- Pronunciation

- Try to pronounce

- Collections

- Translation

Learn how to pronounce literature

- Very difficult

Show more fewer Voices

IPA : ˈlɪt(ə)rəʧə

Have you finished your recording?

Phonetic spelling of literature

l-it-er-at-ure 0 rating rating ratings Sibyl Dibbert lit-er-a-ture 0 rating rating ratings Otilia Zemlak lit-er-a-ture 0 rating rating ratings Private lit-er-uh-cher -2 rating rating ratings Stanford Wolf

Thanks for contributing

You are not logged in..

Please Log in or Register or post as a guest

Meanings for literature

Show more fewer Meanings

Synonyms for literature

Show more fewer Synonyms

Learn more about the word "literature" , its origin, alternative forms, and usage from Wiktionary.

Quiz on literature

{{ quiz.name }}

{{ quiz.questions_count }} Questions

Show more fewer Quiz

Collections on literature

-{{collection.uname}}

Show more fewer Collections

Examples of in a sentence

Show more fewer Sentence

literature should be in sentence

Translations of literature

Show more fewer Translation

Add literature details

literature pronunciation with meanings, synonyms, antonyms, translations, sentences and more

Which is the right way to pronounce the ambiguous, popular collections, manchester united players list 2020, dutch vocabulary, world's most dangerous viruses, pandemics before covid 19, olympique lyon squad / player list 2020-21, popular quizzes.

Trending on HowToPronounce

- Zac efron [en]

- Nicole kidman [en]

- tatiana [en]

- Joe Biden [en]

- Callum [en]

- Nebuzaradan [en]

- guyana [en]

- micron [en]

- Lizzy Musi [en]

- Clinton Kane [en]

- Kvaratskhelia [en]

Word of the day

Latest word submissions, recently viewed words, flag word/pronunciation, create a quiz.

How to pronounce literature

Listened to: 4.2M times

- advertising

8 votes Good Bad

Add to favorites

Download MP3

User information

4 votes Good Bad

-1 votes Good Bad

-2 votes Good Bad

13 votes Good Bad

11 votes Good Bad

6 votes Good Bad

5 votes Good Bad

1 votes Good Bad

0 votes Good Bad

3 votes Good Bad

literature example in a phrase

He studied Spanish language and literature at university.

The author's magnificent prose was awarded with a top literature prize

Moby-Dick was hailed as one of the literary masterpieces of American and world literature .

there is no basis in the scientific literature to support the cited numbers

Since he won that literature prize he has become the big man on campus!

Definition of literature

- creative writing of recognized artistic value

- the humanistic study of a body of literature

- published writings in a particular style on a particular subject

Synonyms of literature

- printed matter pronunciation printed matter [ en ]

- material pronunciation material [ en ]

- account pronunciation account [ en ]

- passage pronunciation passage [ en ]

- excerpt pronunciation excerpt [ en ]

- reading pronunciation reading [ en ]

- poetry pronunciation poetry [ en ]

- journalism pronunciation journalism [ en ]

- writing pronunciation writing [ en ]

Can you pronounce it better? Or with a different accent? Pronounce literature in English

Accents & languages on maps

- Record pronunciation for literature literature [ en - usa ]

Random words: vase , language , stupid , and , cunt

How to pronounce

- Worcestershire

- Charcuterie

- General Tso

- Saoirse Ronan

Literature - pronunciation: audio and phonetic transcription

American english:.

British English:

[ˈlɪtrətʃə] ipa, /litruhchuh/ phonetic spelling.

Watch my latest YouTube video "Don't use a dictionary when you learn a language!"

Practice pronunciation of literature and other English words with our Pronunciation Trainer. Try it for free! No registration required.

American English British English

Do you learn or teach English?

We know sometimes English may seem complicated. We don't want you to waste your time.

Check all our tools and learn English faster!

Add the word to a word list

Edit transcription, save text and transcription in a note, we invite you to sign up, check subscription options.

Sign up for a trial and get a free access to this feature!

Please buy a subscription to get access to this feature!

In order to get access to all lessons, you need to buy the subscription Premium .

Phonetic symbols cheat sheet

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of literature noun from the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

Join our community to access the latest language learning and assessment tips from Oxford University Press!

- 2 literature (on something) pieces of writing or printed information on a particular subject I've read all the available literature on keeping rabbits. sales literature

- write/publish literature/poetry/fiction/a book/a story/a poem/a novel/a review/an autobiography

- become a writer/novelist/playwright

- find/have a publisher/an agent

- have a new book out

- edit/revise/proofread a book/text/manuscript

- dedicate a book/poem to…

- construct/create/weave/weave something into a complex narrative

- advance/drive the plot

- introduce/present the protagonist/a character

- describe/depict/portray a character (as…)/(somebody as) a hero/villain

- create an exciting/a tense atmosphere

- build/heighten the suspense/tension

- evoke/capture the pathos of the situation

- convey emotion/an idea/an impression/a sense of…

- engage the reader

- seize/capture/grip the (reader's) imagination

- arouse/elicit emotion/sympathy (in the reader)

- lack imagination/emotion/structure/rhythm

- use/employ language/imagery/humor/an image/a symbol/a metaphor/a device

- use/adopt/develop a style/technique

- be rich in/be full of symbolism

- evoke images of…/a sense of…/a feeling of…

- create/achieve an effect

- maintain/lighten the tone

- introduce/develop an idea/a theme

- inspire a novel/a poet/somebody's work/somebody's imagination

- read an author/somebody's work/fiction/poetry/a text/an article/a poem/a novel/a chapter/a passage

- review an article/a book/a novel/somebody's work

- give something/get/have/receive a good/bad review

- be hailed (as)/be recognized as a masterpiece

- quote a phrase/a line/a stanza/a passage/an author

- provoke/spark discussion/criticism

- study/interpret/understand a text/passage

- translate somebody's work/a text/a passage/a novel/a poem

Other results

Nearby words.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of literature

Examples of literature in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'literature.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin litteratura writing, grammar, learning, from litteratus

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

Phrases Containing literature

- gray literature

Articles Related to literature

Famous Novels, Last Lines

Needless to say, spoiler alert.

New Adventures in 'Cli-Fi'

Taking the temperature of a literary genre.

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan...

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan Sees It

We know how the Nobel Prize committee defines literature, but how does the dictionary?

Dictionary Entries Near literature

literature search

Cite this Entry

“Literature.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/literature. Accessed 4 Jul. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of literature, more from merriam-webster on literature.

Nglish: Translation of literature for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of literature for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about literature

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, flower etymologies for your spring garden, 12 star wars words, 'swash', 'praya', and 12 more beachy words, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of literature in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

literature noun [U] ( WRITING )

- He's very knowledgeable about German literature.

- I had a brilliant English teacher who fired me with enthusiasm for literature at an early age .

- She's studying for an MA in French literature.

- Classic literature never goes out of print .

- The festival is to encompass everything from music , theatre and ballet to literature, cinema and the visual arts .

- action hero

- alliterative

- alternative history

- fictionality

- fictionally

- non-canonical

- non-character

- non-literary

- non-metrical

- sympathetically

- tartan noir

literature noun [U] ( SPECIALIST TEXTS )

- advance notice

- advance warning

- advertisement

- aide-mémoire

- bumper sticker

- push notification

- the gory details idiom

- the real deal

literature noun [U] ( INFORMATION )

- information Can I get some information on uni courses?

- details Please send me details of your training courses.

- directions Just follow the directions on the label.

- instructions Have you read the instructions all the way through?

- directions We had to stop and ask for directions.

- guidelines The government has issued new guidelines on health and safety at work.

- adverse publicity

- cross-selling

- customer relationship management

- demographics

- differentiator

- opinion mining

- overexposure

- trade dress

- unadvertised

- unmarketable

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

literature | American Dictionary

Literature | business english, examples of literature, collocations with literature.

These are words often used in combination with literature .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of literature

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

a bear with white fur that lives in the Arctic

Fakes and forgeries (Things that are not what they seem to be)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- literature (WRITING)

- literature (SPECIALIST TEXTS)

- literature (INFORMATION)

- Business Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

To add literature to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add literature to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Broad and narrow conceptions of poetry

- Translation

- The word as symbol

- Themes and their sources

- The writer’s personal involvement

- Objective-subjective expression

- Folk and elite literatures

- Modern popular literature

- Social and economic conditions

- National and group literature

- The writer’s position in society

- Literature and the other arts

- Lyric poetry

- Prose fiction

- Future developments

- Scholarly research

- Literary criticism

- Do adults read children's literature?

- When did American literature begin?

- Who are some important authors of American literature?

- What are the periods of American literature?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Oregon State University - College of Liberal Arts - What is Literature? || Definition and Examples

- Humanities LibreTexts - What is Literature?

- PressbooksOER - Introduction to Literature

- Pressbooks Create - The Worry Free Writer - Literature

- Table Of Contents

literature , a body of written works. The name has traditionally been applied to those imaginative works of poetry and prose distinguished by the intentions of their authors and the perceived aesthetic excellence of their execution. Literature may be classified according to a variety of systems, including language , national origin, historical period, genre , and subject matter.

For historical treatment of various literatures within geographical regions, see such articles as African literature ; African theater ; Oceanic literature ; Western literature ; Central Asian arts ; South Asian arts ; and Southeast Asian arts . Some literatures are treated separately by language, by nation, or by special subject (e.g., Arabic literature , Celtic literature , Latin literature , French literature , Japanese literature , and biblical literature ).

Definitions of the word literature tend to be circular. The 11th edition of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary considers literature to be “writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest.” The 19th-century critic Walter Pater referred to “the matter of imaginative or artistic literature” as a “transcript, not of mere fact, but of fact in its infinitely varied forms.” But such definitions assume that the reader already knows what literature is. And indeed its central meaning, at least, is clear enough. Deriving from the Latin littera , “a letter of the alphabet,” literature is first and foremost humankind’s entire body of writing; after that it is the body of writing belonging to a given language or people; then it is individual pieces of writing.

But already it is necessary to qualify these statements. To use the word writing when describing literature is itself misleading, for one may speak of “oral literature” or “the literature of preliterate peoples.” The art of literature is not reducible to the words on the page; they are there solely because of the craft of writing. As an art, literature might be described as the organization of words to give pleasure. Yet through words literature elevates and transforms experience beyond “mere” pleasure. Literature also functions more broadly in society as a means of both criticizing and affirming cultural values.

The scope of literature

Literature is a form of human expression. But not everything expressed in words—even when organized and written down—is counted as literature. Those writings that are primarily informative—technical, scholarly, journalistic—would be excluded from the rank of literature by most, though not all, critics. Certain forms of writing, however, are universally regarded as belonging to literature as an art. Individual attempts within these forms are said to succeed if they possess something called artistic merit and to fail if they do not. The nature of artistic merit is less easy to define than to recognize. The writer need not even pursue it to attain it. On the contrary, a scientific exposition might be of great literary value and a pedestrian poem of none at all.

The purest (or, at least, the most intense) literary form is the lyric poem, and after it comes elegiac, epic , dramatic, narrative, and expository verse. Most theories of literary criticism base themselves on an analysis of poetry , because the aesthetic problems of literature are there presented in their simplest and purest form. Poetry that fails as literature is not called poetry at all but verse . Many novels —certainly all the world’s great novels—are literature, but there are thousands that are not so considered. Most great dramas are considered literature (although the Chinese , possessors of one of the world’s greatest dramatic traditions, consider their plays, with few exceptions, to possess no literary merit whatsoever).

The Greeks thought of history as one of the seven arts, inspired by a goddess, the muse Clio. All of the world’s classic surveys of history can stand as noble examples of the art of literature, but most historical works and studies today are not written primarily with literary excellence in mind, though they may possess it, as it were, by accident.

The essay was once written deliberately as a piece of literature: its subject matter was of comparatively minor importance. Today most essays are written as expository, informative journalism , although there are still essayists in the great tradition who think of themselves as artists. Now, as in the past, some of the greatest essayists are critics of literature, drama , and the arts.

Some personal documents ( autobiographies , diaries , memoirs , and letters ) rank among the world’s greatest literature. Some examples of this biographical literature were written with posterity in mind, others with no thought of their being read by anyone but the writer. Some are in a highly polished literary style; others, couched in a privately evolved language, win their standing as literature because of their cogency, insight, depth, and scope.

Many works of philosophy are classed as literature. The Dialogues of Plato (4th century bc ) are written with great narrative skill and in the finest prose; the Meditations of the 2nd-century Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius are a collection of apparently random thoughts, and the Greek in which they are written is eccentric . Yet both are classed as literature, while the speculations of other philosophers, ancient and modern, are not. Certain scientific works endure as literature long after their scientific content has become outdated. This is particularly true of books of natural history, where the element of personal observation is of special importance. An excellent example is Gilbert White’s Natural History and Antiquities of Selbourne (1789).

Oratory , the art of persuasion, was long considered a great literary art. The oratory of Native Americans, for instance, is famous, while in Classical Greece, Polymnia was the muse sacred to poetry and oratory. Rome’s great orator Cicero was to have a decisive influence on the development of English prose style. Abraham Lincoln ’s Gettysburg Address is known to every American schoolchild. Today, however, oratory is more usually thought of as a craft than as an art. Most critics would not admit advertising copywriting, purely commercial fiction , or cinema and television scripts as accepted forms of literary expression, although others would hotly dispute their exclusion. The test in individual cases would seem to be one of enduring satisfaction and, of course, truth. Indeed, it becomes more and more difficult to categorize literature, for in modern civilization words are everywhere. Humans are subject to a continuous flood of communication . Most of it is fugitive, but here and there—in high-level journalism, in television, in the cinema, in commercial fiction, in westerns and detective stories, and in plain, expository prose—some writing, almost by accident, achieves an aesthetic satisfaction, a depth and relevance that entitle it to stand with other examples of the art of literature.

Get the Reddit app

A place for learning English. 英語の学びのスペースです。 Un lugar para aprender Inglés. مكان لتعلم اللغة الإنجليزية. Un lieu pour apprendre l'Anglais. Ein Ort zum Englisch lernen.

Pronunciation of "literature"

We are a group of friends saying this word differently - how do you pronounce the "t" sounds?

Native speakers make it sound like it's a "ch" sound, and I'm confused.

Do both t's make a ch sound?

Join our mailing list and receive your free eBook. You'll also receive great tips on story editing, our best blogs, and learn how to use Fictionary software to make your story unforgettable.

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Blogs / Language / Jargon Examples In Literature

Write Your First Book

Jargon examples in literature.

Whether we realize it or not, we all regularly encounter jargon in our work and in our everyday lives. But what is jargon and, specifically, what is jargon in literature? What do writers and editors need to know?

What is Jargon? Definition and History

Jargon is the particular set of terminology and language used within:

- Professions,

- Topics, or;

It can be found within any specialized area and

is especially common within specific industries. The term ‘jargon’ refers to the professional and proper terms, unlike slang or colloquialisms.

According to an article on Jargon on supersummary.com , the first time the term ‘jargon’ was used was in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales , written in the 15 th century.

Chaucer used the term to refer to bird sounds, but its meaning changed over time. It was in the late 20 th century that it was used to refer to “specialized language that’s incomprehensible to those outside the field.”

For example:

- Literature, and;

All have their own specialized language that is used and understood by those within that field.

Jargon can be used in both positive and negative ways. On the one hand, it can offer people within a certain group a specialized vocabulary to use with one another, so that communication is clear and simplified.

On the negative side, it can at times “be used to exclude others who are not part of the group or to show one’s own belonging to the group” ( Jargon , literarydivices.com). It’s for this reason that the article 6+ Jargon Examples in Literature on examples.com calls it “the Mean Girls of Language.”

Jargon Examples in Literature

Writers and editors have terms they frequently use when communicating with each other, like we do in the Fictionary Community . Within our field, when we talk about ‘craft books,’ for example, we automatically know we aren’t talking about books that teach us how to crochet couches for cats (yes, that’s a thing, and they’re pretty cute). Rather, we know this term refers to books that are specifically about writing and editing.

The field of literature has its own, large set of jargon to aid us with its study, discussion, and analysis. Writers use jargon in writer’s groups and with critique partners to ask for and give feedback and advice, and to ensure we are using important elements.

But there is another, even more important way writers use jargon.

Why and How to Apply Jargon to Writing

I’m sure we’ve all heard that age-old piece of advice, ‘Write what you know.’

Yet, as fiction authors, if we only ever wrote what we know, our writing wouldn’t be very exciting, would it? If you want to write about something you don’t know, research it, make sure you know the jargon, and use that jargon correctly.

Jargon can be integral to setting up your characters’ backgrounds and professions in a realistic way.

If you’re writing about a character who works in a particular profession, for example, using the accepted jargon for that profession correctly can make a huge difference to how realistic that character is.

Use terms incorrectly, and readers who work in that profession—or who know someone who does—may be pulled out of the story. Their disbelief will no longer be suspended.

The use of jargon, though, doesn’t have to be limited to the profession itself, but can also include terms related to the setting and genre.

Using Jargon According to Profession, Setting, and Genre

Let’s say you’re writing a crime novel about a murder.

Your protagonist could be a detective with the local police department, or maybe an FBI agent

When that character is investigating the area where the murder took place, they would use jargon such as:

- Crime scene,

- Dusting for prints

- Perpetrator,

- Person of Interest,

- Witness, and so on.

If that same character were testifying at a trial, we could hear additional terms such as:

- Prosecution,

- Eye-witness,

- Character Witness,

- Expert Witness,

- Witness Stand,

- Circumstantial Evidence,

- Hearsay, and so on.

Your lawyer character better know those terms and use them correctly, as well.

For a sports romance about hockey players, you might expect to hear terms like:

- Body Check,

- Trade, and;

Since sports romance tends to lean to the lighthearted, romantic comedy side, you might also hear slang terms (similar to jargon but casual instead of professional) like:

- Puck Bunny,

- Puck Head, and;

- Sharpshooter (which has a different connotation if you’re writing about army rangers or assassins).

You don’t have to be a homicide detective or a private investigator to write crime, and you don’t need to be a hockey player to have a protagonist who is. But if you aren’t, then make sure you do proper research into the profession so that you can be sure you’re using the related jargon correctly.

Using Jargon to Represent Different Time Periods

The time period a story is set in can affect the jargon that’s used as well. A medical doctor in a book set in the middle ages likely would not use the same jargon as a modern doctor.

For example, according to an article written by Trisha Torrey and posted on verywellhealth.com , some medical jargon used in the past that is not used today are:

- Ablepsy (Blindness),

- Blood Poisoning (Sepsis),

- Consumption (Tuberculosis),

- Melancholia (Depression), and;

- Ship Fever (Typhus).

The same is true for a book set in the future—though you might have to make up your own jargon in this case, since the professions, equipment, or technology you are writing about might not have been (and may never be) invented.

Using Jargon in Worldbuilding

Writers of fantasy—or any genre or story not set in the real world—will have to create a set of jargon to use in their novel or series about that particular fantasy world. It is then important to ensure the newly crafted jargon is used consistently all throughout the book or series.

Examples of Jargon in Literature

Brandon sanderson’s mistborn trilogy.

Brandon Sanderson, a well-known fantasy author, creates his own jargon for various things in his fantasy worlds, such as professions or titles within the political or social hierarchy, and for his unique magic systems.

For example, in his Mistborn Trilogy, his magic system involves using trace metals, either already present in the body or consumed, to perform various feats of magic.

This system is called Allomancy and the people who can use this magic are called Allomancers. But the jargon gets more specific than this as well.

People who can use one type of metal are called Mistings, and those rare few who can use all types of metal are Mistborn. He refers to using the metals to get specific results ‘burning,’ as in ‘burning tin,’ ‘burning pewter,’ and so on.

Sanderson sets up the basics in book 1 of the trilogy, adding to it as the story progresses.

Then he is consistent in the use of his coined jargon for all of the systems he created for that fantasy world, The Final Empire, through to the end of the series.

The Silence of the Lambs by Thomas Harris

In The Silence of the Lambs , the protagonist, Clarice Starling, is a trainee in the FBI’s Behavioral Sciences Unit.

She is sent to interview Hannibal Lector, a brilliant psychiatrist, serial killer, and cannibal, who is currently housed in an asylum. She is to ask for his help in locating the latest kidnapping victim of another serial killer, Buffalo Bill, before he can murder the girl, who happens to be the daughter of a senator.

Because of her position and the task she is assigned, we get both law enforcement (FBI) jargon and psychiatric jargon throughout the book, and in the movie adaptation.

We see terms like:

- Investigation,

- Serial Killer,

- Credentials,

- Behavioral Science,

- Psychopath,

- Psychiatrist, and;

If you are a writer, chances are you’ve already been using jargon, even if you’ve never realized it.

However, if you are conscious of it and intentional in using it correctly and effectively in your stories, it can add an extra layer of realism to help draw readers into your story world.

One of the most important ways it can do this is by helping you create realistic characters your readers can relate to.

TOI TimesPoints

Daily check-ins: 0 /5 completed.

You must login to keep earning daily check-in points

REDEEM YOUR TIMES POINTS

Total redeemable TimesPoints

* TimesPoints expire in 1 year from the day of credit

TODAY’S ACTIVITY

Visit toi daily & earn times points.

- Edit Profile

- My Subscription

- The Economic Times

- The Times Of India

- Maharashtra Times

- Epaper Preferences

This content is not available in your region. For Latest news visit - www.timesofindia.com

File(s) under embargo

From judith to dorigen: the feminine embodiment of violence in medieval english literature.

When one thinks of the medieval past, one might think of knights with their shining armor and swords; these are warriors. My dissertation seeks to examine and expose how “warriors” are gendered as masculine; a person or character categorized as a warrior might be assumed to be a man unless otherwise specified to be a “woman warrior.” The need for the qualifying adjective (“woman” or “female”) illustrates that the maleness of warriorhood and violence is understood as implicit. This governing assumption affects how women’s actions, particularly women’s violent actions, are interpreted. This dissertation takes women’s violence as a starting point, examining characters from Judith to Chaucer’s Dido. I show how and why the violence these women enact cannot be relegated to, say, maternal instinct or spirituality. The spiritual warrior is herself impressive, of course; she is a tool, a weapon of God, through whom God fights. The idea of the spiritual warrior then allows for discussions of women without painting them as inherently violent or aggressive. Instead, the spiritual warrior is the martyr, an extension of maternal instincts and the idea that women are caretakers and, when necessary, protectors. But these self-sacrificial ideals, often associated with maternity, are not, nor should they be, a requirement for womanhood.

I argue that in order to create a capacious enough definition of “woman” and even femininity, we must prize definitions of femininity from the grip of the patriarchy. What if we took these women on their own terms, instead? I seek to do exactly this: to examine, throughout this dissertation, both the ways that violent women act and what they say, without considering how their behavior might, nonetheless, be understood to conform to limiting ideas of femininity (such as the virgin or the whore). I thereby invite us to think about what it means when violent women enact their will on the world; and I also attend to the physical, in addition to the spiritual, effects of this violence (like killing someone). My work suggests that, in order to take gender seriously, we must pay attention to these moments when women hurt or kill either someone else or themselves.

Degree Type

- Doctor of Philosophy

Campus location

- West Lafayette

Advisor/Supervisor/Committee Chair

Additional committee member 2, additional committee member 3, additional committee member 4, usage metrics.

- British and Irish literature

- Literary theory

- Daily Lessons

- Get your widget

How to pronounce literature in British English ( 1 out of 3070 ):

Enabled javascript is required to listen to the english pronunciation of 'literature'..

Definition:

Click on any word below to get its definition:, nearby words:, having trouble pronouncing 'literature' learn how to pronounce one of the nearby words below:.

- lithosphere

- literatures

- lithography

When you begin to speak English, it's essential to get used to the common sounds of the language, and the best way to do this is to check out the phonetics. Below is the UK transcription for 'literature' :

- Modern IPA: lɪ́trəʧə

- Traditional IPA: ˈlɪtrəʧə

- 3 syllables : "LIT" + "ruh" + "chuh"

Test your pronunciation on words that have sound similarities with 'literature' :

- low temperature

- little brother

- lottery winner

Tips to improve your English pronunciation:

Here are a few tips that should help you perfect your pronunciation of 'literature' :.

- Sound it Out : Break down the word 'literature' into its individual sounds "lit" + "ruh" + "chuh". Say these sounds out loud, exaggerating them at first. Practice until you can consistently produce them clearly.

- Self-Record & Review : Record yourself saying 'literature' in sentences. Listen back to identify areas for improvement.

- YouTube Pronunciation Guides : Search YouTube for how to pronounce 'literature' in English .

- Pick Your Accent : Mixing multiple accents can be confusing, so pick one accent ( US or UK ) and stick to it for smoother learning.

Here are a few tips to level up your english pronunciation:

- Mimic the Experts : Immerse yourself in English by listening to audiobooks, podcasts, or movies with subtitles. Try shadowing—listen to a short sentence and repeat it immediately, mimicking the intonation and pronunciation.

- Become Your Own Pronunciation Coach : Record yourself speaking English and listen back. Identify areas for improvement, focusing on clarity, word stress, and intonation.

- Train Your Ear with Minimal Pairs : Practice minimal pairs (words that differ by only one sound, like "ship" vs. "sheep" ) to improve your ability to distinguish between similar sounds.

- Explore Online Resources : Websites & apps offer targeted pronunciation exercises. Explore YouTube channels dedicated to pronunciation, like Rachel's English and English with James for additional pronunciation practice and learning.

- Open access

- Published: 26 June 2024

WHO, WHEN, HOW: a scoping review on flexible at-home respite for informal caregivers of older adults

- Maude Viens 1 , 2 ,

- Alexandra Éthier 1 , 2 ,

- Véronique Provencher 1 , 2 &

- Annie Carrier 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 767 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

146 Accesses

Metrics details

As the world population is aging, considerable efforts need to be put towards developing and maintaining evidenced-based care for older adults. Respite services are part of the selection of homecare offered to informal caregivers. Although current best practices around respite are rooted in person centeredness, there is no integrated synthesis of its flexible components. Such a synthesis could offer a better understanding of key characteristics of flexible respite and, as such, support its implementation and use.

To map the literature around the characteristics of flexible at-home respite for informal caregivers of older adults, a scoping study was conducted. Qualitative data from the review was analyzed using content analysis. The characterization of flexible at-home respite was built on three dimensions: WHO , WHEN and HOW . To triangulate the scoping results, an online questionnaire was distributed to homecare providers and informal caregivers of older adults.

A total of 42 documents were included in the review. The questionnaire was completed by 105 participants. The results summarize the characteristics of flexible at-home respite found in the literature. Flexibility in respite can be understood through three dimensions: (1) WHO is tendering it, (2) WHEN it is tendered and (3) HOW it is tendered. Firstly, human resources ( WHO ) must be compatible with the homecare sector as well as being trained and qualified to offer respite to informal caregivers of older adults. Secondly, flexible respite includes considerations of time, duration, frequency, and predictability ( WHEN ). Lastly, flexible at-home respite exhibits approachability, appropriateness, affordability, availability, and acceptability ( HOW ). Overall, flexible at-home respite adjusts to the needs of the informal caregiver and care recipient in terms of WHO , WHEN , and HOW .

This review is a step towards a more precise definition of flexible at-home respite. Flexibility of homecare, in particular respite, must be considered when designing, implementing and evaluating services.

Peer Review reports

It is an undeniable fact that the world population is aging [ 1 ]. The World Health Organization [ 1 ] estimates that from 2015 to 2050, the percentage of people over 60 years of age will nearly double (from 12 to 22%). Governments must therefore put in place policies, laws and funding infrastructures to provide evidence-based social services and healthcare that are in line with best practices to allow people to age in place [ 2 ]. Aging in place refers to “the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level” [ 3 ]. Relevant literature indicates that people do not want to age or end their lives in institutionalized care; most wish to receive care in their home and remain in their community with their informal caregivers [ 4 ].

There is then a need to adequately support informal caregivers (caregiver) in the crucial role that they have in allowing older adults to age in their own home. A caregiver is “a person who provides some type of unpaid, ongoing assistance with activities of daily living or instrumental activities of daily living” [ 5 ]. In their duties, caregivers of older adults are responsible for a considerable amount of homecare [ 6 ]: Transportation, management of appointments and bills, domestic chores, etc. Private and public organizations offer a plethora of services to support caregivers of older adults (e.g., support groups, housekeeping, etc.), including respite. Respite is a service for caregivers consisting in “the temporary provision of care for a person, at home or in an institution, by people other than the primary caregiver” [ 7 ]. Maayan and collaborators [ 7 ] characterize all respite services according to three dimensions: (1) WHERE : The place; in a private home, a daycare centre or a residential setting, (2) WHEN : The duration and planning; ranging from a couple of hours to a number of weeks, planned or unplanned, and finally, (3) WHO : The person providing the service; this may be trained or untrained individuals, paid staff or volunteers. Respite is widely recognized as necessary to support caregivers of older adults [ 8 , 9 ]. Indeed, a large number of studies identify the need and use for respite [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. For example, Dal Santo and colleagues (2007) found that caregivers of older adults ( n = 1643) used respite to manage stressful caregiving situations, but also to have a “time away”, without having to worry about their caregiving role [ 13 ]. At-home respite seems to be favoured over other forms of respite, even with the perceived drawbacks, such as the privacy breach of having a care worker in one’s home [ 14 , 15 ].

