An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Science and Technology Directorate

Feature Article: Here’s What We’ve Learned About COVID-19

Flu season is here and with the coronavirus pandemic still plaguing much of the world, it’s more important than ever to be health conscious. Countless scientists all over the world are striving to better understand SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and bringing the most relevant research findings together in one place is key to a coordinated effort.

The Master Question List (MQL) does just that. The MQL organizes our collective knowledge. This consolidation of recent, trustworthy COVID-19 information is updated every week with the latest results and data relevant to weathering the pandemic. The Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) started publishing the MQL this past Spring as part of its COVID-19 response .

According to Dr. Lloyd Hough, director of S&T’s Hazard Awareness and Characterization Technology Center, “We go out and conduct searches of a variety of different publications and sources—some of them are traditional scientific sources like the National Library of Medicine, but there are also journal websites and news sources. We go through a lot of these sources and look for vetted information from reliable sources.”

“The MQL is important for us because it identifies what we don’t know,” continued Dr. Hough. “And with finite lab resources, it ensures we don’t duplicate something that is already being studied elsewhere. It’s really a matter of identifying the highest priority gaps—the things that are most impactful for better understanding the disease and helping us to respond to it.”

The list of what we don’t know is still long, but thanks to the dedication of numerous researchers, such as those at S&T’s National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center (NBACC), many important questions have been answered.

How does it spread from one host to another? How easily is it spread?

COVID-19 is highly contagious, and you can catch it by simply inhaling. It was clear early on that COVID-19 was easily spread through close contact, whether that was person-to-person or by touching contaminated surfaces. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has now acknowledged that airborne transmission is possible under certain circumstances, meaning the virus can spread through particles in the air and not just the larger droplets that can be spread short distances.

It is also important to note that COVID-19 can infect anyone, though it’s worse for some than others. The CDC has found that most symptomatic cases are mild, but severe disease can be found in any age group . Children have proven susceptible (PDF, 28 pgs., 1.85 MB) to COVID-19. We don’t know exactly how infectious they are, but children with positive cases appear to have as much SARS-CoV-2 in their upper respiratory tract as adults.

How long does the virus live in the environment?

How long after infection do symptoms appear? Are people infectious during this time?

According to research collected in the MQL, on average, symptoms develop five days after exposure to the virus and individuals are most infectious before they start showing symptoms. Early iterations of the MQL noted that, “Identifying the contribution of asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic transmission is important for implementing control measures” and this has turned out to be quite true. We now know that pre-symptomatic transmission causes around 40 percent of infections . Also, patients who don’t show any symptoms during the course of their infection can definitely spread the virus. It turns out asymptomatic individuals can transmit the disease as soon as two days after they become infected and at least 12 percent (PDF, 15 pgs., 444 KB) of all cases are estimated to be due to asymptomatic transmission. The CDC recommends that anyone, including those without symptoms, who has been in close contact with a positive COVID-19 case should be tested.

What are the signs and symptoms of an infected person?

Can individuals become re-infected after recovery?

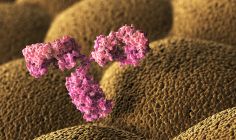

Studies show that re-infection is possible , but rare . Neutralizing antibodies develop in most patients , but the duration of any protection is unknown.

What personal protective equipment (PPE) is effective, and who should be using it?

Face masks are effective at reducing transmission of COVID-19 and almost everyone should be using them. Numerous studies have supported this finding, including research published by the American Society for Microbiology , (PDF, 5 pgs., 1.64MB) the Journal of the American Medical Association , and Nature Research .

The World Health Organization and U.S. CDC recommend wearing face masks when in public settings and when physical distancing is difficult. The benefit is maximized when most of the population wears face masks. Studies show we should avoid masks with exhalation vents or valves as they can allow particles to pass through unfiltered. Medical-grade respirators such as N95 face masks should be reserved for those most vulnerable. S&T research has shown that if handled properly, filtering facepiece respirators can be safely decontaminated for reuse . We also now have data published by the National Institutes of Health showing the effectiveness of homemade face masks varies based on the material used. Layered cotton fabrics with raised visible fibers are best when compared to other household materials such as t-shirts, bandanas, or towels.

How effective are social distancing measures?

Broad-scale control measures such as stay-at-home orders are effective at reducing transmission , as shown by research published in the Journal of Public Health Management & Practice and elsewhere. Social distancing and reductions in both non-essential visits to stores and overall movement distance led to lower transmission rates of COVID-19 in the United States. In hindsight, the data show each day of delay in emergency declarations and school closures was associated with a 5-6 percent increase in mortality . Contact tracing combined with high levels of testing and physical distancing may limit COVID-19 resurgence as restrictions are eased.

There is a path forward.

There are still some questions we don’t have the answer to, like “ How much of the virus will make a healthy individual ill?” which once answered, will help make disinfection efforts, transmission models, and diagnostic practices more accurate. And of course, researchers are furiously working to find effective treatments and a vaccine.

“This is a scary, challenging time,” said Dr. Hough. “We owe it to the essential workers, the overwhelmed parents, the unemployed, and most of all, those who have fallen prey to this insidious disease to do all that we can to be responsible members of our communities. The public needs to buy time for our scientific and medical community.”

In the meantime, we need to follow the recommendations of the CDC and our local public health authorities and stay informed. If you’d like to learn more about any of the science presented here, check out the MQL . Over 700 studies are cited, and again, it is updated every week. You can find comprehensive public health guidance on the CDC website . For related media requests, contact [email protected] .

