The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

How to Write a Poem: In 7 Practical Steps with Examples

Learn how to write a poem through seven easy to follow steps that will guide you through writing completed poem. Ignite a passion for poetry!

This article is a practical guide for writing a poem, and the purpose is to help you write a poem! By completing the seven steps below, you will create the first draft of a simple poem. You can go on to refine your poetry in any way you like. The important thing is that you’ve got a poem under your belt.

At the bottom of the post, I’ll provide more resources on writing poetry. I encourage you to explore different forms and structures and continue writing poetry on your own. Hopefully, writing a poem will spark, in you, a passion for creative writing and language.

Let’s get started with writing a poem in seven simple steps:

- Brainstorm & Free-write

- Develop a theme

- Create an extended metaphor

- Add figurative language

- Plan your structure

- Write your first draft

- Read, re-read & edit

Now we’ll go into each step in-depth. And, if your feeling up to it, you can plan and write your poem as we go.

Step 1: Brainstorm and Free-write

Find what you want to write about

Before you begin writing, you need to choose a subject to write about. For our purposes, you’ll want to select a specific topic. Later, you’ll be drawing a comparison between this subject and something else.

When choosing a subject, you’ll want to write about something you feel passionately about. Your topic can be something you love, like a person, place, or thing. A subject can also be something you struggle with . Don’t get bogged down by all the options; pick something. Poets have written about topics like:

And of course… cats

Once you have your subject in mind, you’re going to begin freewriting about that subject. Let’s say you picked your pet iguana as your subject. Get out a sheet of paper or open a word processor. Start writing everything that comes to mind about that subject. You could write about your iguana’s name, the color of their skin, the texture of their scales, how they make you feel, a metaphor that comes to mind. Nothing is off-limits.

Write anything that comes to mind about your subject. Keep writing until you’ve entirely exhausted everything you have to say about the subject. Or, set a timer for several minutes and write until it goes off. Don’t worry about things like spelling, grammar, form, or structure. For now, you want to get all your thoughts down on paper.

ACTION STEPS:

- Grab a scratch paper, or open a word processor

- Pick a subject- something you’re passionate about

- Write everything that comes to mind about your topic without editing or structuring your writing

- Make sure this free-writing is uninterrupted

- Optional- set a timer and write continuously for 5 or 10 minutes about your subject

Step 2: Develop a Theme

What lesson do you want to teach?

Poetry often has a theme or a message the poet would like to convey to the reader. Developing a theme will give your writing purpose and focus your effort. Look back at your freewriting and see if a theme, or lesson, has developed naturally, one that you can refine.

Maybe, in writing about your iguana, you noticed that you talked about your love for animals and the need to preserve the environment. Or, perhaps you talk about how to care for a reptile pet. Your theme does not need to be groundbreaking. A theme only needs to be a message that you would like to convey.

Now, what is your theme? Finish the following statement:

The lesson I want to teach my readers about (your subject) is ______

Ex. I want to teach my readers that spring days are lovely and best enjoyed with loving companions or family.

- Read over the product of your free-writing exercise.

- Brainstorm a lesson you would like to teach readers about your subject.

- Decide on one thing that is essential for your reader to know about your topic.

- Finish the sentence stem above.

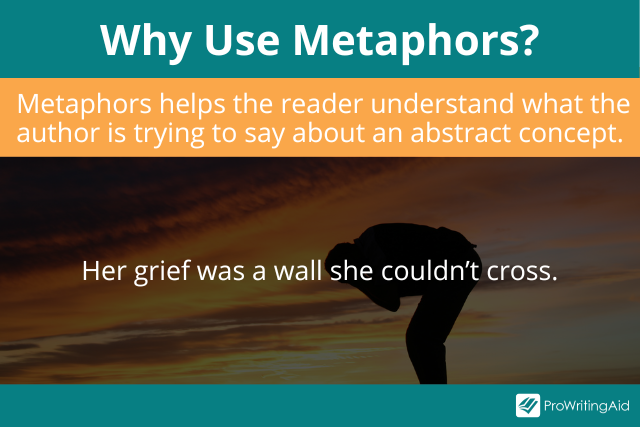

Step 3: Create an (extended) Metaphor

Compare your subject to another, unlike thing.

To write this poem, you will compare your subject to something it, seemingly, has nothing in common with. When you directly compare two, unlike things, you’re using a form of figurative language called a metaphor. But, we’re going to take this metaphor and extend it over one or two stanzas- Stanzas are like paragraphs, a block of text in a poem- Doing this will create an extended metaphor.

Using a metaphor will reinforce your theme by making your poem memorable for your reader. Keep that in mind when you’re choosing the thing you’d like to compare your subject to. Suppose your topic is pet iguanas, and your theme is that they make fantastic pets. In that case, you’ll want to compare iguanas to something positive. Maybe you compare them to sunshine or a calm lake. This metaphor does the work or conveying your poem’s central message.

- Identify something that is, seemingly, unlike your subject that you’ll use to compare.

- On a piece of paper, make two lists or a Venn diagram.

- Write down all the ways that you’re subject and the thing you’ll compare it to are alike.

- Also, write down all the ways they are unalike.

- Try and make both lists as comprehensive as possible.

Step 4: Add more Figurative Language

Make your writing sound poetic.

Figurative language is a blanket term that describes several techniques used to impart meaning through words. Figurative language is usually colorful and evocative. We’ve talked about one form of figurative language already- metaphor and extended metaphor. But, here are a few others you can choose from.

This list is, by no means, a comprehensive one. There are many other forms of figurative language for you to research. I’ll link a resource at the bottom of this page.

Five types of figurative language:

- Ex. Frank was as giddy as a schoolgirl to find a twenty-dollar bill in his pocket.

- Frank’s car engine whined with exhaustion as he drove up the hill.

- Frank was so hungry he could eat an entire horse.

- Nearing the age of eighty-five, Frank felt as old as Methuselah.

- Frank fretted as he frantically searched his forlorn apartment for a missing Ficus tree.

There are many other types of figurative language, but those are a few common ones. Pick two of the five I’ve listed to include in your poem. Use more if you like, but you only need two for your current poem.

- Choose two of the types of figurative language listed above

- Brainstorm ways they can fit into a poem

- Create example sentences for the two forms of figurative language you chose

Step 5: Plan your Structure

How do you want your poem to sound and look?

If you want to start quickly, then you can choose to write a free-verse poem. Free verse poems are poems that have no rhyme scheme, meter, or structure. In a free verse poem, you’re free to write unrestricted. If you’d like to explore free verse poetry, you can read my article on how to write a prose poem, which is a type of free verse poem.

Read more about prose poetry here.

However, some people enjoy the support of structure and rules. So, let’s talk about a few of the tools you can use to add a form to your poem.

Tools to create poetic structure:

Rhyme Scheme – rhyme scheme refers to the pattern of rhymes used in a poem. The sound at the end of each line determines the rhyme scheme. Writers label words with letters to signify rhyming terms, and this is how rhyme schemes are defined.

If you had a four-line poem that followed an ABAB scheme, then lines 1 and 3 would rhyme, and lines 2 and 4 would rhyme. Here’s an example of an ABAB rhyme scheme from an excerpt of Robert Frost’s poem, Neither Out Far Nor In Deep:

‘The people along the sand (A)

All turn and look one way. (B)

They turn their back on the land. (A)

They look at the sea all day. (B)

Check out the Rhyme Zone.com if you need help coming up with a rhyme!

Read more about the ins and outs of rhyme scheme here.

Meter – a little more advanced than rhyme scheme, meter deals with a poem’s rhythm expressed through stressed and unstressed syllables. Meter can get pretty complicated ,

Check out this article if you’d like to learn more about it.

Stanza – a stanza is a group of lines placed together as a single unit in a poem. A stanza is to a poem what a paragraph is to prose writing. Stanzas don’t have to be the same number of lines throughout a poem, either. They can vary as paragraphs do.

Line Breaks – these are the breaks between stanzas in a poem. They help to create rhythm and set stanzas apart from one another.

- Decide if you want to write a structured poem or use free verse

- Brainstorm rhyming words that could fit into a simple scheme

- Plan out your stanzas and line breaks (small stanzas help emphasize important lines in your poem)

Step 6: Write Your Poem

Combine your figurative language, extended metaphor, and structure.