Studies suggest that caregivers of older adults seek flexibility as a main component of respite [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Flexibility, in line with person-centered care, allows respite that addresses their needs, rather than being services that are prescribed according to other criteria [ 16 , 17 ]. Thus, flexibility, both in accessing and in the respite itself, is essential [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Although there seems to be a consensus around the broader definition of respite, there is no literature reviewing the characteristics of flexible at-home respite. Some studies and reports from organizations and governments document the flexible characteristics of their models, but there are few literature reviews that address them, specifically [ 18 , 22 , 24 ]. Both reviews by Shaw et al. [ 18 ] and Neville et al. [ 19 ] concede that an operational definition of respite ( WHEN , WHERE , WHO ) is not clear. Neville et al. [ 19 ] conclude that “respite has the potential to be delivered in flexible and positive ways”, without addressing these ways. The absence of a unified definition for flexible at-home respite contributes to the challenges of implementing and evaluating services, as well as measuring their effect. Although respite services are deemed necessary, they are seldom used [ 19 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]; as little as 6% of all caregivers receiving any kind support services in Canada actually use them. In scientific literature, the under-usage of respite services is a shared reality around the world [ 28 ]. One of the main reasons for this under-usage is the overall lack of flexibility in both obtaining and using respite [ 29 , 30 ]. Synthesizing the characteristics of flexible at-home respite services is the first steppingstone to a common operational definition. This could contribute to increasing respite use through the implementation or enrichment of programs in ways that answer the dyad’s (caregiver and older adult) needs.

Consequently, to support the implementation and evaluation of homecare programs, the objective of this study was to synthesize the knowledge on the characteristics of flexible at-home respite services offered to caregivers of older adults.

A scoping review [ 32 , 33 , 34 ] was conducted, as part of a larger multi-method participatory research known as the AMORA project [ 31 ] to characterize flexible at-home respite. Scoping reviews allow to map the extent of literature on a specific topic [ 32 , 34 ]. The six steps proposed by Levac et al. [ 32 ] were followed: [ 1 ] Identifying the research question; [ 2 ] searching and [ 3 ] selecting pertinent documents; [ 4 ] extracting ( or charting ) relevant data; [ 5 ] collating, summarizing and reporting findings; [ 6 ] consultation with stakeholders. The sixth step is optional.

Identifying the research question

The research question was: “What are the characteristics of flexible at-home respite services offered to caregivers of older adults?” As the research was conducted, this question was divided into three sub-questions:

WHO is tendering flexible respite?

WHEN is flexible respite tendered?

HOW is flexible respite tendered?

Identifying relevant documents

The search strategy consisted of two methods. First, the key words (1) respite (2) informal caregivers (3) older adults in the title or abstract allowed to identify relevant documents (Table 1 ). Initially included, the term “ flexib *” was removed from the search, given the low number generated (60 versus 1,179 documents without). The first author and a librarian specialized in health sciences research documentation conducted the literature research in July of 2021 and updated it in December of 2022 in 6 databases ( Ageline , Cochrane , CINAHL , Medline , PsychInfo , and Abstracts in Social Gerontology ). The expanded research strategy then consisted of the identification of relevant documents from the selected bibliography and one article that was found by searching for unavailable references (alternative article).

Study selection

To review the most recent literature on flexible at-home respite service characteristics, the research team focused on writings within a 20-year span, as have other reviews (e.g., [ 35 , 36 ]); documents thus had to be published between 2001 and 2022. The research team selected documents written in French or English, only. Included documents had to come from either (1) scientific literature (i.e., articles in an academic journal presenting an empirical study or reviews) or (2) reports and briefs from government, homecare organizations or research centres. All study designs were included. The research team convened that at-home respite is an (1) individual (i.e., not in a group) service (although, theoretically, two persons living in the same household could receive it) from (2) a professional or a volunteer that occurs (3) in the home and that (4) it requires no transport for the dyad. To select documents related to flexible at-home respite, the research team identified those in which the respite displayed an ability to adapt to the dyad’s needs on at least one characteristic of the service, as presented by Maayan and collaborators ( WHERE [Not relevant to this review, as it focuses on at-home respite] , WHO , WHEN ). The team concluded that these three dimensions lacked the precision to globally characterize the service. Indeed, they did not describe access to or activities occurring during respite, or, as the team called it, the HOW (Fig. 1 ). Excluded documents were those covering several services at once, preventing the differentiation of elements that were specific to at-home respite services. As this is a scoping review, the research team did not include a critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence [ 32 , 34 ].

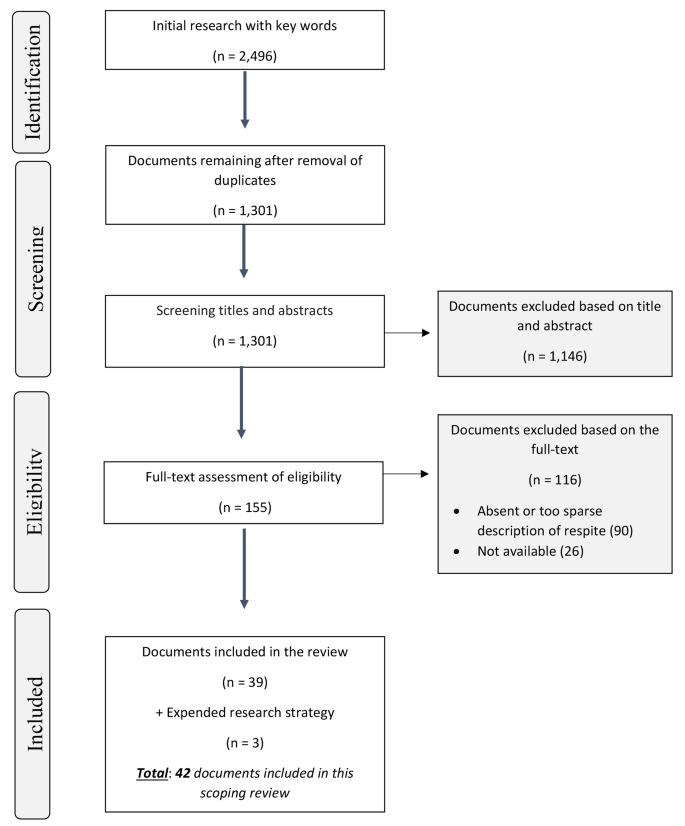

Following the step-by-step Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) guidelines [ 37 ], the research team met to define the selection strategy. First, they screened the documents by their titles and abstracts, before determining their eligibility, based on their full text. Considering the limited human and financial resources, at each step of the PRISMAScR, a second team member assessed 10% of the documents independently to co-validate the selection; the goal was to reach 80% of agreement between both team members regarding document inclusion or exclusion. If an agreement was not reached, they would meet to obtain a consensus. The research team used Zotero reference management software to store documents as well as a cloud-based website to collaborate on the selection.

Conceptual mapping of results: HOW , WHEN , WHO

Charting the data

The first author charted (or extracted) both quantitative and qualitative data. To quantitatively characterize documents, contextual data (country of origin, year of publication, type of documents, etc.) was extracted in a Microsoft Excel table. For the qualitative data, the research team created an extraction table in Microsoft Word that included the three dimensions of respite ( WHO , WHEN and HOW) and one “ other ” dimension, as to not force any excerpts under the three dimensions. To co-validate the data charting, the second and third authors replicated 10% of the process. Expressly, the first author extracted elements related to a flexible characteristic of the at-home respite ( WHO , WHEN , HOW or other ). Considering limited resources, the third and second authors both co-validated the extraction of 10% of the documents. Authors met to reach a consensus where a disagreement arose.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results

The research team used content analysis to “attain a condensed and broad description of the phenomenon” [ 38 ]. To do so, data was prepared (familiarization with the data and extraction of pertinent excerpts) and organized (classification of excerpts) to build a characterization of flexible at-home respite. In this scoping review, a deductive content analysis began with three main categories ( WHO , WHEN , HOW ), with the addition of the temporary “ other ” category. Content analysis aimed to divide these categories into several generic categories, which subdivided into sub-categories (Fig. 2 ), inductively. This allowed to define the three main categories. While the WHO and the WHEN categories describe the service itself (time, duration, qualified staff, etc.), the HOW category is specific to the interface between the organization offering respite and the dyad (assessing the needs of the dyad, coordinating care, etc.). An interface is a situation where two “subjects” interact and affect each other [ 39 ]. In the context of homecare services, Levesque, Harris and Russell (2013) have defined that interface as access [ 40 ]. Therefore, to define the generic categories of the HOW , the team used the five dimensions of their access to care framework: Approachability, appropriateness, affordability, availability and acceptability [ 40 ]. Approachability relates to users recognizing the existence and accessibility of a service [ 40 ]. Appropriateness encompasses the alignment between services and users’ needs, considering timeliness and assessment of needs [ 40 ]. Affordability pertains to users’ economic capacity to allocate resources for accessing suitable services [ 40 ]. Availability signifies that services can be reached, both physically and in a timely manner [ 40 ]. Acceptability involves cultural and social factors influencing users’ willingness to accept services [ 40 ]. In other words, the HOW category focuses on the organizational or professional aspects of the service and how they can be adapted to the dyad.

To co-validate the classification, the research team met until they were all satisfied with the categorization. The first author then completed the classification. After classifying 20% of the documents, the second author would comment the classification. When the authors reached an agreement, the first author would move on to the classification of another 20%. First and second authors would meet when disagreements about classification and categories arose, to confer and adjust. Finally, all categories were discussed with the third author, until a consensus was reached. Once categorization was achieved, the team prepared a synthesis report. In this report, the team defined the main categories ( WHO , WHEN, HOW , other ) and their generic and sub-categories (Fig. 2 ) with pertinent excerpts from the reviewed literature. In summary, the results of the scoping review characterize flexible at-home respite under three attributes: WHO , WHEN and HOW .

Content analysis: Types of categories according to Elo and Kyngäs (2007) ( with examples from results )

Consultation

Rather than conducting a focus group as suggested by Levac and collaborators [ 32 ], the team chose to triangulate the results with those from a survey as a consultation strategy. Specifically, the research team took advantage of a survey being conducted with relevant stakeholders in the larger study (AMORA project), as it allowed to respect the scoping review’s allocated resources. The survey aimed to define flexible at-home respite and the factors affecting its implementation and delivery. A committee including a researcher, a doctoral student and a representative of an organization funding homecare services in Québec (Canada), developed the survey following the three stages proposed by Corbière and Fraccaroli [ 41 ]. It originally included a total of 21 items: Thirteen [ 13 ] close-ended and 8 open-ended questions. Of these 8, 2 addressed the characteristics of an ideal at-home service and suggestions regarding respite and were used here for triangulation purposes. The questionnaire was published online, in French, on the Microsoft Forms ® platform in the summer of 2020. Recruitment of participants (caregivers and people from the homecare sector) was done via email, by contacting regional organizations (Eastern Townships, Québec, Canada). In addition, the 18 senior consultation tables spread throughout the territory of the province of Québec were solicited; working in collaboration with governmental instances in charge of services to older adults and caregivers, these tables bring together representatives for associations, groups or organizations concerned with their living conditions.

The goal was to triangulate the scoping review’s results, i.e., to identify what was common between the literature and real-world experiences, and, as such, to bring contextual value to the results. Accordingly, the team analyzed data using mixed categorization [ 42 ]. The categories from the scoping review served as a starting point (closed categorization), leaving room to create new categories, as the analysis progressed (open categorization). Once all the data (scoping and survey) was categorized, the team identified the characteristics according to sources. To do so, the team tabulated the reoccurrence of each category in the survey, in the scoping review, or in both. They then integrated the results to provide one unified categorization of flexible at-home respite. The AMORA project was approved by the research ethics committee of the Integrated University Health and Social Services Centre (CIUSSS) of the Eastern Townships (project number: 2021–3703).

Of the 1,301 papers retrieved through the database searches, 1,146 were not eligible based on title and abstract, while 116 were excluded after reading their full texts, resulting in 39 included documents (Fig. 3 ). Documents were mainly excluded because they did not provide details about the respite service and its flexibility. The expanded search yielded three additional documents, resulting in a total of 42 documents, included in this scoping review. This section details (1) the characteristics of the selected documents and (2) the characterization of flexible at-home respite.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR) flow chart of the scoping review process [ 37 ]

Characteristics of selected documents

The majority (86%) of the documents in the review (Table 2 ) are from after 2005, with only 14% of the documents published before 2005, and are from 9 countries; United States ( n = 18; 42%), United Kingdom ( n = 11; 26%), Australia ( n = 4; 10%), Canada ( n = 2; 5%), Ireland ( n = 2; 5%), France ( n = 2; 5%), Belgium ( n = 2; 5%), Germany ( n = 1; 2%), New Zealand ( n = 1). The types of documents were diverse: 68% ( n = 28) were empirical studies, 31% ( n = 13) theoretical papers and 1% ( n = 2) government briefs. Most ( n = 23; 56%) of the documents did not specify their research approach, while 10 and 9 took, respectively, a qualitative (23%) or quantitative approach (21%). Most documents address respite in the context of caregiving for someone living with Alzheimer’s disease or other neurocognitive disorders ( n = 25; 60%), while some targeted older adults in general ( n = 14; 34%), people in palliative care ( n = 4; 9%) or other older adult populations (for example, veterans) ( n = 3; 1%). Respite was usually tendered by community organizations specialized in homecare ( n = 32; 78%). Although the majority of the documents ( n = 31; 75%) did not address the type of region (rural, urban, or mixed) surrounding the caregivers, those who did ( n = 11; 26%) mainly reported being in a mixed environment ( n = 9; 21%).

Characteristics of survey participants

Although all 100 participants completed the questionnaire, 71 participants answered at least 1 of the 2 open-ended questions: Each question had 66 and 41 answers. Of those 71 participants, most of them were women ( n = 60; 85%). All participants were aged on average 55 years old (SD = 15). They were mostly from the Eastern Townships area ( n = 56; 79%). Most participants were either caregivers ( n = 24; 34%) or homecare workers ( n = 28; 39%), while some were service administrators ( n = 11; 15%), and some reported being both caregivers as well as working in the formal caregiving sector ( n = 7; 10%). Only one person reported themselves as an older adult having a caregiver.

