How to Write a Winning Workshop Proposal

Feeling behind on ai.

You're not alone. The Neuron is a daily AI newsletter that tracks the latest AI trends and tools you need to know. Join 400,000+ professionals from top companies like Microsoft, Apple, Salesforce and more. 100% FREE.

Do you have a passion for sharing your knowledge and expertise with others? Are you interested in facilitating a workshop? A workshop proposal is your key to showcasing your skills and talents and securing a slot in a conference or event. In this in-depth guide, we'll share some tips for crafting a winning workshop proposal that will impress event organizers and help you land your dream gig.

Understanding the Purpose of a Workshop Proposal

Before diving into the nitty-gritty of creating a workshop proposal, it's important to understand its purpose. A workshop proposal is a document outlining your proposed workshop topic, structure, and objectives. It's an essential tool for communicating your ideas and persuading organizers to select your workshop over the competition.

Workshops are a popular way to share knowledge and skills with a group of people who are interested in a particular topic. They can be used for a variety of purposes, such as professional development, team building, or personal growth. A well-crafted workshop proposal can help you stand out from the crowd and increase your chances of being selected to present at a conference or event.

Identifying Your Target Audience

The first step in creating a successful workshop proposal is identifying your target audience. Think about who might be interested in your workshop and what their needs are. Understanding your audience's interests and motivations will help you select a topic that is relevant and engaging.

Consider the demographics of your audience, such as their age, gender, and profession. What are their pain points and challenges? What do they hope to gain from attending your workshop? Answering these questions will help you tailor your content to meet their needs and ensure that your workshop is a success.

Establishing Clear Workshop Goals

Once you've identified your target audience, you'll want to establish clear workshop goals. What do you want participants to take away from your workshop? What skills or knowledge do you hope to impart? Developing clear and measurable objectives will help you structure your workshop and demonstrate its value.

Consider the level of expertise of your audience. Are they beginners or experts in the topic you're presenting? What are the key takeaways you want them to remember? By establishing these goals, you can create a workshop that is effective and memorable.

Creating an Engaging Workshop Structure

In addition to identifying your target audience and establishing clear workshop goals, you'll want to create an engaging workshop structure. This includes selecting the appropriate format, such as a lecture, hands-on activity, or group discussion. You'll also want to consider the length of your workshop and how to keep participants engaged throughout.

Consider incorporating interactive elements, such as games, quizzes, or role-playing activities. This will help participants retain the information presented and make the workshop more fun and engaging. You may also want to consider providing handouts or resources for participants to take home and reference after the workshop is over.

In conclusion, creating a successful workshop proposal requires a thoughtful approach. By identifying your target audience, establishing clear workshop goals, and creating an engaging workshop structure, you can create a workshop that is both informative and enjoyable for participants. Remember to keep your audience's needs in mind and tailor your content to meet their interests and motivations. With these tips in mind, you'll be well on your way to creating a workshop proposal that stands out from the competition.

Researching and Selecting the Right Workshop Topic

Choosing the right workshop topic is crucial to the success of your proposal. Here are some steps you can take to ensure your topic is both unique and appealing.

Analyzing Current Industry Trends

Start by analyzing current industry trends and identifying topics that are relevant and timely. This will help you craft a workshop that is fresh and exciting.

Assessing the Needs of Your Audience

Next, assess the needs of your audience. What are they struggling with? What challenges are they facing? Identifying these pain points can help you tailor your workshop to their specific needs.

Choosing a Unique and Engaging Topic

Finally, choose a unique and engaging workshop topic that sets you apart from the competition. Look for opportunities to present your expertise in a creative and innovative way.

Crafting a Compelling Workshop Title and Description

Once you've identified your workshop topic, it's time to craft a title and description that will capture the attention of event organizers and potential participants.

Writing an Attention-Grabbing Title

Your title should be concise, catchy, and informative. Focus on highlighting the main benefit of your workshop and making it clear why it's worth attending.

Providing a Clear and Concise Description

In your workshop description, provide a clear and concise summary of what participants can expect to learn. Use persuasive language to convey the value of your workshop and convince organizers that it's worth including in their event.

Highlighting the Benefits and Outcomes for Participants

Don't forget to highlight the benefits and outcomes for participants. Make it clear how your workshop will help them achieve their goals and stand out in their field.

Developing an Effective Workshop Outline

Now that you have a solid workshop topic and proposal, it's time to start developing your workshop outline. A clear and detailed outline will help you structure your workshop and ensure that it runs smoothly.

Breaking Down Your Workshop into Manageable Sections

Break down your workshop into manageable sections and organize them in a way that makes sense. Consider the length of the workshop and the attention span of your participants when structuring your outline.

Incorporating Interactive Activities and Discussions

Incorporate interactive activities and discussions into your workshop to keep participants engaged and facilitate learning. This can include group work, brainstorming sessions, and hands-on projects.

Ensuring a Logical Flow and Smooth Transitions

Finally, ensure that your workshop has a logical flow and smooth transitions between sections. This will help participants keep track of where they are and what they're learning, and keep them engaged throughout the session.

Now that you have a solid workshop proposal, it's time to start submitting it to event organizers. Keep in mind that the competition for workshop slots can be fierce, so be prepared to revise and refine your proposal as needed. With persistence and a solid proposal, you'll be on your way to landing your dream workshop gig in no time!

ChatGPT Prompt for Writing a Workshop Proposal

Use the following prompt in an AI chatbot . Below each prompt, be sure to provide additional details about your situation. These could be scratch notes, what you'd like to say or anything else that guides the AI model to write a certain way.

Please compose a comprehensive and detailed proposal for a workshop that you would like to conduct. Your proposal should include a clear explanation of the objectives and goals of the workshop, the intended audience, the methodology you plan to use, and the expected outcomes. Please provide a detailed schedule of activities and resources required for the workshop, as well as a description of your qualifications and experience as a workshop facilitator. Your proposal should be well-organized, clear, and persuasive, with a focus on the relevance and value of the workshop for the intended audience.

[ADD ADDITIONAL CONTEXT. CAN USE BULLET POINTS.]

You Might Also Like...

Proposal Template AI

Free proposal templates in word, powerpoint, pdf and more

Workshop Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide + Free Template Download + How to Write it

The importance of workshop proposal templates.

As a workshop facilitator, I understand the importance of presenting a clear and well-structured proposal to potential clients. A workshop proposal template is a crucial tool in streamlining the process of creating and presenting proposals for workshops. It provides a framework for organizing key information, setting clear objectives , and outlining the value and benefits of the proposed workshop. Unlike a standard proposal, a workshop proposal template is specifically tailored to the unique requirements and considerations of planning and delivering a workshop. In this article, we will explore the significance of workshop proposal templates and how they can enhance the professional presentation of workshop proposals.

Workshop Title:

Introduction:.

The introduction should provide a brief overview of the workshop topic and its importance. It should also include the objectives and goals of the workshop, and how it will benefit the participants.

Example: The workshop will be titled “ Effective Communication in the Workplace” and will focus on improving communication skills , reducing conflicts, and enhancing teamwork in the workplace. The goal is to provide participants with practical tools and techniques to improve their communication skills and create a more harmonious work environment .

Workshop Details:

This section should include the duration of the workshop, the target audience , and the expected number of participants. It should also mention any prerequisites or requirements for the participants.

Example: The workshop will be a full-day session, from 9 am to 5 pm, and will be open to all employees across different departments. We expect to have around 30 participants who are eager to enhance their communication skills. No prerequisites are required, as the workshop will cater to participants at all skill levels.

Workshop Agenda:

Provide a detailed outline of the workshop agenda , including the topics to be covered, the activities planned, and the time allocated for each segment.

Example: – 9:00 am – 9:30 am: Introduction and Icebreaker Activity – 9:30 am – 11:00 am: Understanding Communication Styles – 11:00 am – 12:30 pm: Active Listening and Feedback Techniques – 12:30 pm – 1:30 pm: Lunch Break – 1:30 pm – 3:00 pm: Conflict Resolution Strategies – 3:00 pm – 4:30 pm: Group Exercises and Role-Playing Scenarios – 4:30 pm – 5:00 pm: Q&A and Workshop Conclusion

Workshop Deliverables:

In this section, outline the expected outcomes and deliverables of the workshop, including any materials or resources that will be provided to the participants.

