Why Did Kodak Fail? | Kodak Bankruptcy Case Study

Yash Taneja

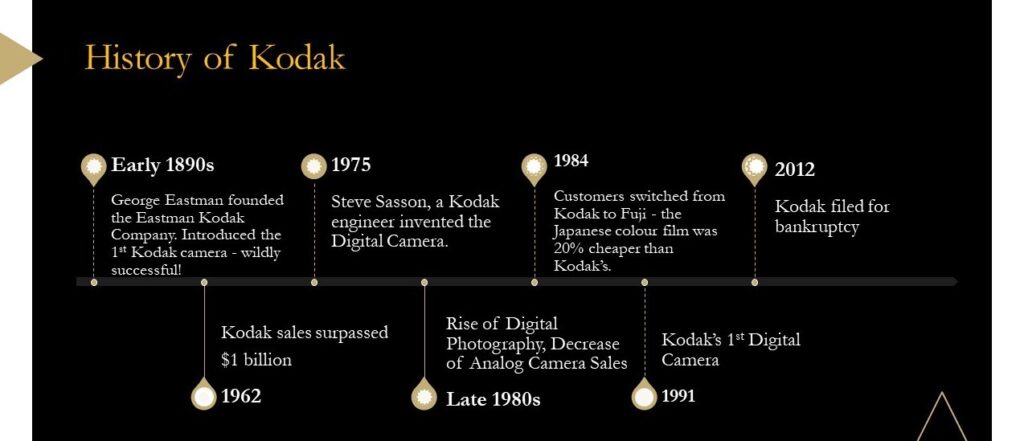

Kodak, as we know it today, was founded in the year 1888 by George Eastman as ‘The Eastman Kodak Company’ . It was the most famous name in the world of photography and videography in the 20th century. Kodak brought about a revolution in the photography and videography industries. At the time when only huge companies could access the cameras used for recording movies, Kodak enabled the availability of cameras to every household by producing equipment that was portable and affordable.

Kodak was the most dominant company in its field for almost the entire 20th century, but a series of wrong decisions killed its success. The company declared itself bankrupt in 2012. Why did Kodak, the king of photography and videography, go bankrupt? What was the reason behind Kodak's failure? Why did Kodak fail despite being the biggest name of its time? This case study answers the same.

Why Did Kodak Fail? Biggest Reason Of Kodak's Failure - Fights against Fuji Films Kodak's Bankruptcy Protection Ressurection of Kodak: Kodak in the mobile industry?

Why Did Kodak Fail?

Kodak, for many years, enjoyed unmatched success all over the world. By 1968, it had captured about 80% of the global market share in the field of photography.

Kodak adopted the 'razor and blades' business plan . The idea behind the razor-blade business plan is to first sell the razors with a small margin of profit. After buying the razor, the customers will have to purchase the consumables (the razor blades in this case) again and again; hence, sell the blades at a high-profit margin. Kodak's plan was to sell cameras at affordable prices with only a small margin for profit and then sell the consumables such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories at a high-profit margin .

Using this business model, Kodak was able to generate massive revenues and turned into a money-making machine.

As technology progressed, the use of films and printing sheets gradually came to a halt. This was due to the invention of digital cameras in 1975. However, Kodak dismissed the capabilities of the digital camera and refused to do something about it. Did you know that the inventor of the digital camera, Steven Sasson, was an electrical engineer at Kodak when he developed the technology? When Steven told the bosses at Kodak about his invention, their response was, “That’s cute, but don’t tell anyone about it. That's how you shoot yourself in the foot!"

Kodak ignored digital cameras because the business of films and paper was very profitable at that time and if these items were no longer required for photography, Kodak would be subjected to huge losses and end up closing down the factories which manufactured these items.

The idea was then implemented on a large scale by a Japanese company by the name of ‘Fuji Films’. And soon enough, many other companies started the production and sales of digital cameras, leaving Kodak way behind in the race.

This was Kodak's first mistake. The ignorance of new technology and not adapting to the changing market dynamics initiated Kodak's downfall.

List of Courses Curated By Top Marketing Professionals in the Industry

These are the courses curated by Top Marketing Professionals in the Industry who have spent 100+ Hours reviewing the Courses available in the market. These courses will help you to get a job or upgrade your skills.

Biggest Cause Of Kodak's Failure

After the digital camera became popular, Kodak spent almost 10 years arguing with Fuji Films , its biggest competitor, that the process of viewing an image captured by the digital camera was a typical process and people loved the touch and feel of a printed image. Kodak believed that the citizens of the United States of America would always choose it over Fuji Films, a foreign company.

Fuji Films and many other companies focused on gaining a foothold in the photography & videography segment rather than engaging in a verbal spat with Kodak. And once again, Kodak wasted time promoting the use of film cameras instead of emulating its competitors. It completely ignored the feedback from the media and the market . Kodak tried to convince people that film cameras were better than digital cameras and lost 10 valuable years in the process.

Kodak also lost the external funding it had during that time. People also realized that digital photography was way ahead of traditional film photography. It was cheaper than film photography and the image quality was better.

Around that time, a magazine stated that Kodak was being left behind because it was turning a blind spot to new technology. The marketing team at Kodak tried to convince the managers about the change needed in the company's core principles to achieve success. But Kodak's management committee continued to stick with its outdated idea of relying on film cameras and claimed the reporter who said the statement in the magazine did not have the knowledge to back his proposition.

Kodak failed to realize that its strategy which was effective at one point was now depriving it of success. Rapidly changing technology and market needs negated the strategy. Kodak invested its funds in acquiring many small companies, depleting the money it could have used to promote the sales of digital cameras.

When Kodak finally understood and started the sales and the production of digital cameras, it was too late. Many big companies had already established themselves in the market by then and Kodak couldn't keep pace with the big shots.

In the year 2004, Kodak finally announced it would stop the sales of traditional film cameras. This decision made around 15,000 employees (about one-fifth of the company’s workforce at that time) redundant. Before the start of the year 2011, Kodak lost its place on the S&P 500 index which lists the 500 largest companies in the United States on the basis of stock performance. In September 2011, the stock prices of Kodak hit an all-time low of $0.54 per share. The shares lost more than 50% of their value throughout that year.

Kodak's Bankruptcy Protection

By January 2012, Kodak had used up all of its resources and cash reserves. On the 19th of January in 2012, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection which resulted in the reorganization of the company. Kodak was provided with $950 million on an 18-month credit facility by the CITI group.

The credit enabled Kodak to continue functioning. To generate more revenue, some sections of Kodak were sold to other companies. Along with this, Kodak decided to stop the production and sales of digital cameras and stepped out of the world of digital photography. It shifted to the sale of camera accessories and the printing of photos.

Kodak had to sell many of its patents, including its digital imaging patents, which amounted to more than $500 million in bankruptcy protection. In September 2013, Kodak announced it had emerged from Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Ressurection of Kodak: Kodak in the mobile industry?

Celebrated camera accessory manufacturers of yesteryear, Kodak, is looking to join Chinese smartphone manufacturing giant Oppo for an upcoming flagship smartphone. This new smartphone is rumored to have 50MP dual cameras, where the cameras of the device will be modeled upon the old classic camera designs of the Kodak models.

The all-new flagship model of Oppo is designed to be a tribute to the classic Kodak camera design. The camera of this Oppo model will allegedly use the Sony IMX766 50MP sensor. Furthermore, the phone will also embed a large sensor in its ultrawide camera as well along with a 13MP telephoto lens and a 3MP microscope camera.

No other information on this matter is currently available as of September 13, 2021.

