Take Action Against Addiction

Drug abuse affects all of us, and we must act to prevent more unnecessary deaths.

iStockPhoto

It's time to take action against addiction.

In recent weeks, a spate of media attention has once again alerted Americans to our epidemic of narcotic drug abuse – and its destructive and fatal consequences. My recent piece in this publication spoke to the political promise for a response in this country because an epidemic is indifferent to whether a person is Republican, Democrat or independent. We are all besieged by this problem; an epidemic makes no distinctions between white, black, Hispanic or Asian, rich or poor, urban or rural, or young or old.

For the doers among us, we need to decide and act on what can be done to contain this epidemic. Unnecessary deaths can be averted, and we can do far better to protect against the personal, community and economic devastation that addiction wreaks on a society. At the risk of missing a few things, I offer below 10 actions individuals, families and communities (including our policymakers and insurers) can do. These are not meant to be taken in rank order; rather, the more taken, the greater our chances of success.

1. Reduce overdose deaths by providing easy access to naloxone. Naloxone, now available as a nasal spray, immediately blocks the deadly respiratory suppression caused by heroin, methadone and narcotic pain pills (like OxyContin, Percodan and Vicodin), and it should be made easily available to first responders, families and those dependent on narcotics and their friends. In 2014, overdose deaths from prescription pain pills reached nearly 19,000, a more than threefold increase from 2001. Over 47,000 people total overdosed that same year.

2. Identify and crack down on prescribers who are providing large quantities of narcotics in so-called pill mills. Use state prescription databases to identify these prescirbers, and distinguish them from doctors legitimately practicing with populations of pain and cancer patients.

3. Employ TV, radio and social media to educate families about drug-abuse prevention. This has been repeatedly shown to reduce the non-medical use of narcotic pain pills.

4. Establish and implement medical guidelines for the treatment of chronic pain. This can be done through quality improvement techniques and performance improvement strategies.

5. Make problem drug and alcohol use screening a standard of care. Screening for this abuse should be a universal practice, used with adult patients seen in primary care settings to identify and intervene early before addiction sets in and overtakes an individual. Screening, brief intervention and referral for treatment, or SBIRT , is a proven intervention that is generally covered by insurers, including Medicaid and Medicare. This intervention has also been adapted for teenage detection and intervention of drug and alcohol problems.

6. Increase the availability, affordability and access to drug treatment programs. An estimated 80 to 90 percent of individuals who could benefit from treatment are not getting it. Celebrities who can pay vast sums for private treatment programs should not be the only ones able to enter them. The Affordable Care Act requires as an essential service element coverage and parity for mental health and substance use disorders, meaning that insurance benefits for addiction must be equivalent to any other covered general medical condition. The opportunity for proper reimbursement for substance disorder treatment has never been better.

7. Educate doctors, patients and families about what good addiction treatment must include. Medical providers, not just addiction specialists, need to appreciate the underlying neuroscience of addiction and fashion their treatment accordingly. Patients and families need to be far more informed consumers in order to advocate for effective treatments.

8. Expose treatment centers not providing comprehensive treatment for substance abuse as falling below standards of quality of care . 12-Step recovery programs (like Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous) are important as a part of a comprehensive treatment program, but have low rates of effectiveness alone. Treatment options must include motivational enhancement, cognitive-behavioral treatments, relapse prevention, family education and support, wellness efforts and medication to help prevent relapse and maintain sobriety.

9. Promote and pay for the use of medication-assisted treatment. This means that recovery efforts can include medication . The use of medication should not be exhorted as a violation of sobriety. A number of medications now exist for drug and alcohol addiction (tobacco too) that improve rates of abstinence – or reduce use, called harm reduction. These include buprenorphine (Suboxone), methadone, naltrexone (including the 28-day injectable Vivitrol) and naloxone. Let's give people in recovery as good a chance as possible not be drawn into puritanical and outdated notions of recovery.

10. Keep hope alive. People with substance use disorders can recover. That takes good treatment, hard work, ongoing support and keeping hope alive. People with addictions do get on the path to recovery – but it is hard to predict when that will happen. For some it is early, even after one or two rehabilitation programs. For others it may take five, 10 or 20 rehab programs, and the pain and suffering of too many relapses. Persons affected, their families and clinical providers need to sustain hope that recovery can happen during what can be a protracted and very dark time. The darkest moments, the most deadly, are when hope evaporates, which is when exile from family, friends and communities and suicide are more likely.

We surely have an epidemic of drug use and abuse. This country, and others, have successfully faced and overcome many an epidemic. The sooner we act, the more comprehensively we act, the more lives and families will be spared.

Tags: drugs , drug abuse , alcohol , addiction

More Opinion

U.S. Government Accountability Office

The Crisis of Drug Misuse and Federal Efforts to Address It

Earlier this week, many media outlets ran stories highlighting the growing crisis of drug misuse in the United States. Citing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, the New York Times said that more than 100,000 Americans died from drug overdoses during a yearlong period ending in April 2021.

Drug misuse—the use of illicit drugs and the misuse of prescription drugs, such as opioids—has been a persistent and long-standing public health issue in the United States. National rates of drug misuse have increased over the last two decades, and are a serious risk to public health, our society, and the economy.

GAO has issued numerous reports highlighting steps the federal government can take to improve its response to this crisis. In 2019, before the pandemic, we raised this issue as a critical one needing attention and in 2020, we decided to add drug misuse to our High Risk List —a list of areas that need immediate attention. And since then we have been looking at how the pandemic has impacted these issues.

Today’s WatchBlog post looks at our work on the drug misuse crisis, and federal efforts to address it.

The federal strategy

In recent years, the federal government has spent billions of dollars and has enlisted more than a dozen agencies to help address drug misuse and its effects.

The National Drug Control Strategy is the federal effort to reduce substance use disorders through a coordinated national drug control policy. The Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) is responsible for overseeing and coordinating this effort.

Our work has identified deficiencies in the most recent iterations of the Strategy, which could serve as an action plan for addressing this high-risk area. In December 2019 , we recommended that ONDCP develop and implement key planning elements, like resource investments and roles and responsibilities, to help it structure its ongoing efforts and to better position the agency to meet statutory requirements for future iterations of the Strategy.

In November 2020 , we recommended that agencies clarify how their programs help to achieve specific goals of the Strategy.

The availability of treatment and recovery programs

As drug misuse has increased, so has demand for treatment and care. But in December 2020 , we reported that treatment availability has not kept pace with need. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) told us that while drug misuse is widespread, nearly one-third of U.S. counties (31%) did not have facilities offering any level of substance use disorder treatment.

Some key barriers in addressing demand for treatment include workforce shortages, insurance reimbursement and payment models, federal and state requirements, and the stigma of drug abuse.

SAMHSA administers grant programs aimed at expanding access to treatment for substance misuse. But we found that the data SAMHSA relies on to understand the impact of its awards and efforts was unreliable because it included both individuals who received treatments funded by its grant programs and those who didn’t. We recommended that it improve the quality of data it uses.

After treatment, there are some federal programs for those recovering from drug misuse. For example, the Department of Labor (Labor) provides grants to states to address the employment and training needs of those affected by and recovering from substance use disorders.

In May 2020 , we recommended that Labor share information, such as lessons learned, from states participating in the program with all states, tribal governments, and outlying areas. Labor agreed with our recommendation.

Monitoring the impact of federal efforts

Our past work has identified gaps in the availability and reliability of data for measuring the federal government’s progress with addressing drug misuse.

For example, ONDCP and other federal, state, and local government officials have identified challenges with the timeliness, accuracy, and accessibility of data on overdose cases (both fatal and non-fatal) from law enforcement and public health sources. In March 2018 , we recommended that ONDCP lead a review on ways to improve overdose data.