- Science and Technology

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Environment

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes of Health

Featured Articles : COVID-19

Navigating long COVID

Mark Elliott, Ph.D., is a 66-year-old associate professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular medicine at George Washington...

The long haul: When COVID-19 symptoms don’t go away

*This article is an update to the original article, published on July 6, 2021. It was updated in July 2022 to reflect new...

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

Most children who get infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 have mild or no symptoms and some may also...

COVID-19 makes living with a rare disease even harder

Ongoing uncertainty, being alone, and not being able to get treatment. In many ways, the widespread challenges the COVID-19 pandemic...

New decision-support tool for COVID-19 testing can help you get back to your life, safely

Almost two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s still so much uncertainty about how to live with this virus. We have...

Updates on COVID-19 vaccines in pregnant people

Andrea Edlow, M.D., is a maternal-fetal medicine specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. When COVID-19 hit, her lab began researching...

Pregnant during COVID-19? Tips to stay safe

Pregnant people are at an increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19 compared with nonpregnant people. Andrea Edlow, M.D.,...

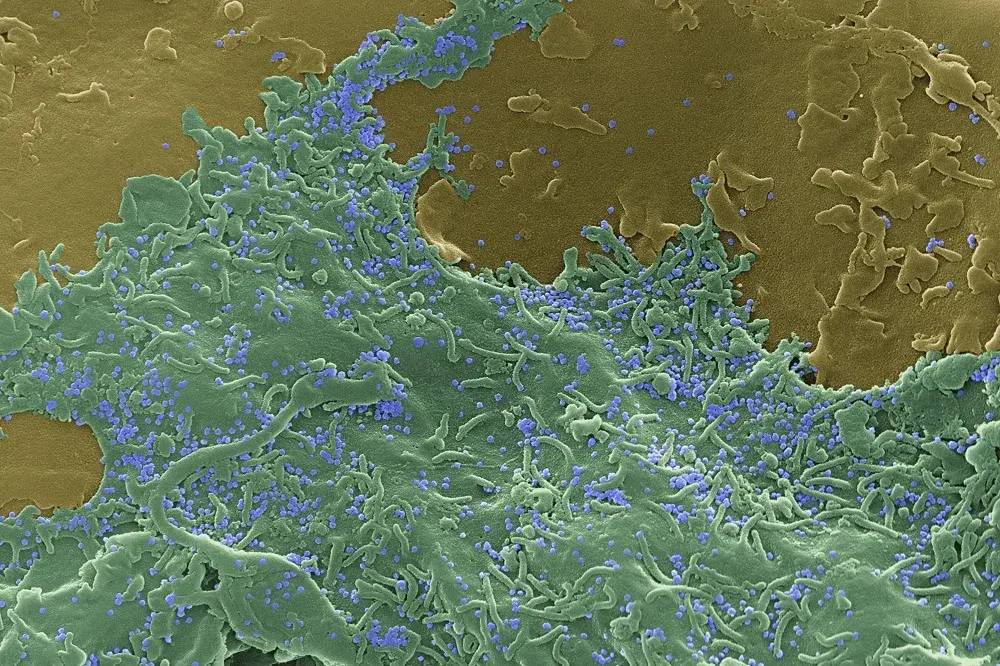

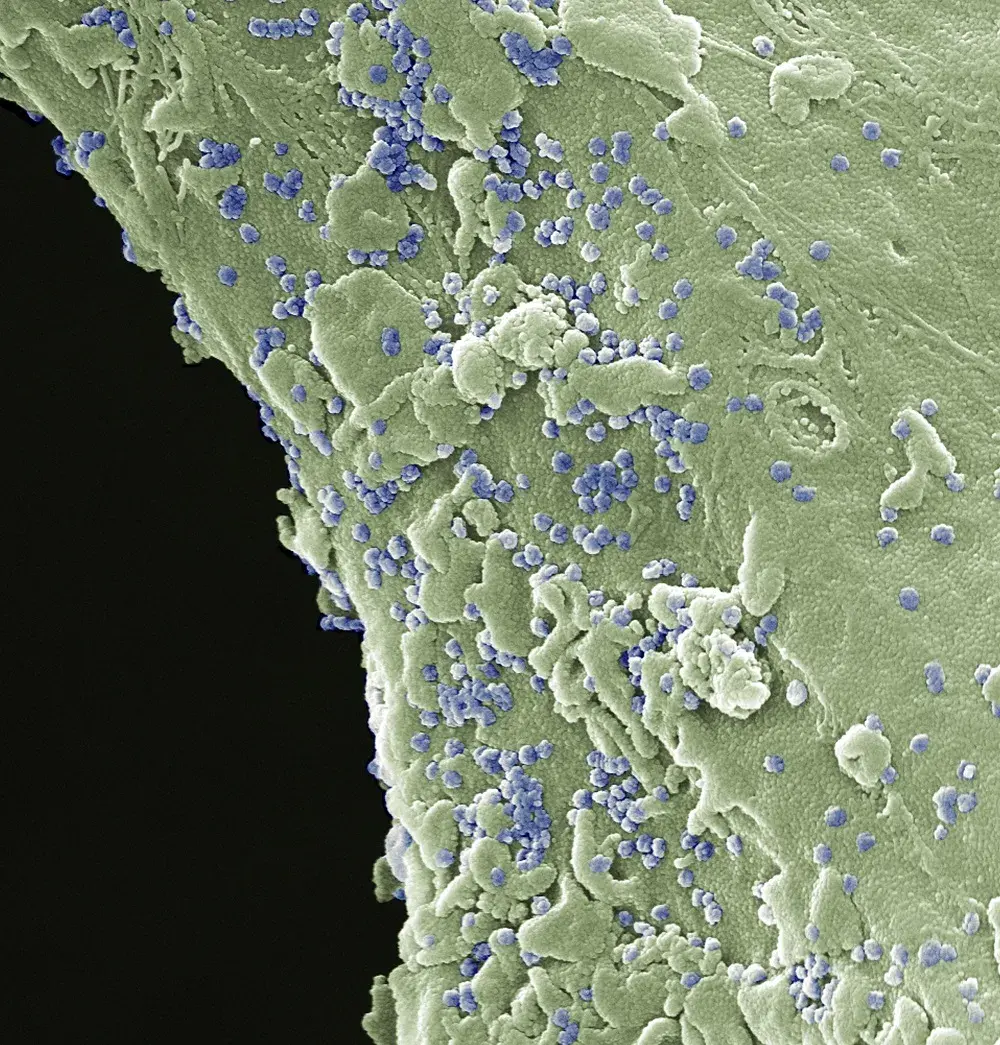

SARS-CoV-2: Up close

The genetic blueprint material for SARS-CoV-2 is called RNA (yellow spirals). The RNA contains information to specify the amino acids...

Your COVID-19 Glossary

Here's a list of health terms to help you navigate the latest COVID-19 research and updates. Efficacy: How well...

9 tips to address COVID-19 at work

Heading back to your workplace soon? Here are some tips from the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease...

Trusted health information delivered to your inbox

Enter your email below

- Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- HIV and AIDS

- Hypertension

- Mental disorders

- Top 10 causes of death

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- Data collection tools

- Global Health Observatory

- Insights and visualizations

- COVID excess deaths

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Questions and answers /

WHO is continuously monitoring and responding to this pandemic. This questions and answers page will be updated as more is known about COVID-19, how it spreads and how it is affecting people worldwide. For more information, regularly check the WHO coronavirus pages. https://www.who.int/covid-19

The most common symptoms of COVID-19 are

- fever

- sore throat.

Other symptoms that are less common and may affect some patients include:

- muscle aches

- severe fatigue or tiredness

- runny or blocked nose, or sneezing

- new and persistent cough

- tight chest or chest pain

- shortness of breath

- hoarse voice

- heavy arms/legs

- numbness/tingling

- nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain/ belly ache, or diarrhoea

- appetite loss

- loss or change of sense of taste or smell

- difficulty sleeping.

Symptoms of severe COVID‐19 disease which need immediate medical attention include:

- difficulty in breathing, especially at rest, or unable to speak in sentences