Example: Participants will gain a deeper understanding of different communication styles and techniques, as well as practical skills for conflict resolution and active listening. They will also receive a workshop manual with reference materials and exercises to continue practicing their communication skills after the workshop.

Speaker Bio:

Provide a brief biography of the workshop facilitator or speaker, highlighting their expertise and experience in the relevant field.

Example: Our workshop facilitator, John Smith, is a certified communication coach with over 10 years of experience in conducting communication workshops for various organizations. He specializes in interpersonal communication and conflict resolution, and has received positive feedback from previous workshop participants.

Cost and Logistics:

This section should include the cost of the workshop, any logistical details such as venue, equipment, and catering arrangements, as well as any special requirements for the workshop.

Example: The cost of the workshop will be $200 per participant, which includes all workshop materials, refreshments, and lunch. The workshop will be held at our company’s training center , and all necessary equipment, such as projectors and whiteboards, will be provided. Participants are advised to bring their own notebooks and pens for taking notes during the workshop.

My advice on using these examples is to customize them according to the specific needs and objectives of your proposed workshop. Make sure to clearly outline the benefits and outcomes of the workshop for the participants and the organization. Providing a detailed agenda and deliverables will help in setting clear expectations for the workshop. Additionally, highlighting the expertise of the facilitator or speaker will add credibility to the proposal. Lastly, be transparent about the cost and logistical details to avoid any confusion or misunderstandings.

Download free Workshop Proposal Template in Word DocX, Powerpoint PPTX, and PDF. We included Workshop Proposal Template examples as well.

Download Free Workshop Proposal Template PDF and Examples Download Free Workshop Proposal Template Word Document

Download Free Workshop Proposal Template Powerpoint

FAQ for Workshop Proposal Template

Q: What is a workshop proposal template? A: A workshop proposal template is a document that outlines the objectives, content, and logistics of a proposed workshop.

Q: Why do I need a workshop proposal template? A: A workshop proposal template helps organize and communicate the details of a proposed workshop to stakeholders, sponsors, or decision-makers.

Q: What should be included in a workshop proposal template? A: A workshop proposal template should include the workshop title, objectives, target audience , schedule, outline of topics to be covered, proposed speakers or facilitators, logistical requirements, and anticipated outcomes .

Q: Can I customize the workshop proposal template to fit my specific workshop? A: Yes, the workshop proposal template is meant to be customizable. You can modify it to fit the specific goals and requirements of your proposed workshop.

Q: How can I use the workshop proposal template to secure funding or approval for my workshop? A: By filling out the workshop proposal template with detailed and compelling information about your workshop, you can use it as a tool to present a clear and persuasive case for funding or approval.

Q: Where can I find a workshop proposal template to use? A: You can find workshop proposal templates online through various template websites or by searching for specific templates related to your industry or topic.

Q: Can I share the workshop proposal template with others on my team for collaboration? A: Yes, the workshop proposal template can be shared with others on your team for collaboration and input to ensure that all relevant details are included.

Related Posts:

- Music Business Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Training Workshop Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- It And Software Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Business Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide +…

- Corporate Event Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Fundraising Proposal Template: A Comprehensive Guide…

- Website Design Proposal Template: A Comprehensive…

- Event Planning Request For Proposal Template: A…

How to Write a Workshop Proposal

by Erika Sanders

Published on 26 Sep 2017

A successful workshop proposal is both concise and comprehensive. A standard proposal will have several key elements. These include the workshop title, summary, syllabus and objectives, as well as your relevant biography information. The first key to having your proposal accepted is to follow all required guidelines. The second key is to present a unique and clearly defined workshop.

Obtain the official submission guidelines from the institution or program to which you want to submit a workshop proposal. If you are not familiar with the program, take the necessary time to research its website, including other workshops being offered, credentials of its current instructors and its mission statement. Make certain before submitting your proposal that you and your course would be a good match for the program.

Create a workshop title that is both eye-catching and specific. You want potential students to know from your title what your course is about. If it is not eye-catching, potential students might bypass it for a workshop that sounds more interesting.

Prepare a workshop summary. Clearly explain the topic of your workshop and its relevance to the program and students in a short paragraph. In proposals, brevity is important, as reviewers do not have time to read pages and pages of explanation about why your workshop would be great. At the same time, your summary is your introduction to both you and your workshop. Make each sentence count by focusing on the primary objective of the course.

Create a course syllabus. If your workshop is only one day, prepare an hour-by-hour syllabus. If your workshop will take place over several weeks, outline the objective you'll meet each week and the assignments you'll give.

List the specific course objectives, the skills the students will have learned by the end of the course. Again, objectives should be specific. Using a short story workshop as an example, a good course objective would be that by the end of the course, students will know how to create complex characters with clear motivations, goals and personality traits. Merely stating that students will be able to write better short stories is too vague.

Create or update your resume or curriculum vitae. The CV you submit with your proposal should highlight the experience and skills you have that specifically relate to the course you want to teach and the program where you want to teach. Check the program's submission guidelines once more to be certain you meet all their requirements for instructors.

Compile all of these elements into one document. The title and workshop summary should come first, followed by the syllabus, course objectives and your bio. Attach your CV to your proposal. Be certain that all your contact information is on both the proposal and your CV.

Submit your proposal by email or the postal service, depending on the submission guidelines. Submitting the proposal by the wrong method might result in it not being considered.

- Privacy Policy

Home » How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

How To Write A Proposal – Step By Step Guide [With Template]

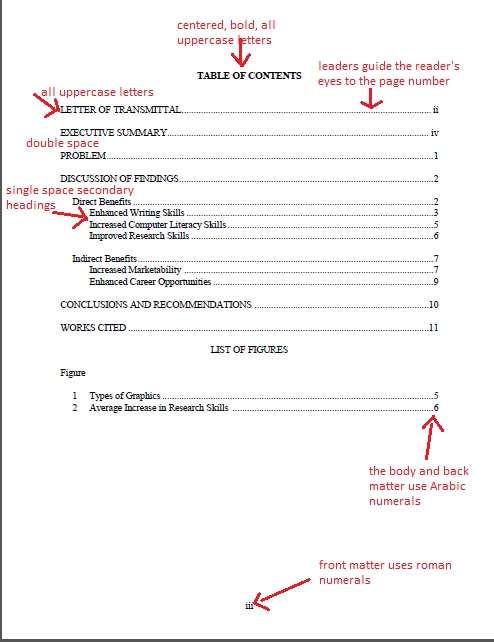

Table of Contents

How To Write A Proposal

Writing a Proposal involves several key steps to effectively communicate your ideas and intentions to a target audience. Here’s a detailed breakdown of each step:

Identify the Purpose and Audience

- Clearly define the purpose of your proposal: What problem are you addressing, what solution are you proposing, or what goal are you aiming to achieve?

- Identify your target audience: Who will be reading your proposal? Consider their background, interests, and any specific requirements they may have.

Conduct Research

- Gather relevant information: Conduct thorough research to support your proposal. This may involve studying existing literature, analyzing data, or conducting surveys/interviews to gather necessary facts and evidence.

- Understand the context: Familiarize yourself with the current situation or problem you’re addressing. Identify any relevant trends, challenges, or opportunities that may impact your proposal.

Develop an Outline

- Create a clear and logical structure: Divide your proposal into sections or headings that will guide your readers through the content.

- Introduction: Provide a concise overview of the problem, its significance, and the proposed solution.

- Background/Context: Offer relevant background information and context to help the readers understand the situation.

- Objectives/Goals: Clearly state the objectives or goals of your proposal.

- Methodology/Approach: Describe the approach or methodology you will use to address the problem.

- Timeline/Schedule: Present a detailed timeline or schedule outlining the key milestones or activities.

- Budget/Resources: Specify the financial and other resources required to implement your proposal.

- Evaluation/Success Metrics: Explain how you will measure the success or effectiveness of your proposal.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main points and restate the benefits of your proposal.

Write the Proposal

- Grab attention: Start with a compelling opening statement or a brief story that hooks the reader.

- Clearly state the problem: Clearly define the problem or issue you are addressing and explain its significance.

- Present your proposal: Introduce your proposed solution, project, or idea and explain why it is the best approach.

- State the objectives/goals: Clearly articulate the specific objectives or goals your proposal aims to achieve.

- Provide supporting information: Present evidence, data, or examples to support your claims and justify your proposal.

- Explain the methodology: Describe in detail the approach, methods, or strategies you will use to implement your proposal.

- Address potential concerns: Anticipate and address any potential objections or challenges the readers may have and provide counterarguments or mitigation strategies.

- Recap the main points: Summarize the key points you’ve discussed in the proposal.

- Reinforce the benefits: Emphasize the positive outcomes, benefits, or impact your proposal will have.

- Call to action: Clearly state what action you want the readers to take, such as approving the proposal, providing funding, or collaborating with you.

Review and Revise

- Proofread for clarity and coherence: Check for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.

- Ensure a logical flow: Read through your proposal to ensure the ideas are presented in a logical order and are easy to follow.

- Revise and refine: Fine-tune your proposal to make it concise, persuasive, and compelling.

Add Supplementary Materials

- Attach relevant documents: Include any supporting materials that strengthen your proposal, such as research findings, charts, graphs, or testimonials.

- Appendices: Add any additional information that might be useful but not essential to the main body of the proposal.

Formatting and Presentation

- Follow the guidelines: Adhere to any specific formatting guidelines provided by the organization or institution to which you are submitting the proposal.

- Use a professional tone and language: Ensure that your proposal is written in a clear, concise, and professional manner.

- Use headings and subheadings: Organize your proposal with clear headings and subheadings to improve readability.

- Pay attention to design: Use appropriate fonts, font sizes, and formatting styles to make your proposal visually appealing.

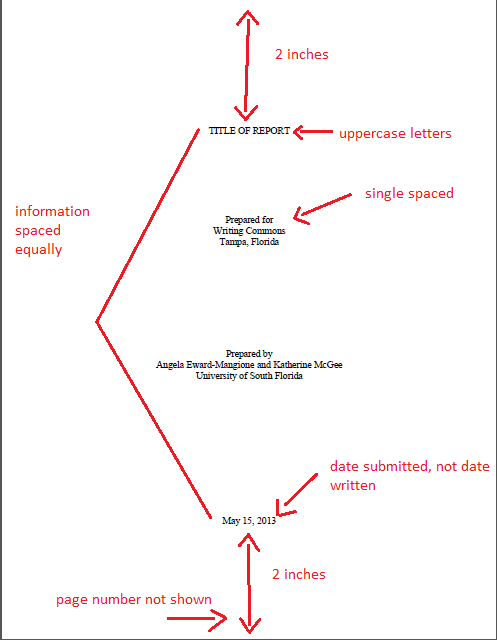

- Include a cover page: Create a cover page that includes the title of your proposal, your name or organization, the date, and any other required information.

Seek Feedback

- Share your proposal with trusted colleagues or mentors and ask for their feedback. Consider their suggestions for improvement and incorporate them into your proposal if necessary.

Finalize and Submit

- Make any final revisions based on the feedback received.

- Ensure that all required sections, attachments, and documentation are included.

- Double-check for any formatting, grammar, or spelling errors.

- Submit your proposal within the designated deadline and according to the submission guidelines provided.

Proposal Format

The format of a proposal can vary depending on the specific requirements of the organization or institution you are submitting it to. However, here is a general proposal format that you can follow:

1. Title Page:

- Include the title of your proposal, your name or organization’s name, the date, and any other relevant information specified by the guidelines.

2. Executive Summary:

- Provide a concise overview of your proposal, highlighting the key points and objectives.

- Summarize the problem, proposed solution, and anticipated benefits.

- Keep it brief and engaging, as this section is often read first and should capture the reader’s attention.

3. Introduction:

- State the problem or issue you are addressing and its significance.

- Provide background information to help the reader understand the context and importance of the problem.

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of your proposal.

4. Problem Statement:

- Describe the problem in detail, highlighting its impact and consequences.

- Use data, statistics, or examples to support your claims and demonstrate the need for a solution.

5. Proposed Solution or Project Description:

- Explain your proposed solution or project in a clear and detailed manner.

- Describe how your solution addresses the problem and why it is the most effective approach.

- Include information on the methods, strategies, or activities you will undertake to implement your solution.

- Highlight any unique features, innovations, or advantages of your proposal.

6. Methodology:

- Provide a step-by-step explanation of the methodology or approach you will use to implement your proposal.

- Include a timeline or schedule that outlines the key milestones, tasks, and deliverables.

- Clearly describe the resources, personnel, or expertise required for each phase of the project.

7. Evaluation and Success Metrics:

- Explain how you will measure the success or effectiveness of your proposal.

- Identify specific metrics, indicators, or evaluation methods that will be used.

- Describe how you will track progress, gather feedback, and make adjustments as needed.

- Present a detailed budget that outlines the financial resources required for your proposal.

- Include all relevant costs, such as personnel, materials, equipment, and any other expenses.

- Provide a justification for each item in the budget.

9. Conclusion:

- Summarize the main points of your proposal.

- Reiterate the benefits and positive outcomes of implementing your proposal.

- Emphasize the value and impact it will have on the organization or community.

10. Appendices:

- Include any additional supporting materials, such as research findings, charts, graphs, or testimonials.

- Attach any relevant documents that provide further information but are not essential to the main body of the proposal.

Proposal Template

Here’s a basic proposal template that you can use as a starting point for creating your own proposal:

Dear [Recipient’s Name],

I am writing to submit a proposal for [briefly state the purpose of the proposal and its significance]. This proposal outlines a comprehensive solution to address [describe the problem or issue] and presents an actionable plan to achieve the desired objectives.

Thank you for considering this proposal. I believe that implementing this solution will significantly contribute to [organization’s or community’s goals]. I am available to discuss the proposal in more detail at your convenience. Please feel free to contact me at [your email address or phone number].

Yours sincerely,

Note: This template is a starting point and should be customized to meet the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the organization or institution to which you are submitting the proposal.

Proposal Sample

Here’s a sample proposal to give you an idea of how it could be structured and written:

Subject : Proposal for Implementation of Environmental Education Program

I am pleased to submit this proposal for your consideration, outlining a comprehensive plan for the implementation of an Environmental Education Program. This program aims to address the critical need for environmental awareness and education among the community, with the objective of fostering a sense of responsibility and sustainability.

Executive Summary: Our proposed Environmental Education Program is designed to provide engaging and interactive educational opportunities for individuals of all ages. By combining classroom learning, hands-on activities, and community engagement, we aim to create a long-lasting impact on environmental conservation practices and attitudes.

Introduction: The state of our environment is facing significant challenges, including climate change, habitat loss, and pollution. It is essential to equip individuals with the knowledge and skills to understand these issues and take action. This proposal seeks to bridge the gap in environmental education and inspire a sense of environmental stewardship among the community.

Problem Statement: The lack of environmental education programs has resulted in limited awareness and understanding of environmental issues. As a result, individuals are less likely to adopt sustainable practices or actively contribute to conservation efforts. Our program aims to address this gap and empower individuals to become environmentally conscious and responsible citizens.

Proposed Solution or Project Description: Our Environmental Education Program will comprise a range of activities, including workshops, field trips, and community initiatives. We will collaborate with local schools, community centers, and environmental organizations to ensure broad participation and maximum impact. By incorporating interactive learning experiences, such as nature walks, recycling drives, and eco-craft sessions, we aim to make environmental education engaging and enjoyable.

Methodology: Our program will be structured into modules that cover key environmental themes, such as biodiversity, climate change, waste management, and sustainable living. Each module will include a mix of classroom sessions, hands-on activities, and practical field experiences. We will also leverage technology, such as educational apps and online resources, to enhance learning outcomes.

Evaluation and Success Metrics: We will employ a combination of quantitative and qualitative measures to evaluate the effectiveness of the program. Pre- and post-assessments will gauge knowledge gain, while surveys and feedback forms will assess participant satisfaction and behavior change. We will also track the number of community engagement activities and the adoption of sustainable practices as indicators of success.

