Problem Solving in Crisis Management

By Michael Curran-Hays , Kepner-Tregoe

- Leadership Fundamentals Meet leadership challenges using the logical thinking process leaders use to gather, organize and analyze information before taking action. Learn More

Every week we see in the news another example of companies in crisis – customer service crises, critical IT system issues, management crisis and business continuity issues caused by natural disasters. Customers and shareholders may quickly forget the details of what caused the crisis but how you handle the situation will be etched into their memory and shape their perception of you long into the future. For many companies, how a crisis is handled could mean the difference between a healthy recovery and going out of business.

You may not be able to predict when a crisis will occur, or even what it will be – but that doesn’t prevent you from planning ahead and ensuring your leaders and organization know what to do when crisis hits. At its core, a crisis is just a big problem and all the basic problem-solving skills your employees have learned can be applied. There are a few things, however, that make a crisis unique and require you to up your problem-solving game to the next level.

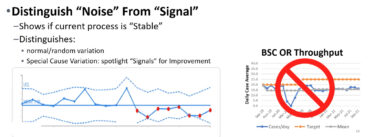

Impact to the organization

In a non-crisis situation, the primary focus of your organization is resolving the issue and getting business back to normal. A crisis situation is different in that it brings with it an added level of complexity related to managing both the issue and long-term impacts to the organization. These impact may be operational, financial or reputational and in most cases a crisis will involve more than one. Quickly assessing the impact of the crisis (and re-assessing frequently) will likely influence (if not dictate) the choices you make, how you communicate and the urgency you place on resolving the issue.

Reputational impact in many cases will out-weigh operational cost considerations when dealing with a crisis situation. News outlets and social media are starving for controversy and companies in crisis are a juicy target, so minimizing exposure is critical. Applying problem solving techniques to the crisis enables you to objectively evaluate the holistic environment and weigh the impacts of different options to make informed decisions for mitigating potential impact.

Time is of the essence

The longer an organization is in a state of crisis, the less likely they are to successfully return to normal business operations. During a crisis, the risk of making a critical mistake increases significantly – as do operational costs. While a crisis environment may be sustainable for a short period of time, fatigue, loss of focus and resource constraints can quickly diminish organizational effectiveness.

By planning ahead and ensuring that key crisis management resources understand the problem management process, are comfortable with the role they need to play and are clear on decision structures – ambiguity and confusion can be reduced once the crisis has begun. Simulation and team based problem-solving exercises can build familiarity with individual personalities, skills and working styles – reducing the potential for stress based conflict and improving problem-solving efficiency.

Effectiveness of solution

Crisis situations often lead companies to set-aside structured governance processes and bypass control mechanisms with an “in case of emergency – break the glass” mentality. While there are clearly times when exceptions to normal operating procedures are justified, it is important not to replace objective reasoning with purely emotional responses. Doing so will often lead to the selection and implementation of “solutions” that don’t actually solve the problem and have a potential to mask symptoms and other information important to the problem-solving effort.

Solutions to crisis situations need to take into account both long and short-term efficacy and impact considerations. Structured problem-solving techniques include methods for objective evaluation of alternatives to guide decision making.

Perception on how you handled the situation

Normal business problems rarely make the news (thankfully) but a leader guiding his/her company through crisis will be subject to play-by-play commentary and instant replays that would rival a professional sporting event. Every action and decision will be questioned and every nuanced statement critiqued for hidden meaning. Regardless of the outcome, it is the perception of how the crisis is handled that becomes the leader and company’s legacy.

An important (and often overlooked) aspect of structured problem-solving is communication. What the company communicates and when plays a large role in shaping customer and stakeholder perceptions on how critical the situation is, whether leaders have it under control, and can inspire confidence in their continued business relationships with the company. Crisis situations require far more sophisticated and deliberate communication plans than normal operations.

It is highly likely that your company will (at some point in its existence) find itself in a crisis situation. Planning ahead along with the application of structured problem-solving techniques could make the difference between success and failure. The problem-solving experts at Kepner-Tregoe understand this and have been helping companies just like yours navigate crisis situations for over 60 years. Don’t wait for the crisis to occur to ask for help.

KT can help your leaders and organizations develop the skills they need for crisis preparedness.

We are experts in:

For inquiries, details, or a proposal!

Subscribe to the KT Newsletter

8 Soft Skills Every Crisis Manager Needs For Maximum Effect

Aaron marks.

- November 5, 2020

- No Comments

The previous post by Erik Anez, How To Calculate Critical Risks Within Your Organization , demonstrates the role that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills and understanding play in developing crisis management skills and being an effective Crisis Manager. Those hard skills help answer the “why” questions that justify preparedness, response, and recovery decisions within the context of crises.

STEM can start to flesh out the “how” as well.

There are a growing number of training and education programs out there for individuals interested in learning more about Crisis Management. Most of those offerings will have STEM components of one type or another. Those programs also introduce softer skills such as communications and critical thinking to round out their offerings. Personally, I think that those soft skills play as much of a role in determining the success of a Crisis Manager as understanding math and systems engineering.

The soft skills that make for a great Crisis Manager

There are a core set of personality traits and soft skills that are essential for being successful in crisis management. These traits are present in all of us to one extent or another, but they can and should be enhanced through conscious effort and practice.

Let’s take a look at this soft skills and why they’re so essential for Crisis Ready® success.

Soft Skill 1: Humility

Humility is the core trait necessary for success as a Crisis Manager. It grounds an individual’s understanding of their capabilities, capacity, and the limitations of their knowledge and skills. It reminds us that we do not know or understanding everything—that there may be better answers to a question or better solutions to a situation. Answers and solutions that may even be found with or by someone far younger or less experienced.

On a personal level, holding yourself to a standard of absolute perfection is more common than it should be in our chosen field. “They only have to get it right once to win. We have to get it right 100% of the time,” is a common catchphrase in incident and crisis management. That attitude is a guaranteed path to pain and loss.

A good Crisis Manager recognizes that perfection is not obtainable and that we can, and will, make mistakes. This is especially true as Crisis Management is mostly a high-stress, high-speed discipline. It is a rare day that we get to operate in a routine task environment, responding to a different constellation of threat, response, and recovery every time. Adding irregular working schedules and the requirement to maintain day-to-day activities and managing the crisis further compounds the risk of error.

Remembering that we are limited by our education and training

Professionally, we must recognize that however specialized the Crisis Management role is within our organizations, Crisis Managers are extremely limited by our education and training. Crisis Management, as an area of academic study, is still in its early childhood, if not infancy. Training programs are frequently vocational in nature, supplementing other more formal training and education with the expectation that additional learning will continue in the field. The biggest drawback of this type of piecemeal education is a lack of understanding of the real complexities of crisis management, the vast number of interdependencies that exist in modern society, and respective strategies for managing disruptions to those systems. Significant gaps may be present in a Crisis Manager’s knowledge and understanding if they only experience a specific type or expression of those disruptions.

Humility is a beneficial trait when we assume our role as Crisis Managers within a broader organizational framework. Crisis Managers frequently operate under very irregular circumstances, sometimes as “other duties as assigned” or with ad-hoc teams based on available resources at the moment. We often find ourselves with limited support for extended periods while leadership and the rest of our organizations deal with what they believe to be more critical issues.

Other roles within our organizations have their own specialized knowledge, different resources and plans, and an entirely different set of priorities. It is essential to keep these different backgrounds and priorities in mind when interacting with other professionals. There is a critical role for Crisis Managers to play in protecting an organization and supporting both business and operational continuity. We must be careful to recognize the limits of our experiences and knowledge. With humility, we can isolate our ego from the equation and focus on the organization.

