- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

MedWatch: The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program

MedWatch , the FDA’s medical product safety reporting program for health professionals, patients and consumers.

MedWatch receives reports from the public and when appropriate, publishes safety alerts for FDA-regulated products such as:

- Prescription and over-the-counter medicines

- Biologics such as blood components, blood/plasma derivatives and gene therapies.

- Medical devices such as hearing aids, breast pumps, and pacemakers.

- Combination products such as pre-filled drug syringe, metered-dose inhalers and nasal spray.

- Special nutritional products such as medical foods and infant formulas.

- Cosmetics such as moisturizers, makeup, shampoos, hair dyes and tattoos.

- Food such as beverages and ingredients added to foods.

Other products that the FDA regulates include tobacco products , vaccines , and animal drug, device, pet food and livestock feed . These products use different reporting pathways and it is recommended that reports concerning these products be submitted directly to the appropriate portals.

MedWatch - The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program

Your FDA gateway for clinically important safety information and reporting serious problems with human medical products.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Increasing adverse drug reaction reporting—How can we do better?

Contributed equally to this work with: Miri Potlog Shchory

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel, Assaf Harofeh School of Nursing, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology

Affiliation Clinical Pharmacology Unit, Haemek Medical Center, Afula affiliated to The Bruce Rapapport School of Medicine, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Affiliation Clinical Pharmacology Unit, Kaplan Medical Center, Hebrew University and Hadassah Medical School, Rehovot, Jerusalem, Israel

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Affiliation Clinical Pharmacology Unit, Shamir Medical Center (Assaf Harofeh), Zerifin, Affiliated to Sackler School of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, Israel

- Miri Potlog Shchory,

- Lee H. Goldstein,

- Lidia Arcavi,

- Renata Shihmanter,

- Matitiahu Berkovitch,

- Amalia Levy

- Published: August 13, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are associated with morbidity and mortality worldwide. Although national systems for reporting ADRs exist there is a low reporting rate. The aim of the current study was to evaluate an intervention plan for improving ADRs reporting among medical professionals (physicians and nurses). A multicentre intervention study was conducted, in which one medical centre was randomly assigned to the intervention group and two medical centres to the control group. The study consisted of 3 phases: baseline data collection, intervention and follow-up of the reporting rate. The questionnaire that was filled in at base line and at the end of study, contained questions about personal/professional demographic variables, and statements regarding knowledge of and behaviour toward ADRs reporting. The intervention program consisted of posters, lectures, distant electronic learning and reminders. An increase in the number of ADRs reports was noted in the intervention group (74 times higher than in the control group) during the intervention period, which was gradually decreased with as the study progressed (adjusted O.R = 74.1, 95% CI = 21.11–260.1, p<0.001). The changes in the "knowledge related to behaviour” (p = 0.01) and in the "behaviour related to reporting" (p<0.001) score was significantly higher in the intervention group. Specialist physicians and nurses (p<0.001), fulfilling additional positions (p<0.001) and those working in other places (p = 0.05) demonstrated a high rate of report. Lectures were preferable as a method to encourage ADRs reporting. The most convenient reporting tools were telephone and online reporting. Thus, implementation and maintenance of a continuous intervention program, by a pharmacovigilance specialist staff member, will improve ADRs reporting rates.

Citation: Potlog Shchory M, Goldstein LH, Arcavi L, Shihmanter R, Berkovitch M, Levy A (2020) Increasing adverse drug reaction reporting—How can we do better? PLoS ONE 15(8): e0235591. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591

Editor: Karen Cohen, University of Cape Town, SOUTH AFRICA

Received: September 1, 2019; Accepted: June 19, 2020; Published: August 13, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Potlog Shchory et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data files are available from the ICPSR database - project ID-openicpsr-119582.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

An integral part of drug therapy is the adverse reactions associated with the drug [ 1 ]. These reactions can cause personal injury, hospitalization overload and increase in health costs, thereby creating a heavy burden on national healthcare systems [ 2 – 5 ]. Studies around the world have demonstrated that 3–7% of all hospitalizations are a result of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and 10–20% of inpatients suffer from drug-related adverse reactions [ 3 , 6 – 8 ]. Serious ADRs were found to be the fourth to sixth causes of death in hospitalized patients in the US, leading to extended hospitalization and doubling of the cost of treating these patients [ 9 , 10 ]. Therefore, both healthcare teams and patients share a common goal of early detection and prevention of ADRs.

Pharmacovigilance is defined by the WHO as the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse reactions or any other drug-related problem. National systems for reporting drugs' adverse reactions can be found in almost every country [ 10 – 12 ]. Spontaneous reporting of medical staff regarding the occurrence of adverse reactions is the major source for monitoring and investigating adverse reactions of marketed drugs. However, only 1 in 20 adverse reactions is actually detected and defined as a real side effect; this leads to the erroneous assumption that the incidence of adverse reactions is much lower than it actually is [ 13 – 15 ]. Inadequate ADR reporting may lead to loss of clinical information that could prevent substantial damage to patients and consequently minimize health costs.

Hence, it is very important to encourage medical staff to report any definite or suspected ADR, as well as to establish and maintain an accurate database which can be used for analyzing and processing of accumulated data, drawing conclusions and providing further recommendations. This series of actions could optimize patients’ wellbeing and safety and improve the functioning of the healthcare system.

Israel has been an official member of the World Health Organization international program for monitoring drugs since 1973. In August 2012, the Israeli ministry of health (MOH) published guidelines for reporting adverse events and new safety information. This document specifies the type of information that the Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) requires reporting and enables the MAH to appoint a pharmacist to serve as a qualified person responsible for matters related to the reports included in this standard operating procedure, according to the standard worldwide practice. Those regulations were update at February 2013 in order to clarify the work processes related to reporting ADRs and new safety information, to update the definitions of the SOP and to update the types of information requiring reporting by the MAH. The aim of additional update from May, 2013 was to adjust the SOP to the Pharmacists Regulations [ 16 ]. A new regulation was launched at October, 2014, in which a reporting system in medical institutions for both common and severe ADRs was established. In July 2019, a new portal for reporting adverse events to the Risk Management Department was established. The purpose of all these regulations was to raise the awareness of the healthcare teams to the importance of reporting ADRs [ 17 ]. Nevertheless, the reporting rate in Israel, as is worldwide, is still quite low. Schwartzberg el al., identified 16,409 of Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs) submitted to the MOH’s ADRs central database between September 2014 and August 2016. However, of these reports, only 5.5% were submitted by health care professionals from medical institutions, while 94.3% were submitted by pharmaceutical companies (MAH and importers) and only 0.2% of the reports have been submitted by patients and the general public [ 18 ].

The purpose of the present study was to establish and evaluate an intervention plan in order to improve the reporting norms of ADRs among medical professionals (physicians and nurses).

Materials and methods

Study design.

The study was conducted over a period of 17 months (August 2012 to December 2013) and included the healthcare teams (physicians and nurses) of internal medicine divisions from three public medical centers in Israel: "A", "B" and "C", while each division served as a cluster. The medical centers selected for the study were public hospitals serving an urban and rural population of 0.5–1 million people each. In Israel, a high percentage of physicians and nurses are from the Commonwealth States and Russian is their first language. In order to make it easier for them to complete the questionnaire and to increase the response rate it was translated into Russian. Staff members who lacked sufficient knowledge of Hebrew or Russian to fill in the questionnaires were excluded from the study. Medical Center "A" was randomly selected to be the intervention group. Medical centers "B" and "C" were merged and served as the control group. The randomization among the centers was raffled by an external person who was not related to the study. ADRs reports were collected from the Israeli Ministry of Health computerized website for all three medical centers, and reports from medical center "A" (the intervention group) were also collected from the physical reporting binders available in the departments. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each medical center respectively. "A"—Ethics ("Helsinki") Committee; (protocol Number 180/10); "B"—Committee Helsinki; (protocol Number EMC-0107-10); "C"—Ethics ("Helsinki") Committee (protocol Number ver:1 KAP 1). In the introduction to the questionnaire a detailed explanation regarding the research and its rational was provided (See Supplement 1 in the S1 File ). In this section the participant was required to give consent to be included in the research. Verbal consent was received during a meeting in which the research was presented to each participant. As part of the consent procedure the interviewer explained to each medical staff member (physicians and nurses) about the study. Potential participants were informed that taking part in the study was voluntary. Those who agreed to participate gave their oral consent. A record of all participants who provided oral consent was kept by the principal investigator. Every local IRB approved the use of verbal consent. Written consent was not obtained from the participants because the participants were staff members and not patients.