Budget: Please find attached a detailed budget breakdown for the implementation of the Environmental Education Program. The budget covers personnel costs, materials and supplies, transportation, and outreach expenses. We have ensured cost-effectiveness while maintaining the quality and impact of the program.

Conclusion: By implementing this Environmental Education Program, we have the opportunity to make a significant difference in our community’s environmental consciousness and practices. We are confident that this program will foster a generation of individuals who are passionate about protecting our environment and taking sustainable actions. We look forward to discussing the proposal further and working together to make a positive impact.

Thank you for your time and consideration. Should you have any questions or require additional information, please do not hesitate to contact me at [your email address or phone number].

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How To Write A Grant Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Grant Proposal – Example, Template and Guide

Business Proposal – Templates, Examples and Guide

How To Write A Research Proposal – Step-by-Step...

How To Write A Business Proposal – Step-by-Step...

Proposal – Types, Examples, and Writing Guide

Writing Reports and Proposals

Build a solid base of confident writing skills to present information in formal, informal, and proposal styles.

- Description

- Additional Information

It is essential to understand how to write reports and proposals that get read. We write reports in a range of formats and a variety of purposes. Whether you need to report on a product analysis, inventory, feasibility studies, or something else, report writing is a skill you will use again and again.

Having a method to prepare these documents will help you be as efficient as possible with the task. This course will build on a solid base of writing skills to present information in formal, informal, and proposal styles.

Course Content

- Module One: Getting Started

- Module Two: Understanding Proposals

- Module Three: Beginning the Proposal Writing Process

- Module Four: Preparing An Outline

- Module Five: Finding Facts

- Module Six: Writing Skills (I)

- Module Seven: Writing Skills (II)

- Module Eight: Writing the Proposal

- Module Nine: Checking for Readability

- Module Ten: Proofreading and Editing

- Module Eleven: Adding the Final Touches

- Module Twelve: Wrapping Up

Estimated Course Duration

Certificate.

A participation certificate will be issued upon completion of the course.

Similar Items

You may also like.

$24.00 Adult Learning - Physical Skills Adult Learning - Physical Skills Understand the principles of adult learning. Find out more Add to Cart

$24.00 Adult Learning - Mental Skills Adult Learning - Mental Skills Understand the principles of adult learning. Find out more Add to Cart

$22.00 Research Skills Research Skills Learn how to research any topic using a range of tools and resources,… Find out more Add to Cart

We use cookies to enhance the user experience on our website and deliver our services. We also use cookies to show you relevant advertising. Read the UW Privacy Policy and more about our use of cookies .

- Programs & Courses

- Entire Site

Business Writing: Reports, Proposals & Documents

Course details.

- Location: Online

- Duration: 7 weeks

- Times: Evenings

- Cost : $1,160

Next Start Date:

October 1, 2024

About this Course

Documents are the currency for exchanging ideas in all industries around the world. All companies — large and small — rely on reports, proposals, research papers and narratives to share ideas, articulate vision and strategy, communicate plans and lead change. Knowing how to write well is an essential skill for anyone who wants to excel in the workplace.

In this course, you’ll learn what constitutes good business writing and how to write effective documents that are clear and concise. We’ll explore various kinds of business documents and focus on the importance of structure and writing to different audiences. Drawing on reader science, you’ll learn how to write persuasively and make your documents intuitive and readable without simplifying your ideas to the point of losing pertinent details. You’ll also receive instruction and coaching on how to build and use rubrics and learn tools for effective editing.

DESIGNED FOR

Technical and nontechnical professionals in any field who want to advance their career using well-researched and well-written narratives, proposals and reports.

See Requirements

- Requirements

Admission Requirements

This is an introductory course and no previous experience is required. Anyone is encouraged to enroll.

Want some background before you enroll in this course? Consider signing up for our free Business English Communication Skills Specialization first.

Time Commitment

Including time in class, you should expect to spend about seven to nine hours each week on coursework.

English Proficiency

If English is not your native language, you should have advanced English skills to enroll. To see if you qualify, make sure you are at the C1 level on the CEFR self-assessment grid . To learn more, see English Language Proficiency Requirements – Noncredit Programs .

International Students

Because this offering is 100% online, no visa is required and international students are welcome to apply. For more information, see Admission Requirements for International Students .

Technology Requirements

- Access to a computer with a recent operating system and web browser

- Understanding of the basic functions of Zoom

- High-speed internet connection

- Headset and webcam (recommended)

Completing the Course

To successfully complete this course, you must fulfill the requirements outlined by your instructor.

WHAT YOU'LL LEARN

- How to choose the right structure and style for your document

- How to design and organize content with your audience in mind

- Best practices for clear, concise and effective writing and editing

- Tips for when and when not to use visual elements such as analytics, graphics and white space to enhance readability

- How to develop and identify voice and tone in your and your colleagues’ writing

GET HANDS-ON EXPERIENCE

- Prepare detailed business documents with the help of colleagues in a writers room environment

- Write business documents with a group under the same time constraints found in current business climates

- Learn how professional writers create and edit documents with an eye toward accuracy under tight deadlines

OUR ENROLLMENT COACHES ARE HERE TO HELP

Connect with an enrollment coach to learn more about this offering. Or if you need help finding the right certificate, specialization or course for you, reach out to explore your options .

Business Writing: Reports, Proposals & Documents

Approved by the UW Department of English

Learning Format

Online With Real-Time Meetings

Combine the convenience of online learning with the immediacy of real-time interaction. You’ll meet with your instructor and classmates at scheduled times over Zoom. Learn More »

Course Sessions

October 2024 noncredit, october 2024 — online, application deadline.

Applications are open until Tuesday, September 17, 2024, at 11:59 p.m. Pacific Time, or until the course fills, whichever comes first.

APPLICATION STEPS

This course has an automatic acceptance process. Once you complete the application and pay the application fee, you’re in. See the steps below for more details.

You’ll apply to the course on MyContinuum, our student app. MyContinuum helps you seamlessly manage the enrollment process and more.

S TEP 1: REVIEW REQUIREMENTS

Before you apply, carefully read the admission requirements on the Requirements tab above. In the application, you’ll be asked to confirm that you meet these requirements.

If you have any questions, or want to make sure this course is right for you, reach out to Enrollment Services at [email protected] or 800-506-1325.

STEP 2: APPLY

Complete the online application on the MyContinuum app. You’ll need to create an account first. If you already have a UW NetID, choose that option. Otherwise, sign in with a Google or Apple account.

Apply Online

STEP 3: PAY THE APPLICATION FEE

Next, pay the $50 nonrefundable application fee through MyContinuum. Your application is not complete until you pay this fee.

AFTER APPLYING

Once you’re accepted, we’ll ask you to complete a questionnaire on MyContinuum to help us learn more about you. Then you’ll get details about how to register for your course and pay your course fee.

To ensure your spot in class, we recommend that you register by the priority registration deadline, which is four weeks before class begins. After that time, we may release your seat to another student. The final registration deadline is two days before the course starts.

RELATED RESOURCES

- Applying to a Course

- Drops, Withdrawals & Refunds

All times are Pacific Time.

Meet your instructor

Owner and Instructor, Master of the Story

NONCREDIT COURSE

You'll earn 2.4 continuing education units (CEUs) for successfully completing this course. Learn more about noncredit options .

April 2025 Noncredit

April 2025 — online.

Applications are open until Wednesday, March 26, 2025, at 11:59 p.m. Pacific Time, or until the course fills, whichever comes first.

Want to get the latest?

Sign up to get program updates, including info sessions and application deadlines.

Get Program Updates

By submitting my information, I consent to be contacted and agree to the terms and conditions outlined in the privacy policy .

Related Articles

Today's 3 must-have business skills.

Gain or refresh key skills needed to stand out in the modern workplace with courses in business writing, data analysis and project management.

Jobs for Wordsmiths in Today’s Tech-Driven Market

Wondering about career options for wordsmiths today? Good news: Even in our information age, companies need content experts. See where you can put your skills to work.

Programs for Writers and Editors

Want to craft your own story, shape others’ words or produce consistent copy as a marketer, copywriter or technical writer? Check out our numerous writing and editing programs to find the right fit for you.

7 In-Demand Technical Writing Niches

Learn about the different kinds of technical writing jobs that are prevalent in this fast-growing field.

related offerings

Build practical skills in various types of editing and develop the expertise to transform a rough draft into a polished work.

Proofreading Essentials

Learn how to proofread a variety of print and digital materials and how to use traditional proofreader’s marks as well as digital markup techniques.

Developmental Editing

Learn developmental editing skills by working on manuscripts, book proposals, article pitches and letters to the author.

Regulatory Medical Writing

Learn how to write regulatory documents and summarize clinical trial data. Gain experience crafting documents for regulatory submission and become familiar with the prescribed formats.

The Art of Writing

Explore the essential principles and practices for developing your narrative voice and creating writing worth reading.

Paralegal Studies

Build an understanding of the U.S. legal system and explore the major aspects of court systems, hearings, trials and litigation. Acquire the knowledge and skills to work as a paralegal.

Storytelling & Content Strategy

Discover storytelling principles that will help you engage your target audience and learn how to develop a powerful cross-channel content strategy with measurable goals.

Professional Technical Writing

Explore the fundamental concepts and practical applications of technical writing. Learn the styles, formats and requirements for different kinds of technical communication.

Talk to an Enrollment Coach

Our enrollment coaches can help you determine if the Business Writing: Reports, Proposals & Documents course is right for you. Your coach can also support you as you apply and enroll. Start the conversation!

By submitting my information, I consent to be contacted and agree to the privacy policy .

Subscribe to Keep Learning!

Be among the first to get timely program info, career tips, event invites and more.

- Contact sales

Start free trial

How to Write a Project Proposal (Examples & Template Included)

Table of Contents

Types of project proposals, project proposal vs. project charter, project proposal vs. business case, project proposal vs. project plan, project proposal outline, how to write a project proposal, project proposal example, project proposal tips, what is a project proposal.

A project proposal is a project management document that’s used to define the objectives and requirements of a project. It helps organizations and external project stakeholders agree on an initial project planning framework.

The main purpose of a project proposal is to get buy-in from decision-makers. That’s why a project proposal outlines your project’s core value proposition; it sells value to both internal and external project stakeholders. The intent of the proposal is to grab the attention of stakeholders and project sponsors. Then, the next step is getting them excited about the project summary.

Getting into the heads of the audience for which you’re writing the project proposal is vital: you need to think like the project’s stakeholders to deliver a proposal that meets their needs.

We’ve created a free project proposal template for Word to help structure documents, so you don’t have to remember the process each time.

Get your free

Project Proposal Template

Use this free Project Proposal Template for Word to manage your projects better.

In terms of types of project proposals, you can have one that’s formally solicited, informally solicited or a combination. There can also be renewal and supplemental proposals. Here’s a brief description of each of them.

- Solicited project proposal: This is sent as a response to a request for proposal (RFP) . Here, you’ll need to adhere to the RFP guidelines of the project owner.

- Unsolicited project proposal: You can send project proposals without having received a request for a proposal. This can happen in open bids for construction projects , where a project owner receives unsolicited project proposals from many contractors.

- Informal project proposal: This type of project proposal is created when a client asks for an informal proposal without an RFP.

- Renewal project proposal: You can use a renewal project proposal when you’re reaching out to past customers. The advantage is that you can highlight past positive results and future benefits.

- Continuation project proposal: A continuation project proposal is sent to investors and stakeholders to communicate project progress.

- Supplemental project proposal: This proposal is sent to investors to ask for additional resources during the project execution phase.

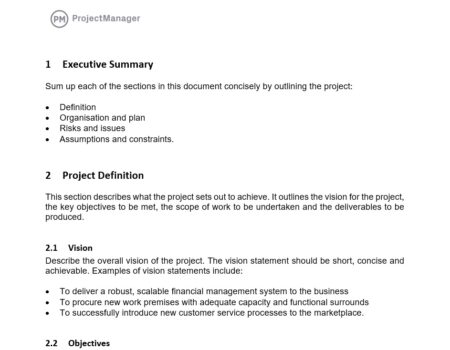

All the elements in the above project proposal outline are present in our template. This free project proposal template for Word will provide you with everything you need to write an excellent project proposal. It will help you with the executive summary, project process, deliverables, costs—even terms and conditions. Download your free template today.

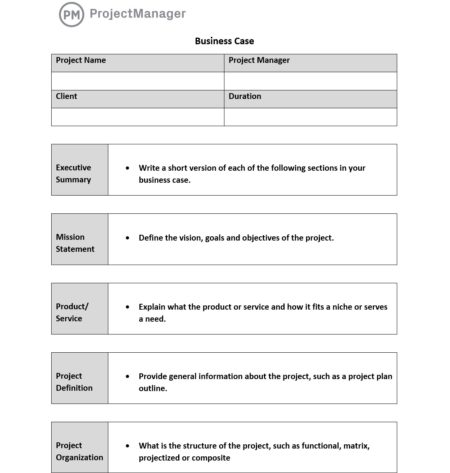

A project proposal is a detailed project document that’s used to convince the project sponsor that the project being proposed is worth the time, money and effort to deliver it. This is done by showing how the project will address a business problem or opportunity. It also outlines the work that will be done and how it will be done.

A project charter can seem like the same thing as a project proposal as it also defines the project in a document. It identifies the project objectives, scope, goals, stakeholders and team. But it’s done after the project has been agreed upon by all stakeholders and the project has been accepted. The project charter authorizes the project and documents its requirements to meet stakeholders’ needs.

A business case is used to explain why the proposed project is justified. It shows that the project is worth the investment of time and money. It’s more commonly used in larger companies in the decision-making process when prioritizing one project over another.

The business case answers the questions: what is the project, why should it be taken up, who will be involved and how much will it cost? It’s therefore related to a project proposal, but the project proposal comes before the business case and is usually part of the larger proposal.

Again, the project proposal and the project plan in this case are very similar documents. It’s understandable that there would be some confusion between these two project terms. They both show how the project will be run and what the results will be. However, they’re not the same.

The project proposal is a document that aims to get a project approved and funded. It’s used to convince stakeholders of the viability of the project and their investment. The project plan, on the other hand, is made during the planning phase of the project, once it’s been approved. It’s a detailed outline of how the project will be implemented, including schedule, budget, resources and more.

There are several key operational and strategic questions to consider, including:

- Executive summary: This is the elevator pitch that outlines the project being proposed and why it makes business sense. While it also touches on the information that’ll follow in the project proposal, the executive summary should be brief and to the point.

- Project background: This is another short part of the proposal, usually only one page, which explains the problem you’ll solve or the opportunity you’re taking advantage of with the proposed project. Also, provide a short history of the business to put the company in context to the project and why it’s a good fit.

- Project vision & success criteria: State the goal of the project and how it aligns with the goals of the company. Be specific. Also, note the metrics used to measure the success of the project.

- Potential risks and mitigation strategies: There are always risks. Detail them here and what strategies you’ll employ to mitigate any negative impact as well as take advantage of any positive risk.

- Project scope & deliverables: Define the project scope, which is all the work that has to be done and how it will be done. Also, detail the various deliverables that the project will have.

- Set SMART goals: When setting goals, be SMART. That’s an acronym for specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound. All your goals would be defined by those five things.

- Project approach: Define the approach you’ll use for the contract. There are several different types of contracts used in construction , for example, such as lump sum, cost plus, time and materials, etc. This is also a good place to describe the delivery method you’ll use.

- Expected benefits: Outline the benefits that will come from the successful completion of the project.

- Project resource requirements: List the resources, such as labor, materials, equipment, etc., that you’ll need to execute the project if approved.

- Project costs & budget: Detail all the costs, including resources, that’ll be required to complete the project and set up a budget to show how those costs will be spent over the course of the project.

- Project timeline: Lay out the project timeline , which shows the project from start to finish, including the duration of each phase and the tasks within it, milestones, etc.

In addition to these elements, it’s advisable to use a cover letter, which is a one-page document that helps you introduce your project proposal and grab the attention of potential clients and stakeholders.

To make the best proposal possible, you’ll want to be thorough and hit on all the points we’ve listed above. Here’s a step-by-step guide to writing a persuasive priority proposal.

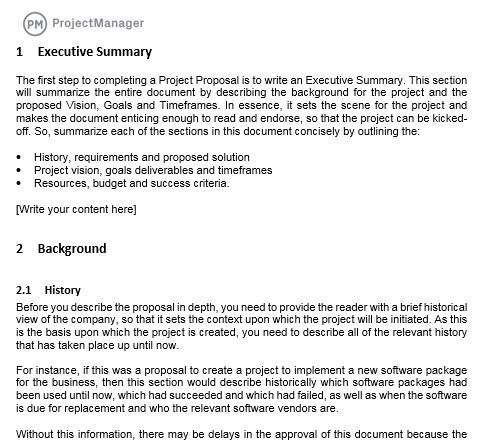

1. Write an Executive Summary

The executive summary provides a quick overview of the main elements of your project proposal, such as your project background, project objectives and project deliverables, among other things. The goal is to capture the attention of your audience and get them excited about the project you’re proposing. It’s essentially the “elevator pitch” for the project life cycle. It should be short and to the point.

The executive summary should be descriptive and paint a picture of what project success looks like for the client. Most importantly, it should motivate the project client; after all, the goal is getting them to sign on the dotted line to get the project moving!

2. Provide a Project Background

The project background is a one-page section of your project proposal that explains the problem that your project will solve. You should explain when this issue started, its current state and how your project will be the ideal solution.

- Historic data: The history section outlines previously successful projects and those that could have run more smoothly. By doing so, this section establishes precedents and how the next project can be more effective using information from previous projects.

- Solution: The solution section addresses how your project will solve the client’s problem. Accordingly, this section includes any project management techniques , skills and procedures your team will use to work efficiently.

3. Establish a Project Vision & Success Criteria

You’ll need to define your project vision. This is best done with a vision statement, which acts as the north star for your project. It’s not specific as much as it’s a way to describe the impact your company plans to make with the project.

It’s also important to set up success criteria to show that the project is in fact doing what it’s proposed to do. Three obvious project success criteria are the triple constraint of cost, scope and time. But you’ll need to set up a way to measure these metrics and respond to them if they’re not meeting your plan.

4. Identify Potential Risks and Mitigation Strategies

To reduce the impact of risk in your project, you need to identify what those risks might be and develop a plan to mitigate them . List all the risks, prioritize them, describe what you’ll do to mitigate or take advantage of them and who on the team is responsible for keeping an eye out for them and resolving them.

5. Define Your Project Scope and Project Deliverables

The project scope refers to all the work that’ll be executed. It defines the work items, work packages and deliverables that’ll be delivered during the execution phase of your project life cycle. It’s important to use a work breakdown structure (WBS) to define your tasks and subtasks and prioritize them.

6. Set SMART Goals for Your Project Proposal

The best mindset when developing goals and objectives for your project proposal is to use the SMART system :

- Specific – Make sure your goals and objectives are clear, concise and specific to the task at hand.

- Measurable – Ensure your goals and objectives are measurable so it’s obvious to see when things are on track and going well, and conversely, when things are off track and issues need to be addressed. Measurable goals make it easy to develop the milestones you’ll use to track the progress of the project and identify a reasonable date for completion and/or closure.

- Attainable – It’s important every project has a “reach” goal. Hitting this goal would mean an outstanding project that extends above and beyond expectations. However, it’s important that the project’s core goal is attainable, so morale stays high and the job gets done with time and resources to spare.

- Relevant – Make sure all of your goals are directly relevant to the project and address the scope within which you’re working.

- Time-Based – Timelines and specific dates should be at the core of all goals and objectives. This helps keep the project on track and ensures all project team members can manage the work that’s ahead of them.

7. Explain What’s Your Project Approach

Your project approach defines the project management methodology , tools and governance for your project. In simple terms, it allows project managers to explain to stakeholders how the project will be planned, executed and controlled successfully.

8. Outline The Expected Benefits of Your Project Proposal

If you want to convince internal stakeholders and external investors, you’ll need to show them the financial benefits that your project could bring to their organization. You can use cost-benefit analysis and projected financial statements to demonstrate why your project is profitable.

9. Identify Project Resource Requirements

Project resources are critical for the execution of your project. The project proposal briefly describes what resources are needed and how they’ll be used. Later, during the planning phase, you’ll need to create a resource management plan that’ll be an important element of your project plan. Project requirements are the items, materials and resources needed for the project. This section should cover both internal and external needs.

10. Estimate Project Costs and Project Budget

All the resources that you’ll need for your project have a price tag. That’s why you need to estimate those costs and create a project budget . The project budget needs to cover all your project expenses, and as a project manager, you’ll need to make sure that you adhere to the budget.

11. Define a Project Timeline

Once you’ve defined your project scope, you’ll need to estimate the duration of each task to create a project timeline. Later during the project planning phase , you’ll need to create a schedule baseline, which estimates the total length of your project. Once the project starts, you’ll compare your actual project schedule to the schedule baseline to monitor progress.

Now let’s explore some project proposal examples to get a better understanding of how a project proposal would work in the real world. For this example, let’s imagine a city that’s about to build a rapid transit system. The city government has the funds to invest but lacks the technical expertise and resources that are needed to build it, so it issues a request for proposal (RFP) document and sends it to potential builders.

Then, the construction companies that are interested in executing this rapid transit project will prepare a project proposal for the city government. Here are some of the key elements they should include.

- Project background: The construction firm will provide an explanation of the challenges that the project presents from a technical perspective, along with historical data from similar projects that have been completed successfully by the company.

- Project vision & success criteria: Write a vision statement and explain how you’ll track the triple constraint to ensure the successful delivery of the project.

- Potential risks and mitigation strategies: List all risks and how they’ll be mitigated, and be sure to prioritize them.

- Project scope & deliverables: The work that’ll be done is outlined in the scope, including all the deliverables that’ll be completed over the life cycle of the project.

- Set SMART goals: Use the SMART technique to define your project goals by whether they’re specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound.

- Project approach: Define the methodology that the project manager will employ to manage the project. Also, figure out what type of contract will be used to define the project.

- Expected benefits: Show how the project will deliver advantages to the company and define what these benefits are in a quantifiable way.

- Project resource requirements: List all the resources, such as labor, materials, equipment, etc., needed to execute the project.

- Project costs & budget: Estimate the cost of the project and lay that out in a project budget that covers everything from start to finish.

- Project timeline: Outline the project schedule, including phases, milestones and task duration on a visual timeline.

Whatever project proposal you’re working on, there are a few tips that apply as best practices for all. While above we suggested a project proposal template that would have a table of contents, meaning it would be many pages long, the best-case scenario is keeping the proposal to one or two pages max. Remember, you’re trying to win over stakeholders, not bore them.

Speaking of project stakeholders , do the research. You want to address the right ones. There’s no point in doing all the work necessary to write a great proposal only to have it directed to the wrong target audience. Whoever is going to read it, though, should be able to comprehend the proposal. Keep the language simple and direct.

When it comes to writing, get a professional. Even a business document like a project proposal, business case or executive summary will suffer if it’s poorly constructed or has typos. If you don’t want to hire a professional business writer, make sure you get someone on your project team to copy, edit and proof the document. The more eyes on it, the less likely mistakes will make it to the final edition.

While you want to keep the proposal short and sweet, it helps to sweeten the pot by adding customer testimonials to the attachments. Nothing sells a project plan better than a customer base looking for your product or service.

ProjectManager & Project Proposals

ProjectManager allows you to plan proposals within our software. You can update tasks for the project proposal to signify where things stand and what’s left to be done. The columns allow you to organize your proposal by section, creating a work breakdown structure (WBS) of sorts.

When building a project proposal, it’s vital to remember your target audience. Your audience includes those who are excited about the project, and see completion as a gain for their organization. Conversely, others in your audience will see the project as a pain and something to which they aren’t looking forward. To keep both parties satisfied, it’s essential to keep language factual and concise.

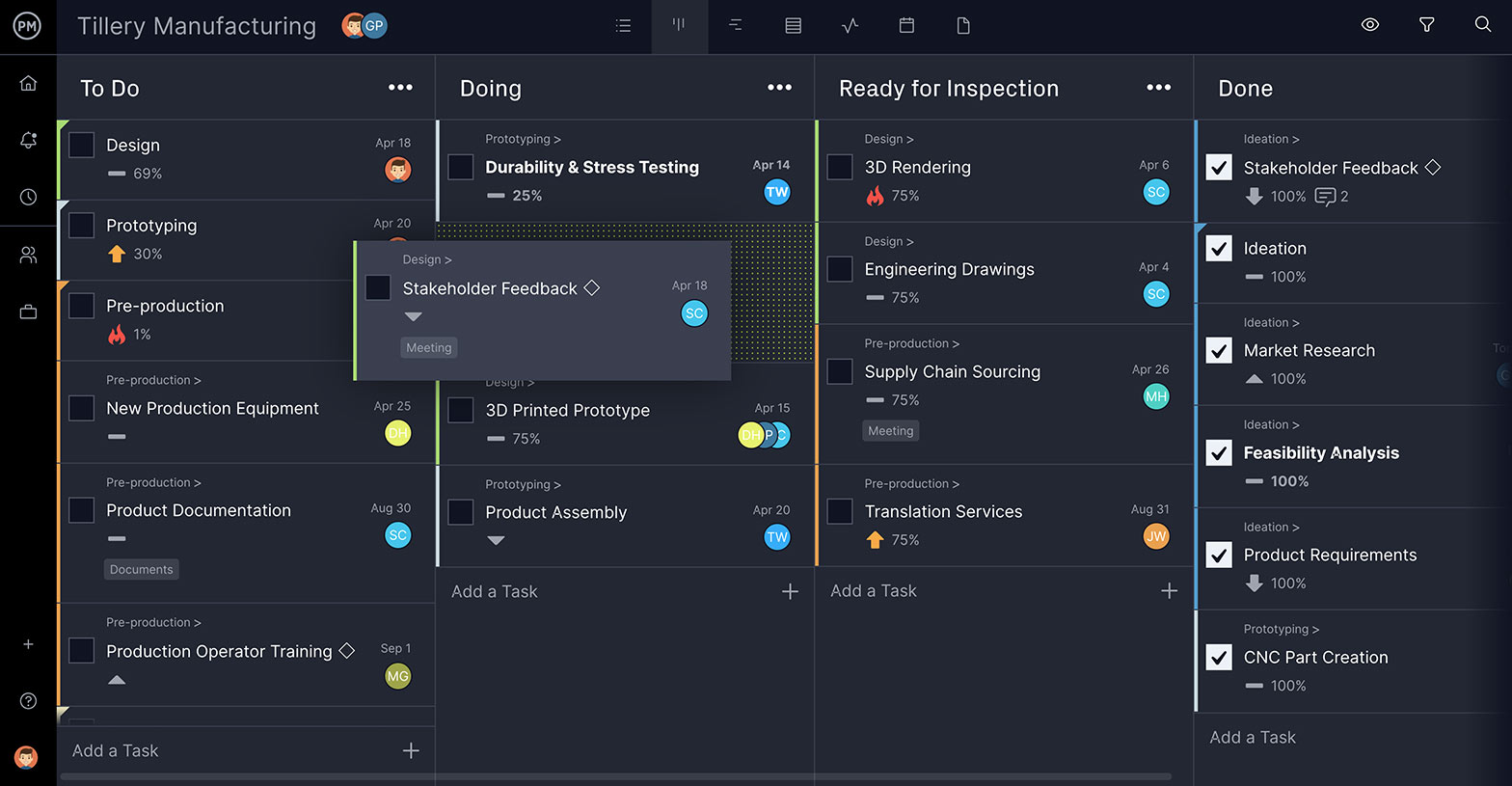

Our online kanban boards help you think through that language and collaborate on it effectively with other team members, if necessary. Each card shows the percentage completed so everyone in the project management team is aware of the work done and what’s left to be done.

As you can see from the kanban board above, work has begun on tasks such as product documentation and design. Tasks regarding stakeholder feedback, ideation, market research and more have been completed, and there’s a good start on the engineering drawings, 3D rendering, supply chain sourcing and translation services.

A PDF is then attached to the card, and everyone added to the task receives an email notifying them of the change. This same process can be used throughout the life-cycle of the project to keep the team updated, collaborating, and producing a first-class project proposal. In addition to kanban boards, you can also use other project management tools such as Gantt charts , project dashboards, task lists and project calendars to plan, schedule and track your projects.

Project proposals are just the first step in the project planning process. Once your project is approved, you’ll have to solidify the plan, allocate and manage resources, monitor the project, and finally hand in your deliverables. This process requires a flexible, dynamic and robust project management software package. ProjectManager is online project management software that helps all your team members collaborate and manage this process in real-time. Try our award-winning software with this free 30-day trial .

Deliver your projects on time and on budget

Start planning your projects.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7. COMMON DOCUMENT TYPES

7.2 Proposals

Proposals and progress reports are some of the most common types of reports you will likely find yourself writing in the workplace. These reports are persuasive in nature: proposals attempt to persuade the reader to accept the writer’s proposed idea; progress reports assure the reader that the project is on time and on budget, or explain rationally why things might not be going according to the initial plan.

A proposal, in the technical sense, is a document that tries to persuade the reader to implement a proposed plan or approve a proposed project. Most businesses rely on effective proposal writing to ensure successful continuation of their business and to get new contracts. The writer tries to convince the reader that the proposed plan or project is worth doing (worth the time, energy, and expense necessary to implement or see through), that the author represents the best candidate for implementing the idea, and that it will result in tangible benefits.

Proposals are often written in response to a Request For Proposals (RFP) by a government agency, organization, or company. The requesting body receives multiple proposals responding to their request, reviews the submitted proposals, and chooses the best one(s) to go forward. Their evaluation of the submitted proposals is often based on a rubric that grades various elements of the proposals. Thus, your proposal must persuade the reader that your idea is the one most worth pursuing. Proposals are persuasive documents intended to initiate a project and get the reader to authorize a course of action proposed in the document. These might include proposals to

- Perform a task (such as conducting a feasibility study, a research project, etc. )

- Provide a product

- Provide a service

Proposals can have various purposes and thus take many forms. Depending on the kind of proposal you are writing, they may include some of the following sections:

- Introduction and/or background

- Statement of problem to be solved (or opportunity to improve or innovate)

- Purpose/motivation/goal/objectives

- Definition of scope and approach (limitations)

- Review of the state of the art; market analysis

- Stakeholder analysis

- Technical background

- Project description

- Schedule of work/timeline

- Validation plan; or Marketing plan

- Qualifications

A proposal in a business context might have sections that focus on market analysis, customer profiles, and more focus on financial planning. A more technical proposal might place more emphasis on technical descriptions, reviewing the state of art technology, and creating a plan for validating the solution.

Four Kinds of Proposals

There are 4 kinds of proposals, categorized in terms of whether or not they were requested, and whether they are meant to solve a problem within your own organization or someone else’s. From the following descriptions, you will see that can they also overlap:

- Solicited Proposals: an organization identifies a situation it wants to improve or problem that it wants to solve and issues an RFP (Request for Proposals) asking for proposals on how to address it. The requesting organization will vet proposals and choose the most convincing one, often using a detailed scoring rubric or weighted objectives chart to determine which proposal best responds to the request.

- Unsolicited Proposals: a writer perceives a problem or an opportunity and takes the initiative to propose a way to solve the problem or take advantage of the opportunity (without being requested to do so). This can often be the most difficult kind of proposal to get approved.

- Internal Proposals: these are written by and for someone within the same organization. Since both the writer and reader share the same workplace context, these proposals are generally shorter than external proposals, and usually address some way to improve a work-related situation (productivity, efficiency, profit, etc .). As internal documents, they are often sent as memos, or introduced with a memo if the proposal is lengthy.

- External Proposals : these are sent outside of the writer’s organization to a separate entity (usually to solicit business). Since these are external documents, they are usually sent as a formal report (if long), introduced by a cover letter (letter of transmittal). External proposals are usually sent in response to a Request for Proposals, but not always.

EXERCISE 7.1 Task Analysis

If you are writing a proposal, identify the kind of proposals you are tasked with writing by placing them within the grid below. Given the kinds of proposals you must write, what forms will you use (memo, letter, report, etc .)?

Proposals written as an assignment in a Technical Writing classes generally do the following:

- Identify and define the problem that needs to be solved or the opportunity that can be taken advantage of. You must show that you clearly understand the problem/situation if you are to convince the reader that you can solve it. Rubrics that assess proposals generally place significant weight (~20%) on clarity and accuracy of the problem definition.

- Describe your proposed project, clearly defining the scope of what you propose to do. Often, it is best to give a general overview of your idea, and then break it down into more detailed sub-sections.

- Indicate how your proposed solution will solve the problem and provide tangible benefits. Specifically, indicate how it will meet the objectives and abide by the constrains outlined in the problem definition. Give specific examples. Show the specific differences between “how things are now” and “how they could be.” Be as empirical as possible, but appeal to all appropriate persuasive strategies. Emphasize results, benefits, and feasibility of your proposed idea.

- Include the practical details: propose a budget and a timeline for completing your project. Represent these graphically (budget table, and Gantt chart) . Your timeline should include the major milestones or deliverables of the project, as well as dates or time frames for completion of each step.

- Conclude with a final pitch that summarizes and emphasizes the benefits of implementing your proposed idea – but without sounding like an advertisement.

Additional Proposal Elements to Consider

- Describe your qualifications to take on and/or lead this project; persuade the reader that you have the required skills, experience, and expertise to complete this job.

- Decide what graphics to use to illustrate your ideas, present data, and enhance your pitch.

- Include secondary research to enhance your credibility and the strength of your proposal.

- Choose format; is this a memo to an internal audience or a formal report to an external audience? Does it require a letter of transmittal?

All proposals must be convincing, logical, and credible, and to do this, they must consider audience, purpose and tone.

Irish and Weiss [2] urge readers to keep the following in mind:

An engineering proposal is not an advertisement. It must show, with objective language, clarity, and thoroughness, that the writers know what they are doing and will successfully complete the project.

Sample Proposal Organization

Each proposal will be unique in that it must address a particular audience, in a particular context, for a specific purpose. However, the following offers a fairly standard organization for many types of proposals:

| Clearly and fully defines the problem or opportunity addressed by the proposal, and presents the solution idea; convinces the reader that there is a clear need, and a clear benefit to the proposed idea. | |

| Detailed description of solution idea and detailed explanation of how the proposed idea will improve the situation: | |

| Establish writer’s qualifications and experience to lead this project. | |

| Provide a detailed timeline for completion of project (use a Gantt chart to indicate when each stage of the project will be complete). Provide an itemized budget for completing the proposed project. | |

| This is your last chance to convince the reader; be persuasive! | |

| List your research sources. |

Language Considerations

Proposals are fundamentally persuasive documents, so paying attention to the rhetorical situation—position of the reader (upward, lateral, downward or outward communication), the purpose of the proposal, the form, and the tone—is paramount.

- Clearly define your purpose and audience before you begin to write

- Be sure you have done research so you know what you are talking about

- Remain positive and constructive: you are seeking to improve a situation

- Be solution oriented; don’t blame or dwell on the negative

- Make your introduction very logical, objective, and empirical; don’t start off sounding like an advertisement or sounding biased; avoid logical fallacies

- Use primarily logical and ethical appeals; use emotional appeals sparingly

As always, adhere to the 7 Cs by making sure that your writing is

- Clear and Coherent : don’t confuse your reader with unclear ideas or an illogically organized structure.

- Concise and Courteous : don’t annoy your reader with clutter, unnecessary padding, inappropriate tone, or hard-to-read formatting.

- Concrete and Complete : avoid vague generalities; give specifics. Don’t leave out necessary information.

- Correct : don’t undermine your professional credibility by neglecting grammar and spelling, or by including inaccurate information.

The Life Cycle of a Project Idea

A great idea does not usually go straight from proposal to implementation. You may think it would be a great idea to construct a green roof on top of the Clearihue building, but before anyone gives you the go ahead for such an expensive and time-consuming project, they will need to know that you have done research to ensure the idea is cost effective and will actually work. Figure 7.2.1 breaks down the various stages a project might go through, and identifies some of the typical communications tasks that might be required at each stage.

Most ideas start out as a proposal to determine if the idea is really feasible, or to find out which of several options will be most advantageous. So before you propose the actual green roof, you propose to study whether or not it is a feasible idea. Before you recommend a data storage system, you propose to study 3 different systems to find out which is the best one for this particular situation . Your proposal assumes the idea is worth looking into, convinces the reader that it is worth spending the time and resources to look into, and gives detailed information on how you propose to do the “finding out.”

Once a project is in the implementation phase, the people who are responsible for the project will likely want regular status updates and/or progress reports to make sure that the project is proceeding on time and on budget, or to get a clear, rational explanation for why it is not. To learn more about Progress Reports, go to 7.3 Progress Reports .

Image descriptions

Figure 7.2.1 image description:

Once there is an idea, a project goes through a design process made up of four stages.

- Problem Definition – identifying needs, goals, objectives, and constraints.

- Define context and do research.

- Identify potential projects.

- Public engagement projects; Stakeholder consultation.

- Propose a project (budget, timeline, etc.).

- Create or respond to a request for proposals, evaluate proposals.

- Develop or design solution concepts.

- Project management plan.

- Feasibility Studies, Recommendation Reports).

- Write contracts and apply for permits for construction and building sites.

- Progress reports, status updates.

- Documentation of project.

- Continued research and design improvements.

- Final reports and documentation.

- Close contracts.

- Ongoing Support: User Guides, Troubleshooting, FAQs.

[Return to Figure 7.2.1]

- [Proposal image]. [Online]. Available: https://pixabay.com/en/couple-love-marriage-proposal-47192/. Pixabay License. ↵

- R. Irish and P. Weiss, Engineering Communication: From Principle to Practice , 2nd Ed., Don Mill, ONT: Oxford UP, 2013. ↵

- [Lightbulb image]. [Online]. Available: https://www.iconfinder.com/icons/667355/aha_brilliance_idea_think_thought_icon. Free for commercial use . ↵

Technical Writing Essentials Copyright © 2019 by Suzan Last is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Table of Contents

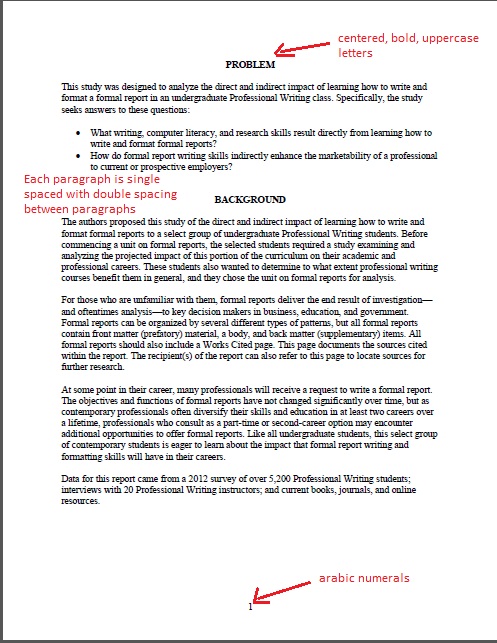

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, formal reports.

- © 2023 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College , Katherine McGee

Formal Reports are a common genre of discourse in business and academic settings . Formal Reports are fancy. They aren’t one-offs. They tend to written by teams of people, often distributed teams. And they often report results from substantive textual research and empirical research . Corporations invest substantial sums to produce formal reports.

Formal Reports tend to share these organizational characteristics:

- front matter (prefatory) material

- back matter (supplementary) items.

Key Words: Organizational Schema

Many business professionals need to write a formal report at some point during their career, and some professionals write them on a regular basis. Knowledge Workers in business, education, and government use formal reports to make important decisions.

The purposes for Formal Reports vary across occasions , professions, disciplinary communities . They tend to be high stakes documents. Common types of formal reports include

- Personnel Evaluation Reports

- Feasibility Reports

- Recommendation Reports

Analyze Your Audience