- drowsiness or loss of consciousness

- persistent pain or pressure in the chest

- skin being cold or clammy, or turning pale or a bluish colour

- loss of speech or movement.

If possible, call your health care provider, hotline or health facility first, so you can be directed to the right clinic.

People who have pre-existing health problems are at higher risk when they have COVID-19; they should seek medical help early if worried about their condition. These include, but are not limited to: those taking immunosuppressive medication; those with chronic heart, lung, liver or rheumatological problems; those with HIV, diabetes, cancer or dementia.

As testing rates fall, it is more difficult to know how many people have COVID-19 and do not seek any treatment. At the start of the pandemic, 15% of people were thought to become seriously unwell and require hospital treatment and oxygen. More recent estimates suggest that hospitalization is required in around 3% of people with COVID-19. This is partly due to immunization, partly due to changes in the virus (especially the Omicron variants), and partly due to the availability of targeted medical treatments.

Most people make a full recovery without needing hospital treatment. For those with COVID-19 who are at high risk of severe illness (see question below), WHO has made recommendations on which drug treatments are effective in improving outcomes and preventing hospital admissions.

It is also important to be vigilant in recognizing people with severe disease and those needing hospital treatment so that they are treated early. The consequences of severe COVID-19 include death, respiratory failure, sepsis, thromboembolism (blood clots), and multiorgan failure, including injury of the heart, liver or kidneys.

In rare situations, children can develop a severe inflammatory syndrome a few weeks after infection.

People aged 60 years and over, and those with underlying medical problems like high blood pressure, diabetes, other chronic health problems (for example those affecting the heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain), low immune function / immunosuppression (including HIV), obesity, cancer, and unvaccinated people are most at risk of severe illness.

However, anyone at any age can get sick with COVID-19 and become seriously ill or die.

Some people who have had COVID-19, whether they have needed hospitalization or not, continue to experience symptoms, including fatigue, respiratory and neurological symptoms. These long-term effects are called post COVID-19 condition (also called long COVID). For further information on long COVID , see post COVID-19 condition and questions and answers .

You can protect yourself and others from COVID-19 by following preventive measures, such as keeping a distance, wearing a mask in crowded and poorly ventilated spaces, practicing hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette (covering your mouth and nose with a bent elbow or a tissue when you cough or sneeze), getting vaccinated and staying up to date with booster doses.

Check local advice where you live and work.

Read our public advice page for more information.

Anyone with symptoms such as acute onset of fever and cough should be tested, wherever possible, to ensure that they receive appropriate clinical care. People who do not have symptoms but have had close contact with someone who is, or may be, infected may also consider testing. Contact your local health guidelines and follow their guidance.