ONDCP is also responsible for evaluating the effectiveness of national drug control policy efforts across the government. But, in March 2020 , we reported that ONDCP had not fully developed performance evaluation plans to measure progress against each of the Strategy’s long-range goals, as required by law.

Without effective long-term plans that clearly articulate goals and objectives as well as specific measures to track performance, federal agencies cannot fully assess whether taxpayer dollars are invested in ways that will achieve desired outcomes, such as reducing access to illicit drugs and expanding treatment for substance use disorders.

COVID-19’s effects on drug misuse and new federal assistance

It’s not yet known just how much the pandemic has impacted mental health and substance use. But, in September 2020, SAMHSA reported opioid overdose deaths have increased in some areas of the country by as much as 25% to 50% during the pandemic compared to the previous year.

In March 2021 , we reported on the effects that the COVID-19 pandemic was having on demand for behavioral health services, including mental health and substance use disorders. The added stressors caused by the pandemic—such as feelings of isolation and financial stress—have contributed to increases in emergency room visits for overdoses and suicide attempts and requests for other behavioral health services. Our podcast with GAO health care expert John Dicken discusses this report.

Under the CARES Act and other subsequent pandemic relief acts, SAMHSA was appropriated around $8 billion for behavioral health services, which include substance abuse prevention and treatment services and community mental health services, among other activities. For example, specific funds are available for the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic Expansion Grant program while other funds can be spent to address emergency substance abuse or mental health needs in local communities.

Our work monitoring the federal response to the drug misuse crisis is ongoing, but to learn more about our findings and recommendations so far, visit our High Risk page on this issue.

- Comments on GAO’s WatchBlog? Contact [email protected] .

GAO Contacts

Related Posts

For World Health Day (April 7), We Look At U.S. Efforts to Promote Global Wellness

American Credit Card Debt Hits a New Record—What’s Changed Post-Pandemic?

In the Next Pandemic Antiviral Drugs Could Be Key, But Are They Ready?

Related products, drug misuse: sustained national efforts are necessary for prevention, response, and recovery, product number, drug misuse: agencies have not fully identified how grants that can support drug prevention education programs contribute to national goals, drug misuse: most states have good samaritan laws and research indicates they may have positive effects, drug control: the office of national drug control policy should develop key planning elements to meet statutory requirements, substance use disorder: reliable data needed for substance abuse prevention and treatment block grant program, workforce innovation and opportunity act: additional dol actions needed to help states and employers address substance use disorder, illicit opioids: while greater attention given to combating synthetic opioids, agencies need to better assess their efforts, behavioral health: patient access, provider claims payment, and the effects of the covid-19 pandemic.

GAO's mission is to provide Congress with fact-based, nonpartisan information that can help improve federal government performance and ensure accountability for the benefit of the American people. GAO launched its WatchBlog in January, 2014, as part of its continuing effort to reach its audiences—Congress and the American people—where they are currently looking for information.

The blog format allows GAO to provide a little more context about its work than it can offer on its other social media platforms. Posts will tie GAO work to current events and the news; show how GAO’s work is affecting agencies or legislation; highlight reports, testimonies, and issue areas where GAO does work; and provide information about GAO itself, among other things.

Please send any feedback on GAO's WatchBlog to [email protected] .

What led to the opioid crisis—and how to fix it

February 9, 2022 – Without urgent intervention, 1.2 million people in the U.S. and Canada will die from opioid overdoses by the end of the decade, in addition to the more than 600,000 who have died since 1999, according to a February 2 report from the Stanford-Lancet Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis. In this Big 3 Q&A, Howard Koh , professor of the practice of public health leadership and a member of the Commission, discusses factors contributing to the crisis and recommendations on how to curb it.

Q: What was the impetus behind this new report on the opioid crisis, and why was it important for this commission to issue the report at this time?

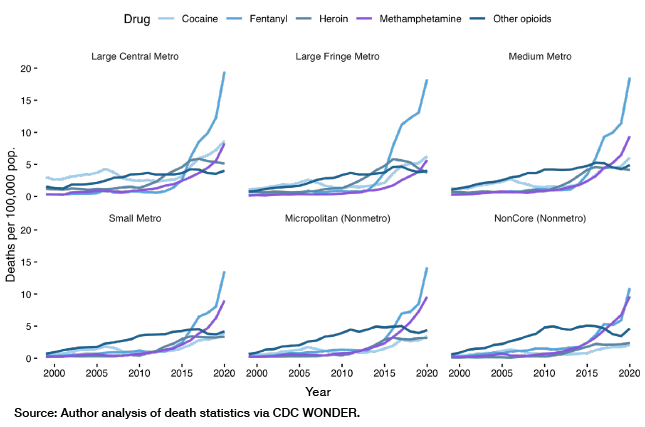

A: The current opioid crisis ranks as one of the most devastating public health catastrophes of our time. It started in the mid-1990s when the powerful agent OxyContin, promoted by Purdue Pharma and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), triggered the first wave of deaths linked to use of legal prescription opioids. Then came a second wave of deaths from a heroin market that expanded to attract already addicted people. More recently, a third wave of deaths has arisen from illegal synthetic opioids like fentanyl. In addition to the crushing public health burden of preventable deaths, millions more are affected by related problems involving homelessness, joblessness, truancy, and family disruption, for example.

The pandemic has both masked and amplified this crisis. Rising death trends are linked to drivers such as the anxiety and isolation of COVID-19 as well as continued lack of access to quality care and prevention. The crisis seems unchecked. It demands an urgent, unified, and comprehensive response.

Q: What were the main drivers of the opioid crisis, and what are the report’s main takeaways on how to minimize the damage?

A: One major conclusion is that the crisis represents a multi-system failure of regulation. OxyContin approval is one example—Purdue Pharma was later shown to have presented a fraudulent description of the drug as less addictive than other opioids. The profit motive of the pharmaceutical industry remains ever present.

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Post-approval, it’s usually left up to industry—not regulators—to educate and advise prescribers on how to evaluate and mitigate risk. Donations from opioid manufacturers to politicians continue to influence policy decisions. In addition, a revolving door of officials leaving government regulatory agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Agency regularly join the pharmaceutical industry with little to no “cooling off” periods. The report details these and other glaring examples.

The report recommends ways to curb pharmaceutical industry influence while also upholding quality care that balances benefits and risks for people with chronic pain. We must continue progress in promoting opioid stewardship—safer prescribing initiatives led by physicians.

Care, treatment, and prevention are all absolutely critical. Currently, addiction care, for example, is not only often separate from mainstream medicine but also unequal. It is also often clouded by stigma, uneven quality, and inaccessibility. Addiction remains a constant long-term threat to human health and won’t respond to only short-term fixes or short-term funding. We have to fully integrate addiction care into mainstream health care, provide enduring and sustained funding, and assure that both public and private insurance cover the full range of addiction services. Parity laws require that most private health plans cover substance use disorder services and not limit them more stringently than services associated with other medical conditions. But such laws are not always followed and that must change.

Addiction training should be an essential part of all health professional education. The public health community can also work with the criminal justice system to move more affected people away from incarceration and towards treatment.

And prevention, starting with kids, is absolutely key. We have to support stronger and more resilient children and families to address threats from opioids, tobacco, alcohol, and other substances that rob so many people of well-being.

Q: When you look at the current state of this crisis, does anything give you hope?

We can see progress in some vital areas. For example, more health professionals are using the term “substance use disorder” instead of “substance abuse” to recognize the condition as a medical and health issue and not a moral failing. And instead of references to people being “clean” or “dirty,” people are increasingly using the medical terms “recovery” and “relapse.” It’s gratifying to see this change in the language of addiction.

