Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction to Literature: What? Why? How?

When is the last time you read a book or a story simply because it interested you? If you were to classify that book, would you call it fiction or literature? This is an interesting separation, with many possible reasons for it. One is that “fiction” and “literature” are regarded as quite different things. “Fiction,” for example, is what people read for enjoyment. “Literature” is what they read for school. Or “fiction” is what living people write and is about the present. “Literature” was written by people (often white males) who have since died and is about times and places that have nothing to do with us. Or “fiction” offers everyday pleasures, but “literature” is to be honored and respected, even though it is boring. Of course, when we put anything on a pedestal, we remove it from everyday life, so the corollary is that literature is to be honored and respected, but it is not to be read, certainly not by any normal person with normal interests.

Sadly, it is the guardians of literature, that is, of the classics, who have done so much to take the life out of literature, to put it on a pedestal and thereby to make it an irrelevant aspect of American life. People study literature because they love literature. They certainly don’t do it for the money. But what happens too often, especially in colleges, is that teachers forget what it was that first interested them in the study of literature. They forget the joy that they first felt (and perhaps still feel) as they read a new novel or a poem or as they reread a work and saw something new in it. Instead, they erect formidable walls around these literary works, giving the impression that the only access to a work is through deep learning and years of study. Such study is clearly important for scholars, but this kind of scholarship is not the only way, or even necessarily the best way, for most people to approach literature. Instead it makes the literature seem inaccessible. It makes the literature seem like the province of scholars. “Oh, you have to be smart to read that,” as though Shakespeare or Dickens or Woolf wrote only for English teachers, not for general readers.

What is Literature?

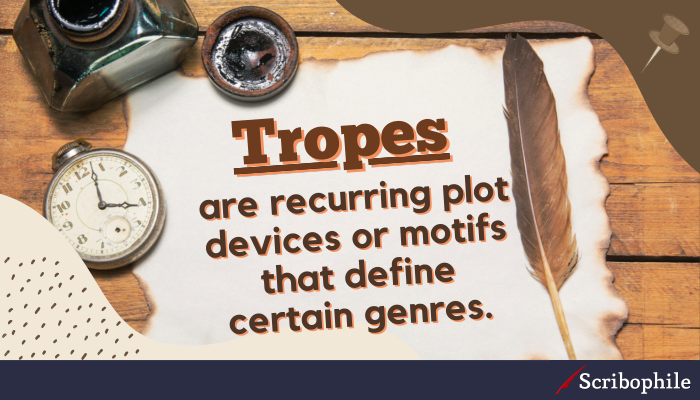

In short, literature evokes imaginative worlds through the conscious arrangement of words that tell a story. These stories are told through different genres, or types of literature, like novels, short stories, poetry, drama, and the essay. Each genre is associated with certain conventions. In this course, we will study poetry, short fiction, and drama (in the form of movies).

Some Misconceptions about Literature

Of course, there are a number of misconceptions about literature that have to be gotten out of the way before anyone can enjoy it. One misconception is that literature is full of hidden meanings . There are certainly occasional works that contain hidden meanings. The biblical book of Revelation , for example, was written in a kind of code, using images that had specific meanings for its early audience but that we can only recover with a great deal of difficulty. Most literary works, however, are not at all like that. Perhaps an analogy will illustrate this point. When I take my car to my mechanic because something is not working properly, he opens the hood and we both stand there looking at the engine. But after we have looked for a few minutes, he is likely to have seen what the problem is, while I could look for hours and never see it. We are looking at the same thing. The problem is not hidden, nor is it in some secret code. It is right there in the open, accessible to anyone who knows how to “read” it, which my mechanic does and I do not. He has been taught how to “read” automobile engines and he has practiced “reading” them. He is a good “close reader,” which is why I continue to take my car to him.

The same thing is true for readers of literature. Generally authors want to communicate with their readers, so they are not likely to hide or disguise what they are saying, but reading literature also requires some training and some practice. Good writers use language very carefully, and readers must learn how to be sensitive to that language, just as the mechanic must learn to be sensitive to the appearances and sounds of the engine. Everything that the writer wants to say, and much that the writer may not be aware of, is there in the words. We simply have to learn how to read them.

Another popular misconception is that a literary work has a single “meaning” (and that only English teachers know how to find that meaning). There is an easy way to dispel this misconception. Just go to a college library and find the section that holds books on Shakespeare. Choose one play, Hamlet , for example, and see how many books there are about it, all by scholars who are educated, perceptive readers. Can it be the case that one of these books is correct and all the others are mistaken? And if the correct one has already been written, why would anyone need to write another book about the play? The answer is this:

Key Takeaways

There is no single correct way to read any piece of literature.

Again, let me use an analogy to illustrate this point. Suppose that everyone at a meeting were asked to describe a person who was standing in the middle of the room. Imagine how many different descriptions there would be, depending on where the viewer sat in relation to the person. For example, an optometrist in the crowd might focus on the person’s glasses; a hair stylist might focus on the person’s haircut; someone who sells clothing might focus on the style of dress; a podiatrist might focus on the person’s feet. Would any of these descriptions be incorrect? Not necessarily, but they would be determined by the viewers’ perspectives. They might also be determined by such factors as the viewers’ ages, genders, or ability to move around the person being viewed, or by their previous acquaintance with the subject. So whose descriptions would be correct? Conceivably all of them, and if we put all of these correct descriptions together, we would be closer to having a full description of the person.

This is most emphatically NOT to say, however, that all descriptions are correct simply because each person is entitled to his or her opinion

If the podiatrist is of the opinion that the person is five feet, nine inches tall, the podiatrist could be mistaken. And even if the podiatrist actually measures the person, the measurement could be mistaken. Everyone who describes this person, therefore, must offer not only an opinion but also a basis for that opinion. “My feeling is that this person is a teacher” is not enough. “My feeling is that this person is a teacher because the person’s clothing is covered with chalk dust and because the person is carrying a stack of papers that look like they need grading” is far better, though even that statement might be mistaken.

So it is with literature. As we read, as we try to understand and interpret, we must deal with the text that is in front of us ; but we must also recognize (1) that language is slippery and (2) that each of us individually deals with it from a different set of perspectives. Not all of these perspectives are necessarily legitimate, and it is always possible that we might misread or misinterpret what we see. Furthermore, it is possible that contradictory readings of a single work will both be legitimate, because literary works can be as complex and multi-faceted as human beings. It is vital, therefore, that in reading literature we abandon both the idea that any individual’s reading of a work is the “correct” one and the idea that there is one simple way to read any work. Our interpretations may, and probably should, change according to the way we approach the work. If we read The Chronicles of Narnia as teenagers, then in middle age, and then in old age, we might be said to have read three different books. Thus, multiple interpretations, even contradictory interpretations, can work together to give us a fuller and possibly more interesting understanding of a work.

Why Reading Literature is Important

Reading literature can teach us new ways to read, think, imagine, feel, and make sense of our own experiences. Literature forces readers to confront the complexities of the world, to confront what it means to be a human being in this difficult and uncertain world, to confront other people who may be unlike them, and ultimately to confront themselves.

