- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Training and Development

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works

- Instructional Systems Design

- Needs Assessment

- Training Methods

- Pre-training Interventions

- Training Media

- Training Teams

- Training Evaluation

- Learner Characteristics

- Learning Context

- Employee Development

- Macroperspectives

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Alternative Work Arrangements

- Career Studies

- Career Transitions and Job Mobility

- Global Human Resources

- Goal Setting

- Human Resource Management

- Organization Culture

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Diversity and Firm Performance

- Executive Succession

- Organization Design

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Training and Development by Kenneth G. Brown LAST REVIEWED: 26 October 2015 LAST MODIFIED: 26 October 2015 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199846740-0013

Training and development is the study of how structured experiences help employees gain work-related knowledge, skill, and attitudes. It is like many other topics in management in that it is inherently multidisciplinary in nature. At its core is the psychological study of learning and transfer. A variety of disciplines offer insights into this topic, including, but not limited to, industrial and organizational psychology, educational psychology, human resource development, organizational development, industrial and labor relations, strategic management, and labor economics. The focus of this bibliography is primarily psychological with an emphasis on theory and practice that examines training processes and the learning outcomes they seek to influence. Nevertheless, literature from other perspectives will be introduced on a variety of topics within this area of study.

These articles and chapters provide background for the study of training and development, particularly as studied by management scholars with backgrounds in human resource management, organizational behavior, human resource development, and industrial and organizational psychology. Kraiger 2003 examines training from three different perspectives. Aguinis and Kraiger 2009 provides a narrative review of ten years of research on training and employee development, focusing on the many benefits of providing structured learning experiences to employees. Brown and Sitzmann 2011 also reviews the literature and emphasizes research on the processes that are required to ensure that training benefits emerge. Arthur, et al. 2003 meta-analyzes the literature on training effectiveness. Russ-Eft 2002 proposes a typology of training designs. Salas, et al. 2012 offers recommendations for evidence-based training practice. Noe, et al 2014 examines training in a broader context, relative to the roles of informal learning and knowledge transfer.

Aguinis, Herman, and Kurt Kraiger. “Benefits of Training and Development for Individuals and Teams, Organizations, and Society.” Annual Review of Psychology 60.1 (January 2009): 451–474.

DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163505

A comprehensive review of training and development literature from 1999 to 2009 with an emphasis on the benefits that training offers across multiple levels of analysis.

Arthur, Winfred A., Jr., Winston Bennett Jr., Pamela S. Edens, and Suzanne T. Bell. “Effectiveness of Training in Organizations: A Meta-analysis of Design and Evaluation Features.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88.2 (April 2003): 234–245.

DOI: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.2.234

Offers a comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationships among training design and evaluation features and various training effectiveness outcomes (reaction, learning, behavior, and results).

Brown, Kenneth G., and Traci Sitzmann. “Training and Employee Development for Improved Performance.” In APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology . Vol. 2, Selecting and Developing Members for the Organization . Edited by Sheldon Zedeck, 469–503. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2011.

DOI: 10.1037/12170-000

A comprehensive review of training and development in work organizations with an emphasis on the processes necessary for training to be effective for improving individual and team performance.

Kraiger, Kurt. “Perspectives on Training and Development.” In Handbook of Psychology . Vol. 12. Edited by Irving B. Weiner and Walter C. Borman, Daniel R. Ilgen, and Richard J. KIlimoski, 171–192. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2003.

DOI: 10.1002/0471264385

Reviews training literature from three perspectives: instruction, learning, and organizational change.

Noe, Raymond A., Alena D. M. Clarke, and Howard J. Klein. “Learning in the Twenty-first-century Workplace.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1 (2014): 245–275.

DOI: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091321

A review that places training and development in a broader context with other learning-related interventions and practices such as informal learning and knowledge sharing. The chapter explains factors that facilitate learning in organizations.

Russ-Eft, Darlene. “A Typology of Training Design and Work Environment Factors Affecting Workplace Learning and Transfer.” Human Resource Development Review 1 (March 2002): 45–65.

DOI: 10.1177/1534484302011003

Presents a typology summarizing elements of training and work environments that foster transfer of training.

Salas, Eduardo, Scott I. Tannenbaum, Kurt Kraiger, and Kimberly A. Smith-Jentsch. “The Science of Training and Development in Organizations: What Matters in Practice.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest 13.2 (2012): 74–101.

DOI: 10.1177/1529100612436661

Reviews meta-analytic evidence and offers evidence-based recommendations for maximizing training effectiveness.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Management »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abusive Supervision

- Adverse Impact and Equal Employment Opportunity Analytics

- Alliance Portfolios

- Applied Political Risk Analysis

- Approaches to Social Responsibility

- Assessment Centers: Theory, Practice and Research

- Attributions

- Authentic Leadership

- Bayesian Statistics

- Behavior, Organizational

- Behavioral Approach to Leadership

- Behavioral Theory of the Firm

- Between Organizations, Social Networks in and

- Brokerage in Networks

- Business and Human Rights

- Certified B Corporations and Benefit Corporations

- Charismatic and Innovative Team Leadership By and For Mill...

- Charismatic and Transformational Leadership

- Compensation, Rewards, Remuneration

- Competitive Dynamics

- Competitive Heterogeneity

- Competitive Intensity

- Computational Modeling

- Conditional Reasoning

- Conflict Management

- Considerate Leadership

- Cooperation-Competition (Coopetition)

- Corporate Philanthropy

- Corporate Social Performance

- Corporate Venture Capital

- Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB)

- Cross-Cultural Communication

- Cross-Cultural Management

- Cultural Intelligence

- Culture, Organization

- Data Analytic Methods

- Decision Making

- Dynamic Capabilities

- Emotional Labor

- Employee Aging

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Ownership

- Employee Voice

- Empowerment, Psychological

- Entrepreneurial Firms

- Entrepreneurial Orientation

- Entrepreneurship

- Entrepreneurship, Corporate

- Entrepreneurship, Women’s

- Equal Employment Opportunity

- Faking in Personnel Selection

- Family Business, Managing

- Financial Markets in Organization Theory and Economic Soci...

- Findings, Reporting Research

- Firm Bribery

- First-Mover Advantage

- Fit, Person-Environment

- Forecasting

- Founding Teams

- Global Leadership

- Global Talent Management

- Grounded Theory

- Hofstedes Cultural Dimensions

- Human Capital Resource Pipelines

- Human Resource Management, Strategic

- Human Resources, Global

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Work Psychology

- Humility in Management

- Impression Management at Work

- Influence Strategies/Tactics in the Workplace

- Information Economics

- Innovative Behavior

- Intelligence, Emotional

- International Economic Development and SMEs

- International Economic Systems

- International Strategic Alliances

- Job Analysis and Competency Modeling

- Job Crafting

- Job Satisfaction

- Judgment and Decision Making in Teams

- Knowledge Sharing and Collaboration within and across Firm...

- Leader-Member Exchange

- Leadership Development

- Leadership Development and Organizational Change, Coaching...