The Affordable Care Act has also helped in major ways, starting by requiring that private insurance plans cover substance use disorder services as part of essential health benefits. It also has facilitated expansion of Medicaid, the single largest payer of opioid use disorder services. The report notes that states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility have shown evidence of decreased overdose deaths and increased receipt of treatment.

It is inspiring to celebrate the estimated 25 million people who are in recovery. People in recovery are heroes for me. So many have been able to rebuild relationships with people they care for, contribute again to society, and regain a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives. It may seem to be a hopeless situation but it’s not. In the midst of this terrible crisis, that’s what gives me the greatest hope for the future.

– Karen Feldscher

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

How to Overcome Drug Addiction

Treatment options.

- Steps to Take

Intervention

Frequently asked questions.

Drug addiction, or substance use disorder (SUD), is when someone continues using a drug despite harmful consequences to their daily functioning, relationships, or health. Using drugs can change brain structure and functioning, particularly in areas involved in reward, stress, and self-control. These changes make it harder for people to stop using even when they really want to.

Drug addiction is dangerous because it becomes all-consuming and disrupts the normal functioning of your brain and body. When a person is addicted, they prioritize using the drug or drugs over their wellbeing. This can have severe consequences, including increased tolerance to the substance, withdrawal effects (different for each drug), and social problems.

Verywell / Ellen Lindner

Recovering from SUD is possible, but it takes time, patience, and empathy. A person may need to try quitting more than once before maintaining any length of sobriety.

This article discusses how drug addiction is treated and offers suggestions for overcoming drug addiction.

How Common Is Addiction?

Over 20 million people aged 12 or older had a substance use disorder in 2018.

Substance use disorders are treatable. The severity of addiction and drug or drugs being used will play a role in which treatment plan is likely to work the best. Treatment that addresses the specific situation and any co-occurring medical, psychiatric, and social problems is optimal for leading to long-term recovery and preventing relapse.

Detoxification

Drug and alcohol detoxification programs prepare a person for treatment in a safe, controlled environment where withdrawal symptoms (and any physical or mental health complications) can be managed. Detox may occur in a hospital setting or as a first step to the inpatient or outpatient rehabilitation process.

Going through detox is a crucial step in recovery, and it's these first few weeks that are arguably most critical because they are when the risk of relapse is highest.

Detox Is Not Stand-Alone Treatment

Detoxification is not equivalent to treatment and should not be solely relied upon for recovery.

Counseling gets at the core of why someone began using alcohol or drugs, and what they can do to make lasting changes. This may include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), in which the patient learns to recognize problematic thinking, behaviors, and patterns and establish healthier ways of coping. CBT can help someone develop stronger self-control and more effective coping strategies.

Counseling may also involve family members to develop a deeper understanding of substance use disorder and improve overall family functioning.

Cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown effective in helping people overcome addiction. In one study, 60% of people with cocaine use dependence who underwent CBT along with prescription medication provided cocaine-free toxicology screens a year after their treatment.

Medication can be an effective part of a larger treatment plan for people who have nicotine use disorder, alcohol use disorder, or opioid use disorder. They can be used to help control drug cravings, relieve symptoms of withdrawal, and to help prevent relapses.

Current medications include:

- Nicotine use disorder : A nicotine replacement product (available as patches, gum, lozenges, or nasal spray) or an oral medication, such Wellbutrin (bupropion) and Zyban (varenicline)

- Alcohol use disorder : Campral (acamprosate), Antabuse (disulfiram), and ReVia and Vivitrol (naltrexone).

- Opioid use disorder : Dolophine and Methados (methadone), buprenorphine, ReVia and Vivitrol (naltrexone), and Lucemyra (lofexidine).

Lofexidine was the first medication approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat opioid withdrawals. Compared to a placebo (a pill with no therapeutic value), it significantly reduces symptoms of withdrawal and may cause less of a drop in blood pressure than similar agents.

Support Groups

Support groups or self-help groups can be part of in-patient programs or available for free use in the community. Well-known support groups include narcotics anonymous (NA), alcoholics anonymous (AA), and SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Recovery Training).

Roughly half of all adults being treated for substance use disorders in the United States participated in self-help groups in 2017.

Online Support Group Options

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, these groups that were often out of reach to many are now available online around the clock through video meetings. Such groups are not considered part of a formal treatment plan, but they are considered as useful in conjunction with professional treatment.

Other Options

Due to the complex nature of any substance use disorder, other options for treatment should also include evaluation and treatment for co-occurring mental health issues such as depression and anxiety (known as dual diagnosis).

Follow-up care or continuing care is also recommended, which includes ongoing community- or family-based recovery support systems.

Substance Use Helpline

If you or a loved one are struggling with substance use or addiction, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Steps for Overcoming Drug Addiction

Bear in mind that stopping taking drugs is only one part of recovery from addiction. Strategies that help people stay in treatment and follow their recovery plan are essential. Along with medical and mental health treatments, the following are steps you can take to help overcome substance use disorder.

Commit to Change

Committing to change includes stages of precontemplation and contemplation where a person considers changing, cutting down, moderating, or quitting the addictive behavior. Afterward, committing to change can look like working with a professional in identifying specific goals, coming up with a specific plan to create change, following through with that plan, and revising goals as necessary.

Surround Yourself With Support

Enlisting positive support can help hold you accountable to goals. SAMHSA explains that family and friends who are supportive of recovery can help someone change because they can reinforce new behaviors and provide positive incentives to continue with treatment.

Eliminate Triggers

Triggers can be any person, place, or thing that sparks the craving for using. Common triggers include places you've done drugs, friends you've used with, and anything else that brings up memories of your drug use.

You may not be able to eliminate every trigger, but in the early stages of recovery it's best to avoid triggers to help prevent cravings and relapse .

Find Healthier Ways to Cope With Stress

Stress is a known risk factor or trigger for drug use. Managing stress in healthy ways means finding new ways of coping that don’t involve drug use.

Tips to Cope With Stress

Coping with stress includes:

- Putting more focus on taking care of yourself (eating a balanced diet, getting adequate sleep, and exercising)

- Concentrating on one challenge at a time to avoid becoming overwhelmed

- Stepping away from triggering scenarios

- Learning to recognize and communicate emotions

Learn More: Strategies for Stress Relief

Cope With Withdrawal

Coping with withdrawal may require hospitalization or inpatient care to ensure adequate supervision and medical intervention as necessary. This isn’t always the case, though, because different drugs have different withdrawal symptoms. The severity of use also plays a role, so knowing what to expect—and when to seek emergency help—is important.

For example, a person withdrawing from alcohol can experience tremors (involuntary rhythmic shaking), dehydration, and increased heart rate and blood pressure. On the more extreme end, they can experience seizures (sudden involuntary electrical disturbance in the brain), hallucinations (seeing, hearing, smelling, or tasting things that do not actually exist outside the mind), and delirium (confusion and reduced awareness of one's environment).

Withdrawing from drugs should be done under the guidance of a medical professional to ensure safety.

Deal With Cravings

Learning to deal with cravings is a skill that takes practice. While there are several approaches to resisting cravings, the SMART recovery programs suggest the DEADS method:

- D elay use because urges disappear over time.

- E scape triggering situations.

- A ccept that these feelings are normal and will pass.

- D ispute your irrational “need” for the drug.

- S ubstitute or find new ways of coping instead of using.

Avoid Relapse

The relapse rate for substance use disorders is similar to other illnesses and estimated to be between 40%–60%. The most effective way to avoid relapse and to cope with relapse is to stick with treatment for an adequate amount of time (no less than 90 days). Longer treatment is associated with more positive outcomes. Still, relapse can happen and should be addressed by revising the treatment plan as needed with medical and mental health professionals.

An intervention is an organized effort to intervene in a person's addiction by discussing how their drinking, drug use, or addiction-related behavior has affected everyone around them.

How Does an Intervention Work?

An intervention includes trained professionals like a drug and alcohol counselor, therapist, and/or interventionist who can help guide a family through the preparation and execution. It occurs in a controlled setting (not in the person’s home or family home). Intervention works by confronting the specific issues and encouraging the person to seek treatment.

Who Should Be Included at an Intervention?

Depending on the situation, interventions can include the following people:

- The person with the substance use disorder

- Friends and family

- A therapist

- A professional interventionist

The Association of Intervention Specialists (AIS) , Family First Interventions , and the Network of Independent Interventionists are three organizations of professional interventionists.

You may also want to consider if anyone in the list of friends and family should not be included. Examples are if a person is dealing with their own addiction and may not be able to maintain sobriety, is overly self-motivated or self-involved, or has a strained relationship with the person the intervention is for.

What Should Be Said During an Intervention?

While a person is free to say anything they want during an intervention, it’s best to be prepared with a plan to keep things positive and on track. Blaming, accusing, causing guilt, threatening, or arguing isn’t helpful.

Whatever is said during an intervention should be done so with the intention of helping the person accept help.

Bear in mind that setting boundaries such as “I can no longer give you money if you continue to use drugs,” is not the same as threatening a person with punishment.

Overcoming drug addiction is a process that requires time, patience, and empathy. A person will want to consider actions they can take such as committing to change, seeking support, and eliminating triggers. Depending on the addiction, medications may also be available to help.

Loved ones who are concerned about a person’s drug or alcohol use may consider an intervention . Interventions are meant to encourage treatment. Ongoing support and follow-up care are important in the recovery process to prevent relapse.

A Word From Verywell

No one grows up dreaming of becoming addicted to a substance. If someone you love is experiencing a substance use disorder, please bear in mind that they have a chronic illness and need support and help. Learning about addiction and how not to enable a person is one way you can help them. Having the ongoing support of loved ones and access to professionals can make all the difference.

Helping someone overcome drug addiction requires educating yourself on the drug and on substance use disorder, not enabling the person's use, avoiding having unrealistic expectations of their immediate recovery and change, practicing patience and empathy, and encouraging the person to seek and stick with professional treatment.

Common signs of drug addiction include:

- Drug-seeking behaviors

- Drug cravings

- Using drugs despite the negative consequences

- Being unable to cut back or stop using

Overcoming drug addiction is a complex process that can occur at different paces for different people. There are 30-, 60-, and 90-day treatment programs, but even afterwards a person can benefit from follow-up care or continued care in the form of support groups or personalized therapy. These can get at the root of what was causing the person to start using.

American Psychological Association. What is addiction? .

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health .

Manning V, Garfield JBB, Staiger PK, et al. Effect of cognitive bias modification on early relapse among adults undergoing inpatient alcohol withdrawal treatment: a randomized clinical trial . JAMA Psychiatry . 2020 ;78(2):133-140. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.3446

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of drug addiction treatment: A research-based guide; Cognitive behavioral therapy .

McHugh RK, Hearon BA, Otto MW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders . Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2010;33(3):511-525. doi:10.1016%2Fj.psc.2010.04.012

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of effective treatment.

Fishman M, Tirado C, Alam D, Gullo K, Clinch T, Gorodetzky CW. Safety and efficacy of lofexidine for medically managed opioid withdrawal: a randomized controlled clinical trial . Journal of Addiction Medicine . 2019;13(3):169-176. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000474

Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Results from the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: detailed tables . Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Wen H, Druss BG, Saloner B. Self-help groups and medication use in opioid addiction treatment: A national analysis . Health Aff (Millwood) . May;39(5):740-746. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01021

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Treatment approaches for addiction .

Lassiter PS, Culbreth JR. Theory and Practice of Addiction Counseling . SAGE Publications; 2017.

SAMHSA. Enhancing motivation for change in substance use disorder treatment .

Mental Health America. How can I stop using drugs? .

NIDA and Scholastic. Stress and drug abuse .

Clinical Guidelines for Withdrawal Management and Treatment of Drug Dependence in Closed Settings . 4, Withdrawal Management. Geneva:World Health Organization; 2009.

SMART Recovery. 5 ways to deal with urges and cravings .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Treatment and recovery .

National Institute on Drug Abuse. How long does drug addiction treatment usually last? .

Association of Intervention Specialists. Intervention-A starting point for change .

Cornerstone of Recovery. Things not to do during an intervention for a drug addict or an alcoholic.

By Michelle Pugle Pulge is a freelance health writer focused on mental health content. She is certified in mental health first aid.

A monthly newsletter from the National Institutes of Health, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Search form

Print this issue

Dealing with Drug Problems

Preventing and Treating Drug Abuse

Drug abuse can be a painful experience—for the person who has the problem, and for family and friends who may feel helpless in the face of the disease. But there are things you can do if you know or suspect that someone close to you has a drug problem.

Certain drugs can change the structure and inner workings of the brain. With repeated use, they affect a person’s self-control and interfere with the ability to resist the urge to take the drug. Not being able to stop taking a drug even though you know it’s harmful is the hallmark of addiction.

A drug doesn’t have to be illegal to cause this effect. People can become addicted to alcohol, nicotine, or even prescription drugs when they use them in ways other than prescribed or use someone else’s prescription.

People are particularly vulnerable to using drugs when going through major life transitions. For adults, this might mean during a divorce or after losing a job. For children and teens, this can mean changing schools or other major upheavals in their lives.

But kids may experiment with drug use for many different reasons. “It could be a greater availability of drugs in a school with older students, or it could be that social activities are changing, or that they are trying to deal with stress,” says Dr. Bethany Deeds, an NIH expert on drug abuse prevention. Parents may need to pay more attention to their children during these periods.

The teenage years are a critical time to prevent drug use. Trying drugs as a teenager increases your chance of developing substance use disorders. The earlier the age of first use, the higher the risk of later addiction. But addiction also happens to adults. Adults are at increased risk of addiction when they encounter prescription pain-relieving drugs after a surgery or because of a chronic pain problem. People with a history of addiction should be particularly careful with opioid pain relievers and make sure to tell their doctors about past drug use.

There are many signs that may indicate a loved one is having a problem with drugs. They might lose interest in things that they used to enjoy or start to isolate themselves. Teens’ grades may drop. They may start skipping classes.

“They may violate curfew or appear irritable, sedated, or disheveled,” says child psychiatrist Dr. Geetha Subramaniam, an NIH expert on substance use. Parents may also come across drug paraphernalia, such as water pipes or needles, or notice a strange smell.

“Once drug use progresses, it becomes less of a social thing and more of a compulsive thing—which means the person spends a lot of time using drugs,” Subramaniam says.

If a loved one is using drugs, encourage them to talk to their primary care doctor. It can be easier to have this conversation with a doctor than a family member. Not all drug treatment requires long stays in residential treatment centers. For someone in the early stages of a substance use problem, a conversation with a doctor or another professional may be enough to get them the help they need. Doctors can help the person think about their drug use, understand the risk for addiction, and come up with a plan for change.

Substance use disorder can often be treated on an outpatient basis. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy to treat. Substance use disorder is a complicated disease. Drugs can cause changes in the brain that make it extremely difficult to quit without medical help.