Poetry is always unique to the writer. And, when it comes to poetry, the “rules” are flexible. In 1965 a young poet named Aram Saroyan wrote a poem called lighght. It goes like this-

That’s it. Saroyan was paid $750 for his poem. You may or may not believe that’s poetry, but a lot of people accept it as just that. My point is, write the poem that comes to you. I won’t give you a strict set of guidelines to follow when creating your poetry. But, here are a few things to consider that might help guide you:

- Compare your subject to something else by creating an extended metaphor

- Try to relate a theme or a simple lesson for your reader

- Use at least two of the figurative language techniques from above

- Create a meter or rhyme scheme (if you’re up to it)

- Write at least two stanzas and use a line break

Still, need some help? Here are two well-known poems that are classic examples of an extended metaphor. Read over them, determine what two, unlike things, are being compared, and for what purpose? What theme is the poet trying to convey? What techniques can you steal? (it’s the sincerest form of flattery)

“Hope” is a thing with feathers by Emily Dickenson.

“The Rose that Grew From Concrete” by Tupac Shakur.

- Write the first draft of your poem.

- Don’t stress. Just get the poem on paper.

Step 7: Read, Re-read, Edit

Read your poem, and edit for clarity and focus .

When you’re finished, read over your poem. Do this out loud to get a feel for the poem’s rhythm. Have a friend or peer read your poem, edit for grammar and spelling. You can also stretch grammar rules, but do it with a purpose.

You can also ask your editor what they think the theme is to determine if you’ve communicated it well enough.

Now you can rewrite your poem. And, remember, all writing is rewriting. This editing process will longer than it did to write your first draft.

- Re-read your poem out loud.

- Find a trusted friend to read over your poem.

- Be open to critique, new ideas, and unique perspectives.

- Edit for mistakes or style.

Use this image on your blog, Google classroom, or Canvas page by right-clicking for the embed code. Look for this </> symbol to embed the image on your page.

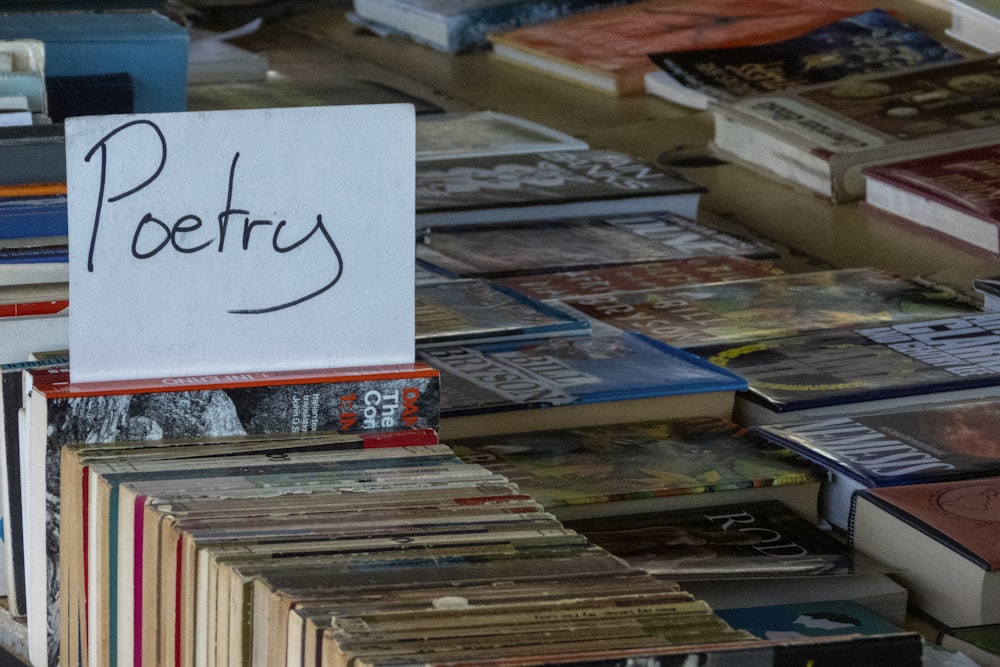

Continued reading on Poetry

A Poetry Handbook

“With passion, wit, and good common sense, the celebrated poet Mary Oliver tells of the basic ways a poem is built—meter and rhyme, form and diction, sound and sense. She talks of iambs and trochees, couplets and sonnets, and how and why this should matter to anyone writing or reading poetry.”

Masterclass.com- Poetry 101: What is Meter?

Poetry Foundation- You Call That Poetry?!

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links

Published by John

View all posts by John

6 comments on “How to Write a Poem: In 7 Practical Steps with Examples”

- Pingback: Haiku Format: How to write a haiku in three steps - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: How to Write a List Poem: A Step by Step Guide - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: How to Write an Acrostic Poem: Tips & Examples - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: List of 10+ how to write a good poem

No problem!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Flashes Safe Seven

- FlashLine Login

- Faculty & Staff Phone Directory

- Emeriti or Retiree

- All Departments

- Maps & Directions

- Building Guide

- Departments

- Directions & Parking

- Faculty & Staff

- Give to University Libraries

- Library Instructional Spaces

- Mission & Vision

- Newsletters

- Circulation

- Course Reserves / Core Textbooks

- Equipment for Checkout

- Interlibrary Loan

- Library Instruction

- Library Tutorials

- My Library Account

- Open Access Kent State

- Research Support Services

- Statistical Consulting

- Student Multimedia Studio

- Citation Tools

- Databases A-to-Z

- Databases By Subject

- Digital Collections

- Discovery@Kent State

- Government Information

- Journal Finder

- Library Guides

- Connect from Off-Campus

- Library Workshops

- Subject Librarians Directory

- Suggestions/Feedback

- Writing Commons

- Academic Integrity

- Jobs for Students

- International Students

- Meet with a Librarian

- Study Spaces

- University Libraries Student Scholarship

- Affordable Course Materials

- Copyright Services

- Selection Manager

- Suggest a Purchase

Library Locations at the Kent Campus

- Architecture Library

- Fashion Library

- Map Library

- Performing Arts Library

- Special Collections and Archives

Regional Campus Libraries

- East Liverpool

- College of Podiatric Medicine

Creative Writing: Poetry: Stanza & Rhyme

- Introduction

- Lineation & Syntax

- Rhetoric & Mode

- Meter & Prosody

- Stanza & Rhyme

- Analysis, Criticism & Reference

A group of three or more lines, usually with a fixed rhyme scheme, which is repeated more than once. Stanzas are used additively, unlike a one-time pattern of rhymed lines such as the sonnet, which is complete in fourteen lines (Kinzie, 1999).

The agreement of two metrically accented syllables and their terminal consonants. Rhymes can be either subtle (overshadowed by syntax) or definite (Kinzie, 1999).

Resources for Stanza & Rhyme

- << Previous: Meter & Prosody

- Next: Analysis, Criticism & Reference >>

- Last Updated: Jul 6, 2022 2:22 PM

- URL: https://libguides.library.kent.edu/c.php?g=278016

Street Address

Mailing address, quick links.

- How Are We Doing?

- Student Jobs

Information

- Accessibility

- Emergency Information

- For Our Alumni

- For the Media

- Jobs & Employment

- Life at KSU

- Privacy Statement

- Technology Support

- Website Feedback

- How to write a story

- How to write a novel

- How to write poetry

- Dramatic writing

- How to write a memoir

- How to write a mystery

- Creative journaling

- Publishing advice

- Story starters

- Poetry prompts

- For teachers

How to Write a Poem - Poetry Techniques 2

Poetry techniques - expressing the invisible, poetry techniques - meaning and form, poetry techniques - writing and rewriting.

- Are there words that don't seem quite right for what they're describing? Are there words that don't serve a purpose? If you can remove something without hurting the poem, it's usually a good idea to remove it.

- Is there anything there that doesn't feel genuine, that's only there because it seems "poetic," to impress the reader? Remove or replace anything that is just "showing off."

- Are there parts of the poem that you like better than others? Are there parts you should delete? Are there parts that don't quite fit, that should be cut out or integrated better? Is there a particularly interesting part that might suggest taking the poem in a new direction?

Poetry techniques - keep reading

- Click here for "Poetry Techniques - Lines and Stanza."

- Click here for "Poetry Techniques - Meter."

