7 Strategies for Teaching Students How to Annotate

- November 7, 2018

For many educators, annotation goes hand in hand with developing close reading skills. Annotation more fully engages students and increases reading comprehension strategies, helping students develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for literature.

However, it’s also one of the more difficult skills to teach. In order to think critically about a text, students need to learn how to actively engage with the text they’re reading. Annotation provides that immersive experience, and new digital reading technologies not only make annotation easier than ever, but also make it possible for any book, article, or text to be annotated.

1. Teach the Basics of Good Annotation

Help your students understand that annotation is simply the process of thoughtful reading and making notes as they study a text. Start with some basic forms of annotation:

- highlighting a phrase or sentence and including a comment

- circling a word that needs defining

- posing a question when something isn’t fully understood

- writing a short summary of a key section

Assure them that good annotating will help them concentrate and better understand what they read and better remember their thoughts and ideas when they revisit the text.

2. Model Effective Annotation

One of the most effective ways to teach annotation is to show students your own thought process when annotating a text. Display a sample text and think out loud as you make notes. Show students how you might underline key words or sentences and write comments or questions, and explain what you’re thinking as you go through the reading and annotation process.

Annotation Activity: Project a short, simple text and let students come up and write their own comments and discuss what they’ve written and why. This type of modeling and interaction helps students understand the thought process that critical reading requires.

3. Give Your Students a Reading Checklist

When first teaching students about annotation, you can help shape their critical analysis and active reading strategies by giving them specific things to look for while reading, like a checklist or annotation worksheet for a text. You might have them explain how headings and subheads connect with the text, or have them identify facts that add to their understanding.

4. Provide an Annotation Rubric

When you know what your annotation goals are for your students, it can be useful to develop a simple rubric that defines what high-quality and thoughtful annotation looks like. This provides guidance for your students and makes grading easier for you. You can modify your rubric as goals and students’ needs change over time.

5. Keep It Simple

Especially for younger or struggling readers, help your students develop self-confidence by keeping things simple. Ask them to circle a word they don’t know, look up that word in the dictionary, and write the definition in a comment. They can also write an opinion on a particular section, so there’s no right or wrong answer.

6. Teach Your Students How to Annotate a PDF

Or other digital texts. Most digital reading platforms include a number of tools that make annotation easy. These include highlighters, text comments, sticky notes, mark up tools for underlining, circling, or drawing boxes, and many more. If you don’t have a digital reading platform, you can also teach how to annotate a basic PDF text using simple annotation tools like highlights or comments.

7. Make It Fun!

The more creative you get with annotation, the more engaged your students will be. So have some fun with it!

- Make a scavenger hunt by listing specific components to identify

- Color code concepts and have students use multicolored highlighters

- Use stickers to represent and distinguish the five story elements: character, setting, plot, conflict, and theme

- Choose simple symbols to represent concepts, and let students draw those as illustrated annotations: a magnifying glass could represent clues in the text, a key an important idea, and a heart could indicate a favorite part

Annotation Activity: Create a dice game where students have to find concepts and annotate them based on the number they roll. For example, 1 = Circle and define a word you don’t know, 2 = Underline a main character, 3 = Highlight the setting, etc.

Teaching students how to annotate gives them an invaluable tool for actively engaging with a text. It helps them think more critically, it increases retention, and it instills confidence in their ability to analyze more complex texts.

More Resources articles

Can You Complete These 48 Summer Reading Challenges?

With all the exciting activities available during the summer, getting kids to read can be a struggle. But if you can find new ways to

Unveiling the Power of Research: Waterford.org Efficacy

Discover the transformative potential of research-backed approaches and their role in enhancing the learning experience for both students and educators. During this webinar, explore how

Professional Learning: Teaching the Science of Reading

Meet the dedicated Waterford.org Professional Learning team, committed to providing you with the essential strategies and support required to teach lessons guided by the science

National Poetry Month: Elementary Classroom Activities & Picture Books

MacKenzie Scott’s Yield Giving Awards Waterford.org a $10 Million Grant

The Art of Annotation: Teaching Readers To Process Texts

April 28, 2024

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to the interview with Andrea Castellano and Irene Yannascoli:

Sponsored by Listenwise and Studyo

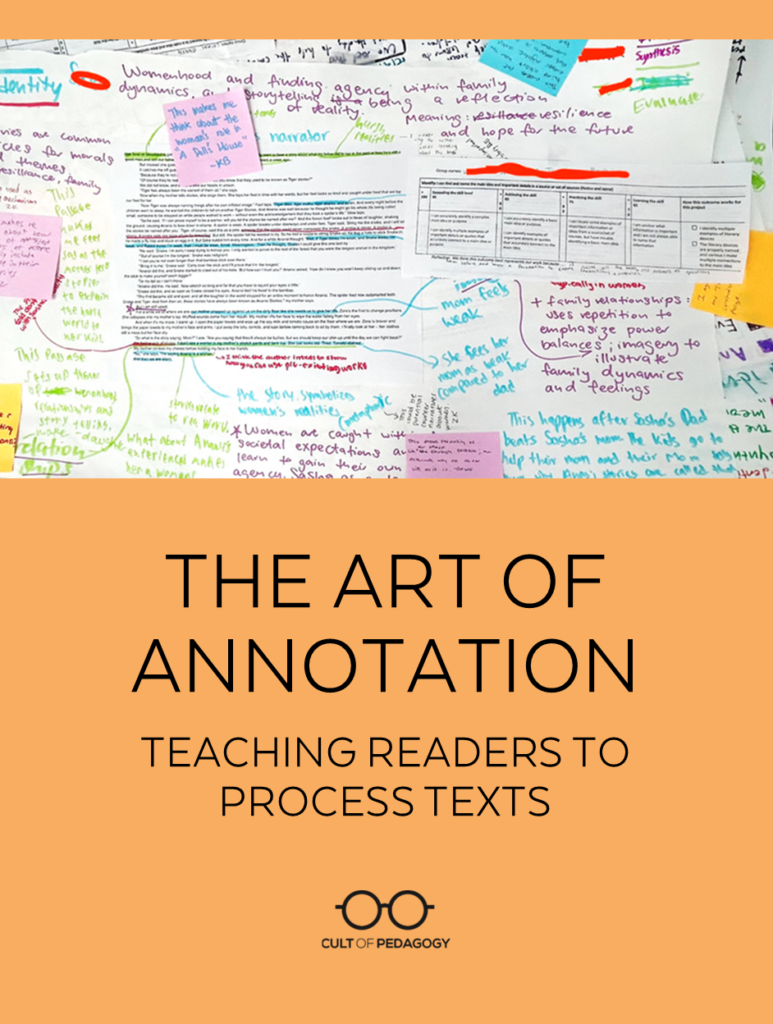

“Make your paper dirty.”

I get some funny looks when I say it at first, but it gets the point across. What I mean is I’m looking for annotations. I teach third grade, when young readers typically transition from developing readers to fluent ones, and it’s at this stage that they’re ready to begin to analyze texts on a deeper level. For that reason, this is the perfect time to introduce them to annotation.

Annotation — marking up and making notes on a text — can be an extremely effective tool for improving comprehension and increasing levels of criticality and engagement . By making these metacognitive markings, students are able to process a variety of texts in unique and meaningful ways. The thing is, it can vary in effectiveness, depending on which classroom you look into, if it’s being taught at all. You may have personally found that you aren’t getting the results you want from your approach.

After some trial and error, I have developed my own method for teaching annotation, which I’ll share here, along with the process my colleague Irene Yannascoli uses at the high school level. Whether you teach ELA or another content area, chances are your students read in your class. And if they read, there’s a chance they might need to annotate. Hopefully this post can offer some strategies to help your students establish annotation as part of their regular reading practice.

[ skip to high school process ]

Elementary Process

Prescriptive vs. responsive annotation.

One major hurdle students face is deciding what to annotate. Some students are hesitant to mark anything at all while others underline or highlight nearly every sentence in the text. Some teachers have attempted to remedy this by taking a prescriptive approach to annotation. They direct students to locate specific details and what to do when they’ve found them, saying things like, “find and underline the sentence that proves the character is sad,” or “box two words you don’t know in paragraph 2.” It’s like a scavenger hunt: Find three things, answer three questions.

I’ve used this approach in the past, and it certainly is a great way to get students to notice and name things, but what I kept noticing is that whenever I stopped prompting students to make their annotations, they stopped making them. They were so dependent on my guidance that they never took ownership of the process.

Eventually I realized I needed to teach my students to develop their own systems for annotating. The responsive approach I’m advocating here centers the reader on the basis that we all bring our own perspectives, experiences, and ideas to the text. As much as our interpretations are varied and nuanced, so are our annotations. Teaching students to navigate text as active readers helps them make sense of what they read. Artful annotation is what happens when they’re inspired to respond in their own unique way.

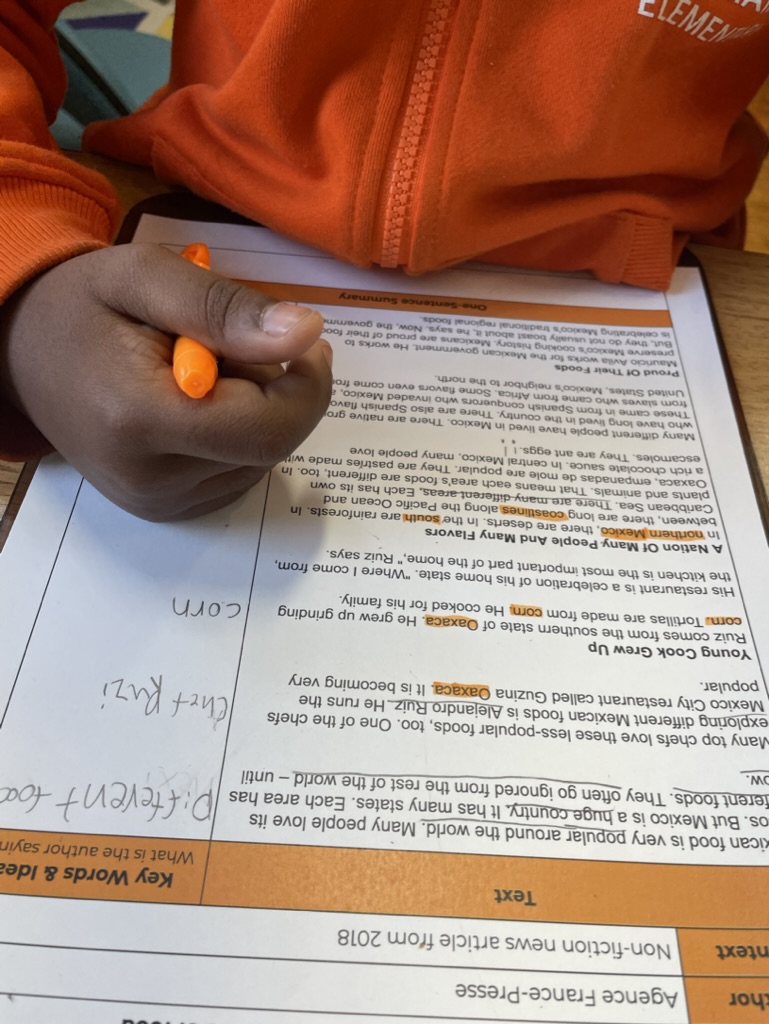

Getting Started

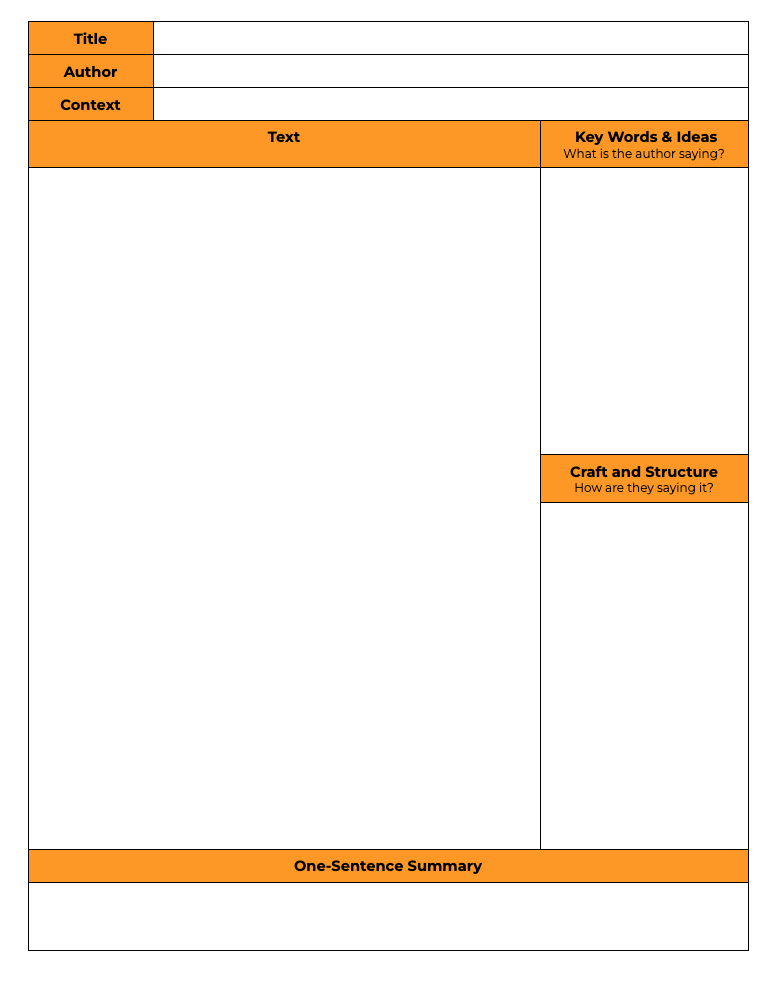

One thing teaching has taught me is that straightforward visuals reduce cognitive load and allow students to concentrate on what’s important. To simplify annotation for my students, I designed a template (below) with space on the left for me to paste the text and cells on the right and bottom for note-taking.

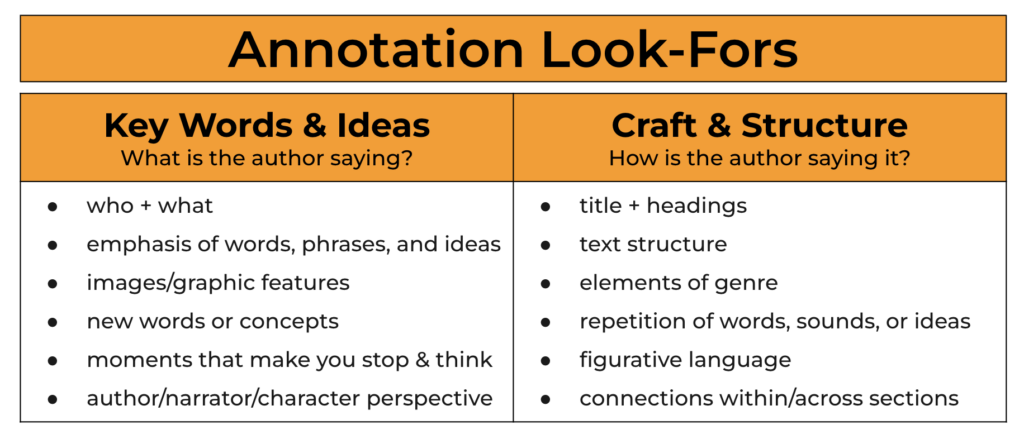

At the point in the year that we start this process, I’ve already taught all the literacy concepts they’ll need for this activity, such as theme, figurative language, text structures, and more. What this template does is sort each concept into one of two lenses: key words & ideas, and craft & structure. We then comb through the text with these two in mind, asking and answering over and over, What is the author saying? and How are they saying it? To remind them of what to look for, I provide the following graphic on the template. This is a list of look-fors that encompass most of what they’ll encounter as they read.

Modeling Responsive Annotation

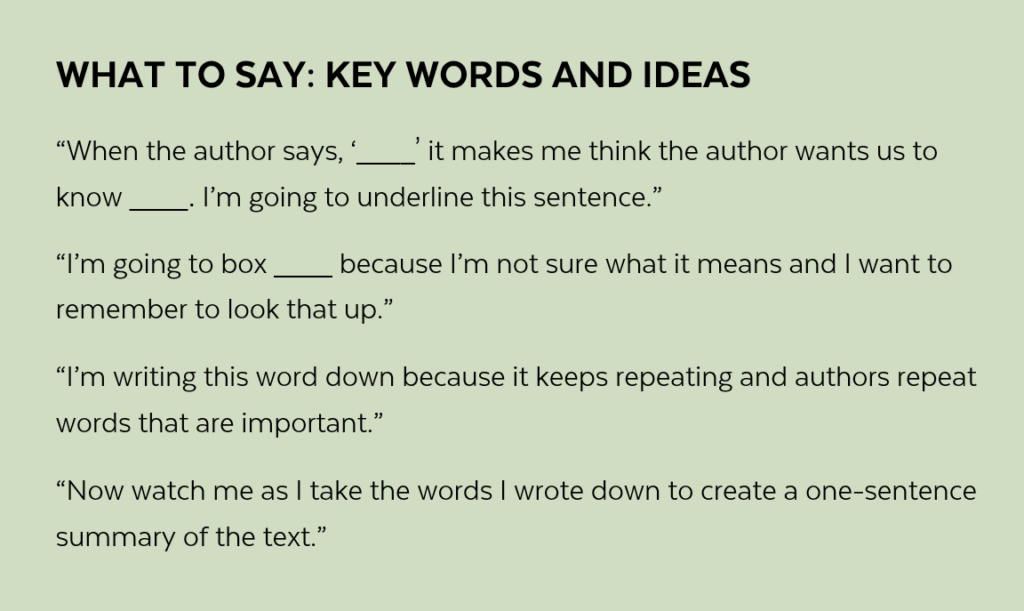

To introduce responsive annotation, I use a direct approach to make my thinking as transparent as possible. In addition to modeling the use of metacognitive markers, I talk through each step of the process. Here’s a sample breakdown of what that would look like in the early stages.

Introducing Each Lens

- Choose the lens through which you will be approaching the text. In the introductory stage, it is recommended to read the same text twice — one session for key words and ideas, another for craft and structure. Provide the annotation look-fors as an anchor chart or include it on the template itself.

- Give students a copy of the text and display your copy of the text for all to see. As students watch, read a section of text aloud, stopping to underline, box, and make notations.

- Think aloud as you annotate. Read, stop, jot, explain. You are responding to the text as you encounter each element rather than searching the text for specific items. Students should either be watching or copying the teacher’s moves at this stage.

Guided Annotation (Whole Class)

To help students learn to prioritize information, the teacher will pose questions that reinforce the points made in the explicit model. This will happen in lockstep as a whole class — independent practice comes later. This stage works best directly following the teacher model so students get to immediately put things into practice.

- Guide students through the next section of the text, first by reading it together and then by asking open-ended questions related to the chosen lens. For example: For Key Words and Ideas: What is the author saying here? What words seem important? What part made you stop and think? For Craft and Structure: How does the author show you what the character is feeling in paragraph 5? Who can find and annotate a connection between paragraph 3 and paragraph 4? What does the author mean by _____?

- Students take a turn with another section of the text. Prompt students to share their thinking and show what they did. This is a great opportunity to validate or course-correct as needed.

Guided Annotation (Individual)

- When they’re ready for the next stage, provide each student with a new text. Give several minutes to read and annotate, one section at a time. Circulate the room, monitoring and offering feedback. As students make their way through each section, give the green light to move on.

Giving feedback in real time adds encouragement and reinforces desired reading behaviors. This type of gradual release model works best when the teacher is responsive to the needs of the class, moving on only when they’re ready.

- Once they have the hang of it, students continue to read and annotate on their own. Those who need support can now be pulled into a small group. This is also a good time to implement partner annotation for students who may not be ready to read the text independently.

Continue to use the template to support students as they annotate for either key words and ideas or craft and structure. It can be modified to merge the lenses once they can do both with confidence . After several guided annotation lessons, students should be ready to annotate on their own without needing the scaffolding of this stage every time.

Discussion and Feedback

Now that students have a sense of what to look for when they read, what they need at this juncture is a chance to see what other readers are doing and compare it to their own work. This not only deepens their understanding of the text through discussion, it strengthens their grasp on what they should be noticing.

- Gather the class and project student work (in my class, students volunteer to share). Prompt students to compare annotations, note their peers’ insights, and offer feedback.

- Allow students to “borrow” snippets of each others’ annotations if they wish . This is intentionally a collaborative process that promotes the sharing of insights and ideas.

- Students can use the template as long as it’s needed. The cycle of discussion and feedback can continue indefinitely. At any point, the annotation look-fors can be edited for specific genres, content areas, or other purposes for reading.

Click here to make a copy of the elementary process for your Google Drive .

High School Process: Collaborative Annotation

Whether at the secondary or elementary level ( click here to jump up to elementary), the art of annotation is in making it meaningful. Responsive annotation does just this. Because students often believe there’s a “right answer” when annotating, asking them what they notice trains them to use their own funds of knowledge as they read. Like my approach to teaching annotation in elementary, Irene Yannascoli gives her 10th graders the freedom to interact with texts on their own terms, deciding for themselves what is meaningful enough to annotate. She also wants them to use peer insight to practice concepts already reviewed in class, so she makes this annotation process collaborative.

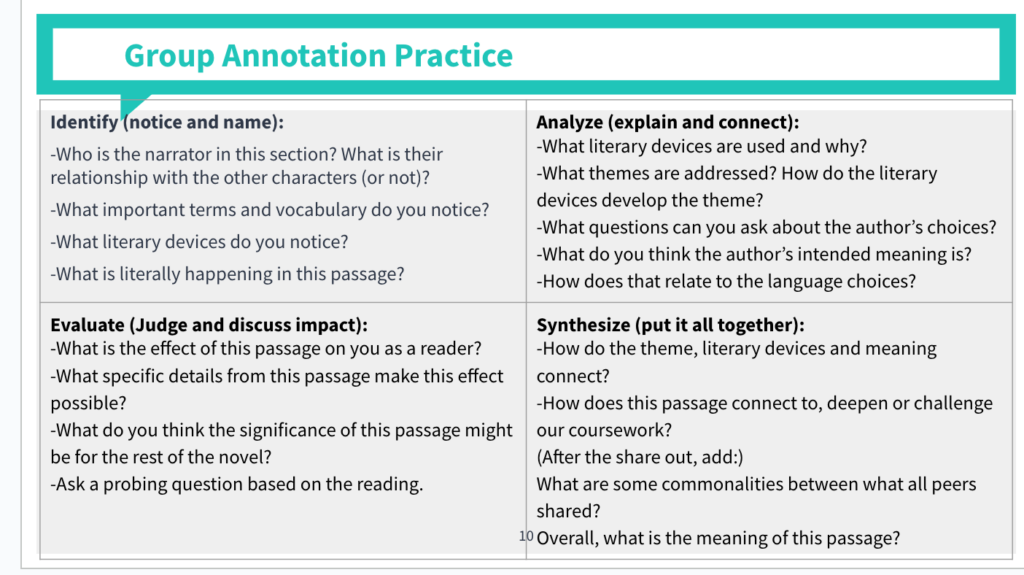

Similar to the elementary approach in the previous section, this process has students consider the text through a given lens; in this case, four core concepts that have already been taught in class: identify (notice and name), analyze (explain and connect), evaluate (judge and discuss impact), and synthesize (put it all together). The purpose of the group annotation is to practice these skills collaboratively.

In order to set this up:

- Choose 4 teaching points from your recent curriculum that you would like students to discuss and practice

- Choose a passage that reflects the 4 teaching points.

- For each of the teaching points, create guiding questions for students to reference while they annotate. It’s not necessary for students to answer all of these guiding questions, and as they get used to the protocol they may use them less and less.

Irene’s guiding questions are pictured below.

Note that these concepts and questions are specific to language arts study; they can be modified according to any subject or genre.

Independent Annotation

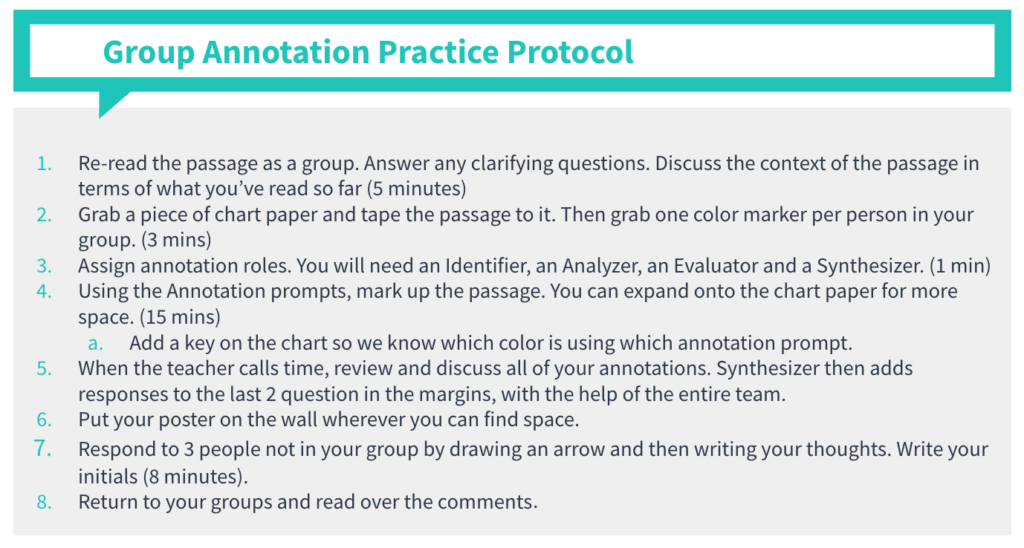

- Start by reviewing the “Group Annotation Practice Protocol” slide (below) with the class.

- Conduct a read-aloud of the passage . Ask students if they have any questions before they begin. To assess understanding, you may ask them to identify key terms in the passage or answer questions related to the who, what, when, where and why of the passage

- Students re-read the passage independently and jot down their first thoughts.

This is a preliminary step before they annotate to capture a first impression of the passage, and makes space for any clarifying questions that might arise .

Group Annotation

After students have reread the text on their own, it is time to begin their annotations.

- Students get in groups and each person claims a focus skill: Identify, Analyze, Evaluate or Synthesize. Now, each group member is following one of the 4 sets of guiding questions using the same passage.

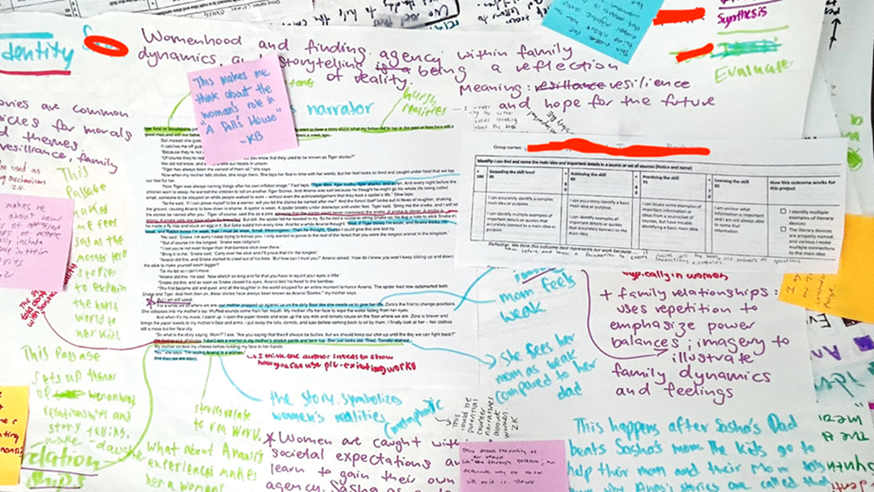

- After taping a copy of the text to chart paper, each student grabs a marker and for 15 minutes, uses the guiding questions to “make their posters dirty.” Each student should be huddled around their chart paper, underlining, drawing arrows, and making notes next to the passage.

- Circulate and observe each group , helping students deepen their thinking by asking questions and making connections between the annotations .

- Students wrap up and review their annotations. Each person shares their thoughts and epiphanies from the annotation process.

- While the group shares out, the “Synthesizers” answer their last two questions about the commonalities between peers and overall meaning of the passage. They write this on their posters.

- Students then post their chart paper on the wall and conduct a gallery walk , during which they examine peer charts and make notes on post-its expanding, deepening or challenging the original annotations based on their own reading of the text. Some sentence starters to move students beyond agree/disagree: This makes me think about… I can connect this to… Additionally, this could mean… I wonder why…

- Students return to their original posters and read what other group members commented . They now have an opportunity to add any final notes, ideas or understandings. If time allows, conduct a whole group share-out: What was something that surprised you, inspired you, or made you rethink?

At this point, it’s up to you how to assess students for this activity. You might just treat it as a practice for building independent annotation skills and assess students individually on their own annotations on a future passage. You might choose to develop a rubric for this activity and give all group members a score on their poster. Or you might have students write a reflection about their strengths and weaknesses in the process and set goals for the future.

Click here to make a copy of the high school process for your Google Drive.

[ back to elementary process ]

A Few Caveats

Although I explicitly model responsive annotation, I don’t expect my students to copy my exact style. Yes, I do tell them to mark up the text as well as make notes in the margins, but I want my students to use metacognitive markers in ways that make sense to them. Some like to underline sentences, others highlight. I circle vocabulary words, others box them. Some enjoy creating their own symbols and methods of organizing their notes in the margins. Recently I’ve noticed a few students creating systems for highlighting in different colors complete with a key.

It must also be said that not every student needs to or should annotate when they read. Some process text better internally and find the annotation system slows them down or distracts them; others can’t handle the multitasking element and just need to focus on reading. The supports provided for accessing the text are just a temporary scaffold anyway. As long as they can demonstrate that they understand what they’re reading in other ways, (e.g., through discussion or answering questions) I really don’t insist that they do it. But for the majority of students who find themselves glossing over key moments or struggling with comprehension, this process is extremely useful. Ultimately, the decision depends on you knowing your students and what works for them as learners.

So, Is This Really Worth It?

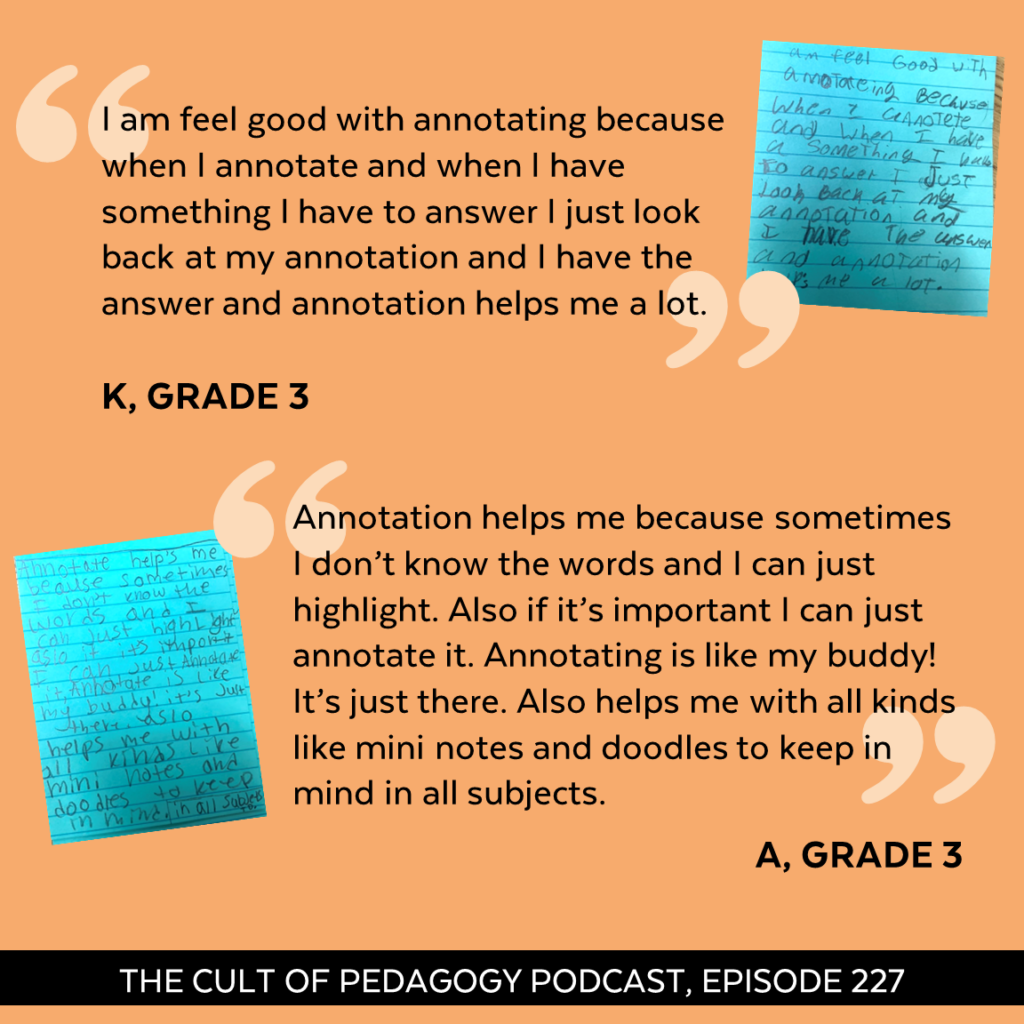

Since we’ve been teaching annotation this way, Irene and I have both observed a correlation between the quality of annotations on the page and the ability to comprehend text. Incorporating the look-fors into the annotation practice reinforces the concepts skills taught across the year. And the confidence our students have in themselves as readers has also grown. My students say things like, “Annotation has helped me become a better reader“ and “Annotation helps me understand the text or the things I’m reading a bit more.”

This process is about more than preparing students for standardized tests or giving them a strategy to boost their grades. Our students will be reading and comprehending texts for a very long time — hopefully, for the rest of their lives. While they won’t always grab a pen when they sit down with a book, there will be many times they can put these skills to work. If the goal is to process what they’re reading, annotation provides them with one way to do so.

Annotating, or “making your paper dirty” as we like to call it, is definitely an acquired skill. It takes time to learn, but more than likely, it’s worth the effort.

Duke, Nell & Pearson, P.. (2002). Effective Practices for Developing Reading Comprehension. What research has to say about reading instruction. 3. 10.1598/0872071774.10.

Landmark College. (n.d.-a). Active reading (see also critical reading) . Active Reading | Landmark College. https://www.landmark.edu/academics/writing-matters/wac-glossary/wac-active-reading

Lloyd, Z.T., Kim, D., Cox, J.T., Doepker, G.M. and Downey, S.E. (2022), “Using the annotating strategy to improve students’ academic achievement in social studies,” Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning , Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 218-231.

Come back for more. Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half , the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

What to Read Next

Categories: Instruction , Podcast

Tags: content area literacy , English language arts , literacy , teaching strategies

This was a great read/listen. I have always taught annotation by talking with students about what they think is important to remember using titles, subtitles and headlines as a clue. However, this approach seems a better way to get kids to think more deeply about what they’re reading. Thank you for sharing these resources.

Glad you found it helpful, Elisa!

We’ve spent years building http://nb.mit.edu/ , a free-for-anyone *social annotation* site that lets students have discussions in the margins of any online course materials. It’s been used in thousands of classes and study groups at over 100 universities. Feel free to try it out.

Thanks for sharing this resource, Dr. Karger!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

- Our Mission

Teaching the Long-Term Value of Annotation

To help high school students learn how to annotate, first show them why it’s a useful tool that will serve them now and in the future.

Annotation can be a difficult and stressful process for high school students and educators alike. It’s an essential skill across subject areas, something we expect students to just do, but rarely do we actually teach them how. Students don’t understand how to annotate and, more often than not, why it would be a useful tool in the first place.

“If I understand the story, why should I annotate?” was a common refrain I heard from students. I noticed that many would highlight random sentences hoping to skate by in assessment. Others wouldn’t even attempt to engage in the process. I began to consider ways that I could support students in developing close reading and annotation in a collaborative and genuine way that would give them agency.

The first step required that I think about why I saw annotation as valuable in the first place. Why did I see it as a skill that students needed in my classroom ? I created three primary beliefs to work from:

- Annotation is intentional, allowing us to engage more deeply with texts and ourselves.

- Annotation is practical in all areas of life and with all types of texts.

- Annotation offers agency and is a tool that we can use to interact with texts from where we are now.

With these beliefs in mind, I worked to create a scaffolded process that provided structure and guidance in annotation while also facilitating choice.

Step 1: Create purpose

Establish clear prompts to engage students. The teacher or the students can preselect these prompts, but the guided focus can be the first step to making meaningful observations. The more specific the prompts, the better.

For example, when studying world building, I have students look for physical descriptions, sociopolitical elements, and paranormal or supernatural elements. Assigning each prompt a specific color helps students to stay organized and easily pick out elements of focus later on.

Step 2: Identify

After students have read the text, I ask them to go back and identify the quotes or highlights that they see as the most interesting and/or important. I often have them circle, star, or otherwise mark these in some way. I also ask students to leave a note that explains their selection and the importance of this quote.

The goal in this step is to have students revisit the text and their initial noticings, making a habit of using their notes. This step also allows students to self-select what they see as important and defend their selection, providing ample opportunities for discussion and comparison.

Step 3: Make meaning

You can tailor the next step to the key elements of any lesson or specific text. Students use sticky notes to add on final thoughts, questions, or connections they may have in relation to the text. As with the previous steps, these can be adapted to the goals of the lesson or the needs of students.

For example, you may ask students in this step to speak directly to possible themes or a specific character. Again, this step builds the habit of going back and rereading and reviewing texts. It also aims to have students use their annotations to begin to synthesize, looking to explain larger abstract and complex topics such as theme or historical context.

Step 4: Share meaning

The final step requires collaborative discussion among students. When they follow the previous steps, every student has the ability to come to the discussion with quotes, ideas, and resources that will allow them to participate.

I often begin discussion with the prompts created in step one, allowing students to draw from textual evidence and meaning making from steps two and three. During or after the discussion, I have students again add to their notes and annotations, helping them see knowledge building as collaborative.

When guided through this structured process several times, students become familiar with the process and embody the steps. They come to understand the need to annotate with purpose, to revisit the text, and to use the text in a discussion. The ultimate goal is for the instructor to slowly relinquish support until students are doing the process independently. Requiring students to identify prompts, asking them to independently revisit the text and add notes, or having them lead the discussion can achieve this goal.

Ensuring that students have opportunities for skill development and practice enables them to utilize these skills not only in the ELA classroom and across the curriculum, but also throughout their lives.

Annotating Texts

What is annotation.

Annotation can be:

- A systematic summary of the text that you create within the document

- A key tool for close reading that helps you uncover patterns, notice important words, and identify main points

- An active learning strategy that improves comprehension and retention of information

Why annotate?

- Isolate and organize important material

- Identify key concepts

- Monitor your learning as you read

- Make exam prep effective and streamlined

- Can be more efficient than creating a separate set of reading notes

How do you annotate?

Summarize key points in your own words .

- Use headers and words in bold to guide you

- Look for main ideas, arguments, and points of evidence

- Notice how the text organizes itself. Chronological order? Idea trees? Etc.

Circle key concepts and phrases

- What words would it be helpful to look-up at the end?

- What terms show up in lecture? When are different words used for similar concepts? Why?

Write brief comments and questions in the margins

- Be as specific or broad as you would like—use these questions to activate your thinking about the content

- See our handout on reading comprehension tips for some examples

Use abbreviations and symbols

- Try ? when you have a question or something you need to explore further

- Try ! When something is interesting, a connection, or otherwise worthy of note

- Try * For anything that you might use as an example or evidence when you use this information.

- Ask yourself what other system of symbols would make sense to you.

Highlight/underline

- Highlight or underline, but mindfully. Check out our resource on strategic highlighting for tips on when and how to highlight.

Use comment and highlight features built into pdfs, online/digital textbooks, or other apps and browser add-ons

- Are you using a pdf? Explore its highlight, edit, and comment functions to support your annotations

- Some browsers have add-ons or extensions that allow you to annotate web pages or web-based documents

- Does your digital or online textbook come with an annotation feature?

- Can your digital text be imported into a note-taking tool like OneNote, EverNote, or Google Keep? If so, you might be able to annotate texts in those apps

What are the most important takeaways?

- Annotation is about increasing your engagement with a text

- Increased engagement, where you think about and process the material then expand on your learning, is how you achieve mastery in a subject

- As you annotate a text, ask yourself: how would I explain this to a friend?

- Put things in your own words and draw connections to what you know and wonder

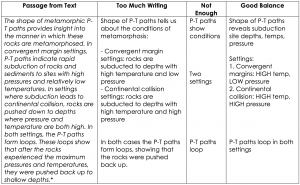

The table below demonstrates this process using a geography textbook excerpt (Press 2004):

A common concern about annotating texts: It takes time!

Yes, it can, but that time isn’t lost—it’s invested.

Spending the time to annotate on the front end does two important things:

- It saves you time later when you’re studying. Your annotated notes will help speed up exam prep, because you can review critical concepts quickly and efficiently.

- It increases the likelihood that you will retain the information after the course is completed. This is especially important when you are supplying the building blocks of your mind and future career.

One last tip: Try separating the reading and annotating processes! Quickly read through a section of the text first, then go back and annotate.

Works consulted:

Nist, S., & Holschuh, J. (2000). Active learning: strategies for college success. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 202-218.

Simpson, M., & Nist, S. (1990). Textbook annotation: An effective and efficient study strategy for college students. Journal of Reading, 34: 122-129.

Press, F. (2004). Understanding earth (4th ed). New York: W.H. Freeman. 208-210.

Make a Gift

- Skip to main content

Join All-Access Reading…Doors Are Open! Click Here

- All-Access Login

- Freebie Library

- Search this website

Teaching with Jennifer Findley

Upper Elementary Teaching Blog

Annotating Tips for Close Reading

Have you seen that popular meme where the student highlights two entire pages of a text? It cracks me up every time I see it. One reason that meme resonates with teachers is because it is a very real struggle. Each year, it seems I have some students who annotate like crazy. Or the opposite and the students don’t pick up a pencil or annotating tool the entire time they are reading. Thankfully, just as our students grow and learn in other areas, they can learn to be effective at annotating texts. This post will share specific annotating tips to use during close reading. Using these annotating tips will help your students make sense of a text, analyze a text, and reflect on the text (verbally and in writing).

Note: The hand2mind close reading small group kit links are affiliate links (which means that if you or your school makes a purchase through the links, I earn a small commission at no extra cost to you).

General Annotating Vs. Specific Annotating

Before diving into the tips, let’s back up a little and discuss the two main types of annotating that my students do as they are reading.

General Annotating – This is the most common type of annotating that you see shared on blogs, articles, and Pinterest. This type of annotating is when the student reads the text with the purpose of simply understanding the gist of the topic or story. The students use general annotating symbols and directions that work with any text (making predictions, making connections, interesting facts, etc). This type of annotating works really well when the students are reading a text one time for a single purpose or during the initial read of a text.

Specific Annotating –When students complete this type of annotating, they have a specific purpose in mind and are looking for textual details, facts, and evidence that align with that purpose. As you can probably already tell, this type of annotating lends itself to close reading because each read of the text has a new purpose. It makes no sense to have the students use the same general annotation symbols and directions each time they read. Specific annotating also works well for literature circle discussions and literary analysis.

Some of the annotating tips I share will work well with both types of annotating and some work better for supporting students during specific annotating.

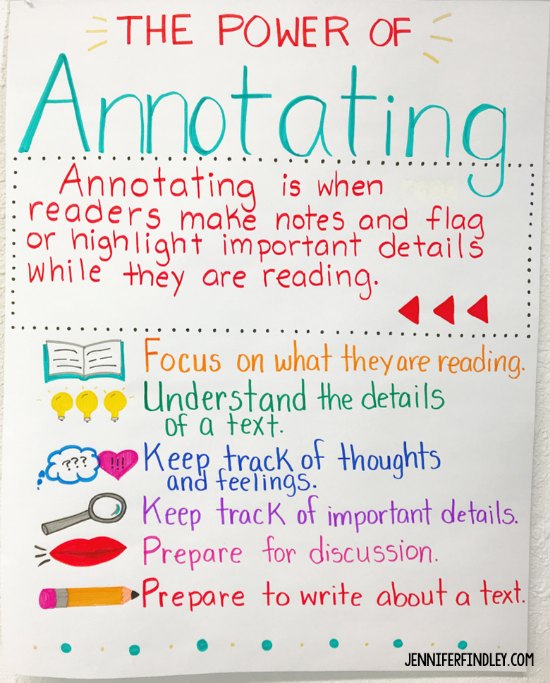

Teach Students the Purpose of Annotating

Before I even begin modeling and having my students practice annotating texts, we spend time discussing the purpose and benefits (or power) of annotating. We discuss what annotating is, how it looks, the tools that can be used, and how it helps the reader.

We discuss how annotating helps readers:

- focus on what they are reading

- understand details of a text, including complex or difficult to understand details

- keep track of their thoughts and feelings about a texts and its details

- keep track of important details

- prepare for discussion

- prepare to write about a text

Click here or on the image below to grab a free printable that I use when introducing annotating.

Annotate Each Close Read with a Specific Purpose

Remember how we talked about the difference between general and specific annotating above? One of my best tips for annotating with close reading is to have the students annotate each read with a specific focus in mind. While they are reading, they should annotate specifically for details and textual evidence that will support their discussion or response to the focus prompt for that read.

For example, if the students are reading a text to zone in on how the author uses the character to develop the theme, the students should be annotating character details such as dialogue, action, and internal monologue that support the theme. Then, they will be able to use those annotations to respond to and discuss the focus.

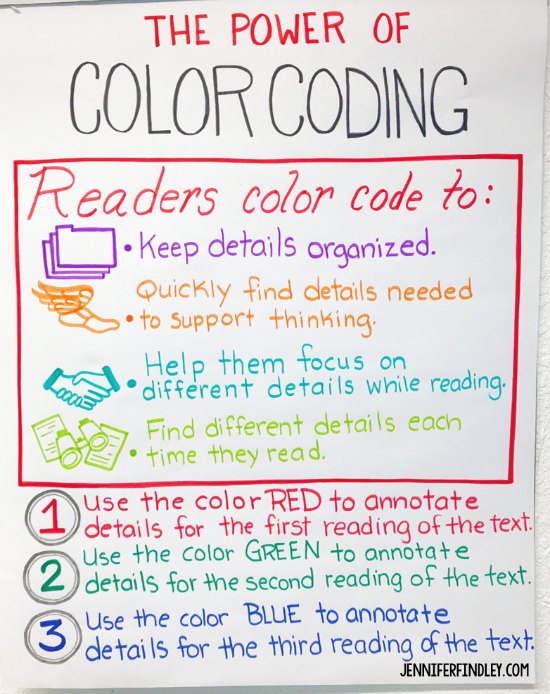

Color Code Each Annotation

Have the students use a different color for each read. This will help them organize their annotations and help with accountability. Students will be able to refer back to specific annotations to discuss and reflect on a text.

Click here to grab the printable that I use to introduce the benefits and purposes of color coding to my students (on page 3).

Model the Annotation Process

The first few times you do close reading strategies with your students, make sure you model how to appropriately annotate a text. To do this, I recommend using a common text either projected on a whiteboard, blown up in a poster size, or use a text specifically created for modeling.

Here are the steps I follow when preparing to model how to annotate:

- Prepare my materials – The materials I use are an engaging text broken up into paragraphs (two copies-one to use prior to the lesson one to use during the lesson), a focus prompt or question, and an annotating tool (this can be as simple as a pencil)

- Preread the text – Read the text prior to instruction and annotate it with the focus prompt in mind. Doing this beforehand will allow you to ensure the focus prompt/question is a good fit for the text and that you have a variety of details to annotate.

And here is what I do to actually model the annotation process with my students:

- Introduce the text and focus prompt/question to the students. I explain that I will be reading this text with a specific focus in mind. While I am reading the text, I will annotate details that will show my understanding of the text and the focus prompt/question. I also explain that the annotations I choose will help me discuss the prompt/question.

- Stop and Annotate – When I get to an obvious detail, I will pause my reading and explain to the students that I am annotating this detail and why.

- Stop, Reflect, and Then Annotate – I also model how to stop, reflect, and annotate after reading a section of text. To do this, I read a paragraph and then stop and think aloud about what details I can annotate that match my focus question. I invite the students to help me find details as well.

- When I am done reading and annotating the text, I will show the students how to use the annotations to discuss the focus prompt or questions. I do this simply by referring to the annotations (by pointing and using the same words) as I discuss the text.

Model How to Use Annotations

In addition to modeling how to annotate a text with specific purposes, make sure you explicitly model how to use the annotations to support written and verbal discussion of the text. This will help your students see the purpose behind annotating and help them find greater success with this important strategy.

After modeling how to annotate a text (using the steps outlined in the above section), I follow up with a lesson on how to use those annotations to discuss and write about the text. I model how to discuss the text using the annotations the same day that I model how to annotate. Then, we come back together the next day and I explicitly model how to use those annotations in writing.

I know this may sound challenging but it is super easy. All you do is review your annotations, restate the focus prompt, answer the prompt, and then provide details from the text (your annotations) to support your answer. As I do this, I actually point to the details that I annotated to show the students the connection between what I annotated and my response to the text.

Annotating can be a very powerful tool for readers for many reasons. I hope these tips help you and your students. Do you have any annotating tips that work well for your readers? Let us know in the comments!

Need Close Reading Resources?

Shop This Post

3rd Grade Close Reading

4th Grade Close Reading

5th Grade Close Reading

Share the knowledge, reader interactions.

September 1, 2023 at 11:28 am

Im trying to buy this. I don’t see anything where I can buy this.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

TEACHING READING JUST GOT EASIER WITH ALL-ACCESS

Join All-Access Reading to get immediate access to the reading resources you need to:

- teach your reading skills

- support and grow your readers

- engage your students

- prepare them for testing

- and so much more!

You may also love these freebies!

Math Posters

Reading Posters

Morphology Posters

Grammar Posters

Welcome Friends!

I’m Jennifer Findley: a teacher, mother, and avid reader. I believe that with the right resources, mindset, and strategies, all students can achieve at high levels and learn to love learning. My goal is to provide resources and strategies to inspire you and help make this belief a reality for your students.

Back to School With Annotation: 10 Ways to Annotate With Students

By jeremydean | 25 August, 2015

It’s back-to-school season and I find myself once again encouraging teachers to discuss course readings with their students using collaborative web annotation technologies like Hypothesis. Though relatively new to Hypothesis, I’ve been making this pitch for a few years now, but in conversations with educators of late I’ve come to realize that we often mean different things by the word “annotate.” Annotation connotes something distinct in specific subject areas, at different grade and skill levels, and within certain teaching philosophies. This will be the first semester during which Hypothesis has an active education department and so in the spirit these first days of the school year, I thought it might be worth exploring what we really mean when we say, “annotate.”

Annotation is typically perceived as a means to an end. As marginal note-taking it often is the basis for questions asked in class discussion or points made in a final paper. But annotation can also be a kind of end in itself, or at least more than a rest-stop on the way to intellectual discovery. This becomes especially true when annotation is brought into the relatively public and collaborative space of social reading online. Digital marginalia as such requires a redefinition or at least expanded understanding of what is traditionally meant by the act of “annotation.”

Billy Collins’ poem “Marginalia” outlines various ways that people have annotated throughout history, including in formal education contexts. But even within pre-digital student marginalia there can be a wide range of types of annotation from defining terms and explaining allusions to analytic commentary to more creative responses to the text at hand. As annotation becomes social and media-rich as it does using Hypothesis and other web annotation technologies, these species of marginalia only further proliferate.

For those curious about integrating annotation exercises into an assignment or a course, below I outline ten practical ways that one might annotate with a class. This list is by no means exhaustive–the larger point is that there are a lot of different ways for students and teachers to annotate. I’d love to hear about your experiences with annotation in the classroom in notes and comments here or even in your own blog posts on Hypothesis. My hope is that over the course of the coming semesters, Hypothesis will develop as a community of educators sharing their ideas, assignments, successes, and failures. As always, feel free to contact me at [email protected] to chat further about collaborative annotation! (For a more technical guide to using Hypothesis, see our tutorials on getting started here.)

1. Teacher Annotations

Pre-populate a text with questions for students to reply to in annotations or notes elucidating important points as they read.

One of the amazing aspects of social reading is that you can be inside the text with your students while they are reading, facilitating their comprehension, inspiring their analysis, and observing their confusion and insight. It’s about as close as you can get to the intimacy of in-class interaction online. You can guide students through the reading with your annotations, offering context and possible interpretations. This allows you to be the Norton editor of your course readings, but attentive to the particular themes of your course or local contexts of your classroom community. Or you can provoke student responses to the text through annotating with questions to be answered in replies to your annotations. Looking at responses to a question posed in the margin of a text is a great starting point for class discussion in a blended course. In the classroom, students can be prompted to expand on points begun as annotations to jumpstart the conversation. And when there is no physical classroom space, as in online courses, annotation can be a means for the instructor to have a similar guiding presence and to create an engaging and engaged community of readers.

The real pedagogical innovation of collaborative annotation, however, is that students are empowered as knowledge producers in their own right, so most of my suggested classroom annotation practices revolve around a variety of student-centered annotation activities in which they are the ones posing the questions and teachers are co-learners in the reading process. There are also other use cases, however, for teacher annotation, such as using web annotation to comment on student writing published online.

2. Annotation as Gloss

Have students look up difficult words or unknown allusions in a text and share their research as annotations.

Practical across a wide range of skill levels, this exercise can span from simply creating a list of vocabulary words from a text for study to presenting, as a class or individually, a text annotated like a scholarly volume. We’ve seen this kind of exercise completed on great works of literature as well as scientific research papers. Think of the activity as creating a kind of inline Wikipedia on top of your course reading. For difficult texts, sharing the burden of the research necessary for comprehension can help students better understand their reading. And there is something incredibly powerful about students beginning to imagine themselves as scholars, responsible for guiding a real audience through a text, whether their own peers or a broader intellectual community. Students can be encouraged to practice skills like rephrasing research material appropriately and citing sources using different formatting styles. And, of course, glossing can be combined with more insightful annotation as well.

Protip: If you plan to annotate across multiple texts with a class, have students use a course tag (like “Eng101DrDeanFall15”) in all of their annotations. Tagging in this way allows both teacher and students to follow the group’s work on a class stream of activity. Here’s an example of what such a class tag stream looks like from one of our most active educators, Greg McVerry. More on the pedagogy of tags in this tutorial. Note: very soon (in a matter of weeks) we will be launching a private group feature that will streamline this workflow–annotations will be publishable to a specific group and that group will have a stream that can be followed.

3. Annotation as Question

Have students highlight, tag, and annotate words or passages that are confusing to them in their readings.

An annotation need not be, and often is not, an answer. A simple question mark in the margin of a book can flag a word or passage for discussion. And such discussions can be generative of important explication and analysis. Directing students to annotate in this way creates a sort of heat map for the instructor that can be used to zero in on troubling sections and subjects or spark class discussion. Tags categorizing the particular problem could be used as a simple way to prompt clarification (vocab, plts, research methods, etc.).

While the teacher can respond to such student annotations, a possible follow up exercise could have students respond to each other’s questions instead.

4. Annotation as Close Reading

Have students identify formal textual elements and broader social and historical contexts at work in specific passages.

Online annotation powerfully enacts the careful selection of text for in-depth analysis that is the hallmark of much high school and college English and language arts curriculum. Using web annotation, students are required to literally select small pieces of meaningful evidence from a document for specific analysis. Teachers can direct students to identify textual features (word choice, repetition, imagery, metaphor, etc.) or relevant broader contexts (historical, biographical, cultural, etc.) for passages of a text, and then prompt them to develop a short argument based on such evidence. Collaborative close reading can be especially effective in that multiple students can build off each other’s interpretations to demonstrate how deep textual analysis can go. Teachers implementing the Common Core State Standards for reading might pay special attention to this use case for annotation in the classroom.

Some teachers will use web annotation as a tool throughout the semester for this purpose. Students thus gain regular practice in close reading and build ideas towards more substantive, summative assignments. Such assignments can also begin as collaborative exercises done by the entire class and culminate with individual or small group annotation projects.

5. Annotation as Rhetorical Analysis

Have students mark and explain the use of rhetorical strategies in online articles or essays.

Whether analyzed as a class or individually, a clearly argumentative piece should be chosen for this assignment, perhaps from an op-ed page in a newspaper or magazine. Students might be asked first to simply identify rhetorical strategies (like ethos , pathos , and logos ) using the tag feature in annotations created with Hypothesis. On a second pass, they can be asked to elaborate on how and why a certain strategy is being used by the author. Identification of rhetorical fallacies could be built into this or a related assignment as well. Note: in order to make such an exercise more streamlined, we plan in the near to future allow users to pre-populate a set of controlled terms with which a group can tag their annotations.

Combined with exercises six and nine, annotation as rhetorical analysis could be part of a composition course that also has students map arguments in a controversy using annotation and then begin their own advocacy through annotation of primary sources mapped and analyzed. (This is how the rhetoric department at UT-Austin, where I taught while getting my PhD., structures their freshman composition courses.) A twist on this assignment could ask students to analyze their own persuasive prose in this way–discussion of such self-reflexive annotation on one’s own writing is a whole other category of annotation, probably deserving of a blog post in itself.

6. Annotation as Opinion

Have students share their personal opinions on a controversial topic as discussed by an article.

A lot of how people are interacting with content online today—commenting on web articles, Tweeting about them with brief notes–is a kind of annotation. At Hypothesis we might think of web annotation as a more rigorous form of such engagement with language and ideas on the Internet. Framing one’s opinions as annotations of specific statements or facts is a reminder that our arguments should be grounded in actual evidence. In any case, allowing students to express their opinions in the margins of the Web, and helping them become responsible and thoughtful in those expressions, is a huge part of what it means to be literate both on the Web and in democratic society more generally. Students could be asked simply to respond to the reading with their thoughts, as in a dialectical reading journal, or employ specific cultural or persuasive strategies in their rhetorical intervention.

Again, this advocacy exercise could be a summative assignment within a unit that uses Hypothesis to complete annotation activities like those described in ways five and nine here.

7. Annotation as Multimedia Writing

Have students annotate with images and video or integrate images and video into other types of annotations.

One of the unique aspects of online annotation (and online writing in general) is the ability to include multimedia elements in the composition process. We’ve found many teachers and students excited to make use of animated GIFs in annotation. The use of images can simply be representative (this is a reference to Lincoln with a photo of the 16th president), but more advanced students can be taught to think about how images themselves make arguments and serve other rhetorical purposes.

It is advisable to spend a lesson introducing the idea of digital writing to students with particular attention to the use of images, covering everything from search to use policies and attribution. More traditional teachers may be less accustomed to assessing such multimedia compositions and should spend some time thinking about and explaining to their students a grading rubric.

8. Annotation as Independent Study

Have students explore the Internet on their own with some limited direction (find an article from a respectable source on a topic important to you personally), exercising traditional literacy skills (define difficult words, identify persuasive strategies, etc.).

Many of the above exercises presume that students are annotating for the most part together on a shared course text. But the nature of web annotation is that we can see the notes of others even if we are not reading the same text. In this way, we can attend to annotations as texts themselves. Like a friend’s Facebook page or Twitter feed, seeing someone else navigate the world can be interesting. And through web annotation students can be taught to navigate the digital world responsibly and thoughtfully. Protip: because each Hypothesis user’s annotations are streamed on their public “My Annotations” page, teachers can monitor and assess student work there rather than on individual texts if so desired. (You can click on a username attached to an annotation or search the Hypothesis stream for a username to locate this page. Here’s mine. )

Whether or not one goes so far as to let students roam free on the open Web applying their classroom learning, we have found it to be valuable to have a unit develop from collaborative work to independent or small group work. Students might start off annotating together on a few select texts, getting a sense of what annotation means and how a particular platform like Hypothesis works, but by the end of a term become responsible for glossing or analyzing a single text or set of texts themselves.

9. Annotation as Annotated Bibliography

Have students research a topic or theme and tag and annotate relevant texts across the Internet.

This is a different kind of annotation than largely discussed above. Here we are annotating on the level of the document rather than on a particular selection of text. (Users can create unanchored annotations for this purpose using the annotation icon on the sidebar without selecting any particular text within a document.) But this annotation exercise practices solid research skills and can be used as preparation for research assignments. In fact, using annotation as a annotated bibliography assignment is an excellent way for teachers to follow and guide student research during the process itself. The result of this assignment will be something useful for a paper such as a summary of the major stakeholders of a particular issue and how they articulate their positions.

Of course this kind of annotation as page-level commentary can be combined with more fine-grained attention through annotation to the texts of these tagged documents. In addition to outlining sources needed for a paper, the student can begin to break down those sources for close reading within an essay.

10. Annotation as Creative Act

Have students respond creatively to their reading with their own poetry or prose or visual art as annotations.

Annotation need not be overtly analytical. Whether in writing or using other media, students can respond creatively to texts under study through annotation as well, inserting themselves within the intertextual web that is the history of literature and culture. One creative writing exercise might be to have students annotate in the voices of a characters from a novel being read. Or to have them re-imagine passages written as newspaper stories. Nathan Blom’s Annotated Lear Project at LaGuardia Arts High School is a great example of students creatively responding to a text through annotation.

Students can also use their imaginations to annotate texts with their own drawings, photographs, or videos inline with the relevant sources of textual inspiration. Whether completed individually or collaboratively this exercise can result in some wonderful, illustrated editions of course texts.

Share this article

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

Dave Stuart Jr.

Teaching Simplified.

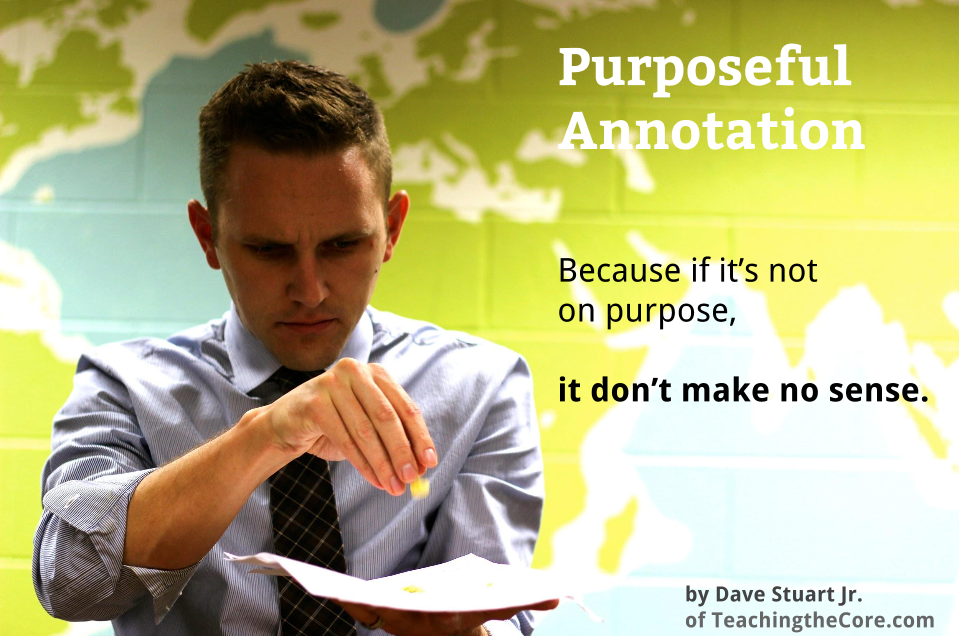

Purposeful Annotation: A “Close Reading” Strategy that Makes Sense to My Students

October 11, 2014 By Dave Stuart Jr. 87 Comments

If you look at my original close reading post , you'll see I was basically using the phrase “close reading” to refer to annotation.

It took me a year or more to realize that I was saying one buzzwordy thing to mean a lot of explicit, less confusing things that readers do when grappling with a text. I blame my error on allowing myself to get sucked into the unfortunate vortex that was the buzzwordification of close reading .

If you’re new to the blog, though, keep in mind that while I do try not to take the educational establishment too terribly seriously (instead opting to occasionally poke fun at us), when it comes to helping students flourish in the long-term, I’m dead serious.

So when I call close reading a buzzword or write the term’s obituary , I don’t want to give you the impression that we should let ourselves cynically dismiss the idea that reading is often hard, analytical — and yes, even “close” — work, especially when we're dealing with complex, college- or career-level texts assigned by a teacher. We still need to teach kids, across the disciplines, how to wrestle with assigned texts, seeking, like Jacob , to get whatever blessing they have to bestow.

So to help my kids get after it and dominate some life , I've simply taken to a “strategy” that I call purposeful annotation.

Purposeful annotation: here's what I’m talking about

The big idea is this: what we do when reading should align with

- why we're doing the reading in the first place and

- what we're going to do with the reading after we're done.

When my students have a text they can write on, the idea, then, is to annotate in a way that supports our purpose for reading and the parameters of our post-reading task (keep in mind that the purpose and the task should line up). Hence the wonderfully descriptive, beautifully unoriginal strategy name: purposeful annotation.

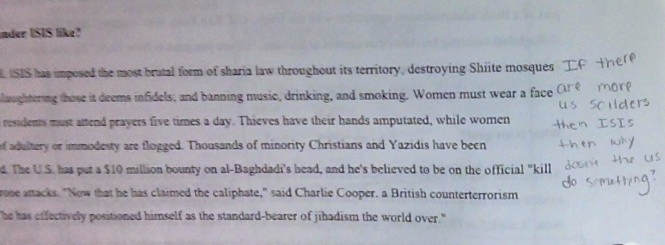

As an example, let’s say I’m helping my students think through the task of purposefully annotating a Kelly Gallagher-esque article of the week . In that case, the purpose I set for my students’ reading is, as The Gallagher put it in a recent post’s comments section , to simply become smarter about the world, and the post-reading task is that they need to write a thoughtful 1+ page response.

In that example, knowing that I want to dominate that post-reading task and that I simply need to get myself engaged with the probably unfamiliar and certainly unchosen content, I, as a student, ought to make annotations that begin to respond to the text. Of course, I can't respond to something I don't understand, and so sometimes, especially when faced with a particularly befuddling sentence, paragraph, or section in the article, I ought to slow down, reread, and then annotate a brief summary or paraphrase of the challenging section in the margin.

So, two things we can annotate, naturally, are 1) our responses to a text, and 2) our paraphrases/summaries of bits of the text we had to wrestle with. These logically line up with what I’m going to do with the text after reading, as well as my purpose for reading it in the first place.

The idea here is that I'm writing these things in the margins — these purposeful annotations — not simply for a grade or because the teacher said, “ Do a close reading. ” I'm doing it to help me dominate:

- the task of understanding and learning from the text while reading (this is one of my ultimate goals for my students — that they'll read the texts I assign with self-kindled, habituated, cultivated curiosity, engaging with it for learning's sake), and

- the task of doing a thing with that text after reading (if my head is on straight as a teacher, there's going to be a piece of writing or a piece of speaking that every student will do with any given text).

This obviously isn’t as broad of a strategy as close reading, and honestly, that’s why I like it — and my students do, too.

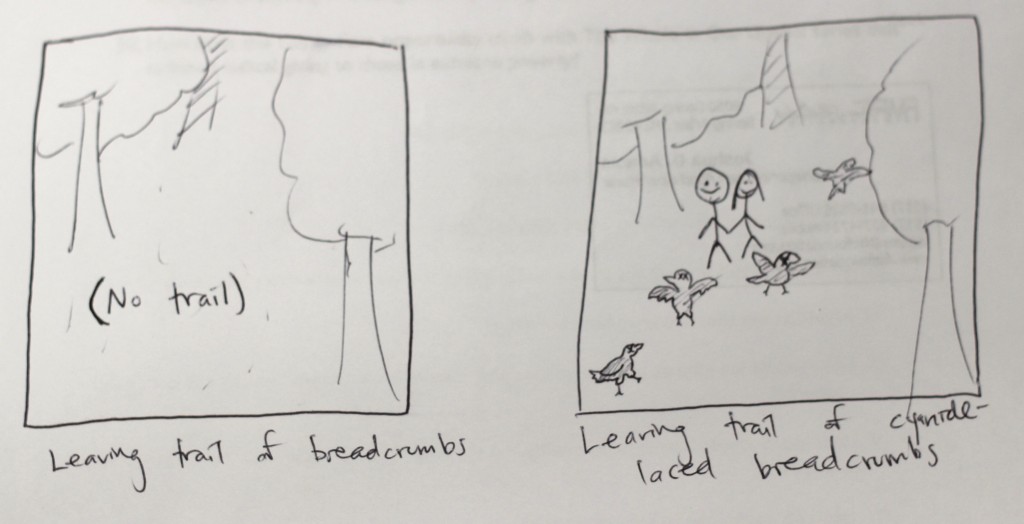

The core idea is that annotation should help the reader during and after reading . It should serve, as my friend and work-sister Erica Beaton has well put it, as the leaving of cyanide-laced breadcrumbs (okay, the cyanide bit is mine — but seriously, that's the right way to put it, because breadcrumbs alone get eaten by birds, while cyanide-laced breadcrumbs leave a nicely traceable, bird-covered trail).

Why teach purposeful annotation rather than some other method?

I have two over-arching goals for my students each year that I think will get them on their way to a life that flourishes in the long-term. I want to help as many kids as possible to figure out

- why school matters to them and their lives, and then

- how to dominate the challenges of school and, more broadly, life.

So much of my thinking is still shaped by one of the central ideas of Jerry Graff's Clueless in Academe — far too many students simply don't understand school, and frustratingly, that simply need not be so. A big part of helping kids “get” academia is showing them how argument is the essence of thought and then teaching them arguespeak across the school day — They Say, I Say remains the best text in the world for helping with that. (Please note that I support my reading habit through Amazon affiliate commissions — if I link to a book anywhere in this blog article, it means I'll get a small gift card to Amazon if you make a purchase through that link. This costs you nothing extra but keeps me hooked up with new books to read. Thank you!)

For me, Graff pointed out both the problem — academia does a great job obscuring itself to students — and a large part of the solution. Arguespeak is the language of power not just in school, but in the world at large — we're foolish not to teach kids that.

Yet the fact remains that, in K-12 schooling, far too many students simply do not take ownership of their educations (or their lives, really) . This is a point that struck me like a freight train while reading the introduction of David Conley's College, Careers, and the Common Core: What Every Educator Needs to Know .

From Conley's book :

The [students] who had the greatest success were those who were willing to take some modicum of ownership of their learning and responsibility for their behavior. Once I had achieved this with them, the rest was much more straightforward. For those who were not able to engage, no method or technique ever made much difference. This lesson about the importance of ownership of learning never completely left me. Interestingly and unexpectedly, I had reached the conclusion that the social contract was a two-way street: society has a responsibility to create a level playing field, and individuals have a responsibility to take advantage of it.

I'm sure I'll write more on ownership of learning this year as it's a central burning question for my colleagues and me, but for the sake of this post suffice it to say that I believe the clearer we can be about what we ask kids to do and why we ask them to do it, the more academia becomes unobscured and the more likely it is that our students will come to a place where they can say, “Yes — schooling matters for me because _______________.”

In short, I've found that the phrase purposeful annotation makes sense to my freshmen and explicitly shows them how to “work smarter not harder” when reading and doing something with a text.

So how do we do the purposeful annotation thing?

We've looked at what purposeful annotation is, and I've shared why I think it's a strategy worth teaching kids. Now let's examine how to actually do the thing.