The collaborations between Android OEMs and camera makers are not something new. Yes, numerous other companies have already come together with other camera manufacturing companies like Nokia, which joined hands with German optics company Carl Zeiss earlier in 2007 to bring in the camera phone Nokia N95. This can be concluded as the first of such collaborations that the smartphone industry has seen. Numerous other collaborations happened eventually, which resulted in outstanding results. OnePlus' partnership with Hasselblad, Huawei pairing up with Leica and the recent news of Samsung's associating with Olympus are some of the significant collaborations to be mentioned.

Kodak had earlier made a leap into the smart TV industry and is ushering in success through this new move. Kodak TV India has already commissioned a plant in Hapur, Uttar Pradesh in August 2020, designed to manufacture affordable Android smart TVs for India. Furthermore, the renowned photography company is looking to invest more than Rs 500 crores during the next 3 years for making a fully automated TV manufacturing plant possible in Hapur. The company committed to this plan as part of its ‘Make in India’ initiative and will leverage its Android certification. Kodak's announcement, as it seemed, was further recharged with the Aatmanirbhar Bharat campaign launched by PM Narendra Modi in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020.

The TV industry of India imports most of its raw materials and exhibits a value addition of only about 10-12%. However, with the investment that Kodak has promised the company has aimed to increase the value-added to around 50-60%. The Hapur R&D facility will foster the manufacturing of technology-driven products and introduce numerous other lines of manufacturing aligned with the "Make in India" belief.

Super Plastronics Pvt Ltd, a Noida-based company has obtained the license from Kodak Smart TVs to produce and sell their products in India in partnership with the New-York based company and has already launched a range of smart TVs already, as of September 2021 including:

- Kodak 40FHDX7XPRO 40-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 43FHDX7XPRO 43-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 42FHDX7XPRO 42-inch Full HD Smart LED TV

- Kodak 32HDXSMART 32-inch HD ready Smart LED TV

and more. Besides, Kodak HD LED TVs were also up for sale at the lowest prices for 2020, in partnership with Flipkart and Amazon for The Big Billion Days Sale and the Great Indian Sale respectively. This sale, which took place between 16th and 21st October 2020, also included the all-new Android 7XPRO series, which starts at Rs 10999 only and is currently dubbed as the most affordable android tv in India.

Want to Work in Top Gobal & Indian Startups or Looking For Remote/Web3 Jobs - Join angel.co

Angel.co is the best Job Searching Platform to find a Job in Your Preferred domain like tech, marketing, HR etc.

What happened to Kodak?

Kodak was ousted from the market of camera and photography due to numerous missteps. Here are some insights into the same:

- The ignorance of new technology and not adapting to changing market needs initiated Kodak's downfall

- Kodak invested its funds in acquiring many small companies, depleting the money it could have used to promote the sales of digital cameras.

- Kodak wasted time promoting the use of film cameras instead of emulating its competitors. It completely ignored the feedback from the media and the market

- When Kodak finally understood and started the sales and the production of digital cameras, it was too late. Many big companies had already established themselves in the market by then and Kodak couldn't keep pace with the big shots

- In September 2011, the stock prices of Kodak hit an all-time low of $0.54 per share

- Kodak declared bankruptcy in 2012

Why did Kodak fail and what can you learn from its demise?

Kodak failed to understand that its strategy of banking on traditional film cameras (which was effective at one point) was now depriving the company of success. Rapidly changing technology and evolving market needs made the strategy obsolete.

Is Kodak still in Business?

Kodak declared itself bankrupt in 2012. Kodak's bankruptcy resulted in the formation of the Kodak Alaris company, a British organization that part-owns the Kodak brand along with the American Eastman Kodak Company.

When did Kodak go out of business?

Kodak faced its demise in 2012.

Is Kodak a good camera?

Kodak's cameras and accessories were of premium quality and the first of the choices professional photographers and others. The company was a winner in the analogue era of photography. However, the company dived down to hit the rock-bottom level.

What does Kodak do now?

Currently, Kodak provides packaging, functional printing, graphic communications, and professional services for businesses around the world. Better known for making cameras, Kodak moved into drug making and has secured a $765m (£592m) loan from the US government in 2020.

Why was Kodak so successful?

Kodak adopted the 'razor and blades' business plan. The idea here was to first sell the razors with a small margin of profit. After buying the razor, the customers will have to purchase the consumables (the razor blades in this case) again and again; hence, sell the blades at a high-profit margin. Kodak's plan was to sell cameras at affordable prices with only a small margin for profit and then sell the consumables such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories at a high-profit margin.

Must have tools for startups - Recommended by StartupTalky

- Manage your business smoothly- Google Workspace

Lenskart Business Model | How Lenskart Makes Money

Approximately 64 percent of adults around the world need corrective lenses to see clearly, according to recent studies. Envisioning a society where selecting the ideal eyewear is both a vital must and a truly enjoyable activity. This ambition has come true thanks to Lenskart, an industry pioneer. Both customers' perception

Top 22 Courier & Delivery Franchise Businesses in India

The growth of the e-commerce industry impacted the courier business. Due to more shopping in the eCommerce platform courier business is becoming one of the fastest-growing markets in India nowadays. Courier and delivery companies provide various services starting from the online courier and cargo marketplace and finishing with logistics. There

Sriharsha Majety: Visionary Behind Swiggy

We have lived in times when going out to eat meant the celebration of special occasions. Then came a period when visiting a restaurant became almost a weekend thing & now, we live in a ‘Netflix & chill’ era where we prefer food reaching us to going out to eat. And surprisingly

Top Steel Companies In India 2024

Metals are the classic driving force in the field of industrialization, with Steel holding the dominant position. For a long time, steel has contributed exceptionally to India’s economic growth. India ranks second after China in the production of crude steel. The Indian Steel Industry goes way back to the

- Data, AI, & Machine Learning

- Managing Technology

- Social Responsibility

- Workplace, Teams, & Culture

- AI & Machine Learning

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Big ideas Research Projects

- Artificial Intelligence and Business Strategy

- Responsible AI

- Future of the Workforce

- Future of Leadership

- All Research Projects

- AI in Action

- Most Popular

- The Truth Behind the Nursing Crisis

- Coaching for the Future-Forward Leader

- Measuring Culture

- Pride Month

Our summer 2024 issue highlights ways to better support customers, partners, and employees, while our special report shows how organizations can advance their AI practice.

- Past Issues

- Upcoming Events

- Video Archive

- Me, Myself, and AI

- Three Big Points

The Real Lessons From Kodak’s Decline

Eastman kodak is often mischaracterized as a company whose managers didn’t recognize soon enough that digital technology would decimate its traditional business. however, what really happened at kodak is much more complicated — and instructive..

- Leading Change

- Business Models

- Developing Strategy

- Technology Innovation Strategy

Eastman Kodak Co. is often cited as an iconic example of a company that failed to grasp the significance of a technological transition that threatened its business. After decades of being an undisputed world leader in film photography, Kodak built the first digital camera back in 1975. But then, the story goes, the company couldn’t see the fundamental shift (in its particular case, from analog to digital technology) that was happening right under its nose.

The big problem with this version of events is that it’s wrong. Moreover, it obscures some important lessons that other companies can learn from. To begin with, senior leaders at Kodak were acutely aware of the approaching storm. I know because I arrived at Kodak from Silicon Valley in mid-1997, just as digital photography was taking off. Management was constantly tracking the rate at which digital media was replacing film. But several factors made it exceedingly difficult for Kodak to shift gears and emerge with a consumer franchise that would be sustainable over the long term. Not only was a major technological change upending our competitive landscape; challenges were also affecting the ecosystem we operated in and our organizational model. Ultimately, refocusing the business with so many forces in motion proved to be impossible.

A Difficult Technology Transition

Kodak’s first challenge had to do with technology. Over the course of more than a century, Kodak and a small number of its competitors had developed and refined manufacturing processes that enabled consumers to capture and preserve images for a lifetime. Color film was an extremely complex product to manufacture. The 60-inch “wide rolls” of plastic base material had to be coated with as many as 24 layers of sophisticated chemicals: photosensitizers, dyes, couplers, and other materials deposited at precise thicknesses while traveling at 300 feet per minute. Wide rolls had to be changed over and spliced continuously in real time; the coated film had to be cut to size and packaged — all in the dark. With film, the entry barriers were high. Only two competitors — Fujifilm and Agfa-Gevaert — had enough expertise and production scale to challenge Kodak seriously.

The transition from analog to digital imaging brought several challenges. First, digital imaging was based on a general-purpose semiconductor technology platform that had nothing to do with film manufacturing — it had its own scale and learning curves.

About the Author

Willy Shih is the Robert and Jane Cizik Professor of Management Practice in Business Administration at Harvard Business School. From 1997 to 2003 he was a senior vice president at Eastman Kodak Co. and served as president of the company’s consumer digital business.

More Like This

Add a comment cancel reply.

You must sign in to post a comment. First time here? Sign up for a free account : Comment on articles and get access to many more articles.

Comments (18)

Craig mcgowan, stephen waybright, giovanbattista testolin, karl schubert, arthur weiss, julian koor, victor yodaiken, john krienke, jeffrey hardy, butch cunnings, charles h. green.

Here’s Why Kodak Failed: It Didn’t Ask The Right Question!

Remember walking past Kodak studios during your childhood? I do! Do you?

Okay if not, we often map it to those pretty (vintage?) cameras, isn’t it? Yes, it’s the Kodak we’ve known all these years.

For almost a hundred years, Kodak has led the photograph business with its innovations. But then why did it fail, being a pioneer in this industry? Is it because it didn’t make a huge push into digital, i.e saw risks of cannibalizing its strong core business?

George Eastman founded the ‘The Eastman Kodak Company’ in 1888. In the 20th century, Kodak was the go-to name when it comes to the world of photography and videography.

It indeed brought about a revolution in the filming industry! At a time when cameras were only available at big companies for recording movies, Kodak enabled the use of cameras in every household by producing cameras that were portable and affordable. Until the 1990s it was regularly rated one of the world’s five most valuable brands.

In the 1980s, the photography industry was beginning to shift towards the digital. A Kodak engineer, Steve Sasson by name, invented the 1st ever digital camera , in 1975! Kodak’s action towards the digital world seemed to be the most logical step.

Deeper Insights On Kodak’s Business Model

Kodak adopted the ‘ razor and blade ’ business model. Kodak sold cameras at much affordable prices with only a small profit margin and then sold the consumable supplies such as films, printing sheets, and other accessories with high-profit margins.

This model refers to the idea that consumers buying razors, will buy blades in a recurring manner. Kodak did benefit from having adopted this model and made huge amounts of revenue.

What did the core business revolve around? The clients would take photos with the Kodak camera and then send it to the Kodak factory where the camera’s film was developed, and photos were printed.

The company’s core product was the film and printing photos, not the camera.

Why could Kodak never become a major player in the evolving industry?

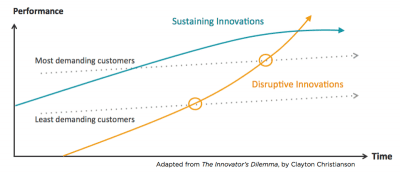

Kodak’s management failed to understand the disruption and ended up becoming a victim to the aftershocks of a disruptive change. Kodak makes a great case for cognitive biases that led the management to take irrational decisions.

Kodak created a digital camera and invested in technology. It even understood that photos would be shared online. The company did, in fact, pursue the digital photography business in a serious way.

In fact, its EasyShare line of cameras were top sellers. It also made big investments in quality printing for digital photos. Long before social media and digital media was popularized, Kodak made a purchase, acquiring a photo-sharing site called Ofoto in 2001. Instead of making Ofoto a pioneer of a new category where people could share pictures, Kodak used Ofoto to try to get more people to print digital images.

Read on to know what led Kodak to declare itself bankrupt in 2012!

Once one of the most powerful companies in the world, today the company has a market capitalization of less than $100Mn. More than 145,000 jobs were lost.

Here’s What Kodak Didn’t Do: It Didn’t Have A Careful Yet Holistic Take!

The management team at Kodak did a commendable job at realizing and thus tapping the full potential of the diverse teams of the enterprise – understanding how they interacted within the architecture of the existing technology then.

However, the research at the Kodak Research Laboratory on digital technology wasn’t appreciated as much. Executives also feared cannibalizing their core film sales and didn’t gear up to make revolutionary changes – although going digital was proving to become the trend then.

Lesson learnt – Adopt agility as an organisational strategy for development.

More than 90% of agile respondents say that their leaders provide actionable strategic guidance; that they have established a shared vision and purpose; and that people in their unit are entrepreneurial (in other words, they proactively identify and pursue opportunities to develop in their daily work)

The concept of organizational agility is catching fire as companies scurry to deal with rapid change and complexity.’ ~ McKinsey&Co 2017

Kodak Failed To Listen To The End Customers

As digital imaging was becoming dominant, Sony and Canon saw an entry and charged ahead with their digital products! Another Japanese firm called Fujifilm adopted this disruptive tech in their product portfolio and tried to diversify it too.

Competitor neglect was also a major reason that led the company to lose its Kodak moment reputation as the best in the business. Kodak’s competitors had far more superior digital cameras. Kodak simply neglected the ability and action of its rivals.

Kodak had bet on their marketing strategy, given it was resistant to the change the reshaping markets that favored the digital front of the industry brought. As Forbes highlights, the essence of marketing is first asking ‘What business are we in?’ and not ‘How do we sell more products?’!

Read: How to Create a Self Sustaining Customer Experience

Kodak did not ask the right question..

‘Its unwillingness to change its large and highly efficient ability to make-and-sell film in the face of developing digital technologies lost it the opportunity to adopt an ‘anticipate-and-lead design’ that could have secured it a leading position in the industry!’

They focused on the product and not the value they provide!

The problem was that, during its 10-year window of opportunity , Kodak did little to prepare for the disruptive revolution that followed. And by the time Kodak released its 1st digital camera in 1991, the market had multiple other major players!

Lesson learned – Companies must adapt to the requirements of the market, even if that means competing with themselves.

Kodak didn’t have an ‘enterprise mindset’

With the executives in the firm changed quite frequently, Kodak couldn’t fix strategies for a digital transformation. Since it meant being open-minded enterprise-wide.

During the years of being resistant to changes, Kodak invested its funds in acquiring numerous small companies. The company’s downfall truly began when Kodak made a late entry to the market with its 1st digital camera in 1991. Since, the drift also meant a massive restructuring of the organization leading to laying off ~ one-fifth of the workforce then.

Read: Top Brand Mantras and Principles of Brand Management

Success today requires the agility and drive to constantly rethink, reinvigorate, react, and reinvent. Bill Gates

Innovation is key. Only those who have the agility to change with the market and innovate quickly will survive. Robert Kiyosaki

Retrospective analysis of Kodak’s Case study

The information had been available, and the decision could have been made in a better way. Despite its strengths—hefty investment in research, a rigorous approach to manufacturing and good relations with its local community—Kodak had become a complacent monopolist. If we look for the logic behind these behaviors, various cognitive bias offers the best explanation.

Pattern recognition Bias

Kodak’s leadership ignored the information about the threat and highlighted the advantages of analog photography. Due to a strong confirmation bias, Kodak decided to be too dependent on their laurels and discounted the potential threat of digital photography.

Stability Bias-

Kodak had employed a lot of chemists and developers which were specialized in the analog field and had huge chemical installations for the development of the films. Kodak was the leading company in analog photography and it had invested tons of resources. Underutilization of those resources was in itself a huge sunk cost bias.

Action-Oriented Bias –

Kodak was under a huge delusion of success of its existing analog business that it missed the rise of new digital technologies. It was overconfident and over-optimistic about their own abilities.

Kodak Moments

Although film and cameras are far more sophisticated and versatile today, the fundamental principles behind Kodak’s inventions have not changed.

Kodak eventually managed to recover from bankruptcy and remains manufacturing film, with a focus on independent filmmakers .

Kodak didn’t last as it could’ve, but a Kodak moment certainly will. After all, we users owe it to the pioneers of the industry!

Interested in reading our Advanced Strategy Stories . Check out our collection.

Also check out our most loved stories below

IKEA- The new master of Glocalization in India?

IKEA is a global giant. But for India the brand modified its business strategies. The adaptation strategy by a global brand is called Glocalization

Why do some companies succeed consistently while others fail?

What is Adjacency Expansion strategy? How Nike has used it over the decades to outperform its competition and venture into segments other than shoes?

Nike doesn’t sell shoes. It sells an idea!!

Nike has built one of the most powerful brands in the world through its benefit based marketing strategy. What is this strategy and how Nike has used it?

Domino’s is not a pizza delivery company. What is it then?

How one step towards digital transformation completely changed the brand perception of Domino’s from a pizza delivery company to a technology company?

Why does Tesla’s Zero Dollar Budget Marketing work?

Touted as the most valuable car company in the world, Tesla firmly sticks to its zero dollar marketing. Then what is Tesla’s marketing strategy?

Microsoft – How to Be Cool by Making Others Cool

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said, “You join here, not to be cool, but to make others cool.” We decode the strategy powered by this statement.

I’m an engineer enthused by domains such as Consulting, Space Sciences, Finance, and Photography! A passionate writer and an ardent reader of business and brand strategies, I’m happiest while teaching and brainstorming, and love meeting new people :)

Related Posts

AI is Shattering the Chains of Traditional Procurement

Revolutionizing Supply Chain Planning with AI: The Future Unleashed

Is AI the death knell for traditional supply chain management?

Merchant-focused Business & Growth Strategy of Shopify

Business, Growth & Acquisition Strategy of Salesforce

Hybrid Business Strategy of IBM

Strategy Ingredients that make Natural Ice Cream a King

Investing in Consumer Staples: Profiting from Caution

Storytelling: The best strategy for brands

How Acquisitions Drive the Business Strategy of New York Times

Rely on Annual Planning at Your Peril

How does Vinted make money by selling Pre-Owned clothes?

N26 Business Model: Changing banking for the better

Sprinklr Business Model: Managing Unified Customer Experience

How does OpenTable make money | Business model

How does Paytm make money | Business Model

Write a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Advanced Strategies

- Brand Marketing

- Digital Marketing

- Luxury Business

- Startup Strategies

- 1 Minute Strategy Stories

- Business Or Revenue Model

- Forward Thinking Strategies

- Infographics

- Publish & Promote Your Article

- Write Article

- Testimonials

- TSS Programs

- Fight Against Covid

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and condition

- Refund/Cancellation Policy

- Master Sessions

- Live Courses

- Playbook & Guides

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

A business journal from the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

Knowledge at Wharton Podcast

What’s wrong with this picture: kodak’s 30-year slide into bankruptcy, february 1, 2012 • 15 min listen.

When new technologies change the world, some companies are caught off-guard. Others see change coming and are able to adapt in time. And then there are companies like Kodak -- which saw the future and simply couldn't figure out what to do. Kodak's Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing on January 19 culminates a long series of missteps, including a fear of introducing new technologies that would disrupt its highly profitable film business.

As Eastman Kodak begins to adapt to the challenges of bankruptcy, David A. Glocker’s company, Isoflux, is expanding — thanks to technology he developed in Kodak’s research labs. He didn’t steal anything. In fact, before he founded Isoflux with Kodak’s blessing in 1993, Glocker approached his managers at the company and suggested they market the coating process he had developed.

“In a nutshell, I went to them and said, ‘I think this is valuable technology and it’s not being commercialized…. I’d like to do that if Kodak is not interested,'” he recalls. “And they said, ‘Fine, do it.'” So he did, in his spare time, for five years while still working at Kodak, then full-time after leaving in 1998. Today, several patents and innovations later, Isoflux is a growing company in Rochester, N.Y., that coats a range of three-dimensional products, from drill bits to optical lenses to medical devices.

The technology is one of countless innovations that Kodak developed over the years but failed to successfully commercialize, the most famous being the digital camera, invented by Kodak engineer Steven Sasson in 1975. Digital technology has all but done in the iconic filmmaker. Since 2003, Kodak has closed 13 manufacturing plants and 130 processing labs, and reduced its workforce by 47,000. It now employs 17,000 worldwide, down from 63,900 less than a decade ago.

When new technologies change the world, some companies are caught off-guard. Others see change coming and are able to adapt in time. And then there are companies like Kodak — which saw the future and simply couldn’t figure out what to do. Kodak’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing on January 19 culminates the company’s 30-year slide from innovation giant to aging behemoth crippled by its own legacy.

Adapting to technological change can be especially challenging for established companies like Kodak, Wharton experts say, because entrenched leadership often finds it difficult to break old patterns that once spelled success. Kodak’s history shows that innovation alone isn’t enough; companies must also have a clear business strategy that can adapt to changing times. Without one, disruptive innovations can sink a company’s fortunes — even when the innovations are its own.

It wasn’t always this way. When Kodak founder George Eastman first began using his patented emulsion-coating machine to mass produce dry plates for photography in 1880, hewas the one being disruptive. For more than a century thereafter, Kodak dominated the world of film and popular photography, with sales surpassing $10 billion in 1981. Ringing up profit margins of around 80%, film drove the company’s expansion. Leo J. Thomas, senior vice president and Kodak’s director of research, told the Wall Street Journal in 1985: “It is very hard to find anything [with profit margins] like color photography that is legal.”

Many say film’s profitability contributed to Kodak’s demise. “I believe the single biggest mistake that Kodak made for two decades or more was the fear of introducing technologies that would disrupt the film business,” Glocker says. “There were excellent scientists and engineers at the bench level and through several layers of management who generated some of the world’s leading innovations. The company, however, was almost never willing to risk the high film margins by introducing them. The irony is that many — CCD arrays, digital X-rays, etc. — eventually did Kodak in.”

Kodak was never short on innovation, adds Glocker, but there was a disconnect between the research labs and upper management. When he joined Kodak in 1983, research was funded on what was known as Eastman’s nickel — that is, for every dollar of Kodak film sold, research got five cents. The culture in the labs was “relatively laissez-faire,” and research managers often pursued projects for a long time before management decided whether or not to bring a product to market.

From Glocker’s viewpoint, things started changing in the late 1980s when the company tried to align research more closely with business objectives. “The business units were interested in product-driven research rather than technology-driven research,” he says. He remembers one time his boss discovered a new coating technology that he presented with excitement to the business units. “The reception was cool, so to speak,” Glocker recalls. “Eventually, the funding dried up. We mothballed the equipment and went on to other things.” A few months later, the business units showed up at the lab with a competitor’s product that used the very technology they had rejected. “The business unit people came to us and said, ‘Look at this. Look at what they’re doing! Can we do this?'”

Creating and Capturing Value

Companies often have trouble managing innovation, says Wharton operations and information management professor Christian Terwiesch , director of Wharton’s Strategic R&D Managementprogram. “Either they are focused on what they currently do and seek incremental innovation, or when they talk of research, they talk about what will happen in 10 years,” he notes. “Innovations that reach a middle ground — such as envisioning new product lines in the next two to five years — are much more elusive and often don’t have a champion pushing for them in the organization.”

Another pitfall: knowing where to focus innovation. Innovation is “the match between a solution and a need, connected in a novel way,” Terwiesch says. Kodak had a choice in how it pursued innovation: If it focused on the need, it would have to find new ways to take and store photos. If it focused on the solution, it would have to find new markets for its chemical coating technologies. Kodak’s competitor, Tokyo-based Fujifilm, focused on the solution, applying its film-making expertise to LCD flat-panel screens, drugs and cosmetics. “You have to make a decision: What are you as a company? Is it understanding the need or understanding the solution?” Terwiesch asks. “These are simply two very different strategies that require very different capabilities.”

When disruptive technologies appear, there is a lot of uncertainty in the transition from old to new, according to Wharton management professor Rahul Kapoor . “The challenge is not so much in developing new technology, but rather shifting the business model in terms of the way firms create and capture value.” For years, Kodak operated under the classic razor blade model: Like blades to razors, Kodak made most of its money off film, not cameras. When the company began to shift to digital, it “thought of digital as a plug-and-play into Kodak’s existing model,” Kapoor says. The company didn’t envision making money off cameras themselves, but rather the images it assumed people would store and print. “If you look at R&D, they were superfast. In terms of the business model, they were quite the opposite.”

Kodak failed to build a strategy based on customer needs because it was afraid to cannibalize its existing business, suggests Wharton marketing professor George S. Day , co-director of Wharton’s Mack Center for Technological Innovation and author of Strategy from the Outside In. “It succumbed to inside-out thinking,” says Day — that is, trying to push forward with the existing business model instead of focusing on changing consumer needs. Accustomed to the very high film margins, the company tried to protect its existing cash flow rather than look at what the market wanted. “Long-run strategies work better if you stand in the shoes of your customers and think how you are going to solve their problems,” Day noges. “Kodak never really embraced that.”

The company’s isolation probably didn’t help, Day adds. “They had a very insular culture, sitting up there in Rochester.” The company might have been able to innovate more quickly on the digital front if it had set up a separate lab in Silicon Valley, then allowed it to grow independently and tap into the area’s tech culture and expertise. Instead, Kodak “got sucked into the Rochester environment. They recognized the threat, but tried to deal with it on their own terms.”

This view is shared by Kodak insiders as well. Some people in the company saw a need for change but they couldn’t make it happen, says John Larish, a photography writer who worked at Kodak from 1969 to 1984 as a senior markets intelligence analyst. He recalls efforts in the 1980s to drive innovation by setting up smaller spin-off companies within Kodak, but “it just didn’t work.” Venture companies in Silicon Valley are “pretty wild,” Larish adds. “In Rochester, people come to work at 8 and go home at 5.”

Kodak was invested so heavily in film technology that it became difficult to abandon, according to Robert Shanebrook, who worked at Kodak from 1969 to 2003 and has documented the process in his book, Making Kodak Film . Shanebrook began his career in Kodak’s research labs, working on the camera that Neil Armstrong used to snap photos of moon rocks. Later, he worked on a project using liquid crystals to create electronic photographs. In 1975, he moved to the company’s photographic technology division to work on black-and-white emulsion film because the company didn’t seem focused on developing digital technologies. “They told me it was going to become increasingly difficult to fund my projects in the future,” he recalls. At the time, “they weren’t particularly interested in the digital photography stuff.”

Over the years he watched digital projects lose battles for research dollars. Even though film’s market share was declining, the profit margins were still high and digital seemed an expensive, risky bet. “It would have been difficult to just give [film technology] up,” says Shanebrook. “It meant abandonment of the entire capital structure.” Kodak’s core competency was being a vertically integrated chemical manufacturer, he adds. “The core competency of being a digital camera manufacturer is electronic…. Trying to convert from being a chemical company to making digital cameras — which are like computers more than anything else — you wouldn’t expect [Kodak’s expertise] to be there.”

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to say that Kodak wasn’t extremely active in digital research, Shanebrook notes. “They were very, very aware” of digital technologies. “There were people who did nothing but watch the evolution of digital imaging. That’s why Kodak has so much intellectual property in the area.”

Refocusing the Company

In January, Kodak filed patent infringement lawsuits against Apple and Research In Motion (RIM), claiming the iPhone and BlackBerry devices infringed on Kodak’s digital imaging technology. Kodak inventors earned 19,576 U.S. patents between 1900 and 1999, and the company holds a portfolio of more than 1,000 patents in digital imaging alone. The company now hopes to sell some of those patents as part of its restructuring.

Kodak’s legacy goes beyond patents and capital equipment. In the U.S. alone, the company also has 38,000 retirees and up to $200 million per year in health care, insurance and pension obligations, says Bob Volpe, president of EKRA, a Rochester-based association of Kodak retirees. Chief executive Antonio Perez has vowed to “right-size” the company’s legacy operations, Volpe points out. “Retirees are the center of the target. We’re in the bull’s eye of the company’s efforts to reduce costs.”

Kodak could have avoided this fate if it had used the resources it earned during better times to acquire the technologies it lacked, says Wharton management professor Saikat Chaudhuri . The company made a number of acquisitions over the years, but most were “bit players” that didn’t help Kodak gain an edge. “They should have gone for one of the electronics manufacturers. It’s better to cannibalize yourself in a calibrated way than to let others do it to you.” The problem was that Kodak had built up a lot of inertia and could not react quickly. “Those very systems that serve you well and allow you to build your lead — once conditions change, they become a rigidity in and of themselves.”

On top of foot-dragging into the digital world, Kodak had become “bloated” in its heyday, and didn’t know how to scale back during the past decade, according to Wharton operations and information management professor Kartik Hosanagar . “It was never clear whether Kodak wanted to be a products company or a services company. Or a consumer company or a B2B company,” he says. “The lack of a clear strategy for digital coupled with being in too many areas led to the current situation. The confusion was also visible in its M&A work. Acquisitions have been all over the place.”

Kodak will need to streamline going forward, Hosanagar adds. It is “in too many lines of business. A struggling company like Kodak has no business being in so many areas. It needs to articulate a clear strategy and figure out whether to focus on the consumer or business segment and which specific divisions within that segment.”

Wharton management professor David Hsu agrees. The digital era pushed Kodak into “a position of reacting,” and the company seemed to lose focus. “They had reorganization efforts … [and] brought in CEO after CEO. When you have that much disruption and change,” it becomes difficult to implement a long-term strategy, Hsu says. Going forward, Kodak has to figure out what its business is going to be, and focus on that. “It’s okay to specialize in one part of the value chain…. They can’t be the best at everything. It’s a moment in time where they should put their start-up hats on and refocus the company.”

It’s business advice that Glocker of Isoflux is taking to heart. As his company has grown, other start-ups have emerged with new technologies for coating complex shapes. Glocker’s team is now exploring the possibility of investing in those technologies, even if it means using its own technology less. “It wouldn’t hurt my feelings to bring [the technologies] in house and learn how to do it.” After all, he figures, his customers don’t really care which technology he uses — they just want to get the job done. It’s a lesson he learned from watching Kodak: “Don’t assume that just because you’re not willing to do it, somebody else won’t.”

More From Knowledge at Wharton

AI Can’t Replace You at Work. Here’s Why.

The Supreme Court’s Affirmative Action Ruling: One Year Later

Paramount EVP: We Must Increase Women Leadership in Tech

Looking for more insights.

Sign up to stay informed about our latest article releases.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges and Departments

- Email and phone search

- Give to Cambridge

- Museums and collections

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Postgraduate events

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

The rise and fall of Kodak's moment

- Research home

- About research overview

- Animal research overview

- Overseeing animal research overview

- The Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body

- Animal welfare and ethics

- Report on the allegations and matters raised in the BUAV report

- What types of animal do we use? overview

- Guinea pigs

- Equine species

- Naked mole-rats

- Non-human primates (marmosets)

- Other birds

- Non-technical summaries

- Animal Welfare Policy

- Alternatives to animal use

- Further information

- Funding Agency Committee Members

- Research integrity

- Horizons magazine

- Strategic Initiatives & Networks

- Nobel Prize

- Interdisciplinary Research Centres

- Open access

- Energy sector partnerships

- Podcasts overview

- S2 ep1: What is the future?

- S2 ep2: What did the future look like in the past?

- S2 ep3: What is the future of wellbeing?

- S2 ep4 What would a more just future look like?

On a shelf in his office in Cambridge Judge Business School, Dr Kamal Munir keeps a Kodak Brownie 127. Manufactured in the 1950s, the small Bakelite camera is a powerful reminder of the rise and fall of a global brand – and of lessons other businesses would do well to learn.

Whenever I ask why a certain company that has fallen on hard times is doing badly, I always start by asking why it was successful in the first place. That is where the answer lies. Kamal Munir.

Earlier this year, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. But when Kamal's camera was made, the company bestrode the world of amateur photography – a world Kodak itself had created.

Established by George Eastman in the 1880s, by the 1950s Kodak had the lion's share of the US amateur film market. “Kodak was a company at the top of its game,” says Kamal, who has studied the Rochester-based business for more than a decade.

“Kodak controlled almost 70% of the highly lucrative US film market. Gross margins on film ran close to 70%, and its success was further underpinned by a massive distribution network and one of the strongest brands in the world. The company completely dominated its industry,” he says. “And then, in 1981, along came digital.”

Thousands of words have been written recently seeking to explain Kodak's failure. The company, all agree, was slow to adapt to digital, its executives suffered from a mentality of “perfect products”, its venture-capital arm never made big enough bets to create breakthroughs, and its leadership lacked vision and consistency.

None of this analysis, however, fully explains why digital – a technology Kodak pioneered – did for the company. Understanding that, Kamal argues, requires a deeper historical and social approach.

“Photography is very much a social activity. You can't really understand how people relate to their pictures – why people take pictures – unless you do a social analysis which is more anthropological or sociological,” he explains.

“Whenever I ask why a certain company that has fallen on hard times is doing badly, I always start by asking why it was successful in the first place. That is where the answer lies.”

For three-quarters of the twentieth century, Kodak's supreme success was not only developing a new technology – the film camera – but creating a completely new mass market.

During the nineteenth century, photography had been the exclusive preserve of a small number of professionals, with their large-format cameras and glass plates. So when Kodak invented the film camera, it needed to teach people how and what to photograph, as well as persuading them why they needed to do so.

“Kodak is the company that made photography a popular pastime around the world. It made a tremendous contribution to how we see things,” Kamal says.

The Kodak moment

Kodak's high-profile advertising campaigns established the need to preserve 'significant' occasions such as family events and holidays. These were labelled 'Kodak moments', a concept that became part of everyday life.

And it was women Kodak cast in the leading role. In its advertisements, women held the cameras, busy preserving moments of domestic bliss for posterity: “Kodak knew how to market to women. If you wanted to be seen as a caring mother and responsible housewife, then you needed to record your family's evolution and growth,” he says.

But women were only part of the story. It was they who took the photographs, but the other half of the Kodak moment required a subject – birthday parties, sporting success and, crucially, family holidays.

“Kodak also played a big role in converting travel to tourism. The idea was that if you hadn't brought back pictures from your vacation you might as well not have gone,” says Kamal. “For them, photography was all about preserving memories for posterity, photography was all about sentiment, and it was women who were doing this.”

By the 1970s, more than 60% of pictures in the US – the world's largest photography market – were being taken by women. And it was partly how men – rather than women – responded to the digital revolution that Kodak couldn't cope with.

Digital disrupted the company's equilibrium in two crucial respects. Firstly, it shifted meaning associated with cameras and secondly, digital devices allowed newcomers such as Sony to bypass one of Kodak's huge strengths – its distribution network.

The knock-on effects of this shift were enormous. Digital cameras came to be viewed as electronic gadgets, rather than pieces of purely photographic equipment. As a result, he explains: “The identification of cameras as gadgets brought about another significant change: women were no longer the main customers, men were.”

The gender shift led to the third source of disruption for the photographic industry in general, and for Kodak in particular. With digital cameras, images could be viewed on cameras, mobile phones or computers without the need for hard prints. And with women giving way to men as primary users of cameras, printing plummeted.

According to Kamal: “The people taking pictures suddenly changed, from 60% women to 70% men. Kodak didn't know how to market to men. But even if they could get them to buy, they didn't want to, because men don't print. Unlike women, they hadn't been socialised in the role of family archivist.”

Faced with such an enormous threat to its business, Kodak did what many companies do in similar circumstances – ignore the problem in the hope it goes away, and when it doesn't, deride the new-comer.

“Some things do go away – not all technology gets diffused,” he says. “When that fails, the second reaction is usually derision – it'll never take off, it's too expensive, it's too difficult, the print quality is too bad, people will never part with hard prints. When I talked to Kodak executives they would always cite the same example – if someone's house catches fire, the first thing they rescue is their photographs.”

From preserving memories to sharing experiences

Having played such a central role in creating meaning for photography, the company failed to believe that meaning had changed, from memories printed on paper to transient images shared by email or on Facebook.

“The change from preserving memories to sharing experiences, and from women to men – these were things Kodak simply couldn't handle,” says Kamal, who saw the writing on the wall when he visited the company's senior management in Rochester a decade ago. “By the end of the day I was convinced the company was not going to be around much longer.”

In 2006, Kamal sent a letter to the Financial Times , pointing out that Kodak's strategy was fundamentally flawed. “Kodak is better off taking a leaf out of Lou Gerstner’s strategy for re-inventing IBM – from a manufacturer to a service-provider,” he wrote.

“Kodak needs to disassociate itself from its traditional strengths and come to terms with the fact that this technology will be commoditised sooner or later. What they need is a new business model for an environment in which people do not ‘preserve memories’ but ‘share experiences’ ... I am afraid Mr Perez's [Kodak CEO] strategy of engulfing the consumer in the Kodak universe has a low likelihood of success."

But rather than a new business model, what Kamal had seen in Rochester was a digital imaging division under pressure from its consumer imaging counterpart, and a company unable to shake-off a corporate mindset that had developed over more than a century.

“Its focus on retail printing, investing in inkjet printing research and development, and selling sensors to mobile manufacturers – altogether, these never added up to a coherent, sustainable business model. And the digital guys were always under pressure because they were seen to be cannibalising sales of much more lucrative products,” says Kamal, who thinks Kodak should have cut the digital business loose and freed it from the Rochester mindset.

Learning from history

In his view, Kodak needed to let a new generation of users and entrepreneurs take charge – people who could embrace uncertainty and were prepared to be driven in unforeseen directions – a far cry from how the company had spent its life.

“It's important for companies to reinvent themselves. Kodak had tremendous market power – one of the things that allowed it to survive thus far. But for this kind of reinvention, where you're faced with a technological discontinuity which has little in common with what you've been doing, you need to radically alter your mindset or world-view and emerge as a completely different company. IBM is a good example of this kind of reinvention, which was a huge cultural shift and took several years. But Kodak wasn't willing to part with their legacy.”

The challenges Kodak faced are not unique, so what can other businesses learn from its failure? Clearly companies that derive a large proportion of their profit from a single product – in Kodak's case film – are more vulnerable. But having a corporate mindset open to new ideas and able to embrace uncertainty is essential.

According to Kamal: “The important things are not to tie the weight of legacy assets onto new ventures; to refrain from prolonging the life of existing product lines, while trying to create false synergies between the old and the new; and, most of all, to base strategy around users, rather than the existing business model.”

As the company approaches its 130 th birthday, what will be its legacy? Those precious family albums, perhaps, and our enduring passion for photography. But its impact could have been even greater, and longer-lasting.

“There was a time when photography was known as 'kodaking',” he concludes. “I don't think Kodak will survive. Someone might buy the brand and its assets, but Kodak is never going to be Kodak again.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence . If you use this content on your site please link back to this page.

Read this next

Moving our bodies - and mindsets

Testing the water

Imperceptible sensors made from ‘electronic spider silk’ can be printed directly on human skin

Call for safeguards to prevent unwanted ‘hauntings’ by AI chatbots of dead loved ones

Kodak Color Film.

Credit: Dok 1 from Flickr.

Search research

Sign up to receive our weekly research email.

Our selection of the week's biggest Cambridge research news sent directly to your inbox. Enter your email address, confirm you're happy to receive our emails and then select 'Subscribe'.

I wish to receive a weekly Cambridge research news summary by email.

The University of Cambridge will use your email address to send you our weekly research news email. We are committed to protecting your personal information and being transparent about what information we hold. Please read our email privacy notice for details.

- digital technology

- electronics

- entrepreneurship

- photography

- Kamal Munir

- Cambridge Judge Business School

Connect with us

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility statement

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Cambridge University Press & Assessment

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Kodak’s inability to evolve led to its demise

Try unlimited access only $1 for 4 weeks.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, ft professional, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

- Make and share highlights

- FT Workspace

- Markets data widget

- Subscription Manager

- Workflow integrations

- Occasional readers go free

- Volume discount

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Kodak’s Surprisingly Long Journey Towards Strategic Renewal: A Half Century of Exploring Digital Transformation that Culminated in Failure

62 Pages Posted: 4 Mar 2023

Natalya Vinokurova

Lehigh University

Rahul Kapoor

University of Pennsylvania - Management Department

Date Written: February 28, 2023

Kodak’s failure to transition from film to digital technology has become a canonical example of a dominant incumbent failing in the face of an industry transition. In this paper, we undertake a systematic study of Kodak’s decision-making from its earliest efforts in digital technology in the 1960s through its bankruptcy in 2012. Our analysis of Kodak’s decision-making over the half-century leading up to its bankruptcy finds limited evidence of inertia and extensive evidence of strategic renewal efforts. Kodak committed substantial resources to R&D, commercialized multiple digital products through dedicated business units, incubated start-ups, acquired firms with promising imaging technologies, diversified into adjacent fields, and undertook senior leadership changes, yet it still failed. In investigating why, we observe a pattern of costly exploratory search under conditions of high aspirations and persistent uncertainty surrounding the emergence of digital technology. This uncertainty contributed to Kodak’s efforts falling short of aspirations and limited learning to inform future attempts. These shortfalls led to the search narrowing over time under changing leadership regimes. Our findings highlight the value of viewing the problem of incumbency not only as one of inertia, but also as one of costly exploratory search under conditions of high aspirations and environmental uncertainty.

Keywords: Technological change, Inertia, Adaptation, Strategic renewal, Decision-making, Eastman Kodak Company

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Natalya Vinokurova (Contact Author)

Lehigh university ( email ).

621 Taylor Street Bethlehem, PA 18015 United States

University of Pennsylvania - Management Department ( email )

The Wharton School Philadelphia, PA 19104-6370 United States

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, the wharton school, university of pennsylvania research paper series.

Subscribe to this free journal for more curated articles on this topic

Development of Innovation eJournal

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Economics of Innovation eJournal

Public sector strategy & organizational behavior ejournal, industrial & manufacturing engineering ejournal.

- Follow PetaPixel on YouTube

- Follow PetaPixel on Facebook

- Follow PetaPixel on Twitter

- Follow PetaPixel on Instagram

Why Kodak Died and Fujifilm Thrived: A Tale of Two Film Companies

The Kodak moment is gone, but today Fujifilm thrives after a massive reorganization. Here is a detailed analysis based on firsthand accounts from top executives and factual financial data to understand how and why the destinies of two similar companies went in opposite directions.

The Situation before the Film Crisis: A Profitable and Secure Market

Even though Kodak and Fujifilm produced cameras, their core business was centered on film and post-processing sales. According to Forbes , Kodak “gladly gave away cameras in exchange for getting people hooked on paying to have their photos developed — yielding Kodak a nice annuity in the form of 80% of the market for the chemicals and paper used to develop and print those photos.”

Inside Kodak, this was known as the “silver halide” strategy named after the chemical compounds in its film. It was a fantastic success story. This business strategy was similar to Gillette’s or that of printer manufacturers: give away razors or printers to make money on blades and ink cartridges. Indeed, Fujifilm introduced the disposable 35mm camera to the masses in 1986 before being joined by Kodak in 1988. Film was everything to them.

In 2000 , just before the digital transition, sales related to film accounted for 72% of Kodak revenue and 66% of its operating income against 60% and 66% for Fujifilm.

Photo film is made of a fine-tuned combination of various technologies and requires a careful manufacturing process. A quick look at the cross-section of a color film reveals that on a clear base film (TAC), there are 20 evenly coated layers, each sensitive to the three primary colors of light, red, blue, and green. Each of these overlapping layers is only one micron thick.

The CEO of Fujifilm, Mr. Shigetaka Komori explains in his book that “in addition to film formation and high-precision coating, there are grain formation, function polymer, nano-dispersion, functional molecules, and redox control (oxidation of the molecule). Inherent in all these is very precise quality control.”

Willy Shih, former vice president of Kodak (1997-2003) also confirms that “Color film was an extremely complex product to manufacture.” The film roll “had to be coated with as many as 24 layers of sophisticated chemicals: photosensitizers, dyes, couplers, and other materials deposited at precise thicknesses while traveling at 300 feet per minute. Wide rolls had to be changed over and spliced continuously in real-time; the coated film had to be cut to size and packaged, all in the dark.”

Mr. Komori remembers that back in the day, there were at one time 30 or 40 producers of monochrome photo film in existence globally but many of these companies were confronted by an insurmountable technical wall with the advent of color film. “With film, the entry barriers were high. Only two competitors, Fujifilm and Agfa-Gevaert, had enough expertise and production scale to challenge Kodak seriously,” Shih said.

The film business was relatively secure and profitable. The market was animated for decades by the Fuji-Kodak duel, while Agfa and Konica played in the second and third leagues. Each company had prominent shares in their domestic market which generated a continuous and safe stream of revenue despite temporary price wars like the one launched by Fuji against Kodak in the 80s and 90s.

The Consequences of the Digital Revolution: A “Crappy” and Vanishing Business

In 2001, the film sales peaked worldwide but as the president of Fujifilm remembers: “a peak always conceals a treacherous valley.” First, the market began shrinking very slowly, then picked up speed and finally plunged at the rate of twenty or thirty percent a year. In 2010, worldwide demand for photographic film had fallen to less than a tenth of what it had been only ten years before.

But, initially, the market didn’t vanish, it changed. Following the internet and personal computer democratization of the 90s, consumers started to purchase digital cameras. Unfortunately, for film manufacturers, the transition from analog to digital imaging represented tremendous difficulties. First, the semiconductor technology platform had nothing to do with film manufacturing.