- Click here for "Poetry Techniques - Rhyme."

- Click here for a list of CWN poetry pages

© 2009-2024 William Victor, S.L., All Rights Reserved.

Terms - Returns & Cancellations - Affiliate Disclosure - Privacy Policy

How To Write A Poem: Comprehensive Guide For Beginners

Tips on how to write a poem.

Ever wondered how to write a poem but felt overwhelmed by where to start?

Crafting a compelling poem often begins with identifying a poignant moment or stirring emotion that resonates.

This guide will walk you through the basics, from choosing your subject to refining your verses, ensuring that poetry doesn’t have to be perplexing for beginners.

Dive in – poetic expression awaits!

Key Takeaways

- Start by picking a topic that touches your heart, then play with words and sounds to express it.

- Use literary devices like similes and metaphors to add depth to your poem.

- Try different forms like sonnets or free verse to find what best suits your message.

- Edit your work by reading aloud and changing words for the strongest impact.

- Join a writing community , seek mentorship from published poets , and keep practicing .

Table of Contents

Understanding the elements of poetry.

Before diving into the creative current of poetry, it’s essential to grasp its foundational elements — these are the building blocks that give your verses structure and depth.

From the subtle dance of assonance to the precise architecture of stanzas, each aspect works in harmony to transform a mere string of words into an evocative literary masterpiece.

Sound in poetry

They use sounds to support their themes and messages.

Rhymes give poems a catchy beat and can make them fun to say out loud. Learning about syllables helps you see patterns in stress and rhythm.

Mastering rhyme boosts your creativity everywhere – not just in writing poems!

Sound devices are your secret tools for making each poem unique and powerful .

Use them wisely to create special effects that stick with the reader long after they’ve finished reading.

Moving beyond sound, we find that rhythm truly breathes life into a poem. It creates a beat, much like the heartbeat of your piece.

Picture rhythm as the drum you tap to while reading your poem out loud—it shapes how fast or slow, smooth or choppy the words flow from one line to another.

Think of stressed and unstressed syllables as the building blocks of rhythm; they help you decide where emphasis falls in each line.

Rhythm can stir emotions and reinforce your message. Use it skillfully to make readers feel the excitement, calmness, or tension with every verse they read.

Consider how sometimes repeating certain sounds at regular intervals can add power to an idea or emotion you want to express.

Mastering this musical element will set your poetry apart, turning simple words into an experience that resonates deeply with those who hear them .

Rhythm sets the beat, but rhyme brings harmony to your poem. A good rhyme can make your lines sing.

Think of it as a pattern where sounds match at the end of each line or in the middle.

These matching sounds are part of what’s called a “ rhyme scheme .” Poets craft these schemes to give their work structure and flow.

You don’t need every line to rhyme, but when they do, it creates melody and rhythm that stick with readers long after they’ve read your poem.

Explore different types of rhymes, like slant rhymes or eye rhymes , to add variety.

Use rhyme scheme wisely – it guides listeners through your poetry, making each verse memorable. Sound matters in poetry; let’s use it well!

Literary devices

Literary devices are like secret tools poets use to make their writing stand out. Think of them as spices in cooking—they add flavor and depth.

Poets sprinkle these devices throughout their work to stir up emotions and thoughts in the reader’s mind.

For example, similes compare two things using “like” or “as,” making images more vivid.

Metaphors do a similar job but without the comparison words, creating solid connections directly.

Analogies extend those comparisons even further, often across several lines or an entire poem, building complex relationships between ideas.

Sound devices like alliteration repeat consonant sounds at the beginning of words close together—it can make a line hum!

Personification gives human traits to non-human things; it makes everything feel alive and relatable.

Using these literary tools well takes practice. Begin by playing with them in your writing exercises—see how they change your poem’s sound when read out loud or alter its meaning line by line.

Let’s dive into how you can start your journey step-by-step by choosing a topic for your poem next!

Just as literary devices add depth to your words, form gives shape to your poem.

Many types of poetry have specific structures , like a sonnet with its 14 lines and strict rhyme scheme.

Choose a free verse that flows without set rules. Each form comes with its rhythm and flow.

Trying out different poetic forms can be an exciting way to find the one that resonates with you.

Explore traditional forms such as haikus or limericks if you’re looking for clear rules to guide you.

For more freedom, consider a free verse where line breaks and stanza divisions are up to you.

The important thing is how the structure reflects what you want to say—whether it’s controlling pace through quatrains or building intensity with couplets.

Whatever form catches your eye, give it a shot! Experimenting is part of discovering your unique voice in poetry .

How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step

Diving into the world of poetry can be exhilarating yet intimidating, but with a solid step-by-step approach, crafting your verses becomes an attainable adventure.

This section is where creativity meets methodology; it’s about transforming that spark of inspiration into lines that resonate and stir emotions — let’s get those words flowing!

Choosing a topic

Picking a subject for your poem is like choosing the heart of your message. Look for ideas that stir your emotions, things you feel deeply about.

This connection makes your words more powerful and can touch others, too. Use images and experiences from life to bring richness to the theme.

Brainstorming helps you explore different angles of the topic before starting your poem. Jot down single words, phrases, or even feelings related to the idea.

These notes will be valuable in crafting lines that resonate with readers later on.

Think about what kind of poem celebrates or reflects upon these thoughts—this sets the tone for writing something significant.

Consideration of form

Poems come in shapes and sizes. Some are long; others are just a few words.

There’s free verse , which doesn’t follow rules, and then there’s sonnets with 14 lines that often tell about love.

Haikus from Japan have three lines with a pattern of 5, 7, and 5 syllables.

Think about the form before you start writing your poem. Want to share a story? Try a ballad ! They’re like songs telling tales.

Or pick cinquains if you want something short but mighty – they’ve got five lines that paint a vivid picture.

Make sure your choice suits the mood and message of your poem – it helps bring your words to life!

Word exploration

Pick each word carefully, like choosing a color for a painting. Think about how they sound and feel. Some words can make your poem soft or loud, fast or slow.

Play with language to find the perfect match for your ideas.

Look at different words until you find ones that fit just right. Try synonyms to see if they add something new to your lines.

Use strong verbs to give power to what you write and paint clear pictures in the reader’s mind.

Word choice is critical – it can turn a simple message into something beautiful and full of life!

Writing process

Let your ideas flow onto the page without worrying about perfection. Start with brainstorming and free-writing in prose to get your thoughts out.

This technique helps tap into emotions and can spark creativity for your poem. Try to include feelings and consider using nature as an inspiration source.

Once you’ve got a bunch of ideas, shape them into a first draft of your poem. Don’t fret over misspelled words or misplaced commas; write something down!

Exploring different words, rhythms, and rhymes will refine your vision. As you write, pause often to feel the beat of each line —this is where rhythm comes alive.

After finishing this step, you’ll be ready to edit your poem —a crucial part that polishes rough edges and tightens up language.

Now, let’s move on to reshaping with editing .

Once your poem is on paper, it’s time to fine-tune it. Dive into the editing process with fresh eyes and a sharp mind.

Look for lines that could be clearer or stronger. Swap out any weak words for ones that pack more punch.

Listen to how each line sounds; cut out extra words that drag down your rhythm.

Editing is about polishing your work until it shines. Read your poem aloud—does anything sound off? Fix those spots!

Changes might include cutting lines, adding imagery, or playing with the order of words.

Even minor tweaks can make a big difference in how your poem flows and feels to readers.

Keep shaping and refining because every edit gets you closer to a poem you’ll be proud to share!

Different Approaches and Philosophies for Writing Poetry

Exploring the vast landscape of poetry can be as diverse as the poets who pen it—each with a unique approach to uncovering the heart’s musings.

Whether you’re capturing fleeting emotions or painting with words in a stream-of-consciousness style, your philosophy shapes every stanza; it’s about finding that resonance within and letting it ripple through your verses.

Emotion-driven

Poems can make hearts race or bring tears to the eyes. They reach deep into feelings, sometimes in ways that stories and songs cannot touch.

The secret? Poets pour their own emotions onto the page.

When you try your hand at writing poetry with emotion , let your heart lead. Think about what stirs you up inside—joy, anger, sadness—and write it down.

Use words like a painter uses colors; mix and match till they feel just right. You don’t need fancy tricks or rigid rules to convey raw emotions .

