How to Write a Feature Story: Step-By-Step

This article gives a step-by-step process that can be used when writing feature articles. Read more and learn how to write a feature story effectively.

Feature stories are long-form non-fiction news articles that go into detail on a given topic. The most common type of feature stories are human interest stories, interviews and news features.

All of the best feature writers know that their articles live and die on the information that is detailed within the story. However, it requires more than just quality research to create a strong feature article.

You also need to understand how to get the reader’s attention from the first paragraph, as well as how to format the body of the article, and how to write a strong conclusion. It also helps if you have a flair for creative writing, as the style involved isn’t as rigid as traditional news stories.

If all this sounds complex, then don’t fret. There is a step-by-step process that can be used when writing feature articles.

Before we share that template, let us first take a quick look at a few of the different genres of this type of story format.

1. Human Interest

2. news features, 3. lifestyle features, 4. seasonal features, 5. interview pieces, 6. color stories, 7. profile features, 8. behind the scenes, 9. travel features, 10. instructional features, something completely different, steps for writing a feature writing, 1. evaluate your story ideas, 2. do your research, 3. decide the type of feature you want to write, 4. select an appropriate writing style, 5. craft a compelling headline, 6. open with interest, 7. don’t be afraid to be creative, writing a feature story: the last word, 10 different types of feature articles.

As the title suggests, when writing human interest stories, the focus is on people. There is usually a strong emphasis on emotion within these stories.

These feature stories can involve a personal goal, achievement, or a dramatic event within someone’s (or a group of people’s) life.

It can also just be a general story about the trials and tribulations of everyday life.

Examples: ‘The leather jacket I bought in my 20s represents a different woman. I just can’t let it go’, ‘I wish I had Rami Malek as a role model growing up – I was stuck with the Mummy’.

News features are probably the most common type of feature article. Within these, there is a strong emphasis on a current event, with the story explaining the reasons behind these events.

They may also go on to examine the implications behind the news stories.

Examples: ‘Eastern Europe’s business schools rise to meet western counterparts’, MBA by numbers: Mobility of UK graduates’.

Lifestyle features usually centre around life and how it can be lived better. For instance, an example of a lifestyle feature would be ‘Six Workouts You Have to Try This Summer’, or ‘Why You Need To Try Meditation’.

Lifestyle features are common within magazines.

Example: Six ways with Asian greens: ‘They’re almost like a cross between spinach and broccoli’ .

These feature articles are specific to certain times of year.

If you work within a newsroom, it is likely that they will have a calendar that schedules the times when certain types of features are due to be written.

One of of the advantages of these types of features is that you can plan them in a way you can’t with typical news stories.

Examples: ‘ 5 Ways to Celebrate the Holidays With The New York Times ’, The Start of Summer .

Interview features have commonalities with other types of features, but are set apart as they are centred around a single interview.

A good way to strengthen this type of article is to share background information within the it. This information can be either on the interviewee, or the subject that is being discussed.

Examples: Mark Rylance on ‘Jerusalem’ and the Golf Comedy ‘Phantom of the Open’ , ‘I Deserve to Be Here’: Riding His First Professional Gig to Broadway

This is a feature that breaks down the feel and atmosphere of a hard news story.

They often accompany news writing.

Good feature writing here will help the reader imagine what it was like to be a at a certain event, or help them gain further understanding of the issues and implications involved of a story.

Examples: ‘ Why the Central African Republic adopted Bitcoin ’, ‘Admissions teams innovate to find ideal candidates’ .

A profile feature is like a mini-biography.

It tries to paint a picture of a person by revealing not only facts relating to their life, but also elements of their personality.

It can be framed around a certain time, or event within a person’s life, It can also simply be a profile detailing a person’s journey through life.

Examples: Why Ray Liotta was so much more than Goodfellas , Sabotage and pistols – was Ellen Willmott gardening’s ‘bad girl’?

These are features that give readers the inside track on what is happening.

They are particularly popular with entertainment journalists, but are used by feature writers within every sphere.

Examples: ‘‘You Just Have to Accept That Wes Is Right’: The French Dispatch crew explains how it pulled off the movie’s quietly impossible long shot ’. ‘The Diamond Desk, Surveillance Shots, and 7 Other Stories About Making Severance’.

As you probably guessed, a travel feature often features a narrator who is writing about a place that the reader has an interest in.

It is the job of the writer to inform their audience of the experiences, sights and sounds that they can also experience if they ever visit this destination.

Examples: ‘ Palau’s world-first ‘good traveller’ incentive ’, ‘An icy mystery deep in Arctic Canada’.

‘How to’ features will always have their place and have become even more popular with the advent of the internet phenomenon known as ‘life hacks’. There is now a subsection of these features, where writers try out ‘how to’ instructional content and let the reader know how useful it actually is.

Interestingly, you don’t have to go far to find an instructional feature article. You are actually reading one at the moment.

Example: The article you are reading right now.

Of course, the above is just an overview of some of the types of features that exist. You shouldn’t get bogged down by the idea that some feature types interlope with others.

Feature writing is a dynamic area that is constantly evolving and so are the topics and styles associated with this type of writing.

If you have an idea for something completely different, don’t be afraid to try it.

Now we covered some of the main types, let’s take a look at the steps you should take when planning to write a feature article.

It sounds obvious, but the first step on the path to a good feature article is to have a strong idea. If you are struggling for inspiration, then it may be worth your while checking out popular feature sections within newspapers or websites.

For instance, the New York Times is renowned for its wonderful ‘Trending’ section , as is The Guardian , for its features. Of course, these sites should be used only for education and inspiration.

In an instructional feature article, online learning platform MasterClass gives a good overview of the type of research that needs to be done for this type of article.

It states: “Feature stories need more than straight facts and sensory details—they need evidence. Quotes, anecdotes, and interviews are all useful when gathering information for (a) feature story.”

The article also gives an overview of why research is important. It reads: “Hearing the viewpoints or recollections of witnesses, family members, or anyone else… can help (the article) feel more three-dimensional, allowing you to craft a more vivid and interesting story.”

Feature articles may involve creative writing, but they are still based on facts. That is why research should be a tenet of any article you produce in this area.

Shortly after starting your research, you will be posed the question of ‘what type of feature do I want to write?’.

The answer to this question may even change from when you had your initial idea.

For example, you may have decided that you want to do a lifestyle feature on the physical fitness plan of your local sports team. However, during research, you realized that there is a far more interesting interview piece on one of the athletes who turned their physical health around by joining the team.

Of course, that is a fictional scenario, but anyone who has ever worked within a newsroom knows how story ideas can evolve and change based on the reporting that’s done for them.

The next step is to consider the language you will be using while writing the article. As you become more experienced, this will be second nature to you. However, for now, below are a few tips.

When writing a feature, you should do so with your own unique style. Unlike straight news stories, you can insert your personality and use emotive language.

However, you should avoid too many adjectives and adverbs and other overused words . You should generally refer to the audience as ‘you’ too.

To learn more, check out our article about the best style guides .

As you can tell from the examples listed above, a good feature usually has a good headline/ header. If you are lucky enough to work in a newsroom with a good subeditor, then they will work with you to decide an eye-catching headline.

However, most of you will have to pick your features’ header on your own. Thus, it’s worth giving some time to consider this stage of the process.

It is handy to take a look at Matrix Education’s tips for creating a catchy headline.

They are as follows:

- Use emotive language.

- Keep it short and snappy.

- Directly address the reader.

- Use adjectives / adverbs.

- Tell readers what your content is about.

- Ask a question.

- Give an imperative.

These are, of course, only options and they all shouldn’t be utilized at once.

Another suggestion that can be added to the list is grabbing an intriguing quote from the story and using that within the header.

Your opening paragraph should draw the reader in. It is important that you can hook them here; if you can grab them at the start, they are far more likely to go deeper into the article.

Methods of doing this include the building of tension, the posing of a rhetorical question, making an outlandish statement that is proven true later in the article, or working your way back from a monumental event that the reader is already familiar with.

Whichever you use, the primary goal should be to catch the reader’s interest and to make them want to read on.

If you need help, start with writing a five-paragraph essay .

Jean-Luc Godard said that “a story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order”.

That statement can be somewhat applied to feature articles. However, don’t be afraid to take risks with your writing. Of course, it is important to share the information you need to share, but a feature article does offer far more room for creativity than the writing of a traditional news story.

8. Leave With A Bang

All the best feature writer leave a little something for the reader who reaches the end of the article. Whether that is a storming conclusion, or something that ties it all together, it is important that there is some sort of conclusion.

It gives your audience a feeling of satisfaction upon reading the article and will make this is the element that will make them look out for the articles that you will write in the future.

The above steps don’t necessarily need to be followed in the order they are written. However, if you are new to this type of writing, they should give you a good starting point as when creating feature articles.

When writing feature articles, you will find a style and a voice that suits you. This is a type of journalistic writing where you can embrace that creative side and run with it.

- What is a feature story example?

Jennifer Senior won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing for an article entitled ‘What Bobby McIlVaine Left Behind’, an article about the human aftermath of grief after 9/11. It is an excellent example of a quality feature article.

- What is the difference between a feature story and a news story?

There are several differences between a feature article and a news story.

Firstly, news articles are time-sensitive, whereas there is more flexibility when a feature can be published as it will still be of interest to the public.

Secondly, feature stories are usually more long-form than news stories, with differences in style employed in both. For instance, news writing often employs the inverted pyramid, where the most important information is at the start. Whereas, feature writing has a tendency to tease out the information throughout the article.

Lastly, the ending of a news story usually happens when all the relevant and available details are shared. On the other hand, a feature story usually ends with the writer tying up the loose-ends that exist with an overall conclusion.

Bryan Collins is the owner of Become a Writer Today. He's an author from Ireland who helps writers build authority and earn a living from their creative work. He's also a former Forbes columnist and his work has appeared in publications like Lifehacker and Fast Company.

View all posts

- APPLY ONLINE

- APPOINTMENT

- PRESS & MEDIA

- STUDENT LOGIN

- 09811014536

}}/assets/Images/paytm.jpg)

How to Write a Feature Article: A Step-by-Step Guide

Feature stories are one of the most crucial forms of writing these days, we can find feature articles and examples in many news websites, blog websites, etc. While writing a feature article a lot of things should be kept in mind as well. Feature stories are a powerful form of journalism, allowing writers to delve deeper into subjects and explore the human element behind the headlines. Whether you’re a budding journalist or an aspiring storyteller, mastering the art of feature story writing is essential for engaging your readers and conveying meaningful narratives. In this blog, you’ll find the process of writing a feature article, feature article writing tips, feature article elements, etc. The process of writing a compelling feature story, offering valuable tips, real-world examples, and a solid structure to help you craft stories that captivate and resonate with your audience.

Read Also: Top 5 Strategies for Long-Term Success in Journalism Careers

Table of Contents

Understanding the Essence of a Feature Story

Before we dive into the practical aspects, let’s clarify what a feature story is and what sets it apart from news reporting. While news articles focus on delivering facts and information concisely, feature stories are all about storytelling. They go beyond the “who, what, when, where, and why” to explore the “how” and “why” in depth. Feature stories aim to engage readers emotionally, making them care about the subject, and often, they offer a unique perspective or angle on a topic.

Tips and tricks for writing a Feature article

In the beginning, many people can find difficulty in writing a feature, but here we have especially discussed some special tips and tricks for writing a feature article. So here are some Feature article writing tips and tricks: –

Do you want free career counseling?

Ignite Your Ambitions- Seize the Opportunity for a Free Career Counseling Session.

- 30+ Years in Education

- 250+ Faculties

- 30K+ Alumni Network

- 10th in World Ranking

- 1000+ Celebrity

- 120+ Countries Students Enrolled

Read Also: How Fact Checking Is Strengthening Trust In News Reporting

1. Choose an Interesting Angle:

The first step in feature story writing is selecting a unique and compelling angle or theme for your story. Look for an aspect of the topic that hasn’t been explored widely, or find a fresh perspective that can pique readers’ curiosity.

2. Conduct Thorough Research:

Solid research is the foundation of any feature story. Dive deep into your subject matter, interview relevant sources, and gather as much information as possible. Understand your subject inside out to present a comprehensive and accurate portrayal.

3. Humanize Your Story:

Feature stories often revolve around people, their experiences, and their emotions. Humanize your narrative by introducing relatable characters and sharing their stories, struggles, and triumphs.

4. Create a Strong Lead:

Your opening paragraph, or lead, should be attention-grabbing and set the tone for the entire story. Engage your readers from the start with an anecdote, a thought-provoking question, or a vivid description.

5. Structure Your Story:

Feature stories typically follow a narrative structure with a beginning, middle, and end. The beginning introduces the topic and engages the reader, the middle explores the depth of the subject, and the end provides closure or leaves readers with something to ponder.

6. Use Descriptive Language:

Paint a vivid picture with your words. Utilize descriptive language and sensory details to transport your readers into the world you’re depicting.

7. Incorporate Quotes and Anecdotes:

Quotes from interviews and anecdotes from your research can breathe life into your story. They add authenticity and provide insights from real people.

8. Engage Emotionally:

Feature stories should evoke emotions. Whether it’s empathy, curiosity, joy, or sadness, aim to connect with your readers on a personal level.

Read Also: The Ever-Evolving World Of Journalism: Unveiling Truths and Shaping Perspectives

Examples of Feature Stories

Here we are describing some of the feature articles examples which are as follows:-

“Finding Beauty Amidst Chaos: The Life of a Street Artist”

This feature story delves into the world of a street artist who uses urban decay as his canvas, turning neglected spaces into works of art. It explores his journey, motivations, and the impact of his art on the community.

“The Healing Power of Music: A Veteran’s Journey to Recovery”

This story follows a military veteran battling post-traumatic stress disorder and how his passion for music became a lifeline for healing. It intertwines personal anecdotes, interviews, and the therapeutic role of music.

“Wildlife Conservation Heroes: Rescuing Endangered Species, One Baby Animal at a Time”

In this feature story, readers are introduced to a group of dedicated individuals working tirelessly to rescue and rehabilitate endangered baby animals. It showcases their passion, challenges, and heartwarming success stories.

What should be the feature a Feature article structure?

Read Also: What is The Difference Between A Journalist and A Reporter?

Structure of a Feature Story

A well-structured feature story typically follows this format:

Headline: A catchy and concise title that captures the essence of the story. This is always written at the top of the story.

Lead: A captivating opening paragraph that hooks the reader. The first 3 sentences of any story that explains 5sW & 1H are known as lead.

Introduction : Provides context and introduces the subject. Lead is also a part of the introduction itself.

Body : The main narrative section that explores the topic in depth, including interviews, anecdotes, and background information.

Conclusion: Wraps up the story, offers insights, or leaves the reader with something to ponder.

Additional Information: This may include additional resources, author information, or references.

Read Also: Benefits and Jobs After a MAJMC Degree

Writing a feature article is a blend of journalistic skills and storytelling artistry. By choosing a compelling angle, conducting thorough research, and structuring your story effectively, you can create feature stories that captivate and resonate with your readers. AAFT also provides many courses related to journalism and mass communication which grooms a person to write new articles, and news and learn new skills as well. Remember that practice is key to honing your feature story writing skills, so don’t be discouraged if it takes time to perfect your craft. With dedication and creativity, you’ll be able to craft feature stories that leave a lasting impact on your audience.

What are the characteristics of a good feature article?

A good feature article is well-written, engaging, and informative. It should tell a story that is interesting to the reader and that sheds light on an important issue.

Why is it important to write feature articles?

Feature articles can inform and entertain readers. They can also help to shed light on important issues and to promote understanding and empathy.

What are the challenges of writing a feature article?

The challenges of writing a feature article can vary depending on the topic and the audience. However, some common challenges include finding a good angle for the story, gathering accurate information, and writing in a clear and concise style.

Aaditya Kanchan is a skilled Content Writer and Digital Marketer with experience of 5+ years and a focus on diverse subjects and content like Journalism, Digital Marketing, Law and sports etc. He also has a special interest in photography, videography, and retention marketing. Aaditya writes in simple language where complex information can be delivered to the audience in a creative way.

