- En español – ExME

- Em português – EME

Traditional reviews vs. systematic reviews

Posted on 3rd February 2016 by Weyinmi Demeyin

Millions of articles are published yearly (1) , making it difficult for clinicians to keep abreast of the literature. Reviews of literature are necessary in order to provide clinicians with accurate, up to date information to ensure appropriate management of their patients. Reviews usually involve summaries and synthesis of primary research findings on a particular topic of interest and can be grouped into 2 main categories; the ‘traditional’ review and the ‘systematic’ review with major differences between them.

Traditional reviews provide a broad overview of a research topic with no clear methodological approach (2) . Information is collected and interpreted unsystematically with subjective summaries of findings. Authors aim to describe and discuss the literature from a contextual or theoretical point of view. Although the reviews may be conducted by topic experts, due to preconceived ideas or conclusions, they could be subject to bias.

Systematic reviews are overviews of the literature undertaken by identifying, critically appraising and synthesising results of primary research studies using an explicit, methodological approach(3). They aim to summarise the best available evidence on a particular research topic.

The main differences between traditional reviews and systematic reviews are summarised below in terms of the following characteristics: Authors, Study protocol, Research question, Search strategy, Sources of literature, Selection criteria, Critical appraisal, Synthesis, Conclusions, Reproducibility, and Update.

Traditional reviews

- Authors: One or more authors usually experts in the topic of interest

- Study protocol: No study protocol

- Research question: Broad to specific question, hypothesis not stated

- Search strategy: No detailed search strategy, search is probably conducted using keywords

- Sources of literature: Not usually stated and non-exhaustive, usually well-known articles. Prone to publication bias

- Selection criteria: No specific selection criteria, usually subjective. Prone to selection bias

- Critical appraisal: Variable evaluation of study quality or method

- Synthesis: Often qualitative synthesis of evidence

- Conclusions: Sometimes evidence based but can be influenced by author’s personal belief

- Reproducibility: Findings cannot be reproduced independently as conclusions may be subjective

- Update: Cannot be continuously updated

Systematic reviews

- Authors: Two or more authors are involved in good quality systematic reviews, may comprise experts in the different stages of the review

- Study protocol: Written study protocol which includes details of the methods to be used

- Research question: Specific question which may have all or some of PICO components (Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome). Hypothesis is stated

- Search strategy: Detailed and comprehensive search strategy is developed

- Sources of literature: List of databases, websites and other sources of included studies are listed. Both published and unpublished literature are considered

- Selection criteria: Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Critical appraisal: Rigorous appraisal of study quality

- Synthesis: Narrative, quantitative or qualitative synthesis

- Conclusions: Conclusions drawn are evidence based

- Reproducibility: Accurate documentation of method means results can be reproduced

- Update: Systematic reviews can be periodically updated to include new evidence

Decisions and health policies about patient care should be evidence based in order to provide the best treatment for patients. Systematic reviews provide a means of systematically identifying and synthesising the evidence, making it easier for policy makers and practitioners to assess such relevant information and hopefully improve patient outcomes.

- Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. Evidence-Based Approach to the Medical Literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997; 12(Suppl 2):S5-S14. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.12.s2.1.x. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1497222/

- Rother ET. Systematic literature review X narrative review. Acta paul. enferm. [Internet]. 2007 June [cited 2015 Dec 25]; 20(2): v-vi. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-21002007000200001&lng=en. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21002007000200001

- Khan KS, Ter Riet G, Glanville J, Sowden AJ, Kleijnen J. Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for carrying out or commissioning reviews. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; 2001.

Weyinmi Demeyin

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments on Traditional reviews vs. systematic reviews

THE INFORMATION IS VERY MUCH VALUABLE, A LOT IS INDEED EXPECTED IN ORDER TO MASTER SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Thank you very much for the information here. My question is : Is it possible for me to do a systematic review which is not directed toward patients but just a specific population? To be specific can I do a systematic review on the mental health needs of students?

Hi Rosemary, I wonder whether it would be useful for you to look at Module 1 of the Cochrane Interactive Learning modules. This is a free module, open to everyone (you will just need to register for a Cochrane account if you don’t already have one). This guides you through conducting a systematic review, with a section specifically around defining your research question, which I feel will help you in understanding your question further. Head to this link for more details: https://training.cochrane.org/interactivelearning

I wonder if you have had a search on the Cochrane Library as yet, to see what Cochrane systematic reviews already exist? There is one review, titled “Psychological interventions to foster resilience in healthcare students” which may be of interest: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD013684/full You can run searches on the library by the population and intervention you are interested in.

I hope these help you start in your investigations. Best wishes. Emma.

La revisión sistemática vale si hay solo un autor?

HI Alex, so sorry for the delay in replying to you. Yes, that is a very good point. I have copied a paragraph from the Cochrane Handbook, here, which does say that for a Cochrane Review, you should have more than one author.

