TRY OUR FREE APP

Write your book in Reedsy Studio. Try the beloved writing app for free today.

Craft your masterpiece in Reedsy Studio

Plan, write, edit, and format your book in our free app made for authors.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 20, 2023

Creative Nonfiction: How to Spin Facts into Narrative Gold

Creative nonfiction is a genre of creative writing that approaches factual information in a literary way. This type of writing applies techniques drawn from literary fiction and poetry to material that might be at home in a magazine or textbook, combining the craftsmanship of a novel with the rigor of journalism.

Here are some popular examples of creative nonfiction:

- The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang

- Intimations by Zadie Smith

- Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri

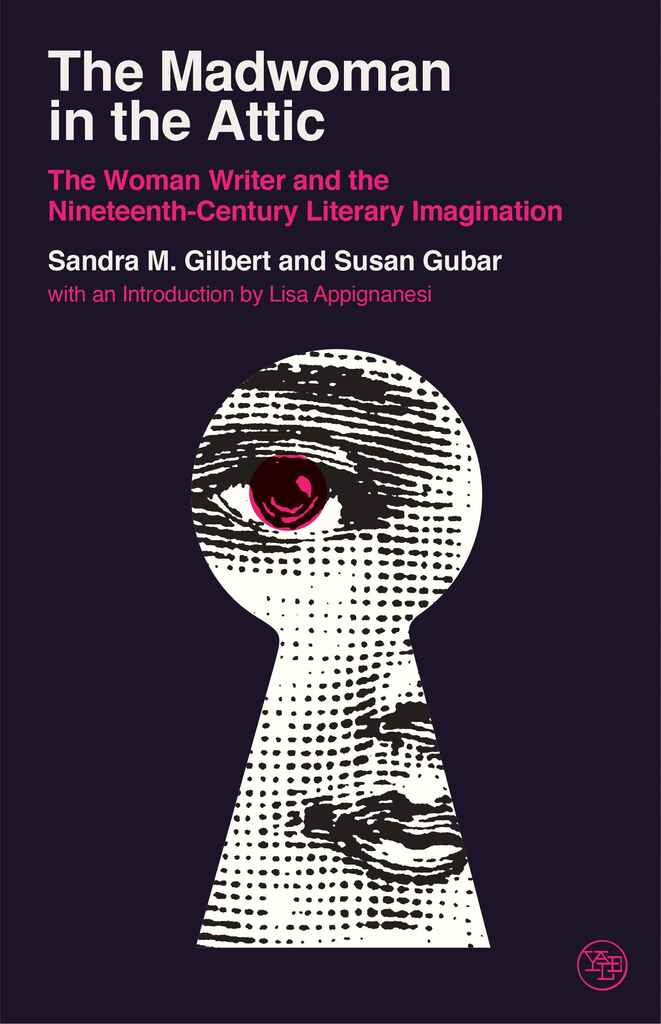

- The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

- I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino

Creative nonfiction is not limited to novel-length writing, of course. Popular radio shows and podcasts like WBEZ’s This American Life or Sarah Koenig’s Serial also explore audio essays and documentary with a narrative approach, while personal essays like Nora Ephron’s A Few Words About Breasts and Mariama Lockington’s What A Black Woman Wishes Her Adoptive White Parents Knew also present fact with fiction-esque flair.

Writing short personal essays can be a great entry point to writing creative nonfiction. Think about a topic you would like to explore, perhaps borrowing from your own life, or a universal experience. Journal freely for five to ten minutes about the subject, and see what direction your creativity takes you in. These kinds of exercises will help you begin to approach reality in a more free flowing, literary way — a muscle you can use to build up to longer pieces of creative nonfiction.

If you think you’d like to bring your writerly prowess to nonfiction, here are our top tips for creating compelling creative nonfiction that’s as readable as a novel, but as illuminating as a scholarly article.

Write a memoir focused on a singular experience

Humans love reading about other people’s lives — like first-person memoirs, which allow you to get inside another person’s mind and learn from their wisdom. Unlike autobiographies, memoirs can focus on a single experience or theme instead of chronicling the writers’ life from birth onward.

For that reason, memoirs tend to focus on one core theme and—at least the best ones—present a clear narrative arc, like you would expect from a novel. This can be achieved by selecting a singular story from your life; a formative experience, or period of time, which is self-contained and can be marked by a beginning, a middle, and an end.

When writing a memoir, you may also choose to share your experience in parallel with further research on this theme. By performing secondary research, you’re able to bring added weight to your anecdotal evidence, and demonstrate the ways your own experience is reflective (or perhaps unique from) the wider whole.

Example: The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking , for example, interweaves the author’s experience of widowhood with sociological research on grief. Chronicling the year after her husband’s unexpected death, and the simultaneous health struggles of their daughter, The Year of Magical Thinking is a poignant personal story, layered with universal insight into what it means to lose someone you love. The result is the definitive exploration of bereavement — and a stellar example of creative nonfiction done well.

📚 Looking for more reading recommendations? Check out our list of the best memoirs of the last century .

Tip: What you cut out is just as important as what you keep

When writing a memoir that is focused around a singular theme, it’s important to be selective in what to include, and what to leave out. While broader details of your life may be helpful to provide context, remember to resist the impulse to include too much non-pertinent backstory. By only including what is most relevant, you are able to provide a more focused reader experience, and won’t leave readers guessing what the significance of certain non-essential anecdotes will be.

💡 For more memoir-planning tips, head over to our post on outlining memoirs .

Of course, writing a memoir isn’t the only form of creative nonfiction that lets you tap into your personal life — especially if there’s something more explicit you want to say about the world at large… which brings us onto our next section.

Pen a personal essay that has something bigger to say

Personal essays condense the first-person focus and intimacy of a memoir into a tighter package — tunneling down into a specific aspect of a theme or narrative strand within the author’s personal experience.

Often involving some element of journalistic research, personal essays can provide examples or relevant information that comes from outside the writer’s own experience. This can take the form of other people’s voices quoted in the essay, or facts and stats. By combining lived experiences with external material, personal essay writers can reach toward a bigger message, telling readers something about human behavior or society instead of just letting them know the writer better.

Example: The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison

Leslie Jamison's widely acclaimed collection The Empathy Exams tackles big questions (Why is pain so often performed? Can empathy be “bad”?) by grounding them in the personal. While Jamison draws from her own experiences, both as a medical actor who was paid to imitate pain, and as a sufferer of her own ailments, she also reaches broader points about the world we live in within each of her essays.

Whether she’s talking about the justice system or reality TV, Jamison writes with both vulnerability and poise, using her lived experience as a jumping-off point for exploring the nature of empathy itself.

Tip: Try to show change in how you feel about something

Including external perspectives, as we’ve just discussed above, will help shape your essay, making it meaningful to other people and giving your narrative an arc.

Ultimately, you may be writing about yourself, but readers can read what they want into it. In a personal narrative, they’re looking for interesting insights or realizations they can apply to their own understanding of their lives or the world — so don’t lose sight of that. As the subject of the essay, you are not so much the topic as the vehicle for furthering a conversation.

Often, there are three clear stages in an essay:

- Initial state

- Encounter with something external

- New, changed state, and conclusions

By bringing readers through this journey with you, you can guide them to new outlooks and demonstrate how your story is still relevant to them.

Had enough of writing about your own life? Let’s look at a form of creative nonfiction that allows you to get outside of yourself.

Tell a factual story as though it were a novel

The form of creative nonfiction that is perhaps closest to conventional nonfiction is literary journalism. Here, the stories are all fact, but they are presented with a creative flourish. While the stories being told might comfortably inhabit a newspaper or history book, they are presented with a sense of literary significance, and writers can make use of literary techniques and character-driven storytelling.

Unlike news reporters, literary journalists can make room for their own perspectives: immersing themselves in the very action they recount. Think of them as both characters and narrators — but every word they write is true.

If you think literary journalism is up your street, think about the kinds of stories that capture your imagination the most, and what those stories have in common. Are they, at their core, character studies? Parables? An invitation to a new subculture you have never before experienced? Whatever piques your interest, immerse yourself.

Example: The Botany of Desire by Michael Pollan

If you’re looking for an example of literary journalism that tells a great story, look no further than Michael Pollan’s The Botany of Desire: A Plant’s-Eye View of the World , which sits at the intersection of food writing and popular science. Though it purports to offer a “plant’s-eye view of the world,” it’s as much about human desires as it is about the natural world.

Through the history of four different plants and human’s efforts to cultivate them, Pollan uses first-hand research as well as archival facts to explore how we attempt to domesticate nature for our own pleasure, and how these efforts can even have devastating consequences. Pollan is himself a character in the story, and makes what could be a remarkably dry topic accessible and engaging in the process.

Tip: Don’t pretend that you’re perfectly objective

You may have more room for your own perspective within literary journalism, but with this power comes great responsibility. Your responsibilities toward the reader remain the same as that of a journalist: you must, whenever possible, acknowledge your own biases or conflicts of interest, as well as any limitations on your research.

Thankfully, the fact that literary journalism often involves a certain amount of immersion in the narrative — that is, the writer acknowledges their involvement in the process — you can touch on any potential biases explicitly, and make it clear that the story you’re telling, while true to what you experienced, is grounded in your own personal perspective.

Approach a famous name with a unique approach

Biographies are the chronicle of a human life, from birth to the present or, sometimes, their demise. Often, fact is stranger than fiction, and there is no shortage of fascinating figures from history to discover. As such, a biographical approach to creative nonfiction will leave you spoilt for choice in terms of subject matter.

Because they’re not written by the subjects themselves (as memoirs are), biographical nonfiction requires careful research. If you plan to write one, do everything in your power to verify historical facts, and interview the subject’s family, friends, and acquaintances when possible. Despite the necessity for candor, you’re still welcome to approach biography in a literary way — a great creative biography is both truthful and beautifully written.

Example: American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin

Alongside the need for you to present the truth is a duty to interpret that evidence with imagination, and present it in the form of a story. Demonstrating a novelist’s skill for plot and characterization, Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s American Prometheus is a great example of creative nonfiction that develops a character right in front of the readers’ eyes.

American Prometheus follows J. Robert Oppenheimer from his bashful childhood to his role as the father of the atomic bomb, all the way to his later attempts to reckon with his violent legacy.

FREE COURSE

How to Develop Characters

In 10 days, learn to develop complex characters readers will love.

The biography tells a story that would fit comfortably in the pages of a tragic novel, but is grounded in historical research. Clocking in at a hefty 721 pages, American Prometheus distills an enormous volume of archival material, including letters, FBI files, and interviews into a remarkably readable volume.

📚 For more examples of world-widening, eye-opening biographies, check out our list of the 30 best biographies of all time .

Tip: The good stuff lies in the mundane details

Biographers are expected to undertake academic-grade research before they put pen to paper. You will, of course, read any existing biographies on the person you’re writing about, and visit any archives containing relevant material. If you’re lucky, there’ll be people you can interview who knew your subject personally — but even if there aren’t, what’s going to make your biography stand out is paying attention to details, even if they seem mundane at first.

Of course, no one cares which brand of slippers a former US President wore — gossip is not what we’re talking about. But if you discover that they took a long, silent walk every single morning, that’s a granular detail you could include to give your readers a sense of the weight they carried every day. These smaller details add up to a realistic portrait of a living, breathing human being.

But creative nonfiction isn’t just writing about yourself or other people. Writing about art is also an art, as we’ll see below.

Put your favorite writers through the wringer with literary criticism

Literary criticism is often associated with dull, jargon-laden college dissertations — but it can be a wonderfully rewarding form that blurs the lines between academia and literature itself. When tackled by a deft writer, a literary critique can be just as engrossing as the books it analyzes.

Many of the sharpest literary critics are also poets, poetry editors , novelists, or short story writers, with first-hand awareness of literary techniques and the ability to express their insights with elegance and flair. Though literary criticism sounds highly theoretical, it can be profoundly intimate: you’re invited to share in someone’s experience as a reader or writer — just about the most private experience there is.

Example: The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar

Take The Madwoman in the Attic by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, a seminal work approaching Victorian literature from a feminist perspective. Written as a conversation between two friends and academics, this brilliant book reads like an intellectual brainstorming session in a casual dining venue. Highly original, accessible, and not suffering from the morose gravitas academia is often associated with, this text is a fantastic example of creative nonfiction.

Tip: Remember to make your critiques creative

Literary criticism may be a serious undertaking, but unless you’re trying to pitch an academic journal, you’ll need to be mindful of academic jargon and convoluted sentence structure. Don’t forget that the point of popular literary criticism is to make ideas accessible to readers who aren’t necessarily academics, introducing them to new ways of looking at anything they read.

If you’re not feeling confident, a professional nonfiction editor could help you confirm you’ve hit the right stylistic balance.

Give your book the help it deserves

The best editors, designers, and book marketers are on Reedsy. Sign up for free and meet them.

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

Is creative nonfiction looking a little bit clearer now? You can try your hand at the genre , or head to the next post in this guide and discover online classes where you can hone your skills at creative writing.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your publishing dreams to life

The world's best editors, designers, and marketers are on Reedsy. Come meet them.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

What is creative nonfiction? Despite its slightly enigmatic name, no literary genre has grown quite as quickly as creative nonfiction in recent decades. Literary nonfiction is now well-established as a powerful means of storytelling, and bookstores now reserve large amounts of space for nonfiction, when it often used to occupy a single bookshelf.

Like any literary genre, creative nonfiction has a long history; also like other genres, defining contemporary CNF for the modern writer can be nuanced. If you’re interested in writing true-to-life stories but you’re not sure where to begin, let’s start by dissecting the creative nonfiction genre and what it means to write a modern literary essay.

What Creative Nonfiction Is

Creative nonfiction employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story.

How do we define creative nonfiction? What makes it “creative,” as opposed to just “factual writing”? These are great questions to ask when entering the genre, and they require answers which could become literary essays themselves.

In short, creative nonfiction (CNF) is a form of storytelling that employs the creative writing techniques of literature, such as poetry and fiction, to retell a true story. Creative nonfiction writers don’t just share pithy anecdotes, they use craft and technique to situate the reader into their own personal lives. Fictional elements, such as character development and narrative arcs, are employed to create a cohesive story, but so are poetic elements like conceit and juxtaposition.

The CNF genre is wildly experimental, and contemporary nonfiction writers are pushing the bounds of literature by finding new ways to tell their stories. While a CNF writer might retell a personal narrative, they might also focus their gaze on history, politics, or they might use creative writing elements to write an expository essay. There are very few limits to what creative nonfiction can be, which is what makes defining the genre so difficult—but writing it so exciting.

Different Forms of Creative Nonfiction

From the autobiographies of Mark Twain and Benvenuto Cellini, to the more experimental styles of modern writers like Karl Ove Knausgård, creative nonfiction has a long history and takes a wide variety of forms. Common iterations of the creative nonfiction genre include the following:

Also known as biography or autobiography, the memoir form is probably the most recognizable form of creative nonfiction. Memoirs are collections of memories, either surrounding a single narrative thread or multiple interrelated ideas. The memoir is usually published as a book or extended piece of fiction, and many memoirs take years to write and perfect. Memoirs often take on a similar writing style as the personal essay does, though it must be personable and interesting enough to encourage the reader through the entire book.