- Feature Article Writing Tips

- How to Write a Feature Article

- Step-by-Step Guide

- Write a Feature Article

Related Articles

Is Citizen Journalism the Future of News?

Adapting to a Changing Media Landscape 2024

The Impact of Commercial Radio & Scope of Radio Industry in India

The Different Types of News in Journalism: What You Need to Know

Enquire now.

- Advertising, PR & Events

- Animation & Multimedia

- Data Science

- Digital Marketing

- Fashion & Design

- Health and Wellness

- Hospitality and Tourism

- Industry Visit

- Infrastructure

- Mass Communication

- Performing Arts

- Photography

- Student Speak

- 5 Reasons Why Our Fashion Design Course Will Set You Apart May 10, 2024

- Nutrition & Dietetics Course After 12th: Courses Details, Eligibility, and Fee 2024 May 9, 2024

- Fashion Design Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fee, and Eligibility 2024 May 4, 2024

- Film Making Courses After 12th: Course Details, Fees, and Eligibility 2024 May 3, 2024

- The Wellness Wave: Trends in Nutrition and Dietetics Training 2024 April 27, 2024

- Sustainable and Stylish: Incorporating Eco-Friendly Practices in Interior Design Courses April 25, 2024

- Why a Fine Arts Degree is More Than Just Painting Pictures April 24, 2024

- Beyond the Lines: Exploring Creativity and Expression in Fine Arts April 24, 2024

- How Music Classes Can Help You Achieve Your Musical Goals April 23, 2024

- How Artificial Intelligence is Reshaping Animation Production? April 22, 2024

}}/assets/Images/about-us/whatsaap-img-1.jpg)

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Article Writing

How to Write a Feature Article

Last Updated: March 11, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Mary Erickson, PhD . Mary Erickson is a Visiting Assistant Professor at Western Washington University. Mary received her PhD in Communication and Society from the University of Oregon in 2011. She is a member of the Modern Language Association, the National Communication Association, and the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article has 41 testimonials from our readers, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 1,461,226 times.

Writing a feature article involves using creativity and research to give a detailed and interesting take on a subject. These types of articles are different from typical news stories in that they often are written in a different style and give much more details and description rather than only stating objective facts. This gives the reader a chance to more fully understand some interesting part of the article's subject. While writing a feature article takes lots of planning, research, and work, doing it well is a great way to creatively write about a topic you are passionate about and is a perfect chance to explore different ways to write.

Choosing a Topic

- Human Interest : Many feature stories focus on an issue as it impacts people. They often focus on one person or a group of people.

- Profile : This feature type focuses on a specific individual’s character or lifestyle. This type is intended to help the reader feel like they’ve gotten a window into someone’s life. Often, these features are written about celebrities or other public figures.

- Instructional : How-to feature articles teach readers how to do something. Oftentimes, the writer will write about their own journey to learn a task, such as how to make a wedding cake.

- Historical : Features that honor historical events or developments are quite common. They are also useful in juxtaposing the past and the present, helping to root the reader in a shared history.

- Seasonal : Some features are perfect for writing about in certain times of year, such as the beginning of summer vacation or at the winter holidays.

- Behind the Scenes : These features give readers insight into an unusual process, issue or event. It can introduce them to something that is typically not open to the public or publicized.

Interviewing Subjects

- Schedule about 30-45 minutes with this person. Be respectful of their time and don’t take up their whole day. Be sure to confirm the date and time a couple of days ahead of the scheduled interview to make sure the time still works for the interviewee.

- If your interviewee needs to reschedule, be flexible. Remember, they are being generous with their time and allowing you to talk with them, so be generous with your responses as well. Never make an interviewee feel guilty about needing to reschedule.

- If you want to observe them doing a job, ask if they can bring you to their workplace. Asking if your interviewee will teach you a short lesson about what they do can also be excellent, as it will give you some knowledge of the experience to use when you write.

- Be sure to ask your interviewee if it’s okay to audio-record the interview. If you plan to use the audio for any purpose other than for your own purposes writing up the article (such as a podcast that might accompany the feature article), you must tell them and get their consent.

- Don't pressure the interviewee if they decline audio recording.

- Another good option is a question that begins Tell me about a time when.... This allows the interviewee to tell you the story that's important to them, and can often produce rich information for your article.

Preparing to Write the Article

- Start by describing a dramatic moment and then uncover the history that led up to that moment.

- Use a story-within-a-story format, which relies on a narrator to tell the story of someone else.

- Start the story with an ordinary moment and trace how the story became unusual.

- Check with your editor to see how long they would like your article to be.

- Consider what you absolutely must have in the story and what can be cut. If you are writing a 500-word article, for example, you will likely need to be very selective about what you include, whereas you have a lot more space to write in a 2,500 word article.

Writing the Article

- Start with an interesting fact, a quote, or an anecdote for a good hook.

- Your opening paragraph should only be about 2-3 sentences.

- Be flexible, however. Sometimes when you write, the flow makes sense in a way that is different from your outline. Be ready to change the direction of your piece if it seems to read better that way.

Finalizing the Article

- You can choose to incorporate or not incorporate their suggestions.

- Consult "The Associated Press Stylebook" for style guidelines, such as how to format numbers, dates, street names, and so on. [7] X Research source

- If you want to convey slightly more information, write a sub-headline, which is a secondary sentence that builds on the headline.

How Do You Come Up With an Interesting Angle For an Article?

Sample Feature Article

Community Q&A

- Ask to see a proof of your article before it gets published. This is a chance for you to give one final review of the article and double-check details for accuracy. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Be sure to represent your subjects fairly and accurately. Feature articles can be problematic if they are telling only one side of a story. If your interviewee makes claims against a person or company, make sure you talk with that person or company. If you print claims against someone, even if it’s your interviewee, you might risk being sued for defamation. [9] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://morrisjournalismacademy.com/how-to-write-a-feature-article/

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/learning/students/writing/voices.html

- ↑ http://careers.bmj.com/careers/advice/view-article.html?id=20007483

- ↑ http://faculty.washington.edu/heagerty/Courses/b572/public/StrunkWhite.pdf

- ↑ https://www.apstylebook.com/

- ↑ http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/166662

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/libel-vs-slander-different-types-defamation.html

About This Article

To write a feature article, start with a 2-3 sentence paragraph that draws your reader into the story. The second paragraph needs to explain why the story is important so the reader keeps reading, and the rest of the piece needs to follow your outline so you can make sure everything flows together how you intended. Try to avoid excessive quotes, complex language, and opinion, and instead focus on appealing to the reader’s senses so they can immerse themselves in the story. Read on for advice from our Communications reviewer on how to conduct an interview! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Kiovani Shepard

Nov 8, 2016

Did this article help you?

Sky Lannister

Apr 28, 2017

Emily Lockset

Jun 26, 2017

Christian Villanueva

May 30, 2018

Richelle Mendoza

Aug 26, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

7 examples of engaging feature stories

Kimberlee Meier — Contributing Writer

There are two dominant trends in content on the web today.

The first is that content is getting shorter. With the rise of TikTok and the ongoing importance of other social media platforms, brands need to be adept at producing shortform content.

But the second dominant trend — forgive the contradiction — is that content outside of social media is actually getting longer. As we explain in our guide to longform content , media and marketing teams are increasingly investing in longer, professionally produced content to capture and keep their reader's attention.

The main type of longform content they are investing in is the feature article or feature story. Following the lead of major news publications, these teams are creating truly engaging and immersive multimedia content.

Take, for example, Los fogones de la Kitchen . This illustrated news story from El Periódico covers an illegal operation to spy on a Spanish politician. With animations triggered by the scroll of the reader, it is an interactive and powerful example of modern feature storytelling.

What do the BBC, Tripadvisor, and Penguin have in common? They craft stunning, interactive web content with Shorthand. And so can you! Publish your first story for free — no code or web design skills required. Sign up now.

In this guide, we're going to run through 7 examples of feature stories to inspire your own content strategy. These examples are informative, entertaining, and visually appealing—just what a brand needs to keep people’s attention.

We'll also cover what goes into creating a great feature story, and how to learn from those who are doing them well.

Ready to learn how to create captivating feature stories of your own? Let's get started.

What is a feature story?

A feature story is a piece of longform non-fiction content that covers a single topic in detail. Examples of feature stories include news features, in-depth profiles, human interest stories, science communication , data storytelling , and more.

Feature stories are a common type of content for news organisations, particularly those who invest in longform journalism .

Increasingly, brands are also investing in producing their own high-quality feature stories. One example comes from analytics company RELX, who published a powerful overview of the purpose behind their Eyewitness to Atrocities app.

How are feature stories changing?

A decade ago, most feature stories on the web were visually uninteresting. Usually, they would be digital versions of print articles, with the same images and copy.

With recent improvements in internet speed and browsers — coupled with the rise of more advanced content creation platforms — we're seeing a dramatic increase in visually immersive multimedia feature articles.

These stories use a combination of high-resolution, full-bleed images, video, illustrations, and scrollytelling to sustain the attention of digital readers. Often, these stories are created with digital storytelling platforms , which are empowering feature writers to create stunning interactive content without writing a line of code.

Now, let's dive into our examples👇

7 examples of stunning feature stories

1 Arab News

When Arab News decided to showcase Saudi Arabia's UNESCO's World Heritage sites, a standard longform article wasn’t going to cut it.

So, the news agency decided to tell it as a feature story powered by digital elements like maps, video, historical pictures, and illustrations.

Each of the five UNESCO sites located in Saudi Arabia is given its own section. This room allowed Arab News the room to explain, in detail, the history of each site and what it looks like today.

Although the piece is long, it does give the UNESCO sites the space and in-depth reporting to turn this into a stunning example of a feature story.

In the 1930s, America's Federal Government enacted redlining policies that segregated Black and white citizens with homeownership.

Despite the Supreme Court ruling in 1948 that racial bias in deed restrictions was illegal, Detroit remains one of the most segregated cities in the country. To tell this important story, NBC News created an immersive and interactive feature story out of images and video to showcase the issue of segregation in modern Detroit.

The mix of data, visuals, video, and interviews with citizens who grew up in segregated neighborhoods make this feature story a compelling read.

3 Pioneers Post

In the race to combat climate change, the citizens of Gambia—one of Africa's smallest countries—realised that the clock is ticking.

So, the locals and family farmers living on the north bank of the Gambia river took matters into their own hands and created plans to reforest an 8,000km stretch of land.

Not only does this Pioneers Post feature story do a fantastic job at highlighting the plight of the villagers and their project to revive the environment, but it also explains the impact of global warming on their area with maps and visuals.

4 Hoover Institute

As a society, we are fascinated by each other's cultures. And more often than not, governments are involved in telling stories about what those cultures look like.

Women in Chinese Propaganda by the Hoover Institute takes a deeper look at how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) depicted women in the early days of its regime. Using a mix of illustrations, history, and interactive features, the reader is plunged into the story the regime told the world about how its women lived in the 1950s.

The feature story also talks about the ties the propaganda has to cultural products, like plays and operas, as well as how marriage was depicted in the early days of the CCP.

Join the BBC, Unicef, and Penguin. Publish stunning, interactive web content with Shorthand. Publish your first story for free — no code or web design skills required. Get started.

5 BBC

When an apartment building in La Villeneuve, France, caught fire in 2020, two children were trapped in the inferno.

As villagers watched on, the scene grew desperate—until a group of local citizens came up with a solution: the children would jump, and the citizens would catch them.

The BBC detailed the events of that day and accounts of the hero citizens who saved the children's lives in their interactive feature story, The Catch .

Using a mix of illustrations, photographs, and interviews from people involved in the life-saving rescue, the feature story succeeds in putting the reader inside the events that unfolded.

The story paints an uncomfortable truth: just ten days after the French President called for some foreign-born residents to be stripped of their citizenship—immigrants were rescuing children.

6 WaterAid

Another feature story focusing on climate change, WaterAid tells the story of people facing harsh environmental conditions in Malawi, Africa.

The story digs deep—using full-screen photographs, statistics, and quotes from climate change scientists about the changing environment for the people living there. WaterAid is using this piece to encourage people to fight climate change. So, it's fitting that the piece ends with a simple ask: Join #OurClimateFight .

7 Sky News

The final feature story on our list is Sky News' celebration of WNBA's 25th season.

The story, From ‘We Got Next’ to ‘Next Steps' , has a tonne of embedded items to keep the reader interested. Sky News uses a mix of embedded Tweets, photographs, and videos to showcase WNBA's history from those who have been part of it.

And like the Water Aid feature story, Sky News wraps its piece up by adding a call-to-action, encouraging readers to follow the WNBA's progress on its YouTube and cable television channels.

Ready to start creating your own amazing feature stories?

Content creators and news agencies have stepped up their storytelling game and are going above and beyond to capture (and keep) their audience's attention.

Slapping a 3000-word story into WordPress isn't enough to keep your reader engaged anymore (no matter how interesting the topic is.) Thanks to the rise of social media platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter, users now expect feature stories to be more engaging and capture their imagination.

The good news is that creating these stories no longer means you have to learn how to code or hire an (expensive) developer. Content creators can build exciting, in-depth feature stories that embed elements like images, data illustrations, videos, and social media feeds using a tool like Shorthand.

So, what are you waiting for—are you ready to start creating stories that will take your readers on a journey?

Kimberlee Meier is a B2B/SaaS Content Writer who also helps start-ups fuel their growth through quality, evergreen content.

Publish your first story free with Shorthand

Craft sumptuous content at speed. No code required.

Anthony Cockerill

| Writing | The written word | Teaching English |

The indispensable guide to what makes a great feature story

The feature story is a potent and vital form of literary non-fiction. here, anthony cockerill charts its evolution through the years..

Of all the different ways to tell stories, the feature article is one of the most compelling, especially when it’s in the right hands. It’s a mainstay of contemporary journalism: a set-piece at the core of a periodical amidst the recurring content, opinion columns and advertisements. A good feature story is authentic, without artifice or illusion, even though it can be as immersive as any great novel.

The feature article has more in common with the essay than traditional reportage, but unlike most essays, it is more akin to narrative. It makes productive use of story-telling strategies usually found in fiction. It is grounded in places and people. It offers an in-depth exploration. It’s a useful vehicle for the investigative journalist, but not all features are necessarily investigative in nature — a feature story might profile a noted person, or it might find a particular angle which illuminates a bigger issue. Like all great stories, a great feature exploits the reader’s pleasure in delayed gratification, as they engage willingly in the pleasure of being the passive participant of the narrative.

Antecedents

The essay is perhaps the earliest antecedent for the feature article, but the essay resists easy definition. Most people associate the form with the academic assignment — a means of assessing someone’s understanding of their studies — or perhaps the scholarly essay, published in disciplinary journals. But an essay — exploratory in both purpose and tone — can be critical, persuasive or personal in scope and all of these have influenced the evolution of the feature article.

When we read accomplished essayists such as Michel de Montagine, George Orwell and Clive James, we’re aware of a strong sense of subjectivity and enquiry. The essay writing process goes hand in hand with the process of developing thinking, which surely reflects the emergence of the form — the essais — as a way ascertaining and articulating opinion in an age when editing and redrafting was more difficult.

If the essay was a literary forebear, the advent of printing took the form to the masses. Printing by mechanical, moveable type spread knowledge and ideas in forms such as the tract, the pamphlet and in time, the newspaper and increased the franchise of literacy throughout Europe.

The daily newspaper is the taproot of modern journalism. Dailies mainly date to the eighteen-thirties, the decade in which the word ‘journalism’ was coined, meaning daily reporting, the jour in journalism. Jill Lepour, ‘Does Journalism Have A Future?’, The New Yorker

The Daily Courant, edited by Elizabeth Mallet, was Britain’s first daily newspaper, first published in 1702. Mallet claimed to provide only facts, to let the reader make up their own minds about events, demanding her authors ‘…relate only matter of fact; supposing other people to have sense enough to make reflections for themselves.’ This approach characterised news reportage throughout the 17th century, when contributions to newspapers were largely supplied by correspondents.

For the 18th century, it is possible to speak of a ‘literary’ journalism… the news was (no longer) at the centre of their activity, but rather its incorporation into larger narratives or extensive arguments. Jürgen Wilk e, Professor of Journalism, Johannes Gutenberg University

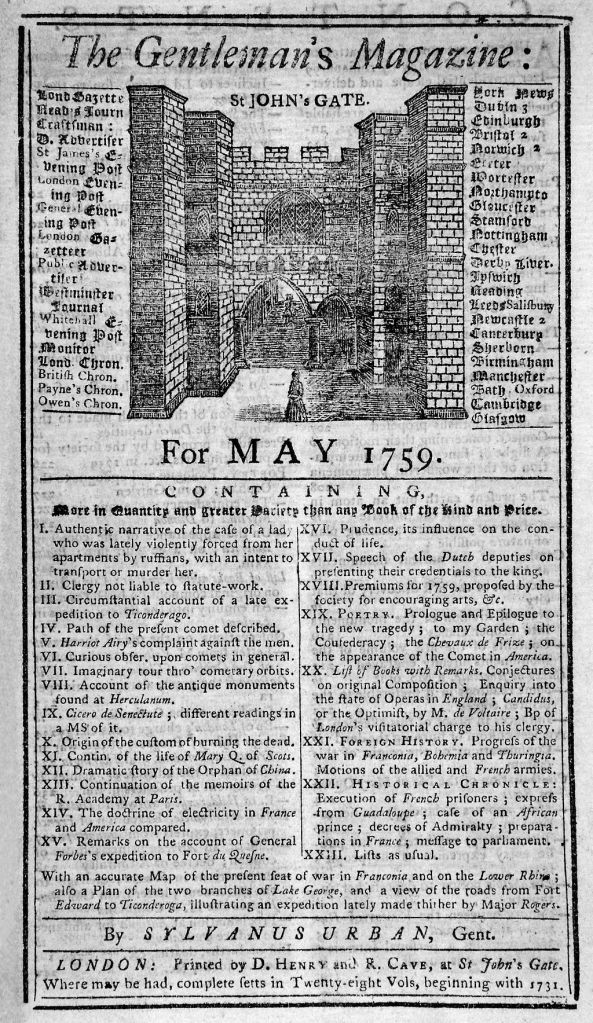

Jürgen Wilke, Professor of Journalism at Johannes Gutenberg University, has argued that the emergence of opinion journalism — the point where essay meets newspaper article — occurred in the 18th century. Newspapers became what he calls ‘organs of public opinion’. Wilke attributes this change to the failure of the Commons to renew the Printing Act in 1695, which had a direct impact on the freedom of the press. At this time ‘…the printer was responsible for the news… whereas the authors themselves oversaw the essay section and other sundry contributions. They… could also publish critical articles and voice their own opinion.’ As well as the daily newspaper, the period saw the gestation of the magazine — a monthly digest of news, review and commentary for the educated public. Although by no means the first, The Gentleman’s Magazine , first published in London in 1731, was the first periodical to use the enduring generic term. The ‘magazine’ evoked the idea of the armoury: a storehouse of powerful ideas and knowledge.

‘Many authors in the 18th century tried to gain a foothold in the booming sector of journal publishing,’ says Professor Wilke, ‘often writ[ing] other types of journalistic articles, for instance, essays and literary contributions to weeklies, which described themselves in their titles as journals.’

In the United Kingdom, compulsory education and the expansion of the electoral franchise in the 19th century led to growing literacy amongst the population. The repeal of the stamp tax in 1855 and the advent of the rotary press, combined with the availability of cheaper paper, facilitated a huge growth in the popularity and reach of both newspapers and magazines. Typical of the newly popular mass circulation magazine was Tit-Bits , published by George Newness, a miscellany of material gathered from a variety of sources and short fiction. The 19th century was also the age when scholarly journals expanded and the critical review emerged, in forms such as The Edinburgh Review and Quarterly Review . Charles Lamb’s Essays first appeared in The London Magazine , which was first published in 1820.

The content of periodicals at this time was essentially a combination of essay and exposition. A scholarly tone dominated and there was little sense of narrative. The editorial voice of The Spectator , founded in 1828, was expressed using the third-person personal pronoun ‘we’, implying an authority and collective understanding in line with the Enlightenment values of the time. This was evident as late as 1903: ‘We note with no little satisfaction that the feeling against Mr. Chamberlain’s proposals for taxing the food of the people is increasing every day.’ But by the following decade, the third-person pronoun — the editorial ‘we’ — had fallen out of style.

Casting an approving eye across the Atlantic in 1886, The Spector noted that Harper’s Monthly Magazine , established in 1850, ‘continue[d] to be worthy of [its] high reputation. Mr. Blackmore’s new story, ‘Springhaven,’ which… depicts the England that successfully resisted the first Napoleon, promises to be as good as anything that has recently come from the same pen. Under the title of ‘Their Pilgrimage,’ Mr. Dudley Warner gives a very lively account, slightly tinged, perhaps, with caricature, of American summer jauntings. ‘The New York Exchange’… tak[es] us behind the scenes of commercial life on the other side of the Atlantic for which this magazine is noted.’

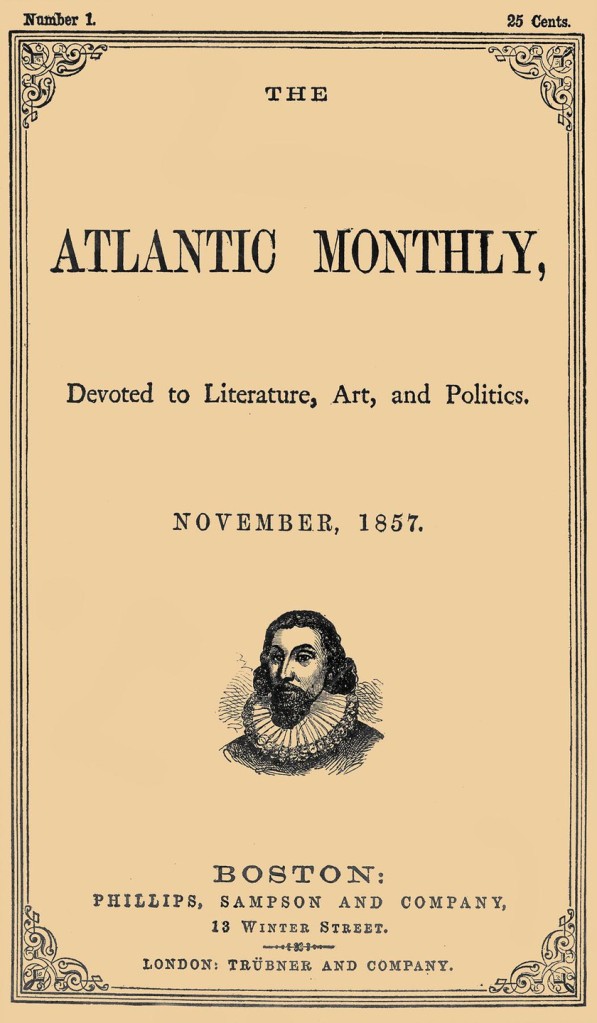

First edited by James Russell Lowell, The Atlantic Monthly was founded in 1857. ‘Our Birds, And Their Ways’, published during that inaugural year, gives an interesting account of the habits of birds native to America. ‘Among our summer birds,’ begins the article, ‘the vast majority are but transient visitors, born and bred far to the northward and returning thither every year.’ The article occasionally makes use of the first-person style (‘I have seen crows in the neighbourhood of Boston every week of the year…’) and on occasion, direct speech (‘My friend the ornithologist said to me last winter, “You will see that they will be off as soon as the ground is well covered in snow…”‘) But these stylistic choices are rare. There is very little to discern by way of the influence of fiction.