While a person is waiting for test results, they should preferably wear a mask when interacting with others in or outside of their household or sharing space with others. Where testing capacity is limited, tests should first be done for those at higher risk of infection, such as health workers, and those at higher risk of severe illness such as older people, especially those living in seniors’ residences or long-term care facilities.

Individuals with signs and symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 or those who test positive for the virus should wear a mask when interacting with others in or outside of one’s household or sharing space with others.

There are two main types of tests that can confirm whether you are infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Molecular tests, such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), are the most accurate tests for diagnosing SARS-CoV-2 infection. Molecular tests detect virus in the sample by amplifying viral genetic material to detectable levels. Rapid antigen tests (sometimes known as rapid diagnostic tests or RDTs) detect viral proteins (known as antigens). RDTs are a simpler and faster option than molecular tests and are available for testing by trained operators or by the individual themselves (sometimes called self-tests). They perform best when there is more virus circulating in the community and when sampled from an individual during the time they are most infectious, generally within the first 5–7 days following symptom onset. Samples for both types of tests are collected from the nose and/or throat with a swab.

Learn more about what kind of COVID-19 tests are available

Why testing for SARS-CoV-2 is important

Use of Ag-RDTs

What you need to know about self-testing

Antibody tests can tell us whether someone has had an infection in the past, even if they have not had symptoms. Also known as serological tests, these tests detect antibodies produced in response to an infection or vaccination. In most people, antibodies start to develop after days to weeks and can indicate if a person has had past infection or has been vaccinated. Antibody tests cannot be used to diagnose SARS-CoV-2 infection in the early stages of infection or disease but can indicate whether or not someone has had the disease in the past. If you have been vaccinated, many antibody tests are not able to distinguish between whether you were previously infected or have been vaccinated (or both), so in such situations you will test positive in either case.

Both isolation and quarantine are methods of preventing the spread of COVID-19.

Quarantine is used for certain persons who are a contact of someone infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, whether the infected person has symptoms or not. Quarantine means that you remain separated from others because you have been exposed to the virus and you may be infected and can take place in a designated facility or at home. For COVID-19, this means staying in the facility or at home for several days.

Isolation is used for people with COVID-19 symptoms or who have tested positive for the virus. Being in isolation means being separated from other people, ideally in a medical facility where you can receive clinical care. If isolation in a medical facility is not possible and you are not in a high-risk group for developing severe disease, isolation can take place at home. If you have symptoms, you should remain in isolation for at least 10 days. If you are infected and do not develop symptoms, you should remain in isolation for 5 days from the time you test positive. You can be discharged from isolation early if you test negative on a rapid antigen test.

If you have been exposed to someone with COVID-19, you may become infected, even if you feel well.

After exposure to someone who has COVID-19, do the following:

- Call your healthcare provider to get tested or test yourself.

- Stay home if you feel unwell.

- Wear a mask when interacting with others in or outside of your household or sharing space with others.

- Clean your hands regularly.

- Practice respiratory etiquette: cover your mouth and nose with your bent elbow or a tissue when you cough or sneeze.

- Avoid crowded, enclosed or poorly ventilated spaces.

- Get vaccinated and stay up to date with booster doses.

The time from exposure to COVID-19 to the moment when symptoms begin is, on average, 5–6 days and can range from 1–14 days. This is why people who have been exposed to the virus are advised to remain at home and stay away from others in order to prevent the spread of the virus.

Yes. There are several COVID-19 vaccines validated for use by WHO (given Emergency Use Listing) and from other stringent national regulatory agencies (SRAs). The first mass vaccination programme started in early December 2020 and the number of vaccination doses administered is updated on a regular basis here . For more information on vaccine for COVID-19, see the vaccine questions and answers: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Vaccines (who.int)

- If you are unwell, stay at home.

- If you have any symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, wear a mask when interacting with others in or outside of your household or sharing space with others. If you have shortness of breath or pain or pressure in the chest, seek medical attention at a health facility immediately. Call your health care provider or hotline in advance for direction to the right health facility.

- Get tested for COVID-19, regardless of your vaccination status, and especially if you are at high-risk for severe illness and could therefore be eligible for drug treatments.

- Practice protective and preventive measures. Wear a mask, avoid crowded and poorly ventilated areas, improve ventilation in indoor spaces, keep a distance, practice hand hygiene, and respiratory etiquette (covering your mouth and nose with a bent elbow or a tissue when you cough or sneeze), get vaccinated and stay up to date with booster doses.

There has been huge progress in developing treatments for patients with COVID-19. Treatments for COVID-19 should be decided on an individual basis between the person and the healthcare professional looking after them. The choice will depend on the severity of disease and the risk of disease worsening (including the person’s age and whether they have any health problems). WHO maintains a list of recommended treatments, together with the evidence for each, available at https://app.magicapp.org/#/guideline/nBkO1E .

These currently include:

- for non-severe COVID-19: nirmatrelvir-ritonavir; molnupiravir; remdesivir

- for severe COVID-19: corticosteroids (including dexamethasone); IL-6 receptor blockers (tocilizumab or sarilumab); baricitinib; remdesivir.

Apart from these medications, amongst the most commonly and globally used, and important treatments is oxygen for severely ill patients. WHO leads work which aims to improve global capacity and access to oxygen production, distribution and supply to patients.

For corticosteroids, further specific information can be found in the Corticosteroids, including dexamethasone questions and answers .

Antibiotics do not work against viruses; they only work on bacterial infections. COVID-19 is caused by a virus, so antibiotics do not work. Antibiotics should not be used as a means of prevention or treatment of COVID-19.