The relationship between the reader and the world of a work of literature is complex and fascinating. Frequently when we read a work, we become so involved in it that we may feel that we have become part of it. “I was really into that movie,” we might say, and in one sense that statement can be accurate. But in another sense it is clearly inaccurate, for actually we do not enter the movie or the story as IT enters US; the words enter our eyes in the form of squiggles on a page which are transformed into words, sentences, paragraphs, and meaningful concepts in our brains, in our imaginations, where scenes and characters are given “a local habitation and a name.” Thus, when we “get into” a book, we are actually “getting into” our own mental conceptions that have been produced by the book, which, incidentally, explains why so often readers are dissatisfied with cinematic or television adaptations of literary works.

In fact, though it may seem a trite thing to say, writers are close observers of the world who are capable of communicating their visions, and the more perspectives we have to draw on, the better able we should be to make sense of our lives. In these terms, it makes no difference whether we are reading a Homeric epic poem like The Odysse y, a twelfth-century Japanese novel like The Tale of Genji , or a Victorian novel by Dickens, or even, in a sense, watching someone’s TikTok video (a video or movie is also a kind of text that can be “read” or analyzed for multiple meanings). The more different perspectives we get, the better. And it must be emphasized that we read such works not only to be well-rounded (whatever that means) or to be “educated” or for antiquarian interest. We read them because they have something to do with us, with our lives. Whatever culture produced them, whatever the gender or race or religion of their authors, they relate to us as human beings; and all of us can use as many insights into being human as we can get. Reading is itself a kind of experience, and while we may not have the time or the opportunity or or physical possibility to experience certain things in the world, we can experience them through reading. So literature allows us to broaden our experiences.

Reading also forces us to focus our thoughts. The world around us is so full of stimuli that we are easily distracted. Unless we are involved in a crisis that demands our full attention, we flit from subject to subject. But when we read a book, even a book that has a large number of characters and covers many years, the story and the writing help us to focus, to think about what they show us in a concentrated manner. When I hold a book, I often feel that I have in my hand another world that I can enter and that will help me to understand the everyday world that I inhabit.

Literature invites us to meet interesting characters and to visit interesting places, to use our imagination and to think about things that might otherwise escape our notice, to see the world from perspectives that we would otherwise not have.

Watch this video for a discussion of why reading fiction matters.

How to Read Literature: The Basics

- Read with a pen in hand! Yes, even if you’re reading an electronic text, in which case you may want to open a new document in which you can take notes. Jot down questions, highlight things you find significant, mark confusing passages, look up unfamiliar words/references, and record first impressions.

- Think critically to form a response. Here are some things to be aware of and look for in the story that may help you form an idea of meaning.

- Repetitions . You probably know from watching movies that if something is repeated, that means something. Stories are similar—if something occurs more than once, the story is calling attention to it, so notice it and consider why it is repeated. The repeated element can be a word or a phrase, an action, even a piece of clothing or gear.

- Not Quite Right : If something that happens that seems Not Quite Right to you, that may also have some particular meaning. So, for example, if a violent act is committed against someone who’s done nothing wrong, that is unusual, unexpected, that is, Not Quite Right. And therefore, that act means something.

- Address your own biases and compare your own experiences with those expressed in the piece.

- Test your positions and thoughts about the piece with what others think (we’ll do some of this in class discussions).

While you will have your own individual connection to a piece based on your life experiences, interpreting literature is not a willy-nilly process. Each piece of writing has purpose, usually more than one purpose–you, as the reader, are meant to uncover purpose in the text. As the speaker notes in the video you watched about how to read literature, you, as a reader, also have a role to play. Sometimes you may see something in the text that speaks to you; whether or not the author intended that piece to be there, it still matters to you.

For example, I’ve had a student who had life experiences that she was reminded of when reading “Chonguita, the Monkey Bride” and another student whose experience was mirrored in part of “The Frog King or Iron Heinrich.” I encourage you to honor these perceptions if they occur to you and possibly even to use them in your writing assignments. I can suggest ways to do this if you’re interested.

But remember that when we write about literature, our observations must also be supported by the text itself. Make sure you aren’t reading into the text something that isn’t there. Value the text for what is and appreciate the experience it provides, all while you attempt to create a connection with your experiences.

Attributions:

- Content written by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed CC BY NC SA .

- Content adapted from Literature, the Humanities, and Humanity by Theodore L. Steinberg and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Worry Free Writer by Dr. Karen Palmer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Literature Copyright © by Judy Young is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.2: The Purpose of Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86405

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

What is literature for?

One of the primary goals of this course is to develop an understanding of the importance of literature as a vital source of cultural knowledge in everyday life. Literature is often viewed as a collection of made-up stories, designed to entertain us, to amuse us, or to simply provide us with an escape from the “real” world.

Although literature does serve these purposes, in this course, one of the ways that we will answer the question “What is literature for?” is by showing that literature can provide us with valuable insights about the world in which we live and about our relationships to one another, as well as to ourselves . In this sense, literature may be considered a vehicle for the exploration and discovery of our world and the culture in which we live. It allows us to explore alternative realities, to view things from the perspective of someone completely different to us, and to reflect upon our own intellectual and emotional responses to the complex challenges of everyday life.

By studying literature, it is possible to develop an in-depth understanding of the ways that we use language to make sense of the world. According to the literary scholars, Andrew Bennett and Nicholas Royle, “Stories are everywhere,” and therefore, “Not only do we tell stories, but stories tell us: if stories are everywhere, we are also in stories.” From the moment each one of us is born, we are surrounded by stories — oftentimes these stories are told to us by parents, family members, or our community. Some of these stories are ones that we read for ourselves, and still others are stories that we tell to ourselves about who we are, what we desire, what we fear, and what we value. Not all of these stories are typically considered “literary” ones, but in this course, we will develop a more detailed understanding of how studying literature can enrich our knowledge about ourselves and the world in which we live.

If literature helps us to make sense of, or better yet question, the world and our place in it, then how does it do this? It may seem strange to suggest that literature performs a certain kind of work. However, when we think of other subjects, such as math or science, it is generally understood that the skills obtained from mastering these subjects equips us to solve practical problems. Can the same be said of literature?

To understand the kind of work that literature can do, it is important to understand the kind of knowledge that it provides. This is a very complex and widely debated question among literary scholars. But one way of understanding the kind of knowledge that can be gained from literature is by thinking about how we use language to make sense of the world each day. (1)

What does literature do?

Every day we use metaphors to describe the world. What is a metaphor? According to A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory , a metaphor is “a figure of speech in which one thing is described in terms of another.” You have probably heard the expressions, “Time is money” or “The administration is a train wreck.” These expressions are metaphors because they describe one less clearly defined idea, like time or the administration of an institution, in relation to a concept whose characteristics are easier to imagine.

A metaphor forms an implied comparison between two terms whereas a simile makes an explicit comparison between two terms using the words like or as — for example, in his poem, “A Red, Red Rose,” the Scottish poet Robert Burns famously announces, “O my Luve is like a red, red rose/That’s newly sprung in June.” The association of romantic love with red roses is so firmly established in our culture that one need only look at the imagery associated with Valentine’s Day to find evidence of its persistence. The knowledge we gain from literature can have a profound influence on our patterns of thought and behavior.

In their book Metaphors We Live By , George Lakoff and Mark Johnson outline a number of metaphors used so often in everyday conversation that we have forgotten that they are even metaphors, for example, the understanding that “Happy is up” or that “Sad is down.” Likewise, we might think “Darkness is death” or that “Life is light.” Here we can see that metaphors help us to recognize and make sense of a wide range of very complex ideas and even emotions. Metaphors are powerful, and as a result they can even be problematic.

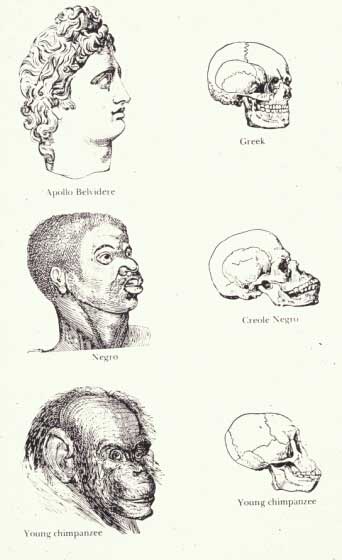

The author Toni Morrison has argued that throughout history the language used by many white authors to describe black characters often expresses ideas of fear or dread — the color black and black people themselves come to represent feelings of loathing, mystery, or dread. Likewise, James Baldwin has observed that whiteness is often presented as a metaphor for safety. (1)

Figure 1 is taken from a book published in 1857 entitled Indigenous Races of the Earth . It demonstrates how classical ideas of beauty and sophistication were associated with an idealized version of white European society whereas people of African descent were considered to be more closely related to apes. One of Morrison’s tasks as a writer is to rewrite the racist literary language that has been used to describe people of color and their lives.

By being able to identify and question the metaphors that we live by, it is possible to gain a better understanding of how we view our world, as well as our relationship to others and ourselves. It is important to critically examine these metaphors because they have very real consequences for our lives. (1)

- Authored by : Florida State College at Jacksonville. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Race and Skulls. Authored by : Nott, Josiah, and George R. Giddon. Provided by : Wikimedia Commons. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Races_and_skulls.png . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

What is Novel? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Novel definition.

A novel (NAH-vull) is a narrative work of fiction published in book form. Novels are longer than short stories and novellas, with the greater length allowing authors to expand upon the same basic components of all fictional literature—character, conflict , plot , and setting , to name a few.

Novels have a long, rich history, shaped by formal standards, experimentation, and cultural and social influences. Authors use novels to tell detailed stories about the human condition, presented through any number of genres and styles .

The word novel comes from the Italian and Latin novella , meaning “a new story.”

The History of Novels

Ancient Greek, Roman, and Sanskrit narrative works were the earliest forebears of modern novels. These include the Alexander Romances, which fictionalize the life and adventures of Alexander the Great; Aethiopica , an epic romance by Heliodorus of Emesa; The Golden Ass by Augustine of Hippo, chronicling a magician’s journey after he turns himself into a donkey; and Vasavadatta by Subandhu, a Sanskrit love story.

The first written novels tended to be dramatic sagas with valiant characters and noble quests, themes that would continue to be popular into the 20th century. These early novels varied greatly in length, with some consisting of multiple volumes and thousands of pages.

Novels in the Middle Ages

Literary historians generally recognize Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji as the first modern novel, written in 1010. It’s the story of a Japanese emperor and his relationship with a lower-class concubine. Though the original manuscript, consisting of numerous sheets of paper glued together in book-like format, is lost, subsequent generations wrote and passed down the story. Twentieth-century poets and authors have attempted to translate the confusing text, with mixed results.

Chivalric romantic adventures were the novels of choice during the Middle Ages. Authors wrote them in either verse or prose , but by the mid-15th century, prose largely replaced verse as the preferred writing technique in popular novels. Until this time, there wasn’t much distinction between history and fiction; novels blended components of both.

The birth of modern printing techniques in the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in a new market of accessible literature that was both entertaining and informative. As a result, novels evolved into almost exclusively fictional stories to meet this upsurge in demand.

Novels in the Modern Period

Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes’s 1605 work The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha , frequently shortened to Don Quixote , is the first major Western novel. The popularity of Don Quixote and subsequent novels paved the way for the Romantic literary era that began in the latter half of the 18th century. Romantic literature challenged the ideas of both the Age of Enlightenment and the Industrial Age by focusing on novels entrenched in emotion, the natural world, idealism, and the subjective experiences of commoners. Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, James Fenimore Cooper, and Mary Shelley all emerged as superstars of the Romantic era.

Naturalism was, in many ways, a rebellion against romanticism. Naturalism replaced romanticism in the popular literary imagination by the end of the 19th century. Naturalistic novels favored stories that examined the reasons for the human condition and why characters acted and behaved the way they did. Landmark novels of this era included The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, McTeague by Frank Norris, and Les Rougon-Macquart by Émile Zola.

Novels in the Present

Many popular novels of the 19th and 20th centuries started out as serializations in newspapers and other periodicals, especially during the Victorian era. Several Charles Dickens novels, including The Pickwick Papers , Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo , and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin began this way, before publishers eventually released them in single volumes.

In the 20th century, many themes of naturalism remained, but novelists began to create more stream-of-consciousness stories that highlighted the inner monologues of their central characters. Modernist literature, including the works of James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Virginia Woolf, experimented with traditional form and language.

The Great Depression, two World Wars, and the civil rights movement impacted the American novel in dramatic ways, giving the world stories of war and the fallout of war (Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms , Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front ); abject poverty and opulent wealth (John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath , F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby ); the Black American experience (Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man , Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God ); and countercultural revolution (Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest , Jack Kerouac’s On the Road ).

Changing sexual attitudes in the early and mid-20th century allowed authors to explore sexuality in previously unheard-of depth (Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer , Anaïs Nin’s Delta of Venus ). By the 1970s, second-wave feminism introduced a new type of novel that centered women as authors of their own fates, not as romantic objects or supporting players existing only in relation to men (Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook , Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying ).

Throughout the 20th century, the popularity of the novel grew to such an extent that publishers pushed books more firmly into individual genres and subgenres for better classification and marketing. This resulted in every genre having breakout stars who set specific standards for the works in their category. At the same time, there is literary fiction, often considered more serious because of its greater emphasis on meaning than genre fiction’s entertainment value. However, authors can blur the line between genre and literary fiction; see Stephen King’s novels, Lessing’s space fiction novels, and Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series, to mention just a few. Both genre and literary fiction have legions of devoted fans.

Serialized novels fell out of favor as the 20th century unfolded. Today, novels are almost always published in single volumes. The average wordcount for contemporary adult fiction is 70,000 to 120,000 words, which is approximately 230 to 400 pages.

The Many Types of Novels

Literary Novels

Literary novels are a broad category of books often regarded as having more intellectual merit than genre fiction. These novels are not as bound to formula, and authors feel greater freedom to experiment with style ; examine the psychology and motivations of their characters; and make commentary on larger social conditions or issues. Literary novels possess a certain amount of intellectualism and depth. Their language is rich, their descriptions detailed, and their characters unique and memorable. Examples of popular literary novels include The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt, Life After Life by Kate Atkinson, The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen, and A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara.

Genre Novels

In contrast to literary fiction, authors of genre novels tend to follow more of a basic plot formula, and they paint their characters with broader strokes and less nuance and complexity. Stories in this vein accentuate plot over character. The accepted norms of genre fiction allow a reader to pick up a certain kind of novel and, in general, know what to expect from it. However, the boundaries of genre fiction are considerably malleable, and you could just as easily classify many genre works as lofty as any literary novel. Also, many genre novels fall under more than one genre. Below are several major genres/subgenres of the contemporary novel.

