physicians should treat the underlying disease process, if known, and support intravascular volume, serially evaluate coagulation status, and replace appropriate blood components using an emergency release protocol to improve response time and decrease risk of dilutional coagulopathy. 7 , 38 , 39 [updated]

Ongoing or Severe Hemorrhage

Significant blood loss from any cause requires immediate resuscitation measures using an interdisciplinary, stage-based team approach. Physicians should perform a primary maternal survey and institute care based on American Heart Association standards and an assessment of blood loss. 14 , 40 Patients should be given oxygen, ventilated as needed, and provided intravenous fluid and blood replacement with normal saline or other crystalloid fluids administered through two large-bore intravenous needles. Fluid replacement volume should initially be given as a bolus infusion and subsequently adjusted based on frequent reevaluation of the patient's vital signs and symptoms. The use of O negative blood may be needed while waiting for type-specific blood.

Elevating the patient's legs will improve venous return. Draining the bladder with a Foley catheter may improve uterine atony and will allow monitoring of urine output. Massive transfusion protocols to decrease the risk of dilutional coagulopathy and other postpartum hemorrhage complications have been established. These protocols typically recommend the use of four units of fresh frozen plasma and one unit of platelets for every four to six units of packed red blood cells used. 7 , 39

Uterus-conserving treatments include uterine packing (plain gauze or gauze soaked with vasopressin, chitosan, or carboprost [Hemabate]), artery ligation, uterine artery embolization, B-lynch compression sutures, and balloon tamponade. 7 , 41 – 43 Balloon tamponade (in which direct pressure is applied to potential bleeding sites via a balloon that is inserted through the vagina and cervix and inflated with sterile water or saline), uterine packing, aortic compression, and nonpneumatic antishock garments may be used to limit bleeding while definitive treatment or transport is arranged. 7 , 41 , 44 Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment in women with severe, intractable hemorrhage.

Follow-up of postpartum hemorrhage includes monitoring for ongoing blood loss and vital signs, assessing for signs of anemia (fatigue, shortness of breath, chest pain, or lactation problems), and debriefing with patients and staff. Many patients experience acute and posttraumatic stress disorders after a traumatic delivery. Individual, trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy can be offered to reduce acute traumatic stress symptoms. 45 Debriefing with staff may identify necessary systems-level changes ( Table 3 ). 6 , 10 – 14

Systems Approach to Prevention and Treatment

Complications of postpartum hemorrhage are common, even in high-resource countries and well-staffed delivery suites. Based on an analysis of systems errors identified in The Joint Commission's 2010 Sentinel Event Alert, the commission recommended that hospitals establish protocols to enable an optimal response to changes in maternal vital signs and clinical condition. These protocols should be tested in drills, and systems problems that interfere with care should be fixed through their continual refinement. 46 In response, The Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care outlined essential steps that delivery units should take to decrease the incidence and severity of postpartum hemorrhage 14 ( Table 3 6 , 10 – 14 ). The creation of a hemorrhage cart with supplies, and the use of huddles, rapid response teams, and massive transfusion protocols are among the recommendations. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO) training can be part of a systems approach to improving patient care. The use of interdisciplinary team training with in situ simulation, available through the ALSO program and from TeamSTEPPS (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety), has been shown to improve perinatal safety. 47 , 48

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Maughan, et al. , 49 and by Anderson and Etches . 50

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term postpartum hemorrhage. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Search dates: October 12, 2015, and January 19, 2016.

This article is one in a series on “Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO),” initially established by Mark Deutchman, MD, Denver, Colo. The coordinator of this series is Larry Leeman, MD, MPH, ALSO Managing Editor, Albuquerque, N.M.

Knight M, Callaghan WM, Berg C, et al. Trends in postpartum hemorrhage in high resource countries: a review and recommendations from the International Postpartum Hemorrhage Collaborative Group. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:55.

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323-e333.

Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Herbst MA, Meyers JA, Hankins GD. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):36.e1-36.e5.

Menard MK, Main EK, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing obstetric data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):150-153.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstetric data definitions (version 1.0). Revitalize. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Departments/Patient-Safety-and-Quality-Improvement/2014reVITALizeObstetricDataDefinitionsV10.pdf . Accessed October 2, 2016.

Evensen A, Anderson J. Chapter J. Postpartum hemorrhage: third stage pregnancy. In: Leeman L, Quinlan J, Dresang LT, eds. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics: Provider Syllabus. 5th ed. Leawood, Kan.: American Academy of Family Physicians; 2014.

Guidelines and Audit Committee of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg52/ . Accessed March 23, 2017. [updated]

Mousa HA, Blum J, Abou El Senoun G, Shakur H, Alfirevic Z. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(2):CD003249.