If a line of your poem makes you laugh or cry when you read it back, chances are it will move someone else, too.

Poetry isn’t just about form and technique—it’s also writing from the soul for an audience of one or many .

Let each word take its reader on a journey through sensations, guiding them to taste, smell, see, and feel everything you pour into your lines.

Stream of consciousness

Stream of consciousness lets you capture every twist and turn of your thoughts.

This style can feel like a wild river of ideas , jumping from one to another without strict rules. Think of it as a direct line from your brain to the page.

Your readers get to ride the rapids of emotions and images just as they come. This powerful technique is not just for stories or novels; poets use it, too.

It can add depth to your poetry by showing how feelings and thoughts connect in real time. Don’t worry about making perfect sense at first.

Let your mind wander and spill those raw, unedited thoughts onto paper. Use specific words that pop into your head—no matter how strange or disconnected they may seem.

Feel free to mix memories, hopes, fears, and dreams all in one poem. Permit yourself to break traditional poetic structures with this method!

Mindfulness

Mindfulness brings a special touch to poetry writing . As you focus on the present moment , each word flows with purpose and intention.

It’s like using poetry to capture snapshots of life’s experiences.

Whether observing the rustle of leaves or the rush of emotions, mindfulness in writing helps explore personal insights deeply.

Writing mindfully also offers peace and clarity for both the poet and the reader.

A poem becomes more than just words; it transforms into a journey through sights, sounds, and sensations .

Embracing this practice enriches your craft as every line reflects a clear, tranquil state of being.

Use mindfulness to write poetry that speaks from the soul —simple yet profound.

Poem as a camera lens

Shifting our focus from mindfulness, let’s explore how a poem can act like a camera lens.

Just as a lens captures fleeting moments , poetry seizes emotions and ideas in words. A poet’s job is to observe closely and snap verbal pictures of life.

They might zoom in on a single emotion or pan out to catch the sweep of an experience.

Like photographers choose their frame and focus, poets pick every word with care.

They play with light and shadow through poetic devices to bring depth to their work—every stanza crafted for impact, just as photographers compose each shot for maximum effect.

Poets use literary devices skillfully, making sure imagery jumps off the page ; it’s all about creating that vivid picture readers will carry with them long after they’ve finished reading your poem.

Tips for Furthering Your Poetry Writing Journey

As you embark on the path to poetic prowess, delving deeper into your craft through a range of enriching strategies can transform the way you think about and create poetry—discover more, write with passion, and see where your words can take you.

Publishing in literary journals

Getting your poetry published in literary journals is a big step for any poet. Start by exploring different magazines and websites to find the right fit for your work.

Look at what they publish and read their submission guidelines carefully. Please pay attention to whether they want poems about specific topics or themes.

Send your best work to these places after you revise, revise, revise! Please make sure each word in your poem matters before you share it with editors.

They see a lot of submissions, so give them something unique that stands out from the rest.

Remember, rejection is part of the process . Keep trying even if you get no’s at first.

Every poet starts somewhere, and many famous writers faced rejection too before their poems saw print.

Keep writing, keep revising, and stay persistent in sending out your poetry – publication could be just around the corner!

Assembling and publishing a manuscript

Pulling together a poetry manuscript takes time and attention. You’ll want your poems to fit well together, like telling a story or taking readers on a journey through your thoughts and emotions.

Once you’ve selected the poems, arrange them in an order that flows smoothly. Think about how each poem interacts with the next.

Publishing your collection is the next exciting step. Start by researching publishers who are interested in the type of poetry you write.

Make sure to follow their submission guidelines carefully—this can make or break your chance of getting published.

Self-publishing is also an option if you want more control over the process. It lets you design, market, and sell your book on your terms.

Use social media platforms like Instagram to share snippets of your work and grow an audience for it.

Joining a writing community

Now that you’ve put together your manuscript consider taking the next step by joining a writing community .

This move will connect you with other poets who are eager to share their experiences and writing pieces.

Together, you can give and receive feedback , making each poem stronger and more vibrant.

Becoming part of a poetry group offers more than just critiques; it’s a chance to find your tribe .

You’ll be inspired by different styles and techniques that can broaden your poetic horizon.

A community provides support as you voice your work aloud, helping to build confidence in your craft.

Plus, learning from seasoned poets can propel your journey forward as they share insights only gained through practice and dedication.

Seeking guidance from published poets

Talking to published poets opens doors you didn’t know existed. They’ve walked the path and can share shortcuts and pitfalls.

Picture a mentor shedding light on the mysteries of poetry—this could be that poet for you. Their experience is like a treasure map to better writing .

Join a workshop or reach out online , but get their insights! Learn how they craft words into emotion and thought .

Listen closely as they talk about rhythm, sound, and the dance of verses on paper.

Their advice might make your following poem something people want to read again and again.

Continuously practicing and refining your craft.

Keep writing and revising your poem to get better. This will sharpen your skills and help you grow as a poet.

Use every chance to play with words, rhythms, and forms . Try out new styles and tones in your poems.

Share your work with others, too. You’ll learn from their feedback. Join a group where poets talk about writing together.

This is a great way to improve. Always look for ways to write more muscular lines and express ideas more clearly.

Don’t just write; read lots of poetry ! Seeing how different poets use language can open up new ways for you to write a good poem, too.

Learning doesn’t stop, so keep exploring the vast world of poetry with an open mind and heart.

Concluding Thoughts on How To Write A Poem

Now, you’ve got the basics to start your poem! Remember, poems come from your heart.

Share your story , feelings, or ideas in a way that’s true to you . Writing poetry is a journey — one where each word can paint a picture or sing a song.

Write, share, and, most of all, enjoy the magic of creating something only you can make . Your voice matters ; let it shine through your poetry!

FAQs About How To Write A Poem

1. how do i start writing a poem if i’ve never written one before.

To start your poem, let your emotions and ideas lead the way. Read a lot of poetry to find inspiration—listen to music, think about people in your life, or try capturing abstract imagery in words. Just grab a pen and express yourself!

2. What should I do after I write my first draft?

After you write your poem, take a break then read it again. Revise your poem by looking for parts you can improve—maybe make lines rhyme or change the rhythm. Keep tweaking it until it feels just right.

3. Do all poems have to rhyme?

Nope, poetry doesn’t always require rhyming! Poems often use rhythmic patterns or poetic elements without sticking to rules like rhymes—it’s more important that you convey feelings or images as you see fit.

4. Can anyone learn how to write poetry?

Absolutely! Anyone can learn how to write poems with some practice and guidance. Know that writing tips are just starting points—you’re creating art that reflects who you are, so trust your unique voice!

5. How can I get better at writing poems?

To improve at writing poetry—and enjoy poetry even more—join a writing group where you can share and discuss poetry together; also write regularly and don’t be afraid of rewriting parts until they shine!

6. Should I try publishing my poem once it’s done?

Yes—if sharing is what you want! when ready, research places that publish poems like magazines or online platforms; send them out there for others to appreciate the beauty of what you’ve created.

References:

- https://www.matrix.edu.au/beginners-guide-poetry/ultimate-list-of-poetic-techniques

- https://poemanalysis.com/poetry-explained/elements-of-poetry

- https://blog.shurley.com/blog/2018/11/14/poetry-exploring-sound-devices-with-couplets

- https://literacyideas.com/elements-of-poetry

- https://writers.com/how-to-write-a-poem-step-by-step

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/elements-of-poetry-rhymes-sounds.html

- https://blog.daisie.com/understanding-rhyme-a-comprehensive-guide

r. A. bentinck

Bentinck is a bestselling author in Caribbean and Latin American Poetry, he is a multifaceted individual who excels as both an artist and educator.

You May Also Like...

9 Inspirational Ideas For A Poem: Spark Your Imagination Today!

How to Write a Romantic Poem for a Girl: A Simple Step-by-Step Guide

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Creative Writing

6.2 The Poem

You may have encountered poetry in a variety of forms. Although free verse, where the line breaks do not follow any particular pattern, is the most common in contemporary poetry, there are many additional types of poem. One is the sonnet , a rhyming pattern of four-line stanzas with a two-line couplet to finish. Typically, sonnets are written in iambic pentameter : stressed and unstressed syllables following each other in a pattern. From Japan, we have the seventeen-syllable, three-line haiku , often employed to describe a moment in nature. Experimental Canadian poets have even written entire books out of “found” material (other texts that have been adapted by the poet), or, in the case of Christian Bök’s Eunoia , a book divided into chapters in which only one of the vowels is used.

