Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Steps in the literature review process.

- What is a literature review?

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

- You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

- Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

- Finalize your research question

- Think about relevant dates, geographies (and languages), methods, and conflicting points of view

- Conduct searches in the published literature via the identified databases

- Check to see if this topic has been covered in other discipline's databases

- Examine the citations of on-point articles for keywords, authors, and previous research (via references) and cited reference searching.

- Save your search results in a citation management tool (such as Zotero, Mendeley or EndNote)

- De-duplicate your search results

- Make sure that you've found the seminal pieces -- they have been cited many times, and their work is considered foundational

- Check with your professor or a librarian to make sure your search has been comprehensive

- Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of individual sources and evaluate for bias, methodologies, and thoroughness

- Group your results in to an organizational structure that will support why your research needs to be done, or that provides the answer to your research question

- Develop your conclusions

- Are there gaps in the literature?

- Where has significant research taken place, and who has done it?

- Is there consensus or debate on this topic?

- Which methodological approaches work best?

- For example: Background, Current Practices, Critics and Proponents, Where/How this study will fit in

- Organize your citations and focus on your research question and pertinent studies

- Compile your bibliography

Note: The first four steps are the best points at which to contact a librarian. Your librarian can help you determine the best databases to use for your topic, assess scope, and formulate a search strategy.

Videos Tutorials about Literature Reviews

This 4.5 minute video from Academic Education Materials has a Creative Commons License and a British narrator.

Recommended Reading

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved July 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- Six Steps to Writing a Literature Review

- Finding Articles

- Try A Citation Manager

- Avoiding Plagiarism

Selecting a Research Topic

The first step in the process involves exploring and selecting a topic. You may revise the topic/scope of your research as you learn more from the literature. Be sure to select a topic that you are willing to work with for a considerable amount of time.

When thinking about a topic, it is important to consider the following:

Does the topic interest you?

Working on something that doesn’t excite you will make the process tedious. The research content should reflect your passion for research so it is essential to research in your area of interest rather than choosing a topic that interests someone else. While developing your research topic, broaden your thinking and creativity to determine what works best for you. Consider an area of high importance to your profession, or identify a gap in the research. It may take some time to narrow down on a topic and get started, but it’s worth the effort.

Is the Topic Relevant?

Be sure your subject meets the assignment/research requirements. When in doubt, review the guidelines and seek clarification from your professor.

What is the Scope and Purpose?

Sometimes your chosen topic may be too broad. To find direction, try limiting the scope and purpose of the research by identifying the concepts you wish to explore. Once this is accomplished, you can fine-tune your topic by experimenting with keyword searches our A-Z Databases until you are satisfied with your retrieval results.

Are there Enough Resources to Support Your Research?

If the topic is too narrow, you may not be able to provide the depth of results needed. When selecting a topic make sure you have adequate material to help with the research. Explore a variety of resources: journals, books, and online information.

Adapted from https://jgateplus.com/home/2018/10/11/the-dos-of-choosing-a-research-topic-part-1/

Why use keywords to search?

- Library databases work differently than Google. Library databases work best when you search for concepts and keywords.

- For your research, you will want to brainstorm keywords related to your research question. These keywords can lead you to relevant sources that you can use to start your research project.

- Identify those terms relevant to your research and add 2-3 in the search box.

Now its time to decide whether or not to incorporate what you have found into your literature review. E valuate your resources to make sure they contain information that is authoritative, reliable, relevant and the most useful in supporting your research.

Remember to be:

- Objective : keep an open mind

- Unbiased : Consider all viewpoints, and include all sides of an argument, even ones that don't support your own

Criteria for Evaluating Research Publications

Significance and Contribution to the Field

• What is the author’s aim?

• To what extent has this aim been achieved?

• What does this text add to the body of knowledge? (theory, data and/or practical application)

• What relationship does it bear to other works in the field?

• What is missing/not stated?

• Is this a problem?

Methodology or Approach (Formal, research-based texts)

• What approach was used for the research? (eg; quantitative or qualitative, analysis/review of theory or current practice, comparative, case study, personal reflection etc…)

• How objective/biased is the approach?