Magann EF, Evans S, Hutchinson M, Collins R, Howard BC, Morrison JC. Postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal birth: an analysis of risk factors. South Med J. 2005;98(4):419-422.

Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. Obstetric hemorrhage patient safety bundle. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/patient-safety-bundles/obstetric-hemorrhage/ [login required]. Accessed October 16, 2016.

Begley CM, Gyte GML, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(3):CD007412.

Tunçalp Ö, Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM. Prostaglandins for preventing postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(8):CD000494.

Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 529: placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(1):207-211.

Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al.; National Partnership for Maternal Safety; Council on Patient Safety in Women's Health Care. National partnership for maternal safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage [published correction appears in Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):1111]. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(1):155-162.

Deneux-Tharaux C, Sentilhes L, Maillard F, et al. Effect of routine controlled cord traction as part of the active management of the third stage of labour on postpartum haemorrhage: multicentre randomized controlled trial (TRACOR) [published corrections appear in BMJ. 2013;347:f6619 and BMJ. 2013;346:f2542]. BMJ. 2013;346:f1541.

Westhoff G, Cotter AM, Tolosa JE. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour to prevent postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(10):CD001808.

Soltani H, Hutchon DR, Poulose TA. Timing of prophylactic uterotonics for the third stage of labour after vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(8):CD006173.

Bellad MB, Tara D, Ganachari MS, et al. Prevention of postpartum haemorrhage with sublingual misoprostol or oxytocin: a double-blind randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2012;119(8):975-982 , discussion 982–986.

Hofmeyr GJ, Abdel-Aleem H, Abdel-Aleem MA. Uterine massage for preventing postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013(7):CD006431.

Chen M, Chang Q, Duan T, He J, Zhang L, Liu X. Uterine massage to reduce blood loss after vaginal delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):290-295.

Hofmeyr GJ, Mshweshwe NT, Gülmezoglu AM. Controlled cord traction for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(1):CD008020.

Quantification of blood loss: AWHONN practice brief number 1. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2015;44(1):158-160.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Postpartum hemorrhage from vaginal delivery. Patient safety checklist no. 10. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:1151-1152.

Sosa CG, Althabe F, Belizan JM, Buekens P. Use of oxytocin during early stages of labor and its effect on active management of third stage of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(3):238.e1-238.e5.

WOMAN Trial Collaborators.

Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(1):CD000081.

You WB, Zahn CM. Postpartum hemorrhage: abnormally adherent placenta, uterine inversion, and puerperal hematomas. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(1):184-197.

Baskett TF. Acute uterine inversion: a review of 40 cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24(12):953-956.

Guiliano M, Closset E, Therby D, LeGoueff F, Deruelle P, Subtil D. Signs, symptoms and complications of complete and partial uterine ruptures during pregnancy and delivery. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;179:130-134.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development conference statement: vaginal birth after cesarean: new insights March 8–10, 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1279-1295.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 115: vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):450-463.

Guise JM, McDonagh MS, Osterweil P, Nygren P, Chan BK, Helfand M. Systematic review of the incidence and consequences of uterine rupture in women with previous caesarean section. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):19-25.

Magann EF, Evans S, Chauhan SP, Lanneau G, Fisk AD, Morrison JC. The length of the third stage of labor and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):290-293.

Wu S, Kocherginsky M, Hibbard JU. Abnormal placentation: twenty-year analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1458-1461.

Weeks AD. The retained placenta. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(6):1103-1117.

Nardin JM, Weeks A, Carroli G. Umbilical vein injection for management of retained placenta. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(5):CD001337.

Güngördük K, Asicioglu O, Besimoglu B, et al. Using intraumbilical vein injection of oxytocin in routine practice with active management of the third stage of labor: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):619-624.

Cunningham FG, Nelson DB. Disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(5):999-1011.

Lyndon A, Lagrew D, Shields LE, Main E, Cape V. Improving health care response to obstetric hemorrhage. (California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative Toolkit to Transform Maternity Care). Developed under contract #11–10006 with the California Department of Public Health; Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division; Published by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative, 3/17/15.

Neumar RW, Shuster M, Callaway CW, et al. Part 1: Executive summary: 2015 American Heart Association guidelines update for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 suppl 2):S315-S367.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for the management of postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44171/1/9789241598514_eng.pdf . Accessed September 29, 2016.

Grönvall M, Tikkanen M, Tallberg E, Paavonen J, Stefanovic V. Use of Bakri balloon tamponade in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage: a series of 50 cases from a tertiary teaching hospital. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(4):433-438.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists number 76, October 2006: postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039-1047.