“Cochrane Reviews should be undertaken by more than one person. In putting together a team, authors should consider the need for clinical and methodological expertise for the review, as well as the perspectives of stakeholders. Cochrane author teams are encouraged to seek and incorporate the views of users, including consumers, clinicians and those from varying regions and settings to develop protocols and reviews. Author teams for reviews relevant to particular settings (e.g. neglected tropical diseases) should involve contributors experienced in those settings”.

Thank you for the discussion point, much appreciated.

Hello, I’d like to ask you a question: what’s the difference between systematic review and systematized review? In addition, if the screening process of the review was made by only one author, is still a systematic or is a systematized review? Thanks

Hi. This article from Grant & Booth is a really good one to look at explaining different types of reviews: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x It includes Systematic Reviews and Systematized Reviews. In answer to your second question, have a look at this Chapter from the Cochrane handbook. It covers the question about ‘Who should do a systematic review’. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-01

A really relevant part of this chapter is this: “Systematic reviews should be undertaken by a team. Indeed, Cochrane will not publish a review that is proposed to be undertaken by a single person. Working as a team not only spreads the effort, but ensures that tasks such as the selection of studies for eligibility, data extraction and rating the certainty of the evidence will be performed by at least two people independently, minimizing the likelihood of errors.”

I hope this helps with the question. Best wishes. Emma.

Subscribe to our newsletter

You will receive our monthly newsletter and free access to Trip Premium.

Related Articles

What do trialists do about participants who are ‘lost to follow-up’?

Participants in clinical trials may exit the study prior to having their results collated; in this case, what do we do with their results?

Family Therapy approaches for Anorexia Nervosa

Is Family Therapy effective in the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa? Emily summarises a recent Cochrane Review in this blog and examines the evidence.

Antihypertensive drugs for primary prevention – at what blood pressure do we start treatment?

In this blog, Giorgio Karam examines the evidence on antihypertensive drugs for primary prevention – when do we start treatment?

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

- 3 minute read

- 51.5K views

Table of Contents

As a researcher, you may be required to conduct a literature review. But what kind of review do you need to complete? Is it a systematic literature review or a standard literature review? In this article, we’ll outline the purpose of a systematic literature review, the difference between literature review and systematic review, and other important aspects of systematic literature reviews.

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

The purpose of systematic literature reviews is simple. Essentially, it is to provide a high-level of a particular research question. This question, in and of itself, is highly focused to match the review of the literature related to the topic at hand. For example, a focused question related to medical or clinical outcomes.

The components of a systematic literature review are quite different from the standard literature review research theses that most of us are used to (more on this below). And because of the specificity of the research question, typically a systematic literature review involves more than one primary author. There’s more work related to a systematic literature review, so it makes sense to divide the work among two or three (or even more) researchers.

Your systematic literature review will follow very clear and defined protocols that are decided on prior to any review. This involves extensive planning, and a deliberately designed search strategy that is in tune with the specific research question. Every aspect of a systematic literature review, including the research protocols, which databases are used, and dates of each search, must be transparent so that other researchers can be assured that the systematic literature review is comprehensive and focused.

Most systematic literature reviews originated in the world of medicine science. Now, they also include any evidence-based research questions. In addition to the focus and transparency of these types of reviews, additional aspects of a quality systematic literature review includes:

- Clear and concise review and summary

- Comprehensive coverage of the topic

- Accessibility and equality of the research reviewed

Systematic Review vs Literature Review

The difference between literature review and systematic review comes back to the initial research question. Whereas the systematic review is very specific and focused, the standard literature review is much more general. The components of a literature review, for example, are similar to any other research paper. That is, it includes an introduction, description of the methods used, a discussion and conclusion, as well as a reference list or bibliography.

A systematic review, however, includes entirely different components that reflect the specificity of its research question, and the requirement for transparency and inclusion. For instance, the systematic review will include:

- Eligibility criteria for included research

- A description of the systematic research search strategy

- An assessment of the validity of reviewed research

- Interpretations of the results of research included in the review

As you can see, contrary to the general overview or summary of a topic, the systematic literature review includes much more detail and work to compile than a standard literature review. Indeed, it can take years to conduct and write a systematic literature review. But the information that practitioners and other researchers can glean from a systematic literature review is, by its very nature, exceptionally valuable.

This is not to diminish the value of the standard literature review. The importance of literature reviews in research writing is discussed in this article . It’s just that the two types of research reviews answer different questions, and, therefore, have different purposes and roles in the world of research and evidence-based writing.

Systematic Literature Review vs Meta Analysis

It would be understandable to think that a systematic literature review is similar to a meta analysis. But, whereas a systematic review can include several research studies to answer a specific question, typically a meta analysis includes a comparison of different studies to suss out any inconsistencies or discrepancies. For more about this topic, check out Systematic Review VS Meta-Analysis article.

Language Editing Plus

With Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus services , you can relax with our complete language review of your systematic literature review or literature review, or any other type of manuscript or scientific presentation. Our editors are PhD or PhD candidates, who are native-English speakers. Language Editing Plus includes checking the logic and flow of your manuscript, reference checks, formatting in accordance to your chosen journal and even a custom cover letter. Our most comprehensive editing package, Language Editing Plus also includes any English-editing needs for up to 180 days.

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

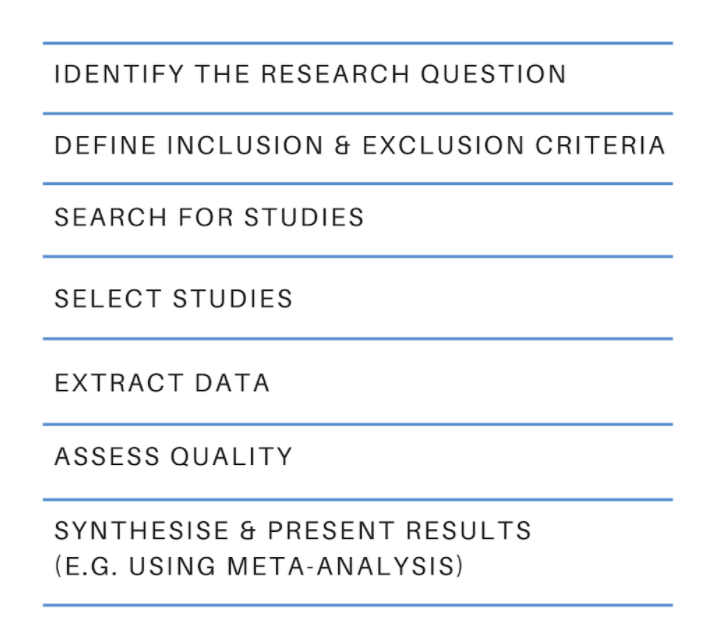

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved July 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Literature Review: Traditional or narrative literature reviews

Traditional or narrative literature reviews.

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic literature reviews

- Annotated bibliography

- Keeping up to date with literature

- Finding a thesis

- Evaluating sources and critical appraisal of literature

- Managing and analysing your literature

- Further reading and resources

A narrative or traditional literature review is a comprehensive, critical and objective analysis of the current knowledge on a topic. They are an essential part of the research process and help to establish a theoretical framework and focus or context for your research. A literature review will help you to identify patterns and trends in the literature so that you can identify gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge. This should lead you to a sufficiently focused research question that justifies your research.

Onwuegbuzie and Frels (pp 24-25, 2016) define four common types of narrative reviews:

- General literature review that provides a review of the most important and critical aspects of the current knowledge of the topic. This general literature review forms the introduction to a thesis or dissertation and must be defined by the research objective, underlying hypothesis or problem or the reviewer's argumentative thesis.

- Theoretical literature review which examines how theory shapes or frames research

- Methodological literature review where the research methods and design are described. These methodological reviews outline the strengths and weaknesses of the methods used and provide future direction

- Historical literature review which focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

References and additional resources

Baker, J. D. (2016) The purpose, process and methods of writing a literature review: Editorial . Association of Operating Room Nurses. AORN Journal, 103 (3), 265-269. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2016.01.016

- << Previous: Types of literature reviews

- Next: Scoping Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:25 AM

- URL: https://libguides.csu.edu.au/review

Charles Sturt University is an Australian University, TEQSA Provider Identification: PRV12018. CRICOS Provider: 00005F.

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 2:02 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Types of Literature Reviews : Home

- Health Science Information Consortium

- University Health Network - New

- Types of Literature Reviews

Need More Help?

- Knowledge Synthesis Support

- Literature Search Request

- The Right Review for You - Workshop Recording (YouTube) 27min video From UHN Libraries Recorded Nov 2021

- The Screening Phase for Reviews Tutorial This tutorial presents information on the screening process for systematic reviews or other knowledge syntheses, and contains a variety of resources for successfully preparing to complete this important research stage.

- Workshops Find more UHN Libraries workshops, live and on-demand, and other learning opportunities helpful for knowledge synthesis projects.

How to Choose Your Review Method

TREAD* Lightly and Consider...

- Available T ime for conducting your review

- Any R esource constraints within which you must deliver your review

- Any requirements for specialist E xpertise in order to complete the review

- The requirements of the A udience for your review and its intended purpose

- The richness, thickness and availability of D ata within included studies

* Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 2nd edition. Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016. (p.36)

How do I write a Review Protocol?

- What is a Protocol? (UofT)

- Guidance on Registering a Review with PROSPERO

Writing Resources

- Advice on Academic Writing (University of Toronto)

- How to write a great research paper using reporting guidelines (EQUATOR Network)

- Instructions to Authors in the Health Sciences

- Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly work in Medical Journals (ICMJE)

- Writing resources guide (BMC)

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review provides an overview of what's been written about a specific topic. It is a generic term. There are many different types of literature reviews which can cover a wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. Choosing the type of review you wish to conduct will depend on the purpose of your review, and the time and resources you have available.

This page will provide definitions of some of the most common review types in the health sciences and links to relevant reporting guidelines or methodological papers.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies . Health Information & Libraries Journal . 2009 Jun 1;26(2):91-108.

- Summary of Five Types of Reviews Table summarizing the characteristics, guidelines etc. of 5 common types of review article.

Traditional (Narrative) Review

Traditional (narrative) literature reviews provide a broad overview of a research topic with no clear methodological approach. Information is collected and interpreted unsystematically with subjective summaries of findings. Authors aim to describe and discuss the literature from a contextual or theoretical point of view. Although the reviews may be conducted by topic experts, due to preconceived ideas or conclusions, they could be subject to bias. This sort of literature review can be appropriate if you have a broad topic area, are working on your own, or have time constraints.

Agarwal S, Charlesworth M, Elrakhawy M. How to write a narrative review . Anaesthesia . 2023;78(9):1162-1166. doi:10.1111/anae.16016

Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade . Journal of Chiropractic Medicine . 2006;5(3):101-117. doi:10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6.

Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews . Medical Writing. 2015 Dec 1;24(4):230-5.

Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews ? European journal of clinical investigation . 2018;48:e12931.

Knowledge Synthesis

- What is Knowledge Synthesis?

- Learn more!

CIHR Definition of Knowledge Syntheses:

“The contextualization and integration of research findings of individual research studies within the larger body of knowledge on the topic. A synthesis must be reproducible and transparent in its methods, using quantitative and/or qualitative methods.” - A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis, CIHR

Grimshaw J. A Guide to Knowledge Synthesis [Internet]. CIHR. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2010.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Synthesis Resources [Internet]. CIHR. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2013.

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt, Gert Jan, et al. Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches . Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2018;99:41-52.

Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review . BMC Medical Research Methodology . 2012;12:114. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-114.

Kastner M, Antony J, Soobiah C, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology . 2016;73:43-49.

Knowledge Synthesis Support at UHN

Common Types of Knowledge Syntheses

- Systematic Reviews

- Meta-Analysis

- Scoping Reviews

- Rapid or Restricted Reviews

- Clinical Practice Guidelines

- Realist Reviews

- Mixed Methods Reviews

- Qualitative Synthesis

- Narrative Synthesis

A systematic review attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a given research question. Researchers conducting systematic reviews use explicit methods aimed at minimizing bias, in order to produce more reliable findings that can be used to inform decision making. (See Section 1.2 in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions .)

A systematic review is not the same as a traditional (narrative) review or a literature review. Unlike other kinds of reviews, systematic reviews must be as thorough and unbiased as possible, and must also make explicit how the search was conducted. Systematic reviews may or may not include a meta-analysis.

On average, a systematic review project takes a year. If your timelines are shorter, you may wish to consider other types of synthesis projects or a traditional (narrative) review. See suggested timelines for a Cochrane Review for reference.

Systematic Review Overview (UHN)

Systematic Review Overview workshop recording (UHN)

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

Greyson D, Rafferty E, Slater L, et al. Systematic review searches must be systematic, comprehensive, and transparent: a critique of Perman et al. BMC public health . 2019;19:153.

Ioannidis J. P. (2016). The Mass Production of Redundant, Misleading, and Conflicted Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses . The Milbank quarterly , 94 (3), 485-514.

A subset of systematic reviews. Meta-analysis is a technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results.

"..a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence, and gaps in research related to a defined area or field by systematically searching, selecting and synthesizing existing knowledge." (Colquhoun, HL et al., 2014)

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework . International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice , 8 (1), 19-32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. & O'Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology . Implementation Sci 5 , 69 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O'Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., . . . Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology , 67(12), 1291-1294. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews . Int.J.Evid Based.Healthc . 2015 Sep;13(3):141-146.

Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis , JBI, 2020.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation . Ann Intern Med . [Epub ahead of print ] doi: 10.7326/M18-0850.

“…a type of knowledge synthesis in which systematic review processes are accelerated and methods are streamlined to complete the review more quickly than is the case for typical systematic reviews. Rapid reviews take an average of 5–12 weeks to complete, thus providing evidence within a shorter time frame required for some health policy and systems decisions.” (Tricco AC et al., 2017)

Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews . Implementation Science : IS . 2010;5:56. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-56.

Langlois EV, Straus SE, Antony J, King VJ, Tricco AC. Using rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems and progress towards universal health coverage . BMJ Global Health . 2019;4:e001178.

Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE, editors. Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Watt A, Cameron A, Sturm L, Lathlean T , Babidge W, Blamey S, et al. Rapid reviews versus full systematic reviews: An inventory of current methods and practice in health technology assessment . International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care . 2008;24(2):133-9.

“Clinical practice guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.” Source: Institute of Medicine. (1990). Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program, M.J. Field and K.N. Lohr (eds.) Washington, DC: National Academy Press. Page 38.

–Disclosure of any author conflicts of interest

AGREE Reporting Checklist

Alonso-Coello, P., Oxman, A. D., Moberg, J., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Akl, E. A., Davoli, M., ... & Guyatt, G. H. (2016). GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines . BMJ , 353 , i2089.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review - a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions . Journal of Health Services Research & Policy . 2005;10:21-34.

Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research . Implementation science : IS . 2012;7:33.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Medical Education . 2012;46(1):89-96.

"Mixed-methods systematic reviews can be defined as combining the findings of qualitative and quantitative studies within a single systematic review to address the same overlapping or complementary review questions." (Harden A, 2010)

Harden A. Mixed-Methods Systematic Reviews: Integrating quantitative and qualitative findings . NCDDR:FOCUS. 2010.

Lizarondo L, Stern C, Apostolo J, et al. Five common pitfalls in mixed methods systematic reviews: lessons learned . J Clin Epidemiol . 2022;148:178-183. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.03.014

Pluye P, Hong QN. Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews . Annual review of public health . 2014;35:29-45.

Pearson A, White H, Bath-Hextall F, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P. A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews . International journal of evidence-based healthcare . 2015;13:121-131.

The Joanna Briggs Institute 2014 Reviewers Manual: Methodology for JBI Mixed Methods Systematic Reviews .

There are various methods for integrating the results from qualitative studies. "Systematic reviews of qualitative research have an important role in informing the delivery of evidence-based healthcare. Qualitative systematic reviews have investigated the culture of communities, exploring how consumers experience, perceive and manage their health and journey through the health system, and can evaluate components and activities of health services such as health promotion and community development." (Lockwood C et al., 2015)

Booth A, Noyes J, Flemming K, Gerhardus A, Wahlster P, van der Wilt, Gert Jan, et al. Structured methodology review identified seven (RETREAT) criteria for selecting qualitative evidence synthesis approaches . Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2018;99:41-52.

Ring N, Jepson R, Ritchie K. Methods of synthesizing qualitative research studies for health technology assessment . International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care . 2011;27:384-390.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation . International journal of evidence-based healthcare . 2015;13:179-187.

France EF, Cunningham M, Ring N, et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance . Journal of advanced nursing . 2019.

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2009;9:59. Published 2009 Aug 11. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-9-59.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2008;8:45. Published 2008 Jul 10. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series . Implementation science : IS . 2018;13:2.

"Narrative synthesis refers to an approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis. Whilst narrative synthesis can involve the manipulation of statistical data, the defining characteristic is that it adopts a textual approach to the process of synthesis to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from the included studies." (Popay J, 2006)

Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Antony J, et al. A scoping review identifies multiple emerging knowledge synthesis methods, but few studies operationalize the method . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology . 2016;73:19-28.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews . Lancaster: ESRC Research Methods Programme; 2006.

Snilstveit B, Oliver S, Vojtkova M. Narrative approaches to systematic review and synthesis of evidence for international development policy and practice . Journal of development effectiveness . 2012 Sep 1;4(3):409-29.

Lucas PJ, Baird J, Arai L, Law C, Roberts HM. Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews . BMC medical research methodology . 2007 Dec;7(1):4.

Ryan R. Cochrane Consumer sand Communication Review Group. Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: data synthesis and analysis . June 2013.

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 10:29 AM

- URL: https://guides.hsict.library.utoronto.ca/c.php?g=705263

We acknowledge this sacred land on which the University Health Network operates. For thousands of years it has been the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat, the Haudenosaunee, and most recently, the Mississaugas of the Credit River. This territory was the subject of the Dish With One Spoon Wampum Belt Covenant, an agreement between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Confederacy of the Ojibwe and allied nations to peaceably share and care for the resources around the Great Lakes. Today, the meeting place of Toronto is still the home to many Indigenous people from across Turtle Island and we are grateful to have the opportunity to work and learn on this territory

UHN Library and Information Services

Covidence website will be inaccessible as we upgrading our platform on Monday 23rd August at 10am AEST, / 2am CEST/1am BST (Sunday, 15th August 8pm EDT/5pm PDT)

The difference between a systematic review and a literature review

- Best Practice

Home | Blog | Best Practice | The difference between a systematic review and a literature review

Covidence takes a look at the difference between the two

Most of us are familiar with the terms systematic review and literature review. Both review types synthesise evidence and provide summary information. So what are the differences? What does systematic mean? And which approach is best 🤔 ?

‘ Systematic ‘ describes the review’s methods. It means that they are transparent, reproducible and defined before the search gets underway. That’s important because it helps to minimise the bias that would result from cherry-picking studies in a non-systematic way.

This brings us to literature reviews. Literature reviews don’t usually apply the same rigour in their methods. That’s because, unlike systematic reviews, they don’t aim to produce an answer to a clinical question. Literature reviews can provide context or background information for a new piece of research. They can also stand alone as a general guide to what is already known about a particular topic.

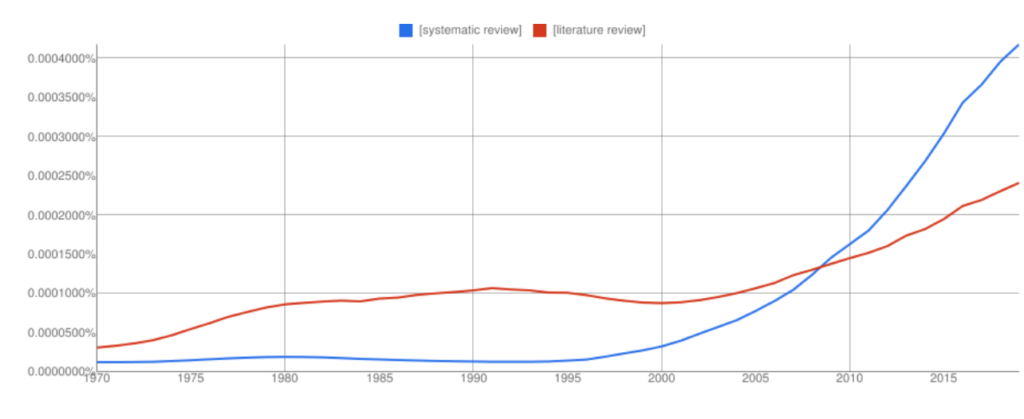

Interest in systematic reviews has grown in recent years and the frequency of ‘systematic reviews’ in Google books has overtaken ‘literature reviews’ (with all the usual Ngram Viewer warnings – it searches around 6% of all books, no journals).

Let’s take a look at the two review types in more detail to highlight some key similarities and differences 👀.

🙋🏾♂️ What is a systematic review?

Systematic reviews ask a specific question about the effectiveness of a treatment and answer it by summarising evidence that meets a set of pre-specified criteria.

The process starts with a research question and a protocol or research plan. A review team searches for studies to answer the question using a highly sensitive search strategy. The retrieved studies are then screened for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (this is done by at least two people working independently). Next, the reviewers extract the relevant data and assess the quality of the included studies. Finally, the review team synthesises the extracted study data and presents the results. The process is shown in figure 2 .

The results of a systematic review can be presented in many ways and the choice will depend on factors such as the type of data. Some reviews use meta-analysis to produce a statistical summary of effect estimates. Other reviews use narrative synthesis to present a textual summary.

Covidence accelerates the screening, data extraction, and quality assessment stages of your systematic review. It provides simple workflows and easy collaboration with colleagues around the world.

When is it appropriate to do a systematic review?

If you have a clinical question about the effectiveness of a particular treatment or treatments, you could answer it by conducting a systematic review. Systematic reviews in clinical medicine often follow the PICO framework, which stands for:

👦 Population (or patients)

💊 Intervention

💊 Comparison

Here’s a typical example of a systematic review title that uses the PICO framework: Alarms [intervention] versus drug treatments [comparison] for the prevention of nocturnal enuresis [outcome] in children [population]

Key attributes

- Systematic reviews follow prespecified methods

- The methods are explicit and replicable

- The review team assesses the quality of the evidence and attempts to minimise bias

- Results and conclusions are based on the evidence

🙋🏻♀️ What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide an overview of what is known about a particular topic. They evaluate the material, rather than simply restating it, but the methods used to do this are not usually prespecified and they are not described in detail in the review. The search might be comprehensive but it does not aim to be exhaustive. Literature reviews are also referred to as narrative reviews.

Literature reviews use a topical approach and often take the form of a discussion. Precision and replicability are not the focus, rather the author seeks to demonstrate their understanding and perhaps also present their work in the context of what has come before. Often, this sort of synthesis does not attempt to control for the author’s own bias. The results or conclusion of a literature review is likely to be presented using words rather than statistical methods.

When is it appropriate to do a literature review?

We’ve all written some form of literature review: they are a central part of academic research ✍🏾. Literature reviews often form the introduction to a piece of writing, to provide the context. They can also be used to identify gaps in the literature and the need to fill them with new research 📚.

- Literature reviews take a thematic approach

- They do not specify inclusion or exclusion criteria

- They do not answer a clinical question

- The conclusions might be influenced by the author’s own views

🙋🏽 Ok, but what is a systematic literature review?

A quick internet search retrieves a cool 200 million hits for ‘systematic literature review’. What strange hybrid is this 🤯🤯 ?

