A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:34 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Conducting a literature review: why do a literature review, why do a literature review.

- How To Find "The Literature"

- Found it -- Now What?

Besides the obvious reason for students -- because it is assigned! -- a literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

It Also Helps You:

- Publish and share your findings

- Justify requests for grants and other funding

- Identify best practices to inform practice

- Set wider context for a program evaluation

- Compile information to support community organizing

Great brief overview, from NCSU

Want To Know More?

- Next: How To Find "The Literature" >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 1:10 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/litreview

Literature Reviews

What is a literature review.

- Literature Review Process

Purpose of a Literature Review

- Choosing a Type of Review

- Developing a Research Question

- Searching the Literature

- Searching Tips

- ChatGPT [beta]

- Documenting your Search

- Using Citation Managers

- Concept Mapping

- Writing the Review

- Further Resources

The Library's Subject Specialists are happy to help with your literature reviews! Find your Subject Specialist here .

If you have questions about this guide, contact Librarian Jamie Niehof ([email protected]).

A literature review is an overview of the available research for a specific scientific topic. Literature reviews summarize existing research to answer a review question, provide context for new research, or identify important gaps in the existing body of literature.

An incredible amount of academic literature is published each year, by estimates over two million articles .

Sorting through and reviewing that literature can be complicated, so this Research Guide provides a structured approach to make the process more manageable.

THIS GUIDE IS AN OVERVIEW OF THE LITERATURE REVIEW PROCESS:

- Getting Started (asking a research question | defining scope)

- Organizing the Literature

- Writing the Literature Review (analyzing | synthesizing)

A literature search is a systematic search of the scholarly sources in a particular discipline. A literature review is the analysis, critical evaluation and synthesis of the results of that search. During this process you will move from a review of the literature to a review for your research. Your synthesis of the literature is your unique contribution to research.

WHO IS THIS RESEARCH GUIDE FOR?

— those new to reviewing the literature

— those that need a refresher or a deeper understanding of writing literature reviews

You may need to do a literature review as a part of a course assignment, a capstone project, a master's thesis, a dissertation, or as part of a journal article. No matter the context, a literature review is an essential part of the research process.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF A LITERATURE REVIEW?

A literature review is typically performed for a specific reason. Even when assigned as an assignment, the goal of the literature review will be one or more of the following:

- To communicate a project's novelty by identifying a research gap

- An overview of research issues , methodologies or results relevant to field

- To explore the volume and types of available studies

- To establish familiarity with current research before carrying out a new project

- To resolve conflicts amongst contradictory previous studies

Reviewing the literature helps you understand a research topic and develop your own perspective.

A LITERATURE REVIEW IS NOT :

- An annotated bibliography – which is a list of annotated citations to books, articles and documents that includes a brief description and evaluation for each entry

- A literary review – which is a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a literary work

- A book review – which is a critical discussion of the merits and weaknesses of a particular book