Soft Skill 2: Courage

Intellectual courage is based upon a willingness to challenge any idea, especially those which are strongly supported or rejected. No concept should be beyond questioning. Every idea or assumption should be challenged to ensure that it stands up to scrutiny. Having the courage to challenge deep-seated ideas allows us to continually grow and evolve the discipline of Crisis Management. That evolution ensures that only concepts determined to be constructive, effective, and applicable to the current environment remain in the Crisis Management mindset.

In day-to-day operations, Crisis Managers must be willing to assess whether their efforts are beneficial, unnecessary, or possibly harmful to the organization. They should also have the courage to ask a question of other Crisis Managers , to confirm the course of action to be followed or to better understand a concept or idea. This courage allows a multi-faceted approach toward crisis management.

Soft Skill 3: Empathy

Empathy is the ability to understand another’s thoughts, perspective, or situation. This is accomplished by seeing things from their perspective. Empathy is a vital component of crisis management, allowing the Crisis Manager to take in other viewpoints and understand different perspectives. This is key in seeking to understand another’s idea or trying to persuade them of the value of your own.

An effective Crisis Manager remembers that there were times in the past when they held points of view that turned out to be incorrect, but stubbornly held on to those beliefs because they were more familiar or comfortable. Sometimes changing your own mind can be more challenging than changing another’s. That process can take time while requiring a significant amount of patience and empathy.

Practically, we should extend this empathy to our internal customers, fellow Crisis Managers, and other professionals. It is essential to see each crisis as unique and worthy of an individual approach. However standardized a crisis management plan might be, situations where they are activated are often chaotic and disturbing for those directly affected by the disruption. A good Crisis Manager recognizes that and can adjust their approach within a planning framework based on their understanding of those points of view.

Crisis management professionals are often judged harshly and second-guessed for making rapid decisions. Those judgments are frequently made without an understanding of their background or the specific situation that was being faced. It is easy to judge when far removed from a problem, especially when possessing more knowledge or experience. Those judgments are especially unfair when the final outcome is known.

Empathizing with our fellow Crisis Managers (and maybe applying some humility) allows us to better assess how we might have handled the same situation at a similar time in our career. This is crucial when engaging with younger, less experienced Crisis Managers, who have not had the same opportunities to develop experience or expertise that we have had. Empathizing with peers and colleagues allows us to be more supportive, congratulating them on their successes and supporting them through their challenges.

Soft Skill 4: Autonomy

In the context of Crisis Management, autonomy entails the ability to freely ask questions, adjust perceptions, and challenge beliefs when met with new evidence or points of view. A Crisis Manager must be able to explore their thoughts and ideas to better understand them and synthesize new knowledge, understanding, and wisdom.

To do so, there must be an environment where open, non-judgmental discussions can take place. Questions should be asked respectfully and with the intent to learn, challenging without confronting or judging an individual’s actions or choices. In return, answers should be similarly academic, seeking to expand the questioner’s understanding rather than questioning the validity of the question itself.

Soft Skill 5: Integrity

Integrity in Crisis Management means that we consistently test our current views with the same standards applied to new or competing theories. It is easy to fall into the bias of personal experience and dismiss new ideas. Similarly, individuals can jump to new evidence too quickly without having adequately tested it against current thinking.

Crisis Managers who have used a skill or strategy for an extended period may defend it despite evidence that it is ineffective or the introduction of a new, better approach towards addressing a challenge. Integrity allows a Crisis Manager to assess the effectiveness of each decision made or action taken, especially in the face of questions or challenges.

Soft Skill 6: Perseverance

Crisis Management is not an individual skill acquired overnight. Like any other complex discipline, it must be applied repeatedly and under varying conditions to develop expertise. A good Crisis Manager will persevere through challenging situations and questions to arrive at viable solutions, accepting when the end course of action is different than what they initially expected.

Crisis Management is a series of skills that requires persistence and perseverance. Time and patience are needed to develop a solid foundational understanding and hone the necessary practical and cognitive skills. Perseverance is an important trait for both novice and experienced practitioners to recognize how much time it takes to become proficient and how much effort it takes to maintain that proficiency.

Soft Skill 7: Fairmindedness

Intellectual fairmindedness comes from considering every viewpoint, concept, or idea fairly. It does not mean that all positions or opinions have the same merits, but that they are worth consideration. Crisis Managers need to maintain an open mind when it comes to ideas that we experience. There are always multiple potential courses of action in response to any situation. We cannot identify the best one without fair consideration of each idea. Applying some integrity, we can test each option equally and determine its merits and shortcomings.

Soft Skill 8: Confidence in Reason

This final trait, confidence in reason, may be the most difficult to establish, grow, and maintain. Intellectually, it is the idea that similar conclusions will be reached by multiple people through the application of reason, or that we will change our own minds when faced with a better concept or more substantial evidence. With the right guidance, Crisis Managers will develop their knowledge and approaches toward situations to better their individual career and organizational care.

Practically and professionally, confidence in reason allows us an approach or worldview where things will continue to improve. Daily frustration can be mitigated by remembering that Crisis Management is a young discipline, and a lot of the challenges currently faced can be considered to be growing pains. As the role of a Crisis Manager continues to develop and solidify, those discomforts will resolve as we raise awareness of issues, create beneficial strategies and methodologies, and replace ineffective ones.

In addition to confidence in reason, we must have confidence in our peers, trusting that they are also working to improve their personal and professional skills. We should be willing to share our insights with them and open our minds to the wisdom that they might provide in turn.

Honing and fine-tuning these crisis management soft skills

As I mentioned at the start of this post, these soft skills are all learnable and are our responsibility, as Crisis Managers, to strengthen within ourselves. Doing this, requires the ability and commitment to self-reflect, self-assess (without judgement) and self-improve.

With that in mind, let me leave you with this honest reflection: How many of these soft skills do you currently possess and excel at, and which ones tend to be more challenging points that can use improvement?

The Critical Thinking Community. Valuable Intellectual Traits [Internet]. [cited 2020 October 30]. Available from: https://community.criticalthinking.org/libraryforeveryone.php .

Subscribe to the Crisis Ready® Blog

Email address:

Sector Please select from dropdown Academic (professor) Academic (student) Consultant / Advisor Professional (private sector) Professional (public sector)

Recent Posts

- How To Improve Your Crisis Communication Strategy By Understanding Near And Far Enemies April 4, 2024

- How to Apply Emotional Awareness to Powerfully Enhance Crisis Communication February 19, 2024

- Could We Train AI with Emotional Intelligence to Predict a Crisis? February 4, 2024

- How Ego Hinders Effective Crisis Response July 26, 2023

- What the Dylan Mulvaney Bud Light can controversy should teach us June 26, 2023

Blog Categories

- AI and Crisis Ready

- Case Studies

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Crisis Communication

- Crisis Ready

- Crisis Ready Culture

- Crisis Ready Flowcharts

- Crisis Ready Formulas

- Crisis Ready Hindrances

- Crisis Ready Resources

- Crisis Ready Strategies

- Critical Thought

- Current Affairs

- Exercises and Simulations

- Leadership Development

- Post-Crisis Review

- Risk Management

- Thought Leadership

Upcoming Crisis Ready Course:

Developing your crisis communication program.

Join us, September 21st and 23rd, to take your crisis communication skills to the next level.

Take the first step towards your Crisis Ready® Certification

Course: mastering the art of crisis communication and leadership, our next cohort kicks off soon, the crisis ready ® coaching program.

Aaron Marks is a Senior Principal with Dynamis, Inc. where he supports clients across the domestic National and Homeland Security communities and international public safety enterprise. He provides operational and subject matter expertise in intelligence analysis and targeting, disaster preparedness, crisis and incident management, and continuity of operations for healthcare related concerns. Aaron has provided in-depth review, assessment, and analysis for technology, policy, and operational programs impacting all levels of government. He is a recognized authority on the application of nontraditional techniques and methodologies to meet the unique requirements of training, evaluation, and analytic games and exercise for the National and Homeland Security communities.

Prior to joining Dynamis, Aaron was the Director of Operations for a commercial ambulance and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) provider in western New York State where he participated in the integration of commercial EMS and medical transportation resources into the local Trauma System. During his 30-year career Aaron has worked in almost every aspect of EMS except fleet services. This includes experience in Hazardous Materials and Tactical Medicine, provision of prehospital care in urban, suburban, rural, and frontier environments, and acting as a team leader for both ground and aeromedical Critical Care Transport Teams.

Aaron is a Master Exercise Practitioner and received a B.A. in Psychology from Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas and a master’s degree in Public Administration with a focus in Emergency Management from Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville, Alabama. He is also a Nationally Registered Paramedic and currently practices as an Assistant Chief with the Amissville Volunteer Fire and Rescue Department, Amissville Virginia.

- Filed under: Crisis Ready , Critical Thought , Leadership Development

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to the blog!

Newsletter Signup

Stay informed and at the cutting edge of your crisis readiness. Subscribe to the Crisis Ready Institute to gain from experts, be the first to receive new resources, and receive exclusive offers and materials.

Brian Kinch

Brian is an internationally recognised risk professional. He has over 35 years of experience, predominately discharging roles in domestic and international financial services businesses, including senior roles with HSBC, Visa International and Lloyds Banking Group. He has additional consulting expertise in areas such as insurance, telecommunications, the public sector and across industries in a risk, authentication, data protection, cyber, continuity and resilience context. Furthermore, he has held senior positions with the decision management and analytic giant FICO (Fair Isaac) where he was the principal risk practitioner, and both led their global fraud consulting and was a leading contributor to their enterprise risk roadmap.

Brian is an innovator and thought leader and has co-authored potential patents in the first party fraud and payment tokenisation space. He was a founder of the Mobile Identity Authentication Standard (MIDAS) Alliance, a collaboration of Information Security professionals, which was responsible for the creation of the Publicly Available Specification (PAS 499) for digital authentication by the British Standards Institution, a seminal piece of work in preparation for the implications of the European Payment Services Directive 2.

He is also a leading figure for both the Business Continuity Institute where he founded what has become two of the UK Chapters, and where he remains on the management committee, and the Institute of Strategic Risk Management where he has roles on the Global Advisory Council and as Chair of the Oversight Committee.

Brian co-founded with his brother, almost a decade ago, his own firm, Knight360 Limited, where he acts as a dedicated security advisor and risk practitioner, enjoying helping clients embrace and overcome their greatest business challenges. The company specialises in areas of business development and regulatory compliance activity and offers a raft of business consulting and partner solution services including with and through GDS Link, a client of Knight360’s which Brian has gone on to serve as Managing Director in their Global Fraud Solutions area, and where he has been independently recognised as Managing Director of the Year 2022.

Currently Brian is also retained on an equity basis as Chief Advisor to KM2 Ethical Finance Ltd, a firm where he was the founding Chief Executive Officer and was independently awarded as one of the CEOs of the Year in 2021. The KM2 business is vested in assuring the robust identification and considered remediation of misappropriated losses which sit at the nexus of bad-debt and fraud.

Throughout his career Brian has proven equally adept at working alone, leading a small team, or overseeing multi-geography operations involving well over 1,000 people.

Maxine Herr

Maxine Herr has served as Public Information Officer for Morton County in North Dakota since 2017. She started her career as a TV news reporter and anchor for the CBS affiliate in Bismarck, ND before moving to Phoenix, AZ where she worked in marketing roles for a media company and a national engineering firm. After returning to North Dakota in 2009, she did freelance writing and public relations consulting. Maxine joined the North Dakota Emergency Management Support Team in 2016 and has helped lead communication efforts for a 234-day pipeline protest, regional flooding, and the state’s COVID-19 response. Maxine’s favorite thing about her 25-year career is finding ways to communicate effectively with creativity. Maxine is married and any gray hairs can be attributed to raising her three teenagers.

Master Sgt. US Army (retired)

Rob Keller was retired from the U.S. Army when he received a call from the ND Department of Emergency Services (NDDES) to return to full time Public Information Officer status to work a “small protest happening in southern Morton County” that would probably fizzle out in 2-3 months.” Nine months later he returned to retirement status. During the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protest, Rob was the lead Public Information Officer for the Morton County Sheriff Department and the ND Department of Emergency Services Joint Information Center. Rob and his team of over 15 PIOs worked over 500 media engagements during the 234-day protest that garnished the attention of the world.

“This was the most challenging and rewarding position that I have ever been involved in my entire career. I felt that I was the “right person in the right place at the right time for the right reasons.”

Rob’s previous career positions had in effect prepared him for his last public affairs mission.

He received a Bachelor of Science degree in Television Journalism, was a TV news reporter, TV anchor, a community relations officer for a police department, a television producer, marketing and advertising for the U.S. Army, worked multiple FEMA disasters in North Dakota to include floods, wildfires, snow storms and a Canadian Pacific railroad anhydrous ammonia spill. Not to mention during his 26-year Army career, he was deployed on two public affairs missions to Iraq, five PIO missions to Ghana, Africa and working with twelve Killed In Action (KIA) soldiers and their families.

He was the Deputy PIO for the ND COVID-19 response and formed a 50-persom Joint Information Center staff within two weeks.

He has been a FEMA Crisis Communication trainer for over 10 years having trained over 600 PIO practitioners.

Far from retiring, Rob and his colleague co-founded the ND Public Information Officer (NDPIO) Association this past year (2021). The 501c3 is a nonprofit statewide organization made up of professional communicators who work in local, state, tribal, federal, or other public safety venues. This organization is dedicated to the principles of open government.

Rob has left Morton County and back to semi-retirement but is training Public Information Officers from multiple agencies who may have a need for crisis communication and for their agency to be “Crises Ready”. He is married with a very understanding wife, a son who is following in his footsteps as a career military man and a daughter who is a “stay at home” mom. He has five grandchildren that now take up his entire time. He is also an “adventure motorcycle rider” who has traveled on journeys across Canada to the Arctic Ocean, South American and everything in between.

Mike Todd is the founder and CEO of Near-Life. He has experience in media and technology. Beginning his career in digital content, he has also worked in film and television: creating internationally acclaimed feature documentaries for the likes of BBC, ESPN and PBS.

Digital Training Solutions (now trading as Near-Life) was established in 2016 around an NGO learning project (Mission Ready), funded through the United States Aid department and the UK equivalent. The project garnered international recognition and its success prompted an invitation for Mike to speak at the UN World Humanitarian Summit, as well as to the UN in New York.

A related project, developed with the Norwegian Refugee Council, was recognised for 'Excellence in Learning Design' at the Learning and Technology Awards - Europe's top EdTech awards. He has extensive experience in dealing with the resilience and responder communities. He most recently led the delivery of a major immersive learning / Tech project with the World Health Organization’s Emergency Medical Teams programme.

About the Inaugural Membership Feedback

As we get this membership off the ground, we’re looking to our 2022 inaugural members to be a part of helping us strengthen and tailor this program to meet your needs.

This will involve regular communication with the Crisis Ready Team to provide feedback, share requests for additional ways to support you and your business, etc.

About the Crisis Ready Courses

Each Crisis Ready Course is designed to help you strengthen your Crisis Ready® Expertise. Course subjects will include crisis communication, establishing governance, crisis leadership, storytelling for crisis comms, DEI integration, and more.

Each course is complete with:

- Anywhere from 4-15 hours of virtual learning that you can do at your own pace

- Knowledge tests

- Worksheets and resources to help you bring these valuable learnings and use them within your client work (applicable solely to those who have the license through this membership)

- A Certificate Of Completion upon successful completion of each course

Crisis Ready: Building an Invincible Brand in an Uncertain World (Bulk Purchase)

Opportunity for individualized coaching and support.

- Sometimes feel as though you’re in over your head with your clients’ issue and crisis management needs

- Could use support and coaching to help you prepare for and have business development discussions with prospective clients

- Wish you had more behind-the-scenes support as you serve and support your clients

- Would benefit from personalized coaching and support as you take your Crisis Ready skills and services to the next level...

... then you will benefit from Crisis Ready Institute's 1:1 coaching and support. This opportunity is retainer-based and is offered exclusively to our consultant and small agency members.

This offering provides personalized coaching and support in:

- Managing client issues and crises as they arise. We support you as you support your clients so that you can feel confident in the recommendations and advice you provide.

- Integrating the Crisis Ready Model into your business and client work.

- Helping you strategize business development conversations and close more deals.

- Gaining buy-in from existing clients. We can be your frontward-facing partner or remain behind-the-scenes, whatever the situation calls for.

Two Packages Available:

Monthly retainer* Hours of support per month

$2,500 USD Up to 5

$5,000 USD Up to 10

* This is in addition to the annual membership fee.

Danny Langloss

Danny Langloss is a dynamic leadership motivational speaker specializing in creating leadership cultures, employee engagement, ownership, belonging, change leadership, and crisis leadership.

Danny’s leadership has been tested by the most difficult situations. Global pandemics, leading the City of Dixon back from the $54 million Rita Crundwell theft, homicide investigations, hostage situations, school shooter incidents, major legislative reform, and creating high performing cultures across very difficult professions are just some of the leadership challenges Danny and his teams have overcome in their pursuit of excellence. Danny has applied these skills to create great teams across many different leadership roles, including city manager, police chief, state task force chairman, legislative initiatives, not-for-profits, and private organizations.

Paul Damaren

Paul Damaren has worked as a Senior Executive in the Certification space for 17 years and has over 35 years’ experience in the hospitality, service and retail agri-food sectors. Damaren is skilled in sales, marketing, certification, operations and software applications. He possesses an MBA from McGill University.

Mr. Damaren is experienced managing full P&L and $100M in global sales. Across his career he has built a reputation as a professional undeterred by obstacles and committed to success. He is skilled in cultivating top performing teams that always exceed organizational objectives and is able to lead organizations out of challenges through improvement initiatives and change management. He is an expert in relationship building strategies to ensure metrics are always met or surpassed and is a technologically savvy professional that thrives with constantly evolving environments and guides growth with clear visions.

Damaren has worked with countless clients for their food safety, supply chain, health & wellness, brand protection, quality, environmental, health & safety, GMP, automotive, aerospace, medical and information technology requirements.

Damaren is a board member of the OFPA, Ontario Food Protection Association and has assumed the position of Treasurer for 2022. He is a current Advisory Council Member with The George Washington University, School of Business for their Digital Marketing Certificate Program. Mr. Damaren is also a Partner and CCO of StepUp Learning Company Inc., a consulting and advisory business. Further, Damaren also maintains an Executive Partner position with ReposiTrak, a global software company that provides an integrated platform for optimizing sales, sourcing & safety in the food supply chain.

Before working in the Certification industry, Damaren was a professional Chef/consultant for 20+ years working in major hotel chains, restaurants, private golf courses and food service organizations such as Aramark. Further, Damaren was a member of the National Canadian Federation of Chefs and Cooks (C.F.C.C.) for 14 years, member of the Region of Waterloo Culinary Association (R.W.C.A.) for 14 years, President of R.W.C.A. (Region of Waterloo Culinary Association) for 3 years, special Events chairman - R.W.C.A. – 1998 – 2000 and National Culinary Ambassador to Russia for 5 years.

Tarisa Shelton

Tarisa Shelton was born and raised in Arizona. She graduated with a Bachelors's in design studies and management from Arizona State University in 2015. After graduation, she traveled to multiple countries to try and learn from different cultures and perspectives. With being excited by what the world had to offer, she taught English in South Korea to elementary students for a little over a year.

After traveling and teaching in Korea, she worked as a production manager at an animation studio in DC. During that time, she committed herself to learning as much about finances as humanly possible. Through that journey, she found infinite banking, in 2018. Since then, she's been helping clients, family, friends implement this process to fundamentally set a financial foundation that is unshakable and sets them up for success not only today but for generations to come.

Emmie Saavedra

Emmie Saavedra is the President and Co-Founder of The Champions Institute, where she leads teams of expert coaches, trainers and consultants on Sales, Communication and Extreme Leadership. With more than 30 years in the medical and dental industries, and over a decade in entrepreneurship, her strengths lie in building deep relationships, elevating personal and team performance, and empowering strong leadership. She is an award-winning Certified Trainer and Coach with Codebreaker Technologies and masterfully trains the B.A.N.K. Methodology to teams and entrepreneurs to produce astronomical results, top revenues, and trusting relationships. Emmie is committed to empowering others to achieve phenomenal success both in life and in business because she believes that both are tightly integrated and hold the KEY to living a fulfilling and joyful life.

Cathy Compton, HALL OF FAME CHAMPIONSHIP COACH

Cathy Compton truly is a coach of Champions. For over 20 years, Cathy has been coaching championship teams and building empowering leaders. With an extensive background in coaching world class athletes, Cathy has worked with, coached, and consulted top level CEO’s, corporate executives, Olympic Athletes, business owners, Major League Baseball players, and other elite professionals who are committed to peak performance. Cathy ranks as one of the most successful college coaches in NCAA Softball history and is a member of two college Halls of Fame. Her expertise is building winning teams, developing empowered leaders, and training top performers how to better communicate and collaborate for optimal results.

Career Highlights Include:

- Overall Coaching record 410-130 ranking her as one of the top winningest coaches in NCAA history

- 15 winning seasons over 15 years as a Head College Coach

- Built the LSU softball program achieving a top 10 national ranking in her first two years leading the program

- Coached professional Women’s Softball (Durham Dragons) Durham S.C.

- Has coached All-Americans, Olympic athletes, and professional athletes across multiple sports

- Member of 2 College Softball Halls of Fame

- Built and managed Corporate wellness programs for America Online, Motorola, 3 Com, EMC, Netscape and Netpark

- Co-founder of Youphoria, A Wellness based, weight loss company

- Performance Coach for CEO’s, Olympic athletes, business owners, and Major League Baseball players

- Author of “Empowered Women” an Amazon Best-Seller

Certification/Awards:

- Body Code & Emotion Code Certified Trainer

- Extreme Leadership Coach/Trainer (Steve Farber)

- Bankcode Technologies Coach and Certified Trainer

- BANK Blueprint ICON award - Codebreaker Technologies

Pragya Dubey

Pragya Dubey is Vice President, Global Services & Media Analytics at Agility PR Solutions. Pragya has over 20 years of industry experience in consulting and executing public relations, communications, and media measurement programs. She has worked with a range of clients representing Fortune 500 companies, federal, provincial, and municipal government divisions, and small to medium sized businesses. The key focus of her work has been in tracking companies’ communication activities to measure, and correlate and connect how these activities are impacting business objectives. Pragya’s approach includes educating, consulting, problem solving for clients, and creating solutions that are objective-based programs with defined success metrics.

Pragya has taught at the Ottawa-based Algonquin College’s public relations program and given guest lecture at Carleton University. She was the speaker at the Public Relations Society of America's (PRSA) 2020 annual conference on the topic of measurement. She actively conducts measurement-related webinars for Agility PR Solutions and other PR forums.

Liam Kelly has worked in the field of church communications in the Catholic Church for more than forty years, including time in the Vatican and in London at the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales. Since 2002 he has been working in the Abbot’s office at Ampleforth Abbey.

Before you go to checkout...

Click below...

- Add to cart

Crisis Ready Governance Audit (Have experts review and provide feedback on your Crisis Ready Governance Structure)

1:1 Consultation (45-minute one-on-one consultation time with a member of the Crisis Ready Team, after the live event)

Have experts review your crisis comms program prior to the course

1:1 Consultation time with a member of the Crisis Ready Team, post the course (per hour)

Shawna Bruce

Shawna Bruce is a seasoned strategic communicator and trainer with 30 years of crisis communications, public information and public affairs experience and a passion for public safety.

After serving in the Canadian Forces as a Public Affairs Officer (27 years) and working in the petrochemical industry at Dow Canada as their national Public Affairs Manager (8 years), Shawna began putting her focus into crisis communication, community preparedness, public information and emergency management training when she began her own consulting business: M.D. Bruce and Associates Ltd in 2019.

Shawna considers herself "a life-long learner" and is a leader who specializes in developing teams and sharing her knowledge and experience on the critical role of public information in emergency management with an emphasis on how communications support operational objectives.

A self-identified "Master of Disaster" (RRU MA DEM) Shawna's goal is to support emergency managers and DEMs identify opportunities to communicate throughout all phases of an emergency management program, and works to prepare communications teams to respond in an emergency setting.

Currently, Shawna is also a part-time instructor for NAIT’s Disaster and Emergency Management program (Disaster and Crisis Communications), supports co-instructing the Public Information Officer course as part of NAIT's Centre of Applied Disaster and Emergency Management IMT Academy, develops curriculum for delivery in post-secondary school and Continuing Education programs and is the Public Member on the Board of Directors at NR CAER - a mutual aid emergency response organization in Alberta's Industrial Heartland.

An engaging speaker and trainer, Shawna delivers workshops for risk and crisis communications, emergency public information, how to use public notification systems effectively, on-camera media awareness training, and spokesperson training for industry, municipalities, organizations, first responders and anyone who is looking to build the skill sets of their teams to respond to fill the need of crisis communications and public information.

🍎 School district communicator @ Stoughton Area School District.

🏙 Belmont University grad.

Melanie Litten

Media • Social Media • Public Relations • Nonprofit Director

Mark Hobden

Currently employed as the Director of Operations Support with Bidvest Noonan.

Having worked on several high profile contracts at Management level, I am a results driven and self-motivated professional. A wealth of practical security experience within the security industry and HM Forces. Well developed presentation and communication skills at all levels. Proven planning, organisational and administrative abilities.

Lorelei Russell

Employee Services provides Compensation, Benefits and Wellness services to over 8000 employees represented by 14 Collective Agreements and professional associations.

Jan Walther

I bring the most value when I'm given a "blank sheet" opportunity to develop solutions for complex, multifaceted, consumer-focused challenges. I am most passionate about identifying or creating opportunities to increase engagement, visibility, and revenue.

Understanding and advocating for memorable consumer experiences is at the heart of what I bring to any opportunity. While providing leadership and strategic vision is what I do best, focusing on what is relevant and important to target consumers is essential.

I am passionate about building brands that drive consumer insistence and loyalty. My experience in developing brands ranges from the core of strategy building and story creation to tactical activation and data assessment to measure success.

Whether leading enterprise integrated marketing strategies, creating content, or developing relationships as a business partner, I am a visionary and results-oriented collaborator with extensive experience in metrics-driven, brand-focused marketing and communications.

As an outstanding innovator, communicator, and relationship builder, my expertise in translating business objectives into strategies have proven to grow revenue and engagement especially in large organizations in which local market integration is essential.

My leadership style is based on a true coaching philosophy that encourages growth and trust for all team members. I am a highly-effective, hands-on team leader who enthusiastically influences and motivates teams to meet complex business challenges.

Angelica Montagano

I specialize in communications (corporate, internal and external), digital and content marketing, brand awareness and reputation and public relations. I’ve advised individuals and businesses (small and large) on what steps they need to take to reach their target audience.

If you need help with content marketing strategy (blog writing, podcasting, YouTube), strategic communications strategies (internal communications, crisis communications, corporate communications), public relations, lead generation or even team building and relationship management – then please feel free to reach out to me.

Amy McKenzie

Passionate communications professional with a diverse experience in public relations, social media, and leadership.

Patrick Campion

Founder of Preparedness Advisors LLC. I am an experienced emergency management and homeland security professional focused on providing innovative strategy and data analysis solutions, streamlined project management support, and straightforward consultation. Please visit the Preparedness Advisors website: www.preparednessadvisors.com for more information.

Elle Arlook

Elle Arlook serves as APCO’s Deputy Advisor on Equity & Justice and a senior associate director in the Corporate Communications practice. Elle has a depth of experience counseling clients through transformation rooted in efforts to advance equity, diversity, and inclusion. She has counseled clients through challenges that range from responding to external societal crises to racial discrimination lawsuits and boycotts. Her background includes experiences that sit at the intersection of DE&I and traditional corporate communications, stakeholder relationship development, non-profit strategic counsel, media relations and crisis management. Her clients have included one of the world's largest global health companies and household names such as Walgreens, Walmart, National Urban League, CarMax, and the University of North Carolina System's Racial Equity Taskforce.

David Meerman Scott

I was fired. Sacked. My ideas were a little too radical for my new bosses. So I started writing books, speaking at events and advising emerging companies. That was in 2002 and since then my books have sold over a million copies in 29 languages.

Many new forms of social media have burst onto the scene over the years, including blogs, podcasts, video, virtual communities, Twitter, Facebook, Foursquare, Instagram, and many many others. But what’s the same about all the new Web tools and techniques is that together they are the best way to communicate directly with your marketplace.

My latest Wall Street Journal bestselling book "Fanocracy: Turning Fans into Customers and Customers into Fans" released from Portfolio / Penguin Random House. I wrote Fanocracy with my 26 year old daughter Reiko. The book is about Fandom culture and how any business can grow by cultivating fans.

My 2007 book "The New Rules of Marketing & PR" opened people's eyes to the new realities of marketing and public relations on the Web. Six months on the BusinessWeek bestseller list and now in a 7th edition with 400,000 copies sold in more than 29 languages from Albanian to Vietnamese, "New Rules" is now a modern business classic.

My other international bestsellers include "Real-Time Marketing & PR" and "Marketing Lessons from the Grateful Dead" (written with HubSpot CEO Brian Halligan) and my most recent books are "The New Rules of Sales & Service", and "Marketing the Moon" (written with Richard Jurek and with a foreword from Gene Cernan, the last man on the moon and now being made into a film).

I'm Go-to-Market LP at Stage 2 Capital where I invest in and advise some of the most promising new businesses in the world. I'm a co-founder and Partner in Signature Tones, a sonic branding studio.

I serve as an advisor and investor in emerging companies that are transforming their industries by delivering disruptive products and services.

Pre-pandemic, I delivered keynote speeches at in-person conferences and company meetings all over the world. Now I focus on virtual events.

Katie Nelson

I am the Social Media + Public Relations Coordinator for the Mountain View Police Department in northern California. I specialize in social media management, speaking across the country on social media best practices, crisis communications and forming positive working relationships between law enforcement and the media.

Before joining MVPD, I worked as a public safety reporter for papers including the San Jose Mercury News, the East Bay Times and the San Francisco Chronicle. Published nationally, I was an award-winning journalist for my breaking news coverage of the Asiana Airlines crash at San Francisco International Airport and my investigative work on the state Department of Social Services led to major legislative reform to protect elderly residents in California.

Lisa Manyoky

With over 30 years of communication, branding, marketing and entrepreneurial expertise in my hip pocket, I understand people, interpersonal dynamics, motivation, expression, business—and words, especially words!

I can't resist the chance to help professionals figure out if what they're putting out there—whether you can see it, hear it, read it or feel it—is getting them where they want to go OR if where they are is where they should be. I look for that delicious sweet spot of what they WANT to do, ARE BUILT to do and ARE MEANT to do. Then, I determine if their “message” is working for them, fix it if it needs fixing, adjust the volume so their world can hear them, and make a plan that helps them keep on keepin’ on as they stretch toward their goals.

As a career entrepreneur, founder of Presence Intelligence™, and licensed, specialty-certified coach with a neuroscience focus (wow!), I blend an understanding of brainpower, behavior, aesthetics and communication with business smarts to help professionals...

- identify what makes them tick

- find their "fit"—personally and professionally

- strengthen and make good use of their natural assets

- develop their one-of-a-kind presence that’s true to who they really are

- refine communications to reflect who they are and draw in resources and people right for them

- improve perception and reception

- become excellent (or more excellent than they already are)

- shape lives in important ways

- get remembered for something great by those who matter to them.

I am a bit of a firecracker who champions self-mastery, integrity, personal best and kindness. I am the consummate wordsmith with an energetic style, a quick wit and an expansive mindset. I am direct but diplomatic, dynamic and funny. I also have a very big heart.

Lewis Werner

My mission is to cultivate proactively safer communities.

Proactive risk management makes people less stressed, more comfortable, happier, and more productive. Cultivating proactive security operations desrisks and accelerates human progress, raising quality of life for everyone.

I cultivate proactively safer communities by arming Security Professionals with the data they've been missing for decades. Operations, Finance, Marketing & Supply Chain have been building metrics and KPIs based on real-time process control, outcomes, and projections. Security, especially physical security, has been left with: "Monthly Incidents and Annual Budget".

If you HAVE data, you can measure it. If you MEASURE data, you can IMPROVE it. I started Quill Security to provide risk data for security professionals.

Quill Security is building the inevitable future of the security industry. When you embrace risk data, you will:

- Earn your seat at the table with answers instead of assurances.

- Communicate clearly with non-security stakeholders to achieve buy-in.

- Spend less time debating and more time taking PROACTIVE ACTION.

- Know your measure of success and unambiguously achieve it.

Nothing like Quill has ever existed before. Protect your community with the future of security.

Alliancé Babunga

Alliancé [pronounced “aliya-n-say”] comes with a background in politics, leadership and education which speaks to her passion for people and positive change. Through her experiences she has learned first-hand the importance of having a unique voice, the value of authentic communication, being relatable with one's audiences, establishing relationships and working collaboratively to get things done.

She has worked in multiple political campaigns; a highlight being the successful election of two city councilors, one Member of Parliament and one Prime Minister.

As a crisis communications enthusiast, she came to the realization that the traditional crisis preparedness plan does not meet the demands and needs of today—the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath demonstrated the extent of this truth. She sought for a more proactive approach that would empower leaders and organizations to readily take on the new evolving challenges. It is her curiosity that grounded her interest in pursuit of crisis communication and led her to the Crisis Ready® Institute.

In 2020 and 2021, Alliancé grew her career with the Crisis Ready® Institute as the Marketing and Community Manager. Her portfolio included building and strengthening the Institute’s brand reach, visibility and engagement, and fostering the growth of the Crisis Ready® Community .

Alliancé holds a Bachelor of Arts in International Relations from the University of British Columbia, studied Peace and Conflict Resolution Studies at Uppsala University in Sweden, and recently completed the Public Relations Certificate program at Simon Fraser University.

Alliancé serves as Events Manager in the British Columbia chapter of the International Association of Business Communicators (IABC), Regional VP Administration in the British Columbia chapter of the Canadian Black Chamber of Commerce (CBCC) as well as Public Policy Coordinator on a Partisan National Women’s Commission.

Lisa DuBrock

Lisa has 20+ years both in Management of fortune 100 firms and in the Management Consulting Business. She specializes in security both physical and logical. Lisa utilizes a myriad of methodologies based on her clients needs, including: ISO 27001, ISO 20000, ISO 9001, ISO 22301, ANSI/ASIS-SPC.1, ANSI/ASIS-PSC.1 and ISO 18788.

She has a CPA, a CBCP (Certified Business Continuity Professional), and an MBCI.

Lisa teaches at George Mason University in their PTAC and she sits on the ASIS Standards and Guidelines Commission developing ANSI accredited standards.

Prior to becoming a Managing Partner at Radian Compliance, LLC, Lisa spent a number of years at Discover Card, where she held positions such as National Director Cardmember Service, National Director Business Continuity, Bank Operations and Regulatory Compliance and she assisted on the launch of their credit card in the UK market.

Her goals are to grow her own firm, Radian Compliance, LLC, over the next 5 years.

Sign up to demo this course!

We're excited to be sharing Sustained Resilience: Building Tomorrow's Leaders with you. Fill in the form below to gain access to demo this course. Once you fill in this form, we'll send you an email with further instructions.

Thank you for the honor of considering this important course for your curriculum. We look forward to sharing in the experience with you!

- Winter 2021

- Summer 2021

- By checking this box, (a) I represent I am a faculty member at my academic or educational institution, and (b) I agree that I am subject to and shall comply with the Terms of Service and any other rules, requirements, and/or other policies regarding this program.

Melissa Agnes

Founder and ceo, crisis ready institute.

- Recognized globally as an expert, thought-leader and visionary in the field of crisis management.

- Has worked with global players, including NATO, the Pentagon (DoD), Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense, financial firms, technology companies, healthcare organizations, cities and municipalities, law enforcement agencies, aviation organizations, global non-profits, etc.

- Author of Crisis Ready: Building an Invincible Brand in an Uncertain World—ranked amongst the leading crisis management books of all time and named as one of the top ten business books of 2018 by Forbes.

- Creator of the Crisis Ready ® Model–which is recognized and being taught as leading industry best practice in universities and higher education curriculums around the world, including at Harvard University.

- Sits on the panel tasked with developing the International Standard for Crisis Management— ISO 22361, Guidelines for developing a strategic capability.

- Visiting scholar at D’Youville University, where she co-created and co-teaches a Crisis Ready Program for young college students.

- Sits on Police Professional Standards, Ethics and Image Committee for the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

- Global Advisor for The Institute for Strategic Risk Management (ISRM), a global player established to help progress and promote the underlying understanding and capabilities associated with strategic risk and crisis management on a global scale.

- Leading international keynote speaker on the subject and TEDx alumna.

- Founder of the Crisis Ready ® Community.

Build for a stronger tomorrow by strengthening your team’s skills in issue management, crisis management, and crisis communication.

Between the demands of our social impact economy, the divisiveness of society and the many other challenges in front of us, embedding a crisis ready culture is more important than ever before. Having a team that is trained, poised, and empowered to effectively respond to risk, controversy and other threats, will strengthen stakeholder relationships and increase the brand equity of your organization. This is a powerful opportunity. The Crisis Ready® Coaching Program is specifically designed to equip your team with the tools needed today for launching into a stronger tomorrow.

Effectively manage through today’s challenges with the help of a diverse group of experts.

From best practices around re-opening, to diversity and inclusion, to managing through the impacts that 2020 has left on your business, the Crisis Ready® Coaching Program is designed to support you through the challenges of today, in order to recover faster and stronger for an even better tomorrow.

Gain strategic foresight into the coming months, giving you the tools you need to better anticipate and plan for a stronger future.

COVID-19 continues to affect a great majority of professionals and businesses, leaving them blindsided by its impact and all the uncertainty that came with it. The Crisis Ready® Coaching Program provides you with access to a diverse group of experts, each with unique areas of insight, to help provide you and your team with strengthened foresight to better anticipate and plan for both the risks and opportunities that lay ahead of us all.

Shireen Fabing

With almost twenty years of marketing experience, thirteen of which was spent in the telecom industry, Shireen brings with her an experience toolkit which includes marketing, public relations, communications, training & development, fundraising and project management.

She started her career in a PR agency and her portfolio included retail promotions and events as well as various high-profile projects for the City of Cape Town. This position came only a few short years after apartheid was lifted in South Africa and it is what she claims toughened her up for the real world. She built tenacity, resilience and grit in those early years and more importantly, learnt the importance of building contingencies around all events and programs.

When she made the move to Canada in 2002 to join her mom and siblings, she was mentally ready for the challenge of starting a new life. Circumstances found her back at school studying part time, working full time in the PR division of an ad agency, and volunteering for a not-for-profit benefitting at-risk youth. It was in this latter portion of her journey that she found a passion for Sponsorship Marketing & Special Events.

Accepting an entry level marketing position at a large Canadian telco to get her foot in the door, Shireen quickly gained not only the North American experience she was lacking, but also credibility with internal and external stakeholders, with her strongest suite being that she was always prepared for whatever would prove to come. She enjoyed getting to see some of Canada while showcasing some of the biggest concerts, festivals, theme park & sports activations, along with a multitude of innovative product launches.

The personal pride of her career was finding non-traditional sales venues where she successfully “married” marketing tactics and sales with a profitable outcome for the organization.

Shireen’s bio is not complete without talking about her boxing life. Initially she started the sport to help her create a work-life balance, however in 2013, when she was asked to compete in her first sanctioned charity bout, she humbly obliged.

The Fight to End Cancer was founded in 2011 and has donated over $1.5M to date in support of cancer research with proceeds going directly to support the Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. This didn’t come as a shock to her family, friends or colleagues as they knew she’d be all in for training and fundraising! Training like a fighter was no different from the day-to-day boardroom she was used to - only with gloves, her self-motivation and a will to win! She was the first female corporate fighter to enter the ring for this annual event and with her opponent, they set the stage for future female bouts in coming years as they claimed bragging rights for “fight of the night”.

Today she continues to support the initiative, pursuing the sport as an amateur boxer and boxing coach allowing her to share her passion for the sport that found her.

Shireen spreads the word that she is living proof that you can do whatever you set your mind to, no matter what stage you’re at in life. Her personal mantra - strong is my beautiful - has turned into the driving force that is behind the self- proclaimed “Machine”.

Detective Frank Rivas

High Tech Professional with diverse,domestic and international background: Business Development, Operations Management, Program/Project Management, Partner Management, Process Improvement. Additional experience includes: asset and brand protection, threat/risk analysis.

Always interested in new challenges, dynamic work environment which provides intellectual stimulation and professional growth.

Specialties: Partner management, supply chain management, Operations Management, Latin American region, Public Safety, Risk/Threat Analysis, Leader / Talent Development

Peter Willis

My gift is to help individuals and groups of people think wider and deeper together than they might otherwise, especially about matters of critical importance. My current work is to help decision-makers reflect on, and learn from, their response to crisis.

Dr. Rafik Chaabouni

Specialities: Cryptography, Security, public key cryptography, range proof, set membership, certificate revocation.

Tom Compaijendion

Working on a future-proof crisis organization

✓ CRISIS MANAGEMENT IS CUSTOMIZATION A lot comes to your organization during a crisis. It is not always easy for employees to switch quickly from daily activities to the ‘crisis position’, with clearly defined roles, tasks, sharp processes and short consultations. Many employees are too little concerned with crisis on a daily basis to be really good at it. In short: crisis management is always tailor-made – and that is not always easy in a crisis situation, in which crisis consultations are often unstructured and go in all directions. I ensure that crisis organizations are better prepared for a crisis through advice, training, training and practice, so that they take the right actions more quickly, maintain confidence in the organization and thus prevent the crisis from becoming a ‘reputation crisis’.

✓ ANALYSIS AND YOUR ENVIRONMENT IN IMAGES A crisis places high demands on communication: the public and stakeholders expect a quick response (within an hour); the reaction must be visible among the thousands of messages on social media and one must take into account that the emotion wins over the ratio. I help organizations to set priorities and, in the midst of the complex playing field, to maintain good coordination with all stakeholders and to take on the role for which the organization is responsible.

✓ IMPACT ON YOUR ORGANIZATION In times of terrorism, (a growing number of) cyber attacks, coronavirus and other crises, knowledge of crisis management and crisis communication is crucial. After all, a crisis poses a risk of (image) damage. Most companies are therefore working on it, but despite the training, it turns out that it does not work well during an exercise. I guide and advise organizations in the transition to a more organized and partly automated information management system.

✓ROADMAP TO PERFECTION Compaijen Crisis Management and Communication has knowledge and experience at all levels: both national (Ministries), local (municipality of Amsterdam, security region) but also international (United Nations, EU consultation). As a trainer, I am one of the few with exceptional crisis experience. This allows me and we are able to convey a clear story with interesting cases and keep things simple. We always aim to make the organization truly better – and not just to complete training.

*Translated from Dutch

Andrea Bonime-Blanc

Andrea Bonime-Blanc, JD/PhD, is CEO and Founder of GEC Risk Advisory and a global governance, risk, ESG, ethics, cyber and crisis strategist, serving a broad cross-section of business, nonprofits, and government agencies. Since 2017, she has served as the Independent Ethics Advisor to the Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico.

Dr. Bonime-Blanc spent two decades as a c-suite global corporate executive at Bertelsmann, Verint, and PSEG overseeing legal, governance, risk, ethics, corporate responsibility, crisis management, compliance, audit, InfoSec and environmental health and safety, among other functions. She began her career as an international corporate lawyer at Cleary Gottlieb, was born and raised in Europe and is multi-lingual.

She serves on several Boards and Advisory Boards including Greenward Partners (a Spanish green energy firm), Ethical Intelligence (an EU-based AI ethics firm), ProtectedBy.AI (A US based AI cybersecurity firm), Epic Theatre Ensemble (a NYC nonprofit), the NACD New Jersey Chapter and NYU Stern-based think tank, Ethical Systems. She also serves as a Governance Mentor at Plug & Play Tech Centre, a global start-up eco-system. She is a NACD Board Leadership Fellow and Governance faculty and holds the Carnegie Mellon CERT Certification in Cyber-Risk Oversight.

Andrea is a global speaker, including at Davos, and appears regularly on Bloomberg TV, Yahoo Finance, Cheddar and other media. She is faculty at NYU’s Center for Global Affairs Masters program teaching “Cyber Leadership, Risk Oversight and Resilience”. She is an extensively published author of many articles and several books including The Reputation Risk Handbook, Emerging Practices in Cyber-Risk Governance and The Artificial Intelligence Imperative. Her latest book, Gloom to Boom: How Leaders Transform Risk into Resilience and Value (Routledge 2020) debuted as an Amazon #1 Hot Release in Business Ethics and Game Theory. She lives in New York City with her family and is an avid photographer and artist.

Marylène Ayotte

Marylene is a Life Transformation Consultant, Trainer and Coach licensed with The Brave Thinking and HeartMath Institutes, premier training centers for transformational coaching in California. She also holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Business and Human Resources Administration and a Master’s Degree in Organizational Communications and Change Management.

Through her professional career and track record of over 20 years as a Coach, HR Executive Leader and Change Management expert in medium and large corporations, Marylène now shares her know-how & proficiencies through inspiring workshops and in-depth, proven and reliable transformational coaching tools and programs.

Marylene’s passion is to inspire in others self-reflection and greater awareness leading to growth mindsets and behavioural changes. As a result, individuals reach and sustain new heights in performance, success and vitality.

Licy Do Canto

Licy Do Canto, is a veteran of public policy, corporate strategy, health care communications and diversity and inclusion, is managing director of APCO Worldwide’s Washington D.C. office headquarters and mid-Atlantic region lead. Licy is also a Global Advisory Council (GAC) member here at the Crisis Ready Institute and a highly recognized African-American public affairs, lobbyist and communications strategist— recognized by TheHill newspaper for the 11th consecutive year as one of the most influential leaders in Washington, DC.

As Executive Vice President and Managing Director in the BCW Public Affairs and Crisis practice, Licy drives healthcare and social impact policy and strategy, and helps shape strategic direction on diversity, inclusion and belonging for the firm and its clients across North America, in public and corporate affairs, government relations, communications, crisis and reputation management. Licy also leads the BCW Healthcare Team in Washington, D.C.

An expert in public affairs, policy and diversity and inclusion, with over twenty five years of experience at the international, national, state and local levels across the nonprofit, philanthropic, corporate and government sectors, Licy is an accomplished, values-driven leader with unparalleled experience in developing and leading integrated public affairs campaigns combining strategic communications, public relations, political/legislative initiatives, policy, coalition building, grassroots efforts and advocacy.

Before joining BCW, Licy built and lead a nationally recognized minority owned strategic public affairs and communications firm, served as Health Practice Chair and Principal at The Raben Group, was the Chief Executive Officer of The AIDS Alliance for Children, Youth and Families, and managed and helped set the leadership direction for strategic policy, communications, and advocacy investments in executive and senior government affairs roles for the American Cancer Society and the nation’s Community Health Centers.

Before joining the private sector, Licy was domestic policy advisor to U.S. Congressman Barney Frank and served in several capacities in the Office of Senator Edward M. Kennedy. During his extensive tenure in Washington, D.C., Licy has played a leading role in efforts to draft, shape and enact legislation and policy to improve the public health, health care safety net and the lives, livelihoods and well-being of the nation’s disadvantaged and underserved communities.

Licy also has worked with Moet Hennessey to drive diversity and inclusion on Wall Street and corporate America. He has partnered with Vice President Al Gore, senior government officials, scientists, NGOs and activists, on global climate change impact and sustainability across Africa. And he was appointed by Republican and Democrat governors to oversee the conservation, preservation and management of a prominent U.S. national historic landmark.

Licy is a graduate of Duke University and holds a certificate in public health leadership in epidemic preparedness and management from the University of North Chapel Hill—School of Public Health and Kenan Flagler Business School, and is the recipient of multiple industry awards and citations for his leadership, policy and public affairs acumen, including being named to The Hill Newspaper list of most influential leaders in Washington, D.C. consecutively over the last ten years. As a global citizen, Licy has lived in Turkey and Spain, and is fluent in Spanish and Cape Verdean Portuguese.

Recognized globally as an expert, thought leader and visionary in the field of crisis management, Melissa Agnes has worked with global players, including NATO, the Pentagon (DoD), Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense, financial firms, technology companies, healthcare organizations, cities and municipalities, law enforcement agencies, aviation organizations, global non-profits, and many others.

In 2020, Melissa founded Crisis Ready Institute, a public benefit corporate dedicated to creating a crisis ready, crisis-resilient world by elevating industry standards; providing training and certification programs to professionals that better protect people, brands, the environment, and the economy in times of crisis; and promoting and incentivizing organizations and leaders to invest in effective crisis readiness.

Her book, Crisis Ready: Building an Invincible Brand in an Uncertain World , is taught in dozens of universities around the world, including at Harvard University; is ranked amongst the leading crisis management books of all time, by Book Authority ; and was named one of the top ten business books of 2018 by Forbes .

Melissa is the creator of the Crisis Ready® Model, which is recognized and being taught as leading industry best practice in the fields of crisis management and crisis communication.

As an in-demand international keynote speaker and a TEDx alumna , Melissa has traveled the world helping organizations and leaders further strengthen their crisis ready mindset, skills and capabilities.

In 2019, Melissa founded the Crisis Ready® Community , a space for professionals to come together to support one another, collaborate and strengthen their crisis ready skills.

Melissa sits on the Board of Trustees for D'Youville University, a private University in New York, where she also serves as a visiting scholar for the course she co-created and co-teaches on Crisis Leadership.

Melissa also sits on the Board of Directors for ZeroNow, a non-profit organization committed to ending harmful events in schools.

Passionate about serving law enforcement and bridging the trust divide between agencies and the communities they serve, Melissa is a member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP). In 2021 she co-chaired a committee that was tasked with developing a strategy and plan of action to begin managing and overcoming the trust crisis in the U.S.

In 2019 and 2020, Melissa sat on the panel tasked with developing the International Standard for Crisis Management— ISO 22361, Guidelines for developing a strategic capability.

Born and raised in Montreal, Quebec (Canada), Melissa currently lives in New York City and enjoys traveling, rollerblading, sailing, and working out when she isn’t working.

Erick Anez is the Global Head of Business Resilience at Finastra. Erick is a proven leader with well over a decade of experience leading change and transformation in the Operational Resilience field.

His hands-on approach focuses on operational learning, culture, and reputational management. Erick holds a Bachelor of Emergency & Homeland Security, Graduate studies in Security and Disaster Management, is a Certified Business Continuity Professional (CBCP), Certified Risk Management Professional (CRMP), graduate of the FEMA institute in Incident Management and Command, and is a respected member of Public-Private partnerships within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Some of his most notable achievements in the field include leading the private sector response to Hurricane Maria as well as working with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in Continuity of Operations (CCOP) projects for mission-critical facilities in the United States. Erick has also trained with the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in Infectious Disease Planning and community response, including Point of Dispensing initiatives.

From 2016 to 2019, Erick held several roles at Crowley and, most recently, was the company’s Managing Director of Safety & Resilience. During this time, he was responsible for resilience operations supporting all business segments as well as leading the organization’s safety culture improvement journey. At Crowley, he led the Occupational Health & Safety, Business Continuity, and Crisis Management teams.