- Leadership, Ethical

- Leadership, Global and Comparative

- Leadership, Strategic

- Learning by Doing in Organizational Activities

- Management History

- Management In Antiquity

- Managerial and Organizational Cognition

- Managerial Discretion

- Meaningful Work

- Multinational Corporations and Emerging Markets

- Neo-institutional Theory

- Neuroscience, Organizational

- New Ventures

- Organization Design, Global

- Organization Development and Change

- Organization Research, Ethnography in

- Organization Theory

- Organizational Adaptation

- Organizational Ambidexterity

- Organizational Behavior, Emotions in

- Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs)

- Organizational Climate

- Organizational Control

- Organizational Corruption

- Organizational Hybridity

- Organizational Identity

- Organizational Justice

- Organizational Legitimacy

- Organizational Networks

- Organizational Paradox

- Organizational Performance, Personality Theory and

- Organizational Responsibility

- Organizational Surveys, Driving Change Through

- Organizations, Big Data in

- Organizations, Gender in

- Organizations, Identity Work in

- Organizations, Political Ideology in

- Organizations, Social Identity Processes in

- Overqualification

- Paternalistic Leadership

- Pay for Skills, Knowledge, and Competencies

- People Analytics

- Performance Appraisal

- Performance Feedback Theory

- Planning And Goal Setting

- Proactive Work Behavior

- Psychological Contracts

- Psychological Safety

- Real Options Theory

- Recruitment

- Regional Entrepreneurship

- Reputation, Organizational Image and

- Research, Ethics in

- Research, Longitudinal

- Research Methods

- Research Methods, Qualitative

- Resource Redeployment

- Resource-Dependence Theory

- Response Surface Analysis, Polynomial Regression and

- Role of Time in Organizational Studies

- Safety, Work Place

- Selection, Applicant Reactions to

- Self-Determination Theory for Work Motivation

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy In Management

- Self-Management and Personal Agency

- Sensemaking in and around Organizations

- Service Management

- Shared Team Leadership

- Social Cognitive Theory

- Social Evaluation: Status and Reputation

- Social Movement Theory

- Social Ties and Network Structure

- Socialization

- Sports Settings in Management Research

- Stakeholders

- Status in Organizations

- Strategic Alliances

- Strategic Human Capital

- Strategy and Cognition

- Strategy Implementation

- Structural Contingency Theory/Information Processing Theor...

- Team Composition

- Team Conflict

- Team Design Characteristics

- Team Learning

- Team Mental Models

- Team Newcomers

- Team Performance

- Team Processes

- Teams, Global

- Technology and Innovation Management

- Technology, Organizational Assessment and

- the Workplace, Millennials in

- Theory X and Theory Y

- Time and Motion Studies

- Training and Development

- Trust in Organizational Contexts

- Unobtrusive Measures

- Virtual Teams

- Whistle-Blowing

- Work and Family: An Organizational Science Overview

- Work Contexts, Nonverbal Communication in

- Work, Mindfulness at

- Workplace Aggression and Violence

- Workplace Coaching

- Workplace Commitment

- Workplace Gossip

- Workplace Meetings

- Workplace, Spiritual Leadership in the

- World War II, Management Research during

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society

Affiliation.

- 1 The Business School, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado 80217-3364, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 18976113

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163505

This article provides a review of the training and development literature since the year 2000. We review the literature focusing on the benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society. We adopt a multidisciplinary, multilevel, and global perspective to demonstrate that training and development activities in work organizations can produce important benefits for each of these stakeholders. We also review the literature on needs assessment and pretraining states, training design and delivery, training evaluation, and transfer of training to identify the conditions under which the benefits of training and development are maximized. Finally, we identify research gaps and offer directions for future research.

Publication types

- Health Services Needs and Demand

- Inservice Training*

- Organizational Objectives

- Outcome and Process Assessment, Health Care

- Social Values

- Staff Development*

- Transfer, Psychology

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A LITERATURE REVIEW ON TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT AND QUALITY OF WORK LIFE

In this competitive world, training plays an important role in the competent and challenging format of business. Training is the nerve that suffices the need of fluent and smooth functioning of work which helps in enhancing the quality of work life of employees and organizational development too. Development is a process that leads to qualitative as well as quantitative advancements in the organization, especially at the managerial level, it is less considered with physical skills and is more concerned with knowledge, values, attitudes and behaviour in addition to specific skills. Hence, development can be said as a continuous process whereas training has specific areas and objectives. So, every organization needs to study the role, importance and advantages of training and its positive impact on development for the growth of the organization. Quality of work life is a process in which the organization recognizes their responsibility for excellence of organizational performance as well as employee skills. Training implies constructive development in such organizational motives for optimum enhancement of quality of work life of the employees. These types of training and development programs help in improving the employee behaviour and attitude towards the job and also uplift their morale. Thus, employee training and development programs are important aspects which are needed to be studied and focused on. This paper focuses and analyses the literature findings on importance of training and development and its relation with the employees' quality of work life.

Related Papers

IAEME Publication

Quality of Work Life (QWL) of employees in any organization plays a very vital role in shaping of both the employees and the organization. The objective of this research is to highlight the prominence of training and development programmes adopted in manufacturing industries encompassing the private and public sectors and the impact that it exerts on the quality of work life of employees in these sectors. It is assumed that employees who undergo T & D programme either in private or public sectors enjoy better QWL. Here a comparative study among the employees of private and public manufacturing industries is carried out to measure the QWL of employees in these respective sectors. Hence the research concludes that the QWL enjoyed by the employees of private industries is superior to the QWL of employees of public industries.

Noble Academic Publisher

josiah emmanuel

International Journal of Latest Technology in Engineering, Management & Applied Science -IJLTEMAS (www.ijltemas.in)

In this era where competition is increasing day by day in the corporate world training and development has become one of the important key to achieve success. Training is an important subsystem of Human Resource Development. It is a specialized function and is one of the fundamental operative functions for known resource management. Development is a long-term educational process utilizing a systematic and organized procedure by which managerial personnel get conceptual and theoretical knowledge. Basically, it is an attempt to improve the current or future employee performance of the employee by increasing his or her ability to perform through learning, usually by changing the employee’s attitude or increasing his or her skills and knowledge. These types of training and development programs help in improving the employee behavior and attitude towards the job and also uplift their morale. Thus, employee training and development programs are important aspects which are needed to be studied and focused on. This paper focusses on the advantages of the training and development for the employee’s.

International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology IJSRST

The purpose of this paper is to present a conceptual study established on the employee training and development program and its benefits. This paper will inspect the structure and elements of employee training and development program and later the study present what are the positive outcomes for employees and organizations. Training and development play an important role in the effectiveness of organizations and to the experiences of people in work. Training has implications for productivity, health and safety at work and personal development. Modern organizations therefore use their resources (money, time, energy, information, etc.) for permanent training and advancement of their employees. Training and development is an instrument that aid human capital in exploring their dexterity. Therefore training and development is vital to the productivity of organization " s workforce. The study described here is a vigilant assessment of literature on fundamental of employee development program and its benefits to organizations and employees.

Dr Yashpal D Netragaonkar

“ To Study the Effectiveness of Employees Training & Development Program ”. The prime objective of research is to study the changes in skill , attitude, knowledge, behavior of Employees after Training program. It also studies the effectiveness of Training on both Individual and Organizational levels. Due to this research we are able to absorb current trends related to whole academic knowledge a nd its practical use. Such research is exposed us to set familiar with professional environment, working culture, behavior, oral communication & manners. Since the training is a result oriented process and a lot of time and expenditure, it is necessary tha t the training program should be designed with a great care. For evaluating effectiveness if training a questionnaire has to be carefully prepared for participants in order to receive feedback.