• Are the results valid and reliable?

• What analytical framework is used to discuss the results?

Argument and Use of Evidence

• Is there a clear problem, statement or hypothesis?

• What claims are made?

• Is the argument consistent?

• What kinds of evidence does the text rely on?

• How valid and reliable is the evidence?

• How effective is the evidence in supporting the argument?

• What conclusions are drawn?

• Are these conclusions justified?

Writing Style and Text Structure

• Does the writing style suit the intended audience? (eg; expert/non-expert, academic/non- academic)

• What is the organizing principle of the text?

- Could it be better organized?

Prepared by Pam Mort, Lyn Hallion and Tracey Lee Downey, The Learning Centre © April 2005 The University of New South Wales.

Analysis: the Starting Point for Further Analysis & Inquiry

After evaluating your retrieved sources you will be ready to explore both what has been found and what is missing . Analysis involves breaking the study into parts, understanding each part, assessing the strength of evidence, and drawing conclusions about its relationship to your topic.

Read through the information sources you have selected and try to analyze, understand and critique what you read. Critically review each source's methods, procedures, data validity/reliability, and other themes of interest. Consider how each source approaches your topic in addition to their collective points of intersection and separation . Offer an appraisal of past and current thinking, ideas, policies, and practices, identify gaps within the research, and place your current work and research within this wider discussion by considering how your research supports, contradicts, or departs from other scholars’ research and offer recommendations for future research.

Top 10 Tips for Analyzing the Research

- Define key terms

- Note key statistics

- Determine emphasis, strengths & weaknesses

- Critique research methodologies used in the studies

- Distinguish between author opinion and actual results

- Identify major trends, patterns, categories, relationships, and inconsistencies

- Recognize specific aspects in the study that relate to your topic

- Disclose any gaps in the literature

- Stay focused on your topic

- Excluding landmark studies, use current, up-to-date sources

Prepared by the fine librarians at California State University Sacramento.

Synthesis vs Summary

Your literature review should not simply be a summary of the articles, books, and other scholarly writings you find on your topic. It should synthesize the various ideas from your sources with your own observations to create a map of the scholarly conversation taking place about your research topics along with gaps or areas for further research.

Bringing together your review results is called synthesis. Synthesis relies heavily on pattern recognition and relationships or similarities between different phenomena. Recognizing these patterns and relatedness helps you make creative connections between previously unrelated research and identify any gaps.

As you read, you'll encounter various ideas, disagreements, methods, and perspectives which can be hard to organize in a meaningful way. A synthesis matrix also known as a Literature Review Matrix is an effective and efficient method to organize your literature by recording the main points of each source and documenting how sources relate to each other. If you know how to make an Excel spreadsheet, you can create your own synthesis matrix, or use one of the templates below.

Because a literature review is NOT a summary of these different sources, it can be very difficult to keep your research organized. It is especially difficult to organize the information in a way that makes the writing process simpler. One way that seems particularly helpful in organizing literature reviews is the synthesis matrix. Click on the link below for a short tutorial and synthesis matrix spreadsheet.

- Literature Review and Synthesis

- Lit Review Synthesis Matrix

- Synthesis Matrix Example

A literature review must include a thesis statement, which is your perception of the information found in the literature.

A literature review:

- Demonstrates your thorough investigation of and acquaintance with sources related to your topic

- Is not a simple listing, but a critical discussion

- Must compare and contrast opinions

- Must relate your study to previous studies

- Must show gaps in research

- Can focus on a research question or a thesis

- Includes a compilation of the primary questions and subject areas involved

- Identifies sources

https://custom-writing.org/blog/best-literature-review

Organizing Your Literature Review

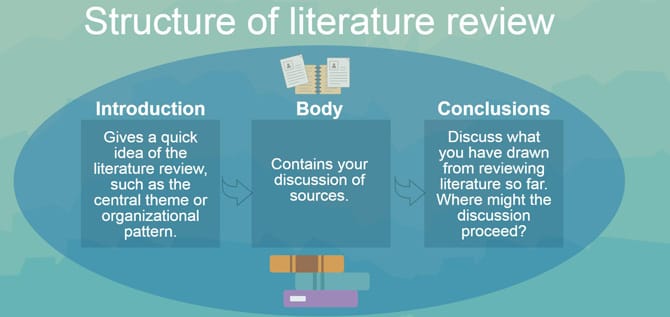

The structure of the review is divided into three main parts—an introduction, body, and the conclusion.

Introduction

Discuss what is already known about your topic and what readers need to know in order to understand your literature review.

- Scope, Method, Framework: Explain your selection criteria and similarities between your sources. Be sure to mention any consistent methods, theoretical frameworks, or approaches.

- Research Question or Problem Statement: State the problem you are addressing and why it is important. Try to write your research question as a statement.

- Thesis : Address the connections between your sources, current state of knowledge in the field, and consistent approaches to your topic.

- Format: Describe your literature review’s organization and adhere to it throughout.

Body

The discussion of your research and its importance to the literature should be presented in a logical structure.

- Chronological: Structure your discussion by the literature’s publication date moving from the oldest to the newest research. Discuss how your research relates to the literature and highlight any breakthroughs and any gaps in the research.

- Historical: Similar to the chronological structure, the historical structure allows for a discussion of concepts or themes and how they have evolved over time.

- Thematic: Identify and discuss the different themes present within the research. Make sure that you relate the themes to each other and to your research.

- Methodological: This type of structure is used to discuss not so much what is found but how. For example, an methodological approach could provide an analysis of research approaches, data collection or and analysis techniques.

Provide a concise summary of your review and provide suggestions for future research.

Writing for Your Audience

Writing within your discipline means learning:

- the specialized vocabulary your discipline uses

- the rhetorical conventions and discourse of your discipline

- the research methodologies which are employed

Learn how to write in your discipline by familiarizing yourself with the journals and trade publications professionals, researchers, and scholars use.

Use our Databases by Title to access:

- The best journals

- The most widely circulated trade publications

- The additional ways professionals and researchers communicate, such as conferences, newsletters, or symposiums.

- << Previous: What is a Literature Review?

- Next: Finding Articles >>

- Last Updated: Jan 18, 2024 1:14 PM

- URL: https://niagara.libguides.com/litreview

The Research Process: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Evaluate Sources

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- How to Read Research Article

- ChatGPT and the Research Process

Academic Success Center

Academic Success Center Contact the Academic Success Center for tutoring hours for writing.

Organize the literature review into sections that present themes or identify trends, including relevant theory. You are not trying to list all the material published, but to synthesize and evaluate it according to the guiding concept of your thesis or research question.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. Occasionally you will be asked to write one as a separate assignment, but more often it is part of the introduction to an essay, research report, or thesis. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries

A literature review must do these things:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you are developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Ask yourself questions like these:

- What is the specific thesis, problem, or research question that my literature review helps to define?

- What type of literature review am I conducting? Am I looking at issues of theory? methodology? policy? quantitative research (e.g. on the effectiveness of a new procedure)? qualitative research (e.g., studies of loneliness among migrant workers)?

- What is the scope of my literature review? What types of publications am I using (e.g., journals, books, government documents, popular media)? What discipline am I working in (e.g., nursing psychology, sociology, medicine)?

- How good was my information seeking? Has my search been wide enough to ensure I've found all the relevant material? Has it been narrow enough to exclude irrelevant material? Is the number of sources I've used appropriate for the length of my paper?

- Have I critically analyzed the literature I use? Do I follow through a set of concepts and questions, comparing items to each other in the ways they deal with them? Instead of just listing and summarizing items, do I assess them, discussing strengths and weaknesses?

- Have I cited and discussed studies contrary to my perspective?

- Will the reader find my literature review relevant, appropriate, and useful?

Ask yourself questions like these about each book or article you include:

- Has the author formulated a problem/issue?

- Is it clearly defined? Is its significance (scope, severity, relevance) clearly established?

- Could the problem have been approached more effectively from another perspective?

- What is the author's research orientation (e.g., interpretive, critical science, combination)?

- What is the author's theoretical framework (e.g., psychological, developmental, feminist)?

- What is the relationship between the theoretical and research perspectives?

- Has the author evaluated the literature relevant to the problem/issue? Does the author include literature taking positions she or he does not agree with?

- In a research study, how good are the basic components of the study design (e.g., population, intervention, outcome)? How accurate and valid are the measurements? Is the analysis of the data accurate and relevant to the research question? Are the conclusions validly based upon the data and analysis?

- In material written for a popular readership, does the author use appeals to emotion, one-sided examples, or rhetorically-charged language and tone? Is there an objective basis to the reasoning, or is the author merely "proving" what he or she already believes?

- How does the author structure the argument? Can you "deconstruct" the flow of the argument to see whether or where it breaks down logically (e.g., in establishing cause-effect relationships)?

- In what ways does this book or article contribute to our understanding of the problem under study, and in what ways is it useful for practice? What are the strengths and limitations?

- How does this book or article relate to the specific thesis or question I am developing?

Text written by Dena Taylor, Health Sciences Writing Centre, University of Toronto

http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review

- << Previous: Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Step 5: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jun 26, 2024 1:35 PM

- URL: https://westlibrary.txwes.edu/research/process

How to Write a Literature Review

- What Is a Literature Review

- What Is the Literature

Writing the Review

Why Are You Writing This?

There are two primary points to remember as you are writing your literature review:

- Stand-alone review: provide an overview and analysis of the current state of research on a topic or question

- Research proposal: explicate the current issues and questions concerning a topic to demonstrate how your proposed research will contribute to the field

- Research report: provide the context to which your work is a contribution.

- Write as you read, and revise as you read more. Rather than wait until you have read everything you are planning to review, start writing as soon as you start reading. You will need to reorganize and revise it all later, but writing a summary of an article when you read it helps you to think more carefully about the article. Having drafts and annotations to work with will also make writing the full review easier since you will not have to rely completely on your memory or have to keep thumbing back through all the articles. Your draft does not need to be in finished, or even presentable, form. The first draft is for you, so you can tell yourself what you are thinking. Later you can rewrite it for others to tell them what you think.

General Steps for Writing a Literature Review

Here is a general outline of steps to write a thematically organized literature review. Remember, though, that there are many ways to approach a literature review, depending on its purpose.

- Stage one: annotated bibliography. As you read articles, books, etc, on your topic, write a brief critical synopsis of each. After going through your reading list, you will have an abstract or annotation of each source you read. Later annotations are likely to include more references to other works since you will have your previous readings to compare, but at this point the important goal is to get accurate critical summaries of each individual work.

- Stage two: thematic organization. Find common themes in the works you read, and organize the works into categories. Typically, each work you include in your review can fit into one category or sub-theme of your main theme, but sometimes a work can fit in more than one. (If each work you read can fit into all the categories you list, you probably need to rethink your organization.) Write some brief paragraphs outlining your categories, how in general the works in each category relate to each other, and how the categories relate to each other and to your overall theme.

- Stage three: more reading. Based on the knowledge you have gained in your reading, you should have a better understanding of the topic and of the literature related to it. Perhaps you have discovered specific researchers who are important to the field, or research methodologies you were not aware of. Look for more literature by those authors, on those methodologies, etc. Also, you may be able to set aside some less relevant areas or articles which you pursued initially. Integrate the new readings into your literature review draft. Reorganize themes and read more as appropriate.

- Stage four: write individual sections. For each thematic section, use your draft annotations (it is a good idea to reread the articles and revise annotations, especially the ones you read initially) to write a section which discusses the articles relevant to that theme. Focus your writing on the theme of that section, showing how the articles relate to each other and to the theme, rather than focusing your writing on each individual article. Use the articles as evidence to support your critique of the theme rather than using the theme as an angle to discuss each article individually.

- Stage five: integrate sections. Now that you have the thematic sections, tie them together with an introduction, conclusion, and some additions and revisions in the sections to show how they relate to each other and to your overall theme.