The villanelle is an old poetry form that is popular with contemporary poets. Originating in France, the poem has five stanzas of three lines each, finishing with a four-line stanza. The first and third lines of the first stanza are repeated in each following stanza and used to make up the last two lines of the final stanza.

Beginning poets typically wait for inspiration to begin writing. Poetry is seen as something that describes a special moment, and how can one write about a special moment in an everyday mood?

Although this is one way of looking at poetry, it isn’t always helpful when you’re in the classroom and you’ve been asked to write. You probably don’t feel very inspired!

Thinking about different forms your poem could take, different subjects you could write about that are important to you, or simply freewriting a poem and seeing where it goes can be helpful in getting you started. For instructions on freewriting, review Chapter 2.3 Freewriting .

If you want to write more poetry, simply writing as much of it as you can, in whatever circumstances, is useful practice—as it is with every form of writing.

Review Questions

- Try an acrostic poem. Select a word meaningful to you. Your name is a classic, but there are many other words you could use, including ones describing values or other things you find important. Write the word in capital letters down the left-hand side of your piece of paper, one letter per line. Use each letter to start a line of poetry related to your word.

- Try making a found poem from a text (or texts) you find. Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel, for example, searched old Western novels for mentions of the word “Injun,” which became the basis for his third book of the same name. Don’t forget that your found text could be a set of instructions, an official letter—anything with words.

- Write a poem explaining “Where I’m From.” Each line begins “I’m from” and contains a detail or phrase. (Hint: For ways to make your writing come alive, review Chapter 3.1 Descriptive Paragraphs , which gives you lists of words relating to the five senses and explains how to show, not tell, readers about your subject.)

Points to Consider

- You don’t need to stop with one poem. Your poem can be a jumping-off point for other poems or for other forms of creative writing, such as a short story or piece of creative nonfiction. For ideas of what to write next after “Where I’m From,” for example, see George Ella Lyon’s web page on “Where I’m From” .

- Try rewriting one of your poems in a different format. Can you turn your acrostic poem into a haiku? Are there two phrases in your found poem you can use in a villanelle?

- Find a poem you really like. Study it, and then write a poem of your own. (Hint: To credit your source, write “inspired by,” the poem’s title, and the poet’s name at the top, just under your poem’s title.)

- Trade poems with a classmate. Use the peer review process described in Chapter 7.2 Peer Review to give each other feedback. Revise your poem based on the feedback you received. Do substantial revisions first. As a last step, proofread.

Building Blocks of Academic Writing Copyright © 2020 by Carellin Brooks is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Stanza Definition

What is a stanza? Here’s a quick and simple definition:

A stanza is a group of lines form a smaller unit within a poem. A single stanza is usually set apart from other lines or stanza within a poem by a double line break or a change in indentation.

Some additional key details about stanzas:

- Stanzas provide poets with a way of visually grouping together the ideas in a poem, and of putting space between separate ideas or parts of a poem. Stanzas also help break the poem down into smaller units that are easy to read and understand.

- Stanzas aren't always separated by line breaks. Especially in older or longer poems, stanzas may be differentiated from one another according to where the meter or rhyme scheme change.

- Because stanzas are the basic unit of poetry, they are often compared to paragraphs in prose.

How to Pronounce Stanza

Here's how to pronounce stanza: stan -zuh

Stanzas, Meter, and Rhyme Scheme

Stanzas can have any meter or rhyme scheme , or none at all. However, that way that stanzas work are different in formal verse that has meter and rhyme scheme and free verse that does not.

Stanzas in Formal Verse

In formal verse —that is, poetry with a strict meter and rhyme scheme—a stanza may contain multiple meters and different rhymes. For example, some stanzas alternate between iambic pentameter and iambic tetrameter. However, the general rule about stanzas in formal verse is that their form recurs from stanza to stanza—the words are different in each stanza, but the general metrical pattern and rhyme scheme are usually the same in each stanza.

Here's an example. In this two-stanza poem by Emily Dickinson, the first stanza alternates lines of iambic tetrameter (eight syllables) with lines of iambic trimeter (six syllables), and the rhyme scheme is A B C B . Since this is formal verse, the second stanza should be expected to repeat the same pattern (the same meter and rhyme scheme, but using different rhymes), which it does.

You left me – Sire – two Legacies – A Legacy of Love A Heavenly Father would suffice Had He the offer of – You left me Boundaries of Pain – Capacious as the Sea – Between Eternity and Time – Your Consciousness – and me –

Stanzas in Free Verse

In free verse —or, poetry without meter or rhyme scheme—the stanza is a unit that is defined by meaning or pacing, rather than by meter or rhyme. In other words, a stanza break may be used in free verse to create a pause in the poem, or to signal a shift in the poem's focus. In free verse, unlike in formal verse, stanzas are often irregular throughout the poem, so a poem may contain a dozen two-line couplets shuffled in with a handful of six-line sestets and one much longer stanza.

Here's an example of the use of stanza breaks in free verse—an excerpt from the poem "A Sharply Worded Silence" by Louise Glück—which consists of a four-line quatrain , followed by a single line, followed by a three-line tercet . Notice how the stanza breaks serve to break the poem into units of speech or thought—much like paragraphs in prose .

Because it is the nature of garden paths to be circular, each night, after my wanderings, I would find myself at my front door, staring at it, barely able to make out, in darkness, the glittering knob. It was, she said, a great discovery, albeit my real life. But certain nights, she said, the moon was barely visible through the clouds and the music never started. A night of pure discouragement. And still the next night I would begin again, and often all would be well.

Types of Stanzaic Form

For the most part, stanzas are named according to the number of lines they contain.

- Couplet: A stanza made up of two lines. The simplest and most basic unit of poetry in English is the rhyming couplet.

- Tercet: A stanza made up of three lines. Also called a tristich. Forms of poetry that are based on the tercet include villanelles and terza rima .

- Quatrain: A stanza made up of four lines. The unit of many traditional forms of poetry, such as ballads and sestinas .

- Cinquain: A stanza made up of five lines. Also called a quintain. Some poems, such as the Japanese tanka and the American cinquain, consist of a single five-line stanza.

- Sestet: A stanza made up of six lines. Also called a sestain. Sestets appear primarily in sonnets .

Other Types of Stanzas

There are other types of stanzas that are not simply defined by their number of lines. These specialized types of stanzas are defined by specific rhyme scheme or metrical requirements, or they always appear in specific poetic forms. Here are just a few of the more common types of stanzas that are defined by rhyme scheme or meter.

- Ballad Stanza: A type of four-line stanza common in English poetry. It is generally written in common meter with an ABCB rhyme scheme.

- Octave: This is an eight-line stanza in iambic pentameter, usually with an ABBA ABBA rhyme scheme. It is of particular importance to sonnets, though it also appears in other forms.

- Elegiac couplet: One of the more common forms in ancient Greek and Latin verse, elegiac couplets are defined by their meter: alternating dactylic hexameter and pentameter. Elegiac couplets are scarcely used by poets writing in English.

- Envoi: An envoi is a brief concluding stanza at the end of a poem that summarizes the preceding poem or serves as its dedication. This type of stanza is defined not by its length, meter, or rhyme scheme, but rather by its content and its position at the end of the poem. Envois appear most often in the poetic form called the ballade .

- Stand-alone lines: Used almost exclusively in free verse, single-line stanzas are seldom be referred to as stanzas, but should be acknowledged as constituting a unit of poetry in and of themselves when preceded and followed by double line breaks.

Breaking Down and Adding Up Stanzas

Stanzas consisting of four or more lines may sometimes be described as containing shorter stanzas within them, even if there is no stanza break. For example, the first two lines of a quatrain may be referred to as a couplet, even if they do not form their own stanza. This can make it easier, when speaking or writing about a poem, to break larger pieces down into units that are shorter than stanzas but longer than individual lines.

The same is true of grouping multiple stanzas together. Two distinct quatrains may be described as making up a single octave, as is often the case with sonnets —the two quatrains that begin a sonnet are, together, referred to as the octave. Similarly, the two halves of an octave can always also be referred to as quatrains. What this means is that while stanzas are usually set off from other stanzas by lines breaks or indentation, that isn't always the case. For instance, fourteen-line sonnets often appear without any stanza breaks at all—and yet the first eight lines of the poem are still referred to as the octave.

In some cases, a stanza can be broken down multiple ways. For example, a stanza that is a sestet may be described as consisting of two tercets, even though there may not be a stanza break between the two tercets to distinguish them. On the other hand, a sestet may also be described as consisting of three couplets. Neither would be improper, but which one you choose may be informed by a few separate factors. A sestet with the rhyme scheme ABCABC would more likely be described as consisting of two tercets than three couplets, since it would be more natural to break the stanza up into two units with a rhyme scheme of ABC than to break it into three units with rhyme schemes of AB, CA, and BC. A sestet with an ABABAB rhyme scheme, on the other hand, would more properly be described as consisting of three couplets, since such a stanza could be thought of as breaking down into three units with rhyme schemes of AB.

Stanza vs. Strophe

"Strophe," like "stanza," is a term that refers to a grouping of lines in poetry. In some cases it can be used interchangeably with "stanza," while in others it can't:

- When line groupings are inconsistent : "Strophe" is used specifically in the context of poetry that does not use stanzas of consistent length throughout the poem, as is the case with many poems written in free verse . In such cases the term "strophe" can be used interchangeable with "stanza" to refer to any grouping of lines as a unit.

- When line groupings are consistent : When line groupings are either consistent (when all of the stanzas in a poem are four-line quatrains, for instance) or when the line-groupings follow traditional rules (as in the octave and sextet of a sonnet), the word strophe cannot be used. In those cases, "stanza" is always used to refer to such line groupings.

To put it another way: all strophes are stanzas, but not all stanzas are strophes.

Stanza Examples

Couplets in max ritvo's "boy goes to war".

Here's a contemporary example of the use of couplets in a work of free verse by the poet Max Ritvo.

His father told him never start writing or reading in the middle of a book. There’s a title, don’t go on without one. And he didn’t go on without one — he had the title Private. This was life’s taproot — the obedient boy began always at the beginning. Books start out with what the boy calls Beauty — the boat’s still in port. The cat’s alive. Pantry’s packed.

Tercets in Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night"

Tercets are the basic unit of a form known as the villanelle , which follows an A B A rhyme scheme and has two refrains that repeat throughout the poem. These two tercets are the opening two stanzas of one of the more famous modern examples of the villanelle, Dylan Thomas;s "Do no go gentle into that good night."

Do not go gentle into that good night , Old age should burn and rave at close of day ; Rage, rage against the dying of the light . Though wise men at their end know dark is right , Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night .

Quatrains in Millay's "The Ballad of the Harp-Weaver"

This ballad by Edna St. Vincent Millay uses quatrains with a rhyme scheme of A B C B .

“Son,” said my mother , When I was knee- high , “You’ve need of clothes to cover you , And not a rag have I. “There’s nothing in the house To make a boy breeches , Nor shears to cut a cloth with Nor thread to take stitches .

Cinquain in Poe's "To Helen"

Here's an example of a poem by Edgar Allen Poe written entirely in cinquains . In this example, the rhyme scheme is not consistent between stanzas—Poe uses A B A BB in the first and A B A B A in the second, and A BB A B in the third.

Helen, thy beauty is to me Like those Nicean barks of yore That gently, o'er a perfumed sea , The weary, way-worn wanderer bore To his own native shore . On desperate seas long wont to roam , Thy hyacinth hair, thy classic face , Thy Naiad airs have brought me home To the glory that was Greece , And the grandeur that was Rome . Lo, in yon brilliant window- niche How statue-like I see thee stand , The agate lamp within thy hand , Ah! Psyche, from the regions which Are Holy Land !

Couplet in Shakespeare's "Sonnet V"

The lines at the end of this sonnet may be referred to as a "rhyming couplet." This couplet is distinguished from the rest of the poem not by a double line break, but by indentation—as well as by the fact that it uses a separate rhyme scheme from the rest of the sonnet. (In keeping with the form of the English sonnet, this poem uses a rhyme scheme of ABAB CDCD EFEF GG . Notice how the final two lines are the only adjacent lines in the whole poem to rhyme; this is yet another factor that sets them apart as a couplet.)

Those hours, that with gentle work did frame The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell, Will play the tyrants to the very same And that unfair which fairly doth excel; For never-resting time leads summer on To hideous winter, and confounds him there; Sap checked with frost, and lusty leaves quite gone, Beauty o'er-snowed and bareness every where: Then were not summer's distillation left, A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass, Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft, Nor it, nor no remembrance what it was: But flowers distilled, though they with winter meet , Leese but their show; their substance still lives sweet .

Elegiac Couplets in Ovid's "Elegy III"

This brief excerpt from a longer love poem by the Roman poet Ovid makes use of elegiac couplets (though the original meter is lost in translation). Although the couplets aren't separated from one another by double line breaks, each half of the quatrain below may be referred to as a couplet because of the metrical pattern they followed in the original Latin, as well as the AA BB rhyme scheme they follow in English.

Heav'n knows, dear maid, I love no other fair ; In thee lives all my love, my heav'n lies there . Oh! may I by indulgent Fate's decree , With thee lead all my life, and die with thee .

Envoi in Kipling's "Sestina of the Tramp-Royal"

This sestina by Rudyard Kipling is a good example of the sestina's use of envoi , a brief concluding stanza to a poem. The example here is an excerpt of the sestina's final stanza and the envoi . This envoi has three lines, as do all envois in sestinas. Envois also often appear in the poetic form called ballades , where they may have four or more lines.

It’s like a book, I think, this bloomin’ world, Which you can read and care for just so long, But presently you feel that you will die Unless you get the page you’re readin’ done, An’ turn another—likely not so good; But what you’re after is to turn ’em all. Gawd bless this world! Whatever she ’ath done— Excep’ when awful long I’ve found it good. So write, before I die, ‘’E liked it all!’

Stanzas in Milton's "On the New Forcers of Conscience under the Long Parliament"

Here's an example of a poem in which the poet uses indentation to differentiate the stanzas, rather than double line breaks. This poem is a "caudate sonnet," a variation on the sonnet that consists of an octave (or two quatrains) and a sestet (two tercets) followed by a brief concluding portion called a coda, which consists here of two tercets. Milton uses indentation to accentuate lines that are, in a traditional sonnet, the first lines of stanzas. Here, we've color-coded the different stanzas so it's easier to see how the indentation signals stanza breaks.

BECAUSE you have thrown off your Prelate Lord, And with stiff vows renounced his Liturgy, To seize the widowed whore Plurality, From them whose sin ye envied, not abhorred, Dare ye for this adjure the civil sword To force our consciences that Christ set free, And ride us with a Classic Hierarchy, Taught ye by mere A. S. and Rutherford? Men whose life, learning, faith, and pure intent, Would have been held in high esteem with Paul Must now be named and printed heretics By shallow Edwards and Scotch What-d’ye-call! But we do hope to find out all your tricks, Your plots and packing, worse than those of Trent, That so the Parliament May with their wholesome and preventive shears Clip your phylacteries, though baulk your ears, And succour our just fears, When they shall read this clearly in your charge: New Presbyter is but old Priest writ large.

Notice how the six lines of the coda are indented differently from the stanzas in the rest of the poem, signifying the coda's difference from the rest of the sonnet.

Stanzas in Johnny Cash's "Ring of Fire"

This is an example of stanzas in songs with lyrics. "Ring of Fire," a song by the American folk musician Johnny Cash, has verses of four lines and a chorus of five lines. The rhyme scheme is different between the verses and the chorus; it shifts from AA BB in the verse to A B A C A in the chorus. The excerpt below shows the first stanza of the song and the chorus.

Love is a burnin' thing And it makes a fiery ring Bound by wild desire I fell into a ring of fire I fell into a burnin' ring of fire I went down, down, down And the flames went higher And it burns, burns, burns The ring of fire, the ring of fire

Why Do Writers Use Stanzas?

Stanzas are used, much like paragraphs in prose, to group related ideas into units. This helps the poem to feel more structured and, therefore, more digestible to the reader or listener. The specific length, meter, and rhyme scheme of a stanza may be dictated by the poem's form, or they may be decisions that the poet makes freely according to his or her artistic vision. For example, a single-line stanza can be used to convey an image in a dramatic fashion, or an eight-line stanza can be used to convey one long, complex thought.