Personal Essay

Personal essays are stories about personal experiences told using literary techniques.

When someone hears the word “essay,” they instinctively think about those five paragraph book essays everyone wrote in high school. In creative nonfiction, the personal essay is much more vibrant and dynamic. Personal essays are stories about personal experiences, and while some personal essays can be standalone stories about a single event, many essays braid true stories with extended metaphors and other narratives.

Personal essays are often intimate, emotionally charged spaces. Consider the opening two paragraphs from Beth Ann Fennelly’s personal essay “ I Survived the Blizzard of ’79. ”

We didn’t question. Or complain. It wouldn’t have occurred to us, and it wouldn’t have helped. I was eight. Julie was ten.

We didn’t know yet that this blizzard would earn itself a moniker that would be silk-screened on T-shirts. We would own such a shirt, which extended its tenure in our house as a rag for polishing silver.

The word “essay” comes from the French “essayer,” which means “to try” or “attempt.” The personal essay is more than just an autobiographical narrative—it’s an attempt to tell your own history with literary techniques.

Lyric Essay

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, but is much more experimental in form.

The lyric essay contains similar subject matter as the personal essay, with one key distinction: lyric essays are much more experimental in form. Poetry and creative nonfiction merge in the lyric essay, challenging the conventional prose format of paragraphs and linear sentences.

The lyric essay stands out for its unique writing style and sentence structure. Consider these lines from “ Life Code ” by J. A. Knight:

The dream goes like this: blue room of water. God light from above. Child’s fist, foot, curve, face, the arc of an eye, the symmetry of circles… and then an opening of this body—which surprised her—a movement so clean and assured and then the push towards the light like a frog or a fish.

What we get is language driven by emotion, choosing an internal logic rather than a universally accepted one.

Lyric essays are amazing spaces to break barriers in language. For example, the lyricist might write a few paragraphs about their story, then examine a key emotion in the form of a villanelle or a ghazal . They might decide to write their entire essay in a string of couplets or a series of sonnets, then interrupt those stanzas with moments of insight or analysis. In the lyric essay, language dictates form. The successful lyricist lets the words arrange themselves in whatever format best tells the story, allowing for experimental new forms of storytelling.

Literary Journalism

Much more ambiguously defined is the idea of literary journalism. The idea is simple: report on real life events using literary conventions and styles. But how do you do this effectively, in a way that the audience pays attention and takes the story seriously?

You can best find examples of literary journalism in more “prestigious” news journals, such as The New Yorker , The Atlantic , Salon , and occasionally The New York Times . Think pieces about real world events, as well as expository journalism, might use braiding and extended metaphors to make readers feel more connected to the story. Other forms of nonfiction, such as the academic essay or more technical writing, might also fall under literary journalism, provided those pieces still use the elements of creative nonfiction.

Consider this recently published article from The Atlantic : The Uncanny Tale of Shimmel Zohar by Lawrence Weschler. It employs a style that’s breezy yet personable—including its opening line.

So I first heard about Shimmel Zohar from Gravity Goldberg—yeah, I know, but she insists it’s her real name (explaining that her father was a physicist)—who is the director of public programs and visitor experience at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, in San Francisco.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Common Elements and Techniques

What separates a general news update from a well-written piece of literary journalism? What’s the difference between essay writing in high school and the personal essay? When nonfiction writers put out creative work, they are most successful when they utilize the following elements.

Just like fiction, nonfiction relies on effective narration. Telling the story with an effective plot, writing from a certain point of view, and using the narrative to flesh out the story’s big idea are all key craft elements. How you structure your story can have a huge impact on how the reader perceives the work, as well as the insights you draw from the story itself.

Consider the first lines of the story “ To the Miami University Payroll Lady ” by Frenci Nguyen:

You might not remember me, but I’m the dark-haired, Texas-born, Asian-American graduate student who visited the Payroll Office the other day to complete direct deposit and tax forms.

Because the story is written in second person, with the reader experiencing the story as the payroll lady, the story’s narration feels much more personal and important, forcing the reader to evaluate their own personal biases and beliefs.

Observation

Telling the story involves more than just simple plot elements, it also involves situating the reader in the key details. Setting the scene requires attention to all five senses, and interpersonal dialogue is much more effective when the narrator observes changes in vocal pitch, certain facial expressions, and movements in body language. Essentially, let the reader experience the tiny details – we access each other best through minutiae.

The story “ In Transit ” by Erica Plouffe Lazure is a perfect example of storytelling through observation. Every detail of this flash piece is carefully noted to tell a story without direct action, using observations about group behavior to find hope in a crisis. We get observation when the narrator notes the following:

Here at the St. Thomas airport in mid-March, we feel the urgency of the transition, the awareness of how we position our bodies, where we place our luggage, how we consider for the first time the numbers of people whose belongings are placed on the same steel table, the same conveyor belt, the same glowing radioactive scan, whose IDs are touched by the same gloved hand[.]

What’s especially powerful about this story is that it is written in a single sentence, allowing the reader to be just as overwhelmed by observation and context as the narrator is.

We’ve used this word a lot, but what is braiding? Braiding is a technique most often used in creative nonfiction where the writer intertwines multiple narratives, or “threads.” Not all essays use braiding, but the longer a story is, the more it benefits the writer to intertwine their story with an extended metaphor or another idea to draw insight from.

“ The Crush ” by Zsofia McMullin demonstrates braiding wonderfully. Some paragraphs are written in first person, while others are written in second person.

The following example from “The Crush” demonstrates braiding:

Your hair is still wet when you slip into the booth across from me and throw your wallet and glasses and phone on the table, and I marvel at how everything about you is streamlined, compact, organized. I am always overflowing — flesh and wants and a purse stuffed with snacks and toy soldiers and tissues.

The author threads these narratives together by having both people interact in a diner, yet the reader still perceives a distance between the two threads because of the separation of “I” and “you” pronouns. When these threads meet, briefly, we know they will never meet again.

Speaking of insight, creative nonfiction writers must draw novel conclusions from the stories they write. When the narrator pauses in the story to delve into their emotions, explain complex ideas, or draw strength and meaning from tough situations, they’re finding insight in the essay.

Often, creative writers experience insight as they write it, drawing conclusions they hadn’t yet considered as they tell their story, which makes creative nonfiction much more genuine and raw.

The story “ Me Llamo Theresa ” by Theresa Okokun does a fantastic job of finding insight. The story is about the history of our own names and the generations that stand before them, and as the writer explores her disconnect with her own name, she recognizes a similar disconnect in her mother, as well as the need to connect with her name because of her father.

The narrator offers insight when she remarks:

I began to experience a particular type of identity crisis that so many immigrants and children of immigrants go through — where we are called one name at school or at work, but another name at home, and in our hearts.

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: the 5 R’s

CNF pioneer Lee Gutkind developed a very system called the “5 R’s” of creative nonfiction writing. Together, the 5 R’s form a general framework for any creative writing project. They are:

- Write about r eal life: Creative nonfiction tackles real people, events, and places—things that actually happened or are happening.

- Conduct extensive r esearch: Learn as much as you can about your subject matter, to deepen and enrich your ability to relay the subject matter. (Are you writing about your tenth birthday? What were the newspaper headlines that day?)

- (W) r ite a narrative: Use storytelling elements originally from fiction, such as Freytag’s Pyramid , to structure your CNF piece’s narrative as a story with literary impact rather than just a recounting.

- Include personal r eflection: Share your unique voice and perspective on the narrative you are retelling.

- Learn by r eading: The best way to learn to write creative nonfiction well is to read it being written well. Read as much CNF as you can, and observe closely how the author’s choices impact you as a reader.

You can read more about the 5 R’s in this helpful summary article .

How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Give it a Try!

Whatever form you choose, whatever story you tell, and whatever techniques you write with, the more important aspect of creative nonfiction is this: be honest. That may seem redundant, but often, writers mistakenly create narratives that aren’t true, or they use details and symbols that didn’t exist in the story. Trust us – real life is best read when it’s honest, and readers can tell when details in the story feel fabricated or inflated. Write with honesty, and the right words will follow!

Ready to start writing your creative nonfiction piece? If you need extra guidance or want to write alongside our community, take a look at the upcoming nonfiction classes at Writers.com. Now, go and write the next bestselling memoir!

Sean Glatch

Thank you so much for including these samples from Hippocampus Magazine essays/contributors; it was so wonderful to see these pieces reflected on from the craft perspective! – Donna from Hippocampus

Absolutely, Donna! I’m a longtime fan of Hippocampus and am always astounded by the writing you publish. We’re always happy to showcase stunning work 🙂

[…] Source: https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-complete-guide-to-writing-creative-nonfiction#5-creative-nonfiction-writing-promptshttps://writers.com/what-is-creative-nonfiction […]

So impressive

Thank you. I’ve been researching a number of figures from the 1800’s and have come across a large number of ‘biographies’ of figures. These include quoted conversations which I knew to be figments of the author and yet some works are lauded as ‘histories’.

excellent guidelines inspiring me to write CNF thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

Writing Creative Nonfiction: Everything That You Need To Know

Creative nonfiction is a genre that includes a wide range of categories and topics, including memoirs, cookbooks, self-help books, and more. Writers in this genre will often blur line between fiction and nonfiction when facts are unavailable or are unclear. The creativity of a good nonfiction writer will enhance the facts and bring a reader into the nonfiction world just as much as if it were a wholly new fiction work. Real life can be pretty interesting on its own, which is why creative nonfiction is such a popular category at book retailers worldwide.

This post will guide you through some key methods for making sure your book is creative and well planned, which leads to success in gaining a following.

Your perspective

What about the nonfiction topic first drew you to it? Why did you decide to write about that topic? The first piece of advice when writing creative nonfiction is to choose a topic you're passionate about! If you are not passionate about the topic, then chances are your readership won't feel the excitement and won't be interested in reading your work. Start with that, and you will have a great foundation for writing your nonfiction book in a creative and engaging way.

When you choose a topic that you have a personal connection to or that you are passionate about, you will be able to show the reader what your personal connection is to that topic. If you're writing a cookbook, for example, include personal stories about each recipe. Show the reader how that food can evoke a similar emotion in them or why that food would be perfect for the upcoming family barbecue. If you're writing a travelogue, include details about your personal experiences at a location, such as special interactions you had with locals or reflective moments drawn out by the unique architectural designs of the area. By giving your readers the human element in your nonfiction work, you are bringing them along with you for the ride.

Even if your book is about computer programming, tie programming principles to other situations that could connect with a broader audience so that more readers will be able to understand the concepts.

Avoid technical jargon

Speaking of computer programming, creative nonfiction doesn't have to be restricted to technical terms. Get creative with your wording while still explaining or describing the correct terminology for that industry. Conceptual understanding of a topic shouldn't require that the reader know the full nomenclature. A reader can learn about the latest cyber security breakthroughs without knowing the specific functions of IIS and the requirements for SOC2 compliance.

If you were writing a biography about a composer and how they developed their orchestrations, you wouldn't necessarily want to use terms like harmonic interval, circle of fifths, secondary dominant, or rootless voicing. Instead, describe those concepts using plain language. For example:

- Instead of this: "Using rootless voicing, Neuford was able to successfully integrate the time's popular jazz into his composition."

- Write this: "By taking out the main note in some of the longer-lasting chords, Neuford weaved the cool essence of jazz into this new composition. This technique is known in the musical community as rootless voicing."

Even when building in some more creative vocabulary, you must remain true to the facts. A nonfiction writer's job is to join facts with a narrative without contradicting those facts. Building a story requires a foundation, and in creative nonfiction that foundation is the truth and a steadfast grasp of the facts being used.

Let's take the example of a book about an unsolved murder that occurred in the 1980s. Witness statements would be an important inclusion in such a book. There are two ways that could go:

- The writer could embellish or change a witness statement to fit a theory they are presenting.

- The writer could present the witness statement as it was and then explain how that could lead to the writer's theory.

The second option is always going to be the best when it comes to writing creative nonfiction. Never change the facts to fit your narrative! You are the writer with creativity and imagination, so adjust your narrative to fit the facts.

Using outlines to build a framework is a huge benefit for all genres. Creative nonfiction is no different. Writers of all types of nonfiction would benefit greatly from starting with the most basic of outlines.

The scaffold should be built from the known facts first. The story can be built around that using first-hand research. Without an outline to start from, all subsequent steps could fall into disarray, leading to mismanaged facts and a disorganized structure. This ultimately is a turn off for readers, especially in nonfiction writing. Even something as simple as a fun cookbook will benefit from having an outline as its starting point.

Going back to our example of a book about an unsolved murder in the 1980s, an outline could help you better understand the theories from that time and will help you figure out how to guide the reader through evidence, witness statements, locations, situations, and other related data connected to the event being covered. Who knows, maybe it could even help solve the murder!

Give accurate credit

Most creative nonfiction is going to include primary and secondary sources. There are various methods for documenting your sources in your work. One method is to use endnotes connected to dialogue or direct quotes used in your text. For example, Kate Colquhoun, in her 2014 book Did She Kill Him? , italicized quotes from historical documents she used and then cited the sources in endnotes.

Another method is to use an evidence file. This method allows you to take a little bit of creative license to increase the drama in your text, but the actual original text is included at the end of the book. This method is a good option because it leaves no room for doubt on what was actually said. The reader can trust that you are providing high quality recreations of situations and dialogue while also being engaged by the heightened drama in the narrative.

In the end, the important part is making sure that you are not plagiarizing, misquoting facts, taking too much creative license, or deliberately misleading your readers.

Disclaimers

If you are writing a memoir or other personal nonfiction work, keep in mind that memory isn't perfect. Furthermore, our perception is unique and may differ significantly from the perception of others involved in events throughout our lives. It's almost impossible to remember each word we had in a conversation, and it gets more difficult the longer time goes on.

While this can benefit a creative nonfiction writer, it is important to remain honest about our inherent limited capabilities with memory. It is good practice to include a disclaimer about what creative liberties you have taken with information or situations you describe. Being upfront is always going to be the right choice over asking for forgiveness later.

Tell the story

Even though you are writing nonfiction, you are still telling a story. Whether your work is a collection of personal essays, a biography, or a career journal, there is still a story being told. Use classic storytelling techniques like bringing characters to life:

- Show, don't tell

- Create suspense

- End with a positive

- The hero's journey

Building your nonfiction narrative in the same manner will keep your reader engaged in the natural suspense that can be offered by real-life events.

A good example of this is nonfiction war stories. In The Good War , author Studs Terkel takes the reader on a vivid journey through history through well-organized and engaging interviews with 121 men and women about their experiences leading up to World War II and during the war. The structure and creativity that Terkel used earned him a Pulitzer Prize.

As a writer, have you grown as a result of your research for your work? Chances are, you have or you will. Tell the reader how the events in your book changed you or how the process of writing about it made you reflect on your own life experiences. Put a piece of yourself into the story and invite your readers to open themselves up to the same. Readers are often looking for connection, and this is the perfect opportunity to open the door and invite them in.

Using these tips, you'll be able to write an engaging, creative, nonfiction work that many people will be excited to read. Focus on your desired audience, be honest, and include yourself in the work. Don't hesitate to indulge your creative side while diving deep into the history or truth of real life experiences. From recipes to tales of the bravery of soldiers, creative nonfiction should connect readers to others through shared feelings of excitement, memory, tragedy, and love.

Header photo by Thought Catalog .

Related Posts

The Ultimate Literary Device List

340 Romance Writing Prompts That Will Sweep Your Readers off Their Feet

- Book Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Academic Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Professional book editing services you can trust

Creative Nonfiction Course Guide (Lisa Heise)

- About Creative Nonfiction

- Writing Creative Nonfiction

- Diane Ackerman

- Joan Didion

- Annie Dillard

- Martin Espada

- Carolyn Forché

- Lee Gutkind

- Maxine Hong-Kingston

- Jane Kramer

- Anne Lamott

- Erik Larson

- Barry Lopez

- Joseph Mitchell

- N. Scott Momaday

- Dinty W. Moore

- Judith Ortiz Cofer

- Lia Purpura

- Robert Root

- David Sedaris

- Michael Steinberg

- Terry Tempest Williams

- Sarah Vowell

- Robin Wall Kimmerer

- Alice Walker

- William Zinsser

- New Yorker Magazine

- Learning Commons

- Writing Center

- Creative Nonfiction OER

Writing Creative Nonfiction - Getting Strated

As a former journalist and current professor of creative nonfiction, I appreciated Michael McGregor's Green-Haired Gumshoes or Hidebound Hacks? Creative Nonfiction vs. Journalism . It reinforces the innate contradictions of this hybrid form. I recently met Lee Gutkind, that hardworking and earnest godfather of the genre, who seems to have no patience for what he calls 'faction' the intentional blending of fact and fiction.

I think intention is the key word, especially with all the fabricated memoirs and fictitious news sources out there. As Roy Peter Clark writes in his essay The Line Between Fact and Fiction in Telling True Stories , "Do not add. Do not deceive." The reader of creative nonfiction--first-person memoir, third-person narrative journalism, or a subgenre--needs to trust the writer or it's all over.

Source: Schneider, Nina R. "In Truth We Trust." Poets & Writers Magazine , vol. 37, no. 3, May-June 2009, p. 11. Gale Literature Resource Center , link.gale.com/apps/doc/A241944062/LitRC?u=la74598&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=9dc3d663. Accessed 21 Aug. 2023.

Image Source: Pixabay

- Green-Haired Gumshoes Or Hidebound Hacks? Creative nonfiction vs. journalism This new generation may include the journalists Moore was warning his audience about, authors like Orlean and Krakauer, Jonathan Harr and Jane Kramer, whose fact-based books are finding a larger readership. What distinguishes them from traditional journalists is that they trust their perceptions, accept that objectivity is a myth, and work hard to communicate the human dimensions of their subjects by using storytelling techniques--a narrative approach, a distinctive voice, scenes and dialogue and setting. | Poets & Writers Magazine(Vol. 37, Issue 2) | Gale Literature Resource Center (Library Database)

- The Line Between Fact and Fiction Journalists should report the truth. Who would deny it? But such a statement does not get us far enough, for it fails to distinguish nonfiction from other forms of expression. Novelists can reveal great truths about the human condition, and so can poets, film makers and painters. Artists, after all, build things that imitate the world. So do nonfiction writers. To make things more complicated, writers of fiction use fact to make their work believable. | by Roy Peter Clark | Creative Nonfiction (Website)

- What Is Creative Nonfiction in Writing? In this post, we look at what creative nonfiction (also known as the narrative nonfiction) is, including what makes it different from other types of fiction and nonfiction writing and more. | Writer's Digest (Website)

Preparing to Write

- Creative Nonfiction Writing by Rita Berman Focuses on creative nonfiction writing. Range of creative nonfiction; Significance of specific details in nonfiction articles; Benefits of incorporating personal observations in nonfiction pieces. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Dec97, Vol. 110 Issue 12, p5. 4p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Preparing to Write by Todd James Pierce The article offers tips regarding narrative nonfiction research. Topics discussed include detail on how to create a robust scene by the help of collect information from newspaper, personal interviews and site visits; exploring narrative material for creation of important moment of tension, desire and conflict; and creating a correct point of views by the help of research about nonfictional narration. | Writer (Madavor Media). Apr2017, Vol. 130 Issue 4, p14-19. 6p. | MasterFILE Complete (EBSCO) (Library Database)

Story / Story Narrative

- Creative Nonfiction: Where Journalism and Storytelling Meet by Mark Masse Discusses the traits needed for writing creative nonfiction narratives. Credibility of story; Choice of appropriate subject; Generation of story from facts; Structuring of dramatic scenes. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Oct95, Vol. 108 Issue 10, p13. 4p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Finding Meaning by. Jack Hart. Stresses the need for news stories to make basic facts meaningful by placing them in the context of social responsibility theory. Use of historical connections as an approach to news writing; Use of parameters; Showing of relationships between things and creating a broad base of knowledge organized into meaningful patterns. | Editor & Publisher. 7/9/94, Vol. 127 Issue 28, p5. 1p. | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Storytelling by Jack Hart. Discusses the return of storytelling in newspaper reporting. Literary-style stories' focus on a protagonist; Scenic construction technique of story writing; Effort required of writers, editors, photographers and others involved in a daily newspaper to develop storytelling skills; Possible benefits. | Editor & Publisher. 2/5/94, Vol. 127 Issue 6, p5. 1p. | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Slow down and Find the Story Worth Telling. The article presents information on how to write narrative journalism, referred to as literary journalism and defined as creative nonfiction that contains accurate, well-researched information. It mentions that making narrative will allow the journalist to break the informaton or subject matter into smaller pieces. | Quill. Sep/Oct2016, Vol. 104 Issue 5, p9-18. 2p. | Academic Search Premier (Library Database)

- Use the 5 "R's": How to Write Creative Nonfiction: Use Modern Nonfiction Narratives Use Techniques from Fiction to Create Unforgettable Writing by Catherine Gourley "The first step in writing a creative nonfiction story is to focus on a real person or event. Whatever the subject, your goal should be to discover and communicate something new." | Writing!, vol. 26, no. 1, Sept. 2003. | Gale Power Search (Library Database)

- Structure and Narrative All narratives contain events that happened - or, in fiction, are supposed to have happened - which authors shape into the form then encountered by readers. The first of these areas, the set of events to be communicated, is often referred to simply as ‘story’. The second, the communication itself, is usually referred to as ‘text’ or ‘narrative text’. | The Edinburgh Introduction to Studying English Literature | Credo Reference (Library Database)

- Structure by John McPhee In this article the author, a nonfiction writer, comments on the role played by structure in the composition of factual writing pieces. He discusses his use of structure in authoring articles for the magazines "Time" and "The New Yorker," explores the role of chronology and time in narrative nonfiction writing. | McPhee, John, New Yorker. 1/14/2013, Vol. 88 Issue 43, p46-55. 10p | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Series for Effects by Jack Hart Comments on the importance of coordinating grammatical structure in sentences for superior writing. | Editor & Publisher. 02/07/98, Vol. 131 Issue 6, p4. 1/2p. | Academic Search Premier (Library Database)

- Music in the Words by Jack Hart Considers the characteristics of rhythm added to written works. Power of the rhythm honored by newspaper journalists; Balance; Alliteration; Varied structures; Hearing the beat. | Editor & Publisher. 01/31/98, Vol. 131 Issue 5, p6. 1p. | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- How to organize a nonfiction feature: Structure in the road map to successful storytelling. by Mark Masse This article offers tips on how to organize a nonfiction article. The writer must first be able to state the focus, theme or premise of his story in one brief sentence. An advice on how to find the focus of a story is presented. The writer must also need to analyze his material through categorization. The article also advises writers to select the appropriate story structure. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Sep2006, Vol. 119 Issue 9, p26-28. 3p. | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

Point of View

- Choosing a Place to Stand by Jack Hart Focuses on three point-of-view questions in journalism. Geography; Voice; Character. | Editor & Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- In Defense of Lyric: Point of View The lyrical point of view in poetry prevents poems from becoming just talk and can allow the poet to steer readers through emotions that would not be their initial reaction. | The Southern Review(Vol. 29, Issue 2) | Gale Literature Resource Center (Library Database)

- Point of View in Narrative Point of view in narrative is a focal angle of seeing, hearing, smelling, and sensing the story's settings, characters, and events. Researchers within the fields of language, linguistics and literature, assert that there are three main types of narrator: first-person, second-person, and third-person. The current paper depicts the three types, highlighting each in terms of aim, use, and potential for narrative effectiveness. | Theory and Practice in Language Studies(Vol. 9, Issue 8) | Gale Literature Resource Center (Library Database)

Voice and Style

- Voice Lessons: How to Find the Right Voice for Your Creative Nonfiction. by Mimi Schwartz. This article discusses the right voice for creative nonfiction writing. Voice is the mix of words, rhythms and attitude in writing. In creative nonfiction writing, voice is important because the author and the narrator are the same. Some steps that writers keep in mind when searching for the right voice for a particular story are provided. INSET: Give your writing authenticity. Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Jun2006, Vol. 119 Issue 6, p28-31. 4p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- 10 Ways to Evoke Emotion in Prose: A Close Look Reveals the Stylistic devices at Work in Some Choice Samples of Nonfiction Writing. by Kathy Bricetti Looks at stylistic devices such as: pacing, setting, the senses, voice and tone, dialogue, interior monologue, metaphor, symbolism, character development as stylistic devices do writers use to move readers to tears, laughter or other powerful emotions. | The Writer, vol. 120, no. 9, Sept. 2007, | Gale Power Search (Library Database)

- Building Charcter by Jack Hart. Offers advice on writing stories with human interest. Author's opinion on the use of quotations; Determining the character of individuals; close-up detail that creates true character of an individual. | Editor & Publisher. 12/28/96, Vol. 129 Issue 52, p5. 1p | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Quoting for Character by Jack Hart. Urges journalists to use the original wording when including quotes from people who are featured in news stories. Distinctive language patterns as a prime source of revealed character; Bigger impact of a faithful rendition of the original; Examples of these quotes. Editor & Publisher. 8/10/96, Vol. 129 Issue 32, p1. | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- The Determination of Incident or What Is Character? PDF Link. The author presents the method he developed for talking to students about how to imagine and develop characters in a novel. Topics discussed include the complaint of writing students concerning their difficulty of developing a plot, tips on devising a single character, and the importance of desire for the development of narrative. | Sewanee Review, vol. 126, no. 4, Fall 2018, pp. 738–53. | MasterFILE Complete (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Choosing the Perfect Lead from Many Styles by Jack Hart Presents a lexicon of feature leads used on news stories. Anecdotal leads; Narrative leads; Scene-stealer leads; Scene-wraps or gallery leads; Significant detail leads; Single-instance lead; Word-play Leads. | Editor & Publisher. 09/26/98, Vol. 131 Issue 39, p41 | Academic Search Premier (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Keep It Fresh: How to Turn the Same Old Scene into Something New In order to avoid repetition in writing nonfiction, the author suggested to go deeper into the material, consider the negatives and flaws and being selective. Seeing anew in nonfiction is not a matter of imagination. It is a matter of being there, immersed in a place and event and character. Every scene in a nonfiction book needs to add something to what the reader already knows | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Aug2006, Vol. 119 Issue 8, p24-26. | MasterFILE Complete (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Keeping Pace by Jack Hart. Points out the importance of pace in a nonfiction narrative. William Howard Russell's mastery of narrative pacing in his eyewitness report on the Battle of Balaklava in 1854. | Editor & Publisher. 6/08/96, Vol. 129 Issue 23, p5. 2p. | Database: MasterFILE Complete.

- High Tension by Jack Hart Focuses on the use of the foreshadowing technique in journalism. Device for novels, short stories, television shows and movies; Mystery pronouns; Mystery nouns; Ominous detail; Highly specific narrative; Dramatic payoff expected by readers from a highly specific action sequence; Leads used in reporting. | Editor & Publisher. 2/11/95, Vol. 128 Issue 6, p3. 1p | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- Writing Clinic by Jack Hart Journalists sell information about action. And when they lose sight of that simple truth, they lose their audience. It follows that journalists should pay particular attention to verbs, the words created to capture action | The Quill, vol. 80, no. 1, Jan.-Feb. 1992, pp. 40+. | Database: Gale Academic OneFile.

- How to write effective dialogue in narrative nonfiction: A longtime editor and teacher shares tips for adapting a fiction tool to true storytelling—without upsetting journalism ethics. by Jack Hart. The article presents suggestions to authors of narrative nonfiction for writing dialogue that does not violate journalism ethics. A passage from the book "Travels in Georgia," by John McPhee is considered in terms of how dialogue is mixed with direct action. Ways that dialogue can be used to enhance an author's narrative are discussed. Other topics include conducting interviews with research subjects, the use of unspoken thoughts in literature, memory, and internal monologue. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Jun2011, Vol. 124 Issue 6, p28-29. 2p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO)

- Once Upon a Cliche by Jack Hart "The reviewer who begins his essay 'Once upon a time' does so not because the phrase captures his thought precisely but because his deadline is looming and he wants to go home." Exactly. A cliche is a quick out. A substitute for thinking." | Editor & Publisher. 9/2/95, Vol. 128 Issue 35, p5. 1p. | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- How to Write Effective Dialogue in Narrative Nonfiction The article presents suggestions to authors of narrative nonfiction for writing dialogue that does not violate journalism ethics. A passage from the book "Travels in Georgia," by John McPhee is considered in terms of how dialogue is mixed with direct action. Ways that dialogue can be used to enhance an author's narrative are discussed. Other topics include conducting interviews with research subjects, the use of unspoken thoughts in literature, memory, and internal monologue. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.), vol. 124, no. 6, June 2011, pp. 28–29. | Academic Search Premier (Library Database)

- Help! I Can't Find My Theme! by Steven Pressfield "Theme influences and determines everything in our story. Mood, setting, tone of voice, narrative device. Theme tells us what clothes to put on our leading lady, what furniture to put in our hero’s house, what type of gun our villain carries strapped to his ankle." (Author Website)

- Dealing with Danglers bu Jack Hart Focuses on the risks of committing mistakes when using dangling modifiers in newspaper reporting. Examples of mistakes related to the careless use of dangling modifiers; Guidelines in using such modifiers; Suggestion for newspapers to make their statements simple. | Editor & Publisher. 07/18/98, Vol. 131 Issue 29, p5. 1p | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- Painting Portraits with Words by Jack Hart Discusses the importance of text description in newspaper reporting. Argument by some reporters that text description is not necessary when stories appear with photographs of principals; Ability of text description to focus on distinctive aspects of appearance in ways that a photograph cannot. | Editor & Publisher. 8/12/95, Vol. 128 Issue 32, p5. 1p. | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- Missed Opportunities by Jack Hart Focuses on the obligations of newspapers in presenting news stories to the public. Linkage of readers to the rest of humanity; Recognition of ingredients of a good story; Tendency of newspapers to pass up opportunities for first-class storytelling. | Editor & Publisher. 7/8/95, Vol. 128 Issue 27, p5. 1p. | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- A Sense of Order by Jack Hart Stresses the need to present news information in logical order to avoid confusing the readers. Listing of questions most likely asked by readers; Importance of making assumptions about readers; Flexibility of mind to see the world the way it is seen by readers. Editor & Publisher. 6/11/94, Vol. 127 Issue 24, p3. 1p. | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

- In the Reader's Shoes by Jack Hart Emphasizes effective written communication in journalism. Clear writing as a matter of empathy; Basis of meaning in people; Overlapping of personal experiences with common words; Samples of ineffective reporting. | Editor & Publisher. 8/20/94, Vol. 127 Issue 34, p3. 1p | Database: Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

Jack Hart Writing

- Organize your writing: A veteran writing coach offers an antidote to false starts, wasted time and flat storytelling "A fiction writer or essayist may work with details gathered long before she actually puts hands to keyboard. But gathering those details is still reporting, and many a fiction writer draws on specifics recorded in a journal or a daybook at the time they were experienced." | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). May2007, Vol. 120 Issue 5, p41-43. 3p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- How to write effective dialogue in narrative nonfiction: A longtime editor and teacher shares tips for adapting a fiction tool to true storytelling—without upsetting journalism ethics. by Jack Hart. The article presents suggestions to authors of narrative nonfiction for writing dialogue that does not violate journalism ethics. A passage from the book "Travels in Georgia," by John McPhee is considered in terms of how dialogue is mixed with direct action. Ways that dialogue can be used to enhance an author's narrative are discussed. Other topics include conducting interviews with research subjects, the use of unspoken thoughts in literature, memory, and internal monologue. | Writer (Kalmbach Publishing Co.). Jun2011, Vol. 124 Issue 6, p28-29. 2p. | Literary Reference Center Plus (EBSCO) (Library Database)

- Keeping Pace by Jack Hart. Points out the importance of pace in a nonfiction narrative. William Howard Russell's mastery of narrative pacing in his eyewitness report on the Battle of Balaklava in 1854. | Editor & Publisher. 6/08/96, Vol. 129 Issue 23, p5. 2p. | MasterFILE Complete (Library Database)

JacK Hart Bio

- Jack Hart "Jack Hart has drawn on his experience as a reporter and editor to compose advice books about his profession. Explaining his philosophy of writing in a Writers on the Rise Web site interview with Susan W. Clark, Hart commented: "I've learned that your writing process is the most important, and if you want to change the way you write, you need to change that process. Then constantly expand your craft and you'll write well." | From: Gale Literature: Contemporary Authors | Gale Literature Resources Center (Library Database)

- Storycraft: The Complete Guide to Writing Narrative Nonfiction, 2ed. Amazon Link | Paperback $13.71, 286 pages

- << Previous: About Creative Nonfiction

- Next: Author List >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://westerntc.libguides.com/creativenonfiction

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

Creative nonfiction—you’ve probably heard the term before, but what exactly does it mean? At first glance, the term may seem almost oxymoronic. If it’s nonfiction, where does the creative come in? you might ask yourself. Isn’t creativity about making things up?

In fact, creative nonfiction involves plenty of creativity, just as much as fiction or poetry. As Lee Gutkind, editor of the journal Creative Nonfiction, says, creative nonfiction is, plainly, “true stories, well told.”

It’s that well told part that it’s imperative. Creative nonfiction writers use the same techniques as playwrights or novelists. They may write memoirs, personal essays, long-form journalism; they may write travelogues or biographies or very brief essays called flash nonfiction. What’s common across these forms of creative nonfiction is the reliance on scene. Scene, many argue, is what separates creative nonfiction from informational nonfiction.

And scenes contain other literary elements. Scenes are set in a time and a place, and a good writer sketches out those details for their reader. Scenes contain characters, people the writer describes with precision and clarity. Most importantly, scenes contain conflict. And that’s one more distinction between creative nonfiction and informational nonfiction. There’s a problem or crisis or conflict at the heart of creative nonfiction and, like in a story or a novel or a play, the protagonist is trying to see some part of that problem resolved. All that’s different is the premise: when you read creative nonfiction, you always remember, “this really happened.”

What is Creative Nonfiction?

There are many ways to define the literary genre we call Creative Nonfiction. It is a genre that answers to many different names, depending on how it is packaged and who is doing the defining. Some of these names are: Literary Nonfiction; Narrative Nonfiction; Literary Journalism; Imaginative Nonfiction; Lyric Essay; Personal Essay; Personal Narrative; and Literary Memoir. Creative Nonfiction is even, sometimes, thought of as another way of writing fiction, because of the way writing changes the way we know a subject.

I like to define the genre in as broad a way as possible. I describe it as memory-or-fact-based writing that makes use of the styles and elements of fiction, poetry, memoir, and essay. It is writing about and from a world that includes the author’s life and/or the author’s eye on the lives of others.

Under the umbrella called Creative Nonfiction we might find a long list of sub-genres such as: memoir, personal essay, meditations on ideas, literary journalism, nature writing, city writing, travel writing, journals or letters, cultural commentary, hybrid forms, and even, sometimes, autobiographical fiction.

Creative nonfiction writing can embody both personal and public history. It is a form that utilizes memory, experience, observation, opinion, and all kinds of research. Sometimes the form can do all of the above at the same time. Other times it is more selective.

What links all these forms is that the “I,” the literary version of the author, is either explicitly or implicitly present—the author is in the work. This is work that includes the particular sensibility of the author while it is also some sort of report from the world. Be it a public or a personal world. Be the style straightforward like a newspaper feature, narrative like a novel, or metaphorical like a poem.

One of my favorite words to attach to the art of creative nonfiction writing is the word “actual.” I prefer the word actual to the word truth. Fiction writers insist that they too write the truth, and that they must invent in order to tell this truth. I prefer the word actual to the word fact. Facts alone are too dry, and too absent of association. I prefer the word actual to the word real. What is and is not real is continually up for grabs. Do we know, for instance, what is a real woman? A real man? The word real is too laden with assumption. I prefer the word actual because it refers to simple actuality. We begin a work of creative nonfiction not with the imaginary but with the actual, with what actually is or actually was, or what actually happened. From this point we might move in any direction, but the actual is our touchstone.

Different writers have said very different things about why they write in this form. Lee Gutkind, the editor of the magazine Creative Nonfiction, has described the form as a quest for understanding and information. The cultural critic bell hooks has said she wrote her memoir Bone Black in order to “recover the past.” Essayist, memoirist, and diva of nonfiction prose style Annie Dillard has said she writes to “fashion a text.” Dorothy Allison has used the stories of her life in both fiction and nonfiction in order, she’s written, “to save my life.”

The various roots of this form are quite widespread. The practice of narrative and social witness reportage can be traced all the way back to Daniel Defoe’s (fictional) Journal of a Plague Year as well as to 18th century “disaster journalism.” In the 1960’s the New Journalists revolutionized modern journalistic form by insisting on inserting the first person into their reportage. These writers, such as Tom Wolfe and Joan Didion, were interested in bringing the presence of an individual awareness to the work, acknowledging that the writer is incapable of complete subjectivity and is constantly interpreting what he or she observes. From this tradition we inherit countless models of the ways to translate interviews and research into a style that resembles the storytelling and dramatic movement of fiction and the language and rhythms of poetry.

The personal essay form is much older. It dates back, according to some, to 16th century French writer Montaigne and to the French root of the word “essay,” which means to “attempt” or “try.” Others suggest we might date the essay form back even further, and include such works as The Pillow Book of Sei Shonogan,the eloquent musings of a 10th century Japanese lady of the court. The personal essay reflects the mind at odds with itself, and some of the most beautiful personal essays ask questions they cannot hope to answer. It’s the meander through ideas and stories that make the work wonderful to read.

We can look, also, to St. Augustine’s Confessions, written in the 5th century, as a model for writing out of our own life and experience. Sometimes referred to as “the first memoir” St. Augustine’s story is one of conversion and rebirth, not unlike today’s familiar recovery-from-addiction narrative. Personal memoir is a form that has slowly evolved into the sort of the book commonly found on the contemporary bookstore new release table. At one time the actual memoirist was considered insignificant to the memoir. When a soldier described the battle, for instance, it was the battle that mattered, not the soldier. Public events were considered historical, while private life was seen as inappropriate to the written word, unless you were a person considered of singular historical importance—Winston Churchill, or a Kennedy, for instance. All this has changed in our postmodern day-to-day. Feminism has privileged the personal, changing the paradigms of what is worthy of cultural notice and recovering the stories of lives previously absent from history. Identity and cultural politics redirected attention to people of color, gays and lesbians, the disabled, and anyone else who was up to that point missing from the public record. The mainstreaming of psychoanalysis and related disciplines suggested that our conscious and unconscious motivations and feelings are no longer considered strictly private matters.

A negative interpretation of these cultural changes suggests we are interested in the private story and the personal vantage point only because we are held hostage by talk show and “reality TV” culture. While it is true that it’s often difficult to fully comprehend how commercial culture has influenced our tastes and cravings, I believe that these phenomena are coupled with what has become a healthy intellectual and emotional curiosity about the world as it actually exists. We want to know what really happened. What distinguishes quality literary endeavor from media manipulation has as much to do with intention and artistry as it does public confession. Beyond the hype and exploitation of the worst of the commercial personal forms, what I continue to value is one person’s story—the world as seen through the scrim of each of our personal experiences. For better or worse, we are more aware than we once were of the role the personal plays in everything we do. These changes in literary nonfiction grow out of parallel changes in our world.

The report, the critique, the rumination, the lyric impression and the hard fact are all found in contemporary creative nonfiction writing. It is the mix of all these elements that make creative nonfiction an illuminating and moving form of historical documentary, as well as lovely literature. Finally, I’m with Annie Dillard when I say creative nonfiction writing is first about the formation of a text, the creation of piece of art, just like any painting or musical composition. Your life and the life of the world is your raw material, as much a part of the mix as is the paint, the chords, the words. Your subjects might be any part of this world.

Accounting for the fluid lines of tradition streaming into the creative nonfiction of today can be overwhelming, but also freeing. We creative nonfiction writers can make form out of whatever containers we are capable of imagining, and still be working within the wide parameters of the actual. Let’s end with some famous words on the subject of creating creative nonfiction literature. This is a quote from Annie Dillard, from her famous essay “To Fashion a Text.”

“When I gave up writing poetry I was very sad, for I had devoted 15 years to the study of how the structures of poems carry meaning. But I was delighted to find that nonfiction prose can also carry meaning in its structures, can tolerate all sorts of figurative language, as well as alliteration and even rhyme. The range of rhythms in prose is larger and grander than it is in poetry, and it can handle discursive ideas and plain information as well as character and story. It can do everything. I felt as though I had switched from a single reed instrument to a full orchestra.”

“What is Creative Nonfiction?” by Barrie Jean Borich. Licensed under CC BY SA 4.0 http://barriejeanborich.com/what-is-creative-nonfiction-an-introduction/

Creative nonfiction has been growing in popularity for years. After the rise of new journalism and the memoir boom of the 1990s, we find ourselves in a literary landscape teeming with creative nonfiction. Now, whenever you go to a bookstore, you’re bound to find a creative nonfiction section sure to rival the fiction section (and sure to trump the poetry section!). Memoirs, essay collections, biographies—these are examples of creative nonfiction, and as often as anything else, they become best sellers.

What makes creative nonfiction so compelling? Perhaps it’s as simple as Gutkind’s definition of the genre: “true stories, well told.” As readers, we care about being told a good story. We want to enter the realm of make-believe, if we know that the make-believe we’re reading about isn’t make-believe at all! By using literary elements like scene, which inherently necessitate things like character, plot, conflict, and setting, creative nonfiction writers weave compelling tales. These tales contain drama and action, peril and intrigue, and they become all the more powerful when you, as a reader, consider that the events described or explored may have happened to someone just like you.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Creative Nonfiction in Writing Courses

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Introduction

Creative nonfiction is a broad term and encompasses many different forms of writing. This resource focuses on the three basic forms of creative nonfiction: the personal essay, the memoir essay, and the literary journalism essay. A short section on the lyric essay is also discussed.

The Personal Essay

The personal essay is commonly taught in first-year composition courses because students find it relatively easy to pick a topic that interests them, and to follow their associative train of thoughts, with the freedom to digress and circle back.

The point to having students write personal essays is to help them become better writers, since part of becoming a better writer is the ability to express personal experiences, thoughts and opinions. Since academic writing may not allow for personal experiences and opinions, writing the personal essay is a good way to allow students further practice in writing.

The goal of the personal essay is to convey personal experiences in a convincing way to the reader, and in this way is related to rhetoric and composition, which is also persuasive. A good way to explain a personal essay assignment to a more goal-oriented student is simply to ask them to try to persuade the reader about the significance of a particular event.

Most high-school and first-year college students have plenty of experiences to draw from, and they are convinced about the importance of certain events over others in their lives. Often, students find their strongest conviction in the process of writing, and the personal essay is a good way to get students to start exploring these possibilities in writing.

A personal essay assignment can work well as a prelude to a research paper, because personal essays will help students understand their own convictions better, and will help prepare them to choose research topics that interest them.

An Example and Discussion of a Personal Essay

The following excerpt from Wole Soyinka's (Nigerian Nobel Laureate) Why Do I Fast? is an example of a personal essay. What follows is a short discussion of Soyinka's essay.

Soyinka begins with a question that fascinates him. He doesn’t feel required to immediately answer the question in the second paragraph. Rather, he takes time to consider his own inclination to believe that there is a connection between fasting and sensuality.

Soyinka follows the flowing associative arc of his thoughts, and he goes on to write about sunsets, and quotes from a poem that he wrote in his cell. The essay ends, not on a restatement of his thesis, but on yet another question that arises:

This question remains unanswered. Soyinka is not interested in even attempting to answer it. The personal essay doesn’t necessarily seek to make sense out of life experiences; rather, personal essays tend to let go of that sense-making impulse to do something else, like nose around a bit in the wondering, uncertain space that lies between experience and the need to organize it in a logical manner.

However informal the personal essay may seem, it’s important to keep in mind that, as Dinty W. Moore says in The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , “the essay should always be motivated by the author’s genuine interest in wrestling with complex questions.”

Generating Ideas for Personal Essays

In The Truth of the Matter: Art and Craft in Creative Nonfiction , Moore goes on to explain an effective way to help students generate ideas for personal essays:

“Think about ten things you care about deeply: the environment, children in poverty, Alzheimer’s research (because your grandfather is a victim), hip-hop music, Saturday afternoon football games. Make your own list of ten important subjects, and then narrow the larger subject down to specific subjects you might write about. The environment? How about that bird sanctuary out on Township Line Road that might be torn down to make room for a megastore?..."

"...What is it like to be the food service worker who puts mustard on two thousand hot dogs every Saturday afternoon? Don’t just wonder about it - talk to the mustard spreader, spend an afternoon hanging out behind the counter, spread some mustard yourself. Transform your list of ten things into a longer list of possible story ideas. Don’t worry for now about whether these ideas would take a great amount of research, or might require special permission or access. Just write down a master list of possible stories related to your ideas and passions. Keep the list. You may use it later.”