An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Malaria 2017: Update on the Clinical Literature and Management

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1301 Morris Park Avenue, Bronx, NY, 10461, USA. [email protected].

- PMID: 28634831

- DOI: 10.1007/s11908-017-0583-8

Purpose of review: Malaria is a prevalent disease in travelers to and residents of malaria-endemic regions. Health care workers in both endemic and non-endemic settings should be familiar with the latest evidence for the diagnosis, management and prevention of malaria. This article will discuss the recent malaria epidemiologic and medical literature to review the progress, challenges, and optimal management of malaria.

Recent findings: There has been a marked decrease in malaria-related global morbidity and mortality secondary to malaria control programs over the last few decades. This exciting progress is tempered by continued levels of high transmission in some regions, the emergence of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Southeast Asia, and the lack of a highly protective malaria vaccine. In the United States (US), the number of travelers returning with malaria infection has increased over the past few decades. Thus, US health care workers need to maintain expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of this infection. The best practices for treatment and prevention of malaria need to be continually updated based on emerging data. Here, we present an update on the recent literature on malaria epidemiology, drug resistance, severe disease, and prevention strategies.

Keywords: Drug resistance in malaria; Malaria control; Malaria epidemiology; Malaria treatment; Post-artemisinin delayed hemolysis; Severe malaria.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2015. Mace KE, Arguin PM, Tan KR. Mace KE, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018 May 4;67(7):1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6707a1. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018. PMID: 29723168 Free PMC article.

- Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2016. Mace KE, Arguin PM, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Mace KE, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019 May 17;68(5):1-35. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6805a1. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019. PMID: 31099769

- Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2014. Mace KE, Arguin PM. Mace KE, et al. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 May 26;66(12):1-24. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6612a1. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017. PMID: 28542123 Free PMC article.

- Geographic expansion of artemisinin resistance. Müller O, Lu GY, von Seidlein L. Müller O, et al. J Travel Med. 2019 Jun 1;26(4):taz030. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taz030. J Travel Med. 2019. PMID: 30995310 Review.

- Recent Advances in Imported Malaria Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management. Weiland AS. Weiland AS. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2023;11(2):49-57. doi: 10.1007/s40138-023-00264-5. Epub 2023 Apr 12. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2023. PMID: 37213266 Free PMC article. Review.

- Hesitancy towards R21/Matrix-M malaria vaccine among Ghanaian parents and attitudes towards immunizing non-eligible children: a cross-sectional survey. Hussein MF, Kyei-Arthur F, Saleeb M, Kyei-Gyamfi S, Abutima T, Sakada IG, Ghazy RM. Hussein MF, et al. Malar J. 2024 May 12;23(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s12936-024-04921-2. Malar J. 2024. PMID: 38734664 Free PMC article.

- Derivatives of Amaryllidaceae Alkaloid Ambelline as Selective Inhibitors of Hepatic Stage of Plasmodium berghei Infection In Vitro. Breiterová KH, Ritomská A, Fontinha D, Křoustková J, Suchánková D, Hošťálková A, Šafratová M, Kohelová E, Peřinová R, Vrabec R, Francisco D, Prudêncio M, Cahlíková L. Breiterová KH, et al. Pharmaceutics. 2023 Mar 21;15(3):1007. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15031007. Pharmaceutics. 2023. PMID: 36986868 Free PMC article.

- Synthesis and Antiplasmodial Activity of Bisindolylcyclobutenediones. Lande DH, Nasereddin A, Alder A, Gilberger TW, Dzikowski R, Grünefeld J, Kunick C. Lande DH, et al. Molecules. 2021 Aug 5;26(16):4739. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164739. Molecules. 2021. PMID: 34443327 Free PMC article.

- 4-Arylthieno[2,3- b ]pyridine-2-carboxamides Are a New Class of Antiplasmodial Agents. Schweda SI, Alder A, Gilberger T, Kunick C. Schweda SI, et al. Molecules. 2020 Jul 13;25(14):3187. doi: 10.3390/molecules25143187. Molecules. 2020. PMID: 32668631 Free PMC article.

- Level of circulating steroid hormones in malaria and cutaneous leishmaniasis: a case control study. Esfandiari F, Sarkari B, Turki H, Arefkhah N, Shakouri N. Esfandiari F, et al. J Parasit Dis. 2019 Mar;43(1):54-58. doi: 10.1007/s12639-018-1055-2. Epub 2018 Nov 20. J Parasit Dis. 2019. PMID: 30956446 Free PMC article.

- Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015 Jul;93(1):125-134 - PubMed

- Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016 Apr;32(4):227-231 - PubMed

- Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013 Apr;26(2):165-84 - PubMed

- PLoS Biol. 2016 Mar 02;14(3):e1002380 - PubMed

- J Clin Microbiol. 2017 Jul;55(7):2009-2017 - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources, other literature sources.

- scite Smart Citations

Research Materials

- NCI CPTC Antibody Characterization Program

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Download PDF

- CME & MOC

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Malaria in the US : A Review

- 1 Department of Medicine (Infectious Diseases), Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York

- 2 D. Samuel Gottesman Library, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York

- Medical News & Perspectives Vaccine Development Is Charting a New Path in Malaria Control Bridget M. Kuehn, MSJ JAMA

- JAMA Patient Page Patient Information: Malaria Kristin Walter, MD, MS; Chandy C. John, MD, MS JAMA

- Global Health Updated Malaria Recommendations for Children and Pregnant People Howard D. Larkin JAMA

- Medical News in Brief First Ever Malaria Vaccine to Be Distributed in Africa Emily Harris JAMA

Importance Malaria is caused by protozoa parasites of the genus Plasmodium and is diagnosed in approximately 2000 people in the US each year who have returned from visiting regions with endemic malaria. The mortality rate from malaria is approximately 0.3% in the US and 0.26% worldwide.

Observations In the US, most malaria is diagnosed in people who traveled to an endemic region. More than 80% of people diagnosed with malaria in the US acquired the infection in Africa. Of the approximately 2000 people diagnosed with malaria in the US in 2017, an estimated 82.4% were adults and about 78.6% were Black or African American. Among US residents diagnosed with malaria, 71.7% had not taken malaria chemoprophylaxis during travel. In 2017 in the US, P falciparum was the species diagnosed in approximately 79% of patients, whereas P vivax was diagnosed in an estimated 11.2% of patients. In 2017 in the US, severe malaria, defined as vital organ involvement including shock, pulmonary edema, significant bleeding, seizures, impaired consciousness, and laboratory abnormalities such as kidney impairment, acidosis, anemia, or high parasitemia, occurred in approximately 14% of patients, and an estimated 0.3% of those receiving a diagnosis of malaria in the US died. P falciparum has developed resistance to chloroquine in most regions of the world, including Africa. First-line therapy for P falciparum malaria in the US is combination therapy that includes artemisinin. If P falciparum was acquired in a known chloroquine-sensitive region such as Haiti, chloroquine remains an alternative option. When artemisinin-based combination therapies are not available, atovaquone-proguanil or quinine plus clindamycin is used for chloroquine-resistant malaria. P vivax, P ovale, P malariae, and P knowlesi are typically chloroquine sensitive, and treatment with either artemisinin-based combination therapy or chloroquine for regions with chloroquine-susceptible infections for uncomplicated malaria is recommended. For severe malaria, intravenous artesunate is first-line therapy. Treatment of mild malaria due to a chloroquine-resistant parasite consists of a combination therapy that includes artemisinin or chloroquine for chloroquine-sensitive malaria. P vivax and P ovale require additional therapy with an 8-aminoquinoline to eradicate the liver stage. Several options exist for chemoprophylaxis and selection should be based on patient characteristics and preferences.