Other Helpful Stanza Resources

- The Wikipedia Page on Stanza: A somewhat technical explanation, including various helpful examples.

- The dictionary definition of Stanza: A basic definition that includes a bit on the etymology of stanza (in Italian it means "room," or "stopping place.")

- A short video explaining stanzas in under a minute.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

- Formal Verse

- Rhyme Scheme

- Bildungsroman

- Antanaclasis

- End-Stopped Line

- Blank Verse

- Slant Rhyme

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Protagonist

- Anthropomorphism

- Dramatic Irony

- Dynamic Character

- Alliteration

Story Arcadia

Mastering Extended Metaphor Poems: Depth in Poetry Explained

An extended metaphor is a literary device that stretches a single metaphor throughout part of, or the entirety of, a poem. It’s like painting with words, using a comparison to color every corner of a piece, giving it depth and complexity. In poetry, these metaphors are more than just decorative language; they’re the backbone that can support an entire narrative or theme, allowing poets to weave intricate tapestries of meaning.

The power of an extended metaphor lies in its ability to resonate with readers, offering them a kaleidoscope through which they can explore multifaceted ideas and emotions. By sustaining a metaphorical comparison across stanzas, poets invite us into a world where concepts take on tangible shapes, making abstract notions graspable and relatable.

This article will delve into the artistry behind extended metaphors in poetry. We’ll dissect famous examples to understand the techniques poets use to enchant their audience. Furthermore, we’ll provide a practical guide for crafting your own extended metaphor poems—complete with tips for evoking vivid imagery and ensuring your metaphor’s thread remains unbroken.

By the end of this exploration, not only will you appreciate the significance of extended metaphors in poetry but also feel inspired to experiment with this compelling form of expression yourself. Metaphorical language has the unique strength to capture the intricacies of human experience, inviting both writer and reader to dive deeper into the realm of poetic possibility. Unlocking the Power of Extended Metaphors

An extended metaphor is a literary device that stretches a single metaphor throughout part or all of a poem. It’s like painting with words, where the poet uses one image to draw parallels with another concept over several lines or verses. This technique enriches poetry, giving it layers and complexity that resonate with readers on a deeper level.

Take Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18,” where he compares his beloved to a summer’s day. The entire sonnet explores this comparison, examining the beauty and impermanence of both. Through skillful crafting, poets weave their extended metaphors by employing symbolism, clever wordplay, and thematic consistency to ensure the metaphor remains clear and impactful without becoming overwrought.

For instance, in Sylvia Plath’s “Mirror,” the mirror itself speaks as if it were human, reflecting not just the physical appearance of those who look into it but their inner turmoil and the passage of time. Plath masterfully maintains this metaphor throughout the poem, using personification to give the mirror human-like qualities.

By sustaining an extended metaphor, poets invite readers into a multi-dimensional space where emotions and ideas can be explored in profound ways. Crafting Your Own Extended Metaphor Poem

To write an extended metaphor poem, start by identifying the two elements you wish to compare: your subject and the metaphorical vehicle that will carry your theme. For instance, if you’re comparing life to a journey, ‘life’ is your subject, and ‘journey’ is your vehicle. Follow these steps:

1. Choose a strong central theme or emotion for your poem. 2. Decide on the primary metaphor that will run throughout. 3. Begin with a striking opening line to introduce the metaphor. 4. Develop your metaphor by adding layers of meaning with each stanza. 5. Use vivid imagery to paint a picture in the reader’s mind. 6. Ensure coherence by keeping the metaphor consistent throughout.

When creating imagery, be specific and sensory-rich; talk about the “crimson leaves” rather than just “leaves,” for example. To maintain coherence, avoid mixing metaphors which can confuse readers.

Beware of overextending your metaphor to the point where it becomes forced or loses clarity. Also, resist explaining the metaphor too explicitly; trust your readers to understand the connections you’re drawing.

By following these steps and tips, you’ll be able to craft an extended metaphor poem that resonates with depth and creativity. Embracing the Art of Extended Metaphors in Poetry

In conclusion, extended metaphors stand as a testament to the transformative power of poetic language. They allow poets to stretch the wings of creativity, providing depth and complexity to their work. We’ve explored their definition, witnessed their beauty in literature, and uncovered the techniques that make them resonate with readers.

Remember, an extended metaphor is more than a fleeting comparison; it’s a sustained thread that weaves through the fabric of a poem, enriching its texture and color. By following our step-by-step guide and heeding the advice on crafting vivid imagery while avoiding common pitfalls, you can elevate your poetry to new heights.

I encourage you to embrace this literary device. Let your thoughts sail on the metaphorical seas, explore uncharted emotional territories, and express the inexpressible. The power of metaphorical language lies in its ability to encapsulate complex emotions and ideas in a relatable way. So pick up your pen and let your imagination unfurl through the art of extended metaphor poems.

Related Pages:

- Unpacking Extended Metaphor Examples in Literature…

- Exploring the Extended Metaphor: Enhancing Language…

- Exploring the Art of Extended Metaphors: Definitions…

- Exploring the Power of Extended Metaphors: Examples…

- Mastering Extended Metaphors: Enhancing…

- The Intrigue and Power of Implied Metaphors:…

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Extended Metaphor: Definition, Meaning, and Examples in Literature

Hannah Yang

The extended metaphor is a powerful literary device for exploring complex ideas. We encounter extended metaphors in all forms of writing, from Shakespearean plays to fantasy novels to song lyrics in pop culture.

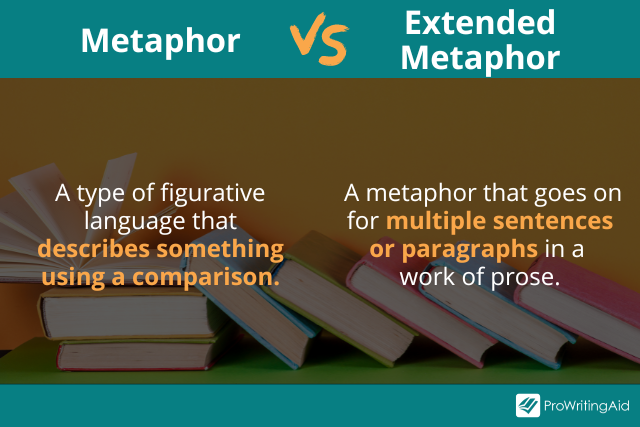

So what exactly is an extended metaphor, and what purpose does it serve? The short answer is that an extended metaphor is a metaphor that continues throughout multiple sentences, multiple paragraphs, or even an entire poem or story.

In this article, we’ll explain how this literary device works, give you five simple steps for building your own extended metaphor, and show you some famous examples of extended metaphors from literature.

Extended Metaphor Definition and Meaning: What Is It?

What’s the structure of an extended metaphor, when you should and shouldn’t use extended metaphors, how to use an extended metaphor in 5 steps, extended metaphor examples in literature, conclusion on the extended metaphor.

A metaphor is a type of figurative language that describes something using a comparison. Here are some common examples of simple metaphors that you might hear every day:

- “Time is money.”

- “I’m a diamond in the rough.”

- “Laughter is the best medicine.”

An extended metaphor refers to a metaphor that the author explores in more detail than a normal metaphor. It can go on for multiple sentences or paragraphs in a work of prose, or multiple lines or stanzas in a poem.

Sometimes, an extended metaphor can even be referenced repeatedly throughout the course of a story or novel, collecting new meaning as the story progresses.

Here’s a quick example of the difference between a metaphor and an extended metaphor.

- Metaphor: “Her fury was a hammer.”

- Extended metaphor: “Her fury was a hammer. Whenever she got angry, everyone around her looked like a nail. She wished she could wield her anger like a precision tool, but with a hammer there was no room for finesse, only blunt violence. Every time she got in an argument, out came the hammer, striking at not just the person she was arguing with but also her parents, her siblings, and even her pet dog.”

An extended metaphor takes a central comparison and expands it using more specific details.

Usually, an extended metaphor starts with a simple statement equating two things, such as “Her fury was a hammer.” Then, the author weaves in more details to explain what they mean by that comparison. Each detail should add more nuance to the initial statement, helping the reader understand what the author is trying to say.

