U.S. Constitution.net

The articles of confederation – the u.s. constitution online – usconstitution.net.

Also see the Constitutional Topics Page for this document, a comparison of the Articles and the Constitution , and a table with demographic data for the signers of the Articles . Images of the Articles are available .

The Articles of Confederation

Agreed to by Congress November 15, 1777; ratified and in force, March 1, 1781.

To all to whom these Presents shall come, we the undersigned Delegates of the States affixed to our Names send greeting.

Whereas the Delegates of the United States of America in Congress assembled did on the fifteenth day of November in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy seven, and in the Second Year of the Independence of America, agree to certain articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, in the words following, viz:

Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Article I. The Stile of this Confederacy shall be “The United States of America.”

Article II. Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.

Article III. The said States hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defense, the security of their liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretense whatever.

Article IV. The better to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different States in this union, the free inhabitants of each of these States, paupers, vagabonds, and fugitives from justice excepted, shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several States; and the people of each State shall have free ingress and regress to and from any other State, and shall enjoy therein all the privileges of trade and commerce, subject to the same duties, impositions, and restrictions as the inhabitants thereof respectively, provided that such restrictions shall not extend so far as to prevent the removal of property imported into any State, to any other State, of which the owner is an inhabitant; provided also that no imposition, duties or restriction shall be laid by any State, on the property of the united States, or either of them.

If any person guilty of, or charged with, treason, felony, or other high misdemeanor in any State, shall flee from justice, and be found in any of the united States, he shall, upon demand of the Governor or executive power of the State from which he fled, be delivered up and removed to the State having jurisdiction of his offense.

Full faith and credit shall be given in each of these States to the records, acts, and judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other State.

Article V. For the most convenient management of the general interests of the united States, delegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislatures of each State shall direct, to meet in Congress on the first Monday in November, in every year, with a power reserved to each State to recall its delegates, or any of them, at any time within the year, and to send others in their stead for the remainder of the year.

No State shall be represented in Congress by less than two, nor more than seven members; and no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years; nor shall any person, being a delegate, be capable of holding any office under the united States, for which he, or another for his benefit, receives any salary, fees or emolument of any kind.

Each State shall maintain its own delegates in a meeting of the States, and while they act as members of the committee of the States.

In determining questions in the united States, in Congress assembled, each State shall have one vote.

Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Congress, and the members of Congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests or imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendance on Congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace.

Article VI. No State, without the consent of the united States in Congress assembled, shall send any embassy to, or receive any embassy from, or enter into any conference, agreement, alliance or treaty with any King, Prince or State; nor shall any person holding any office of profit or trust under the united States, or any of them, accept any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever from any King, Prince or foreign State; nor shall the United States in congress assembled, or any of them, grant any title of nobility.

No two or more States shall enter into any treaty, confederation or alliance whatever between them, without the consent of the united States in congress assembled, specifying accurately the purposes for which the same is to be entered into, and how long it shall continue.

No State shall lay any imposts or duties, which may interfere with any stipulations in treaties, entered into by the united States in congress assembled, with any King, Prince or State, in pursuance of any treaties already proposed by congress, to the courts of France and Spain.

No vessel of war shall be kept up in time of peace by any State, except such number only, as shall be deemed necessary by the united States in congress assembled, for the defense of such State, or its trade; nor shall any body of forces be kept up by any State in time of peace, except such number only, as in the judgement of the united States, in congress assembled, shall be deemed requisite to garrison the forts necessary for the defense of such State; but every State shall always keep up a well-regulated and disciplined militia, sufficiently armed and accoutered, and shall provide and constantly have ready for use, in public stores, a due number of field pieces and tents, and a proper quantity of arms, ammunition and camp equipage.

No State shall engage in any war without the consent of the united States in congress assembled, unless such State be actually invaded by enemies, or shall have received certain advice of a resolution being formed by some nation of Indians to invade such State, and the danger is so imminent as not to admit of a delay till the united States in congress assembled can be consulted; nor shall any State grant commissions to any ships or vessels of war, nor letters of marque or reprisal, except it be after a declaration of war by the united States in congress assembled, and then only against the kingdom or State and the subjects thereof, against which war has been so declared, and under such regulations as shall be established by the united States in congress assembled, unless such State be infested by pirates, in which case vessels of war may be fitted out for that occasion, and kept so long as the danger shall continue, or until the united States in congress assembled shall determine otherwise.

Article VII. When land forces are raised by any State for the common defense, all officers of or under the rank of colonel, shall be appointed by the legislature of each State respectively, by whom such forces shall be raised, or in such manner as such State shall direct, and all vacancies shall be filled up by the State which first made the appointment.

Article VIII. All charges of war, and all other expenses that shall be incurred for the common defense or general welfare, and allowed by the united States in congress assembled, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several States in proportion to the value of all land within each State, granted or surveyed for any person, as such land and the buildings and improvements thereon shall be estimated according to such mode as the united States in congress assembled, shall from time to time direct and appoint.

The taxes for paying that proportion shall be laid and levied by the authority and direction of the legislatures of the several States within the time agreed upon by the united States in congress assembled.

Article IX. The united States in congress assembled, shall have the sole and exclusive right and power of determining on peace and war, except in the cases mentioned in the sixth article — of sending and receiving ambassadors — entering into treaties and alliances, provided that no treaty of commerce shall be made whereby the legislative power of the respective States shall be restrained from imposing such imposts and duties on foreigners, as their own people are subjected to, or from prohibiting the exportation or importation of any species of goods or commodities whatsoever — of establishing rules for deciding in all cases, what captures on land or water shall be legal, and in what manner prizes taken by land or naval forces in the service of the United States shall be divided or appropriated — of granting letters of marque and reprisal in times of peace — appointing courts for the trial of piracies and felonies committed on the high seas and establishing courts for receiving and determining finally appeals in all cases of captures, provided that no member of Congress shall be appointed a judge of any of the said courts.

The United States in Congress assembled shall also be the last resort on appeal in all disputes and differences now subsisting or that hereafter may arise between two or more States concerning boundary, jurisdiction or any other causes whatever; which authority shall always be exercised in the manner following. Whenever the legislative or executive authority or lawful agent of any State in controversy with another shall present a petition to Congress stating the matter in question and praying for a hearing, notice thereof shall be given by order of Congress to the legislative or executive authority of the other State in controversy, and a day assigned for the appearance of the parties by their lawful agents, who shall then be directed to appoint by joint consent, commissioners or judges to constitute a court for hearing and determining the matter in question: but if they cannot agree, Congress shall name three persons out of each of the United States, and from the list of such persons each party shall alternately strike out one, the petitioners beginning, until the number shall be reduced to thirteen; and from that number not less than seven, nor more than nine names as Congress shall direct, shall in the presence of Congress be drawn out by lot, and the persons whose names shall be so drawn or any five of them, shall be commissioners or judges, to hear and finally determine the controversy, so always as a major part of the judges who shall hear the cause shall agree in the determination: and if either party shall neglect to attend at the day appointed, without showing reasons, which Congress shall judge sufficient, or being present shall refuse to strike, the Congress shall proceed to nominate three persons out of each State, and the secretary of Congress shall strike in behalf of such party absent or refusing; and the judgement and sentence of the court to be appointed, in the manner before prescribed, shall be final and conclusive; and if any of the parties shall refuse to submit to the authority of such court, or to appear or defend their claim or cause, the court shall nevertheless proceed to pronounce sentence, or judgement, which shall in like manner be final and decisive, the judgement or sentence and other proceedings being in either case transmitted to Congress, and lodged among the acts of Congress for the security of the parties concerned: provided that every commissioner, before he sits in judgement, shall take an oath to be administered by one of the judges of the supreme or superior court of the State, where the cause shall be tried, ‘well and truly to hear and determine the matter in question, according to the best of his judgement, without favor, affection or hope of reward’: provided also, that no State shall be deprived of territory for the benefit of the United States.

All controversies concerning the private right of soil claimed under different grants of two or more States, whose jurisdictions as they may respect such lands, and the States which passed such grants are adjusted, the said grants or either of them being at the same time claimed to have originated antecedent to such settlement of jurisdiction, shall on the petition of either party to the Congress of the United States, be finally determined as near as may be in the same manner as is before prescribed for deciding disputes respecting territorial jurisdiction between different States.

The United States in Congress assembled shall also have the sole and exclusive right and power of regulating the alloy and value of coin struck by their own authority, or by that of the respective States — fixing the standards of weights and measures throughout the United States — regulating the trade and managing all affairs with the Indians, not members of any of the States, provided that the legislative right of any State within its own limits be not infringed or violated — establishing or regulating post offices from one State to another, throughout all the United States, and exacting such postage on the papers passing through the same as may be requisite to defray the expenses of the said office — appointing all officers of the land forces, in the service of the United States, excepting regimental officers — appointing all the officers of the naval forces, and commissioning all officers whatever in the service of the United States — making rules for the government and regulation of the said land and naval forces, and directing their operations.

The United States in Congress assembled shall have authority to appoint a committee, to sit in the recess of Congress, to be denominated ‘A Committee of the States’, and to consist of one delegate from each State; and to appoint such other committees and civil officers as may be necessary for managing the general affairs of the United States under their direction — to appoint one of their members to preside, provided that no person be allowed to serve in the office of president more than one year in any term of three years; to ascertain the necessary sums of money to be raised for the service of the United States, and to appropriate and apply the same for defraying the public expenses — to borrow money, or emit bills on the credit of the United States, transmitting every half-year to the respective States an account of the sums of money so borrowed or emitted — to build and equip a navy — to agree upon the number of land forces, and to make requisitions from each State for its quota, in proportion to the number of white inhabitants in such State; which requisition shall be binding, and thereupon the legislature of each State shall appoint the regimental officers, raise the men and cloath, arm and equip them in a solid- like manner, at the expense of the United States; and the officers and men so cloathed, armed and equipped shall march to the place appointed, and within the time agreed on by the United States in Congress assembled. But if the United States in Congress assembled shall, on consideration of circumstances judge proper that any State should not raise men, or should raise a smaller number of men than the quota thereof, such extra number shall be raised, officered, cloathed, armed and equipped in the same manner as the quota of each State, unless the legislature of such State shall judge that such extra number cannot be safely spread out in the same, in which case they shall raise, officer, cloath, arm and equip as many of such extra number as they judge can be safely spared. And the officers and men so cloathed, armed, and equipped, shall march to the place appointed, and within the time agreed on by the united States in congress assembled.

The united States in congress assembled shall never engage in a war, nor grant letters of marque or reprisal in time of peace, nor enter into any treaties or alliances, nor coin money, nor regulate the value thereof, nor ascertain the sums and expenses necessary for the defense and welfare of the United States, or any of them, nor emit bills, nor borrow money on the credit of the united States, nor appropriate money, nor agree upon the number of vessels of war, to be built or purchased, or the number of land or sea forces to be raised, nor appoint a commander in chief of the army or navy, unless nine States assent to the same: nor shall a question on any other point, except for adjourning from day to day be determined, unless by the votes of the majority of the united States in congress assembled.

The congress of the united States shall have power to adjourn to any time within the year, and to any place within the united States, so that no period of adjournment be for a longer duration than the space of six months, and shall publish the journal of their proceedings monthly, except such parts thereof relating to treaties, alliances or military operations, as in their judgement require secrecy; and the yeas and nays of the delegates of each State on any question shall be entered on the journal, when it is desired by any delegates of a State, or any of them, at his or their request shall be furnished with a transcript of the said journal, except such parts as are above excepted, to lay before the legislatures of the several States.

Article X. The committee of the States, or any nine of them, shall be authorized to execute, in the recess of congress, such of the powers of congress as the united States in congress assembled, by the consent of the nine States, shall from time to time think expedient to vest them with; provided that no power be delegated to the said Committee, for the exercise of which, by the articles of confederation, the voice of nine States in the Congress of the United States assembled be requisite.

Article XI. Canada acceding to this confederation, and adjoining in the measures of the united States, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this union; but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine States.

Article XII. All bills of credit emitted, monies borrowed, and debts contracted by, or under the authority of congress, before the assembling of the united States, in pursuance of the present confederation, shall be deemed and considered as a charge against the United States, for payment and satisfaction whereof the said united States, and the public faith are hereby solemnly pledged.

Article XIII. Every State shall abide by the determination of the united States in congress assembled, on all questions which by this confederation are submitted to them. And the Articles of this confederation shall be inviolably observed by every State, and the union shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a congress of the united States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.

And Whereas it hath pleased the Great Governor of the World to incline the hearts of the legislatures we respectively represent in Congress, to approve of, and to authorize us to ratify the said articles of confederation and perpetual union. Know Ye that we the undersigned delegates, by virtue of the power and authority to us given for that purpose, do by these presents, in the name and in behalf of our respective constituents, fully and entirely ratify and confirm each and every of the said articles of confederation and perpetual union, and all and singular the matters and things therein contained: And we do further solemnly plight and engage the faith of our respective constituents, that they shall abide by the determinations of the united States in congress assembled, on all questions, which by the said confederation are submitted to them. And that the articles thereof shall be inviolably observed by the States we respectively represent, and that the union shall be perpetual.

In Witness whereof we have hereunto set our hands in Congress. Done at Philadelphia in the State of Pennsylvania the ninth Day of July in the Year of our Lord one thousand seven Hundred and Seventy-eight, and in the Third Year of the independence of America.

On the part and behalf of the State of New Hampshire: Josiah Bartlett John Wentworth Junr. August 8th 1778

On the part and behalf of The State of Massachusetts Bay: John Hancock Samuel Adams Elbridge Gerry Francis Dana James Lovell Samuel Holten

On the part and behalf of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations: William Ellery Henry Marchant John Collins

On the part and behalf of the State of Connecticut: Roger Sherman Samuel Huntington Oliver Wolcott Titus Hosmer Andrew Adams

On the Part and Behalf of the State of New York: James Duane Francis Lewis Wm Duer Gouv Morris

On the Part and in Behalf of the State of New Jersey, November 26, 1778. Jno Witherspoon Nath. Scudder

On the part and behalf of the State of Pennsylvania: Robt Morris Daniel Roberdeau John Bayard Smith William Clingan Joseph Reed 22nd July 1778

On the part and behalf of the State of Delaware: Tho Mckean February 12, 1779 John Dickinson May 5th 1779 Nicholas Van Dyke

On the part and behalf of the State of Maryland: John Hanson March 1 1781 Daniel Carroll

On the Part and Behalf of the State of Virginia: Richard Henry Lee John Banister Thomas Adams Jno Harvie Francis Lightfoot Lee

On the part and Behalf of the State of No Carolina: John Penn July 21st 1778 Corns Harnett Jno Williams

On the part and behalf of the State of South Carolina: Henry Laurens William Henry Drayton Jno Mathews Richd Hutson Thos Heyward Junr

On the part and behalf of the State of Georgia: Jno Walton 24th July 1778 Edwd Telfair Edwd Langworthy

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Articles of Confederation

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 15, 2023 | Original: October 27, 2009

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was the first written constitution of the United States. Written in 1777 and stemming from wartime urgency, its progress was slowed by fears of central authority and extensive land claims by states. It was not ratified until March 1, 1781.

Under these articles, the states remained sovereign and independent, with Congress serving as the last resort on appeal of disputes. Significantly, The Articles of Confederation named the new nation “The United States of America.”

Congress was given the authority to make treaties and alliances, maintain armed forces and coin money. However, the central government lacked the ability to levy taxes and regulate commerce, issues that led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 for the creation of new federal laws under The United States Constitution.

From the beginning of the American Revolution , Congress felt the need for a stronger union and a government powerful enough to defeat Great Britain. During the early years of the war this desire became a belief that the new nation must have a constitutional order appropriate to its republican character.

A fear of central authority inhibited the creation of such a government, and widely shared political theory held that a republic could not adequately serve a large nation such as the United States. The legislators of a large republic would be unable to remain in touch with the people they represented, and the republic would inevitably degenerate into a tyranny.

To many Americans, their union seemed to be simply a league of confederated states, and their Congress a diplomatic assemblage representing 13 independent polities. The impetus for an effective central government lay in wartime urgency, the need for foreign recognition and aid and the growth of national feeling.

Who Wrote the Articles of Confederation?

Altogether, six drafts of the Articles were prepared before Congress settled on a final version in 1777. Benjamin Franklin wrote the first and presented it to Congress in July 1775. It was never formally considered. Later in the year Silas Deane, a delegate from Connecticut, offered one of his own, which was followed still later by a draft from the Connecticut delegation, probably a revision of Deane’s.

None of these drafts contributed significantly to the fourth version written by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, the text that after much revision provided the basis for the Articles approved by Congress. Dickinson prepared his draft in June 1776; it was revised by a committee of Congress and discussed in late July and August. The result, the third version of Dickinson’s original, was printed to enable Congress to consider it further. In November 1777 the final Articles, much altered by this long deliberative process, were approved for submission to the states.

Ratification of the Articles of Confederation

By 1779 all the states had approved the Articles of Confederation except Maryland, but the prospects for acceptance looked bleak because claims to western lands by other states set Maryland in inflexible opposition. Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Connecticut and Massachusetts claimed by their charters to extend to the “South Sea” or the Mississippi River.

The charters of Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware and Rhode Island confined those states to a few hundred miles of the Atlantic. Land speculators in Maryland and these other “landless states” insisted that the West belonged to the United States, and they urged Congress to honor their claims to western lands. Maryland also supported the demands because nearby Virginia would clearly dominate its neighbor should its claims be accepted.

Eventually Thomas Jefferson persuaded his state to yield its claims to the West, provided that the speculators’ demands were rejected and the West was divided into new states, which would be admitted into the Union on the basis of equality with the old. Virginia’s action persuaded Maryland to ratify the Articles, which went into effect on March 1, 1781.

Weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation

The weakness of the Articles of Confederation was that Congress was not strong enough to enforce laws or raise taxes, making it difficult for the new nation to repay their debts from the Revolutionary War. There was no executive and no judiciary, two of the three branches of government we have today to act as a system of checks and balances. Additionally, there were several issues between states that were not settled with ratification: A disagreement over the appointment of taxes forecast the division over slavery in the Constitutional Convention.

Dickinson’s draft required the states to provide money to Congress in proportion to the number of their inhabitants, black and white, except Indians not paying taxes. With large numbers of slaves, the southern states opposed this requirement, arguing that taxes should be based on the number of white inhabitants. This failed to pass, but eventually the southerners had their way as Congress decided that each state’s contribution should rest on the value of its lands and improvements. In the middle of the war, Congress had little time and less desire to take action on such matters as the slave trade and fugitive slaves, both issues receiving much attention in the Constitutional Convention.

Article III described the confederation as “a firm league of friendship” of states “for their common defense, the security of their liberties and their mutual and general welfare.” This league would have a unicameral congress as the central institution of government; as in the past, each state had one vote, and delegates were elected by state legislatures. Under the Articles, each state retained its “sovereignty, freedom and independence.” The old weakness of the First and Second Continental Congresses remained: the new Congress could not levy taxes, nor could it regulate commerce. Its revenue would come from the states, each contributing according to the value of privately owned land within its borders.

But Congress would exercise considerable powers: it was given jurisdiction over foreign relations with the authority to make treaties and alliances; it could make war and peace, maintain an army and navy, coin money, establish a postal service and manage Indian affairs; it could establish admiralty courts and it would serve as the last resort on appeal of disputes between the states. Decisions on certain specified matters–making war, entering treaties, regulating coinage, for example–required the assent of nine states in Congress, and all others required a majority.

Although the states remained sovereign and independent, no state was to impose restrictions on the trade or the movement of citizens of another state not imposed on its own. The Articles also required each state to extend “full faith and credit” to the judicial proceedings of the others. And the free inhabitants of each state were to enjoy the “privileges and immunities of free citizens” of the others. Movement across state lines was not to be restricted.

To amend the Articles, the legislatures of all thirteen states would have to agree. This provision, like many in the Articles, indicated that powerful provincial loyalties and suspicions of central authority persisted. In the 1780s–the so-called Critical Period–state actions powerfully affected politics and economic life.

For the most part, business prospered and the economy grew. Expansion into the West proceeded and population increased. National problems persisted, however, as American merchants were barred from the British West Indies and the British army continued to hold posts in the Old Northwest, which was named American territory under the Treaty of Paris .

These circumstances contributed to a sense that constitutional revision was imperative. Still, national feeling grew slowly in the 1780s, although major efforts to amend the Articles in order to give Congress the power to tax failed in 1781 and 1786. The year after the failure of 1786, the Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia and effectively closed the history of government under the Articles of Confederation.

The Articles of Confederation Text

To all to whom these Presents shall come, we the undersigned Delegates of the States affixed to our Names send greeting.

Whereas the Delegates of the United States of America in Congress assembled did on the fifteenth day of November in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy seven, and in the Second Year of the Independence of America, agree to certain articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia, in the words following, viz:

Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of New Hampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

Thirteen Articles:

The Stile of this confederacy shall be "The United States of America."

Article II.

Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.

Article III.

The said states hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.

Article IV.

The better to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different states in this union, the free inhabitants of each of these states, paupers, vagabonds and fugitives from justice excepted, shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several states; and the people of each state shall have free ingress and regress to and from any other state, and shall enjoy therein all the privileges of trade and commerce, subject to the same duties impositions and restrictions as the inhabitants thereof respectively, provided that such restriction shall not extend so far as to prevent the removal of property imported into any state, to any other state, of which the Owner is an inhabitant; provided also that no imposition, duties or restriction shall be laid by any state, on the property of the united states, or either of them. If any Person guilty of, or charged with treason, felony, — or other high misdemeanor in any state, shall flee from Justice, and be found in any of the united states, he shall, upon demand of the Governor or executive power, of the state from which he fled, be delivered up and removed to the state having jurisdiction of his offense. Full faith and credit shall be given in each of these states to the records, acts and judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other state.

For the more convenient management of the general interests of the united states, delegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislature of each state shall direct, to meet in Congress on the first Monday in November, in every year, with a power reserved to each state, to recal its delegates, or any of them, at any time within the year, and to send others in their stead, for the remainder of the Year.

No state shall be represented in Congress by less than two, nor by more than seven Members; and no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years; nor shall any person, being a delegate, be capable of holding any office under the united states, for which he, or another for his benefit receives any salary, fees or emolument of any kind.

Each state shall maintain its own delegates in a meeting of the states, and while they act as members of the committee of the states. In determining questions in the united states in Congress assembled, each state shall have one vote.

Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any Court, or place out of Congress, and the members of congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests and imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendance on congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace.

Article VI.

No state, without the Consent of the united states in congress assembled, shall send any embassy to, or receive any embassy from, or enter into any conference agreement, alliance or treaty with any King prince or state; nor shall any person holding any office of profit or trust under the united states, or any of them, accept of any present, emolument, office or title of any kind whatever from any king, prince or foreign state; nor shall the united states in congress assembled, or any of them, grant any title of nobility.

No two or more states shall enter into any treaty, confederation or alliance whatever between them, without the consent of the united states in congress assembled, specifying accurately the purposes for which the same is to be entered into, and how long it shall continue.

No state shall lay any imposts or duties, which may interfere with any stipulations in treaties, entered into by the united states in congress assembled, with any king, prince or state, in pursuance of any treaties already proposed by congress, to the courts of France and Spain.

No vessels of war shall be kept up in time of peace by any state, except such number only, as shall be deemed necessary by the united states in congress assembled, for the defence of such state, or its trade; nor shall any body of forces be kept up by any state, in time of peace, except such number only, as in the judgment of the united states, in congress assembled, shall be deemed requisite to garrison the forts necessary for the defence of such state; but every state shall always keep up a well regulated and disciplined militia, sufficiently armed and accoutered, and shall provide and constantly have ready for use, in public stores, a due number of field pieces and tents, and a proper quantity of arms, ammunition and camp equipage. No state shall engage in any war without the consent of the united states in congress assembled, unless such state be actually invaded by enemies, or shall have received certain advice of a resolution being formed by some nation of Indians to invade such state, and the danger is so imminent as not to admit of a delay till the united states in congress assembled can be consulted: nor shall any state grant commissions to any ships or vessels of war, nor letters of marque or reprisal, except it be after a declaration of war by the united states in congress assembled, and then only against the kingdom or state and the subjects thereof, against which war has been so declared, and under such regulations as shall be established by the united states in congress assembled, unless such state be infested by pirates, in which case vessels of war may be fitted out for that occasion, and kept so long as the danger shall continue, or until the united states in congress assembled, shall determine otherwise.

Article VII.

When land-forces are raised by any state for the common defence, all officers of or under the rank of colonel, shall be appointed by the legislature of each state respectively, by whom such forces shall be raised, or in such manner as such state shall direct, and all vacancies shall be filled up by the State which first made the appointment.

Article VIII.

All charges of war, and all other expences that shall be incurred for the common defence or general welfare, and allowed by the united states in congress assembled, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several states in proportion to the value of all land within each state, granted to or surveyed for any Person, as such land and the buildings and improvements thereon shall be estimated according to such mode as the united states in congress assembled, shall from time to time direct and appoint.

The taxes for paying that proportion shall be laid and levied by the authority and direction of the legislatures of the several states within the time agreed upon by the united states in congress assembled.

Article IX.

The united states in congress assembled, shall have the sole and exclusive right and power of determining on peace and war, except in the cases mentioned in the sixth article — of sending and receiving ambassadors — entering into treaties and alliances, provided that no treaty of commerce shall be made whereby the legislative power of the respective states shall be restrained from imposing such imposts and duties on foreigners as their own people are subjected to, or from prohibiting the exportation or importation of any species of goods or commodities, whatsoever — of establishing rules for deciding in all cases, what captures on land or water shall be legal, and in what manner prizes taken by land or naval forces in the service of the united states shall be divided or appropriated — of granting letters of marque and reprisal in times of peace — appointing courts for the trial of piracies and felonies committed on the high seas and establishing courts for receiving and determining finally appeals in all cases of captures, provided that no member of congress shall be appointed a judge of any of the said courts.

The united states in congress assembled shall also be the last resort on appeal in all disputes and differences now subsisting or that hereafter may arise between two or more states concerning boundary, jurisdiction or any other cause whatever; which authority shall always be exercised in the manner following. Whenever the legislative or executive authority or lawful agent of any state in controversy with another shall present a petition to congress stating the matter in question and praying for a hearing, notice thereof shall be given by order of congress to the legislative or executive authority of the other state in controversy, and a day assigned for the appearance of the parties by their lawful agents, who shall then be directed to appoint by joint consent, commissioners or judges to constitute a court for hearing and determining the matter in question: but if they cannot agree, congress shall name three persons out of each of the united states, and from the list of such persons each party shall alternately strike out one, the petitioners beginning, until the number shall be reduced to thirteen; and from that number not less than seven, nor more than nine names as congress shall direct, shall in the presence of congress be drawn out by lot, and the persons whose names shall be so drawn or any five of them, shall be commissioners or judges, to hear and finally determine the controversy, so always as a major part of the judges who shall hear the cause shall agree in the determination: and if either party shall neglect to attend at the day appointed, without showing reasons, which congress shall judge sufficient, or being present shall refuse to strike, the congress shall proceed to nominate three persons out of each state, and the secretary of congress shall strike in behalf of such party absent or refusing; and the judgment and sentence of the court to be appointed, in the manner before prescribed, shall be final and conclusive; and if any of the parties shall refuse to submit to the authority of such court, or to appear or defend their claim or cause, the court shall nevertheless proceed to pronounce sentence, or judgment, which shall in like manner be final and decisive, the judgment or sentence and other proceedings being in either case transmitted to congress, and lodged among the acts of congress for the security of the parties concerned: provided that every commissioner, before he sits in judgment, shall take an oath to be administered by one of the judges of the supreme or superior court of the state, where the cause shall be tried, "well and truly to hear and determine the matter in question, according to the best of his judgment, without favour, affection or hope of reward:" provided also, that no state shall be deprived of territory for the benefit of the united states.

All controversies concerning the private right of soil claimed under different grants of two or more states, whose jurisdictions as they may respect such lands, and the states which passed such grants are adjusted, the said grants or either of them being at the same time claimed to have originated antecedent to such settlement of jurisdiction, shall on the petition of either party to the congress of the united states, be finally determined as near as may be in the same manner as is before prescribed for deciding disputes respecting territorial jurisdiction between different states.

The united states in congress assembled shall also have the sole and exclusive right and power of regulating the alloy and value of coin struck by their own authority, or by that of the respective states — fixing the standard of weights and measures throughout the united states — regulating the trade and managing all affairs with the Indians, not members of any of the states, provided that the legislative right of any state within its own limits be not infringed or violated — establishing or regulating post offices from one state to another, throughout all the united states, and exacting such postage on the papers passing thro' the same as may be requisite to defray the expences of the said office — appointing all officers of the land forces, in the service of the united states, excepting regimental officers — appointing all the officers of the naval forces, and commissioning all officers whatever in the service of the united states — making rules for the government and regulation of the said land and naval forces, and directing their operations.

The united states in congress assembled shall have authority to appoint a committee, to sit in the recess of congress, to be denominated "A Committee of the States," and to consist of one delegate from each state; and to appoint such other committees and civil officers as may be necessary for managing the general affairs of the united states under their direction — to appoint one of their number to preside, provided that no person be allowed to serve in the office of president more than one year in any term of three years; to ascertain the necessary sums of money to be raised for the service of the united states, and to appropriate and apply the same for defraying the public expences to borrow money, or emit bills on the credit of the united states, transmitting every half year to the respective states an account of the sums of money so borrowed or emitted, — to build and equip a navy — to agree upon the number of land forces, and to make requisitions from each state for its quota, in proportion to the number of white inhabitants in such state; which requisition shall be binding, and thereupon the legislature of each state shall appoint the regimental officers, raise the men and cloth, arm and equip them in a soldier like manner, at the expence of the united states; and the officers and men so cloathed, armed and quipped shall march to the place appointed, and within the time agreed on by the united states in congress assembled: But if the united states in congress assembled shall, on consideration of circumstances judge proper that any state should not raise men, or should raise a smaller number than its quota, and that any other state should raise a greater number of men than the quota thereof, such extra number shall be raised, officered, cloathed, armed and equipped in the same manner as the quota of such state, unless the legislature of such sta te shall judge that such extra number cannot be safely spared out of the same, in which case they shall raise officer, cloath, arm and equip as many of such extra number as they judge can be safely spared. And the officers and men so cloathed, armed and equipped, shall march to the place appointed, and within the time agreed on by the united states in congress assembled.

The united states in congress assembled shall never engage in a war, nor grant letters of marque and reprisal in time of peace, nor enter into any treaties or alliances, nor coin money, nor regulate the value thereof, nor ascertain the sums and expences necessary for the defence and welfare of the united states, or any of them, nor emit bills, nor borrow money on the credit of the united states, nor appropriate money, nor agree upon the number of vessels of war, to be built or purchased, or the number of land or sea forces to be raised, nor appoint a commander in chief of the army or navy, unless nine states assent to the same: nor shall a question on any other point, except for adjourning from day to day be determined, unless by the votes of a majority of the united states in congress assembled.

The congress of the united states shall have power to adjourn to any time within the year, and to any place within the united states, so that no period of adjournment be for a longer duration than the space of six Months, and shall publish the Journal of their proceedings monthly, except such parts thereof relating to treaties, alliances or military operations, as in their judgment require secrecy; and the yeas and nays of the delegates of each state on any question shall be entered on the Journal, when it is desired by any delegate; and the delegates of a state, or any of them, at his or their request shall be furnished with a transcript of the said Journal, except such parts as are above excepted, to lay before the legislatures of the several states.

The committee of the states, or any nine of them, shall be authorized to execute, in the recess of congress, such of the powers of congress as the united states in congress assembled, by the consent of nine states, shall from time to time think expedient to vest them with; provided that no power be delegated to the said committee, for the exercise of which, by the articles of confederation, the voice of nine states in the congress of the united states assembled is requisite.

Article XI.

Canada acceding to this confederation, and joining in the measures of the united states, shall be admitted into, and entitled to all the advantages of this union: but no other colony shall be admitted into the same, unless such admission be agreed to by nine states.

Article XII.

All bills of credit emitted, monies borrowed and debts contracted by, or under the authority of congress, before the assembling of the united states, in pursuance of the present confederation, shall be deemed and considered as a charge against the united states, for payment and satisfaction whereof the said united states, and the public faith are hereby solemnly pledged.

Article XIII.

Every state shall abide by the determinations of the united states in congress assembled, on all questions which by this confederation are submitted to them. And the Articles of this confederation shall be inviolably observed by every state, and the union shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a congress of the united states, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every state.

Conclusion:

And Whereas it hath pleased the Great Governor of the World to incline the hearts of the legislatures we respectively represent in congress, to approve of, and to authorize us to ratify the said articles of confederation and perpetual union. Know Ye that we the undersigned delegates, by virtue of the power and authority to us given for that pur pose, do by these presents, in the name and in behalf of our respective constituents, fully and entirely ratify and confirm each and every of the said articles of confederation and perpetual union, and all and singular the matters and things therein contained: And we do further solemnly plight and engage the faith of our respective constituents, that they shall abide by the determinations of the united states in congress assembled, on all questions, which by the said confederation are submitted to them. And that the articles thereof shall be inviolably observed by the states we respectively represent, and that the union shall be perpetual.

In Witness whereof we have hereunto set our hands in Congress. Done at Philadelphia in the state of Pennsylvania the ninth day of July in the Year of our Lord one Thousand seven Hundred and Seventy-eight, and in the third year of the independence of America.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Articles of Confederation: Article VIII Summary

The moneymaker.

- Expenses from wars and other matters of the national government will be paid for out of a national treasury.

- States will pay proportional taxes based on how rich they are in terms of land.

- States will be responsible for collecting taxes and sending them to the national government by themselves.

- Pretty please?

Tired of ads?

Cite this source, logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

Open 365 days a year, Mount Vernon is located just 15 miles south of Washington DC.

From the mansion to lush gardens and grounds, intriguing museum galleries, immersive programs, and the distillery and gristmill. Spend the day with us!

Discover what made Washington "first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen".

The Mount Vernon Ladies Association has been maintaining the Mount Vernon Estate since they acquired it from the Washington family in 1858.

Need primary and secondary sources, videos, or interactives? Explore our Education Pages!

The Washington Library is open to all researchers and scholars, by appointment only.

The Articles of Confederation

The Second Continental Congress began laying the groundwork for an independent United States on June 11, 1776, when it passed resolutions appointing committees to draft the Articles of Confederation and the Declaration of Independence. The Articles resolution ordered “a committee to be appointed to prepare and digest the form of a confederation to be entered into between these colonies.” 1 John Dickinson, the chairman of the committee tasked with creating a confederation, worked with twelve other committee members to prepare draft articles. They presented their work to Congress on July 12, 1776, and the delegates began to debate the plan soon thereafter. Wary and conscious of repeated British intrusions on their civil and political rights since the early 1760s, the Articles’ framers carefully considered state sovereignty, the proposed national government’s specific powers, and the structure of each government branch as they wrote and debated their plan. They sought to create a government subordinate to the states with power sufficiently checked to prevent the kind of infringements that Americans had experienced under British rule. Congress debated the Articles with these concerns in mind, and it approved the final draft of the Articles on November 15, 1777. Two days later, Congress sent it to the states for ratification. The Articles required unanimous consent from the thirteen states to take effect. Maryland became the final state to ratify the document on March 1, 1781.

The Articles of Confederation featured a preamble and thirteen articles that granted the bulk of power to the states. To some degree, it was a treaty of alliance between thirteen sovereign republics rather than the foundation for a national government. The preamble announced that the states were in a “perpetual union” with one another, but despite this seemingly stringent description, the Articles merely organized the states into a loose compact in which they mostly governed themselves. 2 The first article provided the new nation with its name: “the United States of America.” 3 The remaining articles detailed the states’ relationship with each other and with Congress. Article II provided that “each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence.” Article III, in which the states agreed to “enter into a firm league of friendship with each other,” did not negate an individual state’s sovereign status. 4 Article IV specified the rights of citizens within the several states, such as affording citizens the same privileges and immunities and allowing freedom of movement. Article IV also afforded full faith and credit to “the records, acts, and judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other state.” 5 Article V gave each state only one vote in Congress, ensuring the idea of equality among the states. Other articles discussed the powers granted to Congress, including the power to levy war, send and receive ambassadors, create treaties, grant letters of marque and reprisal, regulate the value of coin, and establish post offices. The final article, Article XIII, required unanimous ratification for all amendments. It also featured a supremacy clause obligating every state to follow the Articles of Confederation.

Three years after the ratification of the Articles of Confederation, many Americans including George Washington began to argue that the perpetual union was in danger. On January 18, 1784, Washington wrote to Virginia governor Benjamin Harrison that the government was “a half starved, limping Government, that appears to be always moving upon crutches, & tottering at every step.” 6 Washington and other Americans had witnessed several crises during the United States’ early years under the Articles, leading to a belief among many that preventing the nation’s collapse required revisiting the Articles. On June 27, 1786, John Jay confided in Washington that “Our affairs seem to lead to some crisis . . . I am uneasy and apprehensive—more so, than during the War.” 7 In Jay’s opinion, one many leading Americans shared, the national government’s weakness led to serious problems that threatened the nation’s survival.

Congress possessed only enumerated powers under the Articles of Confederation. It had no real power to tax, regulate commerce, or raise an army. The inability to tax created major obstacles for the new nation. Without the ability to tax the states or citizens, Congress could not raise revenue, which it needed to pay war debts to international creditors. Congress could only request money from states, and frequently, states would donate only a portion of the request or nothing at all. Between 1781 and 1787, Congress only received $1.5 million of the $10 million that it had requested from the states.

In April 1783, Congress proposed an amendment to the Articles that would allow Congress to levy a five percent tariff on imports for no more than twenty-five years. The revenue from the proposed tariff was specifically earmarked to pay war debts. Given the unanimous amendment process, all states had to ratify the impost for it to take effect. All states but New York had adopted the impost by early 1786. In May 1786, New York’s legislature was willing to adopt the impost with some alterations. However, Congress did not want to accept these alterations and requested that New York remove them. When New York refused to do so in February 1787, the attempt at giving Congress the power to tax, at least in some capacity, was over.

Shays’ Rebellion coincided with the impost ratification process. Led by Daniel Shays, the rebellion was comprised of indebted farmers in western Massachusetts, many of whom were Revolutionary War veterans that had lost much of their land due to foreclosures. They could not pay the high taxes that states had imposed in order to eliminate war debt. Congress had no ability to raise its own army to suppress the rebellion, forcing the nation to rely on a privately financed Massachusetts army to put down the insurrection. This exemplified the need for not only Congress to have the ability to tax, but also the power to raise an army. Additionally, the Articles did not give Congress the power to regulate commerce explicitly. Although it could negotiate treaties and regulate all American coin, it did not have the power to negotiate complex trade treaties with foreign nations and the Articles failed to create a singular uniform currency. This lack of universal currency made trade between states and foreign nations difficult, and led to inconsistencies in currency exchange rates among the states.

Despite the Articles’ weaknesses, it also had numerous strengths. Foremost, it enabled the country to prosecute the Revolutionary War. Because Congress observed that the Articles were its de facto government until officially ratified in 1781, the Articles allowed the country to create a treaty of alliance with France in 1778. It also allowed for the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, which ended the war. The Articles enabled Congress to create the Departments of Foreign Affairs, Wars, Marine, and Treasury, allowed for the establishment of post offices, and had a provision that would permit Canada to join the Union in the future. Congress’s most significant legislative achievement under the Articles was its passage of a series of land ordinances in the mid-1780s: the Land Ordinance of 1784, the Land Ordinance of 1785, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . These ordinances collectively provided a process for adding new and equal states to the nation, guaranteed republican governments and other rights for the new states and its inhabitants, banned slavery and involuntary servitude in the new territories after 1800, and provided for public education in the new states. Overall, the ratification of these ordinances was impressive, given the lack of unity among the states at the time and the super-majority vote needed to pass them.

Yet, the Articles of Confederation’s weaknesses triumphed over its virtues. As a result, the Annapolis Convention was called on September 11, 1786, just a few weeks after the outbreak of Shays’ Rebellion. The convention was called initially to address changes regarding trade, but the delegates realized the problems had a broader scope. John Dickinson, who had chaired the committee to draft the Articles, was president of the Annapolis Convention. He along with other delegates, particularly Alexander Hamilton , resolved to reconvene at a convention in Philadelphia to revise the Articles in May 1787.

The Philadelphia Convention of 1787 went beyond its mandate to revise the Articles by replacing it with a new constitution. However, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention incorporated several ideas from the Articles into the new charter. Examples of this incorporation include the full faith and credit clause and the power to declare war. In addition, the privileges and immunities clause of Article IV of the Articles was incorporated into Article IV of the Constitution.

Even after state conventions ratified the Constitution in 1788, the Articles of Confederation continued to inspire changes to the new federal charter. In 1791, Article II of the Articles of Confederation served as the basis for the 10 th Amendment to the Constitution. Born out of necessity to fight the War for Independence, the Articles of Confederation created a “perpetual union” that later generations of Americans would later strive to make “more perfect.”

Aubrianna Mierow The George Washington University

1. Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 , ed. Worthington C. Ford et al. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904-37), 8:431.

2. JCC, 1774-1789 , ed. Ford et al., 9:907.

4. Ibid, 9:908.

5. Ibid, 9:908-9.

6. George Washington to Benjamin Harrison, 18 January 1784, Founders Online , National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0039 .

7. John Jay to George Washington, 27 June 1786, Founders Online , National Archives, last modified June 13, 2018, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-04-02-0129 .

Bibliography:

Kaminski, John. “Empowering the Confederation: a Counterfactual Model.” (2005) Accessed November 1, 2018. https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/calvinjohnson/RighteousAnger/ SHEAR2005Kaminski.pdf .

Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 . New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011.

Rakove, Jack N. The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress . New York: Knopf, 1979.

Richards, Leonard L. Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Van Cleve, George. We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic 1776-1787 . Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Quick Links

9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Historyplex

Articles of Confederation Summary

A summary of the Articles of Confederation, which will not just help you get a better understanding of this agreement, but also help you differentiate its guidelines from those of the Constitution.

Not many people know this, but the Articles of Confederation was used as the first constitution of the United States of America. It was used as the supreme law for a brief period in the American history between March 1, 1781, and March 4, 1789. Even though it was written by the same people who wrote the Constitution, you can see a great deal of difference between the two.

Summary of the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation was a five-page written agreement, which laid the guidelines of how the national government of America would function. The preamble of the Articles stated that all the signatories “ agree to certain Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union ” between the thirteen original states. It had a total of thirteen articles which formed the guidelines for the functioning of then Federal government along with a conclusion and a signatory section for the states to sign. Given below is the summary of these thirteen articles which will put forth brief information on each of them with special emphasis on what they imply.

- Article I: It gave the new confederacy a name―the ‘United States of America’, which is followed even today.

- Article II: It gave all the states sovereignty, freedom, and independence, alongside all those powers which were not specifically given to the national government.

- Article III: It implied that the different states should come together to facilitate common defense, secure each other’s liberties, and work for each other’s welfare.

- Article IV: It granted the freedom of movement to all the citizens of the nation as a whole which allowed people to move freely between the states and also entitled them to get the rights established by the particular state. It also spoke about the need of respecting each other’s laws and a clause to extradite criminals.

- Article V: It spoke about the national interests of the United States and asked each state to send delegates to discuss the same in the Congress. It gave each state one vote in Congress and restricted the period for which a person would serve as a delegate. It also gave the members of Congress the power of free speech and ruled out their arrests, unless the crime was something serious, such as treason or felony.

- Article VI: It put some restrictions on the states and disallowed them from getting into any sort of treaty or alliance with each other or waging a war without the consent of the Congress. It also disallowed the states from keeping a standing army, but did give them permission to maintain the state militia.

- Article VII: It gave the state legislature the power of appointing all officers ranked colonel and above, whenever the states were to raise an army for the purpose of self defense.

- Article VIII: It stated that each state was to pay a particular sum of money―in proportion to the total land area of that state―to the national treasury and added that all the national expenses including war costs were to be deducted from this common treasury.

- Article IX: It highlighted all the powers given to the Congress of the Confederation, including the right to wage wars and make peace, govern army and navy, enter into treaties and alliances, settle dispute between states, regulate the value of coins, etc.

- Article X: It laid the guidelines for the formation of an executive committee which would work when the Congress was not in session.

- Article XI: It stated that the approval of nine of the thirteen original states was mandatory to include a new state in the Union.

- Article XII: It declared that America takes full responsibility for all debts which were incurred before the Articles came into existence.

- Article XIII: It declared that it would be mandatory for all the states to abide by the decisions made by the Congress of the Confederation. It also declared that the Union would be perpetual. Most important of all, it put forth the stipulation that if any changes were to be made to the Articles of the Confederation it would require the approval of Congress and ratification by the states.

Historians are of the opinion that this document had its own strengths and weaknesses. That it brought the thirteen states, which were pitted against each other, on a common platform was its greatest strength. On the other hand, its weaknesses revolved around the fact that it gave states more power than the national government and reduced the latter to a mere spectator.

If the strengths and weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation are weighed against each other, you notice that its weaknesses outweighed its strengths; that explains why it was eventually replaced by the U.S. Constitution―the supreme law in the United States as of today.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

Milestone Documents

Articles of Confederation (1777)

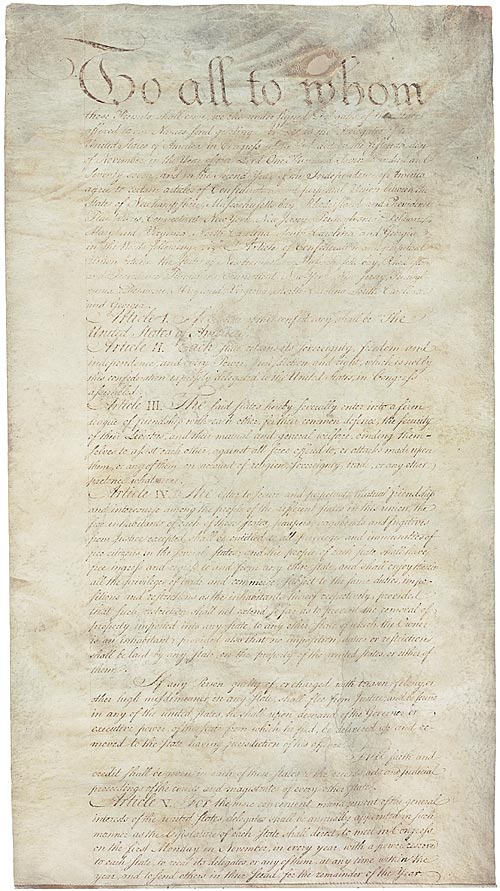

Citation: Articles of Confederation; 3/1/1781; Miscellaneous Papers of the Continental Congress, 1774 - 1789; Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention, Record Group 360; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

View All Pages in the National Archives Catalog

View Transcript

The Articles of Confederation were adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777. This document served as the United States' first constitution. It was in force from March 1, 1781, until 1789 when the present-day Constitution went into effect.

After the Lee Resolution proposed independence for the American colonies, the Second Continental Congress appointed three committees on June 11, 1776. One of the committees was tasked with determining what form the confederation of the colonies should take. This committee was composed of one representative from each colony. John Dickinson, a delegate from Delaware, was the principal writer.

The Dickinson Draft of the Articles of Confederation named the confederation "the United States of America." After considerable debate and revision, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation on November 15, 1777.

The document seen here is the engrossed and corrected version that was adopted on November 15. It consists of six sheets of parchment stitched together. The last sheet bears the signatures of delegates from all 13 states.

This "first constitution of the United States" established a "league of friendship" for the 13 sovereign and independent states. Each state retained "every Power...which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States. The Articles of Confederation also outlined a Congress with representation not based on population – each state would have one vote in Congress.

Ratification by all 13 states was necessary to set the Confederation into motion. Because of disputes over representation, voting, and the western lands claimed by some states, ratification was delayed. When Maryland ratified it on March 1, 1781, the Congress of the Confederation came into being.

Just a few years after the Revolutionary War, however, James Madison and George Washington were among those who feared their young country was on the brink of collapse. With the states retaining considerable power, the central government had insufficient power to regulate commerce. It could not tax and was generally impotent in setting commercial policy. Nor could it effectively support a war effort. Congress was attempting to function with a depleted treasury; and paper money was flooding the country, creating extraordinary inflation.

The states were on the brink of economic disaster; and the central government had little power to settle quarrels between states. Disputes over territory, war pensions, taxation, and trade threatened to tear the country apart.

In May of 1787, the Constitutional Convention assembled in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation. They shuttered the windows of the State House (Independence Hall) and swore secrecy so they could speak freely. By mid-June the delegates had decided to completely redesign the government. After three hot, summer months of highly charged debate, the new Constitution was signed, which remains in effect today.

Teach with this document.

Previous Document Next Document

To all to whom these Presents shall come, we, the undersigned Delegates of the States affixed to our Names send greeting. Whereas the Delegates of the United States of America in Congress assembled did on the fifteenth day of November in the year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy seven, and in the Second Year of the Independence of America agree to certain articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of Newhampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhodeisland and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia in the Words following, viz. “Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the States of Newhampshire, Massachusetts-bay, Rhodeisland and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

Article I. The Stile of this confederacy shall be, “The United States of America.”

Article II. Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.

Article III. The said states hereby severally enter into a firm league of friendship with each other, for their common defence, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare, binding themselves to assist each other, against all force offered to, or attacks made upon them, or any of them, on account of religion, sovereignty, trade, or any other pretence whatever.

Article IV. The better to secure and perpetuate mutual friendship and intercourse among the people of the different states in this union, the free inhabitants of each of these states, paupers, vagabonds and fugitives from Justice excepted, shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of free citizens in the several states; and the people of each state shall have free ingress and regress to and from any other state, and shall enjoy therein all the privileges of trade and commerce, subject to the same duties, impositions and restrictions as the inhabitants thereof respectively, provided that such restrictions shall not extend so far as to prevent the removal of property imported into any state, to any other State of which the Owner is an inhabitant; provided also that no imposition, duties or restriction shall be laid by any state, on the property of the united states, or either of them.

If any Person guilty of, or charged with, treason, felony, or other high misdemeanor in any state, shall flee from Justice, and be found in any of the united states, he shall upon demand of the Governor or executive power of the state from which he fled, be delivered up, and removed to the state having jurisdiction of his offence.

Full faith and credit shall be given in each of these states to the records, acts and judicial proceedings of the courts and magistrates of every other state.

Article V. For the more convenient management of the general interests of the united states, delegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislature of each state shall direct, to meet in Congress on the first Monday in November, in every year, with a power reserved to each state to recall its delegates, or any of them, at any time within the year, and to send others in their stead, for the remainder of the Year.

No State shall be represented in Congress by less than two, nor by more than seven Members; and no person shall be capable of being delegate for more than three years, in any term of six years; nor shall any person, being a delegate, be capable of holding any office under the united states, for which he, or another for his benefit receives any salary, fees or emolument of any kind.

Each State shall maintain its own delegates in a meeting of the states, and while they act as members of the committee of the states.

In determining questions in the united states, in Congress assembled, each state shall have one vote.

Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any Court, or place out of Congress, and the members of congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests and imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendance on congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace.

Article VI. No State, without the Consent of the united States, in congress assembled, shall send any embassy to, or receive any embassy from, or enter into any conferrence, agreement, alliance, or treaty, with any King prince or state; nor shall any person holding any office of profit or trust under the united states, or any of them, accept of any present, emolument, office, or title of any kind whatever, from any king, prince, or foreign state; nor shall the united states, in congress assembled, or any of them, grant any title of nobility.

No two or more states shall enter into any treaty, confederation, or alliance whatever between them, without the consent of the united states, in congress assembled, specifying accurately the purposes for which the same is to be entered into, and how long it shall continue.