Bildungsroman/Coming of Age

A bildungsroman is a coming-of-age novel that highlights a period of profound emotional, psychological, and/or spiritual growth for a young protagonist. Depending on the nature and depth of the story and the author’s goals, a bildungsroman can skew toward a young readership or an adult one. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain are two notable bildungsroman novels.

Children and Young Adult

More of a catchall term than a genre, children and young adult novels center on young protagonists having formative experiences. Plots deal with issues and challenges of special interest to young readers, such as friendship, bullying, prejudice, school and academic life, gender roles and norms, changing bodies, and sexuality.

Classic children and young adult novels include Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. More recently, some young people’s literature has had a crossover appeal to adult audiences, with the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling and The Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins garnering legions of fans both young and old.

Death and romance are major plot points in gothic novels. The supernatural, family curses, stock characters like Byronic heroes and innocent maidens, and moody settings like castles or monasteries usually figure prominently in the storylines. Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë and The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux are two beloved gothic novels.

Historical novels take place in the past, where plots typically involve a specific historical event or era. The novel may or may not include fictionalized versions of real people. Authors of historical fiction often conduct in-depth research of the times about which they write to provide readers with a vivid reimagining of what life was like. Popular historical novels include The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett, The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory, and Roots by Alex Haley.

Authors of horror novels write plots and characters intended to scare or disgust the reader. The stories frequently incorporate elements of the supernatural and/or psychological components designed to startle the reader and get them to question what they know about the characters. The Shining by Stephen King, The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson, and Dracula by Bram Stoker are perennial favorites of this genre.

Mysteries tell stories of crimes and the attempts to solve them. There are multiple types of mystery novels, such as noir, police procedurals, professional and amateur detective fiction, legal thrillers, and cozy mysteries. Examples include Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Stieg Larsson, and Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie.

Picaresque novels feature the adventures of impish, lowborn but likeable heroes who barrel through a variety of different encounters, living by their wits in corrupt or oppressive societies. Picaresque novels reached their peak of popularity in Europe from the 16th to 19th centuries, but authors still occasionally write them today. The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling , by Henry Fielding is a classic picaresque, while A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole is a more recent one.

Roman à Clef

A roman à clef is an autobiographical novel, which fictionalizes real people and events. An author of a roman à clef has the freedom to write about controversial or deeply personal, secretive topics without technically exposing anyone or anything—or exposing themselves to charges of libel. They can also imagine different scenarios and resolutions for real-life situations. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath and The Devil Wear Prada by Lauren Weisberger are both roman à clefs.

Romance novels are love stories. The main plot usually features the dramatic courtship of two characters as they discover their feelings and attempt to be together. An antagonist frustrates these attempts but rarely wins, which means romance novels almost always end in a happily-ever-after.

Contemporary romance, historical romance, inspirational romance, and LGBTQ romance are just a few of the subgenres on the market. Examples of romance novels include A Knight in Shining Armor by Jude Deveraux, Outlander by Diana Gabaldon, and The Notebook by Nicholas Sparks.

A satirical novel humorously criticizes someone or something. The author will typically employ exaggerated plots and characters to underscore a specific fallibility or corruption. Common targets include public figures, laws and government policies, and social norms. Satires can possess considerable power by using humor to comment on societal or human flaws. Animal Farm by George Orwell and Catch-22 by Joseph Heller are masterworks of the genre.

Science Fiction and Fantasy

Science fiction novels deal with emerging or new technologies, space exploration, futurism, and other speculative elements. Similarly, fantasy novels integrate elements that defy known scientific laws, with magic and folklore often playing a major role in the worlds and characters created by the author. Science fantasy novels are a subgenre that combine these two forms. The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K. Le Guin and The War of the Worlds are prime examples of science fiction, while The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien and A Game of Thrones by George R.R. Martin are enduring fantasy classics.

The Great American Novel

A uniquely American phenomenon is what novelist John William DeForest called the “Great American Novel.” The definition of this term is open to some interpretation, but, in general, it refers to a novel that captures the spirit and experience of life in the United States and the essence of the national character. Since DeForest coined the term in 1868, many novels have claimed this title, though there’s no single organization or institution that bestows such a designation. Books cited as a Great American Novel include Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Novels’ Different Styles and Formats

Authors can write novels using any number of techniques. A straightforward narrative that utilizes a conventional plot is just one approach. Others include:

An epistolary novel tells its story through fictional letters, newspaper and magazine clippings, diary entries, emails, and other documents. The Color Purple by Alice Walker and Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos are examples of epistolary novels.

Experimental

An experimental novel plays with traditional form, plot, character, and/or voice . The author might invent techniques or words that present their story in innovative ways. Such works are sometimes challenging and exhilarating for readers, and they inspire looking at the novel as an ever-evolving art form. Popular experimental novels include Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson and Ella Minnow Pea by Mark Dunn.

Modernism as a distinct literary form flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernist fiction challenged conventional ideas of structure and linear storytelling and is a precursor to today’s experimental fiction. Individualism, symbolism , absurdity, and wild experimentation were common in modernist novels. Ulysses by James Joyce and Nightwood by Djuna Barnes are quintessential modernist novels.

Philosophical

Philosophical novels are, more than anything, novels of ideas. They put forth moral, theoretical, and/or metaphysical ideas, assertions, and speculations. They’re not necessarily academic works; they still include plots and characters, but these exist as symbols of a larger philosophical theme. Examples of philosophical novels include The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera and Under the Net by Iris Murdoch.

Sentimental

Sentimental novels tug at the heartstrings. Authors design these novels to appeal to readers’ sympathy and compassion. As its own literary form, sentimental novels—like The Sorrows of Young Werther by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded by Samuel Richardson—abounded during the 18th century. Stella Dallas by Olive Higgins Prouty and Beaches by Iris Rainer Dart are more recent novels written in this style.

Novels written in verse are rare in today’s literary landscape, but they have their roots as far back as The Iliad and The Odyssey . The narratives blend fiction and poetry by telling a fictional tale through traditional verses of rhythms and stanzas . Two contemporary verse novels are Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson and Sharp Teeth by Toby Barlow.

The Function of Novels

Compared to short stories and novellas, novels give authors the opportunity to create more detailed plots, characters, and worlds. An author can delve more fully into the trajectory of the story and the evolution of the characters, presenting struggles, conflicts , and, ultimately, resolutions. For readers, novels also entertain and educate. They can be an escape and a leisure activity, one that engages the mind in a way that other forms of entertainment cannot. They are instructive as well, informing readers about society, history, morality, and/or aspects of the human condition, depending on the novel.

Novels have never been entirely without controversy. They give authors an outlet to create imaginative stories, but they can also function as commentaries on the societies that publish them. Governments, schools, and other authority figures and institutions might see such novels as subversive and even dangerous. This has led many countries, including the United States, to ban novels deemed offensive. Novels banned by authorities at one point or another include The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence, and Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin.

Notable Novelists

- Bildungsroman/Coming of Age: Betty Smith, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

- Children and Young Adult: Laura Ingalls Wilder, Little House on the Prairie

- Epistolary: Marilynne Robinson, Gilead

- Experimental: Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

- Gothic: Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; The Modern Prometheus

- The Great American Novel: Toni Morrison, Beloved

- Historical: Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

- Horror: Ira Levin, Rosemary’s Baby

- Literary: Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

- Modernist: Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

- Mystery: Paula Hawkins, The Girl on the Train

- Philosophical: Hermann Hesse, Siddhartha

- Picaresque: William Makepeace Thackeray, The Luck of Barry Lyndon

- Roman à Clef: Carrie Fisher, Postcards from the Edge

- Romance: Nora Roberts, Northern Lights

- Satire: Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

- Science Fiction and Fantasy: Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower

- Sentimental: Maria Susanna Cummins, The Lamplighter

- Verse: Allan Wolf, The Watch That Ends the Night: Voices from the Titanic

Examples in Literature

1. Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

Don Quixote is a satire of the chivalric romances popular during Cervantes’s time. Middle-aged Don Quixote of 16th-century La Mancha, Spain, spends his life reading these epic tales. They inspire him to revive what he sees as the lost concept of chivalry, so he picks up a sword and shield and becomes a knight. His goal is to defend the defenseless and eliminate evil. His partner in this endeavor is a poor farmer named Sancho Panza. They ride through Spain on their horses, searching for adventure, and Don Quixote falls in love with a peasant named Dulcinea. Don Quixote and Sancho embark upon multiple quests to restore lost honor to the nation. Ultimately, Don Quixote returns home, denounces his knighthood, and dies of fever, bringing an end to chivalry.

2. Jane Austen, Sense and Sensibility

Sense and Sensibility is a classic Romantic -era novel that also contains some satirical elements that wittily criticize the social decorum of the time. In 1790s England, Henry Dashwood’s death leaves his wife and three daughters nearly destitute. The older daughters, Elinor and Marianne, realize their only hope for saving the family is to find suitable husbands.

Sensible Elinor falls for Edward Ferrars, while romantic Marianne feels torn between dashing John Willoughby and sturdy Colonel Brandon. After recovering from a fever, Marianne realizes Colonel Brandon is the steady force she desires, not the impetuous Willoughby, and after some initial confusion, Elinor learns that Edward is in love with her. The young women marry their suitors, and the two couples live as neighbors.

3. F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby is a novel that examines the American Dream, class inequality, and themes of love and loss. Nick Carraway arrives on Long Island in the spring of 1922, moving into a cottage next to a sprawling estate owned by elusive millionaire Jay Gatsby. Known for hosting lavish parties that he never attends, Gatsby is an almost mythic figure in the community. Nick learns that Gatsby is passionately in love with Daisy, the wife of Nick’s old college friend Tom, who has a mistress named Myrtle.

Nick wrangles an invitation to one of Gatsby’s parties, and the two become friends. Through Nick, Gatsby arranges a meeting with Daisy, beginning an intense affair. One night, Gatsby and Daisy are driving home and accidently run into and kill Myrtle. Daisy was the one driving, but Gatsby takes the blame, and Myrtle’s husband kills him. The entire experience leaves Nick cold toward New York life, feeling that he, Gatsby, Daisy, and Tom never fit in with this world.

4. Toni Morrison, Beloved

Beloved is an historical novel that delves into the lasting psychological effects of slavery. Sethe, a formerly enslaved woman, lives with her daughter Denver in 1870s Cincinnati. Paul D, a man enslaved with Sethe on the Sweet Home plantation, arrives at their door, and not long after, a mysterious young woman—only identifying herself as Beloved—arrives as well. Sethe eventually believes that Beloved is the incarnation of her youngest daughter, who she killed to prevent her capture and sale into slavery.

Sethe grows obsessed with Beloved, losing her job, pushing away Paul D, and alienating Denver in the process. Denver reaches out to the local Black community and gets a job working for a white family. When Denver’s employer comes to pick her up for her first day of work, Sethe, by this time delirious and delusional, thinks he’s a slavecatcher coming yet again to take Beloved. She attempts to attack him but is held back by the townspeople, an act that seemingly sets Beloved free, and the mysterious young woman disappears in a cloud of butterflies. Denver supports the family, and Paul D returns to Sethe and reminds her of her worth.

Further Resources on Novels

Jane Friedman answers the question, What is a literary novel?

The Guardian has a list of their picks for the 100 best novels written in English .

Literary Hub offers insights into the Great American Novel .

Writer’s Digest shares the 10 rules of writing a novel .

Writing coach Vivian Reis coaches beginners through the writing of a novel .

Related Terms

- Point of View

- Romanticism

- Science Fiction

Join Discovery, the new community for book lovers

Trust book recommendations from real people, not robots 🤓

Blog – Posted on Wednesday, Oct 13

The 100 best classic books to read.

Ever been caught up in a conversation about books and felt yourself cringe over your literary blind spots? Classic literature can be intimidating, but getting acquainted with the canon isn't just a form of torture cooked up by your high school English teacher: instead, an appreciation for the classics will help you see everything that's come since in a different light, and pick up on allusions that you'll begin to notice everywhere. Above all, they're just great reads — they've stood the test of time for a reason!

If you've always wanted to tackle the classics but never knew quite where to begin, we've got you covered. We've hand-selected 100 classic books to read, written by authors spanning continents and millennia. From love stories to murder mysteries, nonfiction to fantasy, there's something for everybody.

1. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

This milestone Spanish novel may as well be titled 100 Years on Everyone’s Must-Read List — it’s just a titan in the world literature canon. We could go on about its remarkable narrative technique, beguiling voice, and sprawling cast of characters spanning seven generations. Its famous first line may be all that’s needed to win you over: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

2. The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Newland Archer, one of 1900s New York’s most eligible bachelors, has been looking for a traditional wife, and May Welland seems just the girl — that is until Newland meets entirely unsuitable Ellen Olenska. He must now choose between the two women — and between old money prestige and a value that runs deeper than social etiquette.

3. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

This allegorical tale, often recommended as a self-help book , follows young shepherd Santiago as he journeys to Egypt searching for a hidden treasure. A parable telling readers that the universe can help them realize their dreams if they only focus their energy on them, Coelho’s short novel has endured the test of time and remains a bestseller today.

Looking for something new to read?

Trust real people, not robots, to give you book recommendations.

Or sign up with an email address

4 . All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

Erich Maria Remarque’s wartime classic broke ground with its unflinching look at the human cost of war through the eyes of German soldiers in the Great War. With a lauded 1930 film adaptation (only the third to win Best Picture at the Oscars), All Quiet on the Western Front remains as powerful and relevant as ever.

5 . American Indian Stories, Legends, and Other Writings by Zitkála-Šá

Zitkála-Šá’s stories invite readers into the world of Sioux settlement, sharing childhood memories, legends, and folktales, and a memoir account of the Native American author ’s transition into Western culture when she left home. Told in beautiful, fluid language, this is a must-read book.

The World's Bestselling Mystery \'Ten . . .\' Ten strangers are lured to an isolated island mansion off the Devon coast by a mysterious \'U.N. Owen.\' \'Nine . . .\' At dinner a recorded message accuses each of them in turn of having a guilty secret, and by the end of the night one of the guests is dead. \'Eight . . .\' Stranded by a violent storm, and haunted by a nursery rhyme counting down one by one . . . one by one they begin to die. \'Seven . . .\' Who among them is the killer and will any of them survive?

6 . And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

First, there were ten who arrived on the island. Strangers to one another, they shared one similarity: they had all murdered in the past. And when people begin dropping like flies, they realize that they are the ones being murdered now. An example of a mystery novel done right, this timeless classic was penned by none other than the Queen of Mystery herself .

7 . Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

Tolstoy’s celebrated novel narrates the whirlwind tale of Anna Karenina. She’s married to dull civil servant Alexei Karenin when she meets Count Vronsky, a man who changes her life forever. But an affair doesn’t come without a moral cost, and Anna’s life is soon anything but blissful.

8 . The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath’s only novel follows the young, ambitious Esther Greenwood, who falls into a depression after a directionless summer, culminating in a suicide attempt. But even as Esther survives and receives treatment, she continues wondering about her purpose and role in society — leading to much larger questions about existential fulfillment. Poetically written and stunningly authentic, The Bell Jar continues to resonate with countless readers today.

9. Beloved by Toni Morrison

Many books are said to have helped shape the world — but only a few can really stake that claim. Toni Morrison’s Beloved is one of them. One of the great literary luminaries of our time, her best-known novel is the searingly powerful story of Sethe, who was born a slave in Kentucky. Though she’s since escaped to Ohio, she is haunted by her dead baby, whose tombstone is engraved with one word: Beloved .

10 . The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories by Angela Carter

Before the recent fad of feminist retellings of fairy tales, there was The Bloody Chamber . But Angela Carter’s retold tales, including twisted versions of Little Red Riding Hood and Beauty and the Beast, are more than just feminist: they’re original, darkly irreverent, and fiercely independent. This classic book is exactly what you’d expect from the author who inspired contemporary masters like Neil Gaiman, Sarah Waters, and Margaret Atwood.

11. Breakfast at Tiffany's by Truman Capote

Though the title evokes Audrey Hepburn, this novella came first — and the literary Holly Golightly is a very different creature from the 'good-time girl' who falls for George Peppard. Clever and chameleonic, she crafts her persona to fit others’ expectations, chasing her own American Dream while letting men think they can have it with her… only to slip through their fingers. A fascinating character study and a triumph of Capote’s wit and humanity.

12. Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Set in the opulent inter-war era in England, Brideshead Revisited chronicles the increasingly complex relationship between Oxford student Charles Ryder, his university chum Sebastian, whose noble family they visit at their grand seat of Brideshead. A lush, nostalgic, and passionate rendering of a bygone era of English aristocracy.

13. A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

Welcome to Theoretical Physics 101. If it sounds daunting, you aren’t alone, and Stephen Hawking does a beautiful job guiding layperson readers through complex subjects. If you’re keen to learn more about such enigmas as black holes, relativity theory, quantum mechanics, and time itself, this is a perfect first taste.

14. The Call of the Wild (Reader's Library Classics) by Jack London

London's American classic is the bildungsroman of Buck: a St. Bernard/Scotch Collie mix who must adapt to life as a sled dog after a domesticated upbringing. Thrown into a harsh new reality, he must trust his instincts to survive. When he falls into the hands of a wise, experienced outdoorsman, will he become loyal to his new master or finally answer the call of the wild?

15. The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Salinger’s angsty coming-of-age tale is an English class cornerstone for a good reason. The story follows Holden Caulfield, a 17-year-old boy fed up with prep school “phonies.” Escaping to New York in search of authenticity, he soon discovers that the city is a microcosm of the society he hates. Relentlessly cynical yet profoundly moving, The Catcher in the Rye will strike a chord not just with Holden’s fellow teens but with earnest thinkers of all ages.

16. A Christmas Carol (Bantam Classics) by Charles Dickens

If you’re not acquainted with Dickens , then his evergreen Christmastime classic is the perfect introduction. Not only is it one of his best-loved works, but it’s also a slim 104 pages — a true yuletide miracle from an author with a tendency towards the tome! This short length means it’s the perfect book with which to cozy up in winter, just when you want to feel that warm holiday glow.

17. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

En route to his wedding, merchant sailor Edmond Dantès is shockingly accused of treason and thrown in prison without cause. There, he learns the secret location of a great fortune — knowledge that incites him to escape his grim fortress and take revenge on his accusers. With peerlessly propulsive prose, Dumas spins an epic tale of retribution, jealousy, and suffering that deserves every page he gives it.

18. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

A masterclass in character development , the very title of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment is essentially an idiom for 'epic literature.' It centers around Raskolnikov, an unremarkable man who randomly murders someone after convincing himself that his motives are lofty enough to justify his actions. It turns out that it’s never that simple, and his conscience begins to call to him more and more.

19. Dangerous Liaisons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

The inspiration for the seminal 90s teen drama Cruel Intentions , Laclos's epistolary classic is a heady pre-revolutionary cocktail of sex and scandal that paints a damning portrait of high society. Laclos expertly plays with form and structure, composing a riveting narrative of letters passed between the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont — aristocratic former lovers who get in over their heads when they start playing with people's hearts.

20. The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes

In this highly atmospheric book, Fuentes draws the reader in with hypnotic, visceral descriptions of the final hours of its title character: a multifaceted tycoon, revolutionary, lover, and politician. As with many classic books, death here symbolizes corruption — yet it’s also impossible to ignore as a physical reality. As well as being a powerful statement on mortality, it's a moving history of the Mexican Revolution and a landmark in Latin-American literature .

21. Diary of a Madman, and other stories by Lu Xun

This collection is a modern Chinese classic containing chilling, satirical stories illustrating a time of great social upheaval. With tales that ask questions about what constitutes an individual's life, ordinary citizens' everyday experiences blend with enduring feudal values, ghosts, death, and even a touch of cannibalism.

22. Samuel Pepys The Diaries by Samuel Pepys

Best known for his recording the Great Fire of London, Samuel Pepys was a man whose writings have provided modern historians with one of the greatest insights into 17th-century living. The greatest hits of his diary include eyewitness accounts of the restoration of the monarchy and the Great Plague. The timelessness of this book, however, is owed to the richness of Pepys's day-to-day drama, which he records in unsparing, lively detail.

23 . A Doll's House and Other Plays (Penguin Classics) by Henrik Ibsen

Ibsen’s A Doll’s House is a powerful play starring the seemingly frivolous housewife Nora. Her husband, Torvald, considers her to be a silly “bird” of a companion, but in reality, she’s got a much firmer grasp on the hard facts of their domestic life than he does. Readers will celebrate as she finds the voice to speak her true thoughts.

24. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Entranced by tales of chivalry, a minor nobleman reinvents himself as a knight. He travels the land jousting giants and delivering justice — though, in reality, he’s tilting at windmills and fighting friars. And while Don Quixote lives out a fantasy in his head, an imposter puts it to the page, further blurring the line between fiction and reality. Considered by many to be the first modern novel, Don Quixote is undoubtedly the work of a master storyteller.

25. The Dream of The Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin

A treasured classic of Chinese literature, Dream of the Red Chamber is a rich, sprawling text that explores the darkest corners of high society during the Qing Dynasty. Focusing on two branches of a fading aristocratic clan, it details the lives of almost forty major characters, including Jia Baoyu, the heir apparent whose romantic notions may threaten the family's future.

26. Dune by Frank Herbert

A dazzling epic science fiction classic, Dune created a now-immortalized interstellar society featuring a conflict between various noble families. On the desert planet of Arrakis, House Atreides controls the production of a high-demand drug known as "the spice". As political conflicts mount and spice-related revelations occur, young heir Paul Atreides must push himself to the absolute limit to save his planet and his loved ones.

27. The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy became the blueprint for countless fantasy series , and this first installment is its epic start. In The Fellowship of the Ring, we meet Frodo Baggins and his troupe of loyal friends, all of whom embark on a fateful mission: to destroy the One Ring and its awful powers forever.

28. The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan’s disruptive feminist text sheds light on the midcentury dissatisfaction of homemakers across America. Her case studies of unhappy women relegated to the domestic sphere, striving for careers and identities beyond the home, cut deep even now — and in retrospect, were a clear catalyst for second-wave feminism in the United States.

29. Frankenstein by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

Shelley’s hugely influential classic recounts the tragic tale of Victor Frankenstein: a scientist who mistakenly engineers a violent monster. When Victor abandons his creation, the monster escapes and threatens to kill Victor’s family — unless he’s given a mate. Facing tremendous moral pressure, Victor must choose: foster a new race to possibly destroy humanity, or be responsible for the deaths of everyone he’s ever loved?

30. Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin

A defining entry in the LGBTQ+ canon , Giovanni’s Room relates one man’s struggle with his sexuality, as well as the broader consequences of the toxic patriarchy. After David, our narrator, has traveled to France to find himself, he begins a relationship with messy, magnetic Giovanni — the perfect foil to David’s safe, dull girlfriend. As more trouble arises, David agonizes over who he is, what he wants, and whether it is even possible to obtain it in this world.

31. The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing

This inventive meta novel is the first of Lessing’s “inner space” works, dealing with ideas of mental and societal breakdown. It revolves around writer Anna Wulf, who hopes to combine the notebooks about her life into one grand narrative. But despite her creative strides, Anna has irreparably fragmented herself — and working to re-synthesize her different sides eventually drives her mad.

32. Goodbye To All That by Robert Graves

Few people possess enough raw material to pen a memoir at the age of 34. Robert Graves — having already lived through the First World War and the seismic shifts it sparked in English society and sensibilities — peppers his sober account of social and personal turmoil with moments of surprising levity. Graves would later go on to write I, Claudius, a novel of the Roman Empire that is considered one of the greatest books ever written.

33. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Following one Oklahoma family’s journey out of the Dust Bowl in search of a better life in California, Steinbeck’s classic is a vivid snapshot of Depression-era America, and about as devastating as it gets. Both tragic and awe-inspiring, The Grapes of Wrath is widely considered to be Steinbeck's best book and a front-runner for the title of The Great American Novel.

34. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

When talking of the Great American Novel, you cannot help but mention this work by F. Scott Fitzgerald. More than just a champagne-soaked story of love, betrayal, and murder, The Great Gatsby has a lot to say about class, identity, and belonging if you scratch its surface. You probably read this classic book in high school, but a return visit to West Egg is more than justified.

35. The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

Meet John Singer, a deaf and nonverbal man who sits in the same café every day. Here, in the deep American South of the 1930s, John meets an assortment of people and acts as the silent, kind keeper of their stories — right up until an unforgettable ending that will blow you away. It’s hard to believe McCullers was only 23 when she penned this Southern gothic classic.

36. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon

An epic work that befits its lengthy title, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire chronicles thirteen centuries of Roman rule. It chronicles its leaders, conflicts, and the events that led to its collapse— an outcome that Gibbon lays at the feet of Christianity. This work is an ambitious feat at over six volumes, though one that Gibbon pulls off with great panache.

37. The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

Arthur Dent is an Englishman, an enjoyer of tea — and the only person to survive the destruction of the Earth. Accompanied by an alien author, Dent must now venture into the intergalactic bypass to figure out what’s going on. Though by no means the first comedic genre book, Douglas Adams’s masterpiece certainly popularized the idea that science fiction doesn't have to be earnest and straight-faced.

38. The Hound of the Baskervilles by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Arthur Conan Doyle’s world-famous detective needs no introduction. Mythologized in film and television many times over by now, this mystery of a diabolical hound roaming the moors in Devon is perhaps Sherlock Holmes’s most famous adventure.

39. The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Few first-time novelists have had the kind of impact and success enjoyed by Isabel Allende with her triumphant debut. Found at the top of pretty much every list of ‘best sweeping family sagas,’ The House of the Spirits chronicles the tumultuous history of the Trueba family, entwining the personal, the political, and the magical.

40. How to Win Friends & Influence People by Dale Carnegie

A perennial personal development staple, How to Win Friends and Influence People has been flying off the shelves since its release in 1936. Full of tried-and-true tips for garnering favor in both professional and personal settings, you’ll want to read the classic book that launched the entire self-help industry.

41. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

From a small Southern town to San Francisco, this landmark memoir covers Maya Angelou’s childhood years growing up in the United States, facing daily prejudice, racism, and sexism. Yet what shines the brightest on every page is Maya Angelou’s voice — which made the book an instant classic in 1969 and has endured to this day.

42. I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

You don’t have to be a sci-fi buff (or a Will Smith fan) to understand I, Robot’s iconic status. But if you are one, you’ll know the impact Isaac Asimov’s short story collection has had on subsequent generations of writers. Razor-sharp and thought-provoking, these tales of robotic sentience are still deeply relevant today.

43. If This Is a Man by Primo Levi

Spare, unflinching, and horrifying, If This Is a Ma n is Italian-Jewish writer Primo Levi’s autobiographical account of life under fascism and his detention in Auschwitz. It serves as an invaluable historical document and a powerful insight into the atrocities of war, making for a challenging but essential read.

44. Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

From Ellison’s exceptional writing to his affecting portrayal of Black existence in America, Invisible Man is a true masterpiece. The book’s unnamed narrator describes experiences ranging from frustrating to nightmarish, reflecting on the “invisibility” of being seen only as one’s racial identity. Weaving in threads of Marxist theory and political unrest, this National Book Award winner remains a radical, brilliant must-read for the 21st century.

45. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Like a dark, sparkling jewel passed down through generations, Charlotte Brontë’s exquisite Gothic romance continues to be revered and reimagined more than 170 years after its publication. Its endurance is largely thanks to the intensely passionate and turbulent relationship between headstrong heroine Jane and the mysterious Mr. Rochester — a romance that is strikingly modern in its sexual politics.

46. The Journey to the West by Wu Cheng'en

Journey to the West is an episodic Chinese novel published anonymously in the 16th century and attributed to Wu Cheng’en. Today, this beloved text — a rollicking fantasy about a mischievous, shape-shifting monkey god and his fallen immortal friends — is the source text for children’s stories, films, and comics. But this classic book is also an insightful comic satire and a monument of literature comparable to The Canterbury Tales or Don Quixote.

47. Kindred by Octavia E. Butler

A science fiction novel by one of the genre's greats, Kindred asks the toughest “what if” question there is: What if a modern black woman was transported back in time to antebellum Maryland? Octavia Butler sugarcoats nothing in this incisive, time-traveling inquisition into race and racism during one of the most horrifying periods in American history.

49. The Lonely Londoners by Samuel Selvon

The Lonely Londoners occupies a unique historical position as one of the earliest accounts of the Black working-class in 20th-century Britain. Selvon delves into the lives of immigrants from the West Indies, most of whom feel disillusioned and listless in London. But with its singular slice-of-life style and humor, The Lonely Londoners is hardly a tragic novel — only an unflinchingly honest one.

50. Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Another high school English classic, Lord of the Flies recounts the fate of a group of young British boys stranded on a desert island. Though they initially attempt to band together, rising tensions and paranoia lead to in-fighting and, eventually, terrible violence. The result is a dark cautionary tale against our own primitive brutality — with the haunting implication that it's closer to the surface than we'd like to think.

51. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

Flaubert’s heroine Emma Bovary is the young wife of a provincial doctor who escapes her banal existence by devouring romance novels. But when Emma decides she remains unfulfilled, she starts seeking romantic affairs of her own — all of which fail to meet her expectations or rescue her from her mounting debt. Though Flaubert’s novel caused a moral outcry on publication, its portrayal of a married woman’s affair was so realistic, many women believed they were the model for his heroine.

52. The Man Who Would Be King by Rudyard Kipling

This short novella tells the story of two British men visiting India while the country is a British colony. Swindlers and cheats, the men trick their way to Kafiristan, a remote region where one of them comes to be revered as king. A cautionary tale warning against letting things go to your head, this funny and absurd read has also been made into a classic film starring Michael Caine and Sean Connery.

53. Middlemarch by George Eliot

Subtitled A Study of Provincial Life , this novel concerns itself with the ordinary lives of individuals in the fictional town of Middlemarch in the early 19th century. Hailed for its depiction of a time of significant social change, it also stands out for its gleaming idealism, as well as endless generosity and compassion towards the follies of humanity.

54. Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie

Born in the first hour of India’s independence, Saleem Sinai is gifted with the power of telepathy and an extraordinary sense of smell. He soon discovers that there are 1,001 others with similar abilities — people who can help Saleem build a new India. The winner of the Booker prize in 1981, Salman Rushdie’s groundbreaking novel is a triumphant achievement of magical realism .

55. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

Moby-Dick is more than the story of a boy on-board a whaling ship, more than an ode to marine lore and legend, and even more than a metaphysical allegory for the struggle between good and evil. Herman Melville’s “Great American Novel” is a masterful study of faith, obsession, and delusion — and a profound social commentary born from his lifelong meditation on America. The result will fill you with wonder and awe.

56. My Antonia by Willa Cather

Willa Cather’s celebrated classic about life on the prairie, My Ántonia tells the nostalgic story of Jim and Ántonia, childhood friends and neighbors in rural Nebraska. As well as charting the passage of time and the making of America, it’s a book that fills readers with wonder and a warm feeling of familiarity.

57. The Name Of The Rose by Umberto Eco

Originally published in Italian, The Name of the Rose is one of the bestselling books of all time — and for good reason. Umberto Eco plots a wild ride from start to finish: an intelligent murder mystery that combines theology, semiotics, empiricism, biblical analysis, and layers of metanarratives that create a brilliant labyrinth of a book.

58. The Nether World by George Gissing

A masterpiece of realism, The Nether World forces the reader to spend time with the type of marginalized people routinely left out of fiction: the working class of late 19th century London, a group whose many problems are intertwined with money. Idealistic in its pessimism, this fantastic novel insists that life is much more demanding than fiction lets show.

59. Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

George Orwell’s story of a heavily surveilled dystopian state was heralded as prescient and left a lasting impact on popular culture and language (“Room 101”, “Big Brother,” and “Doublethink” were all born in its pages, to name a few). Just read it, if only to recognize its references, which you’ll begin to notice everywhere .

60. North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell

Uprooted from the South, a pastor's daughter, Margaret Hale, finds herself living in an industrial town in England's North. She encounters the suffering of the local mill workers and the mill owner John Thornton — and two very different passions ignite. In North and South, Elizabeth Gaskell fuses personal feeling with social concern, creating in the process a heroine that feels original and strikingly modern.

61. The Odyssey by Homer

This timeless classic has the heart-racing thrills of an adventure story and the psychological drama of an intricate family saga. After ten years fighting in a thankless war, Odysseus begins the long journey home to Ithaca — where his wife Penelope struggles to hold off a horde of suitors. But with men and gods standing in their way, will Odysseus and Penelope ever be reunited?

62. The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway ’s career culminated with The Old Man and the Sea, the last book he published in his lifetime. This ocean-deep novella has a deceptively simple premise — an aging fisherman ventures out into the Gulf Stream determined to break his unlucky streak. What follows is a battle that’s small in scale but epic in feeling, rendered in Hemingway’s famously spare prose.

63. On The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

Questioning the idea of a Creator — and therefore challenging the beliefs of most of the Western world — in The Origin of Species , Darwin explored a theory of evolution based on laws of natural selection. Not only is this text still considered a groundbreaking scientific work, but the ideas it puts forward remain fundamental to modern biology. And it’s totally readable to boot!

64. One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest by Ken Kesey

The subjective nature of “sanity,” institutional oppression, and rejection of authority are just a few of the issues tackled in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest . The rebellious Randle McMurphy is this story’s de facto hero, and his clashes with the notorious Nurse Ratched have not only inspired a host of spin-offs but arguably a whole movement of fiction related to mental health.

65. One Thousand and One Nights by Anonymous

Embittered by his first wife’s infidelity, King Shahryar takes a new bride every night and beheads her in the morning — until Scheherazade, his latest bride, learns to use her imagination to stave off death. In this collection of Arabic folk tales, the quick-witted storyteller Scheherazade demonstrates the power of a good cliffhanger — on both the king and the reader!

66. Orientalism by Edward W. Said

An intelligent critique of the way the Western world perceives the East, Orientalism argues that the West’s racist, oppressive, and backward representation of the Eastern world is tied to imperialism. Published in 1978, Edward Said’s transformative text changed academic discourse forever.

67. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Thanks to the wit and wisdom of Jane Austen, the love story of Elizabeth Bennet and Fitzwilliam Darcy (pioneers of the enemies-to-lovers trope) is not merely a regency romance but a playful commentary on class, wealth, and the search for self-knowledge in a world governed by strict etiquette. Light, bright, and flawlessly crafted, Pride and Prejudice is an Austen classic you’re guaranteed to love.

68. The Princesse de Clèves by Madame de Lafayette

Often called the first modern novel from France, The Princesse de Cleves is an account of love, anguish, and their inherent inseparability: an all-too-familiar story, despite the 16th-century setting. Though the plot is simple — an unrequited love, unspoken until it’s not — Madame de Lafayette pours onto the pages a moving and profound analysis of the fragile human heart.

69. The Reader by Bernhard Schlink

The Reader is set in postwar Germany, a society still living in the shadow of the Holocaust. The book begins with an older woman’s relationship with a minor, though it isn’t even the most shocking thing that happens in this novel. Concerned with disconnection and apathy, Schlink’s book grapples with the guilty weight of the past without flinching from the horror of the present.

70. Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” Du Maurier’s slow-burning mystery has been sending a chill down readers’ spines for decades, earning its place in the horror hall of fame. It’s required reading for any fan of the genre, but reader beware: this gorgeously gothic novel will keep you up at night.

71. A Room of One's Own by Virginia Woolf

A mainstay of feminist literature , A Room of One’s Own experimentally blends fiction and fact to drill down into the role of women in literature as both subjects and creatives. Part critical theory, part rallying cry, this slender book still packs a powerful punch.

72. Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih

Described by Edward Said as one of the great novels in the oeuvre of Arabic books, Season of Migration to the North is the revolutionary narrative of two men struggling to re-discover their Sudanese identities following the impact of British colonialism. Some compare it to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness , but it stands tall in its own right.

73. The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir

A foundational feminist text , Simone de Beauvoir's treatise The Second Sex marked a watershed moment in feminist history and gender theory. It rewards the efforts of those willing to traverse its nearly 1,000 pages with eye-opening truths about gender, oppression, and otherness.

74. The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins