Occupational Therapy in the Treatment of Severe Eating Disorders

Resource download.

Eating disorders impact all aspects of a patient’s life. Occupational performance issues in eating disorders can affect activities like meal preparation, socialization, financial management and self-grooming.Low body weight and malnutrition can affect an individual’s memory, cognition and concentration, making work or study more challenging. Engaging in eating disorder behaviors is a time intensive pursuit. For many, their eating disorder becomes the primary occupation of life, with all other areas of daily life declining. There is little time, energy or motivation left for things like showering, cleaning or socializing. As individuals with eating disorders become less engaged with other occupations, motivation, independence and quality of life decline. This often leads individuals to stop going to school or work, participating in hobbies or activities, seeing their loved ones or leaving their home. Occupational therapy can help eating disorder patients re-engage and learn new coping mechanisms to help fully participate in all areas of their lives.

Related Resources

resource-icon-medical-file@32x32

Pregnancy in Women with Severe Eating Disorders

Electrolyte disturbances in eating disorders, eating disorders & suicidality, eating disorders in men & boys.

ACUTE Earns Prestigious Center of Excellence Designation from Anthem In 2018, the ACUTE Center for Eating Disorders & Severe Malnutrition at Denver Health was honored by Anthem Health as a Center of Excellence for Medical Treatment of Severe and Extreme Eating Disorders. ACUTE is the first medical unit ever to achieve this designation in the field of eating disorders. It comes after a rigorous review process.

- DOI: 10.1300/J004V06N01_03

- Corpus ID: 145636825

Occupational Dysfunction and Eating Disorders

- Roann Barris EdD Otr

- Published 26 August 1986

- Psychology, Medicine

- Occupational Therapy in Mental Health

13 Citations

Occupational therapy with eating disorders: a study on treatment approaches, the impact of binge eating disorder on occupation: a pilot study, psychologists' perceptions of occupational therapy in the treatment of eating disorders, frames of reference utilized in the rehabilitation of individuals with eating disorders, occupational therapy and the treatment of eating disorders., occupational therapy services, is there a role for occupational therapy within a specialist child and adolescent mental health eating disorder service, relationships between eating behaviors and person/environment interactions in college women, time use and daily activities in people with persistent mental illness., an evaluation of ‘work’ for people with a severe persistent mental illness, 27 references, the syndrome of bulimia. review and synthesis., preliminary investigation of bulimia and life adjustment., locus of control, psychopathology, and weight gain in juvenile anorexia nervosa, structural discontinuity and the development of anorexia nervosa, locus of control as a measure of ineffectiveness in anorexia nervosa, occupational role acquisition: a perspective on the chronically disabled., a clinical perspective on motivation: pawn versus origin., psychosocial dynamics in anorexia nervosa, anorexia nervosa in the context of daily experience, the occupational career..., related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Eat Disord

The importance of including occupational therapists as part of the multidisciplinary team in the management of eating disorders: a narrative review incorporating lived experience

Rebekah a. mack.

1 The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 600 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, MD 21287 USA

Caroline E. Stanton

2 Prisma Health Kidnetics, 29 N. Academy Street, Greenville, SC 29601 USA

Marissa R. Carney

Associated data.

Not applicable.

The literature demonstrates the importance of utilizing a multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of eating disorders, however there is limited literature identifying the optimal team of professionals for providing comprehensive and effective care. It is widely accepted that the multidisciplinary treatment team should include a physician, a mental health professional, and a dietitian, but there is minimal literature explaining what other professionals should be involved in the medical assessment and management of eating disorders. Additional team members might include a psychiatrist, therapist, social worker, activity therapist, or occupational therapist. Occupational therapists are healthcare professionals who help their clients participate in the daily activities, referred to as occupations, that they have to do, want to do, and enjoy doing. Many factors (e.g., medical, psychological, cognitive, physical) can impact a person’s ability to actively engage in their occupations. When a person has an eating disorder, it is likely that all four of the aforementioned factors will be affected, thus individuals undergoing treatment for an eating disorder benefit from the incorporation of occupational therapy in supporting their recovery journey. This narrative review strives to provide education on the role of the occupational therapist in treating eating disorders and the need for increased inclusion of this profession on the multidisciplinary team. Additionally, this narrative review offers insight into an individual’s personal experience with occupational therapy (i.e., lived experience) during her battle for eating disorder recovery and the unique value that occupational therapy offered her as she learned to manage her eating disorder. Research suggests that occupational therapy should be included in multidisciplinary teams focused on managing eating disorders as it empowers individuals to return to activities that bring personal meaning and identity.

The recommended approach for individuals participating in treatment for an eating disorder involves the use of a multidisciplinary treatment team which includes a physician, dietitian, and a mental health provider. Sometimes a psychiatrist, social worker, activity therapist, and/or an occupational therapist might also be included in this team. Occupational therapy addresses an individual’s ability to engage in meaningful daily activities. The ability to actively participate in these activities is impacted when an individual has an eating disorder. Therefore, research suggests that eating disorder treatment include occupational therapy to best support the individual in working toward and maintaining recovery, and ultimately empowering them in living life to the fullest.

Introduction

The literature reflecting the medical assessment and management of eating disorders (EDs) describes the importance of utilizing a multidisciplinary team approach in order to provide the most effective and holistic treatment. Considering the pervasive impact of an eating disorder (ED), multiple practice guidelines as well as other previously published literature recommends the provision of treatment from medical professionals with expertise in various domains to provide the individual with the optimal chance of obtaining a full recovery [ 1 – 8 ]. Despite the consistent message of the need for a multidisciplinary team, there is limited literature depicting which professionals should be a part of that team. Joy, Wilson, & Varechok [ 6 ] (pp331) highlight the importance of including various professions when working with individuals who have EDs: “[they] think differently…it is the main reason that multidisciplinary treatment is so valuable. In treating a patient with an eating disorder (ED), no single approach is adequate because the problem itself is multidimensional”. The literature unanimously agrees with the presence of a physician on the multidisciplinary team, albeit there is variation as to whether the physician should be specifically a psychiatrist or any medical doctor (e.g., primary care physician).

The next most commonly recommended professionals to be included in the multidisciplinary team are dietitians and psychotherapists [ 1 , 6 ]. Then, in no particular order, the following providers are mentioned as potential team members: family therapists, exercise therapists, activity therapists, social workers, nurses, counselors, ED-trained peer support workers, and occupational therapists (OTs) [ 1 , 2 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 9 ]. Notably, these providers are mentioned, but there is not a clear description provided of their roles, outside of the physician (comprehensive evaluation including a medical history, review of systems, physical examination, and laboratory/diagnostic testing), dietitians (assess nutritional status, food attitudes, eating patterns/behaviors), and psychotherapist (screening tools, presenting problem, psychosocial history, mental status, diagnosis, and treatment plan) [ 6 ]. One article [ 6 ] discusses the physician’s role in asking about the patient’s performance at work, school, and home, as well as their ability to perform self-care tasks; these are areas that an occupational therapist (OT) is highly skilled in assessing and helping the individual to improve.

OTs are healthcare professionals who support individuals experiencing disorders, diseases, illnesses, and injuries through occupational engagement—the participation in meaningful activities of daily living which promote physical and mental wellness [ 10 ]. As described in the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process, OTs work in partnership with clients to analyze the interplay between one’s illness and personal factors (i.e., environment, habits, routines, roles, rituals, values, beliefs) that facilitate or impede a person’s ability to partake in daily activities [ 10 ]. OTs describe this as being one’s occupational performance which is “the accomplishment of selected occupation resulting from the dynamic transaction among the client, their contexts, and the occupation” [ 10 ] (pp8). Within occupational therapy treatment, a client-centered, collaborative, and goal-oriented approach empowers the individual to increase independence in a broad array of health management skills, thereby facilitating a personal sense of satisfaction and purpose [ 10 ]. OTs bring a distinct value to the management of EDs, both within hospital and community-based settings. Yet, OTs are not standard multidisciplinary treatment team members for these illnesses [ 11 ]. EDs are serious mental illnesses that lead to pervasive functional deficits in everyday activities, which can be addressed through occupational therapy intervention [ 11 – 13 ]. Through this narrative review, authors describe the role and benefit of including occupational therapy within ED treatment while offering personal insight from an individual with lived experience. Integration of lived experience within research is supported by prior literature, such as that of Beames et al., which states that use of lived experience “supports the identification and development of treatment approaches that align with the needs of those intended to use them” [ 14 ] (pp1)]. Consequently, it is important to not only further explore the role and benefit of occupational therapy’s inclusion within ED treatment, but also necessary to determine if this intervention aligns with the needs of those individuals who have ED.

Personal lived experience is provided by M.R. Carney who agreed to collaborate with the primary author (Mack) to discuss her perspective of occupational therapy during ED treatment and the lasting impact on her recovery. Carney worked with Mack in an inpatient hospital setting three years ago, and consequently, it is important to recognize that there is potential for bias by both Carney and Mack. At discharge, Carney initiated a desire to intermittently stay in contact with Mack. Boundaries were put in place by both parties to support professionalism and Carney’s autonomy in her continued recovery. Before, during, and after her time in the Eating Disorder Unit of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Carney has been consistent in her intentions to educate others about the impact of EDs and the importance of asking for and receiving help. For example, Carney shared her lived experience with a group of her teenaged dance students to not only educate them on the importance of addressing mental health but to be a strong role model for them. Additionally, Carney is working on a novella about her anorexia, her experiences of having an ED while undergoing treatment for breast cancer, and parallels between the two illnesses. In being open about her story, Carney aims to impart knowledge and share hope.

When the idea for this narrative review originated, Mack asked Carney via email to consider whether she would like to further advocate for ED treatment and recovery by sharing her own personal lived experience. Carney agreed verbally and then written documentation (e.g., ethics approval and consent) was completed to demonstrate Carney’s willingness and desire to be involved in the development of this narrative review. Further ethics approval was unnecessary per Johns Hopkins Hospital’s ethics committee. Mack requested a written response from Carney to the prompt “How did occupational therapy impact your experience within eating disorder treatment and your overall recovery process?” The prompt was intentionally broad and open-ended to prevent bias and allow Carney to share the information she felt was most pertinent to her experience. Carney’s account was written in July 2022, with reflections taken from her personal journals, original poetry and other writings, and artwork during and after treatment. Additional ways that the authors sought to address bias include: Carney was not offered any incentives (e.g., gifts; monetary) to participate; there was no chance that Carney would be provided with any additional treatment or support because she agreed to share her experience; Carney does not have any prior relationship or encounters with Stanton; and Carney was encouraged to leave her personal account unfiltered prior to submission. Carney’s personal lived experience has been edited slightly based on the editorial process.

The profession of occupational therapy is rooted in mental health: it arose as the absence of engagement in meaningful activity was found to be a core issue of the Nineteenth century psychiatric institutions [ 15 ]. Unfortunately, few individuals—professional and otherwise—have heard of occupational therapy, let alone understand the vast skill sets it contributes to the client and multidisciplinary treatment team. OTs view any activity that a person engages in as an occupation (i.e., occupational engagement): therefore, OTs help clients work on living life to the fullest by supporting participation (i.e., occupational performance) in the things one needs to do (e.g., responsibilities; hygiene), wants to do (e.g., leisure; hobbies), and enjoys doing (e.g., personal interests) [ 10 ].

This description of occupational therapy is reflected within Carney’s personal account:

My favorite part of the day was normally occupational therapy. Besides initially misunderstanding the role of occupational therapy in ED treatment, I also misunderstood that the word “occupational” does not just refer to a job or career. Turns out it includes all the things that make up a person’s day, their environment, and what makes their life meaningful. It had certainly never occurred to me that, much like a stroke survivor, I’d have to relearn aspects of everyday life. Instead of walking or speaking, it was grocery shopping, meal prepping and cooking, and the actual act of eating food. I needed to learn coping skills to eat alone or in social situations. These were just some of the abilities of daily tasks that I lost during my ED.

Occupational therapy and activity analysis

OTs are trained in the art of activity analysis: examining a task to determine and problem-solve through all elements required to successfully complete it [ 10 ]. For example, while preparing a peanut butter and jelly sandwich might seem simple, it is actually quite complex in the number of steps and cognitive processes involved. The person engaging in the activity first must have adequate interoception to identify the body signaling that it needs nutrients and then respond to this signal by initiating the food preparation task. Next, the person must have the necessary executive function skills to sequence a multi-step activity. The person must have appropriate grip strength, range of motion, and visual perception to locate and then obtain the necessary materials. The person’s distal control, fine motor coordination, force gradation, and strength must support them in spreading the peanut butter and jelly onto the bread with minimal mess. The person needs to be able to problem-solve how much peanut butter and jelly to spread on the bread and when to terminate the task. The person must have the sensory processing skills to modulate the visual, tactile, and olfactory stimuli experienced during this task. Already, a multitude of steps have been identified that are needed to make preparing a sandwich a successful experience, and the task is not yet finished. This knowledge and understanding of daily occupations, the associated cognitive processes, and the meaning ascertained to each individual’s occupations reflect an OT’s expertise.

Impact of ED on occupational performance

EDs have a high mortality rate [ 1 , 16 , 17 ], and pervasively impact one’s life [ 18 ]. An ED at minimum will affect the way that an individual interacts with food, engages in social situations involving food (e.g., parties; holidays), manages their roles (e.g., family member, employee), and perceives themselves (i.e., identity, self-esteem) [ 11 – 13 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 26 ]. The literature documents that additional areas impacted include but are not limited to: hygiene; school/work involvement; ability to care for others; physical health; mental/emotional health (e.g., mood, anxiety); finances; socialization (i.e., isolation); relationships; communication via increased secrecy; ability to cope positively; emotional regulation; and ability to contribute to society [ 2 , 11 , 12 , 19 – 26 ]. All of the aforementioned aspects are areas an OT is skilled in addressing, ultimately supporting the individual in living their life to the fullest. In doing so, OTs adopt a holistic approach by treating areas including, but not limited to:

- "Appropriate eating behaviors

- Client factors specifically related to triggers to engaging in ED behavior, warning signs of relapse, and positive coping strategies

- Balanced occupational engagement

- Desired role performance, in contrast to illness role performance

- Emotional regulation

- Self-esteem

- Environmental and contextual implications

- Impaired functional cognition related to malnutrition

- Performance patterns

- Interpersonal skills

- Overall health management” [ 13 ] (pp17).

Participating in daily activities that an individual derives personal meaning from fosters the belief that one’s life is valuable, aids in the formation of identity, and promotes feelings of satisfaction, competence, and belonging [ 27 , 28 ]. With EDs, these typical daily activities—such as eating, cooking, shopping, exercising, socializing, and working—evolve around the disordered cognitions and are executed in a manner that sustains the ED and hinders one’s physical and mental health [ 12 ]. For example, participation in exercise is often driven by an intense urge to burn calories to promote feelings of control over one’s body shape and size, even when an individual is already medically compromised due to malnourishment and/or being at a low body weight [ 11 ]. Grocery shopping and meal preparation may provoke dysregulated emotional states and involve rigid routines [ 11 ]. Self-care activities such as bathing and dressing may be challenging due to exposure to one’s own physical body or physical weakness [ 11 ]. A person’s daily routine oftentimes revolves around these time-consuming disordered behaviors and cognitions, leading to an occupational imbalance in which one does not engage in meaningful and health-promoting activities.

The impact of an ED on one’s occupational engagement is evident throughout Carney’s personal account:

My anorexia included severe restriction and over exercise. It took control of me very quickly, and I couldn’t get out of it on my own.

I work in media relations for a Big 10 university. While that includes a bunch of different facets, most of my job is writing. The deeper into anorexia I slid, the harder that became. The brain fog was real. I couldn’t focus, couldn’t organize my thoughts, couldn’t write more than a few (crappy) sentences at a time. An article that I once could have written in a day or two started taking a week or longer. I was frustrated because I didn’t really understand what was happening to me, but I was more apathetic about it. I’m a hustler, baby, so this was all totally out of character.

I’m also a dance instructor and was teaching two nights a week when things started to get really bad. I’m a very hands-on, loud, engaged teacher. I’m talking full-out demonstrations, full-out dancing alongside the students, much cheerful yelling, lots of emphatic counting and clapping and various unintelligible noises. As the weight sloughed off and my level of nourishment plummeted, I couldn’t keep up with my normal style of teaching. I was winded after a half-hearted attempt at a demonstration. I barely had the energy to speak, let alone holler over the music. I had to cut back on my classes the year before I went to treatment. Gone was my vibrant personality. My students were paying a price, and that wasn’t fair to them. I don’t teach because I need the money—dance is my passion, my expression, where I feel like I can make an impact. So I knew I should be upset about it, but I was too numbed out, too depleted to be anything but indifferent.

The two biggest portions of my life were suffering terribly and so were the many other smaller pieces. I am a voracious reader, but I couldn’t focus or absorb what was on the pages anymore. I love being in nature and doing physical activities, but I was too tired, and eventually too weak, to hike or play sports. I had no interest in even spending time with my nieces and nephew. I avoided family events or hanging out with friends because I didn’t want to be around food or fake my way through conversations.

Anorexia was taking everything from me. I knew if I didn’t get into treatment, it would take my life, as well.

Occupational therapy treatment

OTs support individuals in learning how to engage in these daily activities while managing the impact of the ED on one’s participation. In doing so, OTs implement various techniques such as activity analysis, environmental adaptation, and positive functional coping skills to manage distress and support occupational performance [ 11 , 19 , 20 ]. For example, an OT may work with a client on their ability to plan, grocery shop for, prepare, and consume a meal that adheres to their nutritional needs and meal plan requirements. While doing so, the OT and client work together to challenge any disordered thoughts or behaviors the client has while engaging in the task. This may include a multitude of actions such as selecting a meal that does not conform to the individual’s rules related to foods they will/will not consume, walking a different route in the grocery store, purchasing items without reading nutritional labels, choosing a different brand of a food item, using less rigid food preparation methods, consuming the prepared meal, and deferring from using disordered or compensatory behaviors (i.e., bingeing, purging, restricting). The OT works with the client throughout this process to reframe disordered cognitions and utilize positive coping skills [ 20 ]. By implementing activity-based interventions within the contextual environment and providing graded support, OTs support the client to help them succeed in taking action steps that promote recovery [ 11 ]. Attaining success leads to improved self-esteem and a gradual increase in one’s independence in completing the task [ 11 , 13 ]. OTs’ expertise and ability to analyze the skills a client requires to complete a task and to provide graded support are a unique contribution to the client and multidisciplinary treatment team.

Engaging in disordered eating behaviors becomes what gives an individual meaning, value, and purpose in life [ 12 , 21 , 27 ]. This occurs because EDs alter the mechanism by which individuals derive meaning via changes in the dopamine reward system, which alter one’s mediation of pleasure [ 29 , 30 ]. Following the rules created by the disorder (i.e., calorie limitations, food restrictions, use of compensatory behaviors) provides the individual with a sense of control, structure, and routine. Attaining disordered goals (i.e., weight loss, physical appearance goals) fosters a sense of accomplishment (i.e., mastery) and achieved perfection. Individuals with EDs may become known by others for their ability to demonstrate restraint while eating, their dedication to exercise, and their ability to control their body size/shape, thereby leading to a sense of pride and further development of an identity based in their disorder [ 12 ]. The ED serves as a source of comfort, solace, and protection: it is a coping mechanism, yet it can lead to physical and psychiatric morbidity and mortality [ 16 – 21 , 27 ]. As described by Lavis [ 21 ] (pp457), the ED can “be a paradoxical mode of self-care”. The recovery process is often associated with distress related to the inability to attain this self-care through disordered behavior [ 21 ]. Thus, the development of positive coping skills, engagement in supportive self-care, and formation of identity outside of the ED are essential to recovery.

OTs assist clients in discovering their identity outside of the ED. OTs challenge the assumption that the individual is defined by their disorder by collaborating with them to analyze their personal beliefs and values. OTs also promote formation of identify by supporting clients in successful engagement in activities that promote a sense of purpose and meaning in life [ 12 , 27 , 31 ]. These activities may be skills or hobbies such as art, reading, socialization, or academics. In some cases, individuals may need support in re-engaging in activities they previously enjoyed but have become apathetic toward. In other cases, clients may need assistance in ascribing new meaning to the activity; for example, mindful movement for leisure rather than obsessional exercise [ 11 , 12 ]. OTs also work with clients to identify the roles they want and need to fulfill: for example, sibling, parent, employee, student, caretaker of animals, friend [ 32 ]. Envisioning being able to fulfill a meaningful role without the restraints of the disorder oftentimes serves as a motivating factor in the pursuit of recovery. OTs collaborate with clients to plan and implement action steps to resume or improve performance in these roles and activities [ 32 ]. A study by Dark & Carter [ 33 ] showed that despite occupational engagement increasing recovery from an ED, participants identified that greater transformation occurred when the meanings associated with occupations changed. Forming one’s purpose apart from the ED is an essential step in promoting recovery [ 12 ], as it empowers individuals to participate in daily life without relying on the disorder to sustain their identity.

When working in higher levels of care, OTs aid clients in developing skills necessary for continuing to work towards recovery as they transition to lower levels of care. During this transition, clients are vulnerable to relapse due to the vast array of challenges they encounter when reintegrating into the community [ 34 ]. Some of these challenges include managing the loss of the structure and support provided through intensive treatment, scheduling and planning for meals, identifying purpose outside of the ED, coping with triggers (i.e., media, comments from others), and resuming school/work/family roles [ 34 ]. OTs collaborate with the client to identify and problem-solve strategies to manage these challenges and pursue recovery. Literature states that techniques such as time management, assertive communication, engagement in leisure activity, emotional expression, seeking support from others, and positive coping skills promote recovery [ 34 ]. These are all skills that an OT can teach to a client while providing graded support as the client learns to implement them with decreased assistance. Therefore, it is suggested that OT’s have an essential role in supporting individuals as they learn to re-engage in the world outside of their ED.

Carney provides insight into her experience with inpatient occupational therapy treatment through her personal account:

In occupational therapy, it wasn’t just that the OT was always prepared and kind and compassionate toward us. Or that we played fun games to start off the session. Or that I felt a tiny bit less pressure to be perfect there. I got a lot out of occupational therapy because we used writing, drawing, and other forms of art to express ourselves and reinforce the main points of what we were covering that day. We made a lot of lists, and damn do I love making lists. Our lists had lists. We made goals and talked about how we could attain them. We shared barriers to our recoveries and came up with ways to overcome them. We dug into motivations for recovery. We talked about attainable actions and the results/benefits of recovery.

Eventually, I was able to participate in Food Prep Fridays, which is just what it sounds like. We’d plan a menu, prepare, then eat the food we made according to our personal meal plans. Honestly, the only thing I liked about these Friday lunches was getting off the unit for a few hours.

Holy hell did I loathe everything else about it. I hate cooking, I always have. No part of it is fun for me. I don’t like the smell of cooking food. I never have, even before the ED. I hated that we were not allowed to clean up as we went. Messes are also not fun for me. And I like efficiency. It may have been a little bit fun to plan for some different foods than we ate on-unit, but actually having to look at it, make it, and eat it was another story. It was not unusual for me to cry before, during, or after the meal. More often, it was all three.

But I knew it was another important step in preparing me to transition to the day hospital where I’d be reintroduced to eating out in restaurants and become increasingly responsible for feeding myself. Let me be clear: nothing made any of it easier or less painful. Nothing. But the practice, the discussions, the discoveries from occupational therapy and groups were fresh in my mind to reach for when I needed them.

As I got closer to my discharge, the OTs worked with me to create some meal plan ideas and options, lay out a support system of family, friends, and professionals, and put in place relapse prevention plans.

All to say that with occupational therapy, it felt like we were doing tangible, physical things to keep us working hard in the hospital, but that laid a recovery foundation for once we returned home.

Summary of personal account

Carney’s reflections on her experience with an ED reveal that she was impacted mentally, emotionally, neurologically, and physiologically. She became entrenched in new habits and routines specifically related to the ED behaviors of restriction and over exercise. Carney shared how her role as a writer was significantly impacted, as it became difficult for her to focus, articulate her thoughts, and write effectively. Completing previously "simple" tasks now required significantly more time. Carney’s drive to do well and take pride in her work was replaced with apathy—a common experience for individuals struggling with EDs. The ED continued to take over her life, and also stole from her identity: where she had previously been a very engaged and interactive dance teacher, Carney now physically, mentally, and emotionally could not maintain: “gone was my vibrant personality”. Emotionally, Carney verbalized that she knew that feeling upset would be rational and logical, but the ED had sucked so much from her that she instead felt nothing—“numb… [and] indifferent”. Carney’s ability to engage in meaningful leisure activities was impacted. She also became more isolated and withdrawn from the people she loved, thus impacting her socialization.

Carney shared that her experience with occupational therapy during treatment for her ED focused on addressing “all the things that make up a person’s day, their environment, and what makes their life meaningful.” She highlighted the focus on grocery shopping, meal preparation, cooking, eating food, positive coping skills, and socializing with others. Carney also emphasized occupational therapy’s intentionality with setting goals, identifying barriers, and then problem-solving strategies to support goal completion. She reflected on how the foundational work in occupational therapy ultimately supported her when she stepped down to a lower level of care (day hospital), especially related to developing meal plans and relapse prevention plans.

Carney summarizes the importance of occupational therapy for her recovery process with the following:

Without occupational therapy I know that I would not have learned or come to understand as much about my anorexia. I know that I would have been missing critical skills to stay the course, especially over the next two years.

I was discharged from Johns Hopkins Hospital in July 2019. By the following March, the COVID pandemic was raging. My university shut down, and I was working from home. My dance studio closed, and I was conducting classes over Zoom. No visits from family or friends. Eating disorders love isolation. Grocery store shelves were bare. Eating disorders thrive on food anxiety.

In April, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. In a world of isolation. With an eating disorder.

I had to really dig deep for my strength to stay the recovery course. I had to use every single tool I’d been given, every coping technique I’d been taught to get through my situation, many of which I’d learned in OT. I leaned into those things like reframing and distraction. Most helpful was the meal planning and prep exercises that I worked hard to keep implementing daily. I even recreated a few activities at various times. One was drawing a tree from roots to trunk, limbs, and leaves, and labeling each with things like fears, strengths, supports, and hopes. Another was a recovery collage/vision board.

I firmly believe occupational therapy has a place in ED recovery. I also know there is room for it to grow, so much more it could include for the benefit of those suffering. When this is understood, occupational therapy can be more widely accepted, funded, and given its proper place in treatment programs.

Conclusions

EDs are complex illnesses which multifariously impact one’s well-being, therefore provision of comprehensive treatment is essential. The inclusion of occupational therapy services bolsters the comprehensive nature of treatment as OTs possess a unique skill set in promoting management of EDs through multi-faceted approaches, including behavioral, psychosocial, environmental, cognitive, medical, and interpersonal. OTs are uniquely skilled in identifying the meaning that provokes participation in an activity and understanding how this engagement impacts one’s well-being and sense of self (i.e., identity) [ 12 , 27 ]. The multidisciplinary team commonly involved in treating EDs includes a physician, a mental health provider, and a dietitian [ 35 ]. These professionals are crucial in supporting an individual’s recovery from an ED; however, none are experts in addressing meaningful occupational engagement [ 11 ]. Engaging in daily life activities in a health-promoting manner is essential to enabling recovery, thus OTs are an essential member of the multidisciplinary team for the assessment and management of EDs.

Acknowledgements

Abbreviations.

| ED | Eating disorder |

| EDs | Eating disorders |

| OT | Occupational therapist |

| OTs | Occupational therapists |

Author contributions

RAM, CES, and MRC completed the literature review. The background on occupational therapy was written by RAM and CES. MRC provided a first-person narrative of her own journey to recovery from an eating disorder. All authors contributed to the text and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

RAM is the occupational therapist for individuals with EDs in both an inpatient and outpatient setting at a large hospital. She specializes in collaborating with a multidisciplinary team to provide evidence-based treatment for individuals with EDs, depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and suicidality. CES finalized her doctoral degree in occupational therapy earlier this year under RAM’s supervision and is now working in an outpatient clinic where she treats feeding and eating disorders.

There was no funding received for this paper.

Availability of data and materials

Declarations.

Ethical approval and consent to participate was provided verbally and via written form by MRC. Further ethics approval was unnecessary.

All three authors consented to publish this article.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Open access

- Published: 12 November 2021

From research to practice: a model for clinical implementation of evidence-based outpatient interventions for eating disorders

- Kristen E. Anderson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6958-7618 1 ,

- Sara G. Desai 1 ,

- Rodie Zalaznik 1 ,

- Natalia Zielinski 1 &

- Katharine L. Loeb 1

Journal of Eating Disorders volume 9 , Article number: 150 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3736 Accesses

2 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

A question frequently raised in the field is whether evidence-based interventions have adequate translational capacity for delivery in real-world settings where patients are presumed to be more complex, clinicians less specialized, and multidisciplinary teams less coordinated. The dual purpose of this article is to (a) outline a model for implementing evidence-driven, outpatient treatments for eating disorders in a non-academic clinical setting, and (b) report indicators of feasibility and quality of care.

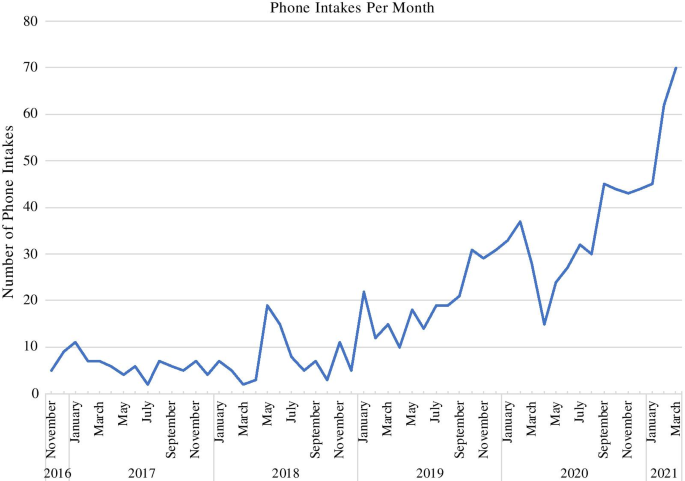

Since our inception (2015), we have completed nearly 1000 phone intakes, with first-quarter 2021 data suggesting an increase in the context of COVID-19. Our caseload for the practice currently consists of approximately 200 active patients ranging from 6 to 66 years of age. While the center serves a transdiagnostic and trans-developmental eating disorder population, modal concerns for which we receive inquiries are Anorexia Nervosa and Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder, with the most common age range for prospective patients spanning childhood through late adolescence/emerging adulthood; correspondingly, the modal intervention employed is Family-based treatment. Our team for each case consists, at a minimum, of a primary internal therapist and a physician external to the center.

Short Conclusion

We will describe our processes of recruiting, training and coordinating team members, of ensuring ongoing fidelity to evidence-based interventions, and of training the next generation of clinicians. Future research will focus on a formal assessment of patient outcomes, with comparison to benchmark outcomes from randomized controlled trials.

Plain English summary

A question frequently raised in the eating disorders field is whether treatments that were developed and tested in research environments can achieve the same results in real-world clinical settings, where patients’ diagnoses are presumed to be more complex, clinicians less specialized, and multi-professional care teams less coordinated. The purpose of this article is to outline a model for implementing evidence-driven, outpatient treatments for eating disorders in non-academic clinical settings, specifically private practices and specialty programs. We describe the philosophy, infrastructure, training processes, personnel, and procedures utilized to optimize care delivery and to create accountability for both scientifically-adherent practice and positive patient outcomes. We also outline ways to be producers—not just consumers—of research in the private sector, and to train the next generation of scientifically-informed eating disorder specialists, all with the goal to bridge the research-practice divide.

Introduction

A question frequently raised in the field is whether evidence-based interventions originating from highly specialized and controlled environments have adequate translational capacity for delivery in real-world settings, where patients are presumed to be more complex, clinicians less specialized, and multidisciplinary teams less coordinated. Moreover, the dissemination and implementation literature has identified several systems-level barriers including the extensive time commitment required for training and treatment delivery, the paucity of qualified trainers and resources, and a lack of support from practice administrators [ 1 , 2 ]. However, recent studies examining cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders have demonstrated clinical outcomes similar to research outcomes [ 3 , 4 , 5 ], exemplifying that successful dissemination of other evidence-based interventions is plausible. In this article, we outline a model for implementing evidence-driven, outpatient treatments for eating disorders in a non-academic clinical setting (specifically private practices and specialty programs), and report indicators of feasibility and quality of care. We will describe our processes of developing a community-based practice including recruiting, training, and coordinating team members, ensuring ongoing fidelity to evidence-based interventions, and training the next generation of clinicians. The overarching purpose of this paper is to illustrate the replicability and dissemination potential of our model and to support community-based eating disorder therapists in developing or enhancing their practice paradigms. This aim resonates with ongoing efforts in the eating disorders field to bridge the research-practice divide via transparency, communication, and collaboration. Future research will focus on a formal assessment of patient outcomes, with comparison to benchmark outcomes from randomized controlled trials.

Scope of the practice

The Chicago Center for Evidence Based Treatment (CCEBT) is an outpatient program serving children, adolescents, and adults with eating, feeding, and weight disorders, and other related and comorbid conditions. The primary goal and mission of CCEBT is to provide fidelity-driven treatments typically found in “ivory tower” academic settings in a community-based practice setting. We apply an evidence-based, multidisciplinary framework to our case conceptualization, assessment, treatment delivery, and clinical decision-making processes. From existing dissemination and implementation models [ 6 ], we primarily emphasize the training and supervision of clinicians, continuous review of quality indicators, and implementation support for evidence-based treatments in our administrative infrastructure. In addition to the clinical arm of our program, CCEBT offers training opportunities for future mental health professionals and conducts research in healthcare utilization of and intervention strategies for youth with Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), and transdiagnostic eating disorder presentations. Our trainees help us fulfill our commitment to maximizing access to care for all by providing affordable specialty treatment to individuals and families from the Chicago-area community. CCEBT currently has a grant-related academic affiliation with the Division of Adolescent Medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

We maintain an active caseload of approximately 200 patients. While the center serves a transdiagnostic and trans-developmental eating disorder population (including Bulimia Nervosa (BN), Binge Eating Disorder (BED), and Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED), our modal referrals are for children or adolescents with suspected AN or ARFID; correspondingly, and the modal intervention employed is family-based treatment (FBT) [ 7 ]. Our team for each case consists, at a minimum, of a primary therapist and a physician external to the center. We will describe our processes of developing a community-based practice including recruiting, training, and coordinating team members, ensuring ongoing fidelity to evidence-based interventions, and training the next generation of clinicians. Future research will focus on a formal assessment of patient outcomes, with comparison to benchmark outcomes from randomized controlled trials.

Since our inception in 2015, we have completed nearly 1000 phone intakes (Fig. 1 ). The majority of our referrals have come from professionals (physicians: 34%; therapists: 23%; school services and counselors: 10%; psychiatrists: 6%; dieticians: 1%) who are concerned that an adolescent patient has a restrictive eating disorder. Of those inquiring about treatment at CCEBT and completing an initial phone intake, half scheduled an in-person assessment (453 or 48%), or are on our waiting list (17 or 2%). The major reasons an assessment was not scheduled were insurance or cost concerns (26%), no availability with the desired therapist and/or a decision to seek treatment elsewhere (24%), or the patient instead proceeding to a higher level of care (9%). A quarter (25%) of individuals did not respond to any further contact from our clinical coordinator or program manager.

Volume of phone intakes per month and year

The founders

The founders of CCEBT, Kristen Anderson, a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) and Certified Eating Disorder Specialist Supervisor (CEDS-S), and Sara Desai, also a LCSW were previously members of a clinical and research team focused on eating disorders at an urban academic medical center. Anderson is a Certified FBT Provider and Supervisor, as well as a Faculty Member of the Training Institute for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders (TICAED). She is also a CEDS-S through the International Association of Eating Disorder Professionals (IAEDP). Desai is a Certified FBT Provider. In their academic positions, they contributed to the development and execution of clinical research trials, learning successful strategies for flexible adherence to research-supported interventions in the management of complex clinical cases. They grew professionally into leadership roles, focusing on staff development and team cohesion. Importantly, they observed a smooth integration of science and practice at the medical center, an ethos they embraced and brought to the formation of CCEBT, where the team utilizes best practice guidelines derived from randomized controlled trials, while also factoring in individual comorbidities, diversity-based factors, and systems-level considerations.

Personal life transitions brought an awareness of the importance and interdependence between the quality of life of clinicians and the quality of care for clients. This idea inspired the founders to create CCEBT. The partnership allowed for support on both the operational and logistics sides of the business as well as refining the clinical delivery model. To foster a strong sense of community at CCEBT and to protect fidelity to evidence-based protocols, we intentionally hired a team of therapists that shared the founders’ values, per recommendations from the literature [ 8 , 9 ]. Awareness of the “leaky pipeline” for women in academia [ 8 ] motivated us to forge an environment that prioritized clinicians’ autonomy regarding intensity and flexibility of work schedules, allowing for the prioritization of quality of life outside the workplace without compromising the provision of high-quality, highly specialized evidence-based treatment to our patients.

Creating the infrastructures: nuts and bolts

The considerations for trans-developmental eating disorder community-based providers include attention to the physical office space, the unexpected resource needs, and even the positioning of furniture. While the practice has grown substantially over the last five years, we have continued to ensure that the office space and logistics reflect the needs of patients and their families, and to provide a welcoming and comfortable space for our team. Specifically, we found that for clinicians to maintain adherence to the FBT [ 7 ] and Enhanced Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT-E) [ 10 ] models, the following infrastructure must be in place: offices large enough to accommodate a therapist plus at least a moderate-sized family; a table and chairs for in-vivo family meals and space in which to conduct such a session; and a high-quality scale plus stadiometer. Over time, we have reconfigured space plans and purchased additional scales to ensure that each office suite is flexible to meet the needs of individuals and families. It is important that clinicians consider the placement of scales to allow for a private place to record weight, while being out of the patient’s sight during sessions so as to not create undue distraction. Additionally, considerations for an inclusive and safe space to accommodate diverse populations include physical accessibility, accessibility of office location to public transportation, and availability of gender-neutral bathrooms.

To ensure that therapists have access to key clinical materials, the practice provides a library of treatment manuals and workbooks for clinicians, as well as access to reliable and valid measures to track patient outcomes. Such questionnaires can be directly accessed, completed, and submitted through the patient portal of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant electronic health record system utilized by the center. This online, user-friendly option permits regular collection of psychometrically-sound measures of inter-session and end-of-treatment symptom change, a critical feature of evidence-based practice. The electronic health record also structures therapists’ documentation of session content, including treatment strategies applied and patients’ progress toward their goals and objectives. In both regards, the electronic health record system provides a framework for accountability and attention to behaviorally-specific indicators of patient response to intervention, and thereby supports our practice values while also serving as a passive monitor of protocol fidelity. Similarly, we capitalize on the center’s webpage less as a means to advertise CCEBT and more as a method of serving the public through education about eating disorders, scientifically-informed treatments, and resources such as articles, books, podcasts, and other reference materials.

Making a meaningful connection from the start: the phone intake process

We developed our intake process to introduce prospective patients to the core philosophies of an evidence-based practice for eating disorders. Specifically, from the point of first contact, patients and/or their parents are exposed to fundamental tenets of treatment including the importance of: (a) an accurate diagnosis to inform treatment planning (e.g., for a family calling for treatment of a young child whose presentation might meet criteria for AN or ARFID), (b) favoring an actuarial clinical decision-making process over a subjective one (i.e., we start with the treatment for which the data show the strongest scientific likelihood of a good outcome, we do not assume that an intervention will not be appropriate for a particular patient unless research shows clear evidence of relevant moderator effects or there are clear clinical contraindications, etc.), and (c) the idea that eating disorders pose existing or potentially emerging medical and psychiatric crises that are urgent in nature (e.g., if a prospective patient is losing weight and our practice has no openings, we refer them to another provider rather than placing them on a waiting list; we require our active patients to see a physician for medical evaluation, clearance for outpatient treatment, and ongoing monitoring; we return intake calls within 24 h if possible; and we empower parents of children and adolescents to proceed with securing treatment even when met with extreme resistance). Thus, while there is an administrative component to the intake process, it is also an important clinical and psycho-educational intervention. Our program manager is a clinical social worker who previously worked as one of our therapists. She is familiar with the population we serve, the different treatment modalities that our practice offers, and the research behind them. This is particularly helpful when explaining FBT to families who are new to exploring the different types of treatment for eating disorders, or families who have heard or read about FBT and are interested but have questions or concerns. The program manager is also familiar with the specific certifications, competencies, and sub-specialties of each of our therapists, which is helpful when determining which clinician will be the right fit for each patient and their family.

Managing patient risk (and therapist risk too)

In our experience, there are several considerations to maintain adherence to evidence-based treatment while supporting our patients and their families to maintain safety on an outpatient basis. These include managing medical and psychiatric risks, as well as evaluating progress and comorbidities to determine if additional interventions or a higher level of care may be warranted. Clear communication between members of the treatment team is of utmost importance in evaluating and communicating progress to the patient and parents [ 11 ]. Due to the risks associated with eating disorders such as bradycardia, electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, and suicidality, among other concerns, it is imperative that a clinician feels well supported in order to appropriately support the patient and their family, in turn. CCEBT’s founders have established a policy to be available on an on-call basis for clinicians. Practice therapists are in regular contact with co-treating physicians and we utilize the local Emergency Room to triage medical and psychiatric risk.

In an effort to maintain adherence to the FBT model of care, a majority of our clients remain in treatment on an outpatient basis. In the instance that a higher level of care is indicated, the team typically intensifies treatment within the assigned modality. This may include more frequent visits, utilizing the adaptive protocol for FBT [ 12 ], or referring families to Multi-Family Therapy (MFT) [ 13 ]. CCEBT has established relationships with medical providers across the Chicagoland area for patients who require hospitalization. During medical and psychiatric hospitalizations, we advocate for parents to be involved in the renourishment process and included in the treatment plan for their young person. While we typically recommend waiting until or after Phase 2 of FBT to incorporate indicated adjunctive psychological interventions when the patient is more nourished, in some circumstances we have utilized treatments such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [ 14 , 15 ] or Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) [ 16 ] alongside FBT to manage comorbidities. This requires close contact and coordination of care between the therapist teams.