Venkata Sandeep

Tolulope J Ogunleye

Overtime, study had shown that to be relevant in any field of work there is need for continuous learning through training and development. The study is aimed at finding out the need for employees training and development in an organization. The need for improvement to change the phenomenon of low productivity and poor service delivery attributed to the employee’s in-adequate experience, calls for investigation on how effective training and development of employee can facilitate improved corporate performance using the banking industry as a field of discuss.. The study concluded that training and development brings about career growth for the employees and bankers thus the study recommended that all organization must do induction training at entry point into the banking sector.

International Journal of Research Publication (IJRP)

IAEME PUBLICATION

Training and development enables to develop skills and competencies necessary to enhance bottom-line results for their organization. It is a key ingredient for organizational performance improvement. It ensures that randomness is reduced and learning or behavioural change takes place in structured format. Training and Development helps in increasing the job knowledge and skills of employees at each level and helps to expand the horizons of human intellect and an overall personality of the employees. This paper analyses the link between various Training and Development programs organized in Larsen &Toubro Group of Companies and their impacts on employee satisfaction and performance. Data for the paper have been collected through primary source that are from questionnaire, surveys. There were two variables: Training and Development (independent) and Employees satisfaction and performance (dependent). The goal was to see whether Training and development has an impact on employee’s satisfaction and performance

RELATED PAPERS

Stirling毕业证 li

Jumardi Ardi

Archives of Disease in Childhood

Elysse Grossi-Soyster

Pontic Treasures. Artefacts from the collections of the Museum of National History and Archaeology from Constanţa I, 2024, pp. 92-97

Radu Petcu , Ingrid Petcu-Levei

Fernando Martin-Sanchez

Neveléstudomány

Judit Hegedűs

Asaio Journal

Hiroaki Harasaki

ADAN HIDALGO GOMEZ

Endang Sutedja

Journal of Research & Health

Journal of Research and Health

Vjesnik Za Arheologiju I Historiju Dalmatinsku

Ivan Matijević

Journal of Advanced Mechanical Design, Systems, and Manufacturing

Industrial Crops and Products

Andres Gonzalez

Pharmaceutical and Biological Evaluations

Prof. Versha Parcha

Pathologie Biologie

abdeslam kartouti

Sergio Emilio Manosalva Mena

Bulletin of The World Health Organization

Dr. Sanjay Rastogi

Aydın Dental

Özlem Kanar

BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Frauke Musial

Mihaela Zagajšek

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Health Policy Manag

- v.5(12); 2016 Dec

Outcomes and Impact of Training and Development in Health Management and Leadership in Relation to Competence in Role: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review Protocol

Reuben olugbenga ayeleke.

1 Health Systems Section, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

Nicola North

Katharine ann wallis.

2 Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

Zhanming Liang

3 Department of Public Health, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

Annette Dunham

Background: The need for competence training and development in health management and leadership workforces has been emphasised. However, evidence of the outcomes and impact of such training and development has not been systematically assessed. The aim of this review is to synthesise the available evidence of the outcomes and impact of training and development in relation to the competence of health management and leadership workforces. This is with a view to enhancing the development of evidence-informed programmes to improve competence.

Methods and Analysis: A systematic review will be undertaken using a mixed-methods research synthesis to identify, assess and synthesise relevant empirical studies. We will search relevant electronic databases and other sources for eligible studies. The eligibility of studies for inclusion will be assessed independently by two review authors. Similarly, the methodological quality of the included studies will be assessed independently by two review authors using appropriate validated instruments. Data from qualitative studies will be synthesised using thematic analysis. For quantitative studies, appropriate effect size estimate will be calculated for each of the interventions. Where studies are sufficiently similar, their findings will be combined in meta-analyses or meta-syntheses. Findings from quantitative syntheses will be converted into textual descriptions (qualitative themes) using Bayesian method. Textual descriptions and results of the initial qualitative syntheses that are mutually compatible will be combined in mixed-methods syntheses.

Discussion: The outcome of data collection and analysis will lead, first, to a descriptive account of training and development programmes used to improve the competence of health management and leadership workforces and the acceptability of such programmes to participants. Secondly, the outcomes and impact of such programmes in relation to participants’ competence as well as individual and organisational performance will be identified. If possible, the relationship between health contexts and the interventions required to improve management and leadership competence will be examined

The healthcare system is complex, dynamic, constantly evolving, and a target of repeated reforms. These reforms have brought about changes to roles of those in health management and leadership and to the associated competence required to perform these roles. 1

The importance of developing and improving the competence of health management and leadership workforces through training and development programmes have been emphasised. 2 , 3 However, the effects of such programmes on competence and individual or organisational performance have not been assessed and synthesised systematically. Thus, questions arise as to whether or not the various interventions aimed at addressing the gaps in health management and leadership competence actually lead to improvement in individual and organisational performance. 4

Health management and leadership workforces play a crucial role in effective healthcare delivery, and in maximising the gains of the various reforms in the sector. 3 It is, therefore, pertinent to review available evidence of the overall effects of interventions to improve management and leadership competence. This, in turn, will inform appropriate policy formulation to enable competence improvement, and the development of evidence-informed and sustainable training and development programmes. With the recent upsurge in research in health management and leadership competence, this review is timely and necessary to ascertain where further research is required.

This review will make use of a mixed-methods research synthesis which could provide answers to a wide range of research questions which a single method approach might not address comprehensively.

Aim and Objectives

This review aims to critically appraise and synthesise empirical evidence of the outcomes and impact of training and development programmes in relation to the competence of health management and leadership workforces.

Review Questions

This review aims to answer the following questions:

- What training and development programmes are used to improve the competence of health management and leadership workforces, and are acceptable to participants?

- Do training and development programmes improve the competence of health management and leadership workforces?

- What are the characteristics of training and development programmes that are effective and appropriate for improving the competence of health management and leadership workforces?

This review will make use of the segregated approach to mixed-methods research synthesis. 5 Thus, qualitative and quantitative studies as well as the respective components of primary level mixed-methods studies will be analysed into two separate sets of syntheses. Where appropriate, quantitative and qualitative data will then be integrated into a single synthesis using Bayesian method. 6

The review will, therefore, involve:

- A synthesis of studies on the views, perspectives, or experiences of health management and leadership workforces on the outcomes and impact of the various training and development initiatives in relation to their competence and performance in roles;

- A synthesis of evidence of the effectiveness of training and development initiatives for improving the competence of health management and leadership workforces.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Types of study.

- Only empirical studies with qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods designs will be eligible for inclusion. Studies reporting the findings of empirical research without giving details of the primary studies will be excluded. Reviews and commentaries will also not be eligible for inclusion;

- Qualitative research of any design which focused on the perspectives, experiences, or narratives of participants will be considered for inclusion. This will include designs such as general inductive design, grounded theory, action research, ethnography, among others;

- Quantitative design will include experimental, quasi-experimental and non-experimental, or epidemiological study designs;

- Mixed-methods design will be studies that employed mixed primary level qualitative and quantitative research approaches;

- Only studies published in English language from 2000 to date will be eligible for inclusion as we consider the most recent publications to be more relevant to the current research efforts. However, seminal or germinal studies published prior to 2000 will be considered for inclusion.