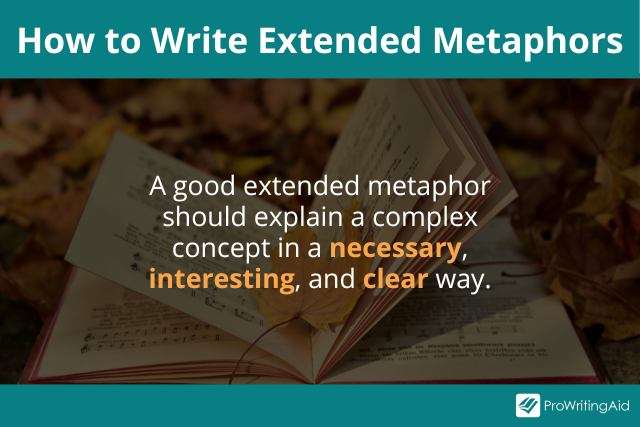

A well-written extended metaphor can be very powerful, but an unnecessary or convoluted one can make your reader scratch their heads or even stop reading entirely.

So how do you know when you should and shouldn’t use extended metaphors?

The answer is simple: just remember that a good extended metaphor should explain a complex concept in a necessary, interesting, and clear way.

The three keywords in the sentence above are necessary , interesting , and clear . A successful extended metaphor needs to meet all three criteria.

Let’s look at each of these rules in more detail.

Rule 1: Make Sure It’s Necessary

Necessary means that the concept you’re explaining with your extended metaphor is truly important enough to warrant a detailed explanation. If the extended metaphor isn’t essential to the story, it will only waste your readers’ time.

Consider this example of an unnecessary extended metaphor: “My mosquito bites were an open flame, and I was a moth. They burned me every time I scratched them, but I just couldn’t stop.”

This metaphor makes sense, but unless the narrator’s mosquito bites are particularly important to the story, the reader doesn’t need to hear about them in so much detail.

You could just write, “I couldn’t stop scratching my mosquito bites,” and move on, rather than devoting an entire paragraph to explaining how itchy they are.

Rule 2: Make Sure It’s Interesting

Interesting means that the metaphor provides an original, funny, or thought-provoking insight. If your extended metaphor isn’t interesting, it will just bore your readers.

Consider this example of an uninteresting extended metaphor: “Her eyes were a blue ocean. I wanted to swim in them forever.”

This metaphor makes sense—we can all picture the color of the ocean—so the meaning is clear. Unfortunately, it’s not particularly interesting. Blue eyes are often compared to oceans, so this paragraph feels clichéd and unnecessary.

ProWritingAid’s Clichés Report highlights overused expressions in your writing so you can make sure your metaphors are original.

Rule 3: Make Sure It’s Clear

Finally, the third keyword, clear, means that the metaphor helps the reader understand the complex concept better. If your extended metaphor isn’t clear, it will baffle your readers and make them scratch their heads.

Consider this example of an unclear extended metaphor: “Human society is a trash can full of plastic water bottles that have been set on fire. It’s hot, smells bad, and releases a lot of fumes.”

This metaphor is interesting—we’ve certainly never heard the phrase “a trash can full of plastic water bottles that have been set on fire” before—but it isn’t clear.

It doesn’t help us understand human society any better than we did before we read it. If anything, it just made us feel more confused.

Remember those three keywords— necessary , interesting , and clear —and make sure all your extended metaphors fulfill all three. This way, your extended metaphors add to your writing, rather than detract from it.

Writing an extended metaphor might feel daunting at first, but you can break it down into simple steps. Here are five steps you can use to build an extended metaphor.

Step 1: Find a Concept You Need to Explain

The purpose of an extended metaphor is to explain a concept more clearly to the reader, so the first step is to identify a complex concept that you need to explain.

Here are some examples of things that you might want to describe using an extended metaphor:

- Abstract emotions (such as grief, anger, joy)

- Philosophical concepts (such as death, justice, human society)

- Characters’ personalities

- Unusual settings, situations, or environments

Step 2: Choose a Concrete Image to Explain That Concept

Now that you know the complex concept you need to explain, it’s time to choose a point of reference to help you describe it to the reader.

Think about concrete images, objects, or references that are already clear in your reader’s mind.

For example, you might come up with the following comparisons to use as your primary metaphor:

- Her grief was a wall she couldn’t cross.

- Justice is a boat sailing through stormy waters.

- My brother has the personality of a cactus.

In each of these cases, an abstract concept (grief, justice, and a character’s personality) is compared to a specific concrete image (a wall, a boat, and a cactus). The concrete images help the reader understand what the author is trying to say about the abstract concept.

Step 3: Check the Comparison Is Necessary, Interesting, and Clear

Remember those three rules we talked about earlier? Now’s the time to make sure your initial metaphor passes all three tests: necessary, interesting, and clear.

If your central comparison is unnecessary, uninteresting, or unclear, it will just bog down your writing. It’s common for amateur writers to include extended metaphors they don’t need as an attempt to sound profound or original.

Step 4: Expand on the Central Comparison

The central comparison on its own is just a normal metaphor. To make it an extended metaphor, you need to extend it over several lines or passages.

This extension often involves smaller metaphors that expound on the primary metaphor. It takes the central comparison and examines the question, “How are these two things alike?” and provides a more detailed and specific answer.

Let’s look at an example from Step 2: “My brother has the personality of a cactus.” How exactly is the brother’s personality similar to a cactus? Maybe he pricks everyone who gets too close because he prefers to be left alone. Or maybe he can survive in harsh conditions, subsisting with barely any sleep, water, or human contact.

Adding these specific details turns a normal metaphor into an extended metaphor.

Step 5: Repeat the Comparison Throughout the Piece

If you want to, you can revisit your extended metaphor multiple times throughout your book , poem , or story . That way, you can create a sustained metaphor that gathers meaning over time.

This final step is optional, but can be extremely powerful if used correctly. Just make sure each new repetition is also necessary, interesting, and clear.

Here are some extended metaphor examples from works of English literature: novels, plays, poetry, and nonfiction.

In each example, see if you can spot the main comparison and the ways the author expands on it throughout the passage.

Example 1: The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

“I wait. I compose myself. My self is a thing I must now compose, as one composes a speech. What I must present is a made thing, not something born.”

Example 2: As You Like It by William Shakespeare

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts.”

Example 3: The Magicians by Lev Grossman

“But walking along Fifth Avenue in Brooklyn, in his black overcoat and his gray interview suit, Quentin knew he wasn’t happy.

Why not? He had painstakingly assembled all the ingredients of happiness. He had performed all the necessary rituals, spoken the words, lit the candles, made the sacrifices. But happiness, like a disobedient spirit, refused to come. He couldn’t think what else to do.”

Example 4: The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

“So you must stay Essun, and Essun will have to make do with the broken bits of herself that Jija has left behind. You’ll jigsaw them together however you can, caulk in the odd bits with willpower wherever they don’t quite fit, ignore the occasional sounds of grinding and cracking. As long as nothing important breaks, right? You’ll get by. You have no choice. Not as long as one of your children could be alive.”

Example 5: On Writing by Stephen King

“I did as she suggested, entering the College of Education at UMO and emerging four years later with a teacher’s certificate… sort of like a golden retriever emerging from a pond with a dead duck in its jaws. It was dead, all right. I couldn’t find a teaching job and so went to work at New Franklin Laundry for wages not much higher than those I had been making at Worumbo Mills and Weaving four years before.”

Example 6: “To a Young Poet” by Edna St. Vincent Millay

“Time cannot break the bird's wing from the bird. Bird and wing together Go down, one feather.

No thing that ever flew, Not the lark, not you, Can die as others do.”

Example 7: Palimpsest by Catherynne Valente

“The keeping of lists was for November an exercise kin to the repeating of a rosary. She considered it neither obsessive nor compulsive, but a ritual, an essential ordering of the world into tall, thin jars containing perfect nouns.”

There you have it—a complete guide to extended metaphors! I hope this article helped you learn more about this versatile literary device.

Don’t forget to run your writing through ProWritingAid to make sure you’re using figurative language as successfully as possible. Our tool can help you avoid clichés, strengthen your imagery, and more.

Can you think of any extended metaphors from your favorite books? Share them with us in the comments!

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing about Writing: An Extended Metaphor Assignment

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources