Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

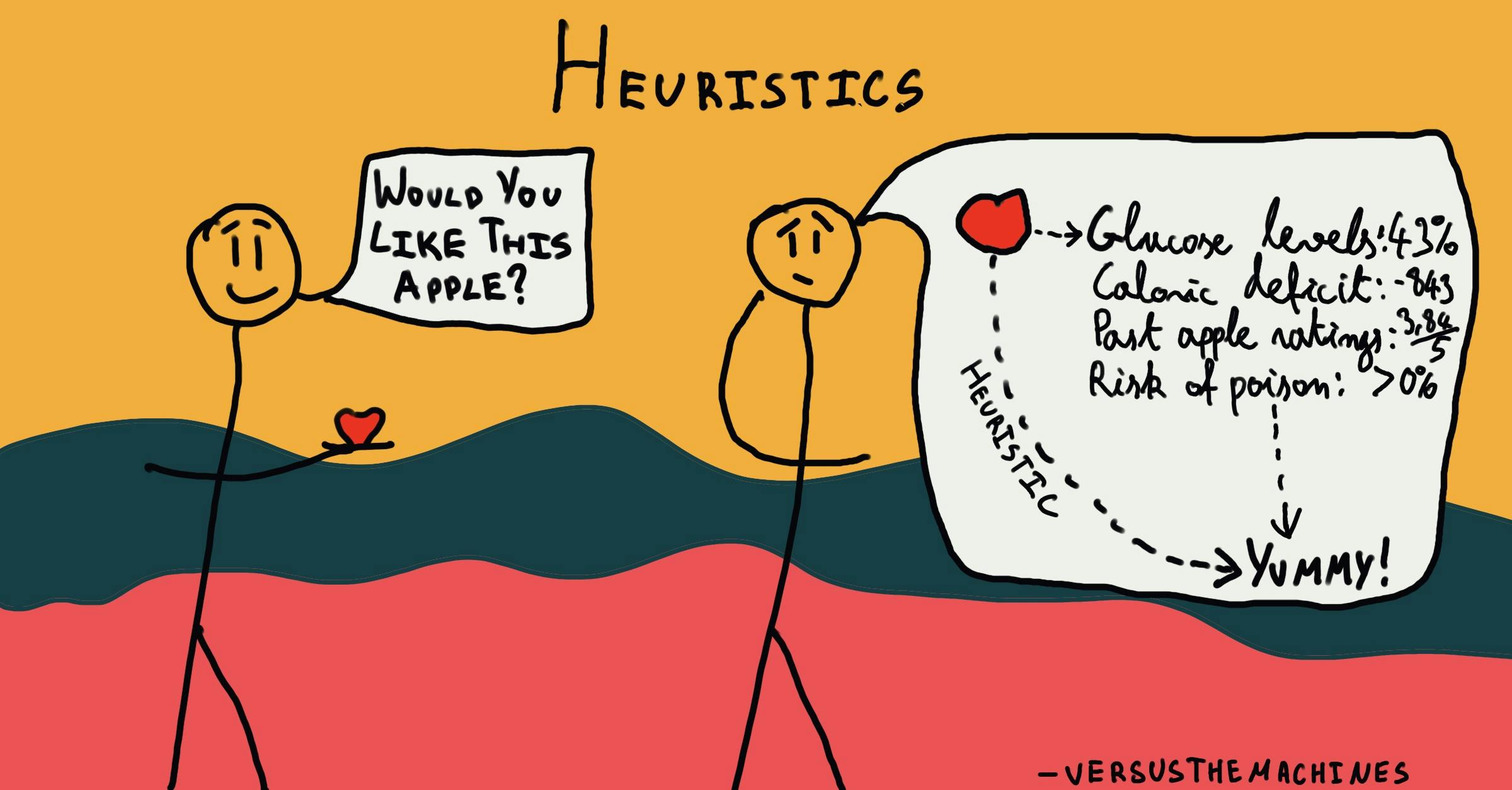

A heuristic is a mental shortcut that allows an individual to make a decision, pass judgment, or solve a problem quickly and with minimal mental effort. While heuristics can reduce the burden of decision-making and free up limited cognitive resources, they can also be costly when they lead individuals to miss critical information or act on unjust biases.

- Understanding Heuristics

- Different Heuristics

- Problems with Heuristics

As humans move throughout the world, they must process large amounts of information and make many choices with limited amounts of time. When information is missing, or an immediate decision is necessary, heuristics act as “rules of thumb” that guide behavior down the most efficient pathway.

Heuristics are not unique to humans; animals use heuristics that, though less complex, also serve to simplify decision-making and reduce cognitive load.

Generally, yes. Navigating day-to-day life requires everyone to make countless small decisions within a limited timeframe. Heuristics can help individuals save time and mental energy, freeing up cognitive resources for more complex planning and problem-solving endeavors.

The human brain and all its processes—including heuristics— developed over millions of years of evolution . Since mental shortcuts save both cognitive energy and time, they likely provided an advantage to those who relied on them.

Heuristics that were helpful to early humans may not be universally beneficial today . The familiarity heuristic, for example—in which the familiar is preferred over the unknown—could steer early humans toward foods or people that were safe, but may trigger anxiety or unfair biases in modern times.

The study of heuristics was developed by renowned psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Starting in the 1970s, Kahneman and Tversky identified several different kinds of heuristics, most notably the availability heuristic and the anchoring heuristic.

Since then, researchers have continued their work and identified many different kinds of heuristics, including:

Familiarity heuristic

Fundamental attribution error

Representativeness heuristic

Satisficing

The anchoring heuristic, or anchoring bias , occurs when someone relies more heavily on the first piece of information learned when making a choice, even if it's not the most relevant. In such cases, anchoring is likely to steer individuals wrong .

The availability heuristic describes the mental shortcut in which someone estimates whether something is likely to occur based on how readily examples come to mind . People tend to overestimate the probability of plane crashes, homicides, and shark attacks, for instance, because examples of such events are easily remembered.

People who make use of the representativeness heuristic categorize objects (or other people) based on how similar they are to known entities —assuming someone described as "quiet" is more likely to be a librarian than a politician, for instance.

Satisficing is a decision-making strategy in which the first option that satisfies certain criteria is selected , even if other, better options may exist.

Heuristics, while useful, are imperfect; if relied on too heavily, they can result in incorrect judgments or cognitive biases. Some are more likely to steer people wrong than others.

Assuming, for example, that child abductions are common because they’re frequently reported on the news—an example of the availability heuristic—may trigger unnecessary fear or overprotective parenting practices. Understanding commonly unhelpful heuristics, and identifying situations where they could affect behavior, may help individuals avoid such mental pitfalls.

Sometimes called the attribution effect or correspondence bias, the term describes a tendency to attribute others’ behavior primarily to internal factors—like personality or character— while attributing one’s own behavior more to external or situational factors .

If one person steps on the foot of another in a crowded elevator, the victim may attribute it to carelessness. If, on the other hand, they themselves step on another’s foot, they may be more likely to attribute the mistake to being jostled by someone else .

Listen to your gut, but don’t rely on it . Think through major problems methodically—by making a list of pros and cons, for instance, or consulting with people you trust. Make extra time to think through tasks where snap decisions could cause significant problems, such as catching an important flight.

Artificial intelligence already plays a role in deciding who’s getting hired. The way to improve AI is very similar to how we fight human biases.

Think you are avoiding the motherhood penalty by not having children? Think again. Simply being a woman of childbearing age can trigger discrimination.

Psychological experiments on human judgment under uncertainty showed that people often stray from presumptions about rational economic agents.

Psychology, like other disciplines, uses the scientific method to acquire knowledge and uncover truths—but we still ask experts for information and rely on intuition. Here's why.

We all experience these 3 cognitive blind spots at work, frequently unaware of their costs in terms of productivity and misunderstanding. Try these strategies to work around them.

Have you ever fallen for fake news? This toolkit can help you easily evaluate whether a claim is real or phony.

An insidious form of prejudice occurs when a more powerful group ignores groups with less power and keeps them out of the minds of society.

We can never know everything and yet unconscious biases often convince us that we do. Being alert to your own ignorance is crucial for more efficient thinking in daily life.

Chatbot designers engage in dishonest anthropomorphism by designing features to exploit our heuristic processing and dupe us into overtrusting and assigning moral responsibility.

How do social media influencers convert a scroll into a like, follow, and sale? Here are the psychological principles used by digital influencers.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Heuristics: Definition, Examples, And How They Work

Benjamin Frimodig

Science Expert

B.A., History and Science, Harvard University

Ben Frimodig is a 2021 graduate of Harvard College, where he studied the History of Science.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Every day our brains must process and respond to thousands of problems, both large and small, at a moment’s notice. It might even be overwhelming to consider the sheer volume of complex problems we regularly face in need of a quick solution.

While one might wish there was time to methodically and thoughtfully evaluate the fine details of our everyday tasks, the cognitive demands of daily life often make such processing logistically impossible.

Therefore, the brain must develop reliable shortcuts to keep up with the stimulus-rich environments we inhabit. Psychologists refer to these efficient problem-solving techniques as heuristics.

Heuristics can be thought of as general cognitive frameworks humans rely on regularly to reach a solution quickly.

For example, if a student needs to decide what subject she will study at university, her intuition will likely be drawn toward the path that she envisions as most satisfying, practical, and interesting.

She may also think back on her strengths and weaknesses in secondary school or perhaps even write out a pros and cons list to facilitate her choice.

It’s important to note that these heuristics broadly apply to everyday problems, produce sound solutions, and helps simplify otherwise complicated mental tasks. These are the three defining features of a heuristic.

While the concept of heuristics dates back to Ancient Greece (the term is derived from the Greek word for “to discover”), most of the information known today on the subject comes from prominent twentieth-century social scientists.

Herbert Simon’s study of a notion he called “bounded rationality” focused on decision-making under restrictive cognitive conditions, such as limited time and information.

This concept of optimizing an inherently imperfect analysis frames the contemporary study of heuristics and leads many to credit Simon as a foundational figure in the field.

Kahneman’s Theory of Decision Making

The immense contributions of psychologist Daniel Kahneman to our understanding of cognitive problem-solving deserve special attention.

As context for his theory, Kahneman put forward the estimate that an individual makes around 35,000 decisions each day! To reach these resolutions, the mind relies on either “fast” or “slow” thinking.

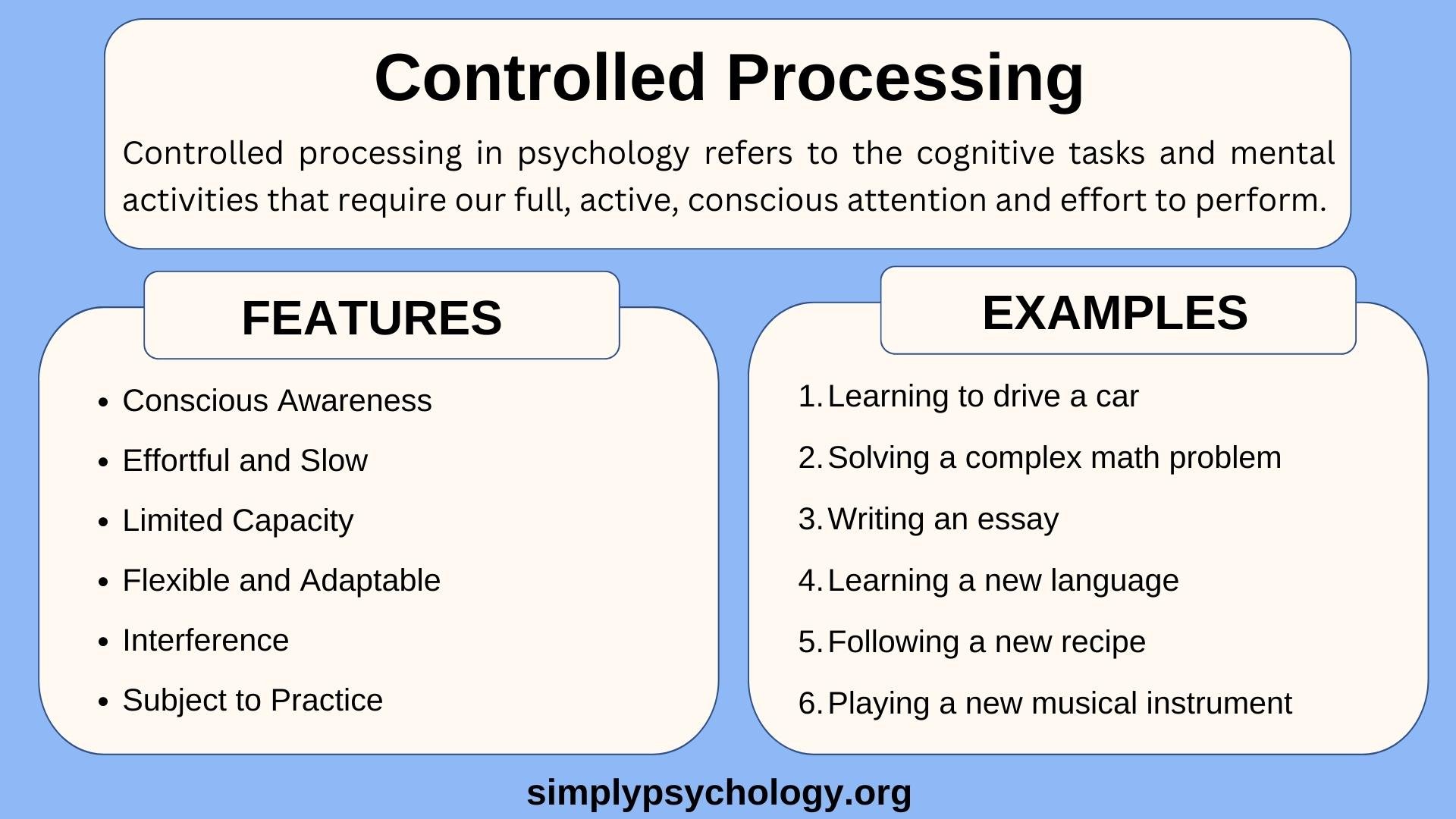

The fast thinking pathway (system 1) operates mostly unconsciously and aims to reach reliable decisions with as minimal cognitive strain as possible.

While system 1 relies on broad observations and quick evaluative techniques (heuristics!), system 2 (slow thinking) requires conscious, continuous attention to carefully assess the details of a given problem and logically reach a solution.

Given the sheer volume of daily decisions, it’s no surprise that around 98% of problem-solving uses system 1.

Thus, it is crucial that the human mind develops a toolbox of effective, efficient heuristics to support this fast-thinking pathway.

Heuristics vs. Algorithms

Those who’ve studied the psychology of decision-making might notice similarities between heuristics and algorithms. However, remember that these are two distinct modes of cognition.

Heuristics are methods or strategies which often lead to problem solutions but are not guaranteed to succeed.

They can be distinguished from algorithms, which are methods or procedures that will always produce a solution sooner or later.

An algorithm is a step-by-step procedure that can be reliably used to solve a specific problem. While the concept of an algorithm is most commonly used in reference to technology and mathematics, our brains rely on algorithms every day to resolve issues (Kahneman, 2011).

The important thing to remember is that algorithms are a set of mental instructions unique to specific situations, while heuristics are general rules of thumb that can help the mind process and overcome various obstacles.

For example, if you are thoughtfully reading every line of this article, you are using an algorithm.

On the other hand, if you are quickly skimming each section for important information or perhaps focusing only on sections you don’t already understand, you are using a heuristic!

Why Heuristics Are Used

Heuristics usually occurs when one of five conditions is met (Pratkanis, 1989):

- When one is faced with too much information

- When the time to make a decision is limited

- When the decision to be made is unimportant

- When there is access to very little information to use in making the decision

- When an appropriate heuristic happens to come to mind at the same moment

When studying heuristics, keep in mind both the benefits and unavoidable drawbacks of their application. The ubiquity of these techniques in human society makes such weaknesses especially worthy of evaluation.

More specifically, in expediting decision-making processes, heuristics also predispose us to a number of cognitive biases .

A cognitive bias is an incorrect but pervasive judgment derived from an illogical pattern of cognition. In simple terms, a cognitive bias occurs when one internalizes a subjective perception as a reliable and objective truth.

Heuristics are reliable but imperfect; In the application of broad decision-making “shortcuts” to guide one’s response to specific situations, occasional errors are both inevitable and have the potential to catalyze persistent mistakes.

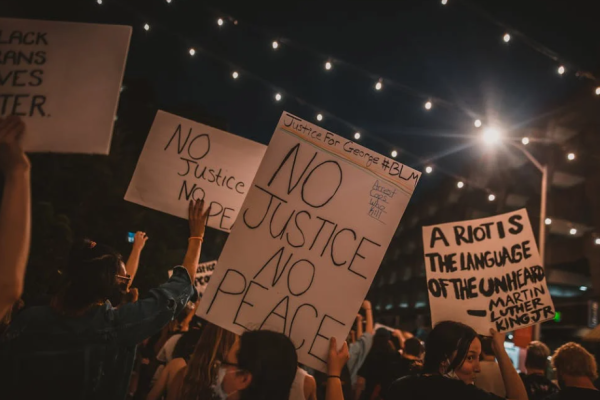

For example, consider the risks of faulty applications of the representative heuristic discussed above. While the technique encourages one to assign situations into broad categories based on superficial characteristics and one’s past experiences for the sake of cognitive expediency, such thinking is also the basis of stereotypes and discrimination.

In practice, these errors result in the disproportionate favoring of one group and/or the oppression of other groups within a given society.

Indeed, the most impactful research relating to heuristics often centers on the connection between them and systematic discrimination.

The tradeoff between thoughtful rationality and cognitive efficiency encompasses both the benefits and pitfalls of heuristics and represents a foundational concept in psychological research.

When learning about heuristics, keep in mind their relevance to all areas of human interaction. After all, the study of social psychology is intrinsically interdisciplinary.

Many of the most important studies on heuristics relate to flawed decision-making processes in high-stakes fields like law, medicine, and politics.

Researchers often draw on a distinct set of already established heuristics in their analysis. While dozens of unique heuristics have been observed, brief descriptions of those most central to the field are included below:

Availability Heuristic

The availability heuristic describes the tendency to make choices based on information that comes to mind readily.

For example, children of divorced parents are more likely to have pessimistic views towards marriage as adults.

Of important note, this heuristic can also involve assigning more importance to more recently learned information, largely due to the easier recall of such information.

Representativeness Heuristic

This technique allows one to quickly assign probabilities to and predict the outcome of new scenarios using psychological prototypes derived from past experiences.

For example, juries are less likely to convict individuals who are well-groomed and wearing formal attire (under the assumption that stylish, well-kempt individuals typically do not commit crimes).

This is one of the most studied heuristics by social psychologists for its relevance to the development of stereotypes.

Scarcity Heuristic

This method of decision-making is predicated on the perception of less abundant, rarer items as inherently more valuable than more abundant items.

We rely on the scarcity heuristic when we must make a fast selection with incomplete information. For example, a student deciding between two universities may be drawn toward the option with the lower acceptance rate, assuming that this exclusivity indicates a more desirable experience.

The concept of scarcity is central to behavioral economists’ study of consumer behavior (a field that evaluates economics through the lens of human psychology).

Trial and Error

This is the most basic and perhaps frequently cited heuristic. Trial and error can be used to solve a problem that possesses a discrete number of possible solutions and involves simply attempting each possible option until the correct solution is identified.

For example, if an individual was putting together a jigsaw puzzle, he or she would try multiple pieces until locating a proper fit.

This technique is commonly taught in introductory psychology courses due to its simple representation of the central purpose of heuristics: the use of reliable problem-solving frameworks to reduce cognitive load.

Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic

Anchoring refers to the tendency to formulate expectations relating to new scenarios relative to an already ingrained piece of information.

Put simply, this anchoring one to form reasonable estimations around uncertainties. For example, if asked to estimate the number of days in a year on Mars, many people would first call to mind the fact the Earth’s year is 365 days (the “anchor”) and adjust accordingly.

This tendency can also help explain the observation that ingrained information often hinders the learning of new information, a concept known as retroactive inhibition.

Familiarity Heuristic

This technique can be used to guide actions in cognitively demanding situations by simply reverting to previous behaviors successfully utilized under similar circumstances.

The familiarity heuristic is most useful in unfamiliar, stressful environments.

For example, a job seeker might recall behavioral standards in other high-stakes situations from her past (perhaps an important presentation at university) to guide her behavior in a job interview.

Many psychologists interpret this technique as a slightly more specific variation of the availability heuristic.

How to Make Better Decisions

Heuristics are ingrained cognitive processes utilized by all humans and can lead to various biases.

Both of these statements are established facts. However, this does not mean that the biases that heuristics produce are unavoidable. As the wide-ranging impacts of such biases on societal institutions have become a popular research topic, psychologists have emphasized techniques for reaching more sound, thoughtful and fair decisions in our daily lives.

Ironically, many of these techniques are themselves heuristics!

To focus on the key details of a given problem, one might create a mental list of explicit goals and values. To clearly identify the impacts of choice, one should imagine its impacts one year in the future and from the perspective of all parties involved.

Most importantly, one must gain a mindful understanding of the problem-solving techniques used by our minds and the common mistakes that result. Mindfulness of these flawed yet persistent pathways allows one to quickly identify and remedy the biases (or otherwise flawed thinking) they tend to create!

Further Information

- Shah, A. K., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2008). Heuristics made easy: an effort-reduction framework. Psychological bulletin, 134(2), 207.

- Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 14(1), 77.

- Del Campo, C., Pauser, S., Steiner, E., & Vetschera, R. (2016). Decision making styles and the use of heuristics in decision making. Journal of Business Economics, 86(4), 389-412.

What is a heuristic in psychology?

A heuristic in psychology is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb that simplifies decision-making and problem-solving. Heuristics often speed up the process of finding a satisfactory solution, but they can also lead to cognitive biases.

Bobadilla-Suarez, S., & Love, B. C. (2017, May 29). Fast or Frugal, but Not Both: Decision Heuristics Under Time Pressure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition .

Bowes, S. M., Ammirati, R. J., Costello, T. H., Basterfield, C., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2020). Cognitive biases, heuristics, and logical fallacies in clinical practice: A brief field guide for practicing clinicians and supervisors. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51 (5), 435–445.

Dietrich, C. (2010). “Decision Making: Factors that Influence Decision Making, Heuristics Used, and Decision Outcomes.” Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse, 2(02).

Groenewegen, A. (2021, September 1). Kahneman Fast and slow thinking: System 1 and 2 explained by Sue. SUE Behavioral Design. Retrieved March 26, 2022, from https://suebehaviouraldesign.com/kahneman-fast-slow-thinking/

Kahneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011). Before you make that big decision .

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow . Macmillan.

Pratkanis, A. (1989). The cognitive representation of attitudes. In A. R. Pratkanis, S. J. Breckler, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Attitude structure and function (pp. 71–98). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Simon, H.A., 1956. Rational choice and the structure of the environment. Psychological Review .

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science, 185 (4157), 1124–1131.

Related Articles

Cognitive Psychology

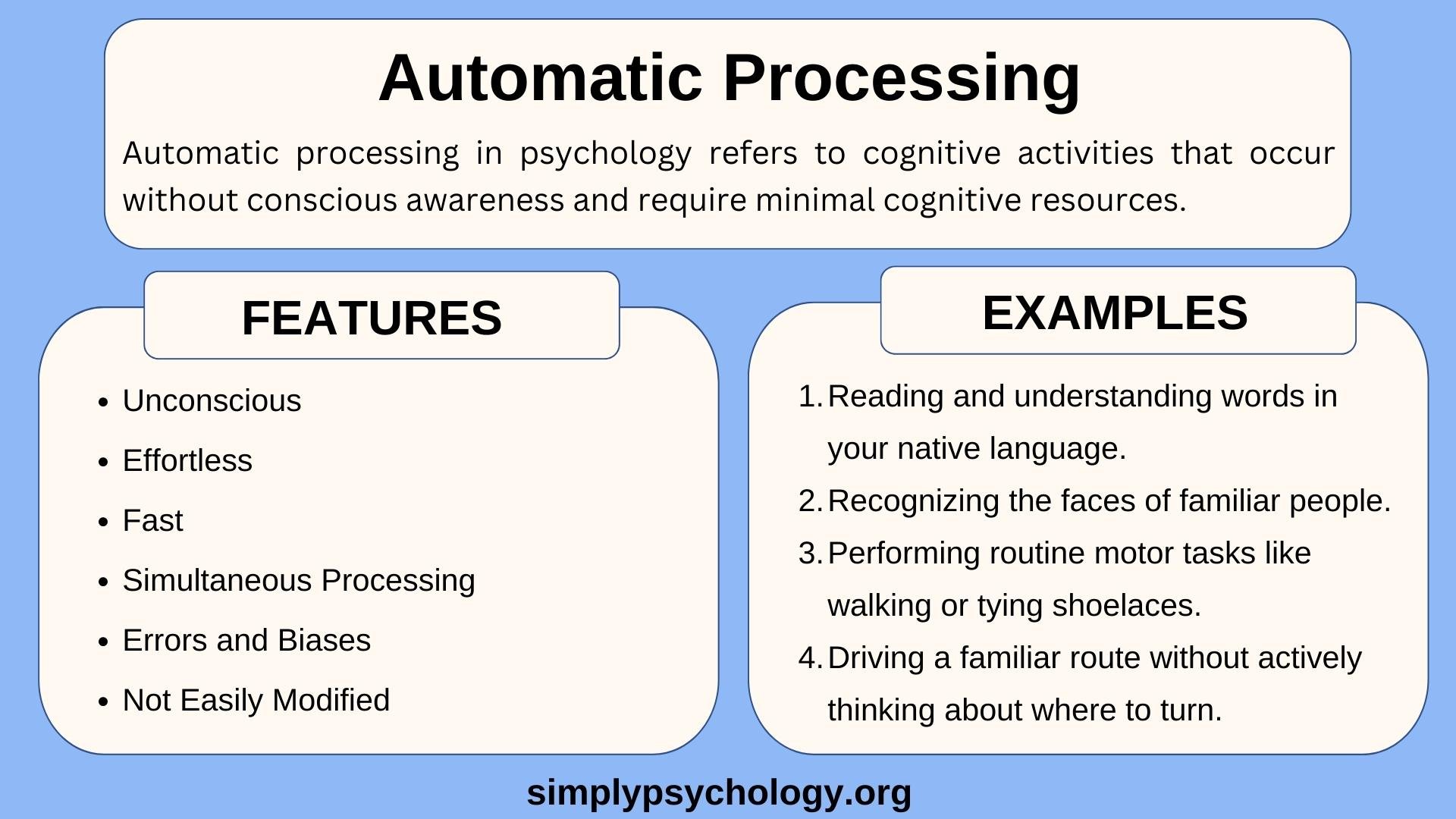

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

How Ego Depletion Can Drain Your Willpower

What is the Default Mode Network?

Theories of Selective Attention in Psychology

Availability Heuristic and Decision Making

- Product overview

- All features

- App integrations

CAPABILITIES

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- asana-intelligence icon Asana Intelligence

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Campaign management

- Creative production

- Content calendars

- Marketing strategic planning

- Resource planning

- Project intake

- Product launches

- Employee onboarding

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- What's new Learn about the latest and greatest from Asana

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Support Need help? Contact the Asana support team

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

Featured Reads

- Business strategy |

- What are heuristics and how do they hel ...

What are heuristics and how do they help us make decisions?

Heuristics are simple rules of thumb that our brains use to make decisions. When you choose a work outfit that looks professional instead of sweatpants, you’re making a decision based on past information. That's not intuition; it’s heuristics. Instead of weighing all the information available to make a data-backed choice, heuristics enable us to move quickly into action—mostly without us even realizing it. In this article, you’ll learn what heuristics are, their common types, and how we use them in different scenarios.

Green means go. Most of us accept this as common knowledge, but it’s actually an example of a micro-decision—in this case, your brain is deciding to go when you see the color green.

You make countless of these subconscious decisions every day. Many things that you might think just come naturally to you are actually caused by heuristics—mental shortcuts that allow you to quickly process information and take action. Heuristics help you make smaller, almost unnoticeable decisions using past information, without much rational input from your brain.

Heuristics are helpful for getting things done more quickly, but they can also lead to biases and irrational choices if you’re not aware of them. Luckily, you can use heuristics to your advantage once you recognize them, and make better decisions in the workplace.

What is a heuristic?

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that your brain uses to make decisions. When we make rational choices, our brains weigh all the information, pros and cons, and any relevant data. But it’s not possible to do this for every single decision we make on a day-to-day basis. For the smaller ones, your brain uses heuristics to infer information and take almost-immediate action.

Decision-making tools for agile businesses

In this ebook, learn how to equip employees to make better decisions—so your business can pivot, adapt, and tackle challenges more effectively than your competition.

How heuristics work

For example, if you’re making a larger decision about whether to accept a new job or stay with your current one, your brain will process this information slowly. For decisions like this, you collect data by referencing sources—chatting with mentors, reading company reviews, and comparing salaries. Then, you use that information to make your decision. Meanwhile, your brain is also using heuristics to help you speed along that track. In this example, you might use something called the “availability heuristic” to reference things you’ve recently seen about the new job. The availability heuristic makes it more likely that you’ll remember a news story about the company’s higher stock prices. Without realizing it, this can make you think the new job will be more lucrative.

On the flip side, you can recognize that the new job has had some great press recently, but that might be just a great PR team at work. Instead of “buying in” to what the availability heuristic is trying to tell you—that positive news means it’s the right job—you can acknowledge that this is a bias at work. In this case, comparing compensation and work-life balance between the two companies is a much more effective way to choose which job is right for you.

History of heuristics

The term "heuristics," originating from the Greek word meaning “to discover,” has ancient roots, but much of today's understanding comes from twentieth-century social scientists. Herbert Simon's research into "bounded rationality" highlighted the use of heuristics in decision-making, particularly under constraints like limited time and information.

Daniel Kahneman was one of the first researchers to study heuristics in his behavioral economics work in the 1970’s, along with fellow psychologist Amos Tversky. They theorized that many of the decisions and judgments we make aren’t rational—meaning we don’t move through a series of decision-making steps to come to a solution. Instead, the human brain uses mental shortcuts to form seemingly irrational, “fast and frugal” decisions—quick choices that don’t require a lot of mental energy.

Kahneman’s work showed that heuristics lead to systematic errors (or biases), which act as the driving force for our decisions. He was able to apply this research to economic theory, leading to the formation of behavioral economics and a Nobel Prize for Kahneman in 2002.

In the years since, the study of heuristics has grown in popularity with economists and in cognitive psychology. Gerd Gigerenzer’s research , for example, challenges the idea that heuristics lead to errors or flawed thinking. He argues that heuristics are actually indicators that human beings are able to make decisions more effectively without following the traditional rules of logic. His research seems to indicate that heuristics lead us to the right answer most of the time.

Types of heuristics

Heuristics are everywhere, whether we notice them or not. There are hundreds of heuristics at play in the human brain, and they interact with one another constantly. To understand how these heuristics can help you, start by learning some of the more common types of heuristics.

Recognition heuristic

The recognition heuristic uses what we already know (or recognize) as a criterion for decisions. The concept is simple: When faced with two choices, you’re more likely to choose the item you recognize versus the one you don’t.

This is the very base-level concept behind branding your business, and we see it in all well-known companies. Businesses develop a brand messaging strategy in the hopes that when you’re faced with buying their product or buying someone else's, you recognize their product, have a positive association with it, and choose that one. For example, if you’re going to grab a soda and there are two different cans in the fridge, one a Coca-Cola, and the other a soda you’ve never heard of, you are more likely to choose the Coca-Cola simply because you know the name.

Familiarity heuristic

The familiarity heuristic is a mental shortcut where individuals prefer options or information that is familiar to them. This heuristic is based on the notion that familiar items are seen as safer or superior. It differs from the recognition heuristic, which relies solely on whether an item is recognized. The familiarity heuristic involves a deeper sense of comfort and understanding, as opposed to just recognizing something.

An example of this heuristic is seen in investment decisions. Investors might favor well-known companies over lesser-known ones, influenced more by brand familiarity than by an objective assessment of the investment's potential. This tendency showcases how the familiarity heuristic can lead to suboptimal choices, as it prioritizes comfort and recognition over a thorough evaluation of all available options.

Availability heuristic

The availability heuristic is a cognitive bias where people judge the frequency or likelihood of events based on how easily similar instances come to mind. This mental shortcut depends on the most immediate examples that pop into one's mind when considering a topic or decision. The ease of recalling these instances often leads to a distorted perception of their actual frequency, as recent, dramatic, or emotionally charged memories tend to be more memorable.

A notable example of the availability heuristic is the public's reaction to shark attacks. When the media reports on shark attacks, these incidents become highly memorable due to their dramatic nature, leading people to overestimate the risk of such events. This heightened perception is despite statistical evidence showing the rarity of shark attacks. The result is an exaggerated fear and a skewed perception of the actual danger of swimming in the ocean.

Representativeness heuristic

The representativeness heuristic is when we try to assign an object to a specific category or idea based on past experiences. Oftentimes, this comes up when we meet people—our first impression. We expect certain things (such as clothing and credentials) to indicate that a person behaves or lives a certain way.

Without proper awareness, this heuristic can lead to discrimination in the workplace. For example, representativeness heuristics might lead us to believe that a job candidate from an Ivy League school is more qualified than one from a state university, even if their qualifications show us otherwise. This is because we expect Ivy League graduates to act a certain way, such as by being more hard-working or intelligent. Of course, in our rational brains, we know this isn’t the case. That’s why it’s important to be aware of this heuristic, so you can use logical thinking to combat potential biases.

Anchoring and adjustment heuristic

Used in finance for economic forecasting, anchoring and adjustment is when you start with an initial piece of information (the anchor) and continue adjusting until you reach an acceptable decision. The challenge is that sometimes the anchor ends up not being a good enough value to begin with. In other words, you choose the anchor based on unknown biases and then make further decisions based on this faulty assumption.

Anchoring and adjustment are often used in pricing, especially with SaaS companies. For example, a displayed, three-tiered pricing model shows you how much you get for each price point. The layout is designed to make it look like you won’t get much for the lower price, and you don’t necessarily need the highest price, so you choose the mid-level option (the original target). The anchors are the low price (suggesting there’s not much value here) and the high price (which shows that you’re getting a "discount" if you choose another option). Thanks to those two anchors, you feel like you’re getting a lot of value, no matter what you spend.

Affect heuristic

You know the advice; think with your heart. That’s the affect heuristic in action, where you make a decision based on what you’re feeling. Emotions are important ways to understand the world around us, but using them to make decisions is irrational and can impact your work.

For example, let’s say you’re about to ask your boss for a promotion. As a product marketer, you’ve made a huge impact on the company by helping to build a community of enthusiastic, loyal customers. But the day before you have your performance review , you find out that a small project you led for a new product feature failed. You decide to skip the conversation asking for a raise and instead double down on how you can improve.

In this example, you’re using the affect heuristic to base your entire performance on the failure of one small project—even though the rest of your performance (building that profitable community) is much more impactful than a new product feature. If you weighed the options rationally, you would see that asking for a raise is still a logical choice. But instead, the fear of asking for a raise after a failure felt like too big a trade-off.

Satisficing

Satisficing is when you accept an available option that’s satisfactory (i.e., just fine) instead of trying to find the best possible solution. In other words, you’re settling. This creates a “bounded rationality,” where you’re constrained by the choices that are good-enough, instead of pushing past the limits to discover more. This isn’t always negative—for lower-impact scenarios, it might not make sense to invest time and energy into finding the optimal choice. But there are also times when this heuristic kicks in and you end up settling for less than what’s possible.

For example, let’s say you’re a project manager planning the budget for the next fiscal year. Instead of looking at previous spend and revenue, you satisfice and base the budget off projections, assuming that will be good enough. But without factoring in historical data, your budget isn’t going to be as equipped to manage hiccups or unexpected changes. In this case, you can mitigate satisficing with a logically-based data review that, while longer, will produce a more accurate and thoughtful budget plan.

Trial and error heuristic

The trial and error heuristic is a problem-solving method where solutions are found through repeated experimentation. It's used when a clear path to the solution isn't known, relying on iterative learning from failures and adjustments.

For example, a chef might experiment with various ingredient combinations and techniques to perfect a new recipe. Each attempt informs the next, demonstrating how trial and error facilitates discovery in situations without formal guidelines.

Pros and cons of heuristics

Heuristics are effective at helping you get more done quickly, but they also have downsides. Psychologists don’t necessarily agree on whether heuristics and biases are positive or negative. But the argument seems to boil down to these two pros and cons:

Heuristics pros:

Simple heuristics reduce cognitive load, allowing you to accomplish more in less time with fast and frugal decisions. For example, the satisficing heuristic helps you find a "good enough" choice. So if you’re making a complex decision between whether to cut costs or invest in employee well-being , you can use satisficing to find a solution that’s a compromise. The result might not be perfect, but it allows you to take action and get started—you can always adjust later on.

Heuristics cons:

Heuristics create biases. While these cognitive biases enable us to make rapid-fire decisions, they can also lead to rigid, unhelpful beliefs. For example, confirmation bias makes it more likely that you’ll seek out other opinions that agree with your own. This makes it harder to keep an open mind, hear from the other side, and ultimately change your mind—which doesn’t help you build the flexibility and adaptability so important for succeeding in the workplace.

Heuristics and psychology

Heuristics play a pivotal role in psychology, especially in understanding how people make decisions within their cognitive limitations. These mental shortcuts allow for quicker decisions, often necessary in a fast-paced world, but they can sometimes lead to errors in judgment.

The study of heuristics bridges various aspects of psychology, from cognitive processes to behavioral outcomes, and highlights the balance between efficient decision-making and the potential for bias.

Stereotypes and heuristic thinking

Stereotypes are a form of heuristic where individuals make assumptions based on group characteristics, a process analyzed in both English and American psychology.

While these generalizations can lead to rapid conclusions and rational decisions under certain circumstances, they can also oversimplify complex human behaviors and contribute to prejudiced attitudes. Understanding stereotypes as a heuristic offers insight into the cognitive limitations of the human mind and their impact on social perceptions and interactions.

How heuristics lead to bias

Because heuristics rely on shortcuts and stereotypes, they can often lead to bias. This is especially true in scenarios where cognitive limitations restrict the processing of all relevant information. So how do you combat bias? If you acknowledge your biases, you can usually undo them and maybe even use them to your advantage. There are ways you can hack heuristics, so that they work for you (not against you):

Be aware. Heuristics often operate like a knee-jerk reaction—they’re automatic. The more aware you are, the more you can identify and acknowledge the heuristic at play. From there, you can decide if it’s useful for the current situation, or if a logical decision-making process is best.

Flip the script. When you notice a negative bias, turn it around. For example, confirmation bias is when we look for things to be as we expect. So if we expect our boss to assign us more work than our colleagues, we might always experience our work tasks as unfair. Instead, turn this around by repeating that your boss has your team’s best interests at heart, and you know everyone is working hard. This will re-train your confirmation bias to look for all the ways that your boss is treating you just like everyone else.

Practice mindfulness. Mindfulness helps to build self-awareness, so you know when heuristics are impacting your decisions. For example, when we tap into the empathy gap heuristic, we’re unable to empathize with someone else or a specific situation. However, if we’re mindful, we can be aware of how we’re feeling before we engage. This helps us to see that the judgment stems from our own emotions and probably has nothing to do with the other person.

Examples of heuristics in business

This is all well and good in theory, but how do heuristic decision-making and thought processes show up in the real world? One reason researchers have invested so much time and energy into learning about heuristics is so that they can use them, like in these scenarios:

How heuristics are used in marketing

Effective marketing does so much for a business—it attracts new customers, makes a brand a household name, and converts interest into sales, to name a few. One way marketing teams are able to accomplish all this is by applying heuristics.

Let’s use ambiguity aversion as an example. Ambiguity aversion means you're less likely to choose an item you don’t know. Marketing teams combat this by working to become familiar to their customers. This could include the social media team engaging in a more empathetic or conversational way, or employing technology like chat-bots to show that there’s always someone available to help. Making the business feel more approachable helps the customer feel like they know the brand personally—which lessens ambiguity aversion.

How heuristics are used in business strategy

Have you ever noticed how your CEO seems to know things before they happen? Or that the CFO listens more than they speak? These are indications that they understand people in a deeper way, and are able to engage with their employees and predict outcomes because of it. C-suite level executives are often experts in behavioral science, even if they didn’t study it. They tend to get what makes people tick, and know how to communicate based on these biases. In short, they use heuristics for higher-level decision-making processes and execution.

This includes business strategy . For example, a startup CEO might be aware of their representativeness bias towards investors—they always look for the person in the room with the fancy suit or car. But after years in the field, they know logically that this isn’t always true—plenty of their investors have shown up in shorts and sandals. Now, because they’re aware of their bias, they can build it into their investment strategy. Instead of only attending expensive, luxury events, they also attend conferences with like-minded individuals and network among peers. This approach can lead them to a greater variety of investors and more potential opportunities.

Heuristics vs algorithms

Heuristics and algorithms are both used by the brain to reduce the mental effort of decision-making, but they operate a bit differently. Algorithms act as guidelines for specific scenarios. They have a structured process designed to solve that specific problem. Heuristics, on the other hand, are general rules of thumb that help the brain process information and may or may not reach a solution.

For example, let's say you’re cooking a well-loved family recipe. You know the steps inside and out, and you no longer need to reference the instructions. If you’re following a recipe step-by-step, you’re using an algorithm. If, however, you decide on a whim to sub in some of your fresh garden vegetables because you think it will taste better, you’re using a heuristic.

How to use heuristics to make better decisions

Heuristics can help us make decisions quickly and with less cognitive strain. While they can be efficient, they sometimes lead to errors in judgment. Understanding how to use heuristics effectively can improve decision-making, especially in complex or uncertain situations.

Take time to think

Rushing often leads to reliance on automatic heuristics, which might not always be suitable. To make better decisions, slow down your thinking process. Take a step back, breathe, and allow yourself a moment of distraction. This pause can provide a fresh perspective and help you notice details or angles you might have missed initially.

Clarify your objectives

When making a decision, it's important to understand the ultimate goal. Our automatic decision-making processes tend to favor immediate benefits, sometimes overlooking long-term impacts or the needs of others involved. Consider the broader implications of your decision. Who else is affected? Is there a common objective that benefits all parties? Such considerations can lead to more holistic and effective decisions.

Manage your emotional influences

Emotions significantly influence our decision-making, often without our awareness. Fast decisions are particularly prone to emotional biases. Acknowledge your feelings, but also separate them from the facts at hand. Are you making a decision based on solid information or emotional reactions? Distinguishing between the two can lead to more rational and balanced choices.

Beware of binary thinking

All-or-nothing thinking is a common heuristic trap, where we see decisions as black or white with no middle ground. However, real-life decisions often have multiple paths and possibilities. It's important to recognize this complexity. There might be compromises or alternative options that weren't initially considered. By acknowledging the spectrum of possibilities, you can make more nuanced and effective decisions.

Heuristic FAQs

What is heuristic thinking.

Heuristic thinking refers to a method of problem-solving, learning, or discovery that employs a practical approach—often termed a "rule of thumb"—to make decisions quickly. Heuristic thinking is a type of cognition that humans use subconsciously to make decisions and judgments with limited time.

What is a heuristic evaluation?

A heuristic evaluation is a usability inspection method used in the fields of user interface (UI) and user experience (UX) design. It involves evaluators examining the interface and judging its compliance with recognized usability principles, known as heuristics. These heuristics serve as guidelines to identify usability problems in a design, making the evaluation process more systematic and comprehensive.

What are computer heuristics?

Computer heuristics are algorithms used to solve complex problems or make decisions where an exhaustive search is impractical. In fields like artificial intelligence and cybersecurity, these heuristic methods allow for efficient problem-solving and decision-making, often based on trial and error or rule-of-thumb strategies.

What are heuristics in psychology?

In psychology, heuristics are quick mental rules for making decisions. They are important in social psychology for understanding how we think and decide. Figures like Kahneman and Tversky, particularly in their work "Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases," have influenced the study of heuristics in psychology.

Learn heuristics, de-mystify your brain

Your brain doesn’t actually work in mysterious ways. In reality, researchers know why we do a lot of the things we do. Heuristics help us to understand the choices we make that don’t make much sense. Once you understand heuristics, you can also learn to use them to your advantage—both in business, and in life.

Related resources

How to create a CRM strategy: 6 steps (with examples)

What is management by objectives (MBO)?

Write better AI prompts: A 4-sentence framework

What is content marketing? A complete guide

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Are Heuristics?

Understanding heuristics.

- Pros and Cons

- Examples in Behavioral Economics

Heuristics and Psychology

The bottom line.

- Investing Basics

Heuristics: Definition, Pros & Cons, and Examples

James Chen, CMT is an expert trader, investment adviser, and global market strategist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/photo__james_chen-5bfc26144cedfd0026c00af8.jpeg)

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that help people make quick decisions. They are rules or methods that help people use reason and past experience to solve problems efficiently. Commonly used to simplify problems and avoid cognitive overload, heuristics are part of how the human brain evolved and is wired, allowing individuals to quickly reach reasonable conclusions or solutions to complex problems. These solutions may not be optimal ones but are often sufficient given limited timeframes and calculative capacity.

These cognitive shortcuts feature prominently in behavioral economics .

Key Takeaways

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts for solving problems in a quick way that delivers a result that is sufficient enough to be useful given time constraints.

- Investors and financial professionals use a heuristic approach to speed up analysis and investment decisions.

- Heuristics can lead to poor decision-making based on a limited data set, but the speed of decisions can sometimes make up for the disadvantages.

- Behavioral economics has focused on heuristics as one limitation of human beings behaving like rational actors.

- Availability, anchoring, confirmation bias, and the hot hand fallacy are some examples of heuristics people use in their economic lives.

Investopedia / Danie Drankwalter

People employ heuristics naturally due to the evolution of the human brain. The brain can only process so much information at once and therefore must employ various shortcuts or practical rules of thumb . We would not get very far if we had to stop to think about every little detail or collect every piece of available information and integrate it into an analysis.

Heuristics therefore facilitate timely decisions that may not be the absolute best ones but are appropriate enough. Individuals are constantly using this sort of intelligent guesswork, trial and error, process of elimination, and past experience to solve problems or chart a course of action. In a world that is increasingly complex and overloaded with big data, heuristic methods make decision-making simpler and faster through shortcuts and good-enough calculations.

First identified in economics by the political scientist and organizational scholar Herbert Simon in his work on bounded rationality, heuristics have now become a cornerstone of behavioral economics.

Rather than subscribing to the idea that economic behavior was rational and based upon all available information to secure the best possible outcome for an individual ("optimizing"), Simon believed decision-making was about achieving outcomes that were "good enough" for the individual based on their limited information and balancing the interests of others. Simon called this " satisficing ," a portmanteau of the words "satisfy" and "suffice."

Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Heuristics

The main advantage to using heuristics is that they allow people to make good enough decisions without having all of the information and without having to undertake complex calculations.

Because humans cannot possibly obtain or process all the information needed to make fully rational decisions, they instead seek to use the information they do have to produce a satisfactory result, or one that is good enough. Heuristics allow people to go beyond their cognitive limits.

Heuristics are also advantageous when speed or timeliness matters—for example, deciding to enter a trade or making a snap judgment about some important decision. Heuristics are thus handy when there is no time to carefully weigh all options and their merits.

Disadvantages

There are also drawbacks to using heuristics. While they may be quick and dirty, they will likely not produce the optimal decision and can also be wrong entirely. Quick decisions without all the information can lead to errors in judgment, and miscalculations can lead to mistakes.

Moreover, heuristics leave us prone to biases that tend to lead us toward irrational economic behavior and sway our understanding of the world. Such heuristics have been identified and cataloged by the field of behavioral economics.

Quick & easy

Allows decision-making that goes beyond our cognitive capacity

Allows for snap judgments when time is limited

Often inaccurate

Can lead to systemic biases or errors in judgment

Example of Heuristics in Behavioral Economics

Representativeness.

A popular shortcut method in problem-solving identified in behavioral economics is called representativeness heuristics. Representativeness uses mental shortcuts to make decisions based on past events or traits that are representative of or similar to the current situation.

Say, for example, Fast Food ABC expanded its operations to India and its stock price soared. An analyst noted that India is a profitable venture for all fast-food chains. Therefore, when Fast Food XYZ announced its plan to explore the Indian market the following year, the analyst wasted no time in giving XYZ a "buy" recommendation.

Although their shortcut approach saved reviewing data for both companies, it may not have been the best decision. Fast Food XYZ may have food that is not appealing to Indian consumers, which research would have revealed.

Anchoring and Adjustment

Anchoring and adjustment is another prevalent heuristic approach. With anchoring and adjustment, a person begins with a specific target number or value—called the anchor—and subsequently adjusts that number until an acceptable value is reached over time. The major problem with this method is that if the value of the initial anchor is not the true value, then all subsequent adjustments will be systematically biased toward the anchor and away from the true value.

An example of anchoring and adjustment is a car salesman beginning negotiations with a very high price (that is arguably well above the fair value ). Because the high price is an anchor, the final price will tend to be higher than if the car salesman had offered a fair or low price to start.

Availability (Recency) Heuristic

The availability (or recency) heuristic is an issue where people give too much weight to the probability of an event happening again if it recently has occurred. For instance, if a shark attack is reported in the news, those headlines make the event salient and can lead people to stay away from the water, even though shark attacks remain very rare.

Another example is the case of the " hot hand ," or the sense that following a string of successes, an individual is likely to continue being successful. Whether at the casino, in the markets, or playing basketball, the hot hand has been debunked. A string of recent good luck does not alter the overall probability of events occurring.

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is a well-documented heuristic whereby people give more weight to information that fits with their existing worldviews or beliefs. At the same time, information that contradicts these beliefs is discounted or rejected.

Investors should be aware of their own tendency toward confirmation bias so that they can overcome poor decision-making, missing chances, and avoid falling prey to bubbles . Seeking out contrarian views and avoiding affirmative questions are two ways to counteract confirmation bias.

Hindsight Bias

Hindsight is always 20/20. However, the hindsight bias leads us to forget that we made incorrect predictions or estimates prior to them occurring. Rather, we become convinced that we had accurately predicted an event before it occurred, even when we did not. This can lead to overconfidence for making future predictions, or regret for not taking past opportunities.

Stereotypes

Stereotypes are a kind of heuristic that allows us to form opinions or judgments about people whom we have never met. In particular, stereotyping takes group-level characteristics about certain social groups—often ones that are racist, sexist, or otherwise discriminatory—and casts those characteristics onto all of the members in that group, regardless of their individual personalities, beliefs, skills, or behaviors.

By imposing oversimplified beliefs onto people, we can quickly judge potential interactions with them or individual outcomes of those people. However, these judgments are often plain wrong, derogatory, and perpetuate social divisions and exclusions.

Heuristics were first identified and taken seriously by scholars in the middle of the 20th century with the work of Herbert Simon, who asked why individuals and firms don't act like rational actors in the real world, even with market pressures punishing irrational decisions. Simon found that corporate managers do not usually optimize but instead rely on a set of heuristics or shortcuts to get the job done in a way that is good enough (to "satisfice").

Later, in the 1970s and '80s, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman working at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, built off of Herbert Simon's work and developed what is known as Prospect Theory . A cornerstone of behavioral economics, Prospect Theory catalogs several heuristics used subconsciously by people as they make financial evaluations.

One major finding is that people are loss-averse —that losses loom larger than gains (i.e., the pain of losing $50 is far more than the pleasure of receiving $50). Here, people adopt a heuristic to avoid realizing losses, sometimes spurring them to take excessive risks in order to do so—but often leading to even larger losses.

More recently, behavioral economists have tried to develop policy measures or "nudges" to help correct people's irrational use of heuristics in order to help them achieve more optimal outcomes—for instance, by having people enroll in a retirement savings plan by default instead of having to opt in.

What Are the Types of Heuristics?

To date, several heuristics have been identified by behavioral economics—or else developed to aid people in making otherwise complex decisions. In behavioral economics, representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability (recency) are among the most widely cited. Heuristics may be categorized in many ways, such as cognitive versus emotional biases or errors in judgment versus errors in calculation.

What Is Heuristic Thinking?

Heuristic thinking uses mental shortcuts—often unconsciously—to quickly and efficiently make otherwise complex decisions or judgments. These can be in the form of a "rule of thumb" (e.g., saving 5% of your income in order to have a comfortable retirement) or cognitive processes that we are largely unaware of like the availability bias.

What Is Another Word for Heuristic?

Heuristic may also go by the following terms: rule of thumb; mental shortcut; educated guess; or satisfice.

How Does a Heuristic Differ From an Algorithm?

An algorithm is a step-by-step set of instructions that are followed to achieve some goal or outcome, often optimizing that outcome. They are formalized and can be expressed as a formula or "recipe." As such, they are reproducible in the sense that an algorithm will always provide the same output, given the same input.

A heuristic amounts to an educated guess or gut feeling. Rather than following a set of rules or instructions, a heuristic is a mental shortcut. Moreover, it often produces sub-optimal and even irrational outcomes that may differ even when given the same input.

What Are Computer Heuristics?

In computer science, a heuristic refers to a method of solving a problem that proves to be quicker or more efficient than traditional methods. This may involve using approximations rather than precise calculations or techniques that circumvent otherwise computationally intensive routines.

Heuristics are practical rules of thumb that manifest as mental shortcuts in judgment and decision-making. Without heuristics, our brains would not be able to function given the complexity of the world, the amount of data to process, and the calculative abilities required to form an optimal decision. Instead, heuristics allow us to make quick, good-enough choices.

However, these choices may also be subject to inaccuracies and systemic biases, such as those identified by behavioral economics.

Simon, Herbert. " Herbert Simon, Innovation, and Heuristics ." Mind & Society, vol. 17, 2019, pp. 97-109.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Tversky, Amos. " Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk ." The Econometric Society, vol. 47, no. 2, 1979, pp. 263-292.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1097997046-c4faaa367277408ba55e0a3436fab769.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Heuristics: The Psychology of Mental Shortcuts

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Materials Science and Engineering, Northwestern University

- B.A., Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University

- B.A., Cognitive Science, Johns Hopkins University

Heuristics (also called “mental shortcuts” or “rules of thumb") are efficient mental processes that help humans solve problems and learn new concepts. These processes make problems less complex by ignoring some of the information that’s coming into the brain, either consciously or unconsciously. Today, heuristics have become an influential concept in the areas of judgment and decision-making.

Key Takeaways: Heuristics

- Heuristics are efficient mental processes (or "mental shortcuts") that help humans solve problems or learn a new concept.

- In the 1970s, researchers Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman identified three key heuristics: representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability.

- The work of Tversky and Kahneman led to the development of the heuristics and biases research program.

History and Origins

Gestalt psychologists postulated that humans solve problems and perceive objects based on heuristics. In the early 20th century, the psychologist Max Wertheimer identified laws by which humans group objects together into patterns (e.g. a cluster of dots in the shape of a rectangle).

The heuristics most commonly studied today are those that deal with decision-making. In the 1950s, economist and political scientist Herbert Simon published his A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice , which focused on the concept of on bounded rationality : the idea that people must make decisions with limited time, mental resources, and information.

In 1974, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman pinpointed specific mental processes used to simplify decision-making. They showed that humans rely on a limited set of heuristics when making decisions with information about which they are uncertain—for example, when deciding whether to exchange money for a trip overseas now or a week from today. Tversky and Kahneman also showed that, although heuristics are useful, they can lead to errors in thinking that are both predictable and unpredictable.

In the 1990s, research on heuristics, as exemplified by the work of Gerd Gigerenzer’s research group, focused on how factors in the environment impact thinking–particularly, that the strategies the mind uses are influenced by the environment–rather than the idea that the mind uses mental shortcuts to save time and effort.

Significant Psychological Heuristics

Tversky and Kahneman’s 1974 work, Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases , introduced three key characteristics: representativeness, anchoring and adjustment, and availability.

The representativeness heuristic allows people to judge the likelihood that an object belongs in a general category or class based on how similar the object is to members of that category.

To explain the representativeness heuristic, Tversky and Kahneman provided the example of an individual named Steve, who is “very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful, but with little interest in people or reality. A meek and tidy soul, he has a need for order and structure, and a passion for detail.” What is the probability that Steve works in a specific occupation (e.g. librarian or doctor)? The researchers concluded that, when asked to judge this probability, individuals would make their judgment based on how similar Steve seemed to the stereotype of the given occupation.

The anchoring and adjustment heuristic allows people to estimate a number by starting at an initial value (the “anchor”) and adjusting that value up or down. However, different initial values lead to different estimates, which are in turn influenced by the initial value.

To demonstrate the anchoring and adjustment heuristic, Tversky and Kahneman asked participants to estimate the percentage of African countries in the UN. They found that, if participants were given an initial estimate as part of the question (for example, is the real percentage higher or lower than 65%?), their answers were rather close to the initial value, thus seeming to be "anchored" to the first value they heard.

The availability heuristic allows people to assess how often an event occurs or how likely it will occur, based on how easily that event can be brought to mind. For example, someone might estimate the percentage of middle-aged people at risk of a heart attack by thinking of the people they know who have had heart attacks.

Tversky and Kahneman's findings led to the development of the heuristics and biases research program. Subsequent works by researchers have introduced a number of other heuristics.

The Usefulness of Heuristics

There are several theories for the usefulness of heuristics. The accuracy-effort trade-off theory states that humans and animals use heuristics because processing every piece of information that comes into the brain takes time and effort. With heuristics, the brain can make faster and more efficient decisions, albeit at the cost of accuracy.

Some suggest that this theory works because not every decision is worth spending the time necessary to reach the best possible conclusion, and thus people use mental shortcuts to save time and energy. Another interpretation of this theory is that the brain simply does not have the capacity to process everything, and so we must use mental shortcuts.

Another explanation for the usefulness of heuristics is the ecological rationality theory. This theory states that some heuristics are best used in specific environments, such as uncertainty and redundancy. Thus, heuristics are particularly relevant and useful in specific situations, rather than at all times.

- Gigerenzer, G., and Gaissmeier, W. “Heuristic decision making.” Annual Review of Psychology , vol. 62, 2011, pp. 451-482.

- Hertwig, R., and Pachur, T. “Heuristics, history of.” In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2 Edition nd , Elsevier, 2007.

- “Heuristics representativeness.” Cognitive Consonance.

- Simon. H. A. “A behavioral model of rational choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics , vol. 69, no. 1, 1955, pp. 99-118.

- Tversky, A., and Kahneman, D. “Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases.” Science , vol. 185, no. 4157, pp. 1124-1131.

- What Is Cognitive Bias? Definition and Examples

- What Is Behavioral Economics?

- What Is a Schema in Psychology? Definition and Examples

- Heuristics in Rhetoric and Composition

- Introduction to Evolutionary Psychology

- Understanding the Triarchic Theory of Intelligence

- Status Quo Bias: What It Means and How It Affects Your Behavior

- What Is the Elaboration Likelihood Model in Psychology?

- Psychodynamic Theory: Approaches and Proponents

- What Is Self-Concept in Psychology?

- Dream Interpretation According to Psychology

- Criminology Definition and History

- Learning Styles: Holistic or Global Learning

- What Is a Human's Psychological Makeup for Ergonomics?

- How Psychology Defines and Explains Deviant Behavior

- Information Processing Theory: Definition and Examples

- Media Center

Why do we take mental shortcuts?

What are heuristics.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that can facilitate problem-solving and probability judgments. These strategies are generalizations, or rules-of-thumb, that reduce cognitive load. They can be effective for making immediate judgments, however, they often result in irrational or inaccurate conclusions.

Where this bias occurs

Debias your organization.

Most of us work & live in environments that aren’t optimized for solid decision-making. We work with organizations of all kinds to identify sources of cognitive bias & develop tailored solutions.

We use heuristics in all sorts of situations. One type of heuristic, the availability heuristic , often happens when we’re attempting to judge the frequency with which a certain event occurs. Say, for example, someone asked you whether more tornadoes occur in Kansas or Nebraska. Most of us can easily call to mind an example of a tornado in Kansas: the tornado that whisked Dorothy Gale off to Oz in Frank L. Baum’s The Wizard of Oz . Although it’s fictional, this example comes to us easily. On the other hand, most people have a lot of trouble calling to mind an example of a tornado in Nebraska. This leads us to believe that tornadoes are more common in Kansas than in Nebraska. However, the states actually report similar levels. 1

Individual effects

The thing about heuristics is that they aren’t always wrong. As generalizations, there are many situations where they can yield accurate predictions or result in good decision-making. However, even if the outcome is favorable, it was not achieved through logical means. When we use heuristics, we risk ignoring important information and overvaluing what is less relevant. There’s no guarantee that using heuristics will work out and, even if it does, we’ll be making the decision for the wrong reason. Instead of basing it on reason, our behavior is resulting from a mental shortcut with no real rationale to support it.

Systemic effects

Heuristics become more concerning when applied to politics, academia, and economics. We may all resort to heuristics from time to time, something that is true even of members of important institutions who are tasked with making large, influential decisions. It is necessary for these figures to have a comprehensive understanding of the biases and heuristics that can affect our behavior, so as to promote accuracy on their part.

How it affects product

Heuristics can be useful in product design. Specifically, because heuristics are intuitive to us, they can be applied to create a more user-friendly experience and one that is more valuable to the customer. For example, color psychology is a phenomenon explaining how our experiences with different colors and color families can prime certain emotions or behaviors. Taking advantage of the representativeness heuristic, one could choose to use passive colors (blue or green) or more active colors (red, yellow, orange) depending on the goals of the application or product. 18 For example, if a developer is trying to evoke a feeling of calm for their app that provides guided meditations, they may choose to make the primary colors of the program light blues and greens. Colors like red and orange are more emotionally energizing and may be useful in settings like gyms or crossfit programs.

By integrating heuristics into products we can enhance the user experience. If an application, device, or item includes features that make it feel intuitive, easy to navigate and familiar, customers will be more inclined to continue to use it and recommend it to others. Appealing to those mental shortcuts we can minimize the chances of user error or frustration with a product that is overly complicated.

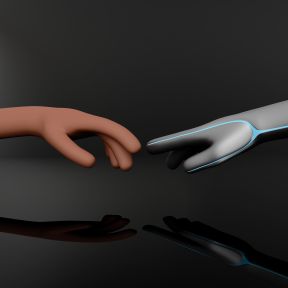

Heuristics and AI

Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools already use the power of heuristics to inform its output. In a nutshell, simple AI tools operate based on a set of built in rules and sometimes heuristics! These are encoded within the system thus aiding in decision-making and the presentation of learning material. Heuristic algorithms can be used to solve advanced computational problems, providing efficient and approximate solutions. Like in humans, the use of heuristics can result in error, and thus must be used with caution. However, machine learning tools and AI can be useful in supporting human decision-making, especially when clouded by emotion, bias or irrationality due to our own susceptibility to heuristics.

Why it happens

In their paper “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” 2 , Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky identified three different kinds of heuristics: availability, representativeness, as well as anchoring and adjustment. Each type of heuristic is used for the purpose of reducing the mental effort needed to make a decision, but they occur in different contexts.

Availability heuristic

The availability heuristic, as defined by Kahneman and Tversky, is the mental shortcut used for making frequency or probability judgments based on “the ease with which instances or occurrences can be brought to mind”. 3 This was touched upon in the previous example, judging the frequency with which tornadoes occur in Kansas relative to Nebraska. 3

The availability heuristic occurs because certain memories come to mind more easily than others. In Kahneman and Tversky’s example participants were asked if more words in the English language start with the letter K or have K as the third letter Interestingly, most participants responded with the former when in actuality, it is the latter that is true. The idea being that it is much more difficult to think of words that have K as the third letter than it is to think of words that start with K. 4 In this case, words that begin with K are more readily available to us than words with the K as the third letter.

Representativeness heuristic

Individuals tend to classify events into categories, which, as illustrated by Kahneman and Tversky, can result in our use of the representativeness heuristic. When we use this heuristic, we categorize events or objects based on how they relate to instances we are already familiar with. Essentially, we have built our own categories, which we use to make predictions about novel situations or people. 5 For example, if someone we meet in one of our university lectures looks and acts like what we believe to be a stereotypical medical student, we may judge the probability that they are studying medicine as highly likely, even without any hard evidence to support that assumption.

The representativeness heuristic is associated with prototype theory. 6 This prominent theory in cognitive science, the prototype theory explains object and identity recognition. It suggests that we categorize different objects and identities in our memory. For example, we may have a category for chairs, a category for fish, a category for books, and so on. Prototype theory posits that we develop prototypical examples for these categories by averaging every example of a given category we encounter. As such, our prototype of a chair should be the most average example of a chair possible, based on our experience with that object. This process aids in object identification because we compare every object we encounter against the prototypes stored in our memory. The more the object resembles the prototype, the more confident we are that it belongs in that category.

Prototype theory may give rise to the representativeness heuristic as it is in situations when a particular object or event is viewed as similar to the prototype stored in our memory, which leads us to classify the object or event into the category represented by that prototype. To go back to the previous example, if your peer closely resembles your prototypical example of a med student, you may place them into that category based on the prototype theory of object and identity recognition. This, however, causes you to commit the representativeness heuristic.

Anchoring and adjustment heuristic

Another heuristic put forth by Kahneman and Tversky in their initial paper is the anchoring and adjustment heuristic. 7 This heuristic describes how, when estimating a certain value, we tend to give an initial value, then adjust it by increasing or decreasing our estimation. However, we often get stuck on that initial value – which is referred to as anchoring – this results in us making insufficient adjustments. Thus, the adjusted value is biased in favor of the initial value we have anchored to.

In an example of the anchoring and adjustment heuristic, Kahneman and Tversky gave participants questions such as “estimate the number of African countries in the United Nations (UN).” A wheel labeled with numbers from 0-100 was spun, and participants were asked to say whether or not the number the wheel landed on was higher or lower than their answer to the question. Then, participants were asked to estimate the number of African countries in the UN, independent from the number they had spun. Regardless, Kahneman and Tversky found that participants tended to anchor onto the random number obtained by spinning the wheel. The results showed that when the number obtained by spinning the wheel was 10, the median estimate given by participants was 25, while, when the number obtained from the wheel was 65, participants’ median estimate was 45.8.

A 2006 study by Epley and Gilovich, “The Anchoring and Adjustment Heuristic: Why the Adjustments are Insufficient” 9 investigated the causes of this heuristic. They illustrated that anchoring often occurs because the new information that we anchor to is more accessible than other information Furthermore, they provided empirical evidence to demonstrate that our adjustments tend to be insufficient because they require significant mental effort, which we are not always motivated to dedicate to the task. They also found that providing incentives for accuracy led participants to make more sufficient adjustments. So, this particular heuristic generally occurs when there is no real incentive to provide an accurate response.

Quick and easy