In hospitals, physicians will sometimes use antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections, which can be a complication of COVID-19 in severely ill patients. They should only be used as directed by a physician to treat a bacterial infection.

Start the conversation

COVID-19 hub

Advice for the public

All COVID-19 Q&As

WHO Information Network on Epidemics (EPI-WIN)

Science in 5 series : WHO experts explain the science related to COVID-19

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A Review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19)

Tanu singhal.

Department of Pediatrics and Infectious Disease, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani Hospital and Medical Research Institute, Mumbai, India

There is a new public health crises threatening the world with the emergence and spread of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The virus originated in bats and was transmitted to humans through yet unknown intermediary animals in Wuhan, Hubei province, China in December 2019. There have been around 96,000 reported cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-2019) and 3300 reported deaths to date (05/03/2020). The disease is transmitted by inhalation or contact with infected droplets and the incubation period ranges from 2 to 14 d. The symptoms are usually fever, cough, sore throat, breathlessness, fatigue, malaise among others. The disease is mild in most people; in some (usually the elderly and those with comorbidities), it may progress to pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multi organ dysfunction. Many people are asymptomatic. The case fatality rate is estimated to range from 2 to 3%. Diagnosis is by demonstration of the virus in respiratory secretions by special molecular tests. Common laboratory findings include normal/ low white cell counts with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP). The computerized tomographic chest scan is usually abnormal even in those with no symptoms or mild disease. Treatment is essentially supportive; role of antiviral agents is yet to be established. Prevention entails home isolation of suspected cases and those with mild illnesses and strict infection control measures at hospitals that include contact and droplet precautions. The virus spreads faster than its two ancestors the SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), but has lower fatality. The global impact of this new epidemic is yet uncertain.

Introduction

The 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or the severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as it is now called, is rapidly spreading from its origin in Wuhan City of Hubei Province of China to the rest of the world [ 1 ]. Till 05/03/2020 around 96,000 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and 3300 deaths have been reported [ 2 ]. India has reported 29 cases till date. Fortunately so far, children have been infrequently affected with no deaths. But the future course of this virus is unknown. This article gives a bird’s eye view about this new virus. Since knowledge about this virus is rapidly evolving, readers are urged to update themselves regularly.

Coronaviruses are enveloped positive sense RNA viruses ranging from 60 nm to 140 nm in diameter with spike like projections on its surface giving it a crown like appearance under the electron microscope; hence the name coronavirus [ 3 ]. Four corona viruses namely HKU1, NL63, 229E and OC43 have been in circulation in humans, and generally cause mild respiratory disease.

There have been two events in the past two decades wherein crossover of animal betacorona viruses to humans has resulted in severe disease. The first such instance was in 2002–2003 when a new coronavirus of the β genera and with origin in bats crossed over to humans via the intermediary host of palm civet cats in the Guangdong province of China. This virus, designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus affected 8422 people mostly in China and Hong Kong and caused 916 deaths (mortality rate 11%) before being contained [ 4 ]. Almost a decade later in 2012, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), also of bat origin, emerged in Saudi Arabia with dromedary camels as the intermediate host and affected 2494 people and caused 858 deaths (fatality rate 34%) [ 5 ].

Origin and Spread of COVID-19 [ 1 , 2 , 6 ]

In December 2019, adults in Wuhan, capital city of Hubei province and a major transportation hub of China started presenting to local hospitals with severe pneumonia of unknown cause. Many of the initial cases had a common exposure to the Huanan wholesale seafood market that also traded live animals. The surveillance system (put into place after the SARS outbreak) was activated and respiratory samples of patients were sent to reference labs for etiologic investigations. On December 31st 2019, China notified the outbreak to the World Health Organization and on 1st January the Huanan sea food market was closed. On 7th January the virus was identified as a coronavirus that had >95% homology with the bat coronavirus and > 70% similarity with the SARS- CoV. Environmental samples from the Huanan sea food market also tested positive, signifying that the virus originated from there [ 7 ]. The number of cases started increasing exponentially, some of which did not have exposure to the live animal market, suggestive of the fact that human-to-human transmission was occurring [ 8 ]. The first fatal case was reported on 11th Jan 2020. The massive migration of Chinese during the Chinese New Year fuelled the epidemic. Cases in other provinces of China, other countries (Thailand, Japan and South Korea in quick succession) were reported in people who were returning from Wuhan. Transmission to healthcare workers caring for patients was described on 20th Jan, 2020. By 23rd January, the 11 million population of Wuhan was placed under lock down with restrictions of entry and exit from the region. Soon this lock down was extended to other cities of Hubei province. Cases of COVID-19 in countries outside China were reported in those with no history of travel to China suggesting that local human-to-human transmission was occurring in these countries [ 9 ]. Airports in different countries including India put in screening mechanisms to detect symptomatic people returning from China and placed them in isolation and testing them for COVID-19. Soon it was apparent that the infection could be transmitted from asymptomatic people and also before onset of symptoms. Therefore, countries including India who evacuated their citizens from Wuhan through special flights or had travellers returning from China, placed all people symptomatic or otherwise in isolation for 14 d and tested them for the virus.

