How to develop a problem-solving mindset

May 14, 2023 Leaders today are confronted with more problems, of greater magnitude, than ever before. In these volatile times, it’s natural to react based on what’s worked best in the past. But when you’re solving the toughest business challenges on an ongoing basis, it’s crucial to start from a place of awareness. “If you are in an uncertain situation, the most important thing you can do is calm down,” says senior partner Aaron De Smet , who coauthored Deliberate Calm with Jacqueline Brassey and Michiel Kruyt. “Take a breath. Take stock. ‘Is the thing I’m about to do the right thing to do?’ And in many cases, the answer is no. If you were in a truly uncertain environment, if you’re in new territory, the thing you would normally do might not be the right thing.” Practicing deliberate calm not only prepares you to deal with the toughest problems, but it enhances the quality of your decisions, makes you more productive, and enables you to be a better leader. Check out these insights to learn how to develop a problem-solving mindset—and understand why the solution to any problem starts with you.

When things get rocky, practice deliberate calm

Developing dual awareness;

How to learn and lead calmly through volatile times

Future proof: Solving the ‘adaptability paradox’ for the long term

How to demonstrate calm and optimism in a crisis

How to maintain a ‘Longpath’ mindset, even amid short-term crises

Addressing employee burnout: Are you solving the right problem?

April Rinne on finding calm and meaning in a world of flux

How spiritual health fosters human resilience

A Positive Attitude for Problem Solving Skills

Introduction

Positive Attitude

Benefits of a positive attitude.

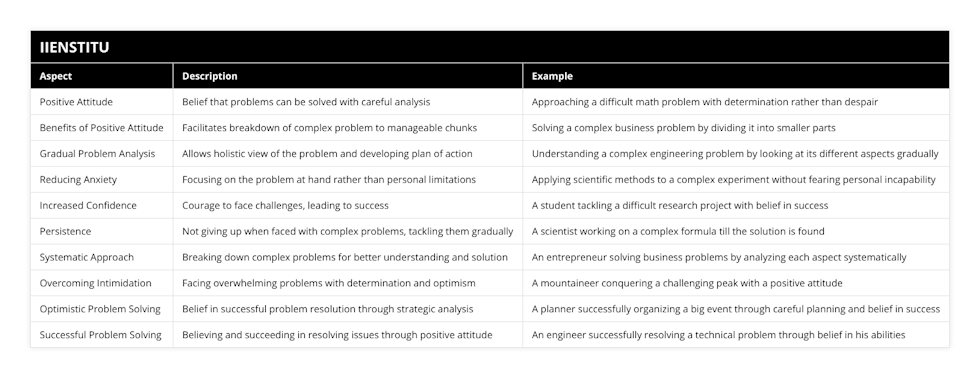

Introduction: Problem-solving is essential for success in many areas of life, from academics to the workplace. Good problem solvers can break down a problem and gradually analyze it, while poor problem solvers often lack the confidence and experience to do this. A positive attitude towards Problem-solving is essential for success, as it allows individuals to approach problems confidently and believe they can be solved. This article will explore the benefits of a positive attitude in issue-solving, with examples of how it can help.

Optimistic problem solvers strongly believe academic reasoning problems can be solved through careful, persistent analysis. This belief is essential, as it allows individuals to approach problems with confidence and determination rather than giving up before they have even begun. A positive attitude also helps to reduce fear and anxiety when approaching complex problems, as it allows individuals to focus on the issue at hand rather than on their own perceived limitations.

The benefits of a positive attitude in problem-solving are numerous. Firstly, it allows individuals to break down a problem into smaller, more manageable chunks. This makes it easier to analyze the situation, enabling individuals to focus on one part of the problem at a time. It also helps reduce the feeling of being overwhelmed or intimidated by a problem, as it allows individuals to tackle the problem more organized and systematically.

Another benefit of a positive attitude in problem-solving is that it encourages gradual problem analysis. Poor problem solvers often give up when faced with a complex problem, believing they will never be able to solve it. However, a positive attitude allows individuals to take a step back and look at the situation holistically, considering all aspects of the problem and gradually analyzing it. This will enable individuals to understand the problem better and develop a plan of action for solving it.

To illustrate the benefits of a positive attitude in problem-solving, consider the following examples. An individual struggling to solve a mathematical problem may become overwhelmed by the complexity of the problem and give up before they have even begun. However, if they take a step back and break the problem down into smaller parts, they may be able to analyze it and come to a solution gradually. Similarly, an individual struggling to solve a complex business problem may feel overwhelmed by the complexity of the problem and give up. However, if they take a step back and break the problem down into smaller parts, they may be able to analyze it and come to a solution gradually.

TRIZ: Exploring the Revolutionary Theory of Inventive Problem Solving

7 Problem Solving Skills You Need to Succeed

Exploratory Data Analysis: Unraveling its Impact on Decision Making

Failure Tree Analysis: Effective Approach for Risk Assessment

Conclusion: In conclusion, having a positive attitude towards problem-solving is essential for success. It allows individuals to approach problems confidently and believe they can be solved. It also allows individuals to break down a problem into smaller parts and gradually analyze it, reducing feeling overwhelmed or intimidated by a crisis. Examples of how a positive attitude can help in problem-solving are provided, illustrating the importance of a positive attitude.

A positive attitude is critical to unlocking problem-solving skills. IIENSTITU

What is the definition of problem solving?

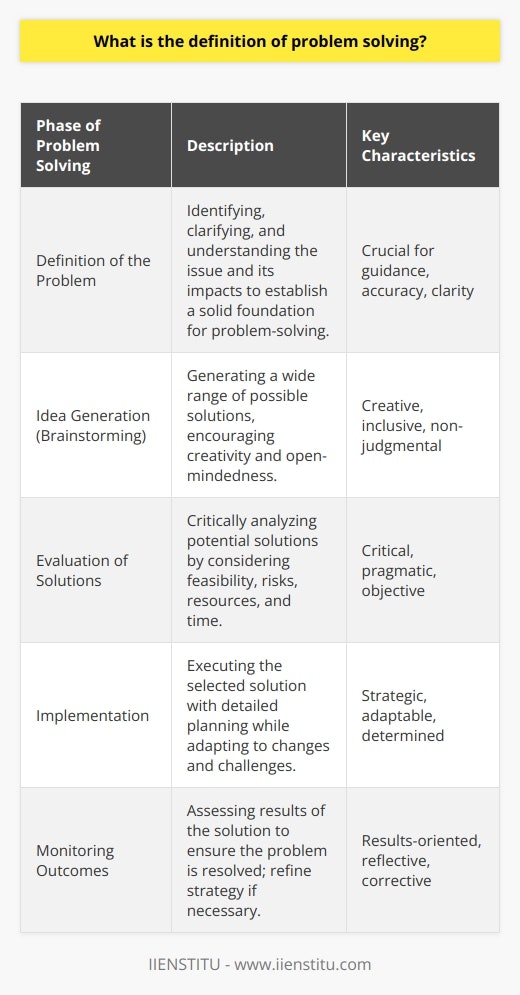

Problem-solving is a critical cognitive process involving identifying and resolving issues or obstacles. It requires the individual to analyze a problem, determine potential solutions, evaluate them, and then implement the most effective solution. Problem-solving can be defined as a cognitive process that allows individuals and groups to identify and address problems, develop potential solutions, and make decisions that lead to successful problem resolution.

The process of problem-solving is often broken down into five stages: defining the problem, generating possible solutions, evaluating the solutions, implementing the chosen solution, consists in and monitoring the outcome.

The first stage involves defining the problem by gathering information about the situation and breaking down the problem into manageable components.

The second stage involves generating possible solutions by brainstorming, researching, and consulting with experts.

The third stage consists in evaluating the answers and selecting the best one.

The fourth stage involves implementing the chosen solution.

The fifth stage involves monitoring the outcome to assess whether the solution was successful.

Problem-solving is a complex process, and the outcome's success depends on the individual's ability to analyze the problem, identify potential solutions, and evaluate the solutions before implementing the best solution. It requires individuals to think critically, use creativity and draw on their knowledge and experience. It also needs individuals to be flexible and open to different approaches and solutions.

Problem-solving is an essential skill that people use in their everyday lives. It is necessary for the successful functioning of society, as it enables individuals and groups to identify and address problems, develop potential solutions, and make decisions that lead to successful problem resolution.

How does having a positive attitude help with problem solving?

