- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Choose a Narrator

I. What is a Narrator?

A narrator is the person telling the story, and it determines the point of view that the audience will experience. Every work of fiction has one! The narrator can take many forms—it may be a character inside the story (like the protagonist) telling it from his own point of view. It may be a completely neutral observer or witness sharing what he sees and experiences. It may be someone who is outside the story but has access to a character’s or characters ’ thoughts and feelings. Or, it may be an all-knowing presence who knows everything about the whole story, its setting, its characters, and even all of its history.

Though technically any type of written work has a narrator (since all information must be told from some point of view), its most important role is in fiction, where the style of narration determines everything about how the story is told, experienced, and understood by readers. This article will focus on that role.

II. Example of a Narrator

Here’s an example of a narrator who is telling the story from his point of view:

I’m going to share a story with you. It’s not an easy one to witness, for it’s about one of the worst things that ever happened to me. Others may tell it differently, but only in my version will you hear the entire truth, because only I know the real devastation of the events that unfolded on the day that changed my life forever.

My name is George, and I’m a professional speed eater. This is about the time I lost the most important hotdog eating contest of my life.

III. Types of Narrators

Authors use several types of narrators, or narrative styles (see Related Terms ). Third person and first person are the most common types of narration that authors employ in their writing, but the lesser known second-person narrator also exists!

a. First Person

A first person narrator is a character inside the story. He/she tells the reader what is happening from his/her own point of view, using “I,” “me” and “myself” to tell the story. Often, that means the reader learns the story alongside the narrator as it unfolds, hearing the narrator’s thoughts and feelings and understanding experiences in the way the narrator himself experiences them. One of the most interesting things about a first person narrator is that he or she can actually be someone unreliable—since the audience is experiencing the story as the narrator personally understands it, the point of view is very subjective and opinionated in ways that may not reveal the whole truth or the “full story.”

In addition to fiction, autobiographies use first-person narrative structure because the book is about the author himself.

b. Second person

A second person narrator is fairly unusual. In a second person narrative, the person telling the story uses “you” to describe the main character or narrator. In some cases, that also implies that perhaps the narrator or main character could even be you, the reader. Second person narration is used for “choose your own adventure” books, where you, the reader, have to decide what happens next in the story (i.e. “jump to page 50 if you turn left on the road, or jump to page 70 if you turn right” ).

c. Third Person

A third person narrator is not a part of the story, and refers to all of the characters (including the protagonist) using “he” and “she.” Using a third-person narrator gives an author the most options and flexibility in terms of how the story is told. The author may choose to share the thoughts, feelings, and points of view of several characters, instead of just one. As such, the third person is probably the most popular and widely-used style of narration, and there are three main types:

d. Third Person Objective

A third person objective narrator is just a witness to a story. They don’t have knowledge of any of the character’s thoughts or feelings, but are simply reporting on what is happening. It lets the audience form their own opinions based on objective observation.

e. Third Person Subjective

A third person subjective narrator is usually telling the story in a way that reflects at least one, but sometimes multiple characters’ thoughts, feelings and experiences. These things usually influence how the audience feels about the characters and what is going on in the story. It is probably the most popular narrative style.

f. Third Person Omniscient

A third person omniscient character is all-seeing and all-knowing. They are aware of all of the events that have ever happened and all of the people that they ever happened to. This means that they have full knowledge of all events, places, times, and people—this also includes the thoughts and memories of any character. In simple terms, a third person omniscient narrator is “God-like.”

IV. Importance of Narrators

The importance of having a narrator is obvious—without one, we simply couldn’t tell stories! But, more specifically, when it comes to storytelling, point of view is everything, and the narrator provides it to us. As such, narrative style is one of the most crucial elements of writing. An author chooses his narrator based on how he wants the story told, and how the audience is meant to experience it. Thus, everything we understand about a piece of writing is based on the style of narration, so its significance is huge.

V. Examples of Narrators in Pop Culture

Example 1: first person.

Sometimes films and TV shows tell their stories through the point of view of a main character. This usually means that the protagonist is speaking to the audience as they themselves go through the events that are happening on screen. An excellent example of this style is the current series Mr. Robot, where most of the story is told from the point of view of Elliot, a young computer programmer and hacker. Throughout the series, we hear his thoughts and experience things from his point of view. Here’s a clip:

Mr. Robot is particularly unique because Elliot suffers from mental illness and experiences delusions and hallucinations. Since the story is from his perspective, the audience sometimes doesn’t know what is real, and what is only being imagined by Elliot.

Example 2: Third Person

Most movies and television shows are told from a third-person point of view. Most of that time that means having no obvious narrator at all, where the audience is the only outside witness. But sometimes, there’s a third-person narrator who is also watching the story and reports on it, like in this clip from Moonrise Kingdom :

Here, the man reporting appears on screen, but he isn’t actually part of the story. He is just there to fill the audience in on some important information, and provide commentary and extra details as the story unfolds.

Example 3: Mixed Narration

Many television shows will use multiple narrators to tell their stories. This is especially popular in documentaries, reality TV, and mockumentary shows. A popular style is to have an objective, third-person narrator (the person behind the camera), but uses first-person narration by showing the characters’ points of view through onscreen interviews. In this way, it reveals things about the characters and lets you get to know them from two perspectives. Here’s a clip from Parks and Recreation:

Here, we first see Ron Swanson and his toothache from a third person point of view. Then, there’s an interview with him, which reveals the joke he performed and shares his own perspective of what just happened. Many other shows like Modern Family and the The Office work in this style, as does nearly every reality TV show that’s ever been made!

VI. Examples of Narrators in Literature

There have been many great novels and short stories with a first-person narrator. Scott F. Fditzergerald’s classic American novel The Great Gatsby is told from the perspective of Nick Carraway, a man who moves nearby Jay Gatsby. In the novel, we see everything from his point of view and understand it as he understands it. It opens like this:

In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “ Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “ just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.” He didn’t say any more, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. In consequence, I’m inclined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me[.]

Here, the narrator is referring to something that was told to him, and his opinion about it. This is the function of a first person narrator—we know he will provide his thoughts and observations throughout the story.

Example 2: Second Person

A popular example of modern fiction with a second-person narrator is Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. The author begins right away by letting you know that the book is simultaneously written to and about you. This is a little hard to understand, so here are a few short excerpts:

You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a winter’s night a traveler. Relax. Concentrate. Dispel every other thought. Let the world around you fade. Find the most comfortable position: seated, stretched out, curled up, or lying flat. Flat on your back, on your side, on your stomach. In an easy chair, on the sofa, in the rocker, the deck chair, on the hassock. It’s not that you expect anything in particular from this particular book. You’re the sort of person who, on principle, no longer expects anything of anything. So, then, you noticed in a newspaper that If on a winter’s night a traveler had appeared, the new book by Italo Calvino, who hadn’t published for several years. You went to the bookshop and bought the volume. Good for you.

The book is written as if the author knows you are there and what you are doing, and knows things about you. It is a difficult, unique style to use successfully, and is thus very rare in literature, but Calvino is famous for it.

Example 3: Third Person

As mentioned, the third person is probably the most widely-used form of narration because it gives authors so much stylistic freedom. In the classic novel A Tale of Two Cities , Charles Dickens uses a third-person narrator who many often consider to be Dickens himself. The story is told from a third-person subjective point of view, where the narrator has access to the thoughts of several characters. Here’s the novel’s famous opening:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way–in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

As you can see, the narrator is describing the “times” of a certain period in history; the setting in which the story will unfold. He also makes it known that he is a witness to the period and the story by using the words “we,” which tells us that the narrator has personal experience when it comes to what he is telling us about.

VII. Related Terms

There are several related terms that we use to discuss a story’s narrator. They all focus on essentially the same thing but are used in different ways.

A narrative is another name for a story, which needs a narrator to tell it. You would say “the narrative is about so and so and is told in the third person.”

Narration is the method of storytelling and the way in which it is told. You would say “the story uses first-person narration,” for example.

Narrative Style

Narrative style is another way to talk about who the narrator is—it’s the style in which the story is told. You would say “the narrative style of this story is the third person.”

VIII. Conclusion

In conclusion, the narrator has a defining role in every story. Readers see and understand the story from the point of view of whoever is telling it, and who that is can change everything, from the amount of details we learn, to the level of truth behind the story, to which character we empathize with. Thus, the narrator is a key element of storytelling.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

What is a Narrator? Definition, Examples of Narrators in Literature

Home » The Writer’s Dictionary » What is a Narrator? Definition, Examples of Narrators in Literature

Narrator definition: A narrator is the speaker of a literary text.

What is a Narrator?

Who is the narrator? A narrator is the person from whose perspective a story is told. The narrator narrates the text.

A narrator only exists in fictional texts or in a narrative poem. A narrator may be a character in the text; however, the narrator does not have to be a character in the text.

The point of a narrator is to narrate a story, i.e., to tell the story. What the narrator can and cannot see determines the perspective of the text and also determines how much the reader knows.

Types of Narrators

First Person Narrator

What is a first person narrator? A first person narrator speaks from the first person point of view . The first person narrator’s commentary uses the pronouns “I/we,” “my/our,” “me/us,” “mine/ours.”

The first person narrator is a character in the text because he is telling it from his point of view. Consequently, he is involved in the action of the story or participates in it in some way.

The first person narrator can only tell the audience what he sees. He cannot comment on action that he does not see or experience directly.

Second Person Narrator

The second person narrator is a character in the text because he is telling the story to another person. Consequently, he is involved in the action of the story or participates in it in some way.

The second person narrator is very rare in literature. When used well, the second person narrator makes it seem like he is talking directly to the audience, making the reader feel as though he is a part of the story.

The second person narrator can only tell the audience what he sees. He cannot comment on action that he does not see or experience directly.

Third Person Narrator

What is a third person narrator? A third person narrator speaks from the third person point of view . The third person narrator’s commentary uses the pronouns “he/she/they,” “his/her/their,” and “his/hers/theirs.”

Third Person Limited:

The third person limited narrator is not usually a character in the text because he removed from the action—that is, he does not participate in the action of the text.

He is called a limited narrator because he can only comment on the actions of some individuals. That is, there is some “behind the scenes” action that he does not see. Therefore, his narration is “limited.” He cannot comment on action that he does not see or experience directly.

Third person limited is not a common type of narrator in literature.

Third Person Omniscient:

He is called an omniscient narrator because he can comment on everything every character experiences. Therefore, his narration is “omniscient”. The third person narrator is someone outside the story looking down at everything that is happening.

Third person omniscient is the most common type of narrator.

The Effect of a Narrator

The way an author writes a narrator determines how the text is received. If the narrator is written well, the book will be well written, and vice versa.

A good narrator makes the reader want to continue with the text. Furthermore, a good narrator makes the reader feel like he is fully submerged in the plotline and the lives of the characters.

How Narrators are Used in Literature

Every story has a narrator. Let’s look at a couple popular texts to understand this concept.

The Catcher in the Rye

Author J.D. Salinger’s choice to use a first-person narrator determines the course of the text. Since the story is only viewed through Caulfield’s eyes, it is very difficult to distinguish truth from fiction (because Caulfield is a self-proclaimed “terrific liar”).

The choice to use Caulfield as the narrator has spurred great interest in this novel. Because it is hard to determine truth from Caulfield’s brilliant imagination, the reader is left with many questions as he concludes the text. This is one of the many reasons this text considered a “classic.”

The Grapes of Wrath

This text is written with a third person omniscient narrator. The narrator has access and insight to every character’s thoughts and actions.

John Steinbeck chose this type of narrator specifically for this text. One reason this narrator works effectively is because the text includes intercalary chapters.

The text oscillates between the intercalary chapters and the fictional narration. These intercalary chapters require an omniscient perspective.

Summary: What are Narrators?

Define Narrator: the definition of narrator in literature is the person who narrates or tells the story.

In summary,

- A narrator tells the story.

- There are different kinds of narrators.

Narrators can greatly benefit or greatly harm a story.

- My Storyboards

Narrator: Definition and Examples

Want to create a storyboard like this one?

Try storyboard that.

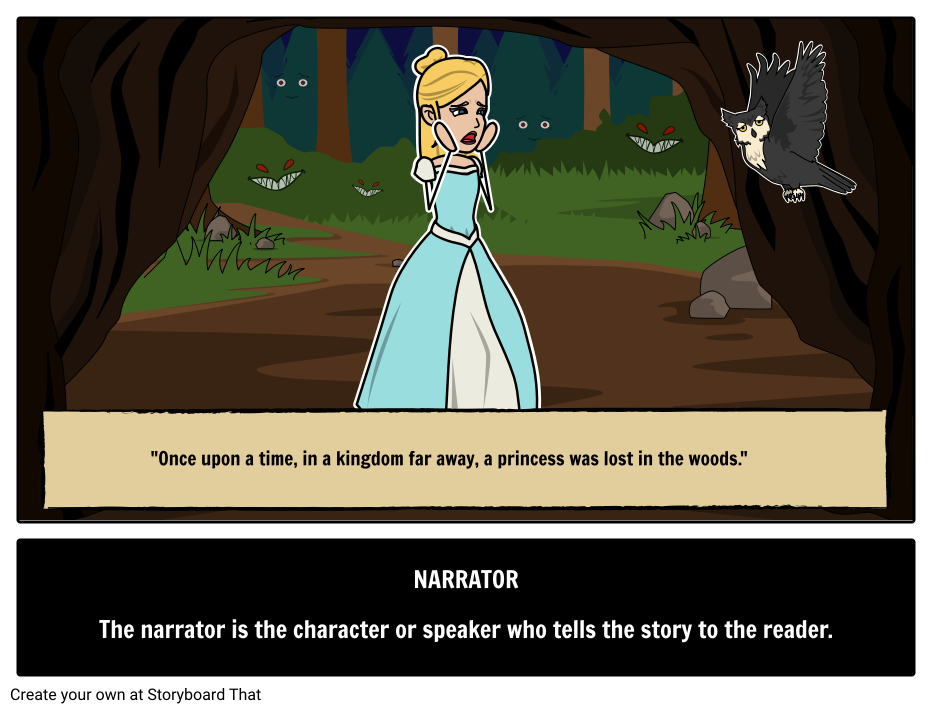

Narrator Definition: The narrator is the character or speaker who tells the story to the reader.

A narrator tells the story to the reader from their perspective in literature , including important plot details like setting, mood, characterization, and conflict. The narrator can be the author, a character from outside of the story, or a character or persona they’ve created within the story. The narrator can use several points of view in which to tell the story such as first person, third person limited, and third person omniscient. First person narrators tell the story using “I” and “me”. Third person omniscient narrators tell the story using “he”, “she”, and “they”, and can access the thoughts of any character. Third person limited narrators use third person pronouns as well; however, they are typically limited to only being able to express the protagonist’s thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Each point of view changes the reader’s access to the information coming from the characters, and may change the story completely, depending on important factors such as bias and experiences.

A narrator can also be unreliable or intrusive. An unreliable narrator’s descriptions of their experiences or events are usually colored or distorted by their own biases or emotions. An intrusive narrator continues to interrupt the story with personal commentary or opinions about characters and events. Both reliable and intrusive narrators usually occur in first person narrations. The narrator’s point of view often shapes the reader’s thoughts and attitudes about the story. For example, in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations , Pip tells the story of his rise and fall from fortune in first person, and by the end of the story, he admits his shame for his egotistical treatment of others along the way, which helps the readers feel empathy and forgiveness for his mistakes.

Create your own Storyboard

Narrator examples.

Holden Caulfield as first person narrator in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye allows the reader to experience Holden’s stream-of-consciousness descent into madness.

”The True Story of the Three Little Pigs” by Jon Scieszka tells the famous children’s tale from the point of view of the wolf. Rather than the wolf chasing the pigs in a hungry rage, he was simply searching for a cup of sugar, but he had a bad cold, too. His blowing down of houses was strictly reserved to his sneezing fits. This point of view completely changes the perspective of the story for the reader.

In 1984 by George Orwell, the third person limited narrator only tells the reader Winston Smith’s thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Because the reader and Winston are unaware of the thoughts and feelings of other characters, both are unprepared for the impending betrayals.

In The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, the narrator has the ability to access all of the characters’ thoughts and emotions as a third person omniscient narrator. The reader knows Hester’s quiet attitude of penance, Pearl’s curiosity, Reverend Dimmesdale’s guilt and shame, and Chillingworth’s patient revenge.

In Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness , Conrad uses two narrators: the original narrator, and Marlow, who tells the story of his trip up the Congo River to the narrator. By the end of the novel, Marlow has managed to shift the original narrator’s perspective towards a dark and foreboding feeling about the civilized world.

Try 1 Month For

30 Day Money Back Guarantee New Customers Only Full Price After Introductory Offer

Learn more about our Department, School, and District packages

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Narrator: A Literary Device

The narrator serves as a crucial mediator between the story and the audience, shaping the perspective and influencing the interpretation of the text.

Narrator: Etymology

Table of Contents

The term “narrator” traces its etymological roots to the Latin word “narrare,” meaning “to tell” or “to recount.” The concept of a narrator is fundamental in literary discourse, embodying the voice that communicates the events and experiences within a narrative.

The narrator serves as a crucial mediator between the story and the audience, shaping the perspective and influencing the interpretation of the text. This etymological connection to “telling” underscores the narrator’s role as a storyteller, emphasizing their agency in constructing and conveying the narrative to the reader.

Narrator: Meanings

Narrator: definition of a literary device.

A narrator, as a literary device , is the narrative voice that communicates the events, perspectives, and emotions within a story.

This device encompasses various forms, including first-person, third-person omniscient, and unreliable narrators, each influencing the reader’s interpretation.

The narrator’s role extends beyond storytelling, shaping the narrative’s tone , atmosphere, and thematic depth, serving as a crucial mediator between the text and the reader.

Narrator: Types

Narrator in everyday life.

- Internal Monologue : The constant inner dialogue or self-talk that narrates our thoughts, feelings, and reactions throughout the day, helping us process experiences.

- Reflective Commentary: When we mentally recount events or discuss them in our minds, providing a narrative structure to our memories and shaping our understanding of personal experiences.

- Decision-Making Narration: The internal deliberation and reasoning we engage in when making choices, with our internal narrator guiding us through pros, cons, and potential outcomes.

- Emotional Narration: The way our internal narrator influences our emotional responses to situations, providing interpretations and judgments that contribute to our overall mood.

- Problem-Solving Dialogue: Engaging in mental conversations with ourselves to analyze problems, consider solutions, and plan actions, often involving a back-and-forth exchange of ideas.

- Narrative Memory Retrieval: When our internal narrator retrieves and recounts memories, shaping the way we perceive past events and influencing our sense of identity.

- Self-Reflective Narration: Moments of introspection where the internal narrator helps us reflect on our beliefs, values, and personal growth, contributing to a continuous narrative of self-awareness.

- Social Interaction Preparation: Anticipating and rehearsing social interactions through mental dialogue, considering potential responses and scenarios to navigate conversations effectively.

- Narration of Learning Processes: When we guide ourselves through the process of learning or acquiring new skills, using internal narration to understand, practice, and master various tasks.

- Dream Narration: The internal storytelling that occurs during dreams, where our minds construct narratives that may be fantastical, symbolic, or reflective of our subconscious thoughts and emotions.

Narrator Examples from Literature

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald: The novel is narrated by Nick Carraway, who serves as both a participant and an observer in the events surrounding Jay Gatsby. Nick’s first-person perspective provides insights into the complex characters and the extravagant world of the Roaring Twenties.

- To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee: Scout Finch, the young protagonist, narrates the novel in the first person. Her innocence and evolving understanding of societal issues offer a unique lens through which readers explore racial injustice and moral growth in the American South.

- The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger: Holden Caulfield’s first-person narration offers a raw and authentic portrayal of teenage angst and alienation. His distinctive voice captures the challenges of navigating the transition from adolescence to adulthood.

- One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez: The novel employs a third-person omniscient narrator, providing a comprehensive view of the Buendía family’s multi-generational saga in the fictional town of Macondo. The narrator seamlessly weaves magical realism into the narrative.

- Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad: The novella is narrated by Marlow, who recounts his journey into the African Congo. Marlow’s narrative style, coupled with the framing device of a boat on the Thames, adds layers of meaning to the exploration of colonialism and human nature.

- The Tell-Tale Heart by Edgar Allan Poe: The short story is narrated by an unnamed and unreliable narrator who tries to convince the reader of their sanity while describing the murder they have committed. The narrative technique heightens the psychological horror and suspense in Poe’s classic tale.

Narrator: Suggested Readings

- Booth, Wayne C. The Rhetoric of Fiction . University of Chicago Press, 1961.

- Genette, Gérard. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method . Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Banfield, Ann. Unspeakable Sentences: Narration and Representation in the Language of Fiction . Routledge, 1982.

- Chatman, Seymour. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film . Cornell University Press, 1978.

- Prince, Gerald. A Dictionary of Narratology . University of Nebraska Press, 1987.

- Phelan, James, and Peter J. Rabinowitz. A Companion to Narrative Theory . Wiley, 2005.

Read more on Literary Devices below:

- Diatribe: A Literary Device

- Diatribe in Literature

- Deuteragonist: A Literary Device

- Deuteragonist in Literature

- Dichotomy: A Literary Device

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notes, tutorials, exercises, thoughts, workshops and resources about writing or storytelling art

Entries with the tag: Types of Narrators

Discover the different types of point of view for narration and see which one fits the best into your writing.

Types of Narrators (6): The First-Person Narrator

In this part of the tutorial about the types of narrators , I’ll analyze the first-person narrator which is the one widely used in contemporary literature. What distinguishes him from the witness narrator, who also resorts to the first person, is the fact that this narrator is the protagonist talking about himself (or herself) and his circumstances. There are quite a lot of first-person novels. Paul Auster’s Moon Palace and Oracle Night , J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye , or Philippe Claudel’s Brodeck’s Report are well-known examples.

In addition, the first-person narrator is often used in crime fiction. This is the case of in the novels written by Jeff Lindsay about the serial killer Dexter. Nevertheless, we can also find this type of narrator in the epistolary genre, personal diaries, biographies, internal monologues, etc. Regardless of the literary genre, here are some general features that can help us determine if the first-person narrator fits our story:

Types of Narrators (5): The Second-Person Narrator

TThe second-person narrator, though not very common, is present in literature and media. For example, the posts I publish online are directed at my readers. This is why I resort to the second-person narrator.

This type of narrator is also typical of the epistolary form; in fact, many novels contain letters or emails the characters send to each other. Nevertheless, the addressee of the second-person narrations I want to analyze in this section are not characters, but the readers themselves.

For instance, in Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler , the second-person narrator acts as the master in a role-playing game attempting to get the reader to identify with the main character. A much more recent example is Paul Auster’s Winter Journal . This fictionalized autobiography is written in the second person as a way of putting the reader in the writer’s shoes. Through this technique, the author wants to show the emotions and experiences he has gathered throughout his life could be those of any other person in the world. The opening line of the book is a clear declaration of intent:

Types of narrator: The Witness Narrator

In the first page of Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose , the narrator makes a declaration of intent: “I prepare to leave on this parchment my testimony as to the wondrous and terrible events that I happened to observe in my youth, now repeating all that I saw and heard, without venturing to seek a design, as if to leave to those who will come after (if the Antichrist has not come first) signs of signs, so that the prayer of deciphering may be exercised on them.”

You just read the words of a witness narrator which is a role played by a character who tells the story in the third person (he isn’t the protagonist) and has the point of view of someone who has witnessed it either from the inside or from the outside. This type of narrator doesn’t usually write about himself or herself.

There are many different types of witness narrators, each with his distinctive features. Here are the most common ones:

Types of Narrators: Third-Person Subjective Narrator

This type of narrator may be confused with the omniscient narrator, but the difference between them is the third-person subjective narrator adopts the point of view of one of the characters of the story.

Thus, his or her vision is limited. He’ll have insight into what a character is thinking or feeling, but he will only have a superficial knowledge of the other characters. Nevertheless, the third-person subjective narrator will always be wiser than a first-person narrator as he can describe his chosen hero from both inside and outside perspectives.

Types of Narrators:The Omniscient Narrator

In this second post of the series, you’ll learn more about the all-knowing and all-seeing omniscient narrator who conveys the facts from a third-person point of view and doesn’t take part in the story.

As the name suggests, this god-like narrator knows everything about the characters and the plot. In addition, he or she is able to predict the future and make assumptions and judgments. The use of this omniscient point of view was very common in nineteenth-century novels.

Let’s take a careful look at the omniscient narrator’s features:

Types of Narrators: Point of View in Fiction Writing

The “once-upon-a-time” stories of your childhood already taught you that in order to tell a story, you need a narrator who transmits it to the reader. Every text (even articles or reports) has a narrator. That is, they’re told from a specific point of view with a particular approach and a distinct tone.

Thanks to the narrator, you can describe characters and settings, convey emotions, insert dialogues, express opinions, and ration information to create suspense or intrigue.

How to Use Dialogue Tags Properly

Since dialogue belongs to the characters, the narrator’s remarks can sometimes spoil it. However, they become necessary in a long conversation or in a dialogue with many members. If you want to know how to use them, here is a list of helpful tricks:

1. Brevity is the soul of wit.

As readers, we all are used to expressions such as “said John,” “asked Mary,” or “replied Sue,” but they should be used carefully because they slow down the reading pace. The same goes for adverbs or unnecessary explanations. As an example, look at this dialogue:

Don't miss it!

Join our mailing list and don't miss any of our posts. Directly to your email box so you can plan ahead and read us anytime.

- Creating Fictional Characters

- Creative Writing Exercises

- News and Interviews

- Once upon a time

- Writing Techniques

- Writing Tips From Writers

- Writing Tools

- Writing tutorial

A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

tumsasedgars / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

In writing or speech , narration is the process of recounting a sequence of events, real or imagined. It's also called storytelling. Aristotle's term for narration was prothesis .

The person who recounts the events is called a narrator . Stories can have reliable or unreliable narrators. For example, if a story is being told by someone insane, lying, or deluded, such as in Edgar Allen Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart," that narrator would be deemed unreliable. The account itself is called a narrative . The perspective from which a speaker or writer recounts a narrative is called a point of view . Types of point of view include first person, which uses "I" and follows the thoughts of one person or just one at a time, and third person, which can be limited to one person or can show the thoughts of all the characters, called the omniscient third person. Narration is the base of the story, the text that's not dialogue or quoted material.

Uses in Types of Prose Writing

It's used in fiction and nonfiction alike. "There are two forms: simple narrative, which recites events chronologically , as in a newspaper account;" note William Harmon and Hugh Holman in "A Handbook to Literature," "and narrative with plot, which is less often chronological and more often arranged according to a principle determined by the nature of the plot and the type of story intended. It is conventionally said that narration deals with time, description with space."

Cicero, however, finds three forms in "De Inventione," as explained by Joseph Colavito in "Narratio": "The first type focuses on 'the case and...the reason for dispute' (1.19.27). A second type contains 'a digression ...for the purpose of attacking somebody,...making a comparison,...amusing the audience,...or for amplification' (1.19.27). The last type of narrative serves a different end—'amusement and training'—and it can concern either events or persons (1.19.27)." (In "Encyclopedia of Rhetoric and Composition: Communication from Ancient Times to the Information Age," ed. by Theresa Enos. Taylor & Francis, 1996)

Narration isn't just in literature, literary nonfiction, or academic studies, though. It also comes into play in writing in the workplace, as Barbara Fine Clouse wrote in "Patterns for a Purpose": "Police officers write crime reports, and insurance investigators write accident reports, both of which narrate sequences of events. Physical therapists and nurses write narrative accounts of their patients' progress, and teachers narrate events for disciplinary reports. Supervisors write narrative accounts of employees' actions for individual personnel files, and company officials use narration to report on the company's performance during the fiscal year for its stockholders."

Even "jokes, fables, fairy tales, short stories, plays, novels, and other forms of literature are narrative if they tell a story," notes Lynn Z. Bloom in "The Essay Connection."

Examples of Narration

For examples of different styles of narration, check out the following:

- The Battle of the Ants by Henry David Thoreau (first person, nonfiction)

- "The Holy Night" by Selma Lagerlöf (first person and third person, fiction)

- Street Haunting by Virginia Woolf (first person plural and third person, omniscient narrator, nonfiction)

- Definition and Examples of Narratives in Writing

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- Third-Person Point of View

- Understanding Point of View in Literature

- AP English Exam: 101 Key Terms

- What Is a Novel? Definition and Characteristics

- Introduction to Magical Realism

- Organizational Strategies for Using Chronological Order in Writing

- How to Summarize a Plot

- How to Write a Narrative Essay or Speech

- Narratio in Rhetoric

- 5 Easy Activities for Teaching Point of View

- What Is Narrative Poetry? Definition and Examples

- Compose a Narrative Essay or Personal Statement

- What Is Narrative Therapy? Definition and Techniques

Narrative Definition

What is narrative? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A narrative is an account of connected events. Two writers describing the same set of events might craft very different narratives, depending on how they use different narrative elements, such as tone or point of view . For example, an account of the American Civil War written from the perspective of a white slaveowner would make for a very different narrative than if it were written from the perspective of a historian, or a former slave.

Some additional key details about narrative:

- The words "narrative" and "story" are often used interchangeably, and with the casual meanings of the two terms that's fine. However, technically speaking, the two terms have related but different meanings.

- The word "narrative" is also frequently used as an adjective to describe something that tells a story, such as narrative poetry.

How to Pronounce Narrative

Here's how to pronounce narrative: nar -uh-tiv

Narrative vs. Story vs. Plot

In everyday speech, people often use the terms "narrative," "story," and "plot" interchangeably. However, when speaking more technically about literature these terms are not in fact identical.

- A story refers to a sequence of events. It can be thought of as the raw material out of which a narrative is crafted.

- A plot refers to the sequence of events, but with their causes and effects included. As the writer E.M. Forster put it, while "The King died and the Queen died" is a story (i.e., a sequence of events), "The King died, and then the Queen died of grief" is a plot.

- A narrative , by contrast, has a more broad-reaching definition: it includes not just the sequence of events and their cause and effect relationships, but also all of the decisions and techniques that impact how a story is told. A narrative is how a given sequence of events is recounted.

In order to fully understand narrative, it's important to keep in mind that most sequences of events can be recounted in many different ways. Each different account is a separate narrative. When deciding how to relay a set of facts or describe a sequence of events, a writer must ask themselves, among other things:

- Which events are most important?

- Where should I begin and end my narrative?

- Should I tell the events of the narrative in the order they occurred, or should I use flashbacks or other techniques to present the events in another order?

- Should I hold certain pieces of information back from the reader?

- What point of view should I use to tell the narrative?

The answers to these questions determine how the narrative is constructed, so they have a huge influence on the way a reader sees or understands what they're reading about. The same series of events might be read as happy or sad, boring or exciting—all depending on how the narrative is constructed. Analyzing a narrative just means examining how it is constructed and why it is constructed that way.

Narrative Elements

Narrative elements are the tools writers use to craft narratives. A great way to approach analyzing a narrative is to break it down into its different narrative elements, and then examine how the writer employs each one. The following is a summary of the main elements that a writer might use to build his or her narrative.

- For example, a story about a crime told from the perspective of the victim might be very different when told from the perspective of the criminal.

- For instance, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway were friends, and they wrote during the same era, but their writing is very different from one another because they have markedly different voices.

- For example, Jonathan Swift's essay " A Modest Proposal " satirizes the British government's callous indifference toward the famine in Ireland by sarcastically suggesting that cannibalism could solve the problem—but the essay would have a completely different meaning if it didn't have a sarcastic tone.

- For example, the first half of Charles Dickens' novel David Copperfield tells the story of the narrator David Copperfield's early childhood over the course of many chapters; about halfway through the novel, David quickly glosses over some embarrassing episodes from his teenage years (unfortunate fashion choices and foolish crushes); the second half of the novel tells the story of his adult life. The pacing give readers the sense that David's teen years weren't really that important. Instead, his childhood traumas, the challenges he faced as a young man, and the relationships he formed during both childhood and adulthood make up the most important elements of the novel.

- For example, Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein uses three different "frames" to tell the story of Dr. Frankenstein and the creature he creates: the novel takes the form of letters written by Walton, an arctic explorer; Walton is recounting a story that Dr. Frankenstein told him; and as part of his story, Dr. Frankenstein recounts a story told to him by the creature.

- Linear vs. Nonlinear Narration: You may also hear the word narrative used to describe the order in which a sequence of events is recounted. In a linear narrative, the events of a story are described chronologically , in the order that they occurred. In a nonlinear narrative, events are described out of order, using flashbacks or flash-forwards, and then returning to the present. In some nonlinear narratives, like Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion , there is a clear sense of when the "present" is: the novel begins and ends with the character Viv sitting in a bar, looking at a photograph. The rest of the novel recounts (out of order) events that have happened in the distant and recent past. In other nonlinear narratives, it may be difficult to tell when the "present" is. For example, in Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughterhouse-Five , the character Billy Pilgrim, seems to move forward and backward in time as a result of post-traumatic stress. Billy is not always certain if he is experiencing memories, flashbacks, hallucinations, or actual time travel, and there are inconsistencies in the dates he gives throughout the book—all of which of course has a huge impact on how his stories are relayed to the reader.

Narrative as an Adjective

It's worth noting that the word "narrative" is also frequently used as an adjective to describe something that tells a story.

- Narrative Poetry: While some poetry describes an image, experience, or emotion without necessarily telling a story, narrative poetry is poetry that does tell a story. Narrative poems include epic poems like The Iliad , The Epic of Gilgamesh , and Beowulf . Other, shorter examples of narrative poetry include "Jabberwocky" by Lewis Carrol, "The Lady of Shalott" by Alfred Lord Tennyson, "The Goblin Market" by Christina Rossetti, and "The Glass Essay," by Anne Carson.

- Narrative Art: Similarly, the term "narrative art" refers to visual art that tells a story, either by capturing one scene in a longer story, or by presenting a series of images that tell a longer story when put together. Often, but not always, narrative art tells stories that are likely to be familiar to the viewer, such as stories from history, mythology, or religious teachings. Examples of narrative art include Michelangelo's painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the Pietà ; Paul Revere's engraving entitled The Bloody Massacre ; and Artemisia Gentileschi's painting Judith Slaying Holofernes .

Narrative Examples

Narrative in the book thief by markus zusak.

Zusak's novel, The Book Thief , is narrated by the figure of Death, who tells the story of Liesel, a girl growing up in Nazi Germany who loves books and befriends a Jewish man her family is hiding in their home. In the novel's prologue, Death says of Liesel:

Yes, often, I am reminded of her, and in one of my vast array of pockets, I have kept her story to retell. It is one of the small legion I carry, each one extraordinary in its own right. Each one an attempt—an immense leap of an attempt—to prove to me that you, and your human existence, are worth it.

Narrators do not always announce themselves, but Death introduces himself and explains that he sees himself as a storyteller and a repository of the stories of human lives. Choosing Death (rather than Leisel) as the novel's narrator allows Zusak to use Liesel's story to reflect on the power of stories and storytelling more generally.

Narrative in A Visit From the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan

In A Visit From the Good Squad , Egan structures the narrative of her novel in an unconventional way: each chapter stands as a self-contained story, but as a whole, the individual episodes are interconnected in such a way that all the stories form a single cohesive narrative. For example, in Chapter 2, "The Gold Cure," we meet the character Bennie, a middle-aged music producer, and his assistant Sasha:

"It's incredible," Sasha said, "how there's just nothing there." Astounded, Bennie turned to her…Sasha was looking downtown, and he followed her eyes to the empty space where the Twin Towers had been.

Because there is an empty space where the Twin Towers had been, the reader knows that this dialogue is taking place some time after the September 11th, 2001 attack in which the World Trade Center was destroyed. Bennie appears again later in the novel, in Chapter 6, "X's and O's," which is set ten years prior to "The Gold Cure." "X's and O's" is narrated by Bennie's old friend, Scotty, who goes to visit Bennie at his office in Manhattan:

I looked down at the city. Its extravagance felt wasteful, like gushing oil or some other precious thing Bennie was hoarding for himself, using it up so no one else could get any. I thought: If I had a view like this to look down on every day, I would have the energy and inspiration to conquer the world. The trouble is, when you most need such a view, no one gives it to you.

Just as Sasha did in Chapter 2, Scotty stands with Bennie and looks out over Manhattan, and in both passages, there is a sense that Bennie fails to notice, appreciate, or find meaning in the view. But the reader wouldn't have the same experience if the story had been told in chronological order.

Narrative in Atonement by Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan's novel Atonement tells the story of Briony, a writer who, as a girl, sees something she doesn't understand and, based on this faulty understanding, makes a choice that ruins the lives of Celia, her sister, and Robbie, the man her sister loves. The first part of the novel appears to be told from the perspective of a third-person omniscient narrator; but once we reach the end of the book, we realize that we've read Briony's novel, which she has written as an act of atonement for her terrible mistake. Near the end of Atonement , Briony tells us:

I like to think that it isn’t weakness or evasion, but a final act of kindness, a stand against oblivion and despair, to let my lovers live and to unite them at the end. I gave them happiness, but I was not so self-serving as to let them forgive me. Not quite, not yet. If I had the power to conjure them at my birthday celebration…Robbie and Cecilia, still alive, sitting side by side in the library…

In Briony's novel, Celia and Robbie are eventually able to live together, and Briony visits them in an attempt to apologize; but in real life, we learn, Celia and Robbie died during World War II before they could see one another again, and before Briony could reconcile with them. By inviting the reader to imagine a happy ending, Briony effectively heightens the tragedy of the events that actually occurred. By choosing Briony as his narrator, and by framing the novel Briony wrote with her discussion of her own novel, McEwan is able to create multiple interlacing narratives, telling and retelling what happened and what might have been.

Narrative in Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse-Five tells the story of Billy Pilgrim, a World War II veteran who survived the bombing of Dresden, and has since “come unstuck in time.” The novel uses flashbacks and flash-forwards, and is narrated by an unreliable narrator who implies to the reader that the narrative he is telling may not be entirely true:

All this happened, more or less. The war parts, anyway, are pretty much true. One guy I knew really was shot in Dresden for taking a teapot that wasn’t his. Another guy I knew really did threaten to have his personal enemies killed by hired gunmen after the war. And so on. I’ve changed all the names.

The narrator’s equivocation in this passage suggests that even though the story he is telling may not be entirely factually accurate, he has attempted to create a narrative that captures important truths about the war and the bombing of Dresden. Or, maybe he just doesn’t remember all of the details of the events he is describing. In any case, the inconsistencies in dates and details in Slaughterhouse-Five give the reader the impression that crafting a single cohesive narrative out of the horrific experience of war may be too difficult a task—which in turn says something about the toll war takes on those who live through it.

What's the Function of Narrative in Literature?

When we use the word "narrative," we're pointing out that who tells a story and how that person tells the story influence how the reader understands the story's meaning. The question of what purpose narratives serve in literature is inseparable from the question of why people tell stories in general, and why writers use different narrative elements to shape their stories into compelling narratives. Narratives make it possible for writers to capture some of the nuances and complexities of human experience in the retelling of a sequence of events.

In literature and in life, narratives are everywhere, which is part of why they can be very challenging to discuss and analyze. Narrative reminds us that stories do not only exist; they are also made by someone, often for very specific reasons. And when you analyze narrative in literature, you take the time to ask yourself why a work of literature has been constructed in a certain way.

Other Helpful Narrative Resources

- Etymology: Merriam-Webster describes the origins and history of usage of the term "narrative."

- Narrative Theory: Ohio State University's "Project Narrative" offers an overview of narrative theory.

- History and Narrative: Read more about the similarities between historical and literary narratives in Hayden White's Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th-Century Europe.

- Narrative Art: This article from Widewalls explores narrative art and discusses what kind of art doesn't tell stories.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Point of View

- Anthropomorphism

- Falling Action

- Polysyndeton

- Stream of Consciousness

- Colloquialism

- Verbal Irony

- Foreshadowing

- Common Meter

- Round Character

- Characterization

- Anachronism

How to Read and Enjoy the Classics

- Thoughts on the Greats

- How to Read Poetry

- How to Read Fiction

- Why Literature?

- Lists and Timelines

- Literature Q & A

All About Narrators: Who’s Telling This Story, Anyway?

Tere Marichal, storyteller from Puerto Rico, telling the Afro-Caribbean folktale of Anansi at Biblioteca Juvenil de Mayag during a Multicultural Childrens Book Day.

How to Read Fiction Step 5: Narrators and Point of View

Wading into a new fiction, it’s natural to size up the characters and get a bead on the story line. Who’s the central character? What is her problem or goal? Then off we go, following the storyline up and down until we find out how it all comes out in the end.

But before launching out into the plotline, there’s one big question we need to ask first, and keep asking all the way through: who is telling this story, anyway?

Is it someone who is in the story with a limited view of events, or someone outside looking omnisciently down? Is it someone we can trust or someone we must question?

A work of fiction is not just a description of a series of incidents; it is a description of a series of incidents as told by a particular teller. Sometimes a fiction is more about the teller than it is about the events in the storyline itself. Whatever the narrator choice or mode of telling, this important aspect of great fiction is something we don’t want to miss.

In this post I’m going to talk about the many different types of narrators an author could choose when constructing a fiction, and how that artistic choice influences the story that we experience as readers.

How to Read Fiction Series

Step 1: Style

Step 2: Theme

Step 3: Plot

Step 4 Part 1: Characterization Techniques

Step 4 Part 2: More Characterization Techniques

Step 6: Tone in Fiction

Playing with Narrator Perspectives: TV and Film

Narrator perspective is hardly an unfamiliar concept these days because so many television and film scripts are built around it. Often the whole point of a tale is to show how individuals seldom describe events without bias but rather filter events through their own perspectives, often to present themselves in the most favorable light.

Most folks have heard of the awarding-winning 1950 Japanese film Rashomon , famous for doing exactly that. This great film tells the story of a bandit who murders a travelling samurai and rapes his wife. The story is re-told by four narrators, the bandit, the wife, the ghost of the samurai, and finally by a woodcutter who witnessed the incidents. Each tells the story differently as each narrator tries to make him or herself look good while the other characters look bad. The film is a serious look at the difficulty of arriving at justice given that witnesses are unreliable to one degree or another.

In a lighter mode: back in the 90s I enjoyed watching the television show X-Files . I’ve always remembered the “Bad Blood” episode (12th episode of season 5) because of its comic use of narrator perspective. In the episode, Agents Mulder and Scully have to track down an apparent vampire who is killing people in a small town.

In the course of the episode, the tale is told two different ways, once from Agent Mulder’s perspective and once from Agent Scully’s. Their descriptions of events, and especially of the small-town sheriff who figures in the tale, differ quite a lot based on the prejudices and opinions of each. Result? Both comedy and complexity.

Anderson and Duchovny, actors who played Scully and Mulder in X-Files, at 2013 Comic Con Convention for 20th Anniversary of the show.

Types of Narrators and Point of View in Great Fiction

What film and TV are doing now, great fiction writers did first: to create narrators who filter and shape the story we read or experience. A writer’s choice of narrator controls everything about how a story is told, starting with the POINT OF VIEW from which we can view the story. What are the types of narrators and points of view that writers can choose from?

Most often, fiction writers choose either first person narrators or third person narrators:

A first person narrator speaks from the “I” or “we” perspective. Most often, a first person narrator is a character within the story, usually but not necessarily the central character (protagonist). First person narrators offer only a limited POINT OF VIEW —that is, the writer can portray only events and thoughts accessible to that narrator character. Note that there are some ways around this limitation, though, discussed below.

A third person narrator is not usually a character in the story but merely a voice relating events, describing characters from a “they” perspective. Third person narrators can be neutral, anonymous, and unnoticeable. They can also be very much the opposite, personable and discursive, as if seeking a relationship directly with “dear readers.”

Third person narrators can offer an OMNISCIENT POINT OF VIEW , which means that they know everything about all the characters, both their actions and their thoughts. But third person narrators can also have a LIMITED POINT OF VIEW , relating the story as if showing it like a movie camera would if it were positioned behind or inside the head of a particular character.

The second person narrator , who speaks directly to readers as “you” while making the reader a character within the story, is a rare narrator type. This narrator also has a limited POINT OF VIEW, able to report only the events that can be experienced personally by both narrator and readers as they have become characters within the story.

Questions to Ask About Narrators

Once you know about the different types of narrators writers can choose, it’s fun to do a little analysis of how they used these options to structure their particular tale. When you first wade into a new fictional tale, you can ask yourself what type of narrator it has and how that choice shapes the story.

If the narrator is first person, why would an author want to limit point of view to one or two characters? Why choose that particular character? How would the story be different if told from a different character’s point of view?

If the narrator is third person, is the point of view Omniscient or Limited? If Limited, in what way? Why might an author choose to limit the point of view?

What are characteristics the narrative voice itself? Does the narrator seem to disappear into the tale, or does the writer fashion a prominent, talkative voice for the narrator? If the narrative is in second person, what are the impacts of including the reader into the story as an actual character? Why might a writer choose this narrative method?

How much does this narrator try to directly control readers? Does the narrative voice instruct readers on all aspects of the tale, including how to interpret each character’s thoughts and actions, or does the narrator just report and describe without offering an interpretation, leaving readers to analyze for themselves?

Read on for more discussion and examples of each type of narrator.

First Person Narrators

In many famous works, the whole personality of the fiction derives from the personality of the narrator, so it’s easy to call to mind many famous ones: Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Bronte’s Jane Eyre, Dickens’s David Copperfield, or Salinger’s Holden Caulfield. These first person narrators are the people we care most about within their own stories. We see their whole story from their perspective and are therefore naturally sympathetic with their aims and struggles.

As savvy reader, it’s interesting to consider why an author might have chosen a particular character rather than another as the first person narrator who would tell the tale. Why Jane instead of Rochester or Helen? Why David instead of Aunt Betsy or Agnes? Why Huck instead of Tom or Jim? How might the story be entirely different if told by another? Often later writers play with the original writer’s choice by re-telling a famous story from a different character’s perspective, as Jean Rhys did when she re-told Jane Eyre’s story through Bertha’s eyes in Wide Sargasso Sea .

Sometimes the first person narrator is not the central character, or protagonist, in the story. Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby is a famous example. Gatsby, and possibly Daisy, are the central figures in the story Nick is telling. It’s especially interesting to think about why Fitzgerald fashioned Nick to be narrator rather than let Gatsby, the central figure, narrate the tale. If Gatsby had told his own story, we might hear the tale of a self-made man who was proud of cutting corners to rise to the top, because he did it all for love, to win Daisy. Nick only partially holds that view, seeing the story as a whole from more complex and shifting perspectives.

Early Novelists and First Person Narrators

First person narrators were uncommon in fiction before the development of realism. For early Realist novelists of the 18th century, First Person probably seemed like the obvious choice to make a fiction seem more real to readers. First person narrators make a fiction seem like a real memoir of actual events–not “once upon a time in a kingdom far away,” but “I, this person, was there and did these things.” Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders are both famous early examples of first person narrators who tell their fictional tales as if they were real people.

Epistolary Novelist Samuel Richardson with Family

Other famous 18th century writers made use of the “epistolary fiction” device. Epistolary Fictions are works told in the form of letters (“epistles”) written by different characters. Famous fictions using this technique include Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Clarissa, and Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphry Clinker . In his Clarissa , Richardson was able to achieve subtle and extensive character portraits of four very different people, Clarissa, a beautiful persecuted lady, Lovelace, her would-be seducer, Anna, Clarissa’s friend, and Belford, Lovelace’s friend, by writing numerous letters from each character’s perspective.

In Tobias Smollett’s The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, four characters go on a pleasure journey around Britain and Scotland led by Welsh squire Matthew Bramble. Accompanying him are his unmarried older sister Tabitha, their niece Liddy, their nephew Jemmy, and Tabitha’s maid Winifred.

All four characters write letters to their friends, revealing very different perspectives on the different events in the narrative. For instance, when they visit the big London pleasure garden at Vauxhall, Squire Matthew writes his friend how tacky and frightful the place is, full of kitschy art and annoying, yammering people. His young niece Liddy, on the other hand, writes to her girlfriend about what a magical fairyland the place is, with lanterns, statuary, and beautifully dressed elegant people everywhere.

Clinker was one of Dickens’s favorite works, probably because of the comedy Smollett achieved by juxtaposing the different characters’ views of each event which varied according to their personal preoccupations and capabilities.

Epistolary Fiction didn’t disappear after the 18th Century, though it became less common. Some famous later examples include The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins and Dracula by Bram Stoker, both of which rely on letters and diary entries to convey portions of the story. In America, we find the famous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, in which the story of a depressed woman’s breakdown is conveyed by means of diary entries, which are very similar to letters. In the 20th century we find Possession by A. S. Byatt, in which the romance between two famous 19th century poets is revealed through their letters, uncovered by two 20th century scholars who read and interpret them a century later.

Second Person Narrators

A second person narrator uses the word “you” and speaks directly to the reader, therefore making the reader a direct part of the fictional interaction. It’s equivalent to “breaking the fourth wall” in drama or film, when the actors turn directly to the viewer and involve them directly into the action of the film.

Second person seems natural when giving directions or attempting to persuade a reader (“Next you crack the egg and put it in the batter,” or “Now you will experience the comfortable ride of this great automobile”). However, Second Person seems awkward and contrived within a fiction, so few writers in the Western tradition have made use of it.

There are a few exceptions, though, mostly in short fiction rather than in novels. I like Daniel Orozco’s “Orientation, ” a short story in which the second person narrator is giving a new employee, who is “you” the reader, a tour of the office, while sharing all kinds of crazy and distorted gossip about the people who work there.

Another use of second person narrators is in video games or “choose your own adventure” books, wherein the reader becomes a character within the story and is allowed to make choices that can send the narrative in different directions.

Although second person narration has produced a few interesting fictions, to me it feels contrived and unnatural. When the reader becomes a character, the reader can influence the shape of the tale by making different choices, which leaves the resulting shape of the narrative somewhat out of the writer’s control.

The result, to me, is seldom a polished work of art but more of a fun imagination game or perhaps a thought experiment. If you know of an exceptional work of fiction employing a second person narrator, I would love to hear about it. Leave a note in the comments!

Third Person Narrators

House of Bilbo Baggins from New Zealand set of “The Lord of the Rings” film.

Anonymous Third Person Narrators

Narrating a story in third person is a very old kind of storytelling indeed, going back to ancient tales older than “Once Upon a Time” itself. Third person narrative voices convey every element of a story for readers, providing details of setting, characters, conflict, plot events, reporting dialogue and any background details readers need to understand what is happening.

J. R. R. Tolkien provides us with a great example of this kind of narrator in The Lord of the Rings . With his charming descriptions and omniscient (all knowing) point of view, this narrator roves all over Middle Earth to stand behind one character after another at different times and places. He can tell readers the inner thoughts of most of them, reserving reports only when needed to produce suspense; he can also tell readers any needed background information, such as the general opinions of a character’s neighbors, as he does here in the opening chapter of The Fellowship of the Ring .

Notice that though the narrative voice is distinctive, Tolkien does not draw the reader’s attention to the narrator, but rather directs attention to the scenes and characters he wants them to imagine:

When Mr. Bilbo Baggins of Bag End announced that he would shortly be celebrating his eleventy-first birthday with a party of special magnificence, there was much talk and excitement in Hobbiton. Bilbo was very rich and very peculiar, and had been the wonder of the Shire for sixty years, ever since his remarkable disappearance and unexpected return. The riches he had brought back from his travels had now become a local legend, and it was popularly believed, whatever the old folk might say, that the Hill at Bag End was full of tunnels stuffed with treasure. And if that was not enough for fame, there was also his prolonged vigour to marvel at. Time wore on, but it seemed to have little effect on Mr. Baggins. At ninety he was much the same as at fifty. At ninety-nine they began to call him well-preserved, but unchanged would have been nearer the mark. There were some that shook their heads and thought this was too much of a good thing; it seemed unfair that anyone should possess (apparently) perpetual youth as well as (reputedly) inexhaustible wealth. –Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring , Chapter 1.

Here, we can see how Tolkien focuses the reader’s attention less on the narrative voice and more on Mr. Baggins and what his neighbors thought of him.

“Dear Reader”: Non-Disappearing Third Person Narrators

“George Eliot” (Mary Ann Evans) at age 30. Painting by d’Albert Durade.*

Not all third person readers are so anonymous. Nineteenth century classic fiction is famous for narrators of the “Dear Reader” school—that is, narrators who have characteristics as prominent as any of the characters in the novel. These narrators use their third person privileges to speak directly to readers, offering their opinions not just on characters and events in the story, but also on what they think the readers will think of those characters, or indeed, on any topics that might seem related to the story at all.

These writers seem to be reaching out to readers in friendship, trying to make a direct connection from writer to reader. It’s important to keep in mind, though, that the “friendly” narrator is not the actual writer who speaks to readers in her own voice. The chatty third person narrator is still a fiction, as much of a character creation as any of the other fictional people in the novel. For instance, some of George Eliot’s fictions feature narrators who are male, even though she, the writer (whose real name is Mary Ann Evans), was not.

That said, it’s still true that narrators who speak directly to readers spawn a kind of closeness between reader and writer, a sense that we readers have connected with the actual author. And indeed, I personally get a sense of the writer’s actual character more from these types of narrators than from any other type, and really enjoy reading their works because of that.

George Eliot/Mary Ann Evans (mentioned above) and Anthony Trollope are both famous for using this kind of narrator. Eliot’s narrative voice is that of a wise and earnest friend, who often pauses in the midst of an event or conversation in the story to talk directly to readers about everything that’s going on. She might ask readers to pardon her for too much detail, or to take warning from characters, to gently call readers out for hypocrisy in their likely judgments, or even to consider what readers can learn from the fictional situation.

Eliot’s narrators also tell us all about how other people in fictional town or village feel about the characters and their doings, thus creating a complex picture of whole social networks involving people from all different social classes and walks of life. Trollope does much the same with his narrators, though usually in a lighter tone and more of a focus on making comic observations about characters and what is going on in the tale.

Both Eliot and Trollope assume omniscience as their point of view. To learn more about the work of each of these writers, take a look at these posts below. For yet another type of third person “direct-to-reader” narrator voice, read Thackeray’s Vanity Fair , in which the third person omniscient narrator isn’t just chatty; he can get positively snarky and sardonic.

Trollope’s The Warden: Empathy v. The Media

Dorothea’s Brook in Middlemarch: Moral Streams and Ripples

Controlling Omniscient Narrators

Some writers fashion narrators who exert little noticeable control over readers. They just report on events, describing scenes and characters without explaining or urging readers to interpret or judge them a particular way. But other fictions have narrators that tell readers everything about what to think and feel about the story. In life we usually dislike people who are too controlling, but in art, including written art, control is not always bad.

D. H. Lawrence.

D. H. Lawrence, for instance, often deploys a controlling and dominant narrative voice to create powerful effects in fiction. His brilliant and moody short story “The Horse Dealer’s Daughter” is one good example of an extremely controlling narrator.

Lawrence’s Freudian-esque theory of human personality underlies this tale of two people who fall in love completely against their will. This theory that people are controlled by powerful unconscious forces renders them incapable of explaining any of their thoughts or motivations, because they don’t really understand themselves at all. Thus Lawrence’s all -knowing narrator steps in to do it for them.

His third person omniscient narrator describes the scene, creates the mood, and shares in-depth detail about each character, including their inner psyches, lacing the language with metaphor and poetic diction. The result, as in so much of Lawrence’s writing, is moody, moving, and perceptive, yet still leaving readers a lot to ponder about what love really is.

Third Person Narrators with Limited Point of View

Sometimes fiction writers use third person narration but choose to limit how much that narrator seems to know about characters or events. The narrator’s point of view is limited, perhaps just to one character’s mind, or to one setting or to a specific period of time.

By doing this, the author can more easily create suspense or mystery by keeping readers as much in the dark as most of the characters are. Sometimes limited point of view can draw readers deeper into the story as they struggle to figure out what is going on from the limited information they have. That causes them to think more deeply about characters and themes the author might want to discuss.

In Shirley Jackson’s famous short story “The Lottery,” her dispassionate and restrained narrator is limited to a point of view that seems to hover above the town square, where people are ominously gathering on a beautiful June day in a small village to do. . . what? The narrator does not explain.

This narrative voice reports no one’s inner thoughts, no past history, and no subsequent results after the events. It merely reports characters’ actions and speeches when they occur, as if a camera is perched above the gathering, broadcasting to the ether while events proceed. As the story unfolds and actions become clearly more sinister, this calm unemotional narrative voice seems not just mysterious but positively chilling.

Another famous short story with limited point of view is “Hills Like White Elephants” by Ernest Hemingway . Like Jackson’s narrator, Hemingway’s narrator reports only a few details of the setting, what the characters do, and what they say. Readers must figure out who the characters might be, and even the topic of conversation (which, though never explicitly mentioned, is the man’s desire for the woman to get and abortion and her resistance).

Austen’s Indirect Discourse

Jane Austen

Brilliantly comedic author Jane Austen invented a particular kind of limited third person narration often called “indirect discourse.” Though her narrator speaks in third person, which might suggest to readers that the narrator is omniscient, she might be limiting the narrator to just one character’s thoughts and point of view.

She used indirect discourse to particularly brilliant effect in Emma . For almost the whole first half of the novel, she narrates in third person but restricts her point of view to Emma’s mind without letting the reader know that specifically. Thus first time readers can get fooled into thinking that Emma’s views on everything are correct; but when all her surmises start coming untrue, the little picture as summed up by Emma unravels, and readers must re-think their interpretations of all the events coming before.

Austen’s indirect discourse in Emma is a brilliant comedic device, but also a means of drawing attention to a serious theme: it is so easy for humans to think they have figured everything out, totally unaware that they formed their views filtered through their own prejudices and desires.

Writers might check out this blog post for interesting tips on creating their own third person narrators.