- Next: Choosing a Type of Review >>

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/litreview

Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

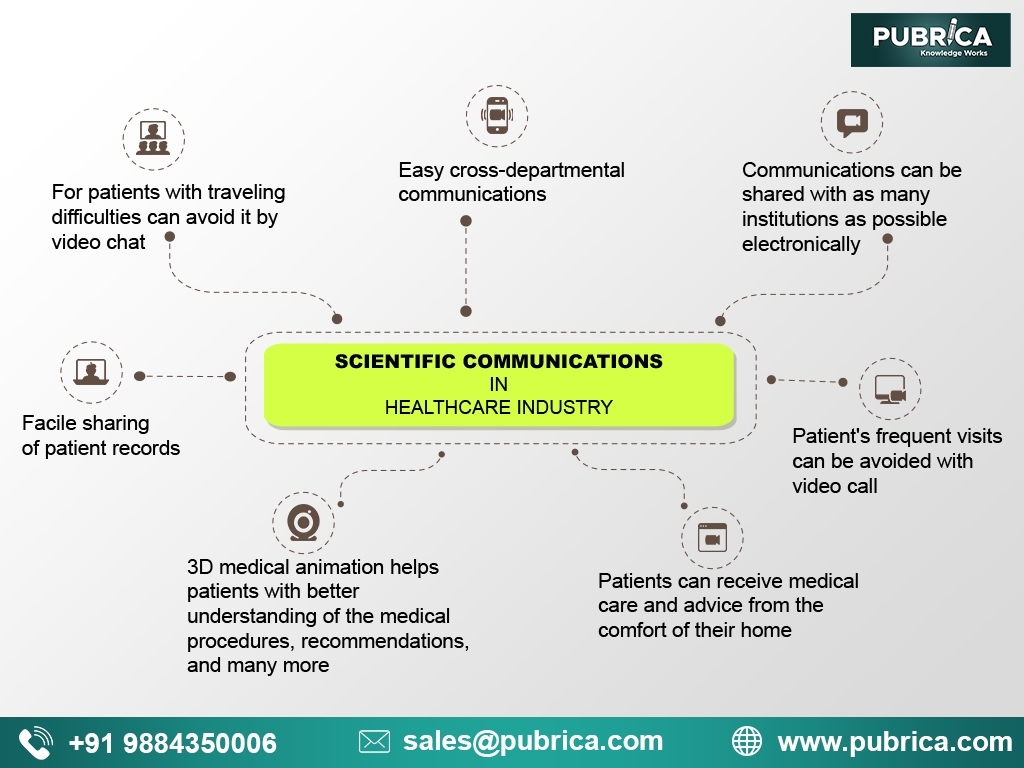

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

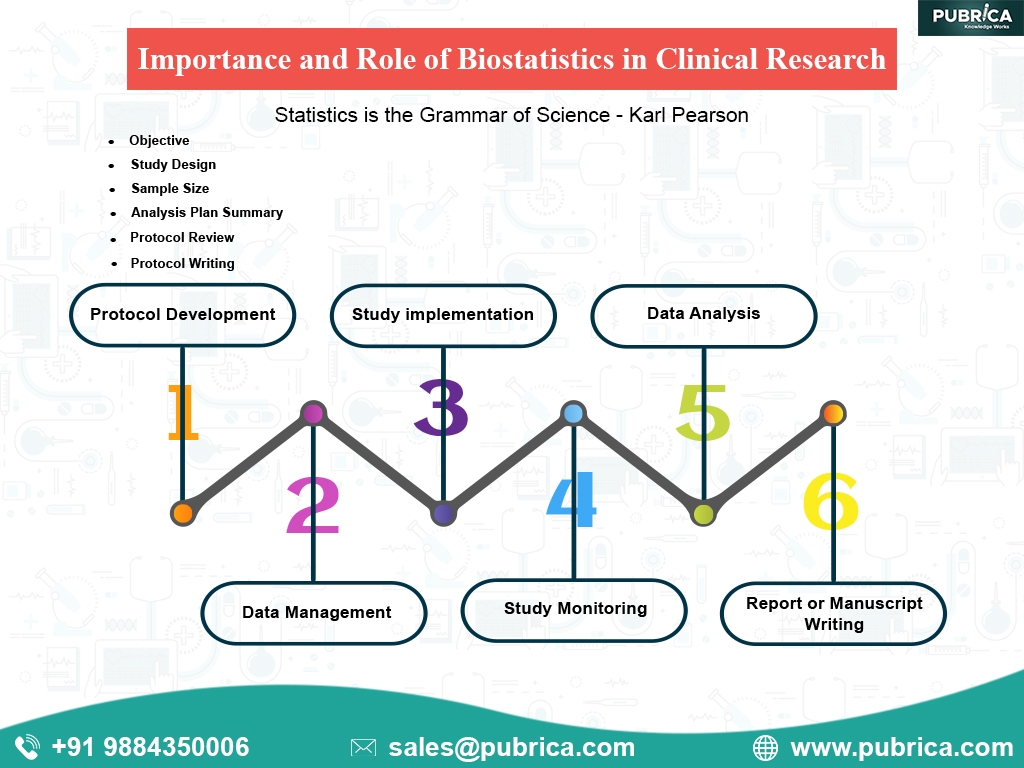

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

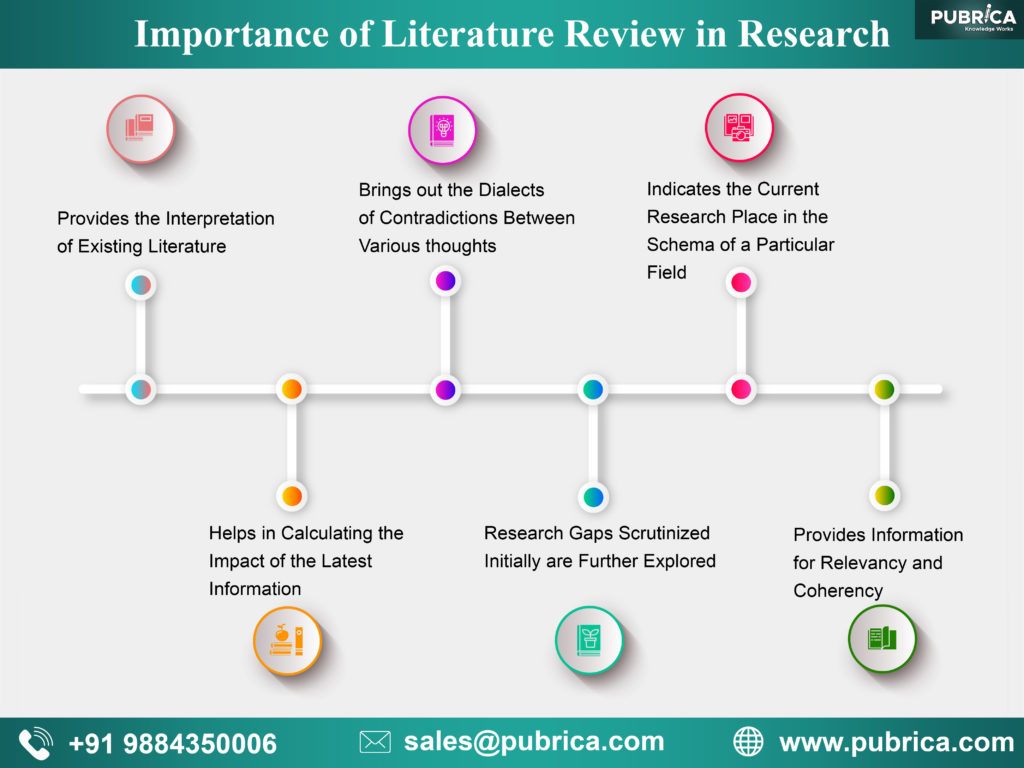

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

PUB - Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient) for drug development

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

PUB - Health Economics of Data Modeling

Health economics in clinical trials

Comments are closed.

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Literature Review in Research Writing

- 4 minute read

- 426.3K views

Table of Contents

Research on research? If you find this idea rather peculiar, know that nowadays, with the huge amount of information produced daily all around the world, it is becoming more and more difficult to keep up to date with all of it. In addition to the sheer amount of research, there is also its origin. We are witnessing the economic and intellectual emergence of countries like China, Brazil, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates, for example, that are producing scholarly literature in their own languages. So, apart from the effort of gathering information, there must also be translators prepared to unify all of it in a single language to be the object of the literature survey. At Elsevier, our team of translators is ready to support researchers by delivering high-quality scientific translations , in several languages, to serve their research – no matter the topic.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a study – or, more accurately, a survey – involving scholarly material, with the aim to discuss published information about a specific topic or research question. Therefore, to write a literature review, it is compulsory that you are a real expert in the object of study. The results and findings will be published and made available to the public, namely scientists working in the same area of research.

