Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

The patient has been treated for hypertension for 10 years, currently with amlodipine 10 mg by mouth daily. She was once told that her cholesterol value was "borderline high" but does not know the value.

She denies symptoms of diabetes, chest pain, shortness of breath, heart disease, stroke, or circulatory problems of the lower extremities.

She estimates her current weight at 165 lbs (75 kg). She thinks she weighed 120 lbs (54 kg) at age 21 years but gained weight with each of her three pregnancies and did not return to her nonpregnant weight after each delivery. She weighed 155 lbs one year ago but gained weight following retirement from her job as an elementary school teacher. No family medical history is available because she was adopted. She does not eat breakfast, has a modest lunch, and consumes most of her calories at supper and in the evening.

On examination, blood pressure is 140/85 mmHg supine and 140/90 mmHg upright with a regular heart rate of 76 beats/minute. She weighs 169 lbs, with a body mass index (BMI) of 30.9 kg/m 2 . Fundoscopic examination reveals no evidence of retinopathy. Vibratory sensation is absent at the great toes, reduced at the medial malleoli, and normal at the tibial tubercles. Light touch sensation is reduced in the feet but intact more proximally. Knee jerks are 2+ bilaterally, but the ankle jerks are absent. The examination is otherwise within normal limits.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

On March 6th, 2019, Maria Fernandez, a 19-year-old female, presented to the Emergency Department with complaints of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and lethargy. She reveals a recent diagnosis of type 1 diabetes but admits to noncompliance with treatment. At the time of admission, Maria’s vital signs were as follows: BP 87/50, HR 118, RR 28, O2 95% on room air, diffuse abdominal pain at a level of 5, on a verbal numeric 1-10 scale, with non-radiating pain beginning that morning. She was A&O x3, oriented to self, place, and situation, but sluggish. Upon assessment it is revealed that she is experiencing blurry vision, Kussmaul respirations, dry, flushed skin, poor skin turgor, weakness, and a fruity breath smell. Labs were drawn. During the first hour of admission, Maria requested water four times and urinated three times.

Code status: Full code

Medical hx : Type 1 Diabetes

Insurance : None

Allergies : NKA

Significant Lab Values

- Blood glucose 388

- ABGs: pH 7.25, Bicarb 12 mEq/L, paCO2 30 mm Hg, anion gap 20 mEq/L, paO2 94%

- Urinalysis: Ketones and acetone present, BUN 25 mL/dL, Cr 2.1 ml/dL

- Chemistry: sodium 111 mEq/L, potassium 5.5 mEq/L, chloride 90 mEq/L, phosphorus 2.5 mg/dL, Magnesium 2.0 mg/dL

- CBC: WBC 13,000 mcL, RBC 4.7 mcL, Hgb 12.6 g/dL , Hct 37% (Wolters Kluwer, 2018).

Diagnosis: Diabetes Ketoacidosis

- Oxygen administration by nasal cannula on 2L and airway management

- Establish IV access

- IV fluid administration with 0.9% NS; prepare to titrate to 0.45% normal saline as needed

- Monitor blood glucose levels

- Administer 0.1-0.15 unit/kg IV bolus of regular insulin

- IV drip infusion at 0.1 unit/kg/hr of regular insulin to hyperglycemia after bolus,

- Addition of Dextrose to 0.9% NS as glucose levels decreases to 250 mg/dL

- Monitor potassium levels

- Potassium replacement via IV when the potassium level is 5.0 mg/dL or less and urine output is adequate

- Assess for signs of hypokalemia or hyperkalemia

- Monitor vital signs and cardiac rhythm

- Q1-2hr fingerstick blood glucose checks initially, then q4-6hr once stabilized

- Monitor blood pH, I&O

- Assess level of consciousness; provide seizure and safety precautions (Henry et al., 2016)

- Notify MD of any critical changes

Maria Fernandez was then transferred to the ICU unit for close observation, maintenance of IV insulin drip, cardiac monitoring, fluid resuscitation, and correction for metabolic acidosis.

Upon discharge, Maria was reeducated on Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus through the use of preferred learning materials.

- What is the priority assessment data that supports DKA diagnosis?

- What education strategies would you consider implementing to improve treatment adherence after discharge?

- What considerations, services, or resources would you anticipate to be offered by case management or social services?

Henry, N.J., McMichael, M., Johnson, J., DiStasi, A., Ball, B.S., Holman, H.C., Elkins, C.B., Janowski, M.J., Hertel, R.A., Barlow, M.S., Leehy, P., & Lemon, T. (2016). RN adult medical surgical nursing: Review module (10 th ed.). Leawood, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute.

Wolters Kluwer. (2018). Lippincott Nursing Advisor (Version 4.1.0) [Mobile application software]. Retrieved from http://itunes.apple.com

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley Open Access Collection

- PMC10087720

The experiences and support needs of students with diabetes at university: An integrative literature review

Virginia hagger.

1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Deakin University, Burwood Victoria, Australia

2 The Centre for Quality and Patient Safety Research in the Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University, Geelong Victoria, Australia

Amelia J. Lake

3 The Australian Centre for Behavioural Research in Diabetes, Diabetes Victoria, Melbourne Victoria, Australia

4 School of Psychology, Deakin University, Geelong Victoria, Australia

Tarveen Singh

Peter s. hamblin.

5 Western Health, St. Albans Victoria, Australia

6 Department of Medicine, Western Health, University of Melbourne, St. Albans Victoria, Australia

Bodil Rasmussen

7 Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen Denmark

8 Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark and Steno Diabetes Centre, Odense Denmark

Associated Data

Commencing university presents particular challenges for young adults with diabetes. This integrative literature review aimed to synthesise the research exploring the experiences and support needs of university students with diabetes.

Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo and EMBASE databases were searched for quantitative and qualitative studies, among undergraduate and postgraduate students with type 1 or type 2 diabetes conducted in the university setting. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts and full‐text articles. Data were analysed thematically and synthesised narratively utilising the ecological model as a framework for interpreting findings and making recommendations.

We identified 25 eligible papers (20 studies) utilising various methods: individual interview, focus group, survey, online forum. Four themes were identified: barriers to self‐care (e.g. lack of structure and routine); living with diabetes as a student; identity, stigma and disclosure; and strategies for managing diabetes at university. Students in the early years at university, recently diagnosed or moved away from home, reported more self‐care difficulties, yet few accessed university support services. Risky alcohol‐related behaviours, perceived stigma and reluctance to disclose diabetes inhibited optimal diabetes management.

Despite the heterogeneity of studies, consistent themes related to diabetes self‐care difficulties and risky behaviours were reported by young adults with diabetes transitioning to university life. No effective interventions to support students with diabetes were identified in this setting. Multilevel approaches to support students to balance the competing demands of study and diabetes self‐care are needed, particularly in the early years of university life.

- Young adulthood is a period of multiple life transitions.

- There is a lack of information about the needs of students with diabetes at university.

- This integrated review identified consistent themes in the literature. Students perceive more difficulty managing diabetes at university and may engage in risky behaviours to avoid appearing different to their peers. Multilevel intervention is needed to support students to adapt to university life.

1. INTRODUCTION

Young adulthood represents a challenging life stage for people with diabetes. Young adults are dealing with multiple transitions simultaneously, including developmental changes, increasing independence, transition to adult healthcare and university, or work, and for those who are newly diagnosed the transition from wellness to chronic illness. 1

Around 40% of school leavers in the United Kingdom and Australia start university, and others commence undergraduate or postgraduate study later. 2 , 3 The transition to university may involve independence from parents, leaving home, new relationships, experimenting with drugs and alcohol. 4 , 5 , 6 Students must learn to navigate classes and new routines, and find strategies to manage exercise, food and social activities, and for school leavers with diabetes, there is an added complexity to avoid and manage hypoglycaemia in a different environment. 1

For some young adults, managing diabetes is perceived to be harder at university than it was at school. 4 , 7 In a study from the United Kingdom, 26% of students with type 1 diabetes self‐reported a diabetes‐related hospital admission while at university, including 16% admitted for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and 10% experienced severe hypoglycaemia requiring assistance. 4

Living with diabetes also impacts the social aspects of university life. A survey among first‐year college students in the United States found those with a chronic illness reported greater feelings of loneliness and lower quality of life (QoL) than their peers. 8 Most students knew no others with chronic illness, few disclosed their condition or registered with campus disability support services. Moreover, youth with chronic illnesses may be less likely to graduate from university than their peers. 9 Feeling socially isolated and unsupported may contribute to lower academic success and suboptimal health outcomes for young people with a chronic condition. 8 University support services (often referred to as disability or accessibility support) aim to minimise the impact of disability and health conditions on academic performance and outcomes, yet few students with diabetes access such support. 4

Interpersonal and self‐care concerns such as these are often reported among adolescents and young adults with diabetes. 10 , 11 However, commencing university typically coincides with new freedoms and independence, and the structures and environment may present specific barriers to self‐care. A better understanding of the unique self‐care challenges for university students with diabetes could inform appropriate strategies that enable students to achieve their health and academic goals. Primary research has explored experiences of university students with type 1 diabetes, 4 , 7 , 12 but some of these studies are small, 13 , 14 or focus on a single facet of student life. 15 , 16 Despite increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes in young adults, few studies have considered their concerns in this setting. 15 Therefore, this literature review aimed to identify and synthesise the research to provide a comprehensive perspective of the university experience for students with diabetes and better understand their support needs while at university.

An integrative literature review was undertaken to incorporate primary studies with diverse methodologies and comprehensively portray the topic, following the six‐step, systematic process described by Toronto and Remington: identify purpose and scope; systematic search using predetermined criteria; quality appraisal of selected literature; data analysis and synthesis; critical discussion; and dissemination of findings. 17

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included in the review were studies among undergraduate and postgraduate students diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, reporting the student experience of living with diabetes or supportive interventions conducted in the university setting. We excluded studies not specific to diabetes, among children and adolescents, that reported only clinical outcomes or service delivery, or conducted in schools, hospitals or community settings. Limits were applied for language (English only) but not for date of publication.

2.2. Search strategy

A list of search terms was defined using a combination of subject headings, keywords and phrases and modified for each database. Following preliminary searches that included synonyms for interventions, outcomes and participant perspectives, only terms for ‘diabetes’, ‘students’ and ‘university’ were retained. For the full search strategy, see Table S1 . Medline, CINAHL, Psych Info and EMBASE databases were searched 25 June 2020, and reference lists and citations of included papers checked. The Cochrane database was searched for previous reviews. The search was rerun 17 May 2022 to include the most recent publications. Search results were imported into Covidence™ database and duplicates removed. Two researchers (V.H. and T.S.) independently screened the titles and abstracts and selected full‐text articles. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

2.3. Quality appraisal

Study quality was appraised using the McMaster University Critical Review Forms for Quantitative Studies 18 and Qualitative Studies. 19 Two reviewers (V.H., T.S.) assessed 20% of papers independently and discussed methodological limitations. The remaining papers were assessed by one reviewer (V.H.). One author was contacted to correct data. 20

2.4. Data abstraction, analysis and synthesis

Data were extracted and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet (T.S.) which was first piloted and revised. A second reviewer (V.H.) re‐read all papers and checked data for completeness. Data were analysed and synthesised thematically, using an inductive approach described by Braun and Clark to identify patterns in the content. 21 This involved re‐reading articles, identifying initial codes, summarising and organising study results into themes and subthemes, which were re‐examined and refined iteratively. Results were reported using a narrative approach in order to present heterogeneous data in a cohesive, readable format. 17 , 21

We utilised the ecological model to guide the interpretation of results and for making recommendations to strengthen student support. 22 This model focuses on interactions between individuals and the sociocultural and physical environment, 22 and was adopted by the American College Health Association for campus health promotion. 23 We applied McLeroy et al.'s model, 24 which portrays five levels of influence on health behaviour: intrapersonal factors (e.g. demographic, psychological), interpersonal factors (e.g. family, social networks), institutional factors (e.g. rules, regulations, schedules), community factors (e.g. built environment, transport) and public policy (e.g. policies, legislation).

In this manuscript, ‘university’ includes tertiary colleges. Most studies only involved type 1, so ‘diabetes’ is used for brevity. ‘Self‐care’ encompasses health behaviours, taking responsibility for health and healthcare and managing emotions. 25

The database search located 3372 articles. No additional papers or reviews were located. After screening titles and abstracts, 137 full‐text articles were retrieved and critiqued against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Twenty‐five articles (20 studies) were included in the review. In two cases, several papers described the same study and reported different outcomes. 12 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 In these instances, we nominated the earliest publications as the primary source, 12 , 30 retaining the secondary papers. The PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 shows the reasons for exclusion.

PRISMA diagram. Search results and reasons for exclusion.

3.1. Study characteristics

There were 10 qualitative studies used focus groups, 1 , 14 , 32 individual interviews 6 , 12 , 15 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 or online forums 36 to explore student experiences and self‐care. Nine cross‐sectional studies examined: diabetes management, 4 , 5 , 7 , 30 , 37 alcohol‐related behaviours, 16 , 30 perceived health, 20 mental health, 31 perceived stress, coping and self‐care 38 and QoL. 13 , 30 One quasi‐experimental study examined knowledge and attitudes to alcohol. 39 Fourteen studies were conducted in the United States; three in England; and one each in Ireland, Norway and Canada. Sample sizes ranged from 9 to 25 in qualitative research, and 25–584 in quantitative studies. All papers were published since 1997; 12 within the last 10 years, and seven between 10 and 25 years. Table S1 shows study details.

3.2. Recruitment

Participants were recruited through flyers or campus newsletters, 14 , 15 , 32 , 34 , 39 College Diabetes Network (CDN), 1 , 13 , 20 , 34 , 39 email 4 , 6 , 14 , 33 , 38 or mailed questionnaire, 7 medical clinics, 4 , 12 , 32 , 37 social media 39 and Diabetes UK website. 4 One study analysed publicly available online data, 36 two accessed national student health survey data 5 , 16 and one did not report recruitment method. 35

3.3. Participant characteristics

In 16 studies, participants had type 1 diabetes. 1 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 20 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 One included students with type 1 and type 2 diabetes 15 and the type of diabetes was unknown in three studies. 5 , 16 , 36 Most studies included undergraduate and postgraduate students, 1 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 , 14 , 20 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 38 , 39 ; five focused on undergraduates, 7 , 13 , 16 , 33 , 35 and in three, graduate status was not reported/unknown. 15 , 36 , 37 Participants ranged in age from 17 to 40 years, although most studies included young adults (18–30 years) and participation was typically higher among women than men. Four to 22 per cent of participants were from minority ethnic groups (where reported) (Table 1 ).

Table of included studies

Note : Minority (populations): Non‐European/White. Theme 1: Barriers to self‐care at university; 2: Living with diabetes as a university student; 3: Identity, stigma and disclosure; 4: Strategies for managing diabetes at university.

Abbreviations: CDN, College Diabetes Network; NR: not reported; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes.

3.4. Quality assessment

Among quantitative studies, potential sources of bias were representativeness, 7 , 13 , 16 , 20 , 36 , 37 , 38 small sample size (<50 participants), 7 , 13 the use of unvalidated questionnaires 20 , 39 and self‐reported data. 4 , 5 , 7 , 16 , 20 , 30 , 37 , 38 , 39 Transferability may be limited for some qualitative studies, 1 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 and one had fewer than 10 participants. 14 Data analysis was not well explained in two studies. 32 , 35 Refer to Table 1 for details of study limitations.

3.5. Study themes

Four major themes were identified: barriers to self‐care at university; living with diabetes as a university student; identity, stigma and disclosure; and strategies for managing diabetes at university. Table 2 lists the major themes and 18 subthemes. Figure 2 represents themes according to the Ecological model.

Study themes

Ecological model. Adapted from McLeroy et al. 24 Factors influencing health behaviours for university students living with diabetes.

3.5.1. Barriers to self‐care at university

Managing diabetes was perceived to be more difficult at university than high school. 4 , 7 The first few months may present the greatest challenges, as students adapt to university life. 33 , 36 However, among UK students with type 1 diabetes, difficulties were not limited to younger students and women perceived more problems with diabetes self‐care than men. 4 Female students reported higher HbA 1c 4 , 30 and diabetes distress than males, 31 and diabetes distress was higher among older than younger students. 31 For recently diagnosed students, learning to manage diabetes made the transition to student life more complex. 1 , 4 , 27

Lack of structure and routine

Uncertainty and lack of control over situations at university frustrated students' efforts to manage their blood glucose levels optimally. In contrast to the school environment, the lack of structure and routine, such as irregular class timetables and mealtimes, interfered with maintaining a self‐care routine. 1 , 4 , 7 , 13 , 27 , 32 , 36 Insufficient time to check blood glucose and eat between classes 35 and difficulty balancing study and diabetes resulted in some students skipping classes or blood glucose checks 34 or not testing at all. 29 Self‐care routines of first‐year students often ‘slipped’ due to staying up late, partying and studying. 27 Living in student accommodation provided some structure but moving off‐campus could be problematic for students who lacked the necessary self‐care skills. 27 Balancing study, social life and blood glucose levels was described as a constant concern, 13 , 14 , 33 with students feeling guilty when their routine and diabetes management were affected. 27 Students learnt to adapt as they progressed through university, but experienced ‘glitches’ at different times, for example, during periods of stress or exams. 27 Recently diagnosed students experienced more difficulty establishing self‐care routines in the university environment than those diagnosed at an earlier age, 1 , 4 , 27 and adapted by structuring their lives or disregarding self‐care. 27 In Kellett et al.’s study, 13% of participants were diagnosed while at university. 4 These students had more difficulty managing mealtimes, food and exercise than those diagnosed prior to university.

Food and eating

Several food‐related factors were perceived to affect self‐care. Eating patterns were altered 7 and appropriate food choices were limited on campus. 1 , 4 , 14 , 32 , 33 , 36 Nutrition information about carbohydrate content was unavailable for food in the cafeteria, limiting accurate estimation of insulin doses. 13 , 14 , 36 Take‐away food and eating out was a normal part of student life but impacted glycaemia. 36 Needing to carry food and eat in class was inconvenient. 32 Food was prohibited in some areas on campus, for example, the library, examination or laboratory rooms, resulting in students missing or leaving class to manage hypoglycaemia. 1 , 14 While some students would approach the lecturer to explain their needs, others were reluctant to draw attention to their diabetes. 14

Self‐care support

Students reported feeling less supported to care for their diabetes at university than at school. 14 They had more autonomy but lacked guidance and support from their parents, 4 , 7 , 33 , 34 particularly when living away from home. 4 , 27 Students remained with their usual diabetes care team more often than transferring to local healthcare, even when moving away from home. 4 , 33 However, being unable to travel home and clashes with university timetables were barriers to attending clinic appointments. 4 , 33 , 35 Kellett et al. found that students who transferred their medical care reported higher HbA 1c , more frequent hypoglycaemia, hospital admissions and DKA than those who remained with their home specialist team. 4 Among this group, diabetes management was more likely to be impacted by alcohol, exercise and weight‐related issues. 4

Fear of hypoglycaemia

Fear of hypoglycaemia was a barrier to optimal diabetes management in four studies. 7 , 14 , 32 , 35 Hypoglycaemia or checking blood glucose might draw attention, so some students reported intentionally maintaining elevated blood glucose, 14 , 35 for example, by taking less insulin. 35

Other barriers

In four studies, students reported academic‐related stress (e.g. assessment, performance) negatively affected glycaemia. 4 , 14 , 32 , 34 Perceived general stress was associated with less frequent health behaviours (healthy eating, footcare), but positive coping skills (e.g. positive reframing, planning) predicted more frequent self‐care in one study. 38 Disturbed sleep from attending to diabetes or being woken by pump or glucose monitor alarms also impacted blood glucose levels. 1 Using a scale developed to measure attitudes and behaviours associated with diabetes self‐care at university, Widowik demonstrated that situational factors, such as social events, peers, competing priorities, stress and negative emotions, were negatively associated with self‐care. 37 Other barriers cited were finances, use of drugs and alcohol, peer pressure, disordered eating and skipping insulin. 7 Financial difficulties were also associated with high HbA 1c . 30

3.5.2. Living with diabetes as a university student

Alcohol and risky drinking.

Alcohol was a normal part of university life for young people and students drank at bars, clubs and parties. 15 , 26 Drinking alcohol was considered one of the main social activities at university and there was strong peer pressure to drink. 15 , 33 However, diabetes was perceived a barrier to socialising at university. The pressure to drink alcohol caused some students to avoid going out of an evening whereas others might forget diabetes and enjoy themselves. 35 Drinking alcohol enabled young people to develop their student identity and to appear ‘normal’, and when their condition was known, to appear capable and in‐control and not limited by diabetes. 26 Some students experimented with alcohol, testing the effect and their own limits. 15 Others limited drinking to maintain control of themselves, their diabetes or body weight and to avoid hypoglycaemia. 15

In three studies, students with diabetes described consuming alcohol at the same risky level as their peers without diabetes. 5 , 16 , 26 Cockroft et al. found that 70% of all students exceeded the recommended alcohol limits for age and gender and 42% engaged in binge drinking. 5 However, the students with diabetes used fewer protective strategies and were more likely to drive when drinking, and experience academic problems due to alcohol. Additionally, more students with diabetes reported treatment for substance use than those without diabetes. 5 In another study, 42% of students with diabetes reported drinking at excessive levels (≥5 in one sitting), and 37% (mostly younger students) reported one or more consequences of alcohol in the past year including injuring themselves, later regretting behaviour and forgetting what happened. 16 In contrast, fewer students with diabetes reported alcohol problems and harmful alcohol use than students without diabetes in a Norwegian cohort. 31 Students were aware that alcohol was a risk to their diabetes management, 7 , 26 , 39 future health and ability to work. 26 In one study, students had high self‐reported knowledge, but moderate concerns about the impact of alcohol on diabetes. 39

Alcohol‐induced hypoglycaemia threatened a ‘normal’ student identity and their independence if it occurred in public, but students were less anxious about hypoglycaemia occurring at home, believing they could deal with it themselves or be looked after by friends. 26 Older students transitioned to less risky drinking as their adult identities and social networks were more established and they were more cognisant of the risks to their health. 16 , 26

Students associated managing diabetes well with having a healthy body 34 and better self‐esteem. 28 In a UK study, students with type 1 diabetes perceived social pressure to maintain a slim and healthy body and control their condition through disciplined eating and exercise. 12 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 Men identified the desire to feel fit and healthy through sport and well‐controlled blood glucose, whereas women were concerned with body image but felt their attempts to lose weight by exercising were thwarted by hypoglycaemia. 12 Lower body weight satisfaction and unsafe weight loss strategies were more likely to be reported by students with diabetes than those without the condition. 5 Norwegian students with diabetes reported higher body mass index, 30 and lower QoL than students without diabetes, 31 but no difference in physical activity, 30 mental health, loneliness, sleep and health symptoms. 31 Some students reported adopting more healthy eating behaviours after learning about the consequences of disease in their course. 26

Impact of diabetes on academic performance

Fluctuations in blood glucose could cause fatigue and poor concentration in class, 14 difficulties completing assignments and exams and affect vision and driving. 33 , 34 Hypoglycaemia necessitated consuming food or drink to prevent or treat an episode, sometimes causing students to be late or miss classes. 33 , 34 A national college health survey in the United States found that students with diabetes had a lower grade point average (GPA) than those without diabetes and were more likely to perceive that sleep problems, disordered eating and alcohol affected their academic performance. 5

Lack of diabetes awareness

Students commented on the lack of understanding about diabetes in the community, among peers, lecturers and the media. 6 , 14 Others found peers and the public overly intrusive and offered unwelcome advice, particularly around food. 1 Some students reported neglecting self‐care in public to avoid constantly explaining their diabetes to others, 14 whereas others believed they had a responsibility to use these interactions to educate the community about diabetes. 1 University staff, including health staff, were perceived to lack knowledge about diabetes and students' needs. 33 , 36 Students felt unconfident about receiving emergency assistance for severe hypoglycaemia at university and felt less safe than at school where pupils with diabetes were well known and resources available. 14

Autonomy and growth

In six studies, students reported the positive aspects of living with diabetes. Diabetes was not perceived to deter achievement 34 and was frequently reported as a challenge that led to personal growth and maturity. 6 , 7 , 14 , 34 , 36 Going to university was an opportunity to develop independence and master diabetes self‐care, 36 and assume self‐responsibility for health. 1 In two studies, students reported optimism, enjoying life and relationships with their peers with diabetes. 1 , 34 Compassion for others was identified as an attribute of living with diabetes, 1 and some students were motivated by their condition to choose a health‐related career. 34

Worry about the future

Concerns were expressed about the impact of the student lifestyle on diabetes management and future complications. 13 , 34 , 36 As students considered life after university, they worried about gaining employment and finding a life partner that could deal with diabetes. 13 Students in the United States identified concerns about insurance and the cost of diabetes care. 13 , 32 , 36

3.5.3. Identity, stigma and disclosure

Student identity.

Students described not wanting to be different to their peers or defined by diabetes. 1 , 12 , 26 They behaved in a number of ways to maintain a ‘normal’ student identity on campus, including participating in exercise, not limiting food intake, risky drinking of alcohol, 12 , 26 staying up late and partying. 1 Checking blood glucose or treating hypoglycaemia in class could be embarrassing or invite criticism. 14 Some students reported maintaining an elevated blood glucose level to avoid these situations which would draw attention to having diabetes. 14 , 26 , 35

Diabetes stigma and telling others about diabetes

Common misunderstandings and stereotypes, for example, attributing diabetes to unhealthy lifestyles, was a constant source of stress and frustration for students with type 1 diabetes, 6 , 14 and they perceived these misconceptions reduced the level of emotional support they received within social relationships. 6 Students avoided disclosing their diabetes if they anticipated a negative reaction, such as rejection or discrimination, were made to feel different, explain diabetes or receive unsolicited advice. 6 , 14 , 29 , 32 Some female students perceived stigma around using needles. 29 Older students, particularly men, were less concerned about diabetes‐related stigma and conforming to a student identity and stated they felt comfortable testing and injecting in public. 29 Habenicht et al. also found the reasons for disclosing diabetes varied by gender. 6 Despite claiming openness, some men avoided disclosure because it may elicit pity, making them feel ‘weak’, whereas women told others about their diabetes to build trusted relationships and to be responsible.

Students usually felt comfortable disclosing diabetes for safety reasons, for example, to elicit support when needed or going out, 6 , 34 and might tell others to avoid pressure to drink alcohol. 15 For some students, performing self‐care in front of others was a mean to passively disclose diabetes, which might initiate a casual conversation about the condition. 6 Sharing their diagnosis was seen as a way to educate people about diabetes. 34 Over time, most students learnt to advocate for themselves and their health in the face of peer pressure and for adjustments to manage their diabetes and study. 1

3.5.4. Strategies for managing diabetes at university

Preparing for university.

Concerns for students preparing for university included access and storage of supplies, 33 , 34 , 36 health insurance, avoiding hazardous situations, dealing with hypoglycaemia and finding new health professionals. 36 Both young people and parents expressed concerns about students moving away from home and being without parental support, 1 , 4 , 36 which influenced university choices for participants in one study. 1 Students indicated they sought a supportive roommate, for example, one who could tolerate disturbed sleep and provide support with hypoglycaemia. 1 Most students in one study indicated they received information about diabetes management when preparing for university, but relevant resources, such as sexual health, mental health or substance use, how to access medical and disability support and flexible insulin adjustment were not regularly provided. 4

Forward planning

Students learnt to adapt their diabetes self‐care to the flexible university environment, which could involve long days and irregular schedules. 1 They recognised the need to plan ahead to manage blood glucose levels during classes, exams, exercise and social activities, deal with the effect of stress and avoid running out of diabetes supplies. 34 One risky forward planning strategy sometimes used, involved taking less insulin to maintain elevated blood glucose and avoid hypoglycaemia. 14 , 35

Obtaining support

Despite the diabetes management difficulties experienced by students, Kellett et al. found that few (9%) contacted university support services for advice or support. 4 Reported barriers to accessing support include lack of diabetes knowledge and understanding among campus staff 33 , 35 and failure of staff to make appropriate allowances for diabetes. 35 Participants in one study stated they did not feel disabled or want special privileges to succeed, 14 although in another study, students preferred to register for learning support than to individually approach lecturers for allowances. 1

Friends, particularly friends with diabetes were an important source of peer and diabetes self‐care support 6 , 20 , 32 , 33 , 34 and lessened feelings of isolation, 20 , 33 , 34 depression and anxiety. 20 Around half of students in one study wanted to meet other students with diabetes or join a peer support group. 32 Peers with diabetes understood the lived experience, 6 , 34 and such support was accessed via online forums, social media and the CDN. The CDN is a USA‐based national advocacy organisation providing events, online diabetes information and newsletters about preparing for, living and studying at university. 20 , 40 On occasion, the CDN assisted with emergency diabetes supplies. 34 A survey found that CDN members were more likely to access disability allowances than non‐members. 20

Students relied on friends and roommates to assist them during emergencies, teaching them what to do, such as administer glucagon or call emergency services in the event of severe hypoglycaemia, 1 , 6 , 13 although some had no supports in place for dealing with hypoglycaemia. 7 Being surrounded by people without knowledge of their diabetes afforded privacy and autonomy, but no ‘safety‐net’, challenging young adults to become more independent. 14 Parents were usually the main source of diabetes self‐care support and their ongoing involvement was valued, 4 , 6 , 34 , 36 although parental support was less accessible after moving away from home, which could lead students to paying their diabetes less attention. 6 For students who perceived their parents were over‐involved in their diabetes, going to university was an opportunity to achieve independence. 34

Using technology

Diabetes technology such as insulin pumps and glucose monitoring enabled greater flexibility with the social aspects of student life, dealing with stress and the unstructured university environment. 29 Students using an insulin pump found alcohol easier to manage. 15 , 29

Using technology allowed some students to feel and appear ‘normal’. 29 In contrast, others felt technology made their diabetes visible, so avoided checking blood glucose or injecting insulin in public. 26 These concerns were expressed more often by younger and female students due to perceived diabetes stigma and the effect of wearing technology on appearance. 29

Alcohol management strategies

In online posts, students reported incidents of severe hypoglycaemia due to alcohol but not knowing how to manage their diabetes when drinking. 36 Drinking habits may not be regularly discussed with healthcare professionals. 15 , 39 Students used a variety of methods to moderate the risks of alcohol and having strategies in place predicted less drinking and fewer consequences. 16 Strategies included eating before and/or after drinking, 15 , 16 , 26 , 32 avoiding parties and bars, 15 socialising but not drinking alcohol, 1 , 15 , 16 , 26 having personal rules about the type and amount of alcohol they can safely consume, 15 , 39 avoiding drinking games, pacing or keeping track of drinks, 15 , 16 choosing drinks with sugar or sugar‐free, 26 taking insulin to cover alcohol, 15 , 32 monitoring blood glucose 15 , 26 , 39 and drinking with friends. 39 Friends were helpful by either not pressuring them to drink or by assisting in an emergency. 15 Short‐term improvements in binge drinking, knowledge, attitudes, concerns and intentions were reported after alcohol and diabetes education. 39

4. DISCUSSION

This first integrated literature review about students with diabetes at university identified consistent patterns in the concerns and challenges for young adults and highlighted features of the university environment that present barriers to self‐care. These themes will be discussed according to the ecological model, including implications for future research and practice, and recommendations for multilevel support that can be adopted by health professionals and tertiary education institutions.

4.1. Intrapersonal factors

Managing diabetes may not be easier for students as they get older. Diabetes distress was higher among students aged 24–29 than 18–23 years, 31 a trend also found in the DAWN2 study, with the older group feeling more overwhelmed and less supported. 41 Diabetes distress characterises many of the concerns and feelings expressed by students, and affects around one‐third of young adults with diabetes. 42 It is encouraging that mental health problems were not more prevalent and students with diabetes were as physically active as their counterparts without diabetes, but QoL was lower, most likely related to the specific burden of diabetes. 43 , 44 Women perceived more difficulties and distress than men, which is a consistent finding from adolescence onwards. 45

Students perceived diabetes affected them academically. One study reported slightly lower GPA, 5 which could influence future socioeconomic and health status. However, a small study among school leavers found no difference in workforce participation, higher education or GPA with or without diabetes. 43 Acute glycaemic excursions can impair cognitive performance, 46 and elevated HbA 1c is associated with lower academic achievement among adolescents. 46 , 47 While academic stress may cause short‐term fluctuations in glycaemia, students with prolonged suboptimal glycaemia are also more likely to experience diabetes distress and mental health problems 31 and students with mental health‐related, 48 or more than one disability, are less likely to graduate than other students. 49 For those from disadvantaged backgrounds, financial pressures to work or stress may further affect self‐care 30 and attention to study, while already confronting psychological and material barriers to success at university. 50 Students experiencing prolonged stress and distress could benefit from ongoing academic, financial and psychological support. Students diagnosed shortly before or while at university also need support to develop problem‐solving skills usually acquired in adolescence. 51

4.2. Interpersonal factors

Students experienced social concerns reported by young adults with diabetes elsewhere, namely, body image and unwillingness to disclose diabetes due to perceived stigma and unwanted attention. 41 , 44 , 52 These mindsets diminish with age but can intensify during transitions to new environments and with new social groups and present a barrier to self‐care in these situations. 44 Better community awareness may help to lessen the negative consequences of diabetes stigma, which disproportionately affects women. 53

Similar rates of binge drinking of alcohol are reported among youth with and without diabetes, 5 , 16 , 26 , 43 although student culture and peer pressure encourage underage, and risky drinking in the university setting. 15 , 33 , 54 Without parental surveillance, alcohol and drugs present a greater risk for students with diabetes living out of home. In a study of underage drinking at university, alcohol marketing, rewards (e.g. relaxation, getting drunk) and education predicted higher alcohol intake, 54 whereas, enforcing alcohol control policies, 55 skills‐based and motivational interventions may reduce alcohol consumption. 54 Psychoeducation interventions focused on harm reduction among students are likely to be more influential than general awareness of alcohol and diabetes. 39

As young adults transition to university or work, parental monitoring and involvement decreases and often HbA 1c increases, but this may be mitigated by developing problem‐solving skills, 51 and ongoing parental support. 56 Friends and partners may take over providing emotional and practical support. The CDN has over 140 Chapters in the United States, offering peer support and information tailored to students with diabetes. 40 Although CDN resources are accessible, they are tailored to the USA context.

4.3. Institutional factors

Students with diabetes are entitled to reasonable adjustments to accommodate diabetes, for example, access to food and extra time for exams. Accessing support is associated with higher odds of graduating for students with disabilities. 48 However, few students with diabetes take advantage of this support, and institutional barriers to accessing services include staff attitudes, appropriateness of accommodations and communication about disability services. 57 Students relied on friends and roommates in emergencies, yet institutions have responsibilities to ensure students living on campus are safe and should have policies in place. 58 Students living independently need to consider strategies for checking their well‐being, in contrast to school or the workplace where attendance is monitored.

4.4. Community factors and public policy

The community level includes campus facilities, such as cafes, meal services and alcohol outlets. Adapting to these factors requires preparation and planning skills that emerge with maturity. At the policy level, anti‐discrimination legislation obliges universities to provide adjustments to enable students to fully participate in their education. 59

4.5. Limitations and strengths

There are several limitations to this research. We restricted publications to the English language which could have omitted relevant studies. In most studies, participants had type 1 diabetes, were aged under 30 years and more likely to be female, so the results may not be generalisable. We included type 2 diabetes in our search but located only one paper and none in students over the age of 40. Several studies recruited through the CDN so likely to represent more socially connected students. There were no studies that could demonstrate effective interventions to support students and few studies considered socioeconomic or racial background; factors likely to increase disparities for students with diabetes. We were unable to synthesise the data quantitatively due to the heterogeneity of studies. Nevertheless, the review was rigorously conducted following Toronto and Remington's methodology, 17 and we were able to incorporate the available evidence from different study designs, the findings of which were highly consistent. Most studies were conducted in the United States where students typically leave home to attend university and the legal drinking age is high compared to other countries (21 years). 54 These two factors may influence alcohol‐related and self‐care behaviours, so some findings may not be transferable to all settings.

4.6. Future research

There are gaps in the literature about students with type 2 diabetes, older adults and those from ethnic minorities or attending technical colleges who may experience socio‐economic disadvantage. The needs of students with complications should be explored. Further understanding is needed of the barriers to accessing disability services and student preferences for support and whether such support improves outcomes, as are evidence‐based interventions to minimise alcohol risk for students with diabetes. Outcome evaluation of support programmes such as CDN could help to advocate for establishing such programmes elsewhere.

4.7. Implications for policy and practice

Most student concerns identified in this review are experienced by young adults with type 1 diabetes. However, problems are exacerbated during life transitions and interactions with the university environment. Support could be enhanced at multiple levels.

4.7.1. Intrapersonal

Female students, students with mental health problems or those from ethnic minority or disadvantaged populations, are likely to have more problems dealing with their diabetes and to benefit from disability, academic and psychological support while at university.

4.7.2. Interpersonal

Institutions could improve understanding of diabetes in their community to minimise stigma.

4.7.3. Institutional

Institutions could monitor academic outcomes and ensure disability services are accessible and tailored for diverse students, living on‐ and off‐campus and different types of diabetes, and promote engagement. Health professionals and universities could provide evidence‐based practical information about alcohol and drug safety.

4.7.4. Community and policy

Organisations such as CDN could advocate and provide information tailored to the student experience at a campus, state or national level.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This integrated review of published studies identified consistent themes about diabetes self‐care difficulties and risky behaviours were reported by young adults with diabetes after moving from school to the less structured university setting. Some students need support to manage their diabetes in this environment and self‐care resources tailored to university lifestyles, paying particular attention to the early years at university, those leaving home or recently diagnosed with diabetes. These findings provide a foundation for the development of resources and interventions tailored to the needs of this priority population. Further research into the experiences and support needs of older students, those from diverse backgrounds and type 2 diabetes would address gaps in the literature.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Virginia Hagger designed the study, conducted the review and drafted the first version of the manuscript. Tarveen Singh assisted with searching, appraisal and data extraction. Bodil Rasmussen, Amelia J. Lake, Peter S. Hamblin contributed to the review design, search strategy and critical revisions to the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Acknowledgement.

This project was supported by funding from the Australian Diabetes Educator's Association Diabetes Research Foundation. Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Hagger V, Lake AJ, Singh T, Hamblin PS, Rasmussen B. The experiences and support needs of students with diabetes at university: An integrative literature review . Diabet Med . 2023; 40 :e14943. doi: 10.1111/dme.14943 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Campus Directory

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

Diabetes Case Study

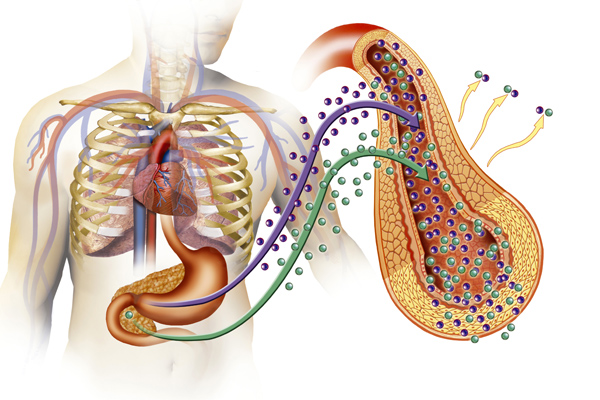

There has been a 350-fold increase of type 1 diabetes in the past 50 years in Europe and North America. This autoimmune disease usually strikes children and teens. Thirty-five percent of individuals with type 1 diabetes will die of heart disease by the age of 55. Eighty percent will develop retinopathy within 15 years of diagnosis leading to subsequent blindness. Twenty to forty percent will develop kidney disease before the age of 50. In this case we’ll experience the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of diabetes with six-year-old Ali.

Module 5: Diabetes

Ali's mother knew there was something not quite right with her daughter lately...

Diabetes - Page 1

In the emergency room, a urine sample was collected for urinalysis and blood was drawn...

Diabetes - Page 2

The laboratory results were consistent with Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) as a result of...

Diabetes - Page 3

A meeting with the dietician was next. Insulin is given based upon the amount of food that will...

Diabetes - Page 4

Case Summary

Summary of the Case

Diabetes - Summary

Answers to Case Questions

Diabetes - Answers

Professionals

Health Professionals Introduced in Case

Diabetes - Professionals

Additional Links

Optional Links to Explore Further

Diabetes - Links

Diabetes Mellitus Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

What additional nursing assessments should be performed at this time?

- POC glucose

- Heart and lung sounds and respiratory effort – ensure she is protecting her airway

- Assess skin and mucous membranes

- Level of consciousness and orientation

What history questions would you like to ask of the patient and/or her parents?

- Has she been excessively thirsty or hungry lately

- Has she been urinating a lot

- Has she lost weight unintentionally?

- Is there a history of diabetes in the family?

- Has she been told previously that she has diabetes?

- Does she take any medications on a daily basis?

Upon further questioning, the parents report that their daughter has been weak a lot lately. Miss Matthews reports but she’s always hot and exhausted. She reports a 10-pound weight loss over the last 2 months despite eating all the time and agrees that she has been thirsty and peeing a lot.

What diagnostic tests should be run for Miss Matthews?

- Serum glucose level

- BMP – electrolytes, anion gap, etc.

- ABG to assess for acidosis

- Urine ketones

What is an appropriate response by the nurse?

- Your daughter has Type 1 diabetes, which means that she has an autoimmune disorder that attacks the cells in her pancreas that make insulin. Type 1 diabetes typically has nothing to do with diet and lifestyle and usually has more to do with genetics.

- Your daughter’s healthy lifestyle will continue to help her control her blood sugar levels, but unfortunately, there is no cure for type 1 diabetes at this time.

What treatments do you expect to be ordered for Miss Matthews at this time?

- Miss Matthews will need intensive insulin therapy and IV fluids to counteract the ketoacidosis and bring her blood sugars down.

- She will then need to be started on long-acting insulin like Lantus and short-acting insulin-like NovoLog for correction with meals.

Miss Matthews is treated for diabetic ketoacidosis over the next 2 days and is now feeling much better. The diabetic nurse educator comes by to teach Miss Matthews how to self-administer SubQ insulin using an insulin pen. Miss Matthews says “I can’t stand needles, isn’t there a pill I can take instead?”

What is the most appropriate response by the nurse?

Unfortunately, at this time insulin is not available in pill form. It has to be taken via injection. Otherwise, it will not work correctly.

What options does Miss Matthews have for insulin administration?

- Insulin vial with needles

- Insulin pen

- Insulin pump

Miss Matthews is able to demonstrate proper technique for glucose monitoring and self-administration of insulin with the insulin pen. Her blood glucose levels are stable between 140 and 180 mg/dL, and the provider has said that she could go home today.

In addition to the insulin education, she has already received, what other education topics should be included in discharge teaching for Miss Matthews?

- Miss Matthews should be taught how to count carbohydrates to determine the amount of insulin required.

- She should be given a prescribed sliding scale or insulin protocol to follow.

- Miss Matthews should also be instructed on when to take her long-acting insulin and when to take regular insulin in relation to meal times. It is important that she does not take short-acting insulins without being ready to eat.

- Miss Matthews should be educated on the possibility of morning hyperglycemia due to the Somogyi effect or Dawn phenomenon, and be given suggestions to try an evening dose of insulin or an evening snack.

- The importance of follow-up appointments with her primary care provider and/or endocrinologist should be stressed. She should have her Hgb A1c checked every 3 months to start with.

- She should also be educated on foods to avoid, such as desserts and sweets, and foods that are beneficial, such as fruits and vegetables and high-quality proteins.

- Miss Matthews should carry some candy or glucose tablets with her in case of a hypoglycemic reaction.

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Review Questions

QUESTION ONE

When Mr. Johnson was first diagnosed with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus what classic symptoms should he have been told he would exhibit? Select all that apply.

a. Visual changes, recurrent infections, and pruritis

b. Nausea, hypotension, and mental confusion

c. Polyuria, polyphagia, and polydipsia

d. Sweet fruity breath, Kussmaul breathing, and vomiting

QUESTION TWO

What risk factors increase the chances of developing Type II diabetes?

a. Smoking, race, diet, family history, and height

b. Family history, hygiene, smoking, increased age, and hypertension

c. Hygiene, lifestyle, genetics, smoking, and obesity

d. Family history, increased age, obesity, hypertension, and smoking

QUESTION THREE

What does insulin resistance mean?

a. The pancreas is underactive and can keep up with the production of insulin needed to overcome the high amount of glucose in the blood.

b. Glucose is raised above normal levels.

c. The inability for cells to absorb and use blood sugar for energy.

d. The pancreas is overactive and cannot keep up with the insulin demands due to an abundance of glucose in the blood.

QUESTION FOUR

What evidence-based suggestions can you provide your patients to prevent or manage Type II diabetes?

a. Eating whatever you desire as long as you work out.

b. Eating a healthy diet and exercising.

c. Eating a healthy diet only.

d. Staying inside all day under the blankets.

QUESTION FIVE

What are the long term effects of untreated Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? [Select all that apply]

a. Blindness

b. Kidney Disease

c. Tinnitus

d. Peripheral Neuropathy

Answer: A & C

Visual changes, recurrent infections, and pruritis are all complications of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Although polyuria, polyphagia, and polydipsia are known as the classic symptoms for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, they are also present in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nausea, hypotension and mental confusion are signs of hypoglycemia. Sweet fruity breath, Kussmaul respirations, and vomiting are signs of diabetic ketoacidosis.

Reference: McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2019). Pathophysiology: the biologic basis for disease in adults and children (8th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Answer: D, risk factors for type II diabetes include obesity, diet, lack of exercise, race, increased age, and family history.

Maintaining a healthy weight and engaging in physical activity helps to control weight, uses glucose for energy and allows cells to be more sensitive to insulin. Having a family history increases the risk of type II diabetes. For unclear reasons, African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, and Asian Americans have an increased risk of developing type II diabetes. An increase in age is also a risk factor due to weight gain and the tendency to be less active. A diet high in red meats, processed carbohydrates, sugar, and saturated and trans fat increases the risk of type II diabetes. Options A, B, and C are incorrect. Height and hygiene are not contributing factors.

Type 2 diabetes. (2019, January 9). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/type-2-diabetes/symptoms-causes/syc-20351193 .

Answer: C. Insulin resistance is the inability for cells to absorb and use blood sugar for energy due to cells being desensitized to insulin.

Cells that are desensitized to insulin do not take up insulin thus not taking up glucose to use for energy. Option A is incorrect, the pancreas becomes overactive when there is a high level of glucose in the blood but does not define insulin resistance. Option B is the lab value result of a patient with diabetes. Option D is what happens with type II diabetes but does not define insulin resistance.

Felman, A. (2019, March 26). Insulin resistance: Causes, symptoms, and prevention. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/305567.php.

Answer: B. Eating a healthy diet and exercising to maintain a healthy weight or lose weight.

Eating a healthy diet, high in fruits and vegetables and low in carbs helps the pancreas not get overworked creating insulin thus keeping blood glucose levels in a normal range. Exercising allows for hypertrophy of the muscles which respond better to insulin after exercise. Therefore, an active person can help prevent or reverse insulin resistance. Option A does not help a patient manage their diabetes if the same high carb, high sugar foods are being consumed. Option C should be complimented with exercise to help the muscles respond better to insulin. Option D will only worsen diabetes due to a lack of exercise.

The Diabetes Diet. (2019, June 19). Retrieved from https://www.helpguide.org/articles/diets/the-diabetes-diet.htm.

Answers: A, B, C & D

This patient already wears glasses, so he is at risk for blindness due to the risk of glaucoma, cataracts, and diabetic retinopathy from persistent hyperglycemia. Kidney disease can occur from untreated diabetes due to persistent hypertension and strain on the kidneys. Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure in the U.S. Tinnitus is ringing in the ears caused by inadequate blood flow to vessels in the ear due to hyperglycemia. Peripheral neuropathy occurs from nerve damage as well from high levels of glucose in the bloodstream. This increases the risk of infection and amputation of feet.

Felson, S. (Ed.). (2019, May 6). Diabetes Complications: How Uncontrolled Diabetes Affects Your Body. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/diabetes/guide/risks-complications-uncontrolled-diabetes#1.Holcát,

M. (2007, May). Tinnitus and diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17642439.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2018). Pathophysiology: the biologic basis for disease in adults and children . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

6 Ways to Teach Diabetes to Nursing Students

Share this blog

Ready to discover ubisim.

Diabetes, a chronic condition affecting approximately 8% of the global population, and nearly 30% of Americans age 65 or older, is something that nurses will often encounter. For nursing students, learning the complexities of diabetes care is crucial, as they are on the front lines of patient interaction and management.

Effective teaching strategies are essential to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Here are six active learning approaches to teaching diabetes to nursing students, enhancing their learning experience, and preparing them for real-world challenges.

1. Low-Fidelity Simulations

These simulations involve the use of basic tools and resources to mimic real-life scenarios, providing students with a hands-on learning experience that enhances their understanding of how to manage diabetes in clinical settings. By incorporating low-fidelity simulations into their education, nursing students can practice assessing blood sugar levels, administering insulin, and responding to low blood glucose episodes in a controlled environment.

Realityworks Diabetes Education Kit is an example.

2. Gamification Techniques

Gamification introduces the elements of game playing, such as scoring points, competing with others, and following rules, into the educational process to enhance engagement and motivation. By incorporating gamification in diabetes education, complex concepts can be simplified, making learning both fun and effective.

There's a game called “ Candy Gland ” that nurse educators can use. “This educational game effectively improved student knowledge and confidence in diabetes diagnosis, pharmacology, and management in an engaging, unique session.”

3. Immersive Virtual Reality (VR) Tools

Leveraging immersive VR tools offers nursing students a unique opportunity to step into the shoes of a nurse. UbiSim is a VR platform built just for nurses by nurse educators. Through any of the four diabetes simulations in the UbiSim catalog, students can experience the management of diabetes in a controlled yet realistic environment. They can make mistakes in VR so that they don't make them in a clinical setting.

Utilizing VR even helps prepare learners for the Next Gen NCLEX by boosting their clinical judgment skills. They have to decide what to do next, such as administering insulin or assuring the stressed patient that they'll be okay. VR is a great way to practice handling difficult conversations, such as discussing lifestyle changes or the importance of adherence to treatment plans.

Request a demo of UbiSim today to help your nurse learners step into the shoes of a real nurse!

4. Role-Playing Scenarios

Role-playing is a dynamic teaching strategy that allows nursing students to practice communication, clinical decision-making, and patient education in a safe and supportive environment. By taking on roles such as the nurse, patient, or family member, students can explore different perspectives on diabetes management.

This approach helps students develop empathy and improve their ability to educate and support patients in managing their diabetes.

5. Case Studies

Case studies are an effective way to connect theoretical knowledge with clinical practice. By analyzing real scenarios, students can apply their learning to diagnose, manage, and provide holistic care to patients with diabetes.

This method encourages critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and evidence-based practice. Case studies can be presented in various formats, such as written documents, videos, or interactive discussions, providing a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and complexities involved in diabetes care.

6. Connecting Topics to Real-world Scenarios

Integrating real-world scenarios into the curriculum ensures that nursing students can relate theoretical knowledge to practical applications. This can be achieved through guest lectures from diabetes care specialists, or just thinking about a person in their life who has diabetes.

Such experiences enable students to observe and understand the impact of diabetes on individuals and communities, reinforcing the importance of patient-centered care and public health education. Connecting learning to real-world situations prepares students for the realities of nursing practice and the role they will play in managing and preventing diabetes.

Final Thoughts

Educating nursing students on diabetes through innovative teaching strategies is vital in preparing them for the complexities of healthcare delivery. Educators can enhance active learning experiences, foster critical thinking, and equip students with the skills necessary to provide exceptional care to patients with diabetes. These approaches not only improve knowledge and practical skills but also emphasize the importance of empathy, communication, and patient education in managing chronic conditions like diabetes.

As an integral center of UbiSim's content team, Ginelle pens stories on the rapidly changing landscape of VR in nursing simulation. Ginelle is committed to elevating the voices of practicing nurses, nurse educators, and program leaders who are making a difference.

Explore more

_cableRemoved.jpg)

Securing Success with UbiSim: Strategies for Faculty to Champion and Sustain VR Learning

Secure UbiSim's success in your institution with strategic planning, stakeholder engagement, and tailored training. Discover tips to maximize VR learning adoption and ROI.

Orienting Faculty & Nurse Learners to UbiSim

Learn more about how the University of Manitoba's College of Nursing utilizes UbiSim VR for clinical training amidst the nursing shortage.

How to Teach Nursing Students to Use the Nasogastric Tube

Discover effective methods to teach nursing students nasogastric tube insertion and management, enhancing their practical skills through varied learning modalities.

- Diabetes & Primary Care

- Vol:23 | No:02

Interactive case study: Making a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- 12 Apr 2021

Share this article + Add to reading list – Remove from reading list ↓ Download pdf

Diabetes & Primary Care ’s series of interactive case studies is aimed at GPs, practice nurses and other professionals in primary and community care who would like to broaden their understanding of type 2 diabetes.

The three mini-case studies presented with this issue of the journal take you through what to consider in making an accurate diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

The format uses typical clinical scenarios as tools for learning. Information is provided in short sections, with most ending in a question to answer before moving on to the next section.

Working through the case studies will improve your knowledge and problem-solving skills in type 2 diabetes by encouraging you to make evidence-based decisions in the context of individual cases.

Crucially, you are invited to respond to the questions by typing in your answers. In this way, you are actively involved in the learning process, which is a much more effective way to learn.

By actively engaging with these case histories, I hope you will feel more confident and empowered to manage such presentations effectively in the future.

Colin is a 51-year-old construction worker. A recent blood test shows an HbA 1c of 67 mmol/mol. Is this result enough to make a diagnosis of diabetes?

Rao, a 42-year-old accountant of Asian origin, is currently asymptomatic but has a strong family history of type 2 diabetes. Tests have revealed a fasting plasma glucose level of 6.7 mmol/L and an HbA 1c of 52 mmol/mol. How would you interpret these results?

43-year-old Rachael has complained of fatigue. She has a BMI of 28.4 kg/m 2 and her mother has type 2 diabetes. Rachael’s HbA 1c is 46 mmol/mol. How would you interpret her HbA 1c measurement?

By working through these interactive cases, you will consider the following issues and more:

- The criteria for the correct diagnosis of diabetes and non-diabetic hyperglycaemia.

- Which tests to use in different circumstances to determine a diagnosis.

- How to avoid making errors in classification of the type of diabetes being diagnosed.

- The appropriate steps to take following diagnosis.

Diabetes Distilled: Optimising sleep – simple questions and goals

Q&a: lipid management – part 1: measuring lipids and lipid targets, q&a: lipid management – part 2: use of statins, editorial: updated guidance on prescribing incretin-based therapy, cardiovascular risk reduction and the wider uptake of cgm, updated guidance from the pcds and abcd: managing the national glp-1 ra shortage, at a glance factsheet: tirzepatide for management of type 2 diabetes, how to diagnose and treat hypertension in adults with type 2 diabetes.

The importance of sleep in type 2 diabetes management.

22 May 2024

Claire Davies and Patrick Wainwright answer questions on lipid monitoring, triglycerides, familial hypercholesterolaemia and more.

21 May 2024

Claire Davies answers questions on statin prescribing and monitoring.

Jane Diggle highlights advice on preventing eye damage when initiating new incretin-based therapies.

20 May 2024

Sign up to all DiabetesontheNet journals

- CPD Learning

- Journal of Diabetes Nursing

- Diabetes Care for Children & Young People

- The Diabetic Foot Journal

- Diabetes Digest

Useful information

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Editorial policies and ethics

By clicking ‘Subscribe’, you are agreeing that DiabetesontheNet.com are able to email you periodic newsletters. You may unsubscribe from these at any time. Your info is safe with us and we will never sell or trade your details. For information please review our Privacy Policy .

Are you a healthcare professional? This website is for healthcare professionals only. To continue, please confirm that you are a healthcare professional below.

We use cookies responsibly to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue without changing your browser settings, we’ll assume that you are happy to receive all cookies on this website. Read about how we use cookies .

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

- MEDICAL ASSISSTANT

- Abdominal Key

- Anesthesia Key

- Basicmedical Key

- Otolaryngology & Ophthalmology

- Musculoskeletal Key

- Obstetric, Gynecology and Pediatric

- Oncology & Hematology

- Plastic Surgery & Dermatology

- Clinical Dentistry

- Radiology Key

- Thoracic Key

- Veterinary Medicine

- Gold Membership

Case study of a patient living with diabetes mellitus