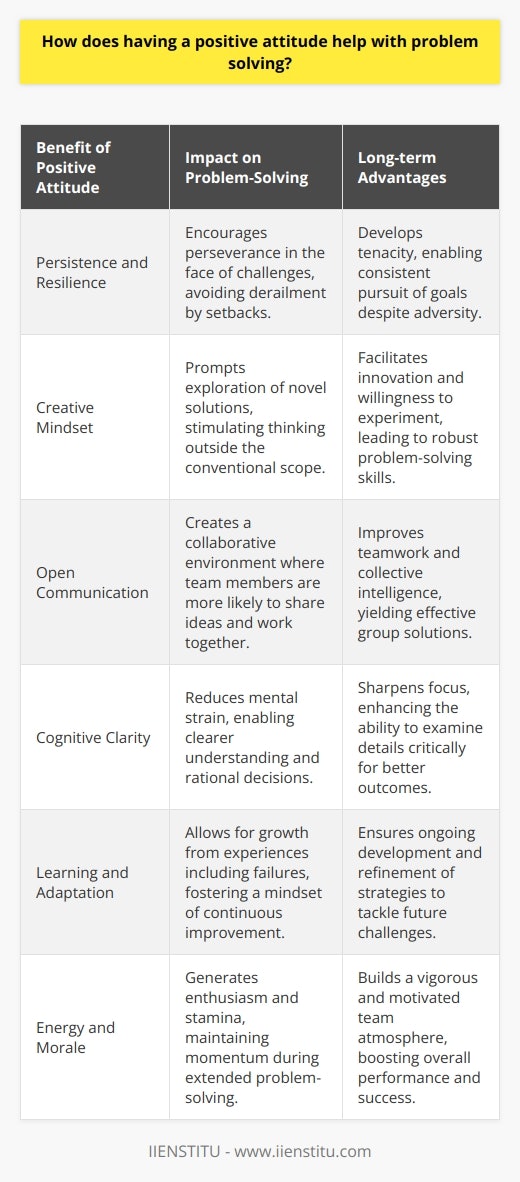

A positive attitude when approaching a problem can be a great asset in finding a solution. It is often said that attitude is everything, and this is especially true when it comes to problem-solving. A positive attitude can lead to a more creative approach to problem-solving and increase the likelihood of finding a successful solution.

A positive attitude can help to increase motivation when approaching a problem. This can be a great asset in helping to identify the root cause of the problem and find a solution. In addition, with a positive attitude, an individual is more likely to take on the challenge of solving the problem rather than avoiding it or simply giving up.

Having a positive attitude can also help to promote constructive thinking. That is, thinking that focuses on solutions rather than playing the blame game or worrying about the consequences of failure. A positive attitude can help to keep the focus on finding solutions and staying motivated to work through the problem until a successful outcome is achieved.

In addition, having a positive attitude can help to reduce stress when tackling a problem. This can be invaluable in helping to maintain a clear mind and allow for the type of creative thinking that is often necessary when finding solutions. A positive attitude can help to keep the individual focused on the task at hand and help to prevent a feeling of being overwhelmed by the problem.

Finally, having a positive attitude can help to create a positive environment when approaching a problem. That environment encourages collaboration and brainstorming and promotes the exchange of ideas. This can be key to finding a successful solution.

In conclusion, having a positive attitude when approaching a problem can be a great asset in finding a successful solution. A positive attitude can help to increase motivation, promote constructive thinking, reduce stress, and create a positive environment when approaching a problem.

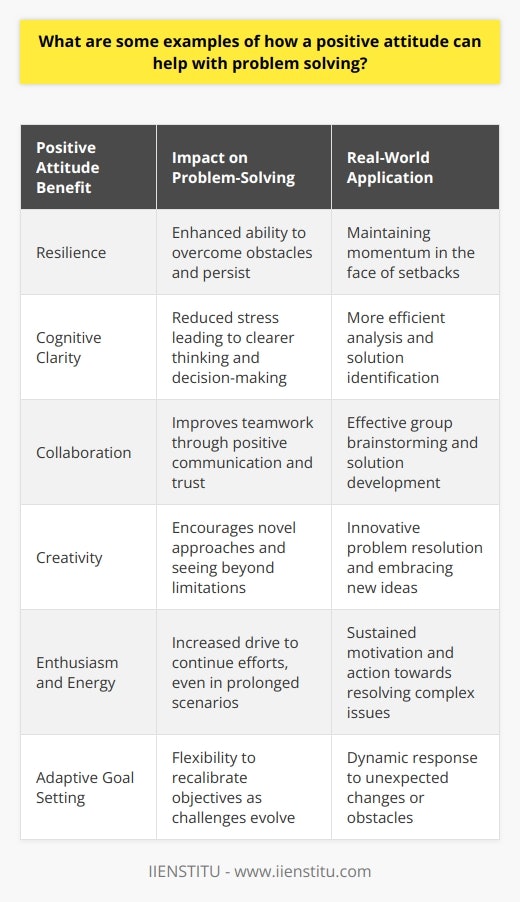

What are some examples of how a positive attitude can help with problem solving?

A positive attitude when facing a problem can be incredibly beneficial in solving it. Viewing the problem as an opportunity to learn and grow rather than a hurdle that cannot be overcome is essential. With the right attitude, problems can be solved more effectively and quickly.

One way that a positive attitude can help with problem-solving is by increasing motivation and perseverance. People with a positive attitude are likelier to persist in issue-solving and not give up when the going gets tough. With this attitude, it is more likely that a solution will be found.

Another way that a positive attitude can help with problem-solving is by providing greater clarity and focus. People with a positive attitude are more likely to take a step back and look at a situation objectively, allowing them to understand the problem better and develop a plan for solving it. This clarity and focus can also help to prevent distractions from derailing the problem-solving process.

Finally, a positive attitude can help to foster creativity and innovation. People with a positive attitude are more likely to look at a problem from a different perspective, allowing them to come up with creative solutions that would not have been considered otherwise. This creativity can be incredibly beneficial in finding a solution to a tricky problem.

In conclusion, I have a positive attitude when problem-solving can be immensely beneficial. It can increase motivation, provide clarity and focus, and foster creativity and innovation, all of which are important in finding a solution to a problem. Therefore, it is essential to maintain a positive attitude when facing a problem to maximize the chances of finding a solution.

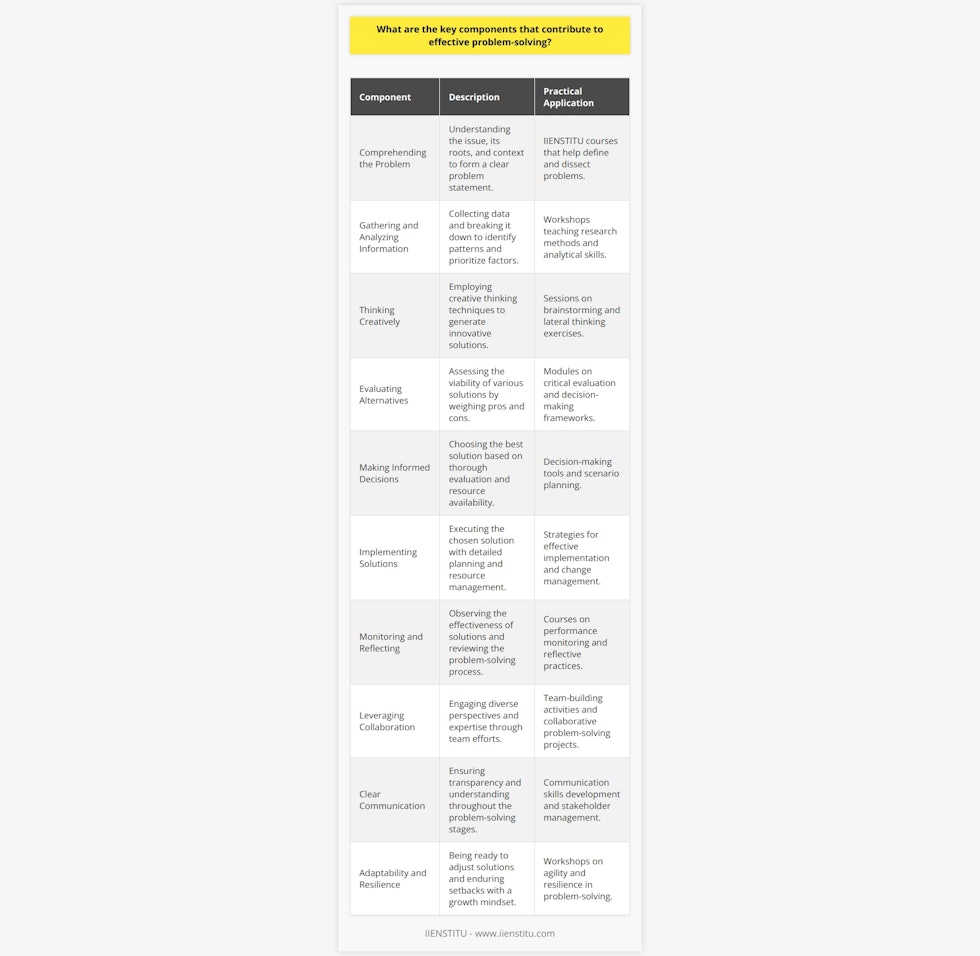

What are the key components that contribute to effective problem-solving?

Key Components of Effective Problem-Solving Understanding the Situation The first component of effective problem-solving is understanding the situation properly. This entails gathering comprehensive information about the problem and defining it explicitly. Accurate problem identification enables the problem-solver to establish relevant goals and objectives that are critical in devising feasible solutions. Exploring Multiple Perspectives Divergent thinking, or exploring multiple perspectives, is the second key component. It involves considering different viewpoints, opinions, and beliefs in order to identify various aspects of the problem. By being open-minded and considering different alternatives, a problem solver can generate multiple potential solutions, increasing the likelihood of developing an effective and creative resolution. Critical Thinking and Analysis The third key component is critical thinking and analysis, involving the evaluation of the problem and potential solutions. By analyzing each solution's pros and cons, the problem solver can determine the most appropriate course of action. Factoring in the feasibility, practicality, and effectiveness of each solution allows for selecting the most viable option that adheres to predetermined goals and objectives. Decision Making and Implementation The fourth component is decision making and implementation, which requires selecting the best solution and putting it into practice. It is crucial to consider the potential consequences and necessary resources while taking decisive action. Effective problem-solving involves continual assessment and adjustments to improve and refine the chosen solution. Collaboration and Communication Lastly, collaboration and communication play a significant role in problem-solving. Consulting with other individuals can offer fresh insights, ideas, and expertise, which can greatly enhance the problem-solving process. Furthermore, clear and concise communication is essential in conveying the problem, proposed solutions, and implementation strategies to all relevant stakeholders. In conclusion, effective problem-solving is a multifaceted process that involves understanding the situation, exploring multiple perspectives, employing critical thinking and analysis, making decisions and implementing solutions, and cultivating collaboration and communication. By mastering these components, individuals and teams can successfully address various challenges and achieve their goals.

