- All Editing

- Manuscript Assessment

- Developmental editing: use our editors to perfect your book

- Copy Editing

- Agent Submission Pack: perfect your query letter & synopsis

- Our Editors

- All Courses

- Ultimate Novel Writing Course

- Simply Self-Publish: The Ultimate Self-Pub Course for Indies

- How To Write A Novel In 6 Weeks

- Self-Edit Your Novel: Edit Your Own Manuscript

- Jumpstart Your Novel: How To Start Writing A Book

- Creativity For Writers: How To Find Inspiration

- Edit Your Novel the Professional Way

- All Mentoring

- Agent One-to-Ones

- London Festival of Writing

- Pitch Jericho Competition

- Online Events

- Getting Published Month

- Build Your Book Month

- Meet the Team

- Work with us

- Success Stories

- Novel writing

- Publishing industry

- Self-publishing

- Success stories

- Writing Tips

- Featured Posts

- Get started for free

- About Membership

- Upcoming Events

- Video Courses

Novel writing ,

Writing dialogue in fiction: 7 easy steps.

By Harry Bingham

Speech gives life to stories. It breaks up long pages of action and description, it gives us an insight into a character, and it moves the action along. But how do you write effective dialogue that will add depth to your story and not take the reader away from the action?

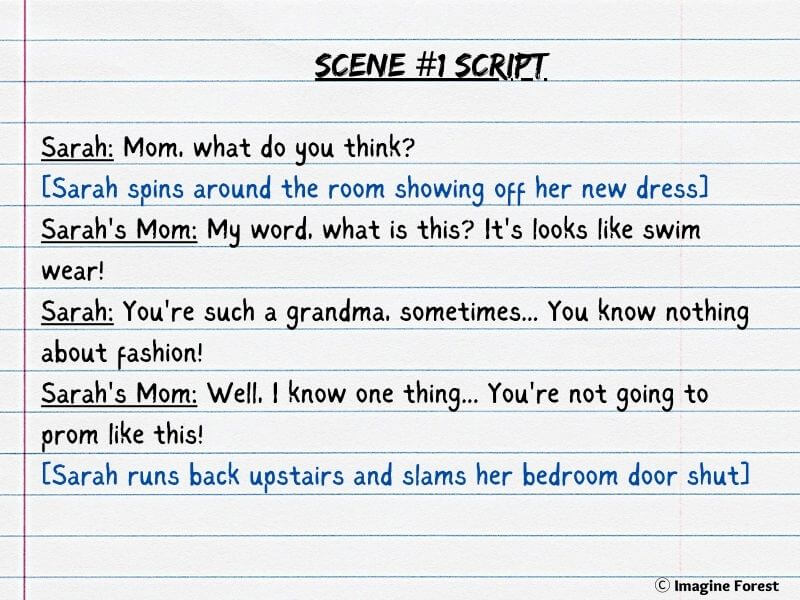

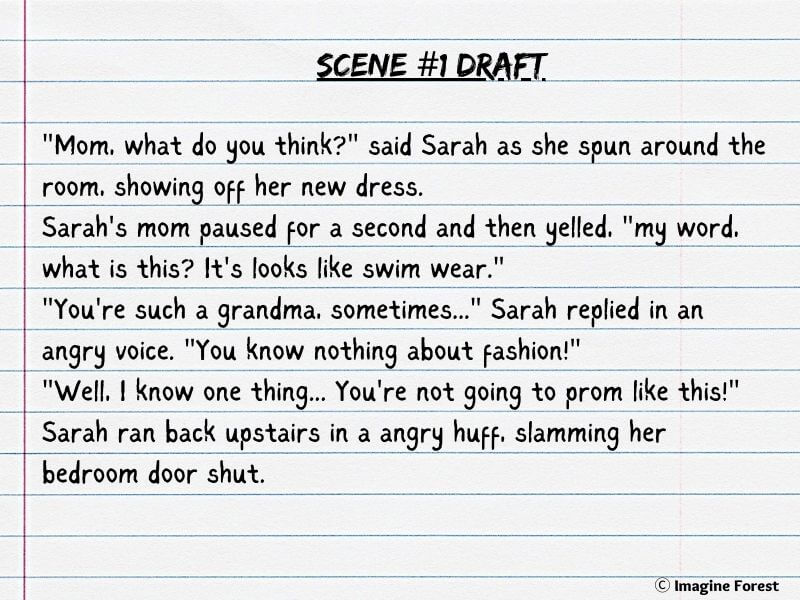

In this article I will be guiding you through seven simple steps for keeping your fictional chat fresh, relevant and tight. As well as discussing dialogue tags and showing you dialogue examples.

Time to talk…

7 Easy Steps For Compelling Dialogue

Getting speech right is an art but, fortunately, there are a few easy rules to follow. Those rules will make writing dialogue easy – turning it from something static, heavy and un-lifelike into something that shines off the page.

Better still, dialogue should be fun to write, so don’t worry if we talk about ‘rules’. We’re not here to kill the fun. We’re here to increase it. So let’s look at some of these rules along with dialogue examples.

“Ready?” she asked.

“You bet. Let’s dive right in.”

How To Write Dialogue In 7 Simple Steps:

- Keep it tight and avoid unnecessary words

- Hitting beats and driving momentum

- Keep it oblique, where characters never quite answer each other directly

- Reveal character dynamics and emotion

- Keep your dialogue tags simple

- Get the punctuation right

- Be careful with accents

Want more writing advice?

Our most comprehensive course is back, offering an unrivalled level of support, guidance, industry connections and opportunity.

Open to writers across the world, the Ultimate Novel Writing Course is now accepting applications for our Winter 24/25 intake.

Dialogue Rule 1: Keep It Tight

One of the biggest rules when writing with dialogue is: no spare parts. No unnecessary words. Nothing to excess.

That’s true in all writing, of course, but it has a particular acuteness (I don’t know why) when it comes to dialogue.

Dialogue Helps The Character And The Reader

Everything your character says has to have a meaning. It should either help paint a more vivid picture of the person talking (or the one they are talking to or about), or inform the other character (or the reader) of something important, or it should move the plot forward.

If it does none of those things then cut it out! Here’s an example of excess chat:

“Good morning, Henry!”

“Good morning, Diana.”

“How are you?” she asked.

“I’m well. How are you?”

“I’m fine, thank you.” She looked up at the blue sky. “Lovely weather we’re having.”

Are you asleep yet? You should be. It’s boring, right?

Sometimes you don’t need two pages of dialogue. Sometimes a simple exchange can be part of the narrative. If you want your readers to know an interaction like this has taken place, then simply say – Henry passed Diana in the street and they exchanged pleasantries.

If you want the reader to know that Henry finds Diana insufferably then you can easily sum that up by writing – Henry passed Diana in the street and they exchanged pleasantries. As always she looked up at the sky before commenting on the weather, as if every day that week hadn’t been gloriously sunny. It took ten minutes to get away, by which time his cheeks were aching from all the forced smiling.

No Soliloquies Allowed (Unless You’re Shakespeare)

This rule also applies to big chunks of dialogue. Perhaps your character has a lot to say, but if you present it as one long speech it will feel to the modern reader like they’ve been transported back to Victorian England.

So don’t do it!

Keep it spare. Allow gaps in the communication (intersperse with action and leave plenty unsaid) and let the readers fill in the blanks. It’s like you’re not even giving the readers 100% of what they want. You’re giving them 80% and letting them figure out the rest.

Take this example of dialogue, for instance, from Ian Rankin’s fourteenth Rebus crime novel, A Question of Blood . The detective, John Rebus, is phoned up at night by his colleague:

… “Your friend, the one you were visiting that night you bumped into me …” She was on her mobile, sounded like she was outdoors.

“Andy?” he said. ‘Andy Callis?”

“Can you describe him?”

Rebus froze. “What’s happened?”

“Look, it might not be him …”

“Where are you?”

“Describe him for me … that way you’re not headed all the way out here for nothing.”

That’s great isn’t it? Immediate. Vivid. Edgy. Communicative.

But look at what isn’t said. Here’s the same passage again, but with my comments in square brackets alongside the text:

[Your friend: she doesn’t even give a name or give anything but the barest little hint of who she’s speaking about. And ‘on her mobile, sounded like she was outdoors’. That’s two sentences rammed together with a comma. It’s so clipped you’ve even lost the period and the second ‘she’.]

[Notice that this is exactly the way we speak. He could just have said “Andy Callis”, but in fact we often take two bites at getting the full name, like this. That broken, repetitive quality mimics exactly the way we speak . . . or at least the way we think we speak!]

[Uh-oh. The way she jumps straight from getting the name to this request indicates that something bad has happened. A lesser writer would have this character say, ‘Look, something bad has happened and I’m worried. So can you describe him?’ This clipped, ultra-brief way of writing the dialogue achieves the same effect, but (a) shows the speaker’s urgency and anxiety – she’s just rushing straight to the thing on her mind, (b) uses the gap to indicate the same thing as would have been (less well) achieved by a wordier, more direct approach, and (c) by forcing the reader to fill in that gap, you’re actually making the reader engage with intensity. This is the reader as co-writer – and that means super-engaged.]

[Again: you can’t convey the same thing with fewer words. Again, the shimmering anxiety about what has still not been said has extra force precisely because of the clipped style.]

[A brilliantly oblique way of indicating, ‘But I’m frigging terrified that it is.’ Oblique is good. Clipped is good.]

[A non-sequitur, but totally consistent with the way people think and talk.]

[Just as he hasn’t responded to what she just said, now it’s her turn to ignore him. Again, it’s the absences that make this bit of dialogue live. Just imagine how flaccid this same bit would be if she had said, “Let’s not get into where I am right now. Look, it’s important that you describe him for me . . .”]

Gaps are good. They make the reader work, and a ton of emotion and inference swirls in the gaps.

Want to achieve the same effect? Copy Rankin. Keep it tight. And read this .

Dialogue Rule 2: Watch Those Beats

More often than not, great story moments hinge on character exchanges with dialogue at their heart. Even very short dialogue can help drive a plot, showing more about your characters and what’s happening than longer descriptions can.

(How come? It’s the thing we just talked about: how very spare dialogue makes the reader work hard to figure out what’s going on, and there’s an intensity of energy released as a result.)

But right now, I want to focus on the way dialogue needs to create its own emotional beats. So that the action of the scene and the dialogue being spoken becomes the one same thing.

Here’s how screenwriting guru Robert McKee puts it:

Dialogue is not [real-life] conversation. … Dialogue [in writing] … must have direction. Each exchange of dialogue must turn the beats of the scene … yet it must sound like talk.

This excerpt from Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs is a beautiful example of exactly that. It’s short as heck, but just see what happens.

As before, I’ll give you the dialogue itself, then the same thing again with my notes on it:

“The significance of the chrysalis is change. Worm into butterfly, or moth. Billy thinks he wants to change. … You’re very close, Clarice, to the way you’re going to catch him, do you realize that?”

“No, Dr Lecter.”

“Good. Then you won’t mind telling me what happened to you after your father’s death.”

Starling looked at the scarred top of the school desk.

“I don’t imagine the answer’s in your papers, Clarice.”

Here Hannibal holds power, despite being behind bars. He establishes control, and Clarice can’t push back, even as he pushes her. We see her hesitancy, Hannibal’s power. (And in such few words! Can you even imagine trying to do as much as this without the power of dialogue to aid you? I seriously doubt if you could.)

But again, here’s what’s happening in detail

[ Beat 1: What a great line of dialogue! Invoking the chrysalis and moth here is magical language. it’s like Hannibal is the magician, the Prospero figure. Look too at the switch of tack in the middle of this snippet. First he’s talking about Billy wanting to change – then about Clarice’s ability to find him. Even that change of tack emphasises his power: he’s the one calling the shots here; she’s always running to keep up.]

[ Beat 2 : Clarice sounds controlled, formal. That’s not so interesting yet . . . but it helps define her starting point in this conversation, so we can see the gap between this and where she ends up.]

[ Beat 3 : Another whole jump in the dialogue. We weren’t expecting this, and we’re already feeling the electricity in the question. How will Clarice react? Will she stay formal and controlled?]

[ Beat 4 : Nope! She’s still controlled, just about, but we can see this question has daunted her. She can’t even answer it! Can’t even look at the person she’s talking to. Notice as well that we’re outside quotation marks here – she’s not talking, she’s just looking at something. Writing great dialogue is about those sections of silence too – the bits that happen beyond the quotation marks.]

[ Beat 5: And Lecter immediately calls attention to her reaction, thereby emphasising that he’s observed her and knows what it means.]

Overall, you can see that not one single element of this dialogue leaves the emotional balance unaltered. Every line of dialogue alters the emotional landscape in some way. That’s why it feels so intense & engaging.

Want to achieve the same effect? Just check your own dialogue, line by line. Do you feel that emotional movement there all the time? If not, just delete anything unnecessary until you feel the intensity and emotional movement increase.

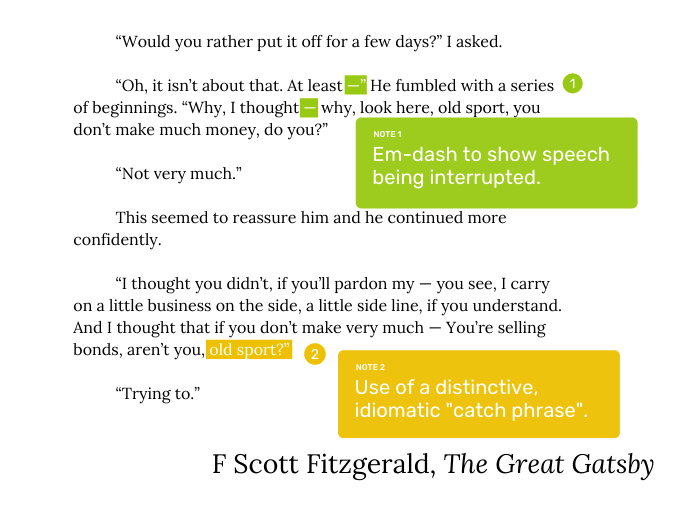

Dialogue Rule 3: Keep It Oblique

One more point, which sits kind of parallel to the bits we’ve talked about already.

If you want to create some terrible dialogue, you’d probably come up with something like this (very similar to my previous bad dialogue example):

“Hey Judy.”

“Hey, Brett.”

“Yeah, not bad. What do you say? Maybe play some tennis later?”

“Tennis? I’m not sure about that. I think it’s going to rain.”

Tell me honestly: were you not just about ready to scream there? If that dialogue had continued like that for much longer, you probably would have done.

And the reason is simple. It was direct, not oblique.

So direct dialogue is where person X says something or asks a question, and person Y answers in the most logical, direct way.

We hate that! As readers, we hate it.

Oblique dialogue is where people never quite answer each other in a straight way. Where a question doesn’t get a straightforward response. Where random connections are made. Where we never quite know where things are going.

As readers, we love that. It’s dialogue to die for.

And if you want to see oblique dialogue in action, here’s a snippet from Aaron Sorkin’s The Social Network . (Because dialogue in screenwriting should follow the same rules as a novel. Some may argue that it should be even more snipped!)

So here goes. This is the young Mark Zuckerberg talking with a lawyer:

Lawyer: “Let me re-phrase this. You sent my clients sixteen emails. In the first fifteen, you didn’t raise any concerns.” MZ: ‘Was that a question?’ L: “In the sixteenth email you raised concerns about the site’s functionality. Were you leading them on for 6 weeks?” MZ: ‘No.’ L: “Then why didn’t you raise any of these concerns before?” MZ: ‘It’s raining.’ L: “I’m sorry?” MZ: ‘It just started raining.’ L: “Mr. Zuckerberg do I have your full attention?” MZ: ‘No.’ L: “Do you think I deserve it?” MZ: ‘What?’ L: “Do you think I deserve your full attention?”

I won’t discuss that in any detail, because the technique really leaps out at you. It’s particularly visible here, because the lawyer wants and expects to have a direct conversation. ( I ask a question about X, you give me a reply that deals with X. I ask a question about Y, and … ) Zuckerberg here is playing a totally different game, and it keeps throwing the lawyer off track – and entertaining the viewer/reader too.

Want to achieve the same effect? Just keep your dialogue not quite joined up. People should drop in random things, go off at tangents, talk in non-sequiturs, respond to an emotional implication not the thing that’s directly on the page – or anything. Just keep it broken. Keep it exciting!

This not only moves the story forward but also says a lot about the character speaking.

Dialogue Rule 4: Reveal Character Dynamics And Emotion

Most writers use dialogue to impart information – it’s a great way of explaining things. But it’s also a perfect (and subtler) tool to describe a character, highlighting their mannerisms and personality. It can also help the reader connect with the character…or hate them.

Let’s take a look here at Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower as another dialogue example.

Here we have two characters, when protagonist Charlie, a high school freshman, learns his long-time crush, Sam, may like him back, after all. Here’s how that dialogue goes:

“Okay, Charlie … I’ll make this easy. When that whole thing with Craig was over, what did you think?”

… “Well, I thought a lot of things. But mostly, I thought your being sad was much more important to me than Craig not being your boyfriend anymore. And if it meant that I would never get to think of you that way, as long as you were happy, it was okay.” …

… “I can’t feel that. It’s sweet and everything, but it’s like you’re not even there sometimes. It’s great that you can listen and be a shoulder to someone, but what about when someone doesn’t need a shoulder? What if they need the arms or something like that? You can’t just sit there and put everybody’s lives ahead of yours and think that counts as love. You just can’t. You have to do things.”

“Like what?” …

“I don’t know. Like take their hands when the slow song comes up for a change. Or be the one who asks someone for a date.”

The words sound human.

Sam and Charlie are tentative, exploratory – and whilst words do the job of ‘turning’ a scene, both receiving new information, driving action on – we also see their dynamic.

And so we connect to them.

We see Charlie’s reactive nature, checking with Sam what she wants him to do. Sam throws out ideas, but it’s clear she wants him to be doing this thinking, not her, subverting Charlie’s idea of passive selflessness as love.

The dialogue shows us the characters, as clearly as anything else in the whole book. Shows us their differences, their tentativeness, their longing.

Want to achieve the same effect? Understand your characters as fully as you can. The more you can do this, the more naturally you’ll write dialogue that’s right for them . You can get tips on knowing your characters here .