Miller S, Martin HB, Morris JL. Anti-shock garment in postpartum haemorrhage. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;22(6):1057-1074.

Roberts NP, Kitchiner NJ, Kenardy J, Bisson JI. Early psychological interventions to treat acute traumatic stress symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(3):CD007944.

Preventing maternal death. Jt Comm Perspect. 2010;30(3):7-9.

Riley W, Davis S, Miller K, Hansen H, Sainfort F, Sweet R. Didactic and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(8):357-364.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Patient Safety and Quality Improvement. Committee opinion no. 590: preparing for clinical emergencies in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(3):722-725.

Maughan K, Heim SW, Galazka SS. Preventing postpartum hemorrhage: managing the third stage of labor. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(6):1025-1028.

Anderson JM, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(6):875-882.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2017 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Diagnosis and management of postpartum hemorrhage and intrapartum asphyxia in a quality improvement initiative using nurse-mentoring and simulation in Bihar, India

Rakesh ghosh.

1 Institute for Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States of America

Hilary Spindler

Melissa c. morgan.

2 Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States of America

3 Maternal, Adolescent, Reproductive, and Child Health Centre, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

Susanna R. Cohen

4 College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States of America

Nilophor Begum

5 CARE India, Patna, Bihar, India

Tanmay Mahapatra

Dilys m. walker.

6 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Services, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States of America

Associated Data

Minimal data set is within the paper or Supporting Information files.

In the state of Bihar, India a multi-faceted quality improvement nurse-mentoring program was implemented to improve provider skills in normal and complicated deliveries. The objective of this analysis was to examine changes in diagnosis and management of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) of the mother and intrapartum asphyxia of the infant in primary care facilities in Bihar, during the program.

During the program, mentor pairs visited each facility for one week, covering four facilities over a four-week period and returned for subsequent week-long visits once every month for seven to nine consecutive months. Between- and within-facility comparisons were made using a quasi-experimental and a longitudinal design over time, respectively, to measure change due to the intervention. The proportions of PPH and intrapartum asphyxia among all births as well as the proportions of PPH and intrapartum asphyxia cases that were effectively managed were examined. Zero-inflated negative binomial models and marginal structural methodology were used to assess change in diagnosis and management of complications after accounting for clustering of deliveries within facilities as well as time varying confounding.

This analysis included 55,938 deliveries from 320 facilities. About 2% of all deliveries, were complicated with PPH and 3% with intrapartum asphyxia. Between-facility comparisons across phases demonstrated diagnosis was always higher in the final week of intervention (PPH: 2.5–5.4%, intrapartum asphyxia: 4.2–5.6%) relative to the first week (PPH: 1.2–2.1%, intrapartum asphyxia: 0.7–3.3%). Within-facility comparisons showed PPH diagnosis increased from week 1 through 5 (from 1.6% to 4.4%), after which it decreased through week 7 (3.1%). A similar trend was observed for intrapartum asphyxia. For both outcomes, the proportion of diagnosed cases where selected evidence-based practices were used for management either remained stable or increased over time.

Conclusions

The nurse-mentoring program appears to have built providers’ capacity to identify PPH and intrapartum asphyxia cases but diagnosis levels are still not on par with levels observed in Southeast Asia and globally.

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 275,000 maternal deaths and 2.7 million neonatal deaths occur annually, a quarter of which occurs in India [ 1 , 2 ]. Hemorrhage, the leading cause of maternal mortality accounted for 27% of all deaths globally and 38% in India [ 3 , 4 ]. Intrapartum asphyxia is the second important cause, accounting for 11% and 19%, of all neonatal deaths globally and in India, respectively [ 2 , 5 ]. Further, a third of all neonatal deaths globally [ 6 ] and in India [ 7 ] occur within 24-hours of birth. Thus, interventions aimed at improving intrapartum and immediate postnatal care could significantly impact neonatal and maternal survival.

A critical step towards preventing maternal and neonatal mortality is timely diagnosis and management of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) and intrapartum asphyxia, which remains largely underdiagnosed in primary care facilities in India [ 8 , 9 ]. Skilled health personnel, who attend 71% of all deliveries worldwide and 79% in India, need to be able to identify and manage such complications [ 10 , 11 ]. In fact, estimates suggest that basic neonatal resuscitation (NR) including drying and stimulating, repositioning, clearing airways and positive pressure ventilation (PPV), could prevent about 30% of intrapartum-related neonatal deaths [ 12 ].

