- Open access

- Published: 04 January 2021

Climate change and health in North America: literature review protocol

- Sherilee L. Harper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7298-8765 1 ,

- Ashlee Cunsolo 2 ,

- Amreen Babujee 1 ,

- Shaugn Coggins 1 ,

- Mauricio Domínguez Aguilar 3 &

- Carlee J. Wright 1

Systematic Reviews volume 10 , Article number: 3 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

11 Citations

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Climate change is a defining issue and grand challenge for the health sector in North America. Synthesizing evidence on climate change impacts, climate-health adaptation, and climate-health mitigation is crucial for health practitioners and decision-makers to effectively understand, prepare for, and respond to climate change impacts on human health. This protocol paper outlines our process to systematically conduct a literature review to investigate the climate-health evidence base in North America.

A search string will be used to search CINAHL®, Web of Science™, Scopus®, Embase® via Ovid, and MEDLINE® via Ovid aggregator databases. Articles will be screened using inclusion/exclusion criteria by two independent reviewers. First, the inclusion/exclusion criteria will be applied to article titles and abstracts, and then to the full articles. Included articles will be analyzed using quantitative and qualitative methods.

This protocol describes review methods that will be used to systematically and transparently create a database of articles published in academic journals that examine climate-health in North America.

Peer Review reports

The direct and indirect impacts of climate change on human health continue to be observed globally, and these wide-ranging impacts are projected to continue to increase and intensify this century [ 1 , 2 ]. The direct climate change effects on health include rising temperatures, which increase heat-related mortality and morbidity [ 3 , 4 , 5 ], and increased frequency and intensity of storms, resulting in increased injury, death, and psychological stressors [ 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 ]. Indirect climate change impacts on health occur via altered environmental conditions, such as climate change impacts on water quality and quantity, which increase waterborne disease [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]; shifting ecosystems, which increase the risk of foodborne disease [ 14 , 15 , 16 ], exacerbate food and nutritional security [ 17 , 18 ], and change the range and distribution of vectors that cause vectorborne disease [ 19 , 20 ]; and place-based connections and identities, leading to psycho-social stressors and potential increases in negative mental health outcomes and suicide [ 6 , 8 ]. These wide-ranging impacts are not uniformly or equitably distributed: children, the elderly, those with pre-existing health conditions, those experiencing lower socio-economic conditions, women, and those with close connections to and reliance upon the local environment (e.g. Indigenous Peoples, farmers, fishers) often experience higher burdens of climate-health impacts [ 1 , 2 , 21 ]. Indeed, climate change impacts on human health not only are dependent on exposure to climatic and environmental changes, but also depend on climate change sensitivity and adaptive capacity—both of which are underpinned by the social determinants of health [ 1 , 22 , 23 ].

The inherent complexity, great magnitude, and widespread, inequitable, and intersectional distribution of climate change impacts on health present an urgent and grand challenge for the health sector this century [ 2 , 24 , 25 ]. Climate-health research and evidence is critical for informing effective, equitable, and timely adaptation responses and strategies. For instance, research continues to inform local to international climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments [ 26 ]. However, to create evidence-based climate-health adaptation strategies, health practitioners, researchers, and policy makers must sift and sort through vast and often unmanageable amounts of information. Indeed, the global climate-health evidence base has seen exponential growth in recent years, with tens of thousands of articles published globally this century [ 22 , 25 , 27 , 28 ]. Even when resources are available to parse through the evidence base, the available research evidence may not be locally pertinent to decision-makers, may provide poor quality of evidence, may exclude factors important to decision-makers, may overlook temporal and geographical scales over which decision-makers have impact, and/or may not produce information in a timely manner [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ].

Literature reviews that utilize systematic methods present a tool to efficiently and effectively integrate climate-health information and provide data to support evidence-based decision-making. Furthermore, literature reviews that use systematic methods are replicable and transparent, reduce bias, and are ultimately intended to improve reliability and accuracy of conclusions. As such, systematic approaches to identify, explore, evaluate, and synthesize literature separates insignificant, less rigorous, or redundant literature from the critical and noteworthy studies that are worthy of exploration and consideration [ 38 ]. As such, a systematic approach to synthesizing the climate-health literature provides invaluable information and adds value to the climate-health evidence base from which decision-makers can draw from. Therefore, we aim to systematically and transparently create a database of articles published in academic journals that examine climate-health in North America. As such, we outline our protocol that will be used to systematically identify and characterize literature at the climate-health nexus in North America.

This protocol was designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines [ 39 , 40 ] and presented in accordance with the PRISMA-P checklist.

Research questions

Research on climate change and human health encompasses a diverse range of health outcomes, climate change exposures, populations, and study designs. Given the breadth and depth of information needed by health practitioners and decision-makers, a variety of research questions will be examined (Table 1 ).

Search strategy

The search strategy, including the search string development and selection of databases, was developed in consultation with a research librarian and members of the research team (SLH, AC, and MDA). The search string contains terms related to climate change [ 41 , 42 ], human health outcomes [ 1 , 25 , 43 , 44 ], and study location (Table 2 ). Given the interdisciplinary nature of the climate-health nexus and to ensure that our search is comprehensive, the search string will be used to search five academic databases:

CINAHL® will be searched to capture unique literature not found in other databases on common disease and injury conditions, as well as other health topics;

Web of Science™ will be searched to capture a wide range of multi-disciplinary literature;

Scopus® will be searched to capture literature related to medicine, technology, science, and social sciences;

Embase® via Ovid will be searched to capture a vast range of biomedical sciences journals; and

MEDLINE® via Ovid will be searched to capture literature on biomedical and health sciences.

No language restrictions will be placed on the search. Date restrictions will be applied to capture literature published on or after 01 January 2013, in order to capture literature published after the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (which assessed literature accepted for publication prior to 31 August 2013). An initial test search was conducted on June 10, 2019, and updated on February 14, 2020; however, the search will be updated to include literature published within the most recent full calendar year prior to publication.

To explore the sensitivity of our search and capture any missed articles, (1) a snowball search will be conducted on the reference lists of all the literature that meet the inclusion criteria and (2) a hand search of three relevant disciplinary journals will be conducted:

Environmental Health Perspectives , an open access peer-reviewed journal that is a leading disciplinary journal within environmental health sciences;

The Lancet , a peer-reviewed journal that is the leading disciplinary journal within public health sciences; and

Climatic Change , a peer-reviewed journal covering cross-disciplinary literature that is a leading disciplinary journal for climate change research.

Citations will be downloaded from the databases and uploaded into Mendeley™ reference management software to facilitate reference management, article retrieval, and removal of duplicate citations. Then, de-duplicated citations will be uploaded into DistillerSR® to facilitate screening.