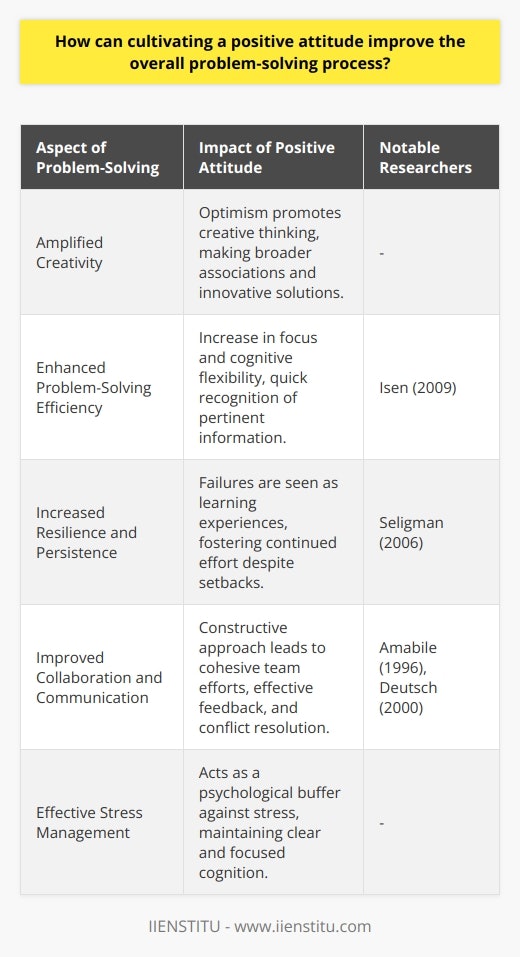

How can cultivating a positive attitude improve the overall problem-solving process?

Significance of a Positive Attitude Cultivating a positive attitude plays a vital role in enhancing the problem-solving process by fostering creativity and increasing motivation to succeed. When an individual approaches a problem with a positive mindset, they are more likely to engage in divergent thinking, where multiple solutions are explored to reach an optimal outcome (Isen, 2009). This perspective enables them to consider various alternative paths, leading to increased adaptability and a more manageable pathway towards resolution. Impact on Cognitive Abilities A positive attitude also enhances cognitive abilities, allowing individuals to effectively process information, identify patterns, and make logical connections (Fredrickson, 2004). By focusing on the potential for success, the brain can more efficiently organize and analyze relevant data, improving the quality of the decision-making process. Furthermore, optimism bolsters resilience and persistence, as individuals are more likely to view setbacks as temporary obstacles rather than insurmountable barriers (Seligman, 2006). Collaboration and Conflict Resolution Positive attitude extends beyond personal cognitive benefits and has the potential to improve group dynamics when solving complex problems collectively. By promoting a constructive environment, individuals are encouraged to share ideas, learn from others, and support their peers in formulating creative solutions (Amabile, 1996). Moreover, a positive attitude facilitates effective conflict resolution, as individuals are more predisposed to understand alternative viewpoints and collaborate to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes (Deutsch, 2000). Conclusion In conclusion, cultivating a positive attitude yields numerous benefits for the overall problem-solving process. By stimulating divergent thinking, enhancing cognitive abilities, and fostering effective collaboration among team members, individuals with a positive mindset can overcome challenges and develop innovative solutions. Therefore, embracing optimism and resilience significantly improves not only one’s personal problem-solving skills but also fosters a supportive environment where the collective intelligence thrives.

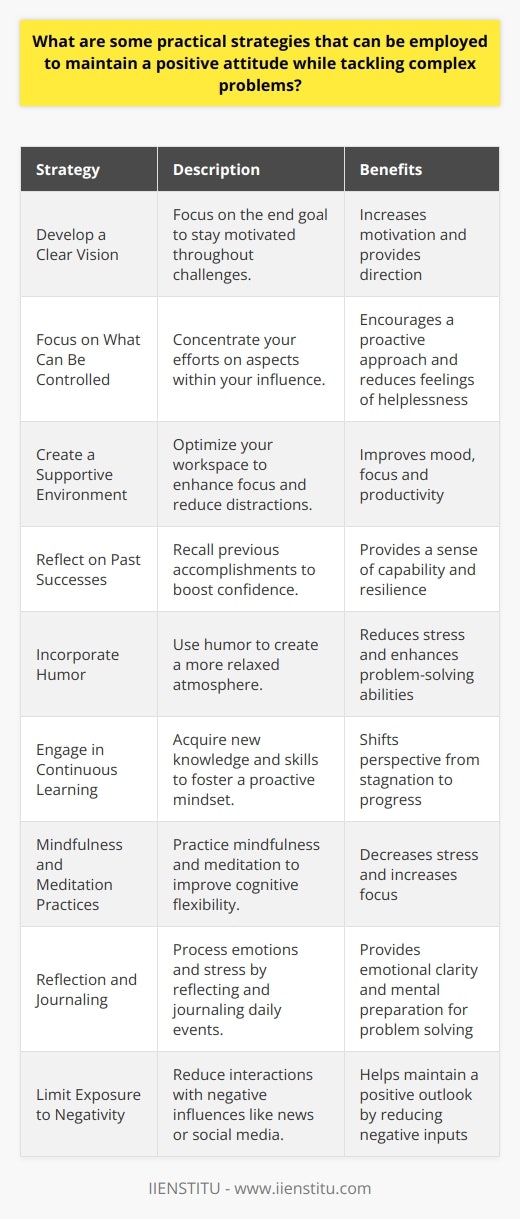

What are some practical strategies that can be employed to maintain a positive attitude while tackling complex problems?

Practical strategies for maintaining a positive attitude Cultivating a growth mindset One practical strategy for maintaining a positive attitude while tackling complex problems is cultivating a growth mindset. This involves embracing challenges, viewing failures as opportunities to learn and persisting in the face of obstacles. Setting smaller, achievable goals Another strategy is setting smaller, achievable goals. Breaking the complex problem down into manageable tasks helps make it less daunting and encourages progress. Completion of each smaller task provides a sense of accomplishment, motivating continued efforts. Adopting effective time management Implementing effective time management not only improves efficiency but also reduces stress. Prioritising tasks, setting realistic deadlines and incorporating breaks into the schedule ensures steady progress and protects against burnout. Emphasising mental and physical well-being Maintaining mental and physical well-being is crucial for sustaining a positive attitude. Prioritising sleep, nutrition, exercise and relaxation promotes a healthy mindset, better focus and increased resilience when faced with difficult problems. Surrounding oneself with positivity Our social environment can significantly impact our attitude. Surrounding oneself with positive, supportive and like-minded individuals helps create an uplifting environment conducive to problem-solving. Practicing self-compassion Recognising that everyone experiences occasional setbacks is essential for maintaining a positive attitude. Instead of being self-critical, practice self-compassion, accepting the present circumstances and focusing on what can be controlled and improved. Using positive affirmations Positive affirmations are statements that promote a positive mindset and stress resilience. Repeating these affirmations throughout the day can help boost self-esteem, motivation and overall attitude. Seeking external resources Lastly, seeking external resources like books, articles, online courses or even consulting with experts can provide valuable insights and tools for solving complex problems. These resources augment understanding and foster a sense of empowerment. In conclusion, incorporating various practical strategies such as cultivating a growth mindset, setting smaller goals, managing time effectively, prioritising well-being, surrounding oneself with positivity, practicing self-compassion, using positive affirmations and seeking external resources can help maintain a positive attitude while tackling complex problems. These approaches not only facilitate problem-solving but also improve overall resilience and well-being.

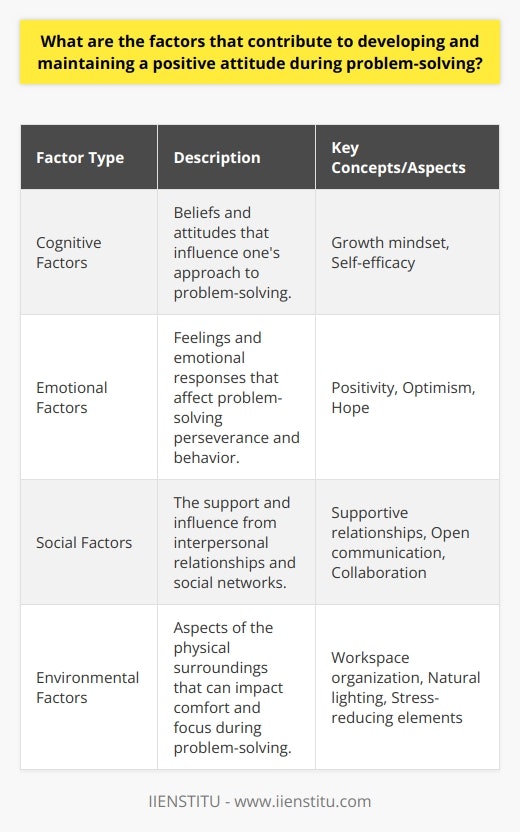

What are the factors that contribute to developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving?