For certain substances, it can be dangerous to stop the drug without medical intervention. Some people may need to be in a hospital for a short time for detoxification, when the drug leaves their body. This can help keep them as safe and comfortable as possible. Patients should talk with their doctors about medications that treat addiction to alcohol or opioids, such as heroin and prescription pain relievers.

Recovering from a substance use disorder requires retraining the brain. A person who’s been addicted to drugs will have to relearn all sorts of things, from what to do when they’re bored to who to hang out with. NIH has developed a customizable wallet card to help people identify and learn to avoid their triggers, the things that make them feel like using drugs. You can order the card for free at drugpubs.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brain-wallet-card .

“You have to learn ways to deal with triggers, learn about negative peers, learn about relapse, [and] learn coping skills,” Subramaniam says.

NIH-funded scientists are studying ways to stop addiction long before it starts—in childhood. Dr. Daniel Shaw at the University of Pittsburgh is looking at whether teaching healthy caregiving strategies to parents can help promote self-regulation skills in children and prevent substance abuse later on.

Starting when children are two years old, Shaw’s study enrolls families at risk of substance use problems in a program called the Family Check-Up. It’s one of several parenting programs that have been studied by NIH-funded researchers.

During the program, a parenting consultant visits the home to observe the parents’ relationship with their child. Parents complete several questionnaires about their own and their family’s well-being. This includes any behavior problems they are experiencing with their child. Parents learn which of their children’s problem behaviors might lead to more serious issues, such as substance abuse, down the road. The consultant also talks with the parents about possible ways to change how they interact with their child. Many parents then meet with the consultants for follow-up sessions about how to improve their parenting skills.

Children whose parents are in the program have fewer behavioral problems and do better when they get to school. Shaw and his colleagues are now following these children through their teenage years to see how the program affects their chances of developing a substance abuse problem. You can find video clips explaining different ways parents can respond to their teens on the NIH Family Checkup website at www.drugabuse.gov/family-checkup .

Even if their teen has already started using drugs, parents can still step in. They can keep closer tabs on who their children’s friends are and what they’re doing. Parents can also help by finding new activities that will introduce their children to new friends and fill up the after-school hours—prime time for getting into trouble. “They don’t like it at first,” Shaw says. But finding other teens with similar interests can help teens form new habits and put them on a healthier path.

A substance use problem is a chronic disease that requires lifestyle adjustments and long-term treatment, like diabetes or high blood pressure. Even relapse can be a normal part of the process—not a sign of failure, but a sign that the treatment needs to be adjusted. With good care, people who have substance use disorders can live healthy, productive lives.

Related Stories

How Many Is Too Many?

Drug Allergies

Opioid Facts for Parents

How Much Alcohol Is Too Much?

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison Building 31, Room 5B52 Bethesda, MD 20892-2094 [email protected] Tel: 301-451-8224

Editor: Harrison Wein, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Tianna Hicklin, Ph.D. Illustrator: Alan Defibaugh

Attention Editors: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov .

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits .

Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction Treatment and Recovery

Can addiction be treated successfully.

Yes, addiction is a treatable disorder. Research on the science of addiction and the treatment of substance use disorders has led to the development of research-based methods that help people to stop using drugs and resume productive lives, also known as being in recovery.

Can addiction be cured?

Like treatment for other chronic diseases such as heart disease or asthma, addiction treatment is not a cure, but a way of managing the condition. Treatment enables people to counteract addiction's disruptive effects on their brain and behavior and regain control of their lives.

Does relapse to drug use mean treatment has failed?

No. The chronic nature of addiction means that for some people relapse, or a return to drug use after an attempt to stop, can be part of the process, but newer treatments are designed to help with relapse prevention. Relapse rates for drug use are similar to rates for other chronic medical illnesses. If people stop following their medical treatment plan, they are likely to relapse.

Treatment of chronic diseases involves changing deeply rooted behaviors, and relapse doesn’t mean treatment has failed. When a person recovering from an addiction relapses, it indicates that the person needs to speak with their doctor to resume treatment, modify it, or try another treatment. 52

While relapse is a normal part of recovery, for some drugs, it can be very dangerous—even deadly. If a person uses as much of the drug as they did before quitting, they can easily overdose because their bodies are no longer adapted to their previous level of drug exposure. An overdose happens when the person uses enough of a drug to produce uncomfortable feelings, life-threatening symptoms, or death.

What are the principles of effective treatment?

Research shows that when treating addictions to opioids (prescription pain relievers or drugs like heroin or fentanyl), medication should be the first line of treatment, usually combined with some form of behavioral therapy or counseling. Medications are also available to help treat addiction to alcohol and nicotine.

Additionally, medications are used to help people detoxify from drugs, although detoxification is not the same as treatment and is not sufficient to help a person recover. Detoxification alone without subsequent treatment generally leads to resumption of drug use.

For people with addictions to drugs like stimulants or cannabis, no medications are currently available to assist in treatment, so treatment consists of behavioral therapies. Treatment should be tailored to address each patient's drug use patterns and drug-related medical, mental, and social problems.

What medications and devices help treat drug addiction?

Different types of medications may be useful at different stages of treatment to help a patient stop abusing drugs, stay in treatment, and avoid relapse.

- Treating withdrawal. When patients first stop using drugs, they can experience various physical and emotional symptoms, including restlessness or sleeplessness, as well as depression, anxiety, and other mental health conditions. Certain treatment medications and devices reduce these symptoms, which makes it easier to stop the drug use.

- Staying in treatment. Some treatment medications and mobile applications are used to help the brain adapt gradually to the absence of the drug. These treatments act slowly to help prevent drug cravings and have a calming effect on body systems. They can help patients focus on counseling and other psychotherapies related to their drug treatment.

- Preventing relapse. Science has taught us that stress cues linked to the drug use (such as people, places, things, and moods), and contact with drugs are the most common triggers for relapse. Scientists have been developing therapies to interfere with these triggers to help patients stay in recovery.

Common medications used to treat drug addiction and withdrawal

- Buprenorphine

- Extended-release naltrexone

- Nicotine replacement therapies (available as a patch, inhaler, or gum)

- Varenicline

- Acamprosate

How do behavioral therapies treat drug addiction?

Behavioral therapies help people in drug addiction treatment modify their attitudes and behaviors related to drug use. As a result, patients are able to handle stressful situations and various triggers that might cause another relapse. Behavioral therapies can also enhance the effectiveness of medications and help people remain in treatment longer.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy seeks to help patients recognize, avoid, and cope with the situations in which they're most likely to use drugs.

- Contingency management uses positive reinforcement such as providing rewards or privileges for remaining drugfree, for attending and participating in counseling sessions, or for taking treatment medications as prescribed.

- Motivational enhancement therapy uses strategies to make the most of people's readiness to change their behavior and enter treatment.

- Family therapy helps people (especially young people) with drug use problems, as well as their families, address influences on drug use patterns and improve overall family functioning.

- Twelve-step facilitation (TSF) is an individual therapy typically delivered in 12 weekly session to prepare people to become engaged in 12-step mutual support programs. 12-step programs, like Alcoholic Anonymous, are not medical treatments, but provide social and complementary support to those treatments. TSF follows the 12-step themes of acceptance, surrender, and active involvement in recovery.

How do the best treatment programs help patients recover from addiction?

Stopping drug use is just one part of a long and complex recovery process. When people enter treatment, addiction has often caused serious consequences in their lives, possibly disrupting their health and how they function in their family lives, at work, and in the community.

Because addiction can affect so many aspects of a person's life, treatment should address the needs of the whole person to be successful. Counselors may select from a menu of services that meet the specific medical, mental, social, occupational, family, and legal needs of their patients to help in their recovery.

For more information on drug treatment , see Principles of Drug Addiction Treatment: A Research-Based Guide , and Principles of Adolescent Substance Use Disorder Treatment: A Research-Based Guide .

How do we tackle the opioid crisis?

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, christen linke young and christen linke young deputy assistant to the president for health and veterans affairs - domestic policy council for health and veterans, former fellow - usc-brookings schaeffer initiative for health policy @clinkeyoung abigail durak abigail durak former center coordinator - center for health policy, brookings.

October 18, 2019

Opioids are a class of drugs that affect the brain, including by relieving pain, and they are extremely addictive. Policymakers can combat the opioid epidemic by:

- limiting inappropriate use of prescription opioids;

- reducing the flow of illicit opioids (like heroin);

- helping people seek treatment for opioid misuse; and

- deploying harm reduction tools that blunt the risks of death, illness, or injury.

These strategies are reflected in ongoing work at the federal, state, and local levels.

A Closer Look

Opioids include prescription drugs like oxycodone as well as illicit drugs like heroin. These drugs are extremely addictive. While opioids have existed for hundreds of years, health care providers generally limited their use because of concerns about addiction. However, beginning in the 1990s, a constellation of factors led to increased use of prescription opioids, including growing attention to pain management as an important clinical goal and the manufacture and marketing of a new generation of prescription opioids. The rise in prescriptions was also associated with increased availability of illegal opioids like heroin.

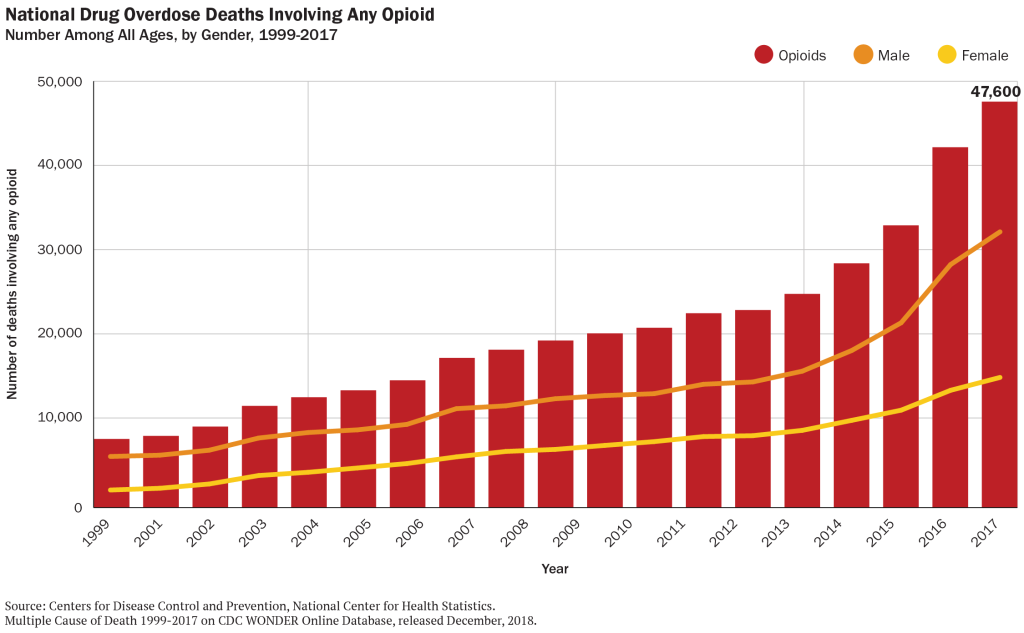

We have seen a dramatic rise in illness and death associated with improper use of opioids. According to federal data:

- 12 million people reported misuse of opioids in 2016.

- Estimates suggest that 2.1 million people struggled with opioid use disorder in 2017.

- Doctors wrote 59 opioid prescriptions per 100 residents in 2017, down from a peak of about 81 per 100 residents in 2010.

- There were 140,000 visits to an emergency room because of an opioid overdose in 2015.

- About 48,000 people died from an opioid overdose in 2017, or about 130 people per day.

For context, the number of deaths from opioid overdose in 2017 is comparable to the number of deaths from HIV-related causes at the height of that epidemic in the 1990s, and is nearly 8 times larger than the number of HIV deaths today.

What can policymakers do to combat the opioid epidemic?

Addressing a public health crisis of this magnitude is a complex undertaking. Policymakers can work to prevent people from becoming addicted to opioids and to help people who are already misusing opioids to treat their addiction and minimize the risk of death or other harm. In general, there are four kinds of strategies:

Limiting prescription opioids

For the last 15 years, physicians have been prescribing opioids at high rates. In a handful of states, there is more than one opioid prescription per person each year. Some overprescribing is the result of “pill mills”—unethical providers who write prescriptions with indifference to clinical need. Other times, patients may be visiting multiple prescribers to seek prescription opioids. And in still other cases, providers may be using prescription opioids to combat pain when other treatments, smaller quantities, or less potent drugs may suffice.

The overuse of prescription opioids fuels the epidemic in two ways. First, it introduces patients (even when taking these drugs as prescribed) to an addictive substance, which creates the risk of subsequently developing opioid use disorder. Second, it creates a flow of opioids that can be diverted from their intended purpose.

Therefore, policymakers can take actions that reduce opportunities for misuse of prescription opioids. These include:

- Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs). 49 states and the District of Columbia have established a PDMP, a statewide database that shows every opioid prescription. Health care providers can check (or be required to check) this database before writing a prescription, allowing them to see if the patient has received opioids from other doctors.

- Prescriber limits. In 2016 the federal government released guidelines for prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care. Consistent with these guidelines, many states have made it unlawful for providers in many circumstances to write opioid prescriptions that exceed a particular strength or that span longer than a few days or weeks.

- Law enforcement. Cracking down on “pill mills” and other unethical and illegal overprescribing behavior by health care providers can have a major impact on the volume of prescription opioids.

- Stakeholder education. Provider education can emphasize the appropriate and limited role of opioids. Similarly, insurance companies can be encouraged to cover non-drug pain therapies and to monitor their own data for early warning signs of opioid misuse or prescriber misconduct.

All of these strategies must balance opioids’ valuable benefits in pain control against the risk of misuse. Policymakers should always be cognizant of the possibility that they could enact too many or the wrong kinds of restrictions and leave patients unnecessarily struggling with unmanaged pain.

Reducing the flow of illicit opioids

Many opioid deaths are associated with illicit opioids like heroin and illegally produced fentanyl. (Fentanyl, in particular, is an extremely potent and deadly opioid, and its use is on the rise .) Although there are no simple solutions, many communities have invested in funding for law enforcement efforts that target large scale opioid distribution.

Collaborative efforts that work across borders and jurisdictions are necessary to share up-to-date information. The federal government has helped facilitate intelligence sharing across agencies, which can help federal, state, and local law enforcement identify and respond to emerging trends. Federal law enforcement agencies have also brought cases against major drug trafficking organizations using this shared information.

In addition, communication among law enforcement, public health professionals, and first responders about distribution patterns can help target public health efforts.

Promoting treatment

A variety of treatment options exist to help people already suffering from opioid use disorder. Experts believe that the most effective treatment for many people will be “medication assisted treatment,” or MAT. MAT involves taking one or more drugs that are intended prevent opioid misuse. These drugs can reduce cravings for opioid misuse or prevent opioids from causing a “high.” (Some of the drugs involved in MAT are themselves opioids.) MAT also involves structured counseling and other support.

Only 17.5 % of people who could benefit from specialized treatment for prescription opioid use disorder received it in 2016. Obstacles to treatment include lack of insurance coverage for treatment, difficulty finding a provider, and patients’ unwillingness to begin treatment. Strategies to promote treatment include:

- Medicaid expansion. In states that have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act , any low-income individual can enroll in Medicaid, where they will have coverage for a wide variety of opioid treatment options. Many studies have linked Medicaid expansion to improved take-up of MAT therapies. Therefore, in states that have not yet expanded, Medicaid expansion can help many people access treatment.

- Payments for opioid treatment. Policymakers can also provide funding for opioid treatment for people who are uninsured or underinsured. This can include supporting treatment directly (like paying for MAT therapies) or subsidizing services like housing support that can make treatment more successful.

- Expanding treatment capacity. Communities can invest in training providers to treat opioid use disorder or supporting the development of new treatment facilities or modalities . Policymakers may also wish to consider updates to policies about how physicians can become certified to prescribe MAT.

- Peer support. There are many successful models of peer support interventions where people in treatment help encourage others with opioid use disorder initiate treatment and offer support throughout recovery. Peer supports can bridge the gap between the clinical treatment setting and everyday life.

- Treatment and the criminal justice system. The federal government has also recently released new guidance to states on MAT in the criminal justice system, suggesting that criminal justice agencies may choose to provide MAT in-house, or partner with community-based providers to deliver treatment to voluntary participants in custody. Establishing relationships with community-based providers can help ensure continuity of care once individuals have been released from incarceration.

The federal government has provided significant grants to states, and states and local communities are also investing their own resources in these kinds of treatment strategies. Policymakers may also recognize that injury and death associated with opioid use has been concentrated in communities experiencing lower rates of economic growth , which can help target treatment investments.

Reducing harm

Finally, policymakers can also focus on “harm reduction” – that is, mitigating the risk that opioid use disorder will cause illness, injury, or death. This includes:

- Naloxone. One of the most important tools is broad availability of naloxone, a drug that can immediately reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. Making naloxone widely available to first responders (including police officers) and to individuals can dramatically reduce the risk of death from overdose.

- Prisons and jails. Individuals recently released from prison are 40 times more likely than others to die of opioid overdose. Making naloxone available to individuals about to be released from incarceration can be a particularly impactful harm reduction strategy.

- Needle exchange. Opioid misuse often involves intravenous drug use, which can lead to transmission of infections like HIV and Hepatitis C. Making clean needles available can reduce the risk of these diseases, and can connect drug users with vital health care services . Needle exchange programs can also link individuals with opioid use disorder to treatment services when they are ready to seek treatment.

Carol Graham

October 15, 2019

October 25, 2018

Dayna Bowen Matthew

January 23, 2018

Economic Studies

Loren Adler, Matthew Fiedler, Richard G. Frank

May 16, 2024

Loren Adler, Matthew Fiedler

May 8, 2024

Keith Humphreys, Christina Andrews, Richard G. Frank

May 6, 2024

With the new President's Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis, we've updated this article which first appeared in August 2016 written by Marty Harding, Director of Training and Consultation, Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation

These are difficult times for many communities. Budgets are being cut; resources are dwindling. Law enforcement personnel, county officials, social services agencies, and healthcare providers are struggling to do more with less. At the same time, the opioid epidemic is devastating families and communities throughout America.

(Editor's Note) With 91 Americans dying each day from opioid overdoses, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have characterized it as an epidemic.

For the past year, I’ve had the opportunity to work in six states to mobilize communities to address this epidemic: Massachusetts, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Kentucky, Florida, and Arkansas. In each state, people from every community sector have shared devastating stories of how they have been affected by opioid use. People who work in emergency rooms of their local hospitals are seeing a flood of overdose patients (from young teens to older adults), and first responders tell of the role they are now playing in saving lives by administering Narcan.

Law enforcement officers talk about their struggle to crack down on dealers and distribution networks. Employers are worried about lost productivity in the workplace due to opioid use. Faith leaders are overwhelmed by the number of deaths in their congregations. Community leaders are concerned about public safety. Educators ask if they’re doing enough to prevent opioid use among adolescents and how to intervene. And probably the most heartbreaking of all the stories are those told by parents who have lost a child to an opioid overdose.

As a local government administrator, you’ve seen and heard it all. Opioid use affects all of the departments you administer: public safety, facility management, transportation, fire and emergency services, and community and economic development. People turn to you for guidance about public policy.

Fortunately, communities are finding solutions to these concerns and working together across sectors to prevent opioid use, intervene, and provide resources for those who are affected by opioid use. This is a critical time for cities and counties to mobilize and provide their communities with vital information and tools to combat heroin and prescription painkiller abuse with the goal of minimizing its social and economic impact.

There is hope! Communities can successfully mobilize and take action.

On August 31, 2016, ICMA conducted a webinar on solutions that cities and counties are implementing to respond to the opioid epidemic. Lee Feldman, 2016-2017 ICMA president, and city manager, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, joined me for this webinar, and we explored these ideas that counties and cities have explored:

- Creating community coalitions to work together across sectors. Managers have joined or started community coalitions that focus directly on the opioid crisis. They have recruited members from such diverse sectors of the community as employers, youth workers, faith community leaders, school administrators, teachers and counselors, public health and human services personnel, treatment professionals, law enforcement and county court services personnel, local pharmacists, and doctors, as well as other committed individuals, including people from the recovering community. These coalitions have joined forces and disseminated relevant information, conducted visioning sessions, developed and implemented action plans, and conducted educational sessions and informational campaigns throughout their communities.

- Developing ordinances and places for safe drug disposal. Generally, these safe disposal sites are located in city halls under the supervision of law enforcement. Although drug take-back days are effective in increasing public awareness of the problem of unwanted prescriptions, a consistent, 24-7 lockbox for safe drug disposal dramatically increases the pounds of unwanted prescriptions that are collected, keeping them out of the hands of children and out of our water and landfills.

- Establishing drug diversion task forces. Dedicated to sharing information and investigations to combat prescription fraud and illegal trafficking of prescription painkillers.

- Providing training for first responders in the use of naloxone (Narcan) for reducing opioid overdoses. This strategy has been successfully implemented in many communities throughout the country, saving countless lives. New intranasal Narcan makes administration easier for both law enforcement and emergency personnel. Stigma about using Narcan still abounds, however, and city/county administrators must be armed with a strong rationale for counteracting negativity toward this approach.

- Using drug courts to fight opioid addiction and trafficking. This approach reduces recidivism, encourages compliance with treatment, and supports families of drug court participants. It also reduces some of the burdens on jails by creating an effective diversion program.

- Creating referral programs through law enforcement agencies. Some communities are trying innovative programs that allow people to voluntarily obtain help by going to the local sheriff’s office and requesting assistance. The community, county, or individual donors often cover the cost of treatment in these instances.

- Disseminating information about state laws that encourage intervention. Good Samaritan laws protect citizens when they intervene to save a life due to an opioid overdose. Drug overdose amnesty laws allow people to call 911 when a friend or family member is overdosing without fear of being arrested themselves for opioid use or possession.

- Building awareness about their state’s prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). These efforts are critical to cutting down on “doctor shopping” and preventing opioid overdoses, but they are underused for a variety of reasons. Cities and counties are involving local doctors and pharmacies to build awareness of PDMPs and remove barriers to implementing them fully.

- Hosting community mobilization events to put tools into the hands of every community sector. Community mobilization events, using Hazelden’s “Toolkit for Community Action,” have reached more than a 1,000 people in the past six months. We’ll share what we’ve learned from these events, and let you know how you can plan and launch an event in your community.