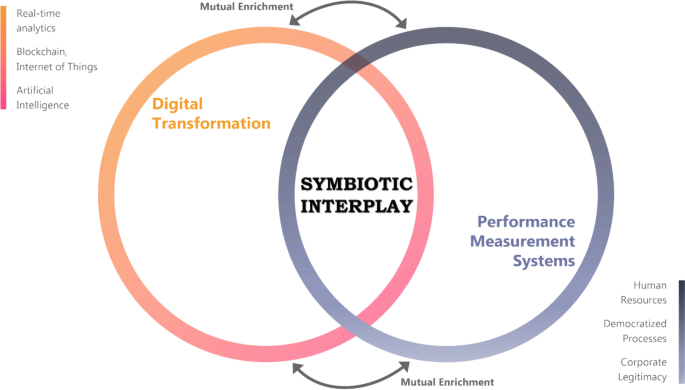

Systematic review methodology has its roots in evidence-based medicine but it quickly gained traction in other areas – the social sciences for example – where researchers recognise the value of being methodical and minimising bias. Systematic review methods are increasingly applied to the more traditional types of review, including literature reviews, hence the proliferation of terms like ‘systematic literature review’ and many more.

Beware of the labels 🚨. The terminology used to describe review types can vary by discipline and changes over time. To really understand how any review was done you will need to examine the methods critically and make your own assessment of the quality and reliability of each synthesis 🤓.

Review methods are evolving constantly as researchers find new ways to meet the challenge of synthesising the evidence. Systematic review methods have influenced many other review types, including the traditional literature review.

Covidence is a web-based tool that saves you time at the screening, selection, data extraction and quality assessment stages of your systematic review. It supports easy collaboration across teams and provides a clear overview of task status.

Get a glimpse inside Covidence and how it works

Laura Mellor. Portsmouth, UK

Perhaps you'd also like....

Data Extraction Tip 5: Communicate Regularly

The Covidence Global Scholarship recipients are putting evidence-based research into practice. We caught up with some of the winners to discover the impact of their work and find out more about their experiences.

Data Extraction Tip 4: Extract the Right Amount of Data

Data Extraction Tip 3: Pilot the Template

Better systematic review management, head office, working for an institution or organisation.

Find out why over 350 of the world’s leading institutions are seeing a surge in publications since using Covidence!

Request a consultation with one of our team members and start empowering your researchers:

By using our site you consent to our use of cookies to measure and improve our site’s performance. Please see our Privacy Policy for more information.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Systematic Review of the Literature: Best Practices

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Radiology and Imaging, Rush University Medical Center, 3833, 1653 W Congress Pkwy, Chicago, IL 60612. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Cardiothoracic Imaging, Department of Radiology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Boulevard, Dallas, TX, USA.

- 3 Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, 4500 San Pablo Rd, Jacksonville, FL 32224.

- 4 Chief, Cardiothoracic and Emergency Radiology, Department of Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, USA.

- 5 Department of Diagnostic Radiology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd. Unit 1478, Houston, TX, 77030.

- 6 Department of Medical Imaging, University of Toronto, 263 McCaul Street, 4th Floor, Toronto, ON, M5T 1W7.

- 7 Department of Radiology, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, Department of Radiology and Radiological Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, 96 Jonathan Lucas St. MSC 323, Charleston, SC 29425.

- 8 Department of Radiology and Medical Imaging, University of Virginia Medical Center, 1215 Lee St., Charlottesville, VA 22903.

- PMID: 30442379

- DOI: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.04.025

Reviews of published scientific literature are a valuable resource that can underline best practices in medicine and clarify clinical controversies. Among the various types of reviews, the systematic review of the literature is ranked as the most rigorous since it is a high-level summary of existing evidence focused on answering a precise question. Systematic reviews employ a pre-defined protocol to identify relevant and trustworthy literature. Such reviews can accomplish several critical goals that are not easily achievable with typical empirical studies by allowing identification and discussion of best evidence, contradictory findings, and gaps in the literature. The Association of University Radiologists Radiology Research Alliance Systematic Review Task Force convened to explore the methodology and practical considerations involved in performing a systematic review. This article provides a detailed and practical guide for performing a systematic review and discusses its applications in radiology.

Keywords: effective systematic review; radiology review; research methodology; systematic review.

Copyright © 2018. Published by Elsevier Inc.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- How Systematic Review Can Shape Clinical Practice in Radiology. Kim TH, Woo S. Kim TH, et al. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024 Jan;222(1):e2329603. doi: 10.2214/AJR.23.29603. Epub 2023 Jul 26. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024. PMID: 37493323

- Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Aromataris E, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):132-40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015. PMID: 26360830

- Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: methodological approaches to evaluate the literature and establish best evidence. Skelly AC, Hashimoto RE, Norvell DC, Dettori JR, Fischer DJ, Wilson JR, Tetreault LA, Fehlings MG. Skelly AC, et al. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013 Oct 15;38(22 Suppl 1):S9-18. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7ebbf. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013. PMID: 24026148

- Decision and Simulation Modeling in Systematic Reviews [Internet]. Kuntz K, Sainfort F, Butler M, Taylor B, Kulasingam S, Gregory S, Mann E, Anderson JM, Kane RL. Kuntz K, et al. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Feb. Report No.: 11(13)-EHC037-EF. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013 Feb. Report No.: 11(13)-EHC037-EF. PMID: 23534078 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management, part I: introduction and general considerations. Manchikanti L. Manchikanti L. Pain Physician. 2008 Mar-Apr;11(2):161-86. Pain Physician. 2008. PMID: 18354710 Review.

- Identifying and ranking employer brand improvement strategies in post-COVID 19 tourism and hospitality. Bagheri M, Baum T, Mobasheri AA, Nikbakht A. Bagheri M, et al. Tour Hosp Res. 2023 Jul;23(3):391-405. doi: 10.1177/14673584221112607. Epub 2022 Jul 4. Tour Hosp Res. 2023. PMID: 37350846 Free PMC article.

- A bibliometric analysis of systematic reviews and meta-analyses in ophthalmology. Fu Y, Mao Y, Jiang S, Luo S, Chen X, Xiao W. Fu Y, et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 2;10:1135592. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1135592. eCollection 2023. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023. PMID: 36936241 Free PMC article.

- Developing pre-service teachers' computational thinking: a systematic literature review. Dong W, Li Y, Sun L, Liu Y. Dong W, et al. Int J Technol Des Educ. 2023 Feb 13:1-37. doi: 10.1007/s10798-023-09811-3. Online ahead of print. Int J Technol Des Educ. 2023. PMID: 36816094 Free PMC article.

- Machine learning computational tools to assist the performance of systematic reviews: A mapping review. Cierco Jimenez R, Lee T, Rosillo N, Cordova R, Cree IA, Gonzalez A, Indave Ruiz BI. Cierco Jimenez R, et al. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022 Dec 16;22(1):322. doi: 10.1186/s12874-022-01805-4. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022. PMID: 36522637 Free PMC article. Review.

- Review of Microgels for Enhanced Oil Recovery: Properties and Cases of Application. Rozhkova YA, Burin DA, Galkin SV, Yang H. Rozhkova YA, et al. Gels. 2022 Feb 11;8(2):112. doi: 10.3390/gels8020112. Gels. 2022. PMID: 35200492 Free PMC article. Review.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Penn State University Libraries

- Home-Articles and Databases

- Asking the clinical question

- PICO & Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

- Ethical & Legal Issues for Nurses

- Nursing Library Instruction Course

- Data Management Toolkit This link opens in a new window

- Useful Nursing Resources

- Writing Resources

- LionSearch and Finding Articles

- The Catalog and Finding Books

Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

It is common to confuse systematic and literature reviews as both are used to provide a summary of the existent literature or research on a specific topic. Even with this common ground, both types vary significantly. Please review the following chart (and its corresponding poster linked below) for the detailed explanation of each as well as the differences between each type of review.

| Systematic Review | Literature Review | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | High-level overview of primary research on a focused question that identifies, selects, synthesizes, and appraises all high quality research evidence relevant to that question | Qualitatively summarizes evidence on a topic using informal or subjective methods to collect and interpret studies |

| Goals | Answers a focused clinical question Eliminate bias | Provide summary or overview of topic |

| Question | Clearly defined and answerable clinical question Recommend using PICO as a guide | Can be a general topic or a specific question |

| Components | Pre-specified eligibility criteria Systematic search strategy Assessment of the validity of findings Interpretation and presentation of results Reference list | Introduction Methods Discussion Conclusion Reference list |

| Number of Authors | Three or more | One or more |

| Timeline | Months to years Average eighteen months | Weeks to months |

| Requirement | Thorough knowledge of topic Perform searches of all relevant databases Statistical analysis resources (for meta-analysis) | Understanding of topic |

| Value | Connects practicing clinicians to high quality evidence Supports evidence-based practice | Provides summary of literature on the topic |

- What's in a name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters by Lynn Kysh, MLIS, University of Southern California - Norris Medical Library

- << Previous: Evaluating the Evidence

- Next: Ethical & Legal Issues for Nurses >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 11:54 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/nursing

Communicative Sciences and Disorders

- Online Learners: Quick Links

- ASHA Journals

- Research Tip 1: Define the Research Question

- Reference Resources

- Evidence Summaries & Clinical Guidelines

- Drug Information

- Health Data & Statistics

- Patient/Consumer Facing Materials

- Images/Streaming Video

- Database Tutorials

- Crafting a Search

- Cited Reference Searching

- Research Tip 4: Find Grey Literature

- Research Tip 5: Save Your Work

- Cite and Manage Your Sources

- Critical Appraisal

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

- Point of Care Tools (Mobile Apps)

Choosing a Review Type

For guidance related to choosing a review type, see:

- "What Type of Review is Right for You?" - Decision Tree (PDF) This decision tree, from Cornell University Library, highlights key difference between narrative, systematic, umbrella, scoping and rapid reviews.