The study consisted of 3 phases: The first phase of baseline data collection lasted three months and included handing out a questionnaire to the healthcare teams. The questionnaire contained questions about personal and professional demographic data, and statements regarding the knowledge of and behavior toward ADRs reporting.

The second phase of the study was a 5-month intervention phase. The purpose of the intervention plan was to improve the staff reporting rate of ADRs. Site "A" was randomly selected as the medical center for intervention. The intervention program consisted of the following: a) posters for raising the awareness of the medical staff; these were placed at various locations throughout the departments, such as: physicians’/ nurses’ rooms, medication rooms, and dining areas; b) Forty-five minute lectures that were given during divisional meetings of physicians and nurses separately. The lectures included: definitions of ADRs and pharmacovigilance, an explanation about the importance of the issue, data from international studies in the field, information about the relationship between adverse drug events and morbidity/mortality rates, incidence and prevalence of ADRs during hospital admission, the costs of ADRs for the healthcare system and the patients, presenting the reasons of ADR under reporting and a description of the current practices in Israel and around the world; c) Program promotion. This included: visiting the departments and talking with the medical staff twice weekly, presenting the program in the medical center portal and homepage and sending text messages to the participants on their mobile phones every two weeks (a total of 8 text messages were sent); d) introduction of distant electronic learning into the medical center portal.

The third phase of the study lasted 9 months and included following up on the monthly reporting rates. ADRs were reported through the Ministry of Health computerized website (for both the intervention and the control group) or documented in binders available only in the departments of the intervention group. At the end of this phase the participants from both groups were asked to fill in the same questionnaire again.

The questionnaire (Supplement 1 in S1 File )

The questionnaire design was based on the causes for underreporting of ADRs among professionals, known as the “seven deadly sins” and on the combined theoretical model of the factors affecting the conditions for ADR reporting by healthcare professionals [ 17 , 19 – 32 ].

Demographic data included profession and degree, date and place of birth, gender, country of professional training, years of experience, expertise, as well as additional roles and positions in other medical institutions.

"Knowledge related to behavior" was intended to explore the knowledge of the participants about the ADR reporting procedure and its importance. It was investigated using the following general question which dealt with identification of ADRs and the reasons for reporting/not reporting: "You may notice an irregular adverse reaction from drug treatment and not report it since:" Then the participants were prompted to choose one of 5 statements: "A. I know the adverse drug reaction has already been documented by the pharmaceutical company"; "B. I do not know that there is a center for reporting adverse drug reactions"; "C. I am not aware of the need for reporting adverse drug reactions"; "D. I don't know how to report adverse drug reactions"; and "E. Reporting one adverse drug reaction does not significantly contribute to the reporting mechanism". The answers were ranged on a scale from 1 point—no reason for not reporting to 10 points—good reason for not reporting. This means that a staff member who reports ADRs will receive a lower score.

The score of "behavior related to reporting" was constructed from two items that analyzed the patterns of reporting to the National Center of pharmacovigilance and to pharmaceutical companies. The statements were: "A. I spoke with pharmaceutical companies about the possibility of adverse drug reactions with their drugs"; and "B. Have you ever reported adverse drug reactions to a national reporting center?". The average of this score ranged from 1 point—non reporting behavior—through 10 points—reporting behavior. The higher rate of reporting achieved a higher score.

The main hypothesis: after the intervention program there would be more ADRs reporting among medical professionals (physicians and nurses) in the intervention group compared to the control group and to ADRs reporting base line.

Data analysis

Data analysis was carried out using the SPSS 21 software (PASW inc., USA). The statistical analysis was conducted according to the phases of the study. Means and standard deviation were used for continuous variables and examined by T or One-Way ANOVA/Mann Whitney tests based on the variables distribution. The score of "Knowledge related to behavior" and the score of "behavior related to reporting" didn’t distribute normally, thus we used a- parametric test (Mann Whitney). Percentages and numbers were used for categorical variables and were tested by chi square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. Statistical significance was established as p≤0.05. The multi-variable models examined the independent effect of the intervention program on reporting. The difference (change) was viewed as the dependent variable, and factors forecasting change were examined through multi-variable linear regression models. Identifying independent predicting factors of reporting adverse reactions was done through multi-variable logistic regression models.

Quantitative variables, such as the differences between groups, comparison between physicians and nurses and between medical centers, were analyzed by chi square or Fisher’s exact tests. The differences and changes between the various parameters (knowledge and reporting patterns) were calculated by comparing the data collected after the intervention phase with the baseline data (change). The differences in knowledge and reporting among the study groups were compared separately by T tests with independent samples or through One-Way ANOVA. The building strategy for multivariable models was forced all the independent variables to one block. Both statistical and clinical justifications were considered. The models included all the variables that were found to be significant (p<0.05) in the univariate data analysis, and covariates that were important to controlling for, as a baseline characteristic, according to the research questions. All the independent variables that were included in the analyses were presented in the results of the multivariable models. The multivariate models examined the effect of the intervention program on knowledge and reporting. The difference (change) was defined as the dependent variable and factors forecasting change were examined through linear regression. The adjusted factors of reporting adverse reactions (with 95% confidence intervals, 95% CI) were performed through multivariate logistic regression models. The independent effect of every measure index of the questionnaire was adjusted to demographic and professional variables.

433 (81.5%) medical staff members, physicians and nurses, completed the questionnaire twice, before and after the intervention. 47.8% of the participants were from the "A" medical center, 28.4% from "B" and 23.8% from "C". Distribution by gender was 69.1% females and 30.9% males. 73% were nurses and 27% physicians. No selection bias was found between the staff members completed the questionnaire the first time and those completed it twice. No differences in personal or professional variables were found between the intervention group ("A" medical center) and control group ("B" and "C" medical centers), except for the ratio between physicians and nurses and the subjects country of origin and average age."

During the research period, 336 ADRs were reported, of which 288 (85.7%) were reported in Medical Center “A”, with 285 ADRs from the reporting binders and 3 ADRs from the Ministry of Health’s computerized website. The ADRs reports from the control groups comprised 10 reports (3%) in center “B” and 38 reports (11.3%) in center C; these were reported to the Health Ministry’s computerized website. The reports were checked and there were no duplicate reports by the staff members on both reporting channels in the intervention group.

The number of ADRs reports in the intervention vs. the control groups during the study period is presented in Fig 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

A rapid and substantial increase in the number of ADR reports was noted in the intervention group during the 5-month intervention period, which gradually decreased toward the end of the study.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.g001

A rapid and substantial increase in the number of ADR reports was noted in the intervention group during the 5-month intervention period, which gradually decreased toward the end of the study. The reporting in the intervention group went nearly back to baseline and was even lower than in the control group. On the other hand, there was almost no change in the number of ADR reports in the control group during the entire study duration. After the intervention period the reporting rate in the intervention group reverted to almost baseline and was lower than the control group, similarly to the trend that was observed in the baseline.

Comparison of the rate of ADRs reports received from physicians vs. nurses indicated that in both groups a substantial increase in the number of ADR reports was observed during the intervention period, which gradually decreased toward the end of the study.

Comparison of the score of "knowledge related to behavior" showed that before any intervention the mean score of the control group was significantly lower than that observed in the intervention group (3.84±2.20 and 4.37±2.27 respectively, p = 0.02), demonstrating that the control group was more aware of ADRs reporting. Nevertheless, the changes in the "knowledge related to behavior” score was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group (a change of -0.69±2.58 in the intervention group vs. -0.11±2.19 in the control group, P = 0.01)) Table 1 ).

The changes in the "knowledge related to behavior” score was significantly higher in the intervention than in the control group.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t001

When the score of "behavior related to reporting" was compared between the intervention and control groups upon intervention, a statistically significant increase in the score "behavior related to reporting" was observed in the intervention group, with a mean change of 0.65±2.22 (2.21±1.88 before intervention and 2.37±2.87 after intervention, P<0.001). No significant difference in the score of "behavior related to reporting" was noted in the control group ( Table 2 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t002

Comparison of patterns in "behavior related to reporting" was conducted according to various demographic and professional-related variables. The results revealed that the nurses demonstrated less changes in "behavior related to reporting" than physicians (P = 0.003). A significant positive correlation was found between the numbers of patients treated per day by the medical staff (nurses and physicians) and "behavior related to reporting", i.e. as the number of patients per caregiver increased, the change in "behavior related to reporting" score was higher (P = 0.02). In addition, the results revealed that the more aware the caregiver is of the fact that the patients are consuming more than one medication per day, a larger change in "behavior related to reporting" score is observed (P = 0.02, r = 0.13) ( Table 3 ).

Nurses demonstrated less changes in "behavior related to reporting" than physicians A significant positive correlation was found between the numbers of patients treated per day by the medical staff (nurses and physicians) and "behavior related to reporting", as well as between the awareness of the caregiver that the patients are consuming more than one medication per day, and the change in "behavior related to reporting" score.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t003

The demographic and the professional variables and reporting/non reporting behavior were later examined within the intervention group. As seen in Table 4 , physicians reported more than nurses (56.9% vs. 36.5%, p = 0.009). Specialists, both nurses and physicians, reported more than non-specialists (60.6% vs. 32.6%, p<0.001). Those (both physicians and nurses) fulfilling additional positions and those working in other places beside the hospital demonstrated high rates of reports (66.7% vs. 33.6%, p<0.001 and 60.0% vs. 39.8%, p = 0.05, respectively) ( Table 4 ).

Physicians reported more than nurses; specialists, reported more than non-specialists; those fulfilling additional positions and those working in other places beside the hospital demonstrated high rates of reports.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t004

Further analysis of the previous data to physicians and nurses revealed that the demographic and professional variables among the physicians did not have any effect on the percentage of ADRs reports. However, among the nurses, specialty (56.1% vs 29.6%, p = 0.02) and fulfilling additional positions (63.3% vs. 28.8%, p<0.0001) indeed increased reporting rates, while no difference was observed with regard to working in other places besides the hospital (37.5% vs. 36.6%, p = 0.96).

The intervention plan had a strong, independent and statistically significant effect on "behavior related to reporting" (p = 0.008). In addition, profession and number of patients treated per day by the caregiver also had a significant effect on the "behavior related to reporting" (p = 0.01 and p = 0.02, respectively) ( Table 5 ).

The intervention plan had a strong, independent and statistically significant effect on "behavior related to reporting". Profession and number of patients treated per day by the caregiver also had a significant effect on the "behavior related to reporting".

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t005

In order to examine the independent effect of the intervention plan on reporting (yes / no), a logistic model was constructed. We found that the intervention plan had a strong, independent, statistically significant effect on the staffs’ actual ADRs reporting. After standardization for specialist, expertise, holding managerial positions and those who work in other places, subjects in the intervention group reported 74 times higher than their counterparts in the control group (O.R = 74.1, 95% CI = 21.11–260.1, p<0.001) ( Table 6 ).

A logistic model revealed that the intervention plan had a strong, independent, statistically significant effect on the staffs’ actual ADRs reporting.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.t006

Education and lectures were preferable, while payment for reporting was the least desirable method for encouraging medical staff to report side effects. The most convenient reporting tools were found to be the telephone and an internet site.

The purpose of this study was to establish and evaluate an intervention plan for increasing ADR reporting rate among physicians and nurses. This study demonstrates that the rate of ADR reporting increased significantly during the intervention period, and declined gradually thereafter. However, almost no change in the numbers of reports was observed in the control group during the entire duration of the study. The trend presented in the data that the rate of reports decreased over time after the intervention program was discontinued implies that continued intervention may be required to maintain the high rate of reports. Interestingly, the reporting rate in the control group was higher than in the intervention group at base line, though it was not statistically significant. The intervention plan increased the reporting rate and the differences between the control and the intervention rose and were statistically significant throughout the intervention period. However, as distance from the intervention period increased, the amount of reports decreased eventually reverting to the trend that was observed at the baseline. The impact of the intervention waned with time. An example to this trend was demonstrated also in an educational intervention program to improve physicians' reporting of ADRs. In this study the reporting rate in the intervention group increased during the intervention, while it gradually decreased through 13 months of follow-up [ 9 ].

The compliance rate of the participants in the present study for filling in both questionnaires was rather high (81.5%). A lower rate of compliance was reported in similar studies, in which 22.8% (Biagi 2013) or 47% (Passier 2009) of the physicians answered questionnaires regarding ADRs reporting [ 33 , 34 ]. Another study from Venezuela (Garciani 2011) reported higher compliance rate of 65.4% among physicians and pharmacists and 60% among nurses [ 35 ]. Interestingly, a much lower compliance rate was found in studies in which the questionnaires were sent to the participants by e-mail or regular mail [ 36 ]. The relatively high rate of compliance in the current study may be associated with the constant presence of the investigator at the medical centers and the personal contact with the study participants.

According to the results of the current study, physicians reported ADRs more than nurses. In addition, the change in the “Behavior related to reporting” score in the intervention group was higher among physicians compared to the nurses. The changes in the “Behavior related to reporting” is also demonstrated by the increase in the rate of ADRs in the intervention group compared the control group. This finding is consistent with other studies [ 1 , 37 – 39 ]. In a study that took place in Korea, spontaneous reports of ADRs by e-mail were 13% among nurses vs. 53% reports by physicians. Some studies demonstrated that nurses mostly tend to report an ADR to a physician. Hanafi et al. have shown that 89% of the nurses who participated in the study said that they reported the ADR to the physician [ 40 ]. The Hajebi’s study found that 56% of the nurses that come across a drug-related side effect reported to the department physician, 26% to the head nurse and 13% to a pharmacist [ 41 ]. The availability and accessibility of physicians to nurses who work in hospitals probably encouraged the reporting to physicians. This tendency could explain the difference in ADR reporting rates between nurses and physicians. Contrarily, in a research that was conducted in an Israeli public hospital where the medical staff was encouraged to report ADRs to the clinical pharmacology unit, the nurses were found to have reported more ADRs than the physicians [ 42 ]. In the present study, despite the fact that the nurses reported less than the physicians, their rate of reports peaked more quickly and decreased more slowly than that of the physicians.

We also found that professionals who fulfill additional positions in the department or in other health institutions (such as: community health services or treating senior citizens at nursing homes) demonstrated higher rates of ADR reporting. In addition, the results of the present study showed that specialists reported more ADRs than non-specialists and that the rate of ADR reporting was associated with the number of patients treated per day by the caregiver. A contrary observation was reported by a study in Ireland, which investigated the rate of ADR reporting among 118 hospital-based physicians. This study found a higher rate of ADR reporting among general physicians than among surgeons [ 43 ].

The present study demonstrated that the preferred method for increasing the rate of ADR reporting was lectures and education A study that compared telephone-interview intervention with a workshop intervention showed that the latter increased ADR reporting rate by a fourfold on average compared to the control group over 20 months post-intervention. However, no significant difference vs. the control group in ADR reporting was found in the telephone-interview intervention [ 44 ]. Other studies have shown that improved communication with fellow physicians and involvement of pharmacists might be the best ways to improve ADR reporting [ 21 , 34 ]. Regular newsletter on current awareness in drug safety, information on new ADRs, and international drug safety information were also identified as tools or methods that may motivate ADR reporting in a study conducted by Santosh et al. among 450 healthcare professionals working at Regional Pharmacovigilance Centers in Nepal [ 21 ].