How to Write a Literature Review

First of all, don’t forget that writing a literature review is a great responsibility. It’s a document that is expected to be highly reliable, especially concerning its sources and findings. You have to feel intellectually comfortable in the area of study and highly proficient in the target language; misconceptions and errors do not have a place in a document as important as a literature review. In fact, you might want to consider text editing services, like those offered at Elsevier, to make sure your literature is following the highest standards of text quality. You want to make sure your literature review is memorable by its novelty and quality rather than language errors.

Writing a literature review requires expertise but also organization. We cannot teach you about your topic of research, but we can provide a few steps to guide you through conducting a literature review:

- Choose your topic or research question: It should not be too comprehensive or too limited. You have to complete your task within a feasible time frame.

- Set the scope: Define boundaries concerning the number of sources, time frame to be covered, geographical area, etc.

- Decide which databases you will use for your searches: In order to search the best viable sources for your literature review, use highly regarded, comprehensive databases to get a big picture of the literature related to your topic.

- Search, search, and search: Now you’ll start to investigate the research on your topic. It’s critical that you keep track of all the sources. Start by looking at research abstracts in detail to see if their respective studies relate to or are useful for your own work. Next, search for bibliographies and references that can help you broaden your list of resources. Choose the most relevant literature and remember to keep notes of their bibliographic references to be used later on.

- Review all the literature, appraising carefully it’s content: After reading the study’s abstract, pay attention to the rest of the content of the articles you deem the “most relevant.” Identify methodologies, the most important questions they address, if they are well-designed and executed, and if they are cited enough, etc.

If it’s the first time you’ve published a literature review, note that it is important to follow a special structure. Just like in a thesis, for example, it is expected that you have an introduction – giving the general idea of the central topic and organizational pattern – a body – which contains the actual discussion of the sources – and finally the conclusion or recommendations – where you bring forward whatever you have drawn from the reviewed literature. The conclusion may even suggest there are no agreeable findings and that the discussion should be continued.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews constantly feed new research, that constantly feeds literature reviews…and we could go on and on. The fact is, one acts like a force over the other and this is what makes science, as a global discipline, constantly develop and evolve. As a scientist, writing a literature review can be very beneficial to your career, and set you apart from the expert elite in your field of interest. But it also can be an overwhelming task, so don’t hesitate in contacting Elsevier for text editing services, either for profound edition or just a last revision. We guarantee the very highest standards. You can also save time by letting us suggest and make the necessary amendments to your manuscript, so that it fits the structural pattern of a literature review. Who knows how many worldwide researchers you will impact with your next perfectly written literature review.

Know more: How to Find a Gap in Research .

Language Editing Services by Elsevier Author Services:

What is a Research Gap

Types of Scientific Articles

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

Conducting a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Developing a Topic

- Planning Your Literature Review

- Developing a Search Strategy

- Managing Citations

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Writing a Literature Review

Before You Begin to Write.....

Do you have enough information? If you are not sure,

Ask yourself these questions:

- Has my search been wide enough to insure I've found all the relevant material?

- Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material?

- Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

You may have enough information for your literature review when:

- You've used multiple databases and other resources (web portals, repositories, etc.) to get a variety of perspectives on the research topic.

- The same citations are showing up in a variety of databases.

- Your advisor and other trusted experts say you have enough!

You have to stop somewhere and get on with the writing process!

Writing Tips

A literature review is not a list describing or summarizing one piece of literature after another. It’s usually a bad sign to see every paragraph beginning with the name of a researcher. Instead, organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question

If you are writing an annotated bibliography , you may need to summarize each item briefly, but should still follow through themes and concepts and do some critical assessment of material. Use an overall introduction and conclusion to state the scope of your coverage and to formulate the question, problem, or concept your chosen material illuminates. Usually you will have the option of grouping items into sections—this helps you indicate comparisons and relationships. You may be able to write a paragraph or so to introduce the focus of each section

Layout of Writing a Literature Review

Generally, the purpose of a review is to analyze critically a segment of a published body of knowledge through summary, classification, and comparison of prior research studies, reviews of literature, and theoretical articles.

Writing the introduction:

In the introduction, you should:

- Define or identify the general topic, issue, or area of concern, thus providing an appropriate context for reviewing the literature.

- Point out overall trends in what has been published about the topic; or conflicts in theory, methodology, evidence, and conclusions; or gaps in research and scholarship; or a single problem or new perspective of immediate interest.

- Establish the writer’s reason (point of view) for reviewing the literature; explain the criteria to be used in analyzing and comparing literature and the organization of the review (sequence); and, when necessary, state why certain literature is or is not included (scope).

Writing the body:

In the body, you should:

- Group research studies and other types of literature (reviews, theoretical articles, case studies, etc.) according to common denominators such as qualitative versus quantitative approaches, conclusions of authors, specific purpose or objective, chronology, etc.

- Summarize individual studies or articles with as much or as little detail as each merits according to its comparative importance in the literature, remembering that space (length) denotes significance.

- Provide the reader with strong “umbrella” sentences at beginnings of paragraphs, “signposts” throughout, and brief “so what” summary sentences at intermediate points in the review to aid in understanding comparisons and analyses.

WRITING TIP: As you are writing the literature review you will mention the author names and the publication years in your text, but you will still need to compile comprehensive list citations for each entry at the end of your review. Follow APA, MLA, or Chicago style guidelines , as your course requires.

Writing the conclusion:

In the conclusion, you should:

- Summarize major contributions of significant studies and articles to the body of knowledge under review, maintaining the focus established in the introduction.

- Evaluate the current “state of the art” for the body of knowledge reviewed, pointing out major methodological flaws or gaps in research, inconsistencies in theory and findings, and areas or issues pertinent to future study.

- Conclude by providing some insight into the relationship between the central topic of the literature review and a larger area of study such as a discipline, a scientific endeavor, or a profession.

- The Interprofessional Health Sciences Library

- 123 Metro Boulevard

- Nutley, NJ 07110

- [email protected]

- Student Services

- Parents and Families

- Career Center

- Web Accessibility

- Visiting Campus

- Public Safety

- Disability Support Services

- Campus Security Report

- Report a Problem

- Login to LibApps

College & Research Libraries ( C&RL ) is the official, bi-monthly, online-only scholarly research journal of the Association of College & Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association.

C&RL is now on Instragram! Follow us today.

LuMarie Guth is an Associate Professor and Business Librarian at Western Michigan University, email: [email protected] .

Bradford Dennis is an Associate Professor and Education and Human Development Librarian at Western Michigan University, email: [email protected] .

C&RL News

ALA JobLIST

Advertising Information

- Research is an Activity and a Subject of Study: A Proposed Metaconcept and Its Practical Application (76674 views)

- Information Code-Switching: A Study of Language Preferences in Academic Libraries (39950 views)

- Three Perspectives on Information Literacy in Academia: Talking to Librarians, Faculty, and Students (28431 views)

Student Stress and the Research Consultation: The Effect of the Research Consultation on Project Stress and Overall Stress and Applications for Student Wellness

LuMarie Guth and Bradford Dennis *

Academic libraries have conducted studies on the importance of the library research consultation (LRC) regarding student learning and the impact on academic success. While there is a robust literature examining library anxiety, no study has been designed to measure the impact of the library research consultation on stress. Researchers at a mid-sized midwestern Carnegie Research 2 institution analyzed 108 surveys administered before and after the consultation. Findings confirm the LRC improves perceived stress levels at the project and overall level. The overall stress change and project stress levels were lower during the COVID phase of the study.

Introduction

Faculty reported that—two years into the pandemic—students continued to face heightened stress and burnout. 1 Gen Z (born 1997 and later) 2 students are present at all levels of the undergraduate curriculum. According to the American Psychological Association (APA) 2018 Stress in America survey—in its report introducing Gen Z—91 percent of Gen Z respondents claimed to have experienced physical or emotional symptoms due to stress, compared to 74 percent of adults overall. Gen Z adults were also more likely than other generations at similar life stages to report that they have been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (18 percent of Gen Z) and/or depression (23 percent of Gen Z). 3 Several studies indicate that college student mental health is a contributor to student retention and academic success. 4 Therefore it is in the best interest of the student and the university to address mental wellness. Faculty knowledge of mental health disorders, 5 along with direct expressions of concern and support, 6 can have a positive impact on student mental health and academic success. Likewise, it has been the experience of this study’s researchers that students express a sense of relief upon finishing a research consultation with academic librarians. However, is this just anecdotal? Is it possible to demonstrate that librarians leading the research consultation can have a positive impact on student stress reduction? In summer 2019 early results were being filtered out from a campus-wide survey and series of listening sessions indicating that students on campus wanted additional mental wellness support. Early discussions centered around building a campus referral system to a “wellness wheel” of services, such as tutoring, recreation, and counseling. The researchers saw an opportunity to investigate their anecdotal experiences to see if the research consultation could serve as an effective option, among others, for triaging academic stress. The library—as an academic service on campus—has a mission to contribute to student success by providing the resources and services they need for their academic research. One such service is the library research consultation, which students can schedule to get individual assistance for their project(s). The consultation differs from the reference interview in that it is pre-scheduled versus conducted at a drop-in point-of-service. Since there is dedicated time allotted for the consultation, there is more flexibility to guide the patron through the research process and to impart information literacy skills. In the consultation, the librarian typically works with the student to develop their topic, determine the best research strategy, conduct initial searches to find sources, and evaluate the sources found for relevancy.

The researchers began their investigation in the fall of 2019 and paused collecting data when the university announced a move to fully remote instruction in March 2020. When it was evident that the pandemic would be long term, the researchers recognized the opportunity to include analysis of pre- and post-COVID data to measure its effect, if any. They conducted a second round of data collection from October 2020 to March 2021 while most classes were online and library research consultations were exclusively offered virtually.