First, start with the end in mind

Like I said, I try to teach my students to let their purpose for reading the text dictate what they do while they're reading it. For my “what does this look like in a gradebook” readers (I feel you), I do consistently assign a grade to whether my students, at minimum, write 1-2 thoughtful, purpose-driven annotations in the margins of each page of a shorter complex text . ( I explain how I grade articles of the week in this post. )

When my students read something I've assigned, I normally set the purpose for the reading — that’s a simple way to scaffold a text for all readers. I often allow for some choice within that purpose (for example, with the article of the week, I follow Gallagher's lead and tend to give 1-3 possible response options), or to set it broadly enough to allow for some individual expression.

With that said, here are the kinds of annotations I recommend kids try (remember, 1-2 thoughtful interactions per page) based on their purpose for reading.

If your purpose for reading is to learn the content :

- Summarize a sentence or paragraph

- Paraphrase a sentence or paragraph

- Circle and define key words

If your purpose for reading is to end by responding to a specific prompt :

- Annotate toward that prompt. If you’re being asked to evaluate, make evaluative annotations. If you're being asked to analyze, make analytical annotations. If you're thinking, “Um, my kids don't really know what those verbs mean,” then use Jim Burke's A-List .

Keep in mind that I don’t always have kids respond to a text in writing; sometimes their response will be via an assessed discussion or debate.

Second, do it while you read

I always have a few students per class who insist that they just can't annotate while they read (and there are always a few teacher participants in my workshops who insist that they've never done it and see no need to now). Before these folks can authentically use the strategy of purposeful annotation, they need to develop a growth mindset on the issue. Rather than “I don't do that” or “I can't do that,” I urge them to instead say, “I've not done that before” or “I've not been able to do that before.”

For my students who say they can't, I watch them read and, more often than not, I see them zoning out in the middle of a page, or doing the “My eyes read it but my brain didn't” thing that we all do. Annotation, I've found, can help my students focus on a text, especially when that annotation is purposeful rather than “fill in the margins as much as you can.”

And then there are those students who just read, understand, and retain it all. I try coaching them into the mindset that purposeful annotation is meant to make their post-reading work both stronger and more efficient. By choosing to annotate only portions of the text that they want to address further in the writing or speaking we'll be doing after reading, they're allowing their brain to leave those breadcrumbs on the page rather than keeping those notes in their brains (for an awesome article on how not writing things down keeps information in your brain's rehearsal loops , check this out.)

Time out: what about teachers who see no value in annotation?

I know some readers are coaches, administrators, PLC leaders, department chairs, and so on, and if you've been trying to push close reading or annotation at your school, you've probably run into resistant folks. Here are a few things to think about:

- Instead of requiring all teachers to use a complicated coding system when teaching their kids to annotate, empower them with the idea of purposeful annotation. The means need to fit the ends.

- Think deeply about the why . Use my “Why teach…” section above to help.

- Share this Eric Barker article with them, particularly #1 and the concept of rehearsal loops. Annotation allows us to get our 1-2 “I could expand on these in the post-reading writing or speaking task” thoughts on paper and out of our brains' rehearsal loops. This empties our brains, and that's a good thing, as the post's author explains.

Fight relentlessly against this becoming busywork

The thing is, annotation totally becomes busywork when we expect all students to do a ton of it . Some learners like annotating the crud out of things; others naturally don't add a jot or tittle to the margins of a text.

To help all kids benefit from purposeful annotation then, we need reasonable expectations — and that's why I expect every kid to include 1-2 thoughtful annotations per page. “Thoughtful,” you say. “Wow. That's so incredibly descriptive, Dave. Thank you. For nothing.” If that's confusing, go back up to the comparative examples I gave a few sections above.

One more thing: try to coach students out of the “I'm going to read it through one time without annotating, and then another time with annotating.” If they're doing this because they're confused on the first read-through, show them how to break down difficult sections of a text and paraphrase or summarize the gist — this kind of annotating aids comprehension. On the other hand, if they're doing this because they just don't feel like it or they don't like it, we want to help them get the hang of annotating as they read, keeping their purpose for reading in the front of their mind .

The point of having kids do this is helping them efficiently internalize a purpose for reading, read toward that purpose, and then write or speak in line with that purpose.

Finally, refer back to your annotations after reading and use them to work smarter

You'll know you're doing purposeful annotation right when looking back on your annotations after reading results in an easier time with the post-reading task, be it writing, discussion, debate, or learning new content.

Unlike back in the day when I would tell my kids to close read an article, I feel good and clear when I teach them and expect them to purposefully annotate instead. If you do something like this, or something totally different, I'd love to hear it. And, as always, your critiques are welcome, too. So much of what I share on DaveStuartJr.com is the epitome of “rough draft thinking,” down to the smallest, most annoying typos 🙂 (Sorry about those.)

Also, if you're wanting to dig deeper into dominating assigned texts, check out Harvard's six reading habits for “thinking-intensive” reading .

Love you guys,

Reader Interactions

Jennifer Lynn Ringo says

October 11, 2014 at 10:20 am

davestuartjr says

October 11, 2014 at 1:17 pm

lindsay n helfman says

October 18, 2020 at 8:15 pm

I have been thinking about how best to teach these strategies now that we are online for the foreseeable future. I am an experienced reader and purposeful annotator, but even I struggle with annotating digital texts. Do you have any strategies to help students successfully annotate online?

Dave Stuart Jr. says

October 19, 2020 at 1:29 pm

Hi Lindsay! Right now I’m having students make analog notes in spiral notebooks re: lines in articles or books that they want to explore in writing. I just don’t have the heart to ask them to annotate on a screen — because, like you, I rarely do it myself.

That’s where I’m at right now.

October 11, 2014 at 11:46 am

I totally agree with you. I’ve been saying the same thing to the teachers I work with. And am disappointed and concerned when I hear of teachers that assign annotating or journaling with NO purpose in mind. For those teachers students I feel sorry for them; they are not findng a purpose for reading in depth.

October 11, 2014 at 1:18 pm

Carla, thank you! We can spread some sanity on this issue, I think. Share this post liberally, dear comrade 🙂

authenticLiteracy says

October 11, 2014 at 1:46 pm

Hey Dave! You nailed it here. Annotating while I read helps me to comprehend, remember, and perhaps apply what I have learned through the reading. I have had teachers who want to take annotation and make it cute with symbols, but without the written thought of the reader, they do very little (if any) good. You articulated this thinking well in your article! Thank you! Christy

October 11, 2014 at 2:55 pm

Christy, it’s always great to hear from you! Thanks for the feedback and I hope all is well in IL and OH!

jgood03 says

October 11, 2014 at 4:20 pm

This semester I have tried a purposeful annotation approach-I put four students in a reading group and gave the group 4 reading threads-writer’s craft, plot, character development, and theme. Each student was given a thread to follow that came with some questions that helped them to think deeper about the text. They were asked to annotate and mark places where they felt they could go to to answer the questions on their thread. In other words, no one wrote out answers to reading questions, they just kept track of where this information could be found through their annotations,

Once a week we had a group quiz where everyone brought their annotated texts to class to use to answer 3 essay-sque questions about the chapters they read that week. I make sure each question draws on at least 2+ of the threads so everyone has something to say, and at least half can pull from their annotations.

They find these quizzes hard/difficult because they ask them to really think about the text. they also find them meaningful because they help them to understand what is happening in the text, give them an opportunity to talk about difficult spots and get to a point of understanding, and provide them with the opportunity to collaborate.

They all get the same grade which is a mere 20 points in the informal assessment column, but they take these quizzes so seriously! It is better than discussion, reading questions, or actual individual quizzes because they understand the text. I have not had to give 1 lecture about The Scarlet Letter, and yet they are able to relate to McCarthyism, Puritanism, and the Gothic Romantics which we study in class.

I find giving my students a reason to read and annotate so important for self-reliance and gaining the confidence to understand difficult literature.

Stacy Gibbs says

October 11, 2014 at 6:25 pm

Dave – love your ideas and thoughts on purposeful annotation. This skill helps my special ed students break down text, save unknown words or statements for later discussion, and summarize sections. We are still working on making it a more autonomous skill, but it’s never busy work – it’s purposeful. :). Thanks for your info and sense of humor.

October 12, 2014 at 8:21 am

Stacy, that’s my pleasure. I can tell you’re intentional with this, and that’s the key, I think. Take care Stacy 🙂

Shelley Stuart Gibbons says

October 11, 2014 at 10:31 pm

Hi Dave, It’s Saturday night, and a great time to do a little educational reading of Dave Stuart Jr.’s writing. Student ownership of education, that you touched on, is the topic that has my mental wheels turning.

Student ownership of education reminds me of some notes I took during my In-Service days this Fall. The notes listed research results done by Dr. Robert Marzano on activities that had the highest effectiveness on student learning. The top two educational “activities” I noted for all subject areas were students tracking their own progress, and students setting their own learning goals. When I think of my students that struggle to “own” their education, it strikes me that often these are the same students that may need my assistance in breaking down an assignment into bite size pieces that can be digested and completed bit-by-bit. Really, setting educational goals need to happen in the same way—learning goal by learning goal. This would look like an IEP that is reviewed and tweaked every couple of weeks, rather than once a year, and would be written one-on-one between the teacher and student. Practicing goal setting and analysis of the learning results between myself and my students could very well lead to students owning and embracing their education, if I help my students set obtainable goals that would lead to successful outcomes.

And here you thought you were writing about purposeful annotation. :-}

Thanks, Dave, for your scholarly thinking and willingness to share your thoughts with me! I’m proud of you. (Cousin) Shelley

October 13, 2014 at 11:50 am

Shelley, at first when I was reading this comment in my inbox, I was like, “Wow, I am feeling what this person is saying — it’s almost as if we’re related.” And then, sure enough, we were 🙂

Ownership of learning is at the forefront of my thinking and seeking this year. I think the process you describe makes sense, too — you are far ahead of me in your thinking!

Always good to hear from you Shelley! I hope all is well in Cale 🙂

Bev Sims says

October 12, 2014 at 2:53 pm

Years ago , I tried to convince my middle school colleagues the importance of annotating and they just could not accept it. Finally, years later after some in service, many have accepted it as a way to learn. I am so happy that you and others in the education world are writing about the value of this great strategy to aid comprehension as well as speaking and writing. I am truly grateful to you.

October 13, 2014 at 11:48 am