Factors Influencing Positive Attitude Development Various factors contribute to developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving, which can enhance an individual's overall performance and success in finding effective solutions. These factors include cognitive, emotional, social, and environmental aspects. Cognitive Factors The cognitive factors involve an individual's inherent beliefs, perceptions, and thought patterns. A growth mindset, which embraces challenges and views effort as a pathway to improvement, is critical for fostering a positive attitude during problem-solving. Additionally, self-efficacy, or the belief in one's ability to achieve a desired outcome, can boost problem-solving efficiency and facilitate a positive attitude. Emotional Factors Positive emotions, like optimism and hope, play a vital role in maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving. Optimism fosters resilience and encourages an individual to face challenges with a constructive approach. Further, hope promotes goal-directed thinking, adaptive coping strategies, and heightened motivation, which influence one's problem-solving attitude positively. Social Factors The social environment, including the presence of supportive peers, mentors, or supervisors, can contribute to a positive attitude development during problem-solving. Individuals in encouraging social contexts are more likely to feel confident and motivated to tackle challenges. Collaboration and teamwork can also facilitate diverse perspectives and creative solutions, promoting a constructive problem-solving attitude. Environmental Factors Lastly, the physical environment can impact an individual's attitude while addressing problems. A comfortable, organized, and functional workspace can foster focus, productivity, and a positive attitude. Additionally, implementing stress-relief techniques, such as regular breaks and stress-relieving activities, can foster a relaxed state of mind, essential for problem-solving. In conclusion, developing and maintaining a positive attitude during problem-solving involves a holistic approach that takes into account cognitive, emotional, social, and environmental factors. Cultivating a growth mindset, nurturing positive emotions, fostering supportive social connections, and optimizing the physical environment can significantly enhance an individual's problem-solving attitude and performance.

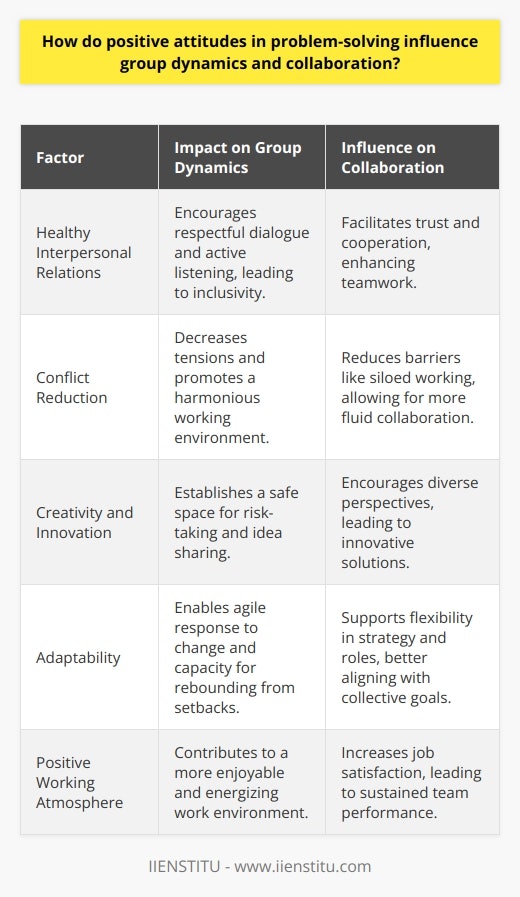

How do positive attitudes in problem-solving influence group dynamics and collaboration?

Impact on Group Dynamics Positive attitudes in problem-solving significantly affect group dynamics by fostering healthy communication channels, active participation, and commitment. With a solution-oriented mindset, group members tend to focus more on finding common ground, thereby minimizing conflicts and misunderstandings. As individuals distinctly acknowledge the potential of diverse perspectives in the resolution of complex tasks, they adopt a proactive approach to engaging with others. Enhancing Collaboration In addition, a positive problem-solving atmosphere promotes a sense of shared responsibility among group members. This feeling of connectedness paves the way for smooth collaboration, allowing individuals to leverage their strengths in achieving a shared objective. When group members support one another in overcoming challenges, they build trust and strengthen their interdependence, which is crucial for promoting a cohesive team culture. Promoting Creativity and Innovation Moreover, positive attitudes in problem-solving stimulate creativity and innovation within groups, as participants feel more comfortable sharing their ideas and thinking outside the box. By fostering an environment that celebrates diverse thinking and encourages open discussions, groups harness a wealth of knowledge that ultimately leads to the generation of novel solutions to complex issues. Encouraging Adaptability Furthermore, groups with a positive problem-solving outlook demonstrate high adaptability and resilience when encountering unexpected obstacles or setbacks. By focusing on solutions rather than dwelling on failure, members develop a sense of empowerment and determination. This, in turn, increases the group's overall capacity to develop and implement effective strategies that address the task at hand. Conclusion In summary, positive attitudes in problem-solving significantly influence group dynamics and collaboration by facilitating effective communication, fostering collective responsibility, stimulating creativity, and promoting adaptability. By cultivating a constructive and solution-oriented environment, groups can enhance their overall effectiveness and maximize their potential in achieving desired outcomes.

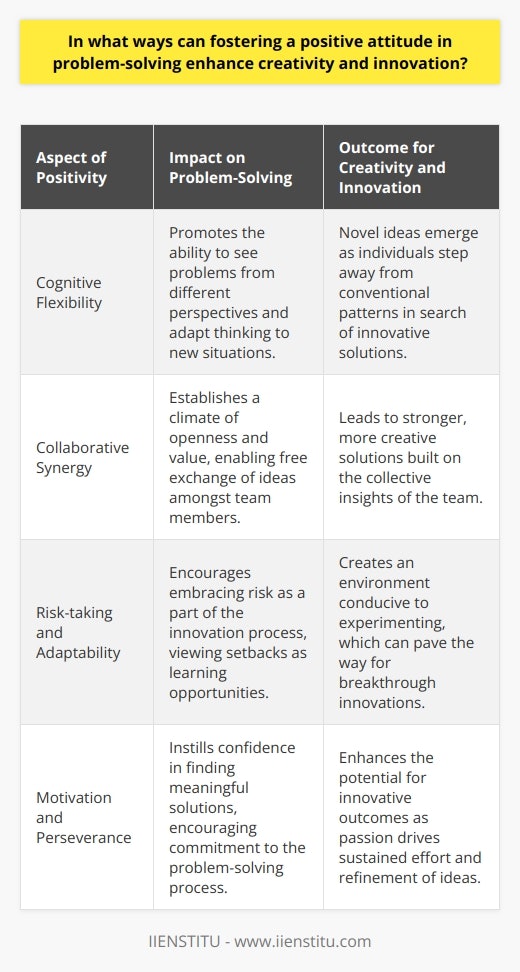

In what ways can fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving enhance creativity and innovation?

The Impact of a Positive Attitude Fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving significantly influences creativity and innovation within individuals and organizations. A positive mindset toward problem-solving allows the individual to explore more possibilities, yielding dynamic approaches for resolving issues. The Role of Cognitive Flexibility One crucial aspect of this influence is cognitive flexibility, which is the ability to think about a problem from multiple perspectives and generate diverse ideas. A positive attitude improves cognitive flexibility by encouraging individuals to focus on the potential benefits of generating innovative solutions, rather than dwelling on the difficulties faced in arriving at those solutions. This shift in focus enhances creative thinking by expanding the range of ideas and perspectives explored. Encouragement of Collaboration Additionally, a positive attitude promotes collaboration and knowledge sharing among team members, fostering a synergistic environment that supports idea generation and innovation. When individuals approach problem-solving with optimism, they are more open to hearing and learning from others' perspectives, facilitating the exchange of valuable insights and ideas. Embracing Risk-taking and Uncertainty Furthermore, a positive mindset empowers individuals to embrace risks and uncertainties associated with innovative problem-solving. By considering setbacks and failures as opportunities for learning and improvement, individuals can develop resilience and adaptability, vital traits for creativity and innovation. A positive attitude toward problem-solving encourages experimentation and learning, cultivating a growth mindset that fuels innovation. Enhanced Motivation and Persistence Finally, a positive attitude bolsters motivation and persistence in the face of challenging problems. When individuals believe in their ability to find solutions and the potential value of their ideas, they become more passionate about the problem-solving process. They are more likely to continue exploring and refining ideas, resulting in an increase in creative output and the development of innovative solutions. In conclusion, fostering a positive attitude in problem-solving can greatly enhance creativity and innovation by supporting cognitive flexibility, encouraging collaboration, embracing risk-taking and uncertainty, and bolstering motivation and persistence. Therefore, individuals and organizations should invest in cultivating a positive outlook for improved problem-solving outcomes, driving overall success.

Yu Payne is an American professional who believes in personal growth. After studying The Art & Science of Transformational from Erickson College, she continuously seeks out new trainings to improve herself. She has been producing content for the IIENSTITU Blog since 2021. Her work has been featured on various platforms, including but not limited to: ThriveGlobal, TinyBuddha, and Addicted2Success. Yu aspires to help others reach their full potential and live their best lives.

What are Problem Solving Skills?

3 Apps To Help Improve Problem Solving Skills

How To Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

Improve Your Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Skills

Edison's 99%: Problem Solving Skills

How To Become a Great Problem Solver?

Definition of Problem-Solving With Examples

A Problem Solving Method: Brainstorming

Problem-Solving Mindset: How to Achieve It (15 Ways)

One of the most valuable skills you can have in life is a problem-solving mindset. It means that you see challenges as opportunities to learn and grow, rather than obstacles to avoid or complain about. A problem-solving mindset helps you overcome difficulties, achieve your goals, and constantly improve yourself. By developing a problem-solving mindset, you can become more confident, creative, and resilient in any situation.A well-defined problem paves the way for targeted, effective solutions. Resist the urge to jump straight into fixing things. Invest the time upfront to truly understand what needs to be solved. Starting with the end in mind will make the path to resolution that much smoother.

Sanju Pradeepa

* This Post may contain affiliate Links, and we receive an affiliate commission for any purchases made by you using such links. *

Ever feel like you’re stuck in a rut with no way out? We’ve all been there. The problems life throws at us can seem insurmountable. But the truth is, you have everything you need to overcome any challenge already within you. It’s called a problem-solving mindset. Developing the ability to see problems as puzzles to solve rather than obstacles to overcome is a game changer. With the right mindset, you can achieve amazing things.

In this article, we’ll explore what having a problem-solving mindset really means and how you can cultivate one for yourself. You’ll learn proven techniques to shift your perspective, expand your creativity, and find innovative solutions to your biggest problems. We’ll look at examples of people who have used a problem-solving mindset to accomplish extraordinary feats. By the end, you’ll have the tools and inspiration to transform how you think about and approach problems in your own life.

Table of Contents

What is a problem-solving mindset.

A problem solving mindset is all about approaching challenges in a solution-focused way. Rather than feeling defeated by obstacles, you look at them as puzzles to solve. Developing this mindset takes practice, but the rewards of increased resilience, creativity and confidence make it worth the effort.

- Identify problems, not excuses. Rather than blaming external factors, look for the issues within your control. Ask yourself, “What’s really going on here and what can I do about it?”

- Focus on solutions, not problems. Once you’ve pinpointed the issue, brainstorm options to fix it. Don’t get stuck in a negative loop. Shift your mindset to answer the question, “What are some possible solutions?”

- Look for opportunities, not obstacles. Reframe the way you view problems. See them as chances to improve and learn, rather than roadblocks stopping your progress. Ask, “What’s the opportunity or lesson here?”

- Start small and build up. Don’t feel overwhelmed by big challenges. Break them into manageable steps and celebrate small wins along the way. Solving little problems builds your confidence to tackle bigger issues.

Be patient with yourself and maintain an open and curious attitude . With regular practice, you’ll get better at seeing the solutions, rather than the obstacles. You’ll become more flexible and innovative in your thinking. And you’ll discover that you have the ability to solve problems you once thought insurmountable. That’s the power of a problem-solving mindset.

Why Developing a Problem Solving Mindset Is Important

Developing a problem-solving mindset is crucial these days. Why? Because life throws curveballs at us constantly and the only way to overcome them is through creative solutions.

Having a problem-solving mindset means you view challenges as opportunities rather than obstacles. You approach them with curiosity and optimism instead of dread. This allows you to see problems from new angles and come up with innovative solutions.

Some key characteristics of a problem-solving mindset include:

- Flexibility. You’re open to different perspectives and willing to consider alternative options.

- Creativity. You think outside the box and make unexpected connections between ideas.

- Persistence. You don’t give up easily in the face of difficulties or setbacks. You continue experimenting and adjusting your approach.

- Adaptability. You accept change and are able to quickly adjust your strategies or plans to suit new situations.

- Resourcefulness. You make the most of what you have access to and find ways to overcome limitations.

Developing a problem-solving mindset takes conscious effort and practice.

The Key Characteristics of Effective Problem Solvers

To become an effective problem solver, you need to develop certain characteristics and mindsets. Here are some of the key traits shared by great problem solvers:

1. Openness to New Ideas

Effective problem solvers have an open and curious mind. They seek out new ways of looking at problems and solutions. Rather than dismissing ideas that seem “out there,” they explore various options with an open mind.

2. Flexibility

Great problem solvers are flexible in their thinking. They can see problems from multiple perspectives and are willing to adapt their approach. If one solution isn’t working, they try another. They understand that there are many paths to solving a problem.

3. Persistence

Solving complex problems often requires persistence and determination. Effective problem solvers don’t give up easily. They continue exploring options and trying new solutions until they find one that works. They see setbacks as learning opportunities rather than failures.

Why Persistence is Important: 8 Benefits & 6 Ways to Develop

4. creativity.

Innovative problem solvers think outside the box . They make unexpected connections and come up with unconventional solutions. They utilize techniques like brainstorming, mind mapping, and lateral thinking to spark new ideas.

5. Analytical Thinking

While creativity is key, problem solvers also need to be able to evaluate solutions in a logical and analytical manner. They need to be able to determine the pros and cons, costs and benefits, and potential obstacles or issues with any solution. They rely on data, evidence, and objective reasoning to make decisions.

7 Types of Critical Thinking: A Guide to Analyzing Problems

How to cultivate a problem-solving mindset.

To cultivate a problem-solving mindset, you need to develop certain habits and ways of thinking. Here are some tips to get you started:

1. Look for Opportunities to Solve Problems

The more you practice problem solving, the better you’ll get at it. Look for opportunities in your daily life to solve small problems. This could be figuring out a better way to organize your tasks at work or coming up with a solution to traffic in your neighborhood. Start with small, low-risk problems and work your way up to more complex challenges.

2. Ask Good Questions

One of the most important skills in problem solving is asking good questions. Questions help you gain a deeper understanding of the issue and uncover new perspectives. Ask open-ended questions like:

- What’s the real problem here?

- What are the underlying causes?

- Who does this impact and how?

- What has been tried before? What worked and what didn’t?

3. Do Your Research

Don’t go into problem solving blind. Do some research to gather relevant facts and data about the situation. The more you know, the better equipped you’ll be to come up with innovative solutions. Talk to people with different viewpoints and life experiences to gain new insights.

4. Brainstorm Many Options

When you start thinking of solutions, don’t settle for the first idea that comes to mind. Brainstorm many options to open up possibilities. The more choices you have, the more likely you are to discover an unconventional solution that really fits the needs of the situation. Think outside the box!

5. Evaluate and Decide

Once you have a list of possible solutions, evaluate each option objectively based on criteria like cost, time, and effectiveness. Get input from others if needed. Then make a decision and take action. Even if it’s not the perfect solution, you can make changes as you go based on feedback and results.

6. Question your beliefs

The beliefs and assumptions you hold can influence how you perceive and solve problems. Ask yourself:

- What beliefs or stereotypes do I have about this situation or the people involved?

- Are these beliefs grounded in facts or just my personal experiences?

- How might my beliefs be limiting my thinking?

Challenging your beliefs helps you see the problem with fresh eyes and identify new solutions.

The Ultimate Guide of Overcoming Self-Limiting Beliefs

7. seek different perspectives.

Get input from people with different backgrounds, experiences, and thought processes than your own. Their unique perspectives can reveal new insights and spark innovative ideas. Some ways to gain new perspectives include:

- Discuss the problem with colleagues from different departments or areas of expertise.

- Interview customers or clients to understand their needs and priorities.

- Consult experts in unrelated fields for an outside-the-box opinion.

- Crowdsource solutions from people of diverse ages, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

8. Look beyond the obvious

We tend to focus on the most conspicuous or straightforward solutions, but the best option isn’t always obvious. Try these techniques to stimulate unconventional thinking:

- Restate the problem in new ways. A new phrasing can reveal alternative solutions.

- Remove constraints and imagine an ideal scenario. Then work backwards to find realistic options.

- Make unexpected associations between the problem and unrelated concepts or objects. Look for parallels and analogies in different domains.

- Play with hypothetical scenarios to find combinations you may not logically deduce. Some of the wildest ideas can lead to innovative solutions!

With an open and curious mindset, you can overcome assumptions, gain new insights, and find unconventional solutions to your most complex problems. The key is looking at the situation in new ways and exploring all possibilities.

Mindset is Everything: Reprogram Your Thinking for Success

9. practice active listening.

To become an effective problem solver, you need to practice active listening. This means paying close attention to what others are saying and asking follow-up questions to gain a deeper understanding of the issues.

Listen without judgment

When someone is explaining a problem to you, listen with an open mind. Avoid interrupting or criticizing them. Your role is to understand their perspective and concerns, not pass judgment. Nod, make eye contact, and give verbal affirmations like “I see” or “go on” to show you’re engaged.

Ask clarifying questions

If something is unclear or you need more details, ask questions. Say something like, “Can you explain that in more detail?” or “What specifically do you mean by that?” The more information you have about the problem, the better equipped you’ll be to solve it. Ask open-ended questions to encourage the other person to elaborate on their points.

Paraphrase and summarize

Repeat back parts of what the speaker said in your own words to confirm you understood them correctly. Say something like, “It sounds like the main issues are…” or “To summarize, the key points you’re making are…” This also shows the other person you were paying attention and care about addressing their actual concerns.