Contexts or Settings

This review will examine the managerial and leadership competence of health managers and clinical leaders of health services and health organisations from different countries in relation to the health context in which the identified competence is required. Health context will be considered from the angle of the types of work and setting, which could include any of the following organisational settings:

- Public sector;

- Private sector;

- Non-governmental organisations, charitable or voluntary organisations.

Studies that selected participants from the following work settings will be included in this review:

- Hospital, including secondary and tertiary level care;

- Primary healthcare services;

- Community health services;

- Residential care services;

- Government ministries, departments and agencies responsible for policy formulation, funding, regulation, and administration;

- Other work settings considered by the reviewers to be health sector or related to health sector.

Participants

- Participants of the primary studies will be individuals with existing roles as managers or leaders in the health sector;

- Generalist managers, professional health service managers, and individuals trained in other professions (eg, clinicians, IT personnel) but were involved in management and/or leadership development activities by virtue of their roles or positions as managers and/or leaders (eg, project managers, team leaders) will be eligible for inclusion;

- All levels of management or leadership positions will be included: frontline, middle, senior, and executive levels;

- Studies examining the competence of health professionals who perform dual roles eg, clinical and management/leadership roles, will be eligible for inclusion, providing separate data are available for management and/or leadership roles;

- Studies investigating the competence of both management and non-management staff will be included, providing separate data are provided for participants in management and/or leadership roles;

- Studies examining the competence of prospective or newly employed health managers and/or leaders with no prior management and/or leadership experience will be excluded; studies investigating the competence of individuals previously engaged in management and/or leadership positions will also be excluded.

Interventions or Exposures

- This review will consider ‘interventions’ as any specific initiatives (both formal and informal) intended to improve the competence of personnel responsible for management and leadership roles in healthcare organisations;

- Such initiatives may include coaching, mentoring, supervision, continuing professional development, training, formal education, contextualised learning, or other specific initiatives which are considered by this review to be appropriate for improving the competence of health managers and leaders;

- Studies on measures or incentives to improve the performance of health workers, including management and leadership workforces, but which did not address management or leadership competence, will be excluded.

Comparators or Control

Where applicable, comparators or control will be non-exposure to the intervention of interest or exposure to an intervention which is considered by this review not to be related to improving the competence of health management and leadership workforces.

Outcome and Impact Measures

In this review, the terms ‘outcomes and impact’ will be defined, using the operational definitions of the Centre for Non-profit Management (CNM), the United States 7 as guides. Thus, outcomes refer to the measurable and specific effects of interventions (in the short and medium terms) such as the number of participants demonstrating changes in competence at the end of interventions. Impact, on the other hand, refer to the broad and long-term effects of interventions, either negative or positive, intended or un-intended; for example, changes in individual and organisational performance following completion of interventions.

Outcome and impact measures that will be considered in this review are those that will assist in addressing the research questions. Studies will not be excluded solely on the basis of not reporting any relevant outcome or impact measures, providing their designs, settings, participants and interventions meet the eligibility criteria for inclusion. Authors of such studies will be contacted for information on outcome and/or impact measures that could be relevant to the review. Final assessment of the outcomes and impact of training and development programmes will be based on studies that reported those data and on studies whose authors provided relevant information on outcome and/or impact measures following contact.

For the purpose of data synthesis and because of the possibility of studies reporting their findings at different end points, studies assessing the effects of interventions within each of the following time intervals will be regarded as similar in relation to timing of effect measures (such studies may be combined in meta-analysis or meta-synthesis, providing they are similar with respect to other characteristics ie, settings, participants, interventions and outcome or impact measures):

- Immediately at the end of intervention and up to three months after completion of intervention (short-term measures);

- More than three months and up to six months after completion of interventions (medium-term measures);

- More than six months and up to 12 months after completion of interventions (long-term measures).

The following primary and secondary outcome and impact measures will be considered:

Primary Outcome and Impact Measures

These will be assessed as the direct effects of interventions related to participants’ managerial and/or leadership competence and performance in roles.

Primary outcome measures will consist of the following:

- Objective assessment of competence or proficiency by participants, using standardised instruments;

- Objective assessment of competence or proficiency by stakeholders eg, participants’ superior officers and professional colleagues, using validated instruments;

- Subjective assessment of competence or proficiency from participants’ perspectives;

- Subjective assessment of competence or proficiency from stakeholders’ perspectives eg, participants’ superior officers and professional colleagues.

Primary impact measures will be:

- Participants’ performance in the related area following specific training or professional development inputs eg, financial performance, managerial and/or leadership performance.

Secondary Outcome and Impact Measures

These will be considered as the indirect effects of interventions related to individuals (participants) and/or organisations.

Secondary outcome measures will consist of:

- Costs associated with the intervention;

- Participants’ evaluation of the intervention in terms of their level of satisfaction with and acceptability of the interventions.

Secondary impact measures will consist of:

- Organisational performance in the related area following specific training or professional development inputs eg, quality of service, customer satisfaction, change in infection rates, morbidity and mortality rates, staff turnover.

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search for relevant studies will be undertaken. The main concepts addressed in the review (ie, impact, health leadership or management, competence, training or development and performance or outcome) will be searched using strings of subject headings (from either the controlled vocabulary or thesaurus as appropriate) and free-text. The search strategy will be designed by combining search strings for each of the key concepts so as to identify studies that focus on, for example, health AND (management or leadership) AND (training or development) AND competence. A number of search strategies will be combined and utilised, depending on the database, to locate studies,

Only studies published in English language from 2000 to date will be included in this review. However, seminal studies published prior to 2000 will be considered for inclusion. Subject-specific electronic databases will be searched to identify studies relevant to the review. Other electronic sources will be databases dedicated to review of research, dissertations and theses. For the full list of electronic databases and catalogue to be searched, see Appendix 1 .

Other potential sources will be searched to identify relevant studies. These will include hand searching of reference lists of included studies, conference proceedings, grey literature and websites of relevant health professional bodies, World Health Organization (WHO), and appropriate government agencies.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Selection of studies.

Search results will be uploaded into RefWorks or EndNote so as to identify and remove any duplicates. The list of titles and abstracts generated by the search will be screened independently by two reviewers to identify potentially relevant articles. Full-text articles of potentially relevant articles will be retrieved and assessed independently for eligibility by two reviewers in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Any difference in opinion between the two reviewers will be resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Management

Two reviewers will extract data independently from the included studies using data extraction forms specifically developed for each study design. Disagreement, if any, between the reviewers will be resolved through discussion or by seeking the opinion of a third reviewer. Data will be extracted from each of the included studies with respect to study designs, settings, participants, interventions, and outcome and impact measures considered relevant to the review questions. For qualitative studies, key themes will be coded according to the content of the findings of each study, using NVIVO software. For quantitative research, descriptive and outcome data will be checked and double entered into RevMan data management software. Where data are missing, unclear or presented in a form that cannot easily be extracted, study authors will be contacted for clarification or assistance with the process of data extraction.

Assessment of Methodological Quality/Risk of Bias of Studies

This review will make use of methodologically appropriate tools to critically appraise the methodological quality of included studies. These are the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) tool for quantitative studies, 8 the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies, 9 and a combination of these tools for mixed-methods designs.

The methodological quality of quantitative studies (ie, the risk of bias) will be assessed with respect to appropriateness of study design, process used in selecting participants, control for confounding factors, blinding of participants and/or personnel, including outcome assessors (researcher’s role and influence), follow up length, withdrawals/losses to follow up and reasons for withdrawals, data collection and analysis methods.

Qualitative studies will be assessed in relation to the appropriateness of qualitative design for the research question, appropriateness of the recruitment process, adequate description of data collection process and data analysis (rigor), researcher’s role and influence (bias) as well as the process to ensure credibility of the findings through, for example, triangulation and respondent validation.

Mixed-methods studies will be separated into their respective quantitative and qualitative components and assessed using the respective assessment tool for each study design. The outcomes of the assessment of the two separate components will be incorporated into the respective findings of the methodological assessment of the primary level quantitative and qualitative studies.

The overall quality of each study will be graded as ‘very good’ (high quality), ‘moderate’ or ‘weak’ (low quality) based on the average score for the domains assessed. No studies will be excluded on the basis of being of low quality; rather, the effect of inclusion of such low quality studies will be explored by using sensitivity analysis where appropriate. This will be done by considering the effect of removal of studies rated as low quality on the findings of both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Two reviewers will assess independently the methodological quality of studies. Any disagreement will be resolved through discussion or by consulting with a third reviewer.

Data Synthesis

Quantitative studies.

The effectiveness or otherwise of each intervention in improving the competence of participants will be determined by calculating, where appropriate, the effect size estimate for each intervention. Effect sizes will be expressed as odds ratio (OR) or risk ratio (RR) for categorical data and weighted mean difference (MD) for continuous data and 95% CIs will be calculated.

Studies that are sufficiently similar with respect to settings, participants, interventions and outcome or impact measures will be combined in meta-analysis. Where it is not possible to conduct meta-analysis due to substantial heterogeneity among studies, findings from individual studies will be presented in narrative analysis, using tables and figures as appropriate.

Qualitative Studies

Data from studies that examined the views, perspectives or experiences of participants will be synthesised thematically by two reviewers in accordance with the existing methods for thematic synthesis of qualitative research. 10 Findings of the included studies will be assembled and rated according to their quality and then categorised into themes and sub-themes based on their similarity in meaning. The emerging themes and sub-themes will be examined to see how they are related to the research questions.

Where studies are sufficiently similar with respect to settings, participants, interventions and outcome or impact measures, a single set of synthesised findings will be produced by pooling the emerging themes in a meta-synthesis. Otherwise, the findings from each study will be presented in narrative form in an evidence table, taking into consideration the quality and consistency of the findings as well as their applicability to the research questions.

Mixed-Methods Studies

Findings of mixed-methods studies will be separated into their respective quantitative and qualitative components. Where possible, the quantitative component will be included in the quantitative synthesis while the qualitative component will be incorporated into the qualitative synthesis.

Aggregation of Data/Mixed-Methods Synthesis

Findings from quantitative and qualitative studies will be analysed separately (as previously described) using the segregated approach 5 and integrated into two separate sets of data. Results from the initial quantitative syntheses will then be converted into textual descriptions (qualitative themes) using Bayesian method as described by Crandell and colleagues. 6 Textual descriptions and the initial synthesised findings from qualitative studies that are mutually compatible or sufficiently similar will then be combined to generate mixed-methods syntheses using appropriate mixed-methods research analytical/assessment instrument. However, where it is not possible to conduct meta-analysis or meta-synthesis due to insufficient studies or substantial heterogeneity (differences) among studies, findings from individual quantitative studies will be converted into textual forms and then combine with compatible themes from individual or synthesised qualitative findings.

Subgroup Analysis

Subject to the availability of sufficient studies, subgroup analysis will be conducted to examine the influence of health system contexts on training and development needs of health management and leadership workforces. Studies will be subgrouped by:

- Type of health sector (public, private; hospital, community health services);

- Location of health facility (urban, rural);

- Management and leadership level (front-line/middle, senior).

Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise information on training and development programmes which are used to improve the competence of health management and leadership workforces and the acceptability of such programmes to participants. The review will identify common characteristics of: (1) interventions found to have improved the competence of participants, and (2) those interventions considered to be ineffective. Success of interventions or otherwise will be determined by examining outcomes and impact at the individual level only. If possible, the effects of such interventions on organisational performance, mediated through improved competence, will be identified.

The contextual effects of health settings on the interventions, ie, the relationship between health contexts and the interventions required to improve management and leadership competence, will be examined. This will help guide the applicability of the findings of the review to other health settings not identified by the included studies. If possible, any relationship between management levels and effectiveness of interventions will also be investigated. The outcome of this systematic review will be an understanding of the evidence for the relationship between training and professional development interventions and improved health management and leadership competence.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Vanessa Jordan of the University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand for reviewing the methods section of the protocol.

Ethical issues

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The protocol was conceived by ROA and NN. Both authors contributed to the development of the protocol. ROA wrote the draft copy and final version of the manuscript. NN, KAW, ZL, and AD commented on the draft copy and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ affiliations

1 Health Systems Section, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. 2 Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand. 3 Department of Public Health, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

Search Sources

The following electronic databases and catalogues will be searched:

- Cochrane databases of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

- Current contents

- Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects (DARE)

- Database of Public Health Effectiveness Reviews (DOPHER)

- Health Promis (Database of the Health Development Agency)

- Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

- Health Services Technology Assessment Texts (HSTAT)

- Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS)

- ScienceDirect

- System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe Archive (SIGLE)

- Trials Register of Public Health Interventions (TROPHI)

Citation: Ayeleke RO, North N, Wallis KA, Liang Z, Dunham A. Outcomes and impact of training and development in health management and leadership in relation to competence in role: a mixed-methods systematic review protocol. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(12):715–720. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2016.138

Systematic Literature Review of E-Learning Capabilities to Enhance Organizational Learning

- Open access

- Published: 01 February 2021

- Volume 24 , pages 619–635, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michail N. Giannakos 1 ,

- Patrick Mikalef 1 &

- Ilias O. Pappas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7528-3488 1 , 2

21k Accesses

32 Citations

Explore all metrics

E-learning systems are receiving ever increasing attention in academia, business and public administration. Major crises, like the pandemic, highlight the tremendous importance of the appropriate development of e-learning systems and its adoption and processes in organizations. Managers and employees who need efficient forms of training and learning flow within organizations do not have to gather in one place at the same time or to travel far away to attend courses. Contemporary affordances of e-learning systems allow users to perform different jobs or tasks for training courses according to their own scheduling, as well as to collaborate and share knowledge and experiences that result in rich learning flows within organizations. The purpose of this article is to provide a systematic review of empirical studies at the intersection of e-learning and organizational learning in order to summarize the current findings and guide future research. Forty-seven peer-reviewed articles were collected from a systematic literature search and analyzed based on a categorization of their main elements. This survey identifies five major directions of the research on the confluence of e-learning and organizational learning during the last decade. Future research should leverage big data produced from the platforms and investigate how the incorporation of advanced learning technologies (e.g., learning analytics, personalized learning) can help increase organizational value.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)?

