How to Start Writing Fiction: The Six Core Elements of Fiction Writing

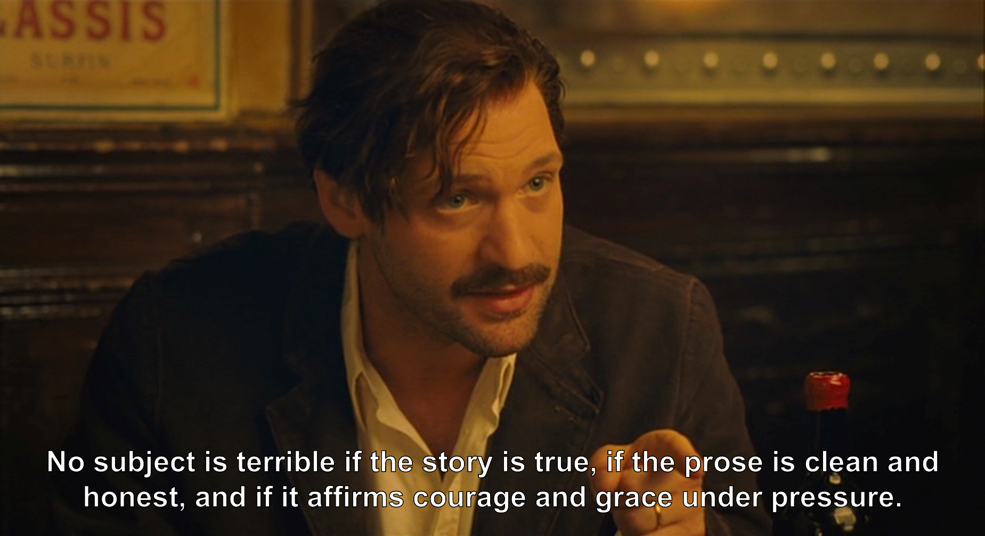

Jack Smith and Sean Glatch | June 14, 2023 | 4 Comments

Whether you’ve been struck with a moment of inspiration or you’ve carried a story inside you for years, you’re here because you want to start writing fiction. From developing flesh-and-bone characters to worlds as real as our own, good fiction is hard to write, and getting the first words onto the blank page can be daunting.

Daunting, but not impossible. Although writing good fiction takes time, with a few fiction writing tips and your first sentences written, you’ll find that it’s much easier to get your words on the page.

Let’s break down fiction to its essential elements. We’ll investigate the individual components of fiction writing—and how, when they sit down to write, writers turn words into worlds. Then, we’ll turn to instructor Jack Smith and his thoughts on combining these elements into great works of fiction. But first, what are the elements of fiction writing?

Introduction to Fiction Writing: The Six Elements of Fiction

Before we delve into any writing tips, let’s review the essentials of creative writing in fiction. Whether you’re writing flash fiction , short stories, or epic trilogies, most fiction stories require these six components:

- Plot: the “what happens” of your story.

- Characters: whose lives are we watching?

- Setting: the world that the story is set in.

- Point of View: from whose eyes do we see the story unfold?

- Theme: the “deeper meaning” of the story, or what the story represents.

- Style: how you use words to tell the story.

It’s important to recognize that all of these elements are intertwined. You can’t build the setting without writing it through a certain point of view; you can’t develop important themes with arbitrary characters, etc. We’ll get into the relationship between these elements later, but for now, let’s explore how to use each element to write fiction.

1. Fiction Writing Tip: Developing Fictional Plots

Plot is the series of causes and effects that produce the story as a whole. Because A, then B, then C—ultimately leading to the story’s climax , the result of all the story’s events and character’s decisions.

If you don’t know where to start your story, but you have a few story ideas, then start with the conflict . Some novels take their time to introduce characters or explain the world of the piece, but if the conflict that drives the story doesn’t show up within the first 15 pages, then the story loses direction quickly.

That’s not to say you have to be explicit about the conflict. In Harry Potter, Voldemort isn’t introduced as the main antagonist until later in the first book; the series’ conflict begins with the Dursley family hiding Harry from his magical talents. Let the conflict unfold naturally in the story, but start with the story’s impetus, then go from there.

2. Fiction Writing Tip: Creating Characters

Think far back to 9th grade English, and you might remember the basic types of story conflicts: man vs. nature, man vs. man, and man vs. self. The conflicts that occur within stories happen to its characters—there can be no story without its people. Sometimes, your story needs to start there: in the middle of a conversation, a disrupted routine, or simply with what makes your characters special.

There are many ways to craft characters with depth and complexity. These include writing backstory, giving characters goals and fatal flaws, and making your characters contend with complicated themes and ideas. This guide on character development will help you sort out the traits your characters need, and how to interweave those traits into the story.

3. Fiction Writing Tip: Give Life to Living Worlds

Whether your story is set on Earth or a land far, far away, your setting lives in the same way your characters do. In the same way that we read to get inside the heads of other people, we also read to escape to a world outside of our own. Consider starting the story with what makes your world live: a pulsing city, the whispered susurrus of orchards, hills that roil with unsolved mysteries, etc. Tell us where the conflict is happening, and the story will follow.

4. Fiction Writing Tip: Play With Narrative Point of View

Point of view refers to the “cameraman” of the story—the vantage point we are viewing the story through. Maybe you’re stuck starting your story because you’re trying to write it in the wrong person. There are four POVs that authors work with:

- First person—the story is told from the “I” perspective, and that “I” is the protagonist.

- First person peripheral—the story is told from the “I” perspective, but the “I” is not the protagonist, but someone adjacent to the protagonist. (Think: Nick Carraway, narrator of The Great Gatsby. )

- Second person—the story is told from the “you” perspective. This point of view is rare, but when done effectively, it can create a sense of eeriness or a personalized piece.

- Third person limited—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator usually writes from the perspective of one or two characters.

- Third person omniscient—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator knows what is happening in each character’s heads and in the world at large.

If you can’t find the right words to begin your piece, consider switching up the pronouns you use and the perspective you write from. You might find that the story flows onto the page from a different point of view.

5. Fiction Writing Tip: Use the Story to Investigate Themes

Generally, the themes of the story aren’t explored until after the aforementioned elements are established, and writers don’t always know the themes of their own work until after the work is written. Still, it might help to consider the broader implications of the story you want to write. How does the conflict or story extend into a bigger picture?

Let’s revisit Harry Potter’s opening scenes. When we revisit the Dursleys preventing Harry from knowing about his true nature, several themes are established: the meaning of family, the importance of identity, and the idea of fate can all be explored here. Themes often develop organically, but it doesn’t hurt to consider the message of your story from the start.

6. Fiction Writing Tip: Experiment With Words

Style is the last of the six fiction elements, but certainly as important as the others. The words you use to tell your story, the way you structure your sentences, how you alternate between characters, and the sounds of the words you use all contribute to the mood of the work itself.

If you’re struggling to get past the first sentence, try rewriting it. Write it in 10 words or write it in 200 words; write a single word sentence; experiment with metaphors, alliteration, or onomatopoeia . Then, once you’ve found the right words, build from there, and let your first sentence guide the style and mood of the narrative.

Now, let’s take a deeper look at the craft of fiction writing. The above elements are great starting points, but to learn how to start writing fiction, we need to examine the craft of combining these elements.

Primer on the Elements of Fiction Writing

First, before we get into the craft of fiction writing, it’s important to understand the elements of fiction. You don’t need to understand everything about the craft of fiction before you start keying in ideas or planning your novel. But this primer will be something you can consult if you need clarification on any term (e.g., point of view) as you learn how to start writing fiction.

The Elements of Fiction Writing

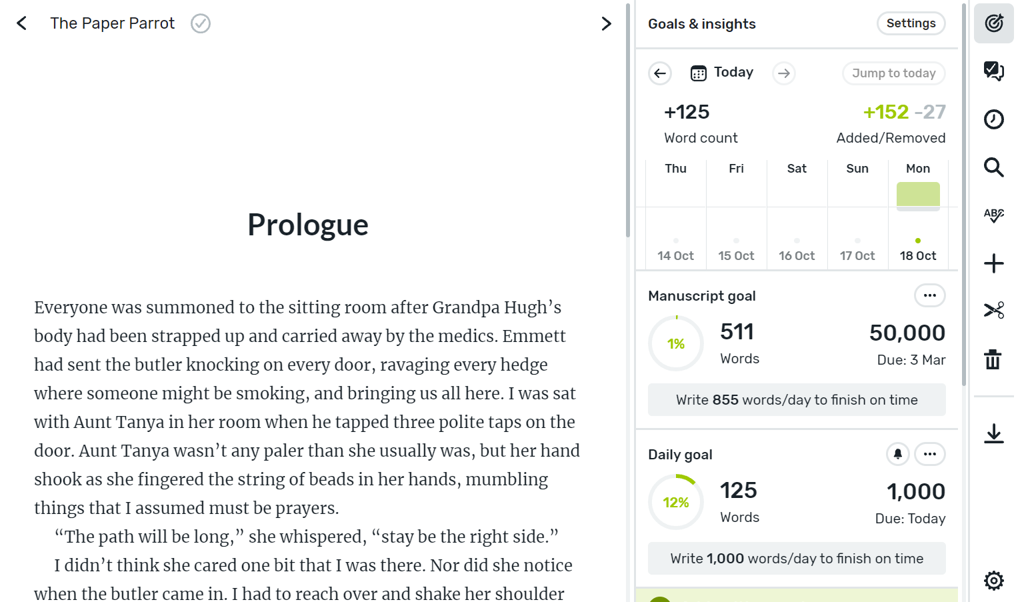

A standard novel runs between 80,000 to 100,000 words. A short novel, going by the National Novel Writing Month , is at least 50,000. To begin with, don’t think about length—think about development. Length will come. It is true that some works lend themselves more to novellas, but if that’s the case, you don’t want to pad them to make a longer work. If you write a plot summary—that’s one option on getting started writing fiction—you will be able to get a fairly good idea about your project as to whether it lends itself to a full-blown novel.

For now, let’s think about the various elements of fiction—the building blocks.

Writing Fiction: Your Protagonist

Readers want an interesting protagonist , or main character. One that seems real, that deals with the various things in life we all deal with. If the writer makes life too simple, and doesn’t reflect the kinds of problems we all face, most readers are going to lose interest.

Don’t cheat it. Make the work honest. Do as much as you can to develop a character who is fully developed, fully real—many-sided. Complex. In Aspects of the Novel , E.M Forster called this character a “round” characte r. This character is capable of surprising us. Don’t be afraid to make your protagonist, or any of your characters, a bit contradictory. Most of us are somewhat contradictory at one time or another. The deeper you see into your protagonist, the more complex, the more believable they will be.

If a character has no depth, is merely “flat,” as Forster terms it, then we can sum this character up in a sentence: “George hates his ex-wife.” This is much too limited. Find out why. What is it that causes George to hate his ex-wife? Is it because of something she did or didn’t do? Is it because of a basic personality clash? Is it because George can’t stand a certain type of person, and he didn’t realize, until too late, that his ex-wife was really that kind of person? Imagine some moments of illumination, and you will have a much richer character than one who just hates his ex-wife.

And so… to sum up: think about fleshing out your protagonist as much as you can. Consider personality, character (or moral makeup), inclinations, proclivities, likes, dislikes, etc. What makes this character happy? What makes this character sad or frustrated? What motivates your character? Readers don’t want to know only what —they want to know why .

Usually, readers want a sympathetic character, one they can root for. Or if not that, one that is interesting in different ways. You might not find the protagonist of The Girl on the Train totally sympathetic, but she’s interesting! She’s compelling.

Here’s an article I wrote on what makes a good protagonist.

Also on clichéd characters.

Now, we’re ready for a key question: what is your protagonist’s main goal in this story? And secondly, who or what will stand in the way of your character achieving this goal?

There are two kinds of conflicts: internal and external. In some cases, characters may not be opposing an external antagonist, but be self-conflicted. Once you decide on your character’s goal, you can more easily determine the nature of the obstacles that your protagonist must overcome. There must be conflict, of course, and stories must involve movement. Things go from Phase A to Phase B to Phase C, and so on. Overall, the protagonist begins here and ends there. She isn’t the same at the end of the story as she was in the beginning. There is a character arc.

I spoke of character arc. Now let’s move on to plot, the mechanism governing the overall logic of the story. What causes the protagonist to change? What key events lead up to the final resolution?

But before we go there, let’s stop a moment and think about point of view, the lens through which the story is told.

Writing Fiction: Point of View as Lens

Is this the right protagonist for this story? Is this character the one who has the most at stake? Does this character have real potential for change? Remember, you must have change or movement—in terms of character growth—in your story. Your character should not be quite the same at the end as in the beginning. Otherwise, it’s more of a sketch.

Such a story used to be called “slice of life.” For example, what if a man thinks his job can’t get any worse—and it doesn’t? He started with a great dislike for the job, for the people he works with, just for the pay. His hate factor is 9 on a scale of 10. He doesn’t learn anything about himself either. He just realizes he’s got to get out of there. The reader knew that from page 1.

Choose a character who has a chance of undergoing change of some kind. The more complex the change, the better. Characters that change are dynamic characters , according to E. M. Forster. Characters that remain the same are static characters. Be sure your protagonist is dynamic.

Okay, an exception: Let’s say your character resists change—that can involve some sort of movement—the resisting of change.

Here’s another thing to look at on protagonists—a blog I wrote: https://elizabethspanncraig.com/writing-tips-2/creating-strong-characters-typical-challenges/

Writing Fiction: Point of View and Person

Usually when we think of point of view, we have in mind the choice of person: first, second, and third. First person provides intimacy. As readers we’re allowed into the I-narrator’s mind and heart. A story told from the first person can sometimes be highly confessional, frank, bold. Think of some of the great first-person narrators like Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield. With first person we can also create narrators that are not completely reliable, leading to dramatic irony : we as readers believe one thing while the narrator believes another. This creates some interesting tension, but be careful to make your protagonist likable, sympathetic. Or at least empathetic, someone we can relate to.

What if a novel is told in first person from the point of view of a mob hit man? As author of such a tale, you probably wouldn’t want your reader to root for this character, but you could at least make the character human and believable. With first person, your reader would be constantly in the mind of this character, so you’d need to find a way to deal with this sympathy question. First person is a good choice for many works of fiction, as long as one doesn’t confuse the I-narrator with themselves. It may be a temptation, especially in the case of fiction based on one’s own life—not that it wouldn’t be in third person narrations. But perhaps even more with a first person story: that character is me . But it’s not—it’s a fictional character.

Check out my article on writing autobiographical fiction, which appeared in The Writer magazine. https://www.writermag.com/2018/07/31/filtering-fact-through-fiction/

Third person provides more distance. With third person, you have a choice between three forms: omniscient, limited omniscient, and objective or dramatic. If you get outside of your protagonist’s mind and enter other characters’ minds, you are being omniscient or godlike. If you limit your access to your protagonist’s mind only, this is limited omniscience. Let’s consider these two forms of third-person narrators before moving on to the objective or dramatic POV.

The omniscient form is rather risky, but it is certainly used, and it can certainly serve a worthwhile function. With this form, the author knows everything that has occurred, is occurring, or will occur in a given place, or in given places, for all the characters in the story. The author can provide historical background, look into the future, and even speculate on characters and make judgments. This point of view, writers tend to feel today, is more the method of nineteenth-century fiction, and not for today. It seems like too heavy an authorial footprint. Not handled well—and it is difficult to handle well—the characters seem to be pawns of an all-knowing author.

Today’s omniscience tends to take the form of multiple points of view, sometimes alternating, sometimes in sections. An author is behind it all, but the author is effaced, not making an appearance. BUT there are notable examples of well-handled authorial omniscience–read Nobel-prize winning Jose Saramago’s Blindness as a good example.

For more help, here’s an article I wrote on the omniscient point of view for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/omniscient-pov/

The limited omniscient form is typical of much of today’s fiction. You stick to your protagonist’s mind. You see others from the outside. Even so, you do have to be careful that you don’t get out of this point of view from time to time, and bring in things the character can’t see or observe—unless you want to stand outside this character, and therein lies the omniscience, however limited it is.

But anyway, note the difference between: “George’s smiles were very welcoming” and “George felt like his smiles were very welcoming”—see the difference? In the case of the first, we’re seeing George from the outside; in the case of the second, from the inside. It’s safer to stay within your protagonist’s perspective as much as possible and not describe them from the outside. Doing so comes off like a point-of-view shift. Yet it’s true that in some stories, the narrator will describe what the character is wearing, tell us what his hopes and dreams are, mention things he doesn’t know right now but will later—and perhaps, in rather quirky stories, the narrator will even say something like “Our hero…” This can work, and has, if you create an interesting narrative voice. But it’s certainly a risk.

The dramatic or objective point of view is one you’ll probably use from time to time, but not throughout your whole novel. Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants” is handled with this point of view. Mostly, with maybe one exception, all we know is what the characters say and do, as in a play. Using this point of view from time to time in a longer work can certainly create interest. You can intensify a scene sometimes with this point of view. An interesting back and forth can be accomplished, especially if the dialogue is clipped.

I’ve saved the second-person point of view for the last. I would advise you not to use this point of view for an entire work. In his short novel Bright Lights, Big City , Jay McInerney famously uses this point of view, and with some force, but it’s hard to pull off. In lesser hands, it can get old. You also cause the reader to become the character. Does the reader want to become this character? One problem with this point of view is it may seem overly arty, an attempt at sophistication. I think it’s best to choose either first or third.

Here’s an article I wrote on use of second person for The Writer magazine. Check it out if you’re interested. https://www.writermag.com/2016/11/02/second-person-pov/

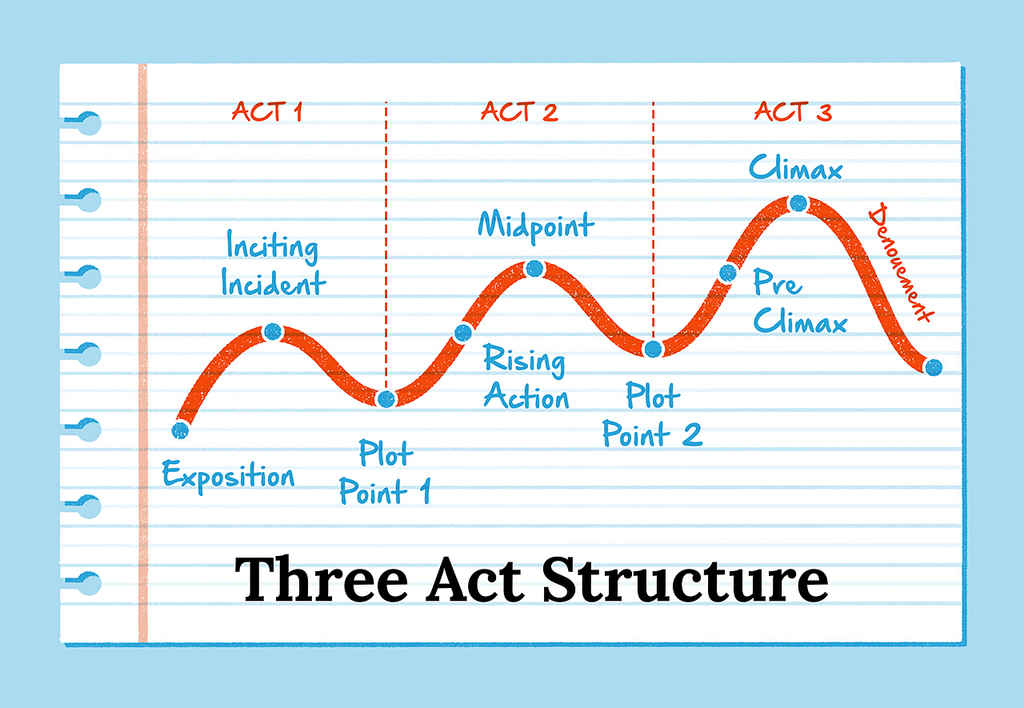

Writing Fiction: Protagonist and Plot and Structure

We come now to plot, keeping in mind character. You might consider the traditional five-stage structure : exposition, rising action, crisis and climax, falling action, and resolution. Not every plot works this way, but it’s a tried-and-true structure. Certainly a number of pieces of literature you read will begin in media re s—that is, in the middle of things. Instead of beginning with standard exposition, or explanation of the condition of the protagonist’s life at the story’s starting point, the author will begin with a scene. But even so, as in Jerzy Kosiński’s famous novella Being There , which begins with a scene, we’ll still pick up the present state of the character’s life before we see something that complicates it or changes the existing equilibrium. This so-called complication can be something apparently good—like winning the lottery—or something decidedly bad—like losing a huge amount of money at the gaming tables. One thing is true in both cases: whatever has happened will cause the character to change. And so now you have to fill in the events that bring this about.

How do you do that? One way is to write a chapter outline to prevent false starts. But some writers don’t like plotting in this fashion, but want to discover as they write. If you do plot your novel in advance, do realize that as you write, you will discover a lot of things about your character that you didn’t have in mind when you first set pen to paper. Or fingers to keyboard. And so, while it’s a good idea to do some planning, do keep your options open.

Let’s think some more about plot. To have a workable plot, you need a sequence of actions or events that give the story an overall movement. This includes two elements which we’ll take up later: foreshadowing and echoing (things that prepare us for something in the future and things that remind us of what has already happened). These two elements knit a story together.

Think carefully about character motivations. Some things may happen to your character; some things your character may decide to do, however wisely or unwisely. In the revision stage, if not earlier, ask yourself: What motivates my character to act in one way or another? And ask yourself: What is the overall logic of this story? What caused my character to change? What were the various forces, whether inner or outer, that caused this change? Can I describe my character’s overall arc, from A to Z? Try to do that. Write a short paragraph. Then try to write down your summary in one sentence, called a log line in film script writing, but also a useful technique in fiction writing as well. If you write by the discovery method, you probably won’t want to do this in the midst of the drafting, but at least in the revision stage, you should consider doing so.

With a novel you may have a subplot or two. Assuming you will, you’ll need to decide how the plot and the subplot relate. Are they related enough to make one story? If you think the subplot is crucial for the telling of your tale, try to say why—in a paragraph, then in a sentence.

Here’s an article I wrote on structure for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/revision-grammar/find-novels-structure/

Writing Fiction: Setting

Let’s move on to setting . Your novel has to take place somewhere. Where is it? Is it someplace that is particularly striking and calls for a lot of solid description? If it’s a wilderness area where your character is lost, give your reader a strong sense for the place. If it’s a factory job, and much of the story takes place at the worksite, again readers will want to feel they’re there with your character, putting in the hours. If it’s an apartment and the apartment itself isn’t related to the problems your character is having, then there’s no need to provide that much detail. Exception: If your protagonist concentrates on certain things in the apartment and begins to associate certain things about the apartment with their misery, now there’s reason to get concrete. Take a look, when you have a chance, at the short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” It’s not an apartment—it’s a house—but clearly the setting itself becomes important when it becomes important to the character. She reads the wallpaper as a statement about her own condition.

Here’s the URL for ”The Yellow Wall-Paper”: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/theliteratureofprescription/exhibitionAssets/digitalDocs/The-Yellow-Wall-Paper.pdf

Sometimes setting is pretty important; sometimes it’s much less important. When it doesn’t serve a purpose to describe it, don’t, other than to give the reader a sense for where the story takes place. If you provide very many details, even in a longer work like a novel, the reader will think that these details have some significance in terms of character, plot, or theme—or all three. And if they don’t, why are they there? If setting details are important, be selective. Provide a dominant impression. More on description below.

If you’re interested, here’s a blog on setting I wrote for Writers.com: https://writers.com/what-is-the-setting-of-a-story

Writing Fiction: Theme and Idea

Most literary works have a theme or idea. It’s possible to decide on this theme before you write, as you plan out your novel. But be careful here. If the theme seems imposed on the work, the novel will lose a lot of force. It will seem—and it may well be—engineered by the author much like a nonfiction piece, and lose the felt experience of the characters.

Theme must emerge from the work naturally, or at least appear to do so. Once you have a draft, you can certainly build ideas that are apparent in the work, and you can even do this while you’re generating your first draft. But watch out for overdoing it. Let the characters (what they do, what they say) and the plot (the whole storyline with its logical connections) contribute on their own to the theme. Also you can depend on metaphors, similes, and analogies to point to the theme—as long as these are not heavy-handed. Avoid authorial intrusion, authorial impositions of any kind. If you do end up creating a simile, metaphor, or analogy through rational thinking, make sure it sounds natural. That’s not easy, of course.

Writing Fiction: Handling Scenes

Keep a few things in mind about writing scenes. Not every event deserves a whole scene, maybe only a half-scene, a short interaction between characters. Scenes need to do two things: reveal character and advance plot. If a scene seems to stall out and lack interest, in the revision mode you might try using narrative summary instead (see below).

Good fiction is strongly dramatic, calling for scenes, many of them scenes with dialogue and action. Scenes need to involve conflict of some kind. If everyone is happy, that’s probably going to be a dull scene. Some scenes will be narrative, without dialogue. You need some interesting action to make these work.

Let’s consider scenes with dialogue.

The best dialogue is speech that sounds natural, and yet isn’t. Everything about fiction is an artifice, including speech. But try to make it sound real. The best way to do this is to “hear” the voices in your head and transcribe them. Take dictation. If you can do this, whole conversations will seem very real, believable. If you force what each character has to say, and plan it out too much, it will certainly sound planned out, and not real at all. Not that in the revision mode you can’t doctor up the speech here and there, but still, make sure it comes off as natural sounding.

Some things to think about when writing dialogue: people usually speak in fragments, interrupt each other, engage in pauses, follow up a question with a comment that takes the conversation off course (non sequiturs). Note these aspects of dialogue in the fiction you read.

Also, note how writers intersperse action with dialogue, setting details, and character thoughts. As far as the latter goes, though, if you’ll recall, I spoke of the dramatic point of view, which doesn’t get into a character’s mind but depends instead on what characters do and say, as in a play. You may try this point of view out in some scenes to make them really move.

One technique is to use indirect dialogue, or summary of what a character said, not in the character’s own words. For instance: Bill made it clear that he wasn’t going to the city after all. If anybody thought that, they were wrong .

Now and then you’ll come upon dialogue that doesn’t use the standard double quotes, but perhaps a single quote (this is British), or dashes, or no punctuation at all. The latter two methods create some distance from the speech. If you want to give your work a surreal quality, this certainly adds to it. It also makes it seem more interior.

One way to kill good dialogue is to make characters too obviously expository devices—that is, functioning to provide background or explanations of certain important story facts. Certainly characters can serve as expository devices, but don’t be too heavy-handed about this. Don’t force it like the following:

“We always used to go to the beach, you recall? You recall how first we would have breakfast, then take a long walk on the beach, and then we would change into our swimsuits, and spend an hour in the water. And you recall how we usually followed that with a picnic lunch, maybe an hour later.”

This sounds like the character is saying all this to fill the reader in on backstory. You’d need a motive for the utterance of all of these details—maybe sharing a memory?

But the above sounds stilted, doesn’t it?

One final word about dialogue. Watch out for dialogue tags that tell but don’t show . Here’s an example:

“Do you think that’s the case,” said Ted, hoping to hear some good news. “Not necessarily,” responded Laura, in a barky voice. “I just wish life wasn’t so difficult,” replied Ted.

If you’re going to use a tag at all—and many times you don’t need to—use “said.” Dialogue tags like the above examples can really kill the dialogue.

Writing Fiction: Writing Solid Prose

Narrative summary : As I’ve stated above, not everything will be a scene. You’ll need to write narrative summary now and then. Narrative summary telescopes time, covering a day, a week, a month, a year, or even longer. Often it will be followed up by a scene, whether a narrative scene or one with dialogue. Narrative summary can also relate how things generally went over a given period. You can write strong narrative summary if you make it specific and concrete—and dramatic. Also, if we hear the voice of the writer, it can be interesting—if the voice is compelling enough.

Exposition : It’s the first stage of the 5-stage plot structure, where things are set up prior to some sort of complication, but more generally, it’s a prose form which tells or informs. You use exposition when you get inside your character, dealing with his or her thoughts and emotions, memories, plans, dreams. This can be difficult to do well because it can come off too much like authorial “telling” instead of “showing,” and readers want to feel like they’re experiencing the world of the protagonist, not being told about this world. Still, it’s important to get inside characters, and exposition is often the right tool, along with narrative summary, if the character is remembering a sequence of events from the past.

Description : Description is a word picture, providing specific and concrete details to allow the reader to see, not just be told. Concreteness is putting the reader in the world of the five senses, what we call imagery . Some writers provide a lot of details, some only a few—just enough that the reader can imagine the rest. Consider choosing details that create a dominant impression—whether it’s a character or a place. Similes, metaphors, and analogies help readers see people and places and can make thoughts and ideas (the reflections of your character or characters) more interesting. Not that you should always make your reader see. To do so might cause an overload of images.

Check out these two articles: https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/the-definitive-guide-to-show-dont-tell/ https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/figurative-language-in-fiction/

Writing Fiction: Research

Some novels require research. Obviously historical novels do, but others do, too, like Sci Fi novels. Almost any novel can call for a little research. Here’s a short article I wrote for The Writer magazine on handling research materials. It’s in no way an in-depth commentary on research–but it will serve as an introduction. https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/research-in-fiction/

For a blog on novel writing, check this link at Writers.com: https://writers.com/novel-writing-tips

For more articles I’ve published in The Writer , go here: https://www.writermag.com/author/jack-smith/

How to Start Writing Fiction: Take a Writing Class!

To write a story or even write a book, fiction writers need these tools first and foremost. Although there’s no comprehensive guide on how to write fiction for beginners, working with these elements of fiction will help your story bloom.

All six elements synergize to make a work of fiction, and like most works of art, the sum of these elements is greater than the individual parts. Still, you might find that you struggle with one of these elements, like maybe you’re great at writing characters but not very good with exploring setting. If this is the case, then use your strengths: use characters to explore the setting, or use style to explore themes, etc.

Getting the first draft written is the hardest part, but it deserves to be written. Once you’ve got a working draft of a story or novel and you need an extra set of eyes, the Writers.com community is here to give feedback: take a look at our upcoming courses on fiction writing, and check out our talented writing community .

Good luck, and happy writing!

I have had a story in my mind for over 15 years. I just haven’t had an idea how to start , putting it down on print just seems too confusing. After reading this article I’m even more confused but also more determined to give it a try. It has given me answers to some of my questions. Thank you !

You’ve got this, Earl!

Just reading this as I have decided to attempt a fiction work. I am terrible at writing outside of research papers and such. I have about 50 single spaced pages “written” and an entire outline. These tips are great because where I struggle it seems is drawing the reader in. My private proof reader tells me it is to much like an explanation and not enough of a story, but working on it.

first class

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing

by Joslyn Chase | 0 comments

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

Have you ever been told by some well-meaning soul that writing can’t be taught? Have you heard that the ability to create beautiful sentences and convey a heart-wrenching story is inborn, and you either have it or you don’t?

It’s amazing to me that you can walk into any art museum in the world and see students sketching, studying, learning from the masters, developing technique and honing their skill. In music schools across the globe, professors and musicians instruct thirsty learners, passing on what they learned from their own teachers. And so it goes.

Yet, many believe that writing is an innate skill that cannot be attained through similar methods. What they’re missing is what I call “the second half of the equation.”

Fire Plus Algebra

The Argentine writer and poet Jorge Luis Borges said, “Art is fire plus algebra.”

It may be that the spark of fire burns more fierce and bright in some writers, igniting inspiration and the stroke of genius, just as it does in painters, sculptors, musicians, and artists of every stripe. But that flame blazes in all of us, to some degree, and can be fanned by passion and dedication.

What’s more, we can apply the algebra through deliberate study and practice, supplying that second half of the equation. I believe writing can absolutely be taught and learned.

I Am Not Alone

One of my favorite writers, Elizabeth George, says this in her book, Write Away :

“I’ve long believed that there are two distinct but equally important halves to the writing process: One of these is related to art, the other is related to craft. Obviously art cannot be taught. No one can give another human being the soul of an artist, the sensibility of a writer, or the passion to put words on paper that is the gift and the curse of those who fashion poetry and prose. But it’s ludicrous to suggest and shortsighted to believe that the fundamentals of fiction can’t be taught.”

And here’s David Farland’s take on the matter, from his Story Doctor website:

“Part of learning to write is to discover what your own gifts are and then play to your strengths. But unless you overcome your weaknesses, you probably won’t get far. For example, the great comic might need to learn to control his pacing, or perhaps the world creator might need to learn how to develop lovable characters. It seems that no matter how much you excel as a writer, there are always new skills to develop. “Many of those new skills can come pretty easily. As an instructor, I find that if I describe a problem well, suggest solutions, then give the writer an exercise, the writer can almost always gain new writing skills pretty easily. In fact, about 1/3 of the time, I’m amazed at how well the writers do. They almost seem to grow magically.”

And though I don’t have the exact quote in front of me, I remember Stephen King’s remarks on the subject in On Writing . He opined that good writers may not become great writers through studying the craft, but even bad writers can become good writers with enough practice, and there’s room for improvement in all of us.

How to Practice Writing Fiction

The best way to practice writing fiction is to focus on one skill at a time. Choose one area of your writing, study what other writers have to say, and then put it into practice (the best practice is deliberate practice ).

What skills should you practice? Below, I've listed five skills that are important for every fiction writer and gathered resources to help you practice. The first two resources for each skill are articles that you can read and apply in just a few minutes. Then, I've included two books that will give you a deeper study of each.

Story Structure

- A Writer’s Cheatsheet to Plot and Structure

- How To Write a Thriller Novel

- The Story Grid , Shawn Coyne

- Wired For Story , Lisa Cron

Point of View

- Point of View Magic

- The Ultimate Point of View Guide

- Characters & Viewpoint , Orson Scott Card

- Rivet Your Readers with Deep Point of View , Jill Elizabeth Nelson

- How to Use Political Debate to Write Dialogue That Sings

- Critique: 10 Ways to Write Excellent Dialogue

- How to Write Dazzling Dialogue , James Scott Bell

- “Shut up!” He explained , William Noble

Creating Emotion

- 3 Tips to “Show, Don’t Tell” Emotions and Moods

- One Surprising Method for Creating Emotion in Your Readers

- Writing for Emotional Impact , Karl Iglesias

- The Emotional Craft of Fiction , Donald Maass

Using Hooks

- How to Write a Hook by Baiting Your Reader With Questions

- How to End a Story . . . and Hook Your Readers for Your Next One

- Writing Active Hooks , Mary Buckham

- The First Five Pages , Noah Lukeman

Make a Resolution

If it feels like I’m making a case for studying, learning, and practicing the craft of writing, that’s because I am. I’m a big believer and a passionate supporter of the idea. I love learning everything I can about how to write better, how to tell a more compelling story, how to express ideas more clearly, how to create more engaging characters, and anything else that will help me deliver a more satisfying experience to my readers.

The new year is right around the corner, and I’d like to challenge you to make a resolution. Apply the algebra. Create a study plan, determine to learn a new skill, and practice it in the next book or story you write.

Then focus on another skill and practice that one as you keep on writing new stories. This will give fuel to both ends of the equation, feeding the algebra, as well as the fire.

Make 2020 your breakout year for learning the craft and embracing the art of writing.

Do you believe writing can be taught? Do you have more strategies for how to practice writing fiction? Tell us about it in the comments.

Give it a go: right now, for fifteen minutes , practice writing.

For each of the skills above, I've linked to a Write Practice article with a practice exercise at the end of the post. Choose one of those skills, read the article, complete the practice exercise at the end, and share your practice in the comments of that article.

Of course, The Write Practice has hundreds of articles about how to learn and practice a large variety of writing skills. Continue your practice today by using the search box to explore, or come back tomorrow for another exercise.

There are limitless amounts of resources out there and the possibilities are exciting!

Join 100 Day Book

Enrollment closes May 14 at midnight!

Joslyn Chase

Any day where she can send readers to the edge of their seats, prickling with suspense and chewing their fingernails to the nub, is a good day for Joslyn. Pick up her latest thriller, Steadman's Blind , an explosive read that will keep you turning pages to the end. No Rest: 14 Tales of Chilling Suspense , Joslyn's latest collection of short suspense, is available for free at joslynchase.com .

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes – PASIVE INCOME - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes – SEO Tips By William - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes – Debra Officer's IM Tips - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes – Survey of earning money – lucky draw - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

- 50+ Writing Contests in 2020 with Awesome Cash Prizes - Proper Methods - […] How to Practice Writing Fiction: 5 Core Skills to Improve Your Writing […]

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

How to Write Fiction: 9 Steps From a Bestselling Novelist

By jerry jenkins.

Guest Post by Jerry Jenkins

That you’ve landed here tells me you have a story—a message you want to share with the world. You just need to know how to begin.

Writing fiction isn’t about rules or techniques or someone else’s ideas. It’s about your story well told.

Writing a novel can be overwhelming.

I’ve written nearly 200 books (two-thirds of them novels) and have enjoyed the kind of success most writers only dream of. But the work never gets easier.

I’ve found no shortcuts, but following certain steps help me create books in which my readers can get delightfully lost.

Is that the kind of novel you want to write?

Table of Contents

9 Steps to Writing Captivating Fiction

- Come up with a great story idea.

- Create realistic and memorable characters.

- Choose a story structure.

- Home in on the setting.

- Write your rough draft.

- Grab your reader from the get-go.

- Trigger the theater of your reader’s mind.

- Maintain your reader’s attention with cliffhangers.

- Write a resounding, satisfying ending.

Want to sell more books? Click here to get your free copy of 8 Simple Secrets to Big Book Sales on Amazon

Step #1 — come up with a great story idea..

Do you struggle to generate ideas?

Maybe you have a message to share but no story idea to help you convey it.

Ideas are everywhere. You have to learn to recognize the germ of an idea that can become a story .

My first novel was about a judge who tries a man for a murder that the judge committed.

That’s all I had—along with its obvious ramifications.

I knew guilt. I recalled being caught in a lie. So I could imagine the ultimate dilemma—desperate to hide the truth while being assigned to oversee its coming to light.

That imagining became Margo , the novel that launched my fiction career.

I know a story idea has legs when it stays with me and grows.

I find myself sharing the idea with my family, embellishing the story more every time I tell it. If it loses steam, it’s because I’ve lost interest in it and know readers would too.

But if it holds my interest, I nourish and develop it until it becomes a manuscript and eventually a book .

Always carry something on which you can record ideas, electronic or old school. (I like the famous Moleskine notebooks.)

Jot or dictate ideas that strike at any moment for these elements:

- Anything that might expand your story

And if you’re still having trouble conjuring an idea, see Step #2 below for an exercise writers everywhere have told me works to stimulate their thinking almost every time.

Step #2 — Create realistic and memorable characters.

Ironically, Fiction (though you know its definition) must be believable , even if it’s set in a land far, far away or centuries before or since now.

That means characters must feel real and relatable so readers will buy your premise.

If you don’t know where to begin, consider creating characters who are composites of people you know.

You might use one person’s gender, another’s looks, another’s personality, another’s voice …

Now here’s that exercise I promised above:

Imagine you’re at a rural intersection in the middle of nowhere. Maybe there are cornfields all around.

A Greyhound bus appears on the horizon and rumbles to a stop. One passenger disembarks.

Now ask yourself who this character is:

- Male or female?

- Young or old?

- Rich or poor?

- Laden with luggage or empty-handed?

- Are they waiting to be picked up or heading somewhere on foot?

- Where are they going?

- Are they escaping someone or something?

- Are they running to someone or something?

By now you should have an idea of a main character and, bottom line, start imagining a story.

You need a villain too, but be fair to him (or her; I use he inclusively to mean both genders and avoid the awkward repetition of he/she; I know the majority of writers—and readers—are women).

So what do I mean by “be fair to your villain”?

Simply this: don’t allow him to be one-dimensional (evil just because he’s the bad guy).

In real life, villainous people rarely recognize themselves as evil. They think everyone else is wrong!

Give him real, credible motivations for doing what he does. That doesn’t make him right, but it can make him real and believable.

One thing that contributed to the success of my Left Behind series was that I determined early on to have credible, skeptical characters.

It’s so easy to build straw men and shoot down their arguments and logic like shooting fish in a barrel.

Make them credible! Give them opinions and arguments that are hard to counter.

Give your skeptical reader someone he can identify with and force him to acknowledge you were fair to his side.

Our goal as writers should be that the stories and characters we create will live in the hearts of readers for years.

How you develop your characters will make or break your story .

Outliners have an advantage here, and we Pantsers (who write by the seat of our pants as a process of discovery) do well to learn from them.

Outliners map out the backstory of each character, getting to know them before starting to write.

Some even conduct imaginary interviews, simply asking the characters about themselves. Readers will never see most of what comes from this information, but it does inform the writing.

Whether you get to know your characters in advance or allow them to reveal themselves as you write, make them human, vulnerable, and flawed—eventually heroic and inspiring.

Just don’t make them perfect. Nobody relates to perfect .

Consider some of literature’s most memorable characters—Jane Eyre, Scarlett O’Hara, Atticus Finch, Ebenezer Scrooge, Huckleberry Finn, Katniss Everdeen, Harry Potter.

Here are heroes of both genders, vastly different personalities, widely varying ages, and even from different centuries. But look what they have in common:

- They’re larger than life but also universally human

- They see courage not as lack of fear but rather the ability to act in the face of fear

- They learn from failure and rise to great moral victories

Compelling characters like these make the difference between a memorable story and a forgettable one.

Keys to Developing a Memorable Character

1. Introduce him by name as soon as possible.

Your lead character should be the first person on stage, and the reader should be able to connect with him.

His name should reflect his heritage and maybe even hint at his personality. In The Green Mile , Stephen King named a weak, cowardly character Percy Wetmore. Naturally, we treat heroes with more respect.

2. Give readers a look at him.

You want readers to clearly picture your character in their minds, but don’t make the mistake of forcing them to see him exactly as you do.

While rough height, hair color, and maybe eye color should be established—as well as whether he is athletic or not—does it really matter whether your reader visualizes your hero as Brad Pitt or Leonardo DiCaprio or your heroine as Gwyneth Paltrow or Charlize Theron?

Now, similar to what I’ll advise later about rendering settings, it’s better to layer in your character’s looks through dialogue and action rather than using description as a separate element.

Whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser, the more you know about your character, the better you will tell your story.

- Nationality and ethnicity?

- Scars? Piercings? Tattoos? Imperfections? Deformities?

- Tone of voice? Accent?

- Mannerisms, unique gestures, tics, anything else that would set him apart?

Avoid the mistake of trying to include in your manuscript everything you know about your character.

But on the other hand, the more you know, and the more you know, the more plot ideas that might emerge.

The better acquainted you are with your character, the better your readers will come to know and care about him.

3. Give him a backstory.

Backstory is everything that has happened in your character’s life before page one of chapter one. What has made him the person he is today?

Things you should know, whether or not you include them in your story:

- When, where, and to whom he was born

- Brothers and sisters and where he fits in the family

- His educational background

- Political leanings

- Skills and talents

- Spiritual life

- Best friend

- Romantic relationship, if any

- Personality type

- Anger triggers

- Joys, pleasures

- And anything else relevant to your story

4. Make him real.

Even superheroes have flaws and weaknesses. For Superman, it’s Kryptonite. For Indiana Jones, snakes.

Perfect characters are impossible to identify with. But don’t make his flaws deal breakers—they should be forgivable, understandable, identifiable, but not irredeemable.

For instance, don’t make him a wimp, a coward, or a doofus (like a cop who either misplaces his weapon or forgets to load it).

Create a character with whom your reader can relate, someone vulnerable who subtly exhibits strength of character and potential heroism.

Does your character show respect to a waitress and recognize her by name?

Would he treat a cashier the same way he treats his broker?

If he’s running late but witnesses an emergency, does he stop and help?

Some call these pet-the-dog moments , where an otherwise bigger-than-life personality does something out of character—something that might be considered beneath him.

And you can add real texture to your narrative by even giving your villain a pet-the-dog moment.

5. But also give him heroic potential. In the end, he must rise to the occasion and score a great moral victory.

So he needs to be both extraordinary and relatable. He can’t remain a victim for long.

He can and should face obstacles and adversity, but he should never act the wimp or appear cowardly.

Give him qualities—or at least potential—that captivates the reader and compels him to keep reading. For example:

- an underdog with surprising resolve that allows him to rise to the occasion

- a character who reveals the hint of a hidden strength or ability and later uses it to win the day

Make him heroic and you make him unforgettable.

6. Emphasize his inner life as well.

The outward trouble, quest, challenge—whatever drives the story—is one thing. But every bit as important is your character’s internal conflict .

What keeps him awake at night?

- What’s his blind spot?

- What are his secrets?

- What embarrasses him?

- What is he passionate about?

Mix and match details from people you know—and yourself—to create both the inner and outer person.

When he faces a life or death situation, you’ll know how he should respond.

7. Draw upon your own experience.

The fun of writing fiction is getting to embody the characters we create.

I can be a young girl, an old man, a boy, a father, a grandmother, of another race, a villain, of a different political or spiritual persuasion, etc. The possibilities are endless.

Become your character .

Imagine yourself in every situation he finds himself, facing every dilemma, answering every question—how would you react if you were your character?

If your character finds himself in danger, even if you’ve never experienced something so terrible, you can imagine it.

Think back to the last time you felt in danger, multiply that times a thousand, and become your character.

- Imagine being at home alone and hearing footsteps across the floor above.

- Have you ever had your child go missing?

- Have you ever mustered the courage to speak your mind and set somebody straight?

All those feelings and emotions go into creating believable, credible characters.

8. Give him a character arc.

The more your character transforms, the more effective and memorable your story.

Classic stories plunge their main characters into terrible trouble, turn up the heat, and turn those characters into heroes—or failures.

That’s the very definition of character arc .

How your character responds to challenges determines his character arc.

Step #3 — Choose a story structure.

Structure is the skeleton of your story. Regardless whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser, you need a basic structure to know where you’re going.

The story structure you choose should help you align and sequence:

- The Conflict

- The Resolution

Discovering bestselling novelist Dean Koontz’s 4-step Classic Story Structure catapulted me from a mid-list genre novelist to a 21-Time New York Times bestselling author.

It’s simply this:

1. Plunge your main character into terrible trouble as soon as possible.

Naturally, the definition of that trouble depends on your genre, but, in short, it’s the worst possible dilemma you can think of for your main character.

For a thriller, it might be a life-or-death situation. In a romance novel, it could mean a young woman having to choose between two equally qualified suitors—and then her choice proves a disaster.

Whatever the scenario, this terrible trouble must bear stakes dire enough to carry the entire novel.

One caveat: whatever the trouble, it will mean little to readers if they don’t first find reasons to care about your character. Implant reasons to care.

It’s not just the trouble but the ramifications, the stakes.

2. Everything your character does to get out of this terrible trouble makes things only worse.

Avoid the temptation to make life easy for your protagonist.

Every complication must proceed logically from the one before it, and things must grow progressively worse until …

3. The situation appears hopeless.

Novelist Angela Hunt refers to this as The Bleakest Moment. Even you should wonder how you’re ever going to write your character out of this.

The predicament becomes so hopeless that your lead must use every new muscle and technique gained from facing countless obstacles to become heroic and prove that things only appeared beyond repair.

4. Finally, your hero succeeds (or fails*) against all odds.

Reward readers with the payoff they expected by keeping your hero on stage, taking action.

*Occasionally sad endings work too.

Step #4 — Home in on the setting.

The setting of a story includes the location and time period but should also include sights, smells, tastes, textures, and sounds.

Thoroughly research your setting, but remember: such detail should be used as seasoning, not become the main course .

The main course must always be the story. Research details just lend credibility and believability.

One of the most common and avoidable errors is to begin by describing your setting.

Don’t get me wrong—description is important, as is establishing where your story takes place.

But we’ve all read snooze-worthy novels that promise to transport us, only to begin with some variation of the following:

The house sat in a deep wood surrounded by …

Pro tip: modern readers have little patience for description as a separate element.

So how do you describe your setting?

You don’t. At least not in the conventional way.

The key is to layer description into the action.

Show, Don’t Tell

Instead, make description part of the story . References to how things look and feel and sound register in the theater of the readers’ minds (more on this later), while they’re concentrating on the action, dialogue, tension, drama, and conflict—things that keep them turning the pages.

They’ll barely notice that you worked in details of your setting, but somehow they have all they need to fully enjoy the reading experience.

London’s West End, 1862

Lucy Knight mince-stepped around clumps of horse dung as she hurried toward Regent Street. Must not be late, she told herself. What would he think?

She carefully navigated the cobblestones as she crossed to hail a Hansom Cab—which she preferred for its low center of gravity and smooth turning. Lucy did not want to appear as if she’d been tossed about in a carriage, especially tonight.

“Not wearin’ a ring, I see,” the driver said as she boarded.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Nice-lookin’ lady like yourself out alone after dark in the cold fog — ”

“You needn’t worry about me, sir. I’m only going to the circus.”

“Piccadilly it is, ma’am.”

The location tag at the beginning saves us a lot of narration, which lets the story quickly emerge.

The reader learns everything about the setting and the character from the action and dialogue instead of a separate piece of description.

Notice how, without the description of the city of that era existing as a separate (and potentially boring) element, we learn in passing of horse dung, cobblestone streets, Hansom Cabs, cold weather, fog, Regent Street, Piccadilly Circus, and even that it’s after dark.

But, hopefully, what keeps our interest is our perspective character—a single young lady headed for a rendezvous with a man we want to meet as much as she does.

Showing (instead of telling) forces you to highlight only the most important details.

If it’s not important enough to become part of the action, your reader won’t miss it anyway.

Step #5 — Write your rough draft.

If you wear a perfectionist cap, now’s the time to remove it and hit the off switch to your internal editor. Allow yourself the freedom to write without worrying about grammar, cliches, redundancies, or any other rules. Just get your story down.

Separate your writing from your revising. You’ll have plenty of time at that stage to play perfectionist to your heart’s content.

Step #6 — Grab your reader from the get-go.

The best way to hook your reader immediately is to plunge your character into terrible trouble as soon as possible instead of wasting your first two or three pages on backstory or setting or description.

These can all be layered in as the story progresses. Cut the fluff and jump straight into the story.

Done properly, this virtually forces your reader to keep turning the pages.

Step #7 — Trigger the theater of your reader’s mind.

When comparing a book to its movie, don’t most people usually say they liked the book better?

Even with all its high-tech computer-generated imagery, glitz and glamour, Hollywood cannot compete with the theater of the reader’s mind .

I once read about a woman who was thrilled to discover in her parents’ home a book she cherished as a child.

She sat to thumb through it in search of the beautiful paintings she remembered so vividly, only to find that the book didn’t have a single illustration.

The author had so engaged the theater of her young mind that her memory of that book was much different than reality.

Your job as a writer is not to dictate what your reader should see but to trigger his imagination.

- The late, great detective novelist John D. MacDonald once described one of his orbital characters simply as “knuckly”—that was his entire description. I don’t know what image that conjures in your mind, but I immediately remembered a hardware store clerk in the town where I grew up. The guy was tall, bony, and had a protruding adam’s apple. I got all that from “knuckly.”

- In one of my Left Behind novels, I described a computer techie as “oily.” My editor said, “Can’t you say he was pudgy, with longish blond hair, and kept having to push his glasses back up on his nose?”

I said, “If that’s what you saw, why do I have to say it?”

Millions read that series, and I’m sure a few saw the guy exactly as my editor did.

Others saw him as I did, while others no doubt saw him as something completely different. So much the better.

The more detail you leave to the theater of your reader’s mind, the more he’ll be engaged in your story.

If you want to give details that distinguish your main character, fine—work them into the action.

Just don’t tell your readers exactly what to think .

1. Always think reader-first.

Don’t spoon-feed your reader. He wants to learn, so don’t do all his work for him. Let him imagine and deduce things as he sees them in his mind.

He’s a partner in your story, so give him a role. That’s what makes reading enjoyable.

2. Resist the urge to explain (RUE).

If you write, “I walked through the open door and sat down in a chair,” you’re explaining a lot that doesn’t need explaining.

You don’t need to tell your reader someone walked through a door—but even if you do, you certainly don’t need to tell him it was open.

And unless you need to clarify that “I flopped on the floor” or something similar, your reader will assume he sat in a chair.

Instead, you could write: “I walked in and sat down.”

Eliminate details that can be assumed.

Give readers just enough detail to engage their mental projector—that’s where the magic happens.

Step #8 — Maintain your reader’s attention with cliffhangers.

I’m talking about a setup, because setups demand payoffs. And anticipating a payoff keeps your reader with you.

Ask yourself:

- What withheld from my readers will best keep them riveted?

- How long can I make them wait for that payoff without unnecessarily frustrating them?

Cliffhangers need not be reserved for only the ends of chapters.

Envision your entire story as one big setup with a series of smaller ones layered in to keep the reader engaged.

Every scene can, in essence, serve as a cliffhanger leading to a payoff.

When your hero confronts his best friend over an apparent insult, we keep reading.

Will the accused deny everything or break down and confess? Maybe we know his response is a lie, which results in a new cliffhanger—when and how will your protagonist learn the truth, and then what will happen?

Every sentence, every scene, should serve as a mini-cliffhanger—a setup that demands a payoff.

Be constantly giving your reader reasons to stick with your story.

Step #9 — Write a resounding, satisfying ending.

You have one job: delivering a memorable reading experience.

Readers have invested their time and money, counting on you to uphold your end of the bargain—a story that wholly satisfies.

That doesn’t mean every ending is happily-ever-after with everything tied in a bow.

It just means the reader knows what happened, questions are answered, things are resolved, and puzzles are solved .

And because I happen to have a worldview of hope, my endings reflect that.

If you write from another worldview, at least be consistent. End your stories with how you view life, but don’t simply stop.

That said, a story can end too neatly and appear contrived. And if it ends too late, you’ve forced your reader to indulge you for too long. Be judicious.

In the same way you decide when to enter and leave a scene, carefully determine when to exit your story:

- Don’t rush it. Give readers a satisfying conclusion. And give it the time it needs so you’re thrilled with every word. Keep revising until it feels just right.

- If it’s unpredictable, it had better be fair and logical so your reader doesn’t feel cheated. You want him delighted with the surprise, not feeling tricked.

- If you have multiple ideas for how your story should end, aim for the heart rather than the head. Readers remember most what moves them.

Writing fiction well is hard, exhausting work. (If you don’t find it so, you may not be doing it right.) But, oh, the rewards.

Sell More Books

Enter your name and email below to get your free copy of my exclusive guide:

8 Simple Secrets to Big Book Sales on Amazon

Enter your name and email below to gain instant access to my ultimate guide:

How to Write Better Fiction and Become a Great Novelist

by Tom Corson-Knowles | 14 comments

Do you have what it takes to become a great fiction writer?

In this article, I want to share some important ideas and steps you can take to become an accomplished novelist for those who are willing to put in the work required to achieve greatness.

Becoming a great fiction writer requires an enormous amount of study and practice. You have to study in order to learn how others have written great stories before you so you can model them, and you have to constantly practice so that you can combine your newfound knowledge with experience.

Write Better Fiction

Anyone can write a story. Young children often write stories before they are ten years old, long before they ever master the many rules and nuances of English usage, grammar, syntax and spelling.

Many adults write stories, too, but few of these stories ever turn into a published book.

Less than 1% of fiction writers ever get a traditional book publishing deal.

Why do so many fiction writers fail to get published after spending months or even years to write a book?

There are many reasons human beings fail to achieve big goals in any area of life.

Why Writers Fail

Here are some of the most common reasons why writers fail to become great novelists:

- They give up when things get tough (and things always get tough at some point in life).

- They get discouraged by rejections (the road to success in publishing is paved with a lot of rejection).

- They are afraid of what others think of them, and this fear stops them from being truly creative and expressing their own voice and ideas freely in their writing (great writers all share one thing in common—they stop caring what others think of them at some point, even if only for a few hours while writing their book).

- They think they know how to be a great writer already, and so they don’t listen to criticism or try to improve (meaning they keep making the same writing mistakes over and over again).

- They are afraid of making mistakes when instead they should be focused on learning and improving when they make mistakes.

- They are motivated by external goals instead of an internal calling (if you “have to” earn $5,000 a month as a writer and fail to hit your goal, you will give up, whereas a writer who sees writing as their mission and life purpose will keep writing consistently even after they earn billions of dollars like J.K. Rowling).

- They have bad habits and fail to implement good writing habits (their most precious time is squandered on tasks that don’t help them achieve their goals and won’t produce long-term results).

- They fail to think long-term and so they waste their time chasing short-term dollars and “easy money” instead of creating work that has long-term value.

- They fail to set meaningful goals (instead of focusing on earning a certain amount of money, you should focus on creating something that matters and makes a meaningful impact in a way that is important to you and your values).

- They fail to seek help and advice from others who have come before them, and so they miss out on the most important lessons and ideas from leaders in their field.

How to Write Fiction Successfully

Writing great fiction requires far more hard work and effort than most writers are willing to put in.

If you really want to become a successful fiction writer, you have to take an honest look at yourself and decide if you are willing to truly commit your life to it. If you’re not willing to treat your fiction writing as a life calling and serious long-term business venture, then you should expect to get the same results you would from any other hobby – a little bit of fun and fulfillment, but not a lot of income or fame.

You have to ask yourself a simple question:

Do you really want to write a great book, or are you just trying to get a book published without putting in the effort required to make it as good as it could be?

You might think you are dedicated, committed and hard-working, but how much effort have you actually put into writing your book?

Have you plotted the entire novel or series?

Do you have a written timeline and storyboards for your story?

Do you really understand each of the characters in your story and what their motivations, strengths and weaknesses are?

Have you edited your book at least 50 times by yourself after the first draft was finished?

After you edited your book at least 50 times, have you gone through further rounds of editing by hiring a professional developmental editor, a professional copyeditor and a professional proofreader?

Professional writers who already have several published bestselling novels do all or most of the above. They don’t take shortcuts or expect instant results without putting in the work.

If you’re a first-time author with no experience writing fiction, you’re going to have to work really hard to compete. Harder than you have ever worked in your life.

Here’s what you should do if you’re serious about becoming a great fiction writer…

Keep a Journal

Buy a journal or notebook specifically for taking notes on the craft and business of writing. When you listen to an interview with a bestselling author, read a great book, learn something about writing from a reader or from any other source, jot it down in your writing journal.

Keep a record of all the great ideas you come across. As your writing journal grows so will your writing skills.

Once you have your journal ready, it’s time to start studying.

Let’s begin with reading…

Study these Books on Writing Fiction

Plotting and planning your novel is a crucial step that far too many authors skip. Developing a great system for plotting your book can save you literally thousands of hours by stopping you from writing scenes or even entire books that don’t make sense.

As least half of the novels submitted to TCK Publishing suffer from a fatal flaw – the complete lack of proper plotting and planning. The author wasted time and pages writing scenes that don’t move the story forward and don’t create a compelling story. No amount of copy editing or proofreading can fix such a book. Instead, you must rewrite most of the book which can often be more difficult than just writing a new, properly plotted book.

Every story has the potential for greatness – what really matters is how you write the story you wish to tell, not the story itself. Plotting is how you structure a great story and ensure that only scenes that are important to the story are left in, and every unnecessary scene is excluded.

Don’t let this short, simple, affordable book 2k to 10k by Fantasy author Rachel Aaron fool you. It is hands-down the best book on writing I have ever read. Although the book is written specifically for fiction writers, I have found Rachel’s system for plotting and planning to be incredibly helpful for writing absolutely anything – from fiction to non-fiction books and even important emails and documents.

The promise of 2k to 10k is that it will help you dramatically increase your daily word count (from 2,000 words per day to 10,000 words per day for the author). It certainly delivers on its promise for any serious writer who applies its lessons, but it can also help you become a better writer, not just a faster writer. And that is just as important, if not even more important.

Simple and Direct 4th edition

Written by Jacques Barzon, Simple and Direct is a classic book with a simple message: good writing should be clear, simple and direct. Too many writers hide behind big words, fancy prose and unnecessary tricks instead of simply writing to communicate ideas.

There is a myth going around that great writers must be able to write beautiful language, and that each sentence must be a work of art. Simple and Direct will destroy any wishful thinking that such a belief will make you a great writer. Instead, communicating as clearly as you can in your writing is what will make you great. Instead of aiming to write a masterpiece of prose, most writers should simply focus on writing to communicate.

When a reader gets confused because they can’t understand what you are trying to communicate, you’ve lost that reader, and they will probably never come back.

On Writing: A Memoir Of The Craft

Stephen King is one of the most famous writers alive today, and for good reason. He knows how to write a good story well. This unique book is part memoir, part advice to the up-and-coming writers of our generation. You have to dig a bit, but there is a whole lot of good advice and wisdom in On Writing for those who are willing to find it and take heed.

Some of my favorite parts of the book are when King selects samples of writing that he calls “good” and “bad” and explains what makes some writing bad and how to fix it. The book is full of great stories from King’s life. One thing is for sure – you will feel different about being an author after reading On Writing. Whether it helps turn you into a better writer or not is up to you.

I highly recommend taking notes in your writing journal while you read this book.

Making Ideas Happen: Overcoming the Obstacles Between Vision and Reality

Author Scott Belsky shares some profound lessons and actionable steps you can take to become more creative and actually turn your ideas into a reality. There are many creative people out there who come up with countless good ideas. But good ideas are worthless if you don’t turn them into reality through action.

Making Ideas Happen shows you how to take your good ideas and make them real by getting organized, collaborating with other great minds and becoming a leader. If you’ve ever felt like you have a lot of good ideas but never know what to do with them, this book will change your life and turn you from a “frustrated creative” to a productive author, artist and entrepreneur.

It’s not enough to just have good ideas. You have to learn how to become a great implementer of good ideas.

The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 3rd Edition

The Writers Journey by Christopher Vogler is based on the work by Joseph Campbell on the hero’s journey. The Writers Journey is more readable and more detailed than any other work I’ve found on the hero’s journey.

It provides a clear picture and insight into the fundamental framework of all great stories. It is a classic guidebook for any writer looking to tell a better story, or any human looking to better understand why and how stories are so fundamental to humanity.

This is the densest and longest book on writing in this list, but it’s worth the effort to read it from beginning to end. Take your time with The Writers Journey and fill your writing journal with the big ideas that catch your interest.

On Writing Well

This little collection of essays on writing should be required reading in schools and businesses across the world. You’ll learn the importance of brevity and clarity in writing, and how to communicate your ideas without wasting a single word.

On Writing Well was written for non-fiction writers, but it should be required reading fiction and non-fiction writers alike.

Interviews Every Novelist Should Listen To