Investigative journalism and social commentary

If the rule of the 19th century periodical feature was scholarly exposition, one notable exception was Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens’ own journalism is notable for blending, stylistically at least, fiction and non-fiction. The critic Michael Dirda has written that while ‘there is a good deal of fancy in Dickens’ reportage, the second half of Sketches by ‘Boz’ consists of what are, in fact, out-and-out short stories.’ In these vignettes, Dickens created a particularly literary form of journalism which gave him an opportunity to craft the characteristic social commentary which was, of course, was similarly conspicuous in his fiction. This wasn’t to everyone’s taste. In 1853, The Spectator published a scathing review of Dickens’ Bleak House , accusing him of ‘amusing the idle hours of the greatest number of readers; not, we may hope, without improvement to their hearts, but certainly without profoundly affecting their intellects or deeply stirring their emotions.’ This scathing indictment perhaps illustrates the division between the intellectualism of the established society periodicals and the nascent ‘populism’ emerging at the time, pioneered in British journalism by William Thomas Stead.

As the editor of The Pall Mall Gazette , editor and social reformer Stead paved the way for the investigative journalism which remains, to some degree, part of the feature article as we know it: eye-catching headlines, subheadings and visuals. Even more importantly, Stead influenced the tropes of this journalism, pioneering the newspaper interview and the subjective presence of the writer within the text, such as in his reportage of the famous Eliza Armstrong case, an important example of a journalist creating news to write about, rather than merely reporting events. In the USA, the sensationalism of Stead was paralleled in the journalism published by William Randolph Hearst, owner of the New York Journal , and Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World . These developments prompted a visceral response from some critics, notably Matthew Arnold, who pejoratively called Stead’s output ‘New Journalism’. This was more than simple grumbling: the emergence of the popular press instigated a debate about the value of journalistic objectivity.

Adolph Ochs, who bought the New York Times in 1896, must have been a man from the same school of thought as Matthew Arnold: he banned comic strips and gossip columns from the newspaper, and in doing so, focused the publication’s efforts on objective journalism, raising the profile of the newspaper and establishing its international reputation. That same year, The New York Times Magazine was first printed under the auspices of Ochs, establishing the magazine as an outlet for photo-journalism and features.

People and their stories

At a time when Freud was developing his theories of the unconscious and painters like Picasso were experimenting with Cubism, journalists were also developing a greater recognition of human subjectivity. Walter Dean, American Press Institute

Despite inroads into a more literary style of journalism made by the likes of Dickens, as a whole, literary influences in the form continued to feel restrained. The tone of ‘Golf’, a feature in The Atlantic Monthly in 1902, feels predominantly like an essay rather than a story. Although there is a strong sense of authorship and a slight sense of irony (‘Empire, trusts, and golf — these are the new things in American life…’) and although structured like an essay that ranges around its subject, narrative is largely absent.

Writing in Nordicom Review on the featurisation of journalism, Steen Steensen, Professor of Journalism at Oslo Metropolitan University, has argued that the feature article as we understand it in its modern form is a creation of the 20th century. It certainly seems to be the early years of the 1900s in which we can begin to discern an approach to the feature article that emphasises people and their experiences. The Atlantic Monthly printed a polemical essay about animal experimentation from John Dewey in September 1926. ‘In Jerusalem a great Jewish university is being slowly developed,’ wrote Henry W Nevison in the same publication in May 1927. There is a sense that the stories and the pursuits of people were beginning to take centre stage.

National Geographic Magazine was a scholarly journal until 1905, when it became known for what it continues to do well — extensive pictorial content and photojournalism — under the editorial control of Gilbert H Grosvenor. In 1905, the magazine published a feature article called ‘The Purple Veil’, subtitled ‘A Romance of the Sea.’ Clearly, there are the beginnings of a narrative approach. The ‘purple veil’ of the title, as the article later reveals, is the egg mass of Lophius piscatorius , or the goose-fish. ‘Off the New England coast,’ begins the article, ‘a curious object is often found floating on the water, somewhat resembling a lady’s veil of gigantic size and of a violet or purple colour. The fishermen allude to it generally as “the purple veil,” and many have been the speculations concerning its nature and origin.’ There is a pleasing sense of immersion, a sort of ‘cold open’ that is unabashedly designed to hook the reader.

In ‘The Date Gardens of the Jerid’, written by Thomas H Kearney and published in National Geographic Magazine in 1910, the author begins with the immersive, sense of place opening that the magazine is known for: ‘With its feet in the water and its head in the fire, as the Arab proverb has it, the date palm is at home in the vast deserts that stretch from Morocco to the borders of India.’ After this initial scene setting, the author segues into exposition, telling us: ‘Some years ago, I visited these oases in order to obtain palms for the date orchards which the National Department of Agriculture has established in Arizona and in the Colorado Desert of California.’ This juxtaposition of vibrant image and elucidation continues to be a key structural technique in feature stories today.

Brazenly literary in style, lyrically crafted and undoubtedly novelistic, Florence Craig Albrecht begins ‘Channel Ports – And Some Others’ in 1915 by describing a maritime voyage:

‘The sturdy old vessel is coming into port after an eventless voyage. Seven days of ceaseless plowing through a shimmering sea, under a great round dome, now radiant light, now dusky velvet, star-sprinkled. The Scillys have floated by, foam-washed, mist wrapped, fairly islands in a magic world all cloud and water.’ ‘Channel Ports – And Some Others’, Florence Craig Albrecht

Albrecht has embraced a literary narrative and established a strong sense of place. There is also a clear omniscient point-of-view at work here that evokes the establishing shot of a film in style. This embrace of immediacy in the story-telling — and of movement — feels very much inspired by moving image.

Morris Markey wrote ‘Gangs’ in The Atlantic Monthly in March 1928. Again, the sense of people and place is palpable:

‘On a pleasant evening, not many weeks ago,’ writes Markey in his opening paragraph, ‘a young man bearing the rather picturesque name of Little Augie was standing with a friend on the street corner in New York’s lower East Side. The friend was facing toward the curb, and suddenly, he gave a cry of warning. Little Augie swung about in time to see an automobile charge down upon him.’ ‘Gangs’, Morris Markey

From this evocative opening scene, Markey goes on to explore the backstory; to fill in some of the detail behind Little Augie’s death. The writing is composed of scenes and exposition which are woven together. Furthermore, these scenes and expository components are structured together in longer narrative sequences, divided by Roman numerals. Clearly, there is an emerging sense of the fictional form and its associated stylistics exerting a strong influence in the composition of the text.

Just as Dickens’ journalism had been characterised by aspects of narrative befitting a novelist, in the early decades of the 20th Century, Ernest Hemingway also began his writing career in the newsroom. Hemingway’s experiences writing journalism famously influenced his fiction. Taking the nod from the style guide at the Kansas City Star , where he worked as a reporter after leaving high school, his fiction became known for its objective narrative perspective and lucid sentences. Conversely, Hemingway’s reportage had always been literary. It had sketches, descriptions, characters and a sense of narrative which set the inverted pyramid of the news story the right way up. In his article ‘At the End of the Ambulance Run’, a newspaper article for the Kansas City Star from 1918, Hemingway begins his copy with the ominous action of a short story:

The night ambulance attendants shuffled down the long, dark corridors at the General Hospital with an inert burden on the stretcher. They turned in at the receiving ward and lifted the unconscious man to the operating table. His hands were calloused and he was unkempt and ragged, a victim of a street brawl near the city market. No one knew who he was, but a receipt, bearing the name of George Anderson, for $10 paid on a home out in a little Nebraska town served to identify him. ‘At the End of the Ambulance Run’, Ernest Hemingway

This is an approach to storytelling usually found in fiction, where the writer lures the reader, leaves them to work out what is or isn’t fundamentally crucial, then builds to a climax. It is essentially the structural and stylistic opposite of the classic inverted pyramid, which condenses news, summarises and foregrounds the most important part of the story.

In 1933, by this time established as a writer of fiction, Hemingway was made an offer he couldn’t refuse by Arnold Gingrich, who had founded Esquire that same year. ‘[He sent Hemingway] a blue sports shirt and a leather jacket, promising to pay him $250 each for articles about marlin-fishing in Cuba, lion-shooting in Tanganyika, bullfighting in Spain, and other manly subjects,’ said Carlos Baker, writing in The New York Times in 1967.