Cases continued to increase exponentially and modelling studies reported an epidemic doubling time of 1.8 d [ 10 ]. In fact on the 12th of February, China changed its definition of confirmed cases to include patients with negative/ pending molecular tests but with clinical, radiologic and epidemiologic features of COVID-19 leading to an increase in cases by 15,000 in a single day [ 6 ]. As of 05/03/2020 96,000 cases worldwide (80,000 in China) and 87 other countries and 1 international conveyance (696, in the cruise ship Diamond Princess parked off the coast of Japan) have been reported [ 2 ]. It is important to note that while the number of new cases has reduced in China lately, they have increased exponentially in other countries including South Korea, Italy and Iran. Of those infected, 20% are in critical condition, 25% have recovered, and 3310 (3013 in China and 297 in other countries) have died [ 2 ]. India, which had reported only 3 cases till 2/3/2020, has also seen a sudden spurt in cases. By 5/3/2020, 29 cases had been reported; mostly in Delhi, Jaipur and Agra in Italian tourists and their contacts. One case was reported in an Indian who traveled back from Vienna and exposed a large number of school children in a birthday party at a city hotel. Many of the contacts of these cases have been quarantined.

These numbers are possibly an underestimate of the infected and dead due to limitations of surveillance and testing. Though the SARS-CoV-2 originated from bats, the intermediary animal through which it crossed over to humans is uncertain. Pangolins and snakes are the current suspects.

Epidemiology and Pathogenesis [ 10 , 11 ]

All ages are susceptible. Infection is transmitted through large droplets generated during coughing and sneezing by symptomatic patients but can also occur from asymptomatic people and before onset of symptoms [ 9 ]. Studies have shown higher viral loads in the nasal cavity as compared to the throat with no difference in viral burden between symptomatic and asymptomatic people [ 12 ]. Patients can be infectious for as long as the symptoms last and even on clinical recovery. Some people may act as super spreaders; a UK citizen who attended a conference in Singapore infected 11 other people while staying in a resort in the French Alps and upon return to the UK [ 6 ]. These infected droplets can spread 1–2 m and deposit on surfaces. The virus can remain viable on surfaces for days in favourable atmospheric conditions but are destroyed in less than a minute by common disinfectants like sodium hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide etc. [ 13 ]. Infection is acquired either by inhalation of these droplets or touching surfaces contaminated by them and then touching the nose, mouth and eyes. The virus is also present in the stool and contamination of the water supply and subsequent transmission via aerosolization/feco oral route is also hypothesized [ 6 ]. As per current information, transplacental transmission from pregnant women to their fetus has not been described [ 14 ]. However, neonatal disease due to post natal transmission is described [ 14 ]. The incubation period varies from 2 to 14 d [median 5 d]. Studies have identified angiotensin receptor 2 (ACE 2 ) as the receptor through which the virus enters the respiratory mucosa [ 11 ].

The basic case reproduction rate (BCR) is estimated to range from 2 to 6.47 in various modelling studies [ 11 ]. In comparison, the BCR of SARS was 2 and 1.3 for pandemic flu H1N1 2009 [ 2 ].

Clinical Features [ 8 , 15 – 18 ]

The clinical features of COVID-19 are varied, ranging from asymptomatic state to acute respiratory distress syndrome and multi organ dysfunction. The common clinical features include fever (not in all), cough, sore throat, headache, fatigue, headache, myalgia and breathlessness. Conjunctivitis has also been described. Thus, they are indistinguishable from other respiratory infections. In a subset of patients, by the end of the first week the disease can progress to pneumonia, respiratory failure and death. This progression is associated with extreme rise in inflammatory cytokines including IL2, IL7, IL10, GCSF, IP10, MCP1, MIP1A, and TNFα [ 15 ]. The median time from onset of symptoms to dyspnea was 5 d, hospitalization 7 d and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) 8 d. The need for intensive care admission was in 25–30% of affected patients in published series. Complications witnessed included acute lung injury, ARDS, shock and acute kidney injury. Recovery started in the 2nd or 3rd wk. The median duration of hospital stay in those who recovered was 10 d. Adverse outcomes and death are more common in the elderly and those with underlying co-morbidities (50–75% of fatal cases). Fatality rate in hospitalized adult patients ranged from 4 to 11%. The overall case fatality rate is estimated to range between 2 and 3% [ 2 ].

Interestingly, disease in patients outside Hubei province has been reported to be milder than those from Wuhan [ 17 ]. Similarly, the severity and case fatality rate in patients outside China has been reported to be milder [ 6 ]. This may either be due to selection bias wherein the cases reporting from Wuhan included only the severe cases or due to predisposition of the Asian population to the virus due to higher expression of ACE 2 receptors on the respiratory mucosa [ 11 ].

Disease in neonates, infants and children has been also reported to be significantly milder than their adult counterparts. In a series of 34 children admitted to a hospital in Shenzhen, China between January 19th and February 7th, there were 14 males and 20 females. The median age was 8 y 11 mo and in 28 children the infection was linked to a family member and 26 children had history of travel/residence to Hubei province in China. All the patients were either asymptomatic (9%) or had mild disease. No severe or critical cases were seen. The most common symptoms were fever (50%) and cough (38%). All patients recovered with symptomatic therapy and there were no deaths. One case of severe pneumonia and multiorgan dysfunction in a child has also been reported [ 19 ]. Similarly the neonatal cases that have been reported have been mild [ 20 ].

Diagnosis [ 21 ]

A suspect case is defined as one with fever, sore throat and cough who has history of travel to China or other areas of persistent local transmission or contact with patients with similar travel history or those with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However cases may be asymptomatic or even without fever. A confirmed case is a suspect case with a positive molecular test.

Specific diagnosis is by specific molecular tests on respiratory samples (throat swab/ nasopharyngeal swab/ sputum/ endotracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage). Virus may also be detected in the stool and in severe cases, the blood. It must be remembered that the multiplex PCR panels currently available do not include the COVID-19. Commercial tests are also not available at present. In a suspect case in India, the appropriate sample has to be sent to designated reference labs in India or the National Institute of Virology in Pune. As the epidemic progresses, commercial tests will become available.

Other laboratory investigations are usually non specific. The white cell count is usually normal or low. There may be lymphopenia; a lymphocyte count <1000 has been associated with severe disease. The platelet count is usually normal or mildly low. The CRP and ESR are generally elevated but procalcitonin levels are usually normal. A high procalcitonin level may indicate a bacterial co-infection. The ALT/AST, prothrombin time, creatinine, D-dimer, CPK and LDH may be elevated and high levels are associated with severe disease.

The chest X-ray (CXR) usually shows bilateral infiltrates but may be normal in early disease. The CT is more sensitive and specific. CT imaging generally shows infiltrates, ground glass opacities and sub segmental consolidation. It is also abnormal in asymptomatic patients/ patients with no clinical evidence of lower respiratory tract involvement. In fact, abnormal CT scans have been used to diagnose COVID-19 in suspect cases with negative molecular diagnosis; many of these patients had positive molecular tests on repeat testing [ 22 ].

Differential Diagnosis [ 21 ]

The differential diagnosis includes all types of respiratory viral infections [influenza, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, non COVID-19 coronavirus], atypical organisms (mycoplasma, chlamydia) and bacterial infections. It is not possible to differentiate COVID-19 from these infections clinically or through routine lab tests. Therefore travel history becomes important. However, as the epidemic spreads, the travel history will become irrelevant.

Treatment [ 21 , 23 ]

Treatment is essentially supportive and symptomatic.

The first step is to ensure adequate isolation (discussed later) to prevent transmission to other contacts, patients and healthcare workers. Mild illness should be managed at home with counseling about danger signs. The usual principles are maintaining hydration and nutrition and controlling fever and cough. Routine use of antibiotics and antivirals such as oseltamivir should be avoided in confirmed cases. In hypoxic patients, provision of oxygen through nasal prongs, face mask, high flow nasal cannula (HFNC) or non-invasive ventilation is indicated. Mechanical ventilation and even extra corporeal membrane oxygen support may be needed. Renal replacement therapy may be needed in some. Antibiotics and antifungals are required if co-infections are suspected or proven. The role of corticosteroids is unproven; while current international consensus and WHO advocate against their use, Chinese guidelines do recommend short term therapy with low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids in COVID-19 ARDS [ 24 , 25 ]. Detailed guidelines for critical care management for COVID-19 have been published by the WHO [ 26 ]. There is, as of now, no approved treatment for COVID-19. Antiviral drugs such as ribavirin, lopinavir-ritonavir have been used based on the experience with SARS and MERS. In a historical control study in patients with SARS, patients treated with lopinavir-ritonavir with ribavirin had better outcomes as compared to those given ribavirin alone [ 15 ].

In the case series of 99 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection from Wuhan, oxygen was given to 76%, non-invasive ventilation in 13%, mechanical ventilation in 4%, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in 3%, continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in 9%, antibiotics in 71%, antifungals in 15%, glucocorticoids in 19% and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in 27% [ 15 ]. Antiviral therapy consisting of oseltamivir, ganciclovir and lopinavir-ritonavir was given to 75% of the patients. The duration of non-invasive ventilation was 4–22 d [median 9 d] and mechanical ventilation for 3–20 d [median 17 d]. In the case series of children discussed earlier, all children recovered with basic treatment and did not need intensive care [ 17 ].

There is anecdotal experience with use of remdeswir, a broad spectrum anti RNA drug developed for Ebola in management of COVID-19 [ 27 ]. More evidence is needed before these drugs are recommended. Other drugs proposed for therapy are arbidol (an antiviral drug available in Russia and China), intravenous immunoglobulin, interferons, chloroquine and plasma of patients recovered from COVID-19 [ 21 , 28 , 29 ]. Additionally, recommendations about using traditional Chinese herbs find place in the Chinese guidelines [ 21 ].

Prevention [ 21 , 30 ]

Since at this time there are no approved treatments for this infection, prevention is crucial. Several properties of this virus make prevention difficult namely, non-specific features of the disease, the infectivity even before onset of symptoms in the incubation period, transmission from asymptomatic people, long incubation period, tropism for mucosal surfaces such as the conjunctiva, prolonged duration of the illness and transmission even after clinical recovery.

Isolation of confirmed or suspected cases with mild illness at home is recommended. The ventilation at home should be good with sunlight to allow for destruction of virus. Patients should be asked to wear a simple surgical mask and practice cough hygiene. Caregivers should be asked to wear a surgical mask when in the same room as patient and use hand hygiene every 15–20 min.