Our research shows that the preferred means of reporting were telephone or website. Other studies also report these methods as preferential. A study of 500 nurses from a teaching hospital in Teheran showed that among the 10% who reported an ADR, the majority of the nurses preferred using the telephone [ 45 ]. Among physicians in India and the Netherlands, most of the ADRs were reported using the computerized system [ 34 , 46 ].

Payment for reporting was found to be the least favored method to encourage ADR reporting in the current study. A survey of 91 practice nurses, health visitors, school nurses and general physicians conducted by Pulford et al., has shown that payment for ADR reporting was indeed the least acceptable out of 14 other options of gratuity [ 47 ].

Conclusions

The results of this study indicate that training and educating medical practitioners and providing them with relevant knowledge regarding ADR reporting is essential. Due to the observation that the reporting rate decreased with time upon the finalization of the intervention period, it seems that maintaining a program to encourage reporting, is necessary. Regular implementation of such a program in the healthcare system will increase the awareness of the medical staff and improve reporting rates. Maintaining the intervention program could be carried out by nomination of a pharmacovigilance specialist trustee to administer a routine intervention program. This expert could be a physician, a nurse or a pharmacist. Visits, personal discussions, posters, lectures about the importance of ADRs reporting and how to carry it out and sending text messages to the medical staff on their mobile phones with reminders and relevant information should be used in order to continuously raise their awareness reporting about ADRs. In addition, the personal contact of the medical staff with the trustee will encourage their commitment to report about ADRs. This will probably improve monitoring of medication use, decrease morbidity/mortality rates and hospitalization duration.

Limitations

The study was carried out in internal divisions of only 3 public medical centers, and therefore may not have an external validation in other hospitals.

The study included only physicians and nurses, therefore the results cannot be applied to additional medical professionals.

There were some differences in the basic characteristics between the clusters (hospitals) which may have affected the quality of the intervention to a certain extent. However, after adjusting for the demographic variables, we can assume that the results of the study are indeed due to the effect of the intervention.

We cannot assume from this study that the effect of the intervention would improve safety of medicine use in the long term and reduce health costs.

Supporting information

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.s001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.s002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235591.s003

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 2. WHO, Geneva. Safety of Medicines: A guide to detecting and reporting adverse drug reactions. 2002; URL: http://www.who.int/medicuned/en/d/jh2992e/

- PubMed/NCBI

- 4. Atkinson AJ, Abernethy DR, Daniels CE, FASHP RP, Robert L. Dedrick RL, et al. Principles of Clinical pharmacology. second edition (2007) Chapter 25 Clinical analysis of adverse drug reaction 389–402.

- 16. https://www.health.gov.il/hozer/DR_6E.pdf

- 22. Inman WHW. Assessment of drug safety problems. In: Gent M, Shigmatsu I, editors. Epidemiological issues in reported drug-induced illnesses. Honolulu (ON): McMaster University Library Press, 1976:17–24.

- 23. Inman WHW, Weber JCT. The United Kingdom. In Inman WHW, editor. Monitoring for drug safety. 2nd ed. Lancaster: MTP Press Ltd, 1986: 13–47.

- 37. Guidelines for reporting side effects to medication by a registry (June 1998) Ministry of Health.

Factors Associated with Underreporting of Adverse Drug Reactions by Health Care Professionals: A Systematic Review Update

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 06 June 2023

- Volume 46 , pages 625–636, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Patricia García-Abeijon 1 ,

- Catarina Costa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8247-0422 2 ,

- Margarita Taracido ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1243-8352 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Maria Teresa Herdeiro ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0500-4049 5 ,

- Carla Torre ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5542-9993 2 , 6 &

- Adolfo Figueiras ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5766-8672 1 , 3 , 4

4363 Accesses

16 Citations

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Introduction

Underreporting is a major limitation of the voluntary reporting system of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). A 2009 systematic review showed the knowledge and attitudes of health professionals were strongly related with underreporting of ADRs.

Our aim was to update our previous systematic review to determine factors (sociodemographic, knowledge and attitudes) associated with the underreporting of ADRs by healthcare professionals.

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for studies published between 2007 and 2021 that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) published in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish; (2) involving health professionals; and (3) the goal was to evaluate factors associated with underreporting of ADRs through spontaneous reporting.

Overall, 65 papers were included. While health professional sociodemographic characteristics did not influence underreporting, knowledge and attitudes continue to show a significant effect: (1) ignorance (only serious ADRs need to be reported) in 86.2%; (2) lethargy (procrastination, lack of interest, and other excuses) in 84.6%; (3) complacency (the belief that only well tolerated drugs are allowed on the market) in 46.2%; (4) diffidence (fear of appearing ridiculous for reporting merely suspected ADRs) in 44.6%; and (5) insecurity (it is nearly impossible to determine whether or not a drug is responsible for a specific adverse reaction) in 33.8%, and the absence of feedback in 9.2%. In this review, the non-obligation to reporting and confidentiality emerge as new reasons for underreporting.

Conclusions

Attitudes regarding the reporting of adverse reactions continue to be the main determinants of underreporting. Even though these are potentially modifiable factors through educational interventions, minimal changes have been observed since 2009.

Clinical Trials Registration

PROSPERO registration number CRD42021227944.

Similar content being viewed by others

Factors associated with underreporting of adverse drug reactions by patients: a systematic review

Factors that motivate healthcare professionals to report adverse drug events: a systematic review.

Why hospital-based healthcare professionals do not report adverse drug reactions: a mixed methods study using the Theoretical Domains Framework

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are responsible for 10% of outpatient appointments [ 1 , 2 ] and 3.5–10% of hospital admissions [ 1 , 2 ], and are the fifth leading cause of death in hospitalized patients, in addition to prolonging stays and presenting a high economic impact [ 3 , 4 ]. The spontaneous reporting of suspected ADRs by health professionals allows continuous determination of the benefit–risk ratio of a given drug and is one of the best methods to generate signals regarding unexpected events and rare ADRs [ 1 , 5 ].

Underreporting is a major limitation of spontaneous notification systems, as it is estimated that only 6–10% of all ADRs are reported [ 6 , 7 ]. On the one hand, this high underreporting rate prevents ADRs from being quantified in order to calculate their impact in terms of incidence and risk [ 6 ], and on the other hand, it delays the activation of warning signals, with the consequent repercussions on public health [ 5 , 6 , 8 ]. These delays in decisions to restrict a drug’s use or to withdraw it may result in many more patients being affected [ 5 ].

In 2009, our group carried out a systematic review on factors associated with the underreporting of ADRs [ 8 ], which showed that a high proportion of studies found that the main factors related to underreporting are the knowledge and attitudes of health professionals. We believe that an update of this review may be of interest for several reasons: (1) numerous studies have been published since 2006; (2) we wanted to check whether these studies have identified new factors related to underreporting; and (3) in our 2009 review, methodological problems had been identified (many studies do not specify the type of design, or have a low percentage of participation and response) and we consider that it would be of interest to assess whether the methodological quality has improved. In the current manuscript, we update our previous review [ 8 ] on the factors (socioprofessional characteristics, knowledges, attitudes) associated with underreporting of ADRs by health professionals.

2 Methods and Data Extraction

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020, 27-item checklist guideline, and its research protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (registry number CRD42021227944).

2.1 Bibliographic Search Method

A bibliographic search of studies published between January 2007 and February 2021 was performed in the MEDLINE (Pubmed) and EMBASE scientific databases. The search terms used were (‘attitude*’ OR ‘knowledge*’ OR ‘barrier*’ OR ‘facilitators*’) AND (‘adverse drug reaction reporting systems’ [MeSH] OR ‘drug related side effects and adverse reactions’ [MeSH]) AND ‘report*’.

Studies were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) they were published in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish; (2) the study population was defined as healthcare professionals (doctors, pharmacists, nurses, administrators, residents, and other health professionals); (3) articles whose objective was to evaluate the factors associated with ADR underreporting; and (4) articles that address ADR reporting through spontaneous reporting.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) did not have an abstract and/or full text; (2) conference abstracts, thesis, comments, letters, abstracts, or editorials; (3) systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses; (4) articles on a specific pathology and/or treatment; (5) were carried out on patients and/or consumers; (6) did not focus on the study objective; (7) identified attitudes and knowledge but were not directly associated with the reasons for underreporting.

2.2 Quality Evaluation

An assessment of the quality and risk of bias of the articles was performed using the AXIS cross-sectional study assessment tool [ 9 ]. This tool contains 20 questions, 10 related to the methods, 5 related to the results,which indicates the importance of these sections in quality, 1 to the introduction, and 4 to the discussion (Table 1 ).

Of the 20 questions, 7 evaluated the quality of reporting (1, 4, 10, 11, 12, 16 and 18), 7 evaluated the quality of the study design (2, 3, 5, 8, 17, 19 and 20), and 6 evaluated the possible introduction of biases in the study (6, 7, 9, 13, 14 and 15) [ 9 ].

Two reviewers (CC and PGA) independently conducted the critical assessment for each included study. In the case of disagreement, a third reviewer (CT, MTH, or AF) was responsible for resolving discrepancies.

2.3 Data Extraction

All articles retrieved were independently screened by two reviewers (CC and PGA), who further independently conducted the full-text analysis to assess suitability for the inclusion of each potentially eligible study. In the case of any divergent decisions, a third reviewer (CT, MTH, or AF) acted as referee to reach consensus.

The data extracted from the articles were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and two tables were created. In the first table, the author (publication year), country, study population, workplace, sample size, survey distribution, survey scale and AXIS not fulfilled criteria were included (Online Resource Table S1).

The second table contained the author (publication year), response rate, personal and professional factors associated with ADR reporting, and reasons for not reporting the ADR (Online Resource Table S2). All the reasons cited have been extracted from the results of the studies and have been assigned to one of Inman’s ‘deadly sins’ [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. In 1976, Inman proposed a theoretical model to explain the reasons for ADR underreporting by health professionals. This model was called Inman’s ‘seven deadly sins’ and included complacency diffidence, indifference, ignorance, ambition, financial reimbursement, legal aspects, fear, and feedback. The model has been modified and expanded, including insecurity, unavailability of notification form, and lethargy [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]. These reasons can be grouped into attitudes related to the professional activity (legal fears, economic interests, and ambition to publish), ADR-related knowledge and attitudes (complacency, diffidence, indifference, ignorance, and insecurity), and related to excuses (lethargy) [ 8 ].

The median of respondents who stated that this attitude determines their ADR reporting was calculated for each of the attitudes (Online Resource Table S3).

2.4 Sensitivity Analysis

In order to assess the impact of the quality of the articles included in the results of the review, a sensitivity analysis was performed. This subanalysis included articles whose AXIS score was above the median of the total studies.

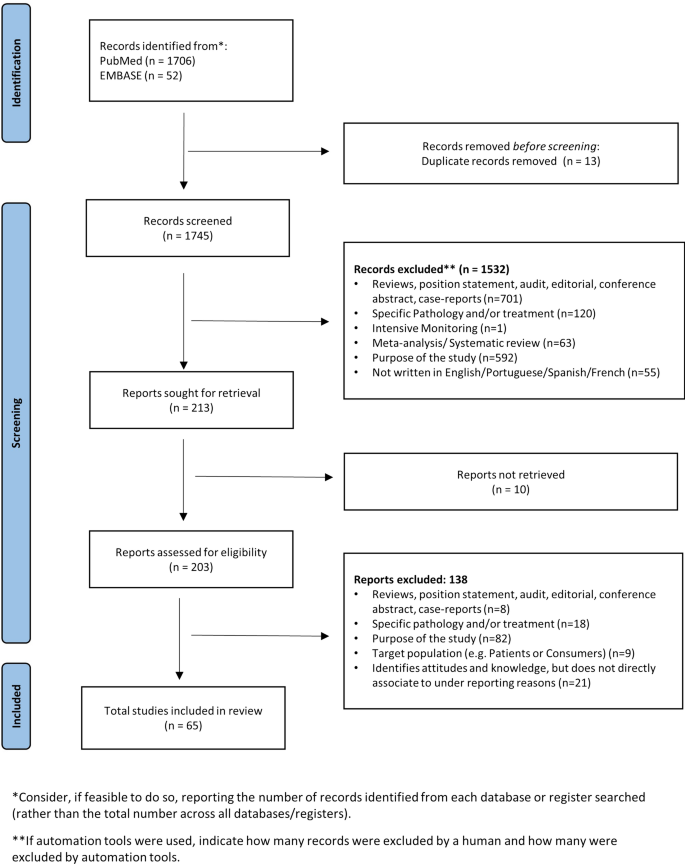

3.1 Article Selection

Using the chosen search strategy, 1758 articles were located—1706 in MEDLINE and 52 in EMBASE (see Fig. 1 ). After reading the abstracts, it was considered that 203 articles met the inclusion criteria, and a complete full-text analysis of these was carried out. After a full-text reading, 138 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and 65 articles were selected—57 from MEDLINE and 8 from EMBASE (Fig. 1 )

Study identification process

3.2 Characteristics of the Selected Articles

More than half of the articles (45/65, 69.2%) were cross-sectional studies [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 64 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 74 ], 21.5% did not indicate the design type used [ 20 , 25 , 52 , 57 , 58 , 62 , 63 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 72 , 73 , 75 , 76 ], 4.6% were case-control studies [ 40 , 46 , 77 ] (during the same period, the cases had reported ADR and the controls had not), 3.1% (2/65) were mixed studies [ 15 , 43 ] (only data from the quantitative part were used), and one (1.5%) was an intervention study [ 53 ] (pre-intervention data were extracted). Two studies were conducted before a pharmacovigilance system was in place [ 17 , 31 ].

According to geographical distribution, we located studies carried out in 36 countries: 38.5% were carried out in Asia [ 19 , 22 , 28 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 72 ], 27.7% in Africa [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 23 , 27 , 30 , 34 , 42 , 45 , 48 , 49 , 65 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 74 ], 24.6% in Europe [ 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 33 , 40 , 43 , 54 , 55 , 57 , 60 , 62 , 66 , 73 , 75 , 77 ], 7.7% in America [ 16 , 36 , 41 , 67 , 76 ], and one in Australia [ 27 ].

Regarding the setting where the study was performed, 43.1% took place in hospitals [ 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 24 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 53 , 56 , 59 , 63 , 64 , 66 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 73 , 74 ], 21.5% in pharmacies [ 20 , 21 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 38 , 39 , 51 , 61 , 65 , 72 , 75 , 76 , 77 ], 9.2% did not mention the place [ 16 , 25 , 52 , 55 , 57 , 62 ], 6.2% in hospitals and pharmacies [ 28 , 50 , 67 , 71 ], and 6.2% in primary care [ 13 , 23 , 27 , 29 ]. In 10 articles, the results of surveys carried out in two different health facilities are combined [ 28 , 34 , 36 , 37 , 40 , 49 , 50 , 54 , 67 , 71 ].

Regarding the study population, pharmacists were the most studied [ 20 , 21 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 33 , 39 , 46 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 61 , 65 , 67 , 68 , 72 , 75 , 76 , 77 ], followed by doctors, pharmacists and nurses together [ 13 , 14 , 19 , 22 , 27 , 30 , 36 , 41 , 44 , 45 , 49 , 56 , 64 ], and lastly, doctors [ 15 , 37 , 48 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 63 , 66 , 70 , 73 ]. In 30 articles, the survey was conducted on two or more types of professionals [ 13 , 14 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 49 , 53 , 56 , 57 , 62 , 64 , 71 ] and in one study the survey was conducted on health professionals and patients [ 16 ].

3.3 Sample Size and Response Rate

The sample size (see Online Resource Table S1) varied between 80 [ 23 , 77 ] and 3351 [ 57 ]. A total of 41 articles presented a sample of more than 200 subjects [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 ], 9 had more than 1000 subjects [ 19 , 39 , 40 , 49 , 57 , 62 , 67 , 73 ], and 3 did not mention the sample size [ 16 , 25 , 44 ].

In the articles that mentioned response rate, this varied between 16.4% [ 67 ] and 100% [ 17 , 22 , 23 , 34 , 63 , 76 ] (see Online Resource Table S2). More than half of the articles had response rates > 50% [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 68 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 ], and six reached 100% [ 17 , 22 , 23 , 34 , 63 , 76 ]; nine articles did not mention the response rate [ 16 , 26 , 27 , 39 , 45 , 47 , 62 , 66 , 69 ].

3.4 Survey Distribution and Scale

The survey was distributed personally in more than half of the articles [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 53 , 54 , 56 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 , 64 , 65 , 72 , 74 , 76 , 77 ], and the remainder were sent by internet [ 16 , 25 , 26 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 52 , 57 , 62 ] or post [ 21 , 33 , 40 , 46 , 55 , 60 , 67 , 73 ], while 10.8% did not mention how the survey was distributed [ 32 , 34 , 43 , 45 , 63 , 69 , 71 ]. In four articles, two or more distribution types were combined [ 33 , 35 , 39 , 62 ] (see Online Resource Table S1)

The most used scale (Online Resource Table S1) to answer the survey questions was the Likert scale [ 15 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 32 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 51 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 65 , 66 , 75 , 77 ], followed by multiple-choice and free text [ 14 , 24 , 30 , 37 , 41 , 50 ], while one article used the visual analog scale [ 40 ]. It is noteworthy that almost half (28/65) of the articles did not mention the scale used [ 13 , 16 , 20 , 25 , 29 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 42 , 44 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 76 ]. In 19 articles, multiple scales were used [ 14 , 18 , 21 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 37 , 41 , 43 , 46 , 50 , 51 , 55 , 57 , 66 , 75 , 77 ].

3.5 Factors Identified as Influential

Each of the selected articles was evaluated to identify the factors said to influence ADR underreporting.

3.5.1 Personal and Professional Factors

Regarding the personal and professional factors that influence ADR reporting (see Online Resource Table S2), years of experience stands out, with 12.3% (8 articles), training and profession were cited in 10.8% of the articles (7/65), age and workplace in 9.2% (6/65), qualification in 7.7% (5/65), and sex in 6.2% (4/65).

3.5.2 Influence of Knowledge and Attitudes

Table 1 , Online Resource Table S2, and Online Resource Table S3 show that the most reported reasons by professionals for not reporting ADRs were lethargy and ignorance, followed by other reasons, such as lack of confidence and complacency: (1) ignorance in 56 (86.2%) articles, with an average of respondents who stated that attitude determines their ADR reporting (respondents average of 37.8%); (2) lethargy is described in 55 (84.6%) articles (respondents average of 33.3%); (3) other reasons (lack of internet access, lack of employer support, patient management is more important) in 38 (58.5%) articles (respondents average of 16.3%); (4) complacency (respondents average of 28.6%) in 30 (46.2%) articles; (5) diffidence (respondents average of 26.9%) in 29 (44.6%) articles; (6) unavailability of the reporting form (respondents average of 37.4%) and insecurity in 22 (33.8%) articles (respondents average of 34.4%); (7) legal aspects in 19 (29.2%) articles (respondents average of 19.5%); (8) indifference in 18 (27.7%) articles (respondents average of 23.5%); (9) financial reimbursement in 14 (21.5%) articles (respondents average of 22.2%); (10) lack of information in 13 (20.0%) articles (respondents average of 23.3%); (11) obligation or duty to inform in 12 (18.5%) articles (respondents average of 20.9%); (12) fear in 7 (10.8%) articles (respondents average of 24.5%); (13) confidentiality of both the patient and the professional (respondents average of 13.4%) and feedback in 6 (9.2%) articles (respondents average of 29.4%); and (14) ambition in 2 (3.1%) articles (respondents average of 15.9%).

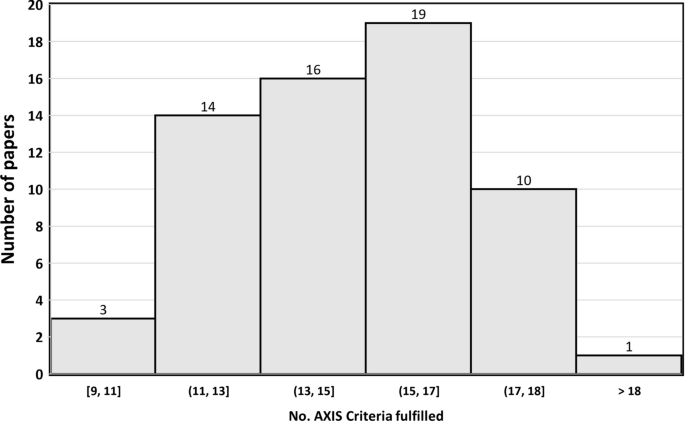

3.6 AXIS Tool

The results of AXIS tool evaluation (see Online Resource Table S1, and Fig. 2 ) indicated that 29.2% (19/65) of the studies met more than 17 AXIS criteria (see Table S1), almost half of the studies (29/65, 44.6%) met 14–16 criteria, and about one-quarter of the studies (17/65, 26.2%) met 13 or fewer criteria.

Distribution of papers by the number of AXIS criteria fulfilled

The criteria “Were the aims/objectives of the study clear?”, “Were the risk factor and outcome variables measured appropriate to the aim of the study”, and “Were the basic data adequately described?” were fulfilled in all articles.

In contrast, no articles met the criteria “If appropriate, was information about non-responders described?”, only 13 met the criteria “Were measures undertaken to address and categorize non-responders?”, and 34 met the criteria “Was the selection process likely to select subjects/participants that were representative of the target/reference population under investigation?”.

3.7 Sensitivity Analysis: Results for the Highest-Quality Studies

The median AXIS score was 16 criteria. Table 1 shows the most frequent criteria among the 32 articles with the highest degree of evidence. It is observed that ignorance (90.6%), lethargy (81.3%), complacency (43.8%), and difference (40.6%) were the most named attitudes on the part of health professionals, results very similar to the total of the studies.

4 Discussion

This review was based on more studies than our 2009 review (65 vs. 45) [ 8 ] and has confirmed and extended the previous findings: health professionals’ attitudes to ADRs, modeled through Inman’s ‘seven deadly sins’, continue to be the most important determinants of underreporting, and personal and professional characteristics continue to show little influence. In addition, the new information included in the current review allowed to associate the perception of absence of an obligation to notify and the lack of information and confidentiality with the underreporting. These results can help design interventions that improve ADR reporting, since the main reasons found in this review are potentially modifiable.

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics are only cited as factors associated with the reporting of ADRs in fewer than half of the articles included and yet attitudes and knowledge are cited in one way or another in almost all the articles. These factors can be grouped into four categories [ 8 , 78 ]: (1) factors associated with ADR-related knowledge and attitudes (fear, complacency, insecurity, diffidence, indifference, and ignorance); (2) factors relating to the professional activity (financial incentives, legal aspects, and ambition to publish); (3) excuses made by professionals (lethargy, unavailability of the reporting form); and (4) there is another group of factors, such as the absence of an obligation to notify, lack of information or confidentiality, which emerge in this review as being associated with underreporting.

4.1 Adverse Drug Reaction-Related Knowledge and Attitudes

Inman’s knowledge/attitude related to ‘sins’ show associations with underreporting in a high proportion of studies. Thus, ignorance about pharmacovigilance, how to recognize ADRs, which types and how they should be reported, as well as the requirements needed and what has to be done with the submitted report, was the attitude that most conditioned underreporting in our review (52/65), which is consistent with other systematic reviews [ 8 , 79 , 80 ]. Related to ignorance is complacency , which is based on the conviction that adverse reactions of medication are known when the drug comes on to the market and that only well tolerated medications are marketed, and appears to be associated with reporting of a figure very similar to that of the previous revision of 2009. This seems to indicate that there have been no significant advances in the training of health professionals on ADR since ignorance and complacency are potentially modified through training on undergraduate[ 81 , 82 ] and postgraduate pharmacovigilance education [ 81 ]. In this sense, educational sessions (workshops or lectures) [ 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 ] showed a positive impact on ADR reporting. Nonetheless, the increased rate of SR originated was shown to decrease over time [ 83 , 84 , 88 ]. Consequently, interventions should be carried out periodically and not only reinforce what has been learned but also provide information on possible updates that may have occurred. It could also be interesting to try nudge strategies, which have been shown to be effective in improving the behaviors of health professionals in other fields [ 89 ].

A diffidence attitude results in the lack of confidence and fear of appearing ridiculous (a sentiment of ‘foolish’) either by the diagnosis made or for reporting a suspicious ADR, hence the thought to only report if the health professional is totally sure the ADR was due to a given medicine. This reason can be related to the thought that it is impossible to have certainty and the concern that the report may be wrong ( insecurity ). Once again, we would like to emphasize the importance of education and practical training with constant contact with ADR cases to further improve confidence and certainty.

4.2 Factors Related to Professional Activity

Compared with the 2009 review, a lower proportion of legal aspects have been reported (29/45 vs. 19/65). However, in this review, a new factor related to legal aspects that had not been detected in the previous review has emerged: patient confidentiality , which appears in 9% of the articles. On the other hand, ‘ Financial reimbursement’ is reported in a higher proportion (21% of articles) as a reason for not reporting an ADR compared with the previous review (11%). In fact, interventions based on economic incentives have been shown to be effective [ 90 , 91 , 92 ], which is consistent with the perception that reporting is not the health professionals professional duty, reported in 18% of articles.

4.3 Excuses

The third group encompasses attitudes related to excuses, such as lethargy (procrastination and postponing the notification, lack of time or motivation, effort or interest to report, need for an easier method, the report will generate extra work, and forgetfulness), which is the most frequent reason for not reporting (53/65; 81%). This can be combated by providing health professionals with training (emphasizing the sort time needed to report [ 84 ]), facilitating the notification process, or eliminating the barriers they have to notify ADRs [ 8 ]. Another frequent excuse is the unavailability of a yellow card/ADR form or a shipping address. In this sense, interventions based on the use of information systems (active or passive) and use of an electronic reporting tool has been seen to increase notification. Strategies such as web-based software, hyperlinks, telephone applications, online reporting form, and electronic health records are examples that have emerged with this advance [ 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 ].

4.4 Other Reasons

This was the third most cited reason by healthcare professionals and includes statements related to lack of feedback from the national regulatory authorities on the submitted form, lack of training, and lack of enough information about the patient to make the report. We believe this is understandable, i.e. the lack of feedback can discourage reporting as people expect to receive feedback to know if what they did was correct. Receiving personalized feedback on the reporting procedure has been described as a motive for reporting ADRs [ 21 , 73 , 100 , 101 ]. The lack of information may, for example, be tackled by increasing the consultation time, sharing information from different databases, or even registering a telephone or email contact to clarify doubts at any time.

4.5 Methodology Discussion of the Included Studies

From the methodological point of view and compared with the previous review of 2009, a significant methodological improvement is observed in many aspects, fundamentally in terms of specification of the design (64/65 vs. 3/45 in the 2009 review) and sample size (41/65 articles have more than 200 subjects vs. 25/45 in the 2009 review). The percentage of responses is also higher among the articles included in this review (average of 75% vs. 64% in the 2009 review). Nevertheless, some AXIS factors, especially those linked to non-responders are still not sufficiently described. However sensitivity analysis to assess whether the results of the current review were influenced by the quality of the articles showed that the results for half of the studies that met more AXIS criteria were very similar to the overall review. Finally, the geographical distribution of our review focuses more on Asian and African countries, while the 2009 review focused on European countries. Despite this difference, the findings on the influence of attitudes are similar.

4.6 Limitations

This systematic review has several limitations. First, the great variety of methods used in the articles. The study population, the selected place/setting, the survey distribution, or the scale are very heterogeneous. In two articles, the study was carried out before the implementation of the pharmacovigilance system.

Second, it is common that when the study population includes various groups of health professionals, the results are not shown stratified by health professional type, which prevents us from detecting which factors are associated with each profession and makes comparison between studies difficult.

Third, regarding the reasons cited for underreporting, very few articles conducted the survey using Inman’s reasons as items. The definition of ‘sins’ was not exactly the same in all the articles and therefore the interpretations, both of the authors and those made in this systematic review, may differ from the reasons cited by Inman.

Finally, although an improvement in methodological quality is observed with respect to the 2009 review, great heterogeneity is observed in the fullfilment of the AXIS tool criteria.

5 Conclusion

The results of this review show that, as seen in the 2009 review, low ADR reporting is still associated with a series of attitudes (ignorance, lack of confidence, or complacency) and excuses that are potentially modifiable through training or by facilitating the notification process. This suggests that over the last decade there have been no significant advances in the training of health professionals on ADR reporting and that it is necessary for health systems and undergraduate (academy/training levels, or courses) centers to deepen the training of health professionals on the subject of drug safety. This would provide a greater capacity to activate early warnings to the pharmacovigilance systems and thus allow the health authorities to react more quickly to ensure that the least possible number of patients are affected.

Montané E, Santesmases J. Adverse drug reaction. Med Clin (Bar). 2020;154(5):178–1842.

Article Google Scholar

Taché SV, Sönnichsen A, Ashcroft DM. Prevalence of adverse drug events in ambulatory care: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(7–8):977–89. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1P627 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bouvy JC, De Bruin ML, Koopmanschap MA. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in Europe: a review of recent observational studies. Drug Saf. 2015;38(5):437–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-015-0281-0 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000;284(4):483–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.4.483 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Goldman SA. Limitations and strengths of spontaneous reports data. Clin Ther. 1998. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80007-6 .

Hazell L, Shakir SAW. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions. A systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006;29(5):385–96. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200932010-00002 .

Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A, Polónia J, et al. Physicians’ attitudes and adverse drug reaction reporting. Drug Saf. 2005;28:825–33. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528090-00007 .

Lopez-Gonzalez E, Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A. Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32(1):19–31.

Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12): e011458.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Inman WHW, Weber JCT. The United Kingdom. In: Inman WHW, editor. Monitoring for drug safety. 2nd ed. Lancaster: MTP Press Ltd; 1986. p. 13–47.

Google Scholar

Inman WHW. Assessment of drug safety problems. In: Gent M, Shigmatsu I, editors. Epidemiological issues in reported drug-induced illnesses. Honolulu: McMaster University Library Press; 1976. p. 17–24.

Inman WH. Attitudes to adverse drug reaction reporting. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41(5):434–5.

Haines HM, Meyer JC, Summers RS, Godman BB. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of health care professionals towards adverse drug reaction reporting in public sector primary health care facilities in a South African district. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(7):991–1001.

Gidey K, Seifu M, Hailu BY, Asgedom SW, Niriayo YL. Healthcare professionals knowledge, attitude and practice of adverse drug reactions reporting in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2): e034553.

Nadew SS, Beyene KG, Beza SW. Adverse drug reaction reporting practice and associated factors among medical doctors in government hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):1–19.

Melo JRR, Duarte EC, de Araújo FK, et al. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions among healthcare professionals in Brazil: an estimate based on national pharmacovigilance survey. J Young Pharm. 2020;12(4):360–5.

Braiki R, Douville F, Hasine AB, Souli I. Facteurs liés au signalement des évènements indésirables associés aux soins dans un hôpital Tunisien. Sante Publique. 2019;31(4):553–9.

Kassa Alemu B, Biru TT. Health care professionals' knowledge, attitude, and practice towards adverse drug reaction reporting and associated factors at selected public hospitals in Northeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int. 2019; 8690546.

Le TT, Nguyen TTH, Nguyen C, Tran NH, Tran LA, Nguyen TB, Nguyen N, Nguyen HA. Factors associated with spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting among healthcare professionals in Vietnam. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45(1):122–7.

Kopciuch D, Zaprutko T, Paczkowska A, Ratajczak P, Zielińska-Tomczak Ł, Kus K, Nowakowska E. Safety of medicines-pharmacists’ knowledge, practice, and attitudes toward pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reactions reporting process. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(12):1543–51.

Hughes ML, Weiss M. Adverse drug reaction reporting by community pharmacists—the barriers and facilitators. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(12):1552–9.

Danekhu K, Shrestha S, Aryal S, Shankar PR. Health-care professionals’ knowledge and perception of adverse drug reaction reporting and pharmacovigilance in a tertiary care teaching hospital of Nepal. Hosp Pharm. 2021;56(3):178–86.

Adisa R, Omitogun TI. Awareness, knowledge, attitude and practice of adverse drug reaction reporting among health workers and patients in selected primary healthcare centres in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):926.

Ergün Y, Ergün TB, Toker E, Ünal E, Akben M. Knowledge attitude and practice of Turkish health professionals towards pharmacovigilance in a university hospital. Int Health. 2019;11(3):177–84.

Thompson A, Randall C, Howard J, Barker C, Bowden D, Mooney P, et al. Nonmedical prescriber experiences of training and competence to report adverse drug reactions in the UK. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2019;44(1):78–83.

Li R, Curtain C, Bereznicki L, Zaidi STR. Community pharmacists’ knowledge and perspectives of reporting adverse drug reactions in Australia: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(4):878–89.

Seid MA, Kasahun AE, Mante BM, Gebremariam SN. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting at the health center level in Ethiopia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(4):895–902.

Bahnassi A, Al-Harbi F. Syrian pharmacovigilance system: a survey of pharmacists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices. East Mediterr Health J. 2018;24(6):569–78.

Lemay J, Alsaleh FM, Al-Buresli L, Al-Mutairi M, Abahussain EA, Bayoud T. Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions in Primary Care Settings in Kuwait: A Comparative Study of Physicians and Pharmacists. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(1):30–8.

Terblanche A, Meyer JC, Godman B, Summers RS. Knowledge, attitudes and perspective on adverse drug reaction reporting in a public sector hospital in South Africa: baseline analysis. Hosp Pract (1995). 2017;45(5):238–45.

Hajj A, Hallit S, Ramia E, Salameh P, Order of Pharmacists Scientific Committee – Medication Safety Subcommittee. Medication safety knowledge, attitudes and practices among community pharmacists in Lebanon. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(1):149–56.

Abu Hammour K, El-Dahiyat F, Abu FR. Health care professionals knowledge and perception of pharmacovigilance in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Amman, Jordan. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(3):608–13.

Cheema E, Haseeb A, Khan TM, Sutcliffe P, Singer DR. Barriers to reporting of adverse drugs reactions: a cross sectional study among community pharmacists in United Kingdom. Pharm Pract. 2017;15(3):931.

Gurmesa LT, Dedefo MG. Factors affecting adverse drug reaction reporting of healthcare professionals and their knowledge, attitude, and practice towards ADR reporting in Nekemte Town, West Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5728462.

Almandil NB. Healthcare professionals’ awareness and knowledge of adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance. Saudi Med J. 2016;37(12):1359–64.

Stergiopoulos S, Brown CA, Felix T, Grampp G, Getz KA. A survey of adverse event reporting practices among US healthcare professionals. Drug Saf. 2016;39(11):1117–27.

Peymani P, Tabrizi R, Afifi S, Namazi S, Heydari ST, Shirazi MK, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of General Practitioners towards adverse drug reaction reporting in South of Iran, Shiraz (Pharmacoepidemiology report). Int J Risk Saf Med. 2016;28(1):25–31.

Amin MN, Khan TM, Dewan SM, Islam MS, Moghal MR, Ming LC. Cross-sectional study exploring barriers to adverse drug reactions reporting in community pharmacy settings in Dhaka, Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8): e010912.

Yu YM, Lee E, Koo BS, Jeong KH, Choi KH, Kang LK, Lee MS, Choi KH, Oh JM, Shin WG. Predictive factors of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(5): e0155517.

Mendes Marques JI, Polónia JM, Figueiras AG, Costa Santos CM, Herdeiro MT. Nurses’ attitudes and spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting: a case-control study in Portugal. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(3):409–16.

Cerruti L, Lebel D, Bussières JF. Perception de la pharmacovigilance par les pharmaciens hospitaliers québécois [Hospital pharmacists’ perception of pharmacovigilance in Quebec]. Ann Pharm Fr. 2016;74(2):137–45.

Katusiime B, Semakula D, Lubinga SJ. Adverse drug reaction reporting among health care workers at Mulago National Referral and Teaching hospital in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(4):1308–17.

De Angelis A, Giusti A, Colaceci S, Vellone E, Alvaro R. Nurses’ reporting of suspect adverse drug reactions: a mixed-methods study. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015;51(4):277–83.

PubMed Google Scholar

Alshammari TM, Alamri KK, Ghawa YA, Alohali NF, Abualkol SA, Aljadhey HS. Knowledge and attitude of health-care professionals in hospitals towards pharmacovigilance in Saudi Arabia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(6):1104–10.

Nde F, Fah AB, Simo FA, Wouessidjewe D. State of knowledge of Cameroonian drug prescribers on pharmacovigilance. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:70.

Liu J, Zhou Z, Yang S, Feng B, Zhao J, Liu H, Huang H, Fang Y. Factors that affect adverse drug reaction reporting among hospital pharmacists in Western China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(3):457–64.

Tandon VR, Mahajan V, Khajuria V, Gillani Z. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a challenge for pharmacovigilance in India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47(1):65–71.

Sabblah GT, Akweongo P, Darko D, Dodoo AN, Sulley AM. Adverse drug reaction reporting by doctors in a developing country: a case study from Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2014;48(4):189–93.

Kiguba R, Karamagi C, Waako P, Ndagije HB, Bird SM. Recognition and reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions by surveyed healthcare professionals in Uganda: key determinants. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11): e005869.

Afifi S, Maharloui N, Peymani P, Namazi S, Gharaei AG, Jahani P, Lankarani KB. Adverse drug reactions reporting: pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude and practice in Shiraz. Iran Int J Risk Saf Med. 2014;26(3):139–45.

Elkalmi RM, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MI, Jamshed SQ, Al-Lela OQ. Community pharmacists’ attitudes, perceptions, and barriers toward adverse drug reaction reporting in Malaysia: a quantitative insight. J Patient Saf. 2014;10(2):81–7.

Wilbur K. Pharmacovigilance in Qatar: a survey of pharmacists. East Mediterr Health J. 2013;19(11):930–5.

Sanghavi DR, Dhande PP, Pandit VA. Perception of pharmacovigilance among doctors in a tertiary care hospital: influence of an interventional lecture. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2013;25(4):197–204.

Stoynova V, Getov IN, Naseva EK, Lebanova HV, Grigorov EE. Physicians’ knowledge and attitude towards adverse event reporting system and result to intervention-randomized nested trial among Bulgarian physicians. Med Glas (Zenica). 2013;10(2):365–72.

Yip J, Radford DR, Brown D. How do UK dentists deal with adverse drug reaction reporting? Br Dent J. 2013;214(8):E22.

Santosh KC, Tragulpiankit P, Gorsanan S, Edwards IR. Attitudes among healthcare professionals to the reporting of adverse drug reactions in Nepal. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;14:16.

Stewart D, MacLure K, Paudyal V, Hughes C, Courtenay M, McLay J. Non-medical prescribers and pharmacovigilance: participation, competence and future needs. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(2):268–74.

Agarwal R, Daher AM, Mohd IN. Knowledge, practices and attitudes towards adverse drug reaction reporting by private practitioners from Klang Valley in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2013;20(2):52–61.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pimpalkhute SA, Jaiswal KM, Sontakke SD, Bajait CS, Gaikwad A. Evaluation of awareness about pharmacovigilance and adverse drug reaction monitoring in resident doctors of a tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian J Med Sci. 2012;66(3–4):55–61.