Exploring Human Resource Management Digital Transformation in the Digital Age

Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

E-learning covers the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) in environments with the main goal of fostering learning (Rosenberg and Foshay 2002 ). The term “e-learning” is often used as an umbrella term to portray several modes of digital learning environments (e.g., online, virtual learning environments, social learning technologies). Digitalization seems to challenge numerous business models in organizations and raises important questions about the meaning and practice of learning and development (Dignen and Burmeister 2020 ). Among other things, the digitalization of resources and processes enables flexible ways to foster learning across an organization’s different sections and personnel.

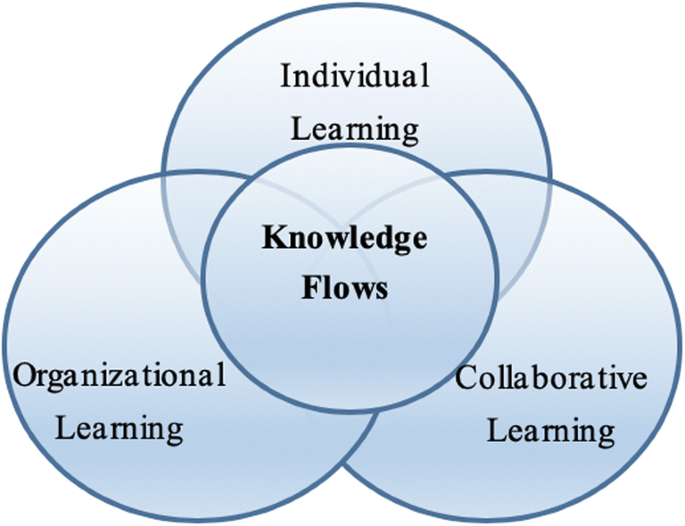

Learning has long been associated with formal or informal education and training. However organizational learning is much more than that. It can be defined as “a learning process within organizations that involves the interaction of individual and collective (group, organizational, and inter-organizational) levels of analysis and leads to achieving organizations’ goals” (Popova-Nowak and Cseh 2015 ) with a focus on the flow of knowledge across the different organizational levels (Oh 2019 ). Flow of knowledge or learning flow is the way in which new knowledge flows from the individual to the organizational level (i.e., feed forward) and vice versa (i.e., feedback) (Crossan et al. 1999 ; March 1991 ). Learning flow and the respective processes constitute the cornerstone of an organization’s learning activities (e.g., from physical training meetings to digital learning resources), they are directly connected to the psycho-social experiences of an organization’s members, and they eventually lead to organizational change (Crossan et al. 2011 ). The overall organizational learning is extremely important in an organization because it is associated with the process of creating value from an organizations’ intangible assets. Moreover, it combines notions from several different domains, such as organizational behavior, human resource management, artificial intelligence, and information technology (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ).

A growing body of literature lies at the intersection of e-learning and organizational learning. However, there is limited work on the qualities of e-learning and the potential of its qualities to enhance organizational learning (Popova-Nowak and Cseh 2015 ). Blockages and disruptions in the internal flow of knowledge is a major reason why organizational change initiatives often fail to produce their intended results (Dee and Leisyte 2017 ). In recent years, several models of organizational learning have been published (Berends and Lammers 2010 ; Oh 2019 ). However, detailed empirical studies indicate that learning does not always proceed smoothly in organizations; rather, the learning meets interruptions and breakdowns (Engeström et al. 2007 ).

Discontinuities and disruptions are common phenomena in organizational learning (Berends and Lammers 2010 ), and they stem from various causes. For example, organizational members’ low self-esteem, unsupportive technology and instructors (Garavan et al. 2019 ), and even crises like the Covid-19 pandemic can result in demotivated learners and overall unwanted consequences for their learning (Broadbent 2017 ). In a recent conceptual article, Popova-Nowak and Cseh ( 2015 ) emphasized that there is a limited use of multidisciplinary perspectives to investigate and explain the processes and importance of utilizing the available capabilities and resources and of creating contexts where learning is “attractive to individual agents so that they can be more engaged in exploring ways in which they can contribute through their learning to the ongoing renewal of organizational routines and practices” (Antonacopoulou and Chiva 2007 , p. 289).

Despite the importance of e-learning, the lack of systematic reviews in this area significantly hinders research on the highly promising value of e-learning capabilities for efficiently supporting organizational learning. This gap leaves practitioners and researchers in uncharted territories when faced with the task of implementing e-learning designs or deciding on their digital learning strategies to enhance the learning flow of their organizations. Hence, in order to derive meaningful theoretical and practical implications, as well as to identify important areas for future research, it is critical to understand how the core capabilities pertinent to e-learning possess the capacity to enhance organizational learning.

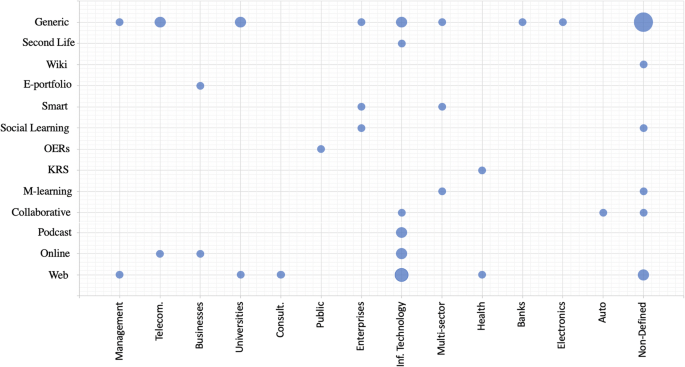

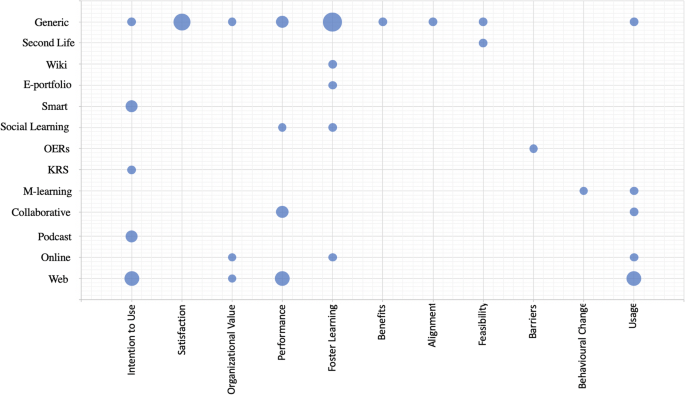

In this paper, we define e-learning enhanced organizational learning (eOL) as the utilization of digital technologies to enhance the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding in an organization. In recent years, a significant body of research has focused on the intersection of e-learning and organizational learning (e.g., Khandakar and Pangil 2019 ; Lin et al. 2019 ; Menolli et al. 2020 ; Turi et al. 2019 ; Xiang et al. 2020 ). However, there is a lack of systematic work that summarizes and conceptualizes the results in order to support organizations that want to move from being information-based enterprises to being knowledge-based ones (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ). In particular, recent technological advances have led to an increase in research that leverages e-learning capacities to support organizational learning, from virtual reality (VR) environments (Costello and McNaughton 2018 ; Muller Queiroz et al. 2018 ) to mobile computing applications (Renner et al. 2020 ) to adaptive learning and learning analytics (Zhang et al. 2019 ). These studies support different skills, consider different industries and organizations, and utilize various capacities while focusing on various learning objectives (Garavan et al. 2019 ). Our literature review aims to tease apart these particularities and to investigate how these elements have been utilized over the past decade in eOL research. Therefore, in this review we aim to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What is the status of research at the intersection of e-learning and organizational learning, seen through the lens of areas of implementation (e.g., industries, public sector), technologies used, and methodologies (e.g., types of data and data analysis techniques employed)?