The Government of India initiated a program in 2005 to increase institutional deliveries with the expectation that skilled attendants are better able to identify and manage maternal and neonatal complications, thereby saving lives [ 13 ]. However, in the state of Bihar, where the population is predominantly rural [ 14 ], despite an increase in institutional delivery, concomitant reduction in neonatal mortality was not observed [ 2 ], suggesting sub-optimal quality of care in these facilities. Indeed, studies from Bihar report that providers lack essential clinical skills, and facilities lack trained staff and adequate infrastructure [ 15 , 16 ].

A nurse-mentoring program including integrated simulation training targeting individual and team performance was implemented in Bihar with the overall aim of improving the quality of facility-based care [ 17 ]. Previous reports have demonstrated effectiveness of this intervention, implemented on a smaller scale, to increase use of evidence-based practices (EBP) for both intrapartum and neonatal care among normal deliveries [ 18 , 19 ]. We hypothesized that the nurse-mentoring program also built the providers’ capacity to identify and manage maternal and neonatal complications. The objective of this analysis was to examine changes in diagnosis and management of PPH and intrapartum asphyxia during a mobile nurse-mentoring program in 320 Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (BEmONC) facilities in Bihar, India. The SQUIRE 2.0 guidelines to report quality improvement studies were used [ 20 ].

In 2011, CARE India, a non-governmental organization, collaborated with the Government of Bihar to implement a pilot program in eight districts [ 18 ]. Promising results from the pilot phase [ 18 , 19 ] led to scale-up to all 38 districts in Bihar, covering an estimated 110 million population, as Apatkaleen Matritva evam Navjat Tatparta (AMANAT), meaning ‘emergency obstetrical and neonatal readiness’ in Hindi. AMANAT was a multi-faceted quality improvement nurse-mentoring program to reduce maternal and neonatal mortality by improving provider skills in normal and complicated deliveries. Other key components included support for positive changes in infrastructure and management, infection control, hazardous waste disposal, and creating and maintaining a newborn care corner in public health facilities.

The AMANAT program was implemented in four phases between May 2015 and January 2017 at 320 high volume, BEmONC facilities at the primary care level (80 facilities per phase (P), P1 –May to October 2015, P2 –September 2015 to May 2016, P3 –Nov 2015 to June 2016 and P4 –June 2016 to Jan 2017). Due to administrative limitations, only facilities with adequate readiness in terms of infrastructure and management were included. In Bihar, BEmONC facilities serve twice as many people than federally mandated, often with limited resources to effectively diagnose and manage obstetric and neonatal emergencies [ 14 ]. Only vaginal deliveries are conducted in these facilities, attended by auxiliary or general nurse midwives (ANMs and GNMs).

Intervention

In each phase, a pair of nurses (mentors) were assigned four facilities to conduct on-site mentoring of labor room nurse mentees [ 21 ]. Mentor pairs visited each facility for one week, covering four assigned facilities over a four-week period. The mentor pairs returned for subsequent week-long visits once every month for seven to nine consecutive months. In other words, facilities received one week of mentoring in a month for 7–9 consecutive months. The mentors engaged in a variety of activities including skill demonstrations, didactic sessions, high-fidelity simulation and bedside mentoring during actual patient care.

An integral part of the nurse-mentoring program was PRONTO International’s ( http://prontointernational.org ) simulation and team training. The simulation and team training curriculum was tailored to address local contextual needs and incorporated in the AMANAT program since the outset. The three components of the PRONTO curriculum were: (1) realistic human-centered in-situ simulation scenarios of normal and complicated deliveries, including scenarios with simultaneously occurring emergencies, to promote use of EBPs, (2) efficient teamwork and communication (T&C) among providers and (3) increasing provider awareness around person-centered maternity care [ 21 , 22 ]. Simulations were conducted in providers’ usual work settings utilizing a maternal actor wearing PartoPants (a hybrid low-tech birth simulator) [ 22 ], and a NeoNatalie infant mannequin, nurses from the facilities acted as the patient to gain in-sight into the patient experience. A unique aspect of PRONTO’s simulation is use of a maternal actor instead of a mannequin. PRONTO trained all nurses to facilitate and video-record simulations, conduct video-aided debriefings after simulations and perform rapid debriefings after live deliveries.

The T&C component focused on building collaborative environment among mentees. It included structured team-building activities as well as integration of specific communication techniques, including ‘think out loud,’ ‘call back,’ ‘call out,’ ‘SBAR’ (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation), and debriefing (adapted from the TeamSTEPPS curriculum) [ 23 ]. These activities provided mentees with an opportunity to practice technical and non-technical competencies required to manage a variety of obstetric and neonatal complications as a team, even as a very small team.

The Institutional Review Board of the Indian Institute of Health Management Research in Jaipur, India (date–June 27, 2015) and the Committee for Human Research at the University of California San Francisco approved the study (date–May 20, 2015). Study ID# 14–15446.

Data collection systems