But most importantly, as the former vice president of Kodak explains : “The broad applicability of the technology platform meant that a good engineer could buy all the building blocks and put together a camera. These building blocks abstracted almost all the technology required, so you no longer needed a lot of experience and specialized skills. Suppliers selling components offered the technology to anyone who would pay, and there were few entry barriers.”

In other words, the digital era was the exact opposite of the comfortable “silver halide” business model where a few players shared a secured market with good margins. The core business of film and post-processing disappeared, but the commercialization of digital cameras didn’t make up for the loss. In 2006, the CEO of Kodak, Antonio Perez was quoted calling digital cameras a “crappy business.”

Why? Because all of a sudden, Kodak and Fujifilm were forced to leave their quasi-duopoly and compete against dozens of companies in the low-margin business of digital cameras. Unlike color films, anyone could put a sensor and processor together and introduce a product to the market. And that’s precisely what happened. As Yukio Shohtoku, retired executive vice president of Panasonic said to his Kodak counterpart, “Modularization makes consumer products, our consumer products, a commodity.”

This explains how a California surfer could appear out of nowhere and take the consumer video recorder market by storm as the CEO of GoPro did before being overrun, in turn, by cheaper Chinese electronics manufacturers.

A quick look at Kodak’s finance shows this situation. In the early 2000s, Kodak managed to maintain its level of sales, but the profits of the group plunged into the negative zone. In the ’90s, Kodak Sales were oscillating between 13 and 15 billion with average net earnings of 5-10%. The company generated $1.4 billion in profit in 2000 and $800 million in 2002. After that, the finance of the Rochester-based corporation suffers a long agony leading to a bankruptcy filing in 2012. The drop is especially sharp after 2006.

The issue was not about selling cameras, Kodak sold plenty of digital cameras . In 2005, Kodak captured 21.3% of the US market share and emerged first in the digital camera segment against its Japanese rivals. That year, the US group managed to grow its sales by 15%.

Unfortunately, the sales were not as good worldwide. Kodak reached an early lead in the market and had a 27% market share by 1999. But that slipped to 15% by 2003 and 7% by 2010, as Kodak ceded ground to Canon, Nikon and others.

The main problem was that Kodak was not making money with digital cameras. It was bleeding cash. According to a Harvard case study , it lost $60 for every digital camera it sold by 2001.

This issue appears clearly in the financial reports. Whereas in 2000 Kodak made an operating income of $1.4 billion out of $10.2 billion in sales in the photography division, the profitability quickly vanished afterward.

In 2006, the official annual report started to separate the sales figure from the digital and film segment. As we can see in the chart below, Kodak initially maintained a somehow decent level of revenue from the photography division. It even managed to replace declining film sales with digital imaging revenue, but this activity was making losses. Eventually, Kodak had to file for bankruptcy in 2012. The previous year, film sales only generated an operating income of $34 million while the digital camera division lost ten times that ($349 million loss).

The big picture was not better for Fujifilm as it faced the same storm as its American competitor. The president of Fujifilm remembers that “what we could not account for in our projections was the speed of the digital onslaught. The photographic film market had shrunk much faster than we expected.” Between 2005 and 2010 , the sales of color film declined from 156 billion yen to 33 billion while the photo finishing segment shrunk from ¥89 billion to ¥33 billion. Not only did the Japanese company overcome the crisis, but it thrived in this challenging environment. How?

How Did Fuji Overcome the Crisis and Thrive?

The critical element in Fujifilm’s success is diversification. In 2010, the film market dropped to less than 10% compared to 2000. But Fujifilm, which once made 60% of its sales with film, diversified successfully and managed to grow its revenue by 57% over this ten years period while Kodak sales fell by 48%.

Faced with a sharp decline in sales from its cash cow product Fujifilm acted swiftly and changed its business through innovation and external growth. Under the decisive grip of Shigetaka Komori, appointed president in 2000, Fujifilm quickly carried out massive reforms. In 2004, Komori came up with a six-year plan called VISION 75 in reference to the 75th anniversary of the group. The goal was simple and consisted of “saving Fujifilm from disaster and ensuring its viability as a leading company with sales of 2 or 3 trillion yen a year.”

First, the management restructured its film business by downscaling the production lines and closing redundant facilities. In the meantime, the research and development departments moved to a newly built facility to unify the research efforts and promote better communication and innovation culture among engineers. But realizing that the digital camera business would not replace the silver halide strategy due to the low profitability of his sector, Fujifilm performed a massive diversification based on capabilities and innovation.

Even before launching the VISION 75 plan, the president ordered the head of R&D to take inventory of Fujifilm technologies and compared them with the demand of the international market. After a year and a half of technological auditing, the R&D team came up with a chart listing the all existing in-house technologies that could match future markets.

The president saw that “Fujifilm technologies could be adapted for emerging markets such as pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and highly functional materials.” For instance, the company was able to predict the boom of LCD screens and invested heavily in this market. Leveraging the photo film technologies, the engineer created FUJITAC, a variety of high-performance films essential for making LCD panels for TV, computers, and smartphones. Today, FUJITAC owns 70% of the market for protective LCD polarizer films.

The company also targeted unexpected markets like cosmetics. The rationale behind cosmetics comes from 70 years of experience in gelatin, the chief ingredient of photo film which is derived from collagen. Human skin is seventy percent collagen, to which it owes its sheen and elasticity. Fujifilm also possessed deep know-how in oxidation, a process connected both to the aging of human skin and to the fading of photos over time. Thus, Fujifilm launched a makeup line in 2007 called Astalift.

When promising technologies that could match growing markets didn’t exist internally, Fujifilm proceeded by merger and acquisition (M&A). To develop new business ventures, the group made active use of M&A. By acquiring companies that already penetrated a market and combine their assets with Fujifilm’s expertise, the Japanese firm could release new products to the market quickly and easily.

Based on technological synergies, it acquired Toyoma Chemical in 2008 to enter the drug business. Delving further into the healthcare segment, Fujifilm also brought a radiopharmaceutical company now called Fujifilm RI Pharma. It also reinforced its position in existing joint ventures such as Fuji-Xerox which became a consolidated subsidiary in 2001 after Fujifilm purchased an additional 25% share in this partnership.

In 2010, nine years after the peak of film sales, Fujifilm was a new company. Whereas in 2000, 60% of its sales and two-thirds of the profit came from the film ecosystem, in 2010 the Imaging division accounted for less than 16% of the revenue. Fujifilm managed to ride out of the storm via a massive restructuring and diversification strategy.

Why Did Kodak Fail?

A lot has been said about Kodak’s failure to reform itself. The usual story describes a mummified company stuck in the analog era and incapable of adapting to the digital world. Some explained that Kodak suffered from Myopia and didn’t see the digital camera coming while other said that complacency was the cause of the problem since the senior management refused to accept the inevitable even though they were aware of the incoming digital Tsunami.

While this narrative carries a certain truth, it is simplified and incomplete. As mentioned previously, Kodak did build a decent range of digital cameras and managed to rank first in US sales for a while in the early 2000s. Historically, Kodak was the inventor of the digital camera when it developed this technology back in 1975. The Rochester company poured billions of dollars into the digital R&D, and like Fujifilm, performed a massive downscaling effort that also cost billions .

According to the Harvard Business Review : “CEO George Fisher (1993-1999) knew that digital photography might eventually invade, or even replace, Kodak’s core business. Doubtless, he and other senior executives were tempted to ignore it. To their credit, they resisted that temptation. Fisher rallied the troops and aggressively invested more than $2 billion in R&D for digital imaging.” An effort pursued by the next CEO Dan Carp who vowed to invest two-thirds of the company’s research and development budget on digital projects.