RQ2: How can e-learning be leveraged to enhance the process of improving actions through better knowledge and understanding in an organization?

Our motivation for this work is based on the emerging developments in the area of learning technologies that have created momentum for their adoption by organizations. This paper provides a review of research on e-learning capabilities to enhance organizational learning with the purpose of summarizing the findings and guiding future studies. This study can provide a springboard for other scholars and practitioners, especially in the area of knowledge-based enterprises, to examine e-learning approaches by taking into consideration the prior and ongoing research efforts. Therefore, in this paper we present a systematic literature review (SLR) (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ) on the confluence of e-learning and organizational learning that uncovers initial findings on the value of e-learning to support organizational learning while also delineating several promising research streams.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we present the related background work. The third section describes the methodology used for the literature review and how the studies were selected and analyzed. The fourth section presents the research findings derived from the data analysis based on the specific areas of focus. In the fifth section, we discuss the findings, the implications for practice and research, and the limitations of the selected methodological approach. In the final section, we summarize the conclusions from the study and make suggestions for future work.

2 Background and Related Work

2.1 e-learning systems.

E-learning systems provide solutions that deliver knowledge and information, facilitate learning, and increase performance by developing appropriate knowledge flow inside organizations (Menolli et al. 2020 ). Putting into practice and appropriately managing technological solutions, processes, and resources are necessary for the efficient utilization of e-learning in an organization (Alharthi et al. 2019 ). Examples of e-learning systems that have been widely adopted by various organizations are Canvas, Blackboard, and Moodle. Such systems provide innovative services for students, employees, managers, instructors, institutions, and other actors to support and enhance the learning processes and facilitate efficient knowledge flow (Garavan et al. 2019 ). Functionalities, such as creating modules to organize mini course information and learning materials or communication channels such as chat, forums, and video exchange, allow instructors and managers to develop appropriate training and knowledge exchange (Wang et al. 2011 ). Nowadays, the utilization of various e-learning capabilities is a commodity for supporting organizational and workplace learning. Such learning refers to training or knowledge development (also known in the literature as learning and development, HR development, and corporate training: Smith and Sadler-Smith 2006 ; Garavan et al. 2019 ) that takes place in the context of work.

Previous studies have focused on evaluating e-learning systems that utilize various models and frameworks. In particular, the development of maturity models, such as the e-learning capability maturity model (eLCMM), addresses technology-oriented concerns (Hammad et al. 2017 ) by overcoming the limitations of the domain-specific models (e.g., game-based learning: Serrano et al. 2012 ) or more generic lenses such as the e-learning maturity model (Marshall 2006 ). The aforementioned models are very relevant since they focus on assessing the organizational capabilities for sustainably developing, deploying, and maintaining e-learning. In particular, the eLCMM focuses on assessing the maturity of adopting e-learning systems and adds a feedback building block for improving learners’ experiences (Hammad et al. 2017 ). Our proposed literature review builds on the previously discussed models, lenses, and empirical studies, and it provides a review of research on e-learning capabilities with the aim of enhancing organizational learning in order to complement the findings of the established models and guide future studies.

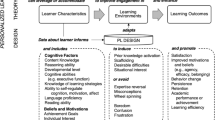

E-learning systems can be categorized into different types, depending on their functionalities and affordances. One very popular e-learning type is the learning management system (LMS), which includes a virtual classroom and collaboration capabilities and allows the instructor to design and orchestrate a course or a module. An LMS can be either proprietary (e.g., Blackboard) or open source (e.g., Moodle). These two types differ in their features, costs, and the services they provide; for example, proprietary systems prioritize assessment tools for instructors, whereas open-source systems focus more on community development and engagement tools (Alharthi et al. 2019 ). In addition to LMS, e-learning systems can be categorized based on who controls the pace of learning; for example, an institutional learning environment (ILE) is provided by the organization and is usually used for instructor-led courses, while a personal learning environment (PLE) is proposed by the organization and is managed personally (i.e., learner-led courses). Many e-learning systems use a hybrid version of ILE and PLE that allows organizations to have either instructor-led or self-paced courses.

Besides the controlled e-learning systems, organizations have been using environments such as social media (Qi and Chau 2016 ), massive open online courses (MOOCs) (Weinhardt and Sitzmann 2018 ) and other web-based environments (Wang et al. 2011 ) to reinforce their organizational learning potential. These systems have been utilized through different types of technology (e.g., desktop applications, mobile) that leverage the various capabilities offered (e.g., social learning, VR, collaborative systems, smart and intelligent support) to reinforce the learning and knowledge flow potential of the organization. Although there is a growing body of research on e-learning systems for organizational learning due to the increasingly significant role of skills and expertise development in organizations, the role and alignment of the capabilities of the various e-learning systems with the expected competency development remains underexplored.

2.2 Organizational Learning

There is a large body of research on the utilization of technologies to improve the process and outcome dimensions of organizational learning (Crossan et al. 1999 ). Most studies have focused on the learning process and on the added value that new technologies can offer by replacing some of the face-to-face processes with virtual processes or by offering new, technology-mediated phases to the process (Menolli et al. 2020 ; Lau 2015 ) highlighted how VR capabilities can enhance organizational learning, describing the new challenges and frameworks needed in order to effectively utilize this potential. In the same vein, Zhang et al. ( 2017 ) described how VR influences reflective thinking and considered its indirect value to overall learning effectiveness. In general, contemporary research has investigated how novel technologies and approaches have been utilized to enhance organizational learning, and it has highlighted both the promises and the limitations of the use of different technologies within organizations.

In many organizations, alignment with the established infrastructure and routines, and adoption by employees are core elements for effective organizational learning (Wang et al. 2011 ). Strict policies, low digital competence, and operational challenges are some of the elements that hinder e-learning adoption by organizations (Garavan et al. 2019 ; Wang 2018 ) demonstrated the importance of organizational, managerial, and job support for utilizing individual and social learning in order to increase the adoption of organizational learning. Other studies have focused on the importance of communication through different social channels to develop understanding of new technology, to overcome the challenges employees face when engaging with new technology, and, thereby, to support organizational learning (Menolli et al. 2020 ). By considering the related work in the area of organizational learning, we identified a gap in aligning an organization’s learning needs with the capabilities offered by the various technologies. Thus, systematic work is needed to review e-learning capabilities and how these capabilities can efficiently support organizational learning.

2.3 E-learning Systems to Enhance Organizational Learning

When considering the interplay between e-learning systems and organizational learning, we observed that a major challenge for today’s organizations is to switch from being information-based enterprises to become knowledge-based enterprises (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ). Unidirectional learning flows, such as formal and informal training, are important but not sufficient to cover the needs that enterprises face (Manuti et al. 2015 ). To maintain enterprises’ competitiveness, enterprise staff have to operate in highly intense information and knowledge-oriented environments. Traditional learning approaches fail to substantiate learning flow on the basis of daily evidence and experience. Thus, novel, ubiquitous, and flexible learning mechanisms are needed, placing humans (e.g., employees, managers, civil servants) at the center of the information and learning flow and bridging traditional learning with experiential, social, and smart learning.

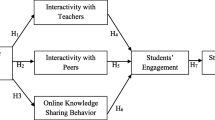

Organizations consider lack of skills and competences as being the major knowledge-related factors hampering innovation (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ). Thus, solutions need to be implemented that support informal, day-to-day, and work training (e.g., social learning, collaborative learning, VR/AR solutions) in order to develop individual staff competences and to upgrade the competence affordances at the organizational level. E-learning-enhanced organizational learning has been delivered primarily in the form of web-based learning (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ). More recently, the TEL tools portfolio has rapidly expanded to make more efficient joint use of novel learning concepts, methodologies, and technological enablers to achieve more direct, effective, and lasting learning impacts. Virtual learning environments, mobile-learning solutions, and AR/VR technologies and head-mounted displays have been employed so that trainees are empowered to follow their own training pace, learning topics, and assessment tests that fit their needs (Costello and McNaughton 2018 ; Mueller et al. 2011 ; Muller Queiroz et al. 2018 ). The expanding use of social networking tools has also brought attention to the contribution of social and collaborative learning (Hester et al. 2016 ; Wei and Ram 2016 ).

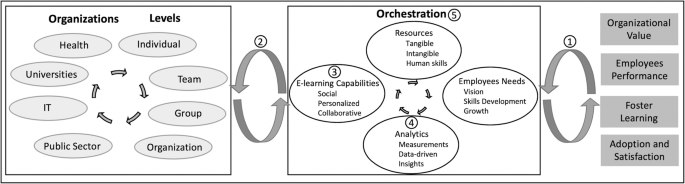

Contemporary learning systems supporting adaptive, personalized, and collaborative learning expand the tools available in eOL and contribute to the adoption, efficiency, and general prospects of the introduction of TEL in organizations (Cheng et al. 2011 ). In recent years, eOL has emphasized how enterprises share knowledge internally and externally, with particular attention being paid to systems that leverage collaborative learning and social learning functionalities (Qi and Chau 2016 ; Wang 2011 ). This is the essence of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL). The CSCL literature has developed a framework that combines individual learning, organizational learning, and collaborative learning, facilitated by establishing adequate learning flows and emerges effective learning in an enterprise learning (Goggins et al. 2013 ), in Fig. 1 .

Representation of the combination of enterprise learning and knowledge flows. (adapted from Goggins et al. 2013 )

Establishing efficient knowledge and learning flows is a primary target for future data-driven enterprises (El Kadiri et al. 2016 ). Given the involved knowledge, the human resources, and the skills required by enterprises, there is a clear need for continuous, flexible, and efficient learning. This can be met by contemporary learning systems and practices that provide high adoption, smooth usage, high satisfaction, and close alignment with the current practices of an enterprise. Because the required competences of an enterprise evolve, the development of competence models needs to be agile and to leverage state-of-the art technologies that align with the organization’s processes and models. Therefore, in this paper we provide a review of the eOL research in order to summarize the findings, identify the various capabilities of eOL, and guide the development of organizational learning in future enterprises as well as in future studies.

3 Methodology

To answer our research questions, we conducted an SLR, which is a means of evaluating and interpreting all available research relevant to a particular research question, topic area, or phenomenon of interest. A SLR has the capacity to present a fair evaluation of a research topic by using a trustworthy, rigorous, and auditable methodology (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). The guidelines used (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ) were derived from three existing guides adopted by medical researchers. Therefore, we adopted SLR guidelines that follow transparent and widely accepted procedures (especially in the area of software engineering and information systems, as well as in e-learning), minimize potential bias (researchers), and support reproducibility (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ). Besides the minimization of bias and support for reproducibility, an SLR allows us to provide information about the impact of some phenomenon across a wide range of settings, contexts, and empirical methods. Another important advantage is that, if the selected studies give consistent results, SLRs can provide evidence that the phenomenon is robust and transferable (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ).

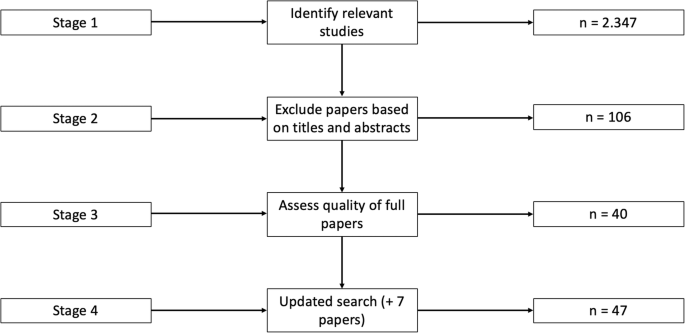

3.1 Article Collection

Several procedures were followed to ensure a high-quality review of the literature of eOL. A comprehensive search of peer-reviewed articles was conducted in February 2019 (short papers, posters, dissertations, and reports were excluded), based on a relatively inclusive range of key terms: “organizational learning” & “elearning”, “organizational learning” & “e-learning”, “organisational learning” & “elearning”, and “organisational learning” & “e-learning”. Publications were selected from 2010 onwards, because we identified significant advances since 2010 (e.g., MOOCs, learning analytics, personalized learning) in the area of learning technologies. A wide variety of databases were searched, including SpringerLink, Wiley, ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, Science Direct, SAGE, ERIC, AIS eLibrary, and Taylor & Francis. The selected databases were aligned with the SLR guidelines (Kitchenham and Charters 2007 ) and covered the major venues in IS and educational technology (e.g., a basket of eight IS journals, the top 20 journals in the Google Scholar IS subdiscipline, and the top 20 journals in the Google Scholar Educational Technology subdiscipline). The search process uncovered 2,347 peer-reviewed articles.

3.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection phase determines the overall validity of the literature review, and thus it is important to define specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. As Dybå and Dingsøyr ( 2008 ) specified, the quality criteria should cover three main issues – namely, rigor, credibility, and relevance – that need to be considered when evaluating the quality of the selected studies. We applied eight quality criteria informed by the proposed Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) and related works (Dybå and Dingsøyr 2008 ). Table 1 presents these criteria.

Therefore, studies were eligible for inclusion if they were focused on eOL. The aforementioned criteria were applied in stages 2 and 3 of the selection process (see Fig. 2 ), when we assessed the papers based on their titles and abstracts, and read the full papers. From March 2020, we performed an additional search (stage 4) following the same process for papers published after the initial search period (i.e., 2010–February 2019). The additional search returned seven papers. Figure 2 summarizes the stages of the selection process.

Stages of the selection process

3.3 Analysis