Specific Points to Include

More specifically, here are some points to address when writing about specific works you are reviewing. In dealing with a paper or an argument or theory, you need to assess it (clearly understand and state the claim) and analyze it (evaluate its reliability, usefulness, validity). Look for the following points as you assess and analyze papers, arguments, etc. You do not need to state them all explicitly, but keep them in mind as you write your review:

- Be specific and be succinct. Briefly state specific findings listed in an article, specific methodologies used in a study, or other important points. Literature reviews are not the place for long quotes or in-depth analysis of each point.

- Be selective. You are trying to boil down a lot of information into a small space. Mention just the most important points (i.e. those most relevant to the review's focus) in each work you review.

- Is it a current article? How old is it? Have its claims, evidence, or arguments been superceded by more recent work? If it is not current, is it important for historical background?

- What specific claims are made? Are they stated clearly?

- What evidence, and what type (experimental, statistical, anecdotal, etc) is offered? Is the evidence relevant? sufficient?

- What arguments are given? What assumptions are made, and are they warranted?

- What is the source of the evidence or other information? The author's own experiments, surveys, etc? Historical records? Government documents? How reliable are the sources?

- Does the author take into account contrary or conflicting evidence and arguments? How does the author address disagreements with other researchers?

- What specific conclusions are drawn? Are they warranted by the evidence?

- How does this article, argument, theory, etc, relate to other work?

These, however, are just the points that should be addressed when writing about a specific work. It is not an outline of how to organize your writing. Your overall theme and categories within that theme should organize your writing, and the above points should be integrated into that organization. That is, rather than write something like:

Smith (2019) claims that blah, and provides evidence x to support it, and says it is probably because of blip. But Smith seems to have neglected factor b. Jones (2021) showed that blah by doing y, which, Jones claims, means it is likely because of blot. But that methodology does not exclude other possibilities. Johnson (2022) hypothesizes blah might be because of some other cause.

list the themes and then say how each article relates to that theme. For example:

Researchers agree that blah (Smith 2019, Jones 2021, Johnson 2022), but they do not agree on why. Smith claims it is probably due to blip, but Jones, by doing y, tries to show it is likely because of blot. Jones' methodology, however, does not exclude other possibilities. Johnson hypothesizes ...

- << Previous: What Is the Literature

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

Graduate Research: Guide to the Literature Review

- "Literature review" defined

- Research Communication Graphic

- Literature Review Steps

- Search techniques

- Finding Additional "Items

- Evaluating information

- Citing Styles

- Ethical Use of Information

- Research Databases This link opens in a new window

- Get Full Text

- Reading a Scholarly Article

- Author Rights

- Selecting a publisher

Introduction to Research Process: Literature Review Steps

When seeking information for a literature review or for any purpose, it helps to understand information-seeking as a process that you can follow. 5 Each of the six (6) steps has its own section in this web page with more detail. Do (and re-do) the following six steps:

1. Define your topic. The first step is defining your task -- choosing a topic and noting the questions you have about the topic. This will provide a focus that guides your strategy in step II and will provide potential words to use in searches in step III.

2. Develop a strategy. Strategy involves figuring out where the information might be and identifying the best tools for finding those types of sources. The strategy section identifies specific types of research databases to use for specific purposes.

3. Locate the information . In this step, you implement the strategy developed in II in order to actually locate specific articles, books, technical reports, etc.

4. Use and Evaluate the information. Having located relevant and useful material, in step IV you read and analyze the items to determine whether they have value for your project and credibility as sources.

5. Synthesize. In step V, you will make sense of what you've learned and demonstrate your knowledge. You will thoroughly understand, organize and integrate the information --become knowledgeable-- so that you are able to use your own words to support and explain your research project and its relationship to existing research by others.

6. Evaluate your work. At every step along the way, you should evaluate your work. However, this final step is a last check to make sure your work is complete and of high quality.

Continue below to begin working through the process.

5. Eisenberg, M. B., & Berkowitz, R. E. (1990). Information Problem-Solving: the Big Six Skills Approach to Library & Information Skills Instruction . Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

1. Define your topic.

I. Define your topic

A. Many students have difficulty selecting a topic. You want to find a topic you find interesting and will enjoy learning more about.

B. Students often select a topic that is too broad. You may have a broad topic in mind initially and will need to narrow it.

1. To help narrow a broad topic :

a. Brainstorm.

1). Try this technique for brainstorming to narrow your focus.

a) Step 1. Write down your broad topic.

b) Step 2. Write down a "specific kind" or "specific aspect" of the topic you identified in step 1.

c) Step 3. Write down an aspect --such as an attribute or behavior-- of the "specific kind" you identified in step 2.

d) Step 4. Continue to add levels of specificity as needed to get to a focus that is manageable. However, you may want to begin researching the literature before narrowing further to give yourself the opportunity to explore what others are doing and how that might impact the direction that you take for your own research.

2) Three examples of using the narrowing technique. These examples start with very, very broad topics, so the topic at step 3 or 4 in these examples would be used for a preliminary search in the literature in order to identify a more specific focus. Greater specificity than level 3 or 4 will ultimately be necessary for developing a specific research question. And we may discover in our preliminary research that we need to alter the direction that we originally were taking.

a) Example 1.

Step 1. information security

Step 2. protocols

Step 3. handshake protocol

Brainstorming has brought us to focus on the handshake protocol.

b) Example 2.

Step 1. information security

Step 2. single sign-on authentication

Step 3. analyzing

Step 4. methods

Brainstorming has brought us to focus on methods for analyzing the security of single sign-on authentication

c) Example 3. The diagram below is an example using the broad topic of "software" to show two potential ways to begin to narrow the topic.

C. Once you have completed the brainstorming process and your topic is more focused, you can do preliminary research to help you identify a specific research question .

1) Examine overview sources such as subject-specific encyclopedias and textbooks that are likely to break down your specific topic into sub-topics and to highlight core issues that could serve as possible research questions. [See section II. below on developing a strategy to learn how to find these encyclopedias]

2). Search the broad topic in a research database that includes scholarly journals and professional magazines (to find technical and scholarly articles) and scan recent article titles for ideas. [See section II. below on developing a strategy to learn how to find trade and scholarly journal articles]

D. Once you have identified a research question or questions, ask yourself what you need to know to answer the questions. For example,

1. What new knowledge do I need to gain?

2. What has already been answered by prior research of other scholars?

E. Use the answers to the questions in C. to identify what words to use to describe the topic when you are doing searches.

1. Identify key words

a. For example , if you are investigating "security audits in banking", key terms to combine in your searches would be: security, audits, banking.

2. Create a list of alternative ways of referring to a key word or phrase

a.For example , "information assurance" may be referred to in various ways such as: "information assurance," "information security," and "computer security."

b. Use these alternatives when doing searches.

3. As you are searching, pay attention to how others are writing about the topic and add new words or phrases to your searches if appropriate.

2. Develop a strategy.

II. Develop a strategy for finding the information.

A. Start by considering what types of source might contain the information you need . Do you need a dictionary for definitions? a directory for an address? the history of a concept or technique that might be in a book or specialized encyclopedia? today's tech news in an online tech magazine or newspaper? current research in a journal article? background information that might be in a specialized encyclopedia? data or statistics from a specific organization or website? Note that you will typically have online access to these source types.

B. This section provides a description of some of the common types of information needed for research.

1. For technical and business analysis , look for articles in technical and trade magazines . These articles are written by information technology professionals to help other IT professionals do their jobs better. Content might include news on new developments in hardware or software, techniques, tools, and practical advice. Technical journals are also likely to have product ads relevant to information technology workers and to have job ads. Examples iof technical magazines include Network Computing and IEEE Spectrum .

2. To read original research studies , look for articles in scholarly journals and conference proceedings . They will provide articles written by information technology professionals who are reporting original research; that is, research that has been done by the authors and is being reported for the first time. The audience for original research articles is other information technology scholars and professionals. Examples of scholarly journals include Journal of Applied Security Research , Journal of Management Information Systems , IEEE Transactions on Computers , and ACM Transactions on Information and System Security .

3. For original research being reported to funding agencies , look for technical reports on agency websites. Technical reports are researcher reports to funding agencies about progress on or completion of research funded by the agency.