The greatest risk in COVID-19 is transmission to healthcare workers. In the SARS outbreak of 2002, 21% of those affected were healthcare workers [ 31 ]. Till date, almost 1500 healthcare workers in China have been infected with 6 deaths. The doctor who first warned about the virus has died too. It is important to protect healthcare workers to ensure continuity of care and to prevent transmission of infection to other patients. While COVID-19 transmits as a droplet pathogen and is placed in Category B of infectious agents (highly pathogenic H5N1 and SARS), by the China National Health Commission, infection control measures recommended are those for category A agents (cholera, plague). Patients should be placed in separate rooms or cohorted together. Negative pressure rooms are not generally needed. The rooms and surfaces and equipment should undergo regular decontamination preferably with sodium hypochlorite. Healthcare workers should be provided with fit tested N95 respirators and protective suits and goggles. Airborne transmission precautions should be taken during aerosol generating procedures such as intubation, suction and tracheostomies. All contacts including healthcare workers should be monitored for development of symptoms of COVID-19. Patients can be discharged from isolation once they are afebrile for atleast 3 d and have two consecutive negative molecular tests at 1 d sampling interval. This recommendation is different from pandemic flu where patients were asked to resume work/school once afebrile for 24 h or by day 7 of illness. Negative molecular tests were not a prerequisite for discharge.

At the community level, people should be asked to avoid crowded areas and postpone non-essential travel to places with ongoing transmission. They should be asked to practice cough hygiene by coughing in sleeve/ tissue rather than hands and practice hand hygiene frequently every 15–20 min. Patients with respiratory symptoms should be asked to use surgical masks. The use of mask by healthy people in public places has not shown to protect against respiratory viral infections and is currently not recommended by WHO. However, in China, the public has been asked to wear masks in public and especially in crowded places and large scale gatherings are prohibited (entertainment parks etc). China is also considering introducing legislation to prohibit selling and trading of wild animals [ 32 ].

The international response has been dramatic. Initially, there were massive travel restrictions to China and people returning from China/ evacuated from China are being evaluated for clinical symptoms, isolated and tested for COVID-19 for 2 wks even if asymptomatic. However, now with rapid world wide spread of the virus these travel restrictions have extended to other countries. Whether these efforts will lead to slowing of viral spread is not known.

A candidate vaccine is under development.

Practice Points from an Indian Perspective

At the time of writing this article, the risk of coronavirus in India is extremely low. But that may change in the next few weeks. Hence the following is recommended:

- Healthcare providers should take travel history of all patients with respiratory symptoms, and any international travel in the past 2 wks as well as contact with sick people who have travelled internationally.

- They should set up a system of triage of patients with respiratory illness in the outpatient department and give them a simple surgical mask to wear. They should use surgical masks themselves while examining such patients and practice hand hygiene frequently.

- Suspected cases should be referred to government designated centres for isolation and testing (in Mumbai, at this time, it is Kasturba hospital). Commercial kits for testing are not yet available in India.

- Patients admitted with severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome should be evaluated for travel history and placed under contact and droplet isolation. Regular decontamination of surfaces should be done. They should be tested for etiology using multiplex PCR panels if logistics permit and if no pathogen is identified, refer the samples for testing for SARS-CoV-2.

- All clinicians should keep themselves updated about recent developments including global spread of the disease.

- Non-essential international travel should be avoided at this time.

- People should stop spreading myths and false information about the disease and try to allay panic and anxiety of the public.

Conclusions

This new virus outbreak has challenged the economic, medical and public health infrastructure of China and to some extent, of other countries especially, its neighbours. Time alone will tell how the virus will impact our lives here in India. More so, future outbreaks of viruses and pathogens of zoonotic origin are likely to continue. Therefore, apart from curbing this outbreak, efforts should be made to devise comprehensive measures to prevent future outbreaks of zoonotic origin.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Most people infected with the virus will experience mild to moderate respiratory illness and recover without requiring special treatment. However, some will become seriously ill and require medical attention.

COVID-19 Archive. Diseases & Conditions. More guidance on using the COVID-19 drug Paxlovid. Published July 1, 2024. Guidelines advise unvaccinated people at high risk for severe COVID to take Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir with ritonavir) soon after symptoms begin.

Key facts. COVID-19 is a disease caused by a virus. The most common symptoms are fever, chills, and sore throat, but there are a range of others. Most people make a full recovery without needing hospital treatment. People with severe symptoms should seek medical care as soon as possible.

Countless scientists all over the world are striving to better understand SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and bringing the most relevant research findings together in one place is key to a coordinated effort. The Master Question List (MQL) does just that. The MQL organizes our collective knowledge.

In this literature review, the causative agent, pathogenesis and immune responses, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment and management of the disease, control and preventions strategies are all reviewed. Keywords: 2019-nCoV, COVID-19, Outbreak, SARS-CoV-2, Novel coronavirus. Go to:

Ongoing uncertainty, being alone, and not being able to get treatment. In many ways, the widespread challenges the COVID-19 pandemic... Rare Diseases, COVID-19. February 24, 2022.

A novel coronavirus (CoV) named ‘2019-nCoV’ or ‘2019 novel coronavirus’ or ‘COVID-19’ by the World Health Organization (WHO) is in charge of the current outbreak of pneumonia that began at the beginning of December 2019 near in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China [1–4]. COVID-19 is a pathogenic virus.

What is COVID-19? What are the symptoms of COVID-19? What happens to people who get COVID-19? Who is most at risk of severe illness from COVID-19? Are there long-term effects of COVID-19? How can we protect others and ourselves if we don't know who is infected? When should I get a test for COVID-19? What test should I get to see if I have COVID-19?

A Review of Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) There is a new public health crises threatening the world with the emergence and spread of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) or the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2).

Article. Jan 17, 2024. Boston Medical Center’s Communications Campaign to Build Confidence in Covid-19 Vaccines. S.A. Assoumou and Others. A multipronged, multilingual communications campaign...