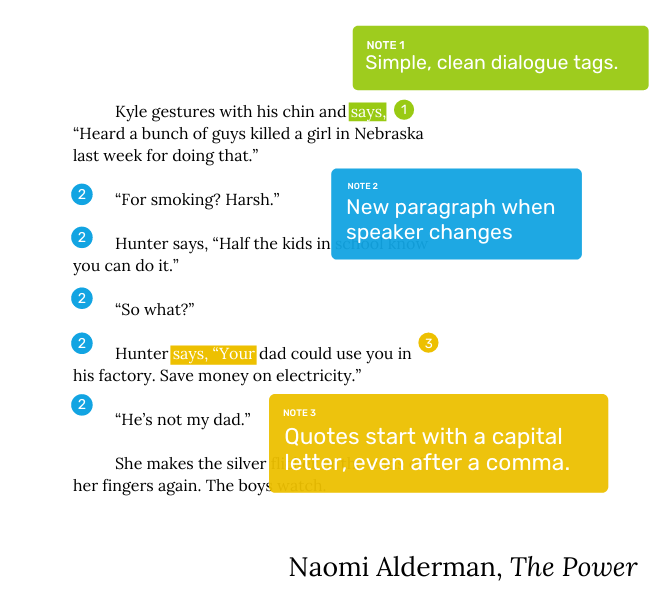

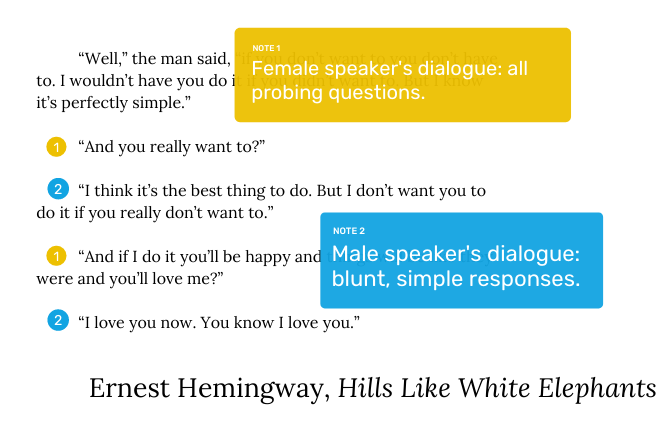

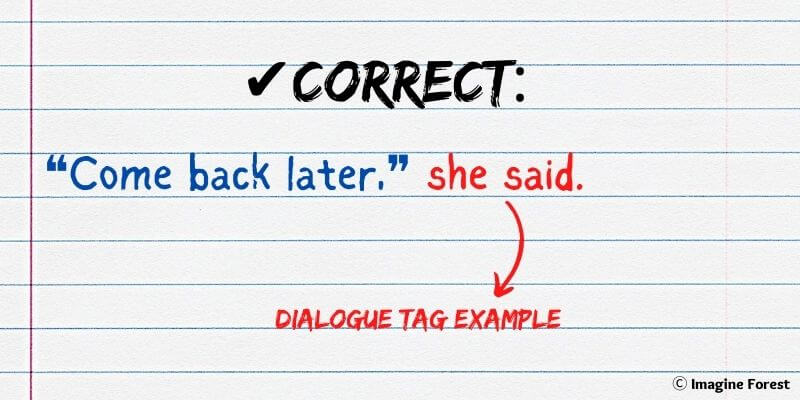

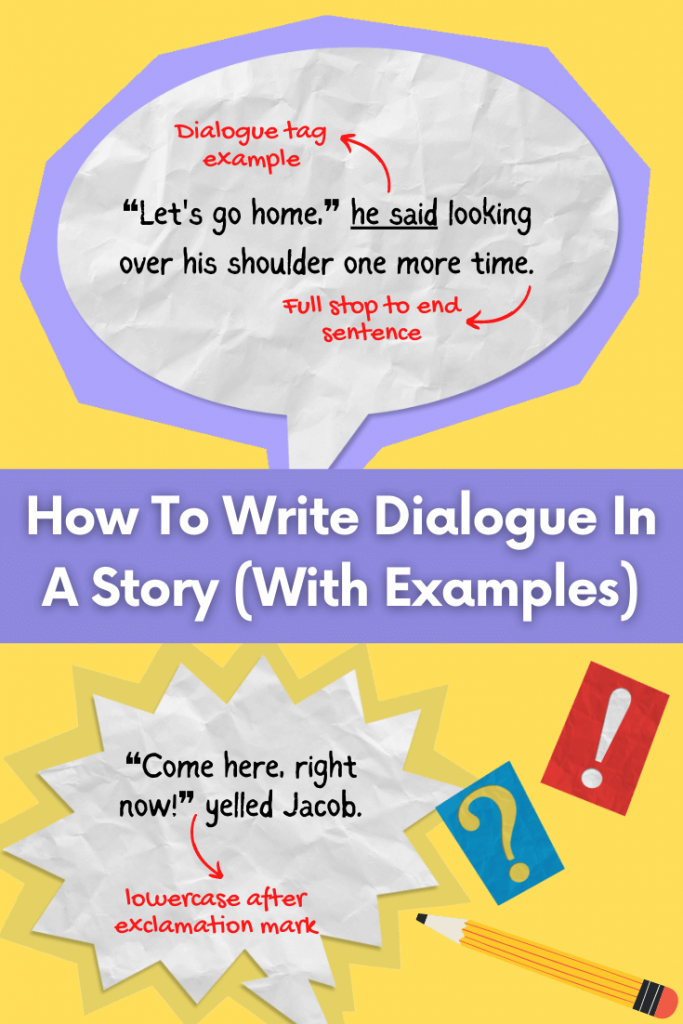

Dialogue Rule 5: Keep Your Dialogue Tags Simple

A dialogue tag is the part that helps us know who is saying what – the he said/she said part of dialogue that helps the reader follow the conversation.

Keep it Simple

A lot of writers try to add colour to their writing by showering it with a lot of vigorous dialogue tags. Like this:

“Not so,” she spat.

“I say that it is,” he roared.

“I know a common blackbird when I see it,” she defended.

“Oh. You’re a professional ornithologist now?” he attacked, sarcastically.

That’s pretty feeble dialogue, no matter what. But the biggest part of the problem is simply that the dialogue tags ( spat, roared , and so on) are so highly coloured, they take away interest from the dialogue itself – and it’s the words spoken by the characters that ought to capture the reader’s interest.

Almost always, therefore, you should confine yourself to the blandest of words:

She answered

And so on. Truth is, in a two-handed dialogue where it’s obvious who’s speaking, you don’t even need the word said .

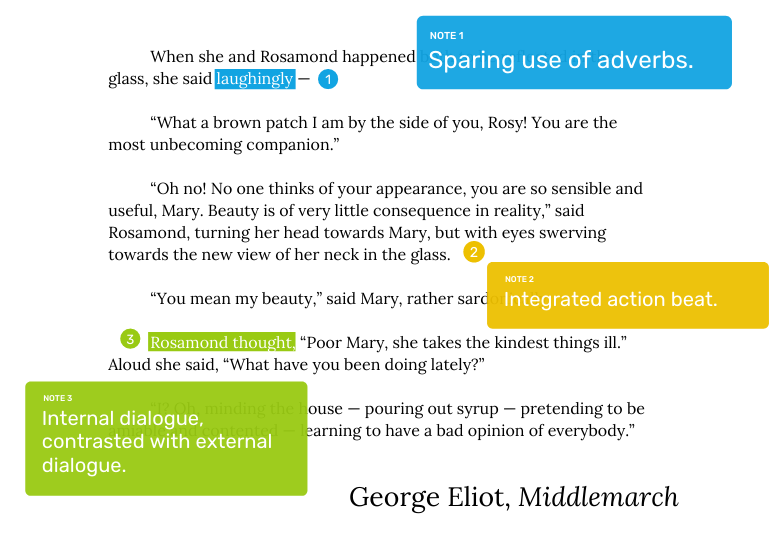

Get Creative

As an alternative, you can have action and body language demonstrate who is saying what and their emotions behind it. The scene description can say just as much as the dialogue.

Here’s another example of the same exchange:

Joan clenched her jaw. “Not so!”

“I say that it is.”

His voice kept rising with every word he shouted, but Joan was not going to be deterred.

“I know a common blackbird when I see it.”

“Oh. You’re a professional ornithologist now?”

Not one dialogue tag nor adverb was used there, but we still know who said what and how it was delivered. And , if you’re really smart and develop how your characters speak (pacing, words, syntax and speech pattern), a reader can know who is talking simply by how they’re talking.

The simple rule: use dialogue tags as invisibly as you can. I’ve written about a million words of my Fiona Griffiths series, and I doubt if I’ve used words other than say / reply and other very simple tags more than a dozen or so times in the entire series.

Keep it simple!

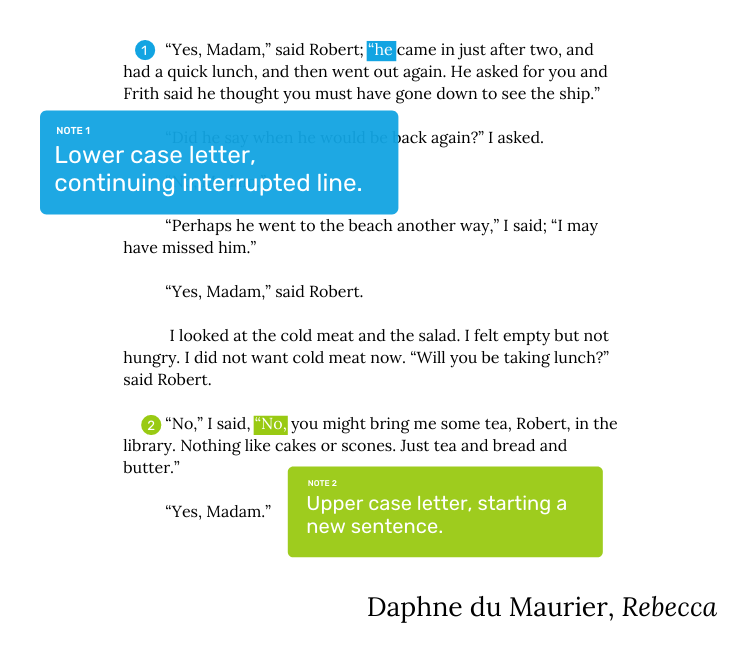

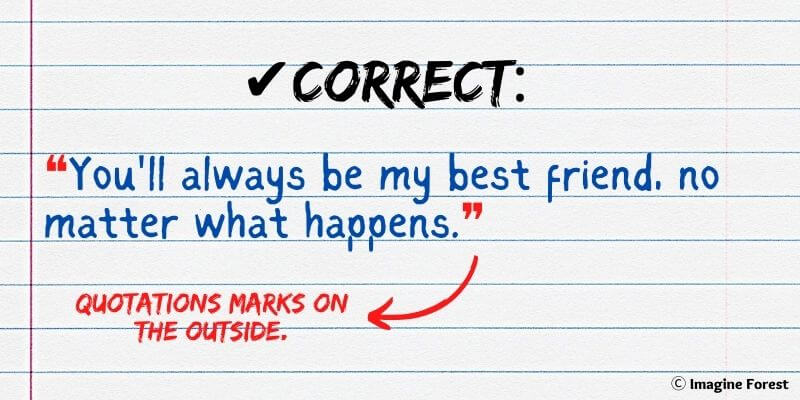

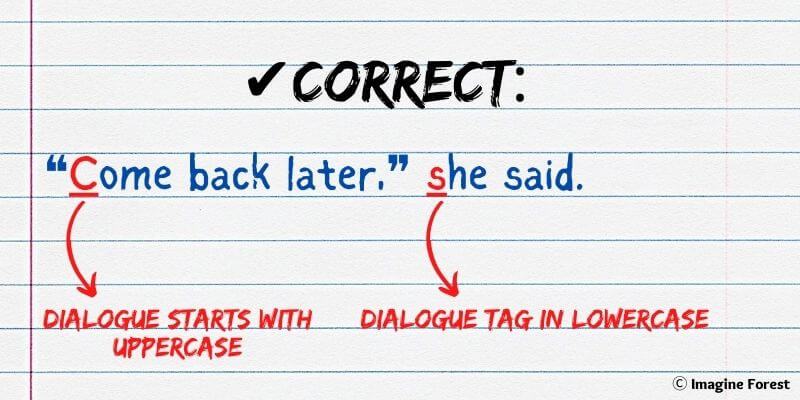

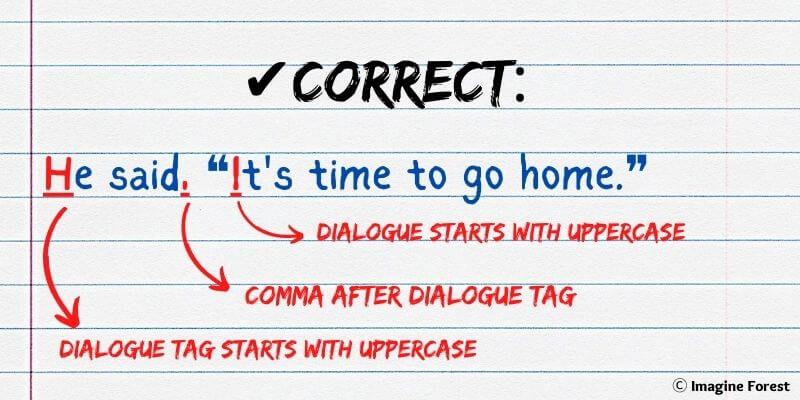

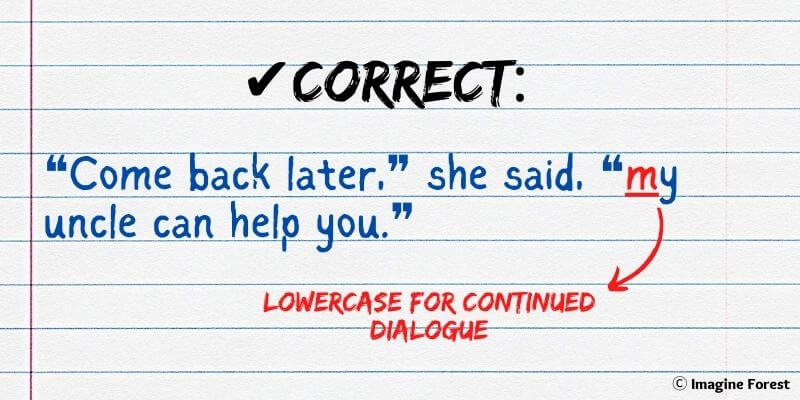

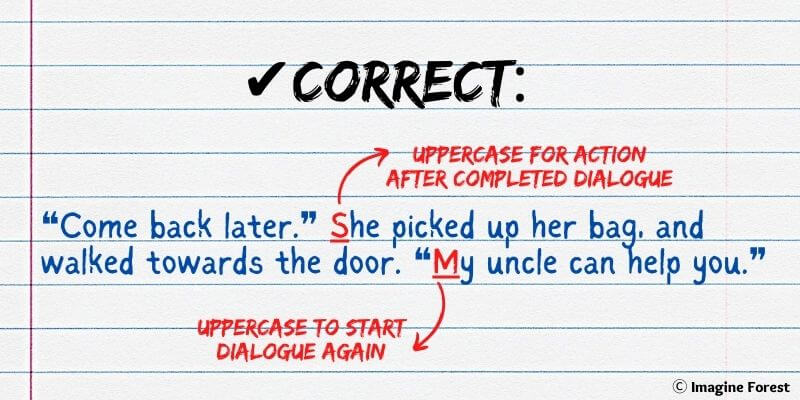

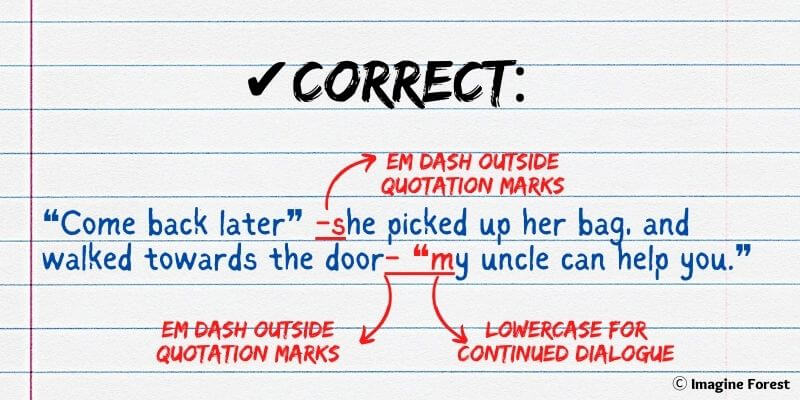

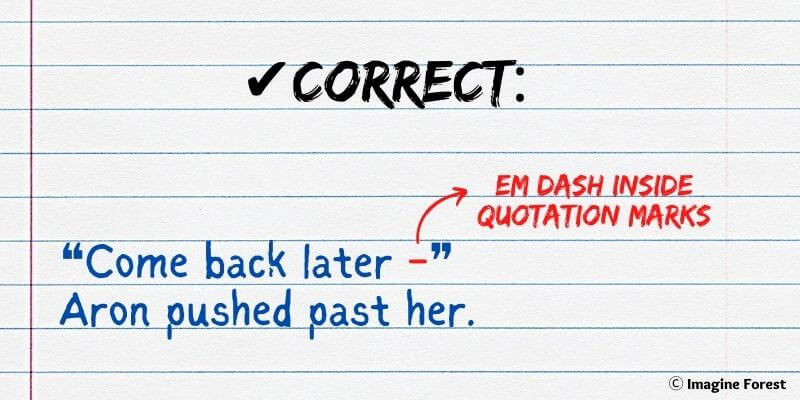

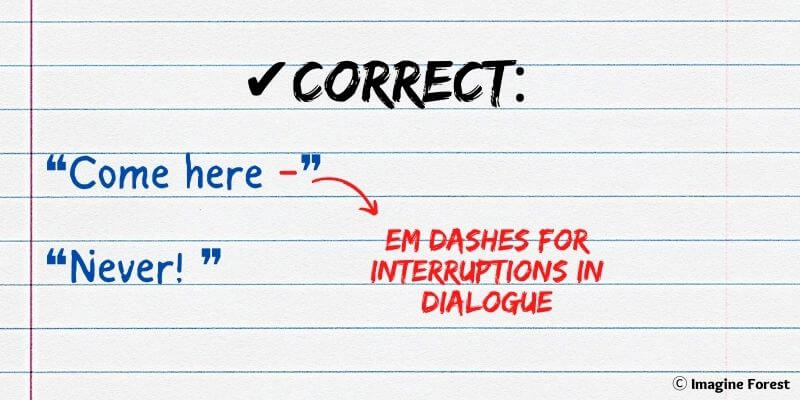

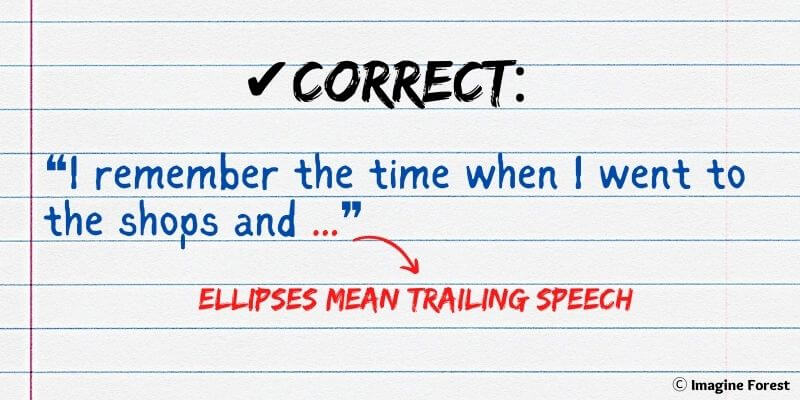

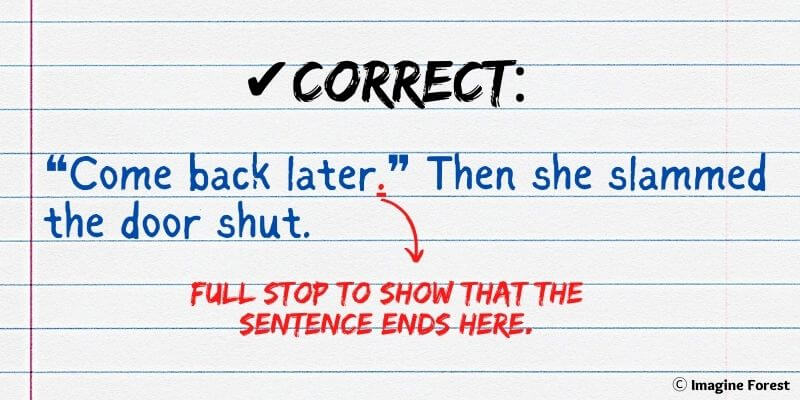

Dialogue Rule 6: Get The Punctuation Right

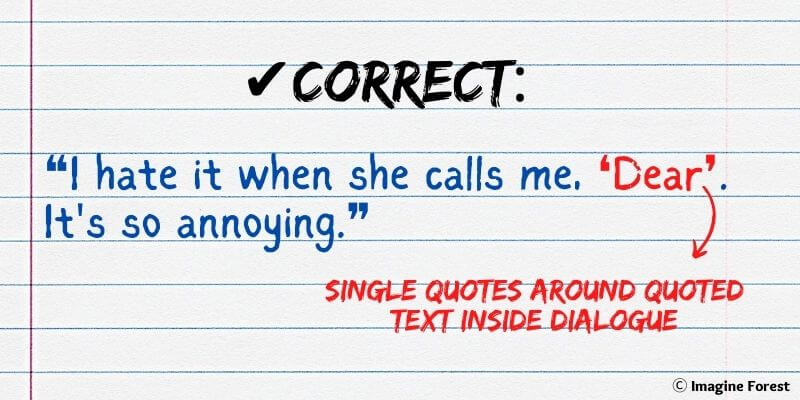

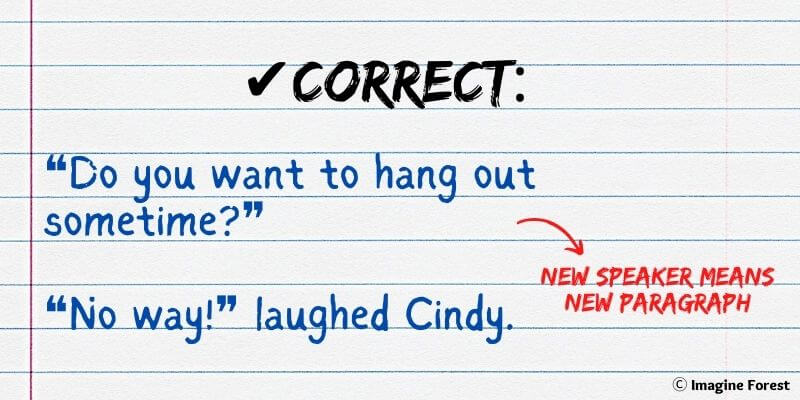

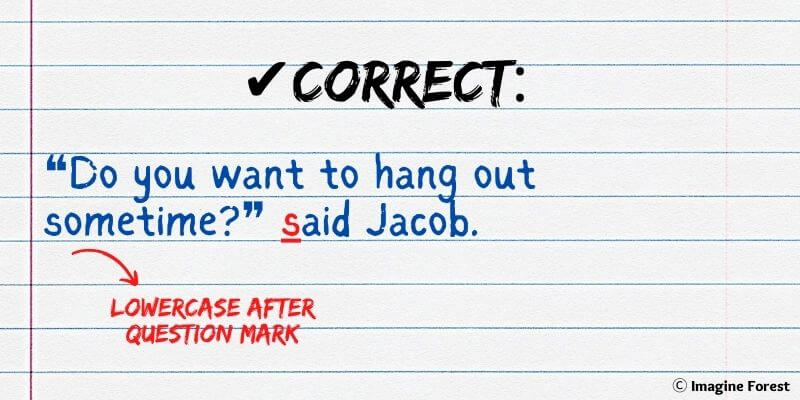

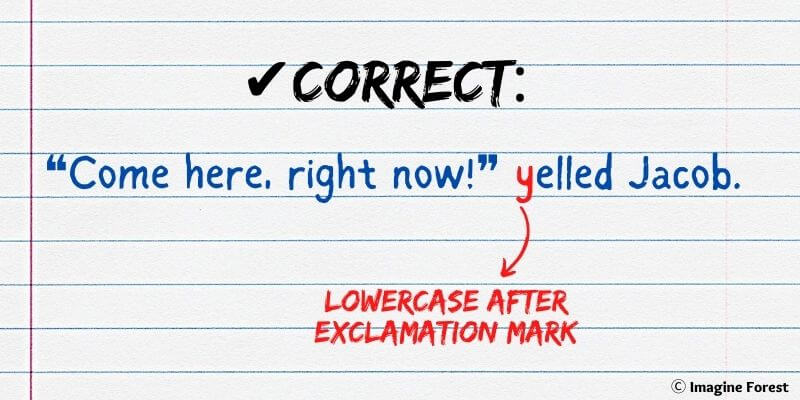

Dialogue punctuation is so simple and important, and looks so bad if you get it wrong. Here are eight simple rules to know before your character starts to speak:

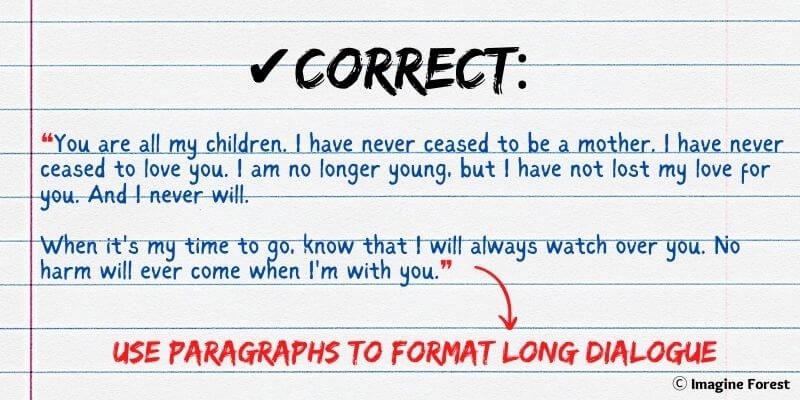

- Each new line of dialogue (i.e: each new speaker) needs a new paragraph – even if the dialogue is very short.

- Action sentences within dialogue get their own paragraphs too. The first paragraph of a chapter or section starts on the far left, and the next paragraph (whether it starts with dialogue or not) is indented.

- The only exception to this rule is if the sentence interrupts an otherwise continuous piece of dialogue. for example: “Yes,” she said. She brushed away a fly that had landed on her cheek. “I do think hippos are the best animals.”

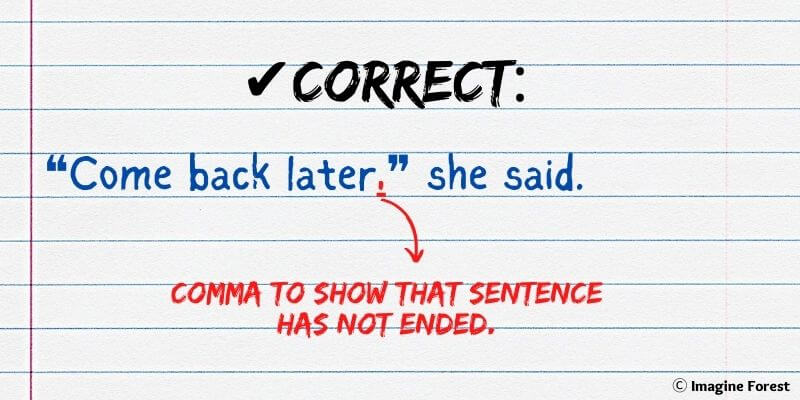

- When you are ending a line of dialogue with he said / she said , the sentence beforehand ends with a comma not a full stop (or period), as in this for example: “Yes,” she said.

- If the line of dialogue ends with a question mark or exclamation mark, you still don’t have a capital letter for he said / she said . For example: “You like hippos?” he said .

- If the he said / she said lives in the middle of one continuous sentence of dialogue, you need to deploy those commas like a comma-deploying ninja. Like this for example: “If you like hippos,” he said, “then you deserve to be sat on by one.”

- And use quotation marks, dummy. You know to do that, without me telling you, right? (Yes, yes, some serious writers of literary fiction have written entire novels without one speech mark – but they are the exception to the rule.)

- Use the exclamation point sparingly. Otherwise! Your! Book! Is! Going! To! Sound! Very! Hysterical!

Dialogue Rule 7: Accents And Verbal Mannerisms

Realistic dialogue is important, but writing dialogue is not the same as speaking. Remember that the reader’s experience has to be smooth and enjoyable, so even if your character has an accent, speech impediment, or talks excessively…writing it exactly as it’s spoken doesn’t always work.

If you want to show that your character is from a certain part of the UK, it often helps to add a smattering of colloquial words or

In The Last Thing To Burn by Will Dean, the antagonist, Len, has an accent (Yorkshire or Lancashire, it’s obvious but never stated). The protagonist is trapped inside this man’s home, she has no idea where she is, but by describing the endless fields and hearing his subtle accent the reader knows exactly where in the UK she’s trapped.

Len says things like:

‘Going to go feed pigs’ and ‘There’s a good lass.’

You can highlight location, a character’s age, and their social standing simply by giving a nod to their accent.

On the flip-side, if they have a foreign accent, it can sometimes be too jarring to write dialogue exactly as it sounds.

‘Amma gonna eata the pizza’ is an awful way to write an Italian accent – it’s verging on racist. Try to avoid that. Instead, simply mention they have an Italian accent and let the reader fill in the blanks.

Accents Written Well

But, of course, there’s always an exception!

Irvine Welsh writes English in his native Scottish dialect and it’s exemplary – but nothing something we would recommend for a novice writer.

Here’s an excerpt from Trainspotting:

Third time lucky. It wis like Sick Boy telt us: you’ve got tae know what it’s like tae try tae come off it before ye can actually dae it. You can only learn through failure, and what ye learn is the importance ay preparation. He could be right. Anywey, this time ah’ve prepared.

Perhaps, if you have a Scottish character in your novel you may want them to speak in a strong accent. But getting it wrong can ruin an entire novel, so unless you are very skilled and very confident, stick to the odd colloquialism or word and leave it there.

Verbal Mannerisms

Whether you realise it or not, we all have speech patterns. Some of us speak slowly, others pause, people also trail off mid-sentence. Some people also use verbal mannerisms, such as adding a word to a sentence that is unnecessary but becomes a personal tic (such as ‘man’, ‘like’ or ‘innit’). Or repeat favourite words. These can be influenced by age, background, class, and the period in which the book is set.

Here’s an example of two people talking. I won’t mention their ages or backgrounds, but see if you can guess.

“Chill, Bro.”

“Chill? I’m far from chilled, you scoundrel. That’s my flower bed you’ve just dug up.”

“I found something, though. It was sticking out the ground.”

“Outrageous behaviour. So… You… One simply can’t go around digging up people’s gardens!”

“Yeah. And what?” They both stared down at the swollen white lumps pressing out of the soil like plump snowdrops.”What is it, though?”

Harold swallowed. “Fingers.”

A Few Last Dialogue Rules

If want some great examples of how to write in dialogue, read plays or screenplays for inspiration. Read Tennessee Williams or Henrik Ibsen. Anything by Elmore Leonard is great. Ditto Raymond Chandler or Donna Tartt.

Some last tips:

- Keep speeches short . If a speech runs for more than three sentences or so, it (usually) risks being too long. Break it up with some action or someone else talking.

- Ensure characters speak in their own voice . And make sure your characters don’t sound the same as each other. Remember mannerisms, speech patterns, and how age and background influences speech.

- Add intrigue . Add slang and banter. Lace character chats with foreshadowing. You needn’t be writing a thriller to do this.

- Get in late and out early. Don’t bother with small talk. Decide the point of each interaction, begin with it as late as possible, ending as soon as your point is made.

- Interruption is good. So are characters pursuing their own thought processes and not quite engaging with the other.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 5 typesetting rules of writing dialogue.

Part of the editing process is to ensure you format dialogue correctly. Formatting dialogue correctly means remembering 5 simple steps:

- Only spoken words go within quotation marks.

- Use a separate sentence for every new thing someone says or does.

- Punctuation marks stay inside quotation marks and don’t forget about closing quotation marks at the end of the sentence.

- You can use single quotation marks or double quotation marks – but you must be consistent!

- Beware of capital letters. Always at the start of a sentence and after the quotations mark.

How Can You Use Everyday Life To Perfect Your Dialogue?

Listening to people speak will really help you perfect good dialogue. Sit in a cafe and people watch. Watch their body language and how they express themselves. Their verbal mannerisms, tics, how they choose their words, the syntax, speech patterns and turns of phrase. Make notes (without being spotted) and look out for contrasting word choices and personas.

What Is A Bad Example Of Dialogue?

There are plenty to choose from above – but the worst things you can do include:

- Using too many words

- Writing an accent how it’s heard (unless you are Irvine Welsh, which most people are not)

- Writing dialogue that’s irrelevant or misleading

- Using too many dialogue tags (or none at all)

- Bad punctuation – remember dialogue formatting

- Avoid long speeches

How Do You Start Dialogue?

There are many ways to start dialogue. You can ease into it, by introducing the character to the scene. Or you can jump in median res, slap bang into the centre of the action. Much like life, sometimes we hear a person’s voice before we see them – they pop up out of nowhere – and sometimes we call them or walk into a room where they are, and we have rehearsed what we plan to say.

See what works best for your scene, your characters, and the genre you are writing in (dialogue in a crime thriller will sound very different to dialogue in a young adult novel, for instance).

That’s All I Have To Say About That

We really hope you have found this article interesting and that you have now found the confidence to tackle the dialogue in your novel.

What your characters say and how they say it can make the difference between a good book and one that everyone is talking about. So get eavesdropping, get practising, and read as many books and plays as you can to create better dialogue.

Practice makes perfect and don’t forget to enjoy yourself!

About the author

Harry has written a variety of books over the years, notching up multiple six-figure deals and relationships with each of the world’s three largest trade publishers. His work has been critically acclaimed across the globe, has been adapted for TV, and is currently the subject of a major new screen deal. He’s also written non-fiction, short stories, and has worked as ghost/editor on a number of exciting projects. Harry also self-publishes some of his work, and loves doing so. His Fiona Griffiths series in particular has done really well in the US, where it’s been self-published since 2015. View his website , his Amazon profile , his Twitter . He's been reviewed in Kirkus, the Boston Globe , USA Today , The Seattle Times , The Washington Post , Library Journal , Publishers Weekly , CulturMag (Germany), Frankfurter Allgemeine , The Daily Mail , The Sunday Times , The Daily Telegraph , The Guardian , and many other places besides. His work has appeared on TV, via Bonafide . And go take a look at what he thinks about Blick Rothenberg . You might also want to watch our " Blick Rothenberg - The Truth " video, if you want to know how badly an accountancy firm can behave.

Most popular posts in...

Advice on getting an agent.

- How to get a literary agent

- Literary Agent Fees

- How To Meet Literary Agents

- Tips To Find A Literary Agent

- Literary agent etiquette

- UK Literary Agents

- US Literary Agents

Help with getting published

- How to get a book published

- How long does it take to sell a book?

- Tips to meet publishers

- What authors really think of publishers

- Getting the book deal you really want

- 7 Years to Publication

Get to know us for free

- Join our bustling online writing community

- Make writing friends and find beta readers

- Take part in exclusive community events

- Get our super useful newsletters with the latest writing and publishing insights

Or select from our premium membership deals:

Premium annual – most popular.

per month, minimum 12-month term

Or pay up front, total cost £150

Premium Flex

Cancel anytime

Paid monthly

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cfduid | 1 month | The cookie is used by cdn services like CloudFare to identify individual clients behind a shared IP address and apply security settings on a per-client basis. It does not correspond to any user ID in the web application and does not store any personally identifiable information. |

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| JSESSIONID | Used by sites written in JSP. General purpose platform session cookies that are used to maintain users' state across page requests. | |

| PHPSESSID | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. | |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by CloudFare. The cookie is used to support Cloudfare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _gat | 1 minute | This cookies is installed by Google Universal Analytics to throttle the request rate to limit the colllection of data on high traffic sites. |

| GCLB | 12 hours | This cookie is known as Google Cloud Load Balancer set by the provider Google. This cookie is used for external HTTPS load balancing of the cloud infrastructure with Google. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

| _hjFirstSeen | 30 minutes | This is set by Hotjar to identify a new user’s first session. It stores a true/false value, indicating whether this was the first time Hotjar saw this user. It is used by Recording filters to identify new user sessions. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| NID | 6 months | This cookie is used to a profile based on user's interest and display personalized ads to the users. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _hjAbsoluteSessionInProgress | 30 minutes | No description |

| _hjid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Hotjar. This cookie is set when the customer first lands on a page with the Hotjar script. It is used to persist the random user ID, unique to that site on the browser. This ensures that behavior in subsequent visits to the same site will be attributed to the same user ID. |

| _hjIncludedInPageviewSample | 2 minutes | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_cookie_expiry | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_landing | 3 months | No description |

| afl_wc_utm_sess_visit | 3 months | No description |

| CONSENT | 16 years 8 months 4 days 9 hours | No description |

| InfusionsoftTrackingCookie | 1 year | No description |

| m | 2 years | No description |

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

Hannah Yang

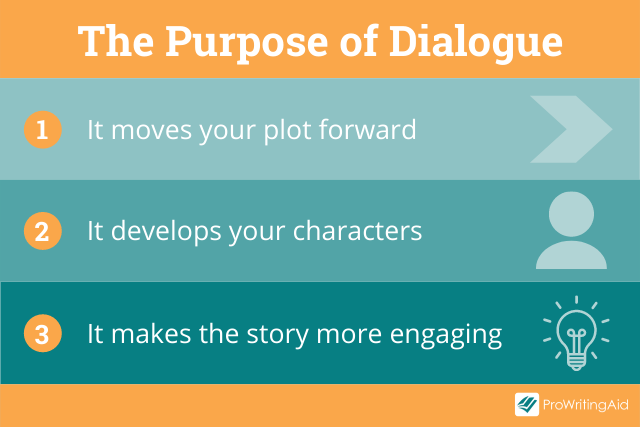

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue , let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

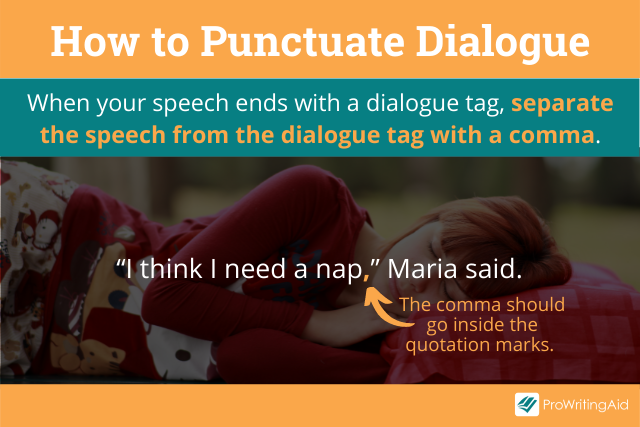

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

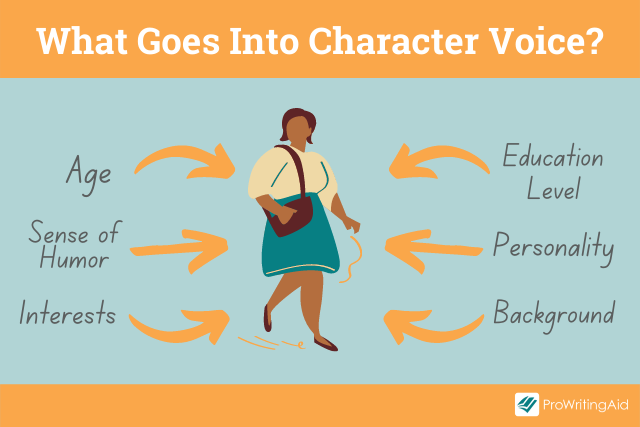

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

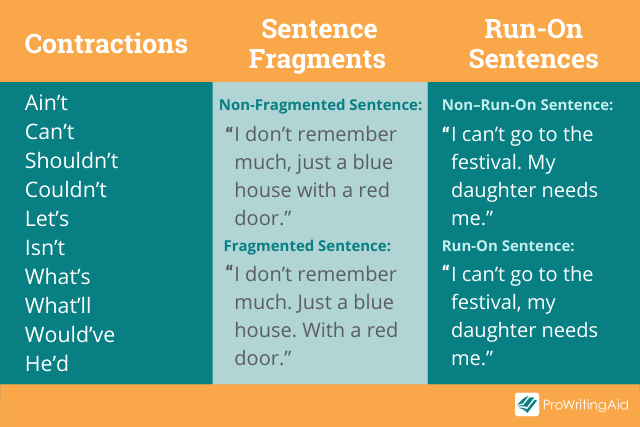

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

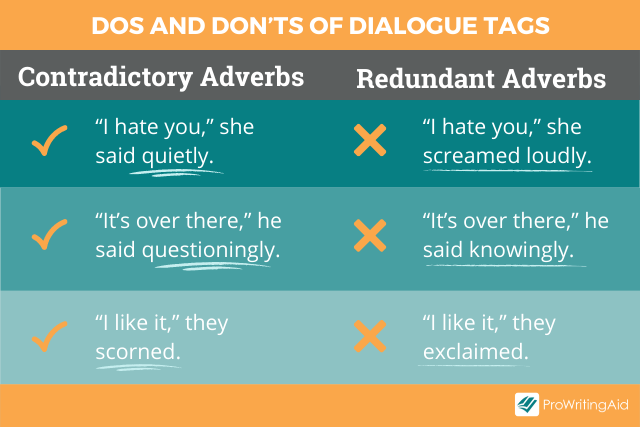

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

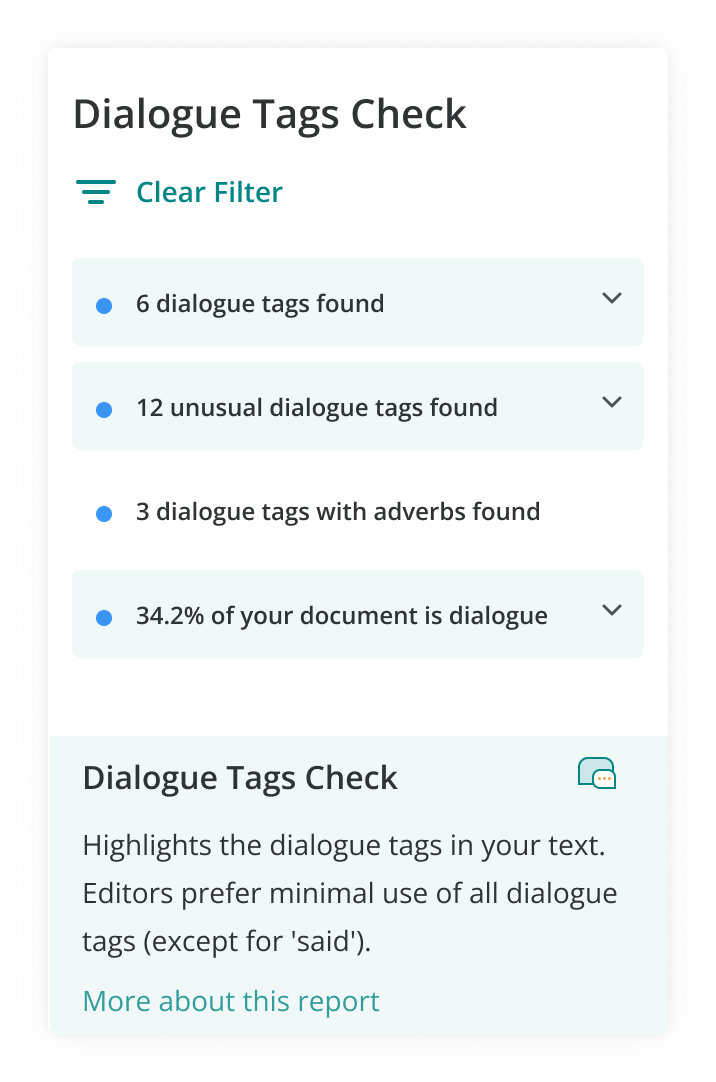

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

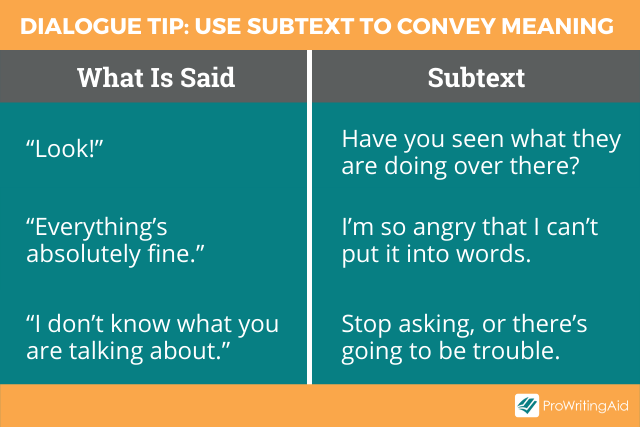

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

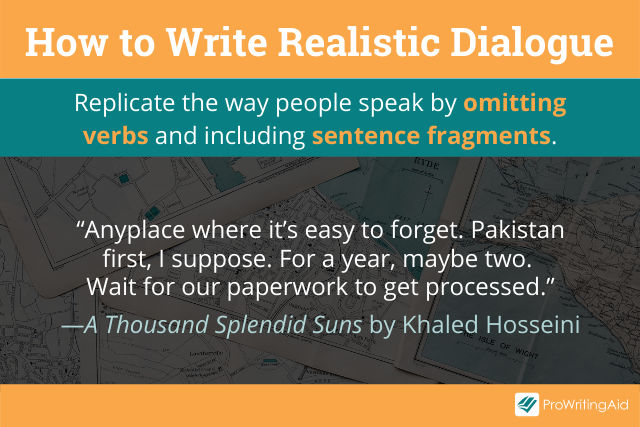

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundamentals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

How to Write Dialogue: 3 Effective Ways to Write Dialogue

Learning how to write dialogue is one of the hardest things to write well, but it’s also vital to telling an impactful story.

If you’re writing a novel or even if you're writing a nonfiction book , nailing dialogue is key to maintaining tone, characterization, and pacing in your story.

We’re going to go over what dialogue is, how to hit it out of the park, and tips that you can apply to your own stories–no matter what genre you’re writing in!

This guide teaches how to write a dialogue, including:

What is dialogue?

Dialogue is defined as a conversation between two or more characters in a written work, be that a play, book, movie, or stage production. That’s it–if you’ve got characters in your story and they’re having a spoken conversation, you’ve got dialogue.

Here’s an example of a dialogue exchange between two imaginary characters: “How’s it goin’?” Smith asked.

Rosa sighed. “I suppose I’m alright, but I’ve had a dreadful day.”

“Aw, that’s too bad. C’mon, let’s get milkshakes.”

As in the example above, quotation marks are often used to notate dialogue, but not always.

Some authors like James Joyce and Cormac McCarthy take the stylistic liberty of removing the quotation marks from their dialogue.

Here’s an example of dialogue without quotation marks from McCarthy’s novel, The Road.

Hi, Papa, he said.

I'm right here.

Without the quotation marks, the reader uses context and voice to determine who’s talking, which we’ll talk about in more detail later on.

For new writers, it’s generally best to keep the quotations in, as it can become confusing to readers to take out punctuation without a clear reason for doing so.

How to write dialogue

So, a conversation between characters. Easy, right?

Many people think that learning how to write a dialogue is as simple as writing a descriptive paragraph about a character's appearance or even writing about the thoughts they are having in their head. But it's more than that.

If you've ever set down to write a dialogue and make it sound authentic, you already know that writing a conversation between multiple characters can be strangely challenging. So, now that we’ve talked about what dialogue is and what it’s for, let’s talk about how to write dialogue that actually sounds real – and true to your characters.

Related: Narrative Writing Prompts

1. Mimic real people… sort of

Your characters should be fleshed out like real people, regardless of your genre, and they should act like real people in your story. By extension, they should also talk like real people.

What’s the most effective way to convey dialogue that’s realistic? Mimic real conversations.

Sort of.

See, you should indeed listen to people talking to get an idea of how conversations flow, nonverbal cues, and voice. But if you were to write down word-for-word a conversation between two people, you’d likely find that it’s incoherent.

But real-world conversations go in circles, dive off on tangents, and ramble. Unless that's a character trait you want to intentionally include, we don’t want that stuff in our fiction.

Not sure what I mean?

Go listen in to a conversation at your local coffee shop. Listen to how often someone gets interrupted or goes on a separate tangent.

So yes, DO listen to real-world conversations for flow and voice to learn how to write dialogue like a pro. Different people from different backgrounds notice and observe things in unique ways. And this has the ability to enhance your characters' dialogue.

But pay attention to what can be cut out of those conversations.

Then, find the best of both worlds. Take the body language, flow, and distinct voice from real-world conversations and apply them to fiction. Omit the changes in structure and lack of clarity that simply won't enhance your writing.

It’s a tough balancing act, but it makes for dynamic, realistic dialogue.

Related: 4 Ways to Improve Your Writing Skills

2. Give each character a distinct voice

Like we mentioned before, it’s important to use real-world examples of conversations to help you understand how to get across a character’s voice.

But what is their voice?

In this section, we aren’t talking about narrative voice or even the tones in your writing . The narrative voice is the prose itself, the narrative point of view that describes the events happening. Here, we’re talking about the voice that individual characters have.

Let’s look at the example we used earlier when we discussed quotation marks.

“How’s it goin’?” Smith asked.

Rosa sighed. “I suppose I’m alright, but I’ve had a dreadful day.”

These two characters have very different voices. The first speaker, Smith, uses slang and abbreviations when he talks. His manner of speech is much more casual and laid-back. Rosa, on the other hand, uses words with a more formal inflection. ‘Dreadful’ and ‘suppose’ point to someone who’s more uptight, more verbose.

Without any extra background information on either character, we already have an idea of what they’re like based on their voice. And when we get to the last line, we know that it’s Smith talking, because it matches up with the voice we’ve established on the first line.

One common mistake new writers make is having all their characters sound the same.

But people aren’t like that! Your characters are all different, unique people, and they should sound like it. A kid who grew up lower class in a big city will talk differently than a wealthy kid from a suburban town. A serf from the countryside won’t talk the same way as the king.

Ideally, you should know which character is speaking based solely on the way they’re talking.

Consider who your characters are. Where did they grow up? Who do they hang out with? What are the sorts of things they prioritize, and how does that impact not only what they talk about, but how they talk about it?

3. Think about how the conversation moves the story forward

We talked about how learning how to write dialogue in fiction shouldn’t necessarily mirror the chaotic structure of real-world conversations. It needs to be believable, but in, truth, it will be more structured and planned.

Basically, this means you should treat your dialogue the same way you treat everything else in your story: it should serve a purpose, it should move the storyline forward, and it should be interesting.

Dialogue should happen for a reason. It should be motivated.

Characters should have a reason to talk–this might sound obvious, but failing to recognize this can result in some clunky dialogue.

Take exposition, for example.

A common exposition mistake new writers make is having their characters deliver exposition–especially in fantasy, when the author is trying to impart details about their world to the reader.

Let’s take a look at an imaginary dialogue exchange:

“We’re having wonderful weather,” Ava said.

Ned nodded. “We always have wonderful spring weather. Our two suns make it so that it never gets too cold here on our planet, and our spring seasons are long and prosperous.”

Take a look at Ned’s dialogue. If these characters are from this planet, they wouldn’t be talking like this. And even if they are, the sentence reads flat and stilted, more like an excerpt from an encyclopedia than a piece of dialogue.

When you’re writing dialogue, consider what it is that the characters are trying to convey. If you’re just using them as a mouthpiece for your own exposition, maybe reconsider.

It’s also okay to skip over some character interactions. You don’t have to document every single minute of an exchange. Instead of typing out everything two people say, stick to the specific interactions that have to do with the plot.

We’ll talk more about small talk later, but as a rule of thumb for fiction that also applies to dialogue: if you’re bored writing it, the reader’s probably bored reading it. Keep your dialogue motivated and important.

4. Cut the small talk

This one builds on point three of learning how to write a dialogue. But we're going to stay here a bit because it's important – and because a common mistake of new authors is including too much small talk in their novel.

When learning how to write dialogue, just remember that small talk is not necessary (and doesn't make for great writing).

When people get together, especially strangers, there’s often small talk involved. True. We ask each other questions about the weather and make idle conversation to break the ice for more important topics.

But this is fiction. And in fiction, we get to skip all that! Yay!

We don’t need to read every word your characters say to each other when they meet up. We don’t need to hear them describe the weather to each other, or try to talk about sports. Unless it’s absolutely vital to the scene, we don’t need to hear about it.

5. Remember to indent for clarity

This may seem like a simple thing, but your book formatting matters hugely when it comes to dialogue.

New authors often don’t know when to hit enter and start a new paragraph, and this can result in long paragraphs where multiple people are talking.

It becomes unclear who is saying what.

Plus, usually, long paragraphs make reading retention difficult.

There’s a simple rule of thumb to keep in mind: you should start a new paragraph when a new idea is introduced.

Let’s reference a quick made-up example:

“I don’t know where he went,” said Clark. “Well, he couldn’t have gone far,” said Synthia. She looked over her shoulder. “Elizabeth! Do you know where Matt went?” “No,” said Elizabeth. “Drat.” Clark folded his arms.

We have four characters here, three whom are in the scene. The lines of dialogue aren’t correctly spaced out, so it’s difficult to tell who’s talking – and when. On the last line, it’s entirely unclear who says “drat,” for example.

So how do we fix this? Simple! Just add a new paragraph break every time a new character speaks.

“I don’t know where he went,” Clark said.

“Well, he couldn’t have gone far,” said Synthia. She looked over her shoulder. “Hey, Elizabeth! Do you know where Matt went?”

“No,” said Elizabeth.

“Drat.” Clark folded his arms.

Because we’ve properly spaced out our dialogue, we can now clearly see who’s saying what. Not only that, but having it formatted like this is just plain easier on the eyes, and much more inviting to a reader than a block of text.

Don’t make it harder than it has to be! Format your dialogue correctly.

6. Be careful with dialogue tags

Dialogue tags are super important. They let us know who’s talking, and they offer a space for characters to move around during conversations.

But abusing them can ruin the flow of dialogue. For example, let’s look at this exchange:

“I can’t believe it,” Dennis said.

“I thought you knew,” Sandra said.

“I thought you loved me!” Dennis said.

“I do still love you,” Sandra said.

In this example, overusing the same dialogue tag and format makes the exchange dull when it should be dramatic.

If you have two characters talking for a prolonged period of time, try dropping dialogue tags altogether and punctuating with action to pack a bigger punch.

Let’s try that exchange again, but with a little more attention to dialogue tags:

Dennis balled his fists. “I can’t believe it.”

“I thought you knew.” Sandra blinked back tears.

“I thought you loved me!”

“I do still love you.”

Taking out those dialogue tags makes the dialogue read much more smoothly, and the addition of action beats helps set the tone so the words themselves can carry more weight.

Try practicing with removing your dialogue tags and letting your character’s voices and actions drive the scene!

7. Approach accents and foreign languages with caution

Before we wrap up, let’s touch briefly on accents and foreign languages. This is especially important when it comes to learning how to write dialogue, but most people miss the mark on this one.

First, accents.

There’s a lot of debate surrounding accents. Some people believe they can be spelled phonetically, and some believe they should never be spelled out, ever.

This depends largely on your story and on what the spelling achieves–if every character has an accent, for example, reading it spelled phonetically might become cumbersome to read. If only one character has a few lines in an accent, that might be less pervasive, but it might still be confusing or unintentionally comical.

For an alternative to spelling out accents, try introducing the character’s accent when you introduce the character. For example:

“Good morning,” John said. He spoke with a bright Irish accent. “How are you?”

Another point of controversy is how foreign languages should be handled in dialogue: specifically, many writers wonder whether they ought to italicize words in other languages.

This is a huge and ongoing debate, so we won’t get into all of it here, but if you’re wondering which route to take, do some research and reading within your genre to see what the conventions are, and why those conventions exist, so you can make an informed decision.

Go write some dialogue!

Whatever your genre, keeping these tips and tricks in mind will help you make your dialogue shine.

If you’re a new writer, hopefully this has given you a great jumping-off point to improve your prose, and if you’re a seasoned expert, we hope you’ve found some great tips and tricks to take your dialogue up a notch.

Protagonist vs Antagonist: The Difference Explained

What is a Biography? Definition, Elements, and More

Editorial, Writing

25 Personification Examples for Writers: What It Is & How to Use It

Fiction, Learning, Writing

Join the Community

Join 100,000 other aspiring authors who receive weekly emails from us to help them reach their author dreams. Get the latest product updates, company news, and special offers delivered right to your inbox.

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jul 24, 2023

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.” She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words. “It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?” “Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late , the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice , we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?” Mr. Bennet replied that he had not. “But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.” Mr. Bennet made no answer. “Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently. “You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.” This was invitation enough. “Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships .

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.