4. For in-depth, comprehensive information on a topic , look for book-length volumes . All chapters in the book might be written by the same author(s) or might be a collection of separate papers written by different authors.

5. To learn about an unfamiliar topic , use textbooks , specialized encyclopedias and handbooks to get get overviews of topics, history/background, and key issues explained.

6. For instructions for hardware, software, networking, etc., look for manuals that provide step-by-step instructions.

7. For technical details about inventions (devices, instruments, machines), look for patent documents .

C. NOTE - In order to search for and find original research studies, it will help if you understand how information is produced, packaged and communicated within your profession. This is explained in the tab "Research Communication: Graphic."

3. Locate the information.

III. Locate the information

A. Use search tools designed to find the sources you want. Types of sources were described in section II. above.

Always feel free to Ask a librarian for assistance when you have questions about where and how locate the information you need.

B. Evaluate the search results (no matter where you find the information)

1. Evaluate the items you find using at least these 5 criteria:

a. accuracy -- is the information reliable and error free?

1) Is there an editor or someone who verifies/checks the information?

2) Is there adequate documentation: bibliography, footnotes, credits?

3) Are the conclusions justified by the information presented?

b. authority -- is the source of the information reputable?

1) How did you find the source of information: an index to edited/peer-reviewed material, in a bibliography from a published article, etc.?

2) What type of source is it: sensationalistic, popular, scholarly?

c. objectivity -- does the information show bias?

1) What is the purpose of the information: to inform, persuade, explain, sway opinion, advertise?

2) Does the source show political or cultural biases?

d. currency -- is the information current? does it cover the time period you need?

e. coverage -- does it provide the evidence or information you need?

2. Is the search producing the material you need? -- the right content? the right quality? right time period? right geographical location? etc. If not, are you using

a. the right sources?

b. the right tools to get to the sources?

c. are you using the right words to describe the topic?

3. Have you discovered additional terms that should be searched? If so, search those terms.

4. Have you discovered additional questions you need to answer? If so, return to section A above to begin to answer new questions.

4. Use and evaluate the information.

IV. Use the information.

A. Read, hear or view the source

1. Evaluate: Does the material answer your question(s)? -- right content? If not, return to B.

2. Evaluate: Is the material appropriate? -- right quality? If not, return to B.

B. Extract the information from the source : copy/download information, take notes, record citation, keep track of items using a citation manager.

1. Note taking (these steps will help you when you begin to write your thesis and/or document your project.):

a. Write the keywords you use in your searches to avoid duplicating previous searches if you return to search a research database again. Keeping track of keywords used will also save you time if your search is interrupted or you need return and do the search again for some other reason. It will help you remember which search terms worked successfully in which databases

b. Write the citations or record the information needed to cite each article/document you plan to read and use, or make sure that any saved a copy of the article includes all the information needed to cite it. Some article pdf files may not include all of the information needed to cite, and it's a waste of your valuable time to have to go back to search and find the items again in order to be able to cite them. Using citation management software such as EndNote will help keep track of citations and help create bibliographies for your research papers.

c. Write a summary of each article you read and/or why you want to use it.

5. Synthesize.

V. Synthesize.

A. Organize and integrate information from multiple sources

B. Present the information (create report, speech, etc. that communicates)

C. Cite material using the style required by your professor or by the venue (conference, publication, etc.). For help with citation styles, see Guide to Citing Sources . A link to the citing guide is also available in the "Get Help" section on the left side of the Library home page

6. Evaluate your work.

VI. Evaluate the paper, speech, or whatever you are using to communicate your research.

A. Is it effective?

B. Does it meet the requirements?

C. Ask another student or colleague to provide constructive criticism of your paper/project.

- << Previous: Research Communication Graphic

- Next: Search techniques >>

- Last Updated: Apr 15, 2024 3:27 PM

- URL: https://library.dsu.edu/graduate-research

- Process: Literature Reviews

- Literature Review

- Managing Sources

Ask a Librarian

Does your assignment or publication require that you write a literature review? This guide is intended to help you understand what a literature is, why it is worth doing, and some quick tips composing one.

