Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Discussion

- Open Access

- First Online: 25 May 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Marcelo Parreira do Amaral 7

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning ((PSAELL))

11k Accesses

6 Citations

Case Study Research has a long tradition and it has been used in different areas of social sciences to approach research questions that command context sensitiveness and attention to complexity while tapping on multiple sources. Comparative Case Studies have been suggested as providing effective tools to understanding policy and practice along three different axes of social scientific research, namely horizontal (spaces), vertical (scales), and transversal (time). The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements for comparative research. Second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction to the Book and the Comparative Study

Theoretical and Methodological Considerations

Main findings and discussion.

- Case-based research

- Comparative case studies

1 Introduction

Exploring landscapes of lifelong learning in Europe is a daunting task as it involves a great deal of differences across places and spaces; it entails attending to different levels and dimensions of the phenomena at hand, but not least it commands substantial sensibility to cultural and contextual idiosyncrasies. As such, case-based methodologies come to mind as tested methodological approaches to capturing and examining singular configurations such as the local settings in focus in this volume, in which lifelong learning policies for young people are explored in their multidimensional reality. The ensuing question, then, is how to ensure comparability across cases when departing from the assumption that cases are unique. Recent debates in Comparative and International Education (CIE) research are drawn from that offer important insights into the issues involved and provide a heuristic approach to comparative cases studies. Since the cases focused on in the chapters of this book all stem from a common European research project, the comparative case study methodology allows us to at once dive into the specifics and uniqueness of each case while at the same time pay attention to common treads at the national and international (European) levels.

The chapter, first, sketches the methodological basis of case-based research in comparative studies as a point of departure, also highlighting the requirements in comparative research. In what follows, second, the chapter focuses on presenting and discussing recent developments in scholarship to provide insights on how comparative researchers, especially those investigating educational policy and practice in the context of globalization and internationalization, have suggested some critical rethinking of case study research to account more effectively for recent conceptual shifts in the social sciences related to culture, context, space and comparison. In a third section, it presents the approach to comparative case studies adopted in the European research project YOUNG_ADULLLT that has set out to research lifelong learning policies in their embeddedness in regional economies, labour markets and individual life projects of young adults. The chapter is rounded out with some summarizing and concluding remarks.

2 Case-Based Research in Comparative Studies

In the past, comparativists have oftentimes regarded case study research as an alternative to comparative studies proper. At the risk of oversimplification: methodological choices in comparative and international education (CIE) research, from the 1960s onwards, have fallen primarily on either single country (small n) contextualized comparison, or on cross-national (usually large n, variable) decontextualized comparison (see Steiner-Khamsi, 2006a , 2006b , 2009). These two strands of research—notably characterized by Development and Area Studies on the one side and large-scale performance surveys of the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) type, on the other—demarcated their fields by resorting to how context and culture were accounted for and dealt with in the studies they produced. Since the turn of the century, though, comparativists are more comfortable with case study methodology (see Little, 2000 ; Vavrus and Bartlett 2006 , 2009 ; Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 ) and diagnoses of an “identity crisis” of the field due to a mass of single-country studies lacking comparison proper (see Schriewer, 1990 ; Wiseman & Anderson, 2013 ) started dying away. Greater acceptance of and reliance on case-based methodology has been related with research on policy and practice in the context of globalization and coupled with the intention to better account for culture and context, generating scholarship that is critical of power structures, sensitive to alterity and of other ways of knowing.

The phenomena that have been coined as constituting “globalization” and “internationalization” have played, as mentioned, a central role in the critical rethinking of case study research. In researching education under conditions of globalization, scholars placed increasing attention on case-based approaches as opportunities for investigating the contemporary complexity of policy and practice. Further, scholarly debates in the social sciences and the humanities surrounding key concepts such as culture, context, space, and place but also comparison have also contributed to a reconceptualization of case study methodology in CIE. In terms of the requirements for such an investigation, scholarship commands an adequate conceptualization that problematizes the objects of study and that does not take them as “unproblematic”, “assum[ing] a constant shared meaning”; in short, objects of study that are “fixed, abstract and absolute” (Fine, quoted in Dale & Robertson, 2009 , p. 1114). Case study research is thus required to overcome methodological “isms” in their research conceptualization (see Dale & Robertson, 2009 ; Robertson & Dale, 2017 ; see also Lange & Parreira do Amaral, 2018 ). In response to these requirements, the approaches to case study discussed in CIE depart from a conceptualization of the social world as always dynamic, emergent, somewhat in motion, and always contested. This view considers the fact that the social world is culturally produced and is never complete or at a standstill, which goes against an understanding of case as something fixed or natural. Indeed, in the past cases have often been understood almost in naturalistic ways, as if they existed out there, waiting for researchers to “discover” them. Usually, definitions of case study also referred to inquiry that aims at elucidating features of a phenomenon to yield an understanding of why, how and with what consequences something happens. One can easily find examples of cases understood simply as sites to observe/measure variables—in a nomothetic cast—or examples, where cases are viewed as specific and unique instances that can be examined in the idiographic paradigm. In contrast, rather than taking cases as pre-existing entities that are defined and selected as cases, recent case-oriented research has argued for a more emergent approach which recognizes that boundaries between phenomenon and context are often difficult to establish or overlap. For this reason, researchers are incited to see this as an exercise of “casing”, that is, of case construction. In this sense, cases here are seen as complex systems (Ragin & Becker, 1992 ) and attention is devoted to the relationships between the parts and the whole, pointing to the relevance of configurations and constellations within as well as across cases in the explanation of complex and contingent phenomena. This is particularly relevant for multi-case, comparative research since the constitution of the phenomena that will be defined, as cases will differ. Setting boundaries will thus also require researchers to account for spatial, scalar (i.e., level or levels with which a case is related) and temporal aspects.

Further, case-based research is also required to account for multiple contexts while not taking them for granted. One of the key theoretical and methodological consequences of globalization for CIE is that it required us to recognize that it alters the nature and significance of what counts as contexts (see Parreira do Amaral, 2014 ). According to Dale ( 2015 ), designating a process, or a type of event, or a particular organization, as a context, entails bestowing a particular significance on them, as processes, events, and so on that are capable of affecting other processes and events. The key point is that rather than being so intrinsically, or naturally, contexts are constructed as “contexts”. In comparative research, contexts have been typically seen as the place (or the variables) that enable us to explain why what happens in one case is different from what happens another case; what counts as context then is seen as having the same effect everywhere, although the forms it takes vary substantially (see Dale, 2015 ). In more general terms, recent case study approaches aim at accounting for the increasing complexity of the contexts in which they are embedded, which, in turn, is related to the increasing impact of globalization as the “context of contexts” (Dale, 2015 , p. 181f; see also Carter & Sealey, 2013 ; Mjoset, 2013 ). It also aims at accounting for overlapping contexts. Here it is important to note that contexts are not only to be seen in spatio-geographical terms (i.e., local, regional, national, international), but contexts may also be provided by different institutional and/or discursive contexts that create varying opportunity structures (Dale & Parreira do Amaral, 2015 ; see also Chap. 2 in this volume). What one can call temporal contexts also plays an important role, for what happens in the case unfolds as embedded not only in historical time, but may be related to different temporalities (see the concept of “timespace” as discussed by Lingard & Thompson, 2016 ) and thus are influenced by path dependence or by specific moments of crisis (Rhinard, 2019 ; see also McLeod, 2016 ). Moreover, in CIE research, the social-cultural production of the world is influenced by developments throughout the globe that take place at various places and on several scales, which in turn influence each other, but in the end, become locally relevant in different facets. As Bartlett and Vavrus write, “context is not a primordial or autonomous place; it is constituted by social interactions, political processes, and economic developments across scales and times.” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 14). Indeed, in this sense, “context is not a container for activity, it is the activity” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 12, emphasis in orig.).

Also, dealing with the complexity of education policy and practice requires us to transcend the dichotomy of idiographic versus nomothetic approaches to causation. Here, it can be argued that case studies allow us to grasp and research the complexity of the world, thus offering conceptual and methodological tools to explore how phenomena viewed as cases “depend on all of the whole, the parts, the interactions among parts and whole, and the interactions of any system with other complex systems among which it is nested and with which it intersects” (Byrne, 2013 , p. 2). The understanding of causation that undergirds recent developments in case-based research aims at generalization, yet it resists ambitions to establishing universal laws in social scientific research. Focus is placed on processes while tracking the relevant factors, actors and features that help explain the “how” and the “why” questions (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 38ff), and on “causal mechanisms”, as varying explanations of outcomes within and across cases, always contingent on interaction with other variables and dependent contexts (see Byrne, 2013 ; Ragin, 2000 ). In short, the nature of causation underlying the recent case study approaches in CIE is configurational and not foundational.

This is also in line with how CIE research regards education practice, research, and policy as a socio-cultural practice. And it refers to the production of social and cultural worlds through “social actors, with diverse motives, intentions, and levels of influence, [who] work in tandem with and/or in response to social forces” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 1). From this perspective, educational phenomena, such as in policymaking, are seen as a “deeply political process of cultural production engaged in and shaped by social actors in disparate locations who exert incongruent amounts of influence over the design, implementation, and evaluation of policy” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 1f). Culture here is understood in non-static and complex ways that reinforce the “importance of examining processes of sense-making as they develop over time, in distinct settings, in relation to systems of power and inequality, and in increasingly interconnected conversation with actors who do not sit physically within the circle drawn around the traditional case” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 11, emphasis in orig.).

In sum, the approaches to case study put forward in CIE provide conceptual and methodological tools that allow for an analysis of education in the global context throughout scale, space, and time, which is always regarded as complexly integrated and never as isolated or independent. The following subsection discusses Comparative Case Studies (CCS) as suggested in recent comparative scholarship, which aims at attending to the methodological requirements discussed above by integrating horizontal, vertical, and transversal dimensions of comparison.

2.1 Comparative Case Studies: Horizontal, Vertical and Transversal Dimensions

Building up on their previous work on vertical case studies (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 ; Vavrus & Bartlett, 2006 , 2009 ), Frances Vavrus and Lesley Bartlett have proposed a comparative approach to case study research that aims at meeting the requirements of culture and context sensitive research as discussed in this special issue.

As a research approach, CCS offers two theoretical-methodological lenses to research education as a socio-cultural practice. These lenses represent different views on the research object and account for the complexity of education practice, policy, and research in globalized contexts. The first lens is “context-sensitive”, which focuses on how social practices and interactions constitute and produce social contexts. As quoted above, from the perspective of a socio-cultural practice, “context is not a container for activity, it is the activity” (Vavrus and Bartlett 2017: 12, emphasis in orig.). The settings that influence and condition educational phenomena are culturally produced in different and sometimes overlapping (spatial, institutional, discursive, temporal) contexts as just mentioned. The second CCS lens is “culture-sensitive” and focuses on how socio-cultural practices produce social structures. As such, culture is a process that is emergent, dynamic, and constitutive of meaning-making as well as social structuration.

The CCS approach aims at studying educational phenomena throughout scale, time, and space by providing three axes for a “studying through” of the phenomena in question. As stated by Lesley Bartlett and Frances Vavrus with reference to comparative analyses of global education policy:

the horizontal axis compares how similar policies unfold in distinct locations that are socially produced […] and ‘complexly connected’ […]. The vertical axis insists on simultaneous attention to and across scales […]. The transversal comparison historically situates the processes or relations under consideration (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 : 3, emphasis in orig.).

These three axes allow for a methodological conceptualization of “policy formation and appropriation across micro-, meso-, and macro levels” by not theorizing them as distinct or unrelated (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 4). In following Latour, they state:

the macro is neither “above” nor “below” the intersections but added to them as another of their connections’ […]. In CCS research, one would pay close attention to how actions at different scales mutually influence one another (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 13f, emphasis in orig.)

Thus, these three axes contain

processes across space and time; and [the CCS as a research design] constantly compares what is happening in one locale with what has happened in other places and historical moments. These forms of comparison are what we call horizontal, vertical, and transversal comparisons (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 11, emphasis in orig.)

In terms of the three axes along with comparison is organized, the authors state that horizontal comparison commands attention to how historical and contemporary processes have variously influenced the “cases”, which might be constructed by focusing “people, groups of people, sites, institutions, social movements, partnerships, etc.” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 53) Horizontal comparisons eschew pressing categories resultant from one case others, which implies including multiple cases at the same scale in a comparative case study, while at the same time attending to “valuable contextual information” about each of them. Horizontal comparisons use units of analysis that are homologous, that is, equivalent in terms of shape, function, or institutional/organizational nature (for instance, schools, ministries, countries, etc.) ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 53f). Similarly, comparative case studies may also entail tracing a phenomenon across sites, as in multi-sited ethnography (see Coleman & von Hellermann, 2012 ; Marcus, 1995 ).

Vertical comparison, in turn, does not simply imply the comparison of levels; rather it involves analysing networks and their interrelationships at different scales. For instance, in the study of policymaking in a specific case, vertical comparison would consider how actors at different scales variably respond to a policy issued at another level—be it inter−/supranational or at the subnational level. CCS assumes that their different appropriation of policy as discourse and as practice is often due to different histories of racial, ethnic, or gender politics in their communities that appropriately complicate the notion of a single cultural group (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 73f). Establishing what counts as context in such a study would be done “by tracing the formation and appropriation of a policy” at different scales; and “by tracing the processes by which actors and actants come into relationship with one another and form non-permanent assemblages aimed at producing, implementing, resisting, and appropriating policy to achieve particular aims” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 76). A further element here is that, in this way, one may counter the common problem that comparison of cases (oftentimes countries) usually overemphasizes boundaries and treats them as separated or as self-sustaining containers, when, in reality, actors and institutions at other levels/scales significantly impact policymaking (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 ).

In terms of the transversal axis of comparison, Bartlett and Vavrus argue that the social phenomena of interest in a case study have to be seen in light of their historical development (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 93), since these “historical roots” impacted on them and “continues to reverberate into the present, affecting economic relations and social issues such as migration and educational opportunities.” As such, understanding what goes on in a case requires to “understand how it came to be in the first place.” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 93) argue:

history offers an extensive fount of evidence regarding how social institutions function and how social relations are similar and different around the world. Historical analysis provides an essential opportunity to contrast how things have changed over time and to consider what has remained the same in one locale or across much broader scales. Such historical comparison reveals important insights about the flexible cultural, social, political, and economic systems humans have developed and sustained over time (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 94).

Further, time and space are intimately related and studying the historical development of the social phenomena of interest in a case study “allows us to assess evidence and conflicting interpretations of a phenomenon,” but also to interrogate our own assumptions about them in contemporary times (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 ), thus analytically sharpening our historical analyses.

As argued by the authors, researching the global dimension of education practice, research or policy aims at a “studying through” of phenomena horizontally, vertically, and transversally. That is, comparative case study builds on an emergent research design and on a strong process orientation that aims at tracing not only “what”, but also “why” and “how” phenomena emerge and evolve. This approach entails “an open-ended, inductive approach to discover what […] meanings and influences are and how they are involved in these events and activities—an inherently processual orientation” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 7, emphasis in orig.).

The emergent research design and process orientation of the CCS relativizes a priori, somewhat static notions of case construction in CIE and emphasizes the idea of a processual “casing”. The process of casing put forward by CCS has to be understood as a dynamic and open-ended embedding of “cased” research phenomena within moments of scale, space, and time that produce varying sets of conditions or configurations.

In terms of comparison, the primary logic is well in line with more sophisticated approaches to comparison that not simply establish relationships between observable facts or pre-existing cases; rather, the comparative logic aims at establishing “relations between sets of relationships”, as argued by Jürgen Schriewer:

[the] specific method of science dissociates comparison from its quasi-natural union with resemblances; the interest in identifying similarities shifts from the level of factual contents to the level of generalizable relationships. […] One of the primary ways of extending their scope, or examining their explanatory power, is the controlled introduction of varying sets of conditions. The logic of relating relationships, which distinguishes the scientific method of comparison, comes close to meeting these requirements by systematically exploring and analysing sociocultural differences with respect to scrutinizing the credibility of theories, models or constructs (Schriewer, 1990 , p. 36).

The notion of establishing relations between sets of relationships allows to treat cases not as homogeneous (thus avoiding a universalizing notion of comparison); it establishes comparability not along similarity but based on conceptual, functional and/or theoretical equivalences and focuses on reconstructing ‘varying sets of conditions’ that are seen as relevant in social scientific explanation and theorizing, and to which then comparative case studies may contribute.

The following section aims presents the adaptation and application of a comparative case study approach in the YOUNG_ADULLLT research project.

3 Exploring Landscapes of Lifelong Learning through Case Studies

This section illustrates the usage of comparative case studies by drawing from research conducted in a European research project upon which the chapters in this volume are based. The project departed from the observation that most current European lifelong learning (LLL) policies have been designed to create economic growth and, at the same time, guarantee social inclusion and argued that, while these objectives are complementary, they are, however, not linearly nor causally related and, due to distinct orientations, different objectives, and temporal horizons, conflicts and ambiguities may arise. The project was designed as a mixed-method comparative study and aimed at results at the national, regional, and local levels, focusing in particular on policies targeting young adults in situations of near social exclusion. Using a multi-level approach with qualitative and quantitative methods, the project conducted, amongst others, local/regional 18 case studies of lifelong learning policies through a multi-method and multi-level design (see Parreira do Amaral et al., 2020 for more information). The localisation of the cases in their contexts was carried out by identifying relevant areas in terms of spatial differentiation and organisation of social and economic relations. The so defined “functional regions” allowed focus on territorial units which played a central role within their areas, not necessarily overlapping with geographical and/or administrative borders. Footnote 1

Two main objectives guided the research: first, to analyse policies and programmes at the regional and local level by identifying policymaking networks that included all social actors involved in shaping, formulating, and implementing LLL policies for young adults; second, to recognize strengths and weaknesses (overlapping, fragmented or unfocused policies and projects), thus identifying different patterns of LLL policymaking at regional level, and investigating their integration with the labour market, education and other social policies. The European research project focused predominantly on the differences between the existing lifelong learning policies in terms of their objectives and orientations and questioned their impact on young adults’ life courses, especially those young adults who find themselves in vulnerable positions. What concerned the researchers primarily was the interaction between local institutional settings, education, labour markets, policymaking landscapes, and informal initiatives that together nurture the processes of lifelong learning. They argued that it is by inquiring into the interplay of these components that the regional and local contexts of lifelong learning policymaking can be better assessed and understood. In this regard, the multi-layered approach covered a wide range of actors and levels and aimed at securing compatibility throughout the different phases and parts of the research.

The multi-level approach adopted aimed at incorporating the different levels from transnational to regional/local to individual, that is, the different places, spaces, and levels with which policies are related. The multi-method design was used to bring together the results from the quantitative, qualitative and policy/document analysis (for a discussion: Parreira do Amaral, 2020 ).

Studying the complex relationships between lifelong learning (LLL) policymaking on the one hand, and young adults’ life courses on the other, requires a carefully established research approach. This task becomes even more challenging in the light of the diverse European countries and their still more complex local and regional structures and institutions. One possible way of designing a research framework able to deal with these circumstances clearly and coherently is to adopt a multi-level or multi-layered approach. This approach recognises multiple levels and patterns of analysis and enables researchers to structure the workflow according to various perspectives. It was this multi-layered approach that the research consortium of YOUNG_ADULLLT adopted and applied in its attempts to better understand policies supporting young people in their life course.

3.1 Constructing Case Studies

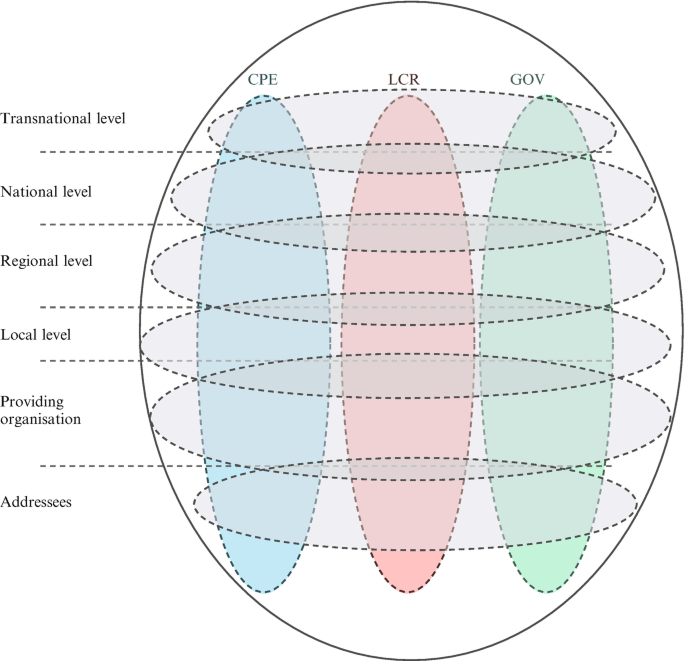

In constructing case studies, the project did not apply an instrumental approach focused on the assessment of “what worked (or not)?” Rather, consistently with Bartlett and Vavrus’s proposal (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 ), the project decided to “understand policy as a deeply political process of cultural production engaged in and shaped by social actors in disparate locations who exert incongruent amounts of influence over the design, implementation, and evaluation of policy” ( Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017 , p. 1f). This was done in order to enhance the interactive and relational dimension among actors and levels, as well as their embeddedness in local infra-structures (education, labour, social/youth policies) according to project’s three theoretical perspectives. The analyses of the information and data integrated by our case study approach aimed at a cross-reading of the relations among the macro socio-economic dimensions, structural arrangements, governance patterns, addressee biographies and mainstream discourses that underlie the process of design and implementation of the LLL policies selected as case study. The subjective dimensions of agency and sense-making animated these analyses, and the multi-level approach contextualized them from the local to the transnational levels. Figure 3.1 below represents the analytical approach to the research material gathered in constructing the case studies. Specifically, it shows the different levels, from the transnational level down to the addressees.

Multi-level and multi-method approach to case studies in YOUNG_ADULLLT. Source: Palumbo et al., 2019

The project partners aimed at a cross-dimensional construction of the case studies, and this implied the possibility of different entry points, for instance by moving the analytical perspective top-down or bottom-up, as well as shifting from left to right of the matrix and vice versa. Considering the “horizontal movement”, the multidimensional approach has enabled taking into consideration the mutual influence and relations among the institutional, individual, and structural dimensions (which in the project corresponded to the theoretical frames of CPE, LCR, and GOV). In addition, the “vertical movement” from the transnational to the individual level and vice versa was meant to carefully carry out a “study of flows of influence, ideas, and actions through these levels” (Bartlett and Vavrus 2017 , p. 11), emphasizing the correspondences/divergences among the perspectives of different actors at different levels. The transversal dimension, that is, the historical process, focused on the period after the financial crisis of 2007/2008 as it has impacted differently on the social and economic situations of young people, often resulting in stern conditions and higher competition in education and labour markets, which also called for a reassessment of existing policies targeting young adults in the countries studied.

Concerning the analyses, a further step included the translation of the conceptual model illustrated in Fig. 3.1 above into a heuristic table used to systematically organize the empirical data collected and guide the analyses cases constructed as multi-level and multidimensional phenomena, allowing for the establishment of interlinkages and relationships. By this approach, the analysis had the possibility of grasping the various levels at which LLL policies are negotiated and displaying the interplay of macro-structures, regional environments and institutions/organizations as well as individual expectations. Table 3.1 illustrates the operationalization of the data matrix that guided the work.

In order to ensure the presentability and intelligibility of the results, Footnote 2 a narrative approach to case studies analysis was chosen whose main task was one of “storytelling” aimed at highlighting what made each case unique and what difference it makes for LLL policymaking and to young people’s life courses. A crucial element of this entails establishing relations “between sets of relationships”, as argued above.

LLL policies were selected as starting points from which the cases themselves could be constructed and of which different stories could be developed. That stories can be told differently does not mean that they are arbitrary, rather this refers to different ways of accounting for the embedding of the specific case to its context, namely the “diverging policy frameworks, patterns of policymaking, networks of implementation, political discourses and macro-structural conditions at local level” (see Palumbo et al., 2020 , p. 220). Moreover, developing different narratives aimed at representing the various voices of the actors involved in the process—from policy-design and appropriation through to implementation—and making the different stakeholders’ and addressees’ opinions visible, creating thus intelligible narratives for the cases (see Palumbo et al., 2020 ). Analysing each case started from an entry point selected, from which a story was told. Mainly, two entry points were used: on the one hand, departing from the transversal dimension of the case and which focused on the evolution of a policy in terms of its main objectives, target groups, governance patterns and so on in order to highlight the intended and unintended effects of the “current version” of the policy within its context and according to the opinions of the actors interviewed. On the other hand, biographies were selected as starting points in an attempt to contextualize the life stories within the biographical constellations in which the young people came across the measure, the access procedures, and how their life trajectories continued in and possibly after their participation in the policy (see Palumbo et al., 2020 for examples of these narrative strategies).

4 Concluding Remarks

This chapter presented and discussed the methodological basis and requirements of conducting case studies in comparative research, such as those presented in the subsequent chapters of this volume. The Comparative Case Study approach suggested in the previous discussion offers productive and innovative ways to account sensitively to culture and contexts; it provides a useful heuristic that deals effectively with issues related to case construction, namely an emergent and dynamic approach to casing, instead of simply assuming “bounded”, pre-defined cases as the object of research; they also offer a helpful procedural, configurational approach to “causality”; and, not least, a resourceful approach to comparison that allows researchers to respect the uniqueness and integrity of each case while at the same time yielding insights and results that transcend the idiosyncrasy of the single case. In sum, CCS offers a sound approach to CIE research that is culture and context sensitive.

For a discussion of the concept of functional region, see Parreira do Amaral et al., 2020 .

This analytical move is in line with recent developments that aim at accounting for a cultural turn (Jameson, 1998 ) or ideational turn (Béland & Cox, 2011 ) in policy analysis methodology, called interpretive policy analysis (see Münch, 2016 ).

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Rethinking case study research. A comparative approach . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Béland, D., & Cox, R. H. (Eds.). (2011). Ideas and politics in social science research . Oxford University Press.

Byrne, D. (2013). Introduction. Case-based methods: Why we need them; what they are; how to do them. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 1–13). SAGE.

Carter, B., & Sealey, A. (2013). Reflexivity, realism and the process of casing. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 69–83). SAGE.

Coleman, S., & von Hellermann, P. (Eds.). (2012). Multi-sited ethnography: Problems and possibilities in the translocation of research methods . Routledge.

Dale, R., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2015). Discursive and institutional opportunity structures in the governance of educational trajectories. In M. P. do Amaral, R. Dale, & P. Loncle (Eds.), Shaping the futures of young Europeans: Education governance in eight European countries (pp. 23–42). Symposium Books.

Dale, R., & Robertson, S. (2009). Beyond methodological ʻismsʼ in comparative education in an era of globalisation. In R. Cowen & A. M. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (pp. 1113–1127). Springer Netherlands.

Chapter Google Scholar

Dale, R. (2015). Globalisierung in der Vergleichenden Erziehungswissenschaft re-visited: Die Relevanz des Kontexts des Kontexts. In M. P. do Amaral & S.K. Amos (Hrsg.) (Eds.), Internationale und Vergleichende Erziehungswissenschaft. Geschichte, Theorie, Methode und Forschungsfelder (pp. 171–187). Waxmann.

Jameson, F. (1998). The cultural turn. Selected writings on the postmodern. 1983–1998 . Verso.

Lange, S., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2018). Leistungen und Grenzen internationaler und vergleichender Forschung— Regulative Ideen für die methodologische Reflexion? Tertium Comparationis, 24 (1), 5–31.

Lingard, B., & Thompson, G. (2016). Doing time in the sociology of education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38 (1), 1–12.

Article Google Scholar

Little, A. (2000). Development studies and comparative education: Context, content, comparison and contributors. Comparative Education, 36 (3), 279–296.

Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24 , 95–117.

McLeod, J. (2016). Marking time, making methods: Temporality and untimely dilemmas in the sociology of youth and educational change. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 38 (1), 13–25.

Mjoset, L. (2013). The Contextualist approach to social science methodology. In D. Byrne & C. C. Ragin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of case-based methods (pp. 39–68). SAGE.

Münch, S. (2016). Interpretative Policy-Analyse. Eine Einführung . Springer VS.

Book Google Scholar

Palumbo, M., Benasso, S., Pandolfini, V., Verlage, T., & Walther, A. (2019). Work Package 7 Cross-case and cross-national Report. YOUNG_ADULLLT Working Paper. http://www.young-adulllt.eu/publications/working-paper/index.php . Accessed 31 Aug 2021.

Palumbo, M., Benasso, S., & Parreira do Amaral, M. (2020). Telling the story. Exploring lifelong learning policies for young adults through a narrative approach. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe. Navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 217–239). Policy Press.

Parreira do Amaral, M. (2014). Globalisierung im Fokus vergleichender Forschung. In C. Freitag (Ed.), Methoden des Vergleichs. Komparatistische Methodologie und Forschungsmethodik in interdisziplinärer Perspektive (pp. 117–138). Budrich.

Parreira do Amaral, M. (2020). Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe: A conceptual and methodological discussion. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe. Navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 3–20). Policy Press.

Parreira do Amaral, M., Lowden, K., Pandolfini, V., & Schöneck, N. (2020). Coordinated policy-making in lifelong learning: Functional regions as dynamic units. In M. P. do Amaral, S. Kovacheva, & X. Rambla (Eds.), Lifelong learning policies for young adults in Europe navigating between knowledge and economy (pp. 21–42). Policy Press.

Ragin, C. C., & Becker, H. (1992). What is a case? Cambridge UP.

Ragin, C. C. (2000). Fuzzy set social science . Chicago UP.

Rhinard, M. (2019). The Crisisification of policy-making in the European Union. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57 (3), 616–633.

Robertson, S., & Dale, R. (2017). Comparing policies in a globalizing world. Methodological reflections. Educação & Realidade, 42 (3), 859–876.

Schriewer, J. (1990). The method of comparison and the need for externalization: Methodological criteria and sociological concepts. In J. Schriewer & B. Holmes (Eds.), Theories and methods in comparative education (pp. 25–83). Lang.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2006a). The development turn in comparative and international education. European Education: Issues and Studies, 38 (3), 19–47.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2006b). U.S. social and educational research during the cold war: An interview with Harold J. Noah. European Education: Issues and Studies, 38 (3), 9–18.

Vavrus, F., & Bartlett, L. (2006). Comparatively knowing: Making a case for vertical case study. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 8 (2), 95–103.

Vavrus, F., & Bartlett, L. (Eds.). (2009). Critical approaches to comparative education: Vertical case studies from Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas . Palgrave Macmillan.

Wiseman, A. W., & Anderson, E. (2013). Introduction to part 3: Conceptual and methodological developments. In A. W. Wiseman & E. Anderson (Eds.), Annual review of comparative and international education 2013 (international perspectives on education and society, Vol. 20) (pp. 85–90). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Education, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

Marcelo Parreira do Amaral

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marcelo Parreira do Amaral .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Sciences, University of Genoa, Genova, Italy

Sebastiano Benasso

Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Dejana Bouillet

Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Tiago Neves

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

do Amaral, M.P. (2022). Comparative Case Studies: Methodological Discussion. In: Benasso, S., Bouillet, D., Neves, T., Parreira do Amaral, M. (eds) Landscapes of Lifelong Learning Policies across Europe. Palgrave Studies in Adult Education and Lifelong Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96454-2_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96454-2_3

Published : 25 May 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-96453-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-96454-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Comparative Historical Analysis

- Published: September 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter introduces the reader to comparative historical analysis (CHA), one of the oldest methods in the social science repertoire. CHA is characterized by its emphasis on historically contextualized comparisons explicitly aimed at producing causal arguments about the macro-sociological phenomena. After a theoretical overview that discusses the method’s nature, logic, and central concepts, the chapter turns its attention to practical matters. Thus, rather than an extended scientific discussion of what CHA is, the chapter seeks to encourage interested students by providing them with a series of tools and techniques that can be used when doing comparative historical research on social movements and revolutions. More specifically, the chapter offers a five-step approach: research design and puzzle formulation; data identification; the use of data; data analysis; and the writing process. A discussion on the use of technology in the research process is present throughout the practical part of the chapter.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

QUALITATIVE METHODS

15 Comparative Historical Analysis

Emanuele Ferragina

Comparative historical analysis combines two major methodological tools of social science, comparison (the study of similarities and differences across cases) and history (the analysis of processes of change in their temporal dimension), to help explain large scale outcomes on a variety of topics. It is particularly useful to account for the definition of public policies (policy framing and policy change).

Keywords: Mixed methods, qualitative methods, historical analysis, similarities, differences, history, macro, comparison, critical junctures, path dependency

I. What does this approach consist of?

Comparative historical analysis (CHA) is more an approach than a method, and it is rooted in a long history from old seminal works, e.g. De la Démocratie en Amérique (Tocqueville 1960) and The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (Weber 2001) to modern classics, e.g. The Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Moore 1966) and States and Social Revolutions (Skocpol 1979). The historical approach in social sciences offers explanations of large-scale outcomes on a wide range of topics, such as revolutions, the advent of democratic or authoritarian rule, path dependent institutional processes, policy continuity and change in various domains. This approach has several distinctive characteristics that have fostered its extensive use in social science research and public policy.

CHA explores similarities and differences across different cases – recalling John Stuart Mill’s method of agreement and difference – with the aim to unveil causal mechanisms that determine specific outcomes (see separate chapter on case studies ). Processes of change and their temporal dimension are at the core of sociology and political science, and for this reason CHA helped the identification of the origin of specific reforms, or the point of departure for significant institutional change. The cases analysed are often nation-states, but other entities (such as regions, social movements and organisations) have also been scrutinised (for an example of regional analysis, see Ferragina 2012; 2013). This approach attributes a big role to theory, and a very interesting debate has taken place on the American Journal of Sociology, with a symposium comparing the place assigned to theory in historical sociology and rational choice theory: “we’re no angels: realism, rational choice, and relationality in social science” (see the contributions to this debate of Somers 1998; Kiser and Hechter 1998; Goldstone 1998; Calhoun 1998). The debate contrasted the use of these different perspectives, highlighting that CHA helps to test and generate theory through a macro-configurational, case-based and temporally-oriented approach.

The macro component concerns large-scale outcomes, i.e. state building, democratic transitions, societal patterns of inequality, war and peace. Researchers focus on large-scale causal factors, including both political-economic structures (e.g. colonialism) and complex organisational institutional arrangements (e.g. social policy regimes). This macro approach can also explain micro-level events and processes that should (or should not) be present within particular cases if the macro theory is correct. The configurational component refers to the way in which researchers consider how multiple factors combine to form coherent causal packages. One for example cannot study revolutions without analysing how various events and underlying processes constitute these social phenomena. Even when CHA scholars are interested in studying the effects of a specific variable they care a lot about the context and other potential causes.

Differently from other techniques commonly used in social science, CHA does not shy away from complex questions for which data are not readily available. One of the most regrettable trends in social sciences is the selection of questions on the basis of available data. As in the Nietzschean metaphor, it is as if researchers are like drunk people who search their lost keys only under the lamppost. For this reason, CHA focuses on real world puzzles and uses mechanisms-based explanations, following questions of this kind: why do cases that are similar on many key dimensions exhibit different outcomes on a dependent variable of interest? Or alternatively, why do seemingly disparate cases all have the same outcome? Moreover, real world puzzles may also be formulated when particular cases do not conform to expectations from existing theory or large-N research. CHA places emphasis on developing a deep understanding of the cases to adjudicate competing hypotheses.