Literature Review

Students and faculty believe the research consultation is helpful in learning library research skills 7 and is an important factor in academic success. 8 However, research linking the consultation with academic success metrics has been mixed. A University of Minnesota study on library use and academic success did not find any significant differences in GPA or retention between those who scheduled a peer research consultation and those who did not. 9 A similar study at University of Wisconsin—Eau Claire found that students who used reference consultations earned marginally higher grade point averages than non-library users. 10 Researchers at the University of Northern Iowa examined the effect of the research consultation on course performance and found that students who had research consultations had higher course grades than those who had not. However, they also found that students seeking consultations were more likely to live on campus and be full-time students, introducing the prospect of sampling bias in analysis of the effect of research consultations on academic success since students who are already more likely to succeed academically may be more likely to seek out a research consultation. 11

Kuhlthau’s ISP model offers an early examination of emotions experienced during the research process. In the origin study at Rutgers, Kuhlthau surveyed and interviewed high school seniors in AP English classes on their research process, and developed a new model for the information search process (ISP) which mapped each stage to a series of emotions. 12 Kuhlthau’s ISP model argues that feelings of uncertainty increase after the initial optimism of the topic selection stage as students begin searching for sources. However, as the topic becomes more focused and students gather more pertinent information—as typically happens during the research consultation—feelings of clarity and confidence emerge, followed by relief at the end of the information gathering process, and then final satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the commencement of the writing of the paper. Further testing of this model on users from a range of libraries found that academic participants showed the largest growth in confidence from the initiation to closure of the search project. 13 An advantage of the research consultation is that it expedites the information gathering process to move students more quickly to clarity and confidence.

Mellon constructed a grounded theory of “library anxiety” drawing on data collected from 6000 students over two years by 20 English professors. Three concepts emerged from these descriptions: 1. students generally feel that their own library-use skills are inadequate while the skills of other students are adequate; 2. the inadequacy is shameful and should be hidden; and 3. the inadequacy would be revealed by asking questions. 14 Bostick developed the Library Anxiety Scale 15 and researchers administered it to 493 students at two US universities; they found that library-anxious students tend to experience negative emotions such as fear, apprehension, and mental disorganization, therefore limiting their ability to use the library effectively. 16 Frustration associated with the search for information resources in libraries or information systems is one of the most prevalent forms of academic anxiety because most students are required to conduct research as a part of their academic program. 17 Researchers at Kent State found that 50 percent of respondents in first-year writing classes were, “mostly sure about how to begin a general search for information,” but 48 percent agreed or strongly agreed they were, “unsure about how to begin research;” 63 percent of respondents felt “uncomfortable searching for information,” and 67 percent did “not want to learn how to do their own research.” 18 These numbers reflect a persistent need to work with students to make them more comfortable and confident in their research. Library anxiety and research performance are inversely related, and library anxiety represents a negative experience for the student. 19 Experiencing a successful search could lead to a reduction in search anxiety. 20

Recent studies have shown that course instructors can play a role in recognizing and supporting students with mental health disorders by referring them to resources on campus. 21 As instructors, librarians can help minimize the effect of research anxiety, or “library anxiety.” 22 Kracker developed and administered a Research Process Survey based on Kuhlthau’s ISP model along with a standard anxiety test to a writing course at the University of Tennessee—Knoxville. The study found a significant decrease in anxiety about the research paper assignment in the test group after a 30-minute presentation on the ISP model, compared to the control. This finding indicates that instruction on the research process and on the expected emotions of that process, can mitigate negative emotions. 23 Students are less anxious when they know what they are experiencing is normal.

Student perceive the research consultation as a learning experience that extends beyond information literacy in the classroom. 24 Students undergoing the research consultation view the librarian as a teacher, and agree that the consultation helps improve their skills in conducting a literature search. A particular benefit of the consultation is modelling how to address the natural challenges of the research process. 25 The research consultation is an important service because it occurs at a point of need. Students often seek out the research consultation after already attempting research and meeting with challenges, 26 and frequently cite time savings as a benefit. 27 Reinsfelder 28 describes the unique advantages of the consultation: “the method of instruction can be quite effective and is used frequently by on-campus tutors and writing centers because these personal meetings allow for greater attention to detail and the ability to address unique concerns of each student in a way that is not possible in larger groups.”

Several studies have found that students report increased research confidence after the consultation 29 and this confidence can have lasting effects beyond the project at hand. 30 Fewer studies investigate the effect of the research consultation on stress and anxiety and, when they do, it is not the central focus of the study. In a small study at Colorado State University—Pueblo undergraduate participants exhibited mild decreases in library anxiety over the course of one semester. However, the study included both instruction and consultation and it was not determined which had a greater impact on anxiety, if any. 31 In a study conducted at Utah State University, 80 percent of students who expressed library anxiety prior to the consultation were comforted by the professional knowledge of the librarian. 32 Although the central focus of their research was not stress, Magi and Mardeusz 33 —in their qualitative study at the University of Vermont—found, after coding the open ended comments, that students reported increased confidence and reduced stress after the consultation. Of the 52 students in the study, more than one-third said they felt overwhelmed before the consultation and about 20 percent referenced a feeling of stress or anxiety in their comments. After the consultation all but one remarked on a positive change. Responses in the appendix show 40 percent of the students mentioned feelings of confidence/readiness/preparedness, and about 20 percent mentioned feelings of relief or relaxation after the consultation.

The observation of heightened stress for Gen Z in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic is supported by the findings in the APA 2020 Stress and America report. Gen Z adults (aged 18–23 in 2020) reported high levels of stress with a 6.1 rating on a 10-point scale, compared to 5.0 for all adults. Eighty-two percent of Gen Z adults in college said that the uncertainty going into the 2020–21 school year would likely result in stress. 34 However, in the 2021 study Gen Z stress levels had lowered to 5.6, the second highest cohort after Millennials. Several studies have found that COVID-19 directly affected student stress levels. Active Minds surveyed undergraduate students in September 2020 and found that 89 percent reported that COVID-19 has had an impact on their stress/anxiety levels. When asked what the most stressful factor was, college students ranked having troubles focusing on studies and/or work as the third highest stress factor at 14 percent. 35 In interviews of undergraduates at Texas A&M in April 2020, 71 percent of respondents reported that their stress and anxiety had increased due to COVID-19, 89 percent of respondents reported difficulty concentrating, and 82 percent were concerned about their academic performance. 36 In contrast, a study comparing measurements before and after the University of Vermont moved all instruction online due to COVID-19 did not find significant changes in stress levels in their study. They hypothesized that the lack of stress changes could be attributed to moving back home, or to the additional pandemic-related accommodations instructors provided. 37

Methodology and Demographics

Students who scheduled a research consultation with four of the nine instruction liaison librarians at Western Michigan University were invited to participate in the study, which was reviewed and approved through the IRB process. These four librarians served the areas of fine arts, business, health sciences, and education and were selected because of their breadth of disciplines, as well as their history of having a high volume of research consultations. Study participants were not asked why they sought the consultation, but there are a variety of incentives at the university. In some classes it is required. In others the instructor recommends the service, particularly when a student is struggling, or offers extra credit for using the service. Students in the business college can use the research consultation as an option for obtaining a badge in a microlearning credentials program. Multiple librarians at the university have reported that students seek consultations for individual assistance after an instruction session was delivered to their class. There were 209 students eligible for participation and 108 opted into the study resulting in a response rate of 52 percent. The pre- and post- questionnaires were on the same Qualtrics web-based survey with a page in between asking students to keep the tab open and pause to resume the session. Prior to the study students were asked to self-report their feelings related to their project with the question: “How much stress do you feel about this project?” (possible responses were: None at all (1), A little (2), A moderate amount (3), A lot (4), A great deal (5)); and were asked about their overall stress via the question: “How much overall stress do you feel this semester?” (possible responses were: None at all (1), A little (2), A moderate amount (3), A lot (4), A great deal (5)). Definitions of project and overall stress were not provided, leaving interpretation to the students. Immediately after the consultation students were asked to report how their project and overall stress levels had changed with the questions: “How is your project stress after the research consultation?” (possible responses were: Much better (5), Somewhat better (4), About the same (3), Somewhat worse (2), Much worse (1)), and “How is your overall stress after the research consultation?” (possible responses were: Much better (5), Somewhat better (4), About the same (3), Somewhat worse (2), Much worse (1)). The study launched in week six of the fall 2019 semester and was suspended in week ten of the spring 2020 semester when it was announced that the following week campus would move to virtual services because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study resumed in week six of the fall 2020 semester and ended in week ten of the spring 2021 semester to measure changes in reported project and overall stress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The weeks correspond to late October and early March. During the study period prior to the pandemic, the four librarians collecting responses for the study conducted 92 percent of their consultations in-person and none via web conferencing; while during the pandemic none of their consultations were in-person and 93 percent were via web conference. Other mediums for consultations included IM/Chat and phone.

SPSS version 27 was used in analysis of the data. The researchers consulted with the Associate Director of the Office of Institutional Research on the appropriate statistical tests, following up to verify the validity of the findings. Three of the factors were condensed in order to increase within-group sample size. Class standing was reduced from five categories (first year, sophomore, junior, senior, and graduate student) to three categories (first year/sophomore, junior/senior, and graduate student). Project stress and overall stress were reduced from five categories to two categories: low (none at all/a little/a moderate amount) and high (a lot/a great deal). Additionally, project stress change and overall stress change were transformed from much worse, somewhat worse, about the same, somewhat better, and much better to –2, –1, 0, 1, and 2 respectively to quantify the magnitude and direction of change of respondents from their previous state.

Of the 108 respondents, 43 percent (n=46) took the survey before the COVID-19 closures in Michigan and 57 percent (n=62) of respondents took the survey during the COVID-19 pandemic when library services and most courses were offered virtually. Eighty-five respondents gave their age. The ages of respondents ranged from a minimum of 17 to a maximum of 50 with a mean of 22.2 and standard deviation of 4.6. The ages and dates of participation were used to sort students into generations. Seventy-nine percent (n=67) of respondents who gave their age were from Gen Z, 19 percent (n=16) were Millennials, and 2 percent (n=2) were from Gen X.

Class Standing

Twelve percent (n=13) of respondents were first years/sophomores, 76 percent (n=82) were juniors/seniors, and 12 percent (n=13) were graduate students. This indicates that the primary audience for the research consultation service, at least among librarians in the study, is juniors/seniors.

There was a significant association between COVID and class standing (x 2 (2)=10.306, p =.006), as exhibited in table 1. More respondents than expected were graduate students before COVID (late October 2019 through early March 2020), and there were more first years/sophomores than expected during the COVID phase of the study (late October 2020 through early March 2021). Examining LibAnswers consultation reporting statistics of librarians in the study, there were many more undergraduate consultations (178 versus 78) and slightly more graduate consultations (18 versus 16) during the COVID phase. While the researchers do not have an explanation for the change in graduate students, there was a first-year class that was strongly encouraged to meet with one of the librarians in the study during the COVID phase.

| Table 1 | |||||

| Class Standing and COVID (n=108) | |||||

| Class Standing | |||||

| First Year / Sophomore (n=13) | Junior / Senior (n=82) | Graduate Student (n=13) | |||

| COVID | Before (n=46) | Count | 1 | 36 | 9 |

| Expected Count | 5.5 | 34.9 | 5.5 | ||

| During (n=62) | Count | 12 | 46 | 4 | |

| Expected Count | 7.5 | 47.1 | 7.5 | ||

Stress Change

The primary interest of the study was to observe whether or not students reported an improvement in perceived stress after the research consultation. Thirty-seven percent (n=40) of respondents reported high levels of project stress and 64 percent (n=69) reported high levels of overall stress before the consultation. Respondents reported an improvement in both project stress and overall stress after the research consultation. Frequencies can be seen in figures 1 and 2. Respondents in the study experienced a mean positive change in project stress of 1.5 units and a mean positive change in overall stress of 1.2 units.

Chi-square Goodness of Fit Test Analysis

Using crosstabs, the researchers performed a chi-square goodness of fit test to explore associations between the variables and found significant associations between: 1. Project Stress and Covid; 2. Overall Stress Change and COVID; 3. Project Stress and Overall Stress; and 4. Project Stress Change and Overall Stress Change. One area of interest was whether participants in the study demonstrated higher levels of stress during the COVID phase of the study than in the pre-COVID phase.

| Figure 1 |

| Project Stress Change Histogram |

|

|

| Figure 2 |

| Overall Stress Change Histogram |

|

|

There was a significant association between COVID and project stress before the consultation (x 2 (1)=10.297, p =.001), but the data showed there were more respondents than expected reporting high project stress before COVID (late October 2019 through early March 2020). Likewise, more respondents than expected reported low project stress during COVID (late October 2020 through early March 2021) as shown in table 2. A similar analysis on overall stress before the consultation did not show a significant association with COVID.

| Table 2 | ||||

| Project Stress and COVID (n=108) | ||||

| Project Stress | ||||

| Low (1–3) (n=68) | High (4–5) (n=40) | |||

| COVID | Before (n=46) | Count | 21 | 25 |

| Expected Count | 29 | 17 | ||

| During (n=62) | Count | 47 | 15 | |