An additional consideration of operating our program has been managing therapist burnout. When constructing the management of referrals and caseload distribution, the practice owners were intentional about maintaining reasonable caseloads and offering employees autonomy regarding their schedules. We were cognizant of the standard academic or group model which often requires a high number of cases per week. In order to manage therapist burden, we have recommended to our team that they take on less than a standard caseload, particularly when delivering FBT. This allows for time to consult with outside providers and to regularly utilize supervision, thereby minimizing burnout and maintaining positive patient outcomes [ 9 , 17 , 18 ]. When developing our fee structure, we accounted for a session duration of 50–60 min, and the intensity of communication required to provide quality care. In effort to make treatment more accessible, we developed a process to provide low-cost treatment through a student clinic, and a reduced fee schedule.

Teamwork makes the dream work

With the aim of maintaining comprehensive care for our clients, we collaborate with healthcare providers in psychiatry, pediatrics, adolescent medicine, gastroenterology, speech therapy, and occupational therapy. Establishing our network of care providers has been a combination of luck and persistence. Initially, we developed a collaborative agreement with an adolescent medicine physician at an area hospital. This ongoing relationship and collaboration has been integral in the delivery of adherent manualized treatment. Due to this physician’s expertise and commitment to the treatment of eating disorders, we are able to treat children, adolescents, and young adults that may have otherwise required higher levels of care. This relationship allows us to treat patients just as we would on a team in academia, with regular communication and management of cases. As our practice has grown we have continued to build a network of providers specialized in eating disorders. This network is strengthened by frequent communication and the opportunity to present at case conferences and other educational seminars. This collaborative approach provides a unified team for our patients and their families [ 19 ]. In our model, therapists regularly speak to the adolescent medicine physicians by phone, and we have adopted a “clinic rounds” meeting once a month with each physician team to discuss cases in more depth. We also work very closely with several adult and child psychiatrists as well as other therapists who specialize in DBT, couples counseling and family therapy. The importance of these networks cannot be overstated as they allow the families we see to feel contained and supported throughout the treatment process. They also facilitate a process where the medical/mental health team is on the proverbial “same page”, which has been instrumental in delivering evidence-based treatments. Moreover, the establishment of relationships with other clinicians and physicians is of no cost to the practice, but immense benefit.

Quality control of service delivery across clinicians has been an ongoing process ensuring continuous fidelity to evidence-based treatment protocols, a challenge documented amongst FBT providers the further they progress into treatment [ 20 , 21 ]. Notably, only about two-thirds of FBT therapists report using manual recommendations, and even those therapists report omitting key parts of treatment such as weighing the patient at every session [ 21 ]. Sources of therapist drift include patient and therapist reluctance to use more challenging, head-on approaches, as well as therapists’ intimidation of and low competency with a manualized protocol [ 22 , 23 , 24 ]. In effort to reduce therapist drift, we ensure that all of our clinicians are trained within the evidence-based models they utilize in treatment. Clinicians who offer FBT are either currently certified or are pursuing certification through the TICAED. Additionally, our clinicians have completed the Centre for Research on Eating Disorders at Oxford (CREDO) training for CBT-E, have received training in FBT-ARFID, and have received training and supervision in Cognitive Behavioral Treatment for ARFID (CBT-AR). Our clinicians often attend continuing education trainings as a group. We offer both group consultation and one-on-one supervision weekly. As a team, we integrate expert external consultation to ensure that therapists have support with complex cases. The variety and flexibility of support for therapists protects their autonomy and sense of control, while also ensuring fidelity by reducing therapist anxiety and raising confidence in their mastery of the protocol [ 9 , 17 ].

Growth and expansion: future focused

CCEBT has steadily grown throughout the last five years. What started with a single office in Chicago, is now three office locations serving Chicago and the suburbs. The co-founders continue to dedicate time to the recruitment of clinicians that share the founders’ philosophies, values, and standards. The initial team of two founders/clinicians has grown to twelve. Currently, our team is comprised of 10 therapists, 1 student trainee, and a master’s level program manager. This team includes 4 director-level therapists, including the co-founders, a director of research and training, and a director of adult services.

The founders of CCEBT are also dedicated to continuing the research component outside of academia. In conjunction with the University of Illinois at Chicago, we have been awarded a Health Care Services Corporation Affordability Cures Grant to (a) analyze national benchmark healthcare utilization for adolescent eating disorders data, and (b) test whether implementation of MFT for AN alters clinical trajectories relative to these benchmark data. This grant further solidifies CCEBT’s affiliation and collaboration with the adolescent medicine division at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

We are optimistic that the dissemination of evidence-based treatments will continue to increase as clinicians in the field continue to develop programs across the world to deliver these much-needed interventions. In an effort to publish these community-based treatment data, we have partnered with other practices nationally with the goal of disseminating data related to indicators of fidelity to treatment as well as clinical outcomes. These research goals reflect our practice values by continuing to hold CCEBT to as many of the same standards inherent in randomized controlled trials as possible by conducting formal, aggregate assessments of patient outcomes, with comparison to benchmark outcomes from key studies utilizing the same interventions. We hope to expand research efforts to include staging treatment interventions, including the additions of DBT and other evidence-based treatments to FBT as well as understanding how we can best support clients for whom our standard treatments have proved inadequate.

The training and supervision of the next generation of therapists are of paramount importance. The social work internship and psychology externship at CCEBT are designed to (a) provide an advanced, specialized treatment-delivery experience to trainees while (b) increasing broader, transdiagnostic knowledge and competencies in: the common phenomenology and mechanisms of psychopathology; evidence-based and ethical clinical decision-making; operating within an interdisciplinary framework; crisis management; diversity issues; and professionalism. The practicum is focused on graduate students interested in one or more of the following areas: eating disorders, anxiety disorders, families, or children and adolescents. Our efforts to reduce direct patient care hours to prioritize supervision and training are a feature of our program. When the student therapist joins our team, they are required to attend intensive pre-requisite workshops and didactics (e.g., in FBT and CBT) prior to treating cases. Supervision is conducted in a combination of group and individual formats, with opportunities to also participate in professional-level peer consultation meetings. The secondary goal of the student clinic is to provide expert-supervised low-cost/no-cost treatment to the community. This allows CCEBT to provide clinical treatment to underserved populations.

In the dissemination of this practice model, solo or smaller practices should not be discouraged. CCEBT grew to twelve clinicians from an initial two by utilizing resources including no-cost options and by building a network of collaborations. Start-up costs can be lowered by relying on training sessions offered by professional organizations and speciality institutes, many of which simultaneously satisfy continuing education required for continued professional licensure. The emphasis on building strong relationships with fellow clinicians and physicians cannot be overstated and serves a two-fold purpose of satisfying the requirements of delivering FBT, and building a continuous system of support for therapists.

Our goal for creating the practice was to bridge the research/practice divide and increase access to care outside of academic medical centers. We hope that we have provided the readers with enough practical information and insight to feel that this is a feasible and highly rewarding format in which to provide clinical treatment. We believe that evidence-based interventions do indeed have adequate translational capacity for delivery in real-world settings like ours given the implementation of multidisciplinary care, attention to and execution of reliable practice protocols, and allowing an abundance of opportunities for training and consultation that are paramount for preserving the wellbeing of clinicians and patients alike.

Availability of supporting data

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Anorexia Nervosa

Binge Eating Disorder

Bulimia Nervosa

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Chicago Center for Evidence Based Treatment

Certified Eating Disorder Specialist Supervisor

Centre for Research on Eating Disorders at Oxford

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Exposure and Response Prevention

Family Based Treatment

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

International Association of Eating Disorder Professionals

Intensive Outpatient Program

Licensed Clinical Social Worker

Multi-Family Therapy

Couturier JL, Kimber MS. Dissemination and implementation of manualized family-based treatment: a systematic review. Eat Disord. 2015;23(4):281–90.

Article Google Scholar

Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. The dissemination and implementation of psychological treatments: problems and solutions. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46(5):516–21.

Byrne SM, Fursland A, Allen KL, Watson H. The effectiveness of enhanced cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders: an open trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(4):219–26.

Knott S, Woodward D, Hoefkens A, Limbert C. Cognitive behaviour therapy for bulimia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified: translation from randomized controlled trial to a clinical setting. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2014;43(6):641–54.

Turner H, Marshall E, Stopa L, Waller G. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for outpatients with eating disorders: effectiveness for a transdiagnostic group in a routine clinical setting. Behav Res Ther. 2015;68:70–5.

Southam-Gerow MA, McLeod BD. Advances in applying treatment integrity research for dissemination and implementation science: introduction to special issue. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2013;20(1):1–13.

Le Grange D, Lock J. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa a family-based approach (2nd edition). New York: The New Guilford Press; 2013.

Google Scholar

Ysseldyk R, Greenaway KH, Hassinger E, Zutrauen S, Lintz J, Bhatia MP, et al. A leak in the academic pipeline: identity and health among postdoctoral women. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1297.

Kim JJ, Brookman-Frazee L, Gellatly R, Stadnick N, Barnett ML, Lau AS. Predictors of burnout among community therapists in the sustainment phase of a system-driven implementation of multiple evidence-based practices in children’s mental health. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2018;49(2):132–41.

Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

Couturier J, Kimber M, Barwick M, Woodford T, McVey G, Findlay S, et al. Themes arising during implementation consultation with teams applying family-based treatment: a qualitative study. J Eat Disord. 2018;6(1):1–8.

Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, et al. Can adaptive treatment improve outcomes in family-based therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa? Feasibility and treatment effects of a multi-site treatment study. Behav Res Ther. 2015;73:90–5.

Eisler I, Simic M, Hodsoll J, Asen E, Berelowitz M, Connan F, et al. A pragmatic randomised multi-centre trial of multifamily and single family therapy for adolescent anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–4.

Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder (diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders). 1st ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993.

Linehan MM. DBT skills training handouts and worksheets. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015.

Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and response (ritual) prevention for obsessive-compulsive disorder: therapist guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Book Google Scholar

Aarons GA, Fettes DL, Flores LE, Sommerfeld DH. Evidence-based practice implementation and staff emotional exhaustion in children’s services. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(11):954–60.

Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A. The effects of organizational climate and interorganizational coordination on the quality and outcomes of children’s service systems. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22(5):401–21.

Loeb KL, Sanders L. Physician-therapist collaboration in family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa: What each provider wants the other to know. In: Innovations in family therapy for eating disorders: novel treatment developments, patient insights, and the role of careers. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2016.

Dimitropoulos G, Freeman VE, Allemang B, Couturier J, McVey G, Lock J, et al. Family-based treatment with transition age youth with anorexia nervosa: a qualitative summary of application in clinical practice. J Eatng Disord. 2015;3(1):1–3.

Kosmerly S, Waller G, Robinson AL. Clinician adherence to guidelines in the delivery of family-based therapy for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;48(2):223–9.

Couturier J, Kimber M, Jack S, Niccols A, Van Blyderveen S, McVey G. Understanding the uptake of family-based treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: therapist perspectives. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;46(2):177–88.

Waller G. Evidence-based treatment and therapist drift. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47(2):119–27.

Waller G. Treatment protocols for eating disorders: clinicians’ attitudes, concerns, adherence and difficulties delivering evidence-based psychological interventions. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(4):36.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the families that participate in our program as well as our team members for their support.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Chicago Center for Evidence Based Treatment, 25 E Washington Street, Suite 1015, Chicago, IL, 60602, USA

Kristen E. Anderson, Sara G. Desai, Rodie Zalaznik, Natalia Zielinski & Katharine L. Loeb

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

KEA, SGD, and RZ were responsible to conceptualizing this paper and creating the main body of work. NZ completed data analysis and contributed to revisions of paper. KLL was also primarily responsible in conceptualizing this paper, and in supervising the revisions of work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kristen E. Anderson .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Anderson, K.E., Desai, S.G., Zalaznik, R. et al. From research to practice: a model for clinical implementation of evidence-based outpatient interventions for eating disorders. J Eat Disord 9 , 150 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00491-9

Download citation

Received : 17 March 2021

Accepted : 06 October 2021

Published : 12 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00491-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Eating disorders

- Family-based treatment

- Private practice

- Multidisciplinary

Journal of Eating Disorders

ISSN: 2050-2974

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Occupational therapy and the treatment of eating disorders

Affiliation.

- 1 Staff Occupational Therapist, Eating Disorders Unit, Sheppard Pratt Hospital, Towson, MD.

- PMID: 23931288

- DOI: 10.1080/J003v08n02_03

The occupational therapist is vital to providing a complete assessment and thorough treatment of the population with eating disorders. Symptoms and etiology that effect the occupational therapist's reasoning are explored followed by the theoretical frameworks used and specific group intervention at the Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital. Two case studies conclude the article.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The therapist's attachment representation and the patient's attachment to the therapist. Petrowski K, Pokorny D, Nowacki K, Buchheim A. Petrowski K, et al. Psychother Res. 2013;23(1):25-34. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2012.717307. Epub 2012 Nov 2. Psychother Res. 2013. PMID: 23116364

- [The treatment of CRPS I from the occupational therapist's point of view]. Hügle C, Geiger M, Romann C, Moppert C. Hügle C, et al. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2011 Feb;43(1):32-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269889. Epub 2011 Jan 10. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2011. PMID: 21225544 Review. German.

- [Risk versus confidentiality: the therapist's responsibility for his psychiatric patient's acts]. Bauer A, Rosca P, Grinshpoon A, Griner E, Mester R. Bauer A, et al. Harefuah. 2003 Apr;142(4):304-8, 316, 315. Harefuah. 2003. PMID: 12754884 Review. Hebrew.

- Position paper on the role of occupational therapy in adult physical dysfunction. The Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. [No authors listed] [No authors listed] Can J Occup Ther. 1990 Dec;57(5):suppl 1-8. Can J Occup Ther. 1990. PMID: 10170645 English, French.

- A network of community services. Sheppard and Enoch Pratt Hospital. Towson, Maryland. [No authors listed] [No authors listed] Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1972 Oct;23(10):303-6. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1972. PMID: 5070245 No abstract available.

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Taylor & Francis

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Europe PMC requires Javascript to function effectively.

Either your web browser doesn't support Javascript or it is currently turned off. In the latter case, please turn on Javascript support in your web browser and reload this page.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS