Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- General Education Courses

- School of Business

- School of Design

- School of Education

- School of Health Sciences

- School of Justice Studies

- School of Nursing

- School of Technology

- CBE Student Guide

- Online Library

- Ask a Librarian

- Learning Express Library

- Interlibrary Loan Request Form

- Library Staff

- Databases A-to-Z

- Articles by Subject

- Discovery Search

- Publication Finder

- Video Databases

- NoodleTools

- Library Guides

- Course Guides

- Writing Lab

- Rasmussen Technical Support (PSC)

- Copyright Toolkit

- Faculty Toolkit

- Suggest a Purchase

- Refer a Student Tutor

- Live Lecture/Peer Tutor Scheduler

- Faculty Interlibrary Loan Request Form

- Professional Development Databases

- Publishing Guide

- Professional Development Guides (AAOPD)

- Literature Review Guide

- Back to Research Help

The Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- Plan Your Literature Review

- Identify a Research Gap

- Define Your Research Question

- Search the Literature

- Analyze Your Research Results

- Manage Research Results

- Write the Literature Review

What is a Literature Review? What is its purpose?

The purpose of a literature review is to offer a comprehensive review of scholarly literature on a specific topic along with an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of authors' arguments . In other words, you are summarizing research available on a certain topic and then drawing conclusions about researchers' findings. To make gathering research easier, be sure to start with a narrow/specific topic and then widen your topic if necessary.

A thorough literature review provides an accurate description of current knowledge on a topic and identifies areas for future research. Are there gaps or areas that require further study and exploration? What opportunities are there for further research? What is missing from my collection of resources? Are more resources needed?

It is important to note that conclusions described in the literature you gather may contradict each other completely or in part. Recognize that knowledge creation is collective and cumulative. Current research is built upon past research findings and discoveries. Research may bring previously accepted conclusions into question. A literature review presents current knowledge on a topic and may point out various academic arguments within the discipline.

What a Literature Review is not

- A literature review is not an annotated bibliography . An annotated bibliography provides a brief summary, analysis, and reflection of resources included in the bibliography. Often it is not a systematic review of existing research on a specific subject. That said, creating an annotated bibliography throughout your research process may be helpful in managing the resources discovered through your research.

- A literature review is not a research paper . A research paper explores a topic and uses resources discovered through the research process to support a position on the topic. In other words, research papers present one side of an issue. A literature review explores all sides of the research topic and evaluates all positions and conclusions achieved through the scientific research process even though some conclusions may conflict partially or completely.

From the Online Library

SAGE Research Methods is a web-based research methods tool that covers quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. Researchers can explore methods and concepts to help design research projects, understand a particular method or identify a new method, and write up research. Sage Research Methods focuses on methodology rather than disciplines, and is of potential use to researchers from the social sciences, health sciences and other research areas.

- Sage Research Methods Project Planner - Reviewing the Literature View the resources and videos for a step-by-step guide to performing a literature review.

The Literature Review: Step by Step

Follow this step-by-step process by using the related tabs in this Guide.

- Define your Research question

- Analyze the material you’ve found

- Manage the results of your research

- Write your Review

Getting Started

Consider the following questions as you develop your research topic, conduct your research, and begin evaluating the resources discovered in the research process:

- What is known about the subject?

- Are there any gaps in the knowledge of the subject?

- Have areas of further study been identified by other researchers that you may want to consider?

- Who are the significant research personalities in this area?

- Is there consensus about the topic?

- What aspects have generated significant debate on the topic?

- What methods or problems were identified by others studying in the field and how might they impact your research?

- What is the most productive methodology for your research based on the literature you have reviewed?

- What is the current status of research in this area?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How detailed? Will it be a review of ALL relevant material or will the scope be limited to more recent material, e.g., the last five years.

- Are you focusing on methodological approaches; on theoretical issues; on qualitative or quantitative research?

What is Academic Literature?

What is the difference between popular and scholarly literature?

To better understand the differences between popular and scholarly articles, comparing characteristics and purpose of the publications where these articles appear is helpful.

Popular Article (Magazine)

- Articles are shorter and are written for the general public

- General interest topics or current events are covered

- Language is simple and easy to understand

- Source material is not cited

- Articles often include glossy photographs, graphics, or visuals

- Articles are written by the publication's staff of journalists

- Articles are edited and information is fact checked

Examples of magazines that contain popular articles:

Scholarly Article (Academic Journal)

- Articles are written by scholars and researchers for academics, professionals, and experts in the field

- Articles are longer and report original research findings

- Topics are narrower in focus and provide in-depth analysis

- Technical or scholarly language is used

- Source material is cited

- Charts and graphs illustrating research findings are included

- Many are "peer reviewed" meaning that panels of experts review articles submitted for publication to ensure that proper research methods were used and research findings are contributing something new to the field before selecting for publication.

Examples of academic journals that contain scholarly articles:

Define your research question

Selecting a research topic can be overwhelming. Consider following these steps:

1. Brainstorm research topic ideas

- Free write: Set a timer for five minutes and write down as many ideas as you can in the allotted time

- Mind-Map to explore how ideas are related

2. Prioritize topics based on personal interest and curiosity

3. Pre-research

- Explore encyclopedias and reference books for background information on the topic

- Perform a quick database or Google search on the topic to explore current issues.

4. Focus the topic by evaluating how much information is available on the topic

- Too much information? Consider narrowing the topic by focusing on a specific issue

- Too little information? Consider broadening the topic

5. Determine your purpose by considering whether your research is attempting to:

- further the research on this topic

- fill a gap in the research

- support existing knowledge with new evidence

- take a new approach or direction

- question or challenge existing knowledge

6. Finalize your research question

NOTE: Be aware that your initial research question may change as you conduct research on your topic.

Searching the Literature

Research on your topic should be conducted in the academic literature. The Rasmussen University Online Library contains subject-focused databases that contain the leading academic journals in your programmatic area.

Consult the Using the Online Library video tutorials for information about how to effectively search library databases.

Watch the video below for tips on how to create a search statement that will provide relevant results

Need help starting your research? Make a research appointment with a Rasmussen Librarian .

TIP: Document as you research. Begin building your references list using the citation managers in one of these resources:

- APA Academic Writer

Recommended programmatic databases include:

Data Science

Coverage includes computer engineering, computer theory & systems, research and development, and the social and professional implications of new technologies. Articles come from more than 1,900 academic journals, trade magazines, and professional publications.

Provides access to full-text peer-reviewed journals, transactions, magazines, conference proceedings, and published standards in the areas of electrical engineering, computer science, and electronics. It also provides access to the IEEE Standards Dictionary Online. Full-text available.

Computing, telecommunications, art, science and design databases from ProQuest.

Healthcare Management

Articles from scholarly business journals back as far as 1886 with content from all disciplines of business, including marketing, management, accounting, management information systems, production and operations management, finance, and economics. Contains 55 videos from the Harvard Faculty Seminar Series, on topics such as leadership, sustaining competitive advantage, and globalization. To access the videos, click "More" in the blue bar at the top. Select "Images/ Business Videos." Uncheck "Image Quick View Collection" to indicate you only wish to search for videos. Enter search terms.

Provides a truly comprehensive business research collection. The collection consists of the following databases and more: ABI/INFORM Complete, ProQuest Entrepreneurship, ProQuest Accounting & Tax, International Bibliography of Social Sciences (IBSS), ProQuest Asian Business and Reference, and Banking Information Source.

The definitive research tool for all areas of nursing and allied health literature. Geared towards the needs of nurses and medical professionals. Covers more than 750 journals from 1937 to present.

HPRC provides information on the creation, implementation and study of health care policy and the health care system. Topics covered include health care administration, economics, planning, law, quality control, ethics, and more.

PolicyMap is an online mapping site that provides data on demographics, real estate, health, jobs, and other areas across the U.S. Access and visualize data from Census and third-party records.

Human Resources

Articles from all subject areas gathered from more than 11,000 magazines, journals, books and reports. Subjects include astronomy, multicultural studies, humanities, geography, history, law, pharmaceutical sciences, women's studies, and more. Coverage from 1887 to present. Start your research here.

Cochrane gathers and summarizes the best evidence from research to help you make informed choices about treatments. Whether a doctor or nurse, patient, researcher or student, Cochrane evidence provides a tool to enhance your healthcare knowledge and decision making on topics ranging from allergies, blood disorders, and cancer, to mental health, pregnancy, urology, and wounds.

Health sciences, biology, science, and pharmaceutical information from ProQuest. Includes articles from scholarly, peer-reviewed journals, practical and professional development content from professional journals, and general interest articles from magazines and newspapers.

Joanna Briggs Institute Academic Collection contains evidence-based information from across the globe, including evidence summaries, systematic reviews, best practice guidelines, and more. Subjects include medical, nursing, and healthcare specialties.

Comprehensive source of full-text articles from more than 1,450 scholarly medical journals.

Articles from more than 35 nursing journals in full text, searchable as far back as 1995.

Analyzing Your Research Results

You have completed your research and discovered many, many academic articles on your topic. The next step involves evaluating and organizing the literature found in the research process.

As you review, keep in mind that there are three types of research studies:

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- Mixed Methods

Consider these questions as you review the articles you have gathered through the research process:

1. Does the study relate to your topic?

2. Were sound research methods used in conducting the study?

3. Does the research design fit the research question? What variables were chosen? Was the sample size adequate?

4. What conclusions were drawn? Do the authors point out areas for further research?

Reading Academic Literature

Academic journals publish the results of research studies performed by experts in an academic discipline. Articles selected for publication go through a rigorous peer-review process. This process includes a thorough evaluation of the research submitted for publication by journal editors and other experts or peers in the field. Editors select articles based on specific criteria including the research methods used, whether the research contributes new findings to the field of study, and how the research fits within the scope of the academic journal. Articles selected often go through a revision process prior to publication.

Most academic journal articles include the following sections:

- Abstract (An executive summary of the study)

- Introduction (Definition of the research question to be studied)

- Literature Review (A summary of past research noting where gaps exist)

- Methods (The research design including variables, sample size, measurements)

- Data (Information gathered through the study often displayed in tables and charts)

- Results (Conclusions reached at the end of the study)

- Conclusion (Discussion of whether the study proved the thesis; may suggest opportunities for further research)

- Bibliography (A list of works cited in the journal article)

TIP: To begin selecting articles for your research, read the highlighted sections to determine whether the academic journal article includes information relevant to your research topic.

Step 1: Skim the article

When sorting through multiple articles discovered in the research process, skimming through these sections of the article will help you determine whether the article will be useful in your research.

1. Article title and subject headings assigned to the article

2. Abstract

3. Introduction

4. Conclusion

If the article fits your information need, go back and read the article thoroughly.

TIP: Create a folder on your computer to save copies of articles you plan to use in your thesis or research project. Use NoodleTools or APA Academic Writer to save APA references.

Step 2: Determine Your Purpose

Think about how you will evaluate the academic articles you find and how you will determine whether to include them in your research project. Ask yourself the following questions to focus your search in the academic literature:

- Are you looking for an overview of a topic? an explanation of a specific concept, idea, or position?

- Are you exploring gaps in the research to identify a new area for academic study?

- Are you looking for research that supports or disagrees with your thesis or research question?

- Are you looking for examples of a research design and/or research methods you are considering for your own research project?

Step 3: Read Critically

Before reading the article, ask yourself the following:

- What is my research question? What position am I trying to support?

- What do I already know about this topic? What do I need to learn?

- How will I evaluate the article? Author's reputation? Research design? Treatment of topic?

- What are my biases about the topic?

As you read the article make note of the following:

- Who is the intended audience for this article?

- What is the author's purpose in writing this article?

- What is the main point?

- How was the main point proven or supported?

- Were scientific methods used in conducting the research?

- Do you agree or disagree with the author? Why?

- How does this article compare or connect with other articles on the topic?

- Does the author recommend areas for further study?

- How does this article help to answer your research question?

Managing your Research

Tip: Create APA references for resources as you discover them in the research process

Use APA Academic Writer or NoodleTools to generate citations and manage your resources. Find information on how to use these resources in the Citation Tools Guide .

Writing the Literature Review

Once research has been completed, it is time to structure the literature review and begin summarizing and synthesizing information. The following steps may help with this process:

- Chronological

- By research method used

- Explore contradictory or conflicting conclusions

- Read each study critically

- Critique methodology, processes, and conclusions

- Consider how the study relates to your topic

- Description of public health nursing nutrition assessment and interventions for home‐visited women. This article provides a nice review of the literature in the article introduction. You can see how the authors have used the existing literature to make a case for their research questions. more... less... Horning, M. L., Olsen, J. M., Lell, S., Thorson, D. R., & Monsen, K. A. (2018). Description of public health nursing nutrition assessment and interventions for home‐visited women. Public Health Nursing, 35(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12410

- Improving Diabetes Self-Efficacy in the Hispanic Population Through Self-Management Education Doctoral papers are a good place to see how literature reviews can be done. You can learn where they searched, what search terms they used, and how they decided which articles were included. Notice how the literature review is organized around the three main themes that came out of the literature search. more... less... Robles, A. N. (2023). Improving diabetes self-efficacy in the hispanic population through self-management education (Order No. 30635901). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global: The Sciences and Engineering Collection. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/improving-diabetes-self-efficacy-hispanic/docview/2853708553/se-2

- Exploring mediating effects between nursing leadership and patient safety from a person-centred perspective: A literature review Reading articles that publish the results of a systematic literature review is a great way to see in detail how a literature review is conducted. These articles provide an article matrix, which provides you an example of how you can document information about the articles you find in your own search. To see more examples, include "literature review" or "systematic review" as a search term. more... less... Wang, M., & Dewing, J. (2021). Exploring mediating effects between nursing leadership and patient safety from a person‐centred perspective: A literature review. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(5), 878–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13226

Database Search Tips

- Boolean Operators

- Keywords vs. Subjects

- Creating a Search String

- Library databases are collections of resources that are searchable, including full-text articles, books, and encyclopedias.

- Searching library databases is different than searching Google. Best results are achieved when using Keywords linked with Boolean Operators .

- Applying Limiters such as full-text, publication date, resource type, language, geographic location, and subject help to refine search results.

- Utilizing Phrases or Fields , in addition to an awareness of Stop Words , can focus your search and retrieve more useful results.

- Have questions? Ask a Librarian

Boolean Operators connect keywords or concepts logically to retrieve relevant articles, books, and other resources. There are three Boolean Operators:

Using AND

- Narrows search results

- Connects two or more keywords/concepts

- All keywords/concepts connected with "and" must be in an article or resource to appear in the search results list

Venn diagram of the AND connector

Example: The result list will include resources that include both keywords -- "distracted driving" and "texting" -- in the same article or resource, represented in the shaded area where the circles intersect (area shaded in purple).

- Broadens search results ("OR means more!")

- Connects two or more synonyms or related keywords/concepts

- Resources appearing in the results list will include any of the terms connected with the OR connector

Venn diagram of the OR connector

Example: The result list will include resources that include the keyword "texting" OR the keyword "cell phone" (entire area shaded in blue); either is acceptable.

- Excludes keywords or concepts from the search

- Narrows results by removing resources that contain the keyword or term connected with the NOT connector

- Use sparingly

Venn diagram of the NOT connector

Example: The result list will include all resources that include the term "car" (green area) but will exclude any resource that includes the term "motorcycle" (purple area) even though the term car may be present in the resource.

A library database searches for keywords throughout the entire resource record including the full-text of the resource, subject headings, tags, bibliographic information, etc.

- Natural language words or short phrases that describe a concept or idea

- Can retrieve too few or irrelevant results due to full-text searching (What words would an author use to write about this topic?)

- Provide flexibility in a search

- Must consider synonyms or related terms to improve search results

- TIP: Build a Keyword List

Example: The keyword list above was developed to find resources that discuss how texting while driving results in accidents. Notice that there are synonyms (texting and "text messaging"), related terms ("cell phones" and texting), and spelling variations ("cell phone" and cellphone). Using keywords when searching full text requires consideration of various words that express an idea or concept.

- Subject Headings

- Predetermined "controlled vocabulary" database editors apply to resources to describe topical coverage of content

- Can retrieve more precise search results because every article assigned that subject heading will be retrieved.

- Provide less flexibility in a search

- Can be combined with a keyword search to focus search results.

- TIP: Consult database subject heading list or subject headings assigned to relevant resources

Example 1: In EBSCO's Academic Search Complete, clicking on the "Subject Terms" tab provides access to the entire subject heading list used in the database. It also allows a search for specific subject terms.

Example 2: A subject term can be incorporated into a keyword search by clicking on the down arrow next to "Select a Field" and selecting "Subject Terms" from the dropdown list. Also, notice how subject headings are listed below the resource title, providing another strategy for discovering subject headings used in the database.

When a search term is more than one word, enclose the phrase in quotation marks to retrieve more precise and accurate results. Using quotation marks around a term will search it as a "chunk," searching for those particular words together in that order within the text of a resource.

"cell phone"

"distracted driving"

"car accident"

TIP: In some databases, neglecting to enclose phrases in quotation marks will insert the AND Boolean connector between each word resulting in unintended search results.

Truncation provides an option to search for a root of a keyword in order to retrieve resources that include variations of that word. This feature can be used to broaden search results, although some results may not be relevant. To truncate a keyword, type an asterisk (*) following the root of the word.

For example:

Library databases provide a variety of tools to limit and refine search results. Limiters provide the ability to limit search results to resources having specified characteristics including:

- Resource type

- Publication date

- Geographic location

In both the EBSCO and ProQuest databases, the limiting tools are located in the left panel of the results page.

EBSCO ProQuest

The short video below provides a demonstration of how to use limiters to refine a list of search results.

Each resource in a library database is stored in a record. In addition to the full-text of the resources, searchable Fields are attached that typically include:

- Journal title

- Date of Publication

Incorporating Fields into your search can assist in focusing and refining search results by limiting the results to those resources that include specific information in a particular field.

In both EBSCO and ProQuest databases, selecting the Advanced Search option will allow Fields to be included in a search.

For example, in the Advanced Search option in EBSCO's Academic Search Complete database, clicking on the down arrow next to "Select a Field" provides a list of fields that can be searched within that database. Select the field and enter the information in the text box to the left to use this feature.

Stop words are short, commonly used words--articles, prepositions, and pronouns-- that are automatically dropped from a search. Typical stop words include:

In library databases, a stop word will not be searched even if it is included in a phrase enclosed in quotation marks. In some instances, a word will be substituted for the stop word to allow for the other words in the phrase to be searched in proximity to one another within the text of the resource.

For example, if you searched company of America, your result list will include these variatons:

- company in America

- company of America

- company for America

Creating an Search String

This short video demonstrates how to create a search string -- keywords connected with Boolean operators -- to use in a library database search to retrieve relevant resources for any research assignment.

- Database Search Menu Template Use this search menu template to plan a database search.

- Next: Back to Research Help >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 2:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.rasmussen.edu/LitReview

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade.

- Open access

- Published: 17 August 2023

Data visualisation in scoping reviews and evidence maps on health topics: a cross-sectional analysis

- Emily South ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2187-4762 1 &

- Mark Rodgers 1

Systematic Reviews volume 12 , Article number: 142 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

3614 Accesses

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Scoping reviews and evidence maps are forms of evidence synthesis that aim to map the available literature on a topic and are well-suited to visual presentation of results. A range of data visualisation methods and interactive data visualisation tools exist that may make scoping reviews more useful to knowledge users. The aim of this study was to explore the use of data visualisation in a sample of recent scoping reviews and evidence maps on health topics, with a particular focus on interactive data visualisation.

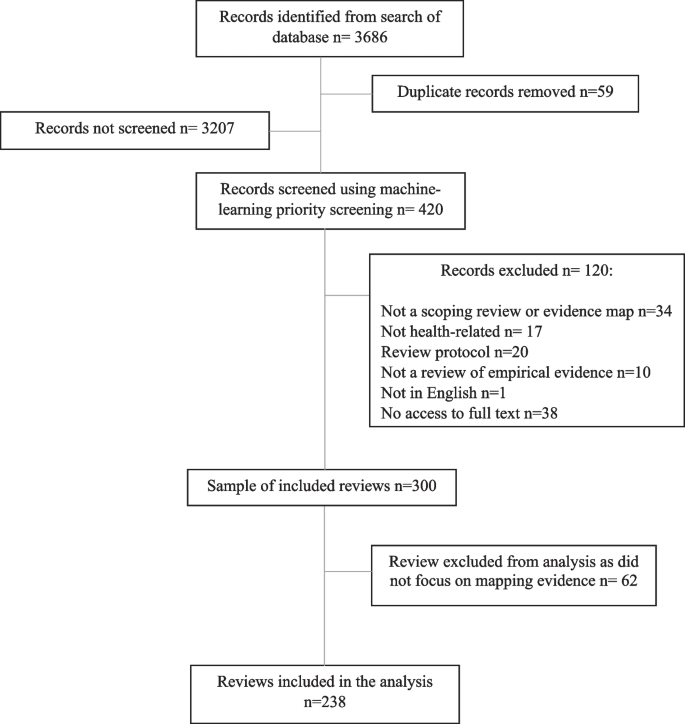

Ovid MEDLINE ALL was searched for recent scoping reviews and evidence maps (June 2020-May 2021), and a sample of 300 papers that met basic selection criteria was taken. Data were extracted on the aim of each review and the use of data visualisation, including types of data visualisation used, variables presented and the use of interactivity. Descriptive data analysis was undertaken of the 238 reviews that aimed to map evidence.

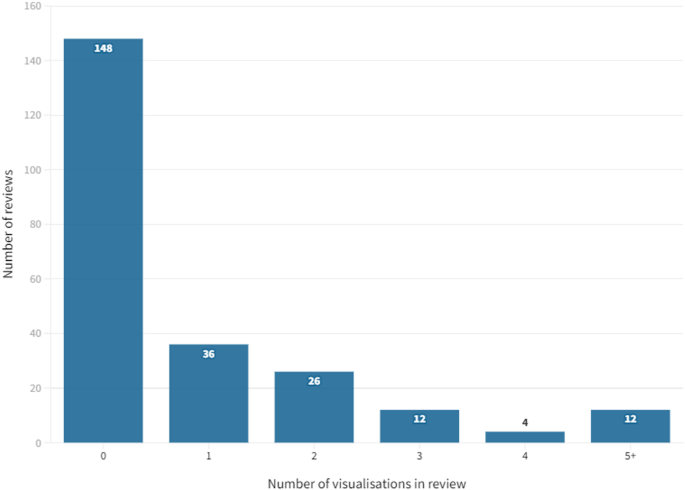

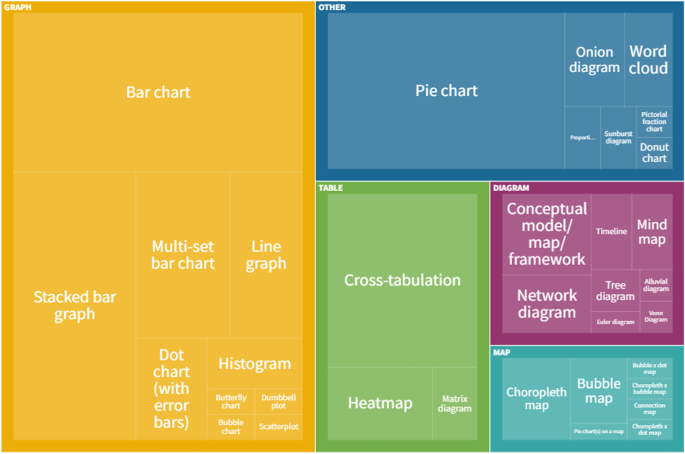

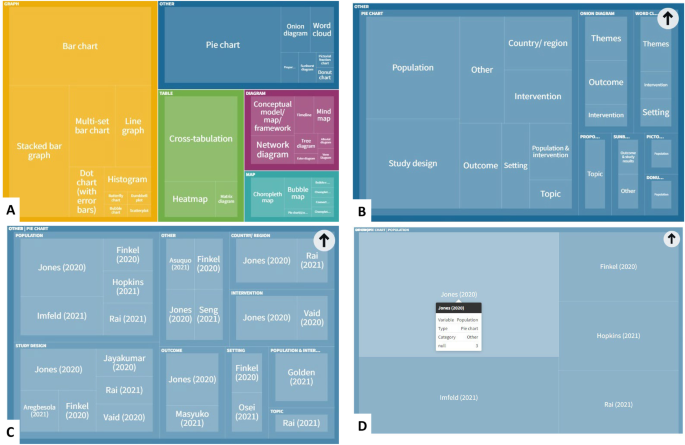

Of the 238 scoping reviews or evidence maps in our analysis, around one-third (37.8%) included some form of data visualisation. Thirty-five different types of data visualisation were used across this sample, although most data visualisations identified were simple bar charts (standard, stacked or multi-set), pie charts or cross-tabulations (60.8%). Most data visualisations presented a single variable (64.4%) or two variables (26.1%). Almost a third of the reviews that used data visualisation did not use any colour (28.9%). Only two reviews presented interactive data visualisation, and few reported the software used to create visualisations.

Conclusions

Data visualisation is currently underused by scoping review authors. In particular, there is potential for much greater use of more innovative forms of data visualisation and interactive data visualisation. Where more innovative data visualisation is used, scoping reviews have made use of a wide range of different methods. Increased use of these more engaging visualisations may make scoping reviews more useful for a range of stakeholders.

Peer Review reports

Scoping reviews are “a type of evidence synthesis that aims to systematically identify and map the breadth of evidence available on a particular topic, field, concept, or issue” ([ 1 ], p. 950). While they include some of the same steps as a systematic review, such as systematic searches and the use of predetermined eligibility criteria, scoping reviews often address broader research questions and do not typically involve the quality appraisal of studies or synthesis of data [ 2 ]. Reasons for conducting a scoping review include the following: to map types of evidence available, to explore research design and conduct, to clarify concepts or definitions and to map characteristics or factors related to a concept [ 3 ]. Scoping reviews can also be undertaken to inform a future systematic review (e.g. to assure authors there will be adequate studies) or to identify knowledge gaps [ 3 ]. Other evidence synthesis approaches with similar aims have been described as evidence maps, mapping reviews or systematic maps [ 4 ]. While this terminology is used inconsistently, evidence maps can be used to identify evidence gaps and present them in a user-friendly (and often visual) way [ 5 ].