Characterization of flexible at-home respite

The characterization of flexible at-home respite will be presented below in three main categories which are WHO , WHEN , and HOW . Of note, 10 (24%) of the included documents had three categories of flexible components, 16 (38%) had 2 categories and 1 category. Almost all documents discussed the HOW of flexible at-home respite ( n = 40, 95%). Out of the 33 categories constructed with the scoping review, only 6 (18%) were not reported in the questionnaire: (1) planned respite ( WHEN ), (2) screening of dyads ( HOW ), (3) determining frequency of respite ( HOW ), (4) coordination of care ( HOW ), (5) voucher approach ( HOW ) and (6) acceptability to low-income households ( HOW ). Moreover, the questionnaire added three characteristics that were not present in the scoping review: (1) respite needs to be approachable, (2) the organization must be prompt** and adhocratic** and (3) able to deliver respite regardless of the season** (availability). Generic or sub-categories present only in the scoping review are identified with 1 asterisk (*), while those present only in the questionnaire have 2 (**).

In the selected documents, the WHO dimension of flexible at-home respite services can be broken down into three qualifiers: (1) Compatible , (2) qualified and (3) trained (Table 3 ). This dimension includes all human resources contributing to homecare (administrative staff, governing bodies, paid and volunteer care workers). First, the workforce behind flexible respite is compatible , meaning it has personal characteristics and profiles relevant to homecare for caregivers of older adults [ 17 , 53 , 62 , 63 , 68 ]. Gendron and Adam explain this by describing how the role of the care worker in Baluchon Alzheimer™ goes beyond training: “The nature of their work with [Baluchon Alzheimer™] requires particular human and professional qualities that are quite as important as academic credentials” [ 53 ]. Personal characteristics such as flexibility [ 53 , 62 , 63 , 68 ], empathy and patience [ 17 , 53 , 62 ] are deemed essential attributes. Secondly, the workforce is qualified : It has the necessary skills, abilities and knowledge from past professional [ 14 , 45 , 62 , 70 ] and personal experience [ 62 ] to work, or volunteer, with caregivers of older adults. For a program like Baluchon Alzheimer™, “the backgrounds of the baluchonneuses vary […]; all have experience in gerontology” [ 53 ]. Other areas of qualification in the included documents are a nursing background [ 18 , 45 ] or knowledge related to dementia [ 69 ]. Finally, flexible at-home respite requires a trained workforce engaged in the process of acquiring knowledge and learning the skills to provide respite services to caregivers of older adults. For example, homecare organizations can offer specific training on various topics, depending on their target clientele: Dementia [ 44 ], palliative care [ 59 ], or homecare in general [ 44 ].

The WHEN dimension of flexible at-home respite contains 4 temporal features: (1) Time , (2) duration , (3) frequency and (4) predictability (Table 4 ). First, flexible respite is available on a wide range of possible time slots. For example, the service is “available 24 hours, but typically from 9 am to 10 pm” [ 64 ]. Secondly, flexible respite is accessible on a wide range of possible durations . The Community Dementia Support Service (CDSS) is an example of flexibility in duration by “[being] totally flexible, being available from 2 to 15 hours per week” [ 69 ]. Thirdly, the service is offered in different frequencies : It can be either recurrent or occasional, or a combination of both [ 18 , 64 , 66 ]. The last feature of the WHEN dimension is flexibility in predictability ; the respite service can be planned* or not. A study on respite services in South Australia found that most providers (93%) planned the respite care with the dyad, but that emergency or crisis services were still offered by 35% of them [ 50 ].

At-home respite is flexible when it demonstrates approachability : Caregivers can identify that some form of respite exists and can be reached (Table 5 ). For the respite service to be approachable, the organization needs to be reaching out to dyads; it proactively makes sure that caregivers of older adults have information on services, know of their existence and that they can be used. For example, the El Portal program put in place “advisory groups that included the local clergy, representatives from businesses, caregivers, and service providers who were used for outreach work” [ 66 ]. The organization also screens* dyads to assess their eligibility for respite, as well as for other services from the same program or organization. For example, the North Carolina (U.S.A.) Project C.A.R.E. has an initial assessment that considers the range of homecare services available, rather than just assessing for eligibility for a program [ 57 ]. In addition, flexible respite requires the organization to set attainable and inclusive requirements for eligibility, as to not discourage use [ 24 , 57 , 61 , 66 ]. Finally, the organization communicates consistently with the dyad. As Shanley explains in their literature review, “there are clear and open ways for carers to express concerns about the service, and an open mechanism is available for dealing with these concerns constructively” [ 17 ]. In addition, the survey participants discussed two other characteristics. First, for respite to be approachable, the organization is prompt**, respecting a reasonable delay between the request and the beginning of the service (wait list). Second, it is adhocratic**, meaning the organization does not depend on complex systems of rules and procedures to operate i.e., bureaucracy.

The second access dimension of flexible at-home respite is appropriateness (Table 6 ): The fit between respite services and the dyad’s needs, its timeliness, the amount of care spent in assessing their needs and determining the correct respite service. For the respite service to be appropriate, the organization assesses needs by collecting details about the dyad’s needs; this can include, but is not limited to, clinical, psychological, or social evaluation. The organization then proposes respite services from a wide range of options or packages: A multi-respite package, as presented by Arksey et al., can simply be the combination of at least two different respite services [ 44 ]. For the service to be appropriate, the organization also paces the respite. Apprehension towards service appropriateness can be mitigated by a gradual introduction to homecare, for example when the respite is presented as a trial [ 68 ]. The organization determines the service with the dyad and defines its different characteristics ( WHEN * , WHO ) so interventions correspond to their needs. The organization then determines the appropriate activities to do with the dyad during the respite. For example, the caregiver of older adults can be encouraged to use respite time for leisure (sleep, physical activity, etc.) [ 45 ], while the care worker supports the beneficiary in engaging in an activity such as a walk or a board game [ 14 ]. Furthermore, the organization coordinates* the services for the dyad and acts as a “respite broker” to arrange all aspects of care; this is especially relevant for programs that include a “care budget” that can be used at the caregivers’ discretion [ 58 ]. Finally, for the respite to be appropriate, the organization assures that it is in continuity with other health services, by connecting the dyads to pertinent resources. As described by Shaw, respite should be “embedded in a context that includes assessment, carer education, case management and counselling” [ 18 ].

The third access dimension of flexible at-home respite is affordability , referring to the economic capacity of the dyad to spend resources to use appropriate respite services (Table 7 ). The included documents only explored the direct cost of respite: The amount of money a dyad must pay to receive services. For the respite to be affordable, its direct cost is either (1) adapted, where the cost is modulated according to the dyad’s financial resources, for example on a sliding scale, based on income or (2) nonexistent [ 44 ].

Next, flexible at-home respite must demonstrate availability (Table 8 ): Services can be reached both physically and in a timely manner. Firstly, the organization offers respite in the dyads’ geographic area. Shanley described an at-home mobile respite program designed to reach rural and remote areas, where two care workers visit different locations for set periods of time [ 17 ]. Moreover, one sub-characteristic identified exclusively by the survey participants was seasonality. Indeed, the dyad has access to respite, regardless of the season**. Thus, the geography category is broken down between the access to service (1) in rural or remote areas and (2) notwithstanding the season. Flexibility in availability also requires that the dyads have access to unlimited respite time; the organization does not assign a finite bank of hours. Finally, the organization proposes diverse payment methods to the dyads. The consumer-directed approach is a way that homecare organizations offer flexibility. A care budget is allocated to the caregiver to purchase hours from homecare agencies or to hire their own respite workers. This includes payments to family members or friends to provide respite care [ 79 ]. An example of a type of consumer-directed approach is the use of vouchers*: Credit notes or coupons to purchase service hours from homecare agencies [ 44 ].

Finally, access to flexible at-home respite also relates to acceptability (Table 9 ): The cultural and social factors determining the possibility for the dyad to accept respite and the perception of the appropriateness of seeking services. For the respite to be acceptable, the organization targets and caters to the cultural diversity represented in their local population. The organization is also able to identify and to accommodate underserved groups. In the included documents, underserved groups lacked access to respite for two reasons: (1) Geographic isolation or (2) the requirements to be eligible to “traditional homecare” does not apply to them, for example, for younger people with dementia and people with HIV/AIDS [ 17 ]. The organization can target and cater to low-income households*. Rosenthal Gelman and his collaborators detail a program where, after realizing that low-income caregivers have greater unmet needs, special funds were set aside for respite care vouchers to be distributed [ 70 ].

This scoping review conducted with Levac and colleagues’ method [ 32 ] synthesized the knowledge on the characteristics of flexible at-home respite services offered to caregivers of older adults, from 42 documents. The results provide a synthesis of the characteristics of flexible at-home respite discussed in the literature. The three dimensions of flexibility in respite relate to (1) WHO is tendering it, (2) WHEN it is tendered and (3) HOW it is tendered. First, human resources ( WHO ) must be compatible with the homecare sector as well as being trained and qualified to offer respite to caregivers of older adults. The second feature of flexible respite is temporality ( WHEN ): The time, duration, frequency, and predictability of the service. The last dimension, access ( HOW ), refers to the interface between the respite and the users. Flexible at-home respite exhibits approachability, appropriateness, affordability, availability, and acceptability. In the light of what we learned, flexible at-home respite could be characterized as a service that has the ability to adjust to the needs of the dyad on all three dimensions ( W HO , WHEN , HOW ). However, this seems to be more of an ideal than a reflection of reality.

The survey provided complementary results to the review; the concordance between the two is strong (27/33 = 82%). Six [ 6 ] characteristics were missing from the survey results, including planned respite and the voucher approach ( HOW ). Moreover, the survey added three elements to the review results: The organization’s adhocracy ( HOW ) and promptness ( HOW ) as well as its ability to offer services, regardless of the season ( HOW ). These mismatches might reflect the Québec (and possibly Canadian) landscape of homecare. For example, in the Québec homecare system, respite is mostly planned, it is therefore not surprising that people only mention that unplanned respite is lacking. The “voucher system” was not mentioned in the survey, probably in part because it does not exist in the province of Québec. Additionally, navigating the healthcare system to have free or affordable homecare can be treacherous [ 80 ]. In short, older adults have to go through (1) evaluation(s) by a social worker from a hospital or another public healthcare organization and (2) various administrative tasks ( adhocratic ) [ 2 ], before possibly being put on a waiting list ( prompt ) [ 81 ]. In addition, Canada can experience harsh winters ( seasonality ) that can make transport, which is an integral part of homecare, particularly laborious. Although those categories could reflect the particularity of homecare in Canada, a promising follow up on this review would be to compare the characteristics of flexible respite from one territory to another. It would contribute to providing a more operational definition of flexible at-home respite.

The remainder of this discussion will focus on two main points before touching on the limitations and strengths of this review. First, flexibility in at-home respite seems exceptional. Second, respite care workers are as skilled as they are underappreciated.

This review, in coherence with the literature, highlights the fact that respite services generally lack flexibility: This is the conclusion of several studies on respite [ 7 , 64 , 82 ]. A pattern seems to emerge in the countries represented in the review: Community organizations specialized in homecare (public and/or privately funded) offer respite on predetermined time slots, usually prescribed between traditional office hours (9 AM to 6 PM) [ 50 ]. This lack of flexibility could be explained in part by the rigidity of the structure of homecare services and the fact that its funding does not allow for customizable and punctual services [ 17 , 62 , 73 ]. Nevertheless, there were some examples of flexible respite models, such as Baluchon Alzheimer™ and consumer-directed approaches. Baluchon Alzheimer™ offers long-term at-home respite (4 to 14 days) by qualified and trained baluchonneuses . Prior to the relay of the caregivers, the baluchonneuse takes the time to learn about the dyad, including their environment and routine [ 53 , 62 ]. Caregivers report feeling refreshed upon their return and appreciate the diaries (or logbooks) that the baluchonneuse meticulously fills out [ 53 ]. Another example would be consumer-directed approaches, where caregivers are attributed a budget to hire their own care worker. Allowing caregivers to choose their care worker (either from a self-employed carer or family and friends) can increase the quality of care and satisfaction, while providing relatively affordable care, especially in a situation of labour shortage [ 51 , 79 ]. Even though these two models are a demonstration of how respite can be adapted to the caregiver-senior dyad, for the most part, flexibility is lacking on all three dimensions of respite ( WHO , WHEN , HOW ).

Secondly, the results from the scoping review highlight how homecare as a profession is often overlooked. Indeed, the reviewed documents state the necessary set of skills to offer respite; the level described is one of highly specialized care professionals with important liability. These skills must also transcend advanced knowledge and qualifications, to include interpersonal capabilities [ 17 , 53 , 62 , 63 , 68 ]. Furthermore, care workers must also be flexible to offer a wide range of service time and duration, in addition to being ready to provide “on-the-go” respite [ 53 , 68 ]. Yet, the occupation of homecare worker is an underappreciated and underpaid position [ 83 ]. Community care, like respite, is generally not a priority for social and healthcare funding [ 24 ]. This can be explained in part by the neoliberal approach to care in which the target is to minimize spending and maximize (measurable) outcomes [ 84 ]. Homecare outcomes are often overlooked in favour of service delivery evaluation, in part because they are difficult to measure [ 44 ]. This approach can also lead to prioritizing third party contracting instead of including respite in the range of public services, as to save on expenses related to employment (insurance and other benefits) [ 85 ]. Another contributor is that funding is used for service administration and not to adequately provide services or remunerate care workers [ 86 ]. Finally, care workers are mostly women, known for doing the invisible work that is at the heart of respite care (emotional support, etc.) [ 87 ]. A telling example from the reviewed documents is that Baluchon Alzheimer™ refers to their care workers as baluchonneuses (feminine form) and not baluchoneurs (masculine form) [ 53 ]. Consequently, the homecare sector is faced with recruitment and retention challenges [ 44 , 64 , 88 ]. Authors of the documents included in the review addressed the fact that flexibility in service meant that service providers had to function with excess capacity; for example, by building an “employee bank” to cover all the hours of the day and emergency calls [ 44 ]. Ultimately, staff turnover and shortage caused in part by the work being underappreciated could create a vicious cycle, leading to inflexibility in respite. In short, overlooking and underestimating the crucial and specialized work of homecare workers can contribute to staff turnover, which in turn could result in a lack of flexibility of at-home respite.

Limitations and strengths