Article selection

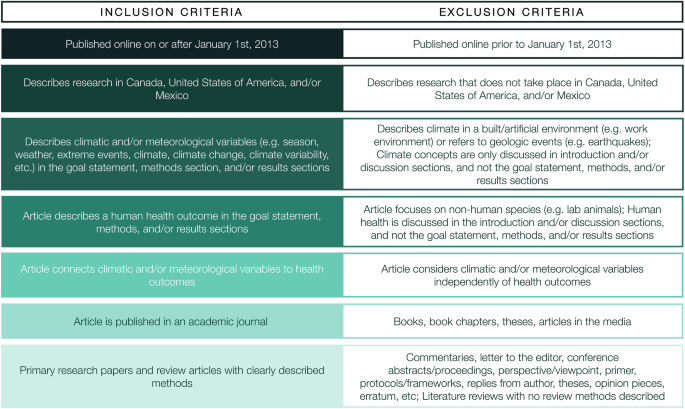

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

To be included, articles must evaluate or examine the intersection of climate change and human health in North America (Fig. 1 ). Health is defined to include physical, mental, emotional, and social health and wellness [ 1 , 25 , 43 , 44 ] (Fig. 1 ). This broad definition will be used to examine the nuanced and complex direct and indirect impacts of climate change on human health. To examine the depth and breadth of climate change impacts on health, climate change contexts are defined to include seasonality, weather parameters, extreme weather events, climate, climate change, climate variability, and climate hazards [ 41 , 42 ] (Fig. 1 ). However, articles that discuss climate in terms of indoor work environments, non-climate hazards due to geologic events (e.g. earthquakes), and non-anthropogenic climate change (e.g. due to volcanic eruptions) will be excluded. This broad definition of climate change contexts will be used in order to examine the wide range and complexity of climate change impacts on human health. To be included, articles need to explicitly link health outcomes to climate change in the goal statement, methods section, and/or results section of the article. Therefore, articles that discuss both human health and climate change—but do not link the two together—will be excluded. The climate-health research has to take place in North America to be included. North America is defined to include Canada, the USA, and Mexico in order to be consistent with the IPCC geographical classifications; that is, in the Fifth Assessment Report, the IPCC began confining North America to include Canada, Mexico, and the USA [ 45 ] (Fig. 1 ). Articles published in any language will be eligible for inclusion. Articles need to be published online on or after 01 January 2013 to be included. No restrictions will be placed on population type (i.e. all human studies will be eligible for inclusion).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria to review climate change and health literature in North America

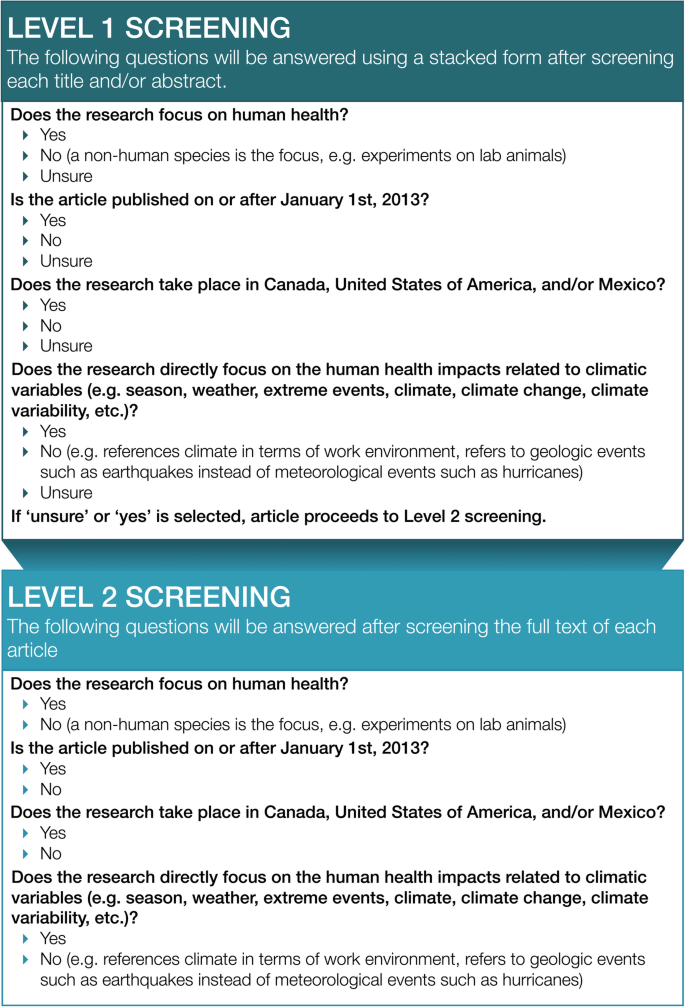

Level 1 screening

The title and abstract of each citation will be examined for relevance. A stacked questionnaire will be used to screen the titles and abstracts; that is, when a criterion is not met, the subsequent criteria will not be assessed. When all inclusion criteria are met and/or it is unclear whether or not an inclusion criterion is met (e.g. “unsure”), the article will proceed to Level 2 screening. If the article meets any exclusion criteria, it will not proceed to Level 2 screening. Level 1 screening will be completed by two independent reviewers, who will meet to resolve any conflicts via discussion. The level of agreement between reviewers will be evaluated by dividing the total number of conflicts by the total number of articles screened for Level 1.

Level 2 screening

The full text of all potentially relevant articles will be screened for relevance. A stacked questionnaire will also be used to screen the full texts. In Level 2 screening, only articles that meet all the inclusion criteria will be included in the review (i.e. “unsure” will not be an option). Level 2 screening will be completed by two independent reviewers, who will meet to resolve any conflicts via discussion. The level of agreement between reviewers will be evaluated by dividing the total number of conflicts by the total number of articles screened for Level 2 (Fig. 2 ).

Flow chart of screening questions for the literature review on climate change and health in North America

Data extraction and analysis

A data extraction form will be created in DistillerSR® ( Appendix 2 ) and will be tested by three data extractors on a sample of articles to allow for calibration on the extraction process (i.e. 5% of articles if greater than 50 articles, 10% of articles if less than or equal to 50 articles). After completing the calibration process, the form will be adapted based on feedback from the extractors to improve usability and accuracy. The data extractors will then use the data extraction form to complete data extraction. Reviewers will meet regularly to discuss and resolve any further issues in data extraction, in order to ensure the data extraction process remains consistent across reviewers.

Data will be extracted from original research papers (i.e. articles containing data collection and analysis) and review articles that reported a systematic methodology. This data extraction will focus on study characteristics, including the country that the data were collected in, focus of the study (i.e. climate change impact, adaptation, and/or mitigation), weather variables, climatic hazards, health outcomes, social characteristics, and future projections. The categories within each study characteristic will not be mutually exclusive, allowing more than one response/category to be selected under each study characteristic. For the country of study, Canada, the USA, and/or Mexico will be selected if the article describes data collection in each country respectively. Non-North American regions will be selected if the article not only collects data external to North America, but also includes data collection within Canada, the USA, and/or Mexico. For the study focus, data will be extracted on whether the article focuses on climate change impacts, adaptation, and/or mitigation within the goals, methods, and/or results sections of the article. Temperature, precipitation, and/or UV radiation will be selected for weather variables if the article utilizes these data in the goal, methods, and/or results sections. Data will be extracted on the following climatic hazards if the article addresses them in the goal, methods, and/or results sections: heat events (e.g. extreme heat, heat waves), cold events (e.g. extreme cold, winter storms), air quality (e.g. pollution, parts per million (PPM) data, greenhouse gas emissions), droughts, flooding, wildfires, hurricanes, wildlife changes (including changes in disease vectors such as ticks or mosquitos), vegetation changes (including changes in pollen), freshwater (including drinking water), ocean conditions (including sea level rise and ocean acidity/salinity/temperature changes), ice extent/stability/duration (including sea ice and freshwater ice), coastal erosion, permafrost changes, and/or environmental hazards (e.g. exposure to sewage, reduced crop productivity).

Data will be extracted on the following health outcomes if the article focuses on them within the goal, methods, and/or results sections: heat-related morbidity and/or mortality, respiratory outcomes (including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), cardiovascular outcomes (including heart attacks or stroke), urinary outcomes (e.g. urinary tract infections, renal failure), dermatologic concerns, mental health and wellness (e.g. suicide, emotional health), fetal health/birth outcomes and/or maternal health, cold exposure, allergies, nutrition (including nutrient deficiency), waterborne disease, foodborne disease, vectorborne disease, injuries (including accidents), and general morbidity and/or mortality. Data on the following social characteristics will also be extracted from the articles if they are included in the goal, methods, and/or results sections of the article: access to healthcare, sex and/or gender, age, income, livelihood (including data on employment, occupation), ethnicity, culture, Indigenous Peoples, rural/remote communities (“rural”, “remote”, or similar terminology must be explicitly mentioned), urban communities (“urban”, “city”, “metropolitan”, or similar terminology must be explicitly used), coastal communities (use of “coastal”, or similar terms must be explicitly mentioned), residence location (zipcode/postal code, neighbourhood, etc.), level of education, and housing (e.g. data on size, age, number of windows, air conditioning). Finally, data will be collected on future projections, including projections that employ qualitative and/or quantitative methods that are included in the goal, methods, and/or results sections of the article.

Descriptive statistics and regression modelling will be used to examine publication trends. Data will be visualized through the use of maps, graphs, and other visualization techniques as appropriate. To enable replicability and transparency, a PRISMA flowchart will be created to illustrate the article selection process and reasons for exclusion. Additionally, qualitative thematic analyses will be conducted. These analyses will utilize constant-comparative approaches to identify patterns across articles through the identification, development, and refinement of codes and themes. Article excerpts will be grouped under thematic categories in order to explore connections in article characteristics, methodologies, and findings.

Quality appraisal of studies included in the systematic scoping review will be performed using a framework based on the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [ 46 ] and the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) tool [ 47 ]. This will enable appraisal of evidence in reviews that contain qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies, as well as appraisal of methodological limitations in included qualitative studies. These tools may be adapted to include additional questions as required in order to fit the scope and objectives of the review. A minimum of two reviewers will independently appraise the included articles and discuss judgements as needed. The findings will be made available as supplementary material for the review.

Climate-health literature reviews using systematic methods will be increasingly critical in the health sector, given the depth and breadth of the growing body of climate change and health literature, as well as the urgent need for evidence to inform climate-health adaptation and mitigation strategies. To support and encourage the systematic and transparent identification and synthesis of climate-health information, this protocol describes our approach to systematically and transparently create a database of articles published in academic journals that examine climate-health in North America.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

Parts per million

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analyses, Protocol Extension

- United States of America

Ultraviolet

Smith KR, Woodward A, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chadee DD, Honda Y, Liu Q, et al. Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, et al., editors. Climate Change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability part A: global and sectoral aspects contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 709–54.

Google Scholar

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Bouley T, Boykoff M, et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):581–630.

Article Google Scholar

Son JY, Liu JC, Bell ML. Temperature-related mortality: a systematic review and investigation of effect modifiers. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14:073004.

Campbell S, Remenyi TA, White CJ, Johnston FH. Heatwave and health impact research: a global review. Heal Place. 2018;53:210–8.

Sanderson M, Arbuthnott K, Kovats S, Hajat S, Falloon P. The use of climate information to estimate future mortality from high ambient temperature: a systematic literature review. PLoS One. 2017: e0180369.

Rataj E, Kunzweiler K, Garthus-Niegel S. Extreme weather events in developing countries and related injuries and mental health disorders - a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1020.

Saulnier DD, Brolin Ribacke K, von Schreeb J. No Calm after the storm: a systematic review of human health following flood and storm disasters. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(5):568–79.

Cunsolo A, Neville E. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8:275–81.

Levy K, Woster AP, Goldstein RS, Carlton EJ. Untangling the impacts of climate change on waterborne diseases: a systematic review of relationships between diarrheal diseases and temperature, rainfall, flooding, and drought. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:4905–22.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Semenza JC, Herbst S, Rechenburg A, Suk JE, Höser C, Schreiber C, et al. Climate change impact assessment of food- and waterborne diseases. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2012;42(8):857–90.

Cann K, Thomas D, Salmon R, W-J AP, Kay D. Extreme water-related weather events and waterborne disease. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:671–86.

Andrade L, O’Dwyer J, O’Neill E, Hynds P. Surface water flooding, groundwater contamination, and enteric disease in developed countries: a scoping review of connections and consequences. Environ Pollut. 2018;236:540–9.

Harper SL, Wright C, Masina S, Coggins S. Climate change, water, and human health research in the Arctic. Water Secur. 2020;10:100062.

Park MS, Park KH, Bahk GJ. Interrelationships between multiple climatic factors and incidence of foodborne diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:2482.

Lake IR, Barker GC. Climate change, foodborne pathogens and illness in higher-income countries. Curr Environ Heal Rep. 2018;5(1):187–96.

Lake IR, Gillespie IA, Bentham G, Nichols GL, Lane C, Adak GK, et al. A re-evaluation of the impact of temperature and climate change on foodborne illness. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(11):1538–47.

Lake IR, Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Bentham G, Boxall AB. a. A, Draper A, et al. Climate change and food security: health impacts in developed countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1520–6.

Springmann M, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S, Garnett T, Godfray HCJ, Gollin D, et al. Global and regional health effects of future food production under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1937–46.

Campbell-Lendrum D, Manga L, Bagayoko M, Sommerfeld J. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: what are the implications for public health research and policy? Philos Trans R Soc London. 2015;370:20130552.

Sweileh WM. Bibliometric analysis of peer-reviewed literature on climate change and human health with an emphasis on infectious diseases. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):1–17.

Ford J. Indigenous health and climate change. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1260–6.

Butler CD. Climate change, health and existential risks to civilization: a comprehensive review (1989–2013). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2266.

Tong S, Ebi K. Preventing and mitigating health risks of climate change. Environ Res. 2019;174:9–13.

Ebi KL, Hess JJ. The past and future in understanding the health risks of and responses to climate variability and change. Int J Biometeorol. 2017;61(S1):71–80.

Hosking J, Campbell-Lendrum D. How well does climate change and human health research match the demands of policymakers? A scoping review. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(8):1076–82.

Berry P, Enright PM, Shumake-Guillemot J, Villalobos Prats E, Campbell-Lendrum D. Assessing health vulnerabilities and adaptation to climate change: a review of international progress. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(12):2626.

Verner G, Schütte S, Knop J, Sankoh O, Sauerborn R. Health in climate change research from 1990 to 2014: positive trend, but still underperforming. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:30723.

Ebi KL, Hasegawa T, Hayes K, Monaghan A, Paz S, Berry P. Health risks of warming of 1.5 °C, 2 °C, and higher, above pre-industrial temperatures. Environ Res Lett. 2018;13(6):063007.

Bäckstrand K. Civic science for sustainability: reframing the role of experts, policy-makers and citizens in environmental governance. Glob Environ Polit. 2003;3(4):24–41.

Susskind L, Jain R, Martyniuk A. Better environmental policy studies: how to design and conduct more effective analyses. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2001. p. 256.

Holmes J, Clark R. Enhancing the use of science in environmental policy-making and regulation. Environ Sci Policy. 2008;11(8):702–11.

Pearce T, Ford J, Duerden F, Smit B, Andrachuk M, Berrang-Ford L, et al. Advancing adaptation planning for climate change in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR): a review and critique. Reg Environ Chang. 2011;11(1):1–17.

Gearheard S, Shirley J. Challenges in community-research relationships: learning from natural science in Nunavut. Arctic. 2007;60(1):62–74.

Brownson R, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride T. Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(2):164–72.

Feldman P. Improving communication between researchers and policy makers in long-term care or, researchers are from Mars; policy makers are from Venus. Gerontologist. 2001;41(3):312–21.

Pearce TD, Ford JD, Laidler GJ, Smit B, Duerden F, Allarut M, et al. Community collaboration and climate change research in the Canadian Arctic. Polar Res. 2009;28(1):10–27.

Duerden F, Beasley E, Riewe R, Oakes J. Assessing community vulnerabilities to environmental change in the Inuvialuit region. Climate Change: Linking Traditional and Scientific Knowledge. Winnipeg, MB: Aboriginal Issues Press; 2006.

Mulrow CD. Rationale for systematic reviews. BMJ. 1994;309(6954):597–9.

Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D. The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

IPCC. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, et al., editors. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. 1535 pp.

IPCC. Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. A special report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Field CB, Barros V, Stocker TF, Qin D, Dokken DJ, Ebi KL, et al., editors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. p. 582.

Woodward A, Smith KR, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chadee DD, Honda Y, Liu Q, et al. Climate change and health: on the latest IPCC report. Lancet. 2014;383(9924):1185–9.

Confalonieri U, Menne B, Akhtar R, Ebi KL, Hauengue M, Kovats RS, et al. Human Health. In: Parry ML, Canziani OF, Palutikof JP, van der Linden PJ, Hanson CE, editors. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 391–431.

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part B: regional aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In: Barros VR, Field CB, Dokken DJ, Mastrandrea MD, Mach KJ, Bilir TE, et al., editors. Climate change 2014 impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: part A: global and sectoral aspects. Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 688.

Hong Q, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Registration of copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada; 2018. p. 1–11.

Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, et al. Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: an approach to assess confidence in findings from qualitative evidence syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):1001895.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Maria Tan at the University of Alberta Library for the advice, expertise and guidance provided in developing the search strategy for this protocol. Special thanks to those who assisted with methodology refinement, including Etienne de Jongh, Katharine Neale, and Tianna Rusnak.

Funding was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (to SLH and AC). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Public Health, University of Alberta, ECHA, 11405 87 Ave NW, Edmonton, AB, T6G 1C9, Canada

Sherilee L. Harper, Amreen Babujee, Shaugn Coggins & Carlee J. Wright

School of Arctic & Subarctic Studies, Labrador Institute of Memorial University, 219 Hamilton River Road, Stn B, PO Box 490, Happy Valley-Goose Bay, NL, A0P 1E0, Canada

Ashlee Cunsolo

Unidad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Calle 61 x 66 # 525. Col. Centro, Mérida, Yucatán, México

Mauricio Domínguez Aguilar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SLH, AC, and MDA contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, writing, and editing of the manuscript. AB contributed to the methodology, writing, and editing of the manuscript. SC contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. CJW contributed to visualization, writing, and editing of the manuscript. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sherilee L. Harper .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Search strategy for CINAHL®, Web of Science™, Scopus®, Embase® via Ovid, and MEDLINE® via Ovid.

Data extraction form

- *Categories were not mutually exclusive; that is, more than one category could be selected

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Harper, S.L., Cunsolo, A., Babujee, A. et al. Climate change and health in North America: literature review protocol. Syst Rev 10 , 3 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01543-y

Download citation

Received : 30 October 2020

Accepted : 23 November 2020

Published : 04 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01543-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Climate Change

- Human Health

- Mental Health

- North America

Systematic Reviews

ISSN: 2046-4053

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 February 2024

Globally representative evidence on the actual and perceived support for climate action

- Peter Andre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8213-527X 1 ,

- Teodora Boneva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4227-3686 2 ,

- Felix Chopra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7621-1045 3 &

- Armin Falk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7284-3002 2

Nature Climate Change volume 14 , pages 253–259 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

53k Accesses

3 Citations

1253 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Climate-change mitigation

- Psychology and behaviour

Mitigating climate change necessitates global cooperation, yet global data on individuals’ willingness to act remain scarce. In this study, we conducted a representative survey across 125 countries, interviewing nearly 130,000 individuals. Our findings reveal widespread support for climate action. Notably, 69% of the global population expresses a willingness to contribute 1% of their personal income, 86% endorse pro-climate social norms and 89% demand intensified political action. Countries facing heightened vulnerability to climate change show a particularly high willingness to contribute. Despite these encouraging statistics, we document that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, wherein individuals around the globe systematically underestimate the willingness of their fellow citizens to act. This perception gap, combined with individuals showing conditionally cooperative behaviour, poses challenges to further climate action. Therefore, raising awareness about the broad global support for climate action becomes critically important in promoting a unified response to climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

War and pandemic do not jeopardize Germans’ willingness to support climate measures

The differential impact of climate interventions along the political divide in 60 countries

How does public perception of climate protest influence support for climate action?

The world’s climate is a global common good and protecting it requires the cooperative effort of individuals across the globe. Consequently, the ‘human factor’ is critical and renders the behavioural science perspective on climate change indispensable for effective climate action. Despite its importance, limited knowledge exists regarding the willingness of the global population to cooperate and act against climate change 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 . To fill this gap, we designed and conducted a globally representative survey in 125 countries, with the aim of examining the potential for successful global climate action. The central question we seek to answer is to what extent are individuals around the globe willing to contribute to the common good, and how do people perceive other people’s willingness to contribute (WTC)?

Drawing on a multidisciplinary literature on the foundations of cooperation, our study focuses on four aspects that have been identified as critical in promoting cooperation in the context of common goods: the individual willingness to make costly contributions, the approval of pro-climate norms, the demand for political action and beliefs about the support of others. We start with exploring the individual willingness to make costly contributions to act against climate change, which is particularly relevant given that cooperation is costly and involves free-rider incentives 9 . Using a behaviourally validated measure, we assess the extent to which individuals around the globe are willing to contribute a share of their income, and which factors predict the observed cross-country variation.

Furthermore, the provision of common goods crucially depends on the existence and enforcement of social norms. These norms prescribe cooperative behaviour 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 and affect behaviour either through internalization (shame and guilt 16 ) or the enforcement of norms by fellow citizens (sanctions and approval 17 ). In our survey, we elicit support for pro-climate social norms and examine the extent to which such norms have emerged globally.

It is widely recognized that addressing common-good problems effectively necessitates institutions and concerted political action 18 , 19 , 20 . In democracies, the implementation of effective climate policies relies on popular support, and even in non-democratic societies, leaders remain attentive to prevailing political demands. Therefore, we also elicit the demand for political action as a critical input in the fight against climate change 21 .

Previous research in the behavioural sciences has shown that many individuals can be characterized as conditional cooperators 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 . This means that individuals are more likely to contribute to the common good when they believe others also contribute. We test this central psychological mechanism of cooperation using our data on actual and perceived WTC. Moreover, we investigate whether beliefs about others’ WTC are well calibrated or whether they are systematically biased. If beliefs are overly pessimistic, this would imply that the world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance 27 , where systematic misperceptions about others’ WTC hinder cooperation and reinforce further pessimism. In such an equilibrium, correcting beliefs holds tremendous potential for fostering cooperation 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 .

The global survey

To obtain globally representative evidence on the willingness to act against climate change, we designed the Global Climate Change Survey. The survey was administered as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in a large and diverse set of countries ( N = 125) using a common sampling and survey methodology ( Methods ). The countries included in this study account for 96% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, 96% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 92% of the global population. To ensure national representativeness, each country sample is randomly selected from the resident population aged 15 and above. Interviews were conducted via telephone (common in high-income countries) or face to face (common in low-income countries), with randomly drawn phone numbers or addresses. Most country samples include approximately 1,000 respondents, and the global sample comprises a total of 129,902 individuals.

To assess respondents’ willingness to incur a cost to act against climate change, we elicit their willingness to contribute a fraction of their income to climate action. More specifically, we ask respondents whether they would be ‘willing to contribute 1% of [their] household income every month to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no), and, if not, whether they would be willing to contribute a smaller amount (yes or no). To account for the substantial variation in income levels across countries, the question is framed in relative terms. Respondents’ answers thus reflect how strongly they value climate action relative to alternative uses of their income. The figure of 1% is deliberately chosen as it falls within the range of plausible previously reported estimates of climate change mitigation costs 32 , 33 .

Our WTC measure has been empirically validated and shown to predict incentivized pro-climate donation decisions ( Methods ). In a representative US sample 30 , respondents who state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their monthly income donate 43% more money to a climate charity ( P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test, N = 1,993; Supplementary Fig. 1 ) and are 21–39 percentage points more likely to avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 1 ).

To measure respondents’ beliefs about other people’s WTC, we first tell respondents that we are surveying many other individuals in their country about their willingness to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming. We then ask respondents to estimate how many out of 100 other individuals in their country would be willing to contribute this amount, that is, possible answers range from 0 to 100.

To assess individual approval of pro-climate social norms, we ask respondents to indicate whether they think that people in their country ‘should try to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). Following recent research on social norms 15 , 34 , the item elicits respondents’ views about what other people should do, that is, what kind of behaviour they consider normatively appropriate (so-called injunctive norms 10 ).

Finally, we measure demand for political action by asking respondents whether they think that their ‘national government should do more to fight global warming’ (answered yes or no). This item assesses the extent to which individuals regard their government’s current efforts as insufficient and sheds light on the potential for increased political action in the future.

The approval of pro-climate norms and the demand for political action are deliberately measured in a general manner to account for the fact that suitable concrete mitigation strategies may differ across countries. Our general measures strongly correlate with the approval of specific pro-climate norms and the demand for concrete policy measures ( Methods ). In a representative US sample, individuals who approve of the general norm to act against climate change are substantially more likely to state that individuals ‘should try to’ avoid fossil-fuel-based means of transport (car and plane), restrict their meat consumption, use renewable energy or adapt their shopping behaviour (correlation coefficients ρ between 0.35 and 0.51, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,994; Supplementary Table 2 ). Similarly, the general demand for more political action is strongly correlated with demand for specific climate policies, such as a carbon tax on fossil fuels, regulatory limits on the CO 2 emissions of coal-fired plants, or funding for research on renewable energy ( ρ between 0.49 and 0.59, all P < 0.001 for two-sided t -tests, N = 1,996; Supplementary Table 3 ).

To ensure comparability across countries and cultures, professional translators translated the survey into the local languages following best practices in survey translation by using an elaborate multi-step translation procedure. The survey was extensively pre-tested in multiple countries of diverse cultural heritage to ensure that respondents with different cultural, economic and educational backgrounds could comprehend the questions in a comparable way. We deliberately refer to ‘global warming’ rather than ‘climate change’ throughout the survey to prevent confusion with seasonal changes in weather 35 , 36 , and provide all respondents with a brief definition of global warming to ensure a common understanding of the term.

A list of variables, definitions and sources is available in Methods . In all analyses, we use Gallup’s sampling weights, which were calculated by Gallup in multiple stages. A probability weight factor (base weight) was constructed to correct for unequal selection probabilities resulting from the stratified random sampling procedure. At the next step, the base weights were post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match the weighted sample totals to known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. When describing the data at the supranational level, we also weight each country sample by its share of the world population.

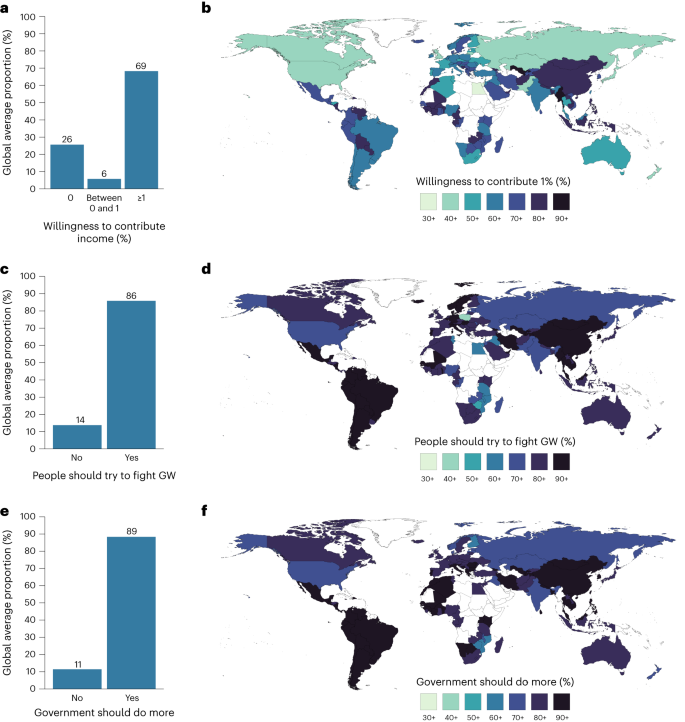

Widespread global support for climate action

The globally representative data reveal strong support for climate action around the world. First, a large majority of individuals—69%—state they would be willing to contribute 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming (Fig. 1a ). An additional 6% report they would be willing to contribute a smaller fraction of their income, and 26% state they would not be willing to contribute any amount. The proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of their income varies considerably across countries (Fig. 1b ), ranging from 30% to 93%. In the vast majority of countries (114 of 125) the proportion is greater than 50%, and in a large number of countries (81 of 125) the proportion is greater than two-thirds.

a , c , e , The global average proportions of respondents willing to contribute income ( a ), approving of pro-climate social norms ( c ) and demanding political action ( e ). Population-adjusted weights are used to ensure representativeness at the global level. b , d , f , World maps in which each country is coloured according to its proportion of respondents willing to contribute 1% of income ( b ), approving of pro-climate social norms ( d ) and demanding political action ( f ). Sampling weights are used to account for the stratified sampling procedure. Supplementary Table 4 presents the data. GW, global warming.

Second, we document widespread approval of pro-climate social norms in almost all countries. Overall, 86% of respondents state that people in their country should try to fight global warming (Fig. 1c ). In 119 of 125 countries, the proportion of supporters exceeds two-thirds (Fig. 1d ).

Third, we identify an almost universal global demand for intensified political action. Across the globe, 89% of respondents state that their national government should do more to fight global warming (Fig. 1e ). In more than half the countries in our sample, the demand for more government action exceeds 90% (Fig. 1f ).

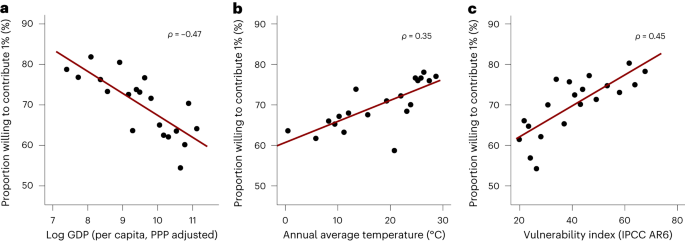

Stronger willingness to contribute in vulnerable countries

Although the approval of pro-climate social norms and the demand for intensified political action is substantial in almost all countries (Fig. 1d,f ), there is considerable variation in the proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% across countries (Fig. 1b ) and world regions (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5) . What explains the cross-country variation in individual WTC? Two patterns stand out.

First, there is a negative relationship between country-level WTC and (log) GDP per capita ( ρ = −0.47; 95% confidence interval (CI), [−0.60, −0.32]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Fig. 2a ). To illustrate, in the wealthiest quintile of countries, the average proportion of people willing to contribute 1% is 62%, whereas it is 78% in the least wealthy quintile of countries. A country’s GDP per capita reflects its resilience, that is, its economic capacity to cope with climate change. Put differently, in countries that are most resilient, individuals are least willing to contribute 1% of their income to climate action. At the same time, a country’s GDP is strongly related to its current dependence on GHG emissions 37 . For the countries studied here, the correlation coefficient between log GDP and log GHG emissions is 0.87. From a behavioural science perspective, this pattern is consistent with the interpretation that individuals are less willing to contribute if they perceive the adaptation costs as too high, that is, when the required lifestyle changes are perceived as too drastic.

a – c , Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportion of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and log average GDP (per capita, purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted) for 2010–2019 ( a ), annual average temperature (°C) for 2010–2019 ( b ) and the vulnerability index used in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) ( c ) 41 , 42 . The vulnerability index ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating higher vulnerability. Correlation coefficients are calculated from the unbinned country-level data. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line represents linear regression.

Second, we find a positive relationship between country-level WTC and country-level annual average temperature ( ρ = 0.35; 95% CI, [0.18, 0.49]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test, N = 125; Fig. 2b ). The average proportion of people who are willing to contribute increases from 64% among the coldest quintile of countries to 77% among the warmest quintile of countries. Average annual temperature captures how exposed a country is to global warming risks 38 , 39 . Countries with higher annual temperatures have already experienced greater damage due to global warming, potentially making future threats from climate change more salient to their residents 40 .

Both results replicate in a joint multivariate regression and are robust to the inclusion of continent fixed effects and other economic, political, cultural or geographic factors (Supplementary Tables 6 – 9 ). Focusing on North America, we also find a significantly positive association between WTC and average temperature on the subnational level (Supplementary Fig. 2 ). Moreover, as low GDP and high temperatures constitute two important aspects of vulnerability to climate change, we also draw on a more comprehensive summary measure of vulnerability, derived for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report 41 , 42 . In addition to national income and poverty levels, the index also takes into account non-economic factors, such as the quality of public infrastructure, health services and governance. It captures a country’s general lack of resilience and adaptive capacity, and it is highly correlated with log GDP ( ρ = −0.93) and temperature ( ρ = 0.62). Figure 2c confirms that people living in more vulnerable countries report a stronger WTC.

The country-level variation in pro-climate norms and demand for intensified political action is much smaller than that for the WTC. Nevertheless, we find that higher temperature predicts stronger norms and support for more political action. We do not detect a significant relationship with GDP (Supplementary Table 10 ).

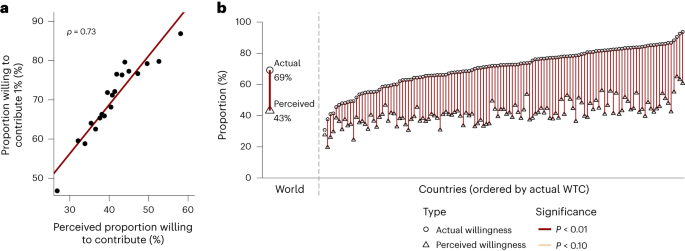

Beliefs and systematic misperceptions

In line with previous research 11 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , our data support the importance of conditional cooperation at the global level. Figure 3a shows a strong and positive correlation between the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% and the corresponding average perceived proportions of fellow citizens willing to contribute 1% ( ρ = 0.73; 95% CI, [0.64, 0.81]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125).

a , Binned scatter plots of the country-level proportions of individuals willing to contribute 1% of their income and the average perceived proportions of others who are willing to contribute 1% of their income. We use sampling weights to derive the country-level WTC and perceived WTC. Number of bins, 20; 6–7 countries per bin; derived from x axis. The red line shows the linear regression. b , Gap between the global and country proportions of respondents who are willing to contribute 1% of their income (circles) and the global and country average perceived proportions of others willing to contribute (triangles). The reported significance levels result from two-sided t -tests testing whether the proportion of individuals who are willing to contribute is equal to the average perceived proportion. We use population-adjusted weights to derive the global averages and the standard sampling weights otherwise. We derive the averages based on all available data, that is, we exclude missing responses separately for each question. See Supplementary Figure 4 for additional descriptive statistics for the perceived WTC (median, 25–75% quartile range).

We document the same pattern at the individual level. In a univariate linear regression analysis, a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others’ WTC is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability of contributing (95% CI, [0.41, 0.50]; P < 0.001; N = 111,134; Supplementary Table 11 ). This effect size aligns closely with the degree of conditional cooperation that has been documented in the laboratory 26 .

The critical role of beliefs raises the question of whether beliefs are well calibrated. In fact, Fig. 3b reveals sizeable and systematic global misperceptions. At the global level, there is a 26-percentage-point gap (95% CI, [25.6, 26.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 4 ) between the actual proportion of respondents who report being willing to contribute 1% of their income towards climate action (69%) and the average perceived proportion (43%). Put differently, individuals around the globe strongly underestimate their fellow citizens’ actual WTC to the common good. At the country level, the vast majority of respondents underestimate the actual proportion in their country (81%), and a large proportion of respondents underestimate the proportion by more than 10 percentage points (73%). This pattern holds for each country in our sample (Fig. 3b ). In all 125 countries, the average perceived proportion is lower than the actual proportion, significantly so in all but one country (two-sided t -tests, actual versus perceived WTC). If we limit the analysis to those respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and the perceived WTC, the global perception gap is estimated to be 29 percentage points (95% CI, [27.2, 30.0]; P < 0.001 for a two-sided t -test; N = 125; Supplementary Table 12 ), and the average perceived proportion is estimated to be significantly lower than the actual proportion in all 125 countries (Supplementary Fig. 3 ).

Although the perception gap is positive in all countries, we note that the size of the perception gap varies across countries (s.d. = 8.7 percentage points). Examining the same country-level characteristics as before, we find that the gap is significantly larger in countries with higher annual temperatures and significantly smaller in countries with high GDP (Supplementary Table 13 ). These results are largely robust to the inclusion of other economic, political or cultural factors, which we do not find to be significantly related to the perception gap. These findings are robust to only using respondents for whom we have non-missing data for both the actual and perceived WTC.

Climate scientists have stressed that immediate, concerted and determined action against climate change is necessary 32 , 41 , 43 , 44 . Against this backdrop, our study sheds light on people’s willingness to contribute to climate action around the world. What sets our study apart from existing cross-cultural studies on climate change perceptions 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 and policy views 4 , 5 , 6 is its globally representative coverage and its behavioural science perspective.

The results are encouraging. About two-thirds of the global population report being willing to incur a personal cost to fight climate change, and the overwhelming majority demands political action and supports pro-climate norms. This indicates that the world is united in its normative judgement about climate change and the need to act.

The four aspects of cooperation discussed in this article are likely to interact with one another. For example, consensus on pro-climate norms is likely to strengthen individuals’ WTC and vice versa 13 . Similarly, the enactment of climate policies is likely to strengthen climate norms and vice versa 45 . We find a strong positive correlation between the WTC, pro-climate norms, policy support and beliefs about others’ WTC across countries (Supplementary Table 14 ). Moreover, countries with a stronger approval of pro-climate social norms have passed significantly more climate-change-related laws and policies ( ρ = 0.20; 95% CI, [0.02, 0.36]; P = 0.028 for a two-sided t -test; N = 122). These positive interactions suggest that a change in one factor can unlock potent, self-reinforcing feedback cycles, triggering social-tipping dynamics 46 , 47 . Our findings can inform system dynamics models and social climate models that explicitly take into account the interaction of human behaviour with natural, physical systems 48 , 49 .

The widespread willingness to act against climate change stands in contrast to the prevailing global pessimism regarding others’ willingness to act. The world is in a state of pluralistic ignorance, which occurs when people systematically misperceive the beliefs or attitudes held by others 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 50 . The reasons underlying this perception gap are probably multifaceted, encompassing factors such as media and public debates disproportionately emphasizing climate-sceptical minority opinions 51 , and the influence of interest groups’ campaigning efforts 52 , 53 . Moreover, during periods of transition, individuals may erroneously attribute the inadequate progress in addressing climate change to a persistent lack of individual support for climate-friendly actions 54 .

Importantly, these systematic perception gaps can form an obstacle to climate action. The prevailing pessimism regarding others’ support for climate action can deter individuals from engaging in climate action, thereby confirming the negative beliefs held by others. Therefore, our results suggest a potentially powerful intervention, that is, a concerted political and communicative effort to correct these misperceptions. In light of a global perception gap of 26 percentage points (Fig. 3b ) and the observation that a 1-percentage-point increase in the perceived proportion of others willing to contribute 1% is associated with a 0.46-percentage-point increase in one’s own probability to contribute (Supplementary Table 11 ), such an intervention may yield quantitatively large, positive effects. Rather than echoing the concerns of a vocal minority that opposes any form of climate action, we need to effectively communicate that the vast majority of people around the world are willing to act against climate change and expect their national government to act.

Sampling approach

The survey was carried out as part of the Gallup World Poll 2021/2022 in 125 countries, with a median total response duration of 30 min. The four questions were included towards the end of the Gallup World Poll survey and were timed to take about 1.5 min.

Each country sample is designed to be representative of the resident population aged 15 and above. The geographic coverage area from which the samples are drawn generally includes the entire country. Exceptions relate to areas where the safety of the surveyors could not be guaranteed or—in some countries—islands with a very small population.

Interviews are conducted in one of two modes: computer-assisted telephone interviews via landline or mobile phone or face to face (mostly computer assisted). Telephone interviews were used in countries with high telephone coverage, countries in which it is the customary survey methodology and countries in which the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic ruled out a face-to-face approach. There is one exception: paper-and-pencil interviews had to be used in Afghanistan for 73% of respondents to minimize security concerns.

The selection of respondents is probability based. The concrete procedure depends on the survey mode. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll ( https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx ) 55 .

Telephone interviews involved random-digit dialling or sampling from nationally representative lists of phone numbers. If contacted via landline, one household member aged 15 or older is randomly selected. In countries with a landline or mobile telephone coverage of less than 80%, this procedure is also adopted for mobile telephone calls to improve coverage.

For face-to-face interviews, primary sampling units are identified (cluster of households, stratified by population size or geography). Within those units, a random-route strategy is used to select households. Within the chosen households, respondents are randomly selected.

Each potential respondent is contacted at least three (for face-to-face interviews) or five (telephone) times. If the initially sampled respondent can not be interviewed, a substitution method is used. The median country-level response rate corresponds to 65% for face-to-face interviews and 9% for telephone interviews. These response rates are comparatively high considering that survey participants are not offered financial incentives for participating in the Gallup World Poll. For telephone interviews, the Pew Research Center reports a response rate of 6% in the United States in 2019 ( https://pewrsr.ch/2XqxgTT ). For face-to-face interviews, ref. 56 found a non-response rate of 23.7% even in a country with very high levels of trust, such as Denmark.

The median and most common sample size is 1,000 respondents. An overview of survey modes and sample sizes can be found in Supplementary Table 15 .

Sampling weights

Although the sampling approach is probability based, some groups of respondents are more likely to be sampled by the sampling procedure. For instance, residents in larger households are less likely to be selected than residents in smaller households because both small and large households have an equal chance of being chosen. For this reason, Gallup constructs a probability weight factor (base weight) to correct for unequal selection probabilities. In a second step, the base weights are post-stratified to adjust for non-response and to match known population statistics. The standard demographic variables used for post-stratification are age, gender, education and region. In some countries, additional demographic information is used based on availability (for example, ethnicity or race in the United States). The weights range from 0.12 to 6.23, with a 10–90% quantile range of 0.28 to 2.10, ensuring that no observation is given an excessively disproportionate weight. Of all weights, 93% are between 0.25 and 4. More details are available in the documentation of the Gallup World Poll ( https://news.gallup.com/poll/165404/world-poll-methodology.aspx ) 55 .

We use these weights in our main analyses in two ways: first, when deriving national averages, we weight individual responses with Gallup’s sampling weights; and, second, when conducting individual-level regression analyses, we weight respondents with Gallup’s sampling weights.

We note that this weighting approach does not take into account the fact that some countries have a larger population than others. At the global level, the approach would effectively weight countries by their sample size and not their population size. Therefore, we also derive population-adjusted weights that render the data representative of the global population (aged ≥15) that is covered by our survey. The population-adjusted weight of individual i in country c is derived as

where w i c denotes the original Gallup sampling weight, I c the set of all respondents in country c , s c the country’s share of the global population aged ≥15 and n the total sample size of 129,902 respondents. Division by \({\sum }_{{I}_{c}}{w}_{ic}\) ensures that countries with a larger sample size (Supplementary Table 15 ) do not receive a larger weight. Multiplication with s c ensures that the total weight of a country sample is proportional to its population share. Multiplication with the constant n ensures that the total sum of the population-adjusted weights equals n , but is inconsequential for the results.

Although the two approaches yield very similar results (Supplementary Table 16 ), we use these population-adjusted weights wherever we present global statistics or statistics for supranational world regions. Supplementary Table 16 also shows that we obtain almost identical results if we do not use weights at all.

Global pre-test

A preliminary version of the survey was extensively pre-tested in 2020 in six countries of diverse cultural heritage—Colombia, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Kenya and Ukraine—to ensure that subjects from different cultural and economic backgrounds interpret the questions adequately. In each country, cognitive interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in local languages. The objectives of the pre-test were threefold, that is, to collect feedback, test whether the survey questions were understandable and check whether they were interpreted homogeneously across cultures. Each survey question was followed by additional probing questions that investigated respondents’ understanding of central terms and the overall logic of the question. Moreover, respondents were invited to express any comprehension difficulties. In response to the feedback, several minor adjustments to the survey were made. Most importantly, we switched to the term global warming instead of climate change to prevent confusion with seasonal changes in weather.

Survey items

The US English version of the questionnaire can be found below. Square brackets indicate information that is adjusted to each country. Parentheses indicate that a response option was available to the interviewer but not read aloud to the interviewee. The frequencies of missing data are summarized in Supplementary Table 17 .

Introduction to global warming

Now, on a different topic… The following questions are about global warming. Global warming means that the world’s average temperature has considerably increased over the past 150 years and may increase more in the future.

Willingness to contribute

Question 1 : Would you be willing to contribute 1% of your household income every month to fight global warming? This would mean that you would contribute [$1] for every [$100] of this income.

Responses : Yes, No, (DK), (Refused)

Coding : Binary dummy for Yes. (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Question 2 (asked only if ‘No’ was selected in Question 1) : Would you be willing to contribute a smaller amount than 1% of your household income every month to fight global warming?

Responses : Yes, No, I would not contribute any income, (DK), (Refused)

Coding : We classify respondents into three categories based on their responses to both questions. Willing to contribute (at least) 1%, willing to contribute between 0% and 1%, not willing to contribute. We conservatively code (DK) and (Refused) in Question 2 as ‘Not willing to contribute’.

Beliefs about others’ willingness to contribute

Question : We are asking these questions to 100 other respondents in [the United States]. How many do you think are willing to contribute at least 1% of their household income every month to fight global warming?

Responses : 0–100, (DK), (Refused)

Coding : 0–100, (DK) and (Refused) are coded as missing data.

Social norms

Question : Do you think that people in [the United States] should try to fight global warming?

Demand for political action

Question : Do you think the national government should do more to fight global warming?

Note : We were not allowed to field this question in Myanmar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Implementation errors

In two countries, an implementation error was made for the question on WTC a proportion of income.

In Kyrgyzstan, 4 of 1,001 respondents answered the survey in the language Uzbek. To these four respondents, the second sentence of question 1 was not read. The other respondents in Kyrgyzstan were interviewed in a different language and were not affected.

In Mongolia, respondents were asked whether they are willing to contribute less than 1% in question 1. Of these respondents, 93.1% answered yes. We approximate the proportion of Mongolian respondents who are willing to contribute 1% as follows. The implementation error should not affect the proportion of respondents who answer no to both questions (4.4%). Moreover, we know that in most countries 5–6% of respondents are not willing to contribute 1% but are willing to contribute a positive amount smaller than 1%. This is also true in neighbouring countries of Mongolia (China, 6.0%; Kazakhstan, 4.9%; Russia, 5.6%). Therefore, we derive the proportion of Mongolian respondents who are willing to contribute 1% as 100% − 4.4% − 6% = 89.6%, which is close to the uncorrected proportion of 93.1%. Results are virtually unchanged if we exclude observations from Mongolia.

Translation

The translation process of the US English original version into other languages followed the TRAPD model, first developed for the European Social Survey 57 . The acronym TRAPD stands for translation, review, adjudication, pre-testing and documentation. It is a team-based approach to translation and has been found to provide more reliable results than alternative procedures, such as back-translation. The following procedure is implemented:

Translation: a local professional translator conducts the first translation.

Review: the translation is reviewed by another professional translator from an independent company. The reviewer identifies any issues, suggests alternative wordings and explains their comments in English.

Adjudication: the original translator receives this feedback and can accept or reject the suggestions. In the latter case, he provides an English explanation for his decision and a third expert adjudicates the disputed translation, which often involves further exchange with the translators.

Pre-testing: a pilot test with at least ten respondents per language is conducted.

Documentation: translations and commentary (Gallup internal) are documented.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Gallup World Poll. Informed consent was obtained from all human research participants.

Our main measures of support for climate action are deliberately measured in a general manner to account for the fact that suitable concrete strategies to act against climate change can differ widely across the globe. However, in previous work, we collected both the general measures and additional specific measures for the different facets of climate cooperation. We conducted a survey with a diverse sample of respondents that is representative of the US population in terms of the sociodemographic characteristics of age, gender, education and region 30 . Specifically, we first elicit respondents’ WTC, demand for political action and approval of pro-climate change norms. In a second step, respondents can allocate money between themselves and a pro-climate charity (incentivized). We also elicit whether respondents have engaged in a set of specific climate-friendly behaviours in the previous 12 months (answered yes or no). We further elicit whether they think that people in the United States should engage in these specific climate-friendly behaviours (yes or no). Finally, we measure support for specific climate-change-related policies and regulations using a four-point Likert scale. Supplementary Tables 1 – 3 show that our general measures are strongly correlated with concrete climate-friendly behaviours, concrete climate-friendly norms and support for specific climate-change-related policies and regulation. More details on these data can be found in ref. 30 .

The data in ref. 30 also allow us to investigate whether we obtain similar results using two different survey methodologies. The Gallup World Poll relies on computer-assisted telephone interviews (landline and mobile) and random sampling via random-digit dialling. In ref. 30 , an online survey was conducted and quota-based sampling was used. Reassuringly, we obtain very similar results for the proportion of the population willing to contribute 1% of their household income, supporting pro-climate norms and demanding more political action (Table 1 ).

Additional data sources

Annual temperature.

This is the annual average temperature (in degrees Celsius) from 2010 to 2019. The data are available from the World Bank Group’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal ( https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/download-data ) and derived from the CRU TS v.4.05 data ( https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/ ).

A set of indicators for whether a country belongs to one of the following five continents: (1) Africa, (2) Americas, (3) Asia, (4) Europe and (5) Oceania.

Economic growth

The average GDP growth rate between 2000 and 2019, obtained by averaging the year-on-year change in real GDP per capita (in constant US dollars) across years (World Bank WDI database, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD ).

The average national GDP per capita from 2010 to 2019 in constant US dollars, adjusted for differences in purchasing power. To derive the percentage of world GDP that our survey represents, we take national GDP data from 2019. The data for each country are available from the World Bank WDI database ( https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD ). For Taiwan and Venezuela, the World Bank does not provide GDP estimates. Instead, we use data from the International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook Database ( https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2022/October ).

GHG emissions

The per-capita GHG emissions expressed in equivalent metric tons of CO 2 averaged from 2010 to 2019. To derive the percentage of world GHG emissions that our survey represents, we take national GHG data from 2019. GHGs include CO 2 (fossil only), CH 4 , N 2 O and F gases. Data are obtained from EDGAR v.7.0 (ref. 58 ).

Individualism–collectivism

This refers to a country’s location on the individualism–collectivism spectrum, which we standardize 59 .

Kinship tightness

This refers to the extent to which people are embedded in large, interconnected extended family networks. The measure is derived from the data of the Ethnographic Atlas in ref. 60 and is available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/JX1OIU .

Regional temperature

The population-weighted regional mean temperature in degrees Celsius (between 2010 and 2019). Regions are defined by Gallup and often coincide with the first administrative unit below the national level. We use temperature data from the Climatic Research Unit ( https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/ ) and population data from the LandScan database ( https://www.ornl.gov/project/landscan ) to construct this variable.

Scientific articles

The average number of scientific articles (per capita) from 2009 to 2018. The annual data for each country are available from the World Bank WDI database and normalized with annual population data from the Maddison Project Database 2020 ( https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020 ).

Secondary and tertiary education

This refers to the proportion of the population with secondary or tertiary education as the highest level of education. The Gallup World Poll includes respondent-level information on whether the highest level of educational attainment is secondary and tertiary education, which we aggregate to national proportion by using Gallup’s sampling weights.

Survival versus self-expression values

The extent to which people in a country hold survival versus self-expression values, which we standardize. We obtain the data from the axes of the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map ( https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=467 ) 61 .

Traditional versus secular values

The extent to which people in a country hold traditional versus secular values, which we standardize. We obtain the data from the axes of the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map ( https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSNewsShow.jsp?ID=467 ) 61 .

Vulnerability index

This measure captures a country’s vulnerability as defined in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report 41 , 42 . Specifically, the measure is the average of the vulnerability subcomponent of the INFORM Risk Index and the WorldRiskIndex. The INFORM Risk Index consists of 32 indicators related to vulnerability and coping capacity. The vulnerability component of the WorldRiskIndex encompasses 23 indicators, which cover susceptibility, absence of coping ability and lack of adaptive capability. For example, the subcomponents include indicators of extreme poverty, food security, access to basic infrastructure, access to health care, health status and governance. The data and documentation are available at https://ipcc-browser.ipcc-data.org/browser/dataset?id=3736 .

Quality of governance standard data set 2021

The following variables are compiled from the Quality of Governance Standard Data Set 2021 ( https://www.gu.se/en/quality-government ) 62 .

Concentration of political power