Hemingway has been seen as a profound influence on what was to be called ‘New Journalism’, and although he was undoubtedly a totemic figure, something was happening that was bigger than one person: an undercurrent of fictional stylistics gathering strength in literary journalism, the stylistics of which itself was influenced by cinema, as is evident in Stewart H Holbrook’s ‘Life of a Pullman Porter’ , published in Esquire in 1939:

One October evening in 1937 a stunning blonde of about thirty took a Pullman compartment on a Great Northern train leaving Portland, Oregon for Seattle. She was a tall, graceful woman, modishly dressed in dark blue, right up to her earrings, and the porter who was on her car still thinks she was the handsomest woman he has ever seen. An hour or so later, as the train was leaving Longview, Washington, the lady rang for the porter and handed him a letter in a pale blue envelope. “I want you to be sure,” she said with emphasis, “to mail this at Aberdeen and nowhere else.” She gave him a quarter Stewart H Holbrook, ‘Life of a Pullman Porter’

Alongside feature journalism, in the 1930s Esquire ran short-stories in abundance, as well as ‘semi-fiction’ – an interesting idea that involved real stories, fictionalised for publication. The influence of moving image in writing in this period can be felt palpably. The introduction to Laura Marcus’s essay, ‘Cinema and Modernism’, notes that modernism was ‘concerned with everyday life, perception, time and the kaleidoscopic and fractured experience of urban space. Cinema, with its techniques of close-up, panning, flashbacks and montage played a major role in shaping experimental works.’ As authors of fiction embraced the possibilities of the new medium, their stylistic influences were felt keenly in the work of feature journalists of the era.

‘Movies were already by then a part of the culture… motion was a part of the new vocabulary… for the first time in conventional reporting people began to move. They had a journalistic existence on either side of the event,’ wrote Michael J Arlen in The Atlantic Monthly in 1972. It is impossible to overestimate the influence of the cinema on literary non-fiction, just as the cinema profoundly influenced Modernist fiction during those years.

The influence of ‘New Journalism’

‘ Joe Louis at Fifty’ wasn’t like a magazine article at all. It was like a short story. It began with a scene, an intimate confrontation between Louis and his third wife. Tom Wolfe, Bulletin of the American Society Newspaper Editors , 1970

Matthew Arnold had disparagingly used the phrase ‘New Journalism’ to describe the evolving journalism of the 19th Century that was characterised by a different more sensational discourse and subject matter. In the 1960s, the American journalist Tom Wolfe used the appellation to describe his perception of a shift in the style and framing of the journalism of a cluster of writers in the period who would work in a much more literary style, espousing ‘truth’ over ‘facts’. Unlike Arnold, however, Wolfe certainly wasn’t being disparaging. In fact, there was an element of braggadocio at play. ‘New Journalism’ in Wolfe’s opinion was revolutionary, and Wolfe was one of its biggest proponents.

‘Wolfe wrote that his first acquaintance with a new style of reporting came in a 1962 Esquire article about Joe Louis by Gay Talese,’ wrote James E Murphy in The New Journalism: A Critical Perspective . For Wolfe, Talese was the first to apply fiction techniques to his reporting. But Dickens had done so, as had Hemingway and many others. Experimenting with personal narrative and the blurring of fact and fiction was hardly new. If we were to take Tom Wolfe to task for over-egging the contribution of the New Journalists, we wouldn’t be the first. To argue that New Journalism isn’t exactly new is what Michael J Arlen has called ‘a favourite put down’. In The Atlantic in 1972, he argued that ‘there’s been a vein of personal journalism in English and American writing for a very long time.’

I wonder if what happened wasn’t more like this… that despite the periodic appearance of an Addison, or Defoe, or Twain, standard newspaper journalism remained a considerably restricted branch of writing, both in England and America, well into the nineteen twenties… then, after the First World War, especially the literary resurgence in the nineteen twenties — the writers’ world of Paris, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc. — into the relatively straitlaced, rectilinear, dutiful world of conventional journalism appeared an assortment of young men who wanted to do it differently.… Michael J Arlen, ‘Notes on the New Journalism’, The Atlantic Monthly , May 1972

Once Tom Wolfe graduated, argues Arlen, ‘burdened like the rest of his generation with the obligation to write a novel’, he made an important discovery: ‘the time of the novel was past… [a] fairly profound change was already taking place in the nation’s reading habits… most magazines, which had been preponderantly devoted to fiction, were now increasingly devoted to nonfiction.’

Gay Talese’s article, ‘Frank Sinatra Has A Cold’, published in Esquire in April 1966, is, quite rightfully, a staple of journalism students’ reading lists. Denied the opportunity to talk to Sinatra, Esquire editor Harold T. P. Hayes nevertheless kept Talese on the job. Talese ‘bounc[ed] from hope to despair to paranoia and back as he work[ed] furiously to deliver the goods by shadowing the notoriously controlling Sinatra and talking to everyone who might be able to shed light on the entertainer without setting off any alarms,’ wrote Frank Digiacomo in Vanity Fair in 2006. The distance between Talese and Sinatra became the story itself, and offered Talese an angle on Sinatra’s volatile temper and fragile ego. Scenes from Talese’s time observing Sinatra are adroitly rendered:

Frank Sinatra, leaning against the stool, sniffling a bit from his cold, could not take his eyes off the Game Warden boots. Once, after gazing at them for a few moments, he turned away; but now he was focused on them again. The owner of the boots, who was just standing in them watching the pool game, was named Harlan Ellison, a writer who had just completed work on a screenplay, The Oscar. Finally Sinatra could not contain himself. ‘Hey,’ he yelled in his slightly harsh voice that still had a soft, sharp edge. ‘Those Italian boots?’ ‘No,’ Ellison said. ‘Spanish?’ ‘No.’ ‘Are they English boots?’ ‘Look, I donno, man,’ Ellison shot back, frowning at Sinatra, then turning away again. Gay Talese, ‘Frank Sinatra Has a Cold’

Stylistics of contemporary feature stories

…feature journalism is best understood as a family of genres that has traditionally shared a set of discourses: a literary discourse, a discourse of intimacy and a discourse of adventure. Steen Steensen, Professor of Journalism, Oslo Metropolitan University

The ubiquity of the overtly literary feature article and the associated stylistic choices has waned since the New Journalists’ heyday. Today’s feature stories feel less self-consciously ‘fictional’ than some of those New Journalism classics. They are lighter on direct speech and tend toward more reported speech. Dialogue tags are usually in present tense, which conveys immediacy but which loses some of the fictional notes that resonate soundly in Gay Talese’s writing. Despite this, the methods of story-telling associated with New Journalism continues to exert a powerful influence on the feature story, especially in terms of narrative structure and style.

The scene is at the heart of the feature story, and these scenes are clustered into sequences, a legacy of the influence of cinema. We can see the legacy of this in the discourse of contemporary feature writing: the narrative structure, the sequences of scenes, the evocation of people and places, the importance of the story in moving the writing forward.

Lee Gutkind has explored the structure of the feature story in detail in his 2012 book You Can’t Make This Stuff Up . The structure of the feature story builds to a sense of climax — this could perhaps be a revelatory moment of insight. Gutkind makes the case for the importance of the scene ‘to communicate ideas and information as compellingly as possible,’ to keep the reader engaged through powerful story-telling, around which exposition can be arranged.

Writing for GQ , Jonathan Heaf begins his profile of Harrison Ford prior to the release of Star Wars: The Force Awakens , with a brutal, in-media-res opening paragraph:

‘I don’t want all this to take all f * ing day.’ The words Harrison Ford, 73, not so much spoke as snarled at me yesterday afternoon while discussing our lunch plans are still, 24 hours later, smarting like refined sugar hitting an exposed tooth cavity. Jonathan Heaf, ‘Harrison Ford on his change of heart about Han Solo’, GQ , January 2015

This appears to confirm some uncomfortable truths about Ford that Heaf — and by extension, we as readers — might have expected: Ford is invariably grumpy; Ford is an ungenerous interviewee; Ford is a formidable challenge. But by the end of the profile, having woven the narrative (his meeting with Ford, a ride in his Tesla Model S, lunch) with interview and exposition, Heaf describes telling Ford how much he’s looking forward to watching Star Wars: The Force Awakens :

He smiles. I turn to walk back to my rental and that’s when I hear it. “Me too, kid.” I very nearly glance back. Kid. He called me kid. For the first time all day, a flicker. One word, that’s all I needed. That ‘kid’, uttered in that tone, in his voice, fires my memory banks like a proton torpedo fired into a thermal exhaust port. Jonathan Heaf, ‘Harrison Ford on his change of heart about Han Solo’, GQ , January 2015

The centrality of the writer creates a kinship with a reader who has grown up with the same cultural tropes and shared, mimetic reference points. The structure of the writing allows Heaf to demonstrate the journey toward intimacy alluded to by Steensen. The Observer Magazine publishes around three features a week. Some are essentially pieces of investigative journalism into topics such as healing crystals (‘The New Stone Age’ by Eva Wiseman, June 2019) and Britain’s big cats, (‘Here, Kitty?’ by Mark Wilding, April 2019). Many, however, tell us something bigger about society in general: Eva Wiseman explores the well-being industry (‘Feel Better Now?’, March 2019). Joanna Moorhead learns about art therapy in prisons (‘Brushes With The Law’, May 2019). Alex Moshakis probes the big business of house plants (‘The Bloom Economy’, June 2019).

Some recount authentic, personal experiences — of sexuality (‘What My Queer Journey Taught Me About Love’, Amelia Abraham, May 2019) or of racing pigeons (‘Home to Roost’, Jon Day, June 2019). Other stories are contrived, for example, Emma Beddington transforms her dog into an Instagram star (‘Meet The World’s Most Unlikely Insta Star’, July 2019). There are often profiles of notable individuals, such as comedian Sara Pascoe (‘I wanted To Be Prime Minister’, Rebecca Nicholson, August 2019) and crossword writer Anna Schectman (‘Why It’s Hip To Be Square’ by Alex Moshakis).

Some tell really interesting stories — the fashion historian who solves crimes (‘Call The Fashion Police’, Eva Wiseman, March 2019). Others are about trends: the television box set (‘Why Box Sets Suck Us In’ by Will Storr, April 2019) and the male wellness sector (‘The Evolution of Man’ by Alex Moshakis, March 2019). Within each of these stories is really engaging content, things we can identify with, references we can share with the writer. The feature article has an important role, bringing people’s stories into play to lead us toward bigger truths and illuminating aspects of our culture and society.

If these features adopt Steensen’s ‘discourse of intimacy’, perhaps the travel feature best exemplifies the ‘discourse of adventure’. The writer Dan Richards, who specialises in travel and adventure, visited Finland’s Pellinge archipelago for 1843 (December 2019/January 2020) to explore the landscape that inspired Tove Jansson, author of the Moomin children’s books. Richards writes compellingly about the outdoors (his contribution to Holloway , which he co-authored with Robert Macfarlane, is lucid and lyrical) and here, he evokes the sparse beauty of the archipelago in his search for the places where Jansson lived and worked. The notion of a ‘search’, a sense of discovery at the heart of the narrative, is a crucial element of the ‘discourse of adventure’, even if for Richards, the island which inspired the Sommarboken [The Summer Book] remains elusive. Just as with Gay Talese’s search for Sinatra, here the adventure is the momentum of the narrative, even if the sought-after moment must be deferred.

Where are we now?

The turn of the twentieth century was marked by one of the most important cultural thresholds in society: the advent of the motion picture. Michael J Arlen is surely right when he argues that this was the significant moment when the feature article began to take on a sense of movement; when showing, rather than telling, came to the fore. It was only natural that writers should turn to fictional narrative as the toolkit. The importance of human subjectivity as central to aesthetic experience was a profound sea change that reflected wider socio-cultural changes: the decline of trust in authority, the erosion of the Enlightenment meta-narrative.

The essay, that long-established form of literary non-fiction, remains a crucial, vibrant form in its own right that can often be found in the package of the published ‘feature’. But the codes and conventions of narrative story-telling have become synonymous with the feature story, what Lee Gutkind prefers to call ‘creative non-fiction’.

Just as the influence of cinema was keenly felt, no doubt the influence of the web and the convergent device will begin to influence the adaptation of the feature story. The modus operandi of the ‘Mojo’ — the mobile journalist — asks the question of what the role of the feature article in today’s fast paced world might be — and the extent to which it can compete with the immediacy of images, video and the flow of social media feeds.

But just because we like our news reportage raw doesn’t mean we’re turned off to the payload of a great story. Steen Steensen has argued that feature journalism is transforming traditional ‘hard news’ in a process he calls the ‘featurization of journalism’ — the increasing dominance of feature-style journalism in newspapers. This, he writes, is often viewed by academics as an erosion of the social function of the press, ‘divert[ing] journalism towards what might interest the public instead of what is in the public’s interest, hence weakening the role of the news media in a democracy’. However, Steensen goes on to argue that in fact, the traditional genres of hard news and feature journalism have become entwined to some degree, in terms of discourse and social function, bringing ‘enlightenment and insight into complex and quintessential matters of culture and society.’

Steensen goes on to caution that the general transformation of news into something more ‘consumer-oriented, intimate and fiction-inspired’ might create a conflict of ‘intentions and expectations’. This is a judicious caveat in our post-truth culture. The feature story continues to feel like an urgent, exciting and relevant way to tell the stories of the people and places in our world. It will continue to stand as an important social function if we adhere to Lee Gutkind’s injunction to ‘be true to your story, true to your characters, true to yourself.’

Further Reading

Gutkind, Lee (2012) You Can’t Make This Stuff Up, Boston: Da Capo Press.

Harrington, H.F. (1912) Essentials in Journalism: A Manual in Newspaper Making for College Classes , Boston: The Athenaeum Press.

Arlen, Michael J (1972) ‘Notes on the New Journalism’, The Atlantic Monthly .

Hellmann, John (1977) ‘Fables of Fact: New Journalism Reconsidered’, The Centennial Review Vol. 21, No. 4.

Lepore, Jill (2019) ‘Does Journalism Have A Future? The New Yorker .

Murphy, James E (1974) ‘The New Journalism: A Critical Perspective’, Journalism Monographs , No. 34.

Steensen, Steen (2011) ‘The Featurization of Journalism’, Nordicom Review .

Wilke, Jürgen (1987) ‘Newspapers and their reporting – a long-term international comparison’ in Deutsche Presseforschung Bremen [German Press Research Bremen] (ed.): Presse und Geschichte [The press and its history], Munich 1987, vol. 2: Neue Beiträge zur historischen Kommunikationsforschung [New contributions to research on historical communication].

Wolfe, Tom (1970) ‘The New Journalism’, Bulletin [of the American Society of Newspaper Editors].

Dean, Walter ‘The lost meaning of “objectivity”‘, American Press Institute.

Marcus, Laura (2016) ‘Cinema and modernism’, The British Library.

Featured image by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- feature stories

- non-fiction

One thought on “ The indispensable guide to what makes a great feature story ”

- Pingback: The indispensable guide to what makes a great feature story — Anthony Cockerill – Experimental Film & Music Video Festival

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

How to build a feature story

By cristiana bedei sep 22, 2022 in journalism basics.

A feature is an exploration. It informs, inspires and entertains readers by going beyond hard facts and quotes, answering their questions about what is happening around the world.

While it was mostly seen as an article published in newspapers and magazines 10 or 20 years ago, finding a precise definition is more difficult today. Mary Hogarth , a media specialist, educator, and author of Writing Feature Articles: Print, Digital And Online , says that a strong feature should combine multimedia elements that will enhance the audience's experience and offer a 360-degree perspective of a topic: "It is critical to ensure that content not only has value but that it engages print/digital and online audiences."

Many freelancers choose feature writing also because it typically pays more. "The more words an editor commissions the more you'll earn. Research takes time, so try to get several stories out of one topic by tailoring the angle to several non-competing publications," said journalism coach and lecturer Susan Grossman . That may mean reframing and reselling your story elements at different times, for different audiences, and with different quotes.