10. Withhold suggestions initially

When someone first presents you with a problem, avoid immediately suggesting solutions. Your first task is to understand the issue thoroughly. If you start proposing solutions too soon, it can seem like you’re not really listening and are just waiting for your turn to talk. Get clarification, summarize the issues, and ask any follow up questions needed before offering your input on how to solve the problem.

Developing the patience and discipline to actively listen takes practice. But by listening without judgment, asking clarifying questions, paraphrasing, and withholding suggestions initially, you’ll gain valuable insight into problems and be better equipped to solve them. Active listening is a skill that will serve you well in all areas of life.

11. Ask Lots of Questions

To solve problems effectively, you need to ask lots of questions. Questioning helps you gain a deeper understanding of the issue, uncover hidden factors, and open your mind to new solutions.

Asking “why” helps you determine the root cause of the problem. Keep asking “why” until you reach the underlying reason. For example, if sales numbers are down, ask why. The answer may be that you lost a key client. Ask why you lost the client. The answer could be poor customer service. Ask why the customer service was poor. And so on. Getting to the root cause is key to finding the right solution.

Challenge Assumptions

We all have implicit assumptions and biases that influence our thinking. Challenge any assumptions you have about the problem by asking questions like:

- What if the opposite is true?

- What are we missing or ignoring?

- What do we think is impossible but perhaps isn’t?

Questioning your assumptions opens you up to new perspectives and innovative solutions.

12. Consider Different Viewpoints

Try to see the problem from multiple angles by asking:

- How do others see this problem?

- What solutions might employees, customers, or experts suggest?

- What would someone from a different industry or background recommend?

Getting input from people with diverse experiences and ways of thinking will lead to better solutions.

13. Brainstorm New Possibilities

Once you have a good understanding of the root problem, start generating new solutions by asking open-ended questions like:

- What if anything were possible, what solutions come to mind?

- What are some wild and crazy ideas, even if implausible?

- What solutions have we not yet thought of?

Don’t judge or evaluate ideas at this stage. Just let the questions spark new creative solutions. The more questions you ask, the more solutions you’ll discover. With an inquisitive mindset, you’ll be well on your way to solving any problem.

14. Document what you find

As you research, keep notes on key details, facts, statistics, examples, and advice that stand out as most relevant or interesting. Look for common themes and threads across the different resources. Organize your notes by topic or theme to get a better sense of the big picture. Refer back to your notes to recall important points as you evaluate options and determine next steps.

Doing thorough research arms you with the knowledge and understanding to develop effective solutions. You’ll gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of the problem and be able to make more informed choices. Research also exposes you to new ideas you may not have considered. While it requires an investment of time, research is a crucial step for achieving an optimal solution.

15. Start With the End in Mind: Define the Problem Clearly

To solve a problem effectively, you need to first define it clearly. Without a concrete understanding of the issue at hand, you’ll waste time and energy grappling with a vague, nebulous challenge.

Identify the root cause

Ask probing questions to determine the underlying reason for the problem. Get specific by figuring out who is affected, what’s not working, where the breakdown is happening, when it started, and why it’s an issue. Look beyond the symptoms to find the source. The solution lies in resolving the root cause, not just alleviating surface-level pain points.

Gather objective data

Rely on facts, not opinions or assumptions. Observe the situation directly and collect information from multiple sources. Get input from people with different perspectives. Hard data and evidence will give you an accurate, unbiased view of the problem.

Define constraints and priorities

Determine any restrictions around time, money, resources, or policies that could impact your solution. Also identify what’s most important to solve—you can’t fix everything at once. Focus on high-priority issues and leave lower-priority problems for another time.

Frame the problem statement

With a clear understanding of the root cause, supporting data, and constraints, you can craft a concise problem statement. This articulates the issue in 1 or 2 sentences and serves as a guiding vision for developing solutions. Refer back to your problem statement regularly to ensure you stay on track.

Final Thought

Developing a problem-solving mindset is within your reach if you commit to continuous learning, looking at challenges from new angles, and not being afraid to fail. Start small by picking one problem each day to solve in a creative way. Build up your confidence and skills over time through practice.

While it may feel uncomfortable at first, having an adaptable and solution-focused mindset will serve you well in all areas of life. You’ll be able to navigate obstacles and setbacks with more ease and grace. And who knows, you may even start to enjoy the problem-solving process and see problems as opportunities in disguise. The problem-solving mindset is a gift that keeps on giving. Now go out there, face your challenges head on, and solve away!

Solve It!: The Mindset and Tools of Smart Problem Solvers by Dietmar Sternad

- Creative Problem Solving as Overcoming a Misunderstanding by Maria Bagassi and Laura Macchi * (Department of Psychology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Milan, Italy) ,

- Mindsets: A View From Two Eras by Carol S. Dweck 1 and David S. Yeager 2 published in National Library of Medicine ( Perspect Psychol Sci. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2020 May 1. Published in final edited form as: Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019 May; 14(3): 481–496. )

Call to Action

With regular practice, a problem solving mindset can become second nature. You’ll get better at seeing opportunities, asking the right questions, uncovering creative solutions, and taking action. And that will make you a highly valuable thinker in any organization or team.

Let’s boost your self-growth with Believe in Mind.

Interested in self-reflection tips, learning hacks, and knowing ways to calm down your mind? We offer you the best content which you have been looking for.

Follow Me on

You May Like Also

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

7 Problem-Solving Skills That Can Help You Be a More Successful Manager

Discover what problem-solving is, and why it's important for managers. Understand the steps of the process and learn about seven problem-solving skills.

![attitude to problem solving [Featured Image]: A manager wearing a black suit is talking to a team member, handling an issue utilizing the process of problem-solving](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/6uiffmHlG1nCAhji06VPaV/06ef7be91702ee158c66d2caeae98607/iStock-1176251115__2_.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

1Managers oversee the day-to-day operations of a particular department, and sometimes a whole company, using their problem-solving skills regularly. Managers with good problem-solving skills can help ensure companies run smoothly and prosper.

If you're a current manager or are striving to become one, read this guide to discover what problem-solving skills are and why it's important for managers to have them. Learn the steps of the problem-solving process, and explore seven skills that can help make problem-solving easier and more effective.

What is problem-solving?

Problem-solving is both an ability and a process. As an ability, problem-solving can aid in resolving issues faced in different environments like home, school, abroad, and social situations, among others. As a process, problem-solving involves a series of steps for finding solutions to questions or concerns that arise throughout life.

The importance of problem-solving for managers

Managers deal with problems regularly, whether supervising a staff of two or 100. When people solve problems quickly and effectively, workplaces can benefit in a number of ways. These include:

Greater creativity

Higher productivity

Increased job fulfillment

Satisfied clients or customers

Better cooperation and cohesion

Improved environments for employees and customers

7 skills that make problem-solving easier

Companies depend on managers who can solve problems adeptly. Although problem-solving is a skill in its own right, a subset of seven skills can help make the process of problem-solving easier. These include analysis, communication, emotional intelligence, resilience, creativity, adaptability, and teamwork.

1. Analysis

As a manager , you'll solve each problem by assessing the situation first. Then, you’ll use analytical skills to distinguish between ineffective and effective solutions.

2. Communication

Effective communication plays a significant role in problem-solving, particularly when others are involved. Some skills that can help enhance communication at work include active listening, speaking with an even tone and volume, and supporting verbal information with written communication.

3. Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is the ability to recognize and manage emotions in any situation. People with emotional intelligence usually solve problems calmly and systematically, which often yields better results.

4. Resilience

Emotional intelligence and resilience are closely related traits. Resiliency is the ability to cope with and bounce back quickly from difficult situations. Those who possess resilience are often capable of accurately interpreting people and situations, which can be incredibly advantageous when difficulties arise.

5. Creativity

When brainstorming solutions to problems, creativity can help you to think outside the box. Problem-solving strategies can be enhanced with the application of creative techniques. You can use creativity to:

Approach problems from different angles

Improve your problem-solving process

Spark creativity in your employees and peers

6. Adaptability

Adaptability is the capacity to adjust to change. When a particular solution to an issue doesn't work, an adaptable person can revisit the concern to think up another one without getting frustrated.

7. Teamwork

Finding a solution to a problem regularly involves working in a team. Good teamwork requires being comfortable working with others and collaborating with them, which can result in better problem-solving overall.

Steps of the problem-solving process

Effective problem-solving involves five essential steps. One way to remember them is through the IDEAL model created in 1984 by psychology professors John D. Bransford and Barry S. Stein [ 1 ]. The steps to solving problems in this model include: identifying that there is a problem, defining the goals you hope to achieve, exploring potential solutions, choosing a solution and acting on it, and looking at (or evaluating) the outcome.

1. Identify that there is a problem and root out its cause.

To solve a problem, you must first admit that one exists to then find its root cause. Finding the cause of the problem may involve asking questions like:

Can the problem be solved?

How big of a problem is it?

Why do I think the problem is occurring?

What are some things I know about the situation?

What are some things I don't know about the situation?

Are there any people who contributed to the problem?

Are there materials or processes that contributed to the problem?

Are there any patterns I can identify?

2. Define the goals you hope to achieve.

Every problem is different. The goals you hope to achieve when problem-solving depend on the scope of the problem. Some examples of goals you might set include:

Gather as much factual information as possible.

Brainstorm many different strategies to come up with the best one.

Be flexible when considering other viewpoints.

Articulate clearly and encourage questions, so everyone involved is on the same page.

Be open to other strategies if the chosen strategy doesn't work.

Stay positive throughout the process.

3. Explore potential solutions.

Once you've defined the goals you hope to achieve when problem-solving , it's time to start the process. This involves steps that often include fact-finding, brainstorming, prioritizing solutions, and assessing the cost of top solutions in terms of time, labor, and money.

4. Choose a solution and act on it.

Evaluate the pros and cons of each potential solution, and choose the one most likely to solve the problem within your given budget, abilities, and resources. Once you choose a solution, it's important to make a commitment and see it through. Draw up a plan of action for implementation, and share it with all involved parties clearly and effectively, both verbally and in writing. Make sure everyone understands their role for a successful conclusion.

5. Look at (or evaluate) the outcome.

Evaluation offers insights into your current situation and future problem-solving. When evaluating the outcome, ask yourself questions like:

Did the solution work?

Will this solution work for other problems?

Were there any changes you would have made?

Would another solution have worked better?

As a current or future manager looking to build your problem-solving skills, it is often helpful to take a professional course. Consider Improving Communication Skills offered by the University of Pennsylvania on Coursera. You'll learn how to boost your ability to persuade, ask questions, negotiate, apologize, and more.

You might also consider taking Emotional Intelligence: Cultivating Immensely Human Interactions , offered by the University of Michigan on Coursera. You'll explore the interpersonal and intrapersonal skills common to people with emotional intelligence, and you'll learn how emotional intelligence is connected to team success and leadership.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Article sources

Tennessee Tech. “ The Ideal Problem Solver (2nd ed.) , https://www.tntech.edu/cat/pdf/useful_links/idealproblemsolver.pdf.” Accessed December 6, 2022.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Problem-Solving Strategies and Obstacles

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

JGI / Jamie Grill / Getty Images

- Application

- Improvement

From deciding what to eat for dinner to considering whether it's the right time to buy a house, problem-solving is a large part of our daily lives. Learn some of the problem-solving strategies that exist and how to use them in real life, along with ways to overcome obstacles that are making it harder to resolve the issues you face.

What Is Problem-Solving?

In cognitive psychology , the term 'problem-solving' refers to the mental process that people go through to discover, analyze, and solve problems.

A problem exists when there is a goal that we want to achieve but the process by which we will achieve it is not obvious to us. Put another way, there is something that we want to occur in our life, yet we are not immediately certain how to make it happen.

Maybe you want a better relationship with your spouse or another family member but you're not sure how to improve it. Or you want to start a business but are unsure what steps to take. Problem-solving helps you figure out how to achieve these desires.

The problem-solving process involves:

- Discovery of the problem

- Deciding to tackle the issue

- Seeking to understand the problem more fully

- Researching available options or solutions

- Taking action to resolve the issue

Before problem-solving can occur, it is important to first understand the exact nature of the problem itself. If your understanding of the issue is faulty, your attempts to resolve it will also be incorrect or flawed.

Problem-Solving Mental Processes

Several mental processes are at work during problem-solving. Among them are:

- Perceptually recognizing the problem

- Representing the problem in memory

- Considering relevant information that applies to the problem

- Identifying different aspects of the problem

- Labeling and describing the problem

Problem-Solving Strategies

There are many ways to go about solving a problem. Some of these strategies might be used on their own, or you may decide to employ multiple approaches when working to figure out and fix a problem.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that, by following certain "rules" produces a solution. Algorithms are commonly used in mathematics to solve division or multiplication problems. But they can be used in other fields as well.

In psychology, algorithms can be used to help identify individuals with a greater risk of mental health issues. For instance, research suggests that certain algorithms might help us recognize children with an elevated risk of suicide or self-harm.

One benefit of algorithms is that they guarantee an accurate answer. However, they aren't always the best approach to problem-solving, in part because detecting patterns can be incredibly time-consuming.

There are also concerns when machine learning is involved—also known as artificial intelligence (AI)—such as whether they can accurately predict human behaviors.

Heuristics are shortcut strategies that people can use to solve a problem at hand. These "rule of thumb" approaches allow you to simplify complex problems, reducing the total number of possible solutions to a more manageable set.

If you find yourself sitting in a traffic jam, for example, you may quickly consider other routes, taking one to get moving once again. When shopping for a new car, you might think back to a prior experience when negotiating got you a lower price, then employ the same tactics.

While heuristics may be helpful when facing smaller issues, major decisions shouldn't necessarily be made using a shortcut approach. Heuristics also don't guarantee an effective solution, such as when trying to drive around a traffic jam only to find yourself on an equally crowded route.

Trial and Error

A trial-and-error approach to problem-solving involves trying a number of potential solutions to a particular issue, then ruling out those that do not work. If you're not sure whether to buy a shirt in blue or green, for instance, you may try on each before deciding which one to purchase.

This can be a good strategy to use if you have a limited number of solutions available. But if there are many different choices available, narrowing down the possible options using another problem-solving technique can be helpful before attempting trial and error.

In some cases, the solution to a problem can appear as a sudden insight. You are facing an issue in a relationship or your career when, out of nowhere, the solution appears in your mind and you know exactly what to do.

Insight can occur when the problem in front of you is similar to an issue that you've dealt with in the past. Although, you may not recognize what is occurring since the underlying mental processes that lead to insight often happen outside of conscious awareness .

Research indicates that insight is most likely to occur during times when you are alone—such as when going on a walk by yourself, when you're in the shower, or when lying in bed after waking up.

How to Apply Problem-Solving Strategies in Real Life

If you're facing a problem, you can implement one or more of these strategies to find a potential solution. Here's how to use them in real life:

- Create a flow chart . If you have time, you can take advantage of the algorithm approach to problem-solving by sitting down and making a flow chart of each potential solution, its consequences, and what happens next.

- Recall your past experiences . When a problem needs to be solved fairly quickly, heuristics may be a better approach. Think back to when you faced a similar issue, then use your knowledge and experience to choose the best option possible.

- Start trying potential solutions . If your options are limited, start trying them one by one to see which solution is best for achieving your desired goal. If a particular solution doesn't work, move on to the next.

- Take some time alone . Since insight is often achieved when you're alone, carve out time to be by yourself for a while. The answer to your problem may come to you, seemingly out of the blue, if you spend some time away from others.

Obstacles to Problem-Solving

Problem-solving is not a flawless process as there are a number of obstacles that can interfere with our ability to solve a problem quickly and efficiently. These obstacles include:

- Assumptions: When dealing with a problem, people can make assumptions about the constraints and obstacles that prevent certain solutions. Thus, they may not even try some potential options.

- Functional fixedness : This term refers to the tendency to view problems only in their customary manner. Functional fixedness prevents people from fully seeing all of the different options that might be available to find a solution.

- Irrelevant or misleading information: When trying to solve a problem, it's important to distinguish between information that is relevant to the issue and irrelevant data that can lead to faulty solutions. The more complex the problem, the easier it is to focus on misleading or irrelevant information.

- Mental set: A mental set is a tendency to only use solutions that have worked in the past rather than looking for alternative ideas. A mental set can work as a heuristic, making it a useful problem-solving tool. However, mental sets can also lead to inflexibility, making it more difficult to find effective solutions.

How to Improve Your Problem-Solving Skills

In the end, if your goal is to become a better problem-solver, it's helpful to remember that this is a process. Thus, if you want to improve your problem-solving skills, following these steps can help lead you to your solution:

- Recognize that a problem exists . If you are facing a problem, there are generally signs. For instance, if you have a mental illness , you may experience excessive fear or sadness, mood changes, and changes in sleeping or eating habits. Recognizing these signs can help you realize that an issue exists.

- Decide to solve the problem . Make a conscious decision to solve the issue at hand. Commit to yourself that you will go through the steps necessary to find a solution.

- Seek to fully understand the issue . Analyze the problem you face, looking at it from all sides. If your problem is relationship-related, for instance, ask yourself how the other person may be interpreting the issue. You might also consider how your actions might be contributing to the situation.

- Research potential options . Using the problem-solving strategies mentioned, research potential solutions. Make a list of options, then consider each one individually. What are some pros and cons of taking the available routes? What would you need to do to make them happen?

- Take action . Select the best solution possible and take action. Action is one of the steps required for change . So, go through the motions needed to resolve the issue.

- Try another option, if needed . If the solution you chose didn't work, don't give up. Either go through the problem-solving process again or simply try another option.

You can find a way to solve your problems as long as you keep working toward this goal—even if the best solution is simply to let go because no other good solution exists.

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

Dunbar K. Problem solving . A Companion to Cognitive Science . 2017. doi:10.1002/9781405164535.ch20

Stewart SL, Celebre A, Hirdes JP, Poss JW. Risk of suicide and self-harm in kids: The development of an algorithm to identify high-risk individuals within the children's mental health system . Child Psychiat Human Develop . 2020;51:913-924. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-00968-9

Rosenbusch H, Soldner F, Evans AM, Zeelenberg M. Supervised machine learning methods in psychology: A practical introduction with annotated R code . Soc Personal Psychol Compass . 2021;15(2):e12579. doi:10.1111/spc3.12579

Mishra S. Decision-making under risk: Integrating perspectives from biology, economics, and psychology . Personal Soc Psychol Rev . 2014;18(3):280-307. doi:10.1177/1088868314530517

Csikszentmihalyi M, Sawyer K. Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment . In: The Systems Model of Creativity . 2015:73-98. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9085-7_7

Chrysikou EG, Motyka K, Nigro C, Yang SI, Thompson-Schill SL. Functional fixedness in creative thinking tasks depends on stimulus modality . Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts . 2016;10(4):425‐435. doi:10.1037/aca0000050

Huang F, Tang S, Hu Z. Unconditional perseveration of the short-term mental set in chunk decomposition . Front Psychol . 2018;9:2568. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02568

National Alliance on Mental Illness. Warning signs and symptoms .

Mayer RE. Thinking, problem solving, cognition, 2nd ed .

Schooler JW, Ohlsson S, Brooks K. Thoughts beyond words: When language overshadows insight. J Experiment Psychol: General . 1993;122:166-183. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.2.166

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

6 Steps To Develop A Problem-Solving Mindset That Boosts Productivity

Problem-controlled approach vs. problem-solving approach, benefits of a problem-solving mindset, 6 steps to develop a problem-solving mindset, characteristics of a manager with a problem-solving mindset, problem-solving mindset examples for managers, frequently asked questions.

Other Related Blogs

What is a problem-solving mindset?

- Better decision-making: A problem-solving mindset helps managers analyze problems more effectively and generate various possible solutions. This leads to more informed decision-making , which is critical for effective leadership.

- Improved productivity: By addressing problems proactively, managers can prevent potential obstacles from becoming major issues that impact productivity . A problem-solving mindset can help managers to anticipate and prevent problems before they occur, leading to smoother operations and higher productivity.

- Enhanced teamwork: Encouraging a problem-solving mindset among team members fosters a culture of collaboration and encourages open communication. This can lead to stronger teamwork , as team members are more likely to work together to identify and solve problems.

- Improved morale: When managers take a proactive approach to problem-solving, they demonstrate their commitment to their team’s success. This can improve morale and build trust and respect between managers and team members.

- Better outcomes: Ultimately, a problem solving mindset leads to better outcomes. By effectively identifying and addressing problems, managers can improve processes, reduce costs, and enhance overall performance.

- Acknowledge the issue: Instead of avoiding or dismissing the problem, the first step in adopting a problem-solving mindset is to embrace it. Accept the problem and commit to trying to find a solution.

- Focus on the solutions: Shift your attention from the problem to the solution by concentrating on it. Then, work towards the result by visualizing it.

- Come up with all possible solutions: Create a list of all potential answers, even those that appear unusual or out of the ordinary. Avoid dismissing ideas prematurely and encourage creative thinking.

- Analyze the root cause: After coming up with a list of viable solutions. Finding the fundamental reason enables you to solve the problem and stop it from happening again.

- Take on a new perspective: Sometimes, a new viewpoint might result in game-breakthrough solutions. Consider looking at the problem differently, considering other people’s perspectives, or questioning your presumptions.

- Implement solutions and monitor them: Choose the best course of action, then implement it. Keep an eye on the findings and make changes as needed. Use what you learn from the process to sharpen your problem-solving skills.

- Positive attitude: A problem-solving manager approaches challenges with a positive and proactive mindset, focused on solutions rather than problems.

- Analytical thinking: A problem-solving manager breaks down complex challenges into smaller, more manageable pieces and identifies the underlying causes of difficulties because of their strong analytical skills .

- Creativity: A manager with a problem solving mindset think outside the box to solve difficulties and problems.

- Flexibility: A manager with a problem-solving mindset can change their problem-solving strategy depending on the circumstances. They are receptive to new ideas and other viewpoints.

- Collaboration: A manager who prioritizes problem-solving understands the value of collaboration and teamwork. They value team members’ feedback and are skilled at bringing diverse perspectives together to develop creative solutions.

- Strategic thinking: A problem-solving manager thinks strategically , considering the long-term consequences of their decisions and solutions. They can balance short-term fixes with long-term objectives.

- Continuous improvement: A problem-solving manager is dedicated to continuous improvement, always looking for new ways to learn and improve their problem-solving skills. They use feedback and analysis to improve their approach and achieve better results.

- Top 8 ways to make the best use of an Employee Assistance Program

- Navigating Growth: An In-Depth Example of a Learning and Development Strategy

- 5 Ways To Master Emotional Management At Work For Managers

- Essential Guide to Effective Leadership Coaching

- Top 10 Soft Skills for IT Professionals: Boost Your Career Success

- Training for Conflict Management Made Easy for Managers 5 Easy Steps

- How to develop a culture of creativity at work?

- The Ultimate Guide to Intuitive Decision Making for Managers

- Team Learning: How To Promote Successful Collaborations

- 6 Effective Employee Development Ideas For Managers

- A manager listens actively to a team member’s concerns and identifies the root cause of a problem before brainstorming potential solutions.

- A manager encourages team members to collaborate and share ideas to solve a challenging problem.

- A manager takes a proactive approach to address potential obstacles, anticipating challenges and taking steps to prevent them from becoming major issues.

- A manager analyzes data and feedback to identify patterns and insights that can inform more effective problem-solving.

- A manager uses various tools and techniques, such as brainstorming , SWOT analysis, or root cause analysis, to identify and address problems.

- To inform about problem-solving, a manager seeks input and feedback from various sources, including team members, stakeholders, and subject matter experts.

- A manager encourages experimentation and risk-taking, fostering a culture of innovation and creativity.

- A manager takes ownership of problems rather than blaming others or deflecting responsibility.

- A manager is willing to admit mistakes and learn from failures rather than become defensive or dismissive.

- A manager focuses on finding solutions rather than dwelling on problems or obstacles.

- A manager can adapt and pivot as needed, being flexible and responsive to changing circumstances or new information.

Suprabha Sharma

Suprabha, a versatile professional who blends expertise in human resources and psychology, bridges the divide between people management and personal growth with her novel perspectives at Risely. Her experience as a human resource professional has empowered her to visualize practical solutions for frequent managerial challenges that form the pivot of her writings.

Are your problem solving skills sharp enough to help you succeed?

Find out now with the help of Risely’s problem-solving assessment for managers and team leaders.

Do I have a problem-solving mindset?

What is a growth mindset for problem-solving , what is problem mindset vs. solution mindset , what is a problem-solving attitude.

Top 15 Tips for Effective Conflict Mediation at Work

Top 10 games for negotiation skills to make you a better leader, manager effectiveness: a complete guide for managers in 2024, 5 proven ways managers can build collaboration in a team.

What is Problem Solving? (Steps, Techniques, Examples)

By Status.net Editorial Team on May 7, 2023 — 5 minutes to read

What Is Problem Solving?

Definition and importance.

Problem solving is the process of finding solutions to obstacles or challenges you encounter in your life or work. It is a crucial skill that allows you to tackle complex situations, adapt to changes, and overcome difficulties with ease. Mastering this ability will contribute to both your personal and professional growth, leading to more successful outcomes and better decision-making.

Problem-Solving Steps

The problem-solving process typically includes the following steps:

- Identify the issue : Recognize the problem that needs to be solved.

- Analyze the situation : Examine the issue in depth, gather all relevant information, and consider any limitations or constraints that may be present.

- Generate potential solutions : Brainstorm a list of possible solutions to the issue, without immediately judging or evaluating them.

- Evaluate options : Weigh the pros and cons of each potential solution, considering factors such as feasibility, effectiveness, and potential risks.

- Select the best solution : Choose the option that best addresses the problem and aligns with your objectives.

- Implement the solution : Put the selected solution into action and monitor the results to ensure it resolves the issue.

- Review and learn : Reflect on the problem-solving process, identify any improvements or adjustments that can be made, and apply these learnings to future situations.

Defining the Problem

To start tackling a problem, first, identify and understand it. Analyzing the issue thoroughly helps to clarify its scope and nature. Ask questions to gather information and consider the problem from various angles. Some strategies to define the problem include:

- Brainstorming with others

- Asking the 5 Ws and 1 H (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How)

- Analyzing cause and effect

- Creating a problem statement

Generating Solutions

Once the problem is clearly understood, brainstorm possible solutions. Think creatively and keep an open mind, as well as considering lessons from past experiences. Consider:

- Creating a list of potential ideas to solve the problem

- Grouping and categorizing similar solutions

- Prioritizing potential solutions based on feasibility, cost, and resources required

- Involving others to share diverse opinions and inputs

Evaluating and Selecting Solutions

Evaluate each potential solution, weighing its pros and cons. To facilitate decision-making, use techniques such as:

- SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats)

- Decision-making matrices

- Pros and cons lists

- Risk assessments

After evaluating, choose the most suitable solution based on effectiveness, cost, and time constraints.

Implementing and Monitoring the Solution

Implement the chosen solution and monitor its progress. Key actions include:

- Communicating the solution to relevant parties

- Setting timelines and milestones

- Assigning tasks and responsibilities

- Monitoring the solution and making adjustments as necessary

- Evaluating the effectiveness of the solution after implementation

Utilize feedback from stakeholders and consider potential improvements. Remember that problem-solving is an ongoing process that can always be refined and enhanced.

Problem-Solving Techniques

During each step, you may find it helpful to utilize various problem-solving techniques, such as:

- Brainstorming : A free-flowing, open-minded session where ideas are generated and listed without judgment, to encourage creativity and innovative thinking.

- Root cause analysis : A method that explores the underlying causes of a problem to find the most effective solution rather than addressing superficial symptoms.

- SWOT analysis : A tool used to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats related to a problem or decision, providing a comprehensive view of the situation.