Understanding Literature Reviews

What is a literature review .

Typically, a literature review is a written discussion that examines publications about a particular subject area or topic. Depending on disciplines, publications, or authors a literature review may be:

A summary of sources An organized presentation of sources A synthesis or interpretation of sources An evaluative analysis of sources

A Literature Review may be part of a process or a product. It may be:

A part of your research process A part of your final research publication An independent publication

Why do a literature review?

The Literature Review will place your research in context. It will help you and your readers:

Locate patterns, relationships, connections, agreements, disagreements, & gaps in understanding Identify methodological and theoretical foundations Identify landmark and exemplary works Situate your voice in a broader conversation with other writers, thinkers, and scholars

The Literature Review will aid your research process. It will help you to:

Establish your knowledge Understand what has been said Define your questions Establish a relevant methodology Refine your voice Situate your voice in the conversation

What does a literature review look like?

The Literature Review structure and organization may include sections such as:

An introduction or overview A body or organizational sub-divisions A conclusion or an explanation of significance

The body of a literature review may be organized in several ways, including:

Chronologically: organized by date of publication Methodologically: organized by type of research method used Thematically: organized by concept, trend, or theme Ideologically: organized by belief, ideology, or school of thought

- Find a focus

- Find models

- Review your target publication

- Track citations

- Read critically

- Manage your citations

- Ask friends, faculty, and librarians

Additional Sources

- Reviewing the literature. Project Planner.

- Literature Review: By UNC Writing Center

- PhD on Track

- CU Graduate Students Thesis & Dissertation Guidance

- CU Honors Thesis Guidance

- Next: Managing Sources >>

- University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Research Guides

- Research Strategies

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 3:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.colorado.edu/strategies/litreview

- © Regents of the University of Colorado

- Franklin University |

- Help & Support |

- Locations & Maps |

- | Research Guides

To access Safari eBooks,

- Select not listed in the Select Your Institution drop down menu.

- Enter your Franklin email address and click Go

- click "Already a user? Click here" link

- Enter your Franklin email and the password you used to create your Safari account.

Continue Close

Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Framing the Literature Review

Literature Review Process

- Mistakes to Avoid & Additional Help

The structure of a literature review should include the following :

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories (e.g. works that support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely),

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

Development of the Literature Review

Four stages:.

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study and the research questions or hypotheses to follow.

- Places the problem into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provides the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

- Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored.

- Evaluation of resources -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic.

- Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review:

Sources and expectations. if your assignment is not very specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions:.

- Roughly how many sources should I include?

- What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should I evaluate the sources?

- Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find Models. When reviewing the current literature, examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have organized their literature reviews. Read not only for information, but also to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research review.

Narrow the topic. the narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources., consider whether your sources are current and applicable. s ome disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. this is very common in the sciences where research conducted only two years ago could be obsolete. however, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed because what is important is how perspectives have changed over the years or within a certain time period. try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. you can also use this method to consider what is consider by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not., follow the bread crumb trail. the bibliography or reference section of sources you read are excellent entry points for further exploration. you might find resourced listed in a bibliography that points you in the direction you wish to take your own research., ways to organize your literature review, chronologically: .

If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published or the time period they cover.

By Publication:

Order your sources chronologically by publication date, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

Conceptual Categories:

The literature review is organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it will still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The only difference here between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most.

Methodological:

A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Sections of Your Literature Review:

Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy.

Here are examples of other sections you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History : the chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : the criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

- Standards : the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence:

A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be Selective:

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use Quotes Sparingly:

Some short quotes are okay if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute your own summary and interpretation of the literature.

Summarize and Synthesize:

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep Your Own Voice:

While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice (the writer's) should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording.

Use Caution When Paraphrasing:

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Mistakes to Avoid & Additional Help >>

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 2:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.franklin.edu/LITREVIEW

- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

2. decide on the scope of your review., 3. select the databases you will use to conduct your searches., 4. conduct your searches and find the literature. keep track of your searches, 5. review the literature..

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window