Mobilizing your community doesn’t happen overnight, and it requires hard work. But the return on your investment of time, money, and effort is worth it. Imagine…. If hospital admissions for overdose death decrease. If law enforcement costs are reduced. If employers in your community see a rise in productivity. If violence, theft, and other crimes in your community decrease. If schools are a safer place for your children. If one life is saved. It’s worth it.

Related Resources:

- Podcast: Episode 5--The Opioid Epidemic

- Article: How One City Went "All-In" to Fight the Opioid Epidemic

- Article: Leading the Fight Against the Opioid Crisis

- Article: The Opioid Mission of Broome County, New York

- Blog Post: Virginia Launches New Tool to Combat Heroin, Prescription Opioid Abuse

New, Reduced Membership Dues

A new, reduced dues rate is available for CAOs/ACAOs, along with additional discounts for those in smaller communities, has been implemented. Learn more and be sure to join or renew today!

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Tween and teen health

Teen drug abuse: Help your teen avoid drugs

Teen drug abuse can have a major impact on your child's life. Find out how to help your teen make healthy choices and avoid using drugs.

The teen brain is in the process of maturing. In general, it's more focused on rewards and taking risks than the adult brain. At the same time, teenagers push parents for greater freedom as teens begin to explore their personality.

That can be a challenging tightrope for parents.

Teens who experiment with drugs and other substances put their health and safety at risk. The teen brain is particularly vulnerable to being rewired by substances that overload the reward circuits in the brain.

Help prevent teen drug abuse by talking to your teen about the consequences of using drugs and the importance of making healthy choices.

Why teens use or misuse drugs

Many factors can feed into teen drug use and misuse. Your teen's personality, your family's interactions and your teen's comfort with peers are some factors linked to teen drug use.

Common risk factors for teen drug abuse include:

- A family history of substance abuse.

- A mental or behavioral health condition, such as depression, anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Impulsive or risk-taking behavior.

- A history of traumatic events, such as seeing or being in a car accident or experiencing abuse.

- Low self-esteem or feelings of social rejection.

Teens may be more likely to try substances for the first time when hanging out in a social setting.

Alcohol and nicotine or tobacco may be some of the first, easier-to-get substances for teens. Because alcohol and nicotine or tobacco are legal for adults, these can seem safer to try even though they aren't safe for teens.

Teens generally want to fit in with peers. So if their friends use substances, your teen might feel like they need to as well. Teens also may also use substances to feel more confident with peers.

If those friends are older, teens can find themselves in situations that are riskier than they're used to. For example, they may not have adults present or younger teens may be relying on peers for transportation.

And if they are lonely or dealing with stress, teens may use substances to distract from these feelings.

Also, teens may try substances because they are curious. They may try a substance as a way to rebel or challenge family rules.

Some teens may feel like nothing bad could happen to them, and may not be able to understand the consequences of their actions.

Consequences of teen drug abuse

Negative consequences of teen drug abuse might include:

- Drug dependence. Some teens who misuse drugs are at increased risk of substance use disorder.

- Poor judgment. Teenage drug use is associated with poor judgment in social and personal interactions.

- Sexual activity. Drug use is associated with high-risk sexual activity, unsafe sex and unplanned pregnancy.

- Mental health disorders. Drug use can complicate or increase the risk of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

- Impaired driving. Driving under the influence of any drug affects driving skills. It puts the driver, passengers and others on the road at risk.

- Changes in school performance. Substance use can result in worse grades, attendance or experience in school.

Health effects of drugs

Substances that teens may use include those that are legal for adults, such as alcohol or tobacco. They may also use medicines prescribed to other people, such as opioids.

Or teens may order substances online that promise to help in sports competition, or promote weight loss.

In some cases products common in homes and that have certain chemicals are inhaled for intoxication. And teens may also use illicit drugs such as cocaine or methamphetamine.

Drug use can result in drug addiction, serious impairment, illness and death. Health risks of commonly used drugs include the following:

- Cocaine. Risk of heart attack, stroke and seizures.

- Ecstasy. Risk of liver failure and heart failure.

- Inhalants. Risk of damage to the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys from long-term use.

- Marijuana. Risk of impairment in memory, learning, problem-solving and concentration; risk of psychosis, such as schizophrenia, hallucination or paranoia, later in life associated with early and frequent use. For teens who use marijuana and have a psychiatric disorder, there is a risk of depression and a higher risk of suicide.

- Methamphetamine. Risk of psychotic behaviors from long-term use or high doses.

- Opioids. Risk of respiratory distress or death from overdose.

- Electronic cigarettes (vaping). Higher risk of smoking or marijuana use. Exposure to harmful substances similar to cigarette smoking; risk of nicotine dependence. Vaping may allow particles deep into the lungs, or flavorings may include damaging chemicals or heavy metals.

Talking about teen drug use

You'll likely have many talks with your teen about drug and alcohol use. If you are starting a conversation about substance use, choose a place where you and your teen are both comfortable. And choose a time when you're unlikely to be interrupted. That means you both will need to set aside phones.

It's also important to know when not to have a conversation.

When parents are angry or when teens are frustrated, it's best to delay the talk. If you aren't prepared to answer questions, parents might let teens know that you'll talk about the topic at a later time.

And if a teen is intoxicated, wait until the teen is sober.

To talk to your teen about drugs:

- Ask your teen's views. Avoid lectures. Instead, listen to your teen's opinions and questions about drugs. Parents can assure teens that they can be honest and have a discussion without getting in trouble.

- Discuss reasons not to use drugs. Avoid scare tactics. Emphasize how drug use can affect the things that are important to your teen. Some examples might be sports performance, driving, health or appearance.

- Consider media messages. Social media, television programs, movies and songs can make drug use seem normal or glamorous. Talk about what your teen sees and hears.

- Discuss ways to resist peer pressure. Brainstorm with your teen about how to turn down offers of drugs.

- Be ready to discuss your own drug use. Think about how you'll respond if your teen asks about your own drug use, including alcohol. If you chose not to use drugs, explain why. If you did use drugs, share what the experience taught you.

Other preventive strategies

Consider other strategies to prevent teen drug abuse:

- Know your teen's activities. Pay attention to your teen's whereabouts. Find out what adult-supervised activities your teen is interested in and encourage your teen to get involved.

- Establish rules and consequences. Explain your family rules, such as leaving a party where drug use occurs and not riding in a car with a driver who's been using drugs. Work with your teen to figure out a plan to get home safely if the person who drove is using substances. If your teen breaks the rules, consistently enforce consequences.

- Know your teen's friends. If your teen's friends use drugs, your teen might feel pressure to experiment, too.

- Keep track of prescription drugs. Take an inventory of all prescription and over-the-counter medications in your home.

- Provide support. Offer praise and encouragement when your teen succeeds. A strong bond between you and your teen might help prevent your teen from using drugs.

- Set a good example. If you drink, do so in moderation. Use prescription drugs as directed. Don't use illicit drugs.

Recognizing the warning signs of teen drug abuse

Be aware of possible red flags, such as:

- Sudden or extreme change in friends, eating habits, sleeping patterns, physical appearance, requests for money, coordination or school performance.

- Irresponsible behavior, poor judgment and general lack of interest.

- Breaking rules or withdrawing from the family.

- The presence of medicine containers, despite a lack of illness, or drug paraphernalia in your teen's room.

Seeking help for teen drug abuse

If you suspect or know that your teen is experimenting with or misusing drugs:

- Plan your action. Finding out your teen is using drugs or suspecting it can bring up strong emotions. Before talking to your teen, make sure you and anyone who shares caregiving responsibility for the teen is ready. It can help to have a goal for the conversation. It can also help to figure out how you'll respond to the different ways your teen might react.