Conclusions and Relevance Approximately 2000 cases of malaria are diagnosed each year in the US, most commonly in travelers returning from visiting endemic areas. Prevention and treatment of malaria depend on the species and the drug sensitivity of parasites from the region of acquisition. Intravenous artesunate is first-line therapy for severe malaria.

Read More About

Daily JP , Minuti A , Khan N. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Malaria in the US : A Review . JAMA. 2022;328(5):460–471. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.12366

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Cardiology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Advertisement

A review on automated diagnosis of malaria parasite in microscopic blood smears images

- Published: 09 March 2017

- Volume 77 , pages 9801–9826, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Zahoor Jan 1 ,

- Arshad Khan 1 ,

- Muhammad Sajjad 1 ,

- Khan Muhammad 1 , 2 ,

- Seungmin Rho 3 &

- Irfan Mehmood 4

2651 Accesses

37 Citations

Explore all metrics

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasite of genus plasmodium, which is transmitted through the bite of infected Anopheles. A rapid and accurate diagnosis of malaria is demanded for proper treatment on time. Mostly, conventional microscopy is followed for diagnosis of malaria in developing countries, where pathologist visually inspects the stained slide under light microscope. However, conventional microscopy has occasionally proved inefficient since it is time consuming and results are difficult to reproduce. Alternate techniques for malaria diagnosis based on computer vision were proposed by several researchers. The aim of this paper is to review, analyze, categorize and address the recent developments in the area of computer aided diagnosis of malaria parasite. Research efforts in quantification of malaria infection include normalization of images, segmentation followed by features extraction and classification, which were reviewed in detail in this paper. At the end of review, the existent challenges as well as possible research perspectives were discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Automatic detection of Plasmodium parasites from microscopic blood images

Detection of Malaria Parasite Based on Thick and Thin Blood Smear Images Using Local Binary Pattern

Detection of Plasmodium Falciparum in Peripheral Blood Smear Images

Abdul-Nasir AS, Mashor MY, Mohamed Z (2012) Modified global and modified linear contrast stretching algorithms: new colour contrast enhancement techniques for microscopic analysis of malaria slide images. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, vol. 2012. Article ID 637360, p 16

Aimi Salihah A-N, Yusoff M, Zeehaida M (2013) Colour image segmentation approach for detection of malaria parasites using various colour models and k-means clustering. Wseas Transactions on Biology and Biomedicine, vol. 10

Malaria Site – History, Pathogenesis, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Treatment, Complications and Control of Malaria. (n.d.). Retrieved September, 2015, from: http://www.malariasite.com

Anggraini D et al (2011) Automated status identification of microscopic images obtained from malaria thin blood smears. In Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), 2011 International conference on. 17:347–352 IEEE

Arco J et al (2015) Digital image analysis for automatic enumeration of malaria parasites using morphological operations. Expert Systems with Applications, 42(6):3041–3047

World Health Organization. (2010). Basic malaria microscopy: Part I. Learner's guide. Basic malaria microscopy: Part I. Learner's guide., (Ed. 2)

Bates, I., Bekoe, V., & Asamoa-Adu, A. (2004). Improving the accuracy of malaria-related laboratory tests in Ghana. Malaria Journal, 3(1):38

Bernard Marcus PD (2009) Deadly diseases and epidemics: malaria. Chelsea House Publishers, New York, Second Edition ed

Google Scholar

Chakrabortya K et al (2015) A combined algorithm for Malaria detection from thick smear blood slides J Health Med Inform 2015

Chayadevi M, Raju G (2015) Automated colour segmentation of malaria parasite with fuzzy and fractal methods. In Computational Intelligence in Data Mining-Volume (3):53–63. Springer India

Dallet C, Kareem S, Kale I (2014) Real time blood image processing application for malaria diagnosis using mobile phones. In Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), 2014 IEEE International Symposium on p 2405–2408. IEEE

Damahe LB, Krishna R, Janwe N (2011) Segmentation based approach to detect parasites and RBCs in blood cell images. Int J Comput Sci Appl 4:71–81

Das DK et al (2013) Machine learning approach for automated screening of malaria parasite using light microscopic images. Micron 45:97–106

Article Google Scholar

Devi RR et al (2011) Computerized shape analysis of erythrocytes and their formed aggregates in patients infected with P.Vivax Malaria . Advanced Computing: An International Journal (ACIJ) 2

Di Ruberto C et al (2002) Analysis of infected blood cell images using morphological operators. Image and vision computing 20(2):133–146

Di Rubeto C et al (2000) Segmentation of blood images using morphological operators. in Pattern Recognition. Proceedings. 15th International Conference on. IEEE

Díaz G, González FA (2009) E Romero, A semi-automatic method for quantification and classification of erythrocytes infected with malaria parasites in microscopic images . J Biomed Inform 42(2):296–307

Gatc J et al (2013) Plasmodium parasite detection on Red Blood Cell image for the diagnosis of malaria using double thresholding. In Advanced Computer Science and Information Systems (ICACSIS), 2013 International conference on. IEEE

Ghosh M et al (2011) Plasmodium vivax segmentation using modified fuzzy divergence. In Image Information Processing (ICIIP), 2011 International conference on. IEEE

Ghosh S, Ghosh A, Kundu S (2014) Estimating malaria parasitaemia in images of thin smear of human blood. CSI transactions on ICT 2(1):43–48

Gitonga L et al (2014) Determination of plasmodium parasite life stages and species in images of thin blood smears using artificial neural network. Open J Clin Diag 4(02):78

Gual-Arnau X, Herold-García S, Simó A (2015) Erythrocyte shape classification using integral-geometry-based methods. Med Biol Eng Comput 53(7):623–633

Halim S et al (2006) Estimating malaria parasitaemia from blood smear images. In 2006 9th international conference on control, automation, robotics and vision. IEEE

Hanif N, Mashor M, Mohamed Z (2011) Image enhancement and segmentation using dark stretching technique for Plasmodium Falciparum for thick blood smear. In Signal Processing and its Applications (CSPA), 2011 I.E. 7th international colloquium on. IEEE

Heijmans HJ (1999) Connected morphological operators for binary images. Comput Vis Image Underst 73(1):99–120

Article MathSciNet MATH Google Scholar

Hung Y-W et al (2015) Parasite and infected-erythrocyte image segmentation in stained blood smears. J Med Biol Eng 35(6):803–815

Kaewkamnerd S et al (2012) An automatic device for detection and classification of malaria parasite species in thick blood film. Bmc Bioinformatics, 13(17), S18

Kareem S, Kale I, Morling RC (2012a) Automated P. falciparum detection system for post-treatment malaria diagnosis using modified annular ring ratio method. In Computer Modelling and Simulation (UKSim), 2012 UKSim 14th International Conference on p 432–436. IEEE

Kareem S, Kale I, Morling RS (2012b) Automated malaria parasite detection in thin blood films:-A hybrid illumination and color constancy insensitive, morphological approach. In Circuits and Systems (APCCAS), 2012 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on p 240–243. IEEE.

Kareem S, Morling RS, Kale I (2011) A novel method to count the red blood cells in thin blood films. In 2011 I.E. international symposium of circuits and systems (ISCAS). IEEE

Khan MI et al (2011) Content based image retrieval approaches for detection of malarial parasite in blood images. Intern J Biom Bioinform (IJBB) 5(2):97

Khan NA et al (2014) Unsupervised identification of malaria parasites using computer vision. In Computer Science and Software Engineering (JCSSE), 2014 11th international joint conference on. IEEE

Khatri K et al (2013) Image processing approach for malaria parasite identification. In International Journal of Computer Applications, National Conference on Growth of Technologies in Electronics, Telecom and Computers-India's Perception. Citeseer

Khattak AA et al (2013) Prevalence and distribution of human plasmodium infection in Pakistan. Malar J 12(1):297

Komagal E, Kumar KS, Vigneswaran A (2013) Recognition and classification of malaria plasmodium diagnosis. ESRSA Publications, In International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology

Kotsiantis SB, Zaharakis I, Pintelas P (2007) Supervised machine learning: a review of classification techniques

Kumar A et al (2012) Enhanced identification of malarial infected objects using otsu algorithm from thin smear digital images. International Journal of Latest Research in Science and Technology ISSN (Online) 2278–5299

Kumarasamy SK, Ong S, Tan KS (2011) Robust contour reconstruction of red blood cells and parasites in the automated identification of the stages of malarial infection. Machine Vision and Applications 22(3):461–469

Le M-T et al (2008) A novel semi-automatic image processing approach to determine plasmodium falciparum parasitemia in Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. BMC Cell Biol 9(1):15

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Lee H, Chen Y-PP (2014) Cell morphology based classification for red cells in blood smear images. Pattern Recogn Lett 49:155–161

Linder N et al (2014) A malaria diagnostic tool based on computer vision screening and visualization of plasmodium falciparum candidate areas in digitized blood smears. PLoS One 9(8):e104855

Maiseli B et al (2014) An automatic and cost-effective parasitemia identification framework for low-end microscopy imaging devices. In Mechatronics and Control (ICMC), 2014 International conference on p 2048–2053. IEEE

Makkapati VV, Rao RM (2009) Segmentation of malaria parasites in peripheral blood Smear images. In 2009 I.E. international conference on acoustics, speech and signal processing. IEEE

Malaria disease concepts. Sept 2015. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/

Malaria. (n.d.). Retrieved September, 2015, from: http://www.who.int/malaria/en/

Malihi L, Ansari-Asl K, Behbahani A (2013) Malaria parasite detection in giemsa-stained blood cell images. In Machine Vision and Image Processing (MVIP), 2013 8th Iranian Conference on IEEE

Mandal S et al (2010) Segmentation of blood smear images using normalized cuts for detection of malarial parasites. In 2010 Annual IEEE India conference (INDICON). IEEE

Mas D et al (2015) Novel image processing approach to detect malaria. Opt Commun 350:13–18

Mushabe MC, Dendere R, Douglas TS (2013) Automated detection of malaria in Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. In 2013 35th annual international conference of the IEEE engineering in medicine and biology society (EMBC). IEEE

Nixon, M., Feature extraction & image processing . 2008: Academic press, Cambridge.

Nugroho AS et al (2014) Two-stage feature extraction to identify Plasmodium ovale from thin blood smear microphotograph. In Data and Software Engineering (ICODSE), 2014 International conference on. IEEE

Okwa, O.O. (2012). Malaria parasites. InTech. doi: 10.5771/1477

Organization WH (2009) Malaria microscopy quality assurance manual. World Health Organization

Otsu N (1975) A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. Automatica 11(285–296):23–27

Prasad K et al (2012) Image analysis approach for development of a decision support system for detection of malaria parasites in thin blood smear images. J Digit Imaging 25(4):542–549

Premaratne SP et al (2003) A neural network architecture for automated recognition of intracellular malaria parasites in stained blood films. CJ Janse and PH Van Vianen,. Flow cytometry in malaria detection. Methods Cell. Biol 42.

Purwar Y et al (2011) Automated and unsupervised detection of malarial parasites in microscopic images. Malar J 10(1):1

Rakshit P, Bhowmik K (2013) Detection of presence of parasites in human RBC in case of diagnosing malaria using image processing. In Image Information Processing (ICIIP), 2013 I.E. second international conference on. IEEE

Raviraja S, Bajpai G, Sharma SK (2007) Analysis of detecting the Malarial parasite infected blood images using statistical based approach. In 3rd Kuala Lumpur International Conference on Biomedical Engineering 2006. Springer

Rosado L et al (2016) Automated detection of malaria parasites on thick blood smears via mobile devices. Procedia Com Sci 90:138–144

Ross NE et al (2006) Automated image processing method for the diagnosis and classification of malaria on thin blood smears. Med Biol Eng Comput 44(5):427–436

Sajjad M, Khan S, Jan Z, Muhammad K, Moon H, Kwak JT, Mehmood I (2016) Leukocytes classification and segmentation in microscopic blood smear: a resource-aware healthcare service in smart cities. IEEE. DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2636218

Savkare S, Narote S (2012) Automatic system for classification of erythrocytes infected with malaria and identification of parasite's life stage. Procedia Technol 6:405–410

Savkare S, Narote S (2015) Automated system for malaria parasite identification. in Communication, Information & Computing Technology (ICCICT), 2015 International Conference on IEEE

Sheeba F et al (2013) Detection of plasmodium falciparum in peripheral blood smear images. In Proceedings of Seventh International Conference on Bio-Inspired Computing: Theories and Applications (BIC-TA 2012). Springer

Annaldas MS, Shirgan SS & Marathe VR (2014) Enhanced identification of malaria parasite using different classification algorithms in thick film blood images. Int J Res Advent Technol 2(10)

Singh A, Shibu S, Dubey S (2014) Recent image enhancement techniques: a review. Intern J Eng Advanc Technol 4(1):40–45

Sio SW et al (2007) MalariaCount: an image analysis-based program for the accurate determination of parasitemia. J Microbiol Methods 68(1):11–18

Somasekar J, Reddy BE (2015) Segmentation of erythrocytes infected with malaria parasites for the diagnosis using microscopy imaging. Comput Electr Eng 45:336–351

Somasekar, J., et al., An image processing approach for accurate determination of parasitemia in peripheral blood smear images . International Journal of Computer Applications 23–28

Soni J (2011) Advanced image analysis based system for automatic detection of malarial parasite in blood images using SUSAN approach. Int J Eng Sci Technol 3(6):5260–5274

Suradkar PT (2013) Detection of malarial parasite in blood using image processing. Int J Eng Innov Technol (IJEIT) 2(10)

Suryawanshi MS, Dixit V (2013) Improved technique for detection of malaria parasites within the blood cell images. Int J Sci Eng Res 4:373–375

Suwalka I et al (2012) Identify malaria parasite using pattern recognition technique. In Computing, Communication and Applications (ICCCA), 2012 International Conference on p. 1–4 IEEE

Tek FB (2007) Computerised diagnosis of malaria. University of Westminster

Tek FB, Dempster AG, Kale I (2006) Malaria parasite detection in peripheral blood images. In BMVC

Tek FB, Dempster AG, Kale I (2009) Computer vision for microscopy diagnosis of malaria. Malaria Journal 8(1):153

Tek FB, Dempster AG, Kale İ (2010) Parasite detection and identification for automated thin blood film malaria diagnosis. Comput Vis Image Underst 114(1):21–32

Toha SF, Ngah UK (2007) Computer aided medical diagnosis for the identification of malaria parasites. In 2007 International conference on signal processing, communications and networking. IEEE

Tsai M-H et al (2015) Blood smear image based malaria parasite and infected-erythrocyte detection and segmentation. Journal of medical systems 39(10):118

Warhurst, D.C. and J.E. Williams, ACP Broadsheet no 148. July 1996 . Laboratory diagnosis of malaria . J Clin Pathol 1996 49(7): p. 533–538.

What is Malaria? 2015. Available from: http://www.healthline.com/health/malaria

Widodo S (2014) Texture analysis to detect malaria tropica in blood smears image using support vector machine

World Malaria Report (2014) World Health Organization

Yunda L, Alarcón A, Millán J (2012) Automated image analysis method for p-vivax malaria parasite detection in thick film blood images. Sistemas y Telemática 10(20):9–25

Zhang D, Lu G (2004) Review of shape representation and description techniques. Pattern Recogn 37(1):1–19

Zou L-H et al (2010) Malaria cell counting diagnosis within large field of view. In Digital Image Computing: In Digital Image Computing: Techniques and Applications (DICTA), 2010 International Conference on p. 172–177 IEEE.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016R1D1A1A09919551).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Digital Image Processing Laboratory, Department of Computer Science, Islamia College Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan

Zahoor Jan, Arshad Khan, Muhammad Sajjad & Khan Muhammad

Intelligent Media Laboratory, Digital Contents Research Institute, College of Electronics and Information Engineering, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Khan Muhammad

Department of Media Software, Sungkyul University, Anyang, Republic of Korea

Seungmin Rho

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Sejong University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

Irfan Mehmood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Irfan Mehmood .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Jan, Z., Khan, A., Sajjad, M. et al. A review on automated diagnosis of malaria parasite in microscopic blood smears images. Multimed Tools Appl 77 , 9801–9826 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4495-2

Download citation

Received : 13 June 2016

Revised : 15 November 2016

Accepted : 08 February 2017

Published : 09 March 2017

Issue Date : April 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4495-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Malaria parasite

- Red blood cells

- Parasite segmentation

- Thin blood smear

- Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 03 February 2023

Leveraging innovation technologies to respond to malaria: a systematized literature review of emerging technologies

- Moredreck Chibi 1 ,

- William Wasswa 1 ,

- Chipo Ngongoni 1 ,

- Ebenezer Baba 2 &

- Akpaka Kalu 2

Malaria Journal volume 22 , Article number: 40 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

6020 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

In 2019, an estimated 409,000 people died of malaria and most of them were young children in sub-Saharan Africa. In a bid to combat malaria epidemics, several technological innovations that have contributed significantly to malaria response have been developed across the world. This paper presents a systematized review and identifies key technological innovations that have been developed worldwide targeting different areas of the malaria response, which include surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis and management.

A systematized literature review which involved a structured search of the malaria technological innovations followed by a quantitative and narrative description and synthesis of the innovations was carried out. The malaria technological innovations were electronically retrieved from scientific databases that include PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, IEEE and Science Direct. Additional innovations were found across grey sources such as the Google Play Store, Apple App Store and cooperate websites. This was done using keywords pertaining to different malaria response areas combined with the words “innovation or technology” in a search query. The search was conducted between July 2021 and December 2021. Drugs, vaccines, social programmes, and apps in non-English were excluded. The quality of technological innovations included was based on reported impact and an exclusion criterion set by the authors.

Out of over 1000 malaria innovations and programmes, only 650 key malaria technological innovations were considered for further review. There were web-based innovations (34%), mobile-based applications (28%), diagnostic tools and devices (25%), and drone-based technologies (13%.

Discussion and conclusion

This study was undertaken to unveil impactful and contextually relevant malaria innovations that can be adapted in Africa. This was in response to the existing knowledge gap about the comprehensive technological landscape for malaria response. The paper provides information that countries and key malaria control stakeholders can leverage with regards to adopting some of these technologies as part of the malaria response in their respective countries.

The paper has also highlighted key drivers including infrastructural requirements to foster development and scaling up of innovations. In order to stimulate development of innovations in Africa, countries should prioritize investment in infrastructure for information and communication technologies and also drone technologies. These should be accompanied by the right policies and incentive frameworks.

In sub-Saharan Africa, malaria is the leading cause of death for children under 5. It has been reported that malaria infection during pregnancy increases the risk of maternal mortality and neonatal mortality [ 1 ]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there were 229 million cases of malaria in 2019 compared to 228 million cases in 2018. The estimated number of malaria deaths stood at 409,000 in 2019, compared with 411,000 deaths in 2018. Children under 5 years of age are the most vulnerable group affected by malaria and in 2019 they accounted for 67% (274,000) of all malaria deaths worldwide. The WHO African Region continues to carry a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden. In 2019, the region was home to 94% of all malaria cases and deaths with six countries accounting for approximately half of all malaria deaths worldwide: Nigeria (23%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (11%), United Republic of Tanzania (5%), Burkina Faso (4%), Mozambique (4%) and Niger (4%) [ 2 ].

Knowledge, learning and innovation are key to addressing, minimizing and tackling these disparities. One example of this is the knowledge hub developed by WHO called MAGICapp which aims to give living evidence and resources for tackling malaria interventions. It contains all official WHO recommendations for malaria prevention (vector control and preventive chemotherapies) and case management (diagnosis and treatment). The resources serve as a guide on the strategic use of information to drive impact, surveillance, monitoring and evaluation; operational manuals, handbooks, and frameworks; and a glossary of key terms and definitions. So, this paper aligns with identifying and adding discourse into the importance of reviews especially from a technological perspective.

To understand the advances in malaria services, various scholars have undertaken reviews across vast thematic areas of malaria interventions. In a quest to inform policy, Garner et al. [ 3 ] conducted an analysis of why Cochrane Reviews are important in malaria interventions. They noted that it is important for researchers to collaborate across regions and in understanding new preventive interventions. Their aim was to inform policymakers to understand the importance of reviews in identification of trends that are occurring in malaria interventions. Other aspects that have been looked at through reviews are the costs and cost-effectiveness aligned with malaria control interventions. White et al. [ 4 ] looked at interventions from studies published between 2000 and 2010 looking at the role of infection detection technologies for malaria elimination and eradication and the costs related to them in order to assess how accessible interventions are across regions. More recently, Conteh et al. [ 5 ] also carried on with assessing the unit cost and cost-effectiveness of malaria control during the period of January 1, 2005, and August 31, 2018. The aim was to see how resource allocation can be planned proactively according to costs, though they did highlight that care in methodological and reporting standards is required to enhance data transferability.

In a bid to combat malaria epidemic, several technological innovations have been developed all over the world that have contributed significantly to malaria response. Adeola et al. [ 6 ] reviewed the use of spatial technology for malaria epidemiology in South Africa between 1930 and 2013. The focus was on the use of statistical and mathematical models as well as geographic information science (GIS) and remote sensing (RS) technology for malaria research to create a robust malaria warning system. The mathematical modelling is also aligned with agent-based modelling which Smith et al. [ 7 ] highlighted through their analysis of 90 articles published between 1998 and May 2018 characterizing agent-based models (ABMs) relevant to malaria transmission. The aim was to provide an overview of key approaches utilized in malaria prevention. Such technologies feed into modelling sites and interventions to project various outcomes. From a platform centric perspective, Vasiman et al. [ 8 ] analysed how different mobile phone devices and handheld microscopes work as diagnostic platforms for malaria in low-resource settings. Malaria diagnostics tests and methods have also been reviewed as being key in the successful control and elimination programmes [ 9 ]. Mobile health has been found to play a key role in supporting health workers in the diagnosis and treatment of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa [ 10 ].

To add to this discourse, this paper presents a holistic systematized review of key technological innovations that have been developed worldwide targeting different areas of the malaria response, which include surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis, and management. A systematized review was utilized in this study as data sources that included unconventional grey sources was utilized and the review gravitated more towards being narrative with tabular accompaniments as compared to the systematic literature reviews that are less narrative [ 11 ]. The study was undertaken with the view to provide African countries and key stakeholders with information relating to technologies that can be adapted in their different contexts as they strengthen malaria response strategies.

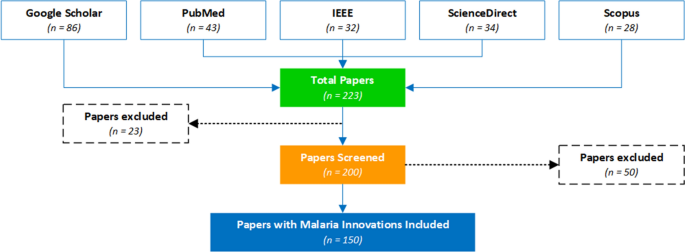

Scientific databases literature search

This study adopted a systematic search strategy to identify the publications with innovations related to malaria surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis, and management from 5 scientific databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, IEEE and Science Direct). The keywords used were malaria surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis and management combined with the words “innovations” or “technologies” in a search query. Innovations deemed not relevant to the scope of this research by the authors include drugs, vaccines, social programmes. Only papers reporting design, implementation or evaluation of malaria technological innovations were considered in this paper. The process was shown in Fig. 1 . The quality of technological innovations included was based on reported impact and judgement by the authors.

PRISMA flow chart for the malaria innovations literature search

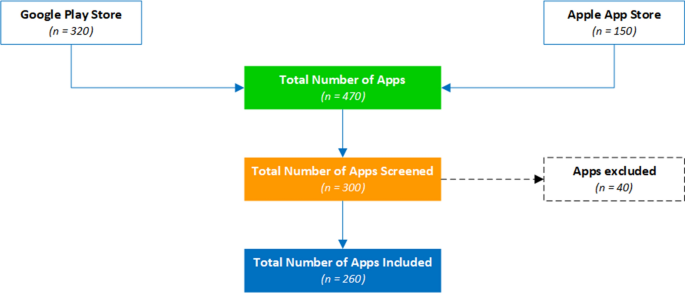

Search through technology platforms e.g., google play store and apple app store

This study also adopted a systematic search strategy to identify the mobile apps related to malaria surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis and management available in the Google Play and Apple App stores. Keywords such as malaria surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis, and management were used in the search. The search was conducted between July 2021 and December 2021. The applications had to have a description, be in English, have 1000 + installs and reviews to be included in the analysis. The applications that did not meet these criteria were excluded. The core research question was: What mobile-based innovations are available for malaria interventions that can be adopted by the countries in the WHO Africa region for use across the continuum of the malaria response ? The resultant apps considered for this study were 260 as shown in Fig. 2 .

PRISMA flow chart for the mobile apps

Web search using a custom web-content mining algorithm

A custom web-content mining algorithm was also developed to search for malaria innovations and technologies published on different cooperate organizational websites, social media channels like twitter, and media channels like legit news websites like CNN. These technological innovations were collated between July 2021 and December 2021. The innovation name, description, Intellectual Property owner, web link to the innovation and geographical location were collated. Innovations that did not have functional and tested prototypes and were not related to addressing malaria interventions were excluded. The number of innovations surpassed 1000 however after screening, only 240 key technological innovations were selected that best fit the selection criteria.

A total of 650 malaria innovations (260 from Google play and Apple App store, 150 from scientific databases and 240 from web content mining) were considered for detailed review.

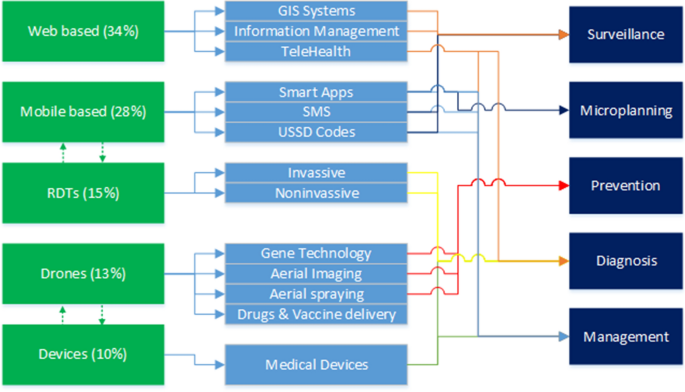

The review has identified innovations for malaria in the following technological thematic areas; web-based innovations (34%), mobile-based applications (28%), diagnostic tools and other devices (25%), and drone-based technologies (13%).

Web-based innovations

The web-based technologies include GIS systems [ 12 ]. An example is the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP), developed at the Telethon Kids Institute, Perth, Western Australia. MAP is a web platform that displays time aware raster and survey point data for malaria incidence, endemicity, and mosquito distribution. MAP has been designated as a WHO Collaborating Centre in Geospatial Disease Modelling. The impact of the Atlas Project has been validated in Sokoto Nigeria by Nakakana et al. [ 13 ]. The study concluded that the prevalence of malaria and its transmission intensity in Sokoto are similar to the Malaria Atlas Project predictions for the area and that is essential in modellings various aspects of malaria control planning purposes.

Other innovations like malariaAtlas which is an open-access R-interface on the Malaria Atlas Project, collates malariometric data, providing reproducible means of accessing such data within a freely available and commonly used statistical software environment [ 14 ]. A team from the University of Queensland developed a GIS-based spatial decision support system (SDSS) used to automatically locate and map the distribution of confirmed malaria cases, rapidly classify active transmission foci, and guide targeted responses in elimination zones. This has been implemented and evaluated in the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu in a study by Kelly et al. [ 15 ] and 82.5% of confirmed malaria cases were automatically geo-referenced and mapped at the household level, with 100% of remaining cases geo-referenced at a village level using the system. The GIS-based spatial decision support system has also been implemented in other countries like Vietnam. In Korea, the Malaria Vulnerability Map Mobile System which consists of a system database construction, malaria risk calculation function, visual expression function, and website and mobile application has been developed for use in Incheon [ 16 ]. The Malaria Decision Analysis Support Tool (MDAST) project promotes evidence-based, multi-sectoral malaria control policy-making in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, serving as a pilot for such a programme in other malaria-prone countries [ 17 ].

In Zanzibar, the Malaria Case Notification (MCN) System was developed and the performance evaluation of the tool by Khandekar [ 18 ] showed that while a surveillance system can automate data collection and reporting, its performance will still rely heavily on health worker performance, community acceptance, and infrastructure within a country. A study by Mody et al. [ 19 ] showed that the use of telemedicine and e-health technologies shows promise for the remote diagnosis of malaria and hence several systems been developed. ProMED Mail (PMM) is an open and free to use, global, e-health based surveillance system from the International Society for Infectious Diseases with several use cases for malaria [ 20 , 21 ]. The Epidemic Prognosis Incorporating Disease and Environmental Monitoring for Integrated Assessment (EPIDEMIA) computer system was designed and implemented to integrate disease surveillance with environmental monitoring in support of operational malaria forecasting in the Amhara region of Ethiopia [ 22 ]. Table 1 summarizes some of the technologies.

Mobile applications-based technologies

This study has also revealed that several mobile-based malaria innovations have been developed which include smart mobile apps, Short Message Service (SMS) based apps and Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) based applications for use across the continuum of the malaria response. In India the Mobile-based Surveillance Quest using IT (MoSQuIT) is being used to automate and streamline malaria surveillance for all stakeholders involved, from health workers in rural India to medical officers and public health decision-makers. Malaria Epidemic Early Detection System (MEEDS) is a groundbreaking mHealth system used in Zanzibar by health facilities to report new malaria cases through mobile phones. Coconut Surveillance is an open-source mobile software application designed by malaria experts specifically for malaria control and elimination and it has become an essential tool for the Zanzibar Malaria Elimination Programme [ 23 ]. The SMS for Life initiative is a ‘public-private’ project that harnesses everyday technology to eliminate stock-outs and improve access to essential medicines in sub-Saharan Africa with a health focus on malaria and other vector borne diseases. This has been implemented and evaluated in Tanzania [ 24 ]. In Mozambique Community Health Workers (CHWs) use inSCALE CommCare tool for decision support, immediate feedback and multimedia audio and images to improve adherence to protocols.

Additional surveillance apps include the likes of the DHS mobile app for Malaria Indicator Surveys and Solution for Community Health-workers (SOCH) mobile app is a comprehensive mobile application tool for disease surveillance, workforce management and supply chain management for malaria elimination [ 25 ]. The National Malaria Case-Based Reporting App (MCBR) is a mobile phone application for malaria case-based reporting to advance malaria surveillance in Myanmar [ 26 ]. Mobile apps have also been used to support distribution of medicines like the Net4Schs App, an android application that is used for data capturing, processing and reporting on School Long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) distribution activities. Apps have also been developed to support malaria screening and diagnosis for example the NLM Malaria Screener is a diagnostic app that assists users in the diagnosis of malaria and in the monitoring of malaria patients. This has been validated in several studies and it is reported that it makes the screening process faster, more consistent, and less dependent on human expertise [ 27 ]. Additional diagnostic apps include the Malaria System MicroApp which is a mobile device-based tool for malaria diagnosis [ 28 ], the Malaria Hero app is a web based mobile app for diagnosis of malaria, and LifeLens is a smartphone app that can detect malaria. Some key technologies are summarized in Table 2 .

Other notable mobile apps that have also been used in malaria management include CommCare’s usage in in Mozambique for integrated community case management in the remote communities. This has been reported to strengthen Community-Based Health [ 29 ]. Another app, FeverTracker, has been used for malaria surveillance and patient information management in India. There has also been a number of educational and knowledge base apps. These are the likes of Malaria Consultant, a mobile application designed to educate individuals on malaria and its prevention; the WHO Malaria toolkit App that brings together the content of the latest world malaria report and of the consolidated WHO Guidelines for malaria. This includes operational manuals for carrying out malaria interventions and other technical documents in one easy to navigate resource. Another interesting area where mobile apps have been used is in malaria prevention and such apps include those that scare away mosquitoes using high frequency sounds, and these include Anti Mosquito Repellent Sound App.

Drone-based technologies

This review has revealed that drone technologies can greatly help in malaria control programmes. The drones can be used in developing genetically-based vector control tools [ 30 ], delivering massive aerial spraying to kill mosquito larvae [ 31 ], identifying mosquito larvae sites using aerial imaging [ 32 ] and in delivering drugs and vaccines [ 33 ]. Anti-malaria drones have been widely used to spray biological insecticides in rice fields and swamps to reduce the emerging mosquito populations. This has been successful in Kenya, Tanzania, India, Rwanda and Zanzibar. In Zanzibar, the Agras MG-1S drones were used to spray 10 L of a biodegradable agent called Aquatain; a chemical that has been used to cover drinking water basins. Drones have also been used to collect data to identify mosquito breeding sites so that the larvae can be controlled, reducing the number of adult mosquitoes able to spread malaria. For example in Malawi and near Lake Victoria the DJI Phantom low-cost drones are being used to survey and find mosquito breeding grounds. A new trial using ‘gene drive’ technology is currently taking place in Burkina Faso where the trial will see the release of genetically modified mosquitoes in an attempt to wipe out the female carriers of the disease [ 34 ].

Diagnostic tools including other devices developed for malaria interventions

Devices that have been developed to respond to malaria include the SolarMal device, a solar-powered mosquito trapper being piloted in Kenya [ 35 ]. The Solar Powered Mosquito Trap (SMOT) is baited with a synthetic odor blend that mimics human odor to lure host-seeking malaria mosquitoes. Other devices such as the ThermaCell Patio Shield Mosquito Repellants developed by ThermaCell are shield lanterns that repel mosquitoes by creating a 15-foot zone of protection. Several devices have also been developed to improve malaria diagnosis and these include the Nanomal DNA analyzer a simple, rapid and affordable point-of-care (POC) handheld diagnostic nanotechnology device to confirm malaria diagnosis and detect drug resistance in malaria parasites in minutes and at the patient’s side, by analysis of mutations in malaria DNA using a range of proven nanotechnologies. Medication Events Monitoring Device (MEMS) have also been greatly used to monitor medication adherence to malaria drugs [ 36 ]. Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs), sometimes called dipsticks or Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Devices (MRDDS), are simple immunochromatographic tests that identify specific antigens of malaria parasites in whole or peripheral blood. They are categorized into dipstick, cassette or hybrids. Dipstick RDTs are cheap and readily available on market [ 37 ]. An example is the OptiMAL dipstick [ 38 ]. Cassette RDTS are complex and require much time for results to be read but are much safer to use.

This research has culminated into insightful conclusions from the systematized review of the malaria technological Innovations and has been the foundation of the collated database that can be accessed via the WHO AFRO marketplace platform. This is a platform that has been developed to showcase various technologies and innovations that can be applied for different disease areas. This focused on technologies relevant for malaria response. The identified intervention technologies and focus areas provide ways of identifying key leverage points in strengthening the health systems and making tangible impact towards various mandates to fight the scourge of malaria. More importantly highlighting these trends empowers innovators and policy makers on the continent to make informed decisions on applying frugal design to develop affordable, locally manufactured, functional and sustainable innovations fit for the African continent. Furthermore, the marketplace platform provides implementation insights to African nations on the adoption of some of the technological innovations from this study.

The review has highlighted that mobile applications are a vital component of malaria response programmes and are increasingly being used along the different response areas, such as surveillance (malaria data capturing apps like Coconut Surveillance and DHS mobile app), microplanning (drug delivery and distribution management apps like Net4Schs App), prevention (mosquito repelling like Anti Mosquito Repellent Sound App), diagnosis (AI driven slide analysis apps like LifeLens and Malaria Screener), management (telehealth like the Malaria Consultant) and the provision of support for health services [decision support like the solution for Community Health-workers (SOCH) app] as outlined in Fig. 3 . Their impact has been validated in several studies [ 27 , 39 ].

Analysis of the innovations by category, application and target outcome

In 2019, 93% of the global population was covered by a mobile broadband signal. In Sub-Saharan Africa, 3G coverage expanded to 75% compared to 63% in 2017, while 4G doubled to nearly 50% compared to 2017 [ 40 ]. This implies that mobile solutions can substantially mitigate many of the health system limitations prevalent mostly in African countries where malaria is endemic. A substantial number of mobile applications have been developed for surveillance of malaria control programs in Africa such as inSCALE (Mozambique), Coconut Surveillance (Zanzibar), CommCare (Senegal) and DHIS2 (Zimbabwe, and South Africa). This shows that mobile-based apps give a larger footprint and a high level of agility to malaria response. Nevertheless, limited connectivity and erratic energy supplies have been key factors affecting the levels of adoption and some apps have been reported to have a high level of complexity. This has also been reported in other studies [ 41 , 42 ].

Moreover, it has been noted that most of these apps are independent with limited capability for interoperability. Hence there is a need to develop open standards for mobile technologies for malaria control. For example, surveillance applications should be able to have geolocation capabilities and use exiting open-source platforms like OpenStreetMap, OpenDataKit & OpenMapKit; work online and offline mode to enable usage in resource constraints areas, ease of use to enable usage with little or no training and should support different languages including local languages. This calls for more research and implementation of natural language processing frameworks for use in mobile apps in Africa, which can assist with data analytics as well. Furthermore, aligning app development with standards such as the Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) which facilitate interoperability between legacy health care systems and technology is important.

Superseding technological interoperability, there needs to be platform integration and overall visibility particularly on innovations that target malaria diagnosis, surveillance and management. However, it should be noted that systemically there has been launching of different applications for different malaria interventions which may confuse the public in terms of usage. Therefore, a single application or platform integrating several services such as Coconut Surveillance and owned and managed by a reputable malaria organization or the ministries of health may benefit citizens by allowing them to access services from a single and trusted application. Misinformation and misdiagnosis from publicly available medical apps is a health threat to the public as reported by [ 43 ].

Most of the reviewed web systems depend on data or are used to collect large amounts of malaria data to support decision-making. Hence a need for national malaria control and elimination information systems that can utilize regional and global structures, prioritizing cross-border intelligence sharing information regarding disease transmission hotspots, outbreaks, and human movement. Such systems can also be very useful in responding to pandemics like COVID-19 and other infectious outbreaks. There is also a need to have malaria related data centrally stored and managed by the Ministry of Health or malaria control programmes to guide decision-making at all levels of malaria response among the different stakeholders. Hospitals and clinics have also developed standalone patient information management systems in addition to the national health information management systems like OpenMRS and DHIS2. However, there is no communication between the different patient’s information management systems hence a need for development of open data standard driven systems and APIs to enforce interoperability among health systems in Africa. An effective information system must receive data from other sources, process it and send it back to other systems being used in malaria programme, particularly at the community level.

In malaria control, larval source management is very difficult to archive in rural areas due to perceived difficulties in identifying target areas [ 44 ]. Drones can capture extremely detailed images of the landscape, opening the possibility of replacing the time-consuming hunt for mosquito larvae on the ground with identifying habitat through aerial imagery. The review has shown that this has been used in several countries for example in Malawi and near Lake Victoria using DJI Phantom; low-cost drones that survey wilderness to find mosquito breeding grounds using Geospatial technology. Geospatial technology is rapidly evolving and now can be archived using remotely sensed data [ 45 ]. In Zanzibar, drones have been used to spray rice fields with a thin, non-toxic film as a strategy to eliminate mosquitoes. The review has shown that drones are a possible solution in malaria control programmes as also indicated in other studies [ 45 , 46 ]. The review also showed that rapid diagnostics tools offer fast turnaround services while circumventing obstacles faced when using microscopy in peripheral health care settings, including cost of equipment, reagents, and the need for electricity and skilled personnel [ 47 ].

This study has reviewed key emerging technologies used in malaria control programmes. The review revealed various technological applications that have been developed in response to malaria including surveillance, microplanning, prevention, diagnosis and management. Although breakthrough innovative platforms have been made available, one key challenge remained, which is lack of integration of key end-to-end components and functionalities to facilitate effective and efficient malaria response and to reduce fragmentation.

The review has also revealed several stakeholders in malaria control hence a need for mechanisms that promote the exchange of evidence between scientific, policy, and programme management communities for analysing the potential outcomes of the different malaria control strategies and interventions. In many malaria-endemic areas in Africa, the communication gap between policy makers, health workers, and patients is a significant barrier to efficient malaria control.

Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) has been widely used in the reviewed technological innovations, however there is an urgent need to provide reliable datasets, develop local AI expertise among WHO African member states, implement data protection and privacy acts; and put in place health innovation clusters to bring the different stakeholders together to develop and adopt appropriate technologies to solve the intended challenges.

Limitations of this work and future prospects

The main limitation of this work was that some applications were overlapping among the response areas and hence the decision to place an innovation under a given category was based on the judgement of the authors. Another limitation is the fact that this work is not aimed at analysing the total landscape of all malaria innovations. Only those that met the inclusion criteria and deemed relevant by the authors were included hence some innovations might not have been captured but we will be subjected to continuous update on the global database for malaria innovations at https://innov.afro.who.int/emerging-technological-innovations/7-malaria-innovations . Future research can focus on reviewing the technologies that are open source dedicated to malaria, and publishing findings that can be used by medical practitioners, application developers, and governments to collaborate in the process of containing the spread of malaria.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this report is available to readers.

Ryan SJ, Lippi CA, Zermoglio F. Shifting transmission risk for malaria in Africa with climate change: a framework for planning and intervention. Malar J. 2020;19:170.

Article Google Scholar

WHO. World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

Google Scholar

Garner P, Gelband H, Graves P, Jones K, Maclehose H, Olliaro P, et al. Systematic reviews in malaria: global policies need global reviews. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2009;23:387–404.

White MT, Conteh L, Cibulskis R, Ghani AC. Costs and cost-effectiveness of malaria control interventions—a systematic review. Malar J. 2011;10:337.

Conteh L, Shuford K, Agboraw E, Kont M, Kolaczinski J, Patouillard E. Costs and cost-effectiveness of malaria control interventions: a systematic literature review. Value Health. 2021;24:1213–22.

Adeola AM, Botai JO, Olwoch JM, Rautenbach AC, Kalumba AM, Tsela PL, et al. Application of geographical information system and remote sensing in malaria research and control in South Africa: a review. South Afr J Infect Dis. 2015;30:114–21.

Smith NR, Trauer JM, Gambhir M, Richards JS, Maude RJ, Keith JM, et al. Agent-based models of malaria transmission: a systematic review. Malar J. 2018;17:299.

Vasiman A, Stothard JR, Bogoch II. Mobile phone devices and handheld microscopes as diagnostic platforms for malaria and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in low-resource settings: a systematic review, historical perspective and future outlook. Adv Parasitol. 2019;103:151–73.

Mbanefo A, Kumar N. Evaluation of malaria diagnostic methods as a key for successful control and elimination programs. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5:E102.

Osei E, Kuupiel D, Vezi PN, Mashamba-Thompson TP. Mapping evidence of mobile health technologies for disease diagnosis and treatment support by health workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021;21:11.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26:91–108.

Kurland KS, Gorr WL. GIS tutorial for health. ESRI, Inc.; 2007.

Nakakana UN, Mohammed IA, Onankpa BO, Jega RM, Jiya NM. A validation of the malaria Atlas project maps and development of a new map of malaria transmission in Sokoto, Nigeria: a cross-sectional study using geographic information systems. Malar J. 2020;19:149.

Pfeffer DA, Lucas TCD, May D, Harris J, Rozier J, Twohig KA, et al. Malaria Atlas: an R interface to global malariometric data hosted by the malaria Atlas project. Malar J. 2018;17:352.

Kelly GC, Hale E, Donald W, Batarii W, Bugoro H, Nausien J, et al. A high-resolution geospatial surveillance-response system for malaria elimination in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu. Malar J. 2013;12:108.

Kim JY, Eun SJ, Park DK. Malaria vulnerability map mobile system development using GIS-based decision-making technique. Mob Inf Syst. 2018;12:1–9.

Brown Z, Kramer R, Mutero C, Kim D, Miranda ML, Amenshewa B, et al. Stakeholder development of the malaria decision analysis support tool (MDAST). Malar J. 2012;11(Suppl 1):P15.

Khandekar E. Performance evaluation of zanzibar’s malaria case notification (MCN) surveillance system: the assessment of timeliness and stakeholder interaction. Thesis, MSc Duke Global Health Institute, 2015.

Murray CK, Mody RM, Dooley DP, Hospenthal DR, Horvath LL, Moran KA, et al. The remote diagnosis of malaria using telemedicine or e-mailed images. Mil Med. 2006;171:1167–71.

Madoff LC, Freedman DO. Detection of infectious diseases using unofficial sources infectious diseases. In: Petersen E, Chen LH, Schlagenhauf P, editors. A geographic guide. Hoboken: Wiley Online; 2011.

Woodall JP. Global surveillance of emerging diseases: the ProMED-mail perspective. Cad Saúde Pública. 2001;17:147–54.

Merkord CL, Liu Y, Mihretie A, Gebrehiwot T, Awoke W, Bayabil E, et al. Integrating malaria surveillance with climate data for outbreak detection and forecasting: the EPIDEMIA system. Malar J. 2017;16:89.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sanches P, Brown B. Data bites man: the production of malaria by technology. Proc ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2018;2:153.

Barrington J, Wereko-Brobby O, Ward P, Mwafongo W, Kungulwe S. SMS for life: a pilot project to improve anti-malarial drug supply management in rural Tanzania using standard technology. Malar J. 2010;9:298.

Rajvanshi H, Jain Y, Kaintura N, Soni C, Chandramohan R, Srinivasan R, et al. A comprehensive mobile application tool for disease surveillance, workforce management and supply chain management for malaria elimination demonstration project. Malar J. 2021;20:91.

Oo Win Han, Htike Win, Cutts JC, Win KM, Thu KM, Oo MC, et al. A mobile phone application for malaria case-based reporting to advance malaria surveillance in Myanmar: a mixed methods evaluation. Malar J. 2021;20:167.

Yu H, Yang F, Rajaraman S, et al. Malaria screener: a smartphone application for automated malaria screening. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:825.

Oliveira AD, Prats C, Espasa M, Serrat FZ, Sales CM, Silgado A, et al. The malaria system microapp: a new, mobile device-based tool for malaria diagnosis. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6: e70.

Svoronos T. CommCare: automated quality improvement to strengthen community-based health the need for quality improvement for CHWs. Weston: D-Tree Int Publisher; 2010.

James S, Collins FH, Welkhoff PA, Emerson C, Godfray HC, Gottlieb M, et al. Pathway to deployment of gene drive mosquitoes as a potential biocontrol tool for elimination of malaria in sub-Saharan Africa: recommendations of a scientific working group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(Suppl 6):1–49.

Choi L, Majambere S, Wilson AL. Larviciding to prevent malaria transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012736.pub2 .

Thompson DR, de la Torre JM, Barker CM, Holeman J, Lundeen S, Mulligan S, et al. Airborne imaging spectroscopy to monitor urban mosquito microhabitats. Remote Sens Environ. 2013;137:226–33.

Stanford Graduate School of Business. Zipline : Lifesaving deliveries by drone. Stanford Business. 2019. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/case-studies/zipline-lifesaving-deliveries-drone .

Pare Toe L, Barry N, Ky AD, Kekele S, Meda W, Bayala K, et al. Small-scale release of non-gene drive mosquitoes in Burkina Faso: from engagement implementation to assessment, a learning journey. Malar J. 2021;20:395.

Hiscox A, Maire N, Kiche I, Silkey M, Homan T, Oria P, et al. The SolarMal project: innovative mosquito trapping technology for malaria control. Malar J. 2012;11(Suppl 1):O45.

Teshome EM, Oriaro VS, Andango PEA, Prentice AM, Verhoef H. Adherence to home fortification with micronutrient powders in Kenyan pre-school children: self-reporting and sachet counts compared to an electronic monitoring device. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:205.

Jelinek T, Grobusch MP, Nothdurft HD. Use of dipstick tests for the rapid diagnosis of malaria in nonimmune travelers. J Travel Med. 2000;7:175–9.

Tagbor H, Bruce J, Browne E, Greenwood B, Chandramohan D. Performance of the OptiMAL ® dipstick in the diagnosis of malaria infection in pregnancy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:631–6.

Visser T, Ramachandra S, Pothin E, Jacobs J, Cunningham J, Le Menach A, et al. A comparative evaluation of mobile medical APPS (MMAS) for reading and interpreting malaria rapid diagnostic tests. Malar J. 2021;20:39.

GSMA. Mobile Internet Connectivity 2019 Sub-Saharan Africa Factsheet. 2019. https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Mobile-Internet-Connectivity-SSA-Factsheet.pdf .

Murugesan S. Mobile apps in Africa. IT Prof. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1109/MITP.2013.83 .

Shead DC, Chetty S. Smartphone and app usage amongst South African anaesthetic service providers. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2021;27:76–82.

Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D. Public health and online misinformation: challenges and recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;41:433–51.

Stanton MC, Kalonde P, Zembere K, Spaans RH, Jones CM. The application of drones for mosquito larval habitat identification in rural environments: a practical approach for malaria control? Malar J. 2021;20:244.

Kullmann K. The drone’s eye: applications and implications for landscape architecture. Landscape Res. 2018;43:7.

Liardon JL, Hostettler L, Zulliger L, Kangur K, Shaik NS, Barry DA. Lake imaging and monitoring aerial drone. HardwareX. 2018;3:146–59.

Boyce MR, O’Meara WP. Use of malaria RDTs in various health contexts across sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:470.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Author information, authors and affiliations.

World Health Organization Africa Region, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo

Moredreck Chibi, William Wasswa & Chipo Ngongoni

Tropical and Vector Borne Diseases, Universal Health Coverage/Communicable and Non Communicable Disease Cluster, World Health Organization Africa Region, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo

Ebenezer Baba & Akpaka Kalu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MC lead the conceptualization and designing of the study, and writing of the manuscript. WW contributed with data mining, analytics and writing the manuscript. CN contributed with systematized literature review and reviewing the manuscript. EB contributed to conceptualizing the study and reviewing of the draft manuscript. AK contributed to reviewing the draft manuscript and providing expert oversight. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Moredreck Chibi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The author reports no conflicts of interest for this work and given their consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declared no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Chibi, M., Wasswa, W., Ngongoni, C. et al. Leveraging innovation technologies to respond to malaria: a systematized literature review of emerging technologies. Malar J 22 , 40 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04454-0

Download citation

Received : 23 January 2022

Accepted : 14 January 2023

Published : 03 February 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04454-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Emerging technologies

Malaria Journal

ISSN: 1475-2875

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 04 June 2024

What are medical students taught about persistent physical symptoms? A scoping review of the literature

- Catie Nagel 1 ,

- Chloe Queenan 1 &

- Chris Burton 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 618 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

133 Accesses

Metrics details

Persistent Physical Symptoms (PPS) include symptoms such as chronic pain, and syndromes such as chronic fatigue. They are common, but are often inadequately managed, causing distress and higher costs for health care systems. A lack of teaching about PPS has been recognised as a contributing factor to poor management.

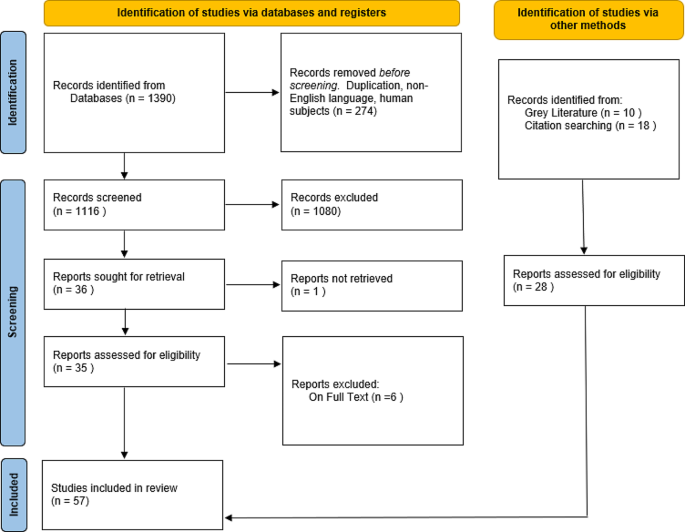

The authors conducted a scoping review of the literature, including all studies published before 31 March 2023. Systematic methods were used to determine what teaching on PPS was taking place for medical undergraduates. Studies were restricted to publications in English and needed to include undergraduate medical students. Teaching about cancer pain was excluded. After descriptive data was extracted, a narrative synthesis was undertaken to analyse qualitative findings.

A total of 1116 studies were found, after exclusion, from 3 databases. A further 28 studies were found by searching the grey literature and by citation analysis. After screening for relevance, a total of 57 studies were included in the review. The most commonly taught condition was chronic non-cancer pain, but overall, there was a widespread lack of teaching and learning on PPS. Several factors contributed to this lack including: educators and learners viewing the topic as awkward, learners feeling that there was no science behind the symptoms, and the topic being overlooked in the taught curriculum. The gap between the taught curriculum and learners’ experiences in practice was addressed through informal sources